Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

-

Badr Alzahrani

, Abdullah Alsrhani

Abstract

In the present work, manganese–copper co-infused nickel oxide nanoparticles (MnCu co-doped NiO NPs) were formulated via a green process using Carica papaya extract. The MnCu co-doped NiO NPs were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD), UV–Vis, Fourier transform infrared, field emission scanning electron microscope, energy dispersive X-ray analysis, and photoluminescence (PL) spectrum. The XRD pattern demonstrated that synthesized MnCu co-doped NiO NPs exhibit cubic structure. On the PL spectrum, various surface defects were identified. MnCu co-doped NiO NPs exhibited ferromagnetic properties at 37°C. The antimicrobial activity of green synthesis MnCu co-doped NiO NPs against human pathogens (Escherichia coli, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Bacillus megaterium, Bacillus subtilis, Shigella dysenteriae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) and Candida albicans as fungal strains were demonstrated. The MnCu co-doped NiO NPs treatment considerably reduced MDA-MB-231 cell viability while not disturbing HBL-100 cell viability. Different fluorescent staining analyses revealed that MnCu co-doped NiO NPs induced nuclear and mitochondrial damage to improve free radical production, altering mitochondrial membrane protein potential, which led to apoptotic cell death in MDA-MB-231 cells. The MnCu co-doped NiO NP treatment enhanced pro-apoptotic protein expression and inhibited the cell cycle at the S phase in MDA-MB-231 cells. This makes it easy, cheap, and environmentally friendly to make MnCu co-doped NiO NPs using C. papaya extract, which has excellent antimicrobial properties.

1 Introduction

Many biomedical researchers are interested in nanoparticle (NP)-based material; because of their ability to combat health-threatening pathogens, NPs that can be used as antimicrobial agents are extremely important [1]. Several nanomaterials have been found to have antimicrobial properties that can be used to make medical products like wound dressings, biosensors, drug carriers, and so on.

In addition, NPs are extremely small particles. Higher surface area-to-volume ratio results in remarkable variations in their properties, including biological, catalytic, mechanical, and electroconductivity. These characteristics place metal oxide NPs on the spectra of various potential applications, including antibacterial and anticancer properties [2]. In addition, nickel oxide nanoparticles (NiO NPs) have unique catalytic, electronic, and magnetic properties. NiO is a transition metal (TM) oxide with a cubic lattice that is a p-type semiconductor and has a bandgap between 3.6 and 4.0 eV. Furthermore, NiO NPs have antibacterial and anticancer allowing them to be used in various applications [3]. As the material gets smaller in size and the band gap closes, its optical and biocidal properties change, which makes it appropriate for novel medical uses. The doping of impurity atoms is the extensively adopted strategy for transforming the biocidal properties of a semiconductor. Abdur Rahman et al. [4] reported that Ce-doped NiO NPs exhibited the maximum antibacterial effects than NiO NPs when tested by both G+ and G− bacteria [4]. Cu-doped NiO NPs influenced a more significant antibacterial property than NiO and erythromycin. CNC/NiO composite has a potential antimicrobial effect against Escherichia coli bacteria, which is enhanced by Cu doping and enhances bacterial activity [5].

Breast cancer is a widespread and high-risk female malignancy around the world. The incidence of breast cancer rapidly increases every year, and onset typically occurs at a younger age. Presently, breast cancer is the major cause of cancer-associated mortality than lung cancer worldwide; by 2020, it is expected to account for 11.7% of all new cancer incidences [6]. Despite recent developments in the treatment of breast cancer, metastasis, postoperative tumor recurrence, and resistance to therapies have led to poor 5-year survival rates, which gravely endanger the patients [7]. There are several problems associated with the standard treatment of cancers, including side effects, high costs, and resistance to therapies. It is necessary to develop a reliable drug delivery method to overcome these constraints. As a cutting-edge therapeutic approach, targeted therapy has the benefits of excellent specificity, exceptional healing outcomes, and low adverse effects [8]. As a result, targeted treatment has gained acceptance as a potent and focused way to eliminate tumor cells, and it is steadily gaining popularity in the field of cancer therapy.

Cu and Mn monometallic NPs have exhibited remarkable anticancer activity against a variety of cancer cell lines in numerous studies. Copper NPs, for instance, have been reported to induce apoptosis and inhibit the proliferation of cancer cells through mechanisms that involve oxidative stress and DNA damage [9]. Similarly, manganese NPs have demonstrated potential in cancer therapy by promoting the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within cancer cells, leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [10]. Furthermore, the unique physicochemical properties of these NPs, such as their size, shape, and surface modifications, can be tailored to enhance their specificity for cancer cells while minimizing their impact on healthy tissues [11]. These findings underscore the potential of Cu and Mn monometallic NPs as promising candidates for targeted anticancer therapy. In addition to their anticancer properties, Cu and Mn monometallic NPs have demonstrated notable antimicrobial activity against a wide range of pathogenic microorganisms. Copper NPs, for example, have been found to exhibit potent antibacterial activity by disrupting the cell membranes and interfering with the vital cellular processes of bacteria [12]. Similarly, manganese NPs have shown promise as antimicrobial agents, particularly in the context of combating drug-resistant bacterial strains [13].

Herein, we aim to design a simple, low-cost, eco-friendly, and one-pot green method approach for preparing manganese–copper co-infused nickel oxide nanoparticles (MnCu codoped NiO NPs) by utilizing the Carica papaya leaf extract. The papaya (C. papaya Linn.) is a member of the Caricaceae family and is well known for its therapeutic and dietary benefits all over the world [14,15]. C. papaya contains various active phytocomponents responsible for its therapeutic activity. In addition, it regulates the papaya leaf s antimicrobial, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, and antiviral effects [16,17]. In the current work, we made MnCu co-doped NiO NPs using C. papaya leaf extract and a green process. We also looked at their structure, morphology, optical, magnetic, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Nickel(ii) nitrate hexahydrate (AR), copper(ii) nitrate hexahydrate (AR), manganese(ii) nitrate (AR), and NaOH (AR) from Sigma Aldrich (Missouri, USA) were used. Sigma Aldrich provided all the chemicals used in the study with analytical grades.

2.2 Preparation of leaf extract

C. papaya fresh leaves were sliced into pieces and rinsed twice with tap water and deionized water to eliminate the unwanted foreign particles. Ten grams of C. papaya leaf were boiled with 100 mL of deionized water in a 250 mL beaker and stirred with a magnetic stirrer for about an hour at 80°C. The colour of the aqueous solution changed from watery to light greenish. The solution was cooled to 37°C before being filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper.

2.3 Preparation of manganese copper codoped nickel oxide NPs

To obtain the MnCu co-doped NiO NPs sample, 0.0094 M of nickel nitrate, 0.003 M of manganese nitrate, and 0.003 M of copper nitrate solute were mixed with 100 mL of extract. The suspension was stirred for 6 h at 37°C. The resulting suspension was cooled to 37°C before being centrifuged for 15 min at 8,000 rpm. The nanopowder was dehydrated for 2 h at 120°C. The MnCu co-doped NiO NPs were heated in the air for 5 h before being used for the downstream experiments.

2.4 Characterization studies

X-ray diffraction (XRD) (X’PERT PRO PANalyti-cal) was used to characterize the MnCu co-doped NiO sample. Carl Zeiss Ultra-55 FESEM (field emission scanning electron microscope) with energy dispersive X-ray analysis: EDAX (model: Inca) was used to examine the sample. A Perkin-Elmer spectrometer was used to capture Fourier transform infrared (FT-infrared [IR]) spectra in the 400–4,000 cm−1 range. A luminescence spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer LS-5513) and a xenon lamp with an excitation wavelength of 325 nm were used to measure the photoluminescence spectrum at 37°C. A vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) (Lakeshore mini VSM-3639) was used to examine the magnetic properties.

2.5 Antimicrobial effects

The study tested the antimicrobial properties of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs against various bacterial (E. coli, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Bacillus megaterium, Bacillus subtilis, Shigella dysenteriae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) and fungal (Candida albicans) strains using a well diffusion process. The microorganisms were obtained from the Institute of Microbial Technology in Chandigarh, India. The bacterial strains were inoculated using a sterile spread plate method, followed by a DMSO solution diluted with different dose levels of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs (1, 1.5, and 2 mg·mL−1). The treated Petri dishes were observed after 24 h in the zone of inhibition. As a positive control, the standard antibiotic amoxicillin (1 mg·mL−1) was used. The antifungal activity of the nanocomposites against C. albicans and growth on potato dextrose agar was also tested using the agar-well diffusion method. C. albicans was inoculated and streaked, followed by wells containing different concentrations (1, 1.5, and 2 mg·mL−1) of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs incubated under visible light for 24 h at 30°C. Amphotericin B (1 mg·mL−1) was used as a positive control.

2.6 Cell lines and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay

NCCS, Pune, India, provided human breast (MDA-MB-231) and normal HBL-100 cells. The cells were cultured in T-75 culture flasks (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with 5% carbon dioxide at 37°C in DMEM-F12 medium containing 10% FBS, 25 µg·mL−1 amphotericin, 100 U·mL−1 penicillin, and 100 U·mL−1 streptomycin until 80% confluence. MTT cytotoxicity test was done to investigate the impacts of formulated MnCu co-doped NiO NPs on the growth of MDA-MB-231 and normal HBL-100 cells. Both cells were seeded separately on the 96-well plate at 5 × 103 cell population/well and exposed to the different doses of formulated MnCu co-doped NiO NPs (1, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, and 200 µg·mL−1) for 24 h. The growth of treated cells was studied by the earlier method [18].

2.7 Dual staining

To detect the apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells exposed to the formulated MnCu co-doped NiO NPs, the AO/EB dual staining was performed. Briefly, the MnCu co-doped NiO NPs were administered to the MDA-MB-231 cells for 24 h then, cells were stained using AO/EB (100 µg·mL−1, 1:1 ratio). Finally, the fluorescent microscope was employed to investigate the cells using the EVOS-XL Core cell analysis system (ThermoFisher, Massachusetts, USA) [19].

2.8 Comet assay

The study investigated the impact of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs on nuclear DNA injury in MDA-MB-231 cells. The cells were exposed to various doses of formulated MnCu co-doped NiO NPs (IC25 and IC50 concentrations) for 24 h. The comet assay was used to assess DNA damage in the cells. A frosted micro slide was coated with normal agarose in PBS, covered with a coverslip, and placed over an ice pack for 5 min. After the gel had set, 1% low melting agarose was dissolved in the cell suspension from each cell fraction in a 1:3 ratio, and the slide was coated with this mixture. A third layer of 1% low melting agarose was applied and allowed to set. The slides were then submerged in an ice-cold lysis solution and kept at 4°C for 16 h. To prevent DNA damage from light, the procedures were carried out in low-light settings. The slides were then placed horizontally in an electrophoresis tank, and electrophoresis was performed at 0.8 V·cm−1 for 15 min. The slides were rinsed three times in neutralization buffer and gently tapped to dry. Ethidium bromide was used to stain 20 μL of nuclear DNA, and 200 cells from each treatment were digitalized. Image analysis software (CASP software) was used to assess the results, identifying the DNA content of each nucleus and assessing the degree of DNA damage [20].

2.9 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining

DAPI staining was used to examine the alterations in the cell nuclear morphology of MDA-MB-231 cells induced by MnCu co-doped NiO NPs. Briefly, the MnCu co-doped NiO NPs were treated in the cells for 24 h. Afterward, cells were rinsed with saline and DAPI (200 µg·mL−1) was loaded to the wells. Finally, nuclear damage and chromatin condensation caused by MnCu co-doped NiO NPs were recorded by the EVOS-XL Core cell analysis system [21].

2.10 JC-1 staining

The alterations in the MMP status were assessed using the fluorescent JC-1 staining technique. Briefly, the MDA-MB-231 cells were grown in a six-well plate at a population of 2 × 105 cells/well for 24 h. Later, cells were administered with IC25 and IC50 dosages of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs for 24 h. Afterward, 1 µg·mL−1 of JC-1 fluorescent dye was mixed for 20 min, and then, cells were cleansed with PBS before being investigated under an EVOS-XL Core cell imaging system [22].

2.11 Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) staining

The level of ROS generation was assayed by DCFH-DA staining. The MDA-MB-231 cells were exposed to the MnCu co-doped NiO NPs for 24 h. Afterward, cells were stained using 10 µL of DCFH-DA dye for 1 h and finally assessed using the EVOS-XL system to detect the amount of ROS accumulation in the cells [23].

2.12 Flow cytometry analysis

The proportion of apoptosis was assayed using flow cytometry. After 24 h of growth in six-well plates, cells were administered with the IC25 and IC50 dosages of formulated MnCu co-doped NiO NPs for 24 h. The FACS flow cytometer (Beckman-Coulter Life Sciences, Indianapolis, USA) was used to measure the percentage of apoptosis in the cells, and the assay was repeated three times to ensure accuracy (Abcam, USA). [24].

2.13 Cell cycle analysis

Flow cytometry was employed to determine the impact of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs on cell cycle inhibition in MDA-MB-231 cells. Briefly, after 24 h incubation of IC25 and IC50 concentrations of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs, cells were harvested at a population of 5 × 106 cells. After washing, the cells were placed in a staining solution containing 0.08 mg·mL−1 of proteinase inhibitors, 0.5 mg·mL−1 of RNase solution, and 100 µL of propidium iodide (PI) for 30 min. The DNA-related PI fluorescence was detected with a flow cytometer. MultiCycle (Phoenix Flow Systems, USA) was used to calculate the percentage of nuclei in cell cycle phases [25].

2.14 Measurement of apoptotic protein levels

The levels of apoptotic proteins including Bax, Bcl-2, Cyt-C, p53, caspase-3, -8, and -9 enzyme activities in both control and IC25 and IC50 concentrations of MnCu co-doped NiO NP-treated MDA-MB-231 cells were measured using the corresponding kits by the guidelines suggested by the manufacturer (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) [26].

2.15 Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed with SPSS to evaluate whether the differences between the groups were statistically significant.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 UV–Vis spectroscopy

The absorption spectrum analysis of MnCu co-doped NiO NP samples was conducted by dispersing approximately 5 mg of the synthesized NP samples in 30 mL of deionized water. Subsequently, the prepared NPs underwent spectral analysis, as depicted in Figure 1a. Among the observed peaks, the maximum peak was identified at 342 nm for the MnCu co-doped NiO NPs. This wavelength corresponds to the point at which the absorption of light by the NPs is most pronounced.

UV–Vis spectral absorbance (a), FT-IR spectra (b), and PL spectra (c) of synthesized MnCu codoped NiO NPs. (d) FT-IR spectra of C. papaya leaf extract.

3.2 FT-IR spectroscopy

Figure 1b reveals the IR spectrum of MnCu-codoped NiO NPs. The hydroxyl O–H peak is noted at 3,323 cm−1, which is due to the adsorbed water on NP’s surface [27]. The C–H bands were noted at 2,997 cm−1. The C═O stretching vibration of primary amines was attributed to the peak at 1,633 cm−1. The aromatics C–C stretch peaks are 1,434 cm−1. The C–O bond characteristic peaks like alcohols and carboxylic acids are noted at 1,193 cm−1. The C–N stretching amine group is located at 960, 871, and 723 cm−1. The metal-oxygen bands at 649, 555, and 475 cm−1 correspond to the Ni–O vibration of MnCu codoped NiO NPs [28]. The peaks observed in the spectrum of C. papaya extract are shown in Figure 1d. The various functional groups were observed at 668 cm−1 (oxygen stretching and bending frequency of organic groups), 1,634 cm−1 (H–O–H bending vibrations), 2,087 cm−1 (hydrogen-bonded alcohols), and 3,445 cm−1 (hydroxyl group), respectively. Thus, functional groups of responsible for the reduction of metal oxide NPs.

3.3 Photoluminescence spectral analysis

As shown in Figure 1c, the PL spectrum of MnCu-codoped NiO NPs has an exciting wavelength at 325 nm (c). The prepared NPs were observed in UV emission (near band edge) and Visible emission was observed. The wavelengths of the PL spectra were 362, 406, 482, and 525 nm, respectively. The UV emission peak at 362 nm is associated with the near band edge transition. The violet emission peak at 406 nm is caused by the energy transition of cornered electrons at Ni interstitial to the VB. The 482 nm blue emission peaks are produced by the radiative recombination of electrons from the doubly ionized Ni vacancy to the hole in the VB. The green emission peak at 525 nm in MnCu codoped NiO NPs is caused by surface defects such as interstitial oxygen trapping [29]. These surface defects, specifically oxygen vacancies, are crucial in generating ROS. These reactive species are responsible for causing damage to the internal cytoplasmic membrane. Moreover, they can lead to a gradual leakage of DNA and proteins, ultimately destroying bacteria and cancer cells.

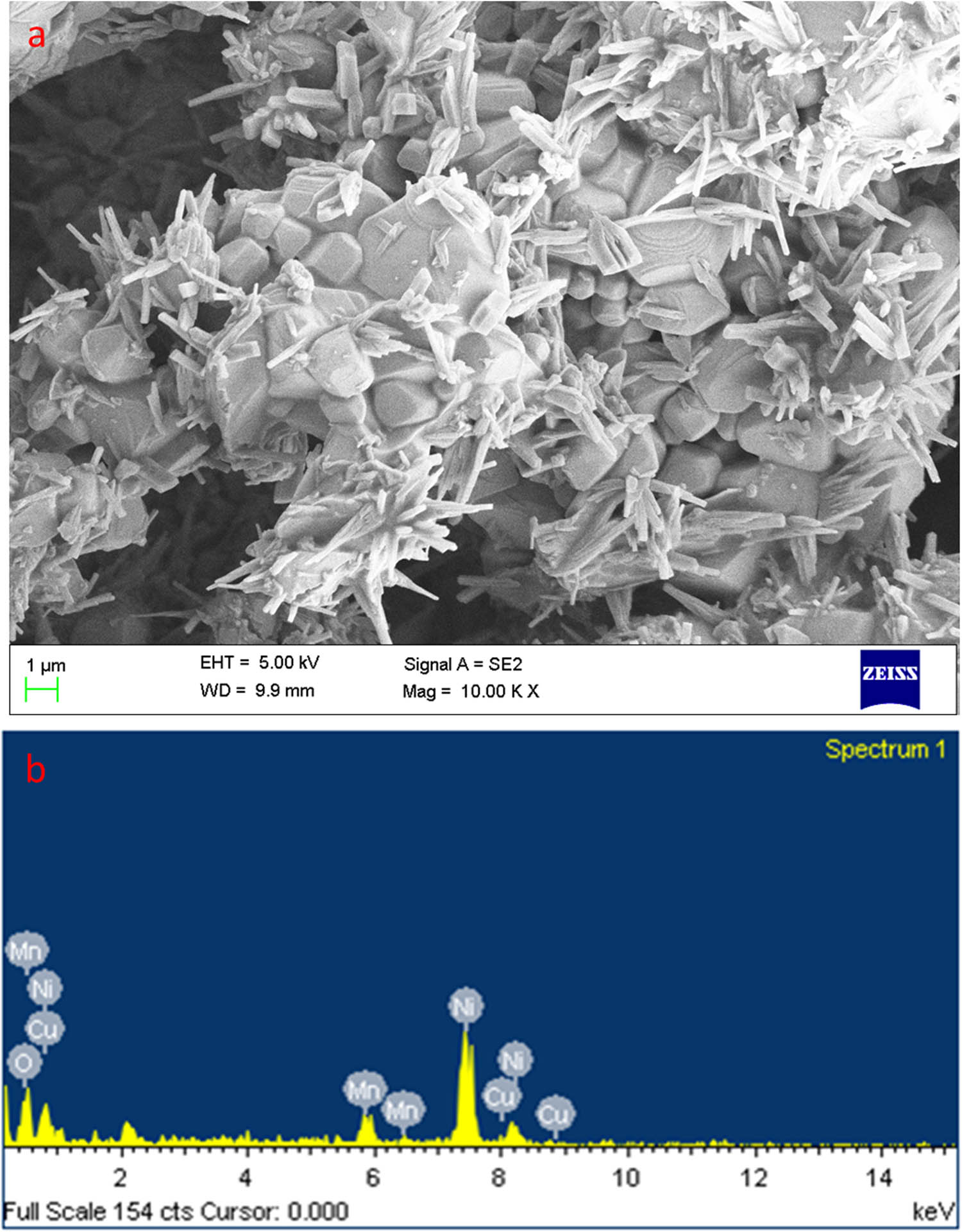

3.4 Morphology and elemental composition analysis

The FESEM image showed the topography of the MnCu co-doped NiO NPs in Figure 2a. The MnCu codoped NiO NPs are formed in a nanorod shape with smooth, uniform grain margins. The average particle size is 30–90 nm. The elemental composition of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs is identified by EDAX, as shown in Figure 2b. EDAX spectra display only Ni, Cu, Mn, and O present in the synthesized samples. There is no impurity phase observed in the MnCu co-doped NiO NPs. The atomic percentage of Ni is 36.12%, Cu is 3.84%, Mn is 5.48%, and O is 54.56% for MnCu co-doped NiO NPs. No other impurity peaks were observed in the prepared samples.

FESEM images of MnCu codoped NiO NPs: higher (a) magnifications and EDAX spectrum (b).

3.5 XRD studies

Figure 3 demonstrates XRD findings of green-synthesized MnCu co-doped NiO NPs. The XRD patterns are noted at angles (2θ) of 37.17, 43.11, 62.88, 75.48, and 79.44, corresponding to the hkl (111), (200), (220), (311), and (222) planes of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs. The present results confirm that the synthesized MnCu co-doped NiO NPs, made with cubic NiO phase (JCPDS card no. 47-1049), belong to the Fm3m space group. In the MnCu co-doped NiO NPs, no impurities phase was observed for Mn- and Cu-based elements. The estimated lattice constant values are a = 4.179 Å for MnCu co-doped NiO NPs. The crystallite size of NPs is determined by Debye Scherrer’s equation D = kλ/β(Dcos θ) [30] and found to be 47 nm for MnCu co-doped NiO NPs.

XRD analysis of the synthesized MnCu co-doped NiO NPs.

3.6 VSM studies

Figure 4 shows the VSM analysis of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs. At 37°C, MnCu co-doped NiO NPs exhibit ferromagnetic behavior. A VSM, also known as a Foner magnetometer, is a scientific instrument utilized to measure magnetic properties by employing Faraday’s Law of Induction. MnCu co-doped NiO NPs had saturation magnetization values (Ms) of 493.50 × 10−6 emu. Variations in oxygen vacancies and defects contribute to the magnetism of these characteristics [31]. The PL spectrum and green emission value were observed at 525 nm for MnCu co-doped NiO NPs in this study due to oxygen vacancies. The ferromagnetic property of TM doped with NiO NPs has been enhanced because of the super-exchange between the d states of TM. Furthermore, replacing oxygen vacancies and free charge carriers increased the ferromagnetic property because Mn2+ and Cu2+ are substituted for Ni2+ in the NiO surface matrix.

Magnetic hysteresis curve green synthesis of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs.

3.7 Antimicrobial effect

The antimicrobial effects of MnCu codoped NiO NPs were assessed against E. coli, S. pneumoniae, B. megaterium, B. subtilis, S. dysenteriae, P. aeruginosa, and fungal C. albicans strains as shown in Figure 5a. The figure shows the inhibition zones of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs and conventional antibiotics like amoxicillin (Figure 5b). The MnCu co-doped NiO NPs and amoxicillin samples exhibit antimicrobial effects on bacterial and fungal strains. To increase the dose of NPs while also increasing the antimicrobial effects. The antimicrobial mechanism of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs induces the production of ROS. ROS causes oxidative stress, which can be impaired in microbial cell membranes, lipids, proteins, and DNA. In addition, cytoplasmic contents are discharged due to ROS generation by NPS that mounts the bacterial cell membrane. The positive charge of metal cations (Cu2+, Mn2+, and Ni2+) binding to negatively charged parts of the microbial cell membrane is another possible way for nanomaterials to react with microbial strains and cause micro-pathogens to die [32,33,34].

The results of the antimicrobial activity of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs are shown. Zones of inhibition of E. coli, S. pneumoniae, B. megaterium, B. subtilis, S. dysenteriae, P. aeruginosa, and C. albicans were treated with MnCu co-doped NiO NPs (a). Each bar exhibits the triplicate values of the zone of inhibition (mm) (b).

The MnCu co-doped NiO NPs exhibited superior activity compared to the amoxicillin. Test concentrations of 150, 300, 450, 600, 750, 900, and 1,000 μg·mL−1 of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs were employed to treat E. coli, S. pneumoniae, B. megaterium, B. subtilis, S. dysenteriae, and P. aeruginosa. The following values were determined for the minimum inhibitory concentration and minimum bactericidal concentration: E. coli at 750 and 1,000 µg·mL−1, S. pneumoniae at 600 and 900 µg·mL−1, B. megaterium at 900 and 1,000 µg·mL−1, B. subtilis at 750 and 1,000 µg·mL−1, S. dysenteriae at 600 and 750 µg·mL−1, and P. aeruginosa at 400 and 60 µg·mL−1.

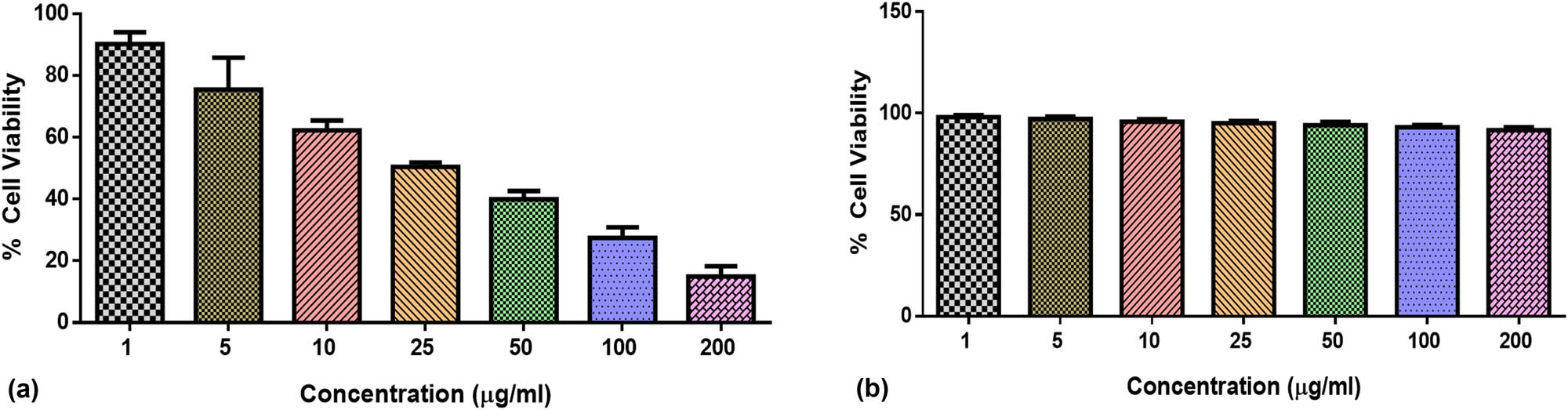

3.8 Effect of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs on the viability of MDA-MB-231 and HBL-100 cells

Cancer patients are increasingly facing therapeutic challenges due to the prevalence of multidrug resistance. Therefore, to develop effective new anticancer agents, it is necessary to study their cytotoxic levels here; we assessed the influence of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs on the MDA-MB-231 and normal HBL-100 cell viability by MTT assay. Several dosages of formulated MnCu co-doped NiO NPs (1–200 µg) remarkably diminished the MDA-MB-231 cell viability (Figure 6a). In contrast, NP treatment does not significantly affect the HBL-100 cell growth (Figure 6b). These results show that MnCu co-doped NiO NP treatment inhibits MDA-MB-231 cell viability, proving its cytotoxicity to breast cancer cells. Further fluorescence staining and biochemical assays were performed on MDA-MB-231 cells using MnCu co-doped NiO NPs, which had an IC50 of 23.97 µg·mL−1 and an IC25 of 11.98 µg·mL−1 [35].

Effect of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs at various dosages (1, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, and 200 µg·mL−1) on the viability of MDA-MB-231 cells (a) and HBL-100 (b) cells as a normal cell line.

3.9 Effect of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs on the apoptosis of MDA-MB-231 cells

Apoptosis is a cell death mechanism, which participates in the removal of damaged and/or malignant cells to maintain tissue homeostasis. The apoptosis initiation was believed as a talented technique to treat the cancers. Apoptosis is defined by certain morphological alterations in dying cells such as shrinkage, fragmentation of the nucleus, and cellular detachment. In the presence of anticancer medicines, cancer cells generally undergo apoptosis; however, normal cells may become necrotic if the treatment is harmful to normal cells. The dual (AO/EB) staining approach is useful in distinguishing between normal and apoptotic cells [36].

The results of a dual staining assay measuring the effect of MnCu co-doped NiO NP treatment on apoptotic incidences in MDA-MB-231 cells are shown in Figure 7. The control cells fluoresced green, indicating the presence of live cells, whereas the cells treated with IC25 and IC50 concentrations of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs fluoresced orange/red, indicating structural damage caused by apoptosis. These results demonstrate that MnCu co-doped NiO NPs can induce apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells.

After 24 h of treatment, apoptosis was studied in MDA-MB-231 cells using AO/EtBr staining with MnCu co-doped NiO NPs. Green cells represent live cells, yellowish red cells exhibit the early apoptosis, and red cells reveal the late apoptosis. MDA-MB-231 cells were exposed to IC25 (low dose) and IC50 (high dose) concentrations of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs, and untreated cells served as controls. Experiments performed in triplicate yielded representative images. 20× magnification (scale = 100 m).

3.10 Effect of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs on the nuclear damage in the MDA-MB-231 cells

Apoptosis plays a critical function in ensuring appropriate tissue homeostasis. One of the most prominent features of tumor development is the deregulation of apoptotic pathways [37]. Here, we used a comet assay to examine the alterations in apoptotic cell nuclear damage in the MDA-MB-231 cells.

As revealed in Figure 8, the comet assay confirmed that formulated MnCu co-doped NiO NPs caused nuclear damage in MDA-MB-231 cells. Control cells show no evidence of nuclear damage by not forming tails. Clear tail development was only seen in cells administered with IC25 and IC50 concentrations of formulated MnCu co-doped NiO NPs, indicating that NPs promoted nuclear destruction in the MDA-MB-231 cells.

Comet assay for MnCu co-doped NiO NPs treated MDA-MB-231 cells showed detectable comet tails, indicative of DNA damage. MDA-MB-231 cells were exposed to IC25 (low dose) and IC50 (high dose) concentrations of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs, and untreated cells served as controls. Representative images are obtained from experiments done in triplicates. Magnification: 20× (scale = 100 µm).

3.11 Effect of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs on the apoptotic cell nuclear morphology in the MDA-MB-231 cells

Cells can commit suicide by a process called apoptosis, which can be initiated by signals from the intrinsic or extrinsic signaling pathways. Based on its biochemical characteristics, apoptosis is defined by chromatin aggregation, nuclear damage, mRNA degradation, and the creation of apoptotic bodies [38]. Excessive apoptosis causes atrophy, whereas insufficient apoptosis causes excessive cell growth, which is seen in malignancies. Figure 9 displays the results of a DAPI staining on the effect of formulated MnCu co-doped NiO NPs on the apoptotic nuclear morphology of MDA-MB-231 cells. The lack of apoptotic nuclear changes in the control cells was indicated by decreased blue fluorescence. In contrast, cells treated with MnCu co-doped NiO NPs at concentrations of IC25 and IC50 concentrations showed enhanced blue fluorescence, indicative of dramatic nuclear alterations due to apoptosis and cell death.

DAPI nuclear staining was done to investigate apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells after 24 h of exposure to MnCu co-doped NiO NPs. MDA-MB-231 cells were administered with IC25 (low dose) and IC50 (high dose) concentrations of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs, and untreated cells served as controls. Representative images are obtained from experiments done in triplicates. Magnification: 20× (scale = 100 µm).

3.12 Effect of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs on the MMP level in the MDA-MB-231 cells

Using JC-1 staining, the influence of MnCu co-doped NiO NP treatment on the changes in MMP level of MDA-MB-231 cells was assessed. In the control, as shown in Figure 10, the JC-1 fluoresces red, indicating the presence of intact functional MMP. In contrast, cells exposed to the IC25 and IC50 concentration of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs for 24 h produced green fluorescence with pale orange/red spots when stained with JC-1, which indicates the reduction of MMP, suggesting that MnCu co-doped NiO NPs inhibited the mitochondrial function in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 10). It was well established that early apoptosis is accompanied by a reduction in MMP levels [39].

In MDA-MB-231 cells treated for 24 h with MnCu co-doped NiO NPs, MMP was studied by JC-1 staining. MDA-MB-231 cells were administered with IC25 (low dose) and IC50 (high dose) concentrations of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs, and untreated cells served as controls. Representative images are obtained from experiments done in triplicates. Magnification: 20× (scale = 100 µm).

3.13 Effect of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs on ROS production in MDA-MB-231 cells

Apoptosis can be induced by the excessive production of ROS via disturbing the apoptotic signaling pathways [40,41]. Due to their aberrant and uncontrollable proliferation, tumor cells are typically characterized by elevated amounts of ROS, as their basal ROS levels are higher than those of normal cells. On the contrary, an overload of ROS can cause oxidative injury to every part of the cell such as DNA, lipids, and proteins. In the beginning, ROS have the potential to oxidatively harm every mitochondrial component. The disruption of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation by damaged mitochondrial DNA causes the release of CytoC, which contributes to cell death [42].

Figure 11 shows the results of a quantification of intracellular ROS level using DCFH-DA staining in MDA-MB-231 cells that have been administered with MnCu co-doped NiO NPs. Green fluorescence was noted in the control cells but was significantly increased in cells exposed to IC25 and IC50 concentrations of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs, indicating higher ROS production than the control cells. This result demonstrated that the ROS status of MDA-MB-231 cells was elevated after exposure to MnCu co-doped NiO NPs. ROS upregulation in tumor cells is considered a promising strategy to promote cancer treatments. It was already well known that metal or metal oxide NPs could trigger excessive ROS production to promote cell necrosis in cancer cells [43] which supports the activity of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs.

A fluorescence microscope image of ROS production induced by MnCu co-doped NiO NPs stained with DCF-DA. MDA-MB-231 cells were exposed to IC25 (low dose) and IC50 (high dose) concentrations of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs, and untreated cells served as controls. Representative images are obtained from experiments done in triplicates. Magnification: 20× (scale = 100 µm).

3.14 Effect of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs on the apoptosis in the MDA-MB-231 cells

Cancer cells avoid apoptosis, allowing them to proliferate excessively and survive under stressful environments and with resistance to therapies; hence, inducing tumor cell apoptosis has emerged as a useful method for cancer treatment [44,45]. By using flow cytometry, the proportion of apoptosis in both untreated and MnCu co-doped NiO NP-exposed MDA-MB-231 cells was investigated. The outcomes revealed that the percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis was considerably elevated after exposure to the IC25 and IC50 concentrations of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs. These outcomes proved that MnCu co-doped NiO NPs increase apoptosis in breast cancer cells (Figure 12).

Annexin-V/-FITC/PI Flow cytometry study of MDA-MB-231 cancer cells exposed for 48 h with MnCu co-doped NiO NPs. MDA-MB-231 cells were administered with IC25 (low dose) and IC50 (high dose) concentrations of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs, and untreated cells served as controls. The lower left quadrant (Annexin-V/PI), lower right quadrant (Annexin-V+/PI), and upper right quadrant (Annexin-V+/PI+), respectively, denoted live cells, early apoptotic cells, and necrotic/secondary necrotic cells (a). The percentage of cells with apoptosis after administration of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs was increased. The data are presented as a mean ± standard deviation of triplicates. A two-sample t-test was employed to assess the significance between the groups (b). * Indicates the significant level p < 0.005 compared to control, and ** reveals the significant level p < 0.001 compared to control.

3.15 Effect of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs on the cell cycle arrest in the MDA-MB-231 cells

Cell cycle regulation is the primary process for regulating cell proliferation because it ensures that the changeover from one phase to another occurs in an ordered way [46]. The blocking of the cell cycle is a crucial process that influences the development of cells. The flaws in the cell cycle are a common feature of the vast majority of malignancies. It is widely accepted that slowing down the cell cycle can avert the advancement of cancer. Therefore, cell cycle targeting is a crucial strategy in cancer treatment since disruption of the cell cycle is a major characteristic of tumors [47,48].

Figure 13, this image shows the results of a FACS study comparing the dispersion of nuclei at various stages of the cell cycle. The cells incubated with IC25 and IC50 concentrations of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs revealed a lower cell percentage in the G0/G1 growth phases compared with untreated control. Additionally, the cells at S and G2/M phases were higher in MDA-MB-231 cells exposed to IC25 and IC50 concentrations of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs (b and c) when compared with untreated control (a), proving that treatment triggered cell cycle arrest.

Based on a flow cytometry analysis, this image shows the dispersion of cells during different stages of the cell cycle. More cells with the S phase were observed in cells incubated with MnCu co-doped NiO NPs at IC25 and IC50 concentrations. Cell cycle arrest was demonstrated in MDA-MB-231 cells exposed to MnCu co-doped NiO NPs at IC25 and IC50 concentrations (b and c) and untreated controls (a), which demonstrated that treatment triggered cell cycle arrest. The statistical significance of the differences between treated vs. control was determined by a two-sample t-test (d). * Indicates the significant level p < 0.005 compared to control, and ** denote the significant level p < 0.001 compared to control.

3.16 Effect of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs on apoptotic protein expressions in the MDA-MB-231 cells

Removal of aberrant cells during the development and maintenance of tissue homeostasis relies on apoptosis. Apoptosis induction is a crucial mechanism of action for many anticancer medicines [49]. Mitochondrial-dependent intrinsic and mitochondria-independent extrinsic pathways are the two main mechanisms that initiate apoptosis. The Bcl2 family of proteins is crucial for the activation of caspases, which results in the induction of apoptosis [50]. Figure 14 displays the outcomes of analyzing the influence of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs treatment on the apoptotic markers Bcl-2, Bax, Cyt-C, p53, and caspase-3, -8, and -9 expressions in MDA-MB-231 cells. Elevated expressions of these proteins were seen in MDA-MB-231 cells after treatment with IC25 and IC50 concentrations of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs. Conversely, MnCu co-doped NiO NP treatment suppressed the Bcl-2 expression, which proves that MnCu co-doped NiO NPs increase apoptotic protein expressions in breast cancer cells (Figure 14).

In MDA-MB-231 cells, NiO NPs with MnCu co-doped promote pro-apoptotic proteins. MDA-MB-231 cells were tested with ELISA kits for caspase-3, -8, and -9, Bax, Bcl-2, Cyt-C, and P53 levels. MDA-MB-231 cells were exposed to IC25 (low dose) and IC50 (high dose) concentrations of MnCu co-doped NiO NPs, and untreated cells served as controls. One-way analysis of variance was used to analyze the data in triplicates. Each bar represents the mean ± standard deviation. Using a two-sample t-test, we determined whether the differences between the treated and control groups were statistically significant. * Indicates the significant level p < 0.005 compared to control, and ** reveals the significant level p < 0.001 compared to control.

Both pro- and anti-apoptotic Bcl2 family members play roles in controlling apoptosis. Bcl2 family genes serve a pivotal function in the controlling of mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis. Cancer cells can evade apoptosis when Bcl2 is activated because it inhibits the production of the pro-apoptotic protein. Caspases are known to activate the cytoplasmic endonucleases, which break down nuclear material, which break down nuclear proteins. Caspases, a class of cysteine-aspartic acid proteases that are triggered by apoptotic pathways, are necessary for apoptosis. Mitochondrial pathway-mediated apoptosis is triggered by a decrease in MMP, which in turn triggers the release of Cyt-C, which initiates apoptosis. Our results of the present work demonstrated that MnCu co-doped NiO NPs can augment the pro-apoptotic proteins while reducing the Bcl-2 expressions, thereby promoting apoptosis.

4 Conclusions

In conclusion, the synthesis and characterization of bimetallic manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide NPs synthesized from C. papaya leaf extract to induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by activating mitochondrial caspases and p53 were novel aspects of the study. MnCu co-doped NiO NPs have been synthesized using C. papaya leaf extract. The MnCu co-doped NiO NPs were confirmed by XRD, UV–Vis, FT-IR, FESEM, EDAX, and PL spectrum. The XRD pattern demonstrated that synthesized MnCu co-doped NiO NPs exhibit cubic structure. From the UV–Vis spectra, the green-synthesized MnCu co-doped NiO NP absorbance edge was observed at 342 nm. In the FESEM image, the MnCu co-doped NiO NPs were formed into a nanorod-like structure. Chemical components were assessed via the EDAX spectrum. In the PL spectrum, various surface defects were identified. MnCu co-doped NiO NPs exhibit ferromagnetic character at 37°C. MnCu co-doped NiO NPs also demonstrate antimicrobial activity. Furthermore, MnCu co-doped NiO NPs effectively decreased cell viability and promoted apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells. MnCu co-doped NiO NPs significantly improved apoptotic protein expressions. The MnCu co-doped NiO NPs were also effective at inhibiting the cell cycle. These findings highlight the simple, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly strategy for synthesizing MnCu co-doped NiO NPs using easily available C. papaya extract with excellent antimicrobial activity.

Acknowledgment

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Jouf University for funding this research work through the project number DSR2023-01-02485.

-

Funding information: This research work was funded byProject No. DSR2023-01-02449 from the the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Jouf Universityunder grant.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Zheng K, Setyawati MI, Leong DT, Xie J. Antimicrobial silver nanomaterials. Coord Chem Rev. 2018;357:1–7.10.1016/j.ccr.2017.11.019Search in Google Scholar

[2] Aswini R, Murugesan S, Kannan K. Bio-engineered TiO2 nanoparticles using Ledebouria revoluta extract: Larvicidal, histopathological, antibacterial and anticancer activity. Int J Environ Anal Chem. 2021;101(15):2926–36.10.1080/03067319.2020.1718668Search in Google Scholar

[3] Khan SA, Shahid S, Ayaz A, Alkahtani J, Elshikh MS, Riaz T. Phytomolecules-coated NiO nanoparticles synthesis using abutilon indicum leaf extract: antioxidant, antibacterial, and anticancer activities. Int J Nanomed. 2021;16:1757.10.2147/IJN.S294012Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Abdur Rahman M, Radhakrishnan R. Microstructural properties and antibacterial activity of Ce doped NiO through chemical method. SN Appl Sci. 2019;1:1–9.10.1007/s42452-019-0232-ySearch in Google Scholar

[5] Ghazal S, Khandannasab N, Hosseini HA, Sabouri Z, Rangrazi A, Darroudi M. Green synthesis of copper-doped nickel oxide nanoparticles using okra plant extract for the evaluation of their cytotoxicity and photocatalytic properties. Ceram Int. 2021;47(19):27165–76.10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.06.135Search in Google Scholar

[6] Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49.10.3322/caac.21660Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Cao W, Chen HD, Yu YW, Li N, Chen WQ. Changing profiles of cancer burden worldwide and in China: a secondary analysis of the global cancer statistics 2020. Chin Med J. 2021;134(7):783–91.10.1097/CM9.0000000000001474Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Tavana E, Mollazadeh H, Mohtashami E, Modaresi SM, Hosseini A, Sabri H, et al. Quercetin: a promising phytochemical for the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. BioFactors. 2020;46(3):356–66.10.1002/biof.1605Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Alafaleq NO, Zughaibi TA, Jabir NR, Khan AU, Khan MS, Tabrez S. Biogenic synthesis of Cu-Mn bimetallic nanoparticles using pumpkin seeds extract and their characterization and anticancer efficacy. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2023 Mar;13(7):1201. PMID: 37049295; PMCID: PMC10096695. 10.3390/nano13071201.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Eskandari A, Suntharalingam K. A reactive oxygen species-generating, cancer stem cell-potent manganese(ii) complex and its encapsulation into polymeric nanoparticles. Chem Sci. 2019 Jul;10(33):7792–800. PMID: 31588328; PMCID: PMC6764274 . 10.1039/c9sc01275c.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Yao Y, Zhou Y, Liu L, Xu Y, Chen Q, Wang Y, et al. Nanoparticle-based drug delivery in cancer therapy and its role in overcoming drug resistance. Front Mol Biosci. 2020 Aug;7:193. PMID: 32974385; PMCID: PMC7468194. 10.3389/fmolb.2020.00193.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Mehdizadeh T, Zamani A, Abtahi Froushani SM. Preparation of Cu nanoparticles fixed on cellulosic walnut shell material and investigation of its antibacterial, antioxidant and anticancer effects. Heliyon. 2020 Mar;6(3):e03528. PMID: 32154429; PMCID: PMC7057200. 10.1016/j.heliyon. 2020.e03528.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Skłodowski K, Chmielewska-Deptuła SJ, Piktel E, Wolak P, Wollny T, Bucki R. Metallic nanosystems in the development of antimicrobial strategies with high antimicrobial activity and high biocompatibility. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Jan;24(3):2104. PMID: 36768426; PMCID: PMC9917064. 10.3390/ijms24032104.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Quintal-Chávez P, González-Flores T, Rodríguez-Buenfil I, Gallegos-Tintoré S. Antifungal activity in ethanolic extracts of Carica papaya L. cv. Maradol leaves and seeds. Indian J Microbiol. 2011;51(1):54–60.10.1007/s12088-011-0086-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Radhakrishnan N, Lam KW, Norhaizan ME. Molecular docking analysis of Carica papaya Linn constituents as antiviral agent. Int Food Res J. 2017;24(4):1819–25Search in Google Scholar

[16] Khashan KS, Sulaiman GM, Abdul Ameer FA, Napolitano G. Synthesis, characterization and antibacterial activity of colloidal NiO nanoparticles. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2016;29(2):541–6Search in Google Scholar

[17] Noukelag SK, Mohamed HE, Moussa B, Razanamahandry LC, Ntwampe SK, Arendse CJ. Structural and optical investigations of biosynthesized bunsenite NiO nanoparticles (NPs) via an aqueous extract of Rosmarinus officinalis (rosemary) leaves. Mater Today: Proc. 2021;36:245–50.10.1016/j.matpr.2020.03.314Search in Google Scholar

[18] Vijaya Kumar P, Jafar Ahamed A, Karthikeyan M. Synthesis and characterization of NiO nanoparticles by chemical as well as green routes and their comparisons with respect to cytotoxic effect and toxicity studies in microbial and MCF-7 cancer cell models. SN Appl Sci. 2019;1:1–5.10.1007/s42452-019-1113-0Search in Google Scholar

[19] Liu K, Liu PC, Liu R, Wu X. Dual AO/EB staining to detect apoptosis in osteosarcoma cells compared with flow cytometry. Med Sci Monit Basic Res. 2015 Feb;21:15–20. PMID: 25664686. PMCID: PMC4332266. 10.12659/MSMBR.893327.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Bessa MJ, Brandão F, Querido MM, Costa C, Pereira CC, Valdiglesias V, et al. Optimization of the harvesting and freezing conditions of human cell lines for DNA damage analysis by the alkaline comet assay. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen. 2019 Sep;845:402994. Epub 2018 Dec 10. PMID: 31561887. 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2018.12.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Chazotte B. Labeling nuclear DNA using DAPI. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011 Jan;2011(1):pdb.prot5556. PMID: 21205856. 10.1101/pdb.prot5556.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Perelman A, Wachtel C, Cohen M, Haupt S, Shapiro H, Tzur A. JC-1: alternative excitation wavelengths facilitate mitochondrial membrane potential cytometry. Cell Death Dis. 2012 Nov;3(11):e430. PMID: 23171850. PMCID: PMC3542606. 10.1038/cddis.2012.171.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Eruslanov E, Kusmartsev S. Identification of ROS using oxidized DCFDA and flow-cytometry. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;594:57–72. PMID: 20072909. 10.1007/978-1-60761-411-1_4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Lakshmanan I, Batra SK. Protocol for apoptosis assay by flow cytometry using Annexin V staining method. Bio Protoc. 2013 Mar;3(6):e374. PMID: 27430005. PMCID: PMC4943750. 10.21769/bioprotoc.374.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Kim KH, Sederstrom JM. Assaying cell cycle status using flow cytometry. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2015 Jul;111:28.6.1–11. PMID: 26131851. PMCID: PMC4516267 .10.1002/0471142727.mb2806s111.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Ramadan MA, Shawkey AE, Rabeh MA, Abdellatif AO. Expression of P53, BAX, and BCL-2 in human malignant melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma cells after tea tree oil treatment in vitro. Cytotechnology. 2019 Feb;71(1):461–73. Epub 2019 Jan 1 PMID: 30599074. PMCID: PMC6368524. 10.1007/s10616-018-0287-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Zhang G, Yu L, Hoster HE, Lou XW. Synthesis of one-dimensional hierarchical NiO hollow nanostructures with enhanced supercapacitive performance. Nanoscale. 2013;5(3):877–81.10.1039/C2NR33326KSearch in Google Scholar

[28] Mustapha S, Tijani JO, Ndamitso MM, Abdulkareem AS, Shuaib DT, Amigun AT, et al. Facile synthesis and characterization of TiO2 nanoparticles: X-ray peak profile analysis using Williamson–Hall and Debye–Scherrer methods. Int Nano Lett. 2021;11(3):241–61.10.1007/s40089-021-00338-wSearch in Google Scholar

[29] Kim D, Hong J, Park YR, Kim KJ. The origin of oxygen vacancy induced ferromagnetism in undoped TiO2. J Phys: Condens Matter. 2009;21(19):195405.10.1088/0953-8984/21/19/195405Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Thangamani C, Vijaya Kumar P, Gurushankar K, Pushpanathan K. Structural and size dependence magnetic properties of Mn-doped NiO nanoparticles prepared by wet chemical method. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron. 2020;31(14):11101–12.10.1007/s10854-020-03659-2Search in Google Scholar

[31] Latvala S, Hedberg J, Di Bucchianico S, Möller L, Odnevall Wallinder I, Elihn K, et al. Nickel release, ROS generation and toxicity of Ni and NiO micro-and nanoparticles. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159684.10.1371/journal.pone.0159684Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Hameed AS, Karthikeyan C, Sasikumar S, Kumar VS, Kumaresan S, Ravi G. Impact of alkaline metal ions Mg 2 +, Ca 2 +, Sr 2 + and Ba 2 + on the structural, optical, thermal and antibacterial properties of ZnO nanoparticles prepared by the co-precipitation method. J Mater Chem B. 2013;1(43):5950–62.10.1039/c3tb21068eSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Leung YH, Ng AM, Xu X, Shen Z, Gethings LA, Wong MT, et al. Mechanisms of antibacterial activity of MgO: non‐ROS mediated toxicity of MgO nanoparticles towards Escherichia coli. Small. 2014;10(6):1171–83.10.1002/smll.201302434Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Hameed AS, Karthikeyan C, Kumar VS, Kumaresan S, Sasikumar S. Effect of Mg2 +, Ca2 +, Sr2 + and Ba2 + metal ions on the antifungal activity of ZnO nanoparticles tested against Candida albicans. Mater Sci Eng C. 2015;52:171–7.10.1016/j.msec.2015.03.030Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65(1–2):55–63.10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Liu K, Liu PC, Liu R, Wu X. Dual AO/EB staining to detect apoptosis in osteosarcoma cells compared with flow cytometry. Med Sci Monit Basic Res. 2015;21:15.10.12659/MSMBR.893327Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Baskar R, Dai J, Wenlong N, Yeo R, Yeoh KW. Biological response of cancer cells to radiation treatment. Front Mol Biosci. 2014;1:24.10.3389/fmolb.2014.00024Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Bate C, Tayebi M, Williams A. A glycosylphosphatidylinositol analog reduced prion-derived peptide-mediated activation of cytoplasmic phospholipase A2, synapse degeneration, and neuronal death. Neuropharmacology. 2010;59(1–2):93–9.10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.04.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Zhu X, Wang K, Zhang K, Zhu L, Zhou F. Ziyuglycoside II induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis through activation of ROS/JNK pathway in human breast cancer cells. Toxicol Lett. 2014 May;227(1):65–73.10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.03.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Agoni L, Basu I, Gupta S, Alfieri A, Gambino A, Goldberg GL, et al. Rigosertib is a more effective radiosensitizer than cisplatin in concurrent chemoradiation treatment of cervical carcinoma, in vitro and in vivo. Int J Radiat Oncol* Biol* Phys. 2014;88(5):1180–7.10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.12.051Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Kumari S, Badana AK, Malla R. Reactive oxygen species: a key constituent in cancer survival. Biomark Insights. 2018;13:1177271918755391.10.1177/1177271918755391Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Duman FD, Sebek M, Thanh NT, Loizidou M, Shakib K, MacRobert AJ. Enhanced photodynamic therapy and fluorescence imaging using gold nanorods for porphyrin delivery in a novel in vitro squamous cell carcinoma 3D model. J Mater Chem B. 2020;8(23):5131–42.10.1039/D0TB00810ASearch in Google Scholar

[43] Zhang Y, Chen S, Wei C, Rankin GO, Rojanasakul Y, Ren N, et al. Dietary compound proanthocyanidins from Chinese bayberry (Myrica rubra Sieb. et Zucc.) leaves inhibit angiogenesis and regulate cell cycle of cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer cells via targeting Akt pathway. J Funct foods. 2018;40:573–81.10.1016/j.jff.2017.11.045Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Nishida K, Yamaguchi O, Otsu K. Crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis in heart disease. Circ Res. 2008;103(4):343–51.10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.175448Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Fu Y, Kadioglu O, Wiench B, Wei Z, Gao C, Luo M, et al. Cell cycle arrest and induction of apoptosis by cajanin stilbene acid from Cajanus cajan in breast cancer cells. Phytomedicine. 2015;22(4):462–8.10.1016/j.phymed.2015.02.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Duan YC, Zheng YC, Li XC, Wang MM, Ye XW, Guan YY, et al. Design, synthesis and antiproliferative activity studies of novel 1, 2, 3-triazole–dithiocarbamate–urea hybrids. Eur J Med Chem. 2013;64:99–110.10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.03.058Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Lavrik IN, Golks A, Krammer PH. Caspases: pharmacological manipulation of cell death. J Clin Investig. 2005;115(10):2665–72.10.1172/JCI26252Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Otto T, Sicinski P. Cell cycle proteins as promising targets in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(2):93–115.10.1038/nrc.2016.138Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Suraweera CD, Hinds MG, Kvansakul M. Poxviral strategies to overcome host cell apoptosis. Pathogens. 2020;10(1):6.10.3390/pathogens10010006Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Chang J, Hsu Y, Kuo P, Kuo Y, Chiang L, Lin C. Increase of Bax/Bcl-XL ratio and arrest of cell cycle by luteolin in immortalized human hepatoma cell line. Life Sci. 2005;76(16):1883–93.10.1016/j.lfs.2004.11.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress