Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

-

Mujahid Sher

, Ishtiaq Hussain

, Wiaam Mujahid Sher

Abstract

Herein, capsaicin nanoparticles (NPs) were prepared by two different methods, namely, evaporative precipitation of nanosuspension (EPN) and anti-solvent precipitation with a syringe pump (APSP). The nanoparticles of the necessary sizes were obtained after optimizing experimental parameters such as the solvent-to-anti-solvent ratio and stirring speed. They had spherical shapes and an average diameter of 171.29 ± 1.94 and 78.91 ± 0.54 nm when prepared using the EPN and APSP methods, respectively. Differential scanning calorimetry and an X-ray diffractometer showed that the capsaicin crystallinity decreased. FTIR results showed that the NPs were produced with their original configuration and did not result in the synthesis of any additional structures. The NP formulation had a desirable drug content. They surpassed the unprocessed drug in solubility and displayed the desired stability. Capsaicin NP cream showed many folds of enhanced analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial effects compared to unprocessed capsaicin.

1 Introduction

Capsaicin is obtained from the plant Capsicum annuum Linn, a member of the Solanaceae family. Capsaicin is a capsaicinoid; at room temperature, it is a crystalline to waxy solid compound [1]. It treats common medical conditions like pain and inflammation and has antimicrobial properties as well [1].

Researchers have been looking at capsaicin receptors, which are also called vanilloid receptors [transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 (TRPV1)], to find new analgesic drugs. Capsaicin is a well-described vanilloid ligand that acts as a potent TRPV1 agonist [2]. Its action on TRPV1 leads to desensitization, an extended refractory period during which no stimulus is recognized [3]. Capsaicin strongly influences the TRPV1 receptor and inhibits substance P, which is responsible for transmitting pain sensations. Less pain is experienced as substance P exhausts [4]. This knowledge resulted in the use of capsaicin as an analgesic to treat various painful conditions, and its topical application was established to treat not only various pain conditions but also clinical inflammation [5]. Wang et al. found that capsaicin activation of TRPV1 increased the production of nitric oxide and decreased inflammation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). Treatment with capsaicin also attenuated LPS-induced expression of endothelial adhesion molecules, activation of NF-κB, and monocyte adhesion in HUVECs: the effects that depend on the activation of TRPV1. Thus, capsaicin may decrease endothelial inflammation [6]. Significant pain reduction (57% in osteoarthritis patients and 33% in rheumatoid arthritis patients) has been documented using capsaicin cream in the subjects in a study [7]. Capsaicin has been used in the management of neuropathic discomfort, diabetic and HIV-caused neuropathy, post-herpetic neuralgia, chemotherapy-induced neuropathies, and other painful and inflammatory conditions [8,9,10,11].

Capsaicin can also inhibit clinically important microorganisms, and its prospective antimicrobial effect in the food industry as a substitute for artificial preservatives is also being investigated [12]. It has long been employed as a preservative component in food preparations due to its antimicrobial potential and as an active ingredient in packaging film and functional foods [13]. The antioxidant effects of capsaicin are also considered beneficial in the food matrix. The balance of the intestinal flora and human health are intimately related, and capsaicin has been found to affect the overall conformation of the intestinal flora by causing it to be more evenly distributed. Findings from a study suggest that after capsaicin consumption, the Helicobacter content decreased in the intestinal flora compared to the control. Therefore, capsaicin could decrease the probability of diseases produced by this bacteria [14]. Its antibiofilm action against some microorganisms has also been confirmed, as has its ability to reduce the infectious phenotypes of bacteria controlled by quorum sensing [15]. Capsaicin-loaded silver nanoparticles, considered an unconventional antimicrobial agent, exhibited potent antibacterial activity in research. It demonstrated significant antimicrobial action, indicating that such nanoparticles can treat infections caused by susceptible microorganisms [16].

Currently, the pharmacological treatment for neuropathic pain is focused on symptomatic relief with pharmacotherapy, topical analgesics, or other interventions. The response to which is only a modest symptom relief. Therefore, a better treatment approach to neuropathic pain is greatly needed.

During the past few decades, an ample variety of biological effects of capsaicin have been evaluated. Previous research suggests the positive effects of capsaicin on pain relief and cognitive impairment. Capsaicin has great potential for becoming a first- or second-line treatment for neuropathic pain, and for becoming a therapeutic option for many other pain-related disease states [17].

Topical capsaicin in low concentrations (0.025–0.075%) also has moderate efficacy in the topical treatment of peripheral neuropathic pain. However, capsaicin 8% dermal patch is as effective in reducing pain intensity as other centrally active agents (i.e., pregabalin). Studies have reported fewer systemic side effects with capsaicin use, a faster onset of action, and superior treatment satisfaction compared with systemic agents. Patients reported limited serious adverse effects (6% compared to 4% with the control) [18]. The most common adverse reactions were application site reactions, such as dryness, erythema, edema, pain, and pruritus, which were mild to moderate in severity and resolved spontaneously within 7 days and did not preclude the completion of the treatment (99% of the patients completed ≥90% of the treatment). Researchers also reported that capsaicin has additional advantages, such as good systemic tolerability, the possibility of combining it with other agents, and a good cost-effective profile [18].

The above discussion advocates that capsaicin has a significant potential to cure pain and inflammation and may also be utilized as an antimicrobial agent. However, low aqueous solubility and insufficient bioavailability limit capsaicin’s therapeutic usefulness like other low water-soluble compounds [19]. We are unable to utilize capsaicin to its actual potential. This issue calls for preparations such as nanoformulations that can enhance capsaicin solubility and absorption and, ultimately, optimize its bioavailability in the body [20]. Nanoformulations exhibit unique physicochemical properties and can enhance compounds’ bioavailability and activity (Scheme 1) [19,20].

Chemical structure of capsaicin.

As a way to improve the therapeutic potential of pharmacological moieties while addressing concerns with poor water solubility and limited absorption, the use of nanoparticles (NPs) has grown over the past several years [21]. Many important drug classes have already undergone testing by various methods to produce drug NPs [22]. Silibinin and berberine NPs have been produced using anti-solvent precipitation with a syringe pump technique. The nanodrugs showed better in vivo bioavailability and hepatoprotective effects than their unprocessed forms [23,24]. Likewise, nanocurcumin (curcumin NPs) produced by evaporative precipitation of nanosuspension has been examined and compared with unprocessed curcumin with promising results [25]. However, to fully utilize the immense potential of this priceless drug, there is a significant gap that requires our attention and the need to make attempts to increase capsaicin solubility and bioavailability.

This study employs affordable, simple, quick, and reproducible APSP and EPN procedures for producing capsaicin nanoparticles. A study of this nature has never before been conducted. Upon conversion to NP form, it is anticipated that capsaicin’s activities will advance and it will be better able to exert its analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties.

2 Experimental

PCSIR Peshawar provided capsaicin for this study. Ethanol, HCl, DMSO, and n-hexane were purchased from BDH. Rats were bought from the NIH in Islamabad, and rabbits from the nearby market.

2.1 Fabrication of nanoparticles

Two separate methods were employed for the preparation of capsaicin NPs.

2.1.1 Preparation of NPs and optimization of experimental conditions through the EPN technique

To fabricate nanoparticles according to the EPN method, methanol was used as solvent and n-hexane as antisolvent. The saturated capsaicin solution was prepared in methanol, which was quickly added to n-hexane that resulting in nanoparticle formation. Solvent and antisolvent phases were mixed with continuous stirring. To obtain nanoparticles, the resulting mixtures were evaporated with help of a rotary evaporator operating under a vacuum pump [26]. In order to acquire the best nanoparticles in terms of sizes, zeta potential, and polydispersity index (PDI), important experimental conditions like stirring speed, and solvent antisolvent ratios were optimized during different experiments of nanoparticle preparation process [27].

Stirring Speed was assessed between 1,500 and 3,000 rpm (Table 1). A stirring speed of 3,000 rpm was recorded as the optimum stirring speed required to prepare nanoparticles with the desired features. The solvent antisolvent ratios were held constant while optimizing the stirring speed. As we increased the stirring speed, the particle size reduced.

Experimental conditions optimization in EPN method

| Sample | Stirring speed (rpm) | Solvent:antisolvent ratio |

|---|---|---|

| CP-EPN-1 | 1,500 | 1:20 |

| CP-EPN-2 | 2,000 | 1:20 |

| CP-EPN-3 | 2,500 | 1:20 |

| CP-EPN-4 | 3,000 | 1:20 |

| CP-EPN-5 | 3,000 | 1:15 |

| CP-EPN-6 | 3,000 | 1:10 |

| CP-EPN-7 | 3,000 | 1:10 |

| CP-EPN-8 | 3,000 | 1:10 |

CP-EPN = Capsaicin nanoparticles prepared by the EPN method.

As the solvent antisolvent ratio is important and can impact the size of the nanoparticles, we also optimized this ratio. The ratios for solvent and antisolvent were assessed from 1:20 to 1:10 (Table 1) while maintaining the speed of stirring constant [27,28,29,30]. As we increased the solvent antisolvent ratio, the sizes of drug particles drastically reduced.

2.1.2 Preparation of NPs and optimization of experimental conditions through the APSP technique

According to the APSP approach, the unprocessed compounds were rendered soluble in ethanol before being delivered into the antisolvent phase. The solution was filled in a syringe and immediately introduced into a certain volume of n-hexane (the antisolvent) with a 2 mL·min−1 flow rate and continuous stirring throughout the process. The nanoparticles were obtained by evaporating the resulting nanosuspension with the help of a rotary evaporator [26]. In order to acquire nanoparticles possessing the best features, important parameters during the nanoparticle preparation process, like stirring speed and solvent antisolvent ratios, were optimized [27], as discussed earlier. The optimized stirring speed and solvent-to-antisolvent ratio were selected, which resulted in the preparation of nanoparticles of the required size and shape (Table 2) [28,29,30].

Experimental conditions optimization in APSP method

| Formulation | Stirring speed (rpm) | Solvent:Antisolvent ratio |

|---|---|---|

| CP-APSP-1 | 1,500 | 1:20 |

| CP-APSP-2 | 2,000 | 1:20 |

| CP-APSP-3 | 2,500 | 1:20 |

| CP-APSP-4 | 3,000 | 1:20 |

| CP-APSP-5 | 3,000 | 1:15 |

| CP-APSP-6 | 3,000 | 1:10 |

| CP-APSP-7 | 3,000 | 1:10 |

| CP-APSP-8 | 3,000 | 1:10 |

CP-EPN = Capsaicin nanoparticles prepared by the EPN method.

2.2 Assay of CP-APSP

Capsaicin NPs were dissolved in 2.0 mL of acetonitrile to make a 2 mg·mL−1 stock solution and filtered with a syringe filter with a 0.45-μm bore. As necessary, dilute the capsaicin NP stock solution. The dilutions were measured for capsaicin at “ʎ max” 224 nm with a spectrophotometer. The amount of capsaicin was determined based on the absorbance values of known standard solutions. The same procedure was adopted for the preparation of a standard solution of capsaicin. The experiments were carried out in triplicate.

2.3 Characterization

The prepared NPs were characterized using modern characterization techniques.

2.3.1 Analysis by scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

In this research work, JOEL JSM-5910, Tokyo, Japan, was employed to obtain electron micrographs of samples. The foundation of SEM is light reflection. Electrons are reflected when incident light contacts the sample’s surface. These reflected electrons are drawn to a detector, where an algorithm transforms them into pictures. Varying accelerating voltages and magnifications were used to attain the requisite micrograph resolution. We applied a few sample droplets to the instrument’s metallic stub using double-sided adhesive tape and vacuum-dried it for analysis. During the analysis, the system’s working voltage stayed at 30 mA for 2 min, while the accelerating voltage stood at 20 kV.

2.3.2 Analysis by zeta sizer

The Malvern Instruments, UK, Nano series ZS 90, regarded as an ideal analysis tool, was used for measuring particle size, polydispersity index, and zeta potential. A key component of zeta-sizer analysis is the measurement of variations in the intensity of scattered light due to random particle movement. This method can measure particles between three nanometers and 3µm in size. NPs are supplied with ultra-pure water while the system temperature is 25°C to obtain the proper scattering intensity for analysis. Before analysis, we dispersed the samples well in the aqueous medium with ultrasonication. Varying accelerating voltages and magnifications were used to attain the requisite micrograph resolution. NP samples were introduced to a specifically developed cuvette with the help of a micropipette for analysis.

2.3.3 Analysis by X-ray diffraction (XRD)

An XRD can show if a substance is crystalline or amorphous. PANalytical X’Pert Pro was used to get the XRD pattern of capsaicin and its nanoparticles. The NP sample holders are made of silicon; a plastic sample holder is employed for the unprocessed drug. The machine is set to a 40-kV voltage and an operating current of 30 mA. Angles of 5° and 40°, respectively, are chosen as the initial and final angle points at 2θ. Throughout the procedure, each step’s size and duration are 0.02 and 0.5 s, respectively [31].

2.3.4 Analysis by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

Mettler Toledo 822e (Greifensee, Switzerland) was used to conduct DSC investigations for all the samples. It is used to assess the effects of particle size reduction on the drug’s thermal kinetics. A comparison of the enthalpy (∆H) of the original sample and its corresponding NPs yields information about the drug’s crystallinity. For this procedure, 5 mg of each sample was put separately in an aluminum pan in the sample chamber for analysis. An unfilled pan (having no sample) was also used as a reference. The temperature of the pans was increased by 10°C·min−1 between 60 and 200°C while exposed to nitrogen gas flow at 40 mL per minute [32].

2.3.5 Analysis by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

This technique identifies potential interactions between the drug and the excipients used to prepare the nanoparticles. Shimadzu IR Prestige-21 FTIR, Kyoto, Japan, was employed in the current research work, collecting the spectra between 4,000 and 400 cm−1.

In order to produce translucent discs that can be placed in a sample container and analyzed, they are prepared by combining 200–300 mg of potassium bromide (KBr) with 2–3 mg of the test specimen and compressing it with a compression machine. The component compatibility of nanoparticles is determined by matching the nanoparticle peaks and patterns to those of the unprocessed drugs.

2.3.6 Spectrophotometric analysis

Pharma Spec 1700, Shimadzu Tokyo, Japan, was utilized to calculate the percent dissolution and solubility and conduct content analysis. The analysis was performed at the “ʎ max” 224 nm for capsaicin in this study after the sample, and reference standards had been diluted.

2.4 Solubility study

For the solubility study, 1 mg of capsaicin and its nanoparticles was separately dissolved in distilled water. The solution was agitated for one hour at 100 rpm and kept at 37°C ± 0.5. Using Whatmann filter paper with a 0.2 μm pore size, the samples were filtered and examined at 224 nm [33].

2.5 Dosage form formulation

Capsaicin NPs, weighing 0.075 g, formulated a topical capsaicin cream. They were thoroughly combined with a cream base to produce a finished product containing 0.075% (w/w) capsaicin. The cream base contained beeswax, liquid paraffin, cholesterol, and soft paraffin. The pH of cream formulations was adjusted to 6.5.

2.6 In vitro release analysis of capsaicin

Drug release from capsaicin topical cream was studied using the Vertical Franz Diffusion Cell. In this technique, molecules selectively diffuse across a semi-permeable membrane to separate, based on their sizes. The receptor compartment was filled with PBS (pH 7.4) and clamped. Known amounts of unprocessed capsaicin and nanoparticle cream were introduced separately in the donor space. The media temperature in the receptor compartment was held at 32 ± 0.5°C and stirred at 100 rpm. Aliquots of 1 mL were collected at hourly intervals of 1–24 h and scanned with a spectrophotometer at 224 nm. The percentage drug release of CP-APSP topical cream was calculated [33]. Each test was performed in triplicate.

2.7 Stability study

Storage stability testing was carried out on NPs in a stability chamber. Different aspects of NPs that could affect their stability were carefully monitored and examined throughout the storage experiment at different preplanned time intervals. To measure their stability during storage, the NPs were checked at temperatures ranging from 5 to 45°C, at pH ranges from acidic to basic (1–9 on the Sorenson scale), and the nanoparticle stability was also checked when stored at pH 6.5 and 25°C for different periods and checked for stability at intervals of days 1, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180. Sample lots were labeled and tested to find optimum solubility, and examine particle size, diameter, and polydispersity indices.

2.8 Ex-vivo permeation study capsaicin

This study was performed in a Franz diffusion cell (Kesary Chein Diffusion Cell, China) [34]. The surface of the receptor compartment was covered with rabbit skin, placed on a magnetic stirrer, and submerged in phosphate buffer (pH of 7.4). The swirling speed was fixed at 150 rpm and the temperature at 35 ± 2°C. The donor compartment received a specified dosage of CP-APSP cream. The receptor compartment was sampled with a 1 mL sample, and we kept replacing it with phosphate buffer. There were 12 hours of scheduled sample collections, which a spectrophotometer examined at 224 nm [33]. After the investigation, the drug residue on the skin was determined. UV–Vis analysis was used to find drugs on and in the skin [33]. The experiments were carried out in triplicate.

2.9 Anti-inflammatory activity

Healthy Wistar albino rats weighing 200–220 G were kept in standardized environmental conditions. Before beginning the trial, the rats were given a 7-day laboratory acclimatization period and split into three similar groups: A, B, and C, with no differences among the various groups. The carrageenan-induced paw edema test assessed and compared the inflammation control potential of unprocessed capsaicin and its NPs [35]. Topical pretreatment was carried out on the right hind paws of the animals for 2.5 h, and later, they were injected with intraplanar injections of 0.1 mL·paw−1 of carrageenan, which was noted as time zero. The circumferences of the paws were measured repeatedly for 6h at hourly intervals and compared among the groups. The equation given (Eq. 1) was used to calculate the inflammation:

2.10 Analgesic activity

This experiment was conducted using a hot plate [36]. Eighteen male Wistar albino rats weighing 200 ± 20 g were employed, randomly split into three equal groups with no noteworthy differences. Before the experiment, topical pretreatment was carried out for 2.5 h with different cream formulations on the animal’s hind paws. The reaction times to the hot plate test were measured before and after the administration of drugs to find and compare the effects of each sample separately. After the responses were recorded, the rat was immediately removed from the hot surface to prevent any possible tissue damage.

2.11 Antimicrobial activity

The antimicrobial potential of the NPs and their respective unprocessed drugs were separately investigated against selected bacteria and fungi.

2.11.1 Antibacterial activity

The clinical isolates for antimicrobial investigation were obtained from the Microbiology Department, AUST Abbottabad. They were subcultured in nutrient agar (NA) for 48 h at 37°C. The antibacterial activity of the given samples was estimated through the paper disc diffusion method. The cultures were set at 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard before their inoculation onto NA dishes having a diameter of 15 cm. Each sample was independently diluted with DMSO to the desired concentration. Sterile filter paper discs of 6 mm diameter, impregnated with 50 µl of sample dilutions prepared in DMSO, were applied to every cultured dish previously inoculated with 0.5 McFarland bacterial cultures. Later, these cultures were incubated at 37°C for 18 h. Similarly, ciprofloxacin or DMSO-impregnated paper discs were also used in the experiment as the positive and negative controls, respectively. A digital Vernier caliper was used to measure and determine the millimeter size of the zone of inhibition surrounding each paper disc to estimate the antibacterial potential of the samples following incubation [37]. Each test was performed in triplicate.

2.11.2 Antifungal activities

The antifungal action of the NPs and the respective unprocessed drug was also separately evaluated against selected fungal isolates. Cultures of selected strains were adjusted to a concentration of 106 cfu·mL−1 and inoculated in Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) dishes. Sterile filter paper discs of 15 mm diameter, impregnated with 50 µL of sample dilutions already prepared in DMSO, were applied to every cultured dish now inoculated with 106 cfu·mL−1 of fungal cultures.

Candida albicans cultures were incubated for 18 h at 37°C, while the other strains were incubated for 48 h at 31 ± 1°C. Paper discs impregnated with amphotericin B and DMSO were used as the positive and negative controls, respectively. The zone of inhibition was measured for each paper disc to evaluate the antibacterial activity [37]. Three replication experiments for each organism in each sample were carried out.

2.11.3 Determination of MIC and MBC/MFC

The sample MIC was assessed for every test organism in triplicate. A loopful of the organisms to be tested, previously diluted to 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard (in the case of bacteria) or 106 cfu·mL−1 (in the case of fungi), was added to test tubes after 0.5 mL of the desired sample concentration was mixed with 2 mL of nutrient broth. The same method was followed to test the organisms with positive and negative controls (ciprofloxacin and DMSO, respectively, for bacterial isolates and amphotericin B in the case of fungi). Tubes of bacterial isolates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h, whereas those with fungal isolates were incubated at 31 ± 1°C for 48 h. At the end of the period of incubation, the tubes were looked at for turbidity to note the growth of the microorganisms.

To estimate MBC, a loopful of broth from the tubes used to determine the MIC was taken from those that showed no growth and streaked on sterile NA and SDA for bacteria or fungi, respectively. Bacteria-inoculated petri dishes were incubated at 37°C for 24 h, and those inoculated with fungi were kept for 48 h at 31 ± 1°C. After incubation, the sample concentration that allowed no visible growth was noted as MBC or MFC for bacteria or fungi, respectively [37].

-

Ethical approval: The research related to animals’ use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations and institutional policies for the care and use of animals.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Fabrication of NPs

The current research aimed to prepare capsaicin nanoparticles using EPN and APSP techniques to enhance their solubility, absorption, and bioavailability. In the EPN method, when the conditions of a stirring speed of 3,000 rpm and the solvent anti-solvent ratio of 1:10 were fulfilled, particles with an average size of 171.29 ± 1.94 nm were acquired. The APSP method produced outstanding results, and we obtained nanoparticles with 78.91 ± 0.54 nm average sizes. The stirring speed and solvent anti-solvent ratios can affect the sizes of nanoparticles; therefore, these parameters have been optimized, and the best solvent anti-solvent ratio of 1:10 and best stirring speed of 3,000 rpm have been noted as suitable conditions for best results.

According to characterization results, the APSP technique produced particles with the lowest diameters and the narrowest particle size distribution. These results contrast those obtained from the EPN method, which produced nanoparticles of lower quality with irregular and larger sizes. By considering particle sizes, zeta potential, and morphology, particles prepared following the APSP procedure proved the best. In solubility and dissolution experiments, the nanoparticles made using the APSP approach also outperformed those made with the EPN method. Thus, the nanoparticles produced by the APSP approach were chosen for additional research and employed to carry out the scheduled activities.

3.2 Characterization of the nanoparticles

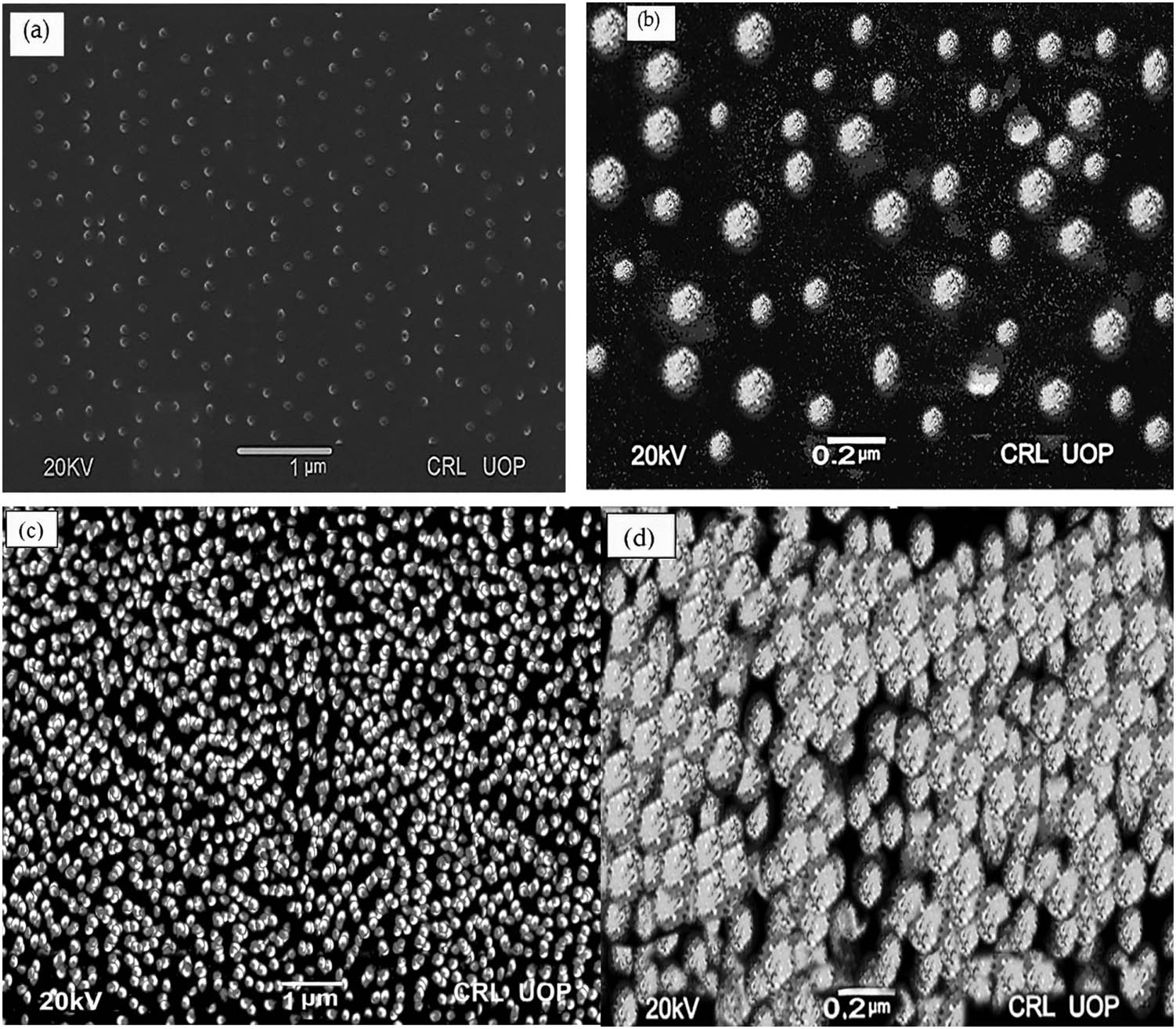

3.2.1 Characterization by scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The morphology of the nanoparticles synthesized by both methods, the APSP and EPN, was investigated using SEM, and the pictographs were recorded. The SEM images reveal that the synthesized nanoparticles exhibit predominantly spherical shapes. The obtained results from SEM analysis for both types of capsaicin nanoparticles are displayed in Figure 1(a)–(d). The white dots in Figure 1(a) and (b) represent nanoparticles prepared by the APSP method (CP-APSP). CP-APSP has a strict size distribution, with the average size being 78.91 ± 0.54 nm. They are evenly distributed and do not agglomerate. The characterization results for the capsaicin nanoparticles prepared using the EPN method (CP-EPN) show that they have an average particle size of 171.29 ± 1.94 nm, have an extensive size distribution, and are lumped together, as evident from the white dots shown in Figure 1(c) and (d). In contrast to those made using the APSP approach, the EPN method produced nanoparticles that are not homogenous and present a bunch-like appearance (Figure 1(c) and (d)) due to lumping together.

SEM Pictographs of capsaicin nanoparticles prepared by (a and b) APSP Method (CP-APSP) and (c and d) EPN Method (CP-EPN).

With the reduction in their sizes, the surface area of the nanoparticles significantly increases. Enhancing the surface area of the nanoparticles can increase their wettability, solubility, absorption rate, and associated oral bioavailability [38]. A drugs’ particle size affects its distribution, release kinetics, and, especially in the case of medicines applied topically, its intended penetration. Surface area, surface free energy, dissolubility, and release rate increase when particle size is reduced. Together, all these elements improve a drug’s bioavailability and, hence, its pharmacological effects.

3.2.2 Characterization by zeta sizer

According to Zeta Sizer analysis, the PDI of CP-APSP is 0.214 ± 0.02, and its Zeta potential is −28.9 ± 0.8 mV, as shown in Table 3. The PDI value, less than 0.50, shows even particle sizes. The produced nanoparticles, particularly those synthesized by the APSP method, have PDI and zeta potential values within the desired range. The information obtained from the Zeta Sizer and SEM analyses is encouraging. The zeta potential indicates the stability of formulations, and in the case of the APSP method, a zeta potential value of −28.9 ± 0.8 mV (Table 3) and the resulting repulsive force indicate stable nanoparticles, as also previously reported [39].

Particle size, zeta potential, and PDI of SM-APSP and CP-APSP

| Formulations | Average size of particles (nm) | Zeta potential (mV) | PDI |

|---|---|---|---|

| CP-APSP | 78.91 ± 0.54 | −28.9 ± 0.8 | 0.214 ± 0.02 |

3.2.3 Characterization by X-ray diffractometer

XRD Pictographs of unprocessed capsaicin and CP-APSP are presented in Figure 2. According to the pictographs, the XRD analysis of unprocessed capsaicin in Figure 2(a) reveals sharp diffraction peaks at 2θ of 8.6°, 9.1°, 12.9°, 16.2°, 20.9°, 25.4°, and 30.1°, demonstrating that unprocessed capsaicin is present in a crystalline state. On the other hand, XRD analysis of CP-APSP Figure 2(b) reveals diffraction peaks with reduced sharpness, demonstrating a decrease in crystallinity. The reduced intensity in the diffraction peaks is a feature of the reduced crystallinity of the compounds [40]. Therefore, the XRD analysis validates the reduction in crystallinity and the samples’ conversion to an amorphous form.

X-ray diffractogram of (a) unprocessed capsaicin and (b) CP-APSP.

By transforming substances into an amorphous state, they become more soluble, increasing their bioavailability. Therefore, the best method to increase a drug’s solubility, dissolution, absorption, and bioavailability is to modify its crystallinity by scaling it down to nanoscale size [41].

3.2.4 Characterization by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

The scans obtained during the DSC analysis are shown in Figure 3. The DSC analysis also confirms a shift in crystallinity and a transition to an amorphous state. Because of the decreased crystallinity of the nanoparticles, there is a slight expansion in the peak at the melting point of the CP-APSP (Figure 3). CP-APSP demonstrated a melting point of nearly 63°C (Figure 3) in contrast to the unprocessed capsaicin’s melting peak at 66°C, which can be ascribed to the conversion of the drug to an amorphous form and is consistent with previous reports [33,42]. Converting a compound to a less crystalline state with nanometer-sized particles is the best approach to augmenting the drugs’ solubility and dissolution and increasing their bioavailability. More crystalline materials have higher enthalpy (ΔH) values, while amorphous materials have lower enthalpy values, smaller particle sizes, and a greater surface area than the unprocessed compounds [43]. In contrast to crystalline materials, amorphous materials have higher free energy and are efficiently soluble.

Differential scanning calorimetry of unprocessed capsaicin and CP-APSP.

3.2.5 Characterization by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The unprocessed capsaicin and the CP-APSP samples underwent FTIR analysis, as shown in Figure 4(a) and (b). The results from FTIR analysis revealed no appreciable alterations in the spectrum. The results show that the chemical compositions of the samples of unprocessed capsaicin (Figure 4(a)) and CP-APSP (Figure 4(b)) are very similar. The intermolecular interactions determine the vibrational changes in the materials. The investigation points toward a spectrum with many peaks of changeable intensities due to vibrational fluctuations representing different functional groups. The FTIR analysis (Figure 4) confirms that no new complex development has occurred within the constituent parts of the CP-APSP. Fabricated nanoparticles of capsaicin still have their structural integrity.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, spectra of (a) unprocessed capsaicin and (b) CP-APSP.

In the FTIR range, characteristic peaks of unprocessed capsaicin and CP-APSP seen at 700–1,300 cm−1 represent skeletal C–C vibrations: 1,103.280 cm−1 (C–O), 1,597.06 cm−1 and 1,504.48 cm−1 (aromatic C═C stretch), 1,504.48 cm−1 (skeleton vibration of aromatic C═C ring stretch), 1,386.82 cm−1 and 1,361.74 cm−1 (C═C stretch), 1,276.88 cm−1 (C–O–C stretching), and 1,035.77–1,184.29 cm−1 (in-plane═C–H bending).

3.3 Assay of prepared nanoparticles

The drug content results of capsaicin are presented in Table 4 (96.74% for unprocessed capsaicin and 99.11% for CP-APSP), respectively. The results fall within the allowed limits of 90–110% required for pharmaceuticals.

Percent drug content of unprocessed capsaicin and CP-APSP

| S. no. | Product | Result (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unprocessed capsaicin | 96.74 |

| 2 | CP-APSP | 99.11 |

3.4 Solubility studies

According to Figure 5, the aqueous solubility of CP-APSP was recorded as 54.18 µg·mL−1, and that of unprocessed capsaicin was 27.96 µg·mL−1. We can see an apparent enhancement in the solubility of CP-APSP (Figure 5). It is attributed to the conversion of capsaicin to nanoform, which increases the surface area and wetting of the drug, decreases crystallinity, and enhances the dissolvability and rate of release of the drug [38,41].

Solubility comparison of unprocessed capsaicin and CP-APSP.

3.5 In vitro release study of capsaicin cream

The release pattern of unprocessed capsaicin shows slow and insufficient drug release from capsaicin cream compared to CP-APSP (Table 5). The slow release of capsaicin from the unprocessed drug is due to the larger particle size. On the other hand, 92.432 ± 2.47% of capsaicin was released from the CP-APSP cream during the experiment. The drug release analysis reveals that converting capsaicin to nanoform enhances the release of capsaicin. Enhanced pharmacological effects of capsaicin are possible if the drug permeates into the skin in more significant amounts and is retained in the affected areas. Larger particles of unprocessed capsaicin have lower water solubility and slow dissolution, which is responsible for less permeation of the drug particles, and other researchers have also reported that [44].

Pattern of drug release from unprocessed capsaicin and CP-APSP creams

| Time (hours) | Unprocessed capsaicin cream | CP-APSP cream |

|---|---|---|

| (% of drug released) | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 3.862 | 9.113 |

| 2 | 6.324 | 17.342 |

| 3 | 9.984 | 28.875 |

| 4 | 12.124 | 35.981 |

| 6 | 15.958 | 42.590 |

| 8 | 18.898 | 50.998 |

| 10 | 21.989 | 59.876 |

| 12 | 25.841 | 65.291 |

| 14 | 29.214 | 74.989 |

| 16 | 33.989 | 78.140 |

| 18 | 36.467 | 82.948 |

| 20 | 38.784 | 85.538 |

| 22 | 39.421 | 89.105 |

| 24 | 39.923 | 92.432 |

3.6 Stability studies

Drug stability is crucial in drug development, transportation, and long-term storage procedures. The stability of the nanoparticles was tested at various pH and temperature levels and storage periods, revealing their continued stability across a wide temperature and pH range. The favorable conditions for their storage were recorded, and the nanoparticles that proved the most stable were set aside for further studies.

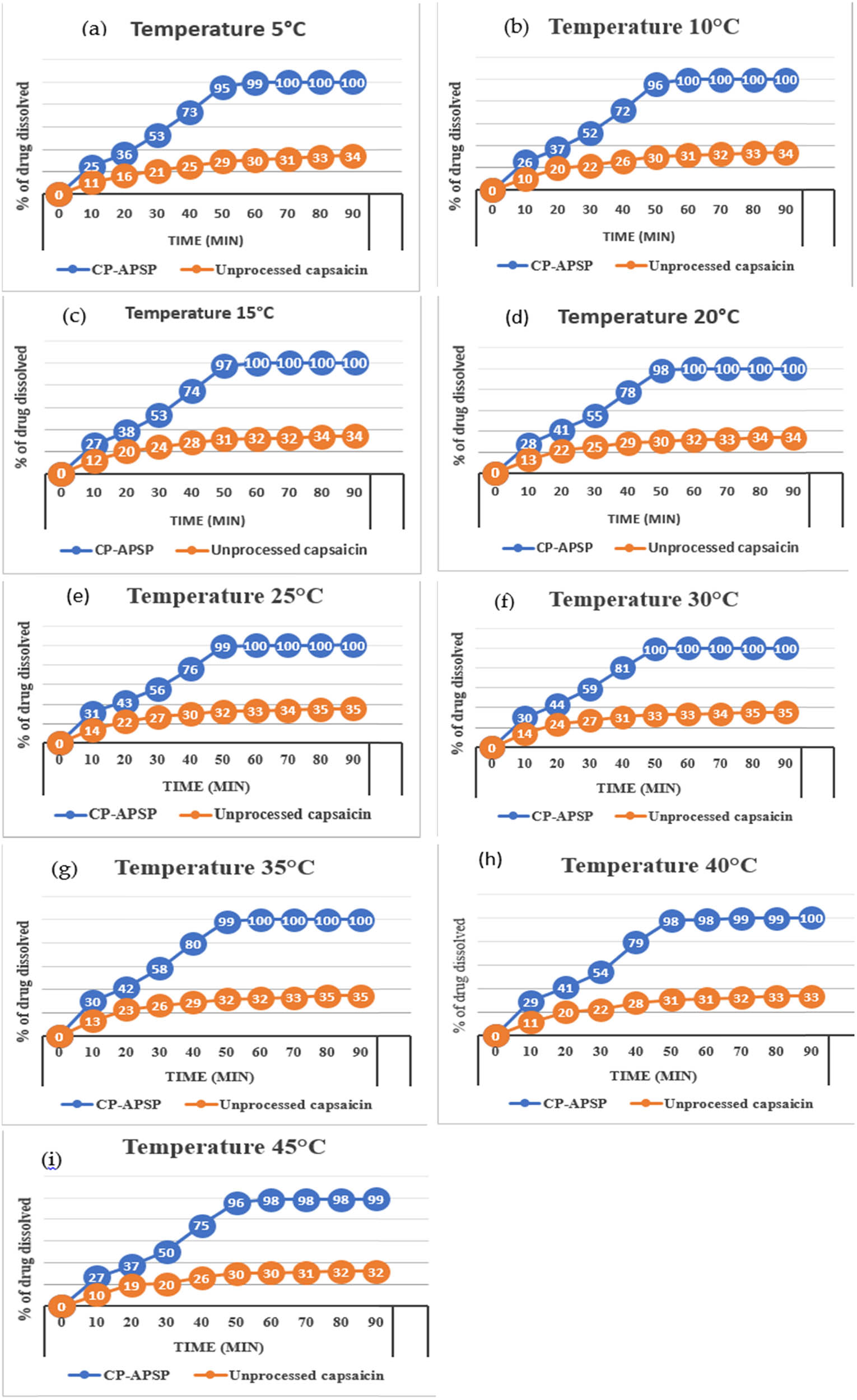

Figure 6 shows that samples stored at 5–30°C showed superior stability compared to those stored at 40°C and above. Data from the unprocessed capsaicin and CP-APSP at 5°C in the first 30 min showed a 20.76% and 51.462% dissolution, respectively (Figure 6(a)). Those stored at 25°C dissolved 58.492% in the first 30 min. During the period, nanocapsaicin’s particle sizes and dissolution rates remained unchanged, with slight variations in dissolution when stored at the highest and lowest temperature limits. Nanoparticles exhibited the desirable level of stability, notwithstanding minor changes in certain instances, like a slight lumping effect observed in the samples stored at 40°C or above. Such samples showed slightly lower rates of dissolution due to aggregation. It has already been reported that the lots stored at 5–30°C demonstrate excellent dissolution profiles [45]. The experiment proved that the preferred temperature for storing capsaicin nanoparticles is 5–30°C.

Dissolution Pattern of unprocessed capsaicin and CP-APSP, stored at different temperatures: (a) 5°C, (b) 10°C, (c) 15°C, (d) 20°C, (e) 25°C, (f) 30°C, (g) 35°C, (h) 40°C, and (i) 45°C.

Because the pH of a compound may affect its stability during storage [46], nanoparticles were also monitored at a pH range of 1–9 on the Sorenson scale. Figure 7(a)–(e) presents stability study results at different pHs. There were no significant differences in dissolution rate and particle size diameters among nanoparticles stored at pH 5–7 (Figure 7(c) and (d)). The results suggest homogeneous nanoparticles. However, they become slightly clumped when the pH moved from 5 to 1 or 7 to 9. The nanoparticles became micrometric and heterogeneous as soon as the lumping effects happened under unfavorable pH conditions. The dissolution behavior of the nanoparticles also changed, showing slightly slower and incomplete dissolution, as reported previously [47]. Conversely, the samples held at pH 5–7 for 24 weeks showed excellent stability. A capsaicin topical cream’s pH range of 5–7 is beneficial as it does not cause skin irritation.

Dissolution pattern of unprocessed capsaicin and CP-APSP at different pH.

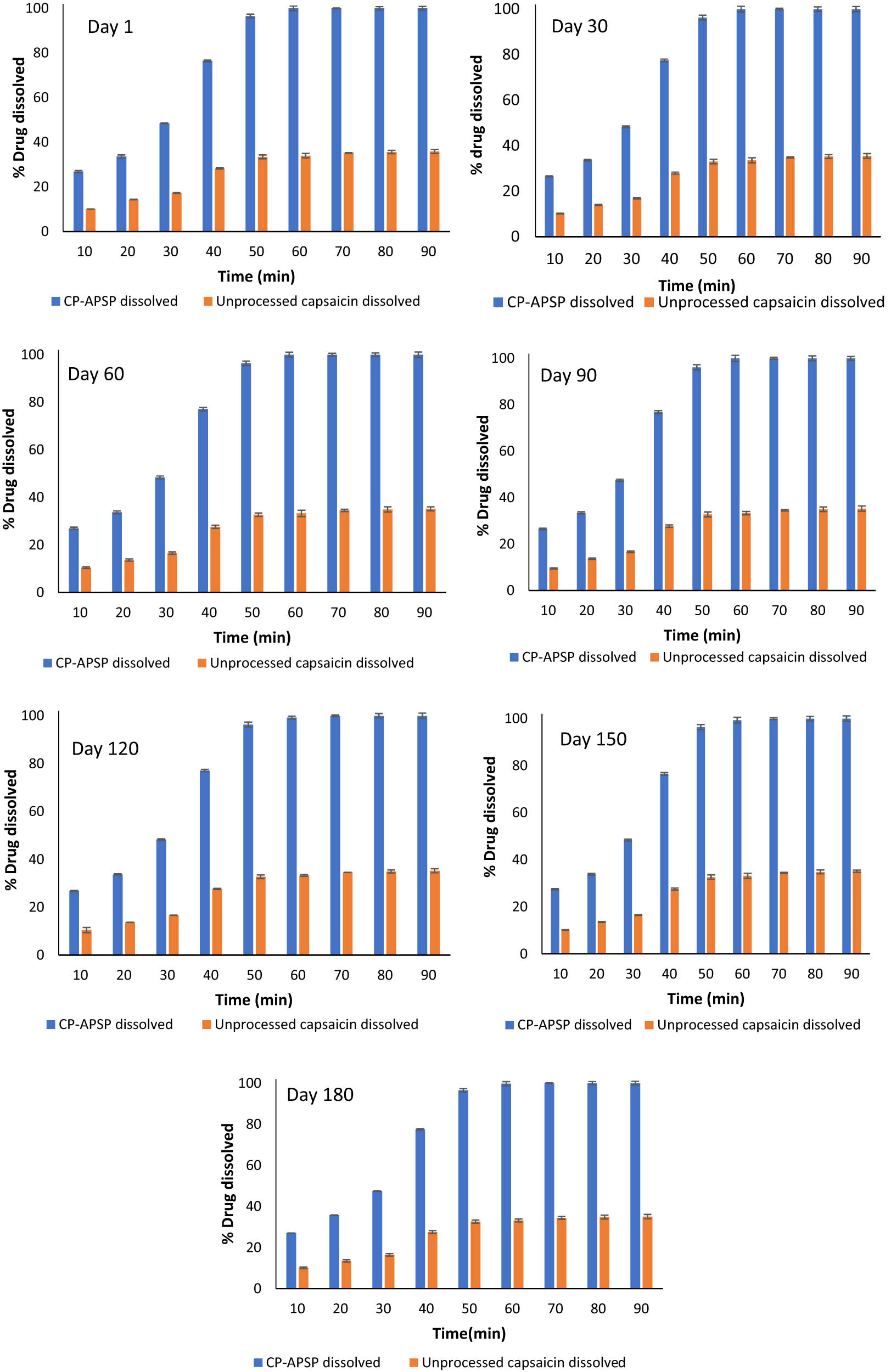

The study also examined the time effect on the dissolution of Capsaicin nanoparticles, stored at 25°C and 6.5 pH for 180 days and monitored periodically (1st, 30th, 60th, 90th, 120th, 150th, and 180th days).

The pH of solutions can fluctuate due to redox reactions, component precipitation, and phase separation, showing instability. The shelf stability study recorded no significant changes in the pH or dissolution profile of samples during storage, as per Figure 8(a)–(g). However, a slightly changed dissolution pattern of the nanoparticles during storage may be due to the changes in particle size when stored at extreme temperatures and pH conditions. The alteration in particle size could be attributed to their merging together [48].

Dissolution pattern of unprocessed capsaicin and CP-APSP at different time intervals (storage pH, 6.5; temperature, 25°C).

The study suggests nanoparticles may be the ideal solution for the bioavailability of drugs with low water solubility. The ideal conditions for storing CP-APSP nanoparticles are between 5 and 30°C (Figure 6) and a 5–7 pH (Figure 7).

3.7 Ex vivo permeation study

Percent nano-drug that permeated through the skin was calculated and noted as 0%, 27.14 ± 0.21%, 28.30 ± 0.20%, 36.20 ± 1.2%, 41.11 ± 1.21%, 50.02 ± 1.31%, 56.06 ± 2.11%, and 70.10 ± 2.14% at time 0, 1st, 2nd, 4th, 6th, 8th, 10th, and 12th h, respectively. The percentage of drugs that permeated, the percentage of drugs that were retained on the skin, and the portion of drugs retained in the skin are listed in Table 6.

Percent of drug permeated, drug retained on the skin, and drug retained in the skin

| Time interval | Drug permeated (%) | Retained in skin (%) | Retained on skin (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 27.14 ± 0.21 | 31.09 ± 2.11 | 18.10 ± 0.21 |

| 2 | 28.30 ± 0.20 | ||

| 4 | 36.20 ± 1.20 | ||

| 6 | 41.11 ± 1.21/. | ||

| 8 | 50.02 ± 1.31 | ||

| 10 | 56.06 ± 2.11 | ||

| 12 | 70.10 ± 2.14 |

Reduced particle sizes of nanoparticles improve capsaicin permeation transversely from the skin and establish a high concentration gradient in the targeted area, which are the factors that collectively provide efficient drug delivery [49]. Therefore, capsaicin will exert maximum pharmacological effects if it is present in a more incredible amount after permeating the skin in a greater quantity [33]. Thus, the nanoform may be the most capable form of capsaicin to enhance its effects at comparatively lower doses and frequencies.

3.8 Anti-inflammatory activity

The study utilized a carrageenan-induced rat paw edema test to assess the efficacy of capsaicin samples in reducing inflammation, as represented in Table 7. After carrageenan caused inflammation, we measured the diameters of the hind paws of rats given different formulations of capsaicin at hourly intervals of 0 and 1–6 h. The inflammation is significantly reduced in groups that received treatment with capsaicin samples; nevertheless, the reduction in edema varies in degree. CP-APSP demonstrated the highest potential for edema inhibition among the groups, particularly at the second and third hours of the test, compared to control and unprocessed capsaicin (Table 7). The cream base components did not influence the inflammatory response in rats, as formulations without capsaicin do not affect inflammation. The CP-APSP cream demonstrated a significant reduction in inflammation at hours 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, surpassing unprocessed capsaicin samples. The study indicates that nanometer-sized particles may significantly enhance capsaicin’s anti-inflammatory properties, likely due to enhanced skin penetration.

Carrageenan induced paw edema (mm3)

| Treatment group | 1st.h | 2nd.h | 3rd.h | 4th.h | 5th.h | 6th.h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.82 ± 0.03 | 1.024 ± 0.02 | 1.24 ± 0.07 | 1.49 ± 0.13 | 1.61 ± 0.14 | 1.72 ± 0.21 |

| Unprocessed capsaicin cream | 0.33 ± 0.04 | 0.43 ± 0.08 | 0.44 ± 0.06 | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 0.44 ± 0.02 | 0.45 ± 0.1 |

| CP-APSP cream | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 0.35 ± 0.09 | 0.33 ± 0.08 | 0.34 ± 0.08 | 0.35 ± 0.08 | 0.34 ± 0.41 |

| Cream base without CP-APSP | 0.80 ± 0.04 | 1.038 ± 0.02 | 1.24 ± 0.09 | 1.50 ± 0.10 | 1.60 ± 0.14 | 1.70 ± 0.10 |

3.9 Analgesic activity

By comparing the analgesic effects of test samples, significant differences are found between the nanoparticles-treated group, the unprocessed capsaicin-treated group, and the untreated control group. Unprocessed capsaicin and CP-APSP cream decrease pain sensations in the rats’ hind paws (Table 8). However, there are clear distinctions between the extent of analgesic effects exhibited by these agents (Table 8). It can be correlated with the previous experiment, in which the in vitro dissolution rates of crude capsaicin and CP-APSP were analyzed to determine their release profiles. It is then discovered that only about 39.923% of the capsaicin in the crude sample is soluble at 24 h, whereas more than 92.432% of the capsaicin in the CP-APSP formulation makes itself soluble during that time. However, the degrees of analgesic effects these drugs demonstrate differ significantly (Table 8). The table (Table 8) presents the analgesic potential of CP-APSP cream and crude capsaicin cream in rats pretreated with different capsaicin formulations. The reaction time latencies of the control, crude capsaicin, CP-APSP, and cream base groups were 8.43 ± 0.1, 13.4 ± 0.9, and 17.2 ± 0.5 s after 1 h, respectively. The same pattern was observed at subsequent time intervals.

Reaction latency time after treatment with different test samples

| Sample administered | Reaction time after treatment with different test samples (s) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 h | 1 h | 2 h | 3 h | 4 h | 5 h | |

| Control | 9.04 ± 0.20 | 8.43 ± 0.1 | 7.56 ± 0.1 | 8.1 ± 0.2 | 7.6 ± 0.23 | 7.5 ± 0.80 |

| Unprocessed capsaicin cream | 13.10 ± 0.6 | 13.3 ± 0.9 | 12.1 ± 0.8 | 11.6 ± 0.9 | 10.69 ± 0.9 | 10.73 ± 0.9 |

| CP-APSP cream | 18.65 ± 0.8 | 17.2 ± 0.5 | 16.3 ± 0.9 | 15.3 ± 0.2 | 14.93 ± 0.8 | 13.41 ± 0.7 |

| Cream base without capsaicin | 8.52 ± 0.30 | 8.58 ± 0.2 | 8.10 ± 0.2 | 7.90 ± 0.3 | 7.5 ± 0.91 | 7.60 ± 0.7 |

Table 8 reveals that surprisingly, crude capsaicin cream has a minimal latency duration, even less than that of the control group at the “zero” time interval. This change may be due to the effects of capsaicin. According to research, exposure to topical capsaicin may elicit hypersensitivity to heat, itchy sensations, and pain from heat and cold immediately after application [50]. It can also cause burning, followed by desensitization [51]. This increased sensitivity to heat might have been the reason for the reduced latency time in the group administered crude capsaicin. Analyzing the results makes it evident that the given treatment duration is not enough for crude capsaicin to penetrate deeply in an adequate amount to prevent the rats from sensing the heat. Therefore, compared to the control group, the rats become more sensitive to the stimuli due to the limited amount of capsaicin reaching at time zero [50]. The amount penetrated is too small to have any analgesic effect. At the specified intervals, the differences between the control and crude capsaicin groups ceased to be statistically significant. Depending on its dose, application time, and skin penetration, capsaicin extends analgesia by lowering the sensitivity of skin sensory nerves, according to the findings of other researchers. Skin penetration by the nanoform is best due to reduced particle sizes; therefore, its analgesic action is also prominent.

3.10 Antimicrobial activities

The antibacterial and antifungal activities of capsaicin NPs were assessed in order to identify possible uses of the produced NPs as antimicrobial agents for pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and cosmetic products.

3.10.1 Antibacterial activity

The antimicrobial activity of unprocessed capsaicin is summarized in Table 9.

Antibacterial activity of unprocessed capsaicin

| Gram +ve bacteria | Zone of inhibition (mm) | Ciprofloxacin | Gram −ve bacteria | Zone of inhibition (mm) | Ciprofloxacin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. Aureus | 13.0 ± 0.1 | 23.0 ± 0.03 | E. coli | 10.60 ± 0.10 | 27.01 ± 1.0 |

| S. pneumoniae | 8.9 ± 1.20 | 18.5 ± 0.80 | K. pneumonia | 12.0 ± 1.9 | 22.20 ± 1.0 |

| S. pyogenes | 10.8 ± 1.5 | 21.8 ± 0.20 | Enterobacter aerogenes | 10.6 ± 0.2 | 24.6 ± 1.03 |

| S. Epidermidis | 7.60 ± 0.4 | 21.8 ± 1.2 | H. influenza | 10.0 ± 0.19 | 21.8 ± 1.67 |

| Vancomycin sensitive Enterococci | 7.5 ± 0.13 | 18.4 ± 0.02 | P. Aeruginosa | 7.02 ± 0.56 | 24.2 ± 2.01 |

| S. viridians | 8.1 ± 0.20 | 17.8 ± 0.80 | P. mirabilis | 6.60 ± 0.70 | 19.30 ± 0.2 |

3.10.1.1 Zone of inhibition of unprocessed capsaicin and CP-APSP

Table 9 reveals that unprocessed capsaicin has the highest inhibition zone against S. aureus at 13.0 ± 0.10 mm, while the lower zone against S. epidermidis at 07.6 ± 0.4 mm and the lowest zone (07.5 ± 0.130 mm) against Vancomycin-sensitive Enterococcus. Unprocessed capsaicin showed the highest zone of inhibition against K. pneumonia, measuring 12 ± 01.90 mm, while it had a tiny area of inhibition against P. mirabilis.

Table 10 reveals that CP-APSP has better antibacterial effects exhibiting larger zones of inhibition against S. aureus and S. viridans compared to unprocessed capsaicin. The study also shows that CP-APSP showed a 13.8 ± 1.2 mm zone of inhibition against E. coli, compared to the 10.6 ± 0.1 mm of unprocessed capsaicin against this pathogen, and a 14.11 ± 0.2 mm zone of inhibition against K. pneumonia compared to the 12 ± 1.9 mm of unprocessed capsaicin (Tables 9 and 10). CP-APSP showed a zone of inhibition against P. aeruginosa at 9.20 ± 01.30 mm (higher than unprocessed capsaicin’s 7.02 ± 0.56 mm zone of inhibition) and an 8.20 ± 0.38 mm zone of inhibition against P. mirabilis. It is the most minor activity against any tested bacteria in this experiment; however, its zone of inhibition still is greater than the 6.6 ± 0.7 mm zone of inhibition recorded when P. mirabilis was tested with unprocessed capsaicin. Against every tested pathogen, the diameter of the zone of inhibition of CP-APSP is greater than that achieved when the same pathogens were tested with unprocessed capsaicin (Tables 9 and 10).

Antibacterial activity of capsaicin nanoparticles mg·mL−1

| Gram +ve bacteria | Zone of inhibition (mm) | Ciprofloxacin | Gram −ve bacteria | Zone of inhibition (mm) | Ciprofloxacin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. Aureus | 14.5 ± 1.20 | 23.0 ± 0.03 | E. coli | 13.8 ± 1.2 | 27.01 ± 1.0 |

| S. pneumoniae | 12.01 ± 0.2 | 18.5 ± 0.80 | K. pneumonia | 14.11 ± 0.2 | 22.20 ± 1.0 |

| S. pyogenes | 13.9 ± 1.30 | 21.8 ± 0.20 | Enterobacter aerogenes | 11.30 ± 1.20 | 24.6 ± 1.03 |

| S. Epidermidis | 11.40 ± 1.6 | 21.8 ± 1.2 | H. influenza | 11.30 ± 1.10 | 21.8 ± 1.67 |

| Vancomycin sensitive Enterococci | 10.21 ± 1.2 | 18.4 ± 0.02 | P. Aeruginosa | 9.20 ± 1.3 | 24.2 ± 2.01 |

| S. viridians | 11.13 ± 0.3 | 17.8 ± 0.80 | P. mirabilis | 8.20 ± 0.38 | 19.30 ± 0.2 |

3.10.1.2 MIC and MBC values of unprocessed capsaicin and CP-APSP

Tables 11–14 show the MICs and MBCs of unprocessed capsaicin and CP-APSP, which are higher for Gram-negative pathogens. Unprocessed capsaicin’s MIC values ranged from 10.32 ± 1.40 (S. pyogenes) to 18.12 ± 0.4 mg·mL−1 (P. aeruginosa). It recorded the highest MBC value against P. aeruginosa (26.4 ± 1.60 mg·mL−1) and the lowest MBC against E. coli (20.9 ± 1.20 mg·mL−1).

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of unprocessed capsaicin mg·mL−1

| Gram +ve bacteria | MIC (mg·mL−1) | Ciprofloxacin | Gram −ve bacteria | MIC (mg·mL−1) | Ciprofloxacin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. Aureus | 10.62 ± 0.04 | 1.24 ± 0.40 | E. coli | 15.50 ± 1.82 | 0.600 ± 0.11 |

| S. pneumoniae | 12.2 ± 1.30 | 2.0 ± 0.03 | K. pneumonia | 12.88 ± 1.50 | 0.85 ± 0.09 |

| S. pyogenes | 10.32 ± 1.4 | 0.39 ± 0.98 | Enterobacter aerogenes | 12.43 ± 0.92 | 1.50 ± 0.89 |

| S. Epidermidis | 11.10 ± 2.6 | 0.41 ± 0.07 | H. influenza | 12.80 ± 1.73 | 1.0 ± 0.26 |

| Vancomycin sensitive Enterococci | 11.8 ± 3.9 | 0.97 ± 0.91 | P. Aeruginosa | 18.12 ± 0.4 | 1.08 ± 0.20 |

| S. viridians | 11.6 ± 2.04 | 1.48 ± 1.04 | P. mirabilis | 17.09 ± 1.07 | 0.60 ± 0.98 |

Minimum bactericidal concentration of unprocessed capsaicin mg·mL−1

| Gram +ve bacteria | MBC (mg·mL−1) | Ciprofloxacin | Gram −ve bacteria | MBC (mg·mL−1) | Ciprofloxacin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. Aureus | 18.6 ± 2.3 | 1.24 ± 0.40 | E. coli | 20.90 ± 1.2 | 0.600 ± 0.11 |

| S. pneumoniae | 19.4 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 0.03 | K. pneumonia | 21.08 ± 0.42 | 0.85 ± 0.09 |

| S. pyogenes | 18.9 ± 1.2 | 0.39 ± 0.98 | Enterobacter aerogenes | 21.0 ± 1.73 | 1.50 ± 0.89 |

| S. Epidermidis | 20.1 ± 1.9 | 0.41 ± 0.07 | H. influenza | 21.1 ± 2.1 | 1.0 ± 0.26 |

| Vancomycin sensitive Enterococci | 19.9 ± 2.7 | 0.97 ± 0.91 | P. Aeruginosa | 26.4 ± 1.6 | 0.81 ± 0.020 |

| S. viridians | 20.8 ± 3.5 | 1.48 ± 1.04 | P. mirabilis | 25.1 ± 0.4 | 0.69 ± 0.98 |

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Capsaicin nanoparticles mg·mL−1

| Gram +ve bacteria | MIC (mg·mL−1) | Ciprofloxacin | Gram −ve bacteria | MIC (mg·mL−1) | Ciprofloxacin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. Aureus | 8.65 ± 1.3 | 1.24 ± 0.40 | E. coli | 9.22 ± 1.2 | 0.600 ± 0.11 |

| S. pneumoniae | 10.1 ± 1.5 | 2.0 ± 0.03 | K. pneumonia | 11.70 ± 1.9 | 0.85 ± 0.09 |

| S. pyogenes | 8.91 ± 0.8 | 0.39 ± 0.98 | Enterobacter aerogenes | 10.71 ± 1.83 | 1.50 ± 0.89 |

| S. Epidermidis | 08.2 ± 1.7 | 0.41 ± 0.07 | H. influenza | 10.20 ± 1.73 | 1.0 ± 0.26 |

| Vancomycin sensitive Enterococci | 10.4 ± 1.9 | 0.97 ± 0.91 | P. Aeruginosa | 14.82 ± 1.43 | 1.08 ± 0.20 |

| S. viridians | 9.50 ± 1.3 | 1.48 ± 1.04 | P. mirabilis | 14.8 ± 1.70 | 0.60 ± 0.98 |

Minimum Bactericidal Concentration of capsaicin nanoparticles mg·mL−1

| Gram +ve bacteria | MBC (mg·mL−1) | Ciprofloxacin | Gram −ve bacteria | MBC (mg·mL−1) | Ciprofloxacin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. Aureus | 14.5 ± 2.3 | 1.24 ± 0.40 | E. coli | 15.3 ± 1.9 | 0.600 ± 0.11 |

| S. pneumoniae | 16.8 ± 2.7 | 2.0 ± 0.03 | K. pneumonia | 16.1 ± 0.30 | 0.85 ± 0.09 |

| S. pyogenes | 15.7 ± 1.8 | 0.39 ± 0.98 | Enterobacter aerogenes | 18.10 ± 1.3 | 1.50 ± 0.89 |

| S. Epidermidis | 17.6 ± 1.9 | 0.41 ± 0.07 | H. influenza | 17.13 ± 1.7 | 1.0 ± 0.26 |

| Vancomycin sensitive Enterococci | 17.7 ± 1.8 | 0.97 ± 0.91 | P. Aeruginosa | 23.5 ± 1.4 | 0.81 ± 0.020 |

| S. viridians | 18.1 ± 1.4 | 1.48 ± 1.04 | P. mirabilis | 21.9 ± 3.5 | 0.69 ± 0.98 |

CP-APSP recorded 8.65 ± 1.3 and 10.1 ± 1.5 mg·mL−1 MICs against S. aureus and S. pneumoniae, respectively (Tables 13 and 14) and MBC values of 14.5 ± 2.3 and 16.8 ± 2.7 mg·mL−1 against these microorganisms. For S. Epidermidis, CP-APSP recorded MIC at 8.20 ± 1.7 and MBC at 17.6 ± 1.9 mg·mL−1. Its MIC was noted for Vancomycin-sensitive Enterococcus at 10.4 ± 1.90 and MBC at 17.7 ± 1.8 mg·mL−1. The MIC and MBC values for S. viridans are 9.5 ± 1.3 and 18.1 ± 1.4 mg·mL−1, respectively. In the case of Gram-negative pathogens, the MIC and MBC values are higher compared to the values recorded for Gram-positive pathogens.

Studies show that capsaicin also possesses the property of modifying bacterial resistance by inhibiting the system of efflux pumps in bacteria [52]. Due to its antimicrobial properties, it may be used in complementary therapies or can substitute antibiotic compounds in our strategy to control bacterial infections [53]. Therefore, it is paramount to evaluate the antimicrobial effects of CP-APSP and their comparison with those of unprocessed capsaicin. The performance of CP-APSP proved far superior against all bacteria compared to unprocessed capsaicin (Tables 9–14). Tables 9–14 confirm the enhanced activity of CP-APSP against all tested bacteria, revealing different levels of antimicrobial capacity and efficiency in each sample against different pathogens. The most resistant pathogens are P. mirabilis and Vancomycin-sensitive Enterococcus, whereas S. aureus and S. pyogenes are the most sensitive pathogens among all the bacteria. Results also indicate that gram-positive bacteria are more sensitive to CP-APSP than gram-negative bacteria. P. mirabilis showed a minor zone of inhibition (6.9 ± 0.7 mm) when treated with unprocessed capsaicin, as per the zones of inhibition diameters in Table 9. Researchers have already revealed this information regarding P. mirabilis [54]. Table 13 shows that CP-APSP has varying effects on Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, with MIC values ranging from 8.20 ± 1.7 to 14.82 ± 1.43 mg·mL−1 and being most effective against S. epidermidis.

The antibacterial effects of unprocessed capsaicin and CP-APSP are also compared to the antibiotic ciprofloxacin (Tables 9–14). According to the data, CP-APSP exhibited significantly higher zones of inhibition than unprocessed capsaicin and had the highest inhibition zones against all microorganisms after ciprofloxacin. CP-APSP outperformed unprocessed capsaicin by a wide margin. The cultures that were inoculated with CP-APSP (Table 10) demonstrated higher zones of inhibition in comparison with the unprocessed capsaicin and proved the effectiveness of the nano-drug as a far better antibacterial compound, as noted in other studies [54].

3.10.2 Antifungal activities

3.10.2.1 Zones of inhibition demonstrated by unprocessed capsaicin and CP-APSP

Table 15 displays the zones of inhibition for unprocessed capsaicin against selected fungi. T. rubrum and Penicillium digitatum showed the highest inhibition zones (8.12 ± 1.6 mm) and 1.9 ± 0.10 mm, respectively. Similarly, C. albicans had the highest zone (8.97 ± 1.95 mm), and C. tropicalis had the lowest (4.6 ± 0.1 mm). When compared to unprocessed capsaicin, experiments demonstrate noticeably enhanced antifungal effects of CP-APSP, as evidenced by the greater diameters of the zones of inhibition (Tables 15 and 16).

Antifungal activity of unprocessed capsaicin

| Molds | Zone of inhibition | Amphotericin B | Yeasts | Zone of inhibition | Amphotericin B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. niger | 8.0 ± 0.30 | 10.0 ± 0.07 | C. albicans | 8.97 ± 1.950 | 25.0 ± 1.79 |

| Penicillium digitatum | 1.9 ± 0.10 | 11.0 ± 0.10 | C. neoformans | 8.00 ± 0.10 | 13.0 ± 0.93 |

| F. oxysporum | 7.03 ± 0.2 | 18.0 ± 1.01 | C. lusitaniae | 5.46 ± 0.5 | 22.0 ± 1.05 |

| T. rubrum | 8.12 ± 1.6 | 32 ± 01.87 | C. tropicalis | 4.60 ± 0.100 | 23.0 ± 1.21 |

| A. fumigates | 7.80 ± 0.4 | 31.10 ± 0.01 | C. parapsilosis | 6.80 ± 1.78 | 23.0 ± 0.33 |

| T. mentagrophytes | 8.1 ± 1.2 | 28 ± 3.20 | C. krusei | 6.84 ± 1.4 | 20.3 ± 2.4 |

Antifungal activity of capsaicin nanoparticles

| Molds | Zone of inhibition (mm) | Amphotericin B | Yeasts | Zone of inhibition (mm) | Amphotericin B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. niger | 9.87 ± 0.2 | 10.0 ± 0.07 | C. albicans | 10.6 ± 1.83 | 25.0 ± 1.79 |

| Penicillium digitatum | 2.10 ± 0.3 | 11.0 ± 0.1 | C. neoformans | 9.1 ± 0.02 | 13.0 ± 0.93 |

| F. oxysporum | 8.61 ± 0.1 | 18.0 ± 1.01 | C. lusitaniae | 6.35 ± 1.3 | 22.0 ± 1.05 |

| T. rubrum | 9.2 ± 0.43 | 32 ± 01.87 | C. tropicalis | 05.0 ± 0.7 | 23.0 ± 1.21 |

| A. fumigates | 9.64 ± 1.8 | 31.10 ± 0.01 | C. parapsilosis | 7.28 ± 0.9 | 23.0 ± 0.33 |

| T. mentagrophytes | 09.0 ± 0.8 | 28 ± 3.20 | C. krusei | 7.37 ± 2.0 | 24 ± 2.40 |

3.10.2.2 MIC and MFC values of unprocessed capsaicin and CP-APSP

Tables 17 and 18 display unprocessed capsaicin’s MIC and MFC values against selected fungi. The highest MIC is recorded against C. parapsilosis (358.200 ± 03.160 mg·mL−1). The MFC values of CP-APSP range from 498.30 ± 3.80 mg·mL−1 (T. mentagrophytes) to 594.7 ± 5.10 mg·mL−1 (A. niger).

Minimum Inhibitory concentration of unprocessed capsaicin mg·mL−1

| Mold | MIC (mg·mL−1) | Amphotericin B | Yeast | MIC (mg·mL−1) | Amphotericin B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. niger | 418 | 27 | C. albicans | 305.33 ± 2.11 | 10 |

| Penicillium digitatum | 300 | 100 | C. neoformans | 351.6 ± 4.3 | 12.7 ± 0.05 |

| F. oxysporum | 306.2 ± 2.4 | 12.52 ± 0.34 | C. lusitaniae | 378.2 ± 4.12 | 08 ± 0.92 |

| T. rubrum | 275.4 ± 3.2 | 5 | C. tropicalis | 276.2 ± 3.4 | 7 ± 0.98 |

| A. fumigates | 282.1 ± 2.3 | 2.40 ± 1.07 | C. parapsilosis | 358.2 ± 3.16 | 15.0 ± 0.04 |

| T. mentagrophytes | 354.4 ± 3.2 | 0.350 ± 0.21 | C. krusei | 341.3 ± 160 | 16 ± 0.22 |

Minimum Fungicidal Concentration of unprocessed capsaicin mg·mL−1

| Molds | MFC (mg·mL−1) | Amphotericin B | Yeasts | MFC (mg·mL−1) | Amphotericin B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. niger | 594.7 ± 5.1 | 25 | C. albicans | 525.47 ± 4.3 | 30 |

| Penicillium digitatum | 508.5 ± 4.30 | 100 | C. neoformans | 513.4 ± 3.2 | 50 ± 2.88 |

| F. oxysporum | 531 | 25.0 ± 0.92 | C. lusitaniae | 521.3 ± 4.13 | 14.5 ± 0.18 |

| T. rubrum | 521.9 ± 2.1 | 11 | C. tropicalis | 528.4 ± 2.3 | 28 ± 1.01 |

| A. fumigates | 517 | 2.40 ± 1.07 | C. parapsilosis | 534.3 ± 4.1 | 16 ± 0.98 |

| T. mentagrophytes | 498.3 ± 3.8 | 0.650 ± 0.81 | C. krusei | 523.4 ± 3.9 | 16.0 ± 0.09 |

Our findings showed lower MIC and MFC values when CP-APSP was applied to the tested fungi compared to unprocessed capsaicin. CP-APSP has recorded different MIC and MFC values against different fungi. The most sensitive fungus to CP-APSP is C. albicans, and the most resistant fungus is A. niger (MICs 223.24 ± 1.4 and 321 mg·mL−1, respectively, (Table 19).

Tables 17–20 show the MIC and MFC results of the unprocessed nanocapsaicin samples. As per the tables, the MIC values for unprocessed capsaicin samples range from 275.4 ± 5.2 to 418 mg·mL−1, and the MFC values range from 498.3 ± 5.8 to 594.7 ± 5.1 mg·mL−1. In the case of CP-APSP, MIC values range between 223.24 ± 5.43 and 321 mg·mL−1, and the MFC values range between 393 ± 2.7 and 487 ± 0.24 mg·mL−1. Unprocessed capsaicin recorded the lowest MFC value against T. mentagrophytes and the highest MFC against A. niger. The lowest MFC value is recorded against C. albicans, while the highest MFC value is against A. niger by CP-APSP. When tested with CP-APSP, A. niger and C. parapsilosis required respective MFC values of 487 ± 0.24 mg·mL−1 (highest) and 472 ± 4.11 mg·mL−1 (second highest). In general, CP-APSP shows better antimicrobial activities than those of unprocessed capsaicin.

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of capsaicin nanoparticles mg·mL−1

| Molds | MIC (mg·mL−1) | Amphotericin B | Yeasts | MIC (mg·mL−1) | Amphotericin B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. niger | 321 | 25 | C. albicans | 223.24 ± 1.4 | 10 |

| Penicillium digitatum | 260 | 100 | C. neoformans | 291.7 ± 2.15 | 12.7 ± 0.05 |

| F. oxysporum | 246.3 ± 2.1 | 25.0 ± 0.92 | C. lusitaniae | 301.9 ± 1.86 | 08 ± 0.9 |

| T. rubrum | 231.8 ± 3.0 | 11 | C. tropicalis | 264.2 ± 2.70 | 7.0 ± 0.98 |

| A. fumigates | 238.4 ± 0.8 | 2.40 ± 1.07 | C. parapsilosis | 292.4 ± 2.15 | 15.0 ± 0.04 |

| T. mentagrophytes | 268.6 ± 3.4 | 0.650 ± 0.81 | C. krusei | 278.6 ± 2.70 | 16 ± 0.22 |

Minimum fungicidal concentration of Capsaicin nanoparticles mg·mL−1

| Molds | MFC (mg·mL−1) | Amphotericin B | Yeasts | MFC (mg·mL−1) | Amphotericin B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. niger | 487 ± 0.24 | 25 | C. albicans | 393.0 ± 2.7 | 30 |

| Penicillium digitatum | 400 ± 0.12 | 100 | C. neoformans | 417 ± 3.18 | 50 ± 2.88 |

| F. oxysporum | 416 ± 0.41 | 25.0 ± 0.92 | C. lusitaniae | 413.0 ± 1.3 | 14.5 ± 0.18 |

| T. rubrum | 406 ± 0.90 | 11 | C. tropicalis | 405.0 ± 0.9 | 28 ± 1.01 |

| A. fumigates | 400 ± 0.86 | 2.40 ± 1.07 | C. parapsilosis | 472 ± 4.11 | 16 ± 0.98 |

| T. mentagrophytes | 411 ± 0.73 | 0.650 ± 0.81 | C. krusei | 458 ± 1.28 | 16.0 ± 0.09 |

CP-APSP exhibited higher antibacterial activity than unprocessed capsaicin in every way, with larger zones of inhibition and lower MIC and MFC values. Converting capsaicin to nanometer size enhances its antimicrobial potential, allowing for lower drug concentrations and better outcomes, with MIC values declining by up to 50% in some cases.

Currently, used drugs possess various toxic effects, so there is an exhaustive research program all over the globe to find novel natural antimicrobial drugs [55]. Therefore, the encouraging findings from these experiments are significant and can enable us to formulate these desperately needed drugs.

Nanoparticles have increased penetration due to tiny diameters, and when used as adjuncts, they may also produce significantly better results by enhancing the activities of other antimicrobials. The increased area of the surface-to-volume ratio of nanoparticles also contributes to their enhanced antimicrobial effects. When the particle size (nanoparticles) gets smaller, the antimicrobial effectiveness is increased [56]. Small-sized particles with a larger surface-to-volume ratio can make available more proficient ways for antibacterial actions [56,57]. In addition, the particles’ morphology also affects their activity. Because nanoparticles have delicate surfaces and nanometer sizes, they may use all their surfaces in any direction to enter the bacterial cell membrane.

As particle sizes decrease, they can better permeate the microbial cell membrane via smaller holes, resulting in their presence in higher concentrations. The infiltration of additional capsaicin in nanoparticles into microbial cells increased antibacterial activity and disrupted the bacterial cell membrane. It can also stop those bacterial strains from growing, which, if left unchecked, may result in antibiotic resistance and failure of therapy. Their nanoform is discovered to be more efficient against the tested bacteria than their unprocessed counterparts; hence, the synergistic usage of naturally occurring compounds synthesized in the nanoparticle range in conjunction with antibiotics may provide positive outcomes.

4 Safety of nanoparticles and future work

The field of nanotechnology has grown over the last two decades and made the transition from benchtop to applied technologies. Nanoparticles have also been involved in therapeutic and diagnostic purposes. During the past two decades, a growing number of nanomedicines have received regulatory approval, and many more show promise for future clinical translation. In this context, it is important to evaluate the safety of nanoparticles in order to achieve biocompatibility and desired activity. Indeed, several nanotherapeutics that are currently approved, such as Doxil and Abraxane, exhibit fewer side effects than their small molecule counterparts, while other nanoparticles (e.g., metallic and carbon-based particles) tend to display toxicity. Nevertheless, the hazardous nature of certain nanomedicines could also be exploited for the ablation of diseased tissue, if selective targeting can be achieved [58]. However, it is unwarranted to make generalized statements regarding the safety of nanoparticles, since the field of nanomedicine comprises a multitude of different manufactured nanoparticles made from various materials.

Like any drug or chemical, the toxicity of NPs depends on their exposure [59]. Exposure to NPs may occur through ingestion, injection, inhalation, and skin contact. The organ-specific toxicity following exposure to NPs depends on the route of administration and their systemic distribution. Some exposures are unintentional, such as in pulmonary inhalation of NPs in the environment or manufacturing places which may result in inflammatory reactions and necrosis of lung tissues. Other exposures are intentional, such as drug administration via different routes.

Once they reach the blood circulation, NPs can be distributed and can accumulate in different organs such as the liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys. Some studies also suggest that NPs may also accumulate in the brain if they are small enough (<10 nm). Accumulation of NPs in specific organs depends on their leaky blood vessels and the physical and chemical properties of NPs. Distribution of NPs depends on their surface area to size ratio, which also mediates their propensity to accumulate in different tissues and organs.

NPs, accumulated in different organs, interact with cellular macromolecules and may cause oxidative stress, DNA damage, modification of protein structures, and disruption of membrane integrity. Metal-containing or metal oxide NPs have also been shown to cause inflammation and inhibit the effects of antioxidants, which may result in cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Titanium dioxide NPs have activated inflammatory signaling pathways and to increase the release of inflammatory cytokines from macrophages after their accumulation in macrophage-rich organs, such as the liver and spleen [60,61].

Efforts have identified several approaches to minimize and prevent nanoparticle toxicity to promote safer nanotechnology [62]. One approach being used in the design of safer NPs can be their preparation using ingredients that have been generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by the FDA. Studies have also shown that many toxic effects of NPs are associated with solid or metal-containing NPs. Thus, efforts are being made to limit their use.

Complete toxicological profiling of NPs and the development of structure–activity relationships will help identify the key physical or chemical properties of NPs that cause their toxicity and help design safer strategies to minimize NP toxicity by optimizing their physicochemical properties while maximizing their biological efficacies. Current data on the toxicity of NPs in mammalian cells and tissues suggest that studies are needed to focus on gaining additional insights underlying their toxicity, as well as developing strategies to minimize and prevent the toxicity of NPs. Such strategies need to take into consideration both acute and also chronic exposures to NPs. Whether or not NPs are persistent or degradable, it is crucial to emphasize that the pharmacokinetic properties of NPs such as their distribution and elimination should be taken into account

Future work should also focus on the fate of NPs in biological systems and how organisms react to the long-term exposure of NPs.

5 Conclusions

The APSP/EPN techniques stand out for their ease of execution, low cost, reproducibility, minimal raw material consumption, and biocompatibility, making them excellent choices for industrial production. The strategy is successful, and the efficacy of CP-APSP is many-fold enhanced. Converting capsaicin into nanoform produces more significant effects. The findings lend credence to the notion that nanoparticle-based drugs may be more effective in treating various medical conditions. According to the findings, the CP-APSP cream formulation may be recommended for topical application as a superior analgesic and anti-inflammatory compound. Capsaicin with a nanoscale size has better antibacterial activity and can also be utilized to prevent food-borne pathogenic microbes naturally. The findings here support the prophylactic and curative uses of CP-APSP for various ailments and can be utilized across various biomedical studies and applications.

Acknowledgment

The authors extend their appreciation to the researchers supporting Project number (RSP2024R110) at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for financial support.

-

Funding information: Researchers supporting Project number (RSP2024R110) King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contributions: Mujahid Sher: conceptualization, methodology, performed experiments and writing – original draft; Ishtiaq Hussain and Farhat Ali Khan: conceptualization, methodology, writing – review and editing and visualization; Wiaam Mujahid Sher, Muhammad Saqib Khalil, and Muhammad Sulaiman: methodology, writing, editing, checking for grammar, typing, and statistical analysis, Riaz Ullah and Essam A. Ali; editing, resources, and investigation; Muhammad Zahoor and Sumaira Naz: conceptualization, funding acquisition, and writing – review and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Al-Samydai A, Aburjai T, Alshaer W, Azzam H, Al-Mamoori F. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of capsaicin from Capsicum annum grown in Jordan. Int J Res Pharm Sci. 2019;10(4):3768–74. 10.26452/ijrps.v10i4.1767.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Bustos D, Galarza C, Ordoñez W, Brauchi S, Benso B. Cost-effective pipeline for a rational design and selection of capsaicin analogues targeting TRPV1 channels. ACS Omega. 2023;8(13):11736–49. 10.1021/acsomega.2c05672.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Lim SG, Seo SE, Jo S, Kim KH, Kim L, Kwon OS. Highly efficient real-time TRPV1 screening methodology for effective drug candidates. ACS Omega. 2022;7(41):36441–7. 10.1021/acsomega.2c04202.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Raeissadat SA, Rayegani SM, Sadeghi F, Rahimi-Dehgolan S. Comparison of ozone and lidocaine injection efficacy vs dry needling in myofascial pain syndrome patients. J Pain Res. 2018;11:1273–9. 10.2147/JPR.S164629.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Alnusaire TS, Sabouni IL, Khojah H, Qasim S, Al-Sanea MM, Siddique S, et al. Integrating chemical profiling, in vivo study, and network pharmacology to explore the anti-inflammatory effect of pterocarpus dalbergioides fruits and its correlation with the major phytoconstituents. ACS Omega. 2023;8(36):32544–54. 10.1021/acsomega.3c02940.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Wang Y, Cui L, Xu H, Liu S, Zhu F, Yan F, et al. TRPV1 agonism inhibits endothelial cell inflammation via activation of eNOS/NO pathway. Atherosclerosis. 2017;260:13–9. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.03.016.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Batiha GE, Alqahtani A, Ojo OA, Shaheen HM, Wasef L, Elzeiny M, et al. Biological properties, bioactive constituents, and pharmacokinetics of some Capsicum spp. and capsaicinoids. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(15):5179. 10.3390/ijms21155179.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Mankowski C, Poole CD, Ernault E, Thomas R, Berni E, Currie CJ, et al. Effectiveness of the capsaicin 8% patch in the management of peripheral neuropathic pain in European clinical practice: the ASCEND study. BMC Neurol. 2017;17(1):1–11. 10.1186/s12883-017-0836.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Brown S, Simpson DM, Moyle G, Brew BJ, Schifitto G, Larbalestier N, et al. NGX-4010, a capsaicin 8% patch, for the treatment of painful HIV-associated distal sensory polyneuropathy: integrated analysis of two phase III, randomized, controlled trials. AIDS Res Ther. 2013;10:1–2. 10.1186/1742-6405-10-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Kargbo RB. The Synergistic Effects of 5-HT2A and TRP Agonism/Antagonism in Reducing Inflammation for Enhanced Mental and Physical Health. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2023;14(8):1038–40. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.3c00276.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Filipczak-Bryniarska I, Krzyzewski RM, Kucharz J, Michalowska-Kaczmarczyk A, Kleja J, Woron J, et al. High-dose 8% capsaicin patch in treatment of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: single-center experience. Med Oncol. 2017;34:1–5. 10.1007/s12032-017-1015-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Orlo E, Russo C, Nugnes R, Lavorgna M, Isidori M. Natural methoxyphenol compounds: Antimicrobial activity against foodborne pathogens and food spoilage bacteria, and role in antioxidant processes. Foods. 2021;10(8):1807. 10.3390/foods10081807.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Rezazadeh A, Hamishehkar H, Ehsani A, Ghasempour Z, Moghaddas Kia E. Applications of capsaicin in food industry: Functionality, utilization and stabilization. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2023;63(19):4009–25. 10.1080/10408398.2021.1997904.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Wang F, Huang X, Chen Y, Zhang D, Chen D, Chen L, et al. Study on the effect of capsaicin on the intestinal flora through high-throughput sequencing. ACS Omega. 2020;5(2):1246–53. 10.1021/acsomega.9b03798.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Qais FA, Ahmad I, Altaf M, Alotaibi SH. Biofabrication of gold nanoparticles using Capsicum annuum extract and its antiquorum sensing and antibiofilm activity against bacterial pathogens. ACS Omega. 2021;6(25):16670–82. 10.1021/acsomega.1c02297.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Mahmood S, Mei TS, Yee WX, Hilles AR, Alelwani W, Bannunah AM. Synthesis of capsaicin loaded silver nanoparticles using green approach and its anti-bacterial activity against human pathogens. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2021;17(8):1612–26. 10.1166/jbn.2021.3122.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Hall OM, Broussard A, Range T, Carroll Turpin MA, Ellis S, Lim VM, et al. Novel agents in neuropathic pain, the role of capsaicin: Pharmacology, efficacy, side effects, different preparations. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2020 Sep;24:1–2.10.1007/s11916-020-00886-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Bonezzi C, Cos-tantini A, Cruccu G, Fornasari DM, Guardamagna V, Palmieri V, et al. Capsaicin 8% dermal patch in clinical practice: An expert opinion. Expert Opin Pharm. 2020;21(11):1377–87.10.1080/14656566.2020.1759550Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Javid H, Ahmadi S, Mohamadian E. Therapeutic applications of apigenin and its derivatives: micro and nano aspects. Micro Nano Bio Asp. 2023;2(1):30–8. 10.22034/mnba.2023.388488.1025.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Maghsoudloo M, Bagheri Shahzadeh Aliakbari R. Lutein with various therapeutic activities based on micro and nanoformulations: A systematic mini-review. Micro Nano Bio Asp. 2023;2(4):1–7. 10.22034/mnba.2023.409671.1041.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Francis SP, Rene Christena L, Francis MP, Abdul MH. Nanotechnology: A potential approach for nutraceuticals. Curr Nutr Food Sci. 2023;19:673–81. 10.2174/1573401319666221024162943.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Li X, Gu L, Xu Y, Wang Y. Preparation of fenofibrate nanosuspension and study of its pharmacokinetic behavior in rats. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2009;35:827–33. 10.1080/03639040802623941.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Sahibzada MU, Sadiq A, Zahoor M, Naz S, Shahid M, Qureshi NA. Enhancement of bioavailability and hepatoprotection by silibinin through conversion to nanoparticles prepared by liquid antisolvent method. Arab J Chem. 2020;13:3682–9. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2020.01.002.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Sahibzada MU, Zahoor M, Sadiq A, ur Rehman F, Al-Mohaimeed AM, Shahid M, et al. Bioavailability and hepatoprotection enhancement of berberine and its nanoparticles prepared by liquid antisolvent method. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021;28:327–32. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.10.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Rahman F, Sarma J, Mohan P, Barua CC, Nath R, Rahman S, et al. Role of Nano-curcumin on carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) induced hepatotoxicity in rats. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2020;9:2168–76.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Khan FA, Zahoor M, Islam NU, Hameed R. Synthesis of cefixime and azithromycin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance their antimicrobial activity and dissolution rate. J Nanomater. 2016;2016:1–9. 10.1155/2016/6909085.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Mohamed MS, Abdelhafez WA, Zayed G, Samy AM. Optimization, in-vitro release and in-vivo evaluation of gliquidone nanoparticles. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2020;21:1–2. 10.1208/s12249-019-1577-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Kakran M, Sahoo NG, Li L, Judeh Z. Particle size reduction of poorly water soluble artemisinin via antisolvent precipitation with a syringe pump. Powder Technol. 2013;237:468–76.10.1016/j.powtec.2012.12.029Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Kakran M, Sahoo NG, Tan IL, Li L. Preparation of nanoparticles of poorly water soluble antioxidant curcumin by antisolvent precipitation methods. J Nanopart Res. 2012;14:1–11.10.1007/s11051-012-0757-0Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Kakran M, Sahoo NG, Li L, Judeh Z. Fabrication of quercetin nanoparticles by anti-solvent precipitation method for enhanced dissolution. Powder Technol. 2012;223:59–64.10.1016/j.powtec.2011.08.021Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Racault C, Langlais F, Naslain R. Solid-state synthesis and characterization of the ternary phase Ti3SiC2. J Mater Sci. 1994;29:3384–92. 10.1007/BF00352037.Suche in Google Scholar