Abstract

This article provides information on the synthesis of esterified derivatives of hydrolyzed polyacrylonitrile (EPAN) based on the polymer waste “Nitron” for use as an encapsulating reagent. The elemental and structural compositions of potassium humate and the organic polymer were determined using a scanning electron microscope (Jeol JSM-6490l V) and an IR Fourier spectrometer (Zhimadzu IR Prestige-21). A method is presented for determining the strength of the encapsulated granules of potassium humates using an IPG-1M device and a TAXTplus texture analyzer (Stable Microsystems). The scientific novelty of the article lies in the synthesis of EPAN from “Nitron” polymer waste using sodium hydroxide in the presence of ethylene glycol at a temperature of 370 K for 4 h, followed by the use of 0.5% synthesized solution for encapsulating the granular potassium humate produced from humic acid to give a strength of up to 17.3 kg and prolonged action to the granules. The effect of EPAN concentration on the encapsulation process of granular potassium humates was investigated and studied. The mechanism for the formation of a protective layer of granular potassium humates in the form of a transparent film has been established. The results of the experimental work were processed using the integrated program Statistica-10, which showed a 3D simulation of the process. Microscopic, IR spectral, X-ray phase and thermogravimetric analyses of the encapsulated potassium humate were carried out using modern instrumental devices (MicroXRF Analysis Report, monochromator D878-PC75-17.0, TGA/DSC 1HT/319). The encapsulated durable potassium humate granules provide longer-term nutrition, i.e., a slow, gradual release of plant nutrients in the soil. The use of the produced high-strength encapsulated potassium humate granules allows for restoring soil fertility and increasing the yield of agricultural plants. The encapsulated granules can withstand numerous transshipments and long-term transportation while maintaining the commercial and consumer properties of the product.

1 Introduction

One of the promising types of fertilizers is slow-release fertilizers or fertilizers with controlled release of nutrients using water-soluble polymers. Water-soluble polymers (polyelectrolytes) have unique complex properties that depend on the concentration in the system; at low concentrations, they have a structure-forming effect, and in more concentrated solutions, they have a pronounced stabilizing effect. In addition, due to the successful combination of physicochemical properties of high-molecular compounds and surfactants, they are widely used in encapsulating mineral fertilizers for the agro-industrial complex [1,2].

The authors obtained materials containing various amounts of NPK as a mineral fertilizer, lignohumate as a source of organic carbon, and combinations thereof. This stability study focused on beneficial properties when applied to soil – repeated drying/reswelling cycles and possible winter freezing. Lignohumate supported water absorption, whereas the addition of NPK caused a negative effect. The pore size decreased with the addition of NPK. The introduction of lignohumate into polymers leads to the formation of a very diverse structure, rich in various pores and voids of various sizes [3]. The advantages of encapsulated organo-mineral fertilizers are presented. It is proposed to use the suspension of chicken manure as an organic shell [4].

Encapsulation is a physical–chemical or mechanical process of enclosing small particles of a substance in a shell of film-forming material. When encapsulating water-soluble mineral fertilizers, the granules are covered with protective films that have low permeability to aqueous solutions. The result is a kind of slow-acting encapsulated fertilizer [5,6].

Encapsulation technology comprises enclosing active agents (core materials) within a homogeneous/heterogeneous matrix (wall material) at the micro/nanoscale. In the last few years, encapsulation has gained a lot of interest. The encapsulation technology not only extends the availability of nutrients to crops by minimizing nutrient losses through leaching and volatilization but also modulates the release dynamics, potentially leading to enhanced nutrient uptake and crop productivity. The adoption of such encapsulated fertilizers could contribute to increased crop yields, reduced environmental pollution from fertilizer runoff, and decreased fertilization costs. Fertilizers are encapsulated with various compounds based on synthetic or natural polymers to be used as SRFs [7,8,9].

The use of water-soluble polymers (polyelectrolytes) in organomineral fertilizers promotes structure formation in the system, the formation of a polymer–fertilizer complex, and the preservation of digestible potassium humate in the composition of the fertilizer. In the future, using them will lead to the aggregation of soil aggregates; these aggregates will retain moisture, which will have a beneficial effect on maintaining soil moisture for a long time [10].

Potassium humate received the widest application in pre-sowing seed treatment and foliar feeding of plants during the growing season. Potassium humate is an organomineral fertilizer with a stimulating effect and fungicidal activity, and is a product of high-tech processing of lowland peat and coal. Humates are also formed naturally in the form of a salt of humic acid (HA) [11,12,13,14].

Encapsulation of granular products is used to improve their quality, improve presentation, and expand functionality. The authors studied the mechanical properties of mineral fertilizers. Mechanical properties include the static strength of mineral fertilizer granules. This article improves the static strength of potassium humate granules in the encapsulation process using esterified derivatives of hydrolyzed polyacrylonitrile (EPAN) [1,5,15].

As the effectiveness of the encapsulation may vary depending on soil conditions and crop-specific nutrient requirements, it is essential to consider these factors when implementing this technology. By tailoring the encapsulation system to the specific needs of different crops and soil environments, the potential benefits of EPAN/potassium humate encapsulated fertilizers can be maximized [16,17].

The scientific novelty of the article lies in the synthesis of EPAN from “Nitron” polymer waste using sodium hydroxide in the presence of ethylene glycol at a temperature of 370 K for 4 h, followed by the use of 0.5% synthesized solution for encapsulating the granular potassium humate produced from HA to give a strength of up to 17.3 kg and prolonged action to the granules.

Of particular practical importance is the strength of mineral fertilizer granules, which are able to withstand numerous transshipments and long-term transportation while maintaining the commercial and consumer properties of the product. Therefore, the production of durable granules of mineral fertilizers is an urgent task.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Organic polymer synthesis EPAN

PAN is a waste polymer fiber obtained from polyacrylonitrile (PAN) “Nitron”. PAN was placed in a 1,000 ml three-necked flask equipped with a stirrer, reflux condenser and addition funnel, and 35 ml of 42% aqueous sodium hydroxide solution was gradually added and heated to 223–228 K. During this period, no change in color or release of ammonia was observed. When the temperature increased to 333–343 K, it was accompanied by the coloring of not the entire reaction mass but only the polymer particles themselves in yellow.

In the course of the hydrolysis process, the release of ammonia increased gradually, and no rapid release of ammonia from the reaction mixture was observed. After 60 min, the dispersed polymer particles changed color from yellow to red-orange and finally to red-brown, indicating hydration, cyclization of nitrile groups and defunctionalization to the amide group. Then, 10 g of ethylene glycol was added to the reaction mixture [18,19].

The saponification process was carried out at a temperature of 370 K for 4 h. The saponification process proceeded with a rapid release of ammonia and the formation of amide groups due to the cyclization of nitrile groups, while the formed amide and carboxyl groups interacted with ethylene glycol according to the Mannich reaction:

2.2 Methods for determination and encapsulation of potassium humate

A scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Jeol JSM-6490l V), thermogravimetric analyzer TGA/DSC 1HT/319 (Mettler Toledo), X-ray phase analysis using an incident beam monochromator D878-PC75-17.0 (London, England) MicroXRF Analysis Report and an IR Fourier spectrometer (Shimadzu IR Prestige-21) were used to obtain encapsulated potassium humate. The elemental composition and microstructure of potassium humate were determined using an electron scanning microscope JSM-6490lV (Jeol, Japan) by the energy-dispersive method. The essence of the electron microscopy method is that an electron beam of different energies is fed through the sample under study. Under the influence of an electromagnetic field, it is focused on the surface in the form of a spot with a diameter not exceeding 5 nm. As a result, the elemental composition and microstructure of the sample under study are recorded. The sensitivity of the method for an individual component is 0.1 wt%, and the range of elements being determined is from beryllium (B) to uranium (U). The spectra were obtained in the range 0–20 keV. The voltage at the accelerating electrode was 15 kV.

To obtain encapsulated fertilizers, the obtained potassium humate was soaked in a 0.25–0.75% solution of water-soluble organic polymers, further dried at 25–100°C and granulated in a plate granulator. The EPAN were used as water-soluble polymers.

2.3 Determination of static strength and the study of granule structures

The measurement of the static strength of sample granules was carried out on an IPG-1M device (fracture force: up to 200 N, punch speed: 0.8–1.2 mm·s−1). In addition, the static strength of the granules was determined using a TAXTplus texture analyzer (Stable Microsystems, UK). This device allows one to vary the load feed rate from 0.01 to 40 mm·s−1 and has a force resolution of 0.001 N. The static strength was determined for 40 granules (according to the method, 20 granules are enough) of the 3.0–3.15 mm and 3.0–3.35 mm fractions.

The structure of the granules was studied using an SEM JSM-6490l V (Jeol, Japan). The distribution of chemical elements over the surface of chipped granules was determined by X-ray fluorescence microanalysis using an EDS attachment Quantax 70 (Bruker). Accumulation of spectra was carried out in the range (0–20) keV. The voltage at the accelerating electrode was 15 kV. The sensitivity of the method for an individual component is 0.1 wt%.

3 Results

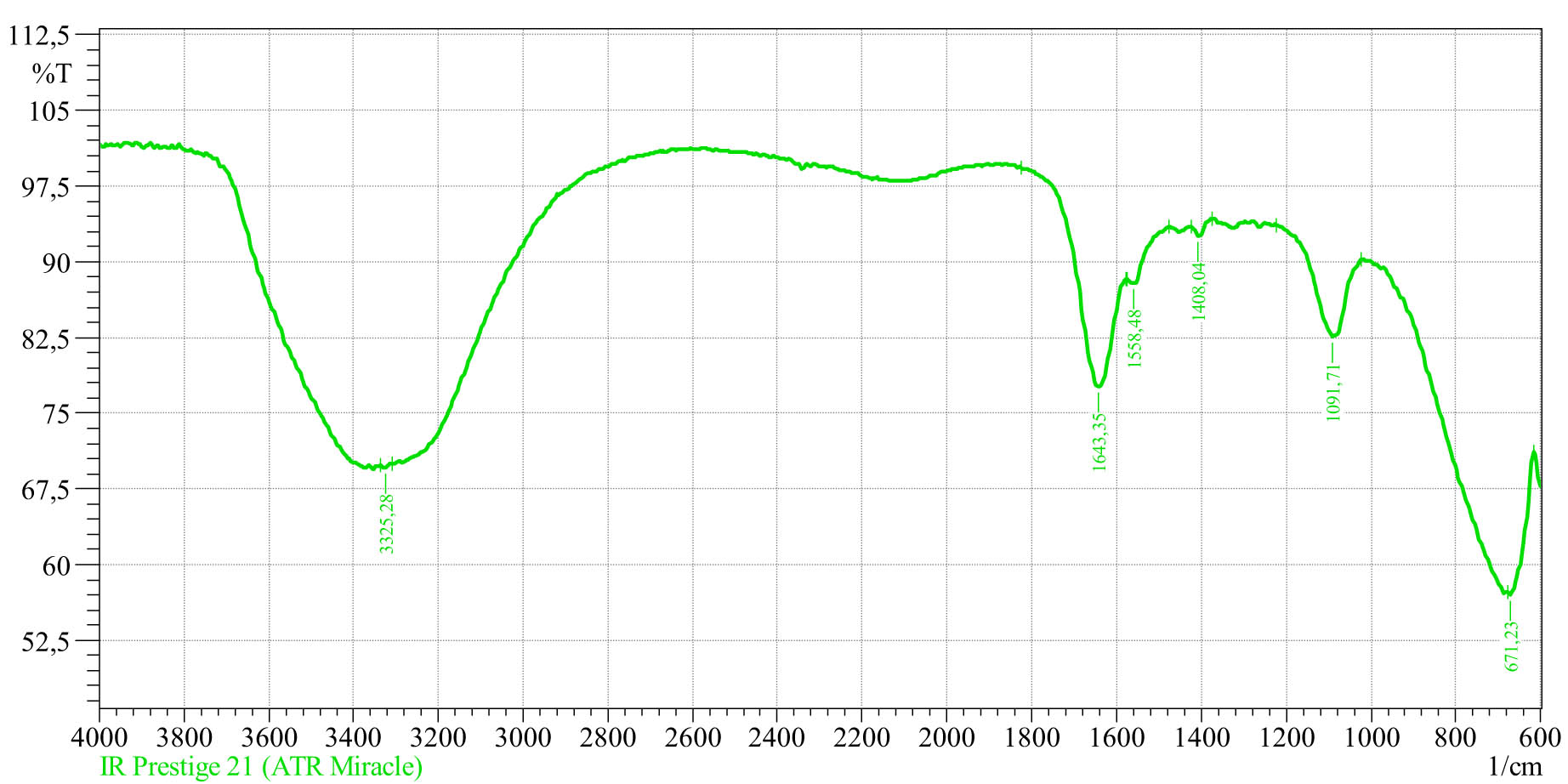

The obtained esterified hydrolyzed polyacrylonitrile had the following functional groups during research. The EPAN was analyzed in an IR spectrometer (Shimadzu IR Prestige-21), and the results of the studies are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Spectral data of the organic polymer EPAN

| No | Peak | Intensity | Corr. intensity | Base (H) | Base (L) | Area | Corr. area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 671.23 | 56.946 | 2.091 | 678.94 | 617.22 | 12.867 | 1.025 |

| 2 | 1,091.71 | 82.583 | 8.866 | 1,222.87 | 1,022.27 | 10.666 | 3.326 |

| 3 | 1,408.04 | 92.574 | 1.177 | 1,423.47 | 1,373.32 | 1.494 | 0.121 |

| 4 | 1,558.48 | 87.894 | 1.208 | 1,573.91 | 1,477.47 | 3.956 | 0.133 |

| 5 | 1,643.35 | 77.612 | 13.664 | 1,824.66 | 1,577.77 | 11.761 | 5.127 |

| 6 | 3,325.28 | 69.651 | 0.255 | 3,336.85 | 3,309.85 | 4.214 | 0.021 |

The IR spectrum of EPAN.

Figure 1 shows the following IR absorption spectra:

Intervals of 3,325.28 cm−1 of intense absorption correspond to compounds between carboxylic acids with –OH–groups and methyl and methylene groups.

Intense absorption of 1,643–1,558.48 cm−1 corresponds to the compounds carbonyl and amide hydrocarbons.

Non-intensive absorption values of 1,408.04 cm−1 are typical of aromatic aldehydes in carboxyl hydrocarbon compounds that form an oxygen bridge with potassium metal C–O–Na.

Intensive absorption of 1,091.71 cm−1 is characteristic of compounds of aromatic aldehyde hydrocarbons forming the C–O–C oxygen bridge.

Values of intense spectral of 671.23 cm−1 correspond to organic thiophene compounds.

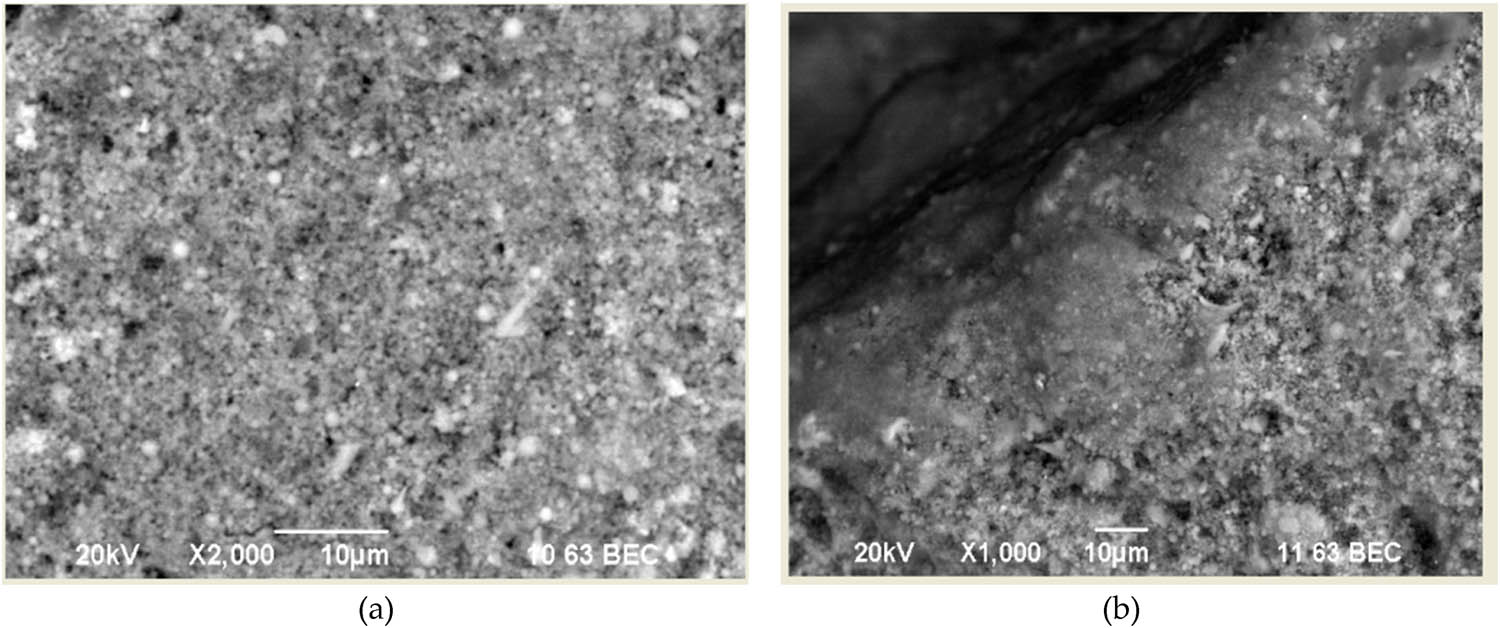

Potassium humate was obtained on the basis of HA obtained according to GOST 9517-94, ISO 5073-85 from coal waste of the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan. The elemental composition and microscopic image of the resulting potassium humate were determined using scanning microscopy (JSM-6490lV, Jeol. Tokyo, Japan). The results of the experimental work are shown in Figure 2 and Table 2.

Microscopic image of potassium humate before encapsulation.

Elemental composition of potassium humate

| Element | Weight (%) | Oxides | In terms of oxides (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | 58.2 | — | — |

| O | 22.4 | — | — |

| K | 19.4 | К2O | 23.4 |

Figure 2 shows that the microstructure of potassium humate has a mainly amorphous structure with the addition of potassium since potassium combines with the functional groups of HAs. The scale of this microstructure is x40 times the increase from the actual state (600 μm, spectral range: 0–20 keV).

Figure 2 shows the results of microscopic studies of potassium humate, carried out using an SEM JSM-6490l using the energy-dispersive method in the form of yellow spectra. These yellow spectra respectively indicate the elements that are present in a given sample and their mass fraction in ratio%. Based on these data, the elemental composition of the test sample is determined and converted to the oxide form.

Table 2 shows that the carbon content is 58.2% and the potassium content is 19.4%. Such a content of useful components of potassium humate is enough to use it as a humate-containing fertilizer to increase crop yields [20,21].

The obtained potassium humate was analyzed using an IR spectrometer (Shimadzu IRPrestige-21), and the results are shown in Figure 3.

The IR spectrum of potassium humate.

Figure 3 shows the following IR absorption spectra:

Intervals of 3,400–3,200 cm−1 of non-intense absorption correspond to compounds between carboxylic acids with –OH-groups and methyl and methylene groups.

Values of intensive absorption of 1,800–1,600−cm−1 correspond to compounds of carbonyl aromatic hydrocarbons.

Intensive absorption values of 1,257.91 cm−1 are typical for aromatic aldehyde in carboxyl hydrocarbon compounds that form an oxygen bridge with potassium metal C–O–K.

Values of intense spectral absorption of 800–600 cm−1 correspond to organic thiophene compounds.

Values of intense spectral absorption of 600–550 cm−1 correspond to organic methylene compounds.

Based on the results of the studies, it was determined that during encapsulation, an increase in the concentration of the EPAN and the process temperature positively affect the strength of the granules. This is evidenced by numerous experimental works on the encapsulation of mineral fertilizers. In the encapsulation process, the concentration of the organic polymer EPAN plays the main role in the strength of granular potassium humate, and the temperature of the process plays an auxiliary role. Therefore, the focus is on the concentration of organic polymer. The process of encapsulation of potassium humate using the EPAN organic polymer shows similar results as previously published works.

In the process of encapsulation of potassium humate at a temperature change from 25°C to 100°C, without EPAN, the static strength of potassium humate granules reaches from 0 to 1.81 kg. An increase in the temperature in the range of 75–100°C leads to the strengthening of the initial structure of the granules.

Figure 4a shows the microstructure of encapsulated granular potassium humate at 75°C in the presence of 0.25% EPAN. At this concentration, the structure formation of the system – potassium humate – occurs; that is, it turns into a fine-grained amorphous structure. The microstructure of the cut capsule is shown in Figure 4b, from which it follows that the concentration of the organic polymer is insufficient to form a protective layer of the capsule. The static strength of the granules increases from 2.65 to 15.8 kg. Furthermore, increase in the temperature to 100°C reduces the strength of potassium humate granules. This is due to the lack of concentration of the EPAN.

Microstructure (a) and a cut of sample (b) of the encapsulated and potassium humate at 75°C in the presence of 0.25% of EPAN water solution.

With a change in temperature from 25°C to 75°C, at a 0.5% concentration of organic polymer, the static strength of potassium humate granules reaches 2.88 to 17.3 kg. Figure 5a shows the microstructure of encapsulated granular potassium humate at 75°C in the presence of 0.5% EPAN. An increase in the concentration of organic polymer in the system leads to a change in the structure of the fertilizer; that is, net and uneven lattice-like shapes appear in the structure of potassium humate.

Microstructure (a) and a cut of sample (b) of the encapsulated and granulated potassium humate at 75°C in the presence of 0.5% EPAN water solution.

The appearance of fragments in the structure of the fertilizer is apparently associated with the aggregation of fertilizer particles and the further formation of large, interconnected aggregates due to the adsorption properties and functional groups of organic polymers, which are responsible for the strength properties of the structure of the entire system. All this leads to the formation of an amorphous structure with the appearance of a crystalline one.

Figure 5b shows a section of the upper part of the encapsulated granule, from which it is clear that the polyelectrolyte not only has the binding and structural properties of the internal part of the granule structure but also the encapsulating effect of the upper layer. In this case, there is an accumulation of binding components in the upper part of the granules (Figure 5b), apparently an increase in the concentration of the structural polymer, which leads to the initial formation of a thin film on the surface of the granules.

With a change in temperature from 25°C to 75°C, at 0.75% concentration of the organic polymer, the static strength of potassium humate granules reaches 5.36 to 12.4 kg (Figure 6a and b).

Microstructure (a) and a cut of the sample (b) of the encapsulated and granulated potassium humate at 75°C in the presence of 0.75% EPAN water solution.

For reliability of the obtained results on the mechanism of capsulation and comparative analysis, a microstructure of a sample of complex polymer containing fertilizer–potassium humate based on the encapsulated 0.5% EPAN solution at 75°C is shown in Figure 7.

Microstructure of the sample of a complex polymer containing fertilizer of potassium humate, which is dried at 75°C: (a) superficial and (b) a reverse side.

Figure 7 shows that the complex polymer containing the fertilizer potassium humate also strengthens the structure of the fertilizer. Apparently, aggregation of small particles occurs due to the interaction of functional groups with the active centers of the mineral fertilizer. In addition, they form a thin film on the surface of the particles of fertilizers.

At this stage, due to the increase in the concentration, a protective film is formed around the granules, and a strong capsule layer appears due to the organic functional groups of the EPAN. This layer has a stable shape and provides strength to the granules. The resulting capsule layer has a positive effect on potassium humate granules and increases the static strength of the granules but does not exceed the strength of the previous experiments. With an increase in the concentration, the viscosity of the organic polymer increases, and further increase is not profitable; that is, the consumption of the polymer increases, while the strength of the granules does not increase.

The results of research on the influence of EPAN concentration and temperature on the strength of potassium humate in the process of capsulation by EPAN are presented in Table 3.

Influence of organic polymer concentration and temperature on the strength of granules

| Capsulation mode | Temperature (°C) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 50 | 75 | 100 | |

| Before capsulation | ||||

| Static strength of granules (kg) | 0 | 0 | 1.0 | 1.81 |

| Capsulation with 0.25% EPAN solution | ||||

| Static strength of granules (kg) | 2.65 | 5.54 | 15.3 | 2.96 |

| Capsulation with 0.5% EPAN solution | ||||

| Static strength of granules (kg) | 2.88 | 7.86 | 17.3 | 2.44 |

| Capsulation with 0.75% EPAN solution | ||||

| Static strength of granules (kg) | 5.36 | 7.42 | 12.4 | 3.23 |

As shown in Table 3, it is evident that with an increase in the concentration of EPAN from 0% to 0.5%, the static strength of encapsulated granular potassium humate increases from 1.0 to 17.3 kg at a temperature of 75°C. The table data were processed and are shown in Figure 8.

Dependence of static strength of granules on the concentration EPAN and temperature.

From Figure 8, it can be seen that the maximum static strength (17.3 kg) is achieved at a concentration of 0.5% EPAN at a temperature of 75°C. Based on the results of numerous experimental works, it was determined that the optimal process temperature is 75°C.

The influence of technological parameters during the encapsulation of potassium humate using the EPAN was processed using the Statistica-10 complex programs, and a 3D (three-dimensional) simulation is shown in Figure 9.

Influence of technological parameters during the encapsulation of potassium humate using the EPAN.

From Figure 9, it follows that the increase in the strength of potassium humate granules under the influence of concentration and temperature during the encapsulation process using the EPAN is characterized by a change in the square shape of the plane from green to saturated red.

The elemental, mineralogical composition and micrograph of encapsulated potassium humate were determined using a Microsoft Analysis Report (Figure 10, Table 4). According to the results of the studies, it was determined that an increase in the concentration of EPAN leads to the formation of a gel-like structure (in the form of an encapsulating layer) in the upper part of the granules and to the formation of thin films, which ensures the strength properties of the granules.

The micrograph of encapsulated potassium humate.

Elemental composition of encapsulated potassium humate

| Element | Weight (%) | Oxides | In terms of oxides (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | 56.4 | — | — |

| O | 21.1 | — | — |

| K | 19.2 | К2O | 20.4 |

| Na | 1.20 | Na2O | 1.61 |

| N | 2.10 | — | — |

Figure 10 shows that the microstructure of encapsulated potassium humate occurs through the aggregation of small particles due to the interaction of functional groups with the active centers of the fertilizer. In addition, they form a thin film on the surface of fertilizer particles.

It was also found that the strength of mineral fertilizers depends not only on the concentration of the EPAN but also on the chemical composition of mineral fertilizers and the parameters of the mineral fertilizer granulation process before encapsulation. When encapsulated with EPAN under optimal conditions, each mineral fertilizer has different hardness values and always differs from other types of fertilizers.

From Table 4, it follows that the concentrations of humate-containing components in the encapsulated fertilizer’s composition are C – 56.4% and O – 21.1%, and concentrations of macro elements are K – 19.2% and N –2 .10%. Such a content of useful components is sufficient to use as an encapsulated organomineral fertilizer to increase the yield of agricultural crops.

To study the change in the encapsulated potassium humate depending on time and temperature, a thermogravimetric analysis of the dust was carried out using a TGA/DSC 1HT/319 analyzer. The results of the analysis are shown in Figure 11.

Thermogravimetric analysis of encapsulated potassium humate.

As shown in Figure 11, the mass of the cottrel dust depends on time and temperature. This is evidenced by the changes in its mass at different temperatures: (1) 220.32°C – 86.6429 mg; (2) 673.22°C – 42.9686 mg; (3) 991.22°C – 31.4012 mg. According to the thermogravimetric analysis results, it was found that the encapsulated potassium humate mass loss in the temperature interval of 31.4012–991.22°C within 72 min is 68.9308 mg.

The loss of a large mass (68.7%) of the encapsulated potassium humate is explained by the fact that the composition contains hydrocarbon and polymer-containing compounds. With increasing temperature, hydrocarbon compounds are burnt, and polymer-containing compounds are restructured.

To determine the structural state and chemical phase composition of encapsulated potassium humate, an X-ray phase analysis was carried out using an incident beam monochromator D878-PC75-17.0 (London, England). The results are shown in Figure 12.

X-ray images of encapsulated potassium humate.

As shown in Figure 12, the analysis of the X-ray pattern shows that the structure of the test sample is amorphous. Diffraction peaks with values of interplanar distances A 0 = 7.82–3.38–2.12–2.02–1.68 indicate the presence of carbon C in the crystal structure of the sample, which is the main component. The composition of the test sample contains insignificant quantities: potassium oxide (K2O), with diffraction maxima A 0 = 6.32–3.77–2.56–2.21–2.08–1.66–1.48, and sodium oxide (Na2O), for which the diffraction maxima A 0 = 3.34–3.02–2.70–2.12–1.61, are characteristic. The presence of nitrogen is evidenced by diffraction peaks with low intensity: A 0 = 2.08–1.63–1.48.

The infrared spectral analysis of encapsulated potassium humate (Table 5 and Figure 12) was carried out using an IR Fourier spectrometer (Shimadzu IR Prestige-21) with a frustrated total internal reflection device, Miracle (Pike Technologies Kyoto, Japan). The IR Prestige-21 uses a bright ceramic light source, a high-sensitivity DLATGS detector, and high-throughput optical elements. Optimization of optical/electronics/signal systems minimizes noise and maximizes the S/N ratio (40,000:1 and better).

Spectral data of encapsulated potassium humate

| No | Peak | Intensity | Corr. intensity | Base (H) | Base (L) | Area | Corr. area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 462.92 | 92.782 | 10.742 | 470.63 | 455.20 | 0.163 | 0.389 |

| 2 | 555.50 | 76.504 | 6.170 | 567.07 | 513.07 | 3.978 | 1.086 |

| 3 | 597.93 | 67.153 | 7.991 | 617.22 | 570.93 | 6.612 | 1.064 |

| 4 | 667.37 | 58.651 | 15.294 | 964.41 | 621.08 | 49.086 | 16.203 |

| 5 | 991.41 | 89.280 | 0.728 | 1,006.84 | 968.27 | 1.820 | 0.066 |

| 6 | 1,041.56 | 87.049 | 0.792 | 1,049.28 | 1,010.70 | 2.079 | 0.074 |

| 7 | 1,095.57 | 84.785 | 4.625 | 1,176.58 | 1,064.71 | 5.709 | 1.118 |

| 8 | 1,284.59 | 94.345 | 0.067 | 1,288.45 | 1,226.73 | 1.444 | 0.004 |

| 9 | 1,354.03 | 92.359 | 0.118 | 1,357.89 | 1,292.31 | 1.959 | 0.022 |

| 10 | 1,404.18 | 90.552 | 2.094 | 1,435.04 | 1,377.17 | 2.188 | 0.268 |

| 11 | 1,446.61 | 93.037 | 0.262 | 1,438.90 | 1,438.90 | 1.155 | 0.030 |

| 12 | 1,558.48 | 87.809 | 1.934 | 1,577.77 | 1,481.33 | 3.841 | 0.238 |

| 13 | 1,643.35 | 79.006 | 13.184 | 1,782.23 | 1,581.63 | 9.823 | 4.626 |

| 14 | 3,278.99 | 69.264 | 0.553 | 3,286.70 | 2,885.51 | 31.402 | 1.195 |

| 15 | 3,317.56 | 68.673 | 0.221 | 3,325.28 | 3,298.28 | 4.372 | 0.022 |

| 16 | 3,352.28 | 68.324 | 1.315 | 3,753.48 | 3,340.71 | 34.944 | 3.823 |

Figure 13 shows the following IR absorption spectra:

Intervals of 3,400–3,200 cm−1 (3,352.28, 3,317.56, 3,278.99) of intense absorption correspond to compounds between carboxylic acids with –OH-groups and methyl, methylene groups.

Intense absorption values of 1,643–1,558.48 cm−1 correspond to the compounds of carbonyl and amide hydrocarbons.

Non-intensive absorption values of 1,446–1,404.18 cm−1 are typical for aromatic aldehyde in carboxyl hydrocarbon compounds that form an oxygen bridge with sodium metal C–O–Na.

Non-intensive absorption values of 1,354–1,284.59 cm−1 are typical for aromatic aldehyde in carboxyl hydrocarbon compounds that form an oxygen bridge with potassium metal C–O–K.

Values of intense spectral absorption of 1,095.57–1,041.56 cm−1, characteristic of compounds of aromatic aldehyde hydrocarbons, forming the C–O–C oxygen bridge.

Intensive absorption of 991.56 cm−1, characteristic of compounds of polyacrylamide –CONH2 functional groups.

Values of intense spectral absorption of 700–600 cm−1 correspond to organic thiophene compounds.

Values of intense spectral absorption of 600–450 cm−1 correspond to organic methylene compounds.

The IR spectrum of encapsulated potassium humate.

4 Discussion

The work focuses on the evaluation of a new slow-release fertilizer encapsulated by a combination of carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) and HA. The purpose of this study was to study the release of essential plant nutrients: phosphorus, nitrogen, and potassium. This study investigated the material composition and nutrient release properties of a novel prolonged-action fertilizer encapsulated by CMC and HA [22].

The strength of conventional mineral fertilizers ranges from 2.0 to 3.5 kg·(MPa·(kgf·cm−2)). The resulting encapsulated potassium humate differs from modern analogues in that it has high strength characteristics and durability. The encapsulated potassium humate’s strength is 17.3 kg. High strength has a positive effect on maintaining its granulometric composition and prolonged action [23].

Encapsulated durable potassium humate granules provide longer-term nutrition, that is, a slow, gradual release of plant nutrients into the soil. Also, the improved mechanical properties of potassium humate have a positive effect on the efficiency of fertilizing. Thus, due to its greater strength, there is no dusting effect during use; it is better stored and is suitable for long-term storage. Due to the fact that the granules are more durable, they are less susceptible to caking and crumbling.

5 Conclusions

EPAN was synthesized based on the polymer waste Nitron in the process of saponification using sodium hydroxide with the addition of ethylene glycol for use as an encapsulating reagent. A method has been developed for encapsulating granular organomineral fertilizer potassium humate using the synthesized EPAN. The elemental and structural composition of potassium humate, organic polymer EPAN, and encapsulated potassium humate were determined using modern instrumental equipment. The effect of EPAN concentration on the encapsulation process of granular potassium humates was investigated and studied. The mechanism for the formation of a protective layer of granular potassium humates in the form of a transparent film has been established. The results of the experimental work were processed using the integrated program Statistica-10, which showed a 3D simulation of the process.

The thermogravimetric analysis was carried out using a TGA/DSC 1HT/319 analyzer, and the process of changing the encapsulated potassium humate’s mass with time and temperature was studied. It was found that the encapsulated potassium humate at high temperatures loses most of its mass (68.7%) because the composition includes hydrocarbon and polymer-containing compounds.

The strength of the resulting encapsulated potassium humate was studied using an IPG-1M device and a TAXTplus texture analyzer. It was found that the highest strength of the granules is 17.3 kg in the case of using 0.5% EPAN and at a temperature of 75°C.

The elemental analysis was implemented using a Microsoft Analysis Report, and the elemental composition of the encapsulated potassium humate was determined. It was found that the encapsulated potassium humate contains a sufficient amount of useful components (C – 56.4%, K – 19.2%, N – 2.10%) for its use as an organomineral fertilizer.

The X-ray phase analysis was carried out using an incident radiation monochromator D878-PC75-17.0 to determine the structural state and chemical phase composition of encapsulated potassium humate. The developed encapsulated potassium humates with high-strength characteristics restore soil fertility and increase the yield of agricultural plants [23].

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the management of the laboratories of the regional testing center “Structural and Biochemical Materials” at the M. Auezov SKU for their assistance in the research. Based on the research results, a patent for a utility model was obtained on the topic “Method for obtaining encapsulated mineral fertilizer” No. 8347 dated 08/11/2023 of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

-

Funding information: This research was funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Grant No. AP14972664.

-

Author contributions: Bakyt Smailov: investigation, data writing – original draft preparation, writing – review and editing, and funding acquisition. Usha Aravind: conceptualization, validation, and project administration. Almagul Kadirbayeva: formal analysis and methodology. Nursulu Sarypbekova: resources, software, and visualization. Abdugani Azimov: validation, software, and supervision. Nurpeis Issabayev: supervision and visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Beysenbayev OК, Ahmedov UK, Issa AB, Smailov BM, Esirkepova MM, Artykova ZHK. Receiving and research of the mechanism of capsulation of superphosphate and double superphosphate for giving of strength properties. N Natl Acad Sci Repub Kazakhstan. 2019;6:36–45. 10.32014/2019.2518-170X.153.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Dzhakipbekova N, Sakibayeva S, Dzhakipbekov E, Ahmet D, Rzabay S, Issa A, et al. The study of physical and chemical properties of the water-soluble polymer reagents and their application as an ointment. Orient J Chem. 2018;34(4):1779–86. 10.13005/ojc/3404010.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Romana K, Milan K, Marcela S, Petr S, Miloslav P, Elke B, et al. Functional hydrogels for agricultural application. Gels. 2023;9(7):590. 10.3390/gels9070590.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Ruslan O, Mykola Y, Olha L, Andrii L. Production of encapsulated organo-mineral fertilizers in a fluidized bed granulator. Acta Mech Slov. 2020;24(2):50–5. 10.21496/ams.2020.031.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Lipin AG, Nebukin VO, Lipin AA. Encapsulation of granules in polymer shells as a method for creating mineral fertilizers with a controlled rate of nutrient release. Mod High Technol. 2017;3(51):84–90. 10.6060/ivkkt201962fp.5793.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Ostroha R, Yukhymenko M, Lytvynenko O, Lytvynenko A. Production of encapsulated organomineral fertilizers in a fluidized bed granulator. Acta Mech Slov. 2020;24(2):50–5. 10.21496/ams.2020.031.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Aboudzadeh MA, Hamzehlou S. Special issue on function of polymers in encapsulation process. Polymers. 2022;14(6):1178. 10.3390/polym14061178.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Abd El-Aziz M, Salama D, Morsi S, Youssef A, El-Sakhawy M. Development of polymer composites and encapsulation technology for slow-release fertilizers. Rev Chem Eng. 2022;38(5):603–16. 10.1515/revce-2020-0044.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Timilsena Y, Haque M, Adhikari B. Encapsulation in the food industry: A brief historical overview to recent developments. Food Nutr Sci. 2020;11:481–508. 10.4236/fns.2020.116035.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Dzhakipbekova E, Sakibayeva S, Dzhakipbekov N, Tarlanova B, Sagitova G, Shingisbayeva Z. et al. The study of physical and chemical properties of water-soluble polymer reagents and their compatibility with antibiotics. Rasayan J Chem. 2020;13(3):1417–23.10.31788/RJC.2020.1325709Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Smailov BM, Zharkinbekov MA, Tuleshova KT, Issabayev NN, Tleuov AS, Beisenbayev OK, et al. Kinetic research and mathematical planning on the obtaining of potassium humate from brown coal of the Lenger deposit. Rasayan J Chem. 2021;14(3):1899–905. 10.31788/RJC.2021.1436391.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Nazarbek U, Abdurazova P, Nazarbekova S, Assylbekova D, Kambatyrov M, and Raiymbekov Y. Alkaline extraction of organic and mineral potassium humate from coal mining waste. Appl Sci. 2022;12(7):36–58. 10.3390/app12073658.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Ampong K, Thilakaranthna MS, Gorim LY. Understanding the role of humic acids on crop performance and soil health. Front Agron. 2022;4:848621. 10.3389/fagro.2022.848621.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Gong G, Xu L, Zhang Y, Liu W, Wang M, Zhao Y, et al. Extraction of Fulvic Acid from Lignite and Characterization of Its Functional Groups. Am Chem Soc Omega. 2020;5(43):27953–61. 10.1021/acsomega.0c03388.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Smailov BM, Beisenbayev OK, Tleuov AS, Kadirbaeva AA, Zakirov BS, Mirzoyev B. Production of chelate polymer-containing microfertilizers based on humic acid and ammophos. Rasayan J Chem. 2020;13(3):1372–8. 10.31788/RJC.2020.1335726.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Jarosiewicz A, Tomaszewska M. Controlled release NPK fertilizer encapsulated by polymeric membranes. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51(2):413–7. 10.1021/jf0208000.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Smailov BM, Aravind U, Zakirov BS, Azimov AM, Tleuov AS, Beisenbayev OK, et al. Technology for obtaining chelated organic and mineral microfertilizers based on humate-containing components. Rasayan J Chem. 2023;16(1):428–33. 10.31788/RJC.2023.1618007.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Artykova ZK, Beisenbayev OK, Kadyrov AA, Sakibayeva SA, Smailov BM. Synthesis and preparation of polyacrylonitrile and vinyl sulfonic acid in the presence of gossypol resin for drilling fluids. Rasayan J Chem. 2023;16(4):2313–20. 10.31788/RJC.2023.1618497.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Issa AB, Beisenbayev OK, Akhmedov UK, Smailov BM, Yessirkepova BM, Kydyraliyeva AS, et al. Polymeric compositions to increase oil recovery. Rasayan J Chem. 2023;16(2):876–83. 10.31788/RJC.2023.1628295.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Smailov BM, Usha A. Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan. Green Process Synth. 2024;13:20230150. 10.1515/gps-2023-0150.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Beysenbayev OK, Tleuov AS, Smailov BM, Zakirov BS. Obtaining andresearch of physical and chemical properties of chelated polymer-containing microfertilizers on the basis of technogenic waste forrice seed biofortification. N Natl Acad Sci Repub Kazakhstan. 2019;438:80–9. 10.32014/2019.2518-170X.10.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Ulzhalgas N, Saule N, Yerkebulan R, Maksat K, Perizat A. Prolonged action fertilizer encapsulated by CMC. e-Polymers. 2023;23:20230013. 10.1515/epoly-2023-0013.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Smaylov BM, Satayev SA, Khalmetov UM. Method for obtaining encapsulated mineral fertilizer. Patent for utility model. RSE «National institute of intellectual property» RK №8347. 2023. https://gosreestr.kazpatent.kz/. (accessed August 11, 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”