Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

-

Imran Ullah

, Mushtaq Ahmad

, Abdulrahman Alshammari

Abstract

The current research aimed to gain insights into the synthesis, characterization, and biomedical applications of ultra-small (US) zinc oxide (ZnO) and manganese (Mn), cobalt (Co), aluminum (Al)-doped ZnO nanoparticles (NPs). These NPs were synthesized using the sol–gel method and treated with various organic ligand molecules, serving as surface modifiers and stabilizers. The influence of ligand molecules on the growth kinetics was observed by monitoring the synthesis time until gel formation, which revealed that the ligand molecules significantly slowed down gelation. Moreover, the shape and final size of NPs were also analyzed. X-ray diffraction (XRD) confirmed single-phase crystallization in all samples. Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy revealed a broad absorbance peak in the range of 347–355 nm. Tauc’s method estimated an optical bandgap of 3.1–3.16 eV. Infrared Fourier transform (FT-IR) spectroscopy corroborated the formation of ZnO NPs decorated with various functional groups. Structural studies were performed using DISCUS software, where all necessary parameters were refined, and suggested a crystallite/NP size in the range of 3–10 nm. The citrate molecule (cit), a capping agent, exhibits the smallest crystallite/NPs. The samples were explored for antimicrobial and anti-acetylcholinesterase enzyme (AChE) activities. Among all samples, only 3–5% Mn-doped ZnO with acetate (ac) molecules as ligands showed antimicrobial activities at different concentrations. Moreover, 3% and 5% Co-doped ZnO with ac, and 3% Co-doped ZnO with dimethyl-l-tartrate (dmlt) and cit, were also active at various concentrations against Gram-positive bacteria, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and Bacillus cereus (BC). The highest zone of inhibition of 7.5 ± 0.2 mm against MRSA and 10.0 mm for BC were observed. The lowest zone of inhibition was reported as 3.25 ± 0.25 mm against MRSA and 3.0 mm against BC. A direct relationship between the zone of inhibition and the concentration was observed. ZnO NPs inhibit 87.39 ± 0.002% AChE, while 3% Al-doped, 3 and 5% Co-doped NPs inhibit 78.8 ± 0.017%, 56.2 ± 0.002%, and 62.7 ± 0.051% AChE, respectively. An intermediate response of AChE inhibition was observed: 42.0 ± 0.018% for 3% Mn-doped NPs and 32.6 ± 0.0034% for 5% Mn-doped NPs. Various strategies were employed to further optimize their activities.

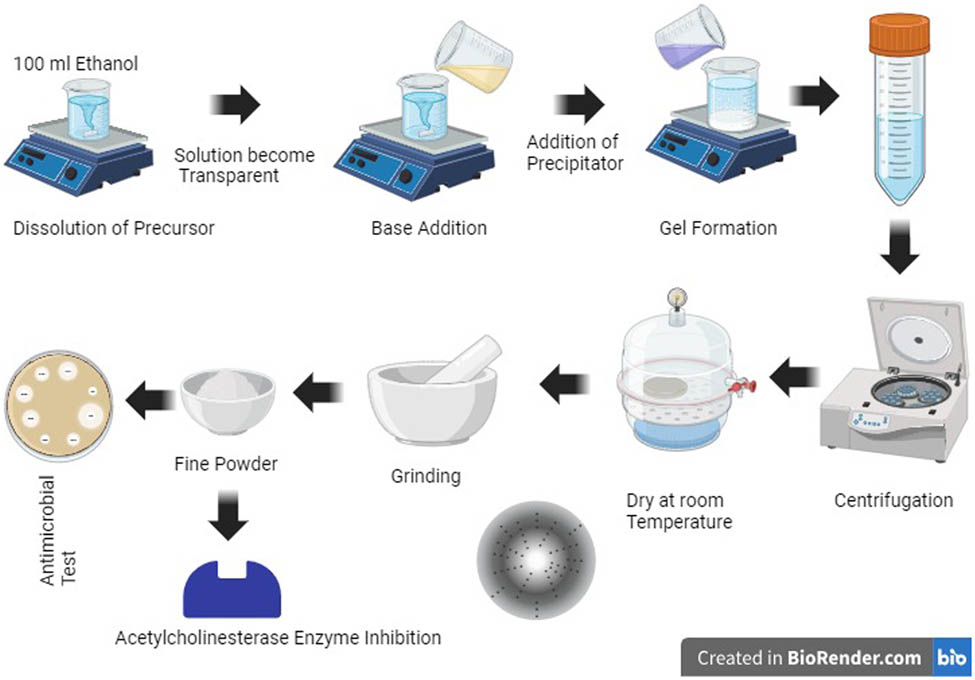

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Richard Feynman, an American scientist, first highlighted the concept of nanotechnology in 1959. Nanomaterials are materials with dimensions reduced to the nanoscale. Their use in electronics, energy storage, medicine, and other fields makes them an exciting area of research [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Research is ongoing in fabricating, characterizing, and exploring the contribution of nanoparticles (NPs) to science and technology [7,8,9]. At the nanoscale, the surface-to-volume ratio increases significantly, resulting in the observation of the quantum confinement effect, specifically when the size of NPs is comparable to Bohr radii [10]. Metal oxide, specifically zinc oxide (ZnO) NPs, have been extensively studied. They are wide and direct bandgap semiconductors, with bandgaps ranging from 3.0 to 4.5 eV, and a large exciton energy of 60 meV. Neder et al. performed structural analysis and local structure studies of ZnO NPs using the atomic pair distribution function (PDF) [11,12,13]. Zobel et al. performed in situ studies for ZnO time-resolved structure analysis [14]. Moreover, Meulenkamp studied their growth mechanisms [15]. Surface modification alters and tunes NP properties [16]. Control over size, shape, and morphology are the key factors in choosing an appropriate synthesis approach, along with cost-effectiveness, environmental friendliness, non-toxicity, and functionality. Two general synthesis approaches are top-down and bottom-up, with more innovative approaches also being introduced [17]. The top-down approach is straightforward, while the bottom-up approach involves more complex steps and is known for better control over size, shape, and morphology [18]. The sol–gel method is a specific choice for obtaining ultra-small (US) sizes, while the precipitation method is fast and preferable for the bulk production of NPs [19]. Particles with dimensions less than 10 nm are categorized as quantum dots, which possess unique quantum mechanical properties. US-NPs, ranging from 3 to 15 nm [20].

NPs are characterized through various techniques, including X-ray diffraction (XRD), ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy, infrared Fourier transform (FT-IR) spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and atomic force microscopy (AFM). Structural analysis, including crystal structure, phase identification, grain size, shape, and morphology, is performed using XRD. Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) is preferred for size distribution and understanding the growth mechanisms. Further details can be found in the study of Mourdikoudis et al. [21].

The non-toxic nature of ZnO NPs has opened new avenues for biomedical applications, including their use as drug carriers, biosensing materials, and photocatalysts. ZnO NPs are effective in removing contaminants from wastewater and exhibit strong antibacterial properties, making them useful in medical applications. They are also valuable in environmental remediation by breaking down harmful chemicals through photocatalysis. Doping ZnO NPs with manganese (Mn), cobalt (Co), and aluminum (Al) enhances their photocatalytic efficiency, stability, and antibacterial properties, making them highly effective in advanced water treatment and pollutant degradation [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Increasing antibiotic resistance and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are two significant healthcare challenges. The misuse of antibiotics strengthens bacterial resistance, leading to prolonged antibiotic use and increased mortality rates [36,37,38]. Fifty-five million people are living with AD and other dementia, and this might increase to two billion by 2,050, as reported by the World Health Organization (WHO) and Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI) [39]. AD is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by memory loss with no effective treatment to date. In Alzheimer’s patients, AChE activity is abnormally increased, further exacerbating the decline in acetylcholine levels. Biocompatible, environmentally friendly, cost-effective, and non-toxic metal, metal oxide, and metal peroxide NPs have the potential to combat microbes and AD [40,41,42,43,44,45,46].

In this work, ZnO, Mn x , Co x , and Al x -doped Zn1−x O US-NPs stabilized with different organic ligand molecules were synthesized using the sol–gel method. The effects of these ligand molecules on the shape and size were analyzed. For structural analysis, XRD was performed on all samples. Rietveld-type refinement was carried out using the DISCUS package [47]. Lattice parameters “a” (P_lata) and “c” (P_latc), the position of zinc (P_z_zn) in the unit cell, the Debye–Waller factor (P_biso), stacking fault probabilities (P_stack), and diameter along various directions were refined. The results of their structural analysis were found to agree with previous studies [14]. Furthermore, their potential as antimicrobial agents against Gram-positive bacteria, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA, and Bacillus cereus (BC), as well as their anti-AChE activities, was explored.

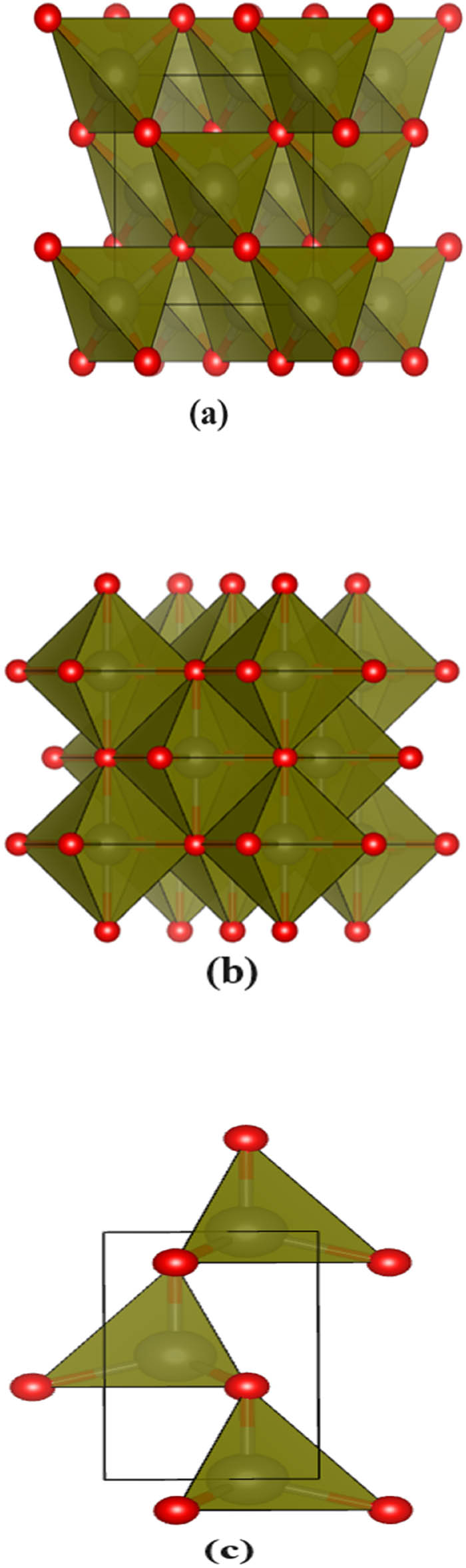

2 Crystal structures

Zinc oxide can be found in three different crystal structures: zincblende, rock salt, and wurtzite. ZnO rarely crystallizes in the zincblende structure, where the lattice parameters are

Three different crystal structures of ZnO. (a) zincblende, (b) rock salt, and (c) wurtzite.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Chemicals

A detailed list of chemicals (analytical grade) used during the synthesis of Mn x , Co x , and Al x -doped Zn1−x O US-NPs is provided in Table S1 and was used without further purification.

3.2 Stabilizer selection

Post-synthesis stability of NPs is crucial due to size-dependent properties, and the ligand molecules have the potential to prevent aggregation or agglomeration. Moreover, slowing the growth kinetics in different directions can result in the formation of faceted NPs, which can interact uniquely with other materials [48,49]. For the present work, three different organic ligand molecules, citric acid (cit), 1, 5-diphenyl-1,3,5-pentanetrione (pent), and dimethyl-l-tartrate (dmlt), were used without further purification.

3.3 Synthesis of ZnO and doped ZnO NPs

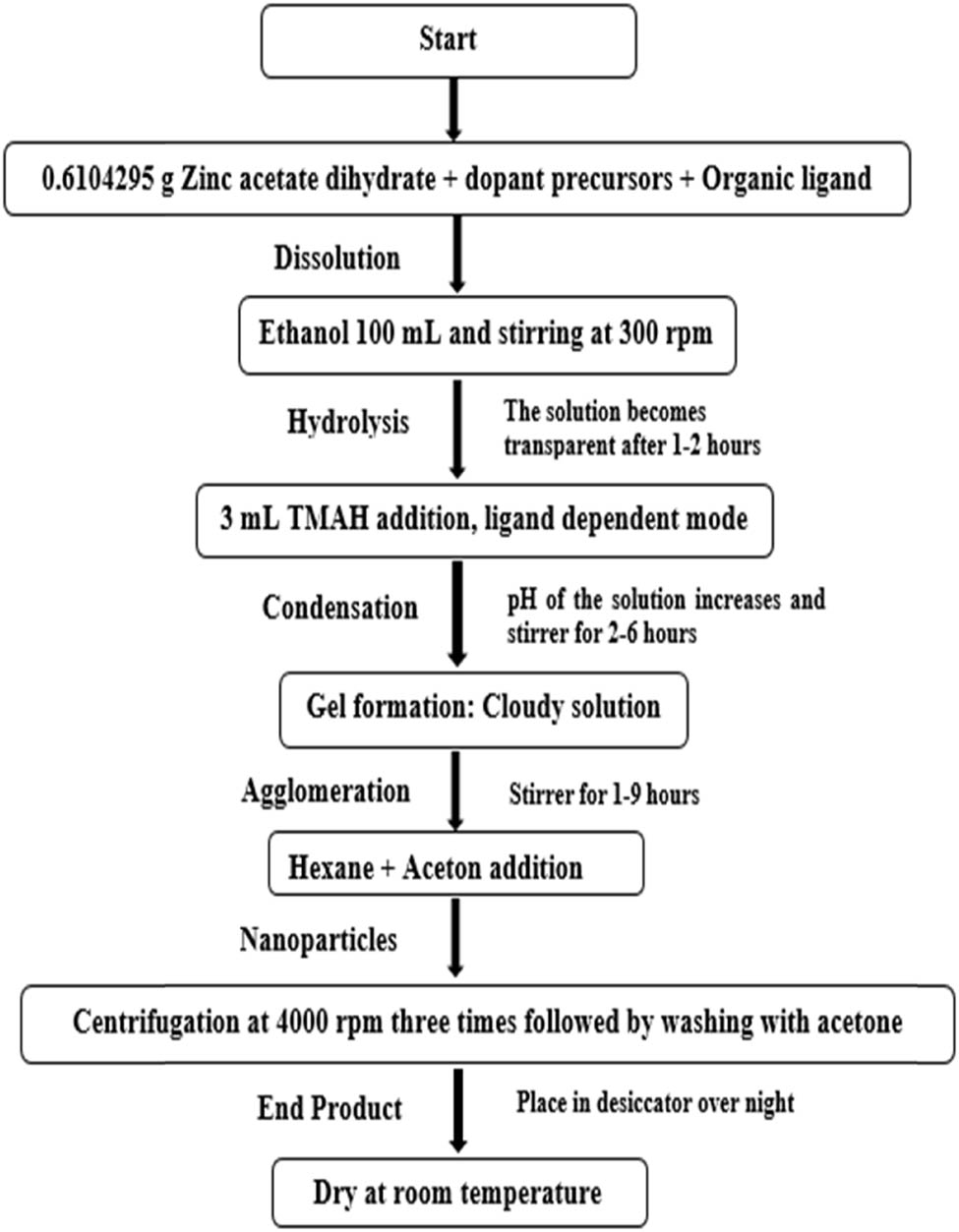

Synthesis approaches play a vital role in obtaining NPs of the desired size, shape, and morphology [50]. The two utmost approaches are the top-down [51] and bottom-up approach [52]. For the current work, the synthesis recipe introduced by Spanhel and Anderson, modified by Meulenkamp [15], Wood et al. and Chory et al. [53,54,55] was adopted. A mixture of 0.6104295 g of zinc acetate dihydrate and an optimized amount of ligand molecules were first dissolved in 100 mL of ethanol using magnetic stirring (300 rpm) at room temperature. Once the solution became transparent, 3 mL of tetra-methyl ammonium hydroxide (TMAH, 25% in methanol) was added gradually to obtain the desired

For Mn x , Co x , and Al x -doped synthesis, an optimized amount of dopant precursors (cobalt acetate tetrahydrate, manganese acetate tetrahydrate, and aluminum acetate basic) was added to the mixture at the first stage, and the same steps stated above were followed. The complete flow chart is shown in Scheme 1.

A schematic chart for the synthesis of pure and doped ZnO US-NPs.

3.4 Optimal conditions

The chemical reaction is carried out at room temperature by tweaking the amount of base (TMAH) through a trial-and-error method to determine the right conditions for producing US-NPs. Interestingly, the reaction takes place under regular atmospheric pressure.

3.5 Characterization

XRD scans are performed using X’pert (Philips) and smart-lab (Rigaku) diffractometers, employing copper radiation with wavelengths

3.6 Structural studies

DISCUS software, a tool for refining NP models against experimental data (XRD), was employed for structural studies. DISCUS uses the DIFFEV program, which is a part of the DISCUS package and relies on a differential evolutionary algorithm [56]. DISCUS reads asymmetric unit cells and extends them in various directions. A model is developed several times, incorporating various types of defects, and is trimmed to the appropriate size. The corresponding powder XRD (PXRD) is calculated using the Debye scattering equation (Eq. 1) each time and is averaged before comparing it to the experimental data. Throughout the refinement process, the goodness of fit (R-value) is assessed at each generation or iteration. The resulting set of parameters is iteratively transmitted internally to DIFFEV to facilitate ongoing refinement [47]:

3.7 Antimicrobial assay

A homogeneous solution (1 mg·mL−1) of the synthesized sample was obtained by dispersing 1 mg of the sample in 1 mL of DMSO. The stock solution was diluted to obtain various concentrations (25%, 50%, 75%, 100%) using the following relation:

To investigate the antimicrobial assay of the synthesized samples, the agar well diffusion method [57] was preferred. To avoid any contamination, the equipment was subjected to autoclaving at 120°C for 50 min at a pressure of 15

3.8 Anti-acetylcholinesterase enzyme (anti-AChE) assay

In the present work, AChE inhibition was determined using a slightly modified method inspired by Rocha et al. [58] and Ahmed et al. [59], utilizing a double-beam spectrophotometer. Upon substrate addition, the enzyme–substrate reaction occurred promptly, and the development of yellow color was used to track the hydrolysis process. Hydrolysis rates (V) were determined at 1 mmol acetylthiocholine (S) concentration in a 1 mL assay mixture containing 50 mmol phosphate buffer at

3.9 Statistical analysis

All results are presented as mean ± SE.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Reaction mechanism

In the present work, the reaction is carried out in ethanol, where the metal salts dissociate into metal and acetate ions, followed by the release of water molecules, as depicted in (2):

Acetic acid is formed by capturing

The

4.2 XRD

All synthesized samples were measured in the

XRD of pure ZnO (US-NPs).

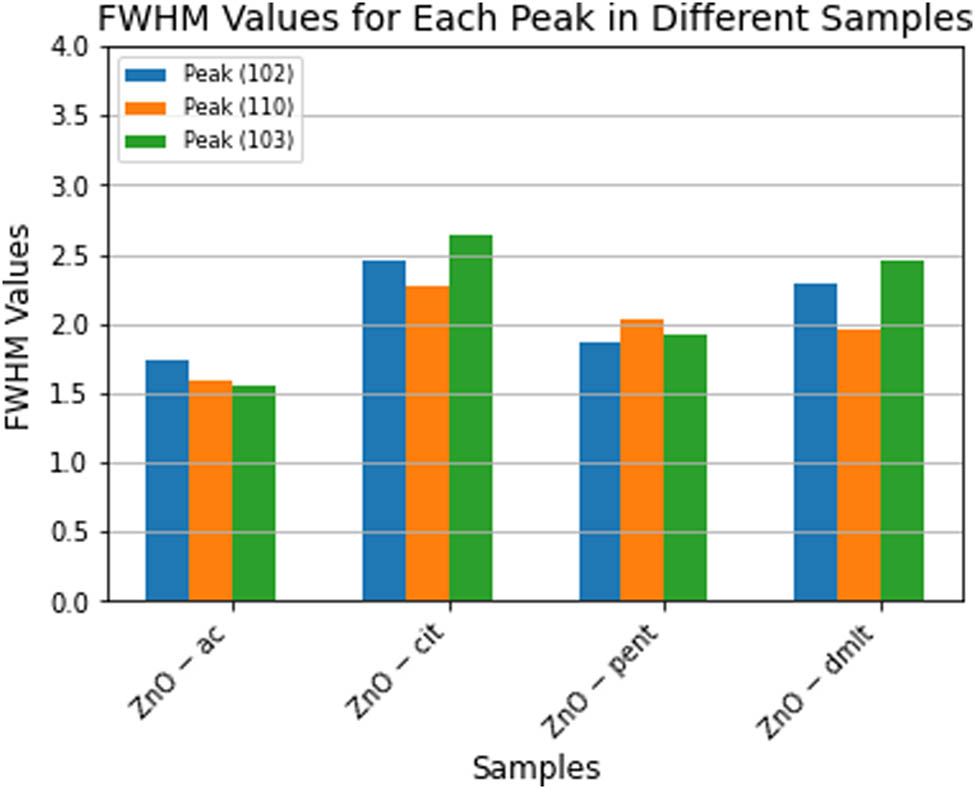

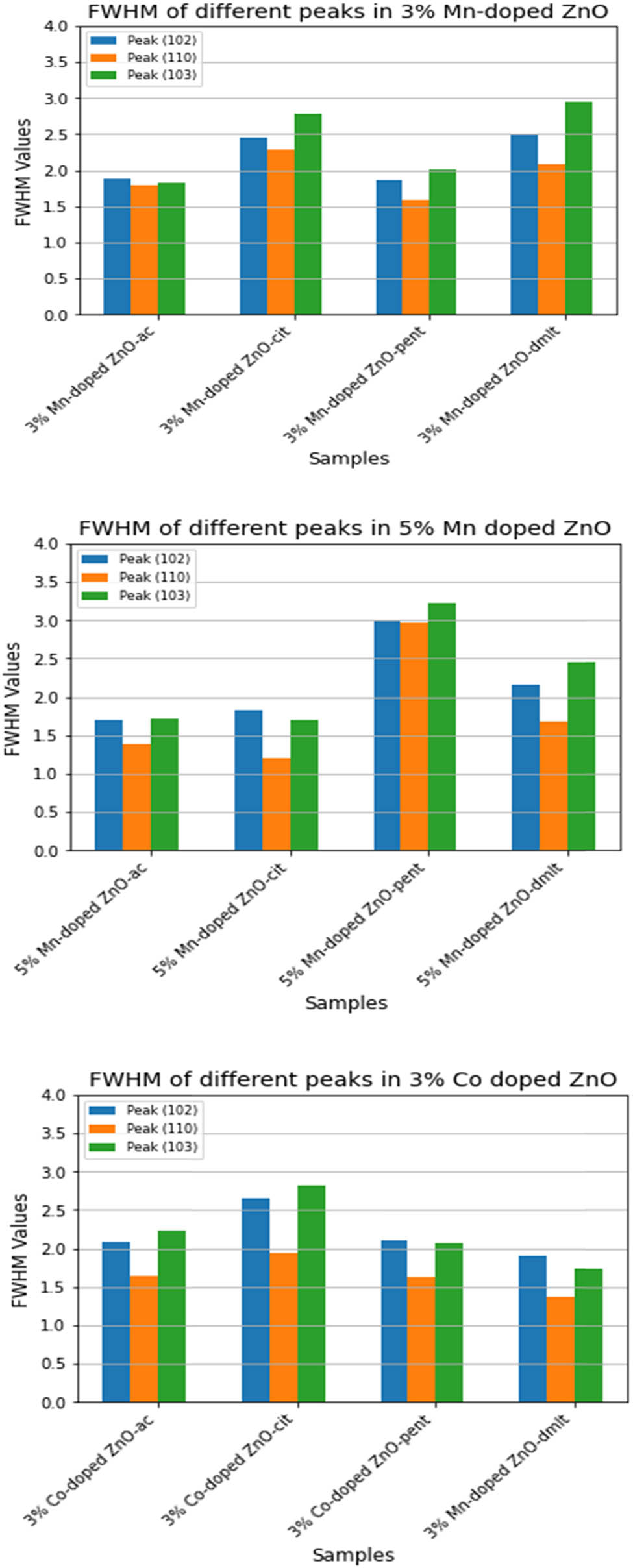

The (102), (110), and (103) peaks were chosen to provide insight into the effect of ligand molecules on the size of the grain/particles. A pseudo-Voigt function (Eq. 4), with no instrumental contribution, was fitted to these well-resolved peaks. The corresponding FWHM (Eq. 5) values are shown in Figure 3. The results clearly show that cit and dmlt as capping agents/stabilizers result in the formation of the smallest grains/particles. The powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) of doped samples is depicted in Figure 4. The effect of Mn, Co, and Al incorporation into the lattice is shown in Table 1. A slight shift in the peak position is observed upon 3% Mn, Co, and Al-doping to lower

FWHM of peaks (102), (110), (103), and (112).

XRD of doped ZnO (US-NPs).

Peak position with and without doping

| Peak | Position (ZnO-ac) | Position (3% Mn-doped ZnO-ac) | Position (3% Co-doped ZnO-ac) | Position (3% Al-doped ZnO-ac) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (100) | 31.878 | 31.886 | 31.885 | 31.852 |

| (002) | 34.535 | 34.526 | 34.505 | 34.526 |

| (101) | 36.298 | 36.272 | 36.245 | 36.306 |

FWHM of peaks (102), (110), (103), and (112) for doped ZnO NPs.

In the context of

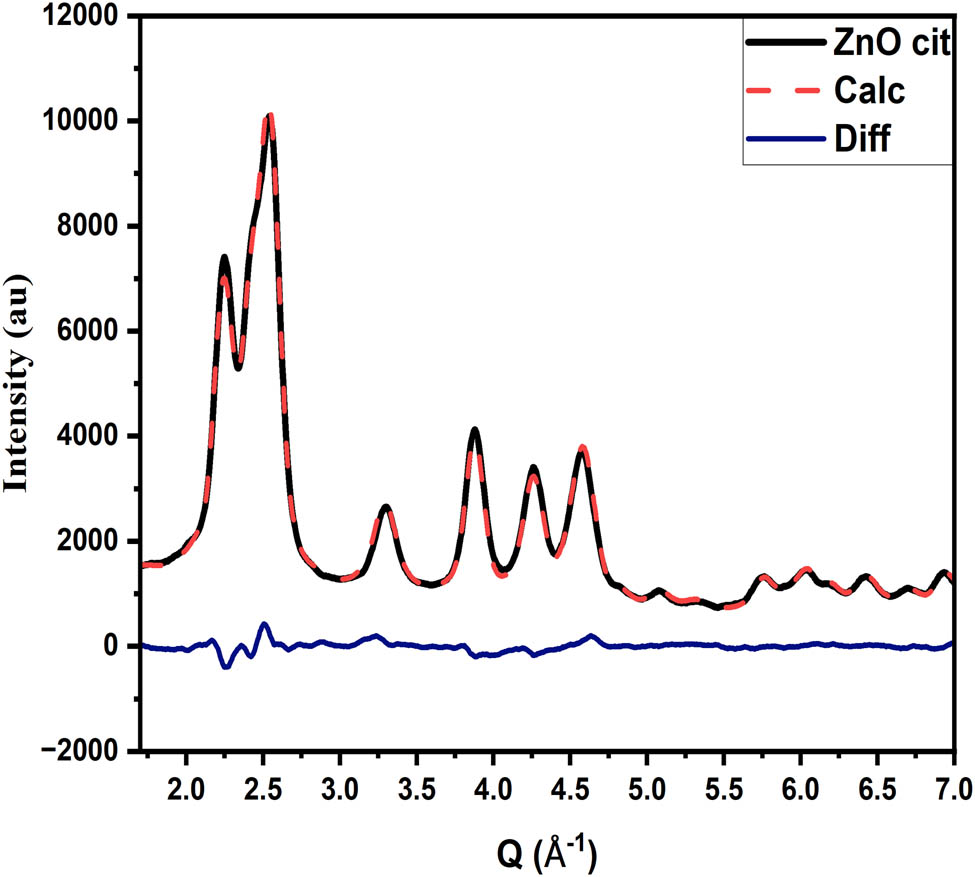

4.3 Structural analysis of ZnO and doped ZnO NPs

Refinement of pure ZnO NPs and various metal-doped ZnO NPs was carried out using the DISCUS package for in-depth investigation (Figures 6–8). The most crucial parameters were refined, including lattice parameters, zinc position, Debye–Waller factor, stacking fault probabilities, and diameters in various directions. Each parameter is provided with initial (minimum and maximum) and allowed values, respectively. The program does not accept any value below or above the allowed range. To simulate the model of the crystallite/NPs, an asymmetric unit cell of the corresponding material is provided. Using an initial guess, the program simulates the crystallite/NPs 50 times, introducing stacking faults in the process. The model is decorated with the corresponding ligand molecules, and PXRD is calculated, averaged, and compared with experimental data. The program refined all parameters effectively. The largest and smallest refined diameters are 10.86 and 2.25 nm, suggesting that the size of crystallite/NPs is in the range of 3–10 nm. The corresponding refined values and goodness of fit are shown in Table 2 and Figure 8 (with the lattice parameter and diameter measured in

Final suggested Model of ZnO NPs without (a) and with citrate-stabilized (b) based on XRD data refinement.

Schematic of citrate molecule attachment.

The goodness of fit.

Refined parameters and their corresponding values

| Sample name | P_lata | P_latc | P_z_zn | P_biso | P_stack | P_aa_dia | P_cc_dia | P_hoh_dia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

3.23901 | 5.18958 | 0.39145 | 1.92100 | 0.09531 | 74.9115 | 108.6188 | 63.2912 |

|

|

3.24675 | 5.20649 | 0.38745 | 1.98060 | 0.07732 | 58.6703 | 42.4064 | 40.9344 |

|

|

3.23646 | 5.19013 | 0.38751 | 1.91560 | 0.05601 | 78.11280 | 81.97060 | 48.48093 |

|

|

3.24213 | 5.21317 | 0.38512 | 1.93238 | 0.02796 | 48.55360 | 31.87900 | 95.79885 |

| 3%

|

3.23633 | 5.19039 | 0.38243 | 1.95899 | 0.09668 | 79.62217 | 90.25679 | 55.51118 |

| 3%

|

3.24522 | 5.20665 | 0.38619 | 2.07671 | 0.07085 | 58.65078 | 34.67142 | 43.14034 |

| 3%

|

3.23755 | 5.20122 | 0.37949 | 2.28365 | 0.10982 | 77.60022 | 58.57095 | 58.78221 |

| 3%

|

3.23574 | 5.21303 | 0.38528 | 2.23463 | 0.07324 | 74.84885 | 35.39911 | 44.84623 |

| 5%

|

3.23836 | 5.19497 | 0.38394 | 2.43065 | 0.12340 | 79.93556 | 79.93556 | 62.96924 |

| 5%

|

3.24620 | 5.21888 | 0.38980 | 2.47807 | 0.11236 | 63.98719 | 53.62492 | 98.93822 |

| 5%

|

3.25694 | 5.25632 | 0.36266 | 1.26744 | 0.12537 | 33.11816 | 22.55922 | 91.44874 |

| 5%

|

3.24515 | 5.22968 | 0.37724 | 2.25117 | 0.08474 | 51.83550 | 46.80184 | 90.93870 |

| 3%

|

3.23069 | 5.19738 | 0.37330 | 1.72624 | 0.08643 | 55.50845 | 46.19934 | 98.32239 |

| 3%

|

3.25014 | 5.22283 | 0.39096 | 2.37353 | 0.13687 | 79.63631 | 51.60688 | 48.60547 |

| 3%

|

3.24981 | 5.22323 | 0.39145 | 2.22731 | 0.11652 | 77.44628 | 63.52468 | 55.00147 |

| 3%

|

3.23633 | 5.19007 | 0.38244 | 2.29995 | 0.14030 | 78.24615 | 89.88307 | 66.20509 |

| 5%

|

3.24928 | 5.20869 | 0.39376 | 2.12630 | 0.06407 | 79.21581 | 76.23872 | 75.75505 |

| 5%

|

3.23681 | 5.18996 | 0.38002 | 2.34351 | 0.17937 | 79.63058 | 63.77353 | 99.96952 |

| 5%

|

3.23832 | 5.20974 | 0.37958 | 2.32586 | 0.11586 | 62.30255 | 48.26083 | 91.07546 |

| 5%

|

3.23522 | 5.19062 | 0.37836 | 2.42685 | 0.12657 | 79.76083 | 60.81242 | 99.80237 |

| 3%

|

3.24240 | 5.20577 | 0.38377 | 2.10126 | 0.06709 | 58.47890 | 52.21315 | 98.65446 |

Ligand molecules can bind either via physisorption (through van der Waals interactions) or chemisorption (proper bonding scheme) to the active site at the surface and act as stabilizers. Specifically, cit molecules (tricarboxylic acid) can bind via various binding schemes. In a monodentate binding mode, a single carboxylate group from the citrate molecule connects with a zinc atom on the NP’s surface. In contrast, bidentate binding involves a carboxylate group forming two bonds with the surface. Additionally, there is the chelating scheme, where multiple atoms from the citrate molecule coordinate with one or several zinc atoms on the surface of the NPs. Among these, chelation is the most preferred due to its ability to greatly enhance the binding strength and stability of the NPs. Figure 7 illustrates all three binding schemes. They can slow down Oswald repining, as well as aggregation and agglomeration.

4.4 TEM

TEM was performed on ZnO NPs stabilized with citric acid to analyze their size and size distribution in detail. The TEM images indicate a range of particle sizes from 1.5 to 6 nm. To quantify the distribution, a histogram of the measured NP sizes was plotted. A log-normal distribution was fitted to the data, providing a precise characterization of the size variation within the sample. The analysis revealed that the mean size of the particles is 3.06 nm, with a standard deviation of 0.253 nm. This suggests a relatively narrow size distribution, indicating good control over the synthesis process. The resulting size distribution and log-normal fit are visually represented in Figure 9. This highlights the uniformity and consistency of the NP sizes within the sample. These results are in close agreement with the findings obtained from XRD data refinement.

TEM images of the ZnO NPs stabilized with cit at different scales: (a) at 20 nm, (b) at 5 nm, and the corresponding histogram (c).

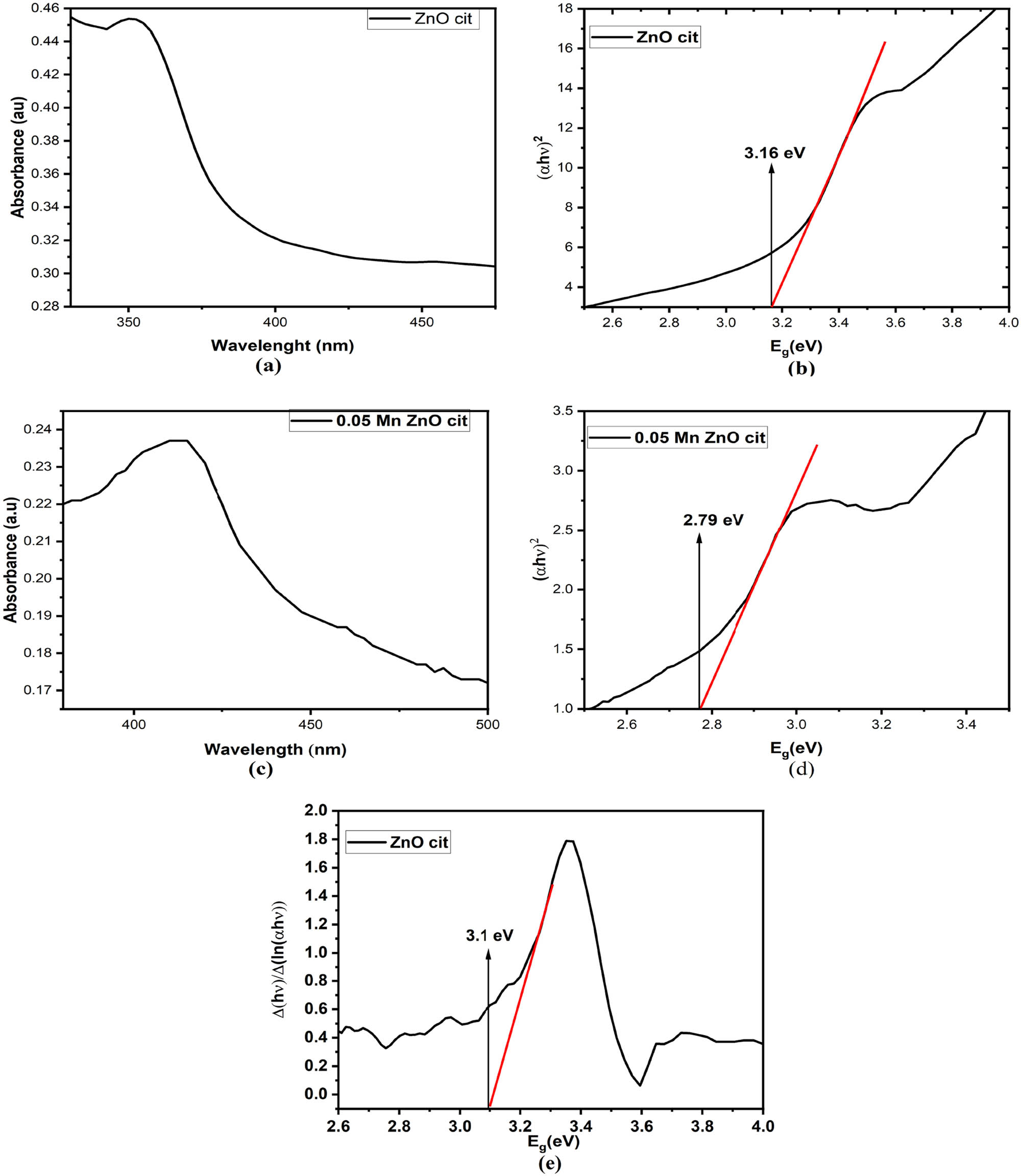

4.5 UV-Vis spectroscopy

The optical and electronic properties of ZnO NPs stabilized with cit are explored using UV-Vis spectroscopy. A broad absorption peak in the range of 347–355 nm was observed, corresponding to hexagonal wurtzite ZnO [60]. The results are in close agreement with the findings by Davis et al. [61], as depicted in Figure 10. A blue shift compared to the absorption peak of bulk ZnO is observed, attributed to quantum confinement and the Burstein–Moss effect, which typically emerges at the nanoscale. The broadening of the absorption peak might be due to the size distribution and the presence of citrate molecules on the surface. A direct bandgap (E g) (n = 2) ranging from 3.1 to 3.16 eV is obtained using Tauc’s (Eq. 6) and inverse logarithmic derivative method (Eq. 7) [62], as shown in Figure 10:

UV-Vis absorption spectrum of (a) pure ZnO nanoparticles (NPs) stabilized with citrate and (c) Mn-doped ZnO NPs stabilized with citrate; corresponding optical bandgap (b) for pure ZnO and (d) for Mn-doped ZnO NPs using the Tauc’s relation; and (e) bandgap of ZnO NPs stabilized with citrate using the inverse logarithmic derivative method.

Here,

Mn doping introduces a red shift in the absorption peak, indicating a decrease in optical bandgap to about 2.79 eV, as shown in Figure 10. Mn doping introduces new electronic states. Moreover, Mn ion incorporation into the ZnO lattice induces lattice strain, further influencing the optical properties.

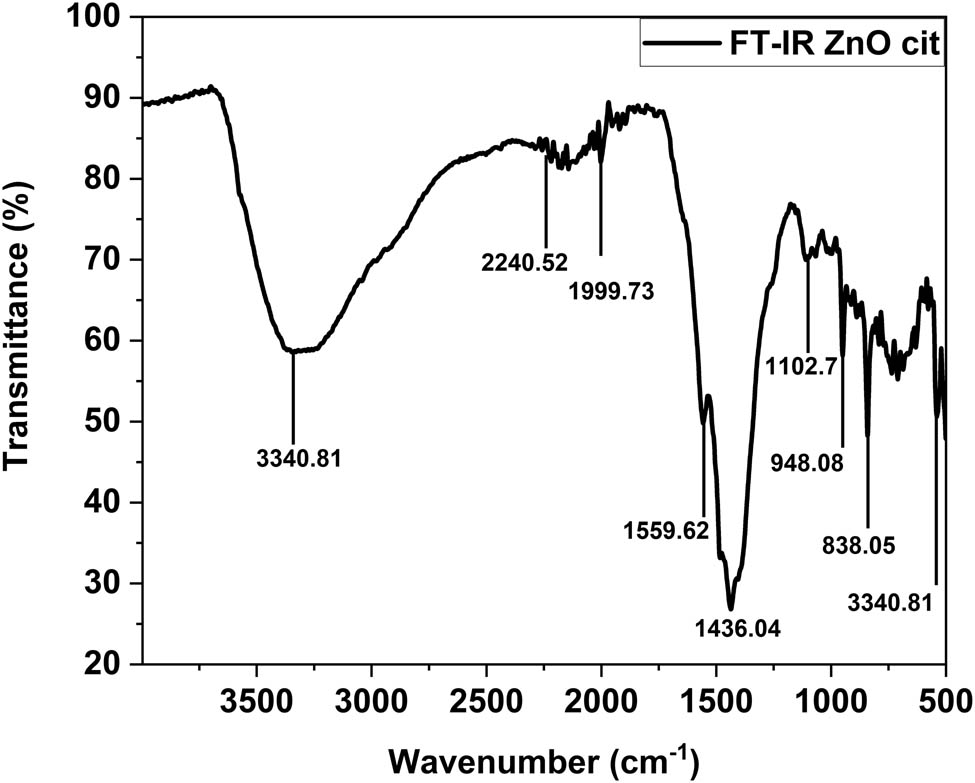

4.6 FT-IR spectroscopy

Various functional groups attached to the surface of ZnO NPs stabilized with citrate molecules were confirmed through FT-IR spectroscopy, as shown in Figure 11. Many absorption bands were observed at 838.05, 948.08, 1,102.76, 1,436.04, 1,559.62, 1,999.73, 2,240.52, and 3,340.81

FT-IR spectroscopy of ZnO NPs.

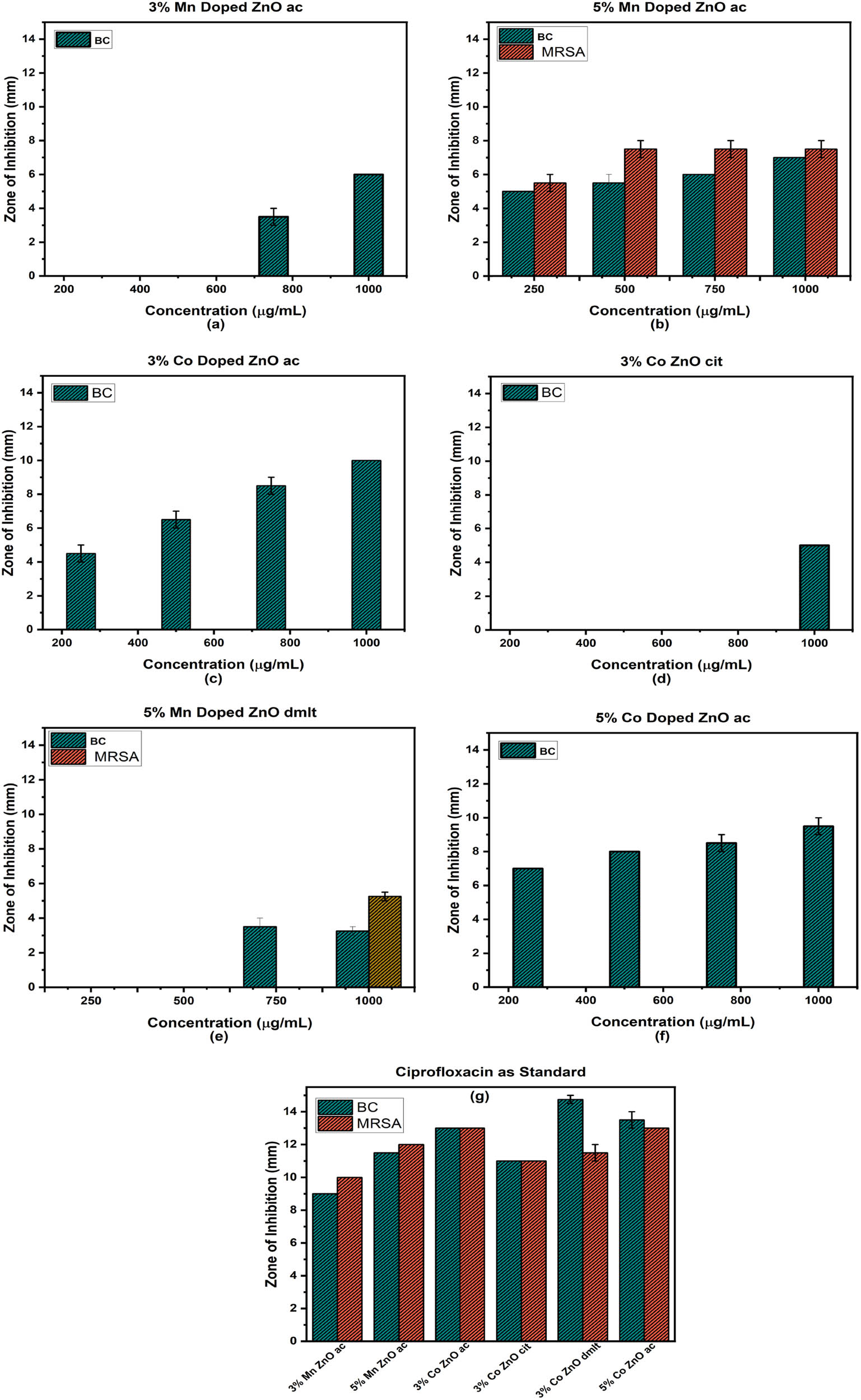

4.7 Antimicrobial activity

The antibacterial activities of all synthesized samples, including the ZnO NPs, 3% and 5% Mn, Co, and 3% Al-doped ZnO NPs, as well as the standard drug ciprofloxacin, were explored against Gram-positive bacteria MRSA and BC. ZnO NPs stabilized with various ligand molecules showed no activity. The 3% Mn-doped ZnO NPs with ac molecules show a 3.5 ± 0.5 mm zone of inhibition at 750 μg·mL−1 concentration and increases to 6 ± 0.0 mm at 1,000 μg·mL−1 in a dose-dependent mode against BC and remains inactive against MRSA. Upon increasing the doping concentration from 3 to 5%, the sample becomes active against both strains even at the lowest concentration of 250 μg·mL−1, producing zones of inhibition of 5.5 ± 0.5 mm and 5 ± 0 mm against MRSA and BC, respectively. Interestingly, the zone of inhibition (7.5 ± 0.5 mm) did not grow after 500 μg·mL−1 concentration against MRSA. Dose-dependent activities are observed against BC. At 500, 750, and 1,000 μg·mL−1 concentrations, the observed zones of inhibition are 6 ± 0, 7 ± 0, and 7 ± 0 mm against BC. The same trend was observed for the Co-doped ZnO NPs. 3% Co-doped ZnO NPs with ac and cit molecules as stabilizers were active against BC even at the lowest concentration of 250 μg·mL−1. The results are shown in Figure 12. 3% Co-doped ZnO stabilized with dmlt shows activity against BC at 750 μg·mL−1 and MRSA at 1,000 μg·mL−1 concentration. 5% Co-doped ZnO with ac molecule as stabilizers were active against BC for all concentrations. This might be due to the generation of metal ions, Zn2+, Mn2+, and Co2+. Interaction of metal ions with various functional groups within bacterial cells can lead to disturbance in normal metabolic processes and disruption of biomolecule functions. Moreover, the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) can contribute to oxidative stress, eventually leading to bacteriolysis. Research is ongoing to understand the exact mechanism.

Zone of inhibition of gram-positive bacteria when treated with doped ZnO NPs (a)–(f), and Zone of inhibition for the standard drug ciprofloxacin (g).

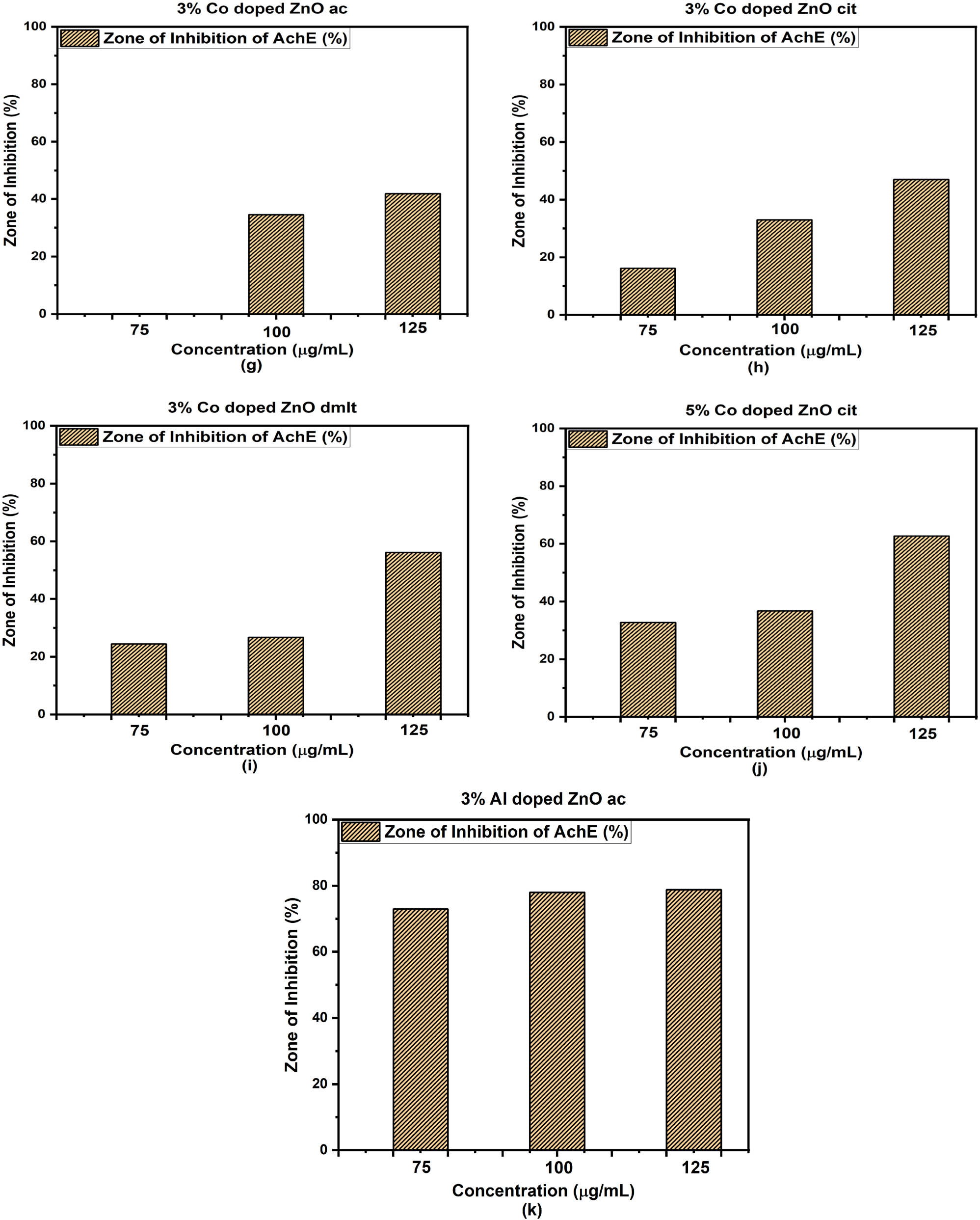

4.8 Anti-AChE activity

Many people worldwide are suffering from AD. AD leads to various consequences, including a decline in cognitive abilities. Several approaches have been developed to combat AD. Research is ongoing to find a suitable remedy. Cholinesterase enzyme inhibitors, such as Donepezil, Galantamine, and Rivastigmine, are available. We explore the anti-AChE assay of the synthesized samples. The percentage inhibition was measured at various concentrations (75, 100, 125 μg·mL−1). Pure ZnO stabilized with pent and dmlt showed the highest zones of inhibition of 87.39 ± 0.002% and 71.5 ± 0.02% at 125 μg·mL−1 concentration. Among doped samples, 3% Al-doped ZnO stabilized with acetate molecules showed a 78.8 ± 0.017% zone of inhibition at the highest concentration, and 5% Co-doped ZnO with citrate molecules as stabilizers showed 62.7 ± 0.051% inhibition at the highest concentration. All other doped samples showed intermediate zones of inhibition, as depicted in Figure 13. All samples follow the dose-dependent activities. The results confirmed that the direct interaction of ligand molecules with enzymes or the provision of an unfavorable environment for enzyme activity contributes to the observed inhibition.

Zone of inhibition against acetylcholinesterase enzyme (AChE) of pure and doped ZnO stabilized with different ligand molecules (a)–(k).

Metal-doped samples provide additional metal ions, which might affect enzyme activity, while Al-doping significantly reduces AChE activity. The exact mechanism is still unknown and a fruitful debate. Many possibilities can arise; one possibility is the direct interaction, where the adsorption of NPs onto the enzyme surface due to electrostatic interactions or the metal ion binding to the specific residues on the AChE leads to disruption of the AChE activities [63]. In indirect interaction, exposure of NPs to biological environments can generate ROS, resulting in oxidative damage to the enzyme [64]. The utilization of ligand molecules as surfactants, specifically at the nanoscale, alters surface properties [65]. They can directly affect enzymatic activity; for instance, the interaction of citrate molecules can result in the formation of complexes with certain amino acid residues on the enzyme, affecting AChE activity.

3% Mn-doped ZnO NPs stabilized with ac showed significant antimicrobial activity against BC and MRSA in a dose-dependent mode. However, for MRSA, higher concentrations did not show proportional increases in activity, likely due to NPs settling. ZnO stabilized with pent and 3% Al-doped ZnO stabilized with ac exhibit the highest activities against AChE, as listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Comparison of antimicrobial activities of doped ZnO NPs

| Sample | Pathogen type | Concentration | Zone of inhibition (mm) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3% Mn-doped ZnO ac | BC | 750 μg·mL−1 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | This work |

| 3% Mn-doped ZnO ac | BC | 1,000 μg·mL−1 | 6 ± 0.0 | This work |

| 5% Mn-doped ZnO ac | MRSA | 250 μg·mL−1 | 5.5 ± 0.5 | This work |

| 5% Mn-doped ZnO ac | BC | 250 μg·mL−1 | 5 ± 0.0 | This work |

| 5% Mn-doped ZnO ac | MRSA | 500 μg·mL−1 | 7.5 ± 0.5 | This work |

| 2.5% Mn-doped ZnO | BC | 2 mM | 2.2 | [66] |

| 2.5% Mn-doped ZnO | BC | 2 mM | 3 | [66] |

MRSA = methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and BC = Bacillus cereus.

Comparison of enzyme inhibition activity of ZnO, Al-doped, and AgNO3 HP-Ag NPs

| Sample | Enzyme | Concentration | Zone of inhibition (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO pent | AChE | 75 μg·mL−1 | 82.8 ± 0.01 | This work |

| ZnO dmlt | AChE | 75 μg·mL−1 | 34.7 ± 0.005 | This work |

| 3% Al-doped ZnO | AChE | 75 μg·mL−1 | 72.9 ± 0.027 | This work |

| AgNO3 | AChE | 75 μg·mL−1 | 24.57 ± 1.48 | [67] |

| HP-Ag NPs | AChE | 74 mM | 60.10 ± 2.60 | [67] |

AChE = acetylcholinesterase enzyme, HP = Hypecoum pendulum (plant), Ag = silver, NPs = nanoparticles. Mn = manganese, pent = 1, 5-diphenyl-1,3,5-pentanetrione, and dmlt = dimethyl-l-tartrate.

5 Conclusions

The potential of nanomaterials has been vastly explored. We synthesized ZnO and doped ZnO ultra-small NPs decorated with different organic ligand molecules as stabilizers via the sol–gel method and characterized them using various characterization techniques. XRD reveals the impact of ligand molecules on the size, shape, and morphology of the synthesized NPs. UV-Vis spectroscopy shows a broad absorption peak in the range of 347–355 nm, corresponding to a bandgap of 3.1–3.11 eV. The presence of various functional groups is verified through FT-IR. Various doped samples show dose-dependent activities against MRSA and BC. Furthermore, the synthesized US-NPs were tested against AChE activities. The findings provide compelling insights with important implications for the treatment of AD. The inhibitory effects observed during analysis highlight the potential of these NPs in targeting AChE. The results of the study rank these NPs as candidates of considerable therapeutic value. The unique properties introduced by doping elements enhance their ability to interact with AChE. These findings encourage further research in the field of nanomedicine.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2024R1035), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Imran Ullah (IU): experimental work, characterization, writing original draft. Reinhard B. Neder (RBN): conceptualization, investigation, and supervision. Abdul Qadir Khan (AQK): pharmacological screening. Mushtaq Ahmad (MA): experimental work. Abdur Rauf (AR): analysis and data curation. Abdulrahman Alshammari (AA): analysis and investigation. Norah Abdullah Albekairi (NAA): biological studies.

-

Conflict of interest: The contact author, Dr. Abdur Rauf, is the associated editor of GPS. The other authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Richard PF. There’s plenty of room at the bottom. Feynman Comput. 2018;63:76.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Douglas SP, Mrig S, Knapp CE. Mods vs. nps: Vying for the future of printed electronics. Chem A Eur J. 2021;27(31):8062–81.10.1002/chem.202004860Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Yousef BA, Elsaid K, Abdelkareem MA. Potential of nanoparticles in solar thermal energy storage. Therm Sci Eng Prog. 2021;25:101003.10.1016/j.tsep.2021.101003Search in Google Scholar

[4] Fathi-Achachelouei M, Knopf-Marques H, Ribeiro da Silva CE, Barthès J, Bat E, Tezcaner A. Use of nanoparticles in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology. 2019;7:113.10.3389/fbioe.2019.00113Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Khan Y, Sadia H, Ali Shah SZ, Khan MN, Shah AA, Ullah N, et al. Classi_cation, synthetic, and characterization approaches to nanoparticles, and their applications in various fields of nanotechnology: A review. Catalysts. 2022;12(11):1386.10.3390/catal12111386Search in Google Scholar

[6] Sajanlal PR, Sreeprasad TS, Samal AK, Pradeep T. Anisotropic nanomaterials: structure, growth, assembly, and functions. Nano Rev. 2011;2(1):5883.10.3402/nano.v2i0.5883Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Rane AV, Kanny K, Abitha VK, Thomas S. Methods for synthesis of nanoparticles and fabrication of nanocomposites. Synthesis of inorganic nanomaterials. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2018. p. 121–39.10.1016/B978-0-08-101975-7.00005-1Search in Google Scholar

[8] Ajeet K, Chandra KD. Methods for characterization of nanoparticles. Advances in nanomedicine for the delivery of therapeutic nucleic acids. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2017. p. 43–58.10.1016/B978-0-08-100557-6.00003-1Search in Google Scholar

[9] Li R, Zheng K, Yuan C, Chen Z, Huang M. Be active or not: the relative contribution of active and passive tumor targeting of nanomaterials. Nanotheranostics. 2017;1(4):346.10.7150/ntno.19380Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Emil R. Size matters: why nanomaterials are di_erent. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35(7):583–92.10.1039/b502142cSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Choi K, Kang T, Oh SG. Preparation of disk shaped zno particles using surfactant and their pl properties. Mater Lett. 2012;75:240–3.10.1016/j.matlet.2012.02.031Search in Google Scholar

[12] Neder RB, Korsunskiy VI, Chory C, Müller G, Hofmann A, Dembski S, et al. Structural characterization of ii-vi semiconductor nanoparticles. Phys Status Solidi C. 2007;4(9):3221–33.10.1002/pssc.200775409Search in Google Scholar

[13] Neder RB, Fischer M. Local structure of zno nanoparticles.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Zobel M, Chatterjee H, Matveeva G, Kolb U, Neder RB. Room-temperature sol_gel synthesis of organic ligand-capped zno nanoparticles. J Nanopart Res. 2015;17:1–11.10.1007/s11051-015-3006-5Search in Google Scholar

[15] Meulenkamp EA. Synthesis and growth of zno nanoparticles. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102(29):5566–72.10.1021/jp980730hSearch in Google Scholar

[16] Hong R, Pan T, Qian J, Li H. Synthesis and surface modification of zno nanoparticles. Chem Eng J. 2006;119(2-3):71–81.10.1016/j.cej.2006.03.003Search in Google Scholar

[17] Ding K, Cullen DA, Zhang L, Cao Z, Roy AD, Ivanov IN, et al. A general synthesis approach for supported bimetallic nanoparticles via surface inorganometallic chemistry. Science. 2018;362(6414):560–4.10.1126/science.aau4414Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Abid N, Khan AM, Shujait S, Chaudhary K, Ikram M, Imran M, et al. Synthesis of nanomaterials using various top-down and bottom-up approaches, influencing factors, advantages, and disadvantages: A review. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2022;300:102597.10.1016/j.cis.2021.102597Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Riccò R, Nizzero S, Penna E, Meneghello A, Cretaio E. and Francesco Enrichi. Ultra-small dye-doped silica nanoparticles via modified sol-gel technique. J Nanopart Res. 2018;20:1–9.10.1007/s11051-018-4227-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Singh G, Ddungu JLZ, Licciardello N, Bergmann R, De Cola L, Stephan H. Ultrasmall silicon nanoparticles as a promising platform for multimodal imaging. Faraday Discuss. 2020;222:362–83.10.1039/C9FD00091GSearch in Google Scholar

[21] Mourdikoudis S, Pallares RM, Thanh NTK. Characterization techniques for nanoparticles: comparison and complementarity upon studying nanoparticle properties. Nanoscale. 2018;10(27):12871–934.10.1039/C8NR02278JSearch in Google Scholar

[22] Li L, Fernández-Cruz ML, Connolly M, Conde E, Fernández M, Schuster M, et al. The potentiation effect makes the difference: non-toxic concentrations of zno nanoparticles enhance cu nanoparticle toxicity in vitro. Sci Total Environ. 2015;505:253–60.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.10.020Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Hong TK, Tripathy N, Son HJ, Ha KT, Jeong HS, Hahn YB. A comprehensive in vitro and in vivo study of zno nanoparticles toxicity. J Mater Chem B. 2013;1(23):2985–92.10.1039/c3tb20251hSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Chavanpatil MD, Khdair A, Panyam J. Nanoparticles for cellular drug delivery: mechanisms and factors influencing delivery. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2006;6(9-10):2651–63.10.1166/jnn.2006.443Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Roney C, Kulkarni P, Arora V, Antich P, Bonte F, Wu A, et al. Targeted nanoparticles for drug delivery through the blood brain barrier for Alzheimer’s disease. J Controlled Rel. 2005;108(2-3):193–214.10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.07.024Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Ruiz-Hernandez E, Baeza A, Vallet-Regí M. Smart drug delivery through dna/magnetic nanoparticle gates. ACS Nano. 2011;5(2):1259–66.10.1021/nn1029229Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Rahman MM, Ahmed J, Asiri AM. Thiourea sensor development based on hydrothermally prepared cmo nanoparticles for environmental safety. Biosens Bioelectron. 2018;99:586–92.10.1016/j.bios.2017.08.039Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Rivas L, Mayorga-Martinez CC, Quesada-González D, Zamora-Gálvez A, De La Escosura-Muñiz A, Merkoçi A. Label-free impedimetric aptasensor for ochratoxin-a detection using iridium oxide nanoparticles. Anal Chem. 2015;87(10):5167–72.10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00890Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Ganguly P, Harb M, Cao Z, Cavallo L, Breen A, Dervin S, et al. 2d nanomaterials for photocatalytic hydrogen production. ACS Energy Lett. 2019;4(7):1687–709.10.1021/acsenergylett.9b00940Search in Google Scholar

[30] Nasr M, Eid C, Habchi R, Miele P, Bechelany M. Recent progress on titanium dioxide nanomaterials for photocatalytic applications. ChemSusChem. 2018;11(18):3023–47.10.1002/cssc.201800874Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Lee JS, Jang J. Hetero-structured semiconductor nanomaterials for photocatalytic applications. J Ind Eng Chem. 2014;20(2):363–71.10.1016/j.jiec.2013.11.050Search in Google Scholar

[32] Ramírez JI, Villegas VA, Sicairos SP, Guevara EH, Brito Perea MD, Sánchez BL. Synthesis and characterization of zinc peroxide nanoparticles for the photodegradation of nitrobenzene assisted by uv-light. Catalysts. 2020;10(9):1041.10.3390/catal10091041Search in Google Scholar

[33] Mustapha S, Ndamitso MM, Abdulkareem AS, Tijani JO, Shuaib DT, Ajala AO, et al. Application of TiO 2 and ZnO nanoparticles immobilized on clay in wastewater treatment: a review. Appl Water Sci. 2020;10:1–36.10.1007/s13201-019-1138-ySearch in Google Scholar

[34] Kumar R, Umar A, Kumar G, Nalwa HS. Antimicrobial properties of ZnO nanomaterials: A review. Ceram Int. 2017;43(5):3940–61.10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.12.062Search in Google Scholar

[35] Aftab S, Shabir T, Shah A, Nisar J, Shah I, Muhammad H, et al. Highly efficient visible light active doped ZnO photocatalysts for the treatment of wastewater contaminated with dyes and pathogens of emerging concern. Nanomaterials. 2022;12(3):486.10.3390/nano12030486Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] John Conly. Controlling antibiotic resistance by quelling the epidemic of overuse and misuse of antibiotics. Can Family Physician. 1998;44:1769.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Lee Ventola C. The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. Pharm therapeutics. 2015;40(4):277.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Friedman ND, Temkin E, Carmeli Y. The negative impact of antibiotic resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(5):416–22.10.1016/j.cmi.2015.12.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] World Health Organization. Global status report on the public health response to dementia. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Altun E, Aydogdu MO, Chung E, Ren G, Homer-Vanniasinkam S, Edirisinghe M. Metal-based nanoparticles for combating antibiotic resistance. Appl Phys Rev. 2021;8:041303.10.1063/5.0060299Search in Google Scholar

[41] Li X, Robinson SM, Gupta A, Saha K, Jiang Z, Moyano DF, et al. Functional gold nanoparticles as potent antimicrobial agents against multi-drugresistant bacteria. ACS Nano. 2014;8(10):10682–6.10.1021/nn5042625Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Sarker SR, Polash SA, Karim MN, Saha T, Dekiwadia C, Bansal V. Functionalized concave cube gold nanoparticles as potent antimicrobial agents against pathogenic bacteria. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2022;5(2):492–503.10.1021/acsabm.1c00902Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Mashwani ZU, Khan T, Khan MA, Nadhman A. Synthesis in plants and plant extracts of silver nanoparticles with potent antimicrobial properties: current status and future prospects. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99:9923–34.10.1007/s00253-015-6987-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] El-Shounya WA, Moawad M, Haider AS, Ali S, Nouh S. Antibacterial potential of a newly synthesized zinc peroxide nanoparticles (zno2-nps) to combat biofilm-producing multi-drug resistant pseudomonas aeruginosa. Egypt J Botany. 2019;59(3):657–66.10.21608/ejbo.2019.7062.1277Search in Google Scholar

[45] Huda NU, Ghneim HK, Fozia F, Ahmed M, Mushtaq N, Sher N, et al. Green synthesis of kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Green Process Synth. 2023;12(1):20230060.10.1515/gps-2023-0060Search in Google Scholar

[46] Tripathi S, Pathak S, Kale A. Nanoparticles as artifcial chaperons suppressing protein aggregation: Remedy in neurodegenerative diseases. In: Sarma H, Joshi SJ, Prasad R, Jampilek J, editors. Biobased nanotechnology for green applications. Nanotechnology in the life sciences. Cham: Springer; 2021. p. 311–38.10.1007/978-3-030-61985-5_12Search in Google Scholar

[47] Proffen T, Neder RB. Discus: A program for diffuse scattering and defect-structure simulation. J Appl Crystallography. 1997;30(2):171–5.10.1107/S002188989600934XSearch in Google Scholar

[48] Zhang GR, Xu BQ. Surprisingly strong effect of stabilizer on the properties of au nanoparticles and pt ^ au nanostructures in electrocatalysis. Nanoscale. 2010;2(12):2798–804.10.1039/c0nr00295jSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Naz G, Othaman Z, Shamsuddin M, Ghoshal SK. Aliquat 336 stabilized multi-faceted gold nanoparticles with minimal ligand density. Appl Surf Sci. 2016;363:74–82.10.1016/j.apsusc.2015.11.124Search in Google Scholar

[50] Dhand C, Dwivedi N, Loh XJ, Ying AN, Verma NK, Beuerman RW. Methods and strategies for the synthesis of diverse nanoparticles and their applications: a comprehensive overview. Rsc Adv. 2015;5(127):105003–37.10.1039/C5RA19388ESearch in Google Scholar

[51] Fu X, Cai J, Zhang X, Li WD, Ge H, Hu Y. Top-down fabrication of shape-controlled, monodisperse nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2018;132:169–87.10.1016/j.addr.2018.07.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] DiVece M. Using nanoparticles as a bottom-up approach to increase solar cell efficiency. KONA Powder Part J. 2019;36:72–87.10.14356/kona.2019005Search in Google Scholar

[53] Spanhel L, Anderson MA. Semiconductor clusters in the sol-gel process: quantized aggregation, gelation, and crystal growth in concentrated zinc oxide colloids. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113(8):2826–33.10.1021/ja00008a004Search in Google Scholar

[54] Wood A, Giersig M, Hilgendorff M, Vilas-Campos A, Liz-Marzán LM, Mulvaney P. Size e_ects in zno: the cluster to quantum dot transition. Aust J Chem. 2003;56(10):1051–7.10.1071/CH03120Search in Google Scholar

[55] Chory C, Neder RB, Korsunskiy VI, Niederdraenk F, Kumpf C, Umbach E, et al. In_uence of liquid-phase synthesis parameters on particle sizes and structural properties of nanocrystalline zno powders. Phys Status Solidi C. 2007;4(9):3260–9.10.1002/pssc.200775424Search in Google Scholar

[56] Vijayalakshmi Pai GA. Differential evolution. In: Neural networks, fuzzy systems and evolutionary algorithms: Synthesis and applications. Cham: Springer; 2017. p. 367.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Ahmed M, Rocha JB, Mazzanti CM, Hassan W, Morsch VM, Lúcia Loro V. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J Pharm Anal. 2016;6(2):71–9.10.1016/j.jpha.2015.11.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[58] Rocha J, Emanuelli T, Pereira M. Effects of early undernutrition on kinetic parameters of brain acetylcholinesterase from adult rats. Acta Neurobiol Exp. 1993;53:431–1.Search in Google Scholar

[59] Ahmed M, Rocha JB, Mazzanti CM, Hassan W, Morsch VM, Lúcia Loro V, et al. Comparative study of the inhibitory effect of antidepressants on cholinesterase activity in bungarus sindanus (krait) venom, human serum and rat striatum. J Enzyme Inhibition Med Chem. 2008;23(6):912–7.10.1080/14756360701809977Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[60] Wooten AJ, Werder DJ, Williams DJ, Casson JL, Hollingsworth JA. Solution- liquid- solid growth of ternary cu- in- se semiconductor nanowires from multiple-and single-source precursors. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(44):16177–88.10.1021/ja905730nSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] Davis K, Yarbrough R, Froeschle M, White J, Rathnayake H. Band gap engineered zinc oxide nanostructures via a sol gel synthesis of solvent driven shape-controlled crystal growth. RSC Adv. 2019;9(26):14638.10.1039/C9RA02091HSearch in Google Scholar

[62] Jarosińskia Ł, Pawlak J, Al-Ani SKJ. Inverse logarithmic derivative method for determining the energy gap and the type of electron transitions as an alternative to the tauc method. Opt Mater. 2019;88:667–73.10.1016/j.optmat.2018.12.041Search in Google Scholar

[63] Šinko G, Vinković Vrček I, Goessler W, Leitinger G, Dijanošić A, Miljanić S. Alteration of cholinesterase activity as possible mechanism of silver nanoparticle toxicity. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2014;21:1391–400.10.1007/s11356-013-2016-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[64] Wang X, Li P, Ding Q, Wu C, Zhang W, Tang B. Observation of acetylcholinesterase in stress-induced depression phenotypes by two-photon fluorescence imaging in the mouse brain. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141(5):2061–8.10.1021/jacs.8b11414Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] Javed R, Zia M, Naz S, Aisida SO, Ain NU, Ao Q. Role of capping agents in the application of nanoparticles in biomedicine and environmental remediation: recent trends and future prospects. J Nanobiotechnology. 2020;18:1–15.10.1186/s12951-020-00704-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[66] Mesaros A, Vasile BS, Toloman D, Pop OL, Marinca T, Unguresan M, et al. Towards understanding the enhancement of antibacterial activity in manganese doped ZnO nanoparticles. Appl Surf Sci. 2019;471:960–72.10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.12.086Search in Google Scholar

[67] Sher N, Ahmed M, Mushtaq N, Khan RA. Synthesis of biogenic silver nanoparticles from the extract of Heliotropium eichwaldi L. and their effect as antioxidant, antidiabetic, and anti-cholinesterase. Appl Organomet Chem. 2023;37(2):e6950.10.1002/aoc.6950Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles