Abstract

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a chemical that is widely used in many industrial processes, and, except at certain concentrations, it is toxic in biological systems such as water and air. Among enzymes, catalases are important industrial enzymes because of their role in the conversion of hydrogen peroxide to water and molecular oxygen. Herein, catalase (CAT) from Hydnum repandum was purified 3.02-fold with a yield of 68.10% by three-phase partitioning (TPP) for the first time. The purified catalase was immobilised on glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan (Glu-Cts), and its applicability for the removal of hydrogen peroxide released from industrial processes was investigated. The results of the present study showed that the optimum pH and temperature were found to be 7.0 and 30°C for both free and immobilised catalase (CAT-Glu-Cts). The catalytic efficiency (V max/K m) of the immobilised enzyme increased 8-fold compared to the free enzyme. CAT-Glu-Cts was shown to have better pH, thermal stability, and storage stability than free CAT. In this study, >96% of 6 mM, 15 ve 24 mM H2O2 was removed from artificial wastewater after 2 h using immobilised catalase. We expect that CAT-Glu-Cts, obtained by purifying a plant-derived catalase and immobilising it into an environmentally friendly and biocompatible material, is a promising candidate that can be safely used for H2O2 removal in various branches of industry.

1 Introduction

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), a universal industrial oxidant, is one of the hundred most widely used chemicals in the environmental, pharmaceutical, textile, food, mining and healthcare industries. More than 50% of the H2O2 produced worldwide is consumed in various industrial applications. H2O2 residues in wastewater resulting from these activities are harmful to living systems [1,2,3]. Previous studies have reported that inhalation or ingestion of hydrogen peroxide for any reason can cause cell death [4,5]. In addition, the presence of H2O2 in air and water is very harmful to plants. It has been found that the concentration of H2O2 in surface water determines the state of flora and fauna, as well as air and water quality. Some studies have shown that fish and fish eggs die when exposed to 50 ppm H2O2 for 15 min. In addition, studies have shown that some microorganisms and zooplankton in aquatic ecosystems are negatively affected at a concentration of 3.4 ppb H2O2 [5,6]. It is, therefore, important for all living organisms and the environment that the concentration of H2O2 is within a safe range.

H2O2 removal studies are carried out to eliminate the harmful effects of H2O2 remaining in the environment after industrial applications. In general, inorganic catalysts such as sodium carbonate or iron sulphate (FeSO4) are used along with heat to remove H2O2 from wastewater. However, this process leads to undesirably high salt concentrations [7,8]. Similarly, metal oxides and metal nanoparticles are also used to remove H2O2. Metal oxides and metal nanoparticles can remove H2O2 under neutral and alkaline conditions but produce hydroxyl under acidic conditions. Hydroxyl is an undesirable situation as it disrupts the structure of chemicals in the environment. Although these methods are used for H2O2 removal, they have disadvantages such as pH adjustment of metal oxides and metal nanoparticles, undesirable OH production, and are expensive [9,10]. Therefore, more sustainable and environmentally friendly methods for H2O2 removal are needed.

Catalase is an excellent candidate for the removal of excess H2O2 released from industrial, environmental, biological, and food samples due to its ability to convert hydrogen peroxide to water and molecular oxygen [11,12]. For this reason, catalase needs to be purified from inexpensive sources using suitable methods. Chromatographic methods are generally used to purify catalase, but they are expensive and time-consuming [13,14]. Three-phase partitioning (TPP) is a technique for the extraction, purification, and concentration of proteins using t-butanol and ammonium sulphate. Three distinct phases occur in TPP. The upper phase contains pigments, lipids, and enzyme inhibitors; the intermediate phase contains precipitated proteins; and the subphase phase contains polar components [15]. TPP is preferred because it is a simple, fast, and cheap technique [16]. The TPP method has been little used for the purification of catalase [17]. In H2O2 removal studies, the bovine liver has generally been preferred as a source of catalase [6,11,18,19], and in some studies, microorganism-derived catalase has been preferred [20,21]. To our knowledge, the purification of mushroom catalase has rarely been studied [14,22,23]. As free catalase is water soluble, it cannot be removed when added to the medium in H2O2 removal studies. This creates both new pollution in the environment and limits its use in industrial applications due to its increased cost [24]. One of the best ways to overcome this problem and introduce enzymes into the industry is to immobilise them. Compared to free enzymes, immobilised enzymes are preferred to reduce the cost and increase the usability of enzymes in various industries [25]. Many matrices have been used for enzyme immobilisation, such as various nano-based materials [26], amino-functionalised PMMA-reinforced graphene nanomaterial [27], porous hybrid microparticles of vaterite with mucin [28], chitosan/ZnO and chitosan/ZnO/Fe2O3 nanocomposites [29], and chitosan (CS)–decorated alumina zirconia–titania composites (AZT) activated with glutaraldehyde [30]. Chitosan is known to be an ideal matrix for enzyme immobilisation. Chitosan, obtained by deacetylation of chitin, is the second most abundant biopolymer after cellulose. Chitosan is widely used as an enzyme immobilisation matrix because it is an inert, inexpensive, biocompatible, biodegradable, non-toxic, and hydrophilic support material [31,32]. The aim of this study is to purify catalase from a mushroom (Hydnum repandum) by the TPP method, immobilise it in biocompatible chitosan, perform its characterisation, and investigate its H2O2 removal potential.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) was used as the enzyme source. The mushroom was obtained from a commercially available hidden forest site. Chitosan (C3646, from shrimp shells, ≥75% (deacetylated)), NaOH, HCl, and buffers were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH Steinheim, Germany.

2.2 Characterisation

Surface images of Glu-Cts and CAT-Glu-Cts were determined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (ZEISS, EVO LS10). The bond types of catalase with Glu-Cts before and after immobilisation were determined by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Agilent Cary 630). For free CAT and CAT-Glu-Cts activities, the H2O2 removal study was carried out using a UV/Vis spectrophotometer (Agilent Cary 60).

2.3 Preparation of the crude enzyme extract

Crude enzyme extracts were prepared by modifying the method of Bilgin Sökmen and Ahıskalı [14]. One hundred grams of Hydnum repandum were weighed and freeze-thawed, and the samples were pounded in a mortar. Then, 200 mL of 50 mM pH 7.0 phosphate buffer was added and left for a while. It was filtered through the muslin cloth (folded 4 times) and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm at 4°C for 30 min, and the supernatant was used as the crude enzyme extract.

2.4 Purification of catalase from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) by TPP

TPP was carried out according to the combination of the following reports [16,33,34,35]. Five millilitres of the crude enzyme extract separately (20%, 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, and 80% w/v) were brought to ammonium sulphate saturation, and then 10 mL of t-butanol was added. It was left at 30°C for 1 h at pH 5.0 to allow phase separation. It was then centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 10 min. The upper phase, in which no protein was expected, was carefully pipetted off. The intermediate phase and subphase were carefully separated. The precipitate in the intermediate phase was dissolved in 5 mL of pH 7.0 phosphate buffer and dialysed with pH 7.0 phosphate buffer. Parameters affecting TPP, such as ammonium sulphate concentration (20%, 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, and 80% w/v), t-butanol ratio (crude enzyme extract/t-butanol; 1.0:0.1, 1.0:2.0, 1.0:3.0 and 1.0:4.0), pH (3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 7.0 and 8.0) and temperature (20°C, 30°C, 40°C and 50°C) were investigated separately. By performing activity and protein determinations in these solutions, purification fold and % yields were calculated. The next optimisation process started with the value giving the best result.

2.5 Protein determination

The protein amounts in the enzyme solution obtained by TPP and in the crude extract were determined by the Bradford method [36].

2.6 Determination of catalase activity

Catalase (CAT) activity was spectrophotometrically determined according to the method suggested by Aebi [37]. The decrease in 240 nm absorbance of a mixture of 2 mL of 30 mM H2O2 solution, 0.9 mL of pH 7.0 phosphate buffer, and 0.1 mL of enzyme solution was recorded in a 3 mL quartz cuvette. To determine the activity of the immobilised enzyme, 2 mL of 30 mM H2O2 solution, 0.9 mL of pH 7.0 phosphate buffer, and 20 mg of immobilised enzyme were added to a centrifuge tube, and the absorbance was measured immediately. After waiting for 10 min, the immobilised enzyme was rapidly filtered through filter paper, and the decrease in absorbance at 240 nm was recorded. The blank contained all solutions except the enzyme.

One unit of the enzyme was determined as the amount of the enzyme required for the degradation of 1 µmol H2O2 in 1 mL·min−1. The specific activity was determined as the activity per mg of protein. The activity of free CAT was expressed as U·mg protein−1. CAT-Glu-Cts activities were given as U·mg protein−1 (here, the amount of protein calculated is the amount of protein bound to the matrix used when measuring activity) or µmol H2O2·g CAT-Glu-Cts−1·dk−1 [38].

2.7 Catalase (CAT) (SDS-PAGE)

SDS-PAGE was performed using 5% loading gel and 10% separation gel [39]. The resulting gel was carefully removed and stained using Coomassie Brilliant Blue R250. The protein bands were washed with the dye removal solution until they became visible and were visualised.

2.8 Catalase (CAT) (Native-PAGE)

Native-PAGE for the catalase enzyme was performed using 5% loading gel without SDS and 10% separation gel. It was determined according to the method suggested by Woodbury et al. [40]. The gel obtained after electrophoresis was washed with distilled water and then kept in 0.003% H2O2 for 10 min. Finally, the gel was kept for 10 min with 1% FeCl2 and 1% K3Fe(CN)6 for imaging.

2.9 Preparation of Glu-CTS and enzyme immobilisation

The catalase amount (0.12, 0.24, 0.49, and 0.73 mg·mL−1) to optimise catalase immobilisation parameters, the amount of chitosan (20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 mg), immobilisation time (1, 2, 3, and 4 h), and glutaraldehyde concentration (1%, 2%, 3%, and 4%) were determined (optimisation data not shown here separately). While conducting this study, the factors other than the studied parameters were kept constant, and the immobilisation conditions were optimised by switching to the other study with the best result. The immobilisation of catalase on chitosan was performed as described below according to the optimisation results determined. About 60 mg of chitosan (powder or flakes, white to beige, from shrimp shells, ≥75% (deacetylated)) was added to 20 mL of 0.1 M HCl containing 2% glutaraldehyde (the purpose of adding this solution was to dissolve chitosan and bind glutaraldehyde). The mixture was stirred slowly on a magnetic stirrer for 1 h at room temperature until completely dissolved. To re-precipitate chitosan, 1 mL of 0.1 M NaOH was added, and the precipitate formed was filtered through filter paper and washed with distilled water to remove excess glutaraldehyde. Thus, an immobilisation matrix that is insoluble in aqueous media has been obtained. Normal photographs of the matrix before and after immobilisation are shown in Supplementary file Figure S1. About 3 mL of 0.49 mg·mL−1 enzyme solution was added to the washed chitosan and mixed slowly for 2 h. Afterward, it was washed abundantly with distilled water to remove the unbound proteins [41,42,43]. The immobilisation yield (%) was calculated as follows:

where X is the activity of free catalase before immobilisation, and Y is the total activity of the catalase in the filtrate and wash water after immobilisation [44].

2.10 Optimum pH and temperature

The optimum pH values of free CAT and CAT-Glu-Cts were determined using 50 mM glycine-HCl (pH 2.0–3.0), 50 mM Na-acetate (pH 4.0–5.0), and 50 mM phosphate (pH 6.0–7.0). The value at which the enzyme showed the highest activity was accepted as 100%, and the pH-relative activity (%) graph was drawn [45]. To determine the optimum temperature of free CAT and CAT-Glu-Cts, the enzyme activity was measured in the range of 20°C to 70°C (10°C increase). The temperature at which the enzyme displayed the best activity was taken as 100%, and the temperature vs relative activity (%) graph was plotted [14].

2.11 K m and V max

The Lineweaver–Burk plot was used to find the kinetic constants (K m and Vmax) for free CAT and CAT-Glu-Cts [46]. H2O2 (in the range of 0.1–10 mM concentrations) was used as a substrate.

2.12 pH and thermal stability

The pH stability of free CAT and CAT-Glu-Cts was examined by incubating the enzymes at pH 5.0, 7.0, and 8.0. At the selected pH values, the enzyme and buffer were mixed one-to-one and incubated at +4°C for up to 72 h (the enzyme activity was determined every 24 h) [47].

In order to determine thermal stability, free CAT and CAT-Glu-Cts were first placed in a tube and incubated at 40°C, 50°C, and 60°C for 15, 30, 45, and 60 min. Then, it was cooled to room temperature, and the enzyme activity was determined under optimum conditions. The activity of the untreated enzyme was accepted as 100%, and the remaining activities of the incubated enzymes were calculated [47].

2.13 Reusability

To determine the reusability of CAT-Glu-Cts, the enzyme activity was found under optimum conditions. After each activity measurement, CAT-Glu-Cts was washed with the specified buffer, and the enzyme activity was determined again. The first measurement value was accepted as 100%, and the results were evaluated [48].

2.14 Storage stability

The storage stability of free CAT and CAT-Glu-Cts was determined by examining the enzyme activities in the samples taken every 24 h from the enzymes stored at 4°C. The enzyme activity measured on the first day was accepted as 100%, and the results were evaluated as residual activity (%) [49].

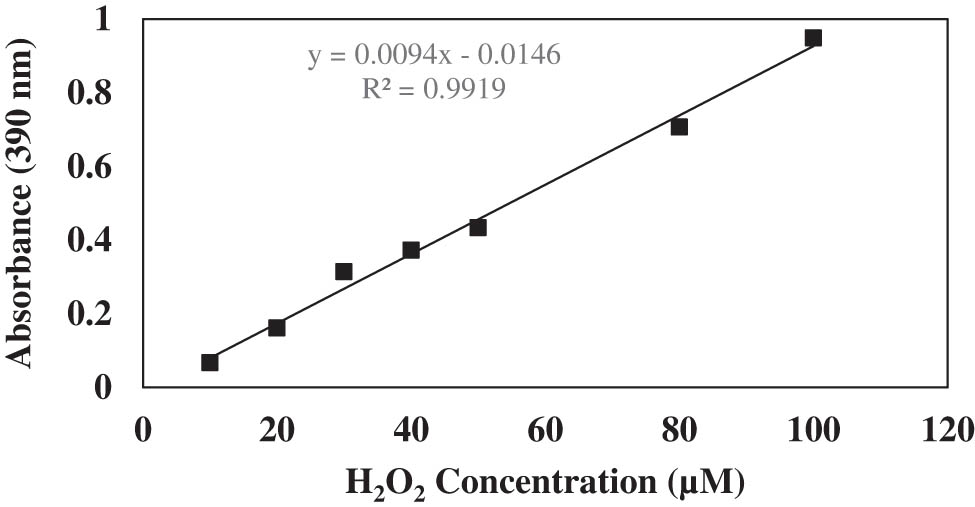

2.15 Hydrogen peroxide removal

The content of H2O2 was determined spectrophotometrically [50]. H2O2 standards in the range of 5–100 µM were prepared. H2O2 solution (artificial wastewater) was prepared at 6 mM 20 mL, 15 mM 20 mL, and 24 mM 20 mL concentrations, and 2 g of CAT-Glu-Cts was added to it. Then, samples were taken from the reaction medium after 30 min, 1, 2, and 24 h. A solution mixture containing 2 mL of 0.1% trichloroacetic acid, 0.2 mL of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and 0.8 mL of 1 M potassium iodide was added to these samples and standards. It was kept on ice for 1 h in the dark, and 390 nm absorbance values were recorded. Using the equation from the H2O2 standard curve, the amount of H2O2 remaining in the medium was calculated.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Purification of CAT with TPP

Studies were carried out for each optimisation parameter in the purification phase of the catalase enzyme with TPP. The results are provided as an supplementary file (Tables S1–S4). The best results for the parameters affecting TPP in the optimisation study were as follows: 30% AS saturation, 1.0:2.0 (crude enzyme extract:t-butanol), pH 5.0 and 30°C, respectively. Finally, the TPP-optimised parameters were applied to 60 mL of the crude enzyme extract, the intermediate phase was dissolved in 20 mL of pH 7.0 phosphate buffer, and a purification table (Table 1) was prepared. The highest catalase yield (%) and purification fold were determined to be 68.10% and 3.02, respectively (Table 1).

Purification of catalase from Hydnum repandum using the TPP system

| Purification step | Volume (mL) | Activity (U·mL−1·min−1) | Total activity | Protein (mg·mL−1) | Total protein (mg) | Specific activity (U·mg−1) | Yield (%) | Purification fold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude enzyme extract | 60.00 | 6.40 | 383.94 | 1.09 | 65.35 | 5.87 | 100.00 | 1.00 |

| TPP System intermediate phase | 20.00 | 13.07 | 261.47 | 0.74 | 14.74 | 17.74 | 68.10 | 3.02 |

Catalase has been purified from various sources using different purification techniques with different purification folds and yields (%). For example, it was partially purified 4.6-fold in 123% yield from Bacillus pumilus using the aqueous two-phase partitioning system (ATPS) method [13]. Catalase was purified in 54.34% yield and 16.67-fold using iron-chelated poly(hydroxyethyl methacrylate-N-methacryloyl-(l)-glutamic acid) (PHEMAGA/Fe3+) discs from rat liver [51]. Kaur et al. purified catalase from potato tuber with a 3.82-fold yield (134%) and from leaf with a 3.81-fold yield (179%) using the TPP method [17].

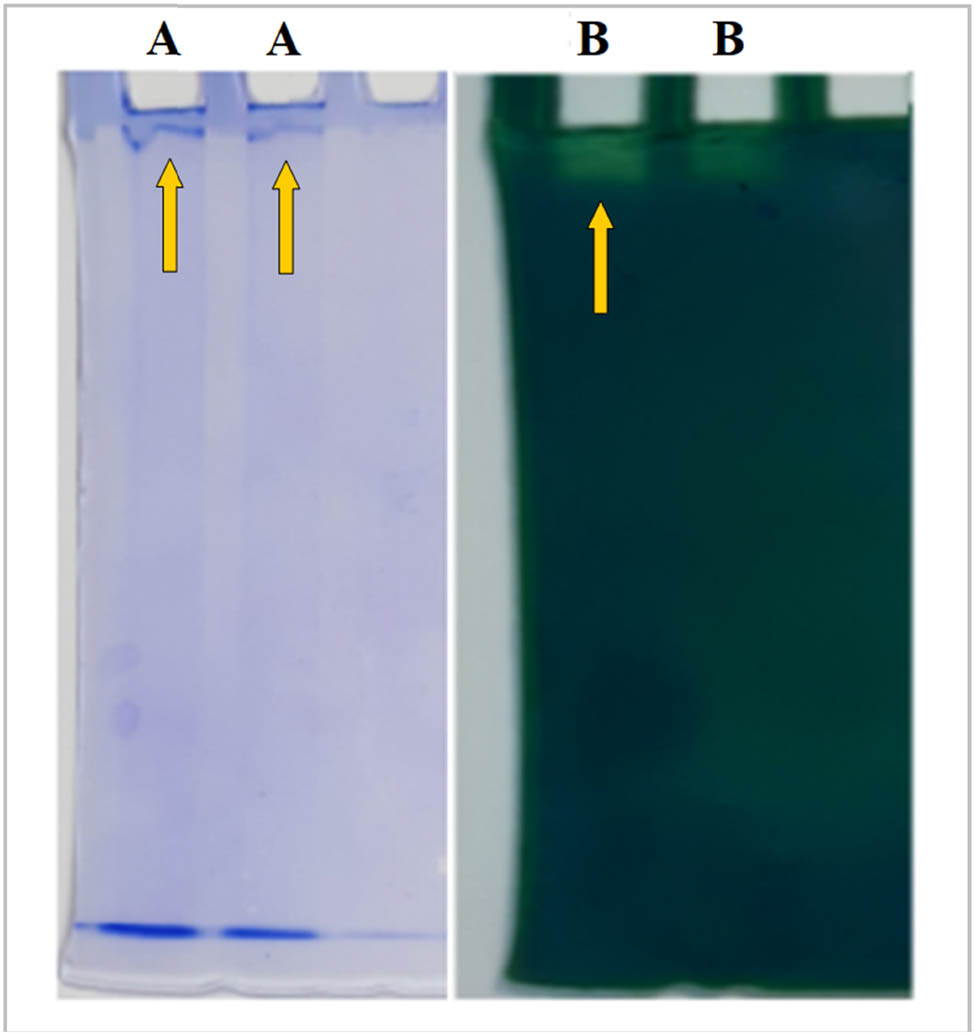

3.2 Native and SDS PAGE

The purity of CAT was determined by performing SDS and native PAGE studies. Figure 1 shows the native PAGE result for the catalase enzyme purified from Hydnum repandum. The presence of only one band in both substrate and Coomassie Brilliant Blue R250 staining indicates that we have successfully purified the enzyme. Our results are in agreement with previous reports [52,53].

Native-PAGE images: (a) Coomassie Brilliant Blue-R250 staining for CAT purified from Hydnum repandum. (b) Substrate staining for CAT purified from Hydnum repandum.

As a result of SDS-PAGE, the molecular weight log Mw vs Rf plot of the CAT purified from Hydnum repandum was drawn, and a single band with a weight of approximately 77.62 kDa was determined (Figure 2). In the literature, the molecular weights of catalases have been reported as a single band in the range of 44–79 kDa by SDS-PAGE [13,22,34,51,52,53].

SDS-PSGE images: (a) protein standard, (b) coomassie Brilliant Blue-R250 staining for CAT purified from Hydnum repandum, and (c) Log MW-Rf graph used to calculate the molecular weight.

3.3 Enzyme immobilisation

3.3.1 Optimisation of catalase immobilisation

Chitosan is soluble in an acidic solution, and crosslinking with glutaraldehyde is a good way to make chitosan more stable in both alkaline and acidic environments [54]. Therefore, covalent immobilisation of enzymes on glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan is a widely used immobilisation technique in the literature, and the possible mechanism of immobilisation of catalase on glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan is shown in Figure 3 [55,56]. In this study, Hydnum repandum catalase was immobilised on glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan using the covalent method for the first time. This method was preferred because it is simple, cheap, and highly efficient. In addition, since the immobilised catalase was used to remove H2O2, care was taken to ensure that the matrix would not be affected by acidic and alkaline environments and that it was a biocompatible material. Data are not given for each parameter, but the parameters with which the best results were obtained are given. Catalase was immobilised on glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan, as described in Section 2.9. Optimisation procedures of the parameters affecting the immobilisation efficiency were studied, and the immobilisation process was carried out with the values that gave the best results, and the immobilisation yield (%) was calculated as 75%.

Possible mechanism of covalent immobilisation of glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan catalase.

The surface morphologies of Glu-Cts and CAT-Glu-Cts were analysed by SEM (Figure 4). Comparing the SEM images before and after immobilisation, the presence of small formations that were not present on the surface before immobilisation was revealed by immobilisation (Figure 4). We can say that these small white formations, which are not homogeneous on the surface with immobilisation, are due to enzyme immobilisation. In the literature review, surface morphology changes are similar to those in this study [57,58].

SEM images: (a) Glu-Cts and (b) CAT-Glu-Cts.

FTIR spectra can be used to determine the structure of the molecule. FTIR is the preferred method for interpreting ligament changes before and after immobilisation [12,25]. The FTIR spectra of Glu-Cts (Figure 5) can be attributed to O–H stretching, which is the characteristic peak of the chitosan adsorption band at 3,285 cm−1 [59]. The adsorption bands at 1,000 and 1,153 cm−1 can be attributed to the monosaccharide structure in the polysaccharide. The adsorption band at 1,640 cm−1 can be attributed to the characteristic peak of C═N formed by the crosslinking reaction between Cts and Glu [25,60]. The adsorption band at 3,285 cm−1 after catalase immobilisation can be attributed to O–H stretching, which is the characteristic peak of chitosan [59]. In addition, adsorption bands at 1,576 and 1,642 cm−1 appeared on the enzyme-immobilised surface, which can be attributed to the presence of catalase in the matrix [12,25,61]. FTIR and SEM results show that the enzyme immobilisation was successful.

FTIR spectrum (--- Glu-Cts, ─ CAT-Glu-Cts).

3.4 Determination of the optimum pH

The optimum pH of free CAT and CAT-Glu-Cts was determined for different pH values between 4.0 and 9.0 using H2O2 as substrate. The optimum pH of free CAT and CAT-Glu-Cts was determined to be the pH 7.0 phosphate buffer (Figure 6). The optimum pH of CAT-Glu-Cts did not change. However, it showed higher activity in both the acidic and alkaline ranges. The reason for the loss of activity of both free and immobilised catalase at low pH values (pH 3–4) may be due to the change in conformation of the enzyme as a result of different loading of amino acid residues on the enzyme and new arrangements of intramolecular hydrogen bonding at these pH values. In addition, the activity of immobilised catalase may be due to changes in the structure of chitosan at low pH [12,62]. As the structure of chitosan is more stable under alkaline conditions, the CAT-Glu-Cts activity was better. Takio et al. showed in their study that catalase from Sechium edule was immobilised on chitosan beads, and the optimum pH values of free and immobilised enzymes were 7.6. They reported that the immobilised catalase activity showed less sensitivity to pH with immobilisation [63].

Optimum pH (--- free CAT, ─ CAT-Glu-Cts).

3.5 Optimum temperature

In order to determine the effect of temperature on free CAT and CAT-Glu-Cts, investigations were carried out at temperatures between 20°C and 70°C. The optimum temperature for free CAT and CAT-Glu-Cts was found to be 30°C (Figure 7). However, the immobilised enzyme showed better activity than the free enzyme at high temperatures. This was possibly due to the restriction of the conformational structure of the enzyme with immobilisation, which increased the stability of the enzyme against factors that reduce its activity [24]. Akkuş-Çetinus and Öztop reported that catalase was immobilised on crosslinked chitosan beads, the optimum temperature of both free and immobilised enzyme was found to be 35°C, and the immobilised catalase showed higher activity than free catalase. In addition, they reported that immobilised catalase had increased stability against denaturation at high temperatures [64].

Optimum temperature (--- free CAT, ─ CAT-Glu-Cts).

3.6 K m and V max

The values of the Michaelis constant (K m) and the maximum reaction rate (V max) of free CAT and CAT-Glu-Cts in the presence of H2O2 substrate were calculated using the Lineweaver–Burk plots. Table 2 shows K m, V max, and V max / K m values and compares the results with other studies in the literature. The K m and V max values of free CAT were found to be 16 mM and 10 × 103 EU/mg, respectively (Figure 8). The K m and V max values of CAT-Glu-Cts were calculated to be 50 mM and 2.5 × 105 EU/mg, respectively (Figure 9). The K m value is a measure of the affinity of an enzyme for its substrate, and a low K m value indicates a high affinity between enzyme and substrate [65]. As shown in Table 2, the affinity of the immobilised enzyme for H2O2 decreased. The increase in K m due to immobilisation may be due to conformational changes, steric effects, or reduced accessibility of the substrate to the immobilised catalase [65,66,67]. However, the V max of the enzyme increased after immobilisation. This increase in V max of the immobilised enzyme can be explained by conformational and micro-environmental changes [66]. The catalytic efficiency ratio (V max/K m) was considered as a criterion to determine the specificity of the substrates. In this study, the catalytic efficiency (V max/K m) values were 625 U·mg protein−1·mM−1 for free enzyme and 5,000 U·mg protein−1·mM−1 for immobilised enzyme, and the catalytic efficiency of immobilised enzyme increased 8 times compared to free enzyme. These results showed that the catalytic efficiency was significantly increased by immobilisation.

A comparison between the K m and V max values found in this study and other studies available in the literature

| Enzyme source | Free catalase K m (mM) and V max (U·mg protein−1) | Support | İmmobilised catalase K m (mM) and V max (U·mg protein−1) | V max/K m·(U·mg protein−1·mM−1) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus subtilis | 11.25 ± 2.3 and 2500 ± 238 | CAT/PDDA/wool fabrics | 222.2 ± 3 6.5 and 1,000 ± 102 | [68] | |

| Bovine liver | 23.3 and 3.5 × 104 | Zr–CF-catalase | 30.2 and 1.3 × 104 | [69] | |

| Bovine liver | 28.6 and 1.4 × 105 | Catalase immobilised by glutaraldehyde (CIG) | 157.3 and 0.8 × 103 | [70] | |

| Catalase immobilised by glutaraldehyde + 6-amino hexanoic acid (CIG-6-AHA) | 25 and 5.1 × 103 | ||||

| Bovine liver | 28.6 ± 3.6 and 1.4(±0.2) × 105 | CAT/Eupergit C | 95.9 ± 0.6 and 3.7(±0.4) × 103 | [38] | |

| Hydnum repandum | 16 and 10 × 103 | Glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan immobilised catalase | 50 and 2.5 × 105 | 5,000 | The present study |

| 625 |

Lineweaver–Burk plot for free CAT.

Lineweaver–Burk plot for CAT-Glu-Cts.

3.7 Investigation of pH and thermal stability

The activities of free and immobilised enzymes are affected by changes in pH during storage. Each enzyme has an optimum pH at which it works best, and enzyme activity generally decreases below and above the optimum pH. In industrial applications of immobilised enzymes, it is important to determine pH stability as the processes are lengthy, and the enzymes are exposed to this environment for long periods of time. To determine the pH stability of free CAT and CAT-Glu-Cts, incubation was carried out at pH 6.0, 7.0, and 8.0 at +4°C for up to 72 h, with activity measured every 24 h. As shown in Figure 10, the immobilised enzyme retained 80.67%, 88.65%, and 70.27% of its activity at pH 6.0, 7.0, and 8.0 after 72 h, whereas the free enzyme lost 45.56%, 35.78%, and 54.34% of its activity at the same pH values. The results indicate that the pH stability of the enzyme increased with immobilisation. It has been reported in the literature that the immobilised catalase enzyme is more stable than the free enzyme in both acidic and alkaline environments [62,71].

pH stability (--- free CAT, ─ CAT-Glu-Cts).

The thermal stability of free CAT and CAT-Glu-Cts is shown in Figure 11. Both free CAT and CAT-Glu-Cts activity retained over 90% after 1 h incubation at 20°C. For CAT and CAT-Glu-Cts, after incubation at 30°C and 40°C for 60 min, free CAT activity lost 43.28% and 59.85%, respectively, and CAT-Glu-Cts activity retained 92.35% and 68.10%. Previous studies have shown that the use of glutaraldehyde as a crosslinking agent during enzyme immobilisation on chitosan makes the immobilised enzyme more resistant to thermal denaturation [72,73].

Thermal stability (--- free CAT, ─ CAT-Glu-Cts).

3.8 Storage stability

Storage stability studies are a good way of showing the changes in the activity of free and immobilised enzymes during storage. The better the storage stability under moderate conditions, the lower the cost of storing the enzyme. In addition, the increase in storage stability of the immobilised enzyme compared to the free enzyme is an indication that it is more usable [12]. To determine the storage stability of free CAT and CAT-Glu-Cts, enzyme activity was monitored periodically for 15 days in 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.0 and 4°C. During this period, CAT-Glu-Cts retained 70.61% of its initial activity, while free CAT retained 20.35% (Figure 12). The storage stability results show that the structure of the enzyme is better preserved by covalent immobilisation of Hydnum repandum catalase on glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan. Catalase immobilised on chitosan films pretreated with glutaraldehyde by Akkuş Çetinus and Öztop. They reported that the free enzyme stored in pH 7.0 phosphate buffer at 5°C retained about 50% of its activity for 18 days, while immobilised catalase retained about 50% of its activity for 25 days [74].

Storage stability (--- free CAT, ─ CAT-Glu-Cts).

3.9 Reusability

The reusability of the immobilised enzyme is an important factor for industrial enzymes to demonstrate economic viability. To determine the reusability of CAT-Glu-Cts, the activity of the enzyme was repeated 6 times. As shown in Figure 13, CAT-Glu-Cts retained 73.80% of its activity at the second use and 53.98% at the fifth use. A decrease in enzyme activity may be due to deactivation of the enzyme as a result of repeated exposure to H2O2 or due to changes in the structure of the matrix [75,76]. The results showed that the immobilised enzyme was more stable and had more advantages than the free enzyme. Similar results have been found in previous studies in the literature. For example, Arabaci and Usluoğlu immobilised catalase on chitosan beads and investigated the reusability of the immobilised catalase, and reported that 50% of the activity remained at the end of the sixth cycle [77]. Inanan immobilised catalase on chitosan copolymer nanostructures and showed that the immobilised catalase retained approximately 50.52% of its activity after 12 uses [78]. In another study, Inanan et al. immobilised catalase on oxime-functional cryogel disks and found that it retained 68.4% of its activity after 10 uses and 34.4% after 15 uses [66].

Reusability.

3.10 H2O2 removal

Generally, the amount of H2O2 remaining after H2O2 removal by immobilised catalase is determined using YSI Model 57 oxygenmeter and 5739 Model dissolved oxygen probe [24], colorimetric measurement [21], a digital flowmeter [20], KMnO4 titration [3], and spectrophotometry methods [18]. It is important that the method applied to detect remaining H2O2 in the environment is repeatable, simple, economical, reliable, and does not require additional devices. The spectrometric method is one of the common techniques, simple, economical, and does not require expertise compared to other methods [79]. In the literature, spectrophotometric H2O2 quantity is determined by using the standard graph of H2O2 created at 230 nm [18]. However, more specific studies are needed when considering substances that give 230 nm absorbance in wastewater. Spectrophotometric determination of H2O2 with KI is an alternative method [50]. As far as we have seen in the literature, this method has not been preferred so far in the detection of remaining H2O2 in H2O2 removal studies with immobilised catalase. For these reasons, the determination of the H2O2 concentration remaining in the environment after H2O2 removal of CAT-Glu-Cts in water was investigated using the spectrophotometric method suggested by Alexieva et al. [50]. The amount of H2O2 remaining in the environment after H2O2 removal from wastewater with CAT-Glu-Cts was calculated using the H2O2 standard curve (Figure 14), and the results are given in Table 3 as % H2O2 removal. The results show that CAT-Glu-Cts was found to have high H2O2 removal. Yildiz et al. immobilised bovine liver catalase onto cellulose acetate beads by the entrapping method and used it to decompose hydrogen peroxide. They detected the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide with a biosensor and reported that 78% of 0.003% hydrogen peroxide was decomposed in 10 min, while 22% of 0.1% hydrogen peroxide was decomposed in 10 min [24]. Jannat and Yang immobilised bovine liver catalase using the on-tubing surface covalent immobilisation method and examined the % H2O2 decomposition by determining the remaining H2O2 concentration in the environment by the titration method. They found that all 0.1 wt% H2O2 decomposed within 3 h [3].

H2O2 standard chart.

H2O2 % removal of CAT-Glu-Cts

| H2O2 concentration (mM) | H2O2% removal after 30 min | H2O2% removal after 1 h | H2O2% removal after 2 h | H2O2% removal after 24 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 73.2 | 89.26 | 96.9 | 98.95 |

| 15 | 70.75 | 89.92 | 96.42 | 99.67 |

| 24 | 69.2 | 88.88 | 96.05 | 99.78 |

4 Conclusions

In this study, catalase was purified from Hydnum repandum using the TPP method and successfully immobilised catalase on glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan by the covalent method with high immobilisation efficiency. The catalytic efficiency was significantly increased by immobilisation. The pH, thermal, and storage stability were improved after immobilisation, and the H2O2% removal by immobilised catalase was investigated using a different approach. In conclusion, CAT-Glu-Cts has a highly effective H2O2 removal potential. These results show that immobilised catalase is a candidate with potential for commercial use in various industrial processes, especially in H2O2 removal.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Iğdır University (BAP, Project No: TBY0422Y09) for their financial support.

-

Funding information: This study was supported by Iğdır University Scientific Research Projects Coordinatorship (Project No. TBY0422Y09).

-

Author contributions: Ayşe Türkhan: writing – original draft, writing – review & editing, methodology, formal analysis, project administration, visualisation, and supervision. Işıl Nur Tabaru: formal analysis, visualisation, and writing – original draft.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Additional Info: This study was produced from Işıl Nur TABARU’s master’s thesis.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Shen H, Liu H, Wang X. Surface construction of catalase-immobilized Au/PEDOT nanocomposite on phase-change microcapsules for enhancing electrochemical biosensing detection of hydrogen peroxide. Appl Surf Sci. 2023;612:155816. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.155816.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Murphy M, Theyagarajan K, Thenmozhi K, Senthilkumar S. Quaternary ammonium based carboxyl functionalized ıonic liquid for covalent ımmobilization of horseradish peroxidase and development of electrochemical hydrogen peroxide biosensor. Electroanal. 2020;32(11):2422–30. 10.1002/elan.202060240.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Jannat M, Yang KL. A millifluidic device with embedded crosslinked enzyme aggregates for degradation of H2O2. ACS Appl Mater Inter. 2020;12(5):6768–75. 10.1021/acsami.9b21480.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Giaretta JE, Duan H, Oveissi F, Farajikhah S, Dehghani F, Naficy S. Flexible sensors for hydrogen peroxide detection: A critical review. ACS Appl Mater Inter. 2022;14(18):20491–505. 10.1021/acsami.1c24727.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Baltar F, Reinthaler T, Herndl GJ, Pinhassi J. Major effect of hydrogen peroxide on bacterioplankton metabolism in the northeast atlantic. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61051. 10.1371/journal.pone.0061051.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Trusek-Holownia A, Noworyta A. Catalase immobilized in capsules in microorganisms removal from drinking water, milk, and beverages. Desalin Water Treat. 2015;55(10):2721–7. 10.1080/19443994.2014.939857.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Wu T, Englehardt JD. A new method for removal of hydrogen peroxide interference in the analysis of chemical oxygen demand. Env Sci Technol. 2012;46(4):2291–98. 10.1021/es204250k.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Hua Z, Yan G, Du G, Chen J. Study and improvement of the conditions for production of a novel alkali stable catalase. Biotechnol J. 2007;2(3):326–33. 10.1002/biot.200600146.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Yang L, Yu P, Li W, Cao F, Jin X, Xue S, et al. Co-N graphene encapsulated cobalt catalyst for H2O2 decomposition under acidic conditions. AICHE J. 2022;68(9):e17760. 10.1002/aic.17760.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Hasnat MA, Rahman MM, Borhanuddin SM, Siddiqua A, Bahadur NM, Karim MR. Efficient hydrogen peroxide decomposition on bimetallic Pt-Pd surfaces. Catal Commun. 2010;12(4):286–91. 10.1016/j.catcom.2010.10.001.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Doǧaç YI, Çinar M, Teke M. Improving of catalase stability properties by encapsulation in alginate/Fe3O4 magnetic composite beads for enzymatic removal of H2O2. Prep Biochem Biotech. 2015;45(2):144–57. 10.1080/10826068.2014.907178.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Kaushal J, Seema, Singh G, Arya SK. Immobilization of catalase onto chitosan and chitosan–bentonite complex: A comparative study. Biotechnol Rep. 2018;18:e00258. 10.1016/j.btre.2018.e00258.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Yuzugullu Karakus Y, Isik S. Partial characterization of Bacillus pumilus catalase partitioned in poly(ethylene glycol)/sodium sulfate aqueous two-phase systems. Prep Biochem Biotech. 2019;49(4):391–9. 10.1080/10826068.2019.1573197.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Bilgin Sökmen B, Ahiskali A. Giresun yöresinde yetişen fındık mantarı (Lactarius pyragalus)’ndan katalaz enziminin saflaştırılması ve karakterizasyonu. Karadeniz Fen Bilim Derg. 2017;7(1):53–65.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Dennison C, Lovrien R. Three phase partitioning: Concentration and purification of proteins. Protein Expression Purif. 1997;11(2):149–61. 10.1006/prep.1997.0779.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Alici EH, Arabaci G. Purification of polyphenol oxidase from borage (Trachystemon orientalis L.) by using three-phase partitioning and investigation of kinetic properties. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;93:1051–6. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.09.070.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Kaur G, Sharma S, Das N. Comparison of catalase activity in different organs of the potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) cultivars grown under field condition and purification by three-phase partitioning. Acta Physiol Plant. 2020;42:1–11. 10.1007/s11738-019-3002-y.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Trusek-holownia A, Noworyta A. Efficient utilisation of hydrogel preparations with encapsulated enzymes – a case study on catalase and hydrogen peroxide degradation. Biotechnol Rep. 2015;6:13–9. 10.1016/j.btre.2014.12.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Misra N, Goel NK, Shelkar SA, Varshney L, Kumar V. Catalase immobilized-radiation grafted functional cellulose matrix: A novel biocatalytic system. J Mol Catal B-Enzym. 2016;133:S172–8. 10.1016/j.molcatb.2017.01.001.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Yoon DS, Won K, Kim YH, Song BK, Kim SJ, Moon SJ, et al. Continuous removal of hydrogen peroxide with immobilised catalase for wastewater reuse. Water Sci Technol. 2007;55(1–2):27–33. 10.2166/wst.2007.016.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Lida T, Maruyama D, Fukunaga K. Stabilization of entrapped catalase using photo-crosslinked resin gel for use in wastewater containing hydrogen peroxide. J Chem Technol Biot. 2000;75(11):1026–30. 10.1002/1097-4660(200011)75:11<1026::AID-JCTB306>3.0.CO;2-Y.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Kavakçioǧlu B, Tarhan L. Initial purification of catalase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium by partitioning in poly(ethylene glycol)/salt aqueous two phase systems. Sep Purif Technol. 2013;105:8–14. 10.1016/j.seppur.2012.12.011.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Susmitha S, Ranganayaki P, Vidyamol KK, Vijayaraghavan R. Purification and characterization of catalase enzyme from Agaricus bisporus original research article purification and characterization of catalase enzyme from agaricus bisporus. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2013;2(12):255–63.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Yildiz H, Akyilmaz E, Dinçkaya E. Catalase immobilization in cellulose acetate beads and determination of its hydrogen peroxide decomposition level by using a catalase biosensor. Artif Cell Blood Sub. 2004;32(3):443–52. 10.1081/BIO-200027507.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Çetinus ŞA, Şahin E, Saraydin D. Preparation of Cu(II) adsorbed chitosan beads for catalase immobilization. Food Chem. 2009;114(3):962–9. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.10.049.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Gan JS, Ashraf SS, Bilal M, Iqbal HMN. Biodegradation of environmental pollutants using catalase-based biocatalytic systems. Env Res. 2022;214(P2):113914. 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113914.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Zayed MEM, Obaid AY, Almulaiky YQ, El-Shishtawy RM. Enhancing the sustainable immobilization of laccase by amino-functionalized PMMA-reinforced graphene nanomaterial. J Env Manage. 2024;351:119503. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119503.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Balabushevich NG, Kovalenko EA, Maltseva LN, Filatova LY, Moysenovich AM, Mikhalchik EV, et al. Immobilization of antioxidant enzyme catalase on porous hybrid microparticles of vaterite with mucin. Adv Eng Mater. 2022;24(9):1–9. 10.1002/adem.202101797.Search in Google Scholar

[29] El-Shishtawy RM, Ahmed NSE, Almulaiky YQ. Immobilization of catalase on chitosan/ZnO and chitosan/ZnO/Fe2O3 nanocomposites: A comparative study. Catalysts. 2021;11(7):1–13. 10.3390/catal11070820.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Almulaiky YQ, Khalil NM, Algamal Y, Al-Gheethi A, Aissa A, Al-Maaqar SM, et al. Optimization of biocatalytic steps via response surface methodology to produce ımmobilized peroxidase on chitosan-decorated AZT composites for enhanced reusability and storage stability. Catal Lett. 2023;153(9):2543–57. 10.1007/s10562-022-04185-y.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Başak E, Aydemir T, Dinçer A, Becerik SÇ. Comperative study of catalase immobilization on chitosan, magnetic chitosan and chitosan-clay composite beads. Artif Cell Nanomed B. 2013;41(6):408–13. 10.3109/10731199.2013.796312.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Guibal E. Interactions of metal ions with chitosan-based sorbents: A review. Sep Purif Technol. 2004;38(1):43–74. 10.1016/j.seppur.2003.10.004.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Baykal Sarı E, Yüzügüllü Karakuş Y. Aspergillus niger katalazının üretimi, üçlü-faz ayırma ile saflaştırılması ve biyokimyasal karakterizasyonu. Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi Fen Bilim Enstitüsü Derg. 2020;24(1):12–24. 10.19113/sdufenbed.559988.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Duman YA, Kaya E. Three-phase partitioning as a rapid and easy method for the purification and recovery of catalase from sweet potato tubers (Solanum tuberosum). Appl Biochem Biotech. 2013;170(5):1119–26. 10.1007/s12010-013-0260-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Yaman M. Purification of peroxidase from chard (Beta vulgaris L. var. cicla) by three phase partitioning method. Master’s Thesis. Istanbul University; 2018.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72(1–2):248–54. 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Aebi H. [13] Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymology. 1984;105:121–26. 10.1016/S0076-6879(84)05016-3.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Alptekin Ö, Tükel SS, Yildirim D, Alagöz D. Immobilization of catalase onto Eupergit C and its characterization. J Mol Catal B-Enzym. 2010;64(3–4):177–83. 10.1016/j.molcatb.2009.09.010.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–85. 10.1038/227680a0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Woodbury W, Spencer AK, Stahmann MA. An improved procedure using ferricyanide for detecting catalase isozymes. Anal Biochem. 1971;44(1):301–5.10.1016/0003-2697(71)90375-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Ohtakara A, Mitsutomi M. Immobilization of thermostable α-galactosidase from Pycnoporus cinnabarinus on chitosan beads and its application to the hydrolysis of raffinose in beet sugar molasses. J Ferment Technol. 1987;65(4):493–8. 10.1016/0385-6380(87)90149-X.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Abdel-Naby MA, Sherif AA, El-Tanash AB, Mankarios AT. Immobilization of Aspergillus oryzae tannase and properties of the immobilized enzyme. J Appl Mıcrobıol. 1999;87(1):108–14. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00799.x.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Maalej-Achouri I, Guerfali M, Gargouri A, Belghith H. Production of xylo-oligosaccharides from agro-industrial residues using immobilized Talaromyces thermophilus xylanase. J Mol Catal B-Enzym. 2009;59(1–3):145–52. 10.1016/j.molcatb.2009.02.003.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Hou C, Wang Y, Zhu H, Wei H. Construction of enzyme immobilization system through metal-polyphenol assisted Fe3O4/chitosan hybrid microcapsules. Chem Eng J. 2016;283:397–403. 10.1016/j.cej.2015.07.067.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Kolcuoǧlu Y. Purification and comparative characterization of monophenolase and diphenolase activities from a wild edible mushroom (Macrolepiota gracilenta). Process Biochem. 2012;47(12):2449–54. 10.1016/j.procbio.2012.10.008.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Lineweaver H, Burk D. The determination of enzyme dissociation constants. J Am Chem Soc. 1934;56(3):658–66. 10.1021/ja01318a036.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Kolcuoğlu Y, Kuyumcu I, Colak A. A catecholase from Laccaria laccata a wild edible mushroom and its catalytic efficiency in organic media. J Food Biochem. 2018;42:e12605. 10.1111/jfbc.12605.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Aslan GY. Synthesis, characterization of porous copper microspheres and investigation of the usage for catalase immobilization. Master’s Thesis. Erciyes University; 2021.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Arica MY, Bayramoǧlu G, Biçak N. Characterisation of tyrosinase immobilised onto spacer-arm attached glycidyl methacrylate-based reactive microbeads. Process Biochem. 2004;39(12):2007–17. 10.1016/j.procbio.2003.09.030.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Alexieva V, Sergiev I, Mapelli S, Karanov E. The effect of drought and ultraviolet radiation on growth and stress markers in pea and wheat. Plant Cell Env. 2001;24(12):1337–44. 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2001.00778.x.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Göktürk I, Perçin I, Denizli A. Catalase purification from rat liver with iron-chelated poly(hydroxyethyl methacrylate-N-methacryloyl-(l)-glutamic acid) cryogel discs. Prep Biochem Biotech. 2016;46(6):602–9. 10.1080/10826068.2015.1085400.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Ghanem MME, Mohamed MA, Abd-Elaziz AM. Distribution, purification and characterization of a monofunctional catalase from Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (Olivier) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2019;23:101480. 10.1016/j.bcab.2019.101480.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Kang YS, Lee DH, Yoon B, Oh DC. Purification and characterization of a catalase from photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum S1 grown under anaerobic conditions. J Microbiol. 2006;44(2):185–91.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Freeman A, Dror Y. Immobilization of ‘Disguised’ yeast in chemically crosslinked chitosan beads. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1994;44(9):1083–8. 10.1002/bit.260440909.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Žuža MG, Milašinović NZ, Jonović MM, Jovanović JR, Kalagasidis Krušić MT, Bugarski BM, et al. Design and characterization of alcalase–chitosan conjugates as potential biocatalysts. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2017;40:1713–23. 10.1007/s00449-017-1826-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Juang RS, Wu FC, Tseng RL. Use of chemically modified chitosan beads for sorption and enzyme immobilization. Adv Env Res. 2002;6(2):171–7. 10.1016/S1093-0191(00)00078-2.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Singh AN, Singh S, Suthar N, Dubey VK. Glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan matrix for immobilization of a novel cysteine protease, procerain B. J Agr Food Chem. 2011;59(11):6256–62. 10.1021/jf200472x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[58] Gür SD, İdil N, Aksöz N. Optimization of enzyme co-ımmobilization with sodium alginate and glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan beads. Appl Biochem Biotech. 2018;184:538–52. 10.1007/s12010-017-2566-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] Liu XF, Guan YL, Yang DZ, Li Z, De Yao K. Antibacterial action of chitosan and carboxymethylated chitosan. J Appl Polym Sci. 2001;79(7):1324–35. 10.1002/1097-4628(20010214)79:7<1324::AID-APP210>3.0.CO;2-L.Search in Google Scholar

[60] Öztop HN, Saraydin D, Cetinus Ş. pH-sensitive chitosan films for baker’s yeast immobilization. applied biochemistry and biotechnology. Appl Biochem Biotech. 2002;101:239–49.10.1385/ABAB:101:3:239Search in Google Scholar

[61] Wei XL, Ge ZQ. Effect of graphene oxide on conformation and activity of catalase. Carbon. 2013;60:401–9. 10.1016/j.carbon.2013.04.052.Search in Google Scholar

[62] Doǧaç YI, Teke M. Immobilization of bovine catalase onto magnetic nanoparticles. Prep Biochem Biotech. 2013;43(8):750–65. 10.1080/10826068.2013.773340.Search in Google Scholar

[63] Takio N, Yadav M, Barman M, Yadav HS. Purification, characterization, immobilization and kinetic studies of catalase from a novel source Sechium edule. Int J Chem Kinet. 2021;53(5):596–610. 10.1002/kin.21468.Search in Google Scholar

[64] Akkuş-Çetinus Ş, Nursevin-Öztop H. Immobilization of catalase into chemically crosslinked chitosan beads. Enzyme Microb Tech. 2003;32(7):889–94. 10.1016/S0141-0229(03)00065-6.Search in Google Scholar

[65] Sel E, Ulu A, Ateş B, Köytepe S. Comparative study of catalase immobilization via adsorption on P(MMA-co-PEG500MA) structures as an effective polymer support. Polym Bull. 2021;78:2663–84. 10.1007/s00289-020-03233-0.Search in Google Scholar

[66] Inanan T, Tüzmen N, Karipcin F. Oxime-functionalized cryogel disks for catalase immobilization. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;114:812–20. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.04.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[67] Kumar A, Patel SK, Mardan B, Pagolu R, Lestari R, Jeong SH, et al. Immobilization of xylanase using a protein-inorganic hybrid system. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;28(4):638–44. 10.4014/jmb.1710.10037.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[68] Liu J, Wang Q, Fan XR X, Sun J, Huang PH. Layer-by-Layer self-assembly immobilization of catalases on wool fabrics. Appl Biochem Biotech. 2013;169:2212–22. 10.1007/s12010-013-0093-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[69] Song N, Chen S, Huang X, Liao X, Shi B. Immobilization of catalase by using Zr(IV)-modified collagen fiber as the supporting matrix. Process Biochem. 2011;46(11):2187–93. 10.1016/j.procbio.2011.09.001.Search in Google Scholar

[70] Alptekin Ö, Seyhan-Tükel S, Yildirim D, Alagöz D. Covalent immobilization of catalase onto spacer-arm attached modified florisil: Characterization and application to batch and plug-flow type reactor systems. Enzyme Microb Tech. 2011;49(6–7):547–54. 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2011.09.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[71] Zhao B, Zhou L, Ma L, He Y, Gao J, Li D, et al. Co-immobilization of glucose oxidase and catalase in silica inverse opals for glucose removal from commercial isomaltooligosaccharide. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;107:2034–43. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.10.074.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[72] Wilson L, Betancor L, Fernández-Lorente G, Fuentes M, Hidalgo A, Guisán JM, et al. Crosslinked aggregates of multimeric enzymes: A simple and efficient methodology to stabilize their quaternary structure. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5(3):814–7. 10.1021/bm034528i.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[73] Costa SA, Tzanov T, Carneiro F, Gübitz GM, Cavaco-Paulo A. Recycling of textile bleaching effluents for dyeing using immobilized catalase. Biotechnol Lett. 2002;24:173–76. 10.1023/A:1014136703369.Search in Google Scholar

[74] Akkuş Çetinus Ş, Öztop HN. Immobilization of catalase on chitosan film. Enzyme Microb Tech. 2000;26(7):497–501. 10.1016/S0141-0229(99)00189-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[75] Chang KLB, Tai MC, Cheng FH. Kinetics and products of the degradation of chitosan by hydrogen peroxide. J Agr Food Chem. 2001;49(10):4845–51. 10.1021/jf001469g.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[76] Lardinois OM, Mestdagh MM, Rouxhet PG. Reversible inhibition and irreversible inactivation of catalase in presence of hydrogen peroxide. BBA-Protein Struct M. 1996;1295(2):222–38. 10.1016/0167-4838(96)00043-X.Search in Google Scholar

[77] Arabaci G, Usluoğlu A. Immobilization of catalase from red poppy on chitosan beads. J Multidiscip Eng Sci Stud. 2016;2(1):236–40.Search in Google Scholar

[78] Inanan T. Chitosan Co-polymeric nanostructures for catalase immobilization. React Funct Polym. 2019;135:94–102. 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2018.12.013.Search in Google Scholar

[79] Wang H, Wang J, Wang J, Zhu R, Shen Y, Xu Q, et al. Spectroscopic method for the detection of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid based on its inhibitory effect towards catalase immobilized on reusable magnetic Fe3O4-chitosan nanocomposite. Sens Actuators B-Chem. 2017;247:146–54. 10.1016/j.snb.2017.02.175.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications