Abstract

The aim of this study is to find a solution to the challenging problem of disposing oily sludge (OS). Three different types of modifiers, namely, sodium hydroxide (NaOH), sodium dodecylbenzene sulfonate (SDBS), and polyoxyethylene polyoxypropylene polyether (AE) were employed for the simple modification of OS. The influence of modified OS on slurry ability and combustion performance were investigated. The results showed that OS modified by NaOH and SDBS can increase the concentration of coal OS slurry. However, the influence of AE modification on slurry concentration is intricate. In terms of combustion performance, the change in activation energy results in NaOH and SDBS modifications decrease T i and T h of coal OS slurry, while AE modification increases T i and T h of coal OS slurry.

Nomenclature and abbreviations list

- AE

-

polyoxyethylene polyoxypropylene polyether

- CWS

-

coal water slurry

- COSS

-

coal oily sludge slurry

- DTG

-

differential thermal gravimetry

- FT-IR

-

Fourier transform infrared spectrometer

- NaOH

-

sodium hydroxide

- OS

-

oily sludge

- RD

-

Ruide coal

- SC1000

-

slurry concentration corresponding to apparent viscosity of 1,000 mPa·s

- SDBS

-

sodium dodecylbenzene sulfonate

- SEM-EDX

-

scanning electron microscopy/energy-dispersive X-ray technique

- TG

-

Thermogravimetric analysis

- E

-

activation energy

- H water

-

height of water

- H slurry

-

height of slurry

- K max

-

maximum weight loss rate

- K mean

-

average weight loss rate

- k 0

-

frequency factor

- R

-

universal gas constant

- T

-

reaction temperature

- T h

-

burnout temperature

- T i

-

ignition temperature

- T max

-

temperature at the maximum weight loss rate

- n

-

reaction order

- α

-

coal conversion rate

- β

-

heating rate

- η

-

apparent viscosity

- γ

-

mass ratio of OS to the entire slurry

1 Introduction

Oily sludge (OS) generally refers to a complex and stable waste composed of oil, water, and sludge residue generated in oil field development, crude oil storage and transportation, and wastewater treatment facilities of chemical plants. It contains heavy metals, solid fine particles, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [1], typically with high viscosity and challenging handling characteristics [2,3,4]. The direct discharge of untreated sludge can harm the environment and pose risks to human health [5,6]. In recent years, with the increase in petroleum production, there has been a growing amount of OS generated. The demand for the proper disposal of OS is urgent and has become a pressing issue of concern, gradually evolving into a hotspot of scholarly research [7,8]. The coal water slurry (CWS) technology developed in the 1970s has gradually gained advantages such as good fluidity, high combustion efficiency, and low pollution [9]. A typical CWS consists of 60–70% coal, 30–40% water, and appropriate amount of chemical additives [10,11]. Due to the high moisture and oil phase in OS, a coal oily sludge slurry (COSS) is prepared by blending OS with coal for use as combustion and gasification feedstock, which offers the advantages of saving coal and water used in pulp preparation [12]. Moreover, the high-temperature and high-pressure environment in the furnace facilitates the degradation of harmful substances, and heavy metals in OS can be immobilized in the ash, some metallic elements can also lower the ash fusion temperature of coal [13].

Different types of slurries, such as coal–water slurry, fly ash–water slurry, oil–water emulsion, clay–water slurry, and food slurry, have drawn interest in industrial applications. The rheology of the slurry has been identified as an important criterion for determining the pressure drop requirements [14,15]. Researchers investigated the feasibility of utilizing coal sludge water slurry technology to dispose sludge from different industries. After the addition of sludge, the slurry exhibited optimal rheological behavior and stability [16,17,18], and its combustion performance was improved [19,20,21,22]. However, the addition of sludge increases the apparent viscosity (η) and decreases the concentration of the slurry [9,23,24]. Therefore, it is essential to modify the sludge for blending. Compared to untreated sludge, modified sludge with alkali or salt increases the concentration of the slurry. Liu et al. [25] found that after CaO-modification, the η of the slurry decreased from 1,635.3 to 1,082.2 mPa·s. Chu et al. [26] found that after sodium hydroxide (NaOH)-modification, the slurry concentration increased from 55.73% to 58.75%. Jiang et al. [27] found that the sludge modified by KCl, AlCl3, and high content CaCl2 reduce η of the slurry. Liu et al. [28] found Cu2+ reduce η of the slurry.

These studies only discuss the research on single modification method for sludge, lacking comparative studies on different types of modifiers. We modified OS through alkali, anionic, and non-ionic modifiers and investigated the influence of concentration, η, and micro-morphology of COSS with different modifiers. If the OS is directly blended into CWS, it may reduce the combustion performance of the slurry. Thus, combustion experiments and kinetic calculations were performed, aiming to investigate the impact of modification on the combustion performance of COSS, which provides essential support for future practical applications in treating OS.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

The experimental samples, Ruide coal (RD) was procured from the Zunger Qi region in Ordos, Inner Mongolia (Northwest, China), and OS was generated from the oily wastewater treatment of a petrochemical enterprise. The coal sample was processed according to GB/T 18,855-2,008, making its average particle diameter at approximately 74 μm.

The measurement results of the coal sample’s proximate analysis, ultimate analysis, heating value, grindability index, and other parameters are shown in Table 1.

Proximate and ultimate analysis of RD

| Sample | Proximate analysis (%) | Ultimate analysis (%) | Q b,ad (MJ·kg−1) | HGI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ad | A ad | V ad | FCad | C ad | H ad | O ad | N ad | S t,ad | |||

| RD | 11.35 | 6.71 | 29.94 | 52.15 | 66.50 | 3.72 | 10.77 | 0.70 | 0.25 | 26.34 | 55 |

According to Table 1, RD can be categorized as having moderate moisture, low ash content, moderately high volatile matter, and low fixed carbon. RD has a low ash content, with a slurry concentration of 63% for single coal. When adding OS for pulping, it can offset the influence of the high ash content of OS on the gasification process. It exhibits relatively low sulfur content but a high oxygen content of up to 10.77%, and lower grindability.

Table 2 presents the component analysis of OS. The moisture content was determined using the distillation method as per GB/T 260-2,016 for measuring moisture content in petroleum products. The oil content was determined following SY/T 5,118-2,005 for the determination of chloroform asphalt in rocks. The four components of the oil phase were analyzed based on SY/T 5,119-2,016 for measuring soluble organic compounds and crude oil components in rocks.

Composition analysis of OS

| Sample | Composition of OS (wt%) | Four components in the oil phase (wt%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil | Moisture | Sludge | Alkanes | Aromatics | Non-Hydrocarbons | Asphaltene | |

| OS | 12.33 | 63.89 | 23.78 | 58.36 | 15.82 | 19.04 | 6.78 |

From the data in Table 2, OS has typical component concentration and characteristics. OS has a high moisture content and contains sludge. However, it contains approximately 12% of a usable oil phase. The oil phase consists mainly of alkanes, accounting for 58.36%, along with approximately 15–20% of aromatics and non-hydrocarbon substances. Additionally, there is a small amount of asphaltene in the oil phase.

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Preparation of CWS and COSS

The experiment employed a dry method for slurry preparation. A predetermined quantity of coal powder, deionized water, and a dispersant were poured into a beaker and continuously stirred at 1,500 rpm for 7 min to ensure thorough mixing, resulting in the preparation of CWS. A predetermined quantity of coal powder and OS were poured into a beaker, and stirred at 500 rpm for 3 min continuously, then deionized water and a dispersant were added, and the slurry was stirred continuously at 1,500 rpm for 7 min to ensure thorough mixing, resulting in the preparation of COSS. The particles in the fuel are evenly distributed through the use of an electric mixer. The blending ratio of OS, denoted as γ, is defined as the mass ratio of OS to the entire slurry.

2.2.2 CWS and COSS performance experiments

The η of CWS and COSS was determined using an NXS-4C CWS viscometer at different shear rates. According to GB/T 18,856.4-2,015, the average viscosity of slurry at a shear rate of 100 s−1 is taken as η of the slurry. The determination of SC1000 (the slurry concentration corresponding to η of 1,000 mPa·s) is used to evaluate the concentration of the slurry through linear interpolation. The slurry drainage rate was determined using a test tube method, where the drainage rate is calculated as H water/H slurry × 100% after 24 h. The precipitation hardness of the slurry was determined by the rod penetration method: no drop indicates hard precipitation, dropping to the bottom indicates soft precipitation, dropping to 1/3 of the slurry height indicates partial soft precipitation, and dropping to 2/3 of the slurry height indicates partial hard precipitation.

2.2.3 Methods of relevant characterization of COSS

The apparent morphology and micro-area chemical composition of COSS is analyzed using a scanning electron microscope with an energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (SEM-EDX) (TESCAN VEGA3 SBH-BRUKER XFlash 6|30). The accelerating voltage is set at 30 kV.

The zeta potential of COSS is measured using a JS94H microelectrophoresis apparatus, The measurement is repeated three times, and the average value is taken as the zeta potential of the sample.

The Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) analysis of COSS is conducted using a Nicolet iS50 FT-IR Spectrometer. The instrument is configured with a resolution of 4 cm−1, and each sample is scanned 32 times per minute. The experiments are carried out in the wavelength range of 400–4,000 cm−1.

The contact angle between COSS and water is measured using the Dataphysics OCA40 standard optical contact angle instrument, and the contact angle is determined by measuring the angle between water droplet and COSS interface.

2.2.4 Thermogravimetry analysis

The samples are subjected to thermal analysis experiments using NETZSCH STA449F3 synchronous thermal analyzer. Each sample mass is approximately 30 mg, and the heating rate is set at 10°C·min−1 within a temperature range of 30°C to 1,000°C. The atmosphere used during the analysis is air, with a composition of 79% nitrogen and 21% oxygen.

3 Results and discussions

3.1 Influence of blending OS on the concentration of COSS

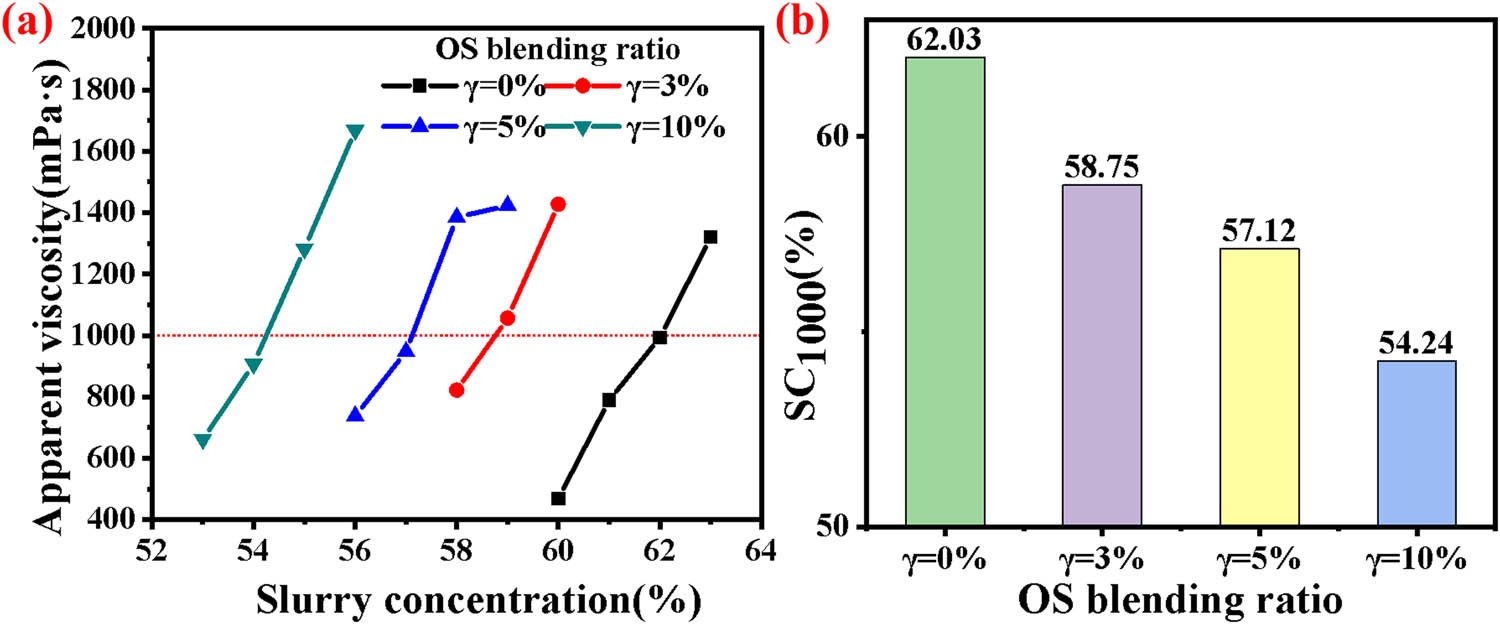

Figure 1 depicts the relationship between the η and concentration of slurry when the additive is 0.15% after blending with OS. As shown in Figure 1, it can be observed that as the concentration increases, the η of the slurry gradually rises. When the concentration increased from 60% to 63% without the addition of OS, the corresponding η increased from 468.7 to 1,320.3 mPa·s; with the addition of 3% OS, when the concentration increased from 58% to 60%, the corresponding η increased from 822.0 to 1,427.2 mPa·s; when the OS addition was 5%, with the concentration increasing from 56% to 59%, the corresponding η increased from 737.8 to 1,423.2 mPa·s; with a 10% addition of OS, when the concentration increased from 53% to 56%, the corresponding η increased from 661.8 to 1,668.2 mPa·s. This phenomenon can be attributed to two main factors. First, the increasing concentration of solid particles in the slurry leads to greater friction between these particles. Second, the decrease in the amount of free water in the slurry, which plays a lubricating role, also contributes to the rise in η.

Effect of different blending ratios of OS on (a) the apparent viscosity and (b) SC1000 of COSS.

From Figure 1, it is also evident that as the γ of OS increases, the SC1000 of COSS gradually decreases. For γ values of 0%, 3%, 5%, and 10%, the SC1000 of COSS are 62.03%, 58.75%, 57.12%, and 54.24%, respectively. The addition of OS reduces the slurry concentration. OS possesses a flocculent structure with a porous nature. These flocculent structures provide OS with a strong water-retaining capability [23], enabling it to trap a significant amount of free water within OS. The trapped water cannot flow freely and loses its lubricating and cushioning capacity for coal particles, resulting in an increase in slurry viscosity.

3.2 Effect of modification on the viscosity of OS

In order to improve the significant reduction in slurry concentration after adding OS, various modification agents are currently being used for pretreatment of OS. Three types of modification agents are chosen for the treatment of OS, including NaOH, sodium dodecylbenzene sulfonate (SDBS), and polyoxyethylene polyoxypropylene polyether (AE) modification agents.

As shown in Table 3, the modifier significantly reduces the viscosity of OS. The use of NaOH modification has the most pronounced effect. When NaOH addition amount is 10% of OS, the viscosity of OS decreases to 891.8 mPa·s. When AE addition amount is 7%, the viscosity of OS decreases to 1,210.2 mPa·s, and further increasing the addition amount does not lead to a significant decrease in viscosity. The effect of SDBS modification is slightly less effective. When SDBS addition amount is 5%, the viscosity of OS decreases to a turning point, and the viscosity is 1,282.2 mPa·s. This is because NaOH destroys the floc structure on the surface of the OS, weakens the binding ability of the OS to water, increases the free water and decreases the viscosity. SDBS and AE are surfactants, which are adsorbed on the surface of OS particles due to electrostatic attraction or van der Waals force, reducing the intermolecular friction between the dispersed phases and lowering the viscosity of the system. Therefore, the optimal addition amounts for NaOH, SDBS, and AE are 10%, 5%, and 7%, respectively.

Viscosity of OS after modification with different addition amount (mPa·s)

| Addition amount (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modification agents | 0 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 10 |

| NaOH | >1,800 | 1,646.7 | 1,408.7 | 1,213.3 | 891.8 |

| SDBS | >1,800 | 1,487.3 | 1,282.2 | 1,280.7 | 1,278.9 |

| AE | >1,800 | 1,669.7 | 1,456.0 | 1,210.2 | 1,209.2 |

3.3 Influence of blending modified OS with the concentration of COSS

OS treated with 10% NaOH, 5% SDBS, and 7% AE, respectively, was subsequently used for blending and preparing COSS.

As indicated in Figures 1 and 2, compared to blending untreated OS, when NaOH-modified OS is blended at 3%, 5%, and 10%, the corresponding SC1000 of COSS increases by 1.42%, 1.74%, and 2.50%, respectively; when SDBS-modified OS is blended at 3%, 5%, and 10%, the corresponding SC1000 of COSS increases by 1.06%, 1.98%, and 3.98%, respectively. While AE-modified OS is blended at 3% and 5%, the corresponding SC1000 of COSS decreases by 0.84% and 0.86%, respectively, and at a blending ratio of 10%, the corresponding SC1000 increases by 1.03%.

Apparent viscosity and SC1000 of COSS with different modified OS blending ratios. (a) Apparent viscosity of slurries after blending different proportions of OS modified with NaOH; (b) apparent viscosity of slurries after blending different proportions of OS modified with SDBS; (c) apparent viscosity of slurries after blending different proportions of OS modified with AE; and (d) SC1000 of COSS with different modified OS blending ratios.

It is evident that the NaOH and SDBS modifiers have enhanced SC1000 of COSS, while the effect of the AE modifier on SC1000 is less pronounced. This is because NaOH and SDBS modifiers disrupt the hydrophilic polar functional groups within OS, breaking down the flocculated structure and weakening adsorption capacity of water of OS. Additionally, SDBS serving as a dispersant for CWS can improve slurry concentration. When using AE for modification, OS still contains flocculated structures, leading to a deterioration in slurry concentration. However, when the OS modified by AE is added in larger quantities, the excess AE adsorbed onto the coal particles, preventing the coal particles from aggregating into lumps, which increased the slurry concentration slightly.

3.4 Influence of blending modified OS on the static stability of COSS

OS treated with 10% NaOH, 5% SDBS, and 7% AE, respectively, was subsequently used for blending and preparing COSS, with an addition of modified OS at 10% of the slurry base.

From Table 4, it can be observed that, compared to the addition of untreated OS, the drainage rate of the slurry prepared using NaOH-modified OS slightly increases, and the stability of the slurry slightly decreases. However, when treated with SDBS and AE, the drainage rate of the CWS increases, and the stability decreases. At a slurry concentration of 56%, the untreated slurry has a drainage rate of 0.95%, indicating a state of soft precipitation. In contrast, the drainage rates for the NaOH, SDBS, and AE-modified slurries are 1.36%, 4.15%, and 2.14%, respectively, with states of partial soft precipitation, hard precipitation, and partial soft precipitation. This is attributed to the modification agents disrupting the polar functional groups of the OS, simultaneously destroying the floc-like structure exhibited by the OS. The spatial network structure in the slurry decreases, leading to a deterioration in the stability of the slurry.

Static stability of COSS after modification with different modification agents

| Modification agents | Slurry concentration (%) | Static stability | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drainage rate (%) | Precipitation behavior | ||

| No modification agent | 54 | 1.34 | Partial soft precipitation |

| 55 | 1.03 | Soft precipitation | |

| 56 | 0.95 | Soft precipitation | |

| NaOH | 55 | 1.78 | Partial soft precipitation |

| 56 | 1.16 | Partial soft precipitation | |

| 57 | 0.96 | Partial hard precipitation | |

| SDBS | 56 | 4.35 | Hard precipitation |

| 57 | 3.96 | Partial hard precipitation | |

| 58 | 2.63 | Partial hard precipitation | |

| AE | 54 | 3.20 | Partial hard precipitation |

| 55 | 2.88 | Partial hard precipitation | |

| 56 | 1.34 | Partial soft precipitation | |

3.5 Various characterizations of the influence of modification on COSS

In this section, SEM, zeta potential, FT-IR, and contact angle are used to study the change after blending modified OS with COSS, with an addition of modified OS at 10% of the slurry base.

SEM is utilized to observe the morphological changes of COSS after treatment with different modifiers. As shown in Figure 3(a), after NaOH modification, OS is decomposed into small particles, and the floccules attached to the surface of coal particles disappear [26]. This occurs due to the oxidation of the polar functional groups in OS, preventing them from forming aggregates through hydrogen bonding. When blended with SDBS-modified OS, there is a reduction in the flocculent material adhering to coal particle surfaces. This is primarily due to the decreased hydroxyl groups in OS after SDBS treatment. Although there is a reduction in the flocculent material adhering to coal particle surfaces when blended with AE-modified OS, some block-like structures still attach to coal particles. This is primarily due to the emulsifying action of AE, which removes oil from OS and causes them to break apart. Therefore, the use of AE modification can only slightly increase the slurry concentration.

Various characterizations of COSS after blending different modified OS. (a) SEM images of different COSS; (b) zeta potential of different COSS; (c) FT-IR spectra of different COSS; and (d) contact angles of different COSS.

Zeta potential value is a primary indicator of the stability of a mixed system. The presence of like charges on the particles of OS leads to mutual repulsion, resulting in an electrostatic repulsion effect that enhances the stability of COSS. As indicated by Figure 3(b), the absolute values of zeta potential decrease after treatment with the three modifiers. The NaOH-modified OS exhibits the most significant reduction in zeta potential, followed by the AE-modified OS, and finally, the SDBS-modified OS. This suggests that the modified treatment results in a decrease in surface charge on COSS, leading to enhance the destabilization and dewatering capability of COSS.

FT-IR spectroscopy is employed to investigate the changes in surface functional groups of COSS after blending with modified OS. As shown in Figure 3(c), compared to blending with unmodified OS, the absorption peak of –OH (hydroxyl) at 3,430 cm−1 decreases when blending with NaOH-modified and SDBS-modified OS [21], with a more significant decrease observed in NaOH-modified OS. Additionally, all three modification methods weaken the absorption peak of C–O (phenol, alcohol) at 1,100 cm−1 in the slurry. The reduction in the absorption peak at 3,430 cm−1 is attributed to the destruction of carboxyl and hydroxyl functional groups in OS after NaOH and SDBS modification. The decrease in the C–O (phenol, alcohol) absorption peak at 1,100 cm−1 is due to the hindrance of the aggregation of polar functional groups on the coal particle surface, making it easier for the phenolic and alcoholic functional groups on the coal particle surface to combine with the polar groups on OS, thereby reducing the C–O content on COSS surface. The reduction in –OH (hydroxyl) and C–O (phenol, alcohol) functional groups results in more free water in the slurry, leading to an increase in slurry concentration.

Contact angle is used to assess the changes in hydrophilicity of COSS after modification. From Figure 3(d), it can be observed that, compared to untreated COSS, all three modification methods significantly reduce the contact angle between COSS and water. The contact angles after modification with NaOH, SDBS, and AE are 66.8°, 55.7°, and 57.9°, respectively, with the most significant reduction observed in the case of SDBS modification. NaOH modification increases the pH value of COSS. In an alkaline environment, the hydrophilic end of the naphthalene-based additive adsorbed on coal particles interacts with the hydrophilic end of the additive in the liquid phase. This enhances the adsorption performance of coal particles, increases its hydrophilicity, and reduces the contact angle of the slurry. The contact angle decreases after SDBS and AE modifications because both anionic and non-ionic modifying agents are adsorbed onto the coal particle surface. Additionally, the hydrophilic end of the surfactant faces outward, enhancing the wetting properties of coal particles and reducing the contact angle. The decrease in contact angle indicates an enhancement in the wetting properties of coal particle surfaces, promoting the formation of a hydration film on coal particles, leading to more uniform dispersion in water, thereby reducing η and increasing slurry concentration.

3.6 Effect of blending modified OS on combustion behavior

By employing CWS to treat OS, it is essential not only to consider the impact of blending modified OS on the performance of slurry but also to investigate the effects of blending modified OS on the combustion performance of COSS. Therefore, utilizing thermal analysis techniques, combustion characteristic parameters are calculated, and kinetic analysis is conducted to explore the influence of blending modified OS on the combustion performance. The experiment involves the addition of modified OS at 10% of the slurry base.

As shown in Figure 4(a) and (b), three stages can be observed in the OS combustion profile. The first stage (<200°C) involves rapid weight loss of OS, primarily due to the evaporation of water and some low boiling point oily components. The second stage (200–520°C) involves further weight loss, mainly attributed to the volatilization of high boiling point oily components and the sustained combustion of organic components [20,21]. Combining with the Differential thermal gravimetry (DTG) curve, the maximum weight loss rate in this stage is determined to be 0.33%·min⁻¹. The third process (>570°C) results in a weight loss of approximately 2.70%, primarily associated with the decomposition of residual ash in OS.

Thermogravimetric (TG) and DTG curves of OS, dehydrated OS and COSS with different modification of OS. (a) TG-DTG curve of OS; (b) TG-DTG curve of dehydrated OS; (c) TG curve of different COSS; and (d) DTG curve of different COSS.

The combustion profiles at a heating rate of 10°C·min⁻¹ are described in Figure 4(c) and (d), two stages can be observed in the COSS combustion profile. The first stage occurs around 100°C, involving the evaporation of moisture from both coal and OS. Compared to COSS with unmodified OS, the DTG curve of COSS with modified OS shifts to the left around 100°C, and the weight loss rate of the slurry with SDBS and AE modification increases in this stage. This indicates that the modification process promotes the evaporation of moisture in COSS. The second stage goes from 260°C to 700°C, encompassing the volatilization of components, as well as the combustion of volatiles, coke, and fixed carbon. Compared to adding unmodified OS, the addition of OS modified with NaOH and SDBS shifts the TG curve to the left. Conversely, adding OS modified with AE shifts the corresponding TG curve to the right.

Through TG-DTG curves, only qualitative evaluation of the combustion characteristics of slurry can be achieved. To further analyze the impact of blending modified OS on the combustion performance, it is necessary to calculate characteristic points of the TG-DTG curves. Table 5 lists the combustion parameters of different COSS, and T i is the ignition temperature (K), T h is the burnout temperature (K), T max is the temperature at the maximum weight loss rate (K), K max is the maximum weight loss rate (%·min−1), K mean is the average weight loss rate (%·min−1).

Combustion parameters of COSS with different modification OS

| Samples | T i (K) | T h (K) | T max (K) | K max (%·min−1) | K mean (%·min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COSS | 606.25 | 876.95 | 729.55 | 1.98 | 1.67 |

| NaOH-COSS | 604.65 | 834.55 | 651.85 | 2.35 | 1.95 |

| SDBS-COSS | 600.65 | 842.25 | 678.25 | 2.31 | 1.90 |

| AE-COSS | 634.25 | 896.85 | 738.35 | 2.05 | 1.71 |

According to the data in Table 5, blending OS modified by NaOH and SDBS reduces T i by 1.6 and 5.6 K, and T h by 42.4 and 34.7 K, indicating that the NaOH and SDBS modification promotes the ignition and burnout behavior of COSS, while adding OS modified by AE, T i and T h increase by 28.0 and 19.9 K, indicating that the AE modification hinders the ignition and burnout behavior of the slurry. The utilization of NaOH, SDBS, and AE modifications enhanced the K max and K mean of the slurry, with K max increasing by 0.37, 0.33, and 0.07%·min−1, and K mean increasing by 0.28, 0.23, and 0.04%·min−1, respectively. This indicates that NaOH and SDBS modifications enhance the combustion process of COSS, while AE modification has little effect on the combustion process.

3.7 Combustion kinetic analysis of blending modified OS

Dynamic analysis allows for a more comprehensive assessment of the combustion performance of COSS. Using the Coats-Redfern integral method, the kinetic parameters evaluating the combustion performance are calculated. The impact of blending modified OS on the combustion performance of COSS is analyzed through dynamic parameter.

The Coats-Redfern integral equation is shown below:

where k 0 is the frequency factor (min⁻¹), E is the activation energy (kJ·mol−1), R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J·(mol·K)−1), T is the reaction temperature (K), n is the reaction order, α is the coal conversion rate (%), and β is the heating rate (K·min−1).

Let

Based on the thermogravimetric data, Y is calculated from the equation, and a plot is made against X. By fitting the curve, intercept and slope are further determined to obtain frequency factor (k 0) and activation energy (E).

As indicated by Figure 5, compared to blend unmodified OS, the E of combustion for COSS with NaOH and SDBS modification significantly decreased, reducing by 7.95 and 6.62 kJ·mol−1, respectively, and the k 0 showed a noticeable increase, rising by 345.06 and 583.82 min−1, indicating that NaOH and SDBS modification reduced the energy required for slurry combustion, enhancing the combustion performance of COSS. It can be observed that when blended with NaOH and SDBS-modified OS, the Na elements on the slurry surface are significantly higher compared to the unmodified OS. The Na elements adhere to the surface of coal particles, forming activation centers during the combustion, enhancing the combustion performance of the slurry [29]. In contrast, the slurry with AE modification showed a less significant increase in the activation energy of combustion, without a clear improvement in combustion performance. T i and T h decrease, K mean increases, E decreases, the reaction is shifted to the low temperature region, and the average fuel burning rate increases, indicating an increase in the combustion efficiency in boiler furnaces.

Combustion kinetic parameters of COSS with different modification of OS and Na.

4 Conclusion

The addition of OS reduces the SC1000 of the slurry. Compared to the slurry without OS, when blending 10% OS, the SC1000 decreases from 62.03% to 54.24%. NaOH, SDBS, and AE exhibit good viscosity reduction effects, with optimal addition amounts of 10%, 5%, and 7%, respectively. Compared to the slurry with 10% untreated OS, when blending 10% OS modified with NaOH, SDBS, and AE, the SC1000 of the slurry can be increased to 56.74%, 57.32%, and 55.27%, respectively. The use of NaOH and SDBS for modification disrupts some polar oxygen-containing functional groups in OS and break down the flocculent structure on the surface of COSS. When using AE for treatment, although it can break down some flocculent structures, it may form localized agglomerates. Modification also reduces the contact angle between COSS and water, with contact angles decreasing from 88.9° to 66.8°, 55.7°, and 57.9° when using NaOH, SDBS, and AE modification.

The drainage rates for the NaOH-, SDBS-, and AE-modified slurries are increased. Modification with NaOH, SDBS, and AE, the zeta potential of COSS changes from −23.91 to −17.33 mV, −21.21, and −20.13 mV, respectively. It is shown that NaOH, SDBS, and AE modifications can all reduce the surface charge of COSS, disrupting its stability.

In comparison to blending 10% OS, when blending OS modified with NaOH and SDBS, the corresponding T i decrease from 606.25 to 604.65 K and 600.65 K, and the corresponding T h decrease from 876.95 to 834.55 K and 842.25 K, respectively. However, after blending AE-modified OS, the corresponding T i and T h both increased. When blended with OS modified by NaOH and SDBS, the corresponding E decreased from 51.86 to 43.91 and 45.24 kJ·mol−1, and k 0 increased from 600.37 to 945.43 and 1,184.19 min−1, respectively. However, after blending AE-modified OS, the E of the slurry increased less, and there was no significant improvement in the combustion performance of COSS.

-

Funding information: The completion of this work and related results received support from the Scientific Research Foundation for the Introduction of Talent, Anhui University of Science and Technology (Grant No. 2023yjrc90) and the Open Research Fund Program of Engineering Technology Research Center of Coal Resources Comprehensive Utilization, Anhui Province, Anhui University of Science and Technology (Grant No. MTYJZX202203).

-

Author contributions: Jianyang Chen: conceptualization, methodology, and writing. Hanxu Li: conceptualization and methodology. Shuai Zhao: data curation. Dong Li: supervision. Ningnig Wang: data curation. Shuhao Shen: supervision. Lirui Mao: conceptualization.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Su HF, Lin JF, Wang QY. A clean production process on oily sludge with a novel collaborative process via integrating multiple approaches. J Clean Prod. 2021;322:128983.10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128983Search in Google Scholar

[2] Li D, Liu J, Wang S, Cheng J. Study on coal water slurries prepared from coal chemical wastewater and their industrial application. Appl energy. 2020;268:114976.10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.114976Search in Google Scholar

[3] Makarov AS, Boruk SD, Egurnov AI, Dimitryuk TN, Klishchenko RE. Utilization of industrial wastewater in production of coal-water fuel. J Water Chem Technol. 2014;36:180–3.10.3103/S1063455X14040055Search in Google Scholar

[4] Wang R, Liu J, Hu Y, Zhou J, Cen K. Ultrasonic sludge disintegration for improving the co-slurrying properties of municipal waste sludge and coal. Fuel Process Technol. 2014;125:94–105.10.1016/j.fuproc.2014.03.014Search in Google Scholar

[5] Wen X, Xie Y, Jiang L, Li Y, Ge T. Distribution, risk assessment and stabilization of heavy metals in supercritical water gasification of oily sludge. Process Saf Environ Prot. 2022;168:591–600.10.1016/j.psep.2022.09.068Search in Google Scholar

[6] Zhen X, Li S, Jiao R, Wu W, Dong T, Liu J. Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity. Green Process Synth. 2023;12(1):20230072.10.1515/gps-2023-0072Search in Google Scholar

[7] Nunes LJR. Potential of coal–water slurries as an alternative fuel source during the transition period for the decarbonization of energy production: A review. Appl Sci. 2020;10(7):2470.10.3390/app10072470Search in Google Scholar

[8] Guo Q, Zhang Z, He Q, Gong Y, Huang Y, Yu G. Characteristics of high-carbon-content slag and utilization for coal-water slurry preparation. Energy Fuels. 2020;34(11):14058–64.10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c02882Search in Google Scholar

[9] Zhang Y, Xu Z, Tu Y, Wang J, Li J. Study on properties of coal-sludge-slurry prepared by sludge from coal chemical industry. Powder Technol. 2020;366:552–9.10.1016/j.powtec.2020.03.005Search in Google Scholar

[10] Zhou M, Yang D, Qiu X. Influence of dispersant on bound water content in coal–water slurry and its quantitative determination. Energy Convers Manag. 2008;49(11):3063–8.10.1016/j.enconman.2008.06.002Search in Google Scholar

[11] Zhou M, Yang D, Qiu X. Effect of the sodium lignosulphonate from different material on rheological behavior of coal water slurry. J Chem Eng Chin Universities. 2007;21(3):386.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Nadziakiewicz J, Kozioł M. Co-combustion of sludge with coal. Appl Energy. 2003;75(3–4):239–48.10.1016/S0306-2619(03)00037-0Search in Google Scholar

[13] Folgueras MB, Diaz RM, Xiberta J, Garcia MP, Pis JJ. Influence of sewage sludge addition on coal ash fusion temperatures. Energy Fuels. 2005;19(6):2562–70.10.1021/ef058005aSearch in Google Scholar

[14] Behari M, Mohanty AM, Das D. Insights into the transport phenomena of iron ore particles by utilizing extracted Bio-surfactant from Acacia concinna (Willd.) Dc. J Mol Liq. 2023;382:121974.10.1016/j.molliq.2023.121974Search in Google Scholar

[15] Behari M, Das D, Mohanty AM. Influence of surfactant for stabilization and pipeline transportation of iron ore water slurry: A review. ACS Omega. 2022;7(33):28708–22.10.1021/acsomega.2c02534Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Wang R, Liu J, Yu Y, Hu Y, Zhou J, Cen K. The slurrying properties of coal water slurries containing raw sewage sludge. Energy Fuels. 2011;25(2):747–52.10.1021/ef101409hSearch in Google Scholar

[17] Xu M, Liu H, Zhao H, Li W. Effect of oily sludge on the rheological characteristics of coke-water slurry. Fuel. 2014;116:261–6.10.1016/j.fuel.2013.07.114Search in Google Scholar

[18] Piskunov M, Romanov D, Strizhak P. Stability and rheology of carbon-containing composite liquid fuels under subambient temperatures. Energy. 2023;278:127912.10.1016/j.energy.2023.127912Search in Google Scholar

[19] Wang Y, Zou L, Shao H, Bai Y, Liu Y, Zhao Q, et al. Co-combustion of high alkali coal with municipal sludge: Thermal behaviour, kinetic analysis, and micro characteristic. Sci Total Environ. 2022;838:156489.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156489Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Fu B, Liu G, Mian MM, Zhou C, Sun M, Wu D, et al. Co-combustion of industrial coal slurry and sewage sludge: Thermochemical and emission behavior of heavy metals. Chemosphere. 2019;233:440–51.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.05.256Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Wang Y, Jia L, Guo J, Wang B, Zhang L, Xiang J, et al. Thermogravimetric analysis of co-combustion between municipal sewage sludge and coal slime: Combustion characteristics, interaction and kinetics. Thermochim Acta. 2021;706:179056.10.1016/j.tca.2021.179056Search in Google Scholar

[22] Li F, Liu X, Zhao C, Yang Z, Fan H, Han G, et al. Effects of sludge on the ash fusion behaviors of high ash-fusion-temperature coal and its ash viscosity predication. J Energy Inst. 2023;108:101254.10.1016/j.joei.2023.101254Search in Google Scholar

[23] He Q, Xie D, Xu R, Wang T, Hu B. The utilization of sewage sludge by blending with coal water slurry. Fuel. 2015;159:40–4.10.1016/j.fuel.2015.06.071Search in Google Scholar

[24] Xu M, Zhang J, Liu H, Zhao H, Li W. The resource utilization of oily sludge by co-gasification with coal. Fuel. 2014;126:55–61.10.1016/j.fuel.2014.02.048Search in Google Scholar

[25] Liu J, Wang R, Hu Y, Zhou J, Cen K. Improving the properties of slurry fuel preparation to recycle municipal sewage sludge by alkaline pretreatment. Energy Fuels. 2013;27(6):2883–9.10.1021/ef301986dSearch in Google Scholar

[26] Chu R, Li Y, Meng X, Fan L, Wu G, Li X, et al. Research on the slurrying performance of coal and alkali-modified sludge. Fuel. 2021;294:120548.10.1016/j.fuel.2021.120548Search in Google Scholar

[27] Jiang X, Zhou Y, Meng X, Wu G, Miao Z, Sun F, et al. The effect of inorganic salt modification of sludge on the performance of sludge-coal water slurry. Colloids Surf A: Physicochem Eng Asp. 2023;664:131146.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2023.131146Search in Google Scholar

[28] Liu J, Wang S, Li N, Wang Y, Li D, Cen K. Effects of metal ions in organic wastewater on coal water slurry and dispersant properties. Energy Fuels. 2019;33(8):7110–7.10.1021/acs.energyfuels.9b01146Search in Google Scholar

[29] Mao L, Li H, Zhang Y, Wu C. Preparing coal water slurry from BDO tar to achieve resource utilization: combustion process of BDO tar-coal water slurry. Energy Fuels. 2019;33(10):10297–306.10.1021/acs.energyfuels.9b02479Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”