Abstract

In environmental research, along with discovering methods for adsorbing heavy metals, it is essential to comprehend the processes of desorption and recovery of these heavy metals from adsorbent materials and their reuse. In this study, halloysite (HAL) clay, obtained from the Thach Khoan, Vietnam, was utilized for the removal of Co2+ ions from an aqueous solution, and the influence of different factors on the adsorption properties of Co2+ was investigated. Optimal conditions determined were 0.8 g HAL mass per 50 mL of solution, initial Co2+ concentration of 40 mg·L−1, contact time of 80 min, pH0 of 6.09, and room temperature of 30°C. Under these conditions, the adsorption efficiency and capacity obtained were 76.358 ± 0.981% and 1.909 ± 0.025 mg·g−1, respectively. The adsorption process followed the Langmuir adsorption isotherms, with a maximum monolayer adsorption capacity of 3.10206 ± 0.13551 mg·g−1, and exhibited a pseudo-second-order kinetic model. Desorption experiments were conducted using the electrochemical method with a deep eutectic solvent based on choline chloride and urea (reline). The results demonstrated that 94.11% of the Co metal could be recovered through electrodeposition after 5 h, using an applied current of 7.5 mA at 60°C. The HAL material was successfully regenerated following the desorption process.

1 Introduction

Halloysite (HAL) belongs to the kaolin mineral group, which includes minerals such as kaolinite, dickite, nacrite, and HAL itself. HAL occurs in two main polymorphs: a fully hydrated form with the chemical formula Al2Si2O5(OH)4·2H2O and a dehydrated form with the chemical formula Al2Si2O5(OH)4 [1]. HAL can exhibit various morphological forms, including tubular, spherical, and layered structures. In recent years, HAL has gained significant attention from scientists due to its unique properties, such as its tubular structure, non-toxicity, large surface area, high mechanical strength, and cost-effectiveness compared to nanotubular carbon. As a result, HAL has found applications in various fields, including pharmaceuticals, medicine, food, high-grade materials, agriculture, and environmental applications [2,3]. In particular, HAL has proven to be an effective adsorbent for heavy metals [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

Among the various methods available for treating water pollution caused by heavy metals, adsorption has emerged as a promising approach due to its simplicity, effectiveness, and broad applicability. In adsorption, the choice of adsorbent material plays a crucial role. Many studies have focused on utilizing natural and environmentally friendly materials as adsorbents for heavy metal removal. Cellulose has been investigated as an adsorbent for heavy metal removal [13,14]. Similarly, chitosan has shown promise in adsorbing heavy metals [15,16]. Hydroxyapatite [17], montmorillonite [18], natural clay [19], and plant straw [20] have also been explored as effective adsorbents for heavy metal adsorption.

There has been extensive research on heavy metal adsorption from the environment and industrial wastewater. However, studies focusing on the desorption and recovery of heavy metals from adsorbed materials and the regeneration of adsorbents for subsequent adsorption processes have received limited attention. Yet, the desorption of heavy metals from adsorbed materials is crucial to prevent secondary pollution and to enable the reuse of materials. Although some studies have been published on the desorption and recovery of heavy metals from hydroxyapatite [21,22,23,24,25,26,27] and clays [28,29,30], there are few published studies specifically addressing the desorption, recovery, and reuse of heavy metals from HAL [9,10,28]. For instance, Itami and Yanai investigated the sorption/desorption properties of Cd and Cu on five clay types, highlighting the influence of the clays’ charge characteristics and pH [28]. Another study by Helios Rybicka et al. examined the adsorption/desorption behavior of Cd, Cu, Pb, Zn, and Ni on illite, beidellite, and montmorillonite. The results showed that the adsorption capacity of the clays was higher for Pb and Cu ions than for Ni, Zn, and Cd ions. Furthermore, the desorption properties varied, with Pb > Cd > > Cu > Ni > Zn for beidellite and Pb > Cd ∼ Cu > Ni > Zn for illite and montmorillonite using NaNO3 as the eluent agent [29].

Cobalt is an essential trace element that is naturally present in all organs and cells of the body. It plays a vital role in synthesizing vitamin B12 and certain enzymes. However, excessive cobalt absorption at high concentrations can pose severe risks to humans, animals, and plants. Exposure to elevated levels of cobalt can lead to respiratory symptoms, lung damage, hypothyroidism, dermatitis, heart disease, and hearing and vision loss, among other health issues. Studies have demonstrated that plant mortality can occur when the cobalt concentration in the soil solution exceeds 10 mg·L−1.

Similarly, fish can die when the cobalt concentration in water surpasses 5 mg·L−1. To regulate and maintain safe levels, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations has set guidelines specifying that the cobalt content in irrigation water should not exceed 100 μg·L−1, and the concentration of cobalt ions in wastewater must be kept below 1.0 mg·L−1 [31]. These guidelines safeguard organisms’ health and mitigate the potential adverse effects of elevated cobalt concentrations.

Indeed, cobalt adsorption has been a subject of interest and research using various adsorbent materials. Different types of adsorbents have shown positive results in treating cobalt in water. Activated carbons produced from waste potato peels were also utilized for Co(ii) adsorption from synthetic water. The resulting carbon materials had different surface areas depending on the processing temperature, and the maximum adsorption capacity reached up to 405 mg·g−1 at an optimum pH of 6 [32]. The combination of HAL and cellulose into polyurethane foam also improved the adsorption capacity of the foam to metal ions in the solution. Various functional groups in HAL and cellulose contributed to electrostatic bonds between the adsorbent and metal ions, leading to increased adsorption capacity [33]. However, despite these promising results with other metals, fewer reports have been published specifically on Co(ii) adsorption using HAL. This indicates the need for more research to explore and optimize the potential of HAL as an effective adsorbent for cobalt ions.

In this study, we aim to adsorb Co2+ ions using HAL clay as the adsorbent material. Subsequently, we focus on the desorption and recovery of cobalt from the adsorbed HAL material using an electrolysis process in a reline electrolyte, a non-toxic deep eutectic solvent (DES). DESs have gained attention in recent years. These solvents can be easily formed by mixing two safe components that are cost-effective, renewable, and biodegradable, capable of creating a eutectic mixture. Choline chloride (ChCl) is a commonly used component for generating DESs. Several publications have reported successful cobalt deposition from DESs formed with ChCl [34,35,36,37]. Our study’s main advantage lies in performing cobalt’s desorption and recovery process simultaneously within an electrochemical cell. This approach allows for the reuse of the HAL adsorbent, minimizing waste and maximizing the efficiency of cobalt recovery.

2 Experimental method

2.1 Preparation of HAL powder

The HAL material was collected from the Lang Dong mine in Phu Tho province, Vietnam. After collection, the sample was mixed thoroughly and separated using the wet sieving method to achieve a particle size of less than 32 µm. The separated sample with a particle size of <32 µm was then dried at 60°C and finely ground using an agate mortar. The resulting HAL powder was used for subsequent analysis and experiments.

2.2 Preparation of DES

The DESs used in the study were prepared by mixing ChCl (Alfa Aesar, purity ≥98%) and urea (U; VWR Chemicals, NORMAPUR). ChCl was recrystallized from absolute ethanol (VWR Chemicals, NORMAPUR), followed by filtration and drying under vacuum. ChCl and U were then combined in a 1:2 molar ratio within a closed container. The mixture was stirred continuously for 3 h at 60°C until a homogeneous colorless liquid, known as ChCl-U (Reline) DES, was formed.

2.3 Determination of pHPZC of HAL powder

A mixture of 0.5 g HAL powder was combined with 50.0 mL of 0.01 M KNO3 solution. The mixture was stirred for 60 min at room temperature. To adjust the initial pH values (pH0), either a 0.1 M KOH solution or a 0.1 M HNO3 solution was used within a pH range of 2.5–9.5. Once the equilibrium was reached, the pH values were measured again (pHf). The point of zero charge (pHPZC) was determined from the ∆pH = f(pH0) plot, where ∆pH represents the difference between pH0 and pHf. The pHPZC corresponds to the pH0 value when ∆pH equals zero.

2.4 Adsorption experiments

The experiments were conducted at room temperature with continuous stirring at 400 rpm, a contact time studied from 10 to 120 min, pH from 2.37 to 6.99, mass of HAL changed from 0.3 to 1.2 g, initial concentration of Co2+ verified between 10 and 80 mg·L−1. After the adsorption process, the solution was filtered to remove the solid HAL material, and the remaining concentration of Co2+ was determined using the Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) method on ICAP Q ICP-MS (Thermo Scientific, Germany) instrument.

The adsorption capacity and efficiency were calculated using Eqs. 1 and 2, respectively [38] as follows:

The amount of metal ion adsorbed on the adsorbent at equilibrium (Q) is calculated using the equation Q = (C 0 − C) × V/m, where C 0 and C represent the initial and equilibrium concentrations (mg·L−1) of Co2+ ions in the solution, respectively. V denotes the volume of the solution (L), and m is the mass of the adsorbent (g).

The experimental data obtained are analyzed using the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models [39].

Langmuir non-linear equation:

Freundlich non-linear equation:

where C e (mg·L−1) is the equilibrium concentration of Co2+, Q (mg·g−1) is the amount adsorbed at equilibrium, Q m (mg·g−1) is the maximum adsorption capacity, K L is the Langmuir coefficient related to the adsorption energy, K F and n are the constants of the Freundlich model.

The adsorption kinetics is described by the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order kinetic models using Eqs. 5 and 6, respectively [40].

where Q e is the adsorption capacity at equilibrium (mg·g−1), Q t is the adsorption capacity at time t (mg·g−1), and k 1 and k 2 are the pseudo-first-order (min·L) and pseudo-second-order (g·mg−1·min−1) rate constants, respectively.

Physicochemical characteristics of HAL before and after Co2+ adsorption were analyzed by the following methods: The phase component was analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD) (Siemens D5000 diffractometer, CuKα-radiation, λ = 1.54056 Å, with a step angle of 0.030°, scanning rate of 0.04285°·s−1, and 2θ in the range of 20–70°). The structure was analyzed by infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) on a Nicolet iS10 instrument (Thermo Scientific, USA). Morphology and element components were analyzed by SEM-EDX on a FE-SEM-JSM-IT800 instrument (JEOL, Japan).

2.5 Electrochemistry experiments for desorption and recovery cobalt

2.5.1 Cyclic voltammetry scan in reline solvent

In the cyclic voltammetry scan experiments, a three-electrode system was used, and it was connected to an Autolab PGSTAT20 potentiostat from Metrohm. The working electrode (WE) used was a gold (Au) electrode with a geometric area of 0.0201 cm2. The reference electrode (RE) was an Ag/AgCl electrode with a chloride-ion-saturated potassium chloride solution (Ag, AgCl|Cl−), and the counter electrode (CE) was a platinum grid with a large area. A sample volume of 5 mL of reline DES containing either 0.5 g of Co(NO3)2 or 0.5 g of Co-HAL was used for the experiments. The scan potential range was set from −0.2 to −1.5 V, and the scan rate was 50 mV·s−1. The experiments were carried out at a temperature of 60°C. Before the experiments, the WE (Au electrode) was polished using an alumina-water slurry on a smooth polishing cloth. It was then sonicated twice for 3 min and rinsed with Milli-Q water to ensure no remaining alumina. Finally, it was dried under a nitrogen atmosphere. The platinum CE was cleaned by flaming it until it reached a red glow. Before each experiment, the DES medium was purged with nitrogen for at least 20 min, and during all measurements, the system was kept under a nitrogen atmosphere. This careful preparation and control of the experimental conditions ensured accurate and reliable results during the cyclic voltammetry scans in the reline DES.

2.5.2 Desorption of Co2+ and deposition of Co metal on the surface of an electrode

The desorption of Co2+ from Co-HAL and the subsequent electrodeposition of Co metal were performed in a three-electrode electrochemical cell. The WE used was a gold plate with a geometric area of 1 cm2. The RE used was Ag/AgCl with a chloride-ion-saturated potassium chloride solution (Ag, AgCl|Cl−), and the CE was a platinum grid with a large area. Cobalt recovery was carried out using the electrodeposition method in the reline solvent. The deposition potential was set to be less than or equal to −1.3 V, and the temperature was maintained at 60°C. Before starting the electrolysis process, the DES medium was purged with nitrogen for at least 20 min, and the nitrogen atmosphere was maintained throughout the electrolysis. Different applied current values of 1, 2, 3, 5, and 7.5 mA were used, and the electrolytic time was varied from 1 to 5 h. After the electrolysis process, the Co-HAL powder was filtered out from the mixture. Then, it underwent cleaning, drying, and the remaining Co in the powder was determined by the ICP-MS method.

The surface of the Au electrode before and after electrolysis was analyzed by SEM-EDX. The phase component of initial HAL and reused HAL after the desorption process of Co2+ were analyzed using XRD.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Effect of the experimental factors on Co2+ ions adsorption by HAL powder

3.1.1 pHPZC of HAL

The change in ΔpH against pH0 is presented in Figure 1. Based on the graph, it can be observed that ΔpH equals zero when the pH0 value is 5.99. This indicates that the point of zero charge (pHPZC) for the HAL material used in the study is determined to be 5.99. The pHPZC represents the pH value at which the surface charge of the material is neutral, indicating that the material has no net positive or negative charge.

Determination of pHPZC of HAL powder.

3.1.2 Effect of contact time

The contact time between the solid adsorbent (HAL) and the metal ion solution (Co2+) plays a crucial role in adsorption. To investigate the influence of contact time on HAL’s adsorption ability for Co2+ ions, experiments were conducted for 10–120 min using a 50 mg·L−1 Co2+ solution. As shown in Table 1, the results indicate that as the contact time increased, the adsorption capacity and efficiency of the HAL for Co2+ ions gradually increased. However, once the contact time reached 80 min, the adsorption capacity and efficiency became nearly stable. This suggests that after 80 min, the adsorption process of Co2+ ions by HAL reached equilibrium, with no significant further increase in adsorption. Based on these findings, a contact time of 80 min was chosen for subsequent studies, representing the time required to achieve equilibrium in the Co2+ adsorption process by HAL.

Effect of contact time on the HAL’s adsorption of Co2+ at an initial concentration of 50 mg·L−1, HAL dosage 0.5 g, and pH = 6.09

| t (min) | C e (mg·L−1) | H% | Q (mg·g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 28.780 ± 0.514 | 42.441 ± 1.027 | 2.122 ± 0.051 |

| 20 | 27.561 ± 0.818 | 44.878 ± 1.636 | 2.244 ± 0.082 |

| 30 | 26.170 ± 0.314 | 47.660 ± 0.629 | 2.383 ± 0.031 |

| 40 | 25.670 ± 0.401 | 48.660 ± 0.802 | 2.433 ± 0.040 |

| 50 | 24.923 ± 0.545 | 50.155 ± 1.090 | 2.508 ± 0.055 |

| 60 | 24.452 ± 0.620 | 51.096 ± 1.241 | 2.555 ± 0.062 |

| 80 | 24.333 ± 0.496 | 51.334 ± 0.991 | 2.567 ± 0.050 |

| 100 | 24.226 ± 0.430 | 51.548 ± 0.860 | 2.577 ± 0.043 |

| 120 | 24.205 ± 0.575 | 51.590 ± 1.150 | 2.580 ± 0.058 |

3.1.3 Effect of solution pH

The effect of pH on the Co2+ adsorption capacity of HAL was investigated because changes in solution pH can influence the surface properties of the adsorbent and the form of metal ions in the solution. The study was conducted with the Co2+ solution having a concentration of 50 mg·L−1, and the pH values were varied around the pHPZC value of HAL, which was determined to be 5.99. However, it is essential to note that precipitation of Co2+ hydroxide starts to occur at a pH of 7.8 [41]. To accurately assess the amount of ion depletion in the solution due to adsorption on HAL, the pH was controlled to be less than 7.8. As shown in Table 2, the results demonstrated that within the investigated pH range, both the adsorption efficiency and capacity of Co2+ ions by HAL increased as the pH increased. This can be explained by the protonation of HAL in acidic environments, resulting in a positively charged surface. Consequently, the number of adsorption sites for positive ions on HAL decreased, and competitive adsorption occurred between H+ ions and Co2+ ions on the surface of HAL, leading to a decrease in the adsorption ability of Co2+ ions [40]. As the pH increased, the positive charge density on the surface of HAL decreased, thereby enhancing the adsorption capacity of Co2+ ions. Favorable adsorption of Co2+ ions occurred when the pH was higher than the pHPZC value of HAL. To facilitate the treatment of larger quantities without the need for pH adjustment, an initial pH of 6.09 was selected for Co2+ adsorption in subsequent studies. The adsorption efficiency and capacity reached 51.334 ± 1.047% and 2.567 ± 0.052 mg·g−1 at this pH, respectively.

Effect of pH on the HAL’s adsorption of Co2+ at an initial concentration of 50 mg·L−1, HAL dosage of 0.5 g, and contact time of 80 min

| t (min) | C e (mg·L−1) | H% | Q (mg·g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.37 | 41.803 ± 0.022 | 16.394 ± 0.043 | 0.820 ± 0.002 |

| 2.95 | 37.610 ± 0.466 | 24.780 ± 0.932 | 1.239 ± 0.047 |

| 4.11 | 32.850 ± 0.463 | 34.300 ± 0.925 | 1.715 ± 0.046 |

| 5.02 | 28.580 ± 0.521 | 42.840 ± 1.042 | 2.142 ± 0.052 |

| 6.09 | 24.333 ± 0.524 | 51.334 ± 1.047 | 2.567 ± 0.052 |

| 6.50 | 21.356 ± 0.607 | 57.288 ± 1.214 | 2.864 ± 0.061 |

| 6.99 | 18.661 ±0.733 | 62.678 ± 1.466 | 3.134 ± 0.073 |

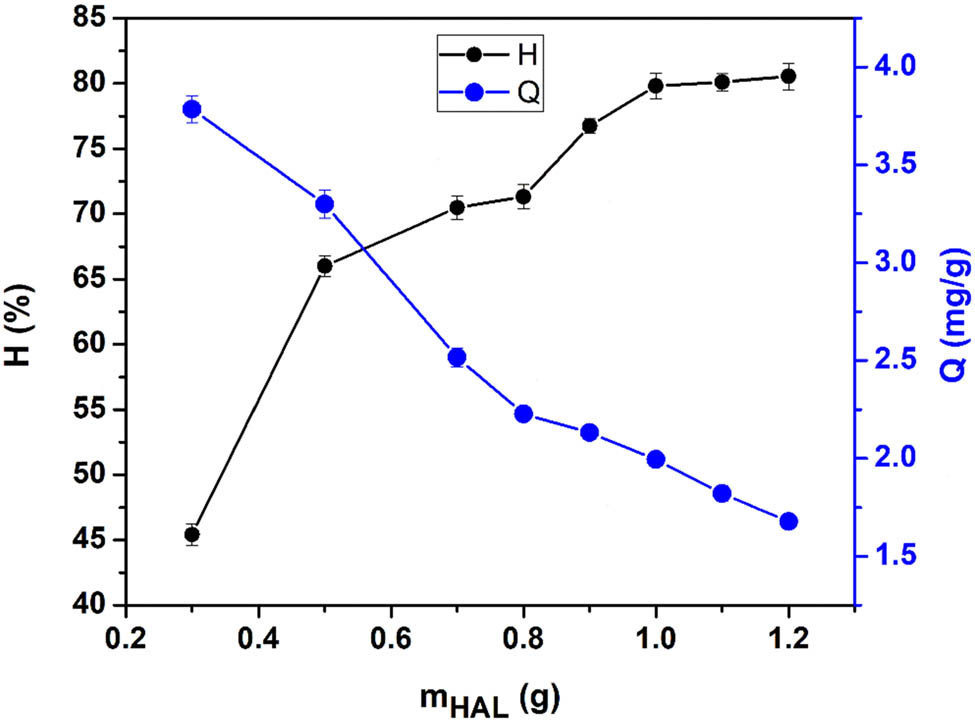

3.1.4 Effect of material mass

When the mass of the solid adsorbent in the solution increases, the contact area between the adsorbent and the solution also increases. This increases the number of active sites available for adsorption, resulting in higher adsorption efficiency [41]. This study observed that adsorption efficiency increased rapidly from 45.405 ± 0.824% to 71.308 ± 0.925% as the mass of HAL increased from 0.3 to 0.8 g (Figure 2). After reaching 0.8 g, further increases in the amount of adsorbent resulted in only slight improvements in adsorption efficiency. This is because the adsorption process reached equilibrium, and additional adsorbent did not significantly impact the overall efficiency. To achieve an appropriate magnitude of adsorption capacity and efficiency (2.228 ± 0.029 mg·g−1 and 71.308 ± 0.925%, respectively), a mass of 0.8 g of HAL was selected to study the adsorption of Co2+ ions. This mass provided optimal adsorption performance, balancing the amount of adsorbent with the achieved efficiency.

The effect of material mass on the HAL’s adsorption of Co2+ at an initial concentration of 50 mg·L−1, pH = 6.09, and contact time of 80 min.

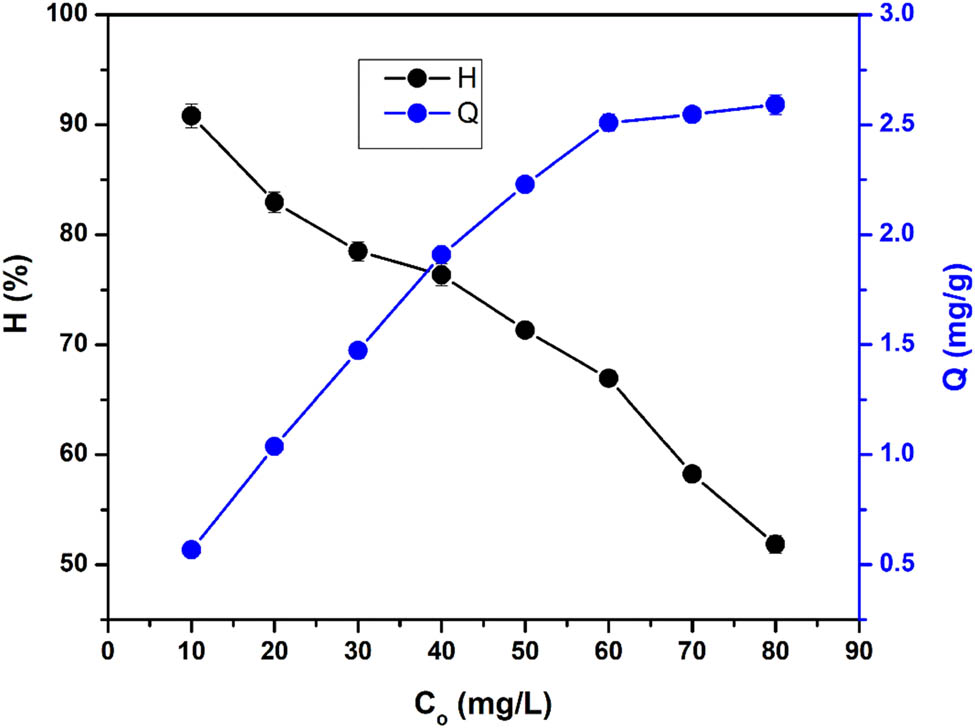

3.1.5 Effect of Co2+concentration

The investigation of the adsorption process with varying initial concentrations of Co2+ ions (20–80 mg·L−1) revealed significant findings, as shown in Table 3 and Figure 3. As the concentration of Co2+ ions increased, the adsorption capacity of HAL gradually increased while the adsorption efficiency decreased. For low initial concentrations of Co2+ ions, the adsorption of Co2+ onto HAL was favorable due to the large contact area between the Co2+ ions and the solid phase of HAL. However, as the initial concentration of Co2+ ions increased, the amount of Co2+ ions also increased. Nevertheless, the adsorption capacity of HAL reached saturation and did not increase further, resulting in a decrease in the adsorption efficiency [42]. To achieve a high simultaneous adsorption capacity and efficiency, an appropriate concentration of Co2+ ions was selected within the range of 30–50 mg·L−1. At a concentration of 40 mg·L−1 of Co2+ ions, HAL’s adsorption efficiency and capacity reached 76.358 ± 0.981% and 1.909 ± 0.025 mg·g−1, respectively. This result is considered acceptable when comparing the adsorption efficiency of HAL for Co2+ ions with other investigated metal ions, such as Cd2+ with an efficiency of 51.45% and Pb2+ with an efficiency of 79.3% [43], as well as As(iii) with an efficiency of 82.4% [42].

Values of H% and Q (mg·g−1) were calculated from the different initial concentrations of Co2+

| C o (mg·L−1) | C e (mg·L−1) | H% | Q (mg·g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.918 | 90.820 ± 1.052 | 0.568 ± 0.016 |

| 20 | 3.408 | 82.960 ± 0.937 | 1.037 ± 0.021 |

| 30 | 6.45 | 78.500 ± 0.864 | 1.472 ± 0.034 |

| 40 | 9.457 | 76.358 ± 0.981 | 1.909 ± 0.025 |

| 50 | 14.346 | 71.308 ± 0.653 | 2.228 ± 0.032 |

| 60 | 19.842 | 66.930 ± 0.724 | 2.510 ± 0.038 |

| 70 | 29.251 | 58.213 ± 0.582 | 2.547 ± 0.029 |

| 80 | 38.523 | 51.846 ± 0.806 | 2.592 ± 0.045 |

The effect of Co2+ concentration on the HAL’s adsorption of Co2+ at a dosage 0.8 g, pH = 6.09, and contact time of 80 min.

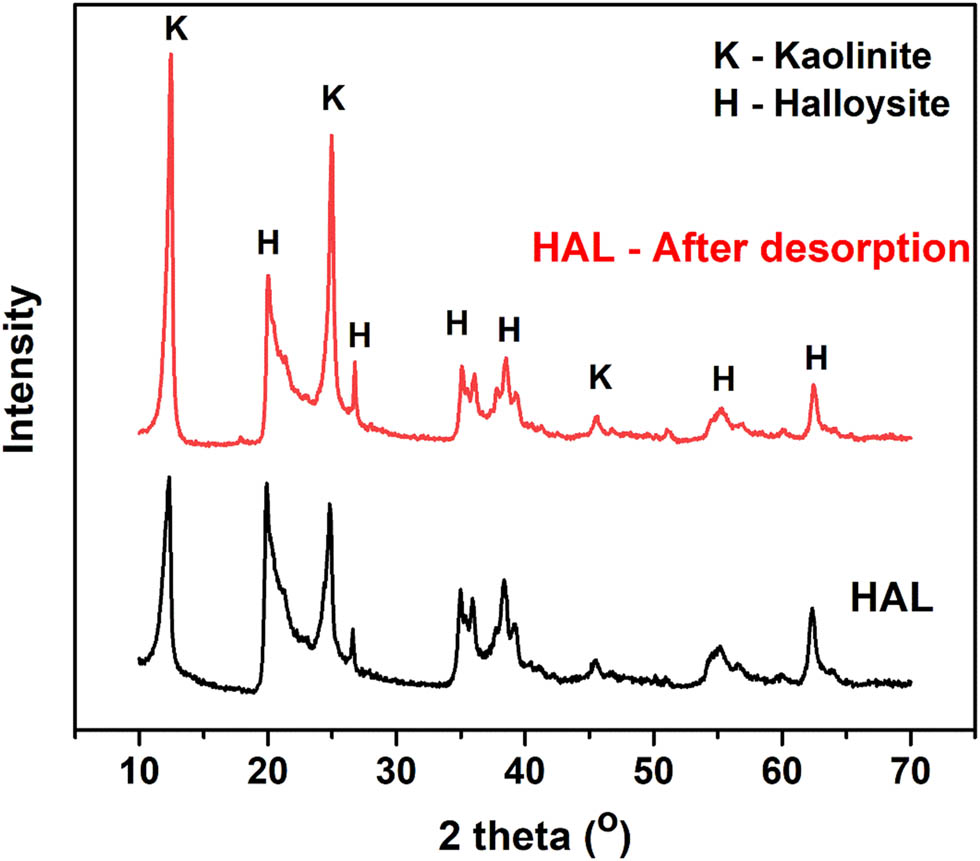

3.1.6 Characterization of HAL before and after adsorption process

The HAL powder before and after Co2+ adsorption was characterized through FT-IR, XRD, and SEM-EDX analyses (Figures 4 and 5). It can be observed that the FT-IR and XRD analysis graphs for both types of samples are similar and show no significant changes. The FT-IR spectra exhibit vibrations of O–H groups on the inner surface (at 3,695 and 3,622 cm−1), interlayer water (at 1,635 cm−1), Si–O (at 1,038 and 694 cm−1), Al–OH (at 914 cm−1), Al–O–OH (at 796, 752 cm−1), and Al–O–Si (540 cm−1) [43]. The XRD peaks at 12.4°, 25.0°, and 45.7° for kaolinite and at 20.0°, 26.7°, 35.1°, 38.4°, 55.0° and 62.5° for HAL are present in both sample types. SEM images of HAL after Co2+ adsorption show the tubular structure characteristics. However, EDS analysis results indicate the presence of the Co2+ elemental spectrum in the HAL powder after adsorption. These results suggest that HAL material has successfully adsorbed Co2+ ions. However, due to the limited amount of adsorbed ions, it has not significantly affected the morphology of the HAL mineral, as well as the FT-IR and XRD analysis results.

FT-IR spectra (a) and XRD pattern (b) of HAL before and after Co2+ adsorption process.

SEM images and EDX results of HAL before (a) and after (b) Co2+ adsorption process.

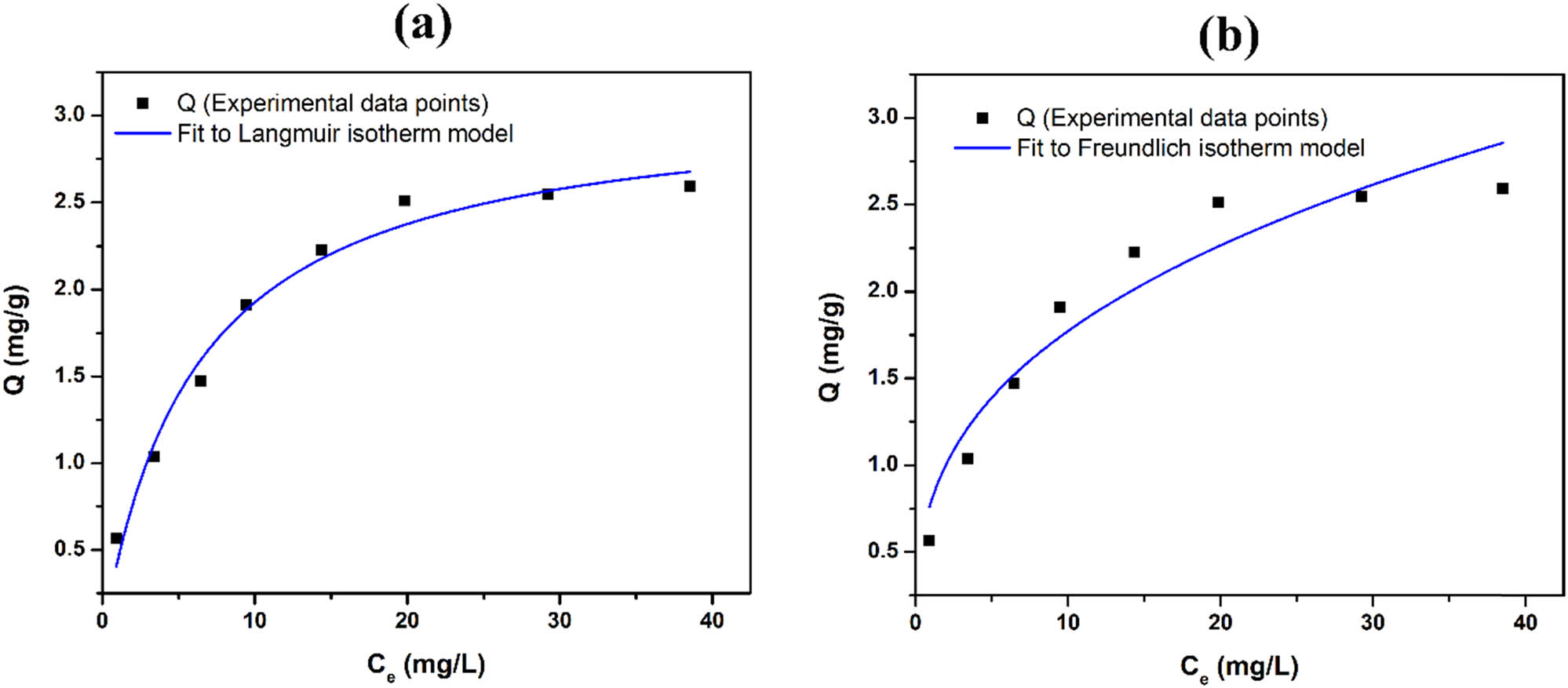

3.1.7 Adsorption isotherm

In each experiment, 0.8 g of HAL was used to adsorb Co2+ ions in a 50 mL solution with varying initial concentrations. The adsorption process was conducted at the natural pH of 6.09 and room temperature (25°C) for 80 min. The remaining Co2+ concentration at equilibrium (C e) was determined, and the adsorption capacity (Q) was calculated (Table 3). The Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm equations were constructed using Eqs. 3 and 4, respectively. The experimental data were plotted on the adsorption isotherm graphs (Figure 6). The Langmuir isotherm equation represents the maximum adsorption capacity (Q m) and the Langmuir constant (K L), while the Freundlich equation involves the experimental constants K F and n. The results presented in Table 4 indicate that the adsorption of Co2+ on HAL follows the Langmuir isotherm adsorption model (R 2 = 0.98113, Sum of the Square of the Errors (SSE) = 0.07672). This finding is consistent with numerous published results that have utilized HAL as an adsorbent for heavy metals and organic pigments [4]. The Langmuir isotherm model provides insights into the maximum adsorption capacity (3.10206) and the interaction between the adsorbate (Co2+ ions) and the adsorbent (HAL) during adsorption.

Langmuir (a) and Freundlich (b) isotherm plots for the adsorption of Co2+ onto HAL.

Adsorption isotherm parameters

| Langmuir | Freundlich | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q m | K L | R 2 | SSE | 1/n | K F | R 2 | SSE |

| 3.10206 ± 0.13551 | 0.16371 ± 0.0239 | 0.98113 | 0.07672 | 0.35363 ± 0.049 | 0.78519 ± 0.11591 | 0.78519 | 0.27993 |

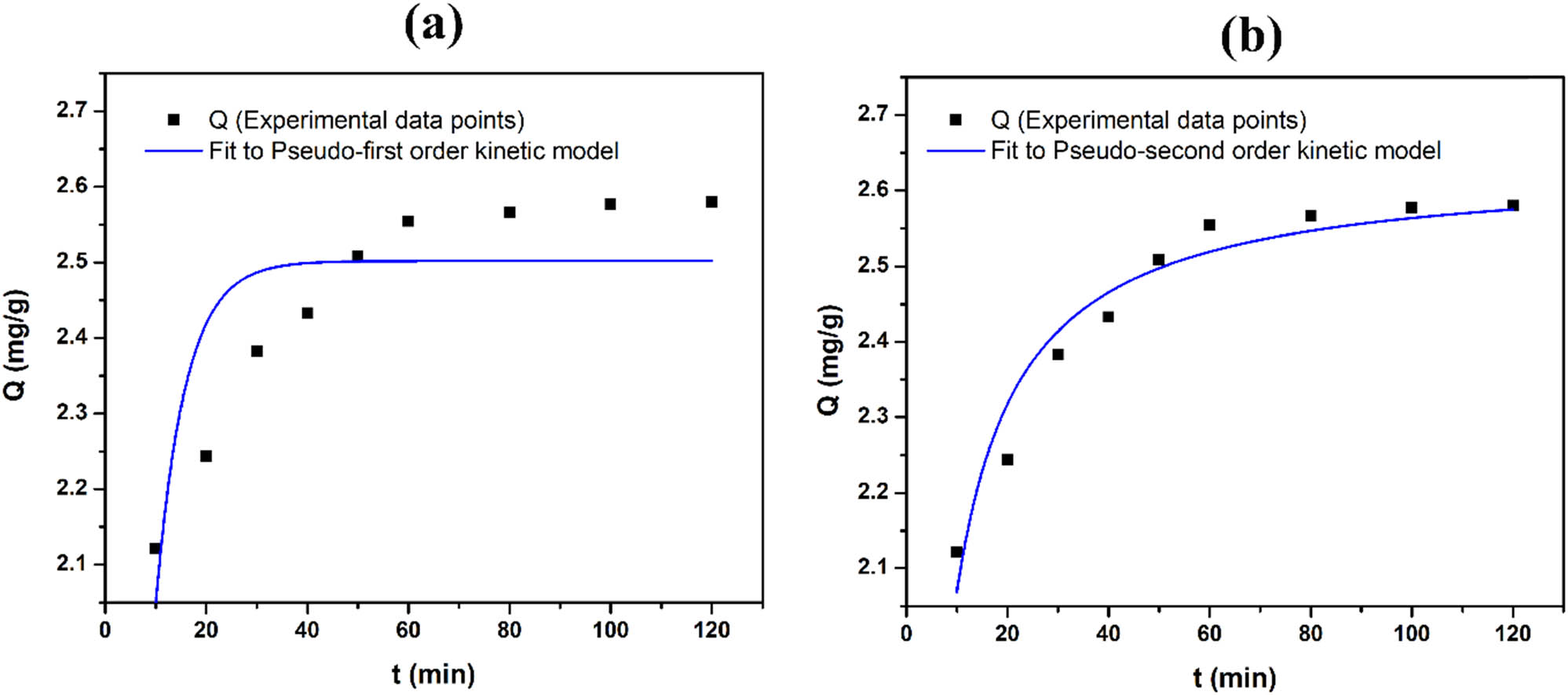

3.1.8 Adsorption kinetic

The adsorption kinetic was studied based on the effect of adsorption time on the Co2+ adsorption capacity by constructing graphs of the pseudo-first-order (Eq. 5) and pseudo-second-order kinetics (Eq. 6). The resulting graphs in Figure 7 exhibited non-linear lines for the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order modes. The regression coefficients (R 2), adsorption rate constants (k) and the adsorption capacity at equilibrium (Q e) were determined in Table 5. The results indicated that the regression coefficient of the pseudo-second-order kinetic equation (R 2 = 0.94315) was much higher than that of the pseudo-first-order kinetic equation (R 2 = 0.67314) as well as the lower value of the SSE of the pseudo-second-order kinetic equation (SSE = 0.01223) than the pseudo-first-order kinetic equation (SSE = 0.07033). This result confirms that the adsorption of Co2+ by HAL follows the pseudo-second-order adsorption kinetic. The adsorption rate constant, k, was calculated to be 0.13905 g·mg−1·min−1. This indicates that the pseudo-second-order kinetic model better describes the adsorption process, which suggests a chemisorption mechanism involving strong bonding between the adsorbate (Co2+ ions) and the adsorbent (HAL).

Isotherm plots for the adsorption of Co2+ onto HAL according to pseudo-first-order kinetic equation (a) and pseudo-second-order kinetic equation (b).

Adsorption kinetic parameters

| Pseudo-first-order kinetic equation | Pseudo-second-order kinetic equation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q e (mg·g−1) | k 1 (min−1) | R 2 | SSE | Q e (mg·g−1) | k 2 (g·mg−1·min−1) | R 2 | SSE |

| 2.50211 | 0.1703 | 0.67314 | 0.07033 | 2.63375 | 0.13905 | 0.94315 | 0.01223 |

3.2 Desorption of Co2+ out of Co-HAL and recovery of Co metal by electrodeposition method

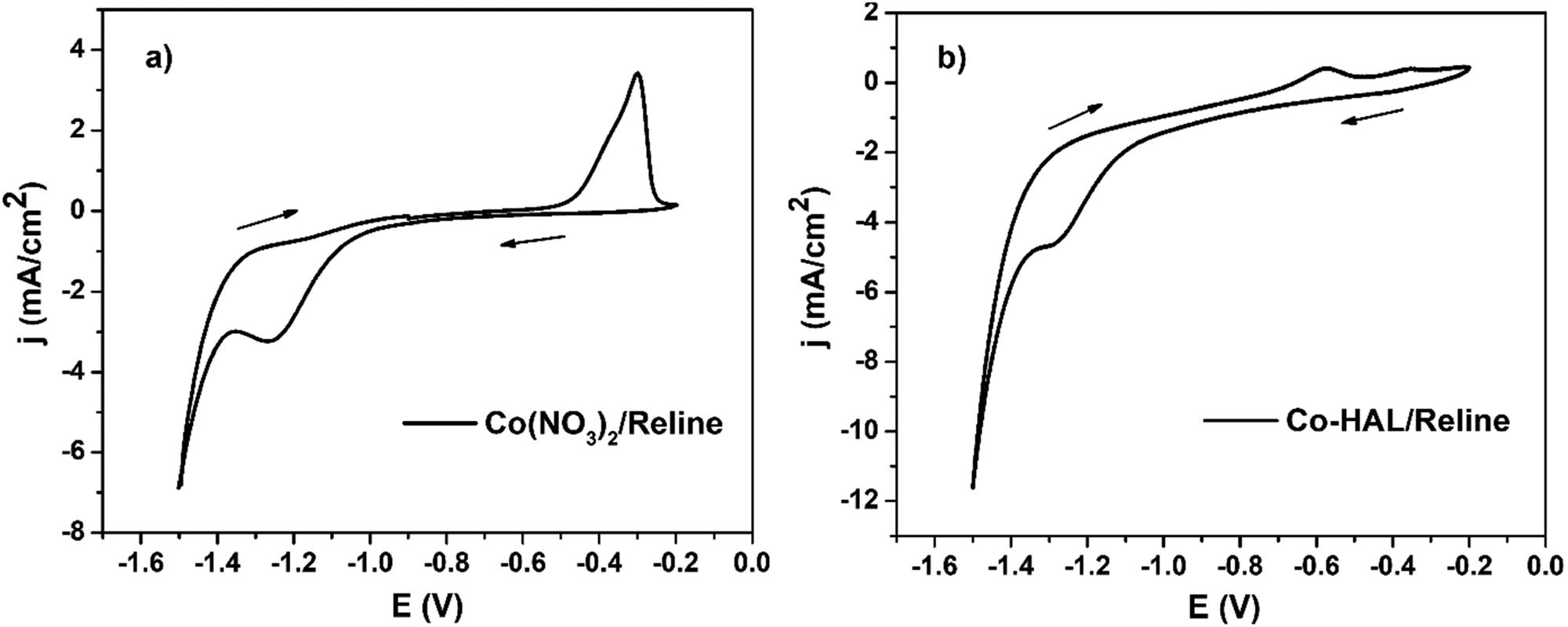

3.2.1 Cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of Co(NO3)2 and Co-HAL in the electrolyte of reline solvent

The results shown in Figure 8a demonstrate the presence of a reduction peak of Co2+ at −1.25 V and an oxidation peak of Co0 at −0.35 V in the cyclic voltammetry curve of reline containing Co(NO3)2. This observation aligns with the reported CV of reline having Co2+ in the literature [34,37]. Figure 8b presents the results of the cyclic voltammetry curve of reline containing Co-HAL, showing a reduction peak of Co2+ at −1.3 V and an oxidation peak of Co0 at −0.55 V. These results indicate a slight shift in the oxidation-reduction peaks of cobalt between Co(NO3)2/reline and Co-HAL/reline. The mechanism of the deposition and dissolution of cobalt on the Au electrode can be described as follows:

CV of 0.005 M Co2+ in the reline. A scan rate of 50 mV·S−1, T = 60°C (a). CV of 5 mL reline containing 1.2 g Co-HAL. Scan rate of 50 mV·S−1, T = 60°C (b).

Step 1: The formation of a complex between Co2+ from Co-HAL and Cl− from reline occurs, forming CoCl n 2−n . Subsequently, the reduction of Co2+ (of CoCl n 2−n ) takes place on the surface of the electrode, leading to the formation of metallic Co: CoCl n 2−n + 2e → Co + n·Cl−

Step 2: Stripping of the Co metal occurs, converting it back to Co2+: Co − 2e → Co2+

The cyclic voltammetry result of Co-HAL in reline solvent suggests that Co2+ ions can be effectively desorbed from the Co-HAL material and subsequently reduced to metallic Co on the surface of the Au electrode in the reline solvent. This electrochemical process allows for the recovery of the HAL adsorbent. The deposition of Co metal on the Au electrode surface can be achieved at a potential equal or less than −1.3 V. This possible range ensures the successful electrochemical recovery of Co from the Co-HAL material.

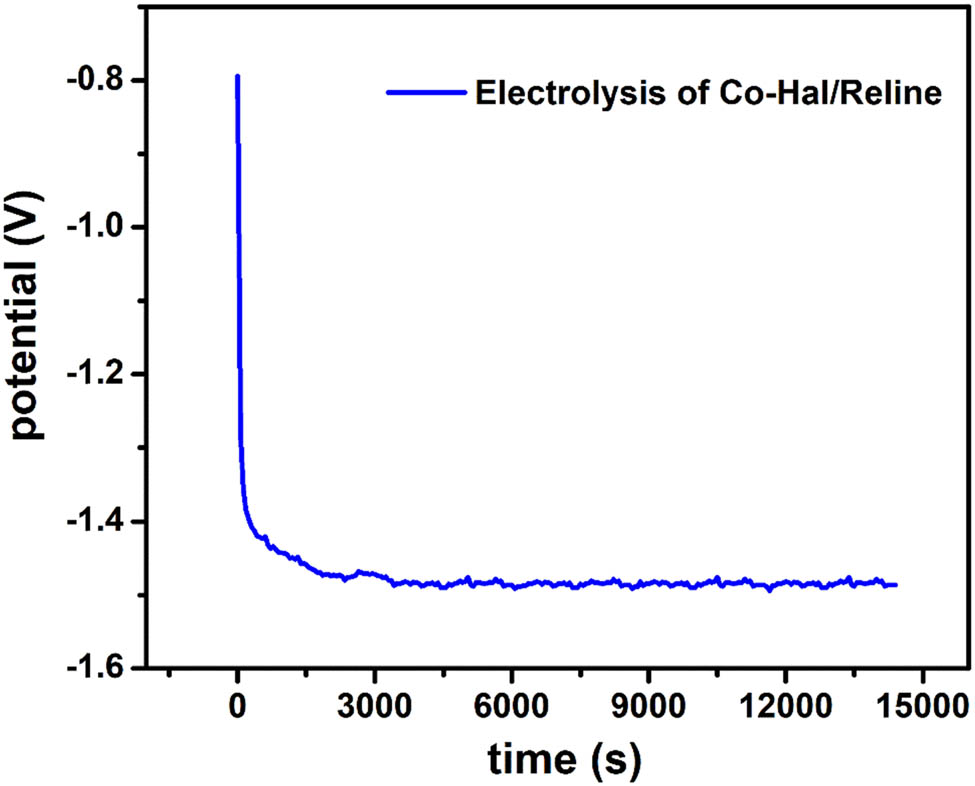

3.2.2 Effect of applied current and electrolytic time on recovery efficiency of cobalt

The recovery of cobalt was achieved through the electrodeposition method using the applied current technique. Figure 9 illustrates the process of cobalt deposition into the reline solvent through electrodeposition at the applied current of 7.5 mA. The potential reached −1.5 V and was quite stable during the electrolysis process.

Electrolysis of 5 mL reline containing 0.5 g Co-HAL at 7.5 mA applied current, scan rate of 50 mV·s−1, electrolytic time of 4 h, and T = 60°C.

The initial smooth surface of the Au electrode can be observed in Figure 10a. EDX spectroscopy analysis of the Au electrode confirmed the presence of characteristic peaks corresponding to Au, aluminum (Al), and silicon (Si), which are components of the Au electrode. After the electrolysis process, a uniform deposition of Co metal was observed on the surface of the Au electrode, as shown in Figure 10b. The EDX spectroscopy analysis of the electrode after electrolysis still indicated the presence of Co metal, confirming the successful electrodeposition of Co onto the Au electrode. To assess the recovery efficiency of Co, cathodic polarization of the Au electrode was conducted at different applied current values and electrolytic times at a temperature of 60°C. The results of the recovery efficiency of Co are presented in Table 6, providing valuable insights into the effectiveness of the electrodeposition method for Co recovery.

SEM-EDX of the surface of the Au electrode before (a) and after (b) electrolysis.

The results presented in Table 6 demonstrate the variation in the recovery efficiency of Co based on the applied current and electrolytic time. It was observed that increasing the applied current resulted in a higher amount of Co being deposited on the surface of the Au electrode, leading to an increase in the recovery efficiency of Co. Similarly, increasing the electrolytic time also led to a higher amount of Co deposition and an increase in the recovery efficiency of Co. Notably, the recovery efficiency of Co reached 94.11% after 5 h of electrolysis at an applied current of 7.5 mA. This indicates that a significant amount of Co was successfully recovered from the Co-HAL material and deposited onto the surface of the Au electrode. These findings highlight the effectiveness of the electrodeposition method in the recovery of Co, with higher applied current and longer electrolytic time contributing to higher recovery efficiency and more significant deposition of Co metal.

Recovery efficiency of Co (H %) from 0.5 g Co-HAL at different applied currents and electrolytic times

| t (h) | H% | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (mA) | ||||

| 2 | 3 | 5 | 7.5 | |

| 1 | 62.11 | 68.69 | 74.60 | 81.34 |

| 2 | 72.38 | 76.11 | 82.91 | 87.00 |

| 3 | 76.08 | 78.86 | 84.67 | 90.12 |

| 4 | 78.62 | 81.70 | 86.47 | 92.05 |

| 5 | 80.33 | 85.68 | 89.25 | 94.11 |

3.2.3 Regeneration of HAL material

During the electrolysis process, Co2+ ions were successfully desorbed from the Co-HAL material, allowing for the recovery of HAL material for further adsorption applications. Figure 11 presents the XRD pattern of the HAL material obtained after electrolysis, which closely resembles the XRD pattern of the initial HAL material. This indicates that the electrolysis process did not significantly alter the crystal structure of the HAL material. To assess the regeneration ability of the prepared sorbent, adsorption experiments were conducted under suitable conditions. After electrolysis, the obtained HAL material exhibited a Co2+ adsorption capacity (Q) of 1.55 mg·g−1 and an adsorption efficiency (H) of 61.56%. This indicates that the regenerated HAL material retains a significant adsorption capacity and efficiency for Co2+ ions. These results suggest that the electrolysis process effectively desorbs Co2+ ions from the HAL material, allowing the sorbent’s successful recovery and reuse for subsequent adsorption processes.

XRD patterns of HAL before Co2+ adsorption and after the desorption process.

4 Conclusion

HAL clay has shown a high efficiency of 76.36% in removing Co2+ ions from aqueous solutions. The equilibrium time for the adsorption process was determined to be 80 min. The adsorption isotherm results indicated that the adsorption of Co2+ ions using HAL powder followed the Langmuir isotherm model, with a maximum monolayer adsorption capacity of 2.992 mg·g−1. The adsorption kinetics data confirmed that the adsorption process of Co2+ ions on HAL powder followed the pseudo-second-order kinetic model, with a high correlation coefficient (R 2) of 0.9998. This indicates that the adsorption process is well-described by this kinetic model. The recovery of cobalt from the adsorbed HAL material was achieved through electrodeposition on the surface of an Au electrode. A recovery efficiency of 94.11% was achieved after 5 h of electrolysis at an applied current density of 7.5 mA in the reline electrolytic solution. Significantly, the HAL adsorbent was not dissolved during the electrolysis process, demonstrating its stability and the possibility of regeneration. The obtained HAL material after desorption exhibited an adsorption capacity of 1.55 mg·g−1 and an adsorption efficiency of 61.56%. This indicates that the HAL adsorbent can be successfully reused after the desorption process, making it a sustainable and cost-effective solution for heavy metal removal from aqueous solutions.

-

Funding information: The authors express their gratitude for the financial support provided by the Ministry of Education and Training (project code: B2022-MDA-03), which has played a crucial role in completing this work.

-

Author contributions: All authors contributed equally to this article.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Joussein E, Petit S, Churchman GJ, Theng BKG, Righi D, Delvaux B. Halloysite clay minerals – A review. Clay Min. 2005;40:383–426. 10.1180/0009855054040180.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Yuan P, Tan D, Annabi-Bergaya F. Properties and applications of halloysite nanotubes: Recent research advances and future prospects. Appl Clay Sci. 2015;112–113:75–93. 10.1016/j.clay.2015.05.001.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Zhang Y, Tang A, Yang H, Ouyang J. Applications and interfaces of halloysite nanocomposites. Appl Clay Sci. 2016;119:8–17. 10.1016/j.clay.2015.06.034.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Anastopoulos I, Mittal A, Usman M, Mittal J, Yu G, Núñez-Delgado A, et al. A review on halloysite-based adsorbents to remove pollutants in water and wastewater. J Mol Liq. 2018;269:855–68. 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.08.104.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Danyliuk N, Tomaszewska J, Tatarchuk T. Halloysite nanotubes and halloysite-based composites for environmental and biomedical applications. J Mol Liq. 2020;309:113077. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113077.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Maziarz P, Matusik J. The effect of acid activation and calcination of halloysite on the efficiency and selectivity of Pb(II), Cd(II), Zn(II) and As(V) uptake. Clay Min. 2016;51:385–94. 10.1180/claymin.2016.051.3.06.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Parisi F, Lazzara G, Merli M, Milioto S, Princivalle F, Sciascia L. Simultaneous Removal and Recovery of Metal Ions and Dyes from Wastewater through Montmorillonite Clay Mineral. Nanomaterials. 2019;9:1699. 10.3390/nano9121699.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Kurczewska J, Cegłowski M, Schroeder G. Alginate/PAMAM dendrimer - Halloysite beads for removal of cationic and anionic dyes. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;123:398–408. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.119.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Maziarza P, Matusika J, Radziszewska A. Halloysite-zero-valent iron nanocomposites for removal of Pb(II)/Cd(II) and As(V)/Cr(VI): Competitive effects, regeneration possibilities and mechanisms. J Environ Chem Eng. 2019;7:103507. 10.1016/j.jece.2019.103507.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Pirhaji ZJ, Moeinpour F, Dehabadi MA, Ardakani YAS. Synthesis and characterization of halloysite/graphene quantum dots magnetic nanocomposite as a new adsorbent for Pb(II) removal from water. J Mol Liq. 2020;300:112345. 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.112345.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Ramanayaka S, Sarkar B, Coorayc TA, Oke YS, Vithanage M. Halloysite nanoclay supported adsorptive removal of oxytetracycline antibiotic from aqueous media. J Hazard Mater. 2020;384:121301. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121301.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Li H, Sheng G, Teppen JB, Johnston TC, Boyd AS. Sorption and desorption of pesticides by clay minerals and humic acid-clay complexes. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 2003;67:120–31. 10.2136/sssaj2003.0122.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Kushwaha J, Singh R. Cellulose hydrogel and its derivatives: A review of application in heavy metal adsorption. Inorg Chem Commun. 2023;152:110721. 10.1016/j.inoche.2023.110721.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Jiang H, Wu S, Zhou J. Preparation and modification of nanocellulose and its application to heavy metal adsorption: A review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;236:123916. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123916.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Xu K, Li L, Huang Z, Tian Z, Li H. Efficient adsorption of heavy metals from wastewater on nanocomposite beads prepared by chitosan and paper sludge. Sci Total Environ. 2022;846:157399. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157399.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Amin FK, Gulshan F, Asrafuzzaman F, Das H, Rashid R, Hoque SM. Synthesis of mesoporous silica and chitosan-coated magnetite nanoparticles for heavy metal adsorption from wastewater. Environ Nanotechnol Monit Manag. 2023;20:100801. 10.1016/j.enmm.2023.100801.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Liu X, Yin H, Liu H, Cai Y, Qi X, Dang Z. Multicomponent adsorption of heavy metals onto biogenic hydroxyapatite: Surface functional groups and inorganic mineral facilitating stable adsorption of Pb(II). J Hazard Mater. 2023;443:130167. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.130167.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Yang S, Yang G. Origin for superior adsorption of metal ions and efficient control of heavy metals by montmorillonite: A molecular dynamics exploration. Chem Eng J Adv. 2023;14:100467. 10.1016/j.ceja.2023.100467.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Li H, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Huang H, Ou H, Zhang Y. In-situ adsorption-conversion recovery of heavy metal cadmium by natural clay mineral for multi-functional photocatalysis. Sep Purif Technol. 2023;319:124058. 10.1016/j.seppur.2023.124058.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Wu Y, Ming J, Zhou W, Xiao N, Cai J. Efficiency and mechanism in preparation and heavy metal cation/anion adsorption of amphoteric adsorbents modified from various plant straws. Sci Total Environ. 2023;884:163887. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.163887.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Peld M, Tõnsuaadu K, Bender V. Sorption and desorption of Cd2+ and Zn2+ ions in apatite-aqueous systems. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38:5626–31. 10.1021/es049831l.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Smičiklas I, Dimović S, Plećaš I, Mitrić M. Removal of Co2+ from aqueous solutions by hydroxyapatite. Water Res. 2006;40:2267–74. 10.1016/j.watres.2006.04.031.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Zhu R, Yu R, Yao J, Mao D, Xing C, Wang D. Removal of Cd2+ from aqueous solutions by hydroxyapatite. Catal Today. 2008;139:94–9. 10.1016/j.cattod.2008.08.011.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Chen J-H, Wang Y-J, Zhou D-M, Cui Y-X, Wang S-Q, Chen Y-C. Adsorption and desorption of Cu(II), Zn(II), Pb(II), and Cd(II) on the soils amended with nanoscale hydroxyapatite. Environ Prog Sustain Energy. 2010;29(2):233–41. 10.1002/ep.10371.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Zhang W, Wang F, Wang P, Lin L, Zhao Y, Zou P, et al. Facile synthesis of hydroxyapatite/yeast biomass composites and their adsorption behaviors for lead (II). J Colloid Interface Sci. 2016;477:181–90. 10.1016/j.jcis.2016.05.050.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Kede MLFM, Mavropoulos E, da Rocha NCC, Costa AM, Prado da Silva MH, Moreira JC, et al. Polymeric sponges coated with hydroxyapatite for metal immobilization. Surf Coat Technol. 2012;206:2810–6. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2011.11.044.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Chand P, Pakade YB. Synthesis and characterization of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles impregnated on apple pomace to enhanced adsorption of Pb(II), Cd(II), and Ni(II) ions from aqueous solution. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2015;22:10919. 10.1007/s11356-015-4276-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Itami K, Yanai J. Sorption and desorption properties of cadmium and copper on soil clays in relation to charge characteristics. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2006;52:5–12. 10.1111/j.1747-0765.2006.00015.x.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Helios Rybicka E, Calmano W, Breeger A. Heavy metals sorption/desorption on competing clay minerals: an experimental study. Appl Clay Sci. 1995;9:369–81. 10.1016/0169-1317(94)00030-T.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Quaghebeur M, Rengel Z, Rate AW, Hinz C. Heavy metals in the environment desorption kinetics of arsenate from kaolinite as influenced by pH. J Environ Qual. 2005;34:479–86.10.2134/jeq2005.0479aSearch in Google Scholar

[31] Ma F-Q, Zhu W-M, Cheng W-T, Chen J-Q, Gao J-Z, Xue Y, et al. Removal of cobalt ions (II) from simulated radioactive effluent by electrosorption on potassium hydroxide modified activated carbon fiber felt. J Water Process Eng. 2023;53:103635. 10.1016/j.jwpe.2023.103635.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Kyzas GZ, Deliyanni EA, Matis KA. Activated carbons produced by pyrolysis of waste potato peels: Cobalt ions removal by adsorption. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2016;490:74–83. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2015.11.038.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Silva PAP, Oréfice RL. Biosorbent from castor oil polyurethane foam containing cellulose-halloysite nanocomposite for removal of manganese, nickel and cobalt ions from water. J Hazard Mater. 2023;454:131433. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.131433.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Pereira NM, Brincoveanu O, Pantazi AG, Pereira CM, Araújo JP, Silva AF, et al. Electrodeposition of Co and Co composites with carbon nanotubes using choline chloride-based ionic liquids. Surf Coat Technol. 2017;324:451–62. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2017.06.002.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Chua Q-W, Liang J, Hao J-C. Electrodeposition of zinc-cobalt alloys from choline chloride–urea ionic liquid. Electrochim Acta. 2014;115:499–503. 10.1016/j.electacta.2013.10.204.Search in Google Scholar

[36] You Y-H, Gu C-D, Wang X-L, Tu J-P. Electrodeposition of Ni–Co alloys from a deep eutectic solvent. Surf Coat Technol. 2012;206:3632–8. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2012.03.001.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Gómez E, Cojocaru P, Magagnin L, Valles E. Electrodeposition of Co, Sm and SmCo from a Deep Eutectic Solvent. J Electroanal Chem. 2011;658:18–24. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2011.04.015.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Neha G, Atul K, Chattopadhyaya MC. Adsorption studies of cationic dyes onto Ashoka (Saraca asoca) leaf powder. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2012;43:604–13. 10.1016/j.jtice.2012.01.008.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Rabbat C, Pinna A, Andres Y, Villot A, Awad S. Adsorption of ibuprofen from aqueous solution onto a raw and steam-activated biochar derived from recycled textiles insulation panels at end-of-life: Kinetic, isotherm and fixed-bed experiments. J Water Process Eng. 2023;53:103830. 10.1016/j.jwpe.2023.103830.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Dou W-S, Deng Z-P, Fan J-P, Lin Q-Z, Wu Y-H, Ma Y-L, et al. Enhanced adsorption performance of La(III) and Y(III) on kaolinite by oxalic acid intercalation expansion method. Appl Clay Sci. 2022;229:106693. 10.1016/j.clay.2022.106693.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Abdel-Fadeel MA, Aljohani NS, Al-Mhyawi SR, Halawani RF, Aljuhani EH, Salam MA. A simple method for removal of toxic dyes such as Brilliant Green and Acid Red from the aquatic environment using Halloysite nanoclay. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2022;26:101475. 10.1016/j.jscs.2022.101475.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Aljohani NS, Kavil YN, Al-Farawati RK, Alelyani SS, Orif MI, Shaban YA, et al. The effective adsorption of arsenic from polluted water using modified Halloysite nanoclay. Arab J Chem. 2023;16:104652. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.104652.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Bui HB, Hoang N, Nguyen TTT, Le TD, Vo TH, Nguyen TD, et al. Performance evaluation of nanotubular halloysites from weathered pegmatites in removing heavy metals from water through novel artificial intelligence-based models and human-based optimization algorithm. Chemosphere. 2021;282:131012. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites