Abstract

Nanoemulsions (NEMs) are more stable and permeable than regular emulsions because of their increased surface area and smaller particle sizes, which are stabilized by emulsifiers and consist of nanometer-sized droplets. Utilization of an olive oil nanoemulsion (NEM-olive oil) loaded with silver nanoparticles (Ag-NPs) derived from marine alga Turbinaria turbinata may be effective against microorganisms and cancer cell lines. NEM-olive oil was made by mixing olive oil, surfactant (Span:Tween (28:72)), and D water (1:4:5). The marine alga Turbinaria turbinata was used for the synthesis of Ag-NPs (Tu-Ag-NPs), and combined with NEM-olive oil (1:1) to synthesize Ag-NPs loaded in olive oil–water nanoemulsion (Ag/NEM-olive oil). Transmission electron microscopy, energy-dispersive X-ray analysis, zeta potential, Fourier transform infrared, and X-ray powder diffraction spectroscopy were used to characterize the nanoparticles. Both NEM-olive oil and Ag/NEM-olive oil nanoparticles showed a negative surface charge and small diameter. The major components of NEM-olive oil are dodecanoic acid, 2-penten-1-yl ester, 9-octadecenoic acid, and oleic acid. All tested nanoparticles exhibited anticancer activity against the CACO-2 cell line and Hep G2, and antimicrobial activities against E. faecalis, S. aureus, E. coli, and C. albicans. The present research suggested that olive oil NEM loaded with marine algae Ag-NPs can be a safe and economical anticancer, antimicrobial, and drug delivery.

1 Introduction

Cancer is an atypical type of tissue proliferation in which cells divide erratically, resulting in a gradual increase in the number of dividing cells [1]. Cancer is a common disorder among people worldwide [2]. Despite the discovery of several chemical and natural drugs for the treatment of cancer, it is still the most dangerous disease in the world, causing mortality in many people [3]. The detection of new anticancer drugs with low-danger effects has become an essential and critical target in many studies [3,4]. A large number of essential oils have been used in many in vitro studies to influence a variety of breast cancer cells [5]. A variety of valuable components are found in olive oil, which could be useful for the inhibition or possible treatment of cancer [6].

Olive oil contains monounsaturated fatty acids, which may be accompanied by a decreased risk of some cancers, and mainly phenolic compounds that have antioxidant activities [7]. Biologically synthesized silver nanoparticles (Ag-NPs) specifically have a wide range of medicinal applications that minimize toxicity and cost and are found to be exceptionally stable [8]. It has been observed that Ag-NPs have cytotoxic effects through an increase in ROS production associated with DNA damage, apoptosis, and necrosis [9].

Many bioactive compounds can be used in the synthesis of nanoparticles, such as caffeic acid, which acts as a reducing agent for the reduction of Ag+ into Ag-NPs [10]. Ag-NPs can be fabricated using a mixture of glucose and CTAB in the presence of ammonia [11]. Cyanidin 3,5-di-O-glucoside extracted from the red-orange rose petals was used effectively in synthesized gold nanoparticles and displayed excellent inhibitory effect against S. aureus, E. coil, and Candida [12]

Algae play a major role in the biosynthesis of Ag-NPs with a small size range, which opens the door for using Ag-NPs as anticancer agents [13]. Ag-NPs are biogenic by the marine brown alga Padina pavonia with high stability and rapid formation with small sizes ranging from 49.58 to 86.37 nm [14]. Ag-NPs bio-fabricated by polysaccharides were extracted from brown algae and showed a spherical shape, small size, pronounced cytotoxicity toward rat glioma cells, and antibacterial activities [15]. The alginate extracted from Laminaria ochroleuca brown alga was a good reducing and stabilizing agent in the biosynthesis of Ag-NPs, which exhibited remarkable antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [16]. The Ag-NPs were fabricated using laminarin extracted from Turbinaria ornata and exhibited cytotoxicity in retinoblastoma Y79 cell lines [17]. The edible marine brown alga aqueous extract of Ecklonia cava is a useful reducing agent for the environmentally friendly synthesis of Ag-NPs with potent antioxidant, antibacterial, and anticancer properties against human cervical cancer cells [18]. The brown alga Padina tetrastromatica can be used for eco-friendly and useful biosynthesis of antimicrobial Ag-NPs against Bacillus sp. Bacillus subtilis, Klebsiella planticola, and Pseudomonas sp. [19]. Shanthi et al. [20] demonstrated the potential applications of fucoidan-coated anionic Ag-NPs derived from Turbinaria decurrens in medicines. The Ag-NPs biosynthesized by the brown alga Sargassum wightii have good enzyme inhibitory, antioxidant, and antibacterial effects [21]. Ag-NPs synthesized by olive oil exhibited maximum antibacterial activity against Klebsiella pneumonia and Ag-NPs biosynthesized by olive oil could be used as a safe natural consequence against multidrug-resistant bacteria [22]. Ag-NPs loaded in the tea tree oil nanoemulsion (TTO NEM) were an efficient antimicrobial agent for the management of infections and multidrug-resistant bacteria (MDRB) [23]. Green synthesized Ag-NPs loaded in various herbal oils (oil-in-water nanoemulsion technique) showed anticancer activity against MCF-7 human breast cancer, and these nanoparticles have been established in various biomedical treatments such as cosmetics [24]. Chitosan-capped silver sols (Chit/Ag-NPs) exhibited higher antimicrobial activities against Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans than those with pure chitosan [25].

This is a new study on the synthesis of olive oil water nanoemulsion, and it is loaded in Ag-NPs green synthesis by brown marine alga Turbinaria turbinata, characterizations, and the evaluation of the effects of olive oil water nanoemulsion, and its loaded in green synthesis Ag-NPs as anticancer, antioxidant, and antibacterial activities.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

The marine alga Turbinaria turbinata was collected from Jeddah Beach, Saudi Arabia (KSA), cleaned, washed with tap water, followed by DD water, and dried in the shade, followed by grinding and drying in an electrical oven at 60°C, until a constant weight was obtained. Pure olive oil was purchased from Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (KSA). All chemicals used were of analytical grade and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Company.

2.2 Algal extract

One gram of air-dried T. turbinata was blended with 100 mL of deionized (DD) water, boiled for 1 h, and then cooled and filtered.

2.3 Biosynthesis of Tu-Ag-NPs

About 0.17 g of AgNO3 was mixed with 90 mL of DD water, and 10 mL of the algal extract was added dropwise using a magnetic stirrer at 60°C, until the color changed to dark brown [26].

2.4 Nanoemulsion synthesis

A mixture of Span 80 and Tween 80 (28:72) was chosen as the surfactant and mixed thoroughly under magnetic stirring. Approximately 4 ml of the surfactant was added to 1 g of olive oil, mixed well, and then 5 mL of water was added dropwise under magnetic stirring for 15 min.

2.5 Nanoemulsion loaded in Tu-Ag-NPs

Subsequently, Tu-Ag-NPs (2 mg·mL−1) were mixed with the previously synthesized nanoemulsion under magnetic stirring [23].

2.6 Nanoparticle characterization

2.6.1 UV spectrophotometry

Spectroscopic methods were used to analyze the nanoparticles and nanoparticles loaded with bioactive compounds [27,28]. UV-Vis spectroscopy (ATI Unicam 5625 UV/VIS Vision Software V3.20) was used to determine the surface plasmon absorption (SPR) of the biogenic Tu-Ag-NPs

2.6.2 Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

Nanoemulsion and Tu-Ag-NP-loaded nanoemulsion were characterized by FTIR spectroscopy) using an FT-IR 5300 spectrophotometer (JASCO Europe S.r.l, Cremella, Italy), in the range between 400 and 4,000 cm−1

2.6.3 X-ray powder diffraction (XRD)

The crystalline or amorphous nanoemulsion and Tu-Ag-NP-loaded nanoemulsion were characterized using an X-ray diffractometer (PAN Analytical X-Pert PRO, Spectris plc, Almelo, The Netherlands).

2.6.4 Zeta potential analysis

Zeta potential analysis afforded the details of the stabilization of nanoemulsion, and Tu-Ag-NP-loaded nanoemulsion was analyzed using a Malvern Zeta size Nano-Zs90 (Malvern, Westborough, PA, USA).

2.6.5 Energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS)

The surface morphology and elemental contents of nanoemulsions and Tu-Ag-NP-loaded nanoemulsions were examined using a field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with energy-dispersive spectroscope (JEOL JSM-6510/v, Tokyo, Japan).

2.6.6 Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The particle sizes and shapes of the nanoemulsion and Tu-Ag-NP-loaded nanoemulsion were determined using TEM (JEOL JSM-6510/v, Tokyo, Japan).

2.6.7 GC-MS analysis of the nanoemulsion

The chemical composition of the nanoemulsion was determined using a Trace GC1310-ISQ mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Austin, TX, USA) at the Regional Center for Mycology and Biotechnology at Al-Azhar University. The column used was TG–5MS (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm film thickness), with the initial and final temperatures being 35–280°C, which was increased by 3°C·min−1 to 200°C. Helium was used as a carrier, and the volume of the injected sample was 1 µL. The ion source temperature was set to 200°C. The compounds were recognized by the WILEY 09 and NIST 11 mass spectral databases.

2.7 Free radical scavenging activity (DPPH)

Approximately 1 ml of different concentrations (20, 40, 80, 160, and 200 µg·mL−1) of each Tu-Ag-NPs, NEM-olive oil, and Ag/NEM-olive oil was added to the DPPH solution (4 ml, 0.004% methanolic solution). After 30 min of incubation at room temperature, the absorbance of the mixture was measured at 517 nm [29]

2.8 Cell culture

RPMI-1640 was used to maintain the CACO-2 cell line in a human colon cancer patient. Both cell lines were grown in the cell culture unit at the Center for Drug Discovery Research and Development at the College of Pharmacy, Ain Shams University. Human liver cancer (Hep G2) was maintained in DMEM-high glucose. In a humidified atmosphere with 5% (v/v) CO2 at 37°C, both media were supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 µg·mL−1 streptomycin.

2.9 Cytotoxicity assay

The test substance (dissolved in DMSO) was maintained at a stock concentration of 1,000,000 µg·mL−1. The cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 2, 000 cells/well. For 72 hours, the cells were subjected to various treatments, and five distinct nanoemulsions containing varying quantities of Tu-Ag-NPs were investigated. Following drug exposure, cytotoxicity was evaluated using the SRB assay as previously described [30]. Absorbance was measured at 545 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Vermont, USA). The relative absorbance percentage of the control was used to express the results. The experiments were conducted in triplicate. The concentration at which 50% growth inhibition was achieved, known as the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50), was determined using GraphPad Prism software, version 5.00 (Graph Pad Software, Inc. La Jolla, CA, USA).

2.10 Antimicrobial activities

The antimicrobial activity of the nanoparticles was established against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 29212) (Gram-positive bacteria), and also Escherichia coli ATCC 35218 (Gram-negative bacteria) and Candida albicans ATCC 76615 (fungus). The strains were obtained from the Microbiology Laboratory, King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Jeddah, KSA.

Antibacterial and antifungal properties were screened using the agar diffusion technique. Briefly, six holes (4 mm in diameter) were cut into the seeded agar plates, and Muller-Hinton agar Petri dishes (150 mm) were inoculated with various microbial strains (cfu 106). To determine the lowest inhibitory concentration, 50 μL of each sample at different concentrations was added to the wells. The Petri dishes were incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Inhibitory activity was measured using the clear zone around the holes (mm). To determine the MIC, different concentrations were prepared for each formulation (2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.125, 0.0625 mg·mL−1) and tested against different bacterial strains and fungi.

2.11 Statistical analysis

All data were obtained in triplicate and are presented as the designed mean and standard error (mean ± SD). Statistical analysis (ANOVA and Duncan’s multiple comparison test) was performed using SPSS software (version 16.0, professional edition). The level of significance was defined as p < 0.05.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of nanoparticles

3.1.1 UV spectroscopy

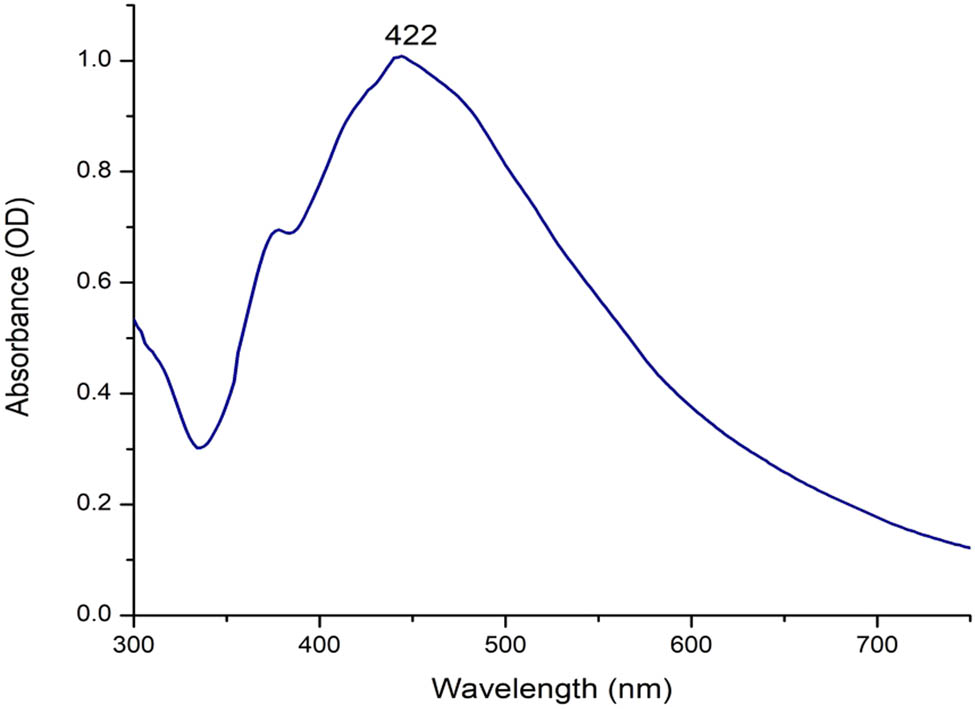

Biogenic Ag-NPs were obtained using T. turbinata brown marine alga extract; the reactions occurred after a few minutes and were indicated by a change in color to brown. T. turbinata extract was used as the reducing and stabilizing agent. The variation in color was attributed to the excitation of the SPR of biogenic Tu-Ag-NPs. The UV-Vis absorption spectrum of Tu-Ag-NPs was observed at 422 nm (Figure 1). A single peak was obtained at 428 nm for Ag-NPs biosynthesized using T. turbinata collected from the Red Sea, Safaga, Egypt [31]. The absorption spectrum of Ag-NPs synthesized using Turbinaria conoides showed peaks at 420 nm [32], 421 nm [33], and 452 nm [34], which revealed the formation of Ag-NPs (Figure 2).

UV-visible absorption spectra of Tu-Ag-NPs bio-fabricated using the aqueous extract of T. turbinata brown alga (T. turbinata alga was used as a reducing and stabilizing agent, and the reaction was conducted at 60°C using magnetic stirring).

FT-IR spectra analysis of NEM-olive oil (4 ml of surfactant: 1 g of olive oil: 1 g of olive oil mixed well with a magnetic stirrer for 15 min).

3.1.2 FTIR spectra analysis of NEM-olive oil

Figure 2 shows the ATR-FTIR spectra of NEM-olive oil. It exhibits 13 peaks: the broad peak at 3,343 cm−1 was attributed to the stretching of the O–H group [35]. The weak peaks at 2,919 and 2,852 cm−1 were assigned to the alkyl chains (CH2), which agree with the results of nanoemulsion (oleic acid) [36]. The band at 1,813 cm−1 represented NO [37]. The band at 1,737 cm−1 indicated C═O stretching vibration for lipids [38]. The quinoid ring (C═O) was observed at 1,637 cm−1, and also observed in the nanoemulsion stabilized with Tween 80 [39]. The peak at 1,462 cm−1 may denote the band of C–O–H bending in the nanoemulsion [40]. The band at 1,348 cm−1 indicated NO2 [41]. The C–N stretching of amine was observed at 1,245 cm−1 [42], and the band at 948 cm−1 was assigned to the C–C group [43]. The peak at 581 cm−1 with other peaks, such as those at 3,418, 1,646, 1,383, and 1,121 cm−1, confirmed the formation of the spinel structure and oleic acid [44]. The results in Figure 3 show the ATR-FTIR spectra of the Ag/NEM-olive oil. The results denote the small differences in the peak positions about those found in NEM-olive oil without Ag-NP loading. The peak at 3,339 cm−1 was assigned to the stretching of the O–H group [45], and the sharp peak at 2,917 cm−1 was assigned to the –CH stretching [46]. The small peak at 2,854 cm−1 indicates the deformation of membrane phospholipids [47]. The peak at 1,358 cm−1 was assigned to the symmetric carboxylate stretching [48]. The peak at 1,077 cm−1 was assigned to the C–O band [49]. The band at 600 cm−1 was attributed to PO4 [50].

FT-IR spectra analysis of Ag/NEM-olive oil and Tu-Ag-NPs mixed with the nanoemulsion (1:1) at ambient temperature.

3.1.3 X-ray diffraction

Figure 4 shows the X-ray diffraction patterns of the NEM-olive oil and Ag/NEM-olive oil. The results demonstrate that no peaks appeared in the crystalline patterns for NEM-olive oil; in contrast, when Ag-NPs were loaded in NEM-olive oil, crystalline peaks appeared at 2θ = 4.23°, 6.28°, and 8.34°, which were assigned to Miller indices 110, 111, and 200, respectively. The NEM-olive oil has an amorphous structure, and Ag nanocrystalline is loaded by an amorphous state. The XRD results and overall assessment of the carbonated hydroxyapatite nanoemulsions (CHAp) showed an amorphous state [51]. The solid nanoemulsion preconcentrate of paclitaxel (PAC) using oil is molecularly dispersed or in an amorphous state in the matrix [52]. According to XRD analysis, the crystallinity of Ketotifen fumarate (KF) loaded by nanoemulsion was reduced, which was noticed by the loss of most peaks in the nanoparticles related to the drug [53]. The results of the X-ray diffractogram indicated crystalline Carvedilol; however, the nanoemulsion Carvedilol possessed an amorphous state in which no crystalline peaks were observed [54].

X-ray diffraction of NEM-olive oil (a) and Ag/NEM-olive oil (b).

3.1.4 Zeta potential analysis

Figure 5 shows the zeta potential analysis of NEM-olive oil and Ag/NEM-olive oil. The results indicate that the surface charge of NEM-olive oil has a negative charge (−19.8 mV), and the negative charge increases when Ag-NPs were loaded in NEM-olive oil to form Ag/NEM-olive oil (−35.5 mV). Repulsion among the nanoparticles and superior constancy may be due to the negative charge of the nanoparticles, and the stability of the nanoparticles is postulated by negative charges that block aggregation and agglomeration [24]. Zeta potential measurements revealed that loading Ag NPs in tree oil nanoemulsion (TTO NEM) initiates zeta potential variations from −17.75 to −29.24 mV, which possibly advances the stability of tree oil nanoemulsion [23]. Andrographolide-loaded nanoemulsions (AG-NEMs) have a negative charge [55]. The improved hyaluronic acid established nanoemulsion formula showed a zeta potential of −23.9 mV [56]. The stability of nanoemulsions differs according to the oil types that are used in the synthesis of nanoemulsions; nanoemulsion-containing lemon grass, or mandarin EO present a high stability during storage of 56 days; however, the oregano or thyme EO-pectin nanoemulsions were unstable over storage [57]. A pomegranate seed oil (PSO) nanoemulsion loaded with α-tocopherol can be used as a delivery system with good features under severe environmental conditions [58]. The citrus essential oil (CEO) nanoemulsion had good stability during 200-day storage, which is of great significance for long-term preservation in the food industry [59].

Zeta potential of NEM-olive oil (a) and Ag/NEM-olive oil (b). Comparison between surface charges of the nanoparticles (c).

3.1.5 TEM images

Figures 6 and 7 display the TEM images and particle distributions of NEM-olive oil and Ag/NEM-olive oil. The image shows that the morphological NEM-olive oil is polydispersive and spherical, with sizes ranging from 7 to 15 nm (Figure 7a). The most predominated size ranged from 12.6 to 13.4 nm. The images of Ag/NEM-olive oil denote the polydispersed particles, spherical in shape, with a size ranging from 3 to 10.2 nm. The TEM image of tree oil nanoemulsion (TTO NEM) and Ag nanoparticle-loaded nanoemulsion demonstrated average sizes of 17.5 and 4.5 nm with spherical [23]. The Ag-NP nanoemulsions were spherical [60]. The combination of nanosilver and nanoemulsions produced Ag/nanoemulsions with an average size ranging from 42.9 to 135.5 nm [61]. TEM image proved that Ag-NPs were adsorbed/distributed in nanoemulsions. Moghtader et al. [62] reported that Ag-NPs were adsorbed/distributed on the pure-cotton fabrics nanoemulsion.

TEM images of NEM-olive oil (a, b) and Ag/NEM-olive oil (c, d). The emulsion-encapsulated Ag-NPs.

Particle size distributions of NEM-olive oil (a) and Ag/NEM-olive oil (b).

3.1.6 Energy dispersive X-ray (EDS)

Figure 8 shows the energy dispersive X-ray (EDS) measurements and SEM images of the Ag/NEM-olive oil. Carbon, oxygen, sodium, magnesium, silicon, calcium, and silver were present at 66.93, 33.09, 0.13, 0.08, 0.01, 0.09, and 0.7 wt%, respectively. Oxygen and carbon were predominant at 33.09 and 66.93 wt%, but in the case of Ag, they were 0.7 wt%, which denotes the low amount of silver loaded in the nanoemulsion. An Ag peak was observed at 3 keV. In the energy-dispersive X-ray analysis, the peak observed at 3 keV corresponds to the binding energy of Ag Lω [63]. The peak for silver was observed at 3 keV, which is predictable for the absorption of metallic silver nanocrystalline [64].

SEM image (a) and the energy dispersive X-ray (EDS) measurement (b) of Ag/NEM-olive oil.

3.1.7 Phytochemical analysis

Phytochemical screening was performed to determine the presence of the most active compounds that were found in NEM-olive oil (Table 1). GC-MS analysis revealed the following major phytochemical compounds with percentages:dodecanoic acid, 2-penten-1-yl ester, 9-octadecenoic acid, prostaglandin A1-biotin, acetic acid, 2-acetoxymethyl-1,2,3-trimethylbutyl ester, oleic acid, dotriacontane, dodecanoic acid, hexadecanoic acid, 1-(1-methylethyl)-1,2-ethanediyl ester, octadecanoic acid, palmitic acid tetramethylene ester, hexadecanoic acid, 1-(1-methylethyl)-1,2-ethanediyl ester, isosorbide, tetradecanoic acid, and hexadecanoic acid at 13.35, 8.56, 6.71, 5.75, 4.97, 4.82, 4.43, 3.49, 3.04, 2.71, 2.46, 2.44, 2.21, and 2%, and there were many compounds where the percentage was <2%. All the identified compounds are classified as fatty acids except some compounds, such as isosorbide, which are classified as diols and prostaglandin A1-biotin as lipophilic. The compounds in the nanoemulsion have biological activities such as antimicrobial, anticancer, antiviral, antioxidant, and antiproliferative effects (Table 1).

Ingredients of olive oil-nanoemulsion

| Rt | Compounds | Formula | Area % | Classification | Advantages | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23.31 | Isosorbide | C6H10O4 | 2.44 | Diols | Biomedical engineering materials | [65] |

| 27.52 | Decanoic acid | C10H20O2 | 0.25 | Saturated fatty acid | Antibacterial activity | [66] |

| 35.89 | Dodecanoic acid | C12H24O2 | 4.43 | Saturated fatty acid | Antimicrobial activity | [67] |

| 36.04 | Dodecanoic acid, ethyl ester | C14H28O2 | 0.41 | Saturated fatty acid | Antibacterial, antiviral, and antioxidant | [68] |

| 42.64 | Tetradecanoic acid | C14H28O2 | 2.21 | Saturated fatty acid | Larvicidal efficacy | [69] |

| 43.23 | Tetradecanoic acid, ethyl ester | C16H32O2 | 0.24 | Saturated fatty acid | Used in cosmetics | [70] |

| 8.11 | 9-Hexadecenoic acid | C16H30O2 | 0.45 | Unsaturated fatty acid | Anti-inflammatory | [71] |

| 48.72 | Octanoic acid, oct-3-en-2-yl ester | C18H36O2 | 1.18 | Saturated fatty acid | Antimicrobial | [72] |

| 49.08 | Hexadecanoic acid | C16H32O2 | 2.00 | Unsaturated fatty acid | Anti-inflammatory | [71] |

| 50.40 | Octanoic acid, oct-3-en-2-yl ester | C23H46O2 | 0.79 | Saturated fatty acid | Antimicrobial | [72] |

| 54.61 | Oleic acid | C18H34O2 | 4.97 | Unsaturated fatty acid | Antimicrobial activity | [73] |

| 55.42 | Octadecanoic acid | C18H36O2 | 3.04 | Saturated fatty acid | Anticancer | [74] |

| 62.81 | Dodecanoic acid, 2-penten-1-yl ester | C17H32O2 | 13.35 | Saturated fatty acid | Antimicrobial activity | [75] |

| 64.31 | Acetic acid, 2-acetoxymethyl-1,2,3-trimethylbutyl ester | C12H22O4 | 5.57 | Organic acid | Antimicrobial activities | [76] |

| 65.63 | Hexadecanoic acid | C19H38O4 | 0.87 | Unsaturated fatty acid | Anti-inflammatory | [71] |

| 68.77 | Prostaglandin A1-biotin | C35H58N4O5S | 6.71 | lipophilic molecule | Antiproliferative effects | [77] |

| 69.14 | Octadecanoic acid | C39H76O5 | 0.73 | Saturated fatty acid | Anticancer | [74] |

| 70.06 | Dotriacontane | C18H30D6O | 4.82 | n-alkane | Activation of human neutrophils | [78] |

| 70.72 | 9-Octadecenoic acid | C21H40O4 | 8.56 | Saturated fatty acid | Antibacterial | [79] |

| 71.2 | Octadecanoic acid | C19H38O4 | 1.18 | Saturated fatty acid | Anticancer | [74] |

| 72.64 | 9-Octadecenamide | C22H43NO | 1.45 | Fatty amide | Antioxidative and hypolipidemic | [80] |

| 73.89 | Dotriacontane | C18H16O7 | 1.16 | n-alkane | Activation of human neutrophils | [78] |

| 74.04 | Hexadecanoic acid, 1-(1-methylethyl)-1,2-ethanediyl ester | C37H72O5 | 3.49 | Unsaturated fatty acid | Anti-inflammatory | [71] |

| 75.15 | Hexadecanoic acid | C37H72O4 | 1.93 | Unsaturated fatty acid | Anti-inflammatory | [71] |

| 78.83 | Hexadecanoic acid, 1-(1-methylethyl)-1,2-ethanediyl ester | C37H72O5 | 2.46 | Unsaturated fatty acid | Anti-inflammatory | [71] |

| 79.82 | Hexadecanoic acid, 1-[[[(2-aminoethoxy)hydroxyphosphinyl]oxy]methyl] -1,2-ethanediyl ester | C37H74NO8 | 1.87 | Unsaturated fatty acid | Anti-inflammatory | [71] |

| 83.25 | Oleic acid, eicosyl ester | C38H74O2 | 0.73 | Unsaturated fatty acid | Antimicrobial activity | [73] |

| 83.80 | Oleic acid, eicosyl ester | C38H74O2 | 0.65 | Unsaturated fatty acid | Antimicrobial activity | [73] |

| 92.19 | Palmitic acid, tetramethylene ester | C36H70O4 | 2.71 | Saturated fatty acid | Antimicrobial activity | [81] |

3.2 Antioxidant activity

The DPPH assays were used to evaluate the free-radical-scavenging potential to compare Tu-Ag-NPs, NEM-olive oil, and Ag/NEM-olive oil (Figure 9). The results show that Tu-Ag-NPs have the highest antioxidant at low concentrations compared to those of NEM-olive oil and Ag/NEM-olive oil. However, at the highest concentrations (40–200 µg·mL−1), the Ag/NEM-olive oil possessed higher antioxidant activities than Tu-Ag-NPs and NEM-olive oil. The results demonstrate the values are not significant between Tu-Ag-NPs and Ag/NEM-olive oil at 160 µg·mL−1; in contrast, the values are significant between Tu-Ag-NPs and Ag/NEM-olive oil when the concentrations increased to 200 µg·mL−1. The increased concentration of olive nanoemulsions was accompanied by enhanced antioxidant activity [82]. Olive oil can be used to formulate nanoemulsions. Such emulsions would be beneficial because of their greater antioxidant activity, derived from olive oil, in addition to providing a means of delivery to foods [83]. Olive oil is composed of many antioxidants to entrap the radicals such as O2˙−, RO˙, and OH˙. Therefore, olive oil is used to avoid autoxidation of curcumin in aqueous preparations in the form of oil-in-water nanoemulsions and is also used as an anticancer agent because of its antioxidant activities [84].

Antioxidant activities of Tu-Ag-NPs, NEM-olive oil, and Ag/NEM-olive oil. Bars represent error bars, and different letters denote significant values.

3.3 Anticancer activity

The cytotoxic activity of Tu-Ag-NPs, NEM-olive oil, and Ag/NEM-olive oil was examined in cancer cell lines, such as human colon cancer CACO-2 and human liver cancer (Hep G2). The results shown in Figure 10a demonstrate the inhibitory effect of Tu-Ag-NPs on human colon cancer CACO-2 and human liver cancer (Hep G2). The IC50 of Tu-Ag-NPs on human colon cancer CACO-2 and human liver cancer (Hep G2) was 2.375 and 2.214 µg·mL−1, respectively. The biosynthesis of Ag-NPs by Guiera senegalensis leaf extract possessed anticancer activities against Hep G2 with IC50 (33.25 μg·mL−1) [85]. An increase in Brassica Ag-NP concentrations increased the reserve of Caco-2 cells [86]. The inhibitory effect of Ag-NPs may be related to their size because of their cytotoxic effect, which is caused by their interference with cellular proteins and the induction of changes in their chemistry. Additionally, small nanoparticles in cancer cells may contribute to this effect [26].

(a) Effect of Tu-Ag-NPs on human colon cancer CACO-2 and human liver cancer (Hep G2). (b) Effect of NEM-olive oil on two different cancer cell lines, human colon cancer CACO-2 and human liver cancer (Hep G2). (c) Effect of Ag/NEM-olive oil on two different cancer cell lines, human colon cancer CACO-2 and human liver cancer (Hep G2).

Figure 10b shows the cytotoxic effects of different concentrations of NEM-olive oil against CACO-2 and Hep G2. The results demonstrate that all tested concentrations (0.1–1,000 µg·mL−1) of NEM-olive oil possessed anticancer activities against CACO-2 and Hep G2, and the same effects were observed in two types of cancer. Eugenol (EU) and eugenol-loaded nanoemulsions (EU NEs) caused inhibition effects against both HB8065 and HTB-37, and the inhibition effect due to the ROS of EU and EU NEs triggers apoptosis [87]. Nigella sativa L. nanoemulsion reduces the viability of hepatocellular carcinoma cells and enhances ROS intensity and chromatin condensation [88]. The MTT assay revealed IC50 values of 283.3 and 227 µg·mL−1 for clove essential oil and clove essential oil nanoemulsions against CACO-2 [89].

The results in Figure 10c reveal the cytotoxic effect of Ag/NEM-olive oil on cancer cell lines, CACO-2, and Hep G2. The results clearly show that Ag/NEM-olive oil caused cytotoxicity against CACO-2 and Hep G2. There was a significant difference at low concentrations of 1 µg·mL−1 Ag/NEM-olive oil between cell lines CACO-2 and Hep G2. The highest concentrations (10, 100, and 1,000 µg·mL−1) of Ag/NEM-olive oil exhibited the same inhibition effect against CACO-2 and Hep G2. Ag nanoparticles in oil-in-water nanoemulsion possessed anticancer activity against MCF-7 human breast cancer cells [24]. Table 2 shows the IC50 of tested nanoparticles against CACO-2 and Hep G2. The results showed that Ag/NEM-olive oil caused more anticancer activity against CACO-2 than Tu/Ag-NPs, which possessed low IC50, while the reverse results were obtained with Hep G2. The IC50 in NEM-olive oil against CACO-2 was not detected due to high activities against the cancer cell line and possessed low IC50 in the case of Hep G2 (1.36 µg·mL−1).

IC50 (µg·mL−1) of Tu/Ag-NPs, NEM-olive oil, and Ag/NEM-olive oil

| Treatments | Tu/Ag-NPs | NEM-olive oil | Ag/NEM-olive oil |

|---|---|---|---|

| CACO-2 | 2.375 ± 0.061 | ND | 2.196 ± 0.54 |

| Hep-G2 | 2.214 ± 0.067 | 1.36 | 2.608 ± 0.133 |

ND. Not detected.

3.4 Antimicrobial activities

Different concentrations (2–0.0032 mg·mL−1) of Tu-Ag-NPS, NEM-olive oil, and Ag/NEM-olive oil were tested against S. aureus and E. faecalis (Gram-positive bacteria) and also E. coli (Gram-negative bacteria) and C. albicans (fungus) by measuring the inhibition zone (Table 3). The results demonstrated that Tu-Ag-NPs, NEM-olive oil, and Ag/NEM-olive oil exerted antimicrobial activities against all tested bacteria and fungi. The MIC values differed according to the type of microorganism and nanoparticles. The MIC value of Tu-Ag-NPs and Ag/NEM-olive oil against S. aureus and E. coli was 0.0065 mg·mL−1, and MIC values with NEM-olive oil were 0.025 and 0.0125 against S. aureus and E. coli, respectively. The MIC value of NEM-olive oil and Ag/NEM-olive oil was 0.0065 mg·mL−1, and the MIC value of Tu-Ag-NPs against E. faecalis (ATCC 29212) was 0.025 mg·mL−1. The MIC values of Tu-Ag-NPs, NEM-olive oil, and Ag/NEM-olive oil were 0.0125, 0.1, and 0.025 mg·mL−1, respectively. Figure 11 and demonstrate the effect of Tu-Ag-NPs, NEM-olive oil, and Ag/NEM-olive oil against S. aureus, E. faecalis, E. coli, and C. albicans. The significant effects of the tested nanoparticles differed according to the nanoparticle type and tested microorganisms. The results demonstrated that Tu-Ag-NPs and Ag/NEM-olive oil possessed the same effect against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213. There were significant differences between NEM-olive oil and Ag/NEM-olive oil against E. faecalis, but the highest effect was observed for Tu-Ag-NPs. The lowest inhibitory activities of Tu-Ag-NPS and Ag/NEM-olive oil were against Escherichia coli ATCC 35218. The highest inhibition zone of all treated microorganisms was observed with Tu-Ag-NPs against C. albicans. Nanoemulsions with a size of 7 nm were effective against MDR Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli [90]. Phytosphingosine nanoemulsions (Ps-NEs) exhibit broad antimicrobial activity against bacteria and yeast [91]. These results are in agreement with Rosato et al. [92], who reported that the nanoemulsion containing Carlina acaulis L (EO-NEM) exhibited antibacterial activities against Gram (+) bacteria with MIC values ranging between 7.5 and 60 mg·mL−1 mg·mL−1, while lower values of MIC were obtained against Gram-negative strains. The transformation of thyme oil to a nanoemulsion improved antibacterial activity against food-borne pathogens, which damaged bacterial cell membranes after the nanoemulsion treatment [93]. The nanoemulsion formulation affected Staphylococcus aureus through changes in the cell wall composition and cell shape, reducing the respiration of the bacterial cell and promoting potassium leakage from the cell permeability to the cytoplasmic contents [94]. The transformation of olive oil to a nanoemulsion boosted its antimicrobial activity against all tested microorganisms Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus, E. coli, Salmonella typhi, and Candida albicans [82]. Chouhan et al. [95] summarized the mechanism of the effect of nanoemulsion against microorganisms through induced leakage, disruption of the cell membrane, inhibition of ergosterol biosynthesis, permeabilized membrane, and cell wall damage. The nanoemulsion droplets accumulate in the epidermis and dermis of the cells and can interact directly and disrupt organisms at the site of infection, killing pathogens by physical disruption of the cell wall and subsequent lysis of the organism [96].

Antimicrobial activities and MIC of Tu-Ag-NPs, NEM-olive oil, and Ag/NEM-olive oil

| Nanotypes | Microorganisms | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.025 | 0.0125 | 0.0065 | 0.0032 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tu/Ag-NPs | S. aureus | 14 ± 1 | 13.25 ± 1.2 | 13. ± 1.4 | 10.66 ± 0.75 | 10 ± 0 | 8 ± 1 | 0 |

| E. faecalis | 11.66 ± 1.25 | 10 ± 1 | 6.16 ± 0.67 | 5.3 ± 0.75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| E. coli | 11.66 ± 0.88 | 10.75 ± 0.95 | 10 ± 0.81 | 9.75 ± 0.75 | 9 ± 0.81 | 6 ± 0.81 | 0 | |

| C. albicans | 18.33 ± 0.88 | 16.66 ± 0.66 | 15.33 ± 0.33 | 13 ± 0.33 | 5.66 ± 0.33 | 0 | 0 | |

| NEM-olive oil | S. aureus | 12 ± 0 | 9.25 ± 1.7 | 6.75 ± 0.28 | 5.37 ± 0.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| E. faecalis | 16.66 ± 2 | 12.75 ± 1.7 | 11.75 ± 1.15 | 11 ± 0.5 | 10.25 ± 0.5 | 8.75 ± 0.5 | 0 | |

| E. coli | 9 ± 1 | 7.25 ± 1 | 5.25 ± 0.28 | 5.12 ± 0.28 | 5 ± 0.28 | 0 | 0 | |

| C. albicans | 7.5 ± 0.0.5 | 6.66 ± 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ag/NEM-olive oil | S. aureus | 14 ± 0.75 | 12.75 ± 0.95 | 11.25 ± 95 | 10 ± 0 | 9 ± 0 | 7.75 ± 0 | 0 |

| E. faecalis | 16 ± 1 | 13.75 ± 0.66 | 12.25 ± 1.2 | 11.5 ± 0.66 | 10 ± 0.57 | 9 ± 0.57 | 0 | |

| E. coli | 12 ± 1 | 11.25 ± 0.95 | 10.5 ± 0.57 | 9.25 ± 0.95 | 8.25 ± 0.86 | 7.25 ± 1.1 | 0 | |

| C. albicans | 15.33 ± 0.88 | 13.66 ± 0.33 | 12.33 ± 0.33 | 6 ± 0.33 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Antimicrobial activities of Tu-Ag-NPs, NEM-olive oil, and Ag/NEM-olive oil. Bars represent error bar, and different letters denote significant values.

Both metal/metal oxide nanocomposites and essential oils have wide-ranging spectra of bio-activities with antioxidant, anticancer, and antimicrobial activities owing to their diverse sizes, shapes, activities, physical and chemical stability, and high surface-to-volume ratios [97]. Hort et al. [98] reported no changes in biochemical, hematological, oxidative stress, and genotoxicity parameters of male Wistar rats treated with NEMs, once daily for 21 days via oral or intraperitoneal delivery. NEMs significantly improve the bioavailability and bioactivity of hydrophobic bioactives delivered orally, including nutraceuticals, vitamins, healthy fats, and medicines [99]. Oral administration of nanoemulsions loaded with pliartine enhances its solubility, bioavailability, and antitumor efficacy [100].

4 Conclusions

An olive oil nanoemulsion (NEM-Olive oil) was prepared using surfactants such as Tween and Span and homogenized with water using a magnetic stirrer. Ag-NPs were fabricated using the marine brown alga Turbinaria turbinata and loaded on olive oil nanoemulsion (Ag/NEM-olive oil). The TEM image showed a very small size for both NEM-olive oil (7 to 15 nm) and Ag/NEM-olive oil (3.00–10.2 nm). The zeta potential values indicate that Ag/NEM-olive oil possessed more negative charge (−35.5 mV) than NEM-olive oil (−19.8 mV), which proved that Ag/NEM-olive oil was more stable. The nanoparticles showed good anticancer activities against the CACO-2 cell line and Hep G2 in vitro but less than the doxorubicin standard anticancer drug. The nanoparticles showed good antimicrobial activities against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 and Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 29212) (Gram-positive), Escherichia coli ATCC 35218 (Gram-negative), and Candida albicans ATCC 76615 (fungus). The nanoemulsion has good biocompatibility owing to the high content of fatty acids such as hexadecanoic acid, oleic acid, and octadecanoic acid, which was confirmed by GC-MS analysis. Nanoemulsions exhibited a wide range of applications, such as drug delivery, antimicrobial, and anticancer activities, and can also be used in the cosmetic and dermatological fields. Nanoemulsions can be synthesized by low-energy methods with high productivity and robustness, making manufacturing scale-up easy.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the University of Jeddah, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, under grant No. (UJ-23 DR-269). The authors acknowledge the technical and financial support of the University of Jeddah. The authors thank Dr. Khadejah Moeed Alqurni, Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, for providing microorganisms.

-

Funding information: This work was funded by the University of Jeddah, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, under grant No. (UJ-23-DR-269).

-

Author contributions: R.A.H.: conceptualization, data analysis, methodology, validation writing and reviewing; A.A.S.: resources, B.A.E.: antimicrobial methodology and resources.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Hemamalini K, Soujanya GL, Bhargav A, Vasireddy U. In-vivo anticancer activity of Tabebuia rosea (Bertol) Dc. leaves on Dalton,s ascetic lymphoma in mice. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2012;3(11):4496.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Smigal C, et al. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA: A Cancer J Clin. 2006;56(2):106–30.10.3322/canjclin.56.2.106Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Xu H, Yao L, Sun H, Wu Y. Chemical composition and antitumor activity of different polysaccharides from the roots of Actinidia eriantha. Carbohydr Polym. 2009;78(2):316–22.10.1016/j.carbpol.2009.04.007Search in Google Scholar

[4] Kannu KD, Rani KS, Jothi RA, Gowsalya GU, Ramakritinan CM. In-vivo anticancer activity of red algae (Gelidiela acerosa and Acanthophora spicifera). Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2014;5(8):3347.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Magalhães IDFB, Tellis CJM, da Silva Calabrese K, Abreu-Silva AL, Almeida-Souza F. Essential oils, potential in breast cancer treatment: An overview. Essential oils-bioactive compounds, new perspectives and applications. London, United Kingdom: Intech Open; 2020. 10.5772/intechopen.91781.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Borzì AM, Biondi A, Basile F, Luca S, Vicari ESD, Vacante M. Olive oil effects on colorectal cancer. Nutrients. 2019;11(1):32.10.3390/nu11010032Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] López S, Pacheco YM, Bermúdez B, Abia R, Muriana FJ. Olive oil and cancer. Grasas y aceites. 2004;55(1):33–41.10.3989/gya.2004.v55.i1.145Search in Google Scholar

[8] Parashar V, Parashar R, Sharma B, Pandey AC. Parthenium leaf extract mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles: A novel approach towards weed utilization. Dig J Nanomater Biostruct. 2009;4(1):45–50.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Arora M, Kiran B, Rani S, Rani A, Kaur B, Mittal N. Heavy metal accumulation in vegetables irrigated with water from different sources. Food Chem. 2008;111(4):811–5.10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.04.049Search in Google Scholar

[10] Zaheer Z. Solubilization of caffeic acid into the cationic micelles and biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles for the degradation of dye. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2022 Sep;26(5):101529.10.1016/j.jscs.2022.101529Search in Google Scholar

[11] Zaheer Z. Crystal growth of different morphologies (nanospheres, nanoribbons and nanoplates) of silver nanoparticles. Colloids Surf A: Physicochem Eng Asp. 2012 Jan;393:1–5.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2011.08.018Search in Google Scholar

[12] Aazam ES, Zaheer Z. Rose cyanidin 3, 5-di-O-glucoside-assisted gold nanoparticles, their antiradical and photocatalytic activities. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron. 2020 Jun;31:8780–95.10.1007/s10854-020-03413-8Search in Google Scholar

[13] El Bialy BE, Hamouda RA, Khalifa KS, Hamza HA. Cytotoxic effect of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles on Ehrlich ascites tumor cells in mice. Int J Pharmacol. 2017;13(2):134–44.10.3923/ijp.2017.134.144Search in Google Scholar

[14] Abdel-Raouf N, Al-Enazi NM, Ibraheem IBM, Alharbi RM, Alkhulaifi MM. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by using of the marine brown alga Padina pavonia and their characterization. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2019;26(6):1207–15.10.1016/j.sjbs.2018.01.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Yugay YA, Usoltseva RV, Silantev VE, Egorova AE, Karabtsov AA, Kumeiko VV, et al. Synthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles using alginate, fucoidan and laminaran from brown algae as a reducing and stabilizing agent. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;245:116547.10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116547Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Kaidi S, Belattmania Z, Bentiss F, Jama C, Reani A, Sabour B. Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using alginate from the brown seaweed laminaria ochroleuca: structural features and antibacterial activity. Biointerface Res Appl Chem. 2021;12:6046–57.10.33263/BRIAC125.60466057Search in Google Scholar

[17] Remya RR, Rajasree SR, Suman TY, Aranganathan L, Gayathri S, Gobalakrishnan M, et al. Laminarin based AgNPs using brown seaweed Turbinaria ornata and its induction of apoptosis in human retinoblastoma Y79 cancer cell lines. Mater Res Express. 2018;5(3):035403.10.1088/2053-1591/aab2d8Search in Google Scholar

[18] Venkatesan J, Kim SK, Shim MS. Antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer activities of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles using marine algae Ecklonia cava. Nanomaterials. 2016;6(12):235.10.3390/nano6120235Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Rajeshkumar S, Kannan C, Annadurai G. Synthesis and characterization of antimicrobial silver nanoparticles using marine brown seaweed Padina tetrastromatica. Drug Invent Today. 2012;4(10):511–3.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Shanthi N, Arumugam P, Murugan M, Sudhakar MP, Arunkumar K. Extraction of fucoidan from Turbinaria decurrens and the synthesis of fucoidan-coated AgNPs for anticoagulant application. ACS Omega. 2021;6(46):30998–31008.10.1021/acsomega.1c03776Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Deepak P, Amutha V, Birundha R, Sowmiya R, Kamaraj C, Balasubramanian V, et al. Facile green synthesis of nanoparticles from brown seaweed Sargassum wightii and its biological application potential. Adv Nat Sci: Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2018;9(3):035019.10.1088/2043-6254/aadc4aSearch in Google Scholar

[22] Negm S, Moustafa M, Sayed M, Alamri S, Alghamdii H, Shati A, et al. Antimicrobial activities of silver nanoparticles of extra virgin olive oil and sunflower oil against human pathogenic microbes. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2020;33:2285–91. 10.36721/PJPS.2020.33.5.SUP.2285-2291.1.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Najafi-Taher R, Ghaemi B, Kharazi S, Rasoulikoohi S, Amani A. Promising antibacterial effects of silver nanoparticle-loaded tea tree oil nanoemulsion: A synergistic combination against resistance threat. Aaps PharmSciTech. 2018;19:1133–40.10.1208/s12249-017-0922-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Razavi R, Amiri M, Alshamsi HA, Eslaminejad T, Salavati-Niasari M. Green synthesis of Ag nanoparticles in oil-in-water nanoemulsion and evaluation of their antibacterial and cytotoxic properties as well as molecular docking. Arab J Chem. 2021;14(9):103323.10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103323Search in Google Scholar

[25] Zaheer Z. Chitosan-capped silver nanoparticles: fabrication, oxidative dissolution, sensing properties, and antimicrobial activity. J Polym Res. 2021 Sep;28(9):348. 10.1007/s10965-021-02673-0.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Hamouda RA, Alharthi MA, Alotaibi AS, Alenzi AM, Albalawi DA, Makharita RR. Biogenic nanoparticles silver and copper and their composites derived from marine alga Ulva lactuca: Insight into the characterizations, antibacterial activity, and anti-biofilm formation. Molecules. 2023;28:6324. 10.3390/molecules28176324.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Zaheer Z, Kosa SA, Akram M. Interactions of Ag+ ions and Ag-nanoparticles with protein. A comparative and multi spectroscopic investigation. J Mol Liq. 2021 Aug;335:116226.10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116226Search in Google Scholar

[28] Zaheer Z, Kosa SA, Osama M, Akram M. Spectroscopic exploration of binding between novel cationic gemini surfactants and Flurbiprofen. J Mol Liq. 2021 May;329:115507.10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115507Search in Google Scholar

[29] Rinaldi F, Hanieh PN, Longhi C, Carradori S, Secci D, Zengin G, et al. Neem oil nanoemulsions: Characterisation and antioxidant activity. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2017;32(1):1265–73.10.1080/14756366.2017.1378190Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Tolba MF, Abdel-Rahman SZ. Pterostilbine, an active component of blueberries, sensitizes colon cancer cells to 5-fluorouracil cytotoxicity. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15239.10.1038/srep15239Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Khalifa KS, Hamouda RA, Hanafy D, Hamza A. In vitro antitumor activity of silver nanoparticles biosynthesized by marine algae. Dig J Nanomater Biostruct. 2016;11(1):213–21.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Rajeshkumar SH, Kannan C, Annadurai G. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using marine brown algae Turbinaria conoides and its antibacterial activity. Int J Pharma Bio Sci. 2012;3(4):502–10.10.1186/2193-8865-3-44Search in Google Scholar

[33] Vijayan SR, Santhiyagu P, Singamuthu M, Kumari Ahila N, Jayaraman R, Ethiraj K. Synthesis and characterization of silver and gold nanoparticles using aqueous extract of seaweed, Turbinaria conoides, and their antimicrofouling activity. Sci World J. 2014 Oct;2014:1–10. 10.1155/2014/938272.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Suresh TC, Poonguzhali TV, Anuradha V, Ramesh B, Suresh G. Aqueous extract of Turbinaria conoides (J. Agardh) Kützing mediated fabrication of silver nanoparticles used against bacteria associated with diabetic foot ulcer. Mater Today: Proc. 2021 Jan;43:3038–43.10.1016/j.matpr.2021.01.376Search in Google Scholar

[35] Yilmaz MT, Yilmaz A, Akman PK, Bozkurt F, Dertli E, Basahel A, et al. Electrospraying method for fabrication of essential oil loaded-chitosan nanoparticle delivery systems characterized by molecular, thermal, morphological and antifungal properties. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2019 Mar;52:166–78.10.1016/j.ifset.2018.12.005Search in Google Scholar

[36] Prévot G, Mornet S, Lorenzato C, Kauss T, Adumeau L, Gaubert A, et al. Data on iron oxide core oil-in-water nanoemulsions for atherosclerosis imaging. Data brief. 2017 Dec;15:876–81.10.1016/j.dib.2017.10.059Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Frache A, Cadoni M, Bisio C, Marchese L, Mascarenhas AJ, Pastore HO. NO and CO adsorption on over-exchanged Cu-MCM-22: A FTIR study. Langmuir. 2002 Sep;18(18):6875–80.10.1021/la0257081Search in Google Scholar

[38] Yeoh SC, Loh PL, Murugaiyah V, Goh CF. Development and characterisation of a topical methyl salicylate patch: Effect of solvents on adhesion and skin permeation. Pharmaceutics. 2022 Nov;14(11):2491.10.3390/pharmaceutics14112491Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Oliyaei N, Moosavi-Nasab M, Tanideh N. Preparation of fucoxanthin nanoemulsion stabilized by natural emulsifiers: Fucoidan, sodium caseinate, and gum arabic. Molecules. 2022 Oct;27(19):6713.10.3390/molecules27196713Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Yilmaz A, Meral R, Kabli M, Ermis E, Akman PK, Dertli E, et al. Fabrication and characterization of bioactive nanoemulsion-based delivery systems. Emerg Mater Res. 2021 Jul;10(3):265–71.10.1680/jemmr.20.00280Search in Google Scholar

[41] Pezolet M, Pellerin C, Prud’homme RE, Buffeteau T. Study of polymer orientation and relaxation by polarization modulation and 2D-FTIR spectroscopy. Vib Spectrosc. 1998 Dec;18(2):103–10.10.1016/S0924-2031(98)00054-XSearch in Google Scholar

[42] Almasi H, Azizi S, Amjadi S. Development and characterization of pectin films activated by nanoemulsion and Pickering emulsion stabilized marjoram (Origanum majorana L.) essential oil. Food Hydrocoll. 2020 Feb;99:105338.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.105338Search in Google Scholar

[43] Kiani A, Fathi M, Ghasemi SM. Production of novel vitamin D3 loaded lipid nanocapsules for milk fortification. Int J Food Prop. 2017 Nov;20(11):2466–76.10.1080/10942912.2016.1240690Search in Google Scholar

[44] Somvanshi SB, Kumar RV, Kounsalye JS, Saraf TS, Jadhav KM. Investigations of structural, magnetic and induction heating properties of surface functionalized zinc ferrite nanoparticles for hyperthermia applications. In AIP conference proceedings 2019 Jul 11. Vol. 2115, No. 1, AIP Publishing. 10.1063/1.5113361 Search in Google Scholar

[45] Ahmed HA, Salama Z, Nassrallah A. S-limonene loaded gum Arabic nanoparticles displayed anti-herpes viruses (HSV-1 & HSV-2) and heal wounds properties. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-3627388/v1.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Singh A, Das S, Chaudhari AK, Soni M, Yadav A, Dwivedy AK, et al. Laurus nobilis essential oil nanoemulsion-infused chitosan: a safe and effective antifungal agent for masticatory preservation. Plant Nano. Biology. 2023 Aug;5:100043.10.1016/j.plana.2023.100043Search in Google Scholar

[47] Ghosh V, Saranya S, Mukherjee A, Chandrasekaran N. Cinnamon oil nanoemulsion formulation by ultrasonic emulsification: Investigation of its bactericidal activity. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2013 Jan;13(1):114–22.10.1166/jnn.2013.6701Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Kertmen A, Torruella P, Coy E, Yate L, Nowaczyk G, Gapiński J, et al. Acetate-induced disassembly of spherical iron oxide nanoparticle clusters into monodispersed core–shell structures upon nanoemulsion fusion. Langmuir. 2017 Oct;33(39):10351–65.10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b02743Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Nasiri F, Faghfouri L, Hamidi M. Preparation, optimization, and in-vitro characterization of α-tocopherol-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs). Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2020 Jan;46(1):159–71.10.1080/03639045.2019.1711388Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Rey C, Shimizu M, Collins B, Glimcher MJ. Resolution-enhanced fourier transform infrared spectroscopy study of the environment of phosphate ions in the early deposits of a solid phase of calcium-phosphate in bone and enamel, and their evolution with age. I: Investigations in the v 4 PO 4 domain. Calcif tissue Int. 1990 Jun;46:384–94.10.1007/BF02554969Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Zhou WY, Wang M, Cheung WL, Guo BC, Jia DM. Synthesis of carbonated hydroxyapatite nanospheres through nanoemulsion. J Mater Sci: Mater Med. 2008 Jan;19:103–10.10.1007/s10856-007-3156-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Ahmad J, Mir SR, Kohli K, Chuttani K, Mishra AK, Panda AK, et al. Solid-nanoemulsion preconcentrate for oral delivery of paclitaxel: formulation design, biodistribution, and γ scintigraphy imaging. BioMed Res Int. 2014 Jul;2014. 10.1155/2014/984756.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[53] Soltani S, Zakeri-Milani P, Barzegar-Jalali M, Jelvehgari M. Design of eudragit RL nanoparticles by nanoemulsion method as carriers for ophthalmic drug delivery of ketotifen fumarate. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2016 May;19(5):550.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Bhagat C, Singh SK, Verma PR, Singh N, Verma S, Ahsan MN. Crystalline and amorphous carvedilol-loaded nanoemulsions: formulation optimisation using response surface methodology. J Exp Nanosci. 2013 Oct;8(7–8):971–92.10.1080/17458080.2011.630037Search in Google Scholar

[55] Asasutjarit R, Sooksai N, Fristiohady A, Lairungruang K, Ng SF, Fuongfuchat A. Optimization of production parameters for andrographolide-loaded nanoemulsion preparation by microfluidization and evaluations of its bioactivities in skin cancer cells and uvb radiation-exposed skin. Pharmaceutics. 2021 Aug;13(8):1290.10.3390/pharmaceutics13081290Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[56] Nasr M. Development of an optimized hyaluronic acid-based lipidic nanoemulsion co-encapsulating two polyphenols for nose to brain delivery. Drug Deliv. 2016 May;23(4):1444–52.10.3109/10717544.2015.1092619Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] Guerra-Rosas MI, Morales-Castro J, Ochoa-Martínez LA, Salvia-Trujillo L, Martín-Belloso O. Long-term stability of food-grade nanoemulsions from high methoxyl pectin containing essential oils. Food Hydrocoll. 2016 Jan;52:438–46.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2015.07.017Search in Google Scholar

[58] Sahafi SM, Goli SA, Kadivar M, Varshosaz J, Shirvani A. Pomegranate seed oil nanoemulsion enriched by α-tocopherol; the effect of environmental stresses and long-term storage on its physicochemical properties and oxidation stability. Food Chem. 2021 May;345:128759.10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128759Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] Kang Z, Chen S, Zhou Y, Ullah S, Liang H. Rational construction of citrus essential oil nanoemulsion with robust stability and high antimicrobial activity based on combination of emulsifiers. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2022 Aug;80:103110.10.1016/j.ifset.2022.103110Search in Google Scholar

[60] Hu D, Ogawa K, Kajiyama M, Enomae T. Characterization of self-assembled silver nanoparticle ink based on nanoemulsion method. R Soc Open Sci. 2020 May;7(5):200296.10.1098/rsos.200296Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[61] Van Dat D, Van Cuong N, Le PH, Anh TT, Viet PT, Huong NT. Orange peel essential oil nanoemulsions supported by nanosilver for antibacterial application. Indonesian J Chem. 2020;20(2):430–9.10.22146/ijc.46042Search in Google Scholar

[62] Moghtader F, Salouti M, Türk M, Pişkin E. Nanoemulsions and nonwoven fabrics carrying AgNPs: Antibacterial but may be cytotoxic. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2014 Dec;42(6):392–9.10.3109/21691401.2013.834908Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[63] Majeed Khan MA, Kumar S, Ahamed M, Alrokayan SA, AlSalhi MS. Structural and thermal studies of silver nanoparticles and electrical transport study of their thin films. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2011 Dec;6:1–8.10.1186/1556-276X-6-434Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[64] Fayaz M, Tiwary CS, Kalaichelvan PT, Venkatesan R. Blue orange light emission from biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride. Colloids Surf B: Biointerfaces. 2010 Jan;75(1):175–8.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.08.028Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] Saxon DJ, Luke AM, Sajjad H, Tolman WB, Reineke TM. Next-generation polymers: Isosorbide as a renewable alternative. Prog Polym Sci. 2020 Feb;101:101196.10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2019.101196Search in Google Scholar

[66] Edwards CG, Beelman RB, Bartley CE, McConnell AL. Production of decanoic acid and other volatile compounds and the growth of yeast and malolactic bacteria during vinification. Am J Enol Viticulture. 1990 Jan;41(1):48–56.10.5344/ajev.1990.41.1.48Search in Google Scholar

[67] Sarova D, Kapoor A, Narang R, Judge V, Narasimhan B. Dodecanoic acid derivatives: synthesis, antimicrobial evaluation and development of one-target and multi-target QSAR models. Med Chem Res. 2011 Jul;20:769–81.10.1007/s00044-010-9383-5Search in Google Scholar

[68] Astiti NP, Ramona Y. GC-MS analysis of active and applicable compounds in methanol extract of sweet star fruit (Averrhoa carambola L.) leaves. HAYATI J Biosci. 2021 Jan;28(1):12.10.4308/hjb.28.1.12Search in Google Scholar

[69] Sivakumar R, Jebanesan A, Govindarajan M, Rajasekar P. Larvicidal and repellent activity of tetradecanoic acid against Aedes aegypti (Linn.) and Culex quinquefasciatus (Say.)(Diptera: Culicidae). Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2011 Sep;4(9):706–10.10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60178-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[70] Becker LC, Bergfeld WF, Belsito DV, Hill RA, Klaassen CD, Marks JG, et al. Final report of the amended safety assessment of myristic acid and its salts and esters as used in cosmetics. Int J Toxicol. 2010 May;29(4_suppl):162S–86S.10.1177/1091581810374127Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[71] Astudillo AM, Meana C, Bermúdez MA, Pérez-Encabo A, Balboa MA, Balsinde J. Release of anti-inflammatory palmitoleic acid and its positional isomers by mouse peritoneal macrophages. Biomedicines. 2020 Nov;8(11):480.10.3390/biomedicines8110480Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[72] Mayser P. Medium chain fatty acid ethyl esters–activation of antimicrobial effects by Malassezia enzymes. Mycoses. 2015 Apr;58(4):215–9.10.1111/myc.12300Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[73] Speert DP, Wannamaker LW, Gray ED, Clawson CC. Bactericidal effect of oleic acid on group A streptococci: Mechanism of action. Infect Immun. 1979 Dec;26(3):1202–10.10.1128/iai.26.3.1202-1210.1979Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[74] Khan AA, Alanazi AM, Jabeen M, Chauhan A, Abdelhameed AS. Design, synthesis and in vitro anticancer evaluation of a stearic acid-based ester conjugate. Anticancer Res. 2013 Jun;33(6):2517–24.Search in Google Scholar

[75] Balasubramanian A, Ganesan R, Mohanta YK, Arokiaraj J, Saravanan M. Characterization of bioactive fatty acid metabolites produced by the halophilic Idiomarina sp. OM679414. 1 for their antimicrobial and anticancer activity. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2023 Aug;1:1–10. 10.1007/s13399-023-04687-8.Search in Google Scholar

[76] El-Abd NM, Hamouda RA, Al-Shaikh TM, Abdel-Hamid MS. Influence of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles using red alga Corallina elongata on broiler chicks’ performance. Green Process Synth. 2022 Mar;11(1):238–53.10.1515/gps-2022-0025Search in Google Scholar

[77] Teleb WK, Tantawy MA, Osman NA, Abdel-Rahman MA, Hussein AA. Structural and cytotoxic characterization of the marine red algae Sarconema filiforme and Laurencia obtusa. Egypt J Aquat Biol Fish. 2022 Jul;26(4):549–73.10.21608/ejabf.2022.252760Search in Google Scholar

[78] Gomes LC, Merino FJ, Pacheco SD, Cansian FC, de Oliveira LF, Dias JD, et al. Activation of human neutrophils by dotriacontane from Tynanthus micranthus Corr. Méllo (Bignoniaceae) for the production of superoxide anions. Ciência e Nat. 2020;42:e4.10.5902/2179460X41253Search in Google Scholar

[79] Stenz L, François P, Fischer A, Huyghe A, Tangomo M, Hernandez D, et al. Impact of oleic acid (cis-9-octadecenoic acid) on bacterial viability and biofilm production in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008 Oct;287(2):149–55.10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01316.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[80] Zeid IM, Al Thobaitil SA, El Hag GA, Alghamdi SA, Umar A, Ahmed Hamdi O. Phytochemical and GC-MS analysis of bioactive compounds from Balanites aegyptiaca. Acta Sci Pharm Sci. 2019;3:129–34.10.31080/ASPS.2019.03.0352Search in Google Scholar

[81] Shawer EE, Sabae SZ, El-Gamal AD, Elsaied HE. Characterization of bioactive compounds with antioxidant activity and antimicrobial activity from freshwater cyanobacteria. Egypt J Chem. 2022 Sep;65(9):723–35.Search in Google Scholar

[82] Al-Rajhi AM, Ghany TA. Nanoemulsions of some edible oils and their antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-hemolytic activities. BioResources. 2023 Feb;18(1):1465.10.15376/biores.18.1.1465-1481Search in Google Scholar

[83] Mehmood T. Optimization of the canola oil based vitamin E nanoemulsions stabilized by food grade mixed surfactants using response surface methodology. Food Chem. 2015 Sep;183:1–7.10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.03.021Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[84] Bharmoria P, Bisht M, Gomes MC, Martins M, Neves MC, Mano JF, et al. Protein-olive oil-in-water nanoemulsions as encapsulation materials for curcumin acting as anticancer agent towards MDA-MB-231 cells. Sci Rep. 2021 Apr;11(1):9099.10.1038/s41598-021-88482-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[85] Bello BA, Khan SA, Khan JA, Syed FQ, Anwar Y, Khan SB. Antiproliferation and antibacterial effect of biosynthesized AgNps from leaves extract of Guiera senegalensis and its catalytic reduction on some persistent organic pollutants. J Photochem Photobiol B: Biol. 2017 Oct;175:99–108.10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2017.07.031Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[86] Akter M, Atique Ullah AK, Banik S, Sikder MT, Hosokawa T, Saito T, et al. Green synthesized silver nanoparticles-mediated cytotoxic effect in colorectal cancer cells: NF-κB signal induced apoptosis through autophagy. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2021 Sep;199:3272–86.10.1007/s12011-020-02463-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[87] Majeed H, Antoniou J, Fang Z. Apoptotic effects of eugenol-loaded nanoemulsions in human colon and liver cancer cell lines. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014 Jan;15(21):9159–64.10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.21.9159Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[88] Tabassum H, Ahmad IZ. Evaluation of the anticancer activity of sprout extract-loaded nanoemulsion of N. sativa against hepatocellular carcinoma. J Microencapsul. 2018 Nov;35(7-8):643–56.10.1080/02652048.2019.1571641Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[89] Haro-González JN, Schlienger de Alba BN, Martínez-Velázquez M, Castillo-Herrera GA, Espinosa-Andrews H. Optimization of clove oil nanoemulsions: Evaluation of antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties. Colloids Interfaces. 2023 Oct;7(4):64.10.3390/colloids7040064Search in Google Scholar

[90] Krishnamoorthy R, Athinarayanan J, Periasamy VS, Adisa AR, Al-Shuniaber MA, Gassem MA, et al. Antimicrobial activity of nanoemulsion on drug-resistant bacterial pathogens. Microb Pathog. 2018 Jul;120:85–96.10.1016/j.micpath.2018.04.035Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[91] Başpinar Y, Kotmakçi M, Öztürk İ. Antimicrobial activity of phytosphingosine nanoemulsions against bacteria and yeasts. Celal Bayar Univ J Sci. 2018 Jun;14(2):223–8.10.18466/cbayarfbe.403152Search in Google Scholar

[92] Rosato A, Barbarossa A, Mustafa AM, Bonacucina G, Perinelli DR, Petrelli R, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of the antibacterial and antifungal activities of Carlina acaulis L. essential oil and its nanoemulsion. Antibiotics. 2021 Nov;10(12):1451. 10.3390/antibiotics10121451 Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[93] Ozogul Y, Boğa EK, Akyol I, Durmus M, Ucar Y, Regenstein JM, et al. Antimicrobial activity of thyme essential oil nanoemulsions on spoilage bacteria of fish and food-borne pathogens. Food Biosci. 2020 Aug;36:100635.10.1016/j.fbio.2020.100635Search in Google Scholar

[94] Alkhatib MH, Aly MM, Bagabas S. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of action of lipid nanoemulsions against Staphylococcus aureus. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2013 Nov;7:259–67.Search in Google Scholar

[95] Chouhan S, Sharma K, Guleria S. Antimicrobial activity of some essential oils—present status and future perspectives. Medicines. 2017 Aug;4(3):58.10.3390/medicines4030058Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[96] Khatri S, Lohani P, Gandhi S. Nanoemulsions in cancer therapy. Indo Glob J Pharm Sci. 2013;3(2):124–33.10.35652/IGJPS.2013.14Search in Google Scholar

[97] Basavegowda N, Patra JK, Baek KH. Essential oils and mono/bi/tri-metallic nanocomposites as alternative sources of antimicrobial agents to combat multidrug-resistant pathogenic microorganisms: An overview. Molecules. 2020 Feb;25(5):1058.10.3390/molecules25051058Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[98] Hort MA, Alves BD, Ramires Junior OV, Falkembach MC, Araújo GD, Fernandes CL, et al. In vivo toxicity evaluation of nanoemulsions for drug delivery. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2021 Nov;44(6):585–94.10.1080/01480545.2019.1659806Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[99] McClements DJ. Advances in edible nanoemulsions: Digestion, bioavailability, and potential toxicity. Prog Lipid Res. 2021 Jan;81:101081.10.1016/j.plipres.2020.101081Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[100] Fofaria NM, Qhattal HS, Liu X, Srivastava SK. Nanoemulsion formulations for anticancer agent piplartine—Characterization, toxicological, pharmacokinetics and efficacy studies. Int J Pharm. 2016 Feb;498(1–2):12–22.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.11.045Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy