Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

Abstract

The potential for waste management can be enhanced by the recovery and utilisation of waste biomass. In this work, we used analytical n-hexane to chemically extract sandbox oil, and we followed it up with a single transesterification step to turn it into biodiesel. Diesel and biodiesel were mixed to make five fuel samples (diesel, B20, B40, B50, and B100). These fuel samples were then burned in a compression ignition engine test bed to assess their performance and ascertain their emission characteristics. The test fuels yielded 5.2 kW of rated power from an unmodified single-cylinder diesel engine. It has been found that combustion–ignition engines can effectively use sandbox biodiesel as a biofuel. Pollution is also decreased by burning biofuels. As to the test findings, B20 (20% biodiesel and 80% diesel) outperformed other automobiles with respect to high cylinder pressure and heat release rate, reducing hydrocarbon, carbon monoxide, and smoke emissions by 12.5%, 35.5%, and 38.5%, respectively. The results so far are similar to diesel.

Nomenclature

- ASTM

-

American Society for Test and Material

- BSFC

-

brake-specific fuel consumption

- BTE

-

brake thermal efficiency

- CA

-

crank angle

- CO

-

carbon monoxide

- CO2

-

carbon dioxide

- EGT

-

exhaust gas temperature

- HC

-

hydrocarbon

- HRR

-

heat release rate

- MAO

-

microalgae oil

- MAME

-

microalgae methyl ester

- NO x

-

nitrogen oxides

- PM

-

particulate matter

- SO2

-

sulphur dioxide

- SO x

-

sulphur oxides

1 Introduction

The increasing global focus on environmental sustainability has spurred significant interest in alternative fuels for internal combustion engines. Diesel engines, renowned for their efficiency and power, are traditionally fuelled by petroleum-based diesel, which contributes to greenhouse gas emissions and other environmental pollutants. As a result, there is a growing need to explore and develop alternative fuels that are both environmentally friendly and capable of delivering performance comparable to or exceeding that of conventional diesel fuels. Among various alternative fuels, biofuels derived from vegetable oils are particularly promising. They offer the potential for reduced carbon emissions and can be produced from renewable resources. Sandbox seed oil, a lesser-known but potentially viable biofuel, is derived from the seeds of plants adapted to specific environmental conditions. The use of such seed oils can offer a sustainable and eco-friendly alternative to traditional diesel fuels. Petroleum fuel remains one of the world’s primary energy sources. However, worries about the global depletion and likely extinction of petroleum fuels as well as the pollution from their combustion exhaust that is degrading the environment are facilitating research into alternative energy sources to either supplement or replace petroleum fuels entirely [1]. As a fuel substitute and a biomass resource, the methyl or ethyl ester that comes from this process is referred to as “biodiesel.” Since biodiesels are oxygenated, sulphur-free, and biodegradable, they are acknowledged as non-toxic and environmentally beneficial [2]. It is vital to investigate and create new sources of non-edible vegetable oils in order to bridge the gap caused by the pressure on alternate uses of vegetable oils. One of these feedstocks is sandbox seed oil [3]. The neglected sandbox plant is grown as a shade tree in towns and cities. They require alternative bioenergy sources because they can only operate efficiently on liquid fuels with high-energy densities [4]. In addition to supporting the Paris Climate Change Agreement, bioenergy may be a significant and advantageous means of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, which include ensuring food security, improving land use, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Because diesel engines run on diesel produce emissions such as sulphur oxides (SO x ), nitrogen oxides (NO x ), soot, particulate matter (PM), and unburned hydrocarbon, using biodiesel is essential. Reportedly, blended biodiesel in diesel engines may be a more efficient way to meet the global decarbonisation goal for the transportation sector than pure biodiesel [5]. To ensure that only premium biodiesel is sold on the market, most countries have developed biodiesel standards [6]. In the United States and the European Union, the two most significant fuel standards are American Society for Test and Material (ASTM) D6751 and EN 14214 [7]. The amount and quality of methyl esters produced from vegetable oils are greatly influenced by the type of catalyst used, whether it is an acid or a base, its concentration, the molar ratio of alcohol to vegetable oil, the reaction temperature, the amount of free fatty acids in the vegetable oil, and the purity level of the reactant, especially the water content. Biodiesel fuel has several advantages over diesel fuel, including lower vapour pressure, a higher flash point, improved lubricity, reduced toxicity, and less exhaust pollutants. Previous reviews of the literature have shown no evidence that biodiesel derived from sandbox seed oil can take the place of diesel fuel in diesel engine applications. Harigaran et al. investigated diesel engine characteristic using microalgae oil (MAO) of chlorella protothecoides and microalgae methyl ester (MAME). The experimental outcome showed lowered brake thermal efficiency (BTE) and in-cylinder pressure by 5.6% and 3.09% than diesel. Marginal reductions in hydrocarbon (HC), carbon monoxide (CO), smoke, and NO x emissions are observed. Higher peak pressure of 64.4 bar was noted for diesel followed by 61.32 bar for MAME and 58.52 bar for MAO [8]. The emissions from cars are the main source of air pollution worldwide. Even with major reductions in exhaust emissions due to engine research and development and an increase in the number of automobiles, the issue will still exist in the future. The primary pollutants produced by engines are HC, CO, NO x , and PM. Compared to conventional diesel fuel, biodiesel produces less exhaust pollutants, has a higher flash point, low vapour pressure, and is more biodegradable, less toxic, and more lubricating. Previous assessments of the literature have indicated that biodiesel made from sandbox seed oil is not able to replace diesel fuel in applications requiring diesel engines [8]. The increasing demand for sustainable energy sources has highlighted the need for alternatives to fossil fuels. Biodiesel, a renewable energy source derived from biological materials such as vegetable oils and animal fats, has emerged as a promising substitute for conventional diesel. However, the widespread adoption of biodiesel faces several challenges. These include concerns about its production efficiency, impact on food supply, and overall environmental benefits compared to traditional fuels. Additionally, issues related to the technical performance of biodiesel in various engine types and its economic viability in relation to fossil fuels need to be thoroughly addressed. This problem statement outlines the need for a comprehensive evaluation of biodiesel’s production processes, environmental impact, and economic feasibility to support its broader implementation and integration into the energy market. In this work, sandbox seeds are extracted by salt extraction and transesterification to produce bio-oil and biodiesel. Diesel was diluted with the produced sandbox seed oil in the following ratios: B20, B40, B50, and neat B100. The characteristics of mixed fuel were evaluated using ASTM standards. So, utilising all of the test fuels, the combustion, performance, and emission properties of an unaltered diesel engine were examined. The experimental findings are compared to diesel fuel used at maximum outputs. In the present work, a direct ignition engine running on mixes of sandbox seed oils was investigated for performance, emissions, and combustion characteristics.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Preparation of the sample and oil extraction

In the Nigerian metropolis of Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, 150 kg of ripe sandbox fruits were taken out of the ground under the trees between 2020 and 2022. Figures 1 and 2 show the kernel (mesocarp) after the fruits in Figure 3 were cracked to release the seeds.

Sandbox seeds.

Sandbox kernels.

Sandbox fruits.

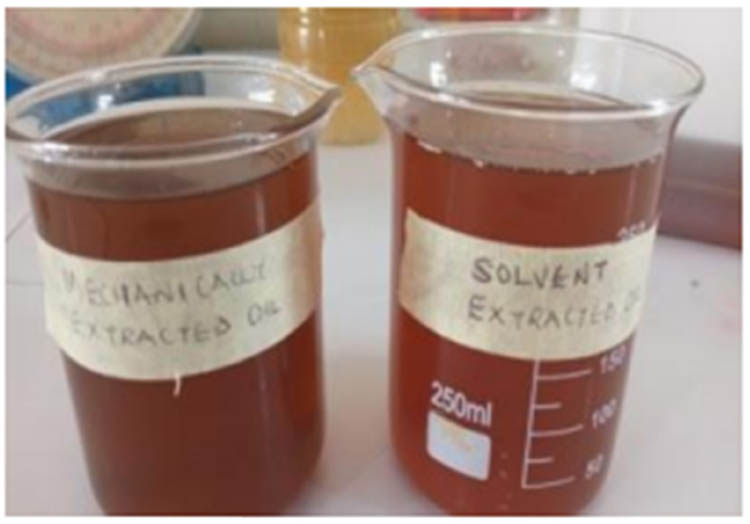

The solvent extraction method described in the AOCS 5-04 standard procedure was used to obtain sandbox oil (Figure 4) from the sandbox seed. Figure 5 shows the transesterification of the oil using methanol as the alcohol and a potassium hydroxide catalyst. At a reaction temperature of 60°C, with an alcohol-to-oil ratio of 1:5, a catalyst concentration of 0.9 g of oil, and a reaction period of 90 min, the transesterification process was carried out. The methyl ester was carefully cleaned after being removed from the glycerol phase. As shown by the letters B5, B10, B15, B20, B25, B50, and B100, the sandbox seed methyl ester (Figure 6) was blended with automotive gas oil at varied ratios of 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, 50%, and 100% diesel.

Sandbox seed oil.

Transesterification.

SBME.

After 13 h, the generated biodiesel was separated from the mixture (glycerol and leftover reactants) using a separating funnel. To eliminate contaminants and reactant residue, the biodiesel was aggressively mixed with heated water at 70°C in the separating funnel. After 24 h, the impurity was removed from the biodiesel, and Eq. 1 was used to calculate the % yield of biodiesel.

The manufactured biodiesel was examined to determine its physical and chemical characteristics using techniques advised by the ASTM. By acquiring data such as the flash point, kinematic viscosity, acid value, cloud point, cetane number, and iodine value, it is crucial to ascertain if the biofuel is suitable for use in diesel engines. Each parameter was measured three times, and the standard deviation was computed appropriately (Table 1).

Fuel characteristics of sandbox seed oil, Syzygium cumini (jamun), and diesel

| S. no | Property | Diesel | Sandbox seed oil | Syzygium cumini (jamun) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Molecular weight (g·mol−1) | 160 | 815.62 | 918.54 |

| 2 | Stoichiometric air–fuel ratio | 33.5 | N/A | N/A |

| 3 | Flame velocity (cm·s−1) | 27 | 30 | 34 |

| 4 | Auto-ignition temperature (K) | 534 | 715 | 700–830 |

| 5 | Heat of combustion (kJ·kg−1) | 40.3 | 74 | 64 |

| 6 | Density of gas at NTP (g·cm−3) | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.74 |

| 7 | Octane number | — | 84 | 55 |

| 8 | Cetane number | 45–55 | 40 | 45 |

| 9 | Boiling point (K) | 550–630 | 370 | 340–405 |

| 10 | Specific gravity | 0.78 | 0.845 | 0.918 |

3 Experimental setup

The schematic layout of engine test bench is shown in Figure 7. In this study, an eddy current dynamometer and a single-cylinder, water-cooled, four-stroke diesel engine from Kirloskar TV1 were combined. This test engine powered a vehicle at a constant speed of 1,500 rpm with varied loads of 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 kW. The engine manufacturer testified that the fuel injection was run at 23°C before TDC with 200 bar of constant pressure. Table 2 includes a complete specification of the test engine. It comprises a combustion chamber with a hemispherical shape, three holes with 0.3 mm-diameter fuel injector nozzles, and mechanical fuel injectors for inline fuel injection. Tests were conducted with electrical eddy current load from 0% to 100% with 25% increment of loading. To find in-cylinder pressure and heat release rate (HRR), MICO fuel injector with transducer is placed over the cylinder head. Exhaust gas analyser QRO-402 type is used to find the amount of HC, CO, and NO x in exhaust gas. Smoke is found using AVL437C smoke meter. The entire experimental setup is shown in Figure 7. SAE100 lubricating oil is used to reduce friction between moving parts inside the engine (Table 3).

Engine experimental setup.

Research engine specifications

| Make | Kirloskar TV – I |

|---|---|

| Rated brake power | 5.2 kW |

| Bore and stroke | 87.5 and 110 mm |

| Injection timing | 23° before TDC |

| Compression ratio | 17.5:1 |

| Injection pressure | 220 bar |

| Speed | 1,500 rpm |

| Injection type | Mechanical injection system |

Uncertainty of various parameters

| Parameters | Uncertainty (%) |

|---|---|

| Load | 0.3 |

| Speed | 0.2 |

| Pressure | 0.4 |

| Temperature | 0.2 |

| CA | 0.2 |

| Mass flow rate for hydrogen | 0.4 |

| BTE | 0.6 |

| BSFC | 0.7 |

| NO x | 0.9 |

| CO | 0.04 |

| Unburnt HC | 0.13 |

4 Results and discussion

4.1 BTE

Figure 8 shows how BTE varies with braking power for various diesel (B20, B40, B50, and B100) fuels. According to the graph, the B20 blend exhibits enhanced BTE when compared to diesel fuel under part-load conditions. Due to the effect of the cetane number and heating values that are closer to those of diesel fuel, a maximum BTE of 31.94% at maximum power output is implied by the B20 blend. However, compared to diesel fuel, it was lowered by 1.92% BTE. Greater biodiesel blends have lower volatility and greater density and viscosity than lower blends; hence, the combustion characteristics of the fuel atomisation, vaporisation, and fuel–air interactions are poorer, resulting in reduced BTE [9].

BTE vs brake power.

4.2 Brake-specific energy consumption (BSEC)

The BSEC displays the test engine’s BP fuel efficiency. According to Figure 9, when BP rises, the BSEC variance decreases. At full load, diesel fuel has a BSEC of 0.314 kg·(kW·h)−1, B20 has a BSEC of 0.327 kg·(kW·h)−1, B40 has a brake-specific fuel consumption (BSFC) of 0.354 kg·(kW·h)−1, B50 has a BSFC of 0.367 kg·(kW·h)−1, and B100 has a BSEC of 0.397 kg·(kW·h)−1. With an increase in the proportion of sandbox seed oil to diesel fuel, the BSEC rises. The causes include the higher density and viscosity of the sandbox seed oil mixes and their lower heating value. Diesel, on the other hand, has a lower BSEC than other sandbox seed oil mixtures due to its higher heating value (0.43 kg·(kW·h)−1).

BSFC vs brake power.

4.3 Exhaust gas temperature (EGT)

Figure 10 shows EGT fluctuation with braking power. The EGT is a measure of how much heat is produced inside the combustion chamber in direct relation to whether full combustion occurs. The EGT is claimed to be 315°C for B20, 335°C for B40, 355°C for B50, 392°C for B100, and 298°C for diesel at peak load state. The diesel has a lower EGT than other sandbox seed oil mixes, according to the statement. This may be due to the fact that sandbox seed oil fuel mixtures burn later in the combustion process, resulting in a longer ignition delay period and more oxygen present during combustion. Similar results were achieved in several other earlier studies [10,11,12].

EGT vs brake power.

4.4 CO emission

Diesel generates more carbon dioxide (CO2) than sandbox seed oil, and Figure 11 shows their mixes at all power levels. Low-temperature combustion, lower air–fuel ratios, and an oxygen shortage in areas with abundant air–fuel mixes are the main contributors to CO production. At mid-range operation, the test engine fuel blends emit less CO than BP’s maximum allowable level. At maximum load 4, 3, 2, 1.5 and 1 g/kwhr respectively for the diesel, B20, B40, B50 and B100. Diesel fuel produces more CO2 than a gasoline blend based on B20. CO emissions are decreased when the neat sandbox seed oil in the diesel fuel blend has a higher O2 content [11]. Suresh et al. found similar CO emission output from their research.

CO vs brake power.

4.5 Unburned HC emission

Figure 12 depicts the variation of a particular unburned HC emission with BP for diesel, sandbox seed oil, and their mixtures. Pure B100 and its mixtures create less unburned HC than diesel does for all power levels. Notably, the unburned HC emission for diesel at peak BP is 0.137 g·(kW·h)−1, but it is 0.125 g·(kW·h)−1 for B20, 0.119 g·(kW·h)−1 for B40, 0.113 g·(kW·h)−1 for B50, and 0.109 g·(kW·h)−1 for B100. The high cetane number and oxygen concentration of the sandbox seed oil blends encourage thorough combustion, which lowers the production of unburned HC [12].

Unburned HC vs brake power.

4.6 NO x emission

Figure 13 shows how the percentage increase in the sandbox seed oil fuel blend enhances the generation of certain NO x emissions compared to diesel at all power settings. The specific NO x emissions for diesel (B20, B40, B50, and B100) were determined to be 9.54, 10.23, 11.55, 12.36, and 13.18 g·(kW·h)−1, respectively, at peak power output. According to the value of a certain NO x , the B100 and its mixtures emit more pollutants than diesel. Following the ignition delay period, the fuel burns more rapidly, increasing the O2 content of the sandbox seed oil mixtures and the specific NO x emissions [13].

NO x vs brake power.

4.7 In-cylinder gas pressure

Figure 14 illustrates how in-cylinder pressure fluctuates with crank angle (CA) for diesel and sandbox seed oil blends. In comparison to the B20 (70.9 bar), B40 (68.5 bar), and B50 (67.4 bar) sandbox seed oil blends, diesel has the greatest in-cylinder gas pressure. But out of all the test fuels, the B100 produced the lowest peak pressure, 66.5 bar, at 8°C after TDC. When fuel is premixed for combustion, its viscosity and density have an impact on the rate of atomisation and evaporation [14,15].

Cylinder pressure vs CA.

4.8 HRR

Figure 15 illustrates the relationship between HRR and CA for diesel, B100, B20, B40, and B50 mixes at full load. When compared to diesel and other sandbox seed oil mixes, the B20 blend exhibits enhanced combustive product burning, which leads to superior HRR. The highest HRR values for diesel, B100, B20, B40, and B50 blends are 40.23, 33.5, 36.7, 35.8, and 34.8 J·deg−1 CA, respectively, for maximum power output. As shown by the B100 and its mixes, HRR decelerates more rapidly than diesel fuel during the fast combustion phase. Reduced fuel atomisation was the outcome of the sandbox seed oil blends’ high density and low heating value. Additionally, a high cetane number mix reduces the ignition delay, which in turn impacts the rate of pressure rise and heat release [14,16].

HRR with CA.

5 Conclusions

Sandbox seed oil was produced using diesel, B20, B40, B50, and pure B100 blends in this experiment. The originality of this study is summed up as follows, based on the experimental results:

Compared to diesel fuel, sandbox seed oil and its mixtures have more similar characteristics. Because of this, it can be used in diesel engines without modification.

At the part-load condition, the B20 blend exhibits better BTE in comparison to other test fuels. As BSEC increased by 1.93% compared to diesel at maximal power production, it reduced BTE by 1.78%.

Compared to diesel, the B20 blend decreased unburned HC by 7.13%, unburned CO by 16.27%, and smoke opacity by 8.13 at maximum power output. It may be a result of the ignition delay time being shortened, the rich oxygen content, and better fuel characteristics.

However, compared to diesel, the NO x emission with the B20 blends was greater by 2.10%. The availability of oxygen, elevated in-cylinder gas temperatures, and delayed ignition at the greatest load conditions are the main factors contributing to the rise in NO x emissions.

It was possible to reduce the ignition delay, in-cylinder gas pressure, and HRR by using neat B20 as well as its mixtures. When compared to diesel, it was discovered that the improved combustion diffusion portion resulted in greater EGT for all loading circumstances.

Based on the results of this exhaustive experimental analysis, a B20 blend can be used as an alternative fuel source for a stock diesel engine. With better fuel combustion and performance characteristics, tailpipe emissions are significantly reduced. To reduce NO x production, experimental research may be expanded for diesel engines running on sandbox seed oil mixtures, and the CRDI engines can be included in future experimental investigations. Future studies are required to examine the effects of different compression ratios and to discriminate between the combustion behaviours of diesel and biodiesel with varying EGR rates.

Acknowledgments

This experiment has been carried out in Bharath University, Chennai Tamil Nadu, and India. Authors would like to thank Lab expert of Bharath University for the technical assistance.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Arunachalam Veerasamy: investigation, writing – original draft. Naveenchandran Pancharam: methodology and supervision. Balu Pandian: visualisation. Silambarasan Rajendran: conceptualisation.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

[1] Ngige GA, Ovuoraye PE, Igwegbe CA, Fetahi E, Okeke JA, Yakubu A, et al. RSM optimization and yield prediction for biodiesel produced from alkali-catalytic transesterification of pawpaw seed extract: Thermodynamics, kinetics, and Multiple Linear Regression analysis. Digit Chem Eng. 2023;6:100066. 10.1016/j.dche.2022.100066.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Uyumaz A. Combustion, performance and emission characteristics of a DI diesel engine fueled with mustard oil biodiesel fuel blends at different engine loads. Fuel. 2018;212:256–67. 10.1016/j.fuel.2017.09.005.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Sudeshkumar MP, Francis Xavier JR, Balu P, Jayaseelan V, Sudhakar K. Waste plastic oil to fuel: an experimental study in thermal barrier coated CI engine with exhaust gas recirculation. Environ Qual Manage. 2022;32(1):125–31. 10.1002/tqem.21853.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Tan D, Wu Y, Lv J, Li J, Ou X, Meng Y, et al. Performance optimization of a diesel engine fueled with hydrogen/biodiesel with water addition based on the response surface methodology. Energy. 2023;263:125869. 10.1016/j.energy.2022.125869.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Ogunkunle O, Ahmed NA. Exhaust emissions and engine performance analysis of a marine diesel engine fuelled with Parinari polyandra biodiesel – diesel blends. Energy Rep. 2020;6:2999–3007. 10.1016/j.egyr.2020. 10.070.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Hasan MM, Rahman MM. Performance and emission characteristics of biodiesel-diesel blend and environmental and economic impacts of biodiesel production: A review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;74:938–48. 10.1016/j.rser.2017.03.045.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Zhang Z, Wang S, Pan M, Lv J, Lu K, Ye Y, et al. Utilization of hydrogen-diesel blends for the improvements of a dual-fuel engine based on the improved Taguchi methodology. Energy. 2024;292:130474. 10.1016/j.energy.2024.130474.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Harigaran A, Balu P. An experimental study on the performance and emission characteristics of a single-cylinder diesel engine running on biodiesel made from palm oil and antioxidant additive. Int J Ambient Energy. 2023;44(1):1076–80. 10.1080/01430750.2022.2162577.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Purushothaman P, Gnanamoorthi V, Gurusamy A. Performance combustion and emission characteristics of novel biofuel peppermint oil in diesel engine. Int J Environ Sci Technol. 2019;16:8547–56. 10.1007/s13762-019-02270-1.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Rosha P, Kumar S, Kumar S, Cho H, Singh B, Dhir A. Effect of compression ratio on combustion, performance, and emission characteristics of compression ignition engine fueled with palm (B20) biodiesel blend. Energy. 2019;178:676–84. 10.1016/j.energy.2019.04.185.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Chiedu OC, Ovuoraye PE, Igwegbe CA, Tahir MA, Okeke JA, Egwuatu C, et al. Central composite design optimization of the extraction and transesterification of tiger nut seed oil to biodiesel. Process Integr Optim Sustain. 2024;8:503–21. 10.1007/s41660-023-00379-y.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Balu P, Vasanthkumar P, Govindan P, Sathish T. An experimental investigation on ceramic coating with retarded injection timing on diesel engine using Karanja oil methyl ester. Int J Ambient Energy. 2023;44:1031–5. 10.1080/01430750.2022.2161632.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Suresh M, Jawahar CP, Richard A. A review on biodiesel production, combustion, performance, and emission characteristics of non-edible oils in variable compression ratio diesel engine using biodiesel and its blends. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2018;92:38–49. 10.1016/j.rser.2018.04.048.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Manimaran R, Murugu Mohan Kumar K. Experimental analysis on unmodified diesel engine characterization with novel biodiesel blends extracted from waste Trichosanthes cucumerina seeds. Energy Sources, Part A. 2021;1–21. 10.1080/15567036.2021.1905110.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Dhinesh B, Isaac Joshua J, Lalvani R, Parthasarathy M, Annamalai K. An assessment on performance, emission and combustion characteristics of single cylinder diesel engine powered by Cymbopogon flexuosus biofuel. Energy Convers Manage. 2016;117:466–74. 10.1016/j.enconman.2016.03.049.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Bhiogade GE, Sunheriya N, Suryawanshi JG. Investigations on premixed charge compression ignition (PCCI) engines: a review. In: Saha A, Das D, Srivastava R, Panigrahi P, Muralidhar K, editors. Fluid mechanics and fluid power – Contemporary research. Lecture notes in mechanical engineering. New Delhi: Springer; 2017. 10.1007/978-81-322-2743-4_139.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”