Abstract

Medium-temperature anaerobic digestion experiments lasting for 55 days were conducted using sulfamethoxazole (SMX)-containing chicken manure in sequential batch reactors added with nano-Fe2O3 at a concentration of 300 mg·kg−1·TS or nano-C60 at a concentration of 100 mg·kg−1·TS. The effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of SMX-containing chicken manure were assessed by measuring the following indicators: biogas production by anaerobic digestion, chemical parameters, enzyme concentrations, and bacterial diversity and changes in antibiotic concentrations over time. The law of bacterial degradation of SMX was analyzed. The results showed that (1) adding either nano-Fe2O3 or nano-C60 promoted biogas production by anaerobic production from chicken manure containing different concentrations of SMX, and the cumulative biogas production in Fe2O3 and nano-C60 increased by 35.4% and 130.7%, respectively. The final cumulative biogas productions in different groups were as follows: 3,712(CK), 4,281(S1), 3,968(S2), 4,061(S3), 4,498(S4), and 4,639(S5) mL and the final concentration of SMX residues varied between 99.79% and 99.94%; (2) Bacterial abundance at the phylum level: on day 1, Firmicutes and Bacteroidota were the main dominant bacterial phyla, with relative abundances of 45.13–68.53% and 26.12–48.32%, respectively. The addition of nanoparticles increased the abundance of Bacteroidota in S4 and S5 significantly. The abundance of Bacteroidota was slightly higher in the group added with nanoparticles than in S2. On day 50, Firmicutes became the dominant bacterial phylum, and its relative abundance varied little across the groups, ranging from 90.87% to 94.54%; (3) At different stages, the bacterial community structure at the genus level was dramatically affected by substrates. As nutrients were being depleted, some bacterial communities lost their original competitive advantages. On day 5, the relative abundance of Prevotella increased. Especially, the relative abundances of Prevotella in S4 and S5 added with nanoparticles were lower than that in S2 by 8–10%. On day 15, the relative abundance of Prevotella in S2 decreased compared with the control group CK. A decrease was also observed in S4 and S5, although to a smaller extent than in S2.

1 Introduction

A transition from traditional to intensive livestock farming has been taking place in recent years, which gives rise to a stricter demand for animal health. A growing amount of antibiotics are used to treat and prevent infections in livestock husbandry [1]. In China, about 3.8 billion tons of livestock manure is produced every year. Pig manure accounts for 47%, cow manure 37%, and poultry manure 16%, of total livestock manure [2]. Along with the development of animal husbandry, the current global assumption of veterinary antibiotics has already reached about 63,151 tons, and it is expected to rise by 67% by 2030. The use of antibiotics is widespread in chicken farms to prevent and control the transmission of infectious diseases [3]. As far as animal husbandry is concerned, the most used antibiotics are tetracyclines, sulfonamides, quinolones, macrolides, and β-lactams. Li et al. [4] determined the antibiotic residues in 54 animal fecal samples collected from 9 cities in Northeast China and reported high contents of three types of antibiotics, namely, tetracyclines, sulfonamides, and quinolones. Among the antibiotic residues, the maximum detectable concentration of oxytetracycline in chicken manure was 13.39%, sulfamethoxazole (SMX) was 7.11 mg·kg−1, and enrofloxacin was 15.43 mg·kg−1. The biotoxicity of antibiotics leads to strong inhibitory effects on bacterial activity. Meanwhile, the selective pressure of antibiotics on bacteria also induces antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) or even superbacteria. ARGs can be disseminated between differential organisms through horizontal transfer. This unique mechanism increases the possibility of ARGs entering the good chain, causing threats to human health [5,6,7,8].

Anaerobic digestion is extensively used to treat organic wastes, including livestock and poultry manure. Anaerobic digestion is a series of biological processes in which microorganisms break down organic substrates in the absence of oxygen. As a high-efficiency technique for energy recovery, anaerobic digestion offers potential solutions for the biodegradation of urban solid wastes, agricultural wastes, and animal wastes [9]. In 2017, the energy potential of poultry manure was about 5.74 × 1012–6.73 × 1012 MJ, which was equivalent to 213 million tons of standard coal, 149 million tons of crude oil, and 161 billion cubic meters of natural gas. Biogas production from livestock and poultry manure can cover 4–5% of China’s annual energy demand [10]. Anaerobic digestion has also found successful applications in the treatment of wastes containing antibiotics. Zhou et al. [11] found that the erythromycin removal rate was about 99% via anaerobic digestion of pig manure. Li et al. [12] showed that anaerobic digestion could remove over 60% of quinolones from the reaction system. According to Wang et al. [13], compared with pig manure containing no antibiotics, the cumulative biogas production from manure added with 60, 100, and 140 mg·kg−1 oxytetracycline decreased by 9.9%, 10.4%, and 14.1%, respectively. Nanoparticles are materials with overall dimensions in the nanoscale, that is, under 100 nm, or materials composed of nanostructured units. Nanoparticles are superior to regular materials in performance in many application scenarios. Since nanoparticles are far smaller than most cells, they are more likely to enter the cells. Nanoparticle-containing cells are involved in continuous circulatory metabolism within the organisms, impairing the biological functions [14]. Nanoparticles are also known for their surface effects and undergo an abrupt increase in surface area, surface energy, and surface tension as the diameter decreases [15], which explains their high chemical activity and ease of reaction with other chemicals.

Sulfonamides can competitively inhibit the bacterial production of aminobenzoic acid, thereby blocking folic acid synthesis. Sulfonamides display strong antibacterial activities against Gram-positive bacteria and some Gram-negative bacteria [16,17]. Data have shown that sulfamethoxazole (SMX) is a commonly used sulfonamide in veterinary medicine in Northeast China, with the highest detectable concentration of 18 mg·kg−1 in livestock manure [18]. In this context, we performed medium-temperature anaerobic digestion experiments of SMX-containing chicken manure in sequential batch reactors using nano-Fe2O3 and nano-C60, which lasted for 55 days. Changes in biogas production from anaerobic digestion, chemical parameters, bacterial diversity, and antibiotic concentrations were analyzed. The effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion of SMX-containing chicken manure were determined, and the law of antibacterial degradation of chicken manure was obtained. Our research provides data support for the reliable operation of biogas plants and the return of biogas slurry and residues to the field. The results are conducive to maintaining ecological integrity, improving energy structure, and promoting the sustainable development of ecological organic agriculture.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Experimental equipment

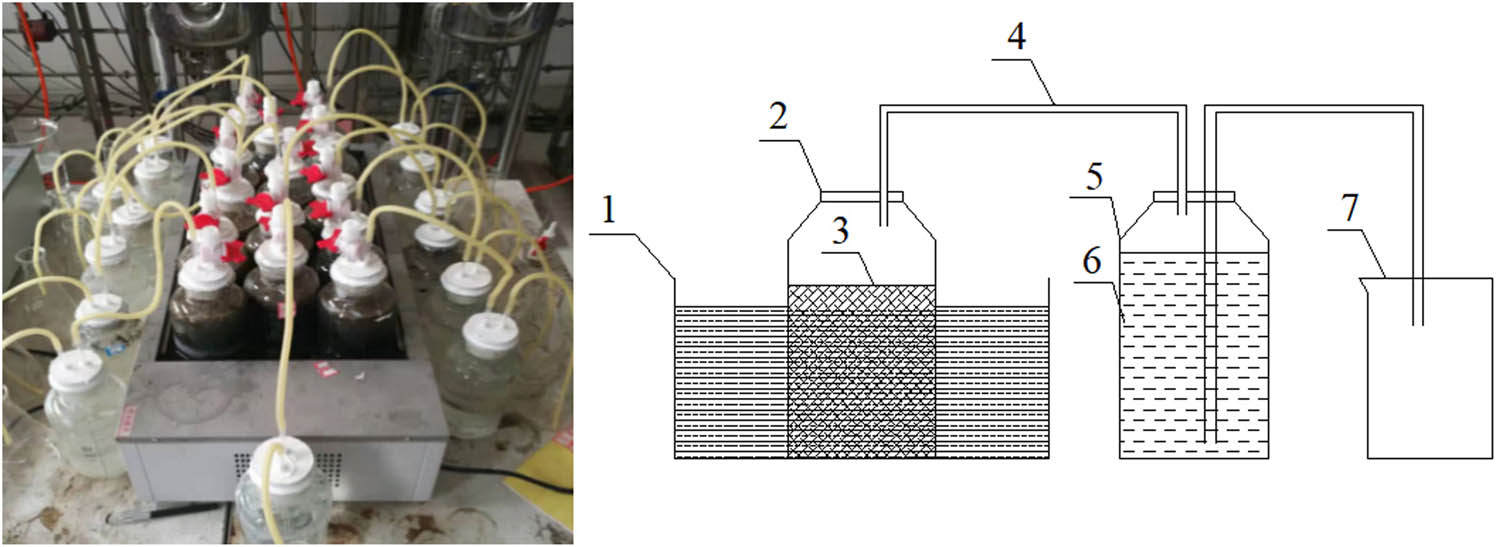

A self-designed anaerobic digestion potential test system was used, as shown in Figure 1. The test system was composed of two wild-mouth bottles (1 L) and one volumetric flask (1 L). They were, respectively, used as anaerobic digestion tanks, biogas collection cylinders, and effluent collection bottles. These components were connected to an airtight gas feed-through device with anti-aging rubber tubes.

Physical and schematic illustration of the apparatus. (1) Water bath; (2) digestion-reaction bottle; (3) mixture of chicken manure and acclimated sludge; (4) air duct; (5) gas cylinder; (6) distilled water; and (7) beaker.

2.2 Experimental materials

The chicken manure used for the present experiments was collected from a broiler breeding base. Difficult-to-degrade substances, such as egg shells, feathers, and stones, were picked out from the chicken manure. The chicken manure was preserved at 4°C in a fridge before the experiment and was confirmed to contain no antibiotics, and the pH of the chicken manure was 5.35.

The bacteria inoculated in the manure for anaerobic digestion came from residual slurry from a wastewater plant nearby. The residual slurry was transferred to a large sealed plastic container, and the temperature was maintained at about 20°C during the transport process. Back in the laboratory, 5 L of residual slurry was acclimated in a sealed plastic container at 37°C for 3 days. After that, the slurry was added with 2.5 kg of chicken manure that had already been rewarmed to room temperature and cultured for 10 days. Next, 5 kg of the kitchen waste that had been rewarmed to room temperature was taken out and added to the slurry for acclimation for 10 days, and the pH and chemical oxygen demand of bacteria inoculate were 7.12 and 1,123 mg·L−1. The characteristics of chicken manure and inoculated sludge are listed in Table 1.

Properties of the chicken manure and the acclimated sludge

| Substance | TS/% | VS/% | C/% | H/% | O/% | N/% | S/% | C/N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicken manure | 27.32 | 24.49 | 47.338 | 6.256 | 43.786 | 1.981 | 0.639 | 23.896 |

| Acclimated sludge | 2.21 | 0.87 | 19.970 | 3.270 | 74.888 | 1.180 | 0.692 | 16.930 |

2.3 Experimental methods

2.3.1 Reagents

Preparation of the nano-Fe2O3 suspension: nano-Fe2O3 (90 nm) was purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd., with a purity of 99.8%.

Preparation of the nano-C60 suspension: nano-Fe60O3 (90 nm) was purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd., with a purity of 99.9%.

SMX (98%, CAS:723-46-6) was purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., with a chemical formula of C10H11N3O3S, a relative molecular weight of 253.28, and a purity of ≥98%. SMX was preserved at 4°C in the fridge before use.

2.3.2 Experiments

Six groups were set up, and each group was added with 120 g of chicken manure and 300 g of bacteria-inoculated slurry. The maximum residue concentration of SMX was 18.00 mg·kg−1·TS and was rounded up to 20 mg·kg−1·TS. SMX was added in one dose at 50, 100, and 200% of the maximum residue concentration, respectively. In groups S4 and S5, under the SMX concentration of 20 mg·kg−1·TS, 300 mg·kg−1·TS nano-Fe2O3 and 100 mg·kg−1·TS nano-C60 were added, respectively. The amounts of each ingredient added are listed in Table 2. After feeding, deionized water was added to reach a final volume of 1 L, followed by nitrogen stripping for 2 min to remove the air. The tank was then sealed. The anaerobic digestion reactor was placed in a thermostatic water bath at 37 ± 0.5°C and shielded from light. Four replicates were set up for each group. One replicate was only used for supplementing the material lost for the sampling detection, and the final result of each group was the average of the remaining three replicates. Throughout the experiments, the slurry was stirred manually twice daily, for 1 min each time.

Experimental design

| Serial no. | Fresh chicken manure (g) | SMX(mg·kg−1·TS) | Nano-Fe2O3 (mg·kg−1·TS) | Nano-C60 (mg·kg−1·TS) | Initial concentration (μg·L−1) | Amount of acclimated sludge (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 120 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 300 |

| S1 | 120 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 400 | 300 |

| S2 | 120 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 700 | 300 |

| S3 | 120 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 1,300 | 300 |

| S4 | 120 | 20 | 300 | 0 | 700 | 300 |

| S5 | 120 | 20 | 0 | 100 | 700 | 300 |

2.4 Monitoring method

2.4.1 Analysis of physicochemical properties

The conventional indicators determined in the experiments were mainly related to the supernatant of the digestive fluid, including volatile fatty acids (VFAs) and pH value. The slurry supernatant was obtained by centrifugation of an appropriate amount of the digestion mixture using a high-speed refrigerated centrifuge at 9,000 rpm for 10 min, followed by filtration using a 0.45 μm filter membrane [6].

The physiochemical properties were detected as follows:

Volatile fatty acids: The composition and content of VFAs were determined using a gas chromatogram. The slurry supernatant was then passed through a 0.22 μm filter membrane. Into a sample vial, 1 ml of the sample was added, along with 100 μL of chromatographic grade formic grade to acidify the sample to pH < 2.

Biogas production was measured by the water displacement method once daily.

The VFA concentration was determined by gas chromatography under the following conditions: chromatographic column: stainless steel packed column manufactured by National Chromatographic R&A Center, Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, with TDX-01 as filler measuring 2 m × 3 mn; detector: thermal conductivity detector; carrier gas: He, flow rate 20 mL·min−1; current: 100 mA; attenuation: 1; detection temperature: 200°C; column box temperature: 180°C; injection temperature: 200°C.

pH value: The pH value was determined using the glass electrode method.

2.4.2 Determination of SMX content

5 g of the sample was precisely weighed and added with 20 mL of acetonitrile, and homogenized, vortexed, and ultrasonically treated for 10 min, respectively. Next, 5 g of anhydrous sodium sulfate was added, vortexed (without causing agglomeration), and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to a chicken heart bottle and added with 7 ml of isopropyl alcohol. After ultrasonic treatment for 1 min, the mixture was concentrated in a rotary evaporator at 45°C until reaching a volume of about 5 mL. The above process was repeated. The chicken heart bottle was washed with a total of 15 ml of 0.1 mol·L−1 HCl three times, and the fluid was collected into a 50 mL centrifuge tube after washing. Next, the chicken heart bottle was washed with 5 mL of n-hexane, vortexed for 2 min, and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. The lower n-hexane layer was discarded, and the remaining portion was used for purification.

Solid phase extraction was performed using an MCX column (60 mg, 3 mL), which was activated using 3 mL of methanol and 3 ml of 0.1 mol·L−1 HCl successively. Then, 8 ml of the analyte was precisely weighed and loaded. After the elution with 3 mL of 0.1 mol·L−1 HCl and 3 mL of 50% methanol in aqueous solution and draining of the waste liquid, elution was performed again using 5 mL of 5% methanol in aqueous ammonia. Nitrogen stripping was performed at 50°C, and the analyte was redissolved using 0.2% formic acid in aqueous solution: methanol (1:1). After passing through a 0.22 μm organic filter membrane, the analyte was bottled and loaded for detection.

2.4.3 Determination of enzyme activity

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, the corresponding enzyme kit (Shanghai Enzyme-Linked Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China) was used to determine the activities of amylase, cellulase, protease, urease and dehydrogenase. The procedures for different types of enzymes are the same as follows:

An appropriate amount of anaerobic digestion liquid was broken using an ultrasonic cell crusher (750 W, 40% power, 5 s ultrasound, 9 s interval) in an ice bath for 90 min, and the broken sample was centrifuged at a low temperature (4°C) at a rotational speed of 10,000 rpm for 20 min. The supernatant was taken and stored at −20°C for measurement. Standard product holes were set, and standard product holes were added at different concentrations (400, 200, 100, 50, 25, 0 IU·L−1) 50 μL of enzyme-labeled reagent; A blank control hole and a sample hole to be measured were set up respectively. The sample and enzyme-labeled reagent are not added to the blank control hole, and the other steps are the same. The sample diluent 40 μL is added to the sample hole to be measured first, and then 10 μL of the sample to be measured is added, that is, the final dilution of the sample is 5 times. 100 μL of enzyme-labeled reagent was added to each well, the plate was sealed with the sealing plate film and incubated at 37°C for 60 min. The sealing plate film was removed, the liquid was discarded, and shaken dry, each hole was filled with 20 times diluted washing liquid, left for 30 s and discarded, repeated 5 times and pat dried. 50 μL of color developer A was added to each well first, then 50 μL of color developer B was added to each well, shocked and mixed, color development was carried out at 37°C in the dark for 15 minutes, and 50 μL of termination solution was added to terminate the reaction, at this time, the blue turned to yellow immediately, and the determination was performed within 15 min. The absorbance of each hole was measured at 450 nm wavelength and the standard curve was drawn.

2.4.4 Metagenomic sequencing

Appropriate amounts of chicken manure and inoculated sludge were taken and stored at −20°C to be measured. Metagenomic sequencing was completed by Shanghai Meiji Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd. The samples were extracted using a FastDNA® Spin Kit for Soil extraction kit according to the instructions. Illumina’s NovaSeq sequencing platform was used for metagenomic sequencing. After the optimized sequences were spliced and assembled, the high-quality reads of each sample were compared with the non-redundant gene set (95% identity), and the abundance information of the genes in the corresponding sample was calculated. The amino acid sequence of the non-redundant gene set was compared with the CARD database to obtain the annotation information of the antibiotic resistance function corresponding to the gene, and then, the abundance of the antibiotic resistance function was calculated using the sum of the gene abundance corresponding to the antibiotic resistance function.

2.5 Data analysis

In the experiment, the physical and chemical indicators were measured in triplicate. Data were analyzed for significance and correlation using single-factor analysis of variance and multiple comparisons in SPSS v.18.0 software, evaluating the significant differences between each experimental treatment. The least significant difference method (LSD; a = 0.05) was used for multiple comparisons of the mean values. All data graphs were plotted using Origin-8.0.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of SMX-containing chicken manure

3.1.1 Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic biogas production from SMX-containing chicken manure

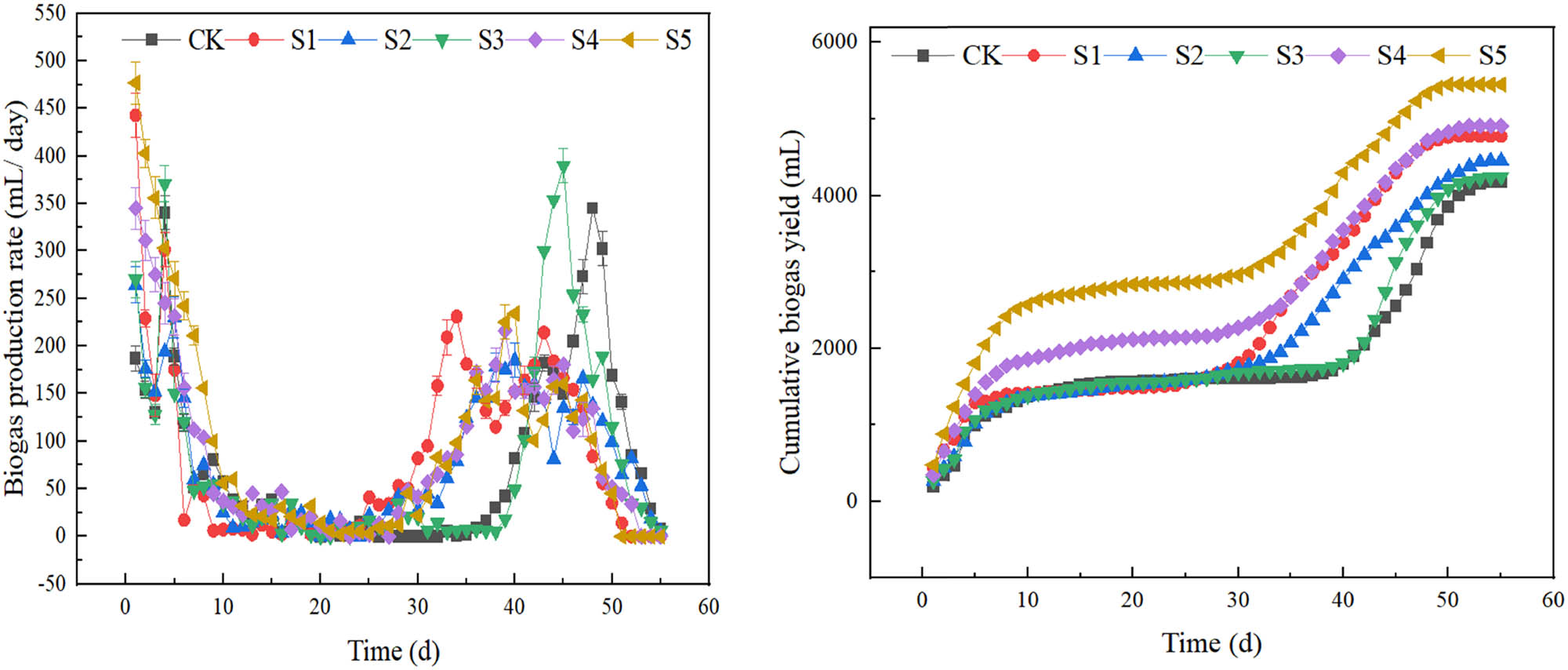

Changes in daily biogas production and cumulative biogas production from the anaerobic digestion of SMX-containing chicken manure in the presence of nanoparticles are shown in Figure 2. In all six groups, two peaks of biogas production occurred during 55 days of anaerobic digestion. The first peak lasted from day 1 to day 10 of the experiment. Once the experiment was started, hydrolytic acid-producing bacteria broke down the dissolved organic matter at a fast rate. At this stage, there was an adequate nutrient supply for anaerobic digestion by methanogens, which was coupled with an appropriate pH value to sustain a high methanation efficiency. In S1–S3 without the addition of nanoparticles, the peak was reached on day 1, the biogas production being 443 ± 23, 264 ± 19, and 270 ± 19 mL, respectively. The first peak lagged behind in the blank control group CK compared with the other groups and occurred on day 5, the value being 340 ± 18 mL. The peak occurred as early as day 1 in S4 added with nanoparticles, the biogas production reaching 345 ± 22 mL. The first peak also occurred on day 1 in S5 added with nanoparticles, reaching 472 ± 22 mL. The cumulative biogas productions in the six groups were ranked as follows: 2,570(S5)>1,861(S4)>1,420(S1)>1,375(S2)>1,372(CK)>1,114(S3) mL. It can be seen that both nano-Fe2O3 and nano-C60 promoted anaerobic digestion to produce biogas from chicken manure containing varying concentrations of SMX. In the first 10 days of the digestion reaction, the cumulative biogas production increased by 35.4% and 130.7% in S4 and S5, respectively. After the first peak, the biogas production reached a stagnation in all groups. NaOH was added from day 21 to day 23 to adjust the pH value to above 6.5. The biogas production was restored to the previous rate in different groups after day 24, and the second peak came soon afterwards. At this stage, insoluble macromolecular organics, including cellulose, were degraded by hydrolytic acid-producing bacteria into VFAs, providing nutrients for methanogens. The biogas production rate increased rapidly in S1 and S2. That is, the second peak of 231 mL was reached on day 34 in S1, and the second peak of 185 mL was reached on day 40 in S2. For S3, the second peak of 390 mL occurred on day 45, and for the CK group, the second peak of 345 mL occurred on day 48. As seen above, compared with S1 and S2, CK and S3 had an extended delay in reaching either peak, though the peaks were larger in amplitude and shorter in duration for CK and S3. A study [7] showed that sulfonamides exert a solubilizing action by damaging extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) and cell membranes while enhancing acid and acetic acid production. This may be one reason for the high biogas production efficiency in S1 and S2. In contrast, due to a higher SMX concentration, bacterial inhibition was observed in S3. Another peak of biogas production of 272 ± 15 ml and 310 ± 8 mL appeared on day 30 and day 33 in S1 and S2, respectively. The peak of 230 ± 11 mL was reached on day 35 in the CK group. In S4 and S5 added with nanoparticles, the second peak was reached on day 39 and day 40, respectively, the value being 216 ± 12 mL and 225 ± 4 mL, respectively. The maximum daily biogas production rate at the second peak was lower in S4 and S5 compared with the other four groups. The final cumulative biogas productions in the six groups were as follows: 4,182(CK), 4,774(S1), 4,459(S2), 4,245(S3), 4,909(S4), and 5,450(S5) mL. As a result, the conversion of carbon dioxide to methane was accelerated, and the delay in the initiation of biogas production was shortened, resulting in higher methane production.

Effects of nanoparticles on changes in daily biogas production rate and cumulative biogas production from anaerobic digestion of SMX-containing chicken manure.

Ma et al. [19] fed sulfadimidine continuously into the anaerobic digestion experiments of cow manure. The results showed that after six days of experiment, the biogas production efficiency increased significantly and the biogas production was finally increased by 44.8%. Their results agreed with ours. That is, the addition of antibiotics did not change the overall biogas production. After acclimation, the biogas production efficiency of the anaerobic digestion system was improved considerably. Wen et al. [20] showed that 50 mg·L−1 SMX increased methane production by high-temperature anaerobic digestion by 22%, probably because SMX acted as a substrate. Currently, there are two explanations for antibiotics promoting biogas production by anaerobic digestion. The first is that antibiotics act as substrates to provide a carbon supply for bacteria [21,22]; the second is that antibiotics have stimulating effects on the bacterial community [23]. Although SMX was almost completely degraded in the earlier stage of the experiment, the theoretical contribution of SMX as a substrate was far lower than the increment of biogas production. This result indicates the positive role of SMX on the bacterial community. Our biogas production data showed that SMX at a residue concentration promoted anaerobic digestion to produce biogas. But as the SMX concentration increased, the biogas production-promoting effect was weakened, while the bacterial inhibitory effect of antibiotics was gradually manifested. It is safe to say that SMX residues in chicken manure were inadequate to cause a negative impact on the anaerobic digestion system.

Adding nano-Fe2O3 and nano-C60 nanoparticles had a promoting effect on biogas production by anaerobic digestion of chicken manure containing different concentrations of SMX. The biogas production efficiency increased considerably in the first 10 days, and the cumulative biogas production in the groups added with nanoparticles was higher compared with those not added with nanoparticles. Nanoparticles nano-Fe2O3 and nano-C60 deliver extraordinary performance barely comparable with other materials due to their unique structural features. The ultrastructure of the nanoparticles gives rise to surface effects, which manifest as an abrupt increase in nanoparticles’ surface area, surface energy, and surface tension as the diameter decreases. From the above-mentioned reasons, nanoparticles have higher chemical activities compared with other materials and hence a higher possibility of reacting with other chemical substances. Nanoparticles are considered to serve as the mediator promoting gas production by bacteria that hydrolyze the substrates. Another study shows that nanoparticles help increase the metabolic rate and hydrogen yield of substrates involved in anaerobic fermentation. Adding an appropriate concentration of nanoparticles into an anaerobic fermentation hydrogen production system can increase biogas yield by elevating the hydrogenase activity and optimizing the composition of the anaerobic microbial community. The dissolution of metal ions from nano-Fe2O3 and nano-C60 is considered one of the most common and also the most important pathways by which nanoparticles affect the anaerobic digestion of slurry. Fe3+ is an essential trace element for the anaerobic growth and metabolism and plays a positive role within an appropriate range of concentrations. One study arrived at similar conclusions, believing that at a lower concentration of nano-Fe2O3, the released Fe3+ was chelated with the negatively charged residues in the EPS, reducing the ionic toxicity.

3.1.2 Effects of nanoparticles on the changes in pH and total volatile fatty acids (TVFA) levels during anaerobic digestion of SMX-containing chicken manure

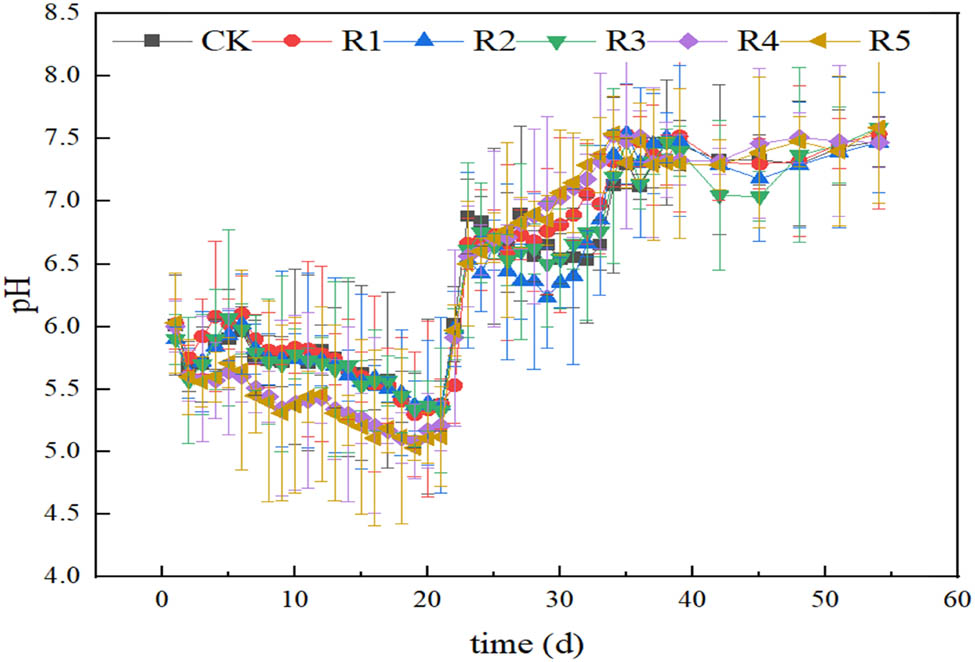

The effects of nanoparticles on the changes in pH value and TVFA levels during anaerobic digestion of chicken manure containing different concentrations of SMX are shown in Figures 3 and 4, respectively. The changes in the pH value during anaerobic digestion under different SMX concentrations are shown in Figure 3. After the first peak (day 1 to day 5), the anaerobic digestion system in each group began to be acidified. There was a downward trend in the pH value from day 6 to day 20. The pH value of the CK group was the lowest among the four groups, while those of S1 and S2 were close to each other and higher than that of S3. The pH values in S4 added with 300 mg·kg−1·TS nano-Fe2O3 and in S5 added with 100 mg·kg−1·TS nano-C60 were even lower. On day 9, the pH values in these two groups were 5.35 ± 0.7 and 5.31 ± 0.6, respectively, indicating that adding nanoparticles contributed significantly to substrate degradation. After the pH adjustment, the pH value decreased in all groups. Later, the pH value first increased on day 30 and day 32 in S1 and S2, respectively. In these two groups, the pH value was restored to above 7 on day 34 and day 38, respectively. From day 34 to day 39, the pH values of CK and S3 were significantly lower than those of the other two groups until an obvious rise in the pH value occurred after day 39. Such changes in pH value were consistent with the variations in biogas production.

Effects of nanoparticles on changes in pH value during anaerobic digestion of the SMX-containing chicken manure.

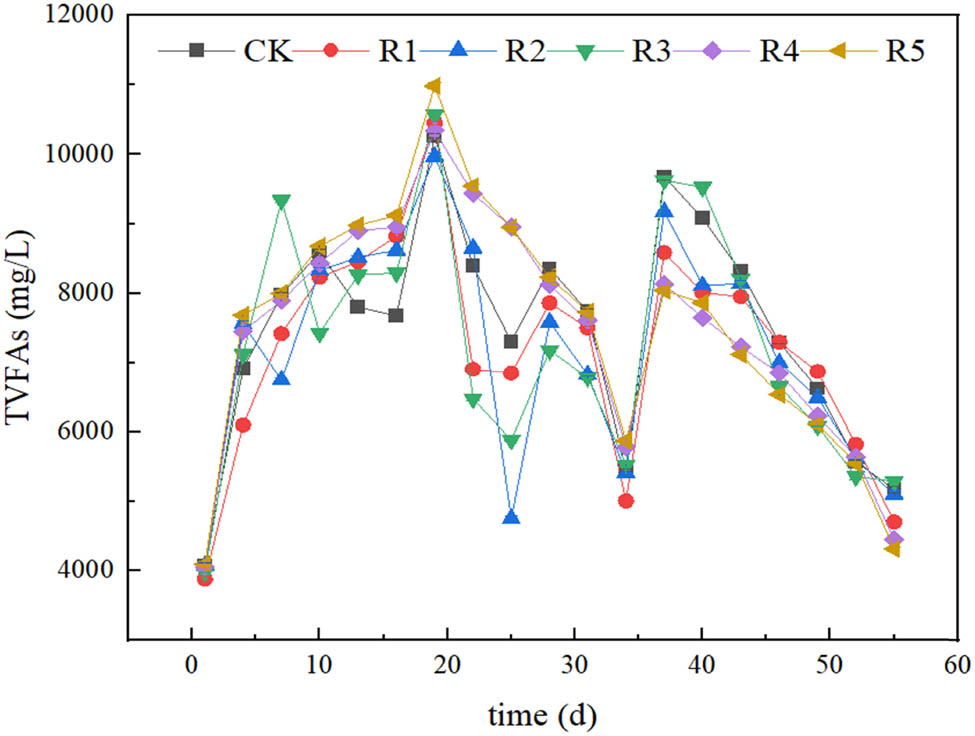

Effects of nanoparticles on changes in TVFA levels during anaerobic digestion of the SMX-containing chicken manure.

VFAs are the products of hydrolytic acid-producing bacteria as well as the nutrients for methanogens. The VFA levels were dynamically changing in the anaerobic digestion system. The changes in the TVFA levels in the anaerobic digestion system under different SMX concentrations are shown in Figure 4. In different groups, the TVFA levels first increased and then decreased in the earlier stage of the experiment. The TVFA levels were lower in S1 in the earlier stage, indicating a higher substrate utilization rate in the bacterial community in this group. From day 1 to day 10, the TVFA levels in all groups increased rapidly, and it was consistently higher in S4 and S5 compared with the other four groups. It was inferred that the presence of nano-Fe2O3 and nano-C60 promoted the hydrolysis of chicken manure containing SMX. The ultrastructure of the nanoparticles facilitated substrate degradation by hydrolytic acidifying bacteria, resulting in a higher TVFA levels in the first 10 days compared with other groups. Later, the pH value decreased, and the cumulative biogas production from TVFAs also decreased. Another peak was reached in S1 and S2 on day 30, the values being 8,104.00 and 7,689.55 mg·L−1, respectively. The corresponding pH values were 6.53 and 6.42, respectively. The biogas production increased continuously in CK and S3 until peaking on day 34, with the values of 10,140.23 and 9,187.95 mg·L−1, respectively. The corresponding pH values were 6.73 and 6.61, respectively. At this stage, biogas production had reached a stagnation point. CK and S3 had not yet recovered from the acid inhibition on methanogens. Studies have shown that the derivatives of some antibiotics still display biotoxicity, and the products of SMX degradation deserve further investigation [24,25]. Latif et al. [26] found that when the pH value was 5.5 in the anaerobic digestion system, the intense accumulation of propionic acid and butyric acid led to a 50% reduction in methane production, while the organic matter not completely degraded accounted for an increasing proportion. When the pH value was below 5.5, the methanogenic community shrank in size considerably and gave way to the propionic acid-utilizing community. In the present study, the pH level was even lower after the addition of nano-Fe2O3 and nano-C60, the values being 5.08 ± 0.4 and 5.03 ± 0.2, respectively, which agreed with the findings with TVFAs. Addition of 300 mg·kg−1·TS nano-Fe2O3 and 100 mg·kg−1·TS nano-C60 promoted organic acid production from substrate hydrolysis, resulting in a lower pH value of the system. After the addition of NaOH, the pH value of each group was restored to 6.65 to 6.74 on day 26. As biogas production was resumed in each group, the TVFA levels decreased rapidly, and the biogas production rate reached the maximum in each group since day 30. From day 34 to day 37, another rapid increase in TVFAs was observed, indicating that the hydrolysis rate of difficult-to-degrade substances, such as cellulose, was higher than the nutrient utilization rate of methanogens. As the substrate concentration decreased after day 37, the density of hydrolytic acid-producing bacteria decreased as well, accompanied by a gradual reduction in the TVFA concentrations. From day 25 to day 34, the TVFA levels remained low, although the biogas production rate was inconsistent with the low TVFA levels. The low TVFA levels in the system were not due to the utilization of methanogens. Enrofloxacin might have a negative impact on hydrolytic acid-producing bacteria [27]. One study [28] showed that the bacterial inhibition effect of antibiotics reduced methane production without causing acetic acid accumulation, and the working mechanism may be related to the non-competitive inhibition of the enzymes. That is, the enzyme-substrate complexes for antibiotics binding deactivated the enzyme sites, thus inhibiting methane production from acetic acid.

3.1.3 Effects of nanoparticles on the degradation rate of SMX

The SMX degradation rates by anaerobic digestion of chicken manure added with nanoparticles are listed in Table 3. SMX was decomposed rapidly from day 1 to day 5. The SMX degradation rates in the groups added with nano-Fe2O3 and nano-C60 were slightly higher than those in the other three groups. On day 5, the SMX degradation rates reached up to 99.64–99.81% in the two groups added with nanoparticles; on day 15, the SMX degradation rates were as high as 99.78–99.94%. In the earliest stage of the experiment, SMX was almost completely removed, indicating the low durability of SMX in the anaerobic digestion system, which agreed with the results of other researchers. Mohring et al. [29] found that SMX was almost completely removed during the 34-day medium-temperature anaerobic digestion experiments in pig manure. Wen et al. [30] estimated the half-life of SMX to be 3 days at a concentration of 50 mg·L−1 during the high-temperature anaerobic digestion experiments in batch reactors. It has been found that in the absence of nanoparticles, absorption is the primary removal pathway for SMX in the anaerobic digestion system [31]. We performed solid phase extraction for the samples to be analyzed in the present study, and the estimated SMX concentration was the total concentration (SMX in the solid and liquid phases combined). The reactors were shielded from light during the experiments, and therefore, the influence of photodegradation was excluded. Medium-temperature anaerobic digestion was effective in removing SMX, according to our results. Addition of 300 mg·kg−1·TS nano-Fe2O3 or 100 mg·kg−1·TS nano-C60 further degraded SMX on the basis of the conventional medium-temperature anaerobic digestion. The results suggested that the nanoparticles acted synergistically with SMX in promoting anaerobic metabolism.

Changes in SMX concentrations

| 0 days (μg·L−1) | 5 days (μg·L−1) | Degradation rate on 5 days (%) | 15 days (μg·L−1) | Degradation rate on 15 days (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 400 | 1.45 | 99.64 | 0.89 | 99.78 |

| S2 | 700 | 1.61 | 99.77 | 0.79 | 99.89 |

| S3 | 1,300 | 1.39 | 99.89 | 0.81 | 99.94 |

| S4 | 700 | 1.34 | 99.80 | 0.53 | 99.92 |

| S5 | 700 | 1.22 | 99.81 | 0.42 | 99.93 |

3.1.4 Effects of SMX on the activities of different enzymes

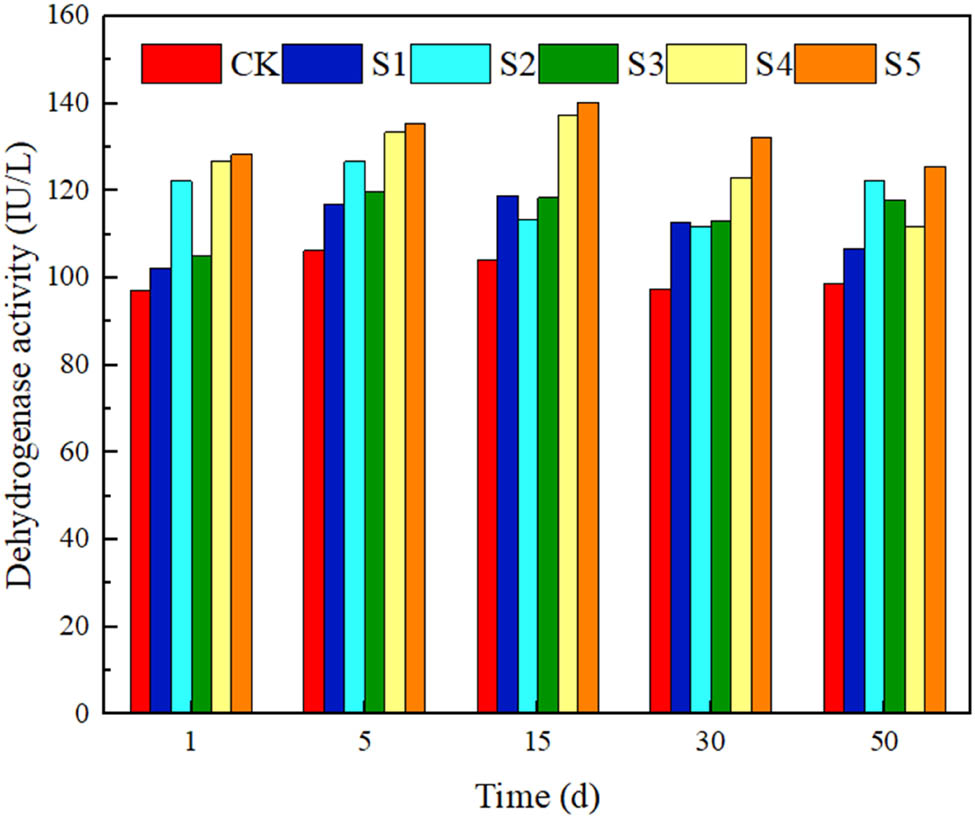

Anaerobic digestion to produce biogas is the result of stepwise enzymatic reactions mediated by bacterial communities with different functions. Dehydrogenase activity is an important indicator characterizing microbial state. Changes in dehydrogenase activity during anaerobic digestion under different SMX concentrations are shown in Figure 5. Throughout the experiments, the dehydrogenase activity in the SMX-containing groups was consistently higher than in the control group. The mean dehydrogenase activities in different groups were ranked as follows: 132.44(S5) > 126.52(S4) > 119.38(S2) > 114.88(S3) > 111.57(S1) > 100.78(CK) IU·L−1. Besides, the dehydrogenase activity was the highest by adding 300 mg·kg−1·TS nano-Fe2O3 then adding 100 mg·kg−1·TS nano-C. Yang et al. [32] performed a pig manure composting experiment and found that 95 mg·kg−1·TS SMX activated microbial dehydrogenase activity, but inhibited dehydrogenase at a concentration of 50 mg·kg−1·TS. They believed that in an environment with high SMX concentration, the growth and proliferation of resistant bacteria require a large nutrient supply, resulting in an elevated dehydrogenase activity. In contrast, a low SMX concentration in the environment promoted the accumulation of superoxides, which further had a toxic effect on the microbes.

Changes in dehydrogenase activity at different SMX concentrations.

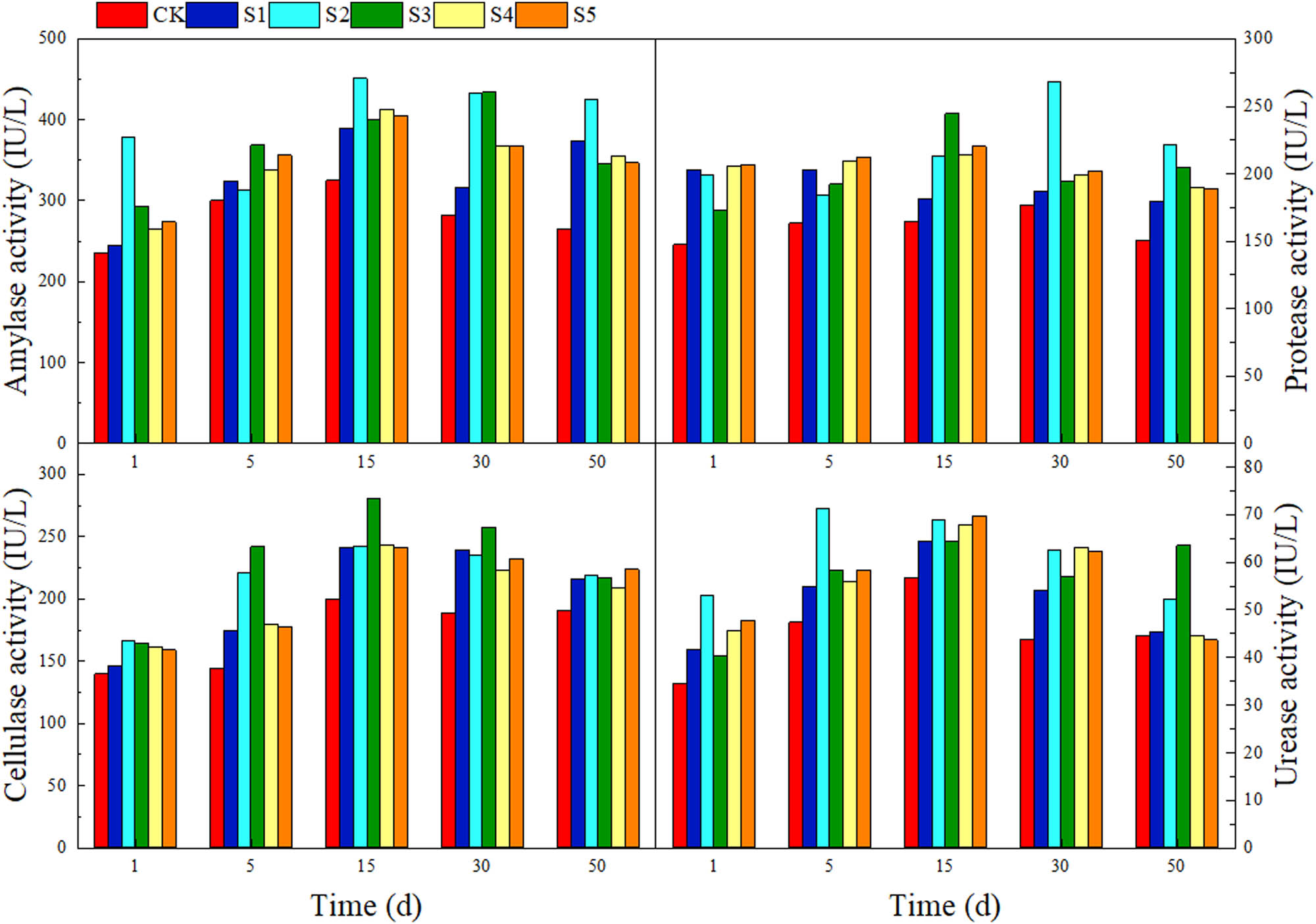

The hydrolysis rate has a limiting effect on the overall anaerobic reaction rate and directly affects the biogas production potential. The hydrolytic state can be intuitively represented by the hydrolase activity. Based on the main components of the substrates, we monitored the activities of four extracellular hydrolases at different states, namely, amylase, cellulase, protease, and urease. The changes in hydrolase activities during anaerobic digestion under different SMX concentrations are shown in Figure 6. Throughout the experiments, the mean amylase activities in different groups were ranked as follows: 400.44(S2) > 368.41(S3) > 349.88(S5) > 347.88(S4) > 329.68(S1) > 281.65(CK) IU·L−1. The mean amylase activities were always higher in the groups added with antibiotics compared with the control group. In contrast, adding nanoparticles barely had any promoting effect. In the earlier stage of the experiment, the amylase activity in S2 on day 1 was significantly higher than that in the other three groups. However, there was a rapid increase on day 5, and the amylase activity in S2 was lower than that in S1 and S3. One reason may be that the antibiotics accelerated amyloysis by hydrolytic bacteria. As the substrate was being rapidly depleted, the bacterial population density decreased, leading to a lower amylase activity.

Changes in activities of hydrolytic enzymes at different SMX concentrations.

Chicken manure is rich in difficult-to-degrade substances, such as coarse fibers, and cellulase activity can reflect the level of cellulose degradation in the anaerobic digestion system. During the experiments, the mean cellulase activities in different groups were ranked as follows: 232.44(S3) > 216.84(S2) > 206.64(S4) > 203.32(S5) > 203.50(S1) > 172.62(CK) IU·mL−1. At different stages of the experiment, the cellulase activities in the groups added with antibiotics were significantly higher than those in the control group. The cellulase activity first increased and then decreased in different groups. As the SMX concentration increased, the cellulase activity increased as well, indicating that SMX simulated the bacterial secretion of cellulase. However, the cellulase concentrations in the groups added with nanoparticles were lower than S2, indicating that nanoparticles only had a limited promoting effect on fibers. On day 15, the maximum cellulase activity reached 199.64, 240.92, 242.39, 280.85, 243.4, and 241.2 IU·mL−1 in the six groups, respectively. The crystalline region of cellulose is difficult to degrade due to its dense structure, and therefore it takes more time to be decomposed into glucose [33]. Cellulose is the main contributing substrate for the second biogas production peak. For this reason, the cellulase activities in the middle and later stages of the experiment were significantly higher than those in the earlier stage. On day 50, the cellulase activities decreased in all groups, and there was a narrowing of intergroup differences, indicating that the hydrolysis of cellulose was completed over time.

Crude protein accounts for a large proportion of the total organic matter in chicken manure. Therefore, protease activity was the key indicator requiring monitoring in our study. Throughout the experiments, the mean protease activities in different groups were ranked as follows: 216.99(S2) > 206.12(S5) > 203.44(S4) > 201.75(S3) > 190.81(S1) > 160.62(CK) IU·L−1. SMX had an obvious promoting effect on protease activity. In the earlier stage of the experiment, the protease activity in S1 was significantly higher than that in S2 and S3. This is probably because SMX inhibited proteolytic bacteria at the concentrations of 20 and 40 mg·kg−1·TS. As the inhibitory effect of SMX on the bacteria was diminished, a highly active state of the bacteria was maintained in S2 and S3 in the middle and later stages of the experiment. This situation was consistent with the variation in the activities of cellulase and amylase. In contrast, the presence of nanoparticles had no obvious impact on protease activity.

Urease converts the C–N bond in amides into ammonia to maintain the nitrogen cycle. In the experiments, the mean urease activities in different groups were ranked as follows: 61.59(S2) > 56.69(S3) > 56.38(S5) > 55.46(S4) > 52.06(S1) > 45.46(CK) IU·mL−1. The urease activity was continuously lower in the control group than in the groups added with antibiotics, which agreed with the results for other extracellular enzymes. SMX did have a stimulating effect on urease activity. Han et al. [34] found that SMX-containing biogas residues dramatically improved the soil urease activity.

3.2 Effects of nanoparticles on anaerobic communities digesting SMX-containing chicken manure

3.2.1 Effects of nanoparticles on bacterial communities

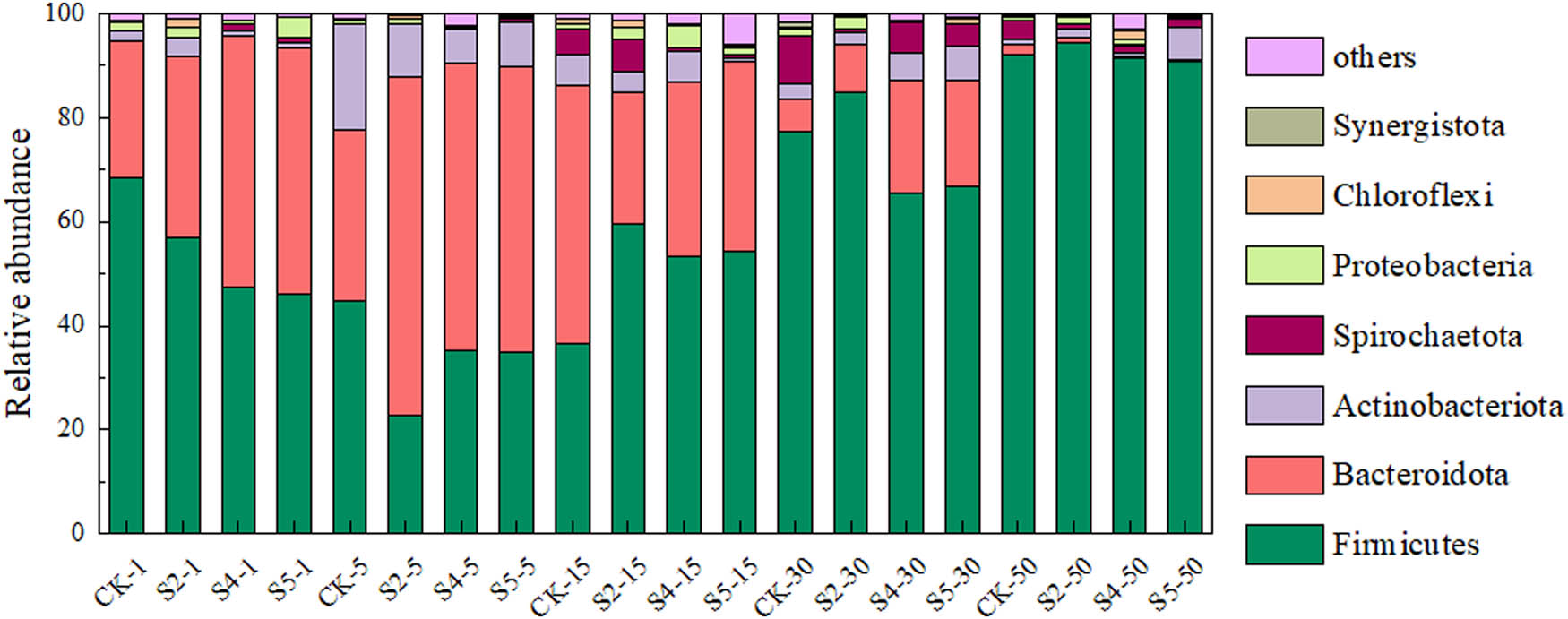

Relative abundances of bacteria at the phylum level during anaerobic digestion of chicken manure containing SMX are shown in Figure 7. The bacterial community structures in CK, S2, S4, and S5 were similar at different stages of the experiment on the phylum level. The bacterial community was mainly composed of the following seven phyla: Bacteroidota, Actinobacteriota, Spirochaetota, Proteobacteria, Chloroflexi, and Synergistota. Firmicutes, Bacteroidota, and Proteobacteria are common bacterial communities in anaerobic digestion reactors and can metabolize a variety of substrates. These bacteria are mainly engaged in the hydrolysis of macromolecular substances and organic acid production. Firmicutes can produce large amounts of extracellular enzymes, including protease, cellulase, and lipase [35,36]. Bacteroidota plays an important role in decomposing carbohydrates and proteins into acetic acid and NH3. Some genera belonging to the Proteobacteria have the capacity of reducing sulfates into H2S. Spirochaetota, Synergistota, and Chloroflexi can decompose the organic acids produced by hydrolytic acidifying bacteria into acetic acid and H2 [37]. On day 1, Firmicutes and Bacteroidota were the main dominant bacterial phyla, with relative abundances of 45.13–68.53% and 26.12–48.32%, respectively. Addition of nanoparticles increased the abundances of Bacteroidota in S4 and S5 significantly. On day 5, the relative abundances of Actinobacteriota and Bacteroidota increased dramatically, reaching 6.34–20.28% and 33.11–65.49%, respectively. The abundance of Bacteroidota was slightly higher in the groups added with nanoparticles compared with S2. This is because nanoparticles acted as interfacial mediators to promote the increase in the abundance of Bacteroidota. From day 15 to day 20, Firmicutes gained an increasing competitive advantage as the reaction proceeded, while the relative abundance of Bacteroidota kept decreasing, probably due to a lack of nutrient supply. However, the abundance of Bacteroidota in S4 and S5 added with nanoparticles was higher compared with the other groups. On day 50, Firmicutes became the dominant phylum, and there was a narrowing of intergroup differences in its abundance. The relative abundance of Firmicutes varied between 90.87% and 94.54%.

Effects of nanoparticles on structural changes of the bacterial community involved in the anaerobic digestion of SMX-containing chicken manure on the phylum level.

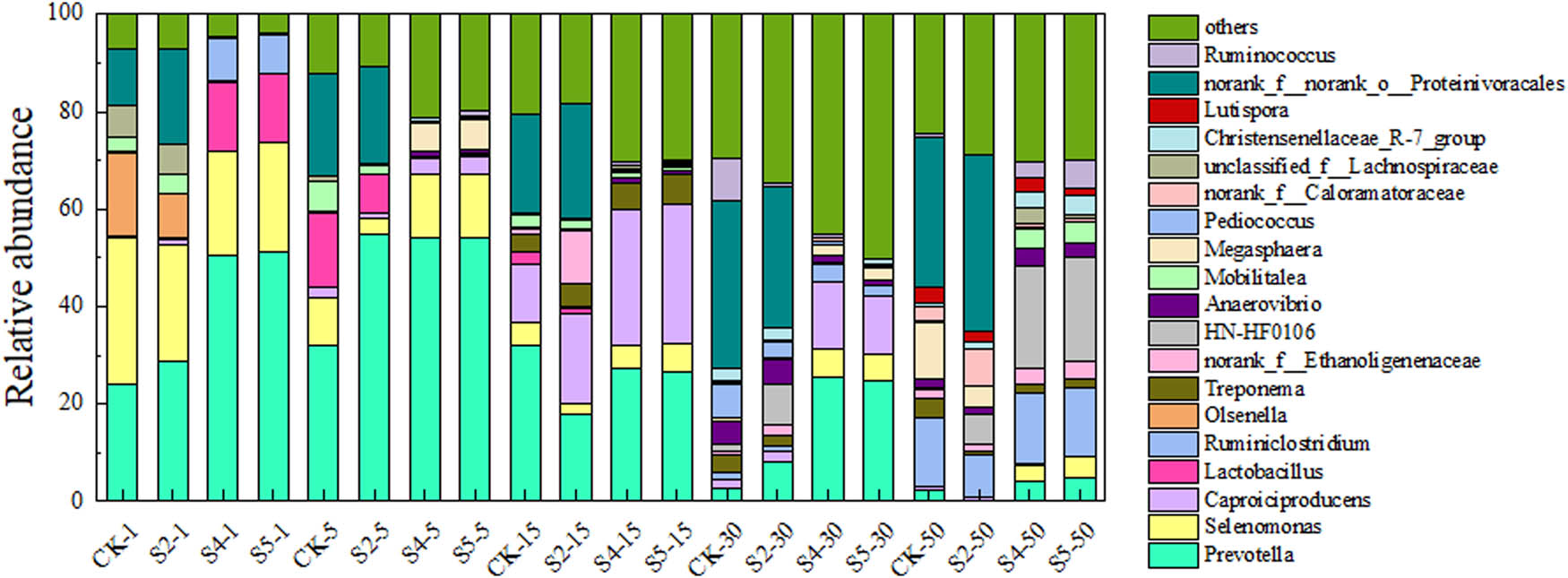

As shown in Figure 8, at different stages of the experiment, the bacterial community structure at the genus level was dramatically affected by substrates. As nutrients were being depleted, some bacterial communities lost their original competitive advantages. On day 5, the relative abundance of Prevotella belonging to the phylum Bacteroidota increased, indicating a high bacterial resistance to SMX. Especially, the relative abundance of Prevotella in S4 and S5 added with the nanoparticles was lower than that of S2 by 8–10%. On day 15, compared with the control group CK, the relative abundance of Prevotella decreased in S2 as well as in S4 and S5, although the decrease was smaller than in S2. This is probably because the easy-to-degrade nutrients in the substrates had been rapidly decomposed from day 1 to day 10. The hydrolysis acidification process was more intense at the earlier stage in S4 and S5, resulting in a deficiency of nutrients in the substrates, which explains the reduced relative abundance of Prevotella. At this stage, the relative abundances of Treponema were higher in S2, S4, and S5, reaching 4.37% to 6.31%. Treponema belonging to the phylum Spirochaetota can convert H2 and CO2 into acetic acid [38], corresponding to a lower pH value in S2, S4, and S5. This result agreed with the previous analysis. Both Caproiciproducens and norank_f__Ethanoligenenaceae belong to the phylum Firmicutes. Their relative abundances in S4 and S5 were higher than those of CK, and this situation persisted until day 30. Caproiciproducens can convert sugars into H2 to provide an energy supply for hydrotrophic methanogens [39,40]. On day 50, the relative abundance of HN-HF0106 in CK was higher than that in S2, S4, and S5, indicating that SMX residue inhibited the activity of this bacterial genus. In contrast, Ruminiclostridium displayed a higher adaptability to SMX residue. Ruminiclostridium belonging to the phylum Bacteroidota can synthesize cellulose-degrading enzymes to decompose lignocellulose. On day 50, the easy-to-degrade organic matter had already been depleted, and the bacteria using difficult-to-degrade organic matter as the main nutrient supply prevailed.

Effects of nanoparticles on structural changes of the bacterial community involved in the anaerobic digestion of SMX-containing chicken manure on the genus level.

4 Conclusions

Our study provided the first experimental evidence that the addition of nano-Fe2O3 and nano-C60 can promote the anaerobic gas production of livestock and poultry manure with different concentrations of SMX cycle but also advance the development of engineering. The limitation of this study is that we only used pig manure as a representative of livestock and poultry manure and selected the antibiotic SMX as a representative of antibiotics. The SMX degradation rates showed similar variation trends in S1 to S5 during the anaerobic digestion of chicken manure. SMX was rapidly decomposed from day 1 to day 5. The SMX degradation rates in the groups added with nano-Fe2O3 and nano-C60 were slightly higher than those in the other three groups. On day 5, the SMX degradation rates reached up to 99.64–99.81% in the two groups added with nanoparticles; on day 15, the SMX degradation rates were as high as 99.78 to 99.94%. At different stages of the experiment, the bacterial community structure at the genus level was dramatically affected by substrates. As nutrients were being depleted, some bacterial communities lost their original competitive advantages. On day 5, the relative abundance of Prevotella increased. Especially, the relative abundance of Prevotella in S4 and S5 added with nanoparticles was lower than that in S2 by 8–10%. On day 15, the relative abundance of Prevotella in S2 decreased compared with the control group CK. A decrease was also observed in S4 and S5, though to a smaller extent than in S2. On day 50, the relative abundance of HN-HF0106 in the CK group was higher than that in S2, S4, and S5, indicating that SMX residue inhibited the activity of this bacterial genus. In contrast, Ruminiclostridium displayed a higher adaptability to SMX residue. Filling these knowledge gaps will not only improve our understanding of the effect of nanomaterials on gas production in anaerobic digestion but also advance the development of antibiotic degradation.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52206255), the Youth Science and Technology Talent Lift Program of Gansu Province (GXH20220530-14), the Youth Science Foundation Project of Lanzhou Jiaotong University (2020018、2020011),and Gansu Province Youth Science Fund project (No.22JR11RA148).

-

Author contributions: Xiaofei Zhen: writing – original draft, conceptualization; Han Zhan: writing – review and editing; Ruonan Jiao – writing – original draft and conceptualization; Ke Li – investigation; Wenbing Wu: methodology; Lei Feng – supervision; Tie Du – validation.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Balat M, Balat H. Biogas as a renewable energy source—a review. Energy Sources Part A. 2009;31(14):1280–93. 10.1080/15567030802089565.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Gurmessa B, Pedretti EF, Cocco S, Cardelli V, Corti G. Manure anaerobic digestion effects and the role of pre-and post-treatments on veterinary antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes removal efficiency. Sci Total Environ. 2020;721:1375–83. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137532.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Zhang QQ, Ying GG, Pan CG, Liu YS, Zhao JL. Comprehensive evaluation of antibiotics emission and fate in the River Basins of China: source analysis, multimedia modeling, and linkage to bacterial resistance. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49(11):6772–82. 10.1021/acs.est.5b00729.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Li YX, Zhang XL, Li W, Lu XF, Liu B, Wang J. The residues and environmental risks of multiple veterinary antibiotics in animal faeces. Environ Monit Assess. 2012;185(3):2211–20. 10.1007/s10661-012-2702-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Li DC, Gao JF, Dai HH, Wang ZQ, Duan WJ. Long-term responses of antibiotic resistance genes under high concentration of SMXofloxacin, sulfadiazine and triclosan in aerobic granular sludge system. Bioresour Technol. 2020;312:123567. 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123567.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Sui QW, Zhang JY, Chen MX, Tong J, Wang R, Wei YS. Distribution of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in anaerobic digestion and land application of swine wastewater. Environ Pollut. 2016;213:751–9. 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.03.038.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Sun W, Gu J, Wang XJ, Qian X, Peng HL. Solid-state anaerobic digestion facilitates the removal of antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements from cattle manure. Bioresour Technol. 2019;274:287–95. 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.09.013.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Zhi SL, Zhou J, Zhao R, Yang FX, Zhang KQ. Fate of antibiotic resistance genes and driving factors in the anaerobic fermentation process of livestock manure. J Agric Eng. 2019;35(01):195–205.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Yin FB, Dong HG, Ji C, Tao XP, Chen YX. Effects of anaerobic digestion on chlortetracycline and oxytetracycline degradation efficiency for swine manure. Waste Manag. 2016;56:540–6. 10.1016/j.wasman.2016.07.020.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Jha P, Schmidt S. Reappraisal of chemical interference in anaerobic digestion processes. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;75:954–71. 10.1016/j.rser.2016.11.076.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Zhou Q, Li X, Wu SH, Zhong YY, Yang CP. Enhanced strategies for antibiotic removal from swine wastewater in anaerobic digestion. Trends Biotechnol. 2021;39(1):8–11. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2020.07.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Li N, Liu HJ, Xue YG, Wang HY, Dai XH. Partition and fate analysis of fluoroquinolones in sewage sludge during anaerobic digestion with thermal hydrolysis pretreatment. Sci Total Environ. 2017;581–582:715–21. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.12.188.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Wang XJ, Pan HJ, Gu J, Qian X, Gao H, Qin QJ. Effects of oxytetracycline on archaeal community, and tetracycline resistance genes in anaerobic co-digestion of pig manure and wheat straw. Environ Technol. 2016;37(24):3177–85. 10.1080/09593330.2016.1181109.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Zhang YF, Jin C, Ma CW, Yang YJ. Research status of the cytotoxic effects of several nanomaterials. J Second Mil Med Univ. 2010;31(11):1234–8. 10.3724/SP.J.1008.2010.01234.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Wang T, Zhang D, Dai LL, Dong B. Research progress on effects of nanoparticles on wastewater/sludge anaerobic digestion system. J Environ Eng. 2015;33(6):1–5. 10.13205/j.hjgc.201506001.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Bílková Z, Malá J, Hrich K. Fate and behaviour of veterinary sulphonamides under denitrifying conditions. Sci Total Environ. 2019;695:133824. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.133824.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Al-Ahmad A, Daschner FD, Kümmerer K. Biodegradability of cefotiam, ciprofloxacin, meropenem, penicillin G, and sulfamethoxazole and inhibition of waste water bacteria. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1999;37(2):158–63. 10.1007/s002449900501.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] An J, Chen HW, Wei SH, Gu J. Antibiotic contamination in animal manure, soil, and sewage sludge in Shenyang, northeast China. Environ Earth Sci. 2015;74(6):5077–86. 10.1007/s12665-015-4528-y.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Ma JW, Shu LX, Mitchell SM, Yu L, Zhao QB, Frear C. Effects of different antibiotic operation modes on anaerobic digestion of dairy manure: Focus on microbial population dynamics. J Environ Chem Eng. 2021;9(4):105–21. 10.1016/J.JECE.2021.105521.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Wen Q, Yang S, Chen Z. Mesophilic and thermophilic anaerobic digestion of swine manure with sulfamethoxazole and norfloxacin: Dynamics of microbial communities and evolution of resistance genes. Front Environ Sci Eng. 2021;15:94. 10.1007/S11783-020-1342-X.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Dantas G, Sommer MOA, Oluwasegun RD, Church GM. Bacteria subsisting on antibiotics. Science. 2008;320:100–3. 10.1126/science.1155157.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Huang L, Wen X, Wang Y, Zou YD, Ma BH, Liao XD, et al.Effect of the chlortetracycline addition method on methane production from the anaerobic digestion of swine wastewater. J Environ Sci. 2014;26(10):2001–6. 10.1016/j.jes.2014.07.012.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Zhi SL, Li Q, Yang FX, Yang ZJ, Zhang KQ. How methane yield, crucial parameters and microbial communities respond to the stimulating effect of antibiotics during high solid anaerobic digestion. Bioresour Technol. 2019;283:286–96. 10.1016/j.biortech.2019.03.083.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Lamshöft M, Sukul P, Zühlke S, Spiteller M. Behaviour of 14C-sulfadiazine and 14C-difloxacin during manure storage. Sci Total Environ. 2010;408(7):1563–8. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.12.010.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Zhong S, Wang XQ, Ma BH, Zou YD, Liao XD, Yang JH, et al. Effects of sulfadimidine and its addition method on anaerobic digestion of pig manure. J Domest Anim Ecol. 2020;41(01):68–74.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Latif MA, Mehta CM, Batstone DJ. Influence of low pH on continuous anaerobic digestion of waste activated sludge. Water Res. 2017;113:42–9. 10.1016/j.watres.2017.02.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Zhu KY, Zhang L, Wang XX, Mu L, Li CJ, Li AM. Inhibition of norfloxacin on anaerobic digestion: Focusing on the recoverability and shifted microbial communities. Sci Total Environ. 2021;752:141733. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141733.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Li WH, Shi YL, Gao LH, Liu JM, Cai YQ. Occurrence, distribution and potential affecting factors of antibiotics in sewage sludge of wastewater treatment plants in China. Sci Total Environ. 2013;445:306–13. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.12.050.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Mohring SAI, Strzysch I, Fernandes MR, Kiffmeyer TK, Tuerk J, Hamscher G. Degradation and elimination of various sulfonamides during anaerobic fermentation: a promising step on the way to sustainable pharmacy? Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43(7):2569–74.10.1021/es802042dSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Wen Q, Yang S, Chen Z. Mesophilic and thermophilic anaerobic digestion of swine manure with sulfamethoxazole and norfloxacin: Dynamics of microbial communities and evolution of resistance genes. Front Environ Sci Eng. 2021;15:94. 10.1007/S11783-020-1342-X.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Wang L, Qiang Z, Li Y, Ben WW. An insight into the removal of fluoroquinolones in activated sludge process: Sorption and biodegradation characteristics. J Environ Sci. 2017;56:263–71. 10.1016/j.jes.2016.10.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Yang J, Gu J, Zhang YW. Effects of sulfamethoxazole on enzyme activity and microbial community functional diversity during pig manure composting. Acta Sci Circumst. 2014;34(4):965–72. 10.13671/j.hjkxxb.2014.0157.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Yang Q, Ju MT, Li WZ. Research progress of methane production by anaerobic digestion of straw. Trans Chin Soc Agric Eng. 2016;32(14):232–42. 10.1016/J.JWPE.2023.103719.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Han J, Zhang C, Cheng J, Wang F, Qiu L. Effects of biogas residues containing antibiotics on soil enzyme activity and lettuce growth. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2019;26(6):6116–22. 10.1007/s11356-018-4046-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Chen Y, Jiang X, Xiao K, Nan S, Zeng RJ, Zhou Y. Enhanced volatile fatty acids (VFAs) production in a thermophilic fermenter with stepwise pH increase–Investigation on dissolved organic matter transformation and microbial community shift. Water Res. 2017;112:261–8. 10.1016/j.watres.2017.01.067.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Zhao X, Liu J, Liu J, Yang FY, Zhu WB, Yuan XF, et al. Effect of ensiling and silage additives on biogas production and microbial community dynamics during anaerobic digestion of switchgrass. Bioresour Technol. 2017;241:349–59. 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.03.183.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Guo JB, Ostermann A, Siemens J, Dong RG, Clemens J. Short term effects of copper, sulfadiazine and difloxacin on the anaerobic digestion of pig manure at low organic loading rates. Waste Manag. 2012;32(1):131–6. 10.1016/j.wasman.2011.07.031.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Wang W, Xie L, Luo G, Zhou Q, Angelidaki I. Performance and microbial community analysis of the anaerobic reactor with coke oven gas biomethanation and in situ biogas upgrading. Bioresour Technol. 2013;146:234–9. 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.07.049.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Ta DT, Lin CY, Ta TMN, Chu C-Y. Biohythane production via single-stage fermentation using gel-entrapped anaerobic microorganisms: Effect of hydraulic retention time. Bioresour Technol. 2020;317:123986. 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123986.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Qin Y, Li L, Wu J, Xiao BY, Hojo T, Kubota K et al. Co-production of biohydrogen and biomethane from food waste and paper waste via recirculated two-phase anaerobic digestion process: Bioenergy yields and metabolic distribution. Bioresour Technol. 2019; 276:325–34. 10.1016/j.biortech.2019.01.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan