Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

-

Anila Ashraf

, Muhammad Shahbaz

Abstract

Graphene oxide (GO) and reduced graphene oxide (rGO) nanoparticles were synthesized using 40 mL of lemon juice extract as a reducing agent. The synthesized nanoparticles were characterized using various analytical techniques, including UV–visible spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, and X-ray diffraction. The results confirmed the successful synthesis of GO and rGO nanoparticles with varied sizes and shapes. The synthesized nanoparticles were tested for their antimicrobial activity against a range of bacterial and fungal strains, including Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Candida albicans, Fusarium oxysporum, and Aspergillus flavus. Multiple concentrations of GO and rGO nanoparticles were tested, and it was observed that 100 µg·mL−1 of both GO and rGO showed the highest inhibitory effect against bacterial and produced zones of inhibition of 17.66 mm, 18.67 mm, and 17.88 for E. coli, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae and 20.33, 22.45, and 21.34 mm for C. albicans, F. oxysporum, and A. flavus. Comparatively, GO performed well as compared to rGO regarding antimicrobial activity. The synthesized nanoparticles exhibited significant antimicrobial activity against various bacterial and fungal strains and have the potential to be developed as novel antimicrobial agents.

1 Introduction

In the current era, nanotechnology has a wide range of applications, producing tiny nanoparticles with diameters between 1 and 100 nm, which are crucial for the treatment of many diseases [1,2,3]. Due to their large surface-to-volume ratio and high surface energies, these particles have a variety of biomedical purposes [4,5]. Nanoparticles (NPs) are among the most frequently produced and used particles due to their outstanding properties, including their antibacterial and antioxidant activities, biocompatibility, and optical-polarizability [6]. In terms of catalysts, antimicrobials, antioxidants, memory aids, and cancer therapies, nanoparticles have a promising effect over other substances like Zn, Fe, Mn, Se, Cu, Ag, and Si [7]. Antimicrobial resistance represents a substantial and escalating global challenge necessitating novel strategies for addressing infections induced by antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains [8,9]. Metallic nanoparticles such as silver (Ag), gold (Au), copper oxide (CuO), iron oxide (Fe3O4), titanium oxide (TiO2), or zinc oxide (ZnO) are frequently employed as antimicrobial agents due to their established potent antimicrobial activity [10]. Numerous investigations have demonstrated the biocidal efficacy of diverse metal and metal oxide nanoparticles against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, fungi, and viruses [1,11]. The antimicrobial properties of metallic nanoparticles are profoundly influenced by their elevated specific surface area, high surface-to-volume ratio, and nanoscale dimensions, facilitating robust interactions with microorganism membranes. This interaction results in membrane disruption, cellular penetration, and subsequent damage to internal cellular structures, ultimately culminating in cell demise [12].

Graphene is a carbon-based material consisting of a single layer of sp2-bonded atoms with exceptional properties such as high surface area (2,630 m2·g−1), high electrical conductivity (2,000 S·cm−1), high thermal conductivity (4,840–5,300 W·m−1·K−1), high electronic carrier mobility (200,000 cm2·V−1·s−1), and high Young’s modulus (10 TPa) [13,14,15,16]. These properties make graphene a potential material for a wide range of applications. Graphene oxide (GO) is a modified form of graphene that contains extra oxygen functional groups, including epoxides, hydroxyl, carboxyl, and carbonyl groups on its edges and basal planes. GO-based coatings have been investigated for their potential to enhance the antibacterial properties of titanium implants [17,18,19,20]. The negatively charged and hydrophilic nature of GO facilitates interaction with osteoblasts, making it a promising material for implant applications. The sharp edges of GO can cause damage to the outer membranes of bacterial cells, as observed in studies on the antibacterial properties of GO and hydroxyapatite composites [20,21].

Studies have shown that both GO and reduced graphene oxide (rGO) possess antibacterial properties and can disrupt bacterial cell membranes with their sharp edges [21]. GO and rGO containing oxygen functional groups can oxidize glutathione, a redox mediator in bacteria, and thus reduce bacterial growth. rGO has been found to possess higher oxidation capacity than GO, graphite, and graphite oxide [22].

The emergence of multidrug-resistant microorganisms has become a major global health concern, necessitating the development of novel therapeutic strategies. Antimicrobial materials can be used to prevent microbial contamination and pathogen transmission in various settings, such as biomedical instruments and food delivery containers [23–26].

Graphene materials are advantageous than traditional antibiotics due to physical action mechanisms which contribute to decreased chances of microbial resistance. The surface oxygen content variation of these materials is the key factor for the antibacterial activity [27]. Therefore, the present study was conducted to synthesize the GO and rGO nanoparticles, and to check their antimicrobial activity against selected fungal and bacterial strains.

1.1 Preparation of extract

The lemon juice extract was prepared by acquiring fresh lemons from the local market in District Bagh, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan. Thorough cleaning and squeezing yielded 40 mL of juice, subsequently heated for 10 min, filtered, and diluted with distilled water to produce 50 mL. To enhance reproducibility, the method involved rigorous standardization, encompassing consistent extraction protocols. The resulting mixture underwent additional stirring for 15 min at room temperature, followed by filtration. This extract was then combined with a solution of 4.7 g KMnO4 in 100 mL water, acidified with 2.5 mol·L−1 H2SO4. After an hour of vigorous stirring, the purple color of the KMnO4 solution transformed to black, indicating a complete reduction by the lemon juice extract. The ensuing precipitate was isolated, washed thoroughly to eliminate potassium ions, and subsequently dried overnight at 90°C, followed by calcination at 300–400°C for 5 h under ambient atmosphere [28].

1.2 Synthesis of GO

GO was prepared using 5 g of graphite and 2.5 g of sodium nitrate into 120 mL of 95% H2SO4. The resultant solution was placed in an ice bath, stirred for 30 min, and 15 g of potassium permanganate was added with stirring at less than 20°C temperatures. After that 150 mL of distilled water was added slowly and the solution on a magnetic stirrer overnight. After increasing the temperature from 20 to 98°C, 30% hydrogen peroxide was added to the solution. The product was washed using 5% methanolfollowed with distilled water. Finally, the product was obtained after drying.

Reduction of GO: GO 80 mg was mixed with 50 mL of distilled water and subjected to sonication for 40 min at 30°C temperature. Finally, lemon juice extract was added into the solution and refluxed for 45 min. At this stage, GO changed into rGO, which is washed with distilled water, dried, and stored at 4°C for further use [28,29].

1.3 Characterization

In this study, UV–visible spectroscopy was utilized to confirm the synthesis of GO and rGO. The morphology and size of the GO nanoparticles were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), which involved the acquisition of images with a conventional secondary electron detector and a 10-kV electron beam. To determine the functional groups present in GO and rGO (rGO), Fourier transformed infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was employed, with different wavelengths plotted on an FTIR graph to identify various functional groups. The crystalline nature of the synthesized GO nanoparticles was determined using X-ray diffraction (XRD) at the NCP, Islamabad, with NPs powdered samples placed on Shimadzu XRD-6000 and set in the range of 5°–50° at a 2θ angle. The average size of the nanoparticles was determined using Debye–Scherer’s equation, which considers the shape factor (K), X-ray wavelength (λ), full width in radius at half maximum (β), and Bragg’s angle (θ) (Table 1).

Experimental design

| Sr. no. | Treatments | Concentrations |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | T1 | (Drug) 100 µg·mL−1 |

| 2 | T2 | 75 µg·mL−1 GO |

| 3 | T3 | 100 µg·mL−1 GO |

| 4 | T4 | 75 µg·mL−1 rGO |

| 5 | T5 | 100 µg·mL−1 rGO |

1.4 Experimental layout

1.4.1 Source of test organisms

All organisms used in this study included Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Candida albicans, Fusarium oxysporum, and Aspergillus flavus were obtained from the Department of Microbiology, QAU Islamabad.

1.4.2 Antifungal activity

Standard protocols were employed for media preparation in this study. To prepare 1 L of media, 39 g of PDA was dissolved in 1,000 mL of distilled water. The fungal culture was streaked onto the media, and 20 mL of the PDA media was poured into each Petri plate and solidified. Then, 25 µL of the samples were placed onto the discs. The petri plates were incubated at 25°C for 96 h. Three replications were used for all the treatments and experiments were performed in duplicate. The inhibition zone was measured in mm using a regular scale [30].

1.4.3 Antibacterial activity

In this study, bacterial growth was supported by nutrient agar media, which was prepared following standard microbiological principles. Nutrient agar and nutrient broth were separately prepared in 500-mL flasks, which were covered with aluminum foil and autoclaved at 121°C and 15 psi for 15 min. After autoclaving, the media was transferred to a laminar flow hood. Petri plates were filled with 20 mL of the media and left to solidify before incubation at 37°C for 24 h. Mueller Hinton Agar (MHA) was used for antimicrobial assays, and the inoculate of test microbes was prepared using the colony suspension method. Microbial suspensions were standardized to a concentration of 1.5 × 108 cfu·mL−1 by comparing with 0.5 McFarland standards. The Modified Kirby–Bauer diffusion technique was employed for antibiotic susceptibility testing. Standardized microbial saline suspensions were swabbed onto Mueller–Hinton agar (MHA) plates, and 7-mm filter paper discs impregnated with 20 µL of each nanoparticle solution were placed on the inoculated agar plates. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Three replications were used for all the treatments and experiments were performed in duplicate. The zone of inhibition was measured after 24 h of incubation and interpreted accordingly [21].

1.4.4 Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by using Statistics 8.1 software. All the values are mean ± standard error of three replications for all treatments of the experiments.

2 Results

The synthesis of GO nanoparticles was confirmed by the formation of a brown color. The reduction of GO resulted in the appearance of an absorbance peak at 250 nm, as depicted in Figure 1(a) and (b), indicating the successful synthesis of plant-mediated GO nanoparticles. Additionally, the UV–visible spectroscopy results of GO showed the formation of an absorbance peak at 300 nm with an absorbance value of 0.81 a.u.

UV–visible spectroscopy of (a) graphene oxide and (b) reduced graphene oxide.

SEM Analysis was employed to investigate the size and morphology of GO and rGO nanoparticles synthesized through a green synthesis method. The SEM images revealed that GO possessed a two-dimensional sheet-like morphology with multiple lamellar layers, and the edges of individual sheets were clearly distinguishable. The average size of GO and rGO nanoparticles was determined to be in the range of 60–78 and 40–58 nm, respectively. Furthermore, the SEM images showed that the films of these nanoparticles were stacked in a layered manner, resulting in the formation of wrinkled areas (Figure 2a and b). The SEM analysis of rGO obtained from GONPs demonstrated the formation of an ultrathin Graphene film through the chemical reduction of GONPs.

Scanning electron microscopy of (a) graphene oxide and (b) reduced graphene oxide.

To confirm the elemental composition of plant-mediated GO and rGO, an energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis was carried out. The dominant peaks in the EDX spectra for both GO and rGO were found to be in the range of 2.7–3.7 keV. Additionally, other elements such as sodium, carbon, oxygen, silver, sulfur, phosphorus, and chlorine were identified from their respective peaks in the spectra (Figure 3a and b).

EDX of (a) reduced graphene oxide and (b) graphene oxide nanoparticles.

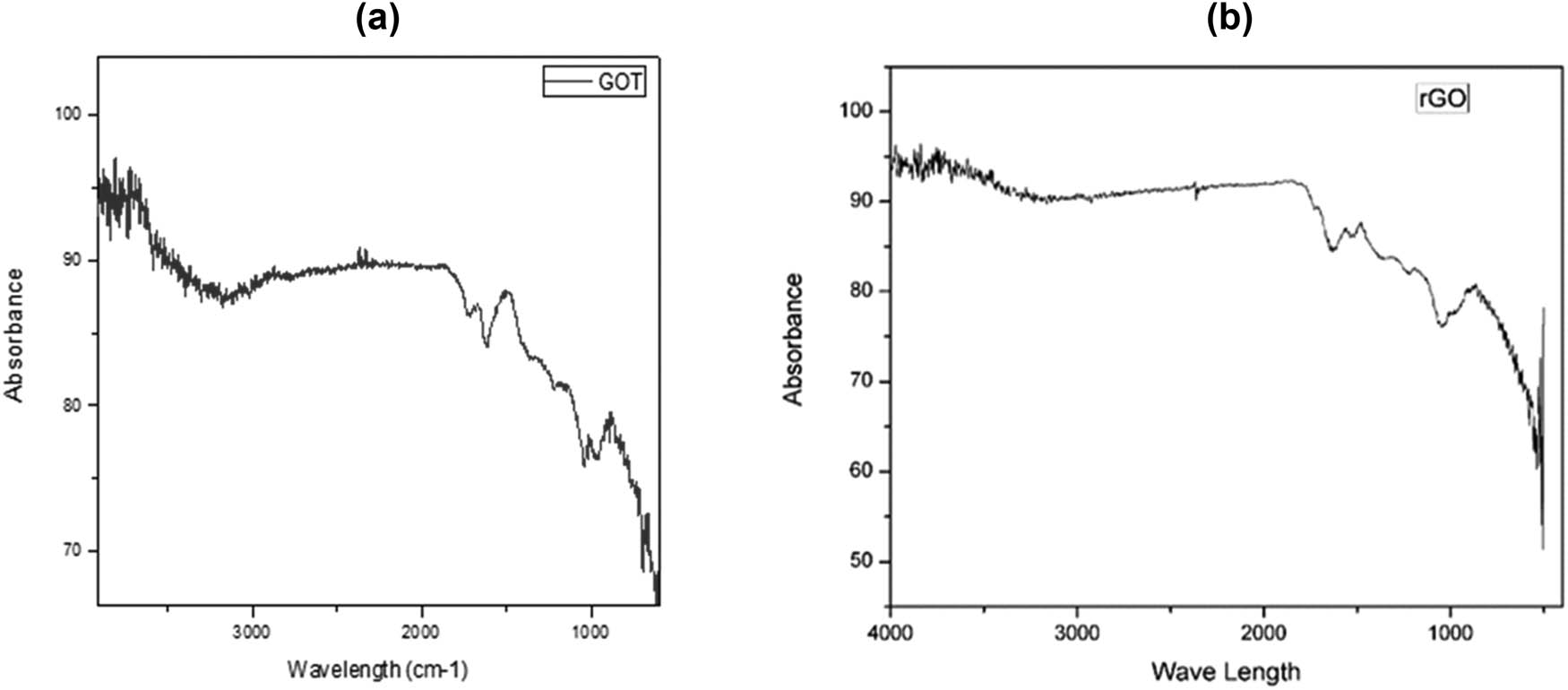

The functional groups present in GO nanoparticles were characterized using Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. The FTIR spectrum revealed the distinctive functional groups associated with GO, thereby confirming the presence of GO nanoparticles. Specifically, a broad peak at 3,306 cm−1, corresponding to the stretching vibration of the hydroxyl group, was observed. A sharp peak at 1,613 cm−1, attributed to the C═C stretching vibration, was also evident in the spectrum. Additionally, peaks at 1,222 and 1,047 cm−1 were observed, which were respectively assigned to the epoxy and alkoxy groups (Figure 4a and b).

FTIR spectrum of (a) graphene oxide and (b) reduced graphene oxide.

The green synthesis approach was employed for the reduction of GO nanoparticles to obtain rGO nanoparticles using lemons as a reducing agent. The rGO nanoparticles were analyzed using XRD, and characteristic peaks associated with rGO were observed in the XRD pattern (Figure 5a and b). Specifically, the rGO nanoparticles exhibited a distinct XRD peak at 2θ = 30, which is consistent with the literature values for the characteristic XRD peaks of rGO nanoparticles, typically found in the range of 26–30 theta.

XRD spectrum of (a) graphene oxide and (b) reduced graphene oxide.

The antibacterial activity of GO and rGO was evaluated against E. coli, S. aureus, and K. pneumoniae at concentrations of 75 and 100 µg·mL−1. Streptomycin (100 µg·mL−1) was used as a control. The zone of inhibition observed for rGO against E. coli, S. aureus, and K. pneumoniae was 17.66, 18.7, and 17.8 mm, respectively. In comparison, the zone of inhibition observed for the antibacterial drug against E. coli, S. aureus, and K. pneumoniae was 18, 20, and 22 mm, respectively. Additionally, GO was tested at the same concentrations, and maximum zones of inhibition of 13.8, 16.6, and 15.3 mm were observed against E. coli, S. aureus, and K. pneumoniae, respectively, at a concentration of 100 µg·mL−1 (Figure 6). Notably, for waste treatment [23,24], the antibacterial potential of GO nanoparticles was found to be comparable to that of the antibacterial drug. These findings align with previous research conducted by Yousefi et al. [25] regarding the antibacterial activity of GO.

Effect of different concentrations of graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide nanoparticles against selected bacterial strains.

The antifungal activity was performed against C. albicans, F. oxysporum, and A. flavus using different concentrations (75 and 100 µg·mL−1) of GO and rGO. The results revealed that 100 µg·mL−1 concentration GO and rGO performed well and produced zone of inhibition of 20.4, 22.5, and 21.3 mm using rGO and 17.02, 19.5, 20.2 mm using GO by comparing with antifungal drug that showed results 22.66, 23.55, and 23.78 mm of C. albicans, F. oxysporum, and A. flavus, respectively, as shown in Figure 7.

Effect of different concentrations of graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide nanoparticles against selected bacterial strains.

3 Discussion

GO and rGO are important materials in nanotechnology due to their unique properties and potential applications. The key difference between GO and rGO is the level of oxygen functionalization on the graphene surface, with GO having a higher degree of oxygen functionalization than rGO, resulting in significant changes in material properties. The UV absorption spectra of GO and rGO show a peak at 250 and 300 nm, respectively, indicating differences in the electronic structure of the materials. GO’s higher degree of oxygen functionalization leads to more oxygen-containing functional groups on the graphene surface, causing changes in the electronic structure and a shift in the UV absorption peak towards a higher wavelength. In contrast, rGO has fewer oxygen-containing functional groups due to lower oxygen functionalization, resulting in a different electronic structure and a shift in the UV absorption peak towards a lower wavelength.

Several studies have investigated the UV absorption properties of GO and rGO, with Wang et al. [31] reporting a strong absorption peak at around 300 nm for GO and a weaker peak at around 250 nm for rGO. Acik et al. [32] also observed a peak at around 300 nm for GO and a peak at around 270 nm for rGO. The difference in UV absorption peaks provides valuable information on the level of oxygen functionalization on the graphene surface, which can impact the material properties and potential applications.

SEM is useful for characterizing the morphology and structure of nanoparticles. The average particle size for rGO was found to be 40–58 nm, while for GO it was in the range of 60–78 nm in the results. The difference in particle size can be attributed to the different synthesis methods used to prepare GO and rGO. The synthesis method for GO involves the oxidation of graphite to form a GO precursor, which can form large sheets with many oxygen-containing functional groups, leading to larger particle sizes for the final GO product. In contrast, rGO is prepared by reducing GO, leading to the formation of smaller nanoparticles due to the removal of oxygen-containing functional groups from the GO surface. Studies by Hummers Jr and Offeman [33] and Xu et al. [34] reported particle sizes of 50–80 nm for GO and 20–40 nm for rGO, respectively, using SEM.

The EDX results indicate that rGO nanoparticles contain chlorine, phosphorus, sulfur, silver, and oxygen, while GO nanoparticles contain silver, sodium, carbon, oxygen, and phosphorus. These differences in elemental composition can be attributed to variations in the synthesis methods employed. During the oxidation process in the preparation of GO, various oxygen-containing functional groups can form, leading to the incorporation of elements such as sodium and phosphorus. Additionally, the use of silver nitrate as a catalyst in the synthesis process can explain the presence of silver in the GO sample. On the other hand, the reduction process used in the preparation of rGO can introduce impurities such as chlorine, which may arise from the use of reducing agents or surfactants. The presence of silver in the rGO sample may be due to the use of silver ions in the reduction process.

Previous studies have also reported the elemental composition of GO and rGO nanoparticles using EDX analysis. Wang et al. [31] found oxygen, carbon, and silicon in GO nanoparticles, while rGO nanoparticles contained oxygen, carbon, and sulfur. Similarly, Zhang et al. [35] reported the presence of carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen in GO nanoparticles and carbon, oxygen, and sulfur in rGO nanoparticles.

The infrared (IR) spectra of both GO and L-cysteine reduced GO (LCrGO) were analyzed, revealing an intense absorption peak at 3,352 and 3,224 cm−1 that can be attributed to the OH extending vibration of the phenol or alcoholic functional group. Another absorption band was observed at 2,925 cm−1 in LCrGO, representing the C–H group. The absence of the carbonyl group at 1,722 cm−1 in LCrGO compared to GO confirmed the effective reduction of GO. The presence of C═C bond was confirmed by the appearance of a band at 1,621 cm−1 in GO and 1,587, 1,647 cm−1 in LCrGO. Similar functional groups were also reported by other researchers [36].

The GO diffraction pattern showed a prominent peak at 2θ = 11.3°, corresponding to the graphene oxide plate (002), and a weak peak at about 2θ = 26.4°, which is usually caused by unaffiliated graphite. The transformation of the GO structure due to the hydrothermal process led to the disappearance of some oxygenated groups, resulting in a prominent peak at 2θ = 11.3° and a weak peak at 2θ = 26.4°. These findings are consistent with previous reports by Sajjad et al. [37].

Both the GO and rGO showed antagonistic activity against bacterial and fungal pathogens. The inhibition activity of antibacterial and antifungal drugs is more than nanoparticles but it is still important to consider nanoparticles as an alternative to drugs. Microorganisms may develop resistance by limiting drug uptake, target drug modification, drug inactivation, and drug efflux [38]. The pathogenic microorganisms may develop resistance to multiple drugs, and production of these drugs is complex and costly. It is easy to synthesize nanoparticles; especially, the plant extract–oriented synthesis of nanoparticles is easy and economically affordable. So, we should consider the optimization of the biosynthesis of nanoparticles for our well-being. The GO and rGO nanoparticles have been reported to have antifungal effects by potentially invading the cell membrane and disrupting its integrity, leading to leakage of vital cell materials and cell death [39]. The Go and rGO nanomaterials produced reactive oxygen species and showed antibacterial activity against E. coli and Bacillus subtilis by surface modification of membrane filters [40]. GO and rGO nanoparticles have also been used to suppress Alternaria alternata causing tomato leaf blight, with a dose of 100 μg·mL−1 resulting in an inhibition percentage of 89.6% [41]. In addition, GO and rGO nanoparticles were applied against Alternaria solani, a causal agent of early blighting potatoes resulting in a 100% inhibition at a concentration of 80 ppm [42]. These findings are consistent with those reported by Whitehead et al. [43].

4 Conclusion

The objective of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of GO nanoparticles (GO NPs) against selected bacterial and fungal strains. These findings demonstrate the potential of GO NPs as effective antimicrobial agents against bacterial and fungal strains and suggest that they could be a promising candidate for the development of novel antimicrobial agents. Further, research is necessary to explore their potential clinical applications and toxicity profiles.

-

Funding information: This research work was funded by the Institutional Fund projects under grant no. (IFPIP: 1823-141-1443). Therefore, the authors gratefully acknowledge technical and financial support from the Ministry of Education and King Abdulaziz University (KAU), Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR), Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contributions: All authors of this research article have contributed significantly to the literature study, writing, and methodology, and critically revised the research article. A. A.: conceptualization/conceived the study idea, planned and designed the research structure, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, data validation, visualization, customized images, and final draft. M. A., and T. H. supervised the research, and drafting process, and revised the first draft. M.S: formal analysis, validation, resources, suggestions. F. A.: and M. I., conceptualization, data curation, review editing, software and validation, F. Y. methodology, visualization, validation, and final editing of manuscript. Funder: helped with data validation and interpretation, guided the draft write-up, and carried out a critical revision of the final draft; and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Sharmin S, Rahaman MM, Sarkar C, Atolani O, Islam MT, Adeyemi OS. Nanoparticles as antimicrobial and antiviral agents: A literature-based perspective study. Heliyon. 2021;7(3):06456.10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06456Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Hassan HU, Raja NI, Abasi F, Mehmood A, Qureshi R, Manzoor Z, et al. Comparative study of antimicrobial and antioxidant potential of olea ferruginea fruit extract and its mediated selenium nanoparticles. Molecules. 2022;27(16):5194.10.3390/molecules27165194Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Sadiq S, Akhtar S. The efficacy of common windmill butterfly’s silver nanoparticles against bacterial pathogens. J Wildl Ecol. 2023;7(2):35–43.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Shahbaz M, Akram A, Raja NI, Mukhtar T, Mashwani ZUR, Mehak A, et al. Green synthesis and characterization of selenium nanoparticles and its application in plant disease management: A review. Pak J Phytopathol. 2022;34(1):189–202.10.33866/phytopathol.034.01.0739Search in Google Scholar

[5] Duhan JS, Kumar R, Kumar N, Kaur P, Nehra K, Duhan S. Nanotechnology: The new perspective in precision agriculture. Biotechnol Rep. 2017;15:11–23.10.1016/j.btre.2017.03.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Hatamifard A, Nasrollahzadeh M, Sajadi SM. Biosynthesis, characterization and catalytic activity of an Ag/zeolite nanocomposite for base-and ligand-free oxidative hydroxylation of phenylboronic acid and reduction of a variety of dyes at room temperature. N J Chem. 2016;40(3):2501–13.10.1039/C5NJ02909KSearch in Google Scholar

[7] Khodadadi B, Bordbar M, Nasrollahzadeh M. Achillea millefolium L. extract mediated green synthesis of waste peach kernel shell supported silver nanoparticles: application of the nanoparticles for catalytic reduction of a variety of dyes in water. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2017;493:85–93.10.1016/j.jcis.2017.01.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Salam MA, Al-Amin MY, Salam MT, Pawar JS, Akhter N, Rabaan AA. et al. Antimicrobial resistance: A growing serious threat for global public health. Healthcare. 2023;11:1946.10.3390/healthcare11131946Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Nazer S, Butt I, Fatima I. Antibacterial and synergistic potential of scale extracts from Oreochromis mossambicus against bacterial pathogens. J Wildl Ecol. 2023;7(1):11–9.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Beyth N, Houri-Haddad Y, Domb A, Khan W, Hazan R. Alternative antimicrobial approach: Nano-antimicrobial materials. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2015;2015:246012.10.1155/2015/246012Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Manzoor I, Safeer B. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles from skin of Labeo rohita and their application of biocide. J Wildl Ecol. 2022;6(3):129–40.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Wang L, Hu C, Shao L. The antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles: present situation and prospects for the future. Int J Nanomed. 2017;12:1227–49.10.2147/IJN.S121956Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Novoselov KS, Geim AK, Morozov SV, Jiang D, Zhang Y, Dubonos SV, et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science. 2004;306(5696):666–9.10.1126/science.1102896Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Balandin AA, Ghosh S, Bao W, Calizo I, Teweldebrhan D, Miao F, et al. Superior thermal conductivity of single-layer graphene. Nano Lett. 2008;8(3):902–7.10.1021/nl0731872Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Bolotin KI, Sikes KJ, Jiang Z, Klima M, Fudenberg G, Hone J, et al. Ultrahigh electron mobility in suspended graphene. Solid State Commun. 2008;146(9–10):351–5.10.1016/j.ssc.2008.02.024Search in Google Scholar

[16] Lee C, Wei X, Kysar JW, Hone J. Measurement of the elastic properties and intrinsic strength of monolayer graphene. Science. 2008;321(5887):385–8.10.1126/science.1157996Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Kim K, Ahn SI, Choi KC. Simultaneous synthesis and patterning of graphene electrodes by reactive inkjet printing. Carbon. 2014;66:172–7.10.1016/j.carbon.2013.08.055Search in Google Scholar

[18] Tanurat P, Sirivisoot S. Osteoblast proliferation on graphene oxide eletrodeposited on anodized titanium. Paper presented at: 2015 8th Biomedical Engineering International Conference (BMEiCON); 2015.10.1109/BMEiCON.2015.7399572Search in Google Scholar

[19] Gu M, Lv L, Du F, Niu T, Chen T, Xia D, et al. Effects of thermal treatment on the adhesion strength and osteoinductive activity of single-layer graphene sheets on titanium substrates. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):8141.10.1038/s41598-018-26551-wSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Zhu Y, Murali S, Cai W, Li X, Suk JW, Potts JR, et al. Graphene and graphene oxide: Synthesis, properties, and applications. Adv Mater. 2010;22(35):3906–24.10.1002/adma.201001068Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Liu S, Zeng TH, Hofmann M, Burcombe E, Wei J, Jiang R, et al. Antibacterial activity of graphite, graphite oxide, graphene oxide, and reduced graphene oxide: membrane and oxidative stress. ACS Nano. 2011;5(9):6971–80.10.1021/nn202451xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Hu W, Peng C, Luo W, Lv M, Li X, Li D, et al. Graphene-based antibacterial paper. ACS Nano. 2010;4(7):4317–23.10.1021/nn101097vSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Burdușel A-C, Gherasim O, Grumezescu AM, Mogoantă L, Ficai A, Andronescu E. Biomedical applications of silver nanoparticles: An up-to-date overview. Nanomaterials. 2018;8(9):681.10.3390/nano8090681Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Habib S. Antibacterial activity of biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles using skin of Kashmir Nadi Frog Paa barmoachensis. J Wildl Ecol. 2022;6(1):07–12.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Yousefi N, Wong KKW, Hosseinidoust Z, Sørensen HO, Bruns S, Zheng Y, et al. Hierarchically porous, ultra-strong reduced graphene oxide-cellulose nanocrystal sponges for exceptional adsorption of water contaminants. Nanoscale. 2018;10:7171–84.10.1039/C7NR09037DSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Zainab S. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of Bull frog Hoplobatrachus tigerinus skin extract. J Wildl Ecol. 2021;5:32–7.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Guo Z, Zhang P, Xie C, Voyiatzis E, Faserl K, Chetwynd AJ, et al. Defining the surface oxygen threshold that switches the interaction mode of graphene oxide with bacteria. ACS Nano. 2023;17(7):6350–61.10.1021/acsnano.2c10961Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Hashem AM, Abuzeid H, Kaus M, Indris S, Ehrenberg H, Mauger A, et al. Green synthesis of nanosized manganese dioxide as positive electrode for lithium-ion batteries using lemon juice and citrus peel. Electrochim Acta. 2018;262:74–81.10.1016/j.electacta.2018.01.024Search in Google Scholar

[29] Aunkor M, Mahbubul I, Saidur R, Metselaar H. The green reduction of graphene oxide. RSC Adv. 2016;6(33):27807–28.10.1039/C6RA03189GSearch in Google Scholar

[30] Wareen G, Saeed M, Ilyas N, Asif S, Umair M, Sayyed RZ, et al. Comparison of pennywort and hyacinth in the development of membraned sediment plant microbial fuel cell for waste treatment. Chemosphere. 2023;313:137422.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.137422Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Wang X, Sun G, Routh P, Kim D-H, Huang W, Chen P. Heteroatom-doped graphene materials: syntheses, properties and applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43(20):7067–98.10.1039/C4CS00141ASearch in Google Scholar

[32] Acik M, Mattevi C, Gong C, Lee G, Cho K, Chhowalla M, et al. The role of intercalated water in multilayered graphene oxide. ACS Nano. 2010;4(10):5861–8.10.1021/nn101844tSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Hummers Jr WS, Offeman RE. Preparation of graphitic oxide. J Am Chem Soc. 1958;80(6):1339–9.10.1021/ja01539a017Search in Google Scholar

[34] Xu Y, Bai H, Lu G, Li C, Shi G. Flexible graphene films via the filtration of water-soluble noncovalent functionalized graphene sheets. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(18):5856–7.10.1021/ja800745ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Zhang P, Wang H, Zhang X, Xu W, Li Y, Li Q, et al. Graphene film doped with silver nanoparticles: self-assembly formation, structural characterizations, antibacterial ability, and biocompatibility. Biomater Sci. 2015;3(6):852–60.10.1039/C5BM00058KSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Navaee A, Salimi A. Efficient amine functionalization of graphene oxide through the Bucherer reaction: an extraordinary metal-free electrocatalyst for the oxygen reduction reaction. RSC Adv. 2015;5(74):59874–80.10.1039/C5RA07892JSearch in Google Scholar

[37] Sajjad M, Ahmad F, Shah LA, Khan M. Designing graphene oxide/silver nanoparticles based nanocomposites by energy efficient green chemistry approach and their physicochemical characterization. Mater Sci Eng: B. 2022;284:115899.10.1016/j.mseb.2022.115899Search in Google Scholar

[38] Reygaert WC. An overview of the antimicrobial resistance mechanisms of bacteria. AIMS Microbiol. 2018;4(3):482–501.10.3934/microbiol.2018.3.482Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Collado IG, Aleu J, Macías-Sánchez AJ, Hernández-Galán R. Synthesis and antifungal activity of analogues of naturally occurring botrydial precursors. J Chem Ecol. 1994;20:2631–44.10.1007/BF02036197Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Ismail A-W, Sidkey N, Arafa R, Fathy R, El-Batal A. Evaluation of in vitro antifungal activity of silver and selenium nanoparticles against Alternaria solani caused early blight disease on potato. Br Biotechnol J. 2016;12(3):1–11.10.9734/BBJ/2016/24155Search in Google Scholar

[41] Musico YLF, Santos CM, Dalida MLP, Rodrigues DF. Surface modification of membrane filters using graphene and graphene oxide-based nanomaterials for bacterial inactivation and removal. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2014;2:1559–65.10.1021/sc500044pSearch in Google Scholar

[42] Feng R, Wei C, Tu S. The roles of selenium in protecting plants against abiotic stresses. Environ Exp Bot. 2013;87:58–68.10.1016/j.envexpbot.2012.09.002Search in Google Scholar

[43] Whitehead K, Vaidya M, Liauw C, Brownson D, Ramalingam P, Kamieniak J, et al. Antimicrobial activity of graphene oxide-metal hybrids. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation. 2017;123:182–90.10.1016/j.ibiod.2017.06.020Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”