Abstract

The fabrication of a Bi(iii) oxide-Bi(iii) oxychloride/poly-m-methyl aniline (Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA) nanocomposite thin-film optoelectronic device capable of light-sensing across a broad spectrum, spanning both visible and ultraviolet wavelengths, has been accomplished. The synthesis of the composite has been achieved using a one-pot technique involving the direct oxidation of m-methyl aniline with ammonium persulfate ((NH4)2S2O8) in the presence of bismuth nitrate pentahydrate (Bi(NO3)35H2O). X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis confirms the composite’s high crystallinity and compact size of 41 nm, indicative of excellent optical properties and a narrow bandgap of 2.35 eV. The optical analysis of the synthesized core–shell composite is performed using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). FTIR, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, and XRD analysis characterize the fabricated composite’s crystalline structure. The composite has been tested electrically using the CHI608E device, demonstrating its potential for efficient light absorption and photon trapping, making it a promising candidate for advanced light sensing applications.

1 Introduction

New composites combining metal oxide materials and polymers have garnered significant interest among researchers in recent decades [1,2,3]. This hybrid material exhibits distinguishable potential in topological insulators, photocatalysts, and sensor applications. The versatility of these composites lies in their ability to originate several new descendants, like semimetals and semiconductors, depending on the specific combination used [4,5]. Bismuth (Bi) is a noteworthy element, showing exceptional results, particularly when combined with oxide and oxychloride semiconductors. As a semimetal, bismuth is characterized by an anisotropic Fermi surface, a small effective mass and carrier density, and a long carrier mean free path. These properties make it highly suitable for a range of advanced applications. Furthermore, bismuth oxide (Bi2O3) has emerged as a promising candidate in sensors, photocatalysis, and optoelectronic devices due to its unique properties [6,7].

Conjugated polymer semiconductors, particularly polyaniline derivatives, have recently experienced notable advancements, driven by their affordability, accessibility, and remarkable potential to host diverse nanomaterials [8,9]. These polymers serve as effective matrices for incorporating various nanoparticles, which substantially improves their electrical conductivity and optical characteristics [3,10]. When polymers are combined with bismuth-based composites, their material properties are enhanced even further. This synergy between polymers and bismuth composites opens up new possibilities for advanced applications, positioning these materials as a promising choice in fields requiring enhanced conductivity and stability.

Two approaches are utilized to enhance the optical properties of conjugated polymers. First, the morphological behavior is addressed, where nanoscale polymers or porous materials exhibit excellent electrical and optical properties for light absorption [11]. Second, these polymer materials are combined with other substances with broad optical absorbance, thereby boosting the overall absorbance. Oxide and oxychloride materials, in this regard, are critical components for optical absorbance due to their small band gap [12,13].

Previous studies have focused on fabricating optoelectronic devices for detecting light in the ultraviolet (UV) region, utilizing various materials. These include polymers or polymer composites such as P3HT, PBBTPD: Tri-PC61BM, and TiO2-PANI [14,15,16], fullerene materials like PC71BM [17], perovskites such as ITO/CsPbBr3/Ag [18], and oxide materials, including CuO nanowires and Carbon-Co3O4 [19,20]. Nonetheless, these studies are limited to light sensing in the UV region or the initial part of the visible (Vis) spectrum, with restricted R values ranging from approximately 0.005 to 0.001 mA·W−1.

Herein, the one-step fabrication of a Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA nanocomposite thin-film optoelectronic device capable of sensing light across a broad spectrum, spanning both Vis and UV wavelengths, has been accomplished. A comprehensive analysis of this nanocomposite, covering morphology, optical absorption, chemical composition, electrical characteristics, and crystalline size, has been conducted. Electrical testing involves assessing the device’s sensitivity by measuring J ph and J o values. J ph is evaluated under various optical filters and wavelengths by carefully controlling photon energy.

Integrating the bismuth oxide and oxychloride with PmMA matrices offers a multifaceted approach to material design, leveraging the strengths of both components. Bismuth’s semiconductor properties, combined with the adaptability and multifunctionality of PmMA, create composites with enhanced and tunable properties. This composite is particularly valuable in developing advanced sensors requiring high photon sensitivity under various energies. The ability of polymers to incorporate a wide range of nanomaterials further expands the potential applications of these composites, making them suitable for use in various optoelectronic and photocatalytic devices.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

m-Methyl aniline (99.9%) and Bismuth nitrate pentahydrate (Bi(NO3)3·5H2O) (99.9%) have been produced by Merck Germany. Sigma Aldrich, USA, supplies dimethylsulfoxide (99.9%). Ammonium persulfate ((NH4)2S2O8, 99.8%) is provided by Pio-Chem, Egypt.

2.2 Synthesizing of Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA core–shell nanocomposite

The synthesis of the Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA core–shell nanocomposite is accomplished using a one-pot technique involving the direct oxidation of m-methyl aniline with ammonium persulfate ((NH4)2S2O8) in the presence of bismuth nitrate pentahydrate (Bi(NO3)3·5H2O). To ensure complete dissolution, the monomer (m-methyl aniline) is initially dissolved in distilled water with 0.8 M hydrochloric acid (HCl) at room temperature. Once the monomer is fully dissolved, 0.06 M Bi(NO3)3·5H2O is added to the solution. The presence of HCl aids in the dispersion of Bi3+ ions throughout the monomer solution.

Separately, (NH4)2S2O8 is dissolved in distilled water and added to the monomer solution at a molar ratio of 1:3 (monomer to oxidant). A clean glass substrate is then introduced into the reaction medium. This process continues for a full day, resulting in the formation of a highly uniform thin film of the Bi₂O₃-BiOCl/PmMA core–shell nanocomposite on a glass substrate, created at room temperature. Polymerization occurs after the oxidant’s addition, producing the desired core–shell structure. The film formed on the glass substrate undergoes further treatment to prepare it for additional characterization processes, ensuring its suitability for various applications.

This efficient and scalable synthesis method produces a uniform nanocomposite film with promising properties for potential use in optoelectronics, sensors, and other advanced materials applications. The core–shell structure enhances the material’s properties by combining the unique characteristics of Bi2O3 and BiOCl with the conductive polymer PmMA, leading to improved performance in desired applications.

2.3 The electrical testing of Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA core–shell nanocomposite thin film optoelectronic device

The fabricated Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA core–shell nanocomposite thin film was tested electrically using the CHI608E device through linear sweep voltammetry and chronoamperometry techniques. These electrical tests were designed to estimate the device’s efficiency as an optoelectronic material by measuring the current density (J ph) generated by the hot electrons produced under illumination.

A metal halide lamp was used to conduct these tests as a white light source. During illumination, the incident photons were trapped within the pores of the optoelectronic device, leading to the generation of hot electrons. The wavelength and energy of the incident photons influence the intensity of these hot electrons. Optical filters were employed to control the frequency and energy of these photons, ensuring precise measurement of the J ph values. Figure 1 represents the electrical connections for testing this fabricated Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA optoelectronic device.

The schematic diagram of the electrical testing of the fabricated Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA thin film optoelectronic device.

The efficiency of the optoelectronic device was evaluated by calculating the photoresponsivity (R) and detectivity (D) using Eqs. 1 and 2 [21], respectively. These equations depend on the electron charge (e) and the surface area of the optoelectronic device (A). Photoresponsivity (R) measures the electrical output per optical input unit, reflecting how effectively the device converts light into an electrical signal. Detectivity (D) measures the device’s ability to detect weak optical signals, indicating sensitivity. The produced hot electrons were measured using the CHI608E device, the specified testing methods were used, and the efficiency metrics were calculated. This comprehensive electrical testing demonstrated the potential of the Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA core–shell nanocomposite thin film as an efficient optoelectronic device capable of trapping and converting photons into electrical signals with high sensitivity and responsiveness. The results highlighted the advanced capabilities of this nanocomposite, making it a promising candidate for various optoelectronic applications.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Analyses

Figure 2(a) presents the Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectrum of the Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA composite, illustrating the chemical composition through the identified vibration bonds. The functional groups of the PmMA polymer, such as C–H, C–N, and N–H, are distinctly detected at 1,147, 1,379, and 3,392 cm⁻¹, respectively. A redshift in these peaks is observed upon incorporating the Bi2O3–BiOCl into the polymer matrix. This shift indicates the interaction between the polymer and the inserted materials, demonstrating successful composite formation. For detailed information on the specific positions of the bonds in the composite, refer to Table 1.

(a) The function group FTIR and (b) crystalline feature XRD pattern analyses for the synthesized Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA nanocomposite.

The bond positions before/after the composite formation with PmMA for the FTIR analyses

| Bonds positions | Functional groups | |

|---|---|---|

| PmMA | Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA | |

| 586–1,056 | 594–1,057 | C–H bending |

| 1,147 | 1,201 | −CH stretching [22] |

| 1,379 | 1,401 | C–N |

| 1,640 | 1,633 | C–C and C═C [23] |

| 3,392 | 3,425 | N–H |

The crystalline structure, growth direction, and chemical composition of the synthesized Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA composite are analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns, as shown in Figure 2(b). This analysis reveals a significant improvement in the composite’s crystalline behavior compared to the pristine PmMA polymer material. The characteristic peaks for each inorganic component, Bi2O3, and BiOCl, are identified.

For Bi2O3, the peaks are located at 2θ values of 18.5°, 23.2°, 25.6°, 26.9°, 27.1°, 28.1°, 32.5°, 34.1°, 42.0°, 52.4°, 54.7°, 58.1°, 59.3°, and 60.4°, corresponding to the Miller indices (111), (120), (210), (012), (201), (002), (220), (212), (122), (321), (203), (421), (402), and (422), respectively, JCBDS standard 76-1730 [6,24].

The BiOCl component is identified by peaks at 2θ values of 15.2°, 22.4°, 24.7°, 30.8°, 35.2°, 38.9°, 46.4°, and 48.3°, with corresponding Miller indices (020), (002), (101), (110), (003), (112), (200), and (113), as per JCPDS (06-0249) [25].

The composite’s crystalline size is estimated using the Scherrer equation (Eq. 3) [26]. Based on the sharp peak at 2θ = 15.2°, the calculated crystalline size is approximately 41 nm. This estimation uses the peak’s full width at half maximum.

In contrast, the pristine PmMA polymer does not allow an accurate crystalline size estimation using the Scherrer equation due to only a semi-sharp peak at 2θ = 14.5°. However, after forming the composite, the crystalline behavior significantly improves, evidenced by three sharp peaks at 13.6°, 14.2°, and 16.5°. The enhanced crystalline properties of the synthesized Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA composite suggest its potential for efficient light absorbance and photon trapping, making it a promising material for optoelectronic applications. Combining crystalline Bi2O3 and BiOCl within the PmMA matrix contributes to these improved optical properties, highlighting the composite’s potential in advanced material applications.

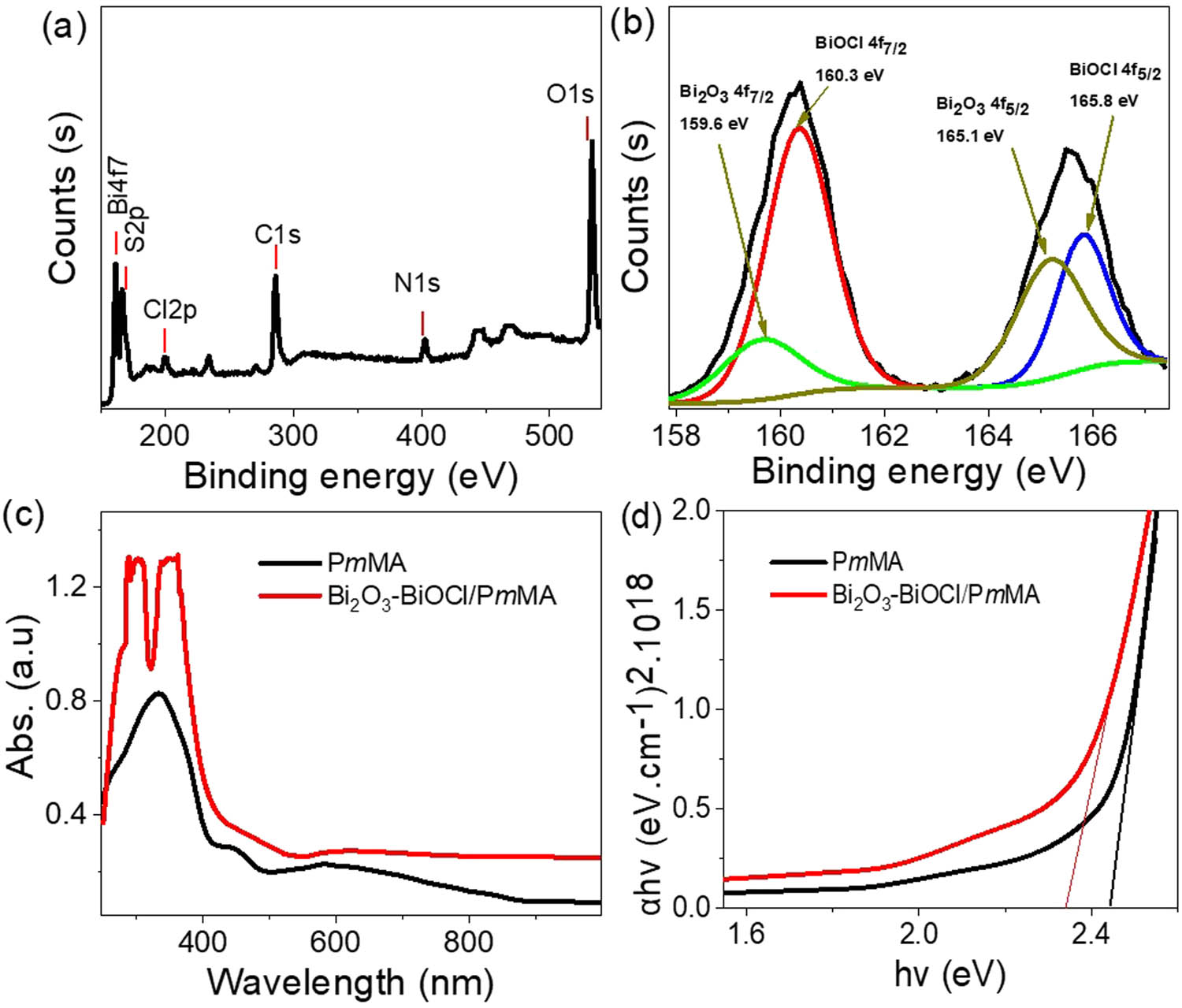

To further analyze the chemical composition of the Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA nanocomposite, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was conducted, as illustrated in Figure 3(a). This analysis provides detailed information about the elements present in the composite and their oxidation states. The constituents of the PmMA polymer are confirmed by detecting carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) elements. These elements are identified by their 1s orbitals, with binding energies at 286 eV for carbon and 400 eV for nitrogen. Chlorine (Cl), which is involved in forming the composite, particularly in BiOCl, is detected at a binding energy of 200 eV. Oxygen (O), a component of both Bi2O3 and BiOCl, is observed through the 1s orbital at a binding energy of 532 eV.

The XPS chemical analyses (a) survey Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA nanocomposite and (b) Bi element. The optical analyses for the synthesized Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA nanocomposite: (c) absorbance and (d) bandgap.

Bismuth (Bi), present as Bi3+ ions in both Bi2O3 and BiOCl, is characterized by doublet peaks in the XPS spectrum, indicating the formation of these oxides. These doublet peaks correspond to the Bi4f7/2 and Bi4f5/2 orbitals. For Bi2O3, the Bi4f7/2 and Bi4f5/2 peaks are detected at 159.6 and 165.1 eV, respectively. In the case of BiOCl, these peaks shift slightly to 160.3 and 165.8 eV, respectively [27,28], reflecting the distinct chemical environments in the two oxides. The comprehensive XPS analysis thus confirms the presence and oxidation states of the elements in the Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA nanocomposite, providing a clear understanding of its chemical composition and supporting the successful synthesis of the composite material. The elemental composition of the promising Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA nanocomposite was estimated using XPS analysis. The results indicate the following elemental ratios: bismuth (Bi) at 2.58%, chlorine (Cl) at 7.39%, oxygen (O) at 33.2%, carbon (C) at 48.55%, and nitrogen (N) at 7.37%. Additionally, a small proportion of sulfur (S), constituting 0.91%, is detected, which originates from the oxidant ammonium persulfate ((NH4)2S2O8) used during the synthesis process.

Figure 3(c) shows the optical absorbance of the synthesized Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA nanocomposite compared to pristine PmMA. This analysis focuses on the absorbance related to the π–π* electron transitions in both the UV and Vis regions. The composite exhibits a double peak, attributed to the synergistic photon absorbance from the inorganic Bi2O3–BiOCl and the organic PmMA components. Additionally, the increased absorbance intensity is linked to the efficient trapping of photons within the crystalline structure of the materials.

These enhancements in optical absorbance correspond to changes in the optical bandgap (Figure 3(d)). The composite’s bandgap is 2.35 eV, compared to 2.42 eV for pristine PmMA. This estimation is based on the Tauc equation (Eqs. 4 and 5) [29], which relies on the absorbance (A) and the absorbance coefficient (α) parameters. This bandgap reduction highlights the composite’s improved photon absorption and energy conversion efficiency.

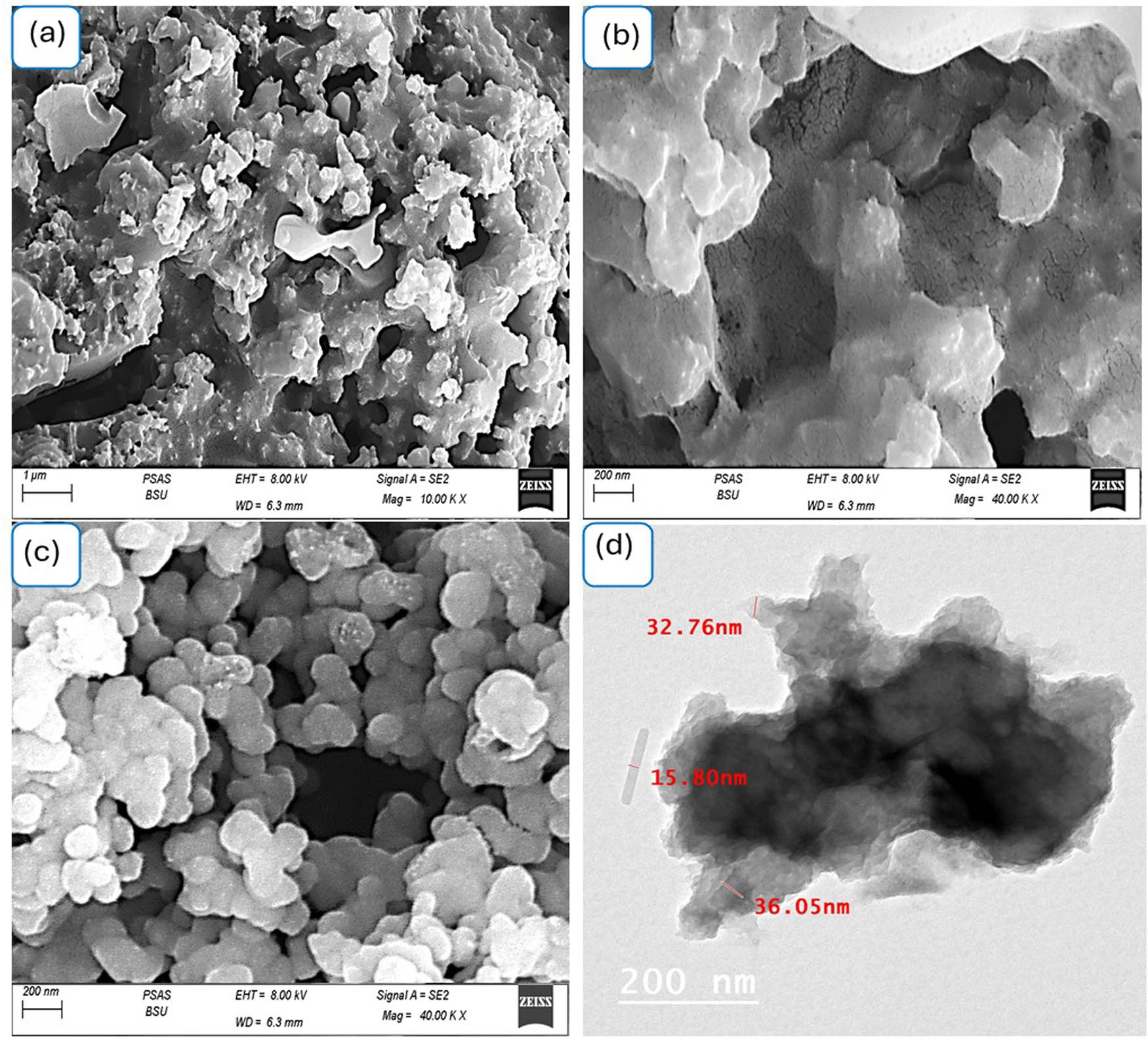

The SEM and transmission electron spectroscopy (TEM) images of the Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA nanocomposite are shown in Figure 4. The SEM images are represented in different magnifications, 10 and 40k. They illustrated a rough morphology of large, agglomerated structures separated with wide porous ranging between 100 and 200 nm (Figure 4(a) and (b)). The obtained nanocomposite particle structure forms a rough, porous nanocomposite thin film. The located pores are crucial to facilitate depolarization, enhance photon diffusion paths, foster the interfacial reaction area [30,31], and enhance the performance of optoelectronic devices. Furthermore, the TEM images in Figure 4(d) confirm the incorporation of the Bi2O3–BiOCl nanomaterial into the PmMA matrix. Dark areas, varying in size from 20 to 100 nm, are Vis within the PmMA polymer, indicating the successful integration of the inorganic components. The nonporous structure of the Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA nanocomposite functions effectively as a trap for incident photons. Once a photon enters the structure, it can collide with the surface multiple times, which increases the likelihood of energy transfer. This interaction allows the photon energy to be transferred to adjacent active sites within the composite. As a result, hot electrons are generated, which contribute to the formation of substantial electron clouds. These clouds are essential for producing a significant J ph value, enhancing the overall performance of the nanocomposite in optoelectronic applications [32].

The topographical and morphological (a and b) SEM at various magnifications and (c) TEM for the synthesized Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA nanocomposite, while (d) SEM for the pristine PmMA polymer.

The morphology of the PmMA polymer itself is characterized by spherical shapes, as shown in Figure 4(c). These spherical features are the foundational layer for the additional morphological layer formed during the composite synthesis. This structure supports the formation of a highly porous composite with improved properties for various applications, especially in optoelectronics.

3.2 Electrical testing of the fabricated Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA thin film optoelectronic device

The performance of the fabricated Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA thin film optoelectronic device in light sensing is influenced by its ability to capture and trap light. The incident photons play a crucial role as they generate hot electrons emitted through the active sites of the Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA composite. The device benefits from the composite’s small particles and porous nature and its small bandgap of 2.35 eV. Additionally, the synergistic effect of the composite materials – Bi2O3, BiOCl, and PmMA – makes this optoelectronic device highly promising for light sensing and trapping applications.

For the electrical testing of this device, two small silver (Ag) spots are coated on each side of the Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA thin film. The total area exposed to light illumination is 1.0 cm². These sides are then connected to an electrochemical workstation, specifically the CHI608E device, to measure the device’s performance. Evaluating the optoelectronic device’s behavior involves estimating the photocurrent density (J ph) and the dark current density (J o). The difference between these two values is used to determine the R and D of the device. Integrating Bi2O3, BiOCl, and PmMA in the thin film composite, combined with its structural and electronic properties, enables adequate light capturing and trapping. This makes the Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA thin film optoelectronic device a promising candidate for advanced light sensing applications.

The sensitivity behavior of the fabricated Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA thin film optoelectronic device is assessed by comparing the J ph of 0.019 mA·cm−2 to the J o of 0.005 mA·cm−2, as shown in Figure 5(a). The substantial difference between these values indicates the device’s high sensitivity, activated by incident photons. This activation is directly linked to the device’s sensitivity to these photons. Upon interaction, the photons generate hot electrons within the optoelectronic crystal material. These hot electrons then move to and accumulate on the conduction bands of the composite materials, particularly on the surface of BiOCl.

The electrical testing of the fabricated Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA thin film optoelectronic device: (a) under light illumination and (b) several repeating light illuminations.

Once generated, the hot electrons flow through the external circuit, measured as the J ph. Therefore, the J ph value represents the quantity of hot electrons produced under light illumination, directly correlating to the sensitivity of the Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA thin film optoelectronic device. The efficient generation and movement of hot electrons highlight the device’s capability to capture and respond to light effectively, making it a promising candidate for light-sensing applications [33,34]. The significant increase in J ph compared to J o underscores the device’s responsiveness to photon incidence, reflecting its high sensitivity and potential for practical optoelectronic applications.

In addition to its exceptional sensitivity, this optoelectronic device exhibits outstanding reproducibility and stability, consistently yielding the same J ph value across various electrical measurements. This consistency underscores the device’s reliability and makes it highly suitable for industrial applications. The stability of the device is mainly due to its chemical composition, which includes oxide materials and a polymer. Both these components are known for their inherent strength. Additionally, the polymer’s anti-corrosion properties significantly enhance the device’s durability, enabling it to be used repeatedly without experiencing degradation. These attributes collectively position the Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA thin film optoelectronic device as a highly stable and dependable solution for light sensing in industrial settings.

The sensitivity of the promising Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA thin-film optoelectronic device is estimated by testing it under various photon frequencies. This estimation involves controlling the light energy incident on the device using optical filters that allow only specific wavelengths to pass. The wavelengths tested are 730, 540, 440, and 340 nm, corresponding to photon energies of 1.8, 2.3, 2.8, and 3.6 eV, respectively, based on the equation λ = hv.

When photons interact with the device, they impart kinetic energy to the electrons, which varies according to the energy of the incoming photons [21,35]. Higher-energy photons are more effective at moving electrons into the conduction band, creating sufficient electric field energy that allows electrons to travel through the Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA composite, which has a narrow bandgap of 2.35 eV. These energized electrons then pass through an external circuit, generating measurable, J ph values. Within this layered material structure, energy transfer is sequential, enabling electrons to travel through each layer until they reach the Bi2O3, followed by BiOCl, while holes move in the opposite direction until they reach PmMA. This polarization difference across the layers results in the generation of J ph.

However, this effective electron flow cannot be attained when using only the pure PmMA material. Its larger particle size and the accumulation of electrons in the valence energy levels prevent it from supporting an optimal electron flow.

Figure 6(a) and the evaluated J ph values at 2.0 V in Figure 6(b) show that the highest J ph value is observed at the shortest wavelength (highest energy photons). Specifically, at 340 nm, the J ph value is 0.016 mA·cm−2. As the wavelength increases to 440 nm, the J ph value decreases to 0.008 mA·cm−2 and decreases to 0.007 mA·cm−2 at 540 nm. These wavelengths correlate with photon energies close to the bandgap of 2.35 eV. When the photon energy decreases to 1.8 eV, the J ph value drops to 0.006 mA·cm−2, close to the dark current (J o) value of 0.005 mA·cm−2.

The electrical testing of the fabricated Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA thin film optoelectronic device: (a) under light illumination of various wavelengths and (b) estimated J ph value at 2.0 V.

This testing demonstrates that the fabricated Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA optoelectronic device can function effectively as a photon sensor in both the Vis and UV regions. This represents significant progress in optoelectronics, as previous studies have primarily focused on sensors for the UV region. Examples of such studies include PBBTPD: Tri-PC61BM, TiN/TiO2, ITO/CsPbBr3/Ag, polyaniline/MgZnO, PC71BM, and carbon-Co3O4 sensors [15,17,18,20,36,37].

The sensitivity of the fabricated Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA thin-film optoelectronic device is evaluated by calculating the R-value based on J ph and J o as shown in Figure 7(a). The optimal R-value obtained is 0.16 mA·W−1 at 340 nm. This value decreases to 0.09 mA·W−1 at 440 nm and 0.08 mA·W−1 at 540 nm. These values highlight the device’s ability to sense photons in Vis and UV regions, demonstrating its superior performance compared to other sensors reported in the literature.

The estimated sensitivity of the fabricated through the produced (a) R and (b) D values for Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA thin-film optoelectronic device.

Previous studies, such as those involving ITO/CsPbBr3/Ag, Ti3C2 MXenes, and ZnO/RGO, have reported R-values of approximately 0.01 mA·W−1 [18,38,39]. Unlike earlier technologies that were limited to UV detection, the Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA device offers enhanced sensitivity and effectiveness as a photon sensor across a broader spectrum, encompassing both Vis and UV regions. This unique contribution underscores the significant progress made in optoelectronics, setting it apart from previous literature. For a more detailed estimation of its superiority, refer to Table 2.

Compared to other literature, the fabricated Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA thin-film optoelectronic device is sensitive

| Photoelectrode | Wavelength (nm) | Potential (V) | R (mA·W−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBBTPD: Tri-PC61BM [15] | 350 | 5 | 10−4 |

| Ti3C2 MXenes [38] | 405 | 5 | 0.07 |

| TiO2–PANI [16] | 320 | 0 | 3 × 10−3 |

| PC71BM [17] | 300 | 2 | 0.005 |

| Graphene/GaN [40] | 365 | 7 | 3 × 10−3 |

| ITO/CsPbBr3:ZnO/Ag [18] | 405 | 0 | 0.01 |

| CuO nanowires [19] | 390 | 5 | — |

| Carbon–Co3O4 [20] | 350 | 2 | 0.01 |

| Se/TiO2 [41] | 450 | 1 | 5 × 10−3 |

| ZnO/Cu2O [42] | 350 | 2 | 4 × 10−3 |

| P3HT [14] | 325 | 1 | NA |

| ZnO–CuO [43] | 405 | 1 | 3 × 10−3 |

| GO/Cu2O [44] | 300 | 2 | 0.5 × 10−3 |

| CuO/Si Nanowire [45] | 405 | 0.2 | 3.8 × 10−3 |

| TiN/TiO2 [36] | 550 | 5 | — |

| PbI2-5% Ag [46] | 532 | 6 | NA |

| ZnO/RGO [39] | 350 | 5 | 1.3 × 10−3 |

| ZnO/RGO [39] | 350 | 5 | 1.3 × 10−3 |

| Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA (this work) | 340 | 2 | 0.16 |

The D value estimation for the fabricated Bi2O3–BiOCl/PmMA thin-film optoelectronic device shows a sequential decrease from the UV region (340 nm) to the Vis region (540 nm), ranging from 0.36 × 108 Jones to 0.18 × 108 Jones, respectively. This trend further highlights the device’s sensitivity across these optical regions, confirming its effectiveness as a promising sensor for UV and Vis light.

4 Possible applications of the new composite

The fabrication of a thin film optoelectronic device using a Bi₂O₃-BiOCl/polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) nanocomposite capable of light detection across a broad spectrum, encompassing both Vis and UV regions has been successfully achieved. This success was supported by comprehensive chemical, electrical, optical, and morphological analyses. XRD analysis confirmed the high crystallinity of the compound and its compact size of 41 nm, indicative of excellent optical properties and a narrow band gap of 2.35 eV.

The device’s photocurrent density (J ph) of 0.019 mA·cm−2 was compared with its dark current (J o) of 0.005 mA·cm−2 to assess sensitivity. Evaluations under monochromatic wavelengths showed optimal J ph values ranging from 0.016 to 0.007 mA·cm−2 between 340 and 540 nm. These J ph values directly influenced the device’s R and D values, which ranged from 0.16 mA·W−1 at 340 nm to 0.08 mA·W−1 at 540 nm, and from 0.36 × 10⁸ to 0.18 × 10⁸ Jones, respectively. These electrical measurements underscored the device’s sensitivity across the optical range of interest.

With attributes such as cost-effectiveness, stability, reproducibility, and scalability for mass production, this optoelectronic sensor holds significant promise for industrial and commercial applications. Its ability to effectively detect light across the Vis–UV regions positions it as a valuable tool in fields requiring precise optical sensing capabilities.

4.1 Applications

Optical devices: Enhanced transparency and refractive properties make it suitable for lenses, light guides, and other optical components.

Sensors: Improved electrical conductivity and mechanical strength are advantageous for developing various types of sensors.

Electronic displays: The combination of optical clarity, electrical properties, and durability makes these compounds ideal for electronic displays and screens.

4.2 Summary of benefits

Integrating bismuth oxide (Bi₂O₃) and bismuth oxychloride (BiOCl) with PMMA matrices can potentially offer several benefits. For instance, bismuth oxide is known for its high refractive index and excellent electrical conductivity, which can enhance the optical and electrical properties of the composite material. Oxychloride, on the other hand, could contribute to the material’s thermal stability and mechanical strength.

Here we summarize the benefits of the new composites:

4.2.1 Advancing optical properties

Improved transparency: Bismuth compounds have high refractive indices, improving the composite’s transparency and clarity.

Photocatalytic activity: Both Bi₂O₃ and BiOCl are known for their strong photocatalytic properties, which are useful in applications such as self-cleaning surfaces and water purification. The composite’s porous structure can also be used to make more efficient filters for water purification.

4.2.2 Medical applications

X-ray imaging: Bismuth oxide is highly radiopaque and Vis under X-ray imaging. Incorporating Bi₂O₃ into PMMA matrices improves the visibility of medical applications such as dental fillings and bone cement in diagnostic imaging.

Mechanical properties: Adding bismuth compounds has improved the mechanical strength and durability of the composites, making them more resistant to wear and tear. Bismuth oxide increases the hardness and rigidity of PMMA, making the composite suitable for more demanding structural applications.

Thermal stability: The new material can withstand higher temperatures without degrading, making it suitable for applications that require high-temperature resistance.

4.2.3 Antimicrobial properties

Biocidal activity: Bismuth compounds have antimicrobial properties, which are beneficial in medical and hygiene-related applications. Integrating these compounds into PMMA can help prevent bacterial growth and infection, making it suitable for various medical equipment.

4.2.4 Chemical stability

Resistance to degradation: Bismuth oxide and oxychloride enhance the chemical stability of PMMA composites, making them more resistant to degradation from environmental factors such as UV radiation, moisture, and chemicals.

4.2.5 Flame retardancy

Fire protection: Bismuth-based compounds can impart flame-retardant properties to PMMA composites, making them safer when fire resistance is crucial, such as in construction and electronics.

5 Conclusions

Integrating bismuth oxide and Bismuth oxychloride with PMMA matrices offers numerous potential benefits, including enhanced optical properties, radiopacity, improved mechanical and thermal stability, antimicrobial properties, chemical stability, and flame retardancy. These enhancements make the composite material suitable for advanced medical, industrial, environmental, and technological applications.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research and Libraries in Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University for funding this research work through the Research Group project, Grant No. (RG-1445-0010).

-

Funding information: This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research and Libraries in Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University for funding this research work through the Research Group project, Grant No. (RG-1445-0010).

-

Author contributions: Amira Ben Gouider Trabelsi, Fatemah H. Alkallas, and Fedor V. Kusmartsev: writing, revision, and project funding; Mohamed Rabia: experimental, writing, and analyses.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Alkallas FH, Elsayed AM, Trabelsi ABG, Rabia M. Basic and acidic electrolyte mediums impact on MnO2-Mn2O3/Poly-2-methylaniline hexagonal nanocomposite pseudo-supercapacitor. Phys Scr. 2024;99(6):065972.10.1088/1402-4896/ad3f85Search in Google Scholar

[2] Rabia M, Aldosari E, Abdelazeez AAA. An advanced optoelectronic apparatus utilizing poly(2-amino thiophenol) adorned with a needle-shaped MnS-MnO2 nanocomposite. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron. 2024;35:1–12.10.1007/s10854-024-12177-4Search in Google Scholar

[3] Rabia M, Ben Gouider Trabelsi A, Alkallas FH, Elsayed AM. One pot synthesizing of cobalt (III) and (IV) oxides/polypyrrole nanocomposite for light sensing in wide optical range. Phys Scr. 2024;99:035523.10.1088/1402-4896/ad23b7Search in Google Scholar

[4] Elsayed AM, Alkallas FH, Trabelsi ABG, Rabia M. Highly uniform spherical MoO2-MoO3/polypyrrole core-shell nanocomposite as an optoelectronic photodetector in UV, Vis, and IR domains. Micromachines. 2023;14(9):1694.10.3390/mi14091694Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Trabelsi ABG, Elsayed AM, Alkallas FH, AlFaify S, Shkir M, Alrebdi TA, et al. Photodetector-based material from a highly sensitive free-standing graphene oxide/polypyrrole nanocomposite. Coatings. 2023;13:1198.10.3390/coatings13071198Search in Google Scholar

[6] Jiang M, Ding Y, Zhang H, Ren J, Li J, Wan C, et al. A novel ultrathin single-crystalline Bi2O3 nanosheet wrapped by reduced graphene oxide with improved electron transfer for Li storage. J Solid State Electrochem. 2020;24:2487–97.10.1007/s10008-020-04788-8Search in Google Scholar

[7] Kanwal S, Khan MI, Uzair M, Fatima M, Bukhari MA, Saman Z, et al. A facile green approach to the synthesis of Bi2WO6@V2O5 heterostructure and their photocatalytic activity evaluation under visible light irradiation for RhB dye removal. Arab J Chem. 2023;16:104685.10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.104685Search in Google Scholar

[8] Shaban M, Rabia M, El-Sayed AMA, Ahmed A, Sayed S. Photocatalytic properties of PbS/graphene oxide/polyaniline electrode for hydrogen generation. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–13.10.1038/s41598-017-14582-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Rabia M, Mohamed HSH, Shaban M, Taha S. Preparation of polyaniline/PbS core-shell nano/microcomposite and its application for photocatalytic H2 electrogeneration from H2O. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1107.10.1038/s41598-018-19326-wSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Trabelsi ABG, Rabia M, Alkallas FH, Elsayed AM. A two-symmetric electrode hydride supercapacitor developed from G-C3N4 decorated with Poly-2-aminobenzenethiol. Phys Scr. 2024;99(6):065047.10.1088/1402-4896/ad4924Search in Google Scholar

[11] Alkallas FH, Elsayed AM, Trabelsi ABG, Rabia M. Quantum dot supernova-like-shaped Arsenic (III) sulfide-oxide/polypyrrole thin film for optoelectronic applications in a wide optical range from ultraviolet to infrared. Catalysts. 2023;13:1274.10.3390/catal13091274Search in Google Scholar

[12] Anujency M, Ibrahim MM, Vinoth S, Alkallas FH, Trabelsi ABG, Ahmad Z, et al. Co:ZnO nanorods synthesis and fabrication of a high-performance photosensor for cost-effective optoelectronic devices. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron. 2024;35:1–14.10.1007/s10854-024-13242-8Search in Google Scholar

[13] Shkir M, Khan MT, Khan A. Impact of Mo doping on photo-sensing properties of ZnO thin films for advanced photodetection applications. J Alloy Compd. 2024;985:174009.10.1016/j.jallcom.2024.174009Search in Google Scholar

[14] Tan WC, Shih WH, Chen YF. A highly sensitive graphene-organic hybrid photodetector with a piezoelectric substrate. Adv Funct Mater. 2014;24:6818–25.10.1002/adfm.201401421Search in Google Scholar

[15] Zheng L, Zhu T, Xu W, Liu L, Zheng J, Gong X, et al. Solution-processed broadband polymer photodetectors with a spectral response of up to 2.5 μm by a low bandgap donor–acceptor conjugated copolymer. J Mater Chem C. 2018;6:3634–41.10.1039/C8TC00437DSearch in Google Scholar

[16] Zheng L, Yu P, Hu K, Teng F, Chen H, Fang X. Scalable-production, self-powered TiO2 nanowell-organic hybrid UV photodetectors with tunable performances. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8:33924–32.10.1021/acsami.6b11012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Qi J, Han J, Zhou X, Yang D, Zhang J, Qiao W, et al. Optimization of Broad-Response and High-Detectivity Polymer Photodetectors by Bandgap Engineering of Weak Donor-Strong Acceptor Polymers. Macromolecules. 2015;48:3941–8.10.1021/acs.macromol.5b00859Search in Google Scholar

[18] Perveen A, Movsesyan A, Abubakar SM, Saeed F, Hussain S, Raza A, et al. In-situ fabricated and plasmonic enhanced MACsPbBr3-polymer composite perovskite film based UV photodetector. J Mol Struct. 2023;1279:134962.10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.134962Search in Google Scholar

[19] Wang SB, Hsiao CH, Chang SJ, Lam KT, Wen KH, Hung SC, et al. A CuO nanowire infrared photodetector. Sens Actuators A: Phys. 2011;171:207–11.10.1016/j.sna.2011.09.011Search in Google Scholar

[20] Popoola AJ, Gondal MA, Oloore LE, Buliyaminu IA, Popoola IK, Aziz MA. Carbon dopants carriers facilitators as agents for improving hole extraction efficiency of cobalt tetraoxide nanoparticles employed in fabrication of photodetectors. Mater Res Bull. 2021;141:111331.10.1016/j.materresbull.2021.111331Search in Google Scholar

[21] Aldosari E, Rabia M, Abdelazeez AA. Rod-shaped Mo(VI) trichalcogenide – Mo(VI) oxide decorated on poly (1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency. Green Process Synth. 2024;1–12.10.1515/gps-2023-0243Search in Google Scholar

[22] Hameed SA, Ewais HA, Rabia M. Dumbbell-like shape Fe2O3/poly-2-aminothiophenol nanocomposite for two-symmetric electrode supercapacitor application. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron. 2023;34:1–8.10.1007/s10854-023-10586-5Search in Google Scholar

[23] Azzam EMS, Abd El-Salam HM, Aboad RS. Kinetic preparation and antibacterial activity of nanocrystalline poly(2-aminothiophenol). Polym Bull. 2019;76:1929–47.10.1007/s00289-018-2405-zSearch in Google Scholar

[24] Jabeen Fatima MJ, Niveditha CV, Sindhu S. α-Bi2O3 photoanode in DSSC and study of the electrode–electrolyte interface. RSC Adv. 2015;5:78299–305.10.1039/C5RA12760BSearch in Google Scholar

[25] Li L, Zhang M, Zhao Z, Sun B, Zhang X. Visible/near-IR-light-driven TNFePc/BiOCl organic-inorganic heterostructures with enhanced photocatalytic activity. Dalton Trans. 2016;45:9497–505.10.1039/C6DT01091ASearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Lim DJ, Marks NA, Rowles MR. Universal Scherrer equation for graphene fragments. Carbon. 2020;162:475–80.10.1016/j.carbon.2020.02.064Search in Google Scholar

[27] Zhang M, Duo F, Lan J, Zhou J, Chu L, Wang C, et al. In situ synthesis of a Bi2O3 quantum dot decorated BiOCl heterojunction with superior photocatalytic capability for organic dye and antibiotic removal. RSC Adv. 2023;13:5674–86.10.1039/D2RA07726DSearch in Google Scholar

[28] Wu K, Qin Z, Zhang X, Guo R, Ren X, Pu X. Z-scheme BiOCl/Bi–Bi2O3 heterojunction with oxygen vacancy for excellent degradation performance of antibiotics and dyes. J Mater Sci. 2020;55:4017–29.10.1007/s10853-019-04300-2Search in Google Scholar

[29] Haryński Ł, Olejnik A, Grochowska K, Siuzdak K. A facile method for Tauc exponent and corresponding electronic transitions determination in semiconductors directly from UV–Vis spectroscopy data. Opt Mater. 2022;127:112205.10.1016/j.optmat.2022.112205Search in Google Scholar

[30] García-Cabezón C, Godinho V, Pérez-González C, Torres Y, Martín-Pedrosa F. Electropolymerized polypyrrole silver nanocomposite coatings on porous Ti substrates with enhanced corrosion and antibacterial behavior for biomedical applications. Mater Today Chem. 2023;29:101433.10.1016/j.mtchem.2023.101433Search in Google Scholar

[31] Jagadeesan D, Deivasigamani P. Facile fabrication of novel In2S3–BiOCl nanocomposite-supported porous polymer monolith as new generation visible-light-responsive photocatalyst for decontaminating persistent toxic pollutants. Mater Today Sustainability. 2023;23:100428.10.1016/j.mtsust.2023.100428Search in Google Scholar

[32] Alnuwaiser MA, Rabia M. One-pot fabrication of open-spherical shapes based on the decoration of copper sul fi de/poly- O - amino benzenethiol on copper oxide as a promising photocathode for hydrogen generation from the natural source of Red Sea water. Nanotechnol Rev. 2024;13(1):20240098.10.1515/ntrev-2024-0098Search in Google Scholar

[33] Kwon JH, Choi KC. Highly reliable and stretchable OLEDs based on facile patterning method: toward stretchable organic optoelectronic devices; 2024.Search in Google Scholar

[34] An X, Kays JC, Lightcap IV, Ouyang T, Dennis AM, Reinhard BM. Wavelength-dependent bifunctional plasmonic photocatalysis in Au/chalcopyrite hybrid nanostructures. ACS Nano. 2022;16:6813–24.10.1021/acsnano.2c01706Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Xia Z, Tao Y, Pan Z, Shen X. Enhanced photocatalytic performance and stability of 1T MoS2 transformed from 2H MoS2 via Li intercalation. Results Phys. 2019;12:2218–24.10.1016/j.rinp.2019.01.020Search in Google Scholar

[36] Naldoni A, Guler U, Wang Z, Marelli M, Malara F, Meng X, et al. Broadband hot-electron collection for solar water splitting with plasmonic titanium nitride. Adv Opt Mater. 2017;5:1601031.10.1002/adom.201601031Search in Google Scholar

[37] Chen H, Yu P, Zhang Z, Teng F, Zheng L, Hu K, et al. Ultrasensitive self-powered solar-blind deep-ultraviolet photodetector based on all-solid-state polyaniline/MgZnO bilayer. Small. 2016;12:5809–16.10.1002/smll.201601913Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Sreedhar A, Ta QTH, Noh JS. Versatile role of 2D Ti3C2 MXenes for advancements in the photodetector performance: A review. J Ind Eng Chem. 2023.10.1016/j.jiec.2023.07.014Search in Google Scholar

[39] Liu K, Sakurai M, Liao M, Aono M. Giant improvement of the performance of ZnO nanowire photodetectors by Au nanoparticles. J Phys Chem C. 2010;114:19835–9.10.1021/jp108320jSearch in Google Scholar

[40] Kalra A, Vura S, Rathkanthiwar S, Muralidharan R, Raghavan S, Nath DN. Demonstration of high-responsivity epitaxial β-Ga2O3/GaN metal-heterojunction-metal broadband UV-A/UV-C detector. Appl Phys Express. 2018;11:064101.10.7567/APEX.11.064101Search in Google Scholar

[41] Zheng L, Hu K, Teng F, Fang X. Novel UV–visible photodetector in photovoltaic mode with fast response and ultrahigh photosensitivity employing Se/TiO2 nanotubes heterojunction. Small. 2017;13:1602448.10.1002/smll.201602448Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Bai Z, Zhang Y. Self-powered UV–visible photodetectors based on ZnO/Cu2O nanowire/electrolyte heterojunctions. J Alloy Compd. 2016;675:325–30.10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.03.051Search in Google Scholar

[43] Costas A, Florica C, Preda N, Apostol N, Kuncser A, Nitescu A, et al. Radial heterojunction based on single ZnO-CuxO core-shell nanowire for photodetector applications. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1–9.10.1038/s41598-019-42060-wSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Lan T, Fallatah A, Suiter E, Padalkar S. Size controlled copper (I) oxide nanoparticles influence sensitivity of glucose biosensor. Sensors. 2017;17:1944.10.3390/s17091944Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Hong Q, Cao Y, Xu J, Lu H, He J, Sun JL. Self-powered ultrafast broadband photodetector based on p-n heterojunctions of CuO/Si nanowire array. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6:20887–94.10.1021/am5054338Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Ismail RA, Mousa AM, Shaker SS. Visible-enhanced silver-doped PbI2 nanostructure/Si heterojunction photodetector: effect of doping concentration on photodetector parameters Opt Quantum Electron. 2019;51:1–19.10.1007/s11082-019-2063-xSearch in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites