Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

-

Heba Fathy Abd-Elkhalek

Abstract

Some of the significant globally prevalent vector-borne illnesses are caused by Culex pipiens. Synthetic pesticides have been widely utilized to eradicate C. pipiens, which has led to a number of health risks for people, insect resistance, and environmental contamination. Alternative strategies are therefore vitally needed. In the current investigation, the Trichoderma viride fungal culture filtrate was used to create selenium and silver nanoparticles (SeNPs and AgNPs, respectively) and test them on C. pipiens larvae in their fourth instar stage. The death rate increased significantly when SeNP and AgNP concentrations increased, according to the results. SeNPs and AgNPs significantly affected the developmental and detoxification enzymes in fourth instar larvae of C. pipiens at 24 h after being treated with the sublethal concentration of the tested NPs. As a result of their insecticidal effect on C. pipiens larvae, SeNPs and AgNPs are considered effective and promising larvicidal agents.

1 Introduction

Egypt has a large population of C. pipiens, which is thought to be a vector for a variety of illnesses such as filariasis, West Nile fever, and Rift Valley fever [1,2]. The current global plan to combat illnesses spread by mosquitoes includes controlling this vector [3]. The traditional class of insecticides has a number of significant drawbacks, including high dose per unit crop, drift risks, operational risks, and residues in the environment, plants, and marketable product, as well as an adverse impact on non-target vegetation and non-target species. In order to address the aforementioned gaps, they must be replaced with a different pest management method [4,5].

One effective approach to this is nanotechnology [6,7,8]. The use of environmentally friendly pesticides has drawn attention worldwide as a viable substitute. When the substance is prepared as nanoparticles, water solubility, dissolution rate, and diffusion uniformity are significantly increased upon administration without causing any chemical changes to the pesticide molecule [9]. The material’s saturation solubility is increased as the particle size is reduced to the nanoscale. The surface area dramatically increases once a large reduction in particle radii is accomplished by nanosizing, leading to considerably quicker dissolution [10].

The nanosilver (nano-Ag) particle is the most widely utilized nanoparticle (NP) [11,12,13]. Silver, zinc, copper, and titanium are the metals that are most frequently used as NPs [14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Researchers interested in nanotechnology like AgNPs because they have antibacterial and antiviral properties [21,22,23]. Their predilection is heightened by their low toxicity, intrinsic charge, greater surface area, and crystalline structure [24]. In a certain quantity, selenium (Se) is an essential element for individuals, plants, and animals. This element plays a crucial part in how plants normally function, protecting them from a variety of stressors [25,26]. Due to their effectiveness in reducing a number of biotic and abiotic stresses, such as metals, salt, dryness, and warmth, as well as their capacity to inhibit phytopathogenic microorganisms, Se particles in the nanometer scale (SeNPs) have recently attracted increasing interest, especially for plants [27]. Clausena dentata leaf extracts were used in the effective green production of SeNPs. The NPs were shown to have potent mosquito larvicidal action in a dosedependent manner when applied at extremely low concentrations [28]. They can be utilized for making the pesticide formulation. In order to minimize the loss of water from the organism’s tissues and avoid death from dryness, insect body walls include a variety of lipids in their cuticle. Insects die as a result of a NP being absorbed in the lipids of the coat by abrasion [29]. Trichoderma viride is a highly effective biocontrol agent due to its multienzyme production capacity [30]. This fungus, T. viride, grows quickly, is not harmful to humans, and is safe for the environment. For large-scale manufacturing, the synthesis of NPs using the T. viride extract is a suitable and straightforward procedure [31]. Herein, this study aimed to biosynthesize both AgNPs and SeNPs using T. viride filtrate through a green and ecofriendly method for the first time. Characterizations of biosynthesized AgNPs and SeNPs were done using different techniques. Finally, the toxic effect of SeNPs and AgNPs on the tissues of the fourth instar larvae of C. pipiens was examined and clarified with regard to the protein content and the activity of developmental and detoxification enzymes and proposed as promising agents for killing larvae.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 C. pipiens laboratory rearing

The Entomology Dept, Faculty of Science, Benha University provided the C. pipiens for this study. In the insectary, they were kept at 27°C, 75% RH, and a photoperiod of 14 h light/10 h dark. The ratio of ground bread to fish food (TetraMin) for larvae was 3:1. The developed pupae were then transferred from the porcelain pans to a cup of water (dechlorinated) and put in examined cages (35 cm × 35 cm × 40 cm) where the adults eventually emerged. Female mosquitoes were occasionally fed, while the adult colony was given a 10% sugar solution. The same laboratory settings and continuous access to the fourth instar larvae were maintained during the study [32].

2.2 Biosynthesis of AgNPs and SeNPs using Trichoderma viride filtrate

Trichoderma viride filtrate was used in the production of AgNPs and SeNPs because it is a safe biological method, inexpensive, non-toxic, and environmentally friendly. The 2 mM AgNO3 and Na2SeO3 were separately added to the T. viride filtrate and incubated, and their pH was subsequently adjusted to 9 and 6 to obtain AgNPs and SeNPs, respectively. Following incubation, AgNPs and SeNPs became brown and red, respectively. The final product was separated and dried at 90°C for 24 h.

2.3 Characterization of Se and AgNPs

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of AgNPs and SeNPs were obtained by an X-ray diffractometer with an X-ray source (Cu Kα; λ = 1.54178 Å). At the Faculty of Science, Benha University, FT-IR spectra of the as-prepared AgNPs and SeNPs were recorded using KBr pellets with a Thermo Scientific NicoletiS10 FT-IR spectrometer in the 4,000–400 cm−1 range. The as-prepared AgNPs and SeNPs were photographed using a transmission electron microscope (JEOL-JEM 2100).

2.4 Larvicidal bioassay activity

Under controlled laboratory conditions, two batches of AgNPs and SeNPs were evaluated on C. pipiens larvae in their fourth instar stage. In order to obtain different concentrations, 1 mL of Se or AgNPs was evenly scattered over 1,000 mL of DW using an ultrasonicator. At doses of 30, 50, and 70 ppm, fourth instar larvae were used to investigate the toxicity of Se and AgNPs. Transferring 20 larvae per concentration into a glass beaker with 250 mL of DW was the standard procedure for all tests. The experiment was run three times in comparison to a group that did not receive any nanomaterial treatment, and after the instar larvae were exposed to the treatments for 24 h, the mortality % was noted [33]. Biochemical analyses were carried out at non-kill concentrations of SeNPs or AgNPs.

2.5 Preparation of AgNPs and SeNPs for biochemical analysis

About 0.5–1 g of fourth-instar larvae equivalent to the weight of 100 larvae was taken from the handled larvae at a sublethal dose of the tested AgNPs and SeNPs and stored at −25°C for no longer than a week in order to undergo the biochemical test for assessing the detoxifying enzymes and protein in the body of larvae. Similar settings were used for untreated larvae. For biochemical examination, all samples were transported in ice boxes (−20°C) to the Central Lab of the College of Veterinary Medicine.

2.5.1 Total proteins

Bradford’s technique [34] was used to calculate the total amount of proteins. The protein reagent was made by combining 50 mL of 95% ethanol with 100 mg of Coomassie brilliant blue G-250. About 100 mL of 85% (w/v) phosphoric acid was added to this solution. A final volume of 1 L was achieved by diluting the obtained solution. Phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.6) was used to make up the test tube’s volume to 1 mL. The test tube was filled with 5 mL of protein reagent, and the mixture was stirred by vortexing. After 2 min and before 1 h, the absorption value at 595 nm was calculated in comparison to a blank made from 1 mL of phosphate buffer and 5 mL of protein solution.

2.5.2 Glutathione stransferase (GST)

The technique of Habig et al. [35] was used to detect the conjugate, S-(2,4dinitrophenyl)-l-glutathione. The mixture contained 200 µL of larval homogenate, 100 µL of GSH, and 1 mL of potassium (K) salt of a phosphate buffer (pH 6.5). About 25 µL of CDNB substrate solution was added to the reaction to begin the process. CDNB and GSH concentrations were 1 and 5 mM, respectively. For 5 min, enzymes and chemicals were left to incubate at 30°C. The nanomolar substrate-conjugated/min/larva was recognized as a molar extinction coefficient of 9.6·mM−1·cm−1, and the increase in absorbance at 340 nm was measured against a blank including all the components without the enzyme.

2.5.3 Quantitative determination of peroxidase

According to the method described by Hammerschmidt et al. [36], the peroxidase activity was assessed. About 1.5 mL of pyrogallol (0.05 M) and 100 µL of enzyme extract were added to a spectrometer sample cuvette. At 420 nm, the measurements were reset to zero. About 100 µL of hydrogen peroxide (1%) was poured into the specimen’s cuvette to start the reaction. The shift in absorbance·min−1·g−1 sample was used to express the activity of the enzyme.

2.5.4 Determination of phosphatases

The Powell and Smith technique [37] was used to measure acidic and alkali phosphatases. In this process, 4aminoantipyrine reacts with phenol generated by disodium phenyl phosphate’s enzymatic hydrolysis and gives a distinctive brown color when added with potassium ferricyanide. The amount of pnitrophenyl phosphate that an enzyme can hydrolyze in 1 min at 37°C at a pH of 10.4 for alkali phosphatase and 4.8 for acidic phosphatase is measured in units (U).

2.5.5 Nonspecific esterases

Using naphthyl acetate as the substrate, beta esterases (βesterases) and alpha esterases (αesterases) were identified in accordance with Van Asperen [38]. The chemical mixture contained 20 mL of larval homogenate and 5 mL of substrate solution (3 × 10−4 M or naphthyl acetate, 1% acetone, and 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7). About 1 mL of diazo blue color reagent (made by combining two parts of 1% diazo blue B and five parts of 5% sodium lauryl sulfate) was added after the mixture had been incubated at 27°C for exactly 15 min. For hydrolysis of the substrate to provide either α- or β-naphthol, the developed color was read at 600 or 555 nm, respectively. The typical curves for α- and β- naphthol were created by combining 20 mg of – or -naphthol with 100 mL of phosphate buffer (stock solution) to achieve pH 7. The buffer was used to dilute 10 mL of stock solution to 100 mL. Aliquots of diluted solution in amounts of 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, and 1.6 mL were transferred into testing tubes and made up to 5 mL with phosphate buffer. Following the addition of 1 mL of diazo blue reagent, the produced color was assessed as before.

2.6 Statistical analysis

The results of the susceptibility test were visually shown using a probit-log line for regression. The data were statistically analyzed using the probit analysis application (LdP Line). The biochemical analysis was performed using R version 4.2.1. P < 0.05 was used as the criteria of significance for each experiment.

3 Results

3.1 Characterization of Se and AgNPs

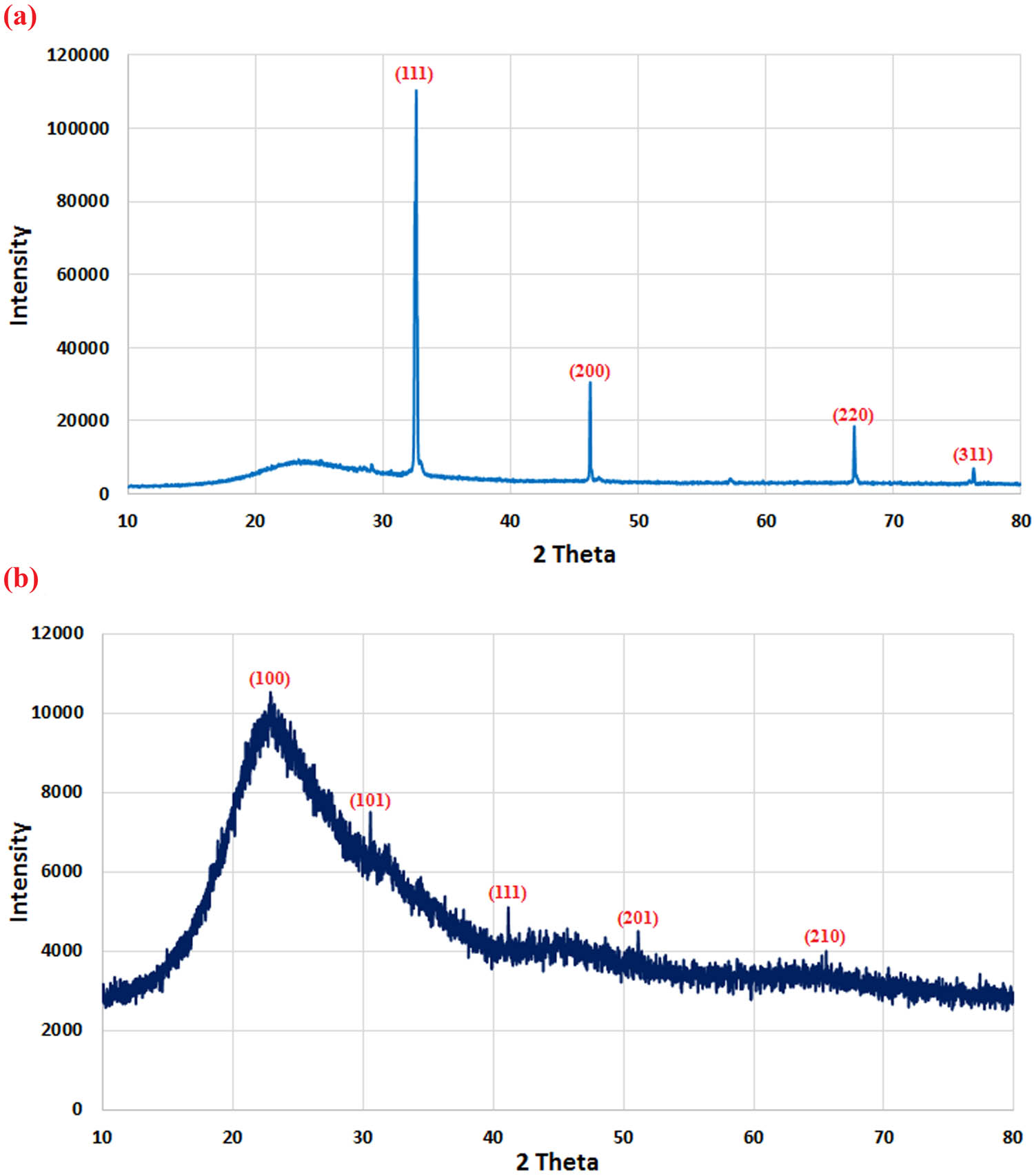

Figure 1 displays the XRD patterns of AgNPs and SeNPs. Characteristic distinct peaks can be seen in each spectrum. In AgNPs, four peaks appear at 2θ values of 32.5° (111), 46.1° (200), 66.8° (220), and 76.3° (311) (Figure 1a), while in the case of SeNPs the peaks are observed at 2θ values of 22.8° (100), 30.5° (101), 41.1° (111), 51.1° (201), and 65.5° (210) (Figure 1b).

XRD patterns of AgNPs (a) and SeNPs (b) biosynthesized by T. viride.

FTIR analysis was performed on samples of biologically synthesized AgNPs and SeNPs. The peaks for vibrations of N–H or O–H bonds are observed at 3,350–3,210 cm−1 in the FTIR spectra of AgNPs and SeNPs (Figure 2a and b). The potential link between these bands is attributed to the stretching vibration of C–H. It is convenient to identify the amide bands (I and II) of proteins or polypeptides around 1,638 cm−1. Peaks between 400 and 600 cm−1 are correlated with vibrations of the metalــoxygen bond. In the current study, the formation of AgNPs can be proved by the peaks observed around 420 and 470 cm−1 belonging to Ag–O. Moreover, a characteristic band is observed at 500 cm−1, attributed to Se–O.

FTIR spectra of AgNPs (a) and SeNPs (b) produced by T. viride.

The TEM image shows that AgNPs are well-dispersed and nearly spherical (Figure 3a). For AgNPs, the particle size is found to be in the range of 14.28–30.58 nm (Figure 3a). In contrast, NPs of Se are noticed to be spherical in shape with a size of 25.4–80.6 nm (Figure 3b).

TEM images of biosynthesized AgNPs (a) and SeNPs (b).

3.2 Larvicidal bioassay activity

It is clear from our results that SeNPs and AgNPs affect the percentage of observed larval mortality, increasing gradually with the increase of concentration. The estimated LC50 values, at 95% probability, were 39.2 and 52 ppm for larvae treated with SeNPs and AgNPs, respectively after 24 h (Table 1).

Toxicity of SeNPs and AgNPs on fourth instar larvae of C. pipiens at different concentrations after 24 h

| Product | Concentration (ppm) | Mean of mortality (%) |

|---|---|---|

| SeNPs | Control | 0 |

| 30 | 36.667 ± 0.94 | |

| 50 | 63. 333 ± 0.47 | |

| 70 | 80.000 ± 0.82 | |

| AgNPs | Control | 0 |

| 30 | 16.667 ± 0.94 | |

| 50 | 46.667 ± 1.88 | |

| 70 | 70.000 ± 0.00 |

3.3 Biochemical studies

The information in Table 2 demonstrates the developmental and detoxifying enzyme activity in C. pipiens larvae in their fourth instar stage at 24 h after exposure to the non-killing concentration of the investigated NPs.

Developmental and detoxifying enzymes in C. pipiens larvae in their fourth instar

| Protein | Acid phosphatase | Alkaline phosphatase | Alpha esterase | Beta esterase | GST | Peroxidase | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 55.12a ± 1.20 | 62.0333a ± 2.89 | 190.333a ± 5.62 | 99.6667a ± 3.54 | 36.2a ± 8.32 | 1,989.33a ± 6.21 | 9.34000a ± 7.58 |

| SeNPs | 46.52b ± 2.30 | 53.4000b ± 6.25 | 97.333b ± 2.63 | 60.3333b ± 2.65 | 25.7b ± 4.36 | 1,080.33b ± 6.87 | 8.96667a ± 5.69 |

| AgNPs | 47.60b ± 1.06 | 49.2333b ± 4.89 | 150b ± 7.01 | 91.3333a ± 1.85 | 37.5a ± 5.27 | 1,051.33b ± 4.56 | 8.23000a ± 1.56 |

Letters a and b revered to significant in statically analysis.

The SeNP data show that in treated larvae (developmental enzymes), there is a substantial reduction in the protein (total) content as well as alkaline and acid phosphatase enzyme activity. In addition, the activity of detoxification enzymes, such as GST, αesterase, and β-esterase, decreased significantly after treatment compared to the control. Insignificant effect was reported regarding peroxidase activity.

Regarding the effect of AgNPs on treated larvae, the amount of total protein and the activity of developmental enzymes, and GST decreased significantly. Meanwhile, α-esterase, β-esterase, and peroxidase showed insignificant change in activity. The outcomes of the larvicidal trials show that SeNP therapy is more successful than AgNPs in controlling mosquitoes.

4 Discussion

Despite the fact that a number of NPs have been successfully produced by biological agents such as bacteria and fungi, substantial challenges still remain [39,40,41]. Because the procedure is safe and natural capping agents are inexpensive, the biogenic production of NPs using fungal extracts has received a lot of attention [42,43]. The green synthesis of SeNPs and AgNPs using the T. viride extract involves the reduction of Se and Ag ions to elemental Se and Ag, respectively, by the metabolites present in the fungal extract. XRD analysis confirmed that the synthesized SeNPs and AgNPs were very pure and crystalline, with no evidence of an impurity peak. These specific peaks correspond to the reflections of the (100), (101), (111), (200), (201), (210), (220), and (311) planes of the phase of Ag and Se NPs. SeNPs displayed a wide peak at about 2θ = 20–23° with no sharp Bragg reflections, revealing the nature of SeNPs. Therefore, the XRD examination clearly shows that the formed AgNPs and SeNPs were crystalline. Green synthesis of SeNPs and AgNPs [44,45] has been described before, and the XRD pattern shown here is consistent with those reported earlier. FTIR analysis was used to analyze the chemical groups on the surface of green-synthesized AgNPs and SeNPs. It is possible to identify the components in the T. viride extract that are accountable for stabilizing and reducing the SeNPs and AgNPs. FTIR analysis was used in a number of investigations to describe green-synthesized AgNPs and SeNPs [46,47,48]. TEM examination demonstrated a strong distinction between the fungal extract-derived AgNPs and manufactured SeNPs. TEM images show that the great majority of NPs are spherical and evenly dispersed, which is consistent with earlier findings [23,49]. In the current study, the particle sizes of Se and Ag ranged between 25.4 and 80.6 nm and between 14.28 and 30.58 nm, respectively, which were prepared from the T. viride extract.

The successful management of several insect pests has been done in recent years, thanks to the application of nanotechnology in all disciplines, including pesticide preparations. Due to their low toxicity, environmental friendliness, and affordability, green-synthesized AgNPs are employed more frequently than other metal NPs [50,51]. The effective functionality group of a plant chemical embedded with an Ag ion-containing liquid during the reduction stage resulted in the formation of tiny size NPs, which is the mechanism of this green synthesis [52]. As a result of this tiny size, AgNPs are able to readily cross the cellular barrier of the insect, harm their inner cellular organelles, or interfere with their regular physiological processes, altering every organ system in turn, subsequently causing the death of the insect, according to some researchers [53]. The denaturation of DNA or sulfurcontaining proteins may be the cause of the SeNPs’ larvicidal activity. This process also results in the denaturation of structures and enzymes, which decreases the membrane’s permeability and inhibits ATP synthesis, both of which lead to the death of cells and the loss of cellular function [28].

Interestingly, poisoning may result from NPs entering the body via the exoskeleton [54]. According to a study, surface charge-modified NPs killed insects by dehydrating them after absorbing into their cuticular lipids [55]. To summarize, there are many different theories about NP toxicity, some of which attribute the toxicity to the factors that lead to oxidative damage in arthropods. [56].

In accordance with the findings provided by Koodalingam et al., the current results showed that the total protein content was reduced following treatment with LC50 concentration [57]. The total protein presumably reduced during insecticidal stress as a result of RNA loss and protein degradation into free amino acids [58]. In addition, a possible drop in hemolymph quantity brought on by insecticidal treatment may result in a decrease in the amount of total protein [59]. Protein deficiency might be a result of a physiological process that helps tissues and cells to adapt to insecticidal stressors [60].

Alkaline/acid phosphatases were found to be significantly reduced after treatment with AgNPs and SeNPs in comparison with the control samples. Notably, the consumption of any xenobiotic or toxic chemical that might alter the functioning of the lysosome could be the cause of this decrease in acid phosphatase lysosomal enzyme [61]. Alkaline phosphatase’s decrease might be ascribed to the binding of NPs to the gastrointestinal enzymes’ active site or to the decreased enzyme production [62], similar to the results reported by Durairaj et al. [63].

A vast and varied set of hydrolases known as general esterases hydrolyze a wide range of molecules, including esters and nonester chemicals. A number of investigations have shown that esterases are crucial in causing or assisting in the detoxification of insecticides in many insect and arthropod species. Esterases are hydrating enzymes that break down ester molecules when water is added, producing alcohol and acids [64]. The alpha and beta esterase activity in Culex pipiens fourth instar larvae showed nonsignificant change with the LC50 concentration of AgNPs and significant reduction with that of SeNPs. The effect of both spinetoram and rynaxypyr on αesterase and β-esterase activity in the total homogenate of Spodoptera littoralis fifth instar larvae was also demonstrated by El-Kawas et al. [65]. They found a significant reduction of 31.71% in αesterase activity and 11.18% in β-esterase activity. The earlier research likewise produced similar findings. The present study observed a widespread decline in enzyme activity, which may suggest that general esterases do not participate in the detoxification of rynaxypyr and spinetoram. These results concur with those of Fahmy and Dahi [66], who discovered that GST and esterases may not have a significant role in inhibiting the Spodoptera exigua field species.

GST is a vital key enzyme for determining whether an organism developed resistance or susceptibility after exposure to specific bioinsecticides. It has also been established that because this enzyme is highly abundant in a variety of insect pests, particularly mosquitoes, it is crucial for the detoxification process [67]. The GST enzyme expression was much lower in this study, which suggest that AgNPs and SeNPs may be engaged in the redox response and may cause harm due to oxidative stress to the tissues of larvae when they were exposed to NPs [68].

Data indicated that therapy with SeNPs rather than AgNPs significantly decreased the expression of enzymes associated with antioxidants and peroxidase. Our findings are consistent with those reported by Hussein et al. [69], who discovered that the application of SeNPs to several groundnut cultivars significantly reduced the activity of some antioxidant agents, including peroxidase. The authors hypothesized that selenium’s crucial function in detoxification, which resulted from oxidative stress, is responsible for the decline in antioxidant enzyme activity.

5 Conclusions

In conclusion, SeNPs and AgNPs were successfully synthesized from T. viride. The SeNPs and AgNPs were characterized by XRD, FTIR, and TEM. The NPs were shown to have substantial mosquito larvicidal action in a dose-dependent way when applied at extremely low concentrations. The outcomes of the larvicidal trials show that using SeNPs as a therapy is more efficient in controlling mosquitoes than AgNPs. The likelihood that next-generation NPs might be a more effective agent in controlling mosquitoes makes the current work important. Before marketing, more research is required to determine how the NPs affect nontarget living things and to evaluate their effectiveness in this field.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere thanks to the Faculty of science (Boyes), Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt, for providing the necessary research facilities. The authors would like to acknowledge the facilities available at the Faculty of Science, Benha University, Benha, Egypt. The authors extend their appreciation to the researchers supporting project number (RSP2024R505), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Funding information: The authors extend their appreciation to the researchers supporting project number (RSP2024R505), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contributions: Heba Fathy Abd-Elkhalek and Salem Salah Salem: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review and editing. Ali A. Badawy and Amr Hosny Hashem: methodology, writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review and editing. Abdulaziz A. Al-Askar and Hamada Abd Elgawad: writing – review and editing and funding acquisition.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Abdel-Hamid YM, Soliman MI, Kenawy MA. Population ecology of mosquitoes and the status of bancroftian filariasis in El Dakahlia Governorate, the Nile Delta, Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2013;43:103–13.10.12816/0006370Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Kenawy MA, Abdel-Hamid YM, Beier JC. Rift Valley Fever in Egypt and other African countries: Historical review, recent outbreaks and possibility of disease occurrence in Egypt. Acta Tropica. 2018;181:40–9.10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.01.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] World Health Organization. A global brief on vector-borne diseases (No. WHO/DCO/WHD/2014.1). World Health Organization; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[4] de Oliveira JL, Campos EVR, Bakshi M, Abhilash PC, Fraceto LF. Application of nanotechnology for the encapsulation of botanical insecticides for sustainable agriculture: Prospects and promises. Biotechnol Adv. 2014;32:1550–61.10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.10.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Salem SS, Fouda A. Green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles and their prospective biotechnological applications: an overview. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2021;199:344–70.10.1007/s12011-020-02138-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Salem SS. A mini review on green nanotechnology and its development in biological effects. Arch Microbiol. 2023;205:128.10.1007/s00203-023-03467-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Salem SS, Hammad EN, Mohamed AA, El-Dougdoug W. A comprehensive review of nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, characterization, and applications. Biointerface Res Appl Chem. 2023;13:1–30.10.33263/BRIAC131.041Search in Google Scholar

[8] Dezfuli AAZ, Abu-Elghait M, Salem SS. Recent insights into nanotechnology in colorectal cancer. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2023;1–5. 10.1007/s12010-023-04696-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Hashem AH, Selim TA, Alruhaili MH, Selim S, Alkhalifah DH, Al Jaouni SK, et al. Unveiling antimicrobial and insecticidal activities of biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using prickly pear peel waste. J Funct Biomater. 2022;13:1–12.10.3390/jfb13030112Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Sharma S, Loach N, Gupta S, Mohan L. Phyto-nanoemulsion: An emerging nano-insecticidal formulation. Environ Nanotechnol Monit Manag. 2020;14:100331.10.1016/j.enmm.2020.100331Search in Google Scholar

[11] Al-Rajhi AMH, Salem SS, Alharbi AA, Abdelghany TM. Ecofriendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Kei-apple (Dovyalis caffra) fruit and their efficacy against cancer cells and clinical pathogenic microorganisms. Arab J Chem. 2022;15:103927.10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.103927Search in Google Scholar

[12] Salem SS. Baker’s yeast-mediated silver nanoparticles: Characterisation and antimicrobial biogenic tool for suppressing pathogenic microbes. BioNanoScience. 2022;12:1220–9.10.1007/s12668-022-01026-5Search in Google Scholar

[13] Abu-Elghait M, Soliman MKY, Azab MS, Salem SS. Response surface methodology: Optimization of myco-synthesized gold and silver nanoparticles by Trichoderma saturnisporum. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2023;1–4. 10.1007/s13399-023-05188-4.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Said A, Abu-Elghait M, Atta HM, Salem SS. Antibacterial activity of green synthesized silver nanoparticles using Lawsonia inermis against common pathogens from urinary tract infection. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2024;196:85–98.10.1007/s12010-023-04482-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Abdelmoneim HEM, Wassel MA, Elfeky AS, Bendary SH, Awad MA, Salem SS, et al. Multiple applications of CdS/TiO2 nanocomposites synthesized via microwave-assisted sol–gel. J Clust Sci. 2022;33:1119–28.10.1007/s10876-021-02041-4Search in Google Scholar

[16] Al-Zahrani FAM, Salem SS, Al-Ghamdi HA, Nhari LM, Lin L, El-Shishtawy RM. Green synthesis and antibacterial activity of Ag/Fe2O3 nanocomposite using Buddleja lindleyana extract. Bioengineering. 2022;9:452.10.3390/bioengineering9090452Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Abdelghany TM, Al-Rajhi AMH, Yahya R, Bakri MM, Al Abboud MA, Yahya R, et al. Phytofabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles with advanced characterization and its antioxidant, anticancer, and antimicrobial activity against pathogenic microorganisms. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2023;13:417–30.10.1007/s13399-022-03412-1Search in Google Scholar

[18] Shehabeldine AM, Amin BH, Hagras FA, Ramadan AA, Kamel MR, Ahmed MA, et al. Potential Antimicrobial and antibiofilm properties of copper oxide nanoparticles: Time-kill kinetic essay and ultrastructure of pathogenic bacterial cells. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2023;195:467–85.10.1007/s12010-022-04120-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Hussein AS, Hashem AH, Salem SS. Mitigation of the hyperglycemic effect of streptozotocin-induced diabetes albino rats using biosynthesized copper oxide nanoparticles. Biomol Concepts. 2023;14:1–12.10.1515/bmc-2022-0037Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Salem SS, Soliman MKY, Azab MS, Abu-Elghait M. Optimization growth conditions of Fusarium pseudonygamai for myco-synthesized gold and silver nanoparticles using response surface methodology. BioNanoScience. 2024. 10.1007/s12668-024-01349-5.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Salem SS, EL-Belely EF, Niedbała G, Alnoman MM, Hassan SE, Eid AM, et al. Bactericidal and in-vitro cytotoxic efficacy of silver nanoparticles (Ag-NPs) fabricated by endophytic actinomycetes and their use as coating for the textile fabrics. Nanomaterials. 2020;10:2082.10.3390/nano10102082Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Sharaf MH, Nagiub AM, Salem SS, Kalaba MH, El Fakharany EM, Abd El-Wahab H. A new strategy to integrate silver nanowires with waterborne coating to improve their antimicrobial and antiviral properties. Pigm Resin Technol. 2023;52:490–501.10.1108/PRT-12-2021-0146Search in Google Scholar

[23] Salem SS, Ali OM, Reyad AM, Abd-Elsalam KA, Hashem AH. Pseudomonas indica-mediated silver nanoparticles: Antifungal and antioxidant biogenic tool for suppressing mucormycosis fungi. J Fungi. 2022;8:126.10.3390/jof8020126Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Alsharif SM, Salem SS, Abdel-Rahman MA, Fouda A, Eid AM, Hassan SE, et al. Multifunctional properties of spherical silver nanoparticles fabricated by different microbial taxa. Heliyon. 2020;6:1–13.10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03943Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Hashem AH, Abdelaziz AM, Attia MS, Salem SS. Selenium and nano-selenium-mediated biotic stress tolerance in plants. In: Hossain MA, Ahammed GJ, Kolbert Z, El-Ramady H, Islam T, Schiavon M, editors. Selenium and nano-selenium in environmental stress management and crop quality improvement. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 209–26.10.1007/978-3-031-07063-1_11Search in Google Scholar

[26] Feng R, Wei C. Antioxidative mechanisms on selenium accumulation in Pteris vittata L., a potential selenium phytoremediation plant. Plant Soil Environ. 2012;58:105–10.10.17221/162/2011-PSESearch in Google Scholar

[27] Ikram M, Raja NI, Javed B, Mashwani ZU, Hussain M, Hussain M, et al. Foliar applications of bio-fabricated selenium nanoparticles to improve the growth of wheat plants under drought stress. Green Process Synth. 2020;9:706–14.10.1515/gps-2020-0067Search in Google Scholar

[28] Sowndarya P, Ramkumar G, Shivakumar M. Green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles conjugated Clausena dentata plant leaf extract and their insecticidal potential against mosquito vectors. Artif cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2017;45:1490–5.10.1080/21691401.2016.1252383Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] El-Wahab A, El-Bendary H. Nano silica as a promising nano pesticide to control three different aphid species under semi-field conditions in Egypt. Egypt Acad J Biol Sci F Toxicol Pest Control. 2016;8:35–49.10.21608/eajbsf.2016.17117Search in Google Scholar

[30] John RP, Tyagi RD, Prévost D, Brar SK, Pouleur S, Surampalli RY. Mycoparasitic Trichoderma viride as a biocontrol agent against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. adzuki and Pythium arrhenomanes and as a growth promoter of soybean. Crop Prot. 2010;29:1452–9.10.1016/j.cropro.2010.08.004Search in Google Scholar

[31] Elgorban AM, Al-Rahmah AN, Sayed SR, Hirad A, Mostafa AA, Bahkali AH. Antimicrobial activity and green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2016;30:299–304.10.1080/13102818.2015.1133255Search in Google Scholar

[32] Baz MM, El-Barkey NM, Kamel AS, El-Khawaga AH, Nassar MY. Efficacy of porous silica nanostructure as an insecticide against filarial vector Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae. Int J Trop Insect Sci. 2022;42:2113–25.10.1007/s42690-022-00732-7Search in Google Scholar

[33] World Health Organization. Instructions for determining the susceptibility or resistance of mosquito larvae to insecticides (No. WHO/VBC/81.807). World Health Organization; 1981.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54.10.1006/abio.1976.9999Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Habig WH, Pabst MJ, Jakoby WB. Glutathione S-transferases: the first enzymatic step in mercapturic acid formation. J Biol Chem. 1974;249(22):7130–9.10.1016/S0021-9258(19)42083-8Search in Google Scholar

[36] Hammerschmidt R, Nuckles E, Kuć J. Association of enhanced peroxidase activity with induced systemic resistance of cucumber to Colletotrichum lagenarium. Physiol Plant Pathol. 1982;20:73–82.10.1016/0048-4059(82)90025-XSearch in Google Scholar

[37] Powell M, Smith M. The determination of serum acid and alkaline phosphatase activity with 4-aminoantipyrine (AAP). J Clin Pathol. 1954;7:245.10.1136/jcp.7.3.245Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Van Asperen K. A study of housefly esterases by means of a sensitive colorimetric method. J Insect Physiol. 1962;8(4):401–16.10.1016/0022-1910(62)90074-4Search in Google Scholar

[39] Salem SS. Application of Nano-materials. In: Raja R, Hemaiswarya S, Narayanan M, Kandasamy S, Jayappriyan KR, editors. Haematococcus: Biochemistry, biotechnology and biomedical applications. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2023. p. 149–63.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Salem SS, Mekky AE. Biogenic nanomaterials: Synthesis, characterization, and applications. In: Shah MP, Bharadvaja N, Kumar L, editors. Biogenic nanomaterials for environmental sustainability: Principles, practices, and opportunities. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2024. p. 13–43.10.1007/978-3-031-45956-6_2Search in Google Scholar

[41] Salem SS, Saied E, Shah MP. Chapter 5 – Advanced (nano)materials. In: Shah MP, Rodriguez-Couto S, editors. Development in wastewater treatment research and processes. Elsevier; 2024. p. 93–115.10.1016/B978-0-323-99278-7.00011-0Search in Google Scholar

[42] Shaheen TI, Salem SS, Fouda A. Current advances in fungal nanobiotechnology: Mycofabrication and applications. In: Lateef A, Gueguim-Kana EB, Dasgupta N, Ranjan S, editors. Microbial nanobiotechnology: Principles and applications. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2021. p. 113–43.10.1007/978-981-33-4777-9_4Search in Google Scholar

[43] Elkady FM, Hashem AH, Salem SS, El-Sayyad GS, Tawab AA, Alkherkhisy MM, et al. Unveiling biological activities of biosynthesized starch/silver-selenium nanocomposite using Cladosporium cladosporioides CBS 174.62. BMC Microbiol. 2024;24:78.10.1186/s12866-024-03228-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Salem SS. Bio-fabrication of selenium nanoparticles using Baker’s Yeast extract and its antimicrobial efficacy on food borne pathogens. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2022;194:1898–910.10.1007/s12010-022-03809-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Soliman MKY, Abu-Elghait M, Salem SS, Azab MS. Multifunctional properties of silver and gold nanoparticles synthesis by Fusarium pseudonygamai. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2022. 10.1007/s13399-022-03507-9.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Soliman MKY, Salem SS, Abu-Elghait M, Azab MS. Biosynthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles and their efficacy towards antibacterial, antibiofilm, cytotoxicity, and antioxidant activities. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2023;195:1158–83.10.1007/s12010-022-04199-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Hashem AH, Khalil AMA, Reyad AM, Salem SS. Biomedical applications of mycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Penicillium expansum ATTC 36200. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2021;199:3998–4008.10.1007/s12011-020-02506-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Elakraa AA, Salem SS, El-Sayyad GS, Attia MS. Cefotaxime incorporated bimetallic silver-selenium nanoparticles: promising antimicrobial synergism, antibiofilm activity, and bacterial membrane leakage reaction mechanism. RSC Adv. 2022;12:26603–19.10.1039/D2RA04717ASearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Hashem AH, Salem SS. Green and ecofriendly biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles using Urtica dioica (stinging nettle) leaf extract: Antimicrobial and anticancer activity. Biotechnol J. 2022;17:2100432.10.1002/biot.202100432Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Eid AM, Fouda A, Niedbała G, Hassan SE, Salem SS, Abdo AM, et al. Endophytic Streptomyces laurentii mediated green synthesis of Ag-NPs with antibacterial and anticancer properties for developing functional textile fabric properties. Antibiotics. 2020;9:641.10.3390/antibiotics9100641Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[51] Durán N, Durán M, Souza CE. Silver and silver chloride nanoparticles and their anti-tick activity: a mini review. J Braz Chem Soc. 2017;28:927–32.10.21577/0103-5053.20170045Search in Google Scholar

[52] Aref MS, Salem SS. Bio-callus synthesis of silver nanoparticles, characterization, and antibacterial activities via Cinnamomum camphora callus culture. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2020;27:101689.10.1016/j.bcab.2020.101689Search in Google Scholar

[53] Yasur J, Rani PU. Lepidopteran insect susceptibility to silver nanoparticles and measurement of changes in their growth, development and physiology. Chemosphere. 2015;124:92–102.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.11.029Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[54] Rai M, Kon K, Ingle A, Duran N, Galdiero S, Galdiero M. Broad-spectrum bioactivities of silver nanoparticles: the emerging trends and future prospects. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:1951–61.10.1007/s00253-013-5473-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[55] Benelli G. Mode of action of nanoparticles against insects. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;25:12329–41.10.1007/s11356-018-1850-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Imoisili PE, Ukoba KO, Jen T-C. Green technology extraction and characterisation of silica nanoparticles from palm kernel shell ash via sol–gel. J Mater Res Technol. 2020;9:307–13.10.1016/j.jmrt.2019.10.059Search in Google Scholar

[57] Koodalingam A, Mullainadhan P, Rajalakshmi A, Deepalakshmi R, Ammu M. Effect of a Bt-based product (Vectobar) on esterases and phosphatases from larvae of the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Pesticide Biochem Physiol. 2012;104:267–72.10.1016/j.pestbp.2012.09.008Search in Google Scholar

[58] Ali NS, Ali SS, Shakoori AR. Biochemical response of malathion-resistant and-susceptible adults of Rhyzopertha dominica to the sublethal doses of deltamethrin. Pak J Zool. 2014;46:853–61.Search in Google Scholar

[59] Sugumaran M. Chapter 5 – Chemistry of cuticular sclerotization. In: Simpson SJ, editor. Advances in insect physiology. Academic Press; 2010. p. 151–209.10.1016/B978-0-12-381387-9.00005-1Search in Google Scholar

[60] Sendi JJ, Khosravi R. Effect of neem pesticide (Achook) on midgut enzymatic activities and selected biochemical compounds in the hemolymph of lesser mulberry pyralid, Glyphodes pyloalis Walker (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). J Plant Prot Res. 2013;53(3):238–47. 10.2478/jppr-2013-0036Search in Google Scholar

[61] Shaurub E-SH, El-Aziz N. Biochemical effects of lambda-cyhalothrin and lufenuron on Culex pipiens L. (Diptera: Culicidae). Int J Mosq Res. 2015;2:122–6.Search in Google Scholar

[62] Shakoori A, Tufail N, Saleem M. Response of malathion-resistant and susceptible strains of Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) to bifenthrin toxicity. Pak J Zool. 1994;26:169.Search in Google Scholar

[63] Durairaj B, Xavier T, Muthu S. Research article fungal generated titanium dioxide nanoparticles: a potent mosquito (Aedes aegypti) larvicidal agent. Sch Acad J Biosci. 2014;2:651–8.Search in Google Scholar

[64] Rashwan MH. Biochemical impacts of rynaxypyr (Coragen) and spinetoram (Radiant) on Spodoptera littoralis (Boisd.). Nat Sci. 2013;11:40–7.Search in Google Scholar

[65] El-Kawas HM, Mead HM, Desuky WM. Field and biochemical studies of certain chitin synthesis inhibitors against Tetranychus urticae Koch and their side effects on some common predators. Bull Ent Soc Egypt, Econ Ser. 2009;35:171–88.Search in Google Scholar

[66] Fahmy NM, Dahi HF. Changes in detoxifying enzymes and carbohydrate metabolism associated with spinetoram in two field-collected strains of Spodoptera littoralis (Biosd.). Egypt Acad J Biol Sci F Toxicol Pest Control. 2009;1:17–26.10.21608/eajbsf.2009.17549Search in Google Scholar

[67] Parthiban E, Manivannan N, Ramanibai R, Mathivanan N. Green synthesis of silver-nanoparticles from Annona reticulata leaves aqueous extract and its mosquito larvicidal and anti-microbial activity on human pathogens. Biotechnol Rep. 2019;21:e00297.10.1016/j.btre.2018.e00297Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[68] Giordano G, Afsharinejad Z, Guizzetti M, Vitalone A, Kavanagh TJ, Costa LG. Organophosphorus insecticides chlorpyrifos and diazinon and oxidative stress in neuronal cells in a genetic model of glutathione deficiency. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;219:181–9.10.1016/j.taap.2006.09.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[69] Hussein H-AA, Darwesh OM, Mekki B. Environmentally friendly nano-selenium to improve antioxidant system and growth of groundnut cultivars under sandy soil conditions. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2019;18:101080.10.1016/j.bcab.2019.101080Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”