Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

-

Hernández-Abril Pedro Amado

Abstract

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are key factors in cellular damage and disease development. Nanoparticles (Nps) have demonstrated significant potential in medicine due to their unique properties, encapsulation of bioactive compounds within Np enhances their stability and efficacy. Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens (OBP) is a plant characterized by its richness in bioactive antioxidant compounds. This investigation focused on encapsulating an OBP extract (OBPE) within zein nanoparticles (NpZ) and evaluating the preservation of its bioactivity and antioxidant potential. The encapsulation process successfully maintained bioactivity and efficiently extracted bioactive compounds. Comprehensive physicochemical characterization of OBPE-loaded NpZ was performed, including FTIR, DLS, ζ-potential, SEM microscopy, and UV-Vis spectroscopy. Antioxidant activity was evaluated using DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP assays, revealing high antioxidant capacity in OBPE-loaded NpZ. Results revealed the influence of zein concentration on Np characteristics, such as size, charge, and morphology. The extraction method proved effective in preserving bioactive compounds from OBP. Successful OBPE encapsulation within the zein matrix demonstrated NpZ potential as an effective carrier for bioactive compounds. This study highlights the effective extraction and encapsulation of OBPE, emphasizing the importance of NpZ in bioactive antioxidant delivery. Further research on therapeutic efficacy and targeted delivery of OBPE-loaded NpZ in biological models is warranted.

1 Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly reactive molecules generated as byproducts of normal oxygen metabolism in biological systems. These include free radicals such as superoxide and hydrogen peroxide, which induce cellular damage through the oxidation of essential cellular components, including proteins, lipids, and DNA [1]. The imbalance between ROS production and endogenous antioxidant defense mechanisms results in oxidative stress, a condition implicated in various pathological processes, including aging, cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, and cancer development [2].

Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens (OBP), commonly known as Purple Basil, is distinguished by its significant medicinal and antioxidant properties. The plant synthesizes diverse bioactive compounds, including phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and other phytochemicals that exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activities, presenting substantial potential for pharmaceutical and food applications [3,4,5,6]. The Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract (OBPE) combined with NpZ offers a promising strategy to counteract ROS-induced damage. OBPE’s diverse bioactive compounds demonstrate potent antioxidant properties, effectively neutralizing ROS and providing cellular protection against oxidative damage. Furthermore, extracts from the Ocimum basilicum family have demonstrated anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties, contributing to oxidative stress reduction and health promotion [7,8]. However, these bioactive compounds often exhibit limited stability and bioavailability, which constrains their therapeutic efficacy [2,9,10].

Nanoparticles (Nps) have emerged as significant structures in scientific and technological advancement due to their distinctive physicochemical properties and versatile applications. These nanoscale materials exhibit unique behavioral characteristics that differentiate them from their bulk counterparts. Their advantageous properties, including enhanced surface area-to-volume ratio, increased surface reactivity, and superior colloidal stability, position them as promising candidates for diverse applications spanning medicine, electronics, energy systems, and agricultural technologies [11,12,13].

Nanotechnology has transformed modern medicine through revolutionary advancements in disease diagnostics, targeted therapeutics, and controlled drug delivery systems [13,14,15]. The implementation of nanosensors and nanodevices has significantly enhanced biomarker detection sensitivity, while drug-loaded Nps enable precise therapeutic targeting. Moreover, stimulus-responsive drug release mechanisms optimize therapeutic efficacy while minimizing adverse effects [16,17].

The encapsulation of bioactive compounds within Nps represents a strategic innovation for enhancing compound stability and therapeutic efficacy. This methodology provides protection against degradative and oxidative processes, enhances compound solubility, enables controlled release kinetics, and facilitates targeted transport across biological barriers [2,9,10]. Furthermore, the incorporation of natural extracts into polymeric Nps has demonstrated significant potential for amplifying their therapeutic benefits [18,19].

Nps have also been shown to be an effective tool in combating oxidative stress [20]. Nps can be designed to have inherent antioxidant properties, such as zinc oxide and selenium, and it can be loaded with antioxidant compounds derived from natural extracts [21,22]. These antioxidant Nps can protect cells from oxidative damage by neutralizing ROS and restoring the redox balance in the body. Furthermore, Nps can improve the stability and bioavailability of antioxidant compounds, enhancing their therapeutic efficacy [9,23,24].

Nps have been shown to be an effective tool in mitigating oxidative stress [20]. They can be engineered to possess inherent antioxidant properties, such as zinc oxide and selenium Nps, or be loaded with antioxidant compounds derived from natural extracts [21,22]. These antioxidant Nps protect cells from oxidative damage by neutralizing ROS and restoring redox balance in the body. Moreover, Nps can enhance the stability and bioavailability of antioxidant compounds, improving their therapeutic efficacy [9,23,24].

Among the materials used for encapsulation, zein, a protein derived from corn, stands out as an attractive option. Zein is biocompatible, biodegradable, and non-toxic, making it a safe material for pharmaceutical and food applications. Additionally, its proline-rich structure allows for easy modification, facilitating the incorporation of various bioactive compounds and improving their stability [25,26].

This study has significantly contributed to the scientific understanding of the relationship between physicochemical properties and antioxidant activity. The findings highlight the potential of Nps and natural extracts as promising therapeutic strategies for combating oxidative stress. Additionally, this research provides a foundational framework for future studies and clinical applications aimed at improving overall health and well-being.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Experimental cultivation protocol

The seeds of the OBP plant were acquired from a local supplier, HortaFlor, Rancho Los Molinos, located in Tepoztlán, México, ensuring their authenticity and genetic quality. By utilizing these seeds as a starting point, the cultivation process of OBP was carried out, resulting in a new generation of plants. This process was successively repeated for three generations. From the first generation onward, a cultivation approach was implemented that excluded the use of chemical additives, synthetic materials (e.g., pesticides and herbicides), and artificial fertilizers. This practice was adopted to safeguard the integrity of the final product, ensuring the absence of undesirable elements that could affect its chemical composition or bioactive properties. Additionally, special attention was given to the proper management of the plants throughout their growth cycle, including monitoring pH levels, substrate moisture content, and controlling light exposure. Furthermore, sustainable agronomic practices such as crop rotation and water conservation techniques were employed to promote environmentally conscious cultivation. Figure 1 depicts an OBP plant before the leaves are harvested.

The plant OBP, also known as Purple Basil.

2.2 Preparation and processing of OBP leaves

Leaves of OBP were obtained from the third generation of cultivated plants. After harvesting, the leaves were thoroughly washed with distilled water to remove surface impurities. The drying process was carried out in a controlled environment at 25°C with regulated humidity. Once fully dried, the leaves were manually crushed, removing any non-leaf material. The leaves were then ground using a ceramic mortar, and the resulting powder was sieved through a 180 μm mesh. The entire process is illustrated in Figure 2. The final powder was stored under appropriate conditions for subsequent characterization and experimental use.

Preparation and processing of OBP leaves.

2.3 Sample EBOP extraction and preparation

The resulting OBP powder (100 mg) was added to a flask containing 20 mL of 50% ethanol. The mixture was allowed to interact for 5 min, during which the solution turned purple. The flask was then placed in an ultrasonic bath at 60°C and 40 kHz for 10 min, resulting in a color change to light green. The entire process is illustrated in Figure 3. The solution was then filtered using filter paper and stored at 2°C for subsequent use. No extracts older than 2 days were used in any experiment or characterization.

Preparation and processing of OBPE.

2.4 Preparation of zein nanoparticles (NpZ)

NpZ were prepared using a modified antisolvent procedure [20]. Initially, 2.5 μmol of zein (CAS 9010-66-6, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MI, USA) was dissolved in 10 mL of a binary solvent mixture of ethanol and water (90:10 v/v) to create a stock solution. Subsequently, 1, 2, and 4 mL of the stock solution were added dropwise to 9 mL of deionized water, resulting in the formation of NpZ1, NpZ2, and NpZ3 samples, respectively. This process was conducted under continuous magnetic stirring (1,000 rpm) for 30 min to facilitate ethanol evaporation in the samples. The samples were centrifuged at 8,000 rpm, and the pellet was resuspended in 9 mL of deionized water. The samples were then stored at 4°C for subsequent physicochemical characterization. Additionally, a portion of the final dispersions was lyophilized for 48 h to obtain solid Np powder samples, which were stored for further characterization.

2.5 Preparation of zein–OBPE-loaded nanoparticles (NpZOBP)

For the OBPE-loaded samples, 4 mL of the zein stock solution was added dropwise to the aqueous media. The aqueous media consisted of 1, 2, or 4 mL of OBPE in a volumetric flask, diluted with deionized water to a final volume of 9 mL. The resulting samples were designated as NpZOBP1, NpZOBP2, and NpZOBP3. These samples underwent the same treatment as the other NpZ samples (Figure 4).

Synthesis process of NpZOBPE.

2.6 Quantification of total phenol content

The quantification of total phenol content was performed using a modified Folin–Ciocalteu assay, as reported by Luque-Alcaraz et al. [20]. Test tubes were prepared by adding 50 μL of each sample, followed by the addition of a carefully measured mixture consisting of 3.0 mL of distilled water, 250 μL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, 750 μL of 20% Na2CO3, and 950 μL of distilled water. The reaction was initiated by incubating the test tubes for 3 min, after which 1.0 mL of sodium carbonate solution was added. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 60 min, ensuring the complete development of color and subsequent formation of a stable complex. To determine the phenolic content, a calibration curve was constructed using gallic acid as the standard. The concentration of gallic acid equivalents per gram of dry matter (mg GAE/g d.w.) was calculated based on the absorbance values obtained from the samples, which were compared to the calibration curve. To ensure the accuracy and reproducibility of the results, all analyses were performed in triplicate, and the average values were reported.

2.7 Determination of total flavonoids

The aluminum chloride (AlCl3) assay, as reported by Luque-Alcaraz et al. [20], was employed to quantify the flavonoid content in the samples. In this assay, each sample (0.5 mL) was mixed with 2 mL of distilled water and 0.15 mL of a 10% (w/v) AlCl3 solution. After a 10-min incubation in the dark at room temperature, 1 mL of 1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and 1.2 mL of distilled water were added to the mixture. Following an additional 15-min incubation in the dark at room temperature, the absorbance of the resulting solution was measured at 430 nm using a microplate reader (Veloskan™ LUX, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The calibration curve for quantification was prepared using quercetin as the standard. Hence, the results were expressed as milligrams of quercetin equivalent per gram of dry weight (mg QE/g d.w.).

2.8 Antioxidant capacity using the ABTS assay

The method involved measuring the reduction of green/blue coloration resulting from the reaction between ABTS and the antioxidants present in the sample. To generate the ABTS cation radical, 19.2 mg of ABTS was dissolved in 5 mL of distilled water. The ABTS radical was produced by oxidizing ABTS (7.0 mM) with potassium persulfate (K₂S₂O₈, 4.95 mM) in the dark for 12 h at 25°C. The ABTS solution was then diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 0.2 M, pH 7.4) to achieve an absorbance of 0.7, measured at 734 nm. Subsequently, 20 mL of the sample and 200 mL of the ABTS solution were combined and allowed to react for 30 min. The absorbance was measured at 734 nm using a microplate reader (Veloskan™ LUX, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The trapping activity was reported as ABTS radical inhibition (%), as detailed in Eq. 1 [27], to determine the scavenging capacity.

where Abs0 is the control absorbance (water), Abs1 is the absorbance of the sample with ABTS, and Abs2 is the absorbance of the water with ABTS.

2.9 FRAP assay

The ferric reduction ability was assessed using the ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay. The FRAP reagent was prepared in acetate buffer (pH 3.6) and consisted of a 10 mM solution of 2,4,6-tri(2-pyridyl)-s-triazine (TPTZ) in 40 mM HCl, mixed with a 20 mM iron(iii) chloride solution in a ratio of 10:1:1 (v/v/v) [28]. The samples were diluted to various concentrations, and 20 µL of each sample was combined with 280 µL of the FRAP reagent. A Trolox standard solution was prepared for reference. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 30 min, after which the absorbance was measured at 638 nm using a microplate reader (Veloskan™ LUX, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The results were expressed as micromoles of Trolox equivalent per gram of dry sample (µmol TE/g d.w.).

2.10 DPPH radical scavenging assay

DPPH radical scavenging assays were conducted following the methodology described by Hu et al. [29]. The treatments were first diluted to various concentrations. Subsequently, 50 µL of each concentration was mixed with 200 µL of a methanolic DPPH solution at a concentration of 0.4 mM in a 96-well microplate. The reaction was allowed to proceed in the dark at 25°C for 30 min. Afterward, the absorbance was measured at 515 nm using a microplate reader (Veloskan™ LUX, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). A Trolox standard solution was prepared and assayed under the same conditions [27].

2.11 Morphology and size of Nps

A field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM) (JEOL JSM-7800F, Pleasanton, CA, USA) was utilized. Before deposition on an aluminum film, the samples were diluted at a ratio of 1:10. The particle size distribution was determined using ImageJ software (version 1.58t). The size distributions were obtained from a population of 200 particles.

2.12 Characterization of the absorption spectra

The absorption spectra of the samples were obtained using a GENESYS 10S UV-Vis spectrophotometer. The samples were diluted with ultrapure water (1:10) for subsequent measurement. A quartz cell was used as the sample holder. A baseline correction was performed by subtracting the absorption spectrum of water from the sample spectra.

2.13 Hydrodynamic size determination and ζ-potential measurements

A dynamic light scattering (DLS) instrument, the Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, United Kingdom), was used to obtain hydrodynamic size distributions. The ζ-potential measurements were conducted using the same instrument. The samples were diluted 1:10 in ultrapure water, and the measurements were performed at 25°C. All measurements were performed in triplicate.

2.14 Spectrometer setup for FTIR analysis

FTIR spectra were collected using a Spectrometer (Perkin Elmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a single attenuated total reflectance (ATR) diamond. The spectra were recorded in the range of 400–4,000 cm−1.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Absorption spectroscopy of OBPE

Figure 5 shows the absorption spectrum of OBPE, which exhibits a peak around 370 nm. This absorption peak aligns with previous reports for the Ocimum basilicum family [30]. The observed absorption curve can be attributed to the presence of phenolic compounds in OBPE, specifically flavonoids, which typically exhibit absorbance in the range of 300–450 nm [31,32]. These compounds are known for their antioxidant activity. The color of OBPE and the displayed absorption band provide evidence of successful extraction from OBP, thereby preserving its bioactive compounds.

UV-Vis spectra of the OBPE.

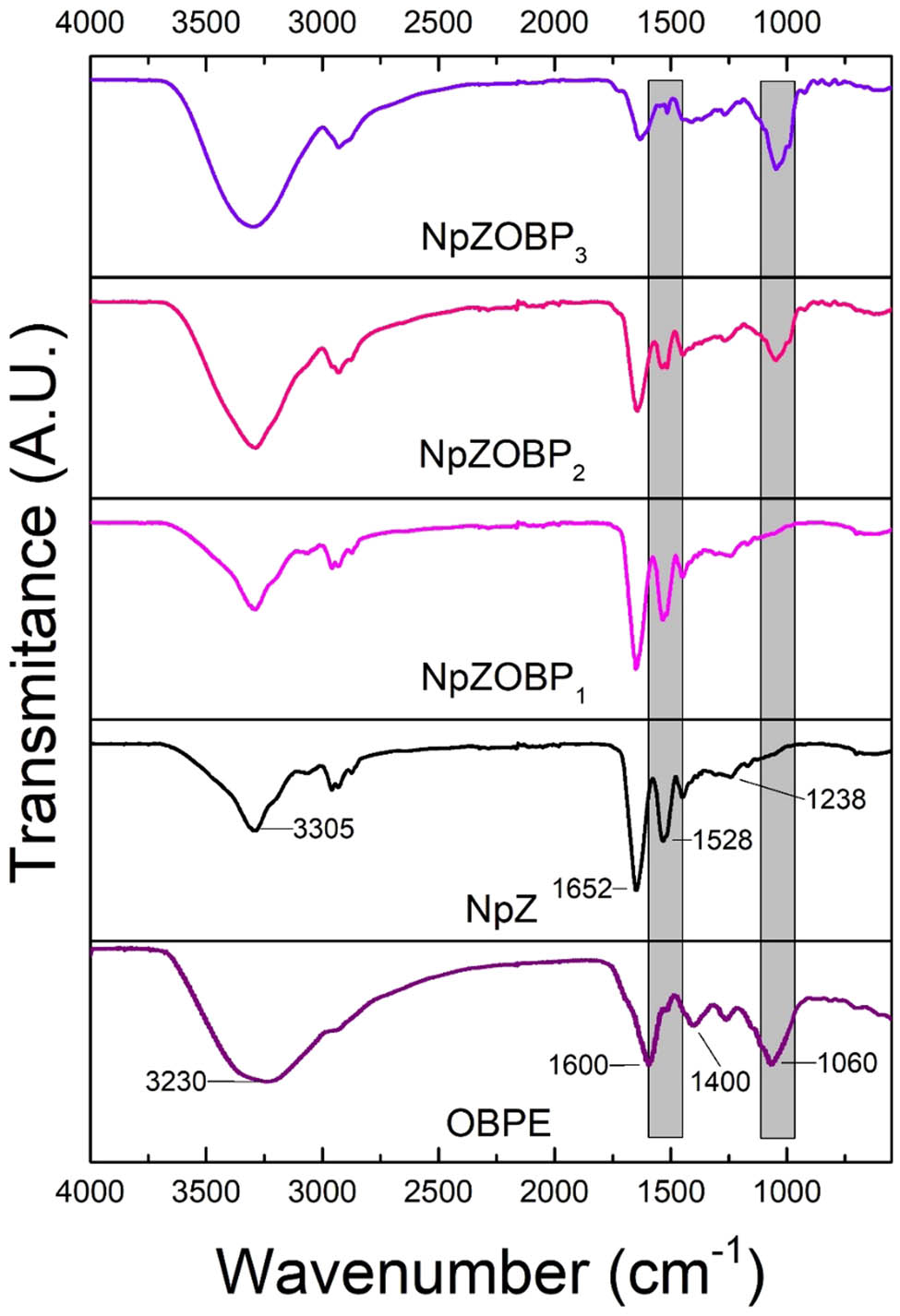

3.2 FTIR characterization of NpZ loaded with OBP

In Figure 6, a broad band centered around 3,230 cm−1 is observed, corresponding to the O–H stretching vibration present in the phenolic and alcoholic groups of flavonoids [33]. The peak at 1,600 cm−1 is assigned to the C═C stretching vibration in the aromatic rings of the phenolic groups [12]. Additionally, a significant peak is observed at approximately 1,400 cm−1 associated with the C═O stretching vibration. Furthermore, a signal is detected at 1,060 cm−1, indicative of the C–O–C stretching vibration in the ester groups [34].

Infrared spectra of the OBPE, NpZ, and NpZ with OBPE (NpZOBP1, NpZOBP2 and NpZOBP3). The shaded gray areas represent the ranges in which the tracked signals are located.

In the infrared spectrum of NpZ, characteristic bands related to amides I, II, and III are observed. The band at 1,652 cm−1 corresponds to C═O stretching, the band at 1,528 cm−1 is attributed to N–H bending, and the band at 1,238 cm−1 corresponds to C–N stretching. Additionally, a distinct peak is detected at 3,305 cm−1, indicating the axial stretching of OH groups and N–H bonds [20].

The NpZOBP1 sample, characterized by a lower concentration of OBPE, does not exhibit significant changes in the detected signals, which can be attributed to the low concentration of OBPE in the sample. In contrast, the NpZOBP2 sample displays a distinct peak at 1,652 cm−1, attributed to C═O stretching, a characteristic feature of OBPE. Furthermore, the intensity and broadening of the signal at 3,200 cm−1 indicate the involvement of vibrational stretching of the O–H bond, which is also present in OBPE. This is consistent with findings reported in various studies on plants of the Ocimum family [35,36]. These changes are even more evident in the NpZOBP3 sample, where they are more pronounced and prominent. These findings provide compelling evidence for the successful incorporation of OBPE into the zein polymer matrix. Interestingly, these spectral modifications are consistent with results observed in similar systems involving the encapsulation of plant extracts in zein. For instance, in the encapsulation of orange extract (OE) in NpZ, researchers reported shifts in key bands, such as the migration of the O–H stretching band from 3,299 to 3,287 cm−1 and the C═O stretching band shifting from 1,651 to 1,645 cm−1 [20]. These shifts were attributed to the formation of hydrogen bonds between the extract and the polymer matrix, which suggests the formation of stable systems via non-covalent interactions [20]. Similarly, in our study, the broadening and shifting of the O–H stretching band in the NpZOBP3 sample indicates the potential formation of hydrogen bonds between OBPE and the zein matrix, further supporting the successful incorporation of OBPE into the Nps. Notably, the FTIR spectra reveal discernible signals associated with the functional groups of OBPE, further suggesting the retention of OBPE’s bioactivity within the loaded nanoplatform.

3.3 Surface charge and hydrodynamic diameter analysis

The results presented in Table 1 are consistent with those of the previous reports. For instance, a similar zein concentration to that of the NpZ2 sample was employed in previous studies, where statistically equivalent values were reported for both the hydrodynamic diameter and surface charge [20]. Furthermore, it was observed that as the zein concentration increases, the resulting Np also exhibit an increase in size, which has been previously reported [37].

Hydrodynamic diameter (nm) and zeta potential (mV) values of zein Nps: NpZ1, NpZ2, and NpZ3

| NpZ1 | NpZ2 | NpZ3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrodynamic diameter (nm) | 112.97 ± 2.57a | 159.29 ± 5.42b | 171.17 ± 3.13c |

| ζ-potential (mV) | 20.33 ± 1.43a | 21.65 ± 1.37a | 23.73 ± 0.32b |

| PDI | 0.116 | 0.174 | 0.129 |

a,b,cDifferent literals per row indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05).

The larger hydrodynamic diameter of NpZ3 offers distinct advantages in terms of its encapsulation capacity, making it an optimal choice for maximizing the loading of OBPE and ensuring its potential therapeutic efficacy. Notably, the observed differences in ζ-potential values among the NpZ1, NpZ2, and NpZ3 samples highlight the significant influence of zein concentration on the surface charge of the Np. The larger ζ-potential exhibited by NpZ3 holds crucial importance in maintaining the colloidal stability of the Np. A higher ζ-potential promotes enhanced electrostatic repulsion between particles, effectively reducing aggregation and enhancing the colloidal system’s long-term stability. Moreover, a higher ζ-potential is known to facilitate cellular internalization by promoting stronger electrostatic interactions with the cell surface. This enhanced cellular uptake potential has promising implications for the targeted delivery and improved therapeutic efficacy of the Np. The results underscore the influence of zein concentration on the Np size, with NpZ3 exhibiting a larger size while retaining the ability for passive cellular internalization. This combination of characteristics positions NpZ3 as a superior candidate for encapsulating OBPE.

Upon comparing the results of NpZOBP1 with the OBPE-free NpZ3 sample, a significant increase in the hydrodynamic diameter was observed, which can be attributed to the formation of hydrogen bonds between the OBPE molecules and the zein polymer matrix, leading to an increase in particle size. This effect has been previously reported for other extracts encapsulated in zein [20]. In contrast, NpZOBP2 showed no statistically significant changes in the surface charge or hydrodynamic diameter. However, NpZOBP3 exhibited a substantial increase in the hydrodynamic diameter, reaching approximately 500 nm, accompanied by a decrease in the surface charge (Table 2).

Hydrodynamic diameter (nm) and zeta potential (mV) values of zein Np-loaded OBPE

| NpZOBP1 | NpZOBP2 | NpZOBP3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrodynamic diameter (nm) | 166.13 ± 4.88a | 168.63 ± 2.78b | 502.5 ± 15.36c |

| ζ-potential (mV) | 24.8 ± 2.22a | 24.3 ± 1.25a | 20.70 ± 0.96b |

| PDI | 0.115 | 0.064 | 0.080 |

a,b,cDifferent literals per row indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05).

Based on these findings, it can be concluded that NpZOBP2 is the ideal sample for encapsulating OBPE, as it contains the highest concentration of OBPE and exhibits a suitable size for passive internalization in human cells. The absence of significant changes in the surface charge and hydrodynamic diameter further supports the stability and integrity of the Np in this sample.

The results highlight the impact of OBPE concentration on the size and surface charge of the NpZ. The increase in particle size observed in NpZOBP1 and NpZOBP3 can be attributed to the interaction between OBPE and the zein matrix, whereas the absence of significant changes in NpZOBP2 suggests a stable formulation suitable for drug delivery applications.

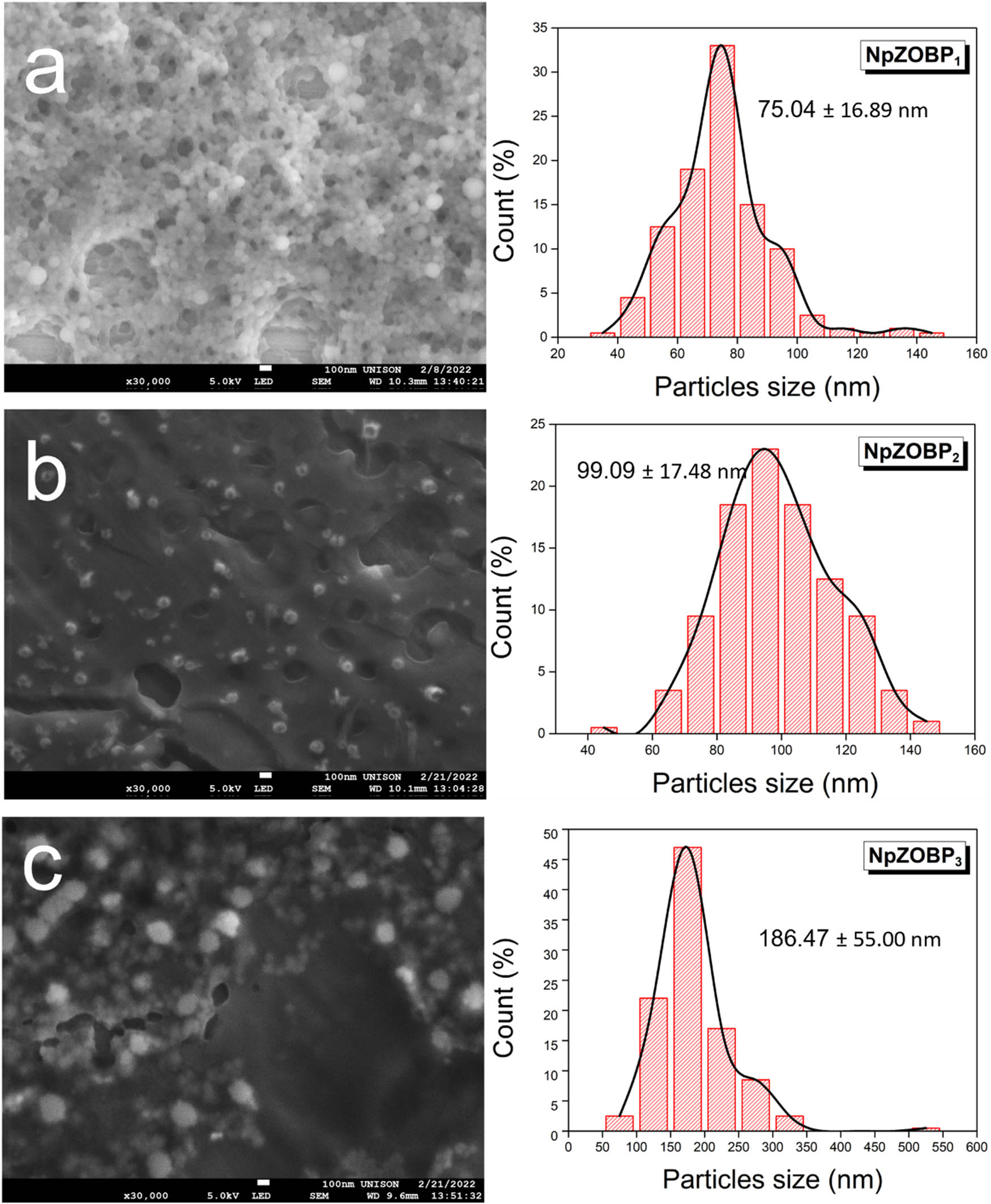

3.4 Morphological and size analysis

The SEM micrographs shown in Figure 7 confirm the size trend observed in the hydrodynamic diameter results. An increase in size is observed as the zein concentration increases. The SEM micrographs provide visual evidence of predominantly spherical morphology, which is consistent with reports from various authors using the synthesis method employed [20,37,38]. This spherical morphology, which is well-suited for cellular internalization, further supports the potential of the Nps for biomedical applications [39].

SEM micrographs and size distributions of the samples: (a) NpZ1, (b) NpZ2, and (c) NpZ3. The size distributions were determined based on measurements of 200 particles, and each size bar corresponds to 100 nm.

In Figure 8, NpZOBP1 exhibits a spherical morphology and a size very similar to NpZ3 (Figure 7). No significant changes in morphology or size are observed. However, NpZOBP2 shows an increase in size, which corresponds to an increase in the hydrodynamic diameter, indicating successful encapsulation of OBPE within the polymer matrix. In NpZOBP3, a doubling of size compared to NpZOBP2 is observed, suggesting that the amount of OBPE present in the sample has saturated the polymer matrix. NpZOBP2 displays a quasi-spherical morphology, and although the zein concentrations in NpZOBP1 and NpZOBP2 are the same, NpZOBP2 exhibits a more dispersed population with less tendency to agglomerate. This behavior can be attributed to the stabilizing effect of OBPE.

SEM micrographs and size distributions of the samples: (a) NpZOBP1, (b) NpZOBP2, and (c) NpZOBP3. The size distributions were determined based on measurements of 200 particles, and each size bar corresponds to 100 nm.

The observed reduction in agglomeration in NpZOBP2 is consistent with findings from studies that report similar effects when encapsulating natural extracts in polymer matrices. For example, in the encapsulation of OE in zein Nps, a reduction in particle coalescence was observed, leading to less agglomeration and greater stability. Furthermore, the addition of OE resulted in improved size control, as evidenced by the decrease in the polydispersity index (PDI) and narrower size distribution compared to unencapsulated Nps, which aligns with our findings for NpZOBP2 [20]. In this case, the natural extract appears to play a key role in stabilizing the Nps and preventing excessive agglomeration. Additionally, the increase in particle size observed in NpZOBP3 has been similarly reported in the encapsulation of bioactive compounds. For instance, upon encapsulation of nobiletin into chitosan Nps, SEM analysis revealed a significant increase in Np size due to the inclusion of the extract, which was corroborated by DLS measurements. This trend, also observed in our samples, highlights the impact of the natural extract on the polymer matrix, particularly in NpZOBP3, where the size increase suggests saturation within the matrix [40].

Despite its hydrodynamic diameter of around 500 nm, NpZOBP3 exhibits low polydispersity, which is supported by the SEM micrograph (Figure 8). This finding opens potential biomedical applications that do not rely on cellular internalization, such as bactericidal and antioxidant functions. The well-defined particle size distribution and the spherical morphology of NpZOBP3 indicate its potential for various non-internalization-based therapeutic and functional applications in the biomedical field. Considering these findings, alongside the observed stability and reduced agglomeration, NpZOBP2 emerges as the most suitable candidate for further applications due to its optimal size, morphology, and stability.

3.5 Quantification of total phenols and flavonoids

The quantification of total phenol and flavonoid content provided valuable insights into the encapsulation process and the bioactivity of the extracted compounds. The OBPE sample exhibited an exceptionally high total phenol and flavonoid content, serving as compelling evidence that the bioactivity of the plant, including its antioxidant potential, remains intact in the extracted compound. The results of the quantification of total phenols and flavonoids are superior to those obtained by aqueous extraction methods, as reported by Grid et al. [41] in 2015. These superior results can be attributed to the use of an ultrasonic bath, which facilitated the extraction of bioactive compounds [8]. Furthermore, the method reported in this study does not require the use of toxic chemicals such as hydrochloric acid. These results are also superior to those found in varieties of the Ocimum basilicum family, as understood by the differences in the extraction method [42]. These results provide evidence of the efficiency of the extraction method, as the extract preserves the integrity of the sought-after bioactive compounds. The antioxidant activity of the NpZ has been previously reported [20]. The fact that the polymeric matrix exhibits antioxidant activity is highly beneficial for the ultimate goal, as it creates synergy with the encapsulated extract in its matrix.

This observation indicates that the encapsulation process effectively preserved a significant amount of bioactive compounds within the NpZ. The notable levels of total phenols and flavonoids in NpZOBP2 demonstrate the successful encapsulation of the extract, highlighting the retention of its bioactivity and antioxidant potential within the zein matrix. The markedly higher total phenol content in NpZOBP2 compared to NPZ3 emphasizes the critical role of encapsulation in concentrating and preserving the bioactivity of the extract. The presence of the encapsulated extract in NpZOBP2 is responsible for its elevated total phenol content, providing evidence of a successful extraction and encapsulation process. This finding further supports the idea that NpZ effectively encapsulates and protects bioactive compounds, thereby preserving their antioxidant activity (Table 3).

Concentrations of flavonoids and total phenols determined in OBPE, NpZ, and NpZ with OBPE (NpZOBP2) samples

| Total phenols (μmol eq AG/g d.w.) | Flavonoids (μmol eq QC/g d.w.) | |

|---|---|---|

| OBPE | 1,807.28 ± 57.38a | 33.17 ± 3.50a |

| NPZ3 | 39.30 ± 2.972b | 1.97 ± 1.55b |

| NpZOBP2 | 51.15 ± 0.290c | 15.21 ± 1.61c |

a,b,cDifferent literals per row indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05).

3.6 Antioxidant capacity, DPPH, and ABTS assays

The DPPH radical evaluation is widely utilized to assess the antioxidant activity of natural compounds by measuring the reduction of DPPH radicals in the presence of hydrogen-donating antioxidants [43]. Figure 9 illustrates the DPPH radical scavenging activity of OBPE, NpZ3, and NpZOBP2 treatments, with Trolox serving as a reference standard. Significant differences in DPPH radical scavenging activity were observed between OBPE and NpZ3 (p < 0.05). In contrast, no significant difference was noted between OBPE and NpZOBP2 (p > 0.05). OBPE exhibited strong antioxidant activity of 40 ± 5% at a concentration of 300 µg·mL−1, consistent with previous studies highlighting the high phenolic content and potent radical scavenging properties of extracts from the Ocimum basilicum family [44]. Conversely, NpZ demonstrated a considerably lower scavenging effect of 18 ± 5% at 4,370 µg·mL−1, which aligns with reports, indicating that zein lacks intrinsic antioxidant activity due to its protein structure [45].

Scavenging ability of Trolox, OBPE (300 mg·mL−1), NpZ3 (4,370 mg·mL−1), and NpZOBP2 (4,670 mg·mL−1) on DPPH radicals. Each value is expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 4). Mean values with different letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

NpZOBP2 exhibited ABTS scavenging activity of 39% at a concentration of 4,670 µg·mL−1, which is lower than that of OBPE but shows enhanced activity compared to NpZ3 (p < 0.05). The encapsulation of OBP within NpZ may protect the bioactive compounds, facilitating more controlled release; however, the interaction with the zein matrix could limit immediate scavenging efficiency [46]. These results suggest that while encapsulation enhances stability, it may reduce the immediate radical scavenging capacity.

Interestingly, NpZOBP2 demonstrated scavenging activity, indicating that the potential antioxidant capacity of NpZ3 is statistically lower than that of NpZOBP2 (Figure 10). This finding supports the hypothesis that the extract maintains its antioxidant potential when associated with zein in Np form. The increase in scavenging activity can be attributed to the protection and controlled release of phenolic compounds from the extract during the scavenging process, as previously observed in similar encapsulation systems [47]. Although the activity of NpZOBP2 was slightly higher than that of OBPE, these results bolster the concept that Np encapsulation can preserve and even enhance the bioactivity of plant extracts under certain conditions.

Scavenging ability of Trolox, OBPE (300 mg·mL−1), NpZ3 (4,370 mg·mL−1), and NpZOBP2 (4,670 mg·mL−1) on ABTS radicals. Each value is expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 4). Mean values with different letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

Additionally, Table 4 presents the antioxidant activities of OBPE, NpZ3, and NpZOBP2 in terms of Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC), expressed in micromoles of Trolox equivalent per gram of dry sample (µmol TE/g d.w.). Table 4 summarizes the antioxidant capacity results for OBPE, NpZ3, and NpZOBP2 across various methods. For the ABTS assay, the values obtained were 591 µmol TE/g for OBPE, 61.11 µmol TE/g for NpZ3, and 69 µmol TE/g for NpZOBP2, respectively. It is important to highlight that higher TEAC values indicate greater antioxidant capacity, reflecting an enhanced ability to scavenge free radicals. OBPE exhibited a significantly high antioxidant capacity (591 µmol TE/g), consistent with prior research that emphasizes the strong antioxidant potential of plants rich in phenolic compounds. OBPE has been extensively studied for its abundance of compounds, such as rosmarinic acid, eugenol, and flavonoids, which serve as potent antioxidant agents. Comparative studies have reported similar antioxidant capacities in extracts from other aromatic herbs, such as oregano (Origanum vulgare) and thyme (Thymus vulgaris), with values ranging from 115 to 192.4 µmol TE/g, as determined by the ABTS method [48,49]. In contrast, NpZ3 exhibited a significantly lower antioxidant capacity (61.11 µmol TE/g). As a protein derived from maize, zein’s antioxidant profile is limited due to the lack of bioactive compounds capable of effectively neutralizing free radicals. NpZOBP2 showed a slight increase in antioxidant capacity (69 µmol TE/g) compared to the empty Nps, although this value remains lower than that of the free extract.

Antioxidant activity of OBPE extract, NpZ3 NpZ, and NpZOBP2

| Treatment | ABTS (μmol TE/g) | DPPH (μmol TE/g) | FRAP (μmol TE/g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| OBPE | 591.96 ± 23.10a | 2,879.90 ± 121.82a | 785.28 ± 19.40a |

| NPZ3 | 61.11 ± 3.36b | 136.55 ± 3.20b | 47.49 ± 0.93b |

| NpZOBP2 | 69.48 ± 0.63c | 172.90 ± 1.03c | 55.26 ± 2.91c |

Note: the data are represented as mean values ± standard deviation (n = 4). Different letters within the same row indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

The DPPH results indicated that OBPE presented an antioxidant capacity of 2,879.90 µmol TE/g, which was significantly higher than NpZ3 (136.55 µmol TE/g) and NpOBP2 (172.90 µmol TE/g). This result is consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated that plant extracts are rich in phenolic compounds and flavonoids, such as OBPE, possesses high radical-scavenging capacities due to the presence of these bioactive compounds [50].

A low TEAC value of 136.55 µmol TE/g was also observed for NpZ3, and these results align with previous research reporting relatively low antioxidant capacities for NpZ. However, the Np formulation process can improve the stability of bioactive compounds, as reported in studies where NpZ were combined with other antioxidants [51]. The NpOBP2 exhibited an improved antioxidant capacity (172.90 µmol TE/g), although it remained significantly lower than the free extract. This result can be attributed to the partial encapsulation of the OBPE in the zein matrix, which limits the immediate availability of the phenolic compounds responsible for antioxidant activity. Previous studies with similar systems have demonstrated that while encapsulation may reduce initial antioxidant activity, it provides a controlled release of the bioactive compounds, potentially enhancing their long-term effectiveness [52].

The antioxidant capacity of the different systems was also evaluated in this study using the FRAP technique, which measures the ability of a compound or extracts to reduce ferric ion (Fe³⁺) to its ferrous form (Fe²⁺), providing a measure of its antioxidant power. The results obtained showed significant differences between OBPE, NpZ3, and NpOBP2. OBPE displayed the highest antioxidant capacity with a value of 785.28 µmol TE/g, which aligns with reports for other extracts rich in phenolic compounds. These compounds, such as flavonoids and phenolic acids, are known for their high reducing capacity, explaining the observed results. In contrast, NpZ3 exhibited a considerably lower antioxidant capacity, 47.49 µmol TE/g. The low reducing capacity of zein is due to its protein structure, which lacks functional groups directly associated with free radical neutralization or reducing power [45].

In the case of NpOBP2, the antioxidant capacity slightly increased to 55.26 µmol TE/g. While this improvement is modest compared to the free extract, it indicates that part of the extract was successfully encapsulated in the zein matrix and that some of the bioactive compounds are still capable of exerting antioxidant activity. However, this value remains low compared to the free extract, which can be explained by the partial encapsulation and the potential retention of antioxidant compounds within the Nps, limiting their direct interaction with the medium in which the FRAP assay is conducted [53].

The DPPH results indicated that OBPE exhibited an antioxidant capacity of 2,879.90 µmol TE/g, significantly higher than that of NpZ3 (136.55 µmol TE/g) and NpOBP2 (172.90 µmol TE/g). This finding is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that plant extracts rich in phenolic compounds and flavonoids, such as those from OBP, possess high radical-scavenging capacities due to the presence of these bioactive compounds [50].

A low TEAC value of 136.55 µmol TE/g was also observed for NpZ3, aligning with previous research that reported relatively low antioxidant capacities for NpZ. However, the Np formulation process can enhance the stability of bioactive compounds, as documented in studies where NpZ were combined with other antioxidants [51]. NpOBP2 exhibited an improved antioxidant capacity (172.90 µmol TE/g), although it remained significantly lower than that of the free extract. This outcome can be attributed to the partial encapsulation of OBPE within the zein matrix, which limits the immediate availability of the phenolic compounds responsible for antioxidant activity. Previous studies with similar systems have demonstrated that while encapsulation may reduce initial antioxidant activity, it allows for the controlled release of bioactive compounds, potentially enhancing their long-term effectiveness [52].

The antioxidant capacity of the different systems was further evaluated using the FRAP technique, which measures the ability of a compound or extracts to reduce ferric ion (Fe³⁺) to its ferrous form (Fe²⁺), providing a measure of its antioxidant power. The results showed significant differences among OBPE, NpZ3, and NpOBP2. OBPE displayed the highest antioxidant capacity with a value of 785.28 µmol TE/g, consistent with reports for other extracts rich in phenolic compounds. These compounds, such as flavonoids and phenolic acids, are known for their high reducing capacity, which explains the observed results. In contrast, NpZ3 exhibited considerably lower antioxidant capacity at 47.49 µmol TE/g. This low reducing capacity of zein is attributed to its protein structure, which lacks functional groups directly associated with free radical neutralization or reducing power [45].

In the case of NpOBP2, the antioxidant capacity slightly increased to 55.26 µmol TE/g. Although this improvement is modest compared to the free extract, it indicates that part of the extract was successfully encapsulated within the zein matrix, allowing some bioactive compounds to retain antioxidant activity. However, this value remains low in comparison to the free extract, likely due to the partial encapsulation and the potential retention of antioxidant compounds within the Nps, which limits their direct interaction with the medium during the FRAP assay [53].

4 Conclusions

This study underscores the significant potential of NpZ as a controlled release system for bioactive extracts, particularly OBPE. The effective encapsulation of OBPE within NpZ not only preserves its antioxidant activity but also facilitates the sustained release of bioactive compounds. Through comprehensive physicochemical characterizations, including FTIR, DLS, zeta potential analysis, SEM, and UV-visible spectroscopy, the successful encapsulation and retention of bioactivity within the NpZ samples were thoroughly confirmed.

The Nps exhibited desirable properties such as optimal surface charge, suitable size, and favorable morphology, which enhanced their capability for cellular internalization. The quantification of total phenols and flavonoids further validates the effectiveness of the extraction method, revealing a high antioxidant capacity consistent with the presence of these compounds. Phenolic compounds are known to mitigate oxidative stress by reducing or inhibiting free radicals through the transfer of hydrogen atoms from their hydroxyl groups.

Notably, NpZ loaded with extracts demonstrated a significantly higher reducing capacity compared to NpZ alone, which exhibited considerably lower antioxidant activity. However, the antioxidant capacity of the encapsulated extracts remained lower than that of the free extract. This discrepancy may be due to the interaction of the reaction medium with phenolic compounds, potentially forming hydrogen bonds that limit their reactivity. Such limitations could stem from the partial encapsulation and retention of antioxidant compounds within the Nps, restricting their direct interaction with the medium during free radical assays. The findings suggest that different mechanisms may govern the antioxidant activity of NpZOBP, including hydrogen atom donation (DPPH), electron donation (ABTS), and the reduction of Fe³⁺ to Fe²⁺, thereby providing protection against oxidative damage and stabilizing free radicals. This reinforces the success of the extraction process and highlights the potential of NpZ as an effective carrier for bioactive compounds.

The implications of this research extend beyond basic findings; it demonstrates the efficacy of both the extraction and encapsulation processes and the suitability of NpZ as a delivery vehicle for bioactive compounds. The study’s results indicate that NpZ could be effectively utilized in pharmaceutical and food applications to enhance the stability and bioactivity of antioxidant compounds, thereby combating oxidative stress and its associated detrimental effects. Looking forward, future research should focus on investigating the therapeutic efficacy and targeted delivery capabilities of OBPE-loaded NpZ in relevant biological models. Such studies could pave the way for innovative applications in health and nutrition, potentially leading to new strategies for mitigating oxidative stress-related conditions.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Nanotechnology postgraduate program at Universidad de Sonora, particularly Dr. Roberto Carlos Carrillo Torres, for their assistance in the physicochemical characterization.

-

Funding information: This research was funded by an internal project of Universidad Estatal de Sonora with code UES-PII-23-UAH-IB-01.

-

Author contributions: Hernández-Abril Pedro Amado: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing-original draft preparation and project administration, writing – review and editing; Higuera Valenzuela Hiram Jesús: Formal analysis and original draft preparation; Cota-Arriola Octavio: Methodology and investigation; Moreno-Vásquez María Jesús: Formal analysis; Ramírez-Guerra Hugo Enrique: Formal analysis; Luque-Alcaraz Ana Guadalupe: Methodology, investigation, writing – original draft preparation and writing – review and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Srinivas US, Tan BWQ, Vellayappan BA, Jeyasekharan AD. ROS and the DNA damage response in cancer. Redox Biol. 2019;25:101084. 10.1016/j.redox.2018.101084.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Rizwana N, Agarwal V, Nune M. Antioxidant for neurological diseases and neurotrauma and bioengineering approaches. Antioxidants. 2021;11:72. 10.3390/antiox11010072.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Pirtarighat S, Ghannadnia M, Baghshahi S. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ocimum basilicum cultured under controlled conditions for bactericidal application. Mater Sci Eng C. 2019;98:250–5. 10.1016/j.msec.2018.12.090.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Nadia Salleh N, Yahya H, Ariffin N, Nadia Yahya H. Antibacterial properties of Ocimum Spp. (Ocimum basilicum L. and Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens) against selected bacteria. East Afr Scholars J Agric Life Sci. 2021;4:194–200. 10.36349/easjals.2021.v04i10.001.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Abdul Salam H, Sivaraj R, Venckatesh R. Green synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles from Ocimum basilicum L. var. purpurascens Benth.-Lamiaceae leaf extract. Mater Lett. 2014;131:16–8. 10.1016/j.matlet.2014.05.033.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Fernandes F, Pereira E, Círić A, Soković M, Calhelha RC, Barros L, et al. Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens leaves (red rubin basil): A source of bioactive compounds and natural pigments for the food industry. Food Funct. 2019;10:3161–71. 10.1039/c9fo00578a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Syama Sundar B, Sreekanth Kumar J, Ramana M. Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Ocimum basilicum L. var.thyrsiflorum. Eur J Acad Essays. 2014;1:5–9.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Gîrd CE, Costea T, Nencu I, Duţu LE, Popescu ML, Balaci TD. Comparative pharmacognostic analysis of romanian Ocimum basilicum l. and O. basilicum var. purpurascens benth. aerial parts. Farmacia. 2015;63:840–4.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Jalali-Jivan M, Garavand F, Jafari SM. Microemulsions as nano-reactors for the solubilization, separation, purification and encapsulation of bioactive compounds. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2020;283:102227. 10.1016/j.cis.2020.102227.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Rehman A, Ahmad T, Aadil RM, Spotti MJ, Bakry AM, Khan IM, et al. Pectin polymers as wall materials for the nano-encapsulation of bioactive compounds. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2019;90:35–46. 10.1016/j.tifs.2019.05.015.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Deshpande BD, Agrawal PS, Yenkie MKN, Dhoble SJ. Prospective of nanotechnology in degradation of waste water: A new challenges. Nano-Struct Nano-Objects. 2020;22:100442. 10.1016/j.nanoso.2020.100442.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Hernández-Abril PA, Iriqui-Razcón JL, León-Sarabia E, Leal-Soto SD, Álvarez-Ramos ME, Berman-Mendoza D, et al. Synthesis of silicon quantum dots using chitosan as a novel reductor agent. Rev Mexicana de Fis. 2021;67:249–54. 10.31349/RevMexFis.67.249.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Hernández-Téllez CN, Luque-Alcaraz AG, Plascencia-Jatomea M, Higuera-Valenzuela HJ, Burgos-Hernández M, García-Flores N, et al. Synthesis and characterization of a Fe3O4@PNIPAM-Chitosan nanocomposite and its potential application in vincristine delivery. Polymers (Basel). 2021;13:1704. 10.3390/polym13111704.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Luo S, Ma C, Zhu MQ, Ju WN, Yang Y, Wang X. Application of iron oxide nanoparticles in the diagnosis and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases with emphasis on Alzheimer’s disease. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020;14:21. 10.3389/fncel.2020.00021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Ge Y, Kang B. Surface plasmon resonance scattering and absorption of biofunctionalized gold nanoparticles for targeted cancer imaging and laser therapy. Sci China Technol Sci. 2011;54:2358–62. 10.1007/s11431-011-4493-y.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Hernández P, Lucero-Acuña A, Moreno-Cortez IE, Esquivel R, Álvarez-Ramos E. Thermo-magnetic properties of Fe3O4 @Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide) core–shell nanoparticles and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa and MDA-MB-231 cell lines. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2020;20:2063–71. 10.1166/jnn.2020.17324.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Esquivel R, Canale I, Ramirez M, Hernández P, Zavala-Rivera P, Álvarez-Ramos E, et al. Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-coated gold nanorods mediated by thiolated chitosan layer: Thermo-pH responsiveness and optical properties. E-Polymers. 2018;18:163–74. 10.1515/epoly-2017-0135.Search in Google Scholar

[18] de Melo APZ, da Rosa CG, Sganzerla WG, Nunes MR, Noronha CM, Brisola Maciel MVO, et al. Syntesis and characterization of zein nanoparticles loaded with essential oil of Ocimum gratissimum and Pimenta racemosa. Mater Res Express. 2019;6:95084. 10.1088/2053-1591/ab2fc1.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Chuacharoen T, Sabliov CM. Stability and controlled release of lutein loaded in zein nanoparticles with and without lecithin and pluronic F127 surfactants. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2016;503:11–8. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2016.04.038.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Luque-Alcaraz AG, Velazquez-Antillón M, Hernández-Téllez CN, Graciano-Verdugo AZ, García-Flores N, Iriqui-Razcón JL, et al. Antioxidant effect of nanoparticles composed of zein and orange (Citrus sinensis) extract obtained by ultrasound-assisted extraction. Materials. 2022;15:4838. 10.3390/ma15144838.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Mahendra C, Chandra MN, Murali M, Abhilash MR, Singh SB, Satish S, et al. Phyto-fabricated ZnO nanoparticles from Canthium dicoccum (L.) for antimicrobial, anti-tuberculosis and antioxidant activity. Process Biochem. 2020;89:220–6. 10.1016/j.procbio.2019.10.020.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Islam MZ, Park BJ, Kang HM, Lee YT. Influence of selenium biofortification on the bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of wheat microgreen extract. Food Chem. 2020;309:125763. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125763.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Soltanzadeh M, Peighambardoust SH, Ghanbarzadeh B, Mohammadi M, Lorenzo JM. Chitosan nanoparticles as a promising nanomaterial for encapsulation of pomegranate (Punica granatum l.) peel extract as a natural source of antioxidants. Nanomaterials. 2021;11:1439. 10.3390/nano11061439.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Vilchez A, Acevedo F, Cea M, Seeger M, Navia R. Applications of electrospun nanofibers with antioxidant properties: A review. Nanomaterials. 2020;10:175. 10.3390/nano10010175.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Li M, Yu M. Development of a nanoparticle delivery system based on zein/polysaccharide complexes. J Food Sci. 2020;85:4108–17. 10.1111/1750-3841.15535.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Abdelsalam AM, Somaida A, Ayoub AM, Alsharif FM, Preis E, Wojcik M, et al. Surface-tailored zein nanoparticles: Strategies and applications. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:1354. 10.3390/pharmaceutics13091354.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Moreno-Vásquez MJ, Plascencia-Jatomea M, Sánchez-Valdes S, Tanori-Córdova JC, Castillo-Yañez FJ, Quintero-Reyes IE, et al. Characterization of epigallocatechin-gallate-grafted chitosan nanoparticles and evaluation of their antibacterial and antioxidant potential. Polymers. 2021;13:1375. 10.3390/polym13091375.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Benzie IFF, Strain JJ. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of ‘antioxidant power’: The FRAP assay. Anal Biochem. Jul. 1996;239:70–6. 10.1006/abio.1996.0292.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Hu B, Wang Y, Xie M, Hu G, Ma F, Zeng X. Polymer nanoparticles composed with gallic acid grafted chitosan and bioactive peptides combined antioxidant, anticancer activities and improved delivery property for labile polyphenols. J Funct Foods. 2015;15:593–603. 10.1016%2Fj.jff.2015.04.009.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Lee J, Scagel CF. Chicoric acid found in basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) leaves. Food Chem. 2009;115:650–6. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.12.075.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Avula B, Wang Y, Smillie T, Fu X, Li X, Mabusela W, et al. Quantitative determination of flavonoids and triterpenoids in sutherlandia frutescens by LC-UV, LC-ELSD methods and confirmation by LC-ESI-MSD-TOF. Planta Med. 2008;74:173–80. 10.1055/s-2008-1075338.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Chen HJ, Inbaraj BS, Chen BH. Determination of phenolic acids and flavonoids in Taraxacum formosanum kitam by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry coupled with a post-column derivatization technique. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:260–85. 10.3390/ijms13010260.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Oliveira RN, Mancini MC, Oliveira F, Passos TM, Quilty B, Thiré R, et al. FTIR analysis and quantification of phenols and flavonoids of five commercially available plants extracts used in wound healing. Matéria. 2016;21:767–79. 10.1590/S1517-707620160003.0072.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Chen C, Mokhtar RAM, Sani MSA, Noor NQIM. The effect of maturity and extraction solvents on bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of mulberry (Morus alba) fruits and leaves. Molecules. 2022;27:2406. 10.3390/molecules27082406.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Mohanad JK, Azhar AS, Imad HH. Evaluation of anti-bacterial activity and bioactive chemical analysis of Ocimum basilicum using Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) techniques. JPP. 2016;8:127–46. 10.5897/JPP2015.0366.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Sakuntala P, Raju RS, Jaleeli KA. FTIR and energy dispersive X-ray analysis of medicinal plants, Ocimum gratissimum and Ocimum tenuiflorum. J Sci Res Phys Appl Sci. 2019;7:6–10. 10.26438/ijsrpas/v7i3.610.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Podaralla S, Perumal O. Influence of formulation factors on the preparation of zein nanoparticles. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2012;13:919–27. 10.1208/s12249-012-9816-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Luo Y, Zhang B, Whent M, Yu LL, Wang Q. Preparation and characterization of zein/chitosan complex for encapsulation of α-tocopherol, and its in vitro controlled release study. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2011;85:145–52. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.02.020.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Truong NP, Whittaker MR, Mak CW, Davis TP. The importance of nanoparticle shape in cancer drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2015;12:129–42. 10.1517/17425247.2014.950564.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Hernández-Abril PA, López-Meneses AK, Lizardi-Mendoza J, Plascencia-Jatomea M, Luque-Alcaraz AG. Cellular internalization and toxicity of chitosan nanoparticles loaded with nobiletin in eukaryotic cell models (Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans). Materials. 2024;17:1525. 10.3390/ma17071525.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Gird CE, Nencu I, Costea T, Duţu LE, Popescu ML, Ciupitu N. Quantitative analysis of phenolic compounds from Salvia officinalis L. leaves. Farmacia. 2014;62(4):649–57.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Tahira R, Rehan T, Ata-ur-Rehman, Naeemullah M. Variation in bioactive compounds in different plant parts of Lemon basil (Ocimum basilicum Var Citriodorum). Int J Innov Sci Math. 2013;1:33–6.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Alqahtani NK, Salih ZA, Asiri SA, Siddeeg A, Elssiddiq S, Alnemr TM, et al. Optimizing physicochemical properties, antioxidant potential, and antibacterial activity of dry ginger extract using sonication treatment. Heliyon. 2024;10:e36473. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e36473.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Ahmed AF, Attia FAK, Liu Z, Li C, Wei J, Kang W. Antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of essential oils and extracts of sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) plants. Food Sci Hum Wellness. 2019;8:299–305. 10.1016/j.fshw.2019.07.004.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Xu Y, Wei Z, Xue C, Huang Q. Covalent modification of zein with polyphenols: A feasible strategy to improve antioxidant activity and solubility. J Food Sci. 2022;87:2965–79. 10.1111/1750-3841.16203.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Liu J, Yu H, Kong J, Ge X, Sun Y, Mao M, et al. Preparation, characterization, stability, and controlled release of chitosan-coated zein/shellac nanoparticles for the delivery of quercetin. Food Chem. 2024;444:138634. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.138634.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Chen J, Zhang Z, Li H, Sun M, Tang H. Preparation, structural characterization, and functional attributes of zein-lysozyme-κ-carrageenan ternary nanocomposites for curcumin encapsulation. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;270:132264. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.138634.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Michalaki A, Karantonis HC, Kritikou AS, Thomaidis NS, Dasenaki ME. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of total phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity evaluation from oregano (Origanum vulgare ssp. hirtum) using response surface methodology and identification of specific phenolic compounds with HPLC-PDA and Q-TOF-MS/MS. Molecules. 2023;28:2033. 10.3390/molecules28052033.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Aljabeili HS, Barakat H, Abdel-Rahman HA. Chemical composition, antibacterial and antioxidant activities of thyme essential oil (Thymus vulgaris). Food Nutr Sci. 2018;9(5):433–46. 10.4236/fns.2018.95034.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Malik AR, Sharif S, Shaheen F, Khalid M, Iqbal Y, Faisal A, et al. Green synthesis of RGO-ZnO mediated Ocimum basilicum leaves extract nanocomposite for antioxidant, antibacterial, antidiabetic and photocatalytic activity. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2022;26:101438. 10.1016/j.jscs.2022.101438.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Huang Y, Zhan Y, Luo G, Zeng Y, McClements DJ, Hu K. Curcumin encapsulated zein/caseinate-alginate nanoparticles: Release and antioxidant activity under in vitro simulated gastrointestinal digestion. Curr Res Food Sci. 2023;6:100463. 10.1016/j.crfs.2023.100463.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Proença PLF, Campos EVR, Costa TG, de Lima R, Preisler AC, de Oliveira HC, et al. Curcumin and carvacrol co-loaded zein nanoparticles: Comprehensive preparation and assessment of biological activities in pest control. Plant Nano Biol. 2024;8:100067. 10.1016/j.plana.2024.100067.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Zulham, Wardhana YW, Subarnas A, Susilawati Y, Chaerunisaa AY. Microencapsulation of Schleichera oleosa L. leaf extract in maintaining their biological activity: Antioxidant and hepatoprotective. Int J Appl Pharm 2023;15:326–33. 10.22159/ijap.2023v15i6.48960.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings