Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

-

Muhammad Ammar Javed

, Sikander Ali

, Khaloud Mohammed Alarjani

Abstract

This research work aims to synthesize environmentally benign and cost-effective metal nanoparticles. In this current research scenario, the leaf extract of Cedrela toona was used as a reducing agent to biosynthesize silver nanoparticles (AgNPs). The synthesis of AgNPs was confirmed by the color shift of the reaction mixture, i.e., silver nitrate and plant extract, from yellow to dark brown colloidal suspension and was established by UV-visible analysis showing a surface plasmon resonance band at 434 nm. Different experimental factors were optimized for the formation and stability of AgNPs, and the optimum conditions were found to be 1 mM AgNO3 concentration, a 1:9 ratio of extract/precursor, and an incubation temperature of 70°C for 4 h. The Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy spectra indicated the presence of phytochemicals in the leaf extract that played the role of bioreducing agents in forming AgNPs. X-ray diffraction patterns confirmed the presence of AgNPs with a mean size of 25.9 nm. The size distribution and morphology of AgNPs were investigated by scanning electron microscopy, which clearly highlighted spherical nanoparticles with a size distribution of 22–30 nm with a mean average size of 25.5 nm. Moreover, prominent antibacterial activity was found against Enterococcus faecalis (21 ± 0.5 mm), Bacillus subtilis (20 ± 0.9 mm), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (18 ± 0.3 mm), Staphylococcus aureus (16 ± 0.7 mm), Klebsiella pneumoniae (16 ± 0.3 mm), and Escherichia coli (14 ± 0.7 mm). In addition, antioxidant activity was determined by DPPH and ABTS assays. Higher antioxidant activity was reported in AgNPs compared to the plant extract in both DPPH (IC50 = 69.62 µg·ml−1) and ABTS assays (IC50 = 47.90 µg·ml−1). Furthermore, cytotoxic activity was also investigated by the MTT assay against MCF-7 cells, and IC50 was found to be 32.55 ± 0.05 µg·ml−1. The crux of this research is that AgNPs synthesized from the Cedrela toona leaf extract could be employed as antibacterial, antioxidant, and anticancer agents for the treatment of bacterial, free radical-oriented, and cancerous diseases.

1 Introduction

We have set foot into an epoch of the notion “The smaller, the better.” Nano broaches to things that are smaller than the smallest. Therefore, in the bare-bone version of the definition, “The exploration and exploitation of structures between 1 nanometer (nm) and 100 nanometers in size are referred to as nanotechnology” [1]. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) have managed a vast space in the family of nanoparticles because of their diverse applications in the fields of medicine, food, textile, health, and agriculture. Moreover, AgNPs have emerged as an efficacious antibacterial agent and can even show their activity against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Therefore, there is a need to widen the implication of Ag nanoparticles as antibacterial agents. These properties are attributed to AgNPs because of their crystallographic surface structure and stupendous surface-to-volume ratios. They enter the cell walls of bacteria and make “pits,” which lead to the death of the cell. The concentration, shape, and size of the AgNPs decide the extent of their antibacterial activity [2,3].

Oxidative stress is the phenomenon that is induced when the equilibrium between oxidants and the antioxidant defense of a cell is disturbed, usually by the increase in the concentration of oxidants like reactive oxygen species (ROS) or reactive nitrogen species. The appearance of these oxidants could cause oxidative modifications in the biological system at the molecular level (DNA, proteins, lipids, etc.), leading to cell death [4]. Oxidants could change the membrane permeability by the production of peroxides or aldehydes and oxidation of double bonds of polyunsaturated fatty acids in lipids. Their stress on proteins can cause modifications in enzymatic activity, protein inactivation, and changes in ion transport. They can damage the DNA by inhibition of proteosynthesis, translational errors, and base modification, resulting in mutations or deoxyribose ring cleavage [5]. Considering the aforementioned changes, a connection can be developed between oxidative stress and various diseases like cancer, cardiovascular diseases, atherosclerosis, schizophrenia, or Alzheimer’s disease [6,7]. Therefore, there is a need to tackle the overproduction of ROS through the integration of antioxidant compounds. Besides the applications of AgNPs in various fields, they also serve as an antioxidant agent. The simple synthesis, easy availability, and cost-effective approach of AgNPs have replaced the need for other antioxidant compounds. They could act as catalysts for the polyphenols that serve as antioxidant agents [8] or could simultaneously work as antioxidant agents with compounds like phytochemicals (flavonoids) through single hydrogen and electron transfer [9]. The presence of flavonoids, phenolic compounds, and terpenoids allows the AgNPs to exhibit antioxidant activity as a singlet oxygen quencher, reducing agent, or hydrogen donor [10]. Moreover, the greater the degree of hydroxylation in phenolic compounds, the higher the radical scavenging capacity of the AgNPs [11].

AgNPs also exhibit cytotoxic potential against cancer cell lines. Their cytotoxic behavior depends upon their shape and size. For instance, the anticancerous effect against the human lung epithelial A549 cells was shown by spherical Ag nanoparticles (30 nm) of length 1.5–2.5 µm and diameter 100–160 nm [12]. The reason behind the supremacy of this size and shape is that it facilitates the direct contact of AgNPs on cell surfaces to induce cytotoxicity [13]. The other factor that affects the cytotoxicity of AgNPs is the concentration. Low concentrations of AgNPs are safe, while higher concentrations are toxic. When different concentrations of AgNPs were tested on the cell lines, they revealed a dose-dependent increase in cell inhibition [14]. Moreover, when variable doses were tested with different formulations, they showed cytotoxicity or enhanced anticancer activity.

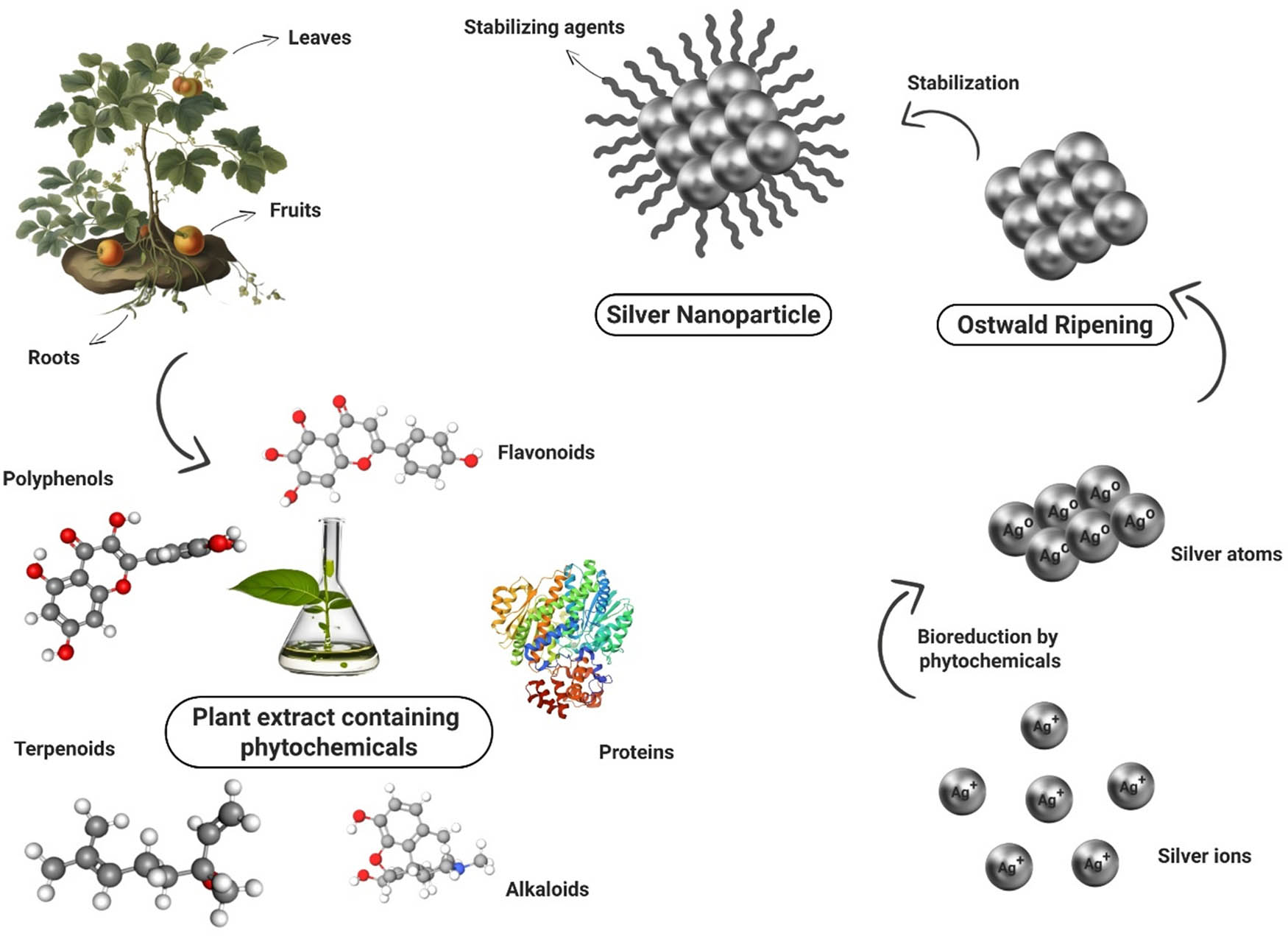

AgNPs could be synthesized via three routes: physical, chemical, and biological. However, plants have emerged as promising candidates for the production of AgNPs for their enhanced scale-up capability, non-toxicity, cost-effectiveness, and simple synthesis method. Moreover, their biocompatibility characteristics and non-pathogenic behavior make them ideal for applications in biomedicine [15]. Alkaloids and flavonoids are phenolic compounds (components of plant extract), soluble in water, and serve as both capping and reducing agents. The biosynthesis of AgNPs using plant extracts is pretty simple. The plant extract is treated with silver precursor like AgNO3 at room temperature, which results in the generation of Ag nanoparticles. However, the characteristics of AgNPs (size and morphology) are defined by the reaction conditions, reaction duration, Ag+ concentration, reaction temperature, extract composition, and stirring rate [16]. The presence of biofunctional groups such as hydroxyl groups, germinal methyl, amine, and polypeptides in plant extracts may be considered to be responsible for the bioreduction of silver ions and the synthesis of AgNPs [17], as shown in Figure 1. Plant-based AgNPs exhibit more antibacterial and antioxidant potential compared to physical or chemical synthesis-based AgNPs [18,19,20]. Therefore, plant-based synthesis of AgNPs has been employed in this research work.

Mechanism of plant-based synthesis of AgNPs.

Cedrela toona Roxb. commonly known as “Tun,” is a medium-sized, deciduous tree indigenous to Pakistan (Figure 2). In Islamabad, Pakistan, it has been extensively planted as an avenue tree. It is planted as a farm forestry tree in parks, gardens, and roadsides. Moreover, it is present along the plain east of the Indus River. The fast-growing capability of Cedrela toona makes it a good choice for reforestation projects. Cedrela toona finds its massive applications in timber, ornamental, fodder, furniture, construction, and medicine. Cedrela toona has a spacious range of utilization in medicine and pharmacology. Its everyday therapeutic use involves the treatment of dysentery and rheumatism [21] and also as an astringent drug [22]. Moreover, the fruit extract of Cedrela toona Roxb. is a natural source of antioxidants [23]. Antibacterial properties have also been reported in the extract of Cedrela toona [24]. In this research work, AgNPs were synthesized using the plant leaf extract of Cedrela toona Roxb. After the formation of AgNPs, they were characterized using UV visible spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). After characterization, the antibacterial and ROS scavenging activity of the AgNPs were evaluated.

Leaves of Cedrela toona.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sample collection

Fresh leaves of Cedrela toona were gathered from the Botanical Garden of Government College University, Lahore, Pakistan. Silver nitrate (AgNO3), methanol (CH3OH), potassium persulfate (K2S2O8), nutrient agar, DPPH (2,2-diphenyl 1 picrylhydrazyl), and ABTS {2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)diammonium salt}, and Luria-Bertani (LB) medium containing agar were provided by Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company.

2.2 Preparation of leaf extract

The leaves were cleansed with tap water and then with distilled water to remove grime or any contamination. Washed leaves were then air-dried for 4 h in the room to avoid rotting. Later, the leaves were shade-dried for 3 days for complete drying. These leaves were milled in a grinder mixture to form a fine powder. Then, 5 g of the fine powder of leaves was boiled for 15 min in 100 ml of distilled water. After heating, the solution was allowed to cool to room temperature. It was filtered utilizing Whatman filter paper No. 1, and the filtrate was stored at 4°C in the refrigerator for further use.

2.3 Synthesis of AgNPs

AgNPs were synthesized following the method of Saleh [25] with slight modifications. The 10 ml leaf extract of Cedrela toona and 90 ml of 1 mM silver nitrate (AgNO3) solution were mixed in the dark to avoid photo-oxidation. The solution was then constantly stirred on a hot plate at 200 rpm and 70°C for 4 h in the dark. After the reaction, AgNPs were centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 20 min and then lyophilized to obtain the powder [26].

2.4 Optimization and characterization

The production conditions were optimized following the method of Khane et al. [2]. The effect of different times (30 min, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 h), temperatures (25°C, 50°C, 60°C, 70°C, and 80°C), plant extract concentrations (1:9, 2:8, 3:7, 4:6, and 5:5), and AgNO3 concentrations (0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mM) on the production of AgNPs was evaluated using UV-vis spectroscopy. The optimum conditions were defined to maximize the production of AgNPs. FTIR was performed for the identification of functional groups that served as reducing and capping agents in the biosynthesis of AgNPs. Transmittance was measured in the range between 400 and 4,000 cm−1 at 25°C. The XRD patterns were recorded using a single crystal X-ray diffractometer (Kappa Apex Ⅱ Bruker, Germany) for size analysis, and they confirmed the presence of silver. The morphology and size distribution of AgNPs were assessed utilizing SEM and ImageJ software.

2.5 Antibacterial activity

The antibacterial activity of the biosynthesized AgNPs against Gram-positive, i.e., Bacillus subtilis, Enterococcus faecalis, and Staphylococcus aureus, and Gram-negative bacteria, i.e., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, and Escherichia coli was done using the agar well diffusion method. All bacterial strain suspensions (1–2 × 108 CFU·ml−1) were prepared following Balouiri et al. [27]. The experimental bacteria were swabbed on the Petri dishes containing an autoclaved LB agar medium. Wells were made using agar, and 50 µl of each concentration of AgNPs (50, 100, 150, and 200 µg·ml−1) was loaded in each well. Ampicillin (200 µg·ml−1) was used as a control in well 5. Plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C, and the zone of inhibitions was measured [28].

2.6 Antioxidant activity

2.6.1 DPPH assay

The ROS scavenging activity of the biosynthesized AgNPs was determined using the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl 1 picrylhydrazyl) assay [29]. Different concentrations (12, 25, 50, 75, 100, 125, and 150 µg·ml−1) of AgNPs, plant extract, and ascorbic acid were prepared, and 1 ml of each dilution was taken in separate test tubes. In each test tube, 1 ml of 1 mM DPPH solution was pipetted, and the test tubes were incubated in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. After 30 min, the absorbance of all samples and the control was measured at 517 nm. A 1 mM DPPH solution was used as the control. The following formula (Eq. 1) was used for the calculation of the percentage inhibition of all samples:

where A c is the absorbance of the control and A s is the absorbance of the sample.

2.6.2 ABTS assay

The ABTS {2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)} assay was performed using the method of Re et al. [30] with slight modifications. Potassium persulfate (2.45 mM) (K2S2O8) was reacted with 2 mM ABTS in water and then kept in the dark for 6 h. Then, 0.1 mM sodium phosphate buffer was added to the solution to fix absorbance at 734 nm. Late, 3 ml of different concentrations (12, 25, 50, 75, 100, 125, and 150 µg·ml−1) of AgNPs, plant extract, and ascorbic acid were reacted with 1 ml of ABTS solution. After 30 min, the absorbance of all samples and the control was measured at 734 nm. The following formula (Eq. 2) was used for the calculation of the percentage inhibition of all samples:

where A c is the absorbance of the control and A s is the absorbance of the sample.

2.7 Cytotoxic activity

The cytotoxic activity of Cedrela toona-mediated AgNPs was determined using the MTT assay following the protocols of Satyavani et al. [31] and Krishna et al. [32] with minor changes. The MCF-7 cells were cultivated in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s red medium (Sigma Life Science) containing 10% fetal bovine serum. The cell lines were cultivated at a density of 1.2 × 104 cells/well for 24 h at 37°C in the 96-well culture plates. After 24 h of incubation, 2 mg·ml−1 dilution of AgNPs was prepared, and from the first well, two-fold dilution was performed from 1:1 to 1:512 with the sample ranging from 1,000 to 1.95 µg·ml−1. The control well contained only the cell lines, while the negative control did not contain any viable cells. After 4 h of incubation, the supernatant was removed, and 200 µg·ml−1 MTT solution (5 mg·ml−1 in phosphate buffer saline) was added to each well and again incubated for 4 h in a 5% CO2 incubator. The media was discarded again after 4 h of incubation, and 100 µl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added. The plate was incubated for another 15 min, and then absorbance was recorded at 590 nm using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader. The percentage of cell viability was measured using the following formula:

2.8 Statistical analysis

All the analyses were performed in triplicate, and the data are represented as mean ± standard deviation. Analyses were conducted using Excel (2021) and OriginPro 8.5 software. The X’pert highScore plus was used for XRD analysis, and ImageJ software was used for size distribution analysis. A P value < 0.05 was regarded as significant.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 UV-vis spectra analysis

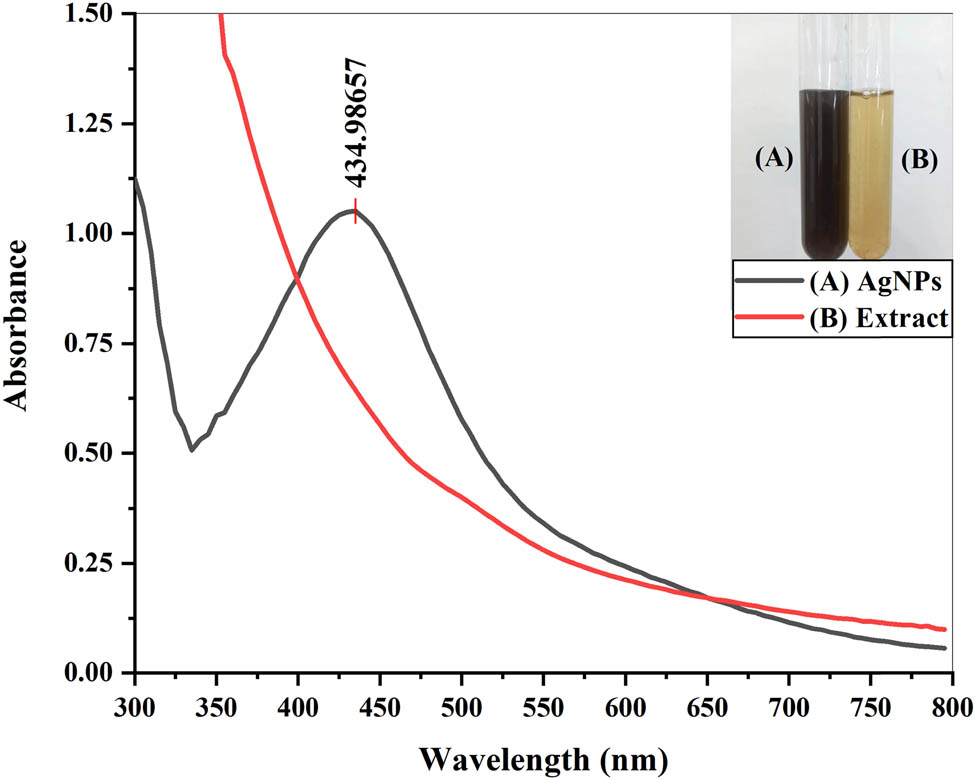

The biosynthesis of AgNPs was confirmed by the color change of the reaction mixture from yellow to dark brown after 4 h of incubation. The color change can be attributed to the reduction of Ag+ into Ag0 in the colloidal solution of AgNPs. The intensity of color increased with an increase in time, indicating that more and more reduction of Ag+ was taking place. After 4 h, the color remained stable, indicating that maximum Ag+ had reduced. Then, the AgNP solution was subjected to UV-visible analysis along with plant extract. Metal nanoparticles, like AgNPs, reveal a strong absorption of electromagnetic waves. The collective oscillations of conductive electrons are stimulated when visible light is cast upon metal nanoparticles, and hence, surface plasmon resonance bands are formed [33]. UV-visible spectroscopy of the Cedrela toona leaf extract and the reaction mixture was performed to confirm the fabrication of AgNPs. No absorbance peak was visible in the plant extract. However, a clear SPR band at 434.98 nm affirmed the formation of AgNPs in the reaction mixture, as shown in Figure 3. Similar results were reported by Alahmad et al. [34], Mukaratirwa-Muchanyereyi et al. [35], and Khan et al. [36].

UV-visible spectra of the plant extract and AgNPs.

3.2 Optimization

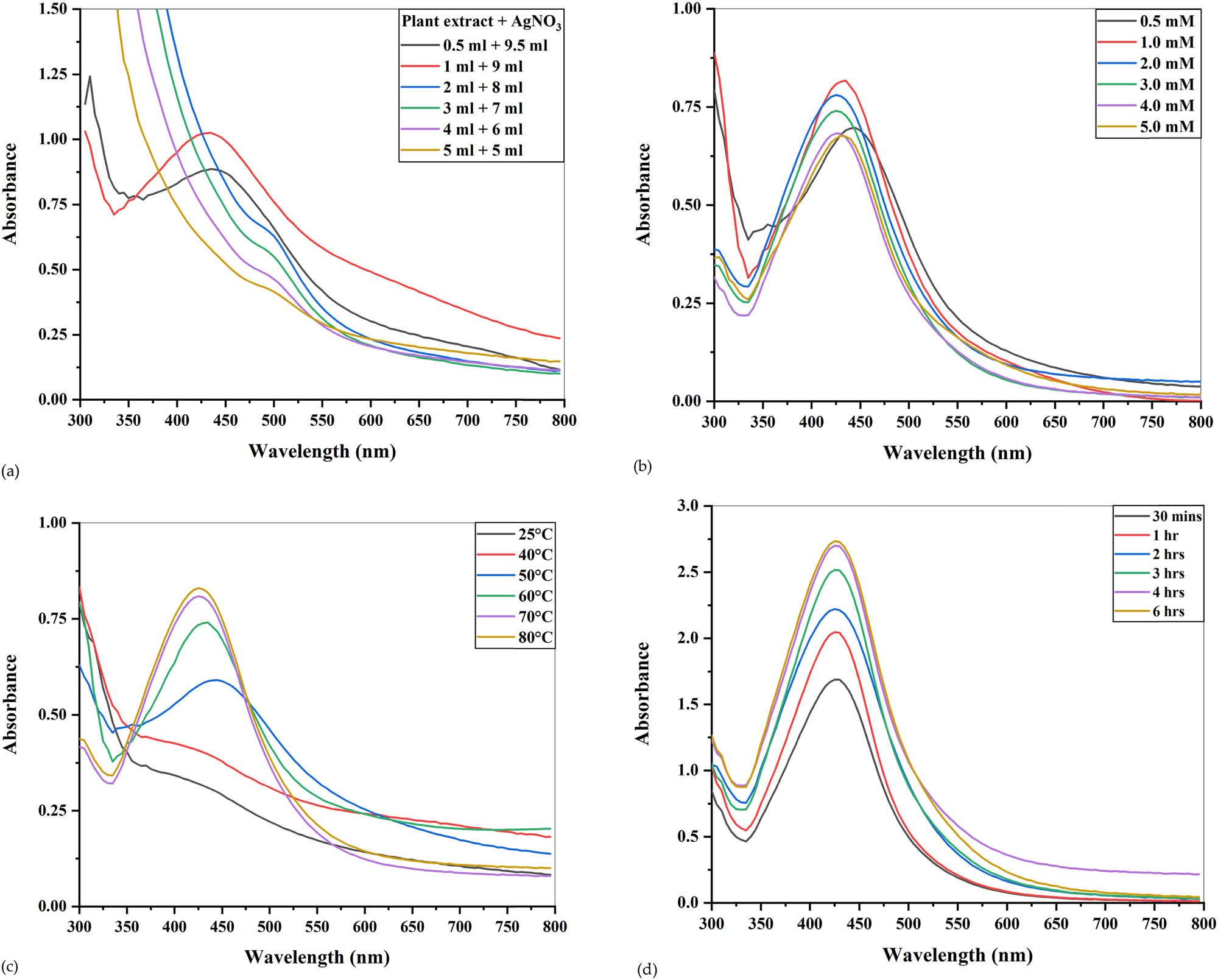

Optimization of different parameters is important to achieve the optimum conditions required for the biosynthesis of Ag nanoparticles. Different parameters, i.e., extract concentration, AgNO3 concentration, temperature, and time, were optimized to enhance the production of AgNPs. In the current study, absorbance peaks were seen to decline with increasing concentration of the Cedrela toona extract (Figure 4a), indicating that with increasing plant concentration, the production of AgNPs declined. Similar results were observed by Fuloria et al. [37], where Erythrina fusca leaf extracts were treated with 1 mM AgNO3 in different ratios. Only 1:9 and 2:8 concentrations showed peaks at 439 nm, and no absorption peaks were observed for 3:7, 4:6, and 5:5 concentrations, indicating no formation of AgNPs. Jamdagni et al. [38] used the extract of Elettaria cardamomum and AgNO3 in different ratios for the biosynthesis of Ag nanoparticles and observed a sharp absorbance peak at a 1:9 concentration, which reduced with increasing concentration of the plant extract. Usmani et al. [39] used the seed extract of Nigella sativa in different concentrations (1/9, 2/8, 3/7, 4/6, and 5/5) and treated it with 1 mM of silver nitrate to synthesize AgNPs. Maximum absorbance was seen at a 1:9 concentration with a peak at 432 nm because of high surface plasmon resonance. Other studies conducted by Khane et al. [2], Sarsar et al. [40], and Jha et al. [41] also concluded that increasing plant extract concentration decreased the sharpness of the absorption spectrum, indicating a decline in the production of AgNPs. Therefore, the concentration (1:9) with a maximum absorbance peak was selected as suitable for further optimization.

UV-visible spectra of optimization conditions for the production of AgNPs. (a) Different ratios of the plant extract and AgNPs, (b) different concentrations of AgNO3, (c) varying temperature, and (d) time of incubation.

The molar concentration of silver nitrate was optimized by preparing silver nitrate in varying concentrations (0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mM) and mixing them with the leaf extract in 1:9 concentration. After incubation of 4 h at 70°C, the color change was seen in all the reaction mixtures. The absorbance increased from 0.5 to 1 mM AgNO3 concentration but above 1 mM; it started to decline slightly (Figure 4b) because, at low substrate concentration, size reduction takes place quickly due to excess availability of functional groups, i.e., hydroxyl groups, germinal methyl, amine, and polypeptides in the leaf extract. However, when the substrate concentration is increased from 1 to 5 mM, the particles start to aggregate and form large masses because of the competition between functional groups and silver ions [42]. Similar results were obtained by Vanaja et al. [43], who used the leaf extract of Coleus aromaticus for the production of AgNPs. Out of five concentrations (1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mM), 1 mM AgNO3 concentration gave the maximum absorbance, and increasing the substrate concentration above that caused a gradual decrease in absorbance. Abambagade and Belete [44] used different AgNO3 concentrations from 0.25 mM up to 1.25 mM, and absorbance increased with increasing substrate concentration. However, after 1 mM concentration, the SPR band shifted to a higher wavelength, suggesting the aggregation of synthesized AgNPs. Response surface methodology adopted by Chowdhury et al. [45] also suggested that a 1 mM concentration of AgNO3 was best for the maximum production of AgNPs. Another study conducted by Singh et al. [46] concluded that increasing the substrate concentration above 1 mM caused the aggregation of AgNPs. Other experiments performed on leaf extracts also concluded that 1 mM AgNO3 was pre-eminent for the production of AgNPs [47,48,49].

Temperature is another important variable that needs to be optimized because the reaction kinetic of AgNP production is controlled by it [50]. The influence of temperature on the fabrication of AgNPs was evaluated by using varying temperatures, i.e., 25°C, 50°C, 60°C, 70°C, and 80°C, without varying the other constants. Color change of reaction mixtures was rapid at a higher temperature because high temperature fastens the reduction of silver nitrate, as observed by Seifipour et al. [51]. Also, the intensity of color is enhanced by increasing temperature. Moreover, a hypsochromic shift (shift of absorbance to shorter wavelength) was also seen in the absorption peaks with increasing temperature (Figure 4c). A similar blue shift or hypsochromic shift was seen by Ramesh et al. [52] while increasing the incubation temperature from 25°C to 90°C for the production of AgNPs from the leaf extract of Ficus hispida Linn. At room temperature and 40°C, no absorption peaks were visible. However, from 50°C to 80°C, the absorption peak increased with maximum absorbance at 80°C. No color change was observed between the reaction mixture incubated at 70°C and 80°C, and a very slight peak difference was evident, suggesting that after 70°C, there was no significant increase in the reaction, and the reaction mixture moved to stabilization. Hence, 70°C could be considered as the optimum temperature for the biosynthesis of Ag nanoparticles from the Cedrela toona extract. An analogous phenomenon was observed by Ismail et al. [53] while producing AgNPs from the fruit extracts of Durenta erecta. An increase in temperature from 30°C to 70°C elevated the rate of reaction and formation of AgNPs, but between 70°C and 80°C, no further increase was evident, which could be attributed to the complete bioreduction of silver into AgNPs, and absorbance peaks were formed very close to each other. Dada et al. [50] also found that the rate of synthesis of AgNPs from the extract of Acalypha wilkesiana increased with the increase of reaction temperature from 30°C to 100°C. In an attempt to produce AgNPs from the leaf extract of F. latisecta, Mohammadi et al. [54] inferred that the largest growth rates were achieved at 70°C. Aslam et al. [55] also evaluated different temperatures for the synthesis of AgNPs from Sanvitalia procumbens and found that 70°C temperature was most suitable. Other studies also found that 70°C was the optimum temperature [56,57,58].

Incubation time is a crucial criterion that needs to be controlled to optimize the size and stability of Ag nanoparticles. All the reaction mixtures were incubated at different intervals of time (30 min, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 h) and then subjected to UV-visible spectroscopy. By increasing the time of incubation, the hyperchromic effect was seen (Figure 4d), suggesting an increase in the number of AgNPs [59]. After 4 h of incubation, no change in color and closeness of 4 and 6 h SPR bands indicated that AgNPs had moved toward stabilization because of the stabilization agents present in the plant extract [60]. An increase in the intensity of the SPR band was also reported by Hashem et al. [61] while producing AgNPs from Ferula persica. After the maximum absorbance at 1 h incubation time, the reaction moved toward stabilization, and no further increase in the SPR band was seen after increasing the time interval. Logeswari et al. [62] noticed the increase in absorbance by increasing the time intervals while producing AgNPs from five different plant extracts, i.e., C. sinensis, S. tricobatum, O. tenuiflorum, C. asiatica, and S. cumini. Kumar et al. [63] noticed that enhancing the incubation time from 1 to 4 h increased the reduction of silver ions from the Annona squamosa extract, hence increasing the intensity of color. Synthesis of AgNPs was completed after 4 h, and no further color change was evident in the mixture. Similar patterns of SPR bands were also observed when extracts were used for the bioproduction of AgNPs [64,65,66]. Moreover, the 4 h of incubation time gave maximum absorbance peaks when extracts of Hippophae rhamnoides, Berberis asiatica, Ganoderma lucidum, Protium serratum, and Avena sativa were used for the production of AgNPs [67,68,69,70,71]. Keeping in view all the above, the maximum production of AgNPs could be attained by mixing the Cedrela toona leaf extract with the 1 mM AgNO3 in 1:9 concentration at 70°C for 4 h.

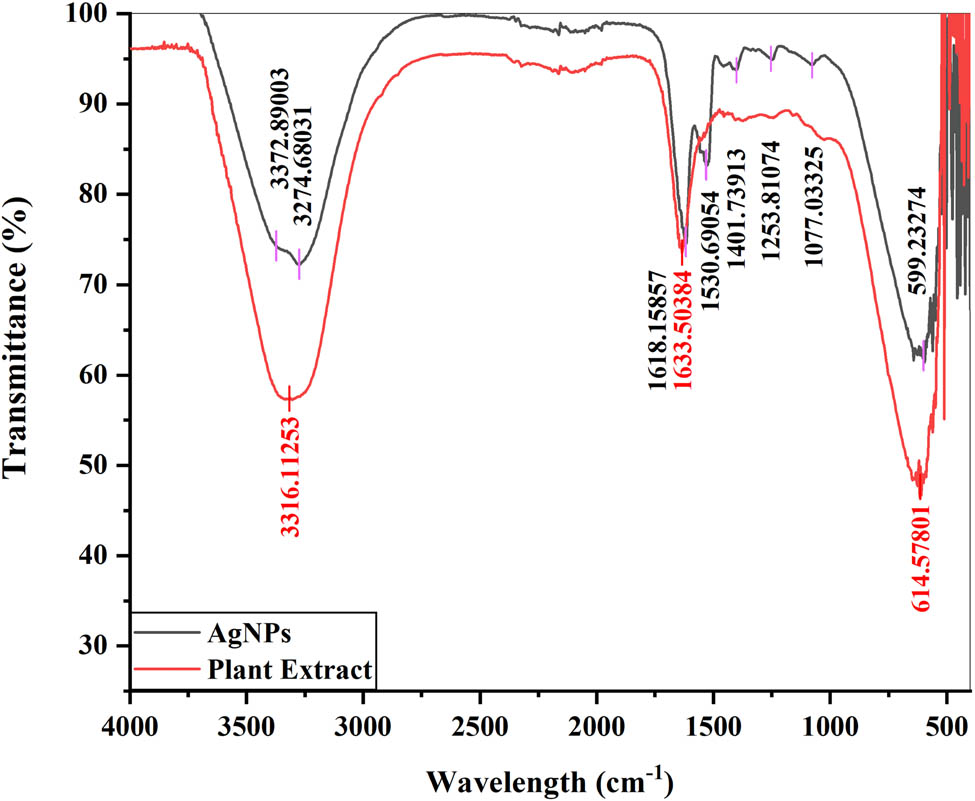

3.3 FTIR analysis

FTIR analysis of both leaf extract of Cedrela toona and synthesized AgNPs was carried out to find the involvement of functional groups (Figure 5). All the peaks and their corresponding functional groups are listed in Table 1. In the FTIR spectrum of the plant extract, the broad peak at 3,316 cm−1 indicated the N–H and O–H stretching vibration of amides [72,73,74]. The sharp peak at 1,633 cm−1 could be assigned to the bending vibration of the carbonyl group of alkenes [75], carboxylic acids, phenols [76], tertiary amides [77], steroids, flavonoids [78], aromatic compounds [79], or the presence of amide Ⅰ group of proteins [80] and band at 614 cm−1 was conferred to the P–O–C and C–O–O bonding of aromatic phosphates [81].

FTIR spectra of AgNPs and the plant extract.

Assignment of main FTIR peaks of the Cedrela toona leaf extract and synthesized AgNPs

| Sample | Wavelength (cm−1) | Bond/stretching | Functional groups |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous leaf extract | 3,316.11 | N–H and O–H stretching | Amides |

| 1,633.50 | −C═O stretching | Alkenes, carboxylic acids, phenols, tertiary amides, steroids, flavonoids, and aromatic compounds | |

| 614.57 | P–O–C and C–O–O bonding | Aromatic compounds | |

| AgNPs | 3,372.89 | N–H stretching | Primary amines |

| Hydroxyl/C═O stretching | Phenols, alcohols, triterpenoids, and flavonoids | ||

| 3,274.68 | O–H stretching | Phenols and alcohols | |

| N–H stretching | Amines | ||

| 1,618.15 | −C═C− stretching | Aromatic compounds | |

| −COO− or the C═O stretching | Phenols or flavonoids | ||

| 1,530.69 | N–H | Secondary amines | |

| 1,401.73 | C–C or C═C stretching | Alkanes or benzene | |

| 1,253.81 | C–N stretching | Amides | |

| C–O stretching | Esters | ||

| 1,077.03 | −C–O− or −C–O–C− stretching | Ethers, esters, carboxylic acids, and alcohols, especially terpenoids or flavanones | |

| C–N stretching | Amines | ||

| 599.23 | C–C–C–N bonding | Nitrites | |

| C–H stretching | Cellulose |

In the FTIR spectrum of AgNPs, the broad peak at 3,372 cm−1 was assigned to the stretching vibrations of primary amines [82] or the hydroxyl/C═O group of carboxylic acids referring to the presence of phenols, alcohols [83], triterpenoids, and flavonoids [84]. The band at 3,274 cm−1 was attributed to the O–H bond stretching of phenols and alcohols [85] or the amines’ N–H stretching, which are absorbed by AgNPs and are cited in the literature for their ability to reduce silver ions [86]. The peak at 1,618 cm−1 could be attributed to the −C═C− stretching of aromatic compounds [87,88], the stretching vibrations of the carboxylate anion group (COO) [89], or the C═O stretches of phenols and flavonoids [90]. The peak at 1,530 cm−1 referred to bonding and stretching vibrations of secondary amines [91], indicating the presence of proteins [92], while the small peak at 1,401 cm−1 corresponded to the C–C or C═C stretches of alkanes or benzene [93,94]. The band at 1,253 cm−1 was assigned to the C–N stretching vibrations of the amide group [95,96], indicating the presence of proteins [97] or the C–O stretches of ester [13]. The peak at 1,077 cm−1 was assigned to the −C–O− or –C–O–C− stretching vibrations of ethers, esters, carboxylic acids, and alcohols [98,99], especially the ether linkages of terpenoids or flavanones on surfaces of AgNPs [100], or C–N stretching of amines [101,102] and the broad peak at 599 cm−1 was assigned the C–C–C–N of nitrites [103] or C–H stretching vibrations of cellulose [104].

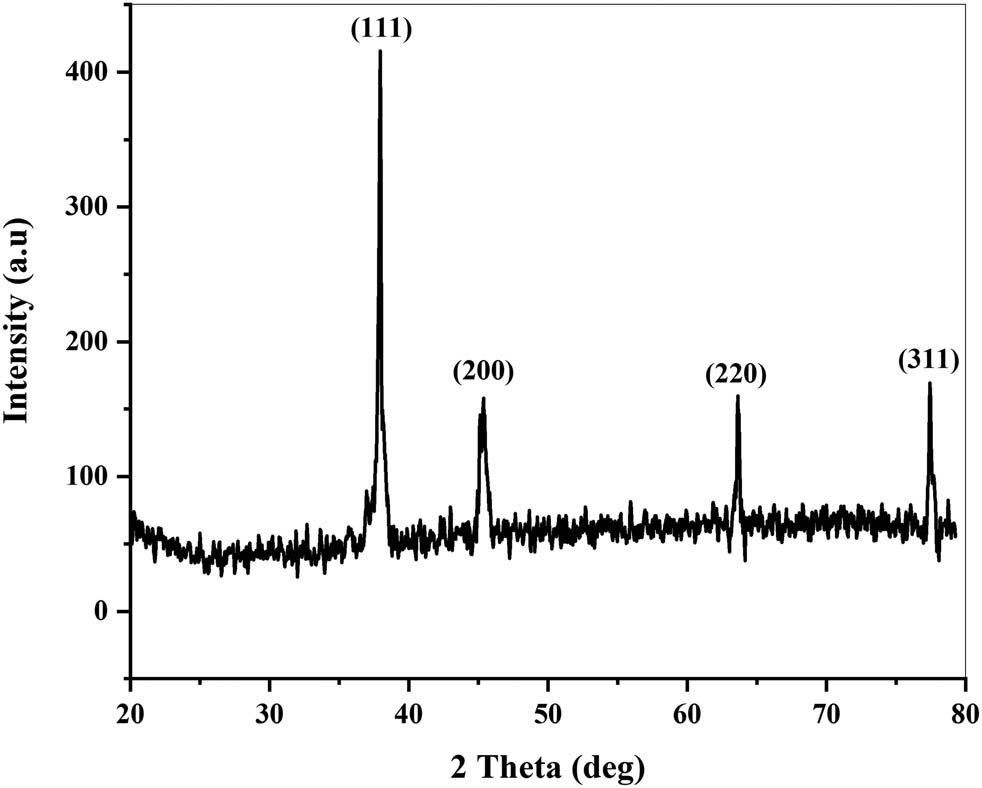

3.4 XRD analysis

XRD analysis of powdered AgNPs was done to confirm the presence of AgNPs and to know about the structural information of particles. Figure 6 shows the XRD pattern of AgNPs. Clear peaks at (2θ) 37.92, 45.33, 63.65, and 77.47 corresponding to (111), (200), (220), and (311) planes can be seen in the XRD pattern, which indicated the face-centered, cubic, and crystalline nature of AgNPs [105,106,107]. The size of the crystallites was found using the Debye–Scherrers’ equation (Eq. 3). The mean size of particles was found to be 25.9 nm.

where D is the crystallite size (nm), K (= 0.9) is the Scherrer constant, λ (= 0.15406 nm) is the wavelength of X-ray sources, β is the FWHM (rad), and θ is the peak position (rad).

XRD pattern of AgNPs synthesized using the leaf extract of Cedrela toona (numbers show the face-centered cubic planes of AgNPs).

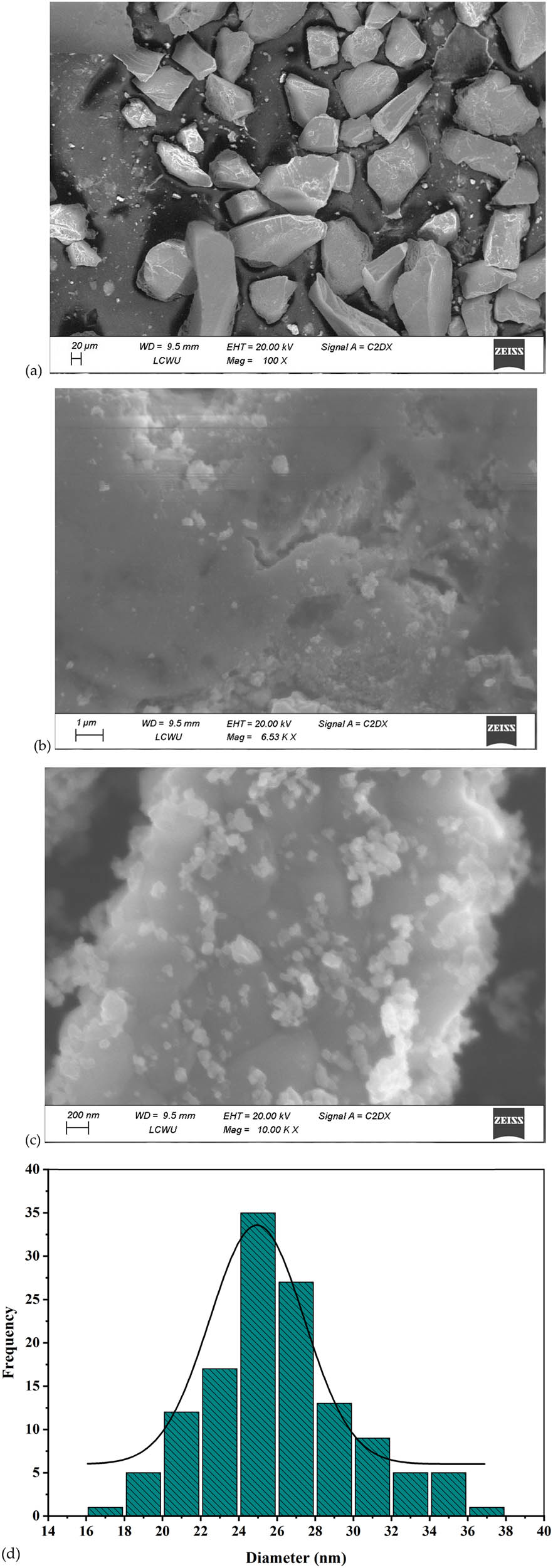

3.5 SEM analysis

SEM analysis reveals the morphology and size distribution of AgNPs (Figure 7a–c). The images show that AgNPs have spherical shapes, which corroborates with other findings [108,109]. The nanoparticles ranged in size between 22 and 30 nm, as depicted by the histogram (Figure 7d), with a mean average size of 25.5 nm. SEM results correlate with XRD size analysis. While producing AgNPs from the plant, several studies have reported a similar size distribution [110,111].

SEM analysis of AgNPs synthesized using the Cedrela toona leaf extract: (a) 100× magnification, (b) 6,530× magnification, (c) 10,000× magnification, and (d) particle size distribution histogram of AgNPs.

3.6 Antibacterial potential

The antibacterial activity of the AgNPs was tested against E. coli, P. aeruginosa, B. subtilis, and S. aureus (Figure 8). AgNPs synthesized using the Cedrela toona extract exhibited potent antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. The maximum antibacterial activity is seen against P. mirabilis (23 ± 0.5 mm), as shown in Table 2, because of its Gram-negative nature. The Gram-negative bacteria are more susceptible to AgNPs because of the scarcity of peptidoglycan layer enabling the serene entry of AgNPs [112]. Moreover, the AgNPs also release silver ions, which can pass through porins on the cell wall and could cause disruption in DNA replication [113]. E. faecalis produced a wider zone of inhibition compared to P. aeruginosa, which agrees with the results of Jeevitha and Rajeshkumar [114] when AgNPs synthesized from Spatoglossum asperum were used. Larger zones were seen when AgNPs were used against S. aureus compared to E. coli, which corroborates with the findings of Raut et al. [115] and Shahverdi et al. [116], who attributed the antibacterial activity to DNA disruption, ROS generation, direct damage to cell membranes, or loss of permeability [117]. The diameter of zones was found to be largest against P. mirabilis, followed by E. faecalis (21 ± 0.5 mm), B. subtilis (20 ± 0.9 mm), P. aeruginosa (18 ± 0.3 mm), S. aureus (16 ± 0.7 mm), K. pneumoniae (16 ± 0.3 mm), and E. coli (14 ± 0.7 mm). The exact mechanisms of antibacterial activity are still a mystery to the scientific world. Perhaps, the release of Ag+ ions, which may interact with nucleic acids or specifically nucleosides of nucleic acids [118] or may adhere to the cell wall or cytoplasm because of their affinity toward sulfur proteins [119], could be the possible reasons for antibacterial activity. As a result, the functionality of respiratory enzymes is shut down, causing an interruption in ATP and the production of ROS [120]. Moreover, protein synthesis can easily be halted by denaturation of ribosomal components by silver ions [121]. In addition, AgNPs themselves can also inhibit bacterial growth [122]. Their small size eases their entry through the bacterial cell wall, which then induces cell membrane disruption, organelles rupture, and even cell lysis. AgNPs can also dephosphorylate the tyrosine residuals, disrupting the signal transduction pathway leading to cell apoptosis and halting cell division [123].

Agar well diffusion assay against (a) Staphylococcus aureus, (b) Bacillus subtilis, (c) Escherichia coli, (d) Pseudomonas aeruginosa, (e) Klebsiella pneumoniae, (f) Enterococcus faecalis, and (g) Proteus mirabilis, where 1 (50 µg·ml−1), 2 (100 µg·ml−1), 3 (150 µg·ml−1), 4 (200 µg·ml−1), and 5 (200 µg·ml−1 of control).

Diameter of zone of inhibitions for AgNPs with different bacterial strains and control drug, i.e., ampicillin

| Diameter of zone of inhibitions (mm) (Mean ± SD) for different doses (µg·ml−1) of AgNPs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strain | Control | 50 | 100 | 150 | 200 |

| B. subtilis | — | 17 ± 0.3 | 18 ± 0.3 | 19 ± 0.7 | 20 ± 0.9 |

| S. aureus | — | 12 ± 0.4 | 13 ± 0.3 | 13 ± 0.9 | 16 ± 0.7 |

| P. aeruginosa | — | 14 ± 0.4 | 15 ± 0.2 | 15 ± 0.9 | 18 ± 0.3 |

| E. coli | — | 9 ± 0.4 | 11 ± 0.6 | 13 ± 0.3 | 14 ± 0.7 |

| K. pneumoniae | 14 ± 0.2 | 13 ± 0.2 | 14 ± 0.1 | 14 ± 0.8 | 16 ± 0.3 |

| E. faecalis | 7 ± 0.2 | 15 ± 0.7 | 16 ± 0.2 | 17 ± 0.3 | 21 ± 0.5 |

| P. mirabilis | 19 ± 0.2 | 16 ± 0.3 | 18 ± 0.9 | 19 ± 0.2 | 23 ± 0.5 |

A P value < 0.05 was regarded as significant.

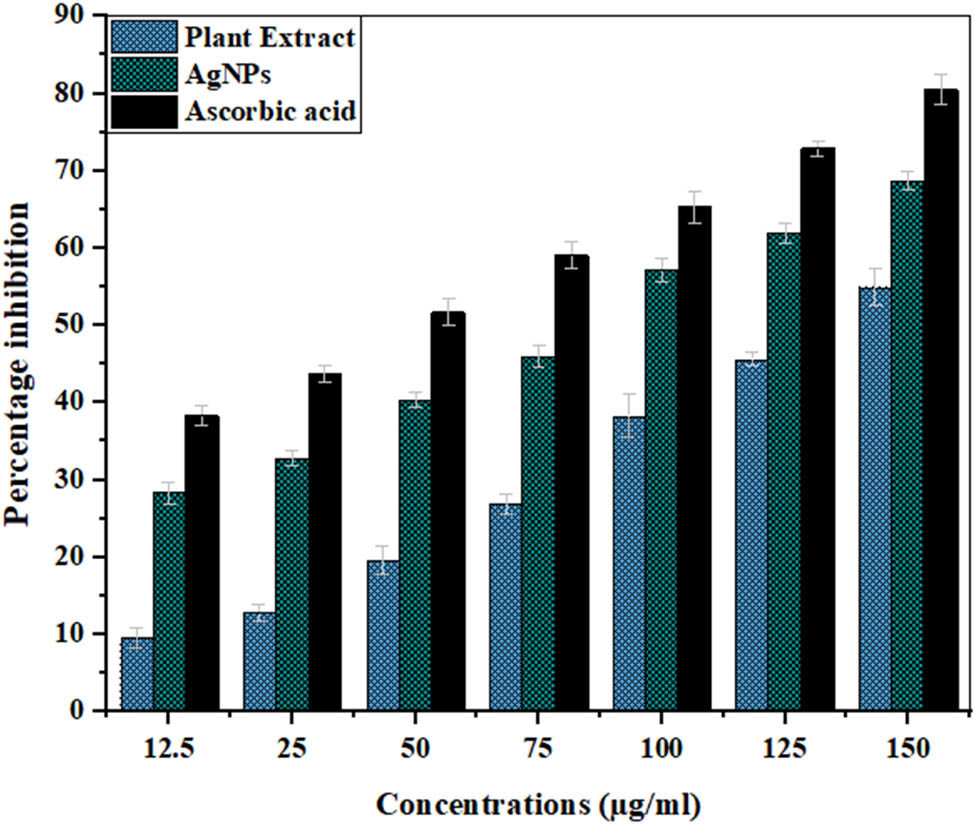

3.7 Antioxidant activity

3.7.1 DPPH activity

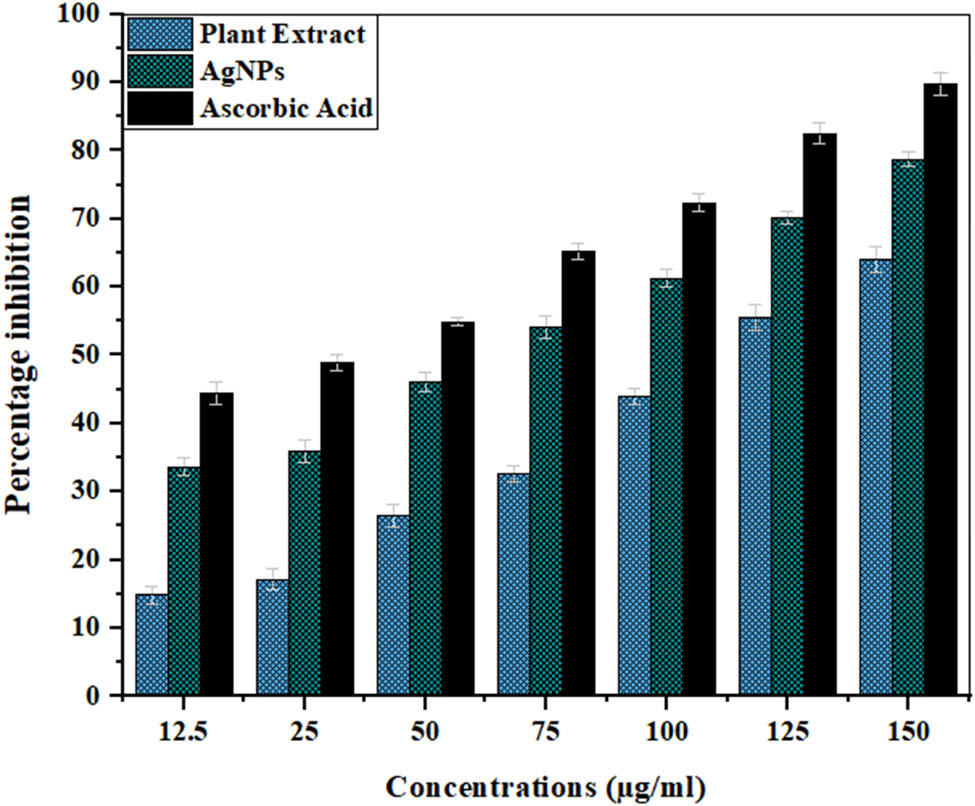

DPPH scavenging assay is one of the most frequently used antioxidant assays in this research work. DPPH˙ is the free radical that is purple in color and gives absorbance at 517 nm. Hydrogen donors reduce DPPH˙ to DPPH form (hydrazine form), and its color changes from purple to pale yellow, and the extent of color depends on the number of antioxidants used [124]. In the current study, the antioxidant activity of the plant extract and synthesized AgNPs is compared with ascorbic acid, which is used as a standard. A dose-dependent behavior can be seen (Table 3, Figure 9) for all three samples, where increasing the concentration increases the antioxidant activity. However, the antioxidant activity of AgNPs was found to be higher than the plant extract and lower than the standard. The maximum inhibition by AgNPs (68.72%), ascorbic acid (80.44%), and extract (55.09%) was shown at a concentration of 150 µg·ml−1. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for AgNPs was found at 69.62 µg·ml−1, while those for the plant extract and standard were 149.47 and 32.81 µg·ml−1. Similar results were reported when plant extracts of Withania coagulans, Arum italicum, Grewia optiva, Citrus lemon, Justicia gendarussa, Tropaeolum majus, Pyrus betulifolia, and Allium ampeloprasum and AgNPs synthesized from them were checked for their antioxidant activities [125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132]. The higher antioxidant activity of AgNPs can be attributed to the functional groups (alcohols, phenols, flavonoids, terpenoids) present in the Cedrela toona extract that served as reducing and capping agents and became part of the AgNPs [133,134].

DPPH radical scavenging activity of the Cedrela toona extract, synthesized AgNPs, and ascorbic acid

| Samples | Concentrations (µg·ml−1) | Scavenging activity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Plant extract | 12.5 | 9.56 ± 1.33 |

| 25 | 12.82 ± 1.02 | |

| 50 | 19.60 ± 1.87 | |

| 75 | 26.92 ± 1.32 | |

| 100 | 38.32 ± 2.76 | |

| 125 | 45.68 ± 0.84 | |

| 150 | 55.09 ± 2.37 | |

| IC 50 | 149.47 ± 0.15 | |

| Synthesized AgNPs | 12.5 | 28.32 ± 1.34 |

| 25 | 32.82 ± 1.06 | |

| 50 | 40.37 ± 0.93 | |

| 75 | 45.97 ± 1.39 | |

| 100 | 57.14 ± 1.51 | |

| 125 | 61.87 ± 1.32 | |

| 150 | 68.72 ± 1.21 | |

| IC 50 | 69.62 ± 0.09 | |

| Ascorbic acid | 12.5 | 30.28 ± 1.34 |

| 25 | 43.74 ± 1.16 | |

| 50 | 51.56 ± 1.73 | |

| 75 | 59.08 ± 1.83 | |

| 100 | 65.31 ± 2.03 | |

| 125 | 72.93 ± 0.99 | |

| 150 | 80.44 ± 1.94 | |

| IC 50 | 32.81 ± 0.08 |

DPPH radical scavenging activity of the Cedrela toona extract AgNPs and ascorbic acid. A P value < 0.05 was regarded as significant.

3.7.2 ABTS assay

In the current study, the antioxidant activities of the plant extract and AgNPs are also compared using the ABTS assay while using ascorbic acid as standard. A dose-dependent behavior could be seen (Table 4, Figure 10) for all three samples, just like the DPPH assay. The maximum inhibition by AgNPs (77.63%), ascorbic acid (89.81%), and extract (63.97%) was shown at a concentration of 150 µg·ml−1. The IC50 for AgNPs was found at 47.90 µg·ml−1, while those for the plant extract and standard were 120.45 and 30.30 µg·ml−1. Similar results were reported when the extracts of Cannabis sativa, Astragalus flavesces, and Origanum majorana were used for the production of AgNPs and assessed for antioxidant activity [135,136,137].

ABTS radical scavenging activity of the Cedrela toona extract, synthesized AgNPs, and ascorbic acid

| Samples | Concentrations (µg·ml−1) | Scavenging activity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Plant extract | 12.5 | 14.91 ± 1.29 |

| 25 | 17.12 ± 1.50 | |

| 50 | 26.60 ± 1.69 | |

| 75 | 32.68 ± 1.23 | |

| 100 | 43.95 ± 1.11 | |

| 125 | 55.53 ± 1.95 | |

| 150 | 63.97 ± 1.84 | |

| IC 50 | 120.45 ± 0.24 | |

| Synthesized AgNPs | 12.5 | 32.51 ± 1.34 |

| 25 | 34.81 ± 1.73 | |

| 50 | 45.02 ± 1.38 | |

| 75 | 53.01 ± 1.61 | |

| 100 | 60.18 ± 1.23 | |

| 125 | 69.05 ± 1.04 | |

| 150 | 77.63 ± 1.08 | |

| IC 50 | 47.09 ± 0.13 | |

| Ascorbic acid | 12.5 | 44.48 ± 1.67 |

| 25 | 48.97 ± 1.13 | |

| 50 | 54.91 ± 0.62 | |

| 75 | 65.19 ± 1.23 | |

| 100 | 72.34 ± 1.27 | |

| 125 | 82.52 ± 1.50 | |

| 150 | 89.91 ± 1.65 | |

| IC 50 | 30.25 ± 0.15 |

ABTS radical scavenging activity of the Cedrela toona extract, AgNPs, and ascorbic acid. A P value < 0.05 was regarded as significant.

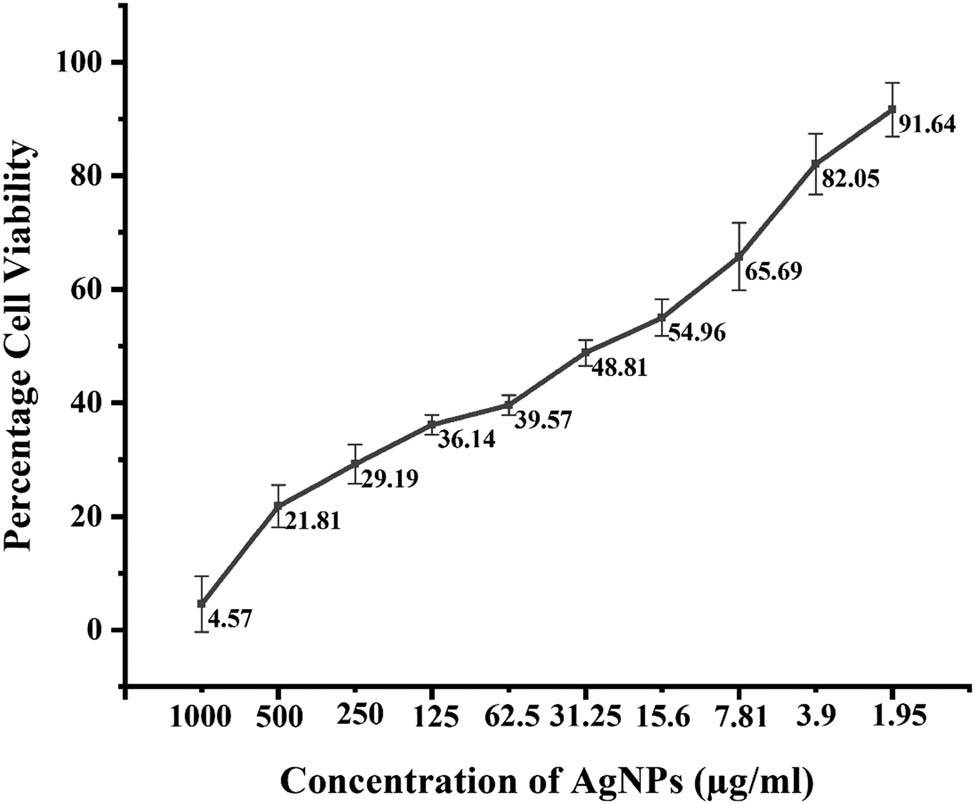

3.8 Cytotoxic activity

When the MTT assay was performed against MCF-7 cells using various concentrations of AgNPs, a dose-dependent behavior was seen, as depicted in Figure 11. The percentage cell viability was calculated using the formula, and the graph was constructed against concentrations of AgNPs. Only 4.57% of cells were viable at the 1,000 µg·ml−1 AgNP concentration and with decreasing AgNP concentration, cell viability enhanced. The IC50 was also calculated using Origin95 software, and was found to be 32.55 ± 0.05 µg·ml−1.

Percentage cell viability of MCF-7 cells against Cedrela toona-mediated AgNPs at various concentrations. A P value < 0.05 was regarded as significant.

AgNPs have an advantage over other anticancer therapies like chemotherapy in that they are only toxic to cancerous cells compared to normal cells, and this toxicity can be attributed to the presence of secondary metabolites [138,139,140]. For instance, when the leaf extract of Ziziphus nummularia was used to produce Ag nanoparticles, the presence of secondary metabolites like glycosides, saponins, alkaloids, and essential oils contributed to the antineoplastic activity against Hela cell lines [141,142]. When the extract of Hypericum perforatum was used to produce Ag nanoparticles and their activity was tested against A549, Hep G2, and Hela cells, the phenolic compounds that acted as capping agents were found responsible for antineoplastic behavior [143]. Apart from phenolic compounds, the flavonoids and tannins can also support the anticancer behavior of Carica papaya-mediated AgNPs against Hep-2 and MCF-7 cells [144]. In the case of banana leaf extract-mediated AgNP synthesis, the antitumor behavior against MCF-7 and A549 cells was ascribed to ROS inflammation, resulting in the dysfunction of physiological processes and, ultimately, cell death [145]. ROS activate caspase 3 was released when AgNPs synthesized from Magnifera indica were used against MCF-7 and Hela cell lines. It stimulated DNA fragmentation, causing membrane leakage and, ultimately, cell death [146].

MTT assay is usually employed to test the cytotoxic potential of AgNPs. The cell lines are incubated for 4 h in the 96-well culture plates to allow them to grow well. After their growth, they are reacted with various concentrations of AgNPs for 4 h. AgNPs react with the cell lines, causing inhibition of cell viability. Then, the MTT dye is added with which the dehydrogenase enzymes of metabolically active cells react. These enzymes reduce the MTT and form purple formazan crystals, which are insoluble in the cell culture medium. Then, DMSO is added, which dissolves and solubilizes these formazan crystals. The more viable cells are present in the culture medium, the more they will produce the purple color and vice versa. Then, the color change is observed using a ELISA reader, which gives the values of this calorimetric assay [147]. In our study, 78.19% cell mortality was seen when 500 µg·ml−1 AgNP concentration was used, and cell mortality increased with increasing concentration of AgNPs, suggesting their cytotoxic role. Similar dose-dependent behavior was seen in other studies performed [148,149]. These findings suggest that the Ag nanoparticles synthesized using the Cedrela toona leaf extract could potentially be used for the production of anticancer drugs.

4 Conclusions

AgNPs have gained much attention for their biomedical applications in antibacterial, antioxidant, and antineoplastic drugs. Moreover, plants have emerged as a potential source of AgNPs because plant-mediated production does not involve the use of hazardous chemicals and does not require long incubation periods. Cedrela toona is a medicinal plant used for dysentery, rheumatism, and astringent drugs. The leaf extract from this plant is used as a capping agent, and AgNPs are produced from it. The optimized conditions were found to enhance the production of AgNPs. Furthermore, biofunctional groups like ethers, esters, carboxylic acids, and alcohols, especially terpenoids, flavanones, alkenes, and amines, were found to be responsible for the reduction of silver to AgNPs. Agar well diffusion assay was performed, and AgNPs were found to be effective against all bacterial strains. Moreover, higher antioxidant activity was reported in AgNPs juxtaposed to the plant extract, suggesting that AgNPs have more ROS scavenging activity. Furthermore, cytotoxic activity was evaluated against MCF-7 cell lines, and Ag nanoparticles were found to have good cytotoxic activity against cancerous cells. The crux of this research is that AgNPs synthesized from the leaf extract of Cedrela toona possessed good antibacterial activity against S. aureus, P. aeruginosa B. subtilis, P. mirabilis, E. faecalis, K. pneumoniae, and E. coli, which emphasized their future role as an antibacterial drug. Moreover, the antioxidant activity of AgNPs with DPPH IC50 of 69.62 µg·ml−1 and ABTS IC50 of 47.90 µg·ml−1 made them more effective against ROS species compared to the plant extract, indicating their role in antioxidant drugs. Their potential extends beyond antibacterial and antioxidant properties to the anticancer as well. The synthesized AgNPs showed significant anticancer activity, which shows that they have the potential to be used as anticancer drugs as well.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers supporting project number (RSP2024R185), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Muhammad Ammar Javed: conceptualization, data curation, methodology, software, writing – original draft, writing – reviewing and editing; Muhammad Nauman Aftab: conceptualization, visualization, supervision, and resources; Muhammad Hassan Sarfraz and Muhammad Sohail Afzal: writing – reviewing and editing, project administration, software, and data curation; Baber Ali and Erum Liaqat: writing – reviewing and editing, software, and data curation; Sikander Ali and Asad ur Rehman: writing – reviewing and editing, funding acquisition, resources; Khaloud Mohammed Alarjani, Mohamed Soliman Elshikh, Liangcai Peng, and Yanting Wang: writing – reviewing and editing, software, funding acquisition, and resources.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Saxena SK, Nyodu R, Kumar S, Maurya VK. Current advances in nanotechnology and medicine. Springer, Nature, Singapore Pte Ltd; 2020.10.1007/978-981-32-9898-9_1Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Khane Y, Benouis K, Albukhaty S, Sulaiman GM, Abomughaid MM, Al Ali A, et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous Citrus limon zest extract: Characterization and evaluation of their antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. Nanomaterials. 2022;12:2013.10.3390/nano12122013Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Rakib-Uz-Zaman SM, Hoque Apu E, Muntasir MN, Mowna SA, Khanom MG, Jahan SS, et al. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from Cymbopogon citratus leaf extract and evaluation of their antimicrobial properties. Challenges. 2022;13:18.10.3390/challe13010018Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Sies H, Belousov VV, Chandel NS, Davies MJ, Jones DP, Mann GE, et al. Defining roles of specific reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cell biology and physiology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022;1–17.10.1038/s41580-022-00456-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Juan CA, Pérez de la Lastra JM, Plou FJ, Pérez-Lebeña E. The chemistry of reactive oxygen species (ROS) revisited: outlining their role in biological macromolecules (DNA, lipids and proteins) and induced pathologies. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:4642.10.3390/ijms22094642Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Dziegielewska-Gesiak S. Metabolic syndrome in an aging society–role of oxidant-antioxidant imbalance and inflammation markers in disentangling atherosclerosis. Clin Interv Aging. 2021;16:1057.10.2147/CIA.S306982Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Mahanta SK, Challa SR. Phytochemicals as Pro-oxidants in Cancer: Therapeutic Implications. Handb Oxid Stress Cancer Ther Asp. 2022;98(3):1–9.10.1007/978-981-16-1247-3_209-1Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Zhao X, Zhou L, Riaz Rajoka MS, Yan L, Jiang C, Shao D, et al. Fungal silver nanoparticles: synthesis, application and challenges. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2018;38:817–35.10.1080/07388551.2017.1414141Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Demirbas A, Welt BA, Ocsoy I. Biosynthesis of red cabbage extract directed Ag NPs and their effect on the loss of antioxidant activity. Mater Lett. 2016;179:20–3.10.1016/j.matlet.2016.05.056Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Naveed M, Batool H, Rehman SU, Javed A, Makhdoom SI, Aziz T, et al. Characterization and evaluation of the antioxidant, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, and cytotoxic activities of silver nanoparticles synthesized using Brachychiton populneus leaf extract. Processes. 2022;10:1521.10.3390/pr10081521Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Elemike EE, Fayemi OE, Ekennia AC, Onwudiwe DC, Ebenso EE. Silver nanoparticles mediated by Costus afer leaf extract: synthesis, antibacterial, antioxidant and electrochemical properties. Molecules. 2017;22:701.10.3390/molecules22050701Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Sankar R, Karthik A, Prabu A, Karthik S, Shivashangari KS, Ravikumar V. Origanum vulgare mediated biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles for its antibacterial and anticancer activity. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013;108:80–4.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.02.033Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Kanniah P, Chelliah P, Thangapandi JR, Gnanadhas G, Mahendran V, Robert M. Green synthesis of antibacterial and cytotoxic silver nanoparticles by Piper nigrum seed extract and development of antibacterial silver based chitosan nanocomposite. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;189:18–33.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.08.056Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Chang X, Wang X, Li J, Shang M, Niu S, Zhang W, et al. Silver nanoparticles induced cytotoxicity in HT22 cells through autophagy and apoptosis via PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Ecotoxicol Env Saf. 2021;208:111696.10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111696Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Habeeb Rahuman HB, Dhandapani R, Narayanan S, Palanivel V, Paramasivam R, Subbarayalu R, et al. Medicinal plants mediated the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their biomedical applications. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2022;16:115–44.10.1049/nbt2.12078Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Rajesh-kumar S, Bharath LV. Mechanism of plant-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles – A review on biomolecules involved, characterisation and antibacterial activity. Chem Biol Interact. 2017;273:219–27.10.1016/j.cbi.2017.06.019Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Sivakumar M, Surendar S, Jayakumar M, Seedevi P, Sivasankar P, Ravikumar M, et al. Parthenium hysterophorus mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and its evaluation of antibacterial and antineoplastic activity to combat liver cancer cells. J Clust Sci. 2021;32:167–77.10.1007/s10876-020-01775-xSuche in Google Scholar

[18] Raja K, Balamurugan V, Selvakumar S, Vasanth K. Striga angustifolia mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Anti-microbial, antioxidant and anti-proliferative activity in apoptotic p53 signalling pathway. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2022;67:102945.10.1016/j.jddst.2021.102945Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Khatamifar M, Fatemi SJ, Torkzadeh-Mahani M, Mohammadi M, Hassanshahian M. Green and eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles by Quercus infectoria galls extract: thermal behavior, antibacterial, antioxidant and anticancer properties. Part Sci Technol. 2022;40:281–9.10.1080/02726351.2021.1941455Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Jain N, Jain P, Rajput D, Patil UK. Green synthesized plant-based silver nanoparticles: Therapeutic prospective for anticancer and antiviral activity. Micro Nano Syst Lett. 2021;9:1–24.10.1186/s40486-021-00131-6Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Farnaz M, Tahira M, Humayun R, Abdul H, Shahzad H. Biological screening of seventeen medicinal plants used in the traditional systems of medicine in Pakistan for antimicrobial activities. Afr J Pharm Pharmacol. 2010;4:335–40.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Vermani A, Navneet P, Chauhan A. Physico-chemical analysis of ash of some medicinal plants growing in Uttarakhand, India. Nat Sci. 2010;8:88–91.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Shah KH, Patel PM. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of Cedrela toona Roxb. Leaf Extracts. Himal J Heal Sci. 2021;24–31.10.22270/hjhs.v6i1.93Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Shahh KH, Patel PM. Evaluation of antimicrobial activity of Cedrela toona Roxb. Fruit Extracts. J Drug Deliv Ther. 2021;11:108–9.10.22270/jddt.v11i1.4540Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Saleh RF. Biosynthesis of AgNPs by using Brassica Oleracea Capitata and Inhibitory Effect on some Pathogens Bacteria; 2022.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Abdel-Aziz MS, Shaheen MS, El-Nekeety AA, Abdel-Wahhab MA. Antioxidant and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles biosynthesized using Chenopodium murale leaf extract. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2014;18:356–63.10.1016/j.jscs.2013.09.011Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Balouiri M, Sadiki M, Ibnsouda SK. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J Pharm Anal. 2016;6:71–9.10.1016/j.jpha.2015.11.005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Devillers J, Steiman R, Seigle-Murandi F. The usefulness of the agar-well diffusion method for assessing chemical toxicity to bacteria and fungi. Chemosphere. 1989;19:1693–700.10.1016/0045-6535(89)90512-2Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Chandraker SK, Lal M, Dhruve P, Singh RP, Shukla R. Cytotoxic, antimitotic, DNA binding, photocatalytic, H2O2 sensing, and antioxidant properties of biofabricated silver nanoparticles using leaf extract of Bryophyllum pinnatum (Lam.) Oken. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;7:1–17.10.3389/fmolb.2020.593040Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Re R, Pellegrini N, Proteggente A, Pannala A, Yang M, Rice-Evans C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26:1231–7.10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00315-3Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Satyavani K, Gurudeeban S, Ramanathan T, Balasubramanian T. Toxicity study of silver nanoparticles synthesized from Suaeda monoica on Hep-2 cell line. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2012;4:35–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Krishna G, Srileka V, Singara Charya MA, Abu Serea ES, Shalan AE. Biogenic synthesis and cytotoxic effects of silver nanoparticles mediated by white rot fungi. Heliyon. 2021;7:e06470.10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06470Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Jha AK, Prasad K, Prasad K, Kulkarni AR. Plant system: nature’s nanofactory. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2009;73:219–23.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.05.018Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Alahmad A, Al-Zereini WA, Hijazin TJ, Al-Madanat OY, Alghoraibi I, Al-Qaralleh O, et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Hypericum perforatum L. aqueous extract with the evaluation of its antibacterial activity against clinical and food pathogens. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14:1104.10.3390/pharmaceutics14051104Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Mukaratirwa-Muchanyereyi N, Gusha C, Mujuru M, Guyo U, Nyoni S. Synthesis of Silver nanoparticles using plant extracts from Erythrina abyssinica aerial parts and assessment of their anti-bacterial and antioxidant activities. Results Chem. 2022;4:100402.10.1016/j.rechem.2022.100402Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Khan M, Karuppiah P, Alkhathlan HZ, Kuniyil M, Khan M, Adil SF, et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Juniperus procera extract: Their characterization, and biological activity. Crystals. 2022;12:420.10.3390/cryst12030420Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Fuloria NK, Fuloria S, Chia KY, Karupiah S, Sathasivam K. Response of green synthesized drug blended silver nanoparticles against periodontal disease triggering pathogenic microbiota. J Appl Biol Biotechnol. 2019;7:46–56.10.7324/JABB.2019.70408Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Jamdagni P, Khatri P, Rana JS. Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles from leaf extract of Elettaria cardamomum and their antifungal activity against phytopathogens. Adv Mater Proc. 2021;3:129–35.10.5185/amp.2018/977Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Usmani A, Mishra A, Jafri A, Arshad M, Siddiqui MA. Green synthesis of silver nanocomposites of Nigella sativa seeds extract for hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Nanomater. 2019;4:191–200.10.2174/2468187309666190906130115Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Sarsar V, Selwal MK, Selwal KK. Biofabrication, characterization and antibacterial efficacy of extracellular silver nanoparticles using novel fungal strain of Penicillium atramentosum KM. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2015;19:682–8.10.1016/j.jscs.2014.07.001Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Jha AK, Zamani S, Kumar A. Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Pteris vittata extract and their therapeutic activities. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2022;69:1653–62.10.1002/bab.2235Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Bar H, Bhui DK, Sahoo GP, Sarkar P, De SP, Misra A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using latex of Jatropha curcas. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2009;339:134–9.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2009.02.008Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Vanaja M, Rajeshkumar S, Paulkumar K, Gnanajobitha G, Malarkodi C, Annadurai G. Kinetic study on green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Coleus aromaticus leaf extract. Pelagia Res Libr. 2013;4:50–5.Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Abambagade AM, Belete Y. Antibacterial and antioxidant activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized using aqueous extract of Moringa stenopetala leaves. Afr J Biotechnol. 2017;16:1705–16.10.5897/AJB2017.16010Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Chowdhury S, Yusof F, Faruck MO, Sulaiman N. Process optimization of silver nanoparticle synthesis using response surface methodology. Procedia Eng. 2016;148:992–9.10.1016/j.proeng.2016.06.552Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Singh D, Rathod V, Ninganagouda S, Hiremath J, Singh AK, Mathew J. Optimization and characterization of silver nanoparticle by endophytic fungi penicillium sp. isolated from curcuma longa (Turmeric) and application studies against MDR E. coli and S. aureus. Bioinorg Chem Appl. 2014;2014:408021.10.1155/2014/408021Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Azarbani F, Shiravand S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles by Ferulago macrocarpa flowers extract and their antibacterial, antifungal and toxic effects. Green Chem Lett Rev. 2020;13:41–9.10.1080/17518253.2020.1726504Suche in Google Scholar

[48] Rautela A, Rani J. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Tectona grandis seeds extract: characterization and mechanism of antimicrobial action on different microorganisms. J Anal Sci Technol. 2019;10:1–10.10.1186/s40543-018-0163-zSuche in Google Scholar

[49] Tanase C, Berta L, Mare A, Man A, Talmaciu AI, Roșca I, et al. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous bark extract of Picea abies L. and their antibacterial activity. Eur J Wood Wood Prod. 2020;78:281–91.10.1007/s00107-020-01502-3Suche in Google Scholar

[50] Dada AO, Adekola FA, Dada FE, Adelani-Akande AT, Bello MO, Okonkwo CR, et al. Silver nanoparticle synthesis by Acalypha wilkesiana extract: phytochemical screening, characterization, influence of operational parameters, and preliminary antibacterial testing. Heliyon. 2019;5:e02517.10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02517Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[51] Seifipour R, Nozari M, Pishkar L. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tragopogon collinus leaf extract and study of their antibacterial effects. J Inorg Organomet Polym Mater. 2020;30:2926–36.10.1007/s10904-020-01441-9Suche in Google Scholar

[52] Ramesh AV, Devi DR, Battu GR, Basavaiah K. A Facile plant mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles using an aqueous leaf extract of Ficus hispida Linn. f. for catalytic, antioxidant and antibacterial applications. South Afr J Chem Eng. 2018;26:25–34.10.1016/j.sajce.2018.07.001Suche in Google Scholar

[53] Ismail M, Khan MI, Akhtar K, Khan MA, Asiri AM, Khan SB. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles: A colorimetric optical sensor for detection of hexavalent chromium and ammonia in aqueous solution. Phys E Low-Dimension Syst Nanostruct. 2018;103:367–76.10.1016/j.physe.2018.06.015Suche in Google Scholar

[54] Mohammadi F, Yousefi M, Ghahremanzadeh R. Green synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) using leaves and stems extract of some plants. Adv J Chem A. 2019;2:266–75.10.33945/SAMI/AJCA.2019.4.1Suche in Google Scholar

[55] Aslam M, Fozia F, Gul A, Ahmad I, Ullah R, Bari A, et al. Phyto-extract-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of sanvitalia procumbens, and characterization, optimization and photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes orange g and direct blue-15. Molecules. 2021;26:1–16.10.3390/molecules26206144Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[56] Sulaiman GM, Mohammad AAW, Abdul-Wahed HE, Ismail MM. Biosynthesis, antimicrobial and cytotoxic effects of silver nanoparticles using Rosmarinus officinalis extract. Dig J Nanomater Biostruct. 2013;8.Suche in Google Scholar

[57] Gou Y, Zhou R, Ye X, Gao S, Li X. Highly efficient in vitro biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Lysinibacillus sphaericus MR-1 and their characterization. Sci Technol Adv Mater. 2015;16:15004.10.1088/1468-6996/16/1/015004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[58] Ravichandran V, Vasanthi S, Shalini S, Ali Shah SA, Harish R. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Atrocarpus altilis leaf extract and the study of their antimicrobial and antioxidant activity. Mater Lett. 2016;180:264–7.10.1016/j.matlet.2016.05.172Suche in Google Scholar

[59] Mason C, Vivekanandhan S, Misra M, Mohanty AK. Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) extract mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles. World J Nano Sci Eng. 2012;2:47.10.4236/wjnse.2012.22008Suche in Google Scholar

[60] Hashemi Z, Ebrahimzadeh MA, Biparva P, Mortazavi-Derazkola S, Goli HR, Sadeghian F, et al. Biogenic silver and zero-valent iron nanoparticles by feijoa: biosynthesis, characterization, cytotoxic, antibacterial and antioxidant activities. Anti-Cancer Agents Med Chem (Former Curr Med Chem Agents). 2020;20:1673–87.10.2174/1871520620666200619165910Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] Hashem Z, Mohammadyan M, Naderi S, Fakhar M, Biparva P, Akhtari J, et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ferula persica extract (Fp-NPs): Characterization, antibacterial, antileishmanial, and in vitro anticancer activities. Mater Today Commun. 2021;27:102264.10.1016/j.mtcomm.2021.102264Suche in Google Scholar

[62] Logeswari P, Silambarasan S, Abraham J. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using plants extract and analysis of their antimicrobial property. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2015;19:311–7.10.1016/j.jscs.2012.04.007Suche in Google Scholar

[63] Kumar R, Roopan SM, Prabhakarn A, Khanna VG, Chakroborty S. Agricultural waste Annona squamosa peel extract: Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles. Spectrochim Acta – Part A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2012;90:173–6.10.1016/j.saa.2012.01.029Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[64] Masum MI, Siddiqa MM, Ali KA, Zhang Y, Abdallah Y, Ibrahim E, et al. Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Phyllanthus emblicafruit extract and its inhibitory action against the pathogen acidovorax oryzaestrain RS-2 of rice bacterial brown stripe. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:820.10.3389/fmicb.2019.00820Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[65] Sangaonkar GM, Pawar KD. Garcinia indica mediated biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles with antibacterial and antioxidant activities. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2018;164:210–7.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.01.044Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] Elamawi RM, Al-Harbi RE, Hendi AA. Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma longibrachiatum and their effect on phytopathogenic fungi. Egypt J Biol Pest Control. 2018;28:1–11.10.1186/s41938-018-0028-1Suche in Google Scholar

[67] Mohanta YK, Panda SK, Bastia AK, Mohanta TK. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from Protium serratum and investigation of their potential impacts on food safety and control. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1–10.10.3389/fmicb.2017.00626Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[68] Nguyen VP, Le Trung H, Nguyen TH, Hoang D, Tran TH. Synthesis of biogenic silver nanoparticles with eco-friendly processes using Ganoderma lucidum extract and evaluation of their theranostic applications. J Nanomater. 2021;2021:6135920.10.1155/2021/6135920Suche in Google Scholar

[69] Heydari R, Rashidipour M. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using extract of oak fruit hull (Jaft): Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxic effect on MCF-7 cells. Int J Breast Cancer. 2015;2015:846743.10.1155/2015/846743Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[70] Dangi S, Gupta A, Gupta DK, Singh S, Parajuli N. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous root extract of Berberis asiatica and evaluation of their antibacterial activity. Chem Data Collect. 2020;28:100411.10.1016/j.cdc.2020.100411Suche in Google Scholar

[71] Wei S, Wang Y, Tang Z, Hu J, Su R, Lin J, et al. A size-controlled green synthesis of silver nanoparticles by using the berry extract of Sea Buckthornand their biological activities. N J Chem. 2020;44:9304–12.10.1039/D0NJ01335HSuche in Google Scholar

[72] Muzaffar R, Azam M, Samra MM, Basra MAR. Green synthesis of citrus reticulata mediated silver. Preprints. 2018;2018110371.Suche in Google Scholar

[73] Vinodhini S, Vithiya BSM, Prasad TAA. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles by employing the Allium fistulosum, Tabernaemontana divaricate and Basella alba leaf extracts for antimicrobial applications. J King Saud Univ – Sci. 2022;34:101939.10.1016/j.jksus.2022.101939Suche in Google Scholar

[74] Prathna TC, Chandrasekaran N, Raichur AM, Mukherjee A. Biomimetic synthesis of silver nanoparticles by Citrus limon (lemon) aqueous extract and theoretical prediction of particle size. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2011;82:152–9.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.08.036Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[75] Singh H, Du J, Yi T-H. Green and rapid synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Borago officinalis leaf extract: anticancer and antibacterial activities. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2017;45:1310–6.10.1080/21691401.2016.1228663Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[76] Roy A. Agriculture NB-IT in, 2017 undefined. Qualitative analysis of phytocompounds and synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Centella asiatica. ResearchgateNet. 2017;1:88–95.Suche in Google Scholar

[77] Isaac RSR, Sakthivel G, Murthy C. Green synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles using Averrhoa bilimbi fruit extract. J Nanotechnol. 2013;2013:906592.10.1155/2013/906592Suche in Google Scholar

[78] Singh M, Renu, Kumar V, Upadhyay SK, Singh R, Yadav M, et al. Biomimetic synthesis of silver nanoparticles from aqueous extract of saraca indica and its profound antibacterial activity. Biointerface Res Appl Chem. 2021;11:8110–20.10.33263/BRIAC111.81108120Suche in Google Scholar

[79] Khan AU, Wei Y, Ahmad A, Haq Khan ZU, Tahir K, Khan SU, et al. Enzymatic browning reduction in white cabbage, potent antibacterial and antioxidant activities of biogenic silver nanoparticles. J Mol Liq. 2016;215:39–46.10.1016/j.molliq.2015.12.019Suche in Google Scholar

[80] Pirtarighat S, Ghannadnia M, Baghshahi S. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ocimum basilicum cultured under controlled conditions for bactericidal application. Mater Sci Eng C. 2019;98:250–5.10.1016/j.msec.2018.12.090Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[81] Karthik C, Suresh S, Sneha Mirulalini G, Kavitha SA. FTIR approach of green synthesized silver nanoparticles by Ocimum sanctum and Ocimum gratissimum on mung bean seeds. Inorg Nano-Metal Chem. 2020;50:606–12.10.1080/24701556.2020.1723025Suche in Google Scholar

[82] Elbeshehy EKF, Elazzazy AM, Aggelis G. Silver nanoparticles synthesis mediated by new isolates of Bacillus spp., nanoparticle characterization and their activity against Bean Yellow Mosaic Virus and human pathogens. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:453.10.3389/fmicb.2015.00453Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[83] Nasar S, Murtaza G, Mehmood A, Bhatti TM. Green approach to synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ficus palmata leaf extract and their antibacterial profile. Pharm Chem J. 2017;51:811–7.10.1007/s11094-017-1698-9Suche in Google Scholar

[84] Reddy NV, Li H, Hou T, Bethu MS, Ren Z, Zhang Z. Phytosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Perilla frutescens leaf extract: characterization and evaluation of antibacterial, antioxidant, and anticancer activities. Int J Nanomed. 2021;16:15.10.2147/IJN.S265003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[85] Thirunavoukkarasu M, Balaji U, Behera S, Panda PK, Mishra BK. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticle from leaf extract of Desmodium gangeticum (L.) DC. and its biomedical potential. Spectrochim Acta – Part A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2013;116:424–7.10.1016/j.saa.2013.07.033Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[86] Guidelli EJ, Ramos AP, Zaniquelli MED, Baffa O. Green synthesis of colloidal silver nanoparticles using natural rubber latex extracted from Hevea brasiliensis. Spectrochim Acta – Part A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2011;82:140–5.10.1016/j.saa.2011.07.024Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[87] Ali G, Khan A, Shahzad A, Alhodaib A, Qasim M, Naz I, et al. Phytogenic-mediated silver nanoparticles using Persicaria hydropiper extracts and its catalytic activity against multidrug resistant bacteria. Arab J Chem. 2022;15:104053.10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.104053Suche in Google Scholar

[88] Vidhu VK, Philip D. Spectroscopic, microscopic and catalytic properties of silver nanoparticles synthesized using Saraca indica flower. Spectrochim Acta Part A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2014;117:102–8.10.1016/j.saa.2013.08.015Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[89] Daphedar A, Taranath TC. Characterization and cytotoxic effect of biogenic silver nanoparticles on mitotic chromosomes of Drimia polyantha (Blatt. & McCann) Stearn. Toxicol Rep. 2018;5:910–8.10.1016/j.toxrep.2018.08.018Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[90] Ahmeda A, Zangeneh A, Zangeneh MM. Preparation, formulation, and chemical characterization of silver nanoparticles using Melissa officinalis leaf aqueous extract for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia in vitro and in vivo conditions. Appl Organomet Chem. 2020;34:e5378.10.1002/aoc.5378Suche in Google Scholar

[91] Baghani M, Es-Haghi A. Characterization of silver nanoparticles biosynthesized using Amaranthus cruentus. Bioinspired Biomim Nanobiomater. 2020;9:129–36.10.1680/jbibn.18.00051Suche in Google Scholar

[92] Zuverza-Mena N, Armendariz R, Peralta-Videa JR, Gardea-Torresdey JL. Effects of silver nanoparticles on radish sprouts: Root growth reduction and modifications in the nutritional value. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1–11.10.3389/fpls.2016.00090Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[93] Al-Zubaidi S, Al-Ayafi A, Abdelkader H. Biosynthesis, characterization and antifungal activity of silver nanoparticles by Aspergillus niger isolate. J Nanotechnol Res. 2019;1:23–36.10.26502/jnr.2688-8521002Suche in Google Scholar

[94] Hamelian M, Zangeneh MM, Amisama A, Varmira K, Veisi H. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Thymus kotschyanus extract and evaluation of their antioxidant, antibacterial and cytotoxic effects. Appl Organomet Chem. 2018;32:e4458.10.1002/aoc.4458Suche in Google Scholar

[95] El-Kemary M, Ibrahim E, Mohammad FAA, Khalifa SAM, Alanazi AD, El-Seedi HR. Calendula officinalis-mediated biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles and their electrochemical and optical characterization. Int J Electrochem Sci. 2016;11:10795–805.10.20964/2016.12.88Suche in Google Scholar

[96] Ayromlou A, Masoudi S, Mirzaie A. Scorzonera calyculata aerial part extract mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Evaluation of their antibacterial, antioxidant and anticancer activities. J Clust Sci. 2019;30:1037–50.10.1007/s10876-019-01563-2Suche in Google Scholar

[97] Abboud Y, Eddahbi A, El Bouari A, Aitenneite H, Brouzi K, Mouslim J. Microwave-assisted approach for rapid and green phytosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous onion (Allium cepa) extract and their antibacterial activity. J Nanostruct Chem. 2013;3:84.10.1186/2193-8865-3-84Suche in Google Scholar

[98] Khan M, Khan M, Adil SF, Tahir MN, Tremel W, Alkhathlan HZ, et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles mediated by Pulicaria glutinosa extract. Int J Nanomed. 2013;8:1507–16.10.2147/IJN.S43309Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[99] Huang J, Li Q, Sun D, Lu Y, Su Y, Yang X, et al. Biosynthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles by novel sundried Cinnamomum camphora leaf. Nanotechnology. 2007;18:1054.10.1088/0957-4484/18/10/105104Suche in Google Scholar

[100] Nagar N, Devra V. A kinetic study on the degradation and biodegradability of silver nanoparticles catalyzed Methyl Orange and textile effluents. Heliyon. 2019;5:e01356.10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01356Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[101] Mameneh R, Ghaffari-Moghaddam M, Solouki M, Samzadeh-Kermani A, Sharifmoghadam MR. Characterization and antibacterial activity of plant mediated silver nanoparticles biosynthesized using Scrophularia striata flower extract. Russ J Appl Chem. 2015;88:538–46.10.1134/S1070427215030271Suche in Google Scholar

[102] Khalil MMH, Ismail EH, El-Baghdady KZ, Mohamed D. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using olive leaf extract and its antibacterial activity. Arab J Chem. 2014;7:1131–9.10.1016/j.arabjc.2013.04.007Suche in Google Scholar

[103] El-Naggar NE-A, Hussein MH, El-Sawah AA. Bio-fabrication of silver nanoparticles by phycocyanin, characterization, in vitro anticancer activity against breast cancer cell line and in vivo cytotxicity. Sci Rep. 2017;7:10844.10.1038/s41598-017-11121-3Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[104] Mandal S, Marpu SB, Hughes R, Omary MA, Shi SQ. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Cannabis sativa extracts and their anti-bacterial activity. Green Sustain Chem. 2021;11:28–38.10.4236/gsc.2021.111004Suche in Google Scholar

[105] Kanniah P, Radhamani J, Chelliah P, Muthusamy N, Joshua Jebasingh Sathiya Balasingh E, Reeta Thangapandi J, et al. Green synthesis of multifaceted silver nanoparticles using the flower extract of Aerva lanata and evaluation of its biological and environmental applications. ChemistrySelect. 2020;5:2322–31.10.1002/slct.201903228Suche in Google Scholar

[106] Riaz Rajoka MS, Mehwish HM, Zhang H, Ashraf M, Fang H, Zeng X, et al. Antibacterial and antioxidant activity of exopolysaccharide mediated silver nanoparticle synthesized by Lactobacillus brevis isolated from Chinese koumiss. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2020;186:110734.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.110734Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[107] Khodadadi S, Mahdinezhad N, Fazeli-Nasab B, Heidari MJ, Fakheri B, Miri A. Investigating the possibility of green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Vaccinium arctostaphlyos extract and evaluating its antibacterial properties. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:5572252.10.1155/2021/5572252Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[108] Mohammed AE, Al-Qahtani A, Al-Mutairi A, Al-Shamri B, Aabed K. Antibacterial and cytotoxic potential of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles by some plant extracts. Nanomaterials. 2018;8:382.10.3390/nano8060382Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[109] Valli JS, Vaseeharan B. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by Cissus quadrangularis extracts. Mater Lett. 2012;82:171–3.10.1016/j.matlet.2012.05.040Suche in Google Scholar

[110] Singh A, Gaud B, Jaybhaye S. Optimization of synthesis parameters of silver nanoparticles and its antimicrobial activity. Mater Sci Energy Technol. 2020;3:232–6.10.1016/j.mset.2019.08.004Suche in Google Scholar

[111] Rasheed T, Bilal M, Iqbal HMN, Li C. Green biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves extract of Artemisia vulgaris and their potential biomedical applications. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2017;158:408–15.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.07.020Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[112] Pazos-Ortiz E, Roque-Ruiz JH, Hinojos-Márquez EA, López-Esparza J, Donohué-Cornejo A, Cuevas-González JC, et al. Dose-dependent antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles on polycaprolactone fibers against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. J Nanomater. 2017;2017:4752314.10.1155/2017/4752314Suche in Google Scholar

[113] Ouda SM. Some nanoparticles effects on Proteus sp. and Klebsiella sp. isolated from water. Am J Infect Dis Microbiol. 2014;2:4–10.10.12691/ajidm-2-1-2Suche in Google Scholar

[114] Jeevitha M, Rajeshkumar S. Antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized using marine brown seaweed Spatoglossum asperum against oral pathogens. Indian J Public Health. 2019;10:3569.10.5958/0976-5506.2019.04140.8Suche in Google Scholar

[115] Raut RW, Mendhulkar VD, Kashid SB. Photosensitized synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera leaf powder and silver nitrate. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 2014;132:45–55.10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.02.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[116] Shahverdi AR, Fakhimi A, Shahverdi HR, Minaian S. Synthesis and effect of silver nanoparticles on the antibacterial activity of different antibiotics against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Nanomed Nanotechnol Biol Med. 2007;3:168–71.10.1016/j.nano.2007.02.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[117] Abalkhil TA, Alharbi SA, Salmen SH, Wainwright M. Bactericidal activity of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles against human pathogenic bacteria. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2017;31:411–7.10.1080/13102818.2016.1267594Suche in Google Scholar

[118] Wei Z, Zhang C, Jia J, Niu W, Wei Y, Fu S, et al. A label-free Exonuclease I-assisted fluorescence aptasensor for highly selective and sensitive detection of silver ions. Spectrochim Acta Part A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2021;260:119927.10.1016/j.saa.2021.119927Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[119] Khorrami S, Zarrabi A, Khaleghi M, Danaei M, Mozafari MR. Selective cytotoxicity of green synthesized silver nanoparticles against the MCF-7 tumor cell line and their enhanced antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. Int J Nanomed. 2018;13:8013.10.2147/IJN.S189295Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[120] Das SS, Alkahtani S, Bharadwaj P, Ansari MT, ALKahtani MDF, Pang Z, et al. Molecular insights and novel approaches for targeting tumor metastasis. Int J Pharm. 2020;585:119556.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119556Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[121] Pareek V, Gupta R, Panwar J. Do physico-chemical properties of silver nanoparticles decide their interaction with biological media and bactericidal action? A review. Mater Sci Eng C. 2018;90:739–49.10.1016/j.msec.2018.04.093Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[122] Mohanaparameswari S, Balachandramohan M, Sasikumar P, Rajeevgandhi C, Vimalan M, Pugazhendhi S, et al. Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method. Green Process Synth. 2023;12:20230080.10.1515/gps-2023-0080Suche in Google Scholar

[123] Riaz Ahmed KB, Nagy AM, Brown RP, Zhang Q, Malghan SG, Goering PL. Silver nanoparticles: Significance of physicochemical properties and assay interference on the interpretation of in vitro cytotoxicity studies. Toxicol Vitr. 2017;38:179–92.10.1016/j.tiv.2016.10.012Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[124] Bedlovicová Z, Strapác I, Baláž M, Salayová A. A brief overview on antioxidant activity. Molecules. 2020;1–24.Suche in Google Scholar