Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

-

Promy Virk

, Manal A. Awad

, Meznah M. Alanazi

, Awatif A. Hendi

Abstract

Over the past few decades, nanotechnology has shown promising prospects in biomedicine and has a proven impact on enhancing therapeutics by facilitating drug delivery. The present study brings an amalgamation of nanoscience and “clean technology” by fabricating nature-friendly nanoparticles (NPs) sans the use of chemical surfactants using Indian mustard seed, Brassica juncea L. The as-synthesized NPs were characterized to assess their average size, crystallinity, morphology, and constituent functional groups through conventional techniques: dynamic light scattering (DLS), X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). The NPs were crystalline in nature and exhibited a mean size of 205.5 nm (PDI of 0.437) being primarily polygonal in shape. Additionally, the therapeutic efficacy of the green NPs was evaluated based on their cytotoxic effect against two human cancer lines, MCF-7 and HepG-2. Both the NPs and the bulk seeds showed a dose-dependent cytotoxic effect. However, an assessment of the antiproliferative/cytotoxic potential of the green NPs versus the bulk seeds showed that the NPs were relatively more efficacious on both cell lines. Taken together, the mustard seed NPs could be potential nutraceuticals considering the green credential in their mode of biosynthesis.

1 Introduction

Plant-based pharmaceuticals are the new age trend in research in biotechnology and medicine. It is an innovative and sustainable approach in therapeutics to combat a host of civilization diseases in the community including cancer. Cancer is commonly characterized by unregulated proliferation of cells. Breast cancer is the second leading cause of mortality among women [1] in both developed and developing regions, with a higher rate in developing countries compared to developed regions [2]. However, there has been significant improvement in the 5-year survival rate in hormone receptor-positive breast cancer [3], cancer recurrence, and subsequent drug resistance seem inevitable [4]. This warrants an imperative need to develop alternative, safer, and natural therapeutic strategies. Furthermore, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a common type of liver cancer which is also the third leading cause of cancer-related mortalities worldwide, affecting over 500,000 people, and being highly prevalent in Asia and Africa [5]. Epidemiological studies have shown an optimistic association between the consumption of plant-based foods and reduced prevalence of cancer, heart disease, and other degenerative diseases [6,7]. Brassica juncea L. belonging to the Brassicaceae family, popularly known as the Indian mustard, has been known for both its culinary and therapeutic uses since ancient times. Mustard seeds have a strong antioxidant status which is characterized by the presence of bioactive constituents primarily the phenolic compounds attributed to their pharmacological potential [8]. The presence of sulfur-containing compounds such as glucosinolates in cruciferous vegetables such as Indian mustard reduces the risk of various types of cancer, including colon, kidney, and prostate cancer [9,10]. The glucosinolates are hydrolyzed by the enzyme myrosinase present in cruciferous vegetables to yield biologically active isothiocyanates [11]. Isothiocyanates, a phytonutrient that has been widely studied for its anticancer benefits, are important phytocompounds in mustard seeds. Isothiocyanates can inhibit mitosis and stimulate apoptosis (cell death) in human tumor cells and significantly inhibit bladder cancer growth [11]. In addition, in a study on human colon cancer cell lines, it was reported to induce programmed cell death of colon cancer [12].

The present trend in therapeutics encourages the use of alternative and complementary medicine in cancer prevention. Natural products offer an enormously promising approach for chemoprevention to slow down the progression of cancer. Accordingly, several natural phytocompounds/plants have provided modern medicine with the drugs used as cytostatics [13]. It has been reported earlier that the use of phytocompounds in therapy is restricted owing to their low solubility and availability in the biological milieu [14]. The term nanomedicine is commonly used to describe the integrated discipline of science and technology used in prevention, diagnosis, and therapeutics using nanoscale materials carefully designed to perform these functions [15]. Nanomaterials have distinctive physicochemical properties that confer them with an increased specific surface area and enhanced optical, magnetic, or mechanical properties [16]. Thus, carrier systems based on nanoparticles ensure a sustainable release of bioactive substances contributing to an enhanced bioavailability [3]. There is a plethora of literature that reports the phyto-mediated synthesis of several nanoparticles. However, most of the studies mention the use of biogenic synthesis of metallic nanoparticles using plant products/compounds [17]. There is still a paucity of studies based on the biogenic synthesis of non-metallic nanostructures. Keeping the premise, the present study aimed at a phyto-mediated synthesis of nanoparticles without the use of chemical surfactants/reductants with clean technology as the cornerstone. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the role of non-metallic mustard seed nanoparticles for which the patent has been granted by USPTO (US) [18].

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Synthesis of nanoparticles

Mustard seeds procured from the local market were washed in tap water and then air-dried. The dried seeds were ground using a mechanical grinder. Mustard seed powder (400 mg) was mixed with 30 mL of solvent with constant stirring; this solution was then sprayed into boiling water (50 mL) at a flow rate of 0.2 mL·min−1 for 5 min under ultrasonic conditions (750 W and a frequency of 20 kHz). After 5 min of sonication, the contents were centrifuged at 200–800 rpm for about 20 min at room temperature and dried to obtain mustard seed nanoparticles.

2.2 Characterization of nanoparticles

The synthesized Indian mustard seed nanoparticles were characterized using the following techniques: zetasizer (Nano series, HT-laser, ZEN3600 from Molvern Instrument, UK) was used to analyze the mean size of the mustard seed powder nanoparticles. The scanning electron microscope (SEM) (JEOL JSM-7600F, USA) is one of the most effective electron microscopy techniques that allows accurate assessment of the size, shape, distribution, spatial resolution, and variations in composition and structure of NPs. Mustard NPs were characterized by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Perkin-Elmer FTIR spectrum BX, USA) by mixing nanoparticle dry powder with potassium bromide (KBr). The spectra were recorded in the range from 4,400 to 400 cm−1. FTIR data revealed details of the functional groups in the mustard seeds and nanoparticles. The method for determining the crystal structure or crystal phase is X-ray diffraction. Dried mustard powder was used for analysis. Diffraction patterns were recorded by PAN Analytical XPert PRO (Netherlands) operated at 40 mA and 45 kV using CuK radiation (0.15406 nm). The crystallographic information was recorded in a range from 0° to 100°.

2.3 Evaluation of cytotoxic effects

The potential anti-proliferative effect of the nanoparticles was tested in vitro on MCF-7 cells and HepG-2 cell lines obtained from VACSERA Tissue Culture Unit (Cairo, Egypt). The cytotoxic activity of the nanoparticles was analyzed by 3-(4,5-dimethylthazolk-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) colorimetry assay [19]. For the assay, cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a concentration of 110 × 4 cells·well−1 in 100 μL of growth medium. Incubation was allowed for 24 h at 37°C, and then, the cells were allowed to settle. Various concentrations of the mustard seed powder and its nano-formulation were added and incubated for a further 48 h, and the yield of viable cells was colorimetrically determined. All experiments were performed in triplicates. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) was computed from dose-response curve plots using Graphpad Prism software (San Diego, CA, USA).

3 Results

3.1 Characterization of nanoparticles

Particle size distribution for synthesized mustard seed nanoparticles was determined by the DLS technique shown in Figure 1. The sample of synthesized NPs was of variable size, two broad peaks were observed with a higher intensity toward the larger particles, with an average size of 205.5 nm and a PDI of 0.437.

X-ray diffractograms of mustard seeds and mustard nanoparticles.

X-Ray diffractogram of mustard seed powder showed a characteristic high peak at a diffraction angle of 2θ at 22°. A similar peak at a lower intensity appeared for the nano-formulation of the mustard seed that confirms the presence of the crystals of nano mustard. However, in addition to the main peak, which was sharp, three short peaks appeared for the nano mustard at 2θ ≈ 30°, 40°, and 50° (Figure 2). Therefore, it can be concluded that the nano-fabricated sample was crystallized.

DLS spectrum of mustard seed nanoparticles.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images shown in Figure 3 demonstrate the variable shape and heterogeneity in the particle size distribution of mustard seed nanoparticles. The results on the structure of mustard NPs characterized by SEM are in consensus with the DLS analysis. Also, SEM images fairly represent the particles in suspension, showing the shape and size distribution of the synthesized nanoparticles. This exhibited polydispersed nature of the particles corresponding with DLS results. The morphotype of the synthesized nanoparticles is shown in Figure 3a–d, which is seen primarily as polygonal shaped.

(a–c) Micrographs obtained by scanning electron microscopy, showing morphology and size of the mustard seed nanoparticles. (d) Chemical structure of mustard seed glucosinolates, sinalbin, and sinigrin.

FTIR spectroscopy was performed to classify the chemical essence of both the raw mustard seeds and their nano-formulation. Figure 4a and b show the FTIR spectrum of the mustard seeds or mustard nanoparticles in the range of 400–4,000 cm−1. Figure 4b shows a strong absorption band at 3,428.60 cm−1 resulting from the stretching of the NH amino band or indicative of the hydroxyl-bonded OH band reflecting the presence of alcohols, phenols, and carbohydrates. The band (2,928.4 cm−1) relates to the asymmetric stretching of the C–H bonds. The band at 1,745.48 cm−1 shows the fingerprinting region of CO, C–O, and O–H groups, and the bands at 1,657.25, 1,545.48, and 1,422.5 cm−1 for aliphatic amines. The absorption band for native proteins at 1657.25 cm−1 is similar to that recorded [19]. The band at 1,657.25 cm−1 is known as amide I and amide II, which arise from carbonyl (C═O) and amine (NH) stretches in the amide bonds of the protein. Shearing methylene vibrations of proteins could be related to the absorption band at 1,422.5 cm−1. The strong band at 1,103.92 cm−1 is recognized as the C–N stretching vibrations of aliphatic amines. The C–H stretch is assigned the band at 719.59 cm−1, and the band at 1,422.5 cm−1 corresponds to the C–C stretches for the aromatic ring.

FTIR analysis of mustard seeds (A) and mustard seed nanoparticles (B).

3.2 Anti-cancer activity

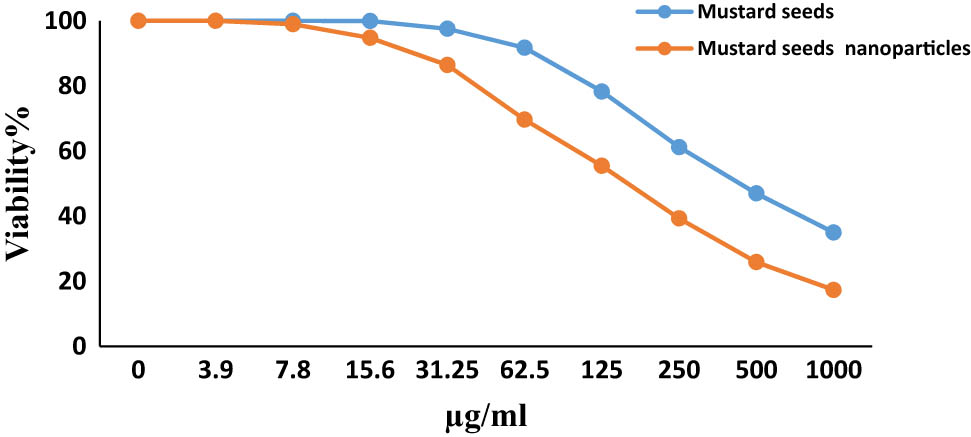

The cytotoxic outcome of the mustard seed nanoparticles on human cancer cell lines (MCF-7 and HepG-2) showed a more profound effect than the mustard seed powder. At a high concentration (1,000 µg·mL−1), the mustard seed nanoparticles had an inhibitory percentage of 82.67 on HepG-2 cell growth, while the mustard seed powder showed an inhibitory percentage of 65.94 at the same concentration (Figure 5). For the nanoparticles, the inhibitory effect on HepG-2 cell growth was detectable at a lower concentration of 7.8 µg·mL−1, while for the mustard seed powder, it was observed at 31.25 µg·mL−1, which was 4-fold more than the initial inhibitory concentration of the nanoparticles (Table 1). Additionally, the IC50 of the nanoparticles against Hep2-G cells was 477 ± 32.68 µg·mL−1, while the IC50 of the mustard seed powder was only 167 ± 16.79 µg·mL−1.

Evaluation of cytotoxicity of mustard seed and its nanoformulation against HepG-2.

Inhibitory activity of mustard seed (part A) and the nanoparticles (part B) against HepG-2 cell line

| A Concentration (µg·mL−1) | Viability % (3 replicates) | Mean | Inhibitory % | S.D. | B Concentration (µg·mL−1) | Viability % (3 replicates) | Mean | Inhibitory % | S.D. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | ||||||||

| 1,000 | 38.91 | 32.74 | 30.52 | 34.06 | 65.94 | 4.35 | 1,000 | 17.82 | 14.97 | 19.21 | 17.3 | 82.67 | 2.16 |

| 500 | 49.23 | 46.56 | 45.17 | 46.99 | 53.01 | 2.06 | 500 | 26.9 | 23.81 | 26.9 | 25.9 | 74.13 | 1.78 |

| 250 | 64.37 | 60.98 | 58.25 | 61.2 | 38.8 | 3.07 | 250 | 37.23 | 40.72 | 39.88 | 39.3 | 60.72 | 1.82 |

| 125 | 81.65 | 79.82 | 73.46 | 78.31 | 21.69 | 4.3 | 125 | 52.06 | 56.94 | 57.31 | 55.4 | 44.56 | 2.93 |

| 62.5 | 92.41 | 97.63 | 85.21 | 91.75 | 8.25 | 6.24 | 62.5 | 67.34 | 72.18 | 69. 4 | 69.6 | 30.36 | 2.43 |

| 31.25 | 98.62 | 99.87 | 94.25 | 97.58 | 2.42 | 2.95 | 31.25 | 85.62 | 89.41 | 84.23 | 86.4 | 13.58 | 2.68 |

| 15.6 | 100 | 100 | 99.87 | 99.96 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 15.6 | 95.21 | 96.8 | 92.37 | 94.8 | 5.21 | 2.24 |

| 7.8 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 7.8 | 99.76 | 99.76 | 97.43 | 99 | 1.02 | 1.35 |

| 3.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 3.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

For the MCF-7 cells, the mustard seed nanoparticles produced an inhibitory percentage at the highest tested concentration (1,000 µg·mL−1) of 75.09, while the mustard seed powder at the same test concentration produced an inhibitory percentage of only 55.97 (Table 2 and Figure 6). Further, for the nanoparticles, an inhibitory effect on the MCF-7 cells was detectable at a lower concentration of 15.6 µg·mL−1 while for the mustard seed powder, the inhibitory effect was first observed at 62.5 µg·mL−1 as shown in Table 2. In addition, the IC50 of the mustard seed powder against MCF-7 cells was 781.1 ± 62.44 µg·mL−1, while the IC50 of the nanoparticles against MCF-7 cells was only 299.7 ± 60.3 µg·mL−1.

Inhibitory activity of Mustard seed (part A) and the nanoparticles (part B) against HepG-2 cell line

| A Concentration (µg·mL−1) | Viability % (3 replicates) | Mean | Inhibitory % | S.D. | B Concentration (µg·mL−1) | Viability % (3 replicates) | Mean | Inhibitory % | S.D. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | ||||||||

| 1,000 | 46.84 | 44.37 | 40.89 | 44.03 | 55.97 | 2.99 | 1,000 | 25.47 | 21.89 | 27.36 | 24.91 | 75.09 | 2.78 |

| 500 | 59.2 | 56.43 | 57.38 | 57.67 | 42.33 | 1.41 | 500 | 40.89 | 36.56 | 40.89 | 39.45 | 60.55 | 2.5 |

| 250 | 76.43 | 76.43 | 79.41 | 77.42 | 22.58 | 1.72 | 250 | 53.42 | 48.17 | 56.27 | 52.62 | 47.38 | 4.11 |

| 125 | 89.51 | 87.84 | 91.37 | 89.57 | 10.43 | 1.77 | 125 | 70.84 | 65.92 | 71.43 | 69.4 | 30.6 | 3.03 |

| 62.5 | 97.42 | 98.68 | 99.53 | 98.54 | 1.46 | 1.06 | 62.5 | 89.51 | 87.24 | 87.24 | 88 | 12 | 1.31 |

| 31.25 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 31.25 | 97.26 | 95.31 | 96.86 | 96.48 | 3.52 | 1.03 |

| 15.6 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 15.6 | 100 | 98.64 | 99.72 | 99.45 | 0.55 | 0.72 |

| 7.8 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 7.8 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 3.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 3.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

Evaluation of cytotoxicity of mustard seed and its nano formulation against MCF-7.

4 Discussion

The current study reported the biogenic synthesis of non-metallic nanoparticles of mustard seed powder on the lines of green credentials. The formation of nanoparticles was confirmed by the extensive characterization employed, and the SEM images ensured that the synthesized nanoparticles were within nanoscale size. The DLS results indicated a size of 205.1 for the nanoparticles produced. It has been postulated that DLS measurement is more sensitive to larger particles. These results suggest the calculation of DLS for polydispersed samples may not be accurate [20]. The broadening of the XRD peaks suggested the presence of nano-sized crystals in the nanoparticle sample. Broadening of the peaks is usually due to the small crystallite size, and it might be associated with strain (micro deformation) which can be best explained based on the Debye–Scherrer equation [21]. The morphotype of the nanoparticles which was primarily observed as polygonal mirrored the chemical structure of glucosinolates in the mustard seeds, sinalbin, and sinigrin [22]. These glucosinolates are the key constituents that exhibit anti-cancer activity. The FTIR spectra of the bulk and nanosized mustard seeds were quite similar and suggest that the nanosization did not alter the molecular structure of the bioconstituents conferring chemical stability to the nanoparticles. The absorption band for native proteins at 1,657.25 cm−1 in the mustard seed was similar to that reported earlier [23]. The band at 3,428.60 cm−1 which corresponded to the stretching of the –NH amino/–OH hydroxyl bond group is attributed to the presence of alcohols, phenols, and carbohydrates [24]. FTIR results clearly indicated the presence of groups of carboxyl (−C═O), hydroxyl (−OH), and amine (N−H) in mustard seed and the nanoparticles, which has been documented in the previous literature [25].

In the current study, the antiproliferative/cytotoxic activity of the synthesized nanoparticles was evaluated using the MTT assay. Compared to the bulk seeds, the nanoparticles were more showed a more profound anti-proliferative effect on both human cancer cell lines used (HepG-2 and MCF-7). Similar results have been reported on the potency of nano-sized plant extracts compared to the bulk material [26,27]. In addition, Abel et al. [26] reported that the silver nano-formulated Senna tora leaf extracts had a significant inhibitory effect on colon cancer cells, rather than the leaf extract alone. A mixture of Olea europaea fruit extract and Acacia nilotica peel extract in gold nanoparticles showed profound anticancer activity against different cancer cell lines (HepG-2, HCT-116, and MCF-7) [24]. In addition, experimental results of a previous study by Hasan et al. [28] demonstrated that mustard seed possesses potent antioxidant-inflammatory effects, and its nanostructure (silver nanoparticles of a mustard seed) was more effective than usual at alleviating oxidative stress, reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines production, and reversing DNA genotoxicity in animal models. The anti-cancer potential of mustard seeds is attributed to the phytochemical profile which reveals the presence phytocompounds: phenols, flavonoids, tannins, and vitamins responsible for their antioxidant status [7,29,30]. It has been recognized that oxidative stress is one of the key players driving the pathogenesis of several diseases including cancer. Indian mustard seeds exhibit potent antioxidant potential that prevents induced carcinogenesis, in consensus with the results of the present study on the anti-cancer activity of mustard seeds, showing that mustard seed powder suppresses the growth of bladder cancer cells in vitro and in vivo [7]. In addition, mustard seed extract significantly reduced oxidative stress in HepG2 cell line by suppressing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and showed a marked hepatoprotective effect [29]. The vitamin E, quercetin, and catechin detected in the mustard seed extracts also showed hepatoprotective activity in the HepG2 cell line [29]. In addition, allyl isothiocyanate (AITC; 3-isothiocyanato-1-propene or 2-propenyl isothiocyanate) also is a potent anti-cancerous compound that is abundant in cruciferous vegetables such as Indian mustard. Taken together, a synergistic effect of all the phytoconstituents of the mustard seeds contributed to the marked anti-cancer effect of the mustard seed powder and its nano formulation in the present study. The nanosization strategy used in the present study enhanced the bioavailability and thus the efficacy of the mustard seeds. Furthermore, the biosynthetic method was facile, environmentally benign, and cost-effective. Previously, in congruence to the biogenic mode of synthesis employed in the present study, there have been studies on the nanoarchitecture of non-metallic nanoparticles of phytocompounds such as curcumin and naringenin [31,32,33,34]. The findings of the present study are further supported by the results of our recent in vivo study on the efficacy of synthesized nanoparticles of mustard seed against arsenic toxicity. The results clearly demonstrated a more efficacious attenuating effect of the nanoparticles versus the bulk or naïve mustard seeds against arsenic-induced oxidative damage and genotoxicity in a rat model [28,35] supporting the cytotoxic effect of the NPs on the cancer cell lines.

5 Conclusions

In conclusion, the present results demonstrate that the nano-formulation of mustard seeds significantly reduced the cell viability and transformed the cellular morphology of MCF-7 and HepG-2 cells at different concentrations in a dose-dependent manner. However, further in vivo and in vitro studies at the molecular level are imperative to understand the mechanism(s) of action. The study provides insights into the prospective role of Indian mustard seeds and their nano-formulation in potential adjunct therapy for cancer and as a nutraceutical.

-

Funding information: This work was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, through the Research Groups Program Grant no. RGP-1443-0047.

-

Author contributions: Promy Virk, Manal A. Awad: conceptualization, writing, supervision; Meznah M. Alanazi, Awatif A. Hendi: data curation, methodology, resource acquisition; Mai Elobeid: data curation, reviewing, editing; Khalid M. Ortashi: visualization, software; Albandari W. Alrowaily, Taghreed Bahlool: investigation, validation; Fatma Aouaini: methodology, reviewing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] American Cancer Society. What are the key statistics about breast cancer? http://www.cancer.org/cancer/breastcancer/detailedguide/breastcancer-key-statistics. Accessed: February 4, 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Ferlay J, Parkin D, Steliarova-Foucher E. Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2008. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(4):685–850. 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Giessrigl B, Schmidt WM, Kalipciyan M, Jeitler M, Bilban M, Gollinger M, et al. Fulvestrant induces resistance by modulating GPER and CDK6 expression: implication of methyltransferases, deacetylases and the hSWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:2751–62. 10.1038/bjc.2013.583.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Marquette C, Nabell L. Chemotherapy-resistant metastatic breast cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2012;13(2):263–75. 10.1007/s11864-012-0184-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Rawla P, Sunkara T, Muralidharan P, Raj J. Update in global trends and aetiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Contemp Oncol (Pozn)/Współczesna Onkologia. 2018;22(3):141–50. 10.5114/wo.2018.78941.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Czapski J. Cancer preventing properties of cruciferous vegetables. J Fruit Ornam Plant Res. 2009;70:5–18. 10.2478/v10032-009-0001-3.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Kaur C, Kapoor H. Anti-oxidants in fruits and vegetables- the millennium’s health. Int J Food Sci. 2001;36:703–25. 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2001.00513.x.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Das G, Tantengco OAG, Tundis R, Robles JAH, Loizzo MR, Shin HS, et al. Glucosinolates and Omega-3 fatty acids from mustard seeds: Phytochemistry and pharmacology. Plants. 2022;11(17):2290. 10.3390/plants11172290.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Bhattacharya A, Li Y, Wade KL, Paonessa JD, Fahey JW, Zhang Y. Allyl isothiocyanate-rich mustard seed powder inhibits bladder cancer growth and muscle invasion. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(12):2105–10. 10.1093/carcin/bgq202.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Bennett RN, Rosa EA, Mellon FA, Kroon PA. Ontogenic profiling of glucosinolates, flavonoids and other secondary metabolites in Eruca sativa (salad rocket), Diplotaxis erucoides (wall rocket), Diplotaxis tenuifolia (wild rocket) and Bunias orientalis (Turkish rocket). J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:4005–15. 10.1021/jf052756t.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Ahmed AG, Hussein UK, Ahmed AE, Kim KM, Mahmoud HM, Hammouda O, et al. Mustard seed (Brassica nigra) extract exhibits antiproliferative effect against human lung cancer cells through differential regulation of apoptosis, cell cycle, migration, and invasion. Molecules. 2020;25(9):2069. 10.3390/molecules2509206.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Grygier A. Mustard seeds as a bioactive component of food. Food Rev Int. 2022;1–14. 10.1080/87559129.2021.2015774.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Ma L, Zhang M, Zhao R, Wang D, Ma Y, Ai L. Plant natural products: Promising resources for cancer chemoprevention. Molecules. 2021;26(4):933. 10.3390/molecules26040933.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Asiri A, Elobeid M, Virk P, Awad M. Ameliorative effect of resveratrol and its nano-formulation on estrogenicity and apoptosis induced by low dose of zearalenone in male Wistar rats. J Mater Res. 2021;36:4329–43. 10.1557/s43578-021-00425-w.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Riyadh M, Gomha S, Mahmmoud E, Elaasser M. Synthesis and Anticancer activities of Thiazoles, 1, 3-Thiazines, and Thiazolidine using chitosan-grafted-poly (vinylpyridine) as basic catalyst. Heterocycles. 2015;91(6):1227–43. 10.3987/COM-15-13210.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Khan I, Saeed K, Khan I. Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and toxicities. Arab J Chem. 2019;12(7):908–31. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2017.05.011.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Fierascu I, Fierascu IC, Brazdis RI, Baroi AM, Fistos T, Fierascu RC. Phytosynthesized metallic nanoparticles—between nanomedicine and toxicology. A brief review of 2019′s findings. Materials. 2020;13(3):574. 10.3390/ma13030574.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Awad MAG, Virk P, Qindeel R, Ortashi KMO, Elobeid MA. Synthesis of mustard seed nanoparticles, US Pat., 10398744, 2019.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Yusuf H, Fahriani M, Murzalina C. Anti proliferative and apoptotic effect of soluble ethyl acetate partition from ethanol extract of Chromolaena odorata linn leaves against hela cervical cancer cell line. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2022;23(1):183–9. 10.31557/APJCP.2022.23.1.183.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Domingos R, Baalousha M, Ju-Nam Y, Reid N, Tufenkji N, Lead J, et al. Characterizing manufactured nanoparticles in the Environment: Multimethod determination of particle sizes. Env Sci Technol. 2009;43(19):7277–84. 10.1021/es900249m.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Li B, Jiang L, Li X, Ran P, Zuo P, Wang A, et al. Preparation of Monolayer MoS2 quantum dots using temporally shaped femtosecond laser ablation of bulk MoS2 targets in water. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):11182. 10.1038/s41598-017-10632-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Popova I, Morra M. Sinigrin and sinalbin quantification in mustard seed using high performance liquid chromatography–time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J Food Compos Anal. 2014;35(2):120–6. 10.1016/j.jfca.2014.04.011.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Yilmaz M, Mehmet A, Turkdemir H, Bayram E, Çiçek A, Mete A, et al. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Stevia rebaudiana. Mater Chem Phys. 2011;130(3):1195–202. 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2011.08.068.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Akhlagh H. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Pimpinella anisum L. seed aqueous extract and its antioxidant activity. J Chem Health Risks. 2015;5:257–65.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Khatami M, Soltani N, Pourseyed S. Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mustard and its characterization. Int J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2016;11(4):281–8.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Abel E, Poonga J, Panicker G. Characterization and in vitro studies on anticancer, antioxidant activity against colon cancer cell line of gold nanoparticles capped with Cassia tora SM leaf. Appl Nanosci. 2016;6:121–9. 10.1007/s13204-015-0422-x.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Awad A, Eisa N, Virk P, Hendi A, Ortashi K, Mahgoub A, et al. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles: preparation, characterization, cytotoxicity, and anti-bacterial activities. Mater Lett. 2019;256:126608. 10.1016/j.matlet.2019.126608.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Hassan SA, Hagrassi AME, Hammam O, Soliman AM, Ezzeldin E, Aziz WM. Brassica juncea L. (Mustard) extract silver nanoparticles and knocking off oxidative stress, proinflammatory cytokine and reverse DNA genotoxicity. Biomolecules. 2020;10(12):1650. Published 2020 Dec 9. 10.3390/biom10121650.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Parikh H, Pandita N, Khanna A. Phytoextract of Indian mustard seeds acts by suppressing the generation of ROS against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in HepG2 cells. Pharm Biol. 2015;53(7):975–84. 10.3109/13880209.2014.950675.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] AlDiwan M, ALWahhap Z, AlMasoudi W. Antioxidant activity of crud extracts of Brassica juncea L. seeds on experimental rats. Pharma Innov. 2016;5(8):89–96.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Rahimi HR, Nedaeinia R, Sepehri Shamloo A, Nikdoust S, Kazemi Oskuee R. Novel delivery system for natural products: Nano-curcumin formulations. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2016;6(4):383–98. PMID: 27516979; PMCID: PMC4967834.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Kandeil MA, Mohammed ET, Radi RA, Khalil F, Abdel-Razik AH, Abdel-Daim MM, et al. Nanonaringenin and vitamin E ameliorate some behavioral, biochemical, and brain tissue alterations induced by nicotine in rats. J Toxicol. 2021;2021:4411316. 10.1155/2021/4411316.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Al-Ghamdi NAM, Virk P, Hendi A, Awad M, Elobeid M. Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Green Process Synth. 2021;10(1):392–402. 10.1515/gps-2021-0037.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Ahmad A, Prakash P, Khan MS, Altwaijry N, Asghar MN, Raza SS, et al. Enhanced antioxidant effects of naringenin nanoparticles synthesized using the high-energy ball milling method. ACS Omega. 2022;7(38):34476–84. 10.1021/acsomega.2c04148.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Virk P, Alajmi STA, Awad M, Elobeid M, Ortashi KMO, Asiri AM, et al. Attenuating effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano formulation on arsenic induced-oxidative stress and associated genotoxicity in rat. J King Saud Univ Sci. 2022;34(60):102134. 10.1016/j.jksus.2022.102134.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”