Abstract

The biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) is one of the methods used alongside other conventional methods for SeNP synthesis. In this research, we used the cell-free culture (CFC) of Limosilactobacillus fermentum for SeNP synthesis. We investigated the biosynthesis of SeNPs under various levels of temperature, pH, and Se4+ concentration and characterized the biosynthesized SeNPs using FE-SEM, energy-dispersive X-ray, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy (UV–Vis), and dynamic light scattering–zeta potential analyses to find nanoparticles with desirable properties. Also, the cellular toxicity of SeNPs against the MCF-7 cell line was analyzed. The scavenging activity of free radicals in CFC before and after SeNP synthesis was examined using the DPPH method. The selected SeNP has an average hydrodynamic radius of 92.52 nm and a polydispersity index of 0.134. This nanoparticle also has a mostly spherical shape, amorphous nature, and zeta potential of −32.2 mV. The toxicity of nanoparticles for MCF-7 was much lower than sodium selenite salt. It was also confirmed that during nanoparticle synthesis, the reducing ability of CFC significantly decreases. This research aimed to design a safe, cheap, and eco-friendly protocol for the biosynthesis of SeNPs using the CFC of Limosilactobacillus fermentum. As a result, SeNPs possess great potential for further exploration in the realm of biomedicine.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Nanotechnology is thought to be the next industrial revolution and is also expected to have a significant impact on society, the economy, and every aspect of life [1,2,3]. Nanoparticles can offer new ways to solve unresolved issues in industry, the environment, and medicine. Therefore, nanoparticles have been extensively studied and investigated in recent years [4]. The characterization of nanoparticles is of great importance to understanding their properties and applications. Size, dispersion, geometric shape, optical properties, crystallinity, and cellular toxicity are among the most critical specifications that help us choose different nanoparticles for specific applications [5].

The need for environmentally friendly and sustainable methods for nanoparticle production is crucial. Conventional chemical and physical synthesis methods often use hazardous chemicals, require high energy consumption, and can generate toxic byproducts [6,7]. Green nanotechnology, which utilizes biological resources for nanoparticle synthesis, offers a more sustainable and eco-friendly alternative [8,9]. Green synthesized nanoparticles often exhibit good biocompatibility and high stability, do not require various biological and chemical stabilizers, and require minimal post-processing steps [7,10]. Also, it is undeniable that some conventional methods of nanoparticle synthesis can harm the environment [6]. On the other hand, physical synthesis of nanoparticles sometimes has fewer risks than chemical methods; still, the complexity of the tools and the high cost of this method will limit the application of synthesized nanoparticles [11].

Selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) have gained significant interest in recent years due to their unique properties and potential applications in biomedicine and other fields [12,13]. Selenium is an essential element for various enzymes and proteins, including selenoproteins, which play a crucial role in DNA production and protection against cellular damage and infection [14]. However, some selenium supplements, especially mineral forms, can be toxic at high doses [15]. SeNPs have been shown to be less toxic and exhibit improved biological activities compared to their bulk counterparts [16,17]. They possess significant anticancer and antioxidant properties, making them promising candidates for various biomedical applications such as anti-inflammatory agents, drug carriers, cancer therapy, diabetes treatment, and immune stimulators [18,19,20,21]. The biological synthesis of SeNPs offers several advantages over conventional methods. Biologically synthesized nanoparticles are typically less toxic, more stable, and require fewer purification steps [22]. Also, the ecologically sustainable method of producing nanoparticles offers the chance to use them safely in different sectors [23,24].

Biological SeNPs have been produced using a variety of techniques and are derived from a variety of biological sources, such as plant extract, bacteria, fungi, etc. [25,26,27,28]. The novelty of this research lies in our exploration of the potential of the Limosilactobacillus fermentum strain ATCC 14931 for the green synthesis of SeNPs. While various biological sources have been employed for SeNP synthesis, Limosilactobacillus fermentum offers distinct advantages. Furthermore, limited research has explored the ability of cell-free culture (CFC) from Limosilactobacillus fermentum for SeNP synthesis. We explore the influence of various factors, such as pH, temperature, and sodium selenite concentration, on the production and properties of the synthesized nanoparticles. We chose Limosilactobacillus fermentum due to its Generally Recognized As Safe status, implying its safety for large-scale production processes. Additionally, L. fermentum was chosen due to its well-documented reducing power, a key factor for SeNP biosynthesis [20]. Uniformity in size and shape is crucial for consistent nanoparticle properties and functionalities [29]; therefore, the production of uniform NPs is a primary focus of this research. To assess the role of reducing power in the NP synthesis process, we further evaluated the pre- and post-synthesis reducing power of the resulting CFC. This evaluation employed the DPPH assay to determine if the reducing potential of the CFC had been diminished during the NP synthesis process.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Chemical compounds used in the synthesis of NPs

SeNPs were synthesized using sodium selenite pentahydrate (Na2SeO3·5H2O) obtained from Merck, Germany. MRS broth medium (Q-LAB, Germany) was used for bacterial cultivation.

2.2 Bacterial strain and growth conditions

The Limosilactobacillus fermentum strain ATCC 14931 was obtained from the Iranian biological resource center. The bacteria were grown in an MRS broth medium at 37°C under aerobic conditions for 24 h.

2.3 Preparation of CFC

Preparation of CFC began by thawing a frozen aliquot of the bacterial stock culture, which had been previously stored at −80°C. This thawing process should be rapid (around 30–37°C using a water bath) to minimize the risk of damaging the frozen bacterial cells; 25 μL of thawed bacterial cells were then aseptically inoculated into 10 mL of autoclaved MRS broth medium. Aseptic techniques are crucial at all steps of CFC preparation and synthesis to prevent contamination with unwanted microorganisms. The flask containing pre-culture was incubated at 37°C, which is the optimal growth temperature for L. fermentum. Constant shaking at 180 rpm ensures proper aeration and the homogeneous distribution of nutrients and bacterial cells throughout the culture medium. The pre-culture was incubated for 16 h. This incubation period allows the bacteria to adapt from their frozen state, revive, and begin multiplying. After the pre-culture incubation, 10 mL of the pre-culture was aseptically transferred into a larger flask containing 100 mL of fresh, autoclaved MRS broth medium. The main culture was then incubated under similar conditions as the pre-culture (37°C, 180 rpm shaking) for an extended period of 24 h. This extended incubation allows for exponential growth of the bacterial population, maximizing the production of metabolites and enzymes. Aerobic conditions were maintained throughout the incubation using flasks with breathable caps. Following incubation, the bacterial culture was centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 20 min using a refrigerated centrifuge. Using a refrigerated centrifuge helps maintain low temperatures during centrifugation. The resulting supernatant, referred to as the CFC, was carefully collected under sterile conditions. The sterile collection of the CFC ensures minimal contamination that could interfere with the nanoparticle biosynthesis process.

2.4 Biosynthesis of SeNPs

After preparing CFC, the pH was adjusted to the desired values (pH at values of 5.4, 7.4, and 9.4), and the final concentration of sodium selenite salt in the synthesis solution was also adjusted (0.375, 0.75, 1.5, and 3 mM). All were done under sterile conditions. After adding the salt, the synthesis solution was immediately placed at the desired temperatures (37°C, 25°C, and 4°C) and incubated for 3 days under the conditions. MRS broth was used as a control. After completing the synthesis reaction, samples were centrifuged at 9,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C using a centrifuge. Separated SeNPs were washed in distilled water to eliminate the unreacted salts and other components. Throughout this study, the selected SeNPs were synthesized several times. Then, the SeNPs were resuspended in deionized water and kept at 4°C. If it was needed, SeNPs dried in an oven at 37°C, and their powder was stored.

2.5 Ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) spectroscopy

The UV–visible spectrum of NPs was investigated using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer Inc., USA) operated at a resolution of 1 nm.

2.6 DLS and zeta potential

The Zetasizer Zeta–DLS instrument (Malvern, UK) was used to assess the samples’ size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential at 25°C.

2.7 FESEM-EDX analysis

Images of SeNPs were acquired using an FE-SEM microscope (Sigma VP, ZEISS Germany). A smear of samples on glass was used, and the material was gold-coated. Also, energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis was used to establish the presence of elemental selenium. At a magnification of 10 kV, images were captured.

2.8 Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

SeNPs were added to KBr pellets for this analysis, and the results were analyzed using a Nicolet IR100 FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). Against a potassium bromide background, 400–4,000 cm−1 wave numbers were used to get the FTIR spectra. The acquired peaks were represented as wave number (cm−1) on the Y-axis and transmittance percentage on the X-axis.

2.9 X-ray diffraction (XRD)

Using a Panalytical X-Pert Pro XRD with Cu Ka 1.5406 Å radiation, the XRD patterns of sodium selenite and the selected SeNP sample were obtained. The measurement was recorded over 10–70 (2ϴ).

2.10 MTT assay

The cytotoxicity activity of SeNP was determined by MTT assay using the protocol performed by Riss et al. [30] with some modifications. MCF-7 cell lines were purchased from the Pasteur Institute of Iran. The cell lines were raised in 10% fetal bovine serum (DMEM). The cultured cells were incubated in a biological incubator at 5% CO2 at 37°C. After that, 1 × 104 cells were planted in each well in a 96-well cell culture dish and incubated for 48 h. Then, MCF-7 cells were treated with different concentrations (200, 100, 50, 25, and 12.5 μg·mL−1) of biosynthesized SeNPs. Also, cells were treated with a solution of the same concentration of sodium selenite. Five wells without treatment were considered as the negative control (without treatment). Then, the treated cells and the control sample were incubated for another 24 h under the previously mentioned conditions. The entire experimental process was carried out in an aseptic environment. The MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) test was then performed to assess the vitality of the cells. Using a spectrophotometer, the cell viability was measured at 570 nm. Each experiment was carried out in triplicate. The cell viability percentage (%) was computed using this formula:

where “A” is the optical density in 570 nm.

2.11 DPPH assay

In this study, the radical scavenging activity of CFC was assessed both before and after the synthesis of SeNPs using DPPH (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydroxyl). The CFC before and after the synthesis of NPs was studied. In order to investigate the effect of a longer synthesis process on the final reducing power of the CFC, the synthesis of NPs proceeded for 3 and 5 days. Also, to demonstrate how the MRS culture medium’s reducing power changes as bacterial growth proceeds, the MRS medium was examined. To perform the assay, 100 μL of 0.2 mM DPPH and 100 μL of each sample were mixed in a well of a 96-well microplate, and the microplates were placed in darkness at 25°C for 30 min; 100 μL DPPH solution and 100 μL ethanol 50% were used as controls, and the blank was 100 μL of sample and 100 μL ethanol 96%. With the use of a microplate reader, the absorbance was determined at 517 nm. The following formula is used to calculate the percentage of radical scavenging activity:

where A control is equal to the absorbance of the control sample, A sample is the absorbance of each of the investigated samples, and A blank is the absorbance of samples without DPPH. All absorbances were investigated at 517 nm. The test was done in triplicate.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Biosynthesis of SeNPs

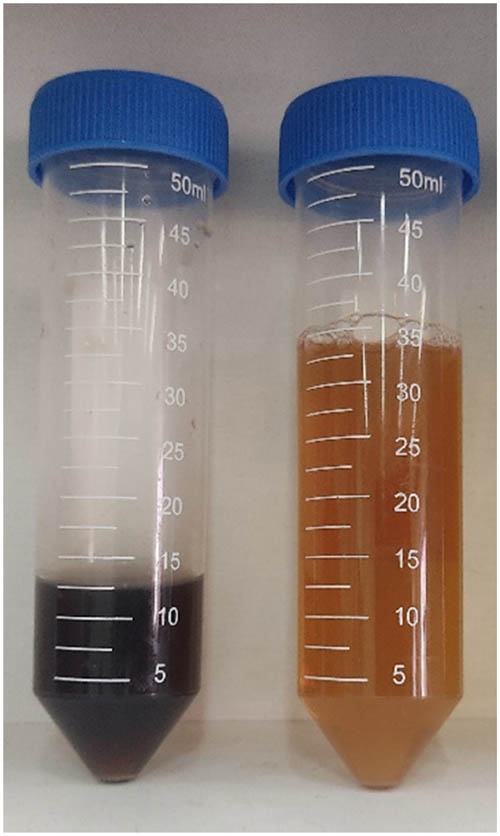

The initial step in the shaping of nanoparticles is visual coloration [31,32]. The formation of SeNPs can be detected by a change of color in the synthesis colloid (Figure 1) and confirmed by additional tests [33]. Previous studies have reported that during the synthesis of SeNPs in an aqueous environment, the color of the synthesis solution changes to red and then to dark red [34], and this is an indication of the reduction of ionic Se to elemental Se and probably the formation of SeNPs. As can be seen in Figure 1, since the MRS and therefore CFC have a darkish red color, it is not easy to detect the color change of the MRS-containing NPs. Therefore, we verified the color change in the NP synthesis solution by observing it after the separation of the MRS using a centrifuge. To validate the formation of SeNPs, we further investigate the samples with FESEM, XRD, FTIR, etc.

CFC (left) and Isolated SeNPs (right).

3.2 Selection of advantageous condition

We conducted the synthesis process at different temperature levels (37℃, 25℃, and 4℃), pH levels (5.4, 7.4, and 9.4), and sodium selenite concentrations (0.375, 0.75, 1.5, and 3 mM) to find conditions that are necessary to achieve nanoparticles with desirable physicochemical properties. Out of the 36 tested conditions, we only detected a color change in 12 of them. In the rest of the cases, no considerable color change was seen. Additional experiments were needed to confirm the synthesis of nanoparticles in those 12 samples since a change in the color of the synthetic solution is a required but insufficient criterion to validate the synthesis of nanoparticles. However, we handled these 12 samples, as nanoparticles so that we could narrow down the sample pool in order to discover the optimal condition. It should also be noted that the synthesis of SeNPs in all experiments occurred only in CFC, and color change in the synthesized solution never occurred in the control (MRS + sodium selenite). This can indicate that the synthesis of SeNPs requires the presence of compounds that exist due to the growth of bacteria in the MRS medium. The different synthesis conditions of these 12 samples are presented in Table 1. Due to the lack of considerable color change in other conditions, they were not mentioned.

Synthesis of SeNPs in different conditions (other results not mentioned due to the lack of SeNPs prod)

| Temp (°C) | pH | The concentration of sodium selenite (mM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | 7.4 | 0.75 |

| 2 | 25 | 7.4 | 1.5 |

| 3 | 25 | 7.4 | 3 |

| 4 | 25 | 9.4 | 1.5 |

| 5 | 37 | 7.4 | 0.375 |

| 6 | 37 | 7.4 | 0.75 |

| 7 | 37 | 7.4 | 1.5 |

| 8 | 37 | 7.4 | 3 |

| 9 | 37 | 9.4 | 0.375 |

| 10 | 37 | 9.4 | 0.75 |

| 11 | 37 | 9.4 | 1.5 |

| 12 | 37 | 9.4 | 3 |

An analysis of the combined data from Table 1 suggests that the temperature of 37°C yielded a significantly higher concentration of SeNPs compared to other temperatures tested. For instance, little to no SeNP formation was observed at 4°C, while 25°C resulted in an unfavorable synthesis rate. In terms of pH, most of the neutral and some of the alkaline conditions (pH 7.4 and 9.4) facilitated the formation of SeNPs. Acidic synthesis conditions were unable to do so. The concentration of sodium selenite ions exerted a significant influence. While SeNP synthesis was observed across various sodium selenite (Se⁴⁺) concentrations, our data suggest a critical dependence on Se⁴⁺ availability for optimal nanoparticle characteristics. Both excessive and insufficient Se⁴⁺ concentrations deviated from the desired outcome. High Se⁴⁺ levels resulted in the formation of larger nanoparticles, potentially due to uncontrolled particle aggregation. Conversely, limited Se⁴⁺ availability hindered proper nanoparticle formation, leading to either a complete absence of SeNPs or the production of inadequately sized or shaped nanoparticles. It is necessary to mention the crucial role of reaction time. Shorter than 3-day durations could lead to fewer and smaller SeNPs, whereas extended reaction times could lead to a significant increase in particle size and dispersity [35].

Long-term stability is a crucial factor for SeNP applications. In the next step, we selected the most stable SeNP. To achieve this, colloidal samples that underwent sedimentation or color change within 3 months after the synthesis were discarded due to potential changes in their properties. Sedimentation suggests a loss of stability and aggregation, which can alter the size, surface properties, and ultimately, the functionality of the SeNPs. Color change can be another indicator of morphological or structural transformations within the nanoparticles, potentially affecting their long-term performance [36].

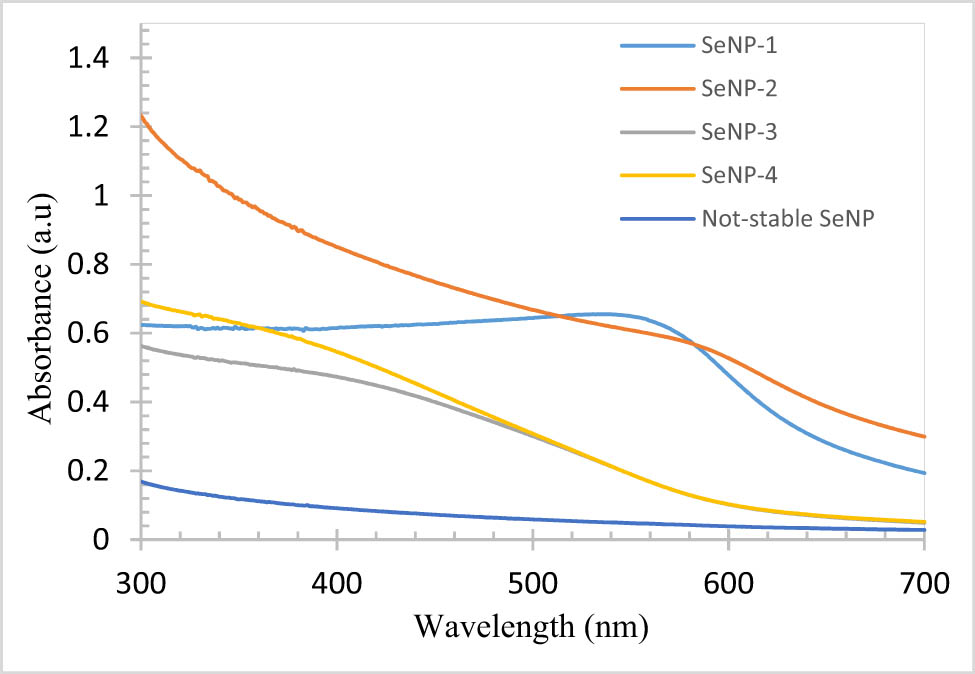

We also consider that SeNPs with relatively sharp absorption peaks might be advantageous (Figure 2). This is because a strong and sharp absorption peak can indicate the creation of nanoparticles with uniform shape and size (low PDI) and low dispersion. Four of the 12 samples met the criteria we considered. The name and synthesis conditions of these nanoparticles are mentioned in Table 2.

Absorption spectrum of selected NPs (an example of Not-stable SeNPs after the change of color to black is also shown).

The synthesis conditions of the four selected samples

| Temp (°C) | pH | The concentration of selenite (mM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SeNP-1 | 37 | 7.4 | 0.75 |

| SeNP-2 | 37 | 7.4 | 1.5 |

| SeNP-3 | 37 | 9.4 | 0.75 |

| SeNP-4 | 37 | 9.4 | 1.5 |

These four samples were stable for more than 3 months and were more stable than other nanoparticles produced. Within 3 months of their production, the stability of these nanoparticles was evaluated based on changes in the colloid’s color and appearance as well as the UV–vis spectrum. Among the four nanoparticles exhibiting 3-month stability, SeNP-1 displayed superior long-term stability, as evidenced by the absence of color change or sedimentation for an extended period. The UV–Vis spectra of these four selected nanoparticles and one example of not-stable SeNPs are shown in Figure 2. SeNP-1 nanoparticles should have a lower PDI and a more uniform distribution of size and shape, according to the result. This can be concluded from the higher and stronger peaks of these nanoparticles compared to other samples.

3.3 Characterization of selected nanoparticles

Various tests were performed to confirm the formation of SeNPs and also identify the properties of four stable nanoparticles to achieve a SeNP with desirable properties (low PDI, high zeta potential, and consequently more stability). These tests include FE-SEM, EDX, and dynamic light scattering–zeta potential (DLS–ZETA).

3.3.1 FE-SEM imaging and EDX elemental analysis

The four chosen nanoparticles were individually observed using FE-SEM microscopy. We can validate the creation of nanoparticles and see their geometric shape using the pictures captured by this microscope. The images of these nanoparticles are shown in Figure 3.

Biosynthetic SeNPs; Image of (a) SeNP-1, (b) SeNP-2, (c) SeNP-3, (d) SeNP-4, and (e) control sample (sodium selenite + MRS medium).

As shown in Figure 3, SeNP-1 is mostly spherical. SeNP-2 is mostly cubic or spherical. SeNP-3 seems to have irregular and spherical shapes, and SeNP-4 is irregular and different in shape. Thus, SeNP-1, among these four samples, has the most uniform shape and is generally spherical. Additionally, to confirm the presence of selenium in the image taken by FESEM and to ensure that observed nanoparticles are selenium we used EDX, in which the presence of selenium was confirmed by the existence of a peak at 1.347 keV (data not shown).

3.3.2 DLS–ZETA test

DLS is a typical method for determining a particle’s hydrodynamic size. The frequency of light scattered by colloidal particles is inversely related to the particle diameter per unit of time. The scattered light frequency by SeNP-1 nanoparticles shows that their particle size is in the nanometer range (Figure 4(a)).

Result of DLS-ZETA analyses: (a) the size distribution graph for SeNP-1, (b) the zeta potential distribution of SeNP-1.

The result shows that SeNP-1 nanoparticles have an average hydrodynamic radius below 100 nm (92.52 nm). Additionally, the PDI index has the lowest value (0.134) compared to other samples, indicating the monodispersity of these nanoparticles. SeNP-2 and 3 had particle radii of 122.9 and 126.2 nm, respectively, and greater hydrodynamic sizes. Additionally, both samples have much higher PDI values (0.350 and 0.372, respectively). SeNP-4 has a smaller hydrodynamic size than other samples. The PDI index in this sample was equal to 0.201. Therefore, SeNP-1 can be considered to have an advantageous PDI and size among SeNPs.

The high zeta potential of particles in colloids avoids aggregation and agglomeration. In general, nanoparticles with a zeta potential above +30 mV or less than −30 mV are regarded as stable colloidal systems [37]. Among the synthesized nanoparticles, SeNP-1 has a zeta potential equal to −32.2 mV (Figure 4(b) and Table 3). As can be seen in Table 3, SeNPs-2, 3, and 4 have a less than 30 mV zeta potential value (−11.5, −14.5, and −14.4 mV, respectively). It is expected that SeNP-1 colloids have more stability compared to other synthesized NPs. As mentioned before, to confirm the stability of the synthesized NPs, we kept them for a long time (3 months or more) under ambient conditions. SeNP-1 was more stable than the other tested NPs, and it did not change color or aggregate over time. Therefore, based on the results obtained, SeNP-1 was selected for further characterization steps as having high stability, low polydispersity, and an almost uniform shape. To obtain a sufficient quantity of SeNP-1 for comprehensive characterization and establish the reproducibility of the synthesis process, the procedure was repeated on more than three occasions. The re-synthesized nanoparticles were then evaluated for consistency in shape, size, and UV–vis spectrum. These analyses were done to verify that the physicochemical properties of the NPs remained consistent across different batches. No significant deviations were observed in the repeated syntheses, confirming the reproducibility of the SeNP-1 synthesis method. Our biosynthesized nanoparticles, in contrast to some other research, exhibit a more ideal PDI and greater zeta potential, without any surface modification or extra chemical component addition [38,39,40]. The results of the DLS–ZETA test for the four stable NPs are shown in Table 3.

The results obtained from the DLS–ZETA test of SeNPs-1, 2, 3, and 4

| Hydrodynamic radius (nm) | Zeta potential (mV) | PDI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SeNP-1 | 92.52 | −32.2 | 0.134 |

| SeNP-2 | 122.9 | −11.5 | 0.350 |

| SeNP-3 | 126.2 | −14.5 | 0.372 |

| SeNP-4 | 67.80 | −14.4 | 0.201 |

3.3.3 FTIR test

To confirm the synthesis of SeNP-1 and to identify the functional groups present on the NP’s surface, an FTIR test was carried out, and the result is shown in Figure 5(a).

(a) FTIR spectrum of SeNP-1 and Na2SeO3·5H2O salt, (b) and (c) XRD spectrum of SeNP-1(b) and Na2SeO3·5H2O salt (c), (d) the percentage of viability of MCF-7 cells with different concentrations of SeNP-1 and sodium selenite salt treatment, and (e) radical scavenging activity of MRS and CFC (before and after NP synthesis).

Identification of functional groups on the surface of NPs is made possible by FTIR [41]. FTIR analysis of the SeNP-1 sample exhibits a significant peak at 3,450 cm−1. This peak is connected to the stretching bonds of O–H, potentially arising from hydroxyl groups in alcohols, phenols, or carboxylic acids [42]. The peak at 1,633 cm⁻¹ could be attributed to either C═C stretching in unsaturated carboxylic acids or C═O stretching in amides. Additionally, the 1,392 cm⁻¹ band might be indicative of C–N stretching vibrations in amines or nitro compounds [43]. While the FTIR analysis provided valuable insights into the presence of functional groups on the SeNPs, the definitive assignment of these groups requires further investigation. Even with our current understanding, the identified functional groups likely play a significant role in the biomedical applications of these SeNPs. For instance, the presence of hydroxyl groups could contribute to improved water dispersibility, facilitating their delivery within physiological environments. Additionally, these functional groups could serve as anchoring sites for biomolecules like drugs or targeting ligands, enhancing their potential for targeted drug delivery or specific cellular interactions. The possibility of protein adsorption onto the nanoparticle surfaces can further influence their stability in biological fluids and impact their interaction with eukaryotic cells. Depending on the adsorbed protein corona, the SeNPs could exhibit enhanced biocompatibility or altered targeting specificities.

Furthermore, the FTIR spectrum of sodium selenite, employed as a reference material, exhibits distinct and intense bands at 735 and 786 cm⁻¹, corresponding to symmetric and asymmetric Se–O stretching vibrations, respectively [44]. Conversely, the SeNP-1 spectrum lacks these two distinct peaks. Instead, a broad and significantly weaker band was observed at 614 cm⁻¹ (400–875 cm⁻¹ region). This stark difference suggests a substantially lower abundance of Se–O bonds in SeNP-1 compared to pure sodium selenite [15,45,46]. The FTIR analysis provides evidence supporting a reduction in Se–O bonds during the transformation of precursor materials to elemental SeNPs (Se0) within the SeNP-1 sample.

3.3.4 XRD

The XRD analysis was employed to identify the kind and type of crystallinity of nanoparticles. In amorphous materials, the lattice planes are small but many. The amorphous nature of the nanoparticles is demonstrated by the continuous, wide, and jagged peaks. There is no discernible pattern in the XRD spectra of SeNP-1. The outcome of the XRD analysis of sodium selenite and SeNP-1 was in agreement with results from some other studies in which sodium selenite crystals were transformed into polymorph nanoparticles in the process of biosynthesis [15,36,39,47,48]. According to the result, the sodium selenite salt’s crystalline form was converted into amorphous SeNPs during the biosynthesis process (Figure 5(b and c)).

3.3.5 MTT assay

The MTT assay was conducted to investigate the toxicity of SeNPs compared to sodium selenite salt. As shown in Figure 5(d), cell viability increased as salt, and SeNP-1 concentrations were lowered. Cell viability was significantly higher following exposure to SeNP-1 compared to the salt at equivalent concentrations. The calculated IC50 values corroborated this observation, with sodium selenite salt exhibiting a lower IC50 (16 μg·mL−1) compared to SeNP-1 (67 μg·mL−1). This means the IC50 of SeNP-1 is equal to the IC50 of selenium salt at greater concentrations of NPs. Potential mechanisms for toxicity of SeNPs could be due to their interaction with MCF-7 apoptotic proteins (Bcl-2, Bax, and caspase-3) leading to programmed cell death, disruption in mitochondria, and inducing the release of cytochrome c (apoptosis initiator), increase reactive oxygen species production and ultimately causing oxidative stress and cell death [49,50]. The SeNP-1 has much lower toxicity for eukaryotic cells compared to sodium selenite [51]. The underlying mechanism for this decreased toxicity in SeNP-1 remains to be elucidated. However, it is hypothesized that the presence of biomolecules such as proteins or polysaccharides on the nanoparticle surface may play a role in mitigating their cytotoxic effects [52]. The reduction in nanoparticle toxicity makes them more acceptable for use in various applications, such as animal and poultry food supplements, intracellular drug delivery systems, and other scenarios where interaction with eukaryotic cell surfaces is necessary. It is logically justified that the use of nanoparticles with high cytotoxicity is impractical and limits their use.

As shown in Table 4, the cytotoxic activity of biosynthesized SeNPs against the MCF-7 cell line and SeNPs with different sources were compared. SeNP-1 exhibits a lower IC50 (67 µg·mL−1) compared to various other biologically synthesized SeNPs. The IC50 values for pomegranate peel extract SeNPs (69.8 µg·mL−1), SeNPs fabricated by endophytic fungal strain Penicillium verhagenii (283.8 µg·mL−1), and biosynthesized SeNPs Utilizing Lactobacillus casei (>100 µg·mL−1) were all higher. This suggests a potentially greater anticancer efficacy of SeNP-1. However, a chemically synthesized starch-stabilized SeNP displayed a significantly lower IC50 of 11.3 µg·mL−1. This value might be attributed to the inherent cytotoxicity associated with chemically synthesized nanoparticles, warranting further investigation to distinguish between true anticancer properties and general cytotoxicity.

Synthesized SeNPs from different source and their cytotoxicity against cancer cell line MCF-7

| Nanoparticle type | IC50 (µg·mL−1) against MCF-7 | Synthesis method | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pomegranate peel extract SeNPs | 69.8 | green synthesis | [53] |

| SeNPs fabricated by endophytic fungal strain Penicillium verhagenii | 283.8 | green synthesis | [54] |

| Starch-Stabilized SeNPs | 11.3 | chemically synthesis | [55] |

| Biosynthesized SeNPs utilizing Lactobacillus casei | higher than 100 (20% inhibition by 100 μg·mL−1 SeNPs) | green synthesis | [56] |

| Biosynthesized SeNPs by Limosilactobacillus fermentum | 67 | Green synthesis | This study |

Based on these results, the synthesized nanoparticles hold promise as candidates for both cancer treatment and drug delivery applications. Furthermore, their reduced toxicity compared to sodium selenite salt suggests their potential use as a selenium supplement in livestock and poultry feed.

3.3.6 DPPH assay

Similar to other studies, the precise mechanism by which bacterial extracellular extract mediates the biosynthesis of SeNPs remains elusive. While various hypotheses have been proposed, including the involvement of specific enzymes, regenerative compounds, or cellular processes, the exact role of these factors is unclear [57]. In this work, we hypothesize that the primary driver of SeNP biosynthesis is the presence of reducing compounds released by the bacteria during growth in the culture medium. We propose that these reducing compounds within the CFC contribute to the formation of nanoparticles, and other protein components secreted into the culture medium may contribute to the stability of the synthesized nanoparticles. To investigate this hypothesis that the presence of reducing compounds in the synthesis solution has the main role in the biogenic production of NPs, the DPPH assay was performed [58]. As shown in Figure 5(e), the radical scavenging activity percentage of MRS and CFC was significantly higher than that of samples after synthesis. It is also evident that with increasing synthesis time, the radical scavenging activity of CFC decreases, indicating higher consumption of reducing compounds during the longer biogenic synthesis process. The results showed that the antioxidant ability and reducing power of the MRS culture medium before the growth of bacteria are outstanding. However, NP does not synthesize in a culture medium. Therefore, it is likely that the substances in CFC that originate from the bacterium Limosilactobacillus fermentum and contribute to SeNP production are more than just reducing substances. As shown in Figure 5(e), with the start and completion of the synthesis, the antioxidant activity of the CFC decreases significantly. Based on this information, it can be claimed that the presence of reducing compounds in MRS is necessary for nanoparticle synthesis but not sufficient. Also, a significant amount of reducing compounds is consumed during the synthesis process. Therefore, it can be justified that the synthesis process can depend on a specific type of reducing compound produced by bacteria during their growth process, or more likely on proteins and enzymes released by bacteria into CFC that can consume reducing compounds and facilitate electron transfer between reducing compounds and selenium ions. It is also important to note that all of the samples were analyzed both on the day they were prepared and on the last day of analyses (5 days after the beginning of NP synthesis), and there was no discernible change in the outcomes throughout this time. Further research is needed to confirm the exact mechanism, protein, and reducing compound that plays a role in the biosynthesis process.

4 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study successfully demonstrated a safe and environmentally friendly method for producing stable, low-toxicity SeNPs using the CFC of Limosilactobacillus fermentum bacteria. This method offers a promising alternative to traditional nanoparticle synthesis techniques that can be hazardous or generate toxic byproducts. The optimal conditions for SeNP synthesis were identified as 37°C, pH 7.4, and a sodium selenite concentration of 0.75 mM. Furthermore, the nanoparticles exhibited desirable physical–chemical properties, including uniform size and shape, high stability at neutral pH, and lower cellular toxicity compared to sodium selenite salt. Additionally, the study suggests a correlation between reaction temperature and nanoparticle formation rate. Notably, we achieved the desired size distribution and shape without the use of external size-limiting agents or complex protocols. A precise examination of various synthesis parameters and their precise control during nanoparticle fabrication resulted in the selection of a uniform size, shape, and stability of SeNP.

Our investigation further suggests the utilization of reducing agents present in the CFC during the synthesis process, potentially indicating an enzymatic mechanism. However, a comprehensive understanding of this biogenic synthesis necessitates the identification of specific reducing agents, proteins, enzymes, and other bacterial secretions present in the CFC. The promising properties of SeNPs, particularly their reduced cytotoxicity relative to sodium selenite salt, make them promising candidates for additional biomedical research and investigation, with potential for a range of biomedical uses. In general, SeNPs have shown potential in several diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, asthma, liver diseases, and various autoimmune disorders like psoriasis, cancer, and diabetes. They can also act as drug carriers and supplements in animal and poultry feed. Understanding the exact mechanism of synthesis will enable us to optimize the production process and tailor SeNP properties for specific biomedical applications. Therefore, due to the promising characteristics of our biogenic nanoparticles, further research is warranted to explore the exact mechanism and compounds that play a role in synthesizing SeNPs and their potential in various medical fields.

Acknowledgments

This work is based upon research funded by Iran National Science Foundation (INSF) under project No. 4020437. The author sincerely appreciates the training and advice of Mrs. Haji Ali during the project.

-

Funding information: The research was funded by the Iran National Science Foundation (INSF) under project No. 4020437.

-

Author contributions: S.A.A: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualization, and writing – original draft. S.D: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, visualization, funding acquisition, and writing – review & editing. K.K: visualization, investigation, software, methodology, and writing – review & editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Salem SS, Badawy M, Al-Askar AA, Arishi AA, Elkady FM, Hashem AH. Green biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles using orange peel waste: Characterization, antibacterial and antibiofilm activities against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Life. 2022;12(6):893.10.3390/life12060893Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Hashem AH, Khalil AMA, Reyad AM, Salem SS. Biomedical applications of mycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Penicillium expansum ATTC 36200. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2021;199:1–11.10.1007/s12011-020-02506-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Singh P, Kim YJ, Zhang D, Yang DC. Biological synthesis of nanoparticles from plants and microorganisms. Trends Biotechnol. 2016;34(7):588–99.10.1016/j.tibtech.2016.02.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Rajeshkumar S, Veena P, Santhiyaa R. Synthesis and characterization of selenium nanoparticles using natural resources and its applications. In: Exploring the realms of nature for nanosynthesis. China: Springer; 2018. p. 63–79.10.1007/978-3-319-99570-0_4Search in Google Scholar

[5] Mourdikoudis S, Pallares RM, Thanh NT. Characterization techniques for nanoparticles: comparison and complementarity upon studying nanoparticle properties. Nanoscale. 2018;10(27):12871–934.10.1039/C8NR02278JSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Singh J, Dutta T, Kim KH, Rawat M, Samddar P, Kumar P. ‘Green’synthesis of metals and their oxide nanoparticles: applications for environmental remediation. J Nanobiotechnol. 2018;16(1):1–24.10.1186/s12951-018-0408-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Ajitha B, Reddy YAK, Reddy PS. Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Lantana camara leaf extract. Mater Sci Eng: C. 2015;49:373–81.10.1016/j.msec.2015.01.035Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Shahzamani K, Lashgarian HE, Karkhane M, Ghaffarizadeh A, Ghotekar S, Marzban A. Bioactivity assessments of phyco-assisted synthesized selenium nanoparticles by aqueous extract of green seaweed, Ulva fasciata. Emergent Mater. 2022;5(6):1689–98.10.1007/s42247-022-00415-6Search in Google Scholar

[9] Korde P, Ghotekar S, Pagar T, Pansambal S, Oza R, Mane D. Plant extract assisted eco-benevolent synthesis of selenium nanoparticles-a review on plant parts involved, characterization and their recent applications. J Chem Rev. 2020;2(3):157–68.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Mehrafza M, Daneshjou S, Khajeh K, Sepahi AA. Green fabrication of cobalt oxide nanoparticles by Bacillus megaterium and their antibacterial activities. BioNanoScience. 2024. 10.1007/s12668-024-01446-5 Search in Google Scholar

[11] Pérez-Hernández H, Pérez-Moreno A, Sarabia-Castillo CR, García-Mayagoitia S, Medina-Pérez G, López-Valdez F, et al. Ecological drawbacks of nanomaterials produced on an industrial scale: collateral effect on human and environmental health. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2021;232(10):1–33.10.1007/s11270-021-05370-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Elbahnasawy MA, Shehabeldine AM, Khattab AM, Amin BH, Hashem AH. Green biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using novel endophytic Rothia endophytica: Characterization and anticandidal activity. J Drug Delivery Sci Technol. 2021;62:102401.10.1016/j.jddst.2021.102401Search in Google Scholar

[13] Lashin I, Hasanin M, Hassan SAM, Hashem AH. Green biosynthesis of zinc and selenium oxide nanoparticles using callus extract of Ziziphus spina-christi: Characterization, antimicrobial, and antioxidant activity. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2023;13(11):10133–46.10.1007/s13399-021-01873-4Search in Google Scholar

[14] Combs Jr G, Combs SB. The role of selenium in nutrition. New York: Academic Press, Inc; 1986.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Alipour S, Kalari S, Morowvat MH, Sabahi Z, Dehshahri A. Green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles by cyanobacterium Spirulina platensis (abdf2224): Cultivation condition quality controls. BioMed Res Int. 2021;2021:6635297.10.1155/2021/6635297Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Chaudhary S, Umar A, Mehta S. Surface functionalized selenium nanoparticles for biomedical applications. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2014;10(10):3004–42.10.1166/jbn.2014.1985Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Khorrami S, Zarrabi A, Khaleghi M, Danaei M, Mozafari MR. Selective cytotoxicity of green synthesized silver nanoparticles against the MCF-7 tumor cell line and their enhanced antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. Int J Nanomed. 2018;13:8013–24.10.2147/IJN.S189295Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Huang Y, He L, Liu W, Fan C, Zheng W, Wong YS, et al. Selective cellular uptake and induction of apoptosis of cancer-targeted selenium nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2013;34(29):7106–16.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.04.067Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Hosnedlova B, Kepinska M, Skalickova S, Fernandez C, Ruttkay-Nedecky B, Peng Q, et al. Nano-selenium and its nanomedicine applications: a critical review. Int J Nanomed. 2018;13:2107–28.10.2147/IJN.S157541Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Bisht N, Phalswal P, Khanna PK. Selenium nanoparticles: A review on synthesis and biomedical applications. Mater Adv. 2022;3(3):1415–31.10.1039/D1MA00639HSearch in Google Scholar

[21] Satarzadeh N, Sadeghi Dousari A, Amirheidari B, Shakibaie M, Ramezani Sarbandi A, Forootanfar H. An insight into biofabrication of selenium nanostructures and their biomedical application. 3 Biotech. 2023;13(3):79.10.1007/s13205-023-03476-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Parveen K, Banse V, Ledwani L. Green synthesis of nanoparticles: their advantages and disadvantages. In AIP conference proceedings. Rajasthan, India: AIP Publishing LLC; 2016.10.1063/1.4945168Search in Google Scholar

[23] Al-Rajhi AMH, Salem SS, Alharbi AA, Abdelghany TM. Ecofriendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Kei-apple (Dovyalis caffra) fruit and their efficacy against cancer cells and clinical pathogenic microorganisms. Arab J Chem. 2022;15(7):103927.10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.103927Search in Google Scholar

[24] Salem SS, Hammad EN, Mohamed AA, El-Dougdoug W. A comprehensive review of nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, characterization, and applications. Biointerface Res Appl Chem. 2022;13(1):41.10.33263/BRIAC131.041Search in Google Scholar

[25] Hashem AH, Salem SS. Green and ecofriendly biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles using Urtica dioica (stinging nettle) leaf extract: Antimicrobial and anticancer activity. Biotechnol J. 2022;17(2):2100432.10.1002/biot.202100432Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Hussein HG, El-Sayed ER, Younis NA, Hamdy A, Easa SM. Harnessing endophytic fungi for biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles and exploring their bioactivities. AMB Express. 2022;12(1):68.10.1186/s13568-022-01408-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Zhang H, Zhou H, Bai J, Li Y, Yang J, Ma Q, et al. Biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles mediated by fungus Mariannaea sp. HJ and their characterization. Colloids Surf A: Physicochem Eng Asp. 2019;571:9–16.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2019.02.070Search in Google Scholar

[28] Borah SN, Goswami L, Sen S, Sachan D, Sarma H, Montes M, et al. Selenite bioreduction and biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles by Bacillus paramycoides SP3 isolated from coal mine overburden leachate. Environ Pollut. 2021;285:117519.10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117519Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Clayton KN, Salameh JW, Wereley ST, Kinzer-Ursem TL. Physical characterization of nanoparticle size and surface modification using particle scattering diffusometry. Biomicrofluidics. 2016;10(5):054107.10.1063/1.4962992Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Riss TL, Moravec RA, Niles AL, Duellman S, Benink HA, Worzella TJ, et al. Cell viability assays. Assay guidance manual [Internet]; United States: National center for Biotechnology information; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Dhanraj G, Rajeshkumar S. Anticariogenic effect of selenium nanoparticles synthesized using brassica oleracea. J Nanomaterials. 2021;2021:1–9.10.1155/2021/8115585Search in Google Scholar

[32] Alvi GB, Iqbal MS, Ghaith M, Haseeb A, Ahmed B, Qadir MI. Biogenic selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) from citrus fruit have anti-bacterial activities. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):4811.10.1038/s41598-021-84099-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Cittrarasu V, Kaliannan D, Dharman K, Maluventhen V, Easwaran M, Liu WC, et al. Green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles mediated from Ceropegia bulbosa Roxb extract and its cytotoxicity, antimicrobial, mosquitocidal and photocatalytic activities. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1032.10.1038/s41598-020-80327-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Dwivedi C, Shah CP, Singh K, Kumar M, Bajaj PN. An organic acid-induced synthesis and characterization of selenium nanoparticles. J Nanotechnol. 2011;2011:1–6.10.1155/2011/651971Search in Google Scholar

[35] Pyrzynska K, Sentkowska A. Biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles using plant extracts. J Nanostruct Chem. 2022;12:467–80.10.1007/s40097-021-00435-4Search in Google Scholar

[36] Mollania N, Tayebee R, Narenji-Sani F. An environmentally benign method for the biosynthesis of stable selenium nanoparticles. Res Chem Intermed. 2016;42:4253–71.10.1007/s11164-015-2272-2Search in Google Scholar

[37] Raval N, Maheshwari R, Kalyane D, Youngren-Ortiz SR, Chougule MB, Tekade RK. Importance of physicochemical characterization of nanoparticles in pharmaceutical product development. In: Basic fundamentals of drug delivery. United States: Elsevier; 2019. p. 369–400.10.1016/B978-0-12-817909-3.00010-8Search in Google Scholar

[38] Hajiali S, Daneshjou S, Daneshjoo S. Biomimetic synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles from Bacillus megaterium to be used in hyperthermia therapy. AMB Express. 2022;12(1):145.10.1186/s13568-022-01490-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Shakibaie M, Khorramizadeh MR, Faramarzi MA, Sabzevari O, Shahverdi AR. Biosynthesis and recovery of selenium nanoparticles and the effects on matrix metalloproteinase‐2 expression. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2010;56(1):7–15.10.1042/BA20100042Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Bai K, Hong B, He J, Hong Z, Tan R. Preparation and antioxidant properties of selenium nanoparticles-loaded chitosan microspheres. Int J Nanomed. 2017;12:4527–39.10.2147/IJN.S129958Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Gunti L, Dass RS, Kalagatur NK. Phytofabrication of selenium nanoparticles from Emblica officinalis fruit extract and exploring its biopotential applications: antioxidant, antimicrobial, and biocompatibility. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:931.10.3389/fmicb.2019.00931Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Asefian S, Ghavam M. Green and environmentally friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles with antibacterial properties from some medicinal plants. BMC Biotechnol. 2024;24(1):5.10.1186/s12896-023-00828-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Talabani RF, Hamad SM, Barzinjy AA, Demir U. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles and their applications in harvesting sunlight for solar thermal generation. Nanomaterials. 2021;11(9):2421.10.3390/nano11092421Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Kretzschmar J, Jordan N, Brendler E, Tsushima S, Franzen C, Foerstendorf H, et al. Spectroscopic evidence for selenium (IV) dimerization in aqueous solution. Dalton Trans. 2015;44(22):10508–15.10.1039/C5DT00730ESearch in Google Scholar

[45] Chen Y-W, Li L, D'Ulivo A, Belzile N. Extraction and determination of elemental selenium in sediments – A comparative study. Anal Chim Acta. 2006;577(1):126–33.10.1016/j.aca.2006.06.020Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Kazemi M, Akbari A, Sabouri Z, Soleimanpour S, Zarrinfar H, Khatami M, et al. Green synthesis of colloidal selenium nanoparticles in starch solutions and investigation of their photocatalytic, antimicrobial, and cytotoxicity effects. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2021;44:1215–25.10.1007/s00449-021-02515-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Huang B, Zhang J, Hou J, Chen C. Free radical scavenging efficiency of Nano-Se in vitro. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35(7):805–13.10.1016/S0891-5849(03)00428-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Filipović N, Ušjak D, Milenković MT, Zheng K, Liverani L, Boccaccini AR, et al. Comparative study of the antimicrobial activity of selenium nanoparticles with different surface chemistry and structure. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021;8:624621.10.3389/fbioe.2020.624621Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Othman MS, Aboelnaga SM, Habotta OA, Moneim AEA, Hussein MM. The potential therapeutic role of green-synthesized selenium nanoparticles using carvacrol in human breast cancer MCF-7 cells. Appl Sci. 2023;13(12):7039.10.3390/app13127039Search in Google Scholar

[50] Al-Otaibi AM, Al-Gebaly AS, Almeer R, Albasher G, Al-Qahtani WS, Abdel Moneim AE. Potential of green-synthesized selenium nanoparticles using apigenin in human breast cancer MCF-7 cells. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29(31):47539–48.10.1007/s11356-022-19166-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Hendriks BS. Functional pathway pharmacology: chemical tools, pathway knowledge and mechanistic model-based interpretation of experimental data. Curr OpChem Biol. 2010;14(4):489–97.10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.06.167Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Wilber CG. Toxicology of selenium: a review. Clin Toxicol. 1980;17(2):171–230.10.3109/15563658008985076Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Hashem AH, Saied E, Ali OM, Selim S, Al Jaouni SK, Elkady FM, et al. Pomegranate peel extract stabilized selenium nanoparticles synthesis: promising antimicrobial potential, antioxidant activity, biocompatibility, and hemocompatibility. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2023;195(10):5753–76.10.1007/s12010-023-04326-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[54] Nassar AA, Eid AM, Atta HM, El Naghy WS, Fouda A. Exploring the antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticancer, biocompatibility, and larvicidal activities of selenium nanoparticles fabricated by endophytic fungal strain Penicillium verhagenii. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):9054.10.1038/s41598-023-35360-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[55] Drweesh EA, Elzahany EAM, Awad HM, Abou-El-Sherbini KS. Starch-stabilized selenium nanoparticles: synthesis, purification, characterization, in vitro anticancer and apoptosis inducing evaluation. BioNanoScience. 2024;14:1–16.10.1007/s12668-023-01296-7Search in Google Scholar

[56] Haji Mehdi Nouri Z, Tafvizi F, Amini K, Khandandezfully N, Kheirkhah B. Enhanced induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in MCF-7 breast cancer and HT-29 colon cancer cell lines via low-dose biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Lactobacillus casei. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2024;202(3):1288–304.10.1007/s12011-023-03738-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] Rao V, Poonia A. Microbial biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles using probiotic strain and its characterization. J Food Meas Charact. 2024;18:1–12.10.1007/s11694-024-02581-zSearch in Google Scholar

[58] Kedare SB, Singh R. Genesis and development of DPPH method of antioxidant assay. J Food Sci Technol. 2011;48:412–22.10.1007/s13197-011-0251-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base