Abstract

In this study, in vitro biological activities of both methanol and ethanol extracts of Arabis alpina subsp. brevifolia were investigated. Also, the phenolic components of this plant was examined in this study. The extracts were tested against the eight strains of food pathogens for their antimicrobial activities by utilizing minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and disc diffusion assay. The non-enzymatic antioxidant activities were determined according to scavenging of the free radical 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH). The phenolic compounds were analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The main component was ellagic acid for the methanol extract of stem-leaf, rutin for the ethanol extract of stem-leaf, and 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid for the methanol and ethanol extracts of fruit-flower. The ethanolic extracts of leaves revealed antibacterial activities against Salmonella Typhimurium (7 mm) while the ethanolic extracts of flowers demonstrated no activity against the test pathogens. The methanolic extracts of leaf-flower showed antibacterial activities against S. Typhimurium (7 mm). No activity was observed against C. albicans. The MIC value for four test bacteria was 13000 μg/mL. The ethanol extracts of A. alpina subsp. brevifolia exhibited the highest DPPH inhibition (76%). This study showed that A. alpina subsp. brevifolia possesses antioxidant and antimicrobial activities.

1 Introduction

The Brassicaceae family is one of the broad-spreaded and richly diverse families within the plant kingdom and contains many species (Arabidopsis, Brassica, Boechera, Thellungiella, Camelina, Raphanus and Arabis) that have economic, scientific and agricultural importance [1-3]. This family comprises 49 tribes, 325 genera and 3740 species which mainly spread in the temperate region of the world, and Turkey is extremely rich in terms of the diversity of this family, as well [4-6]. In the family, the genus of Arabis L. containing about 60 species is represented by 17 species in the Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands and by 22 species (24 taxa) in Turkey [7-9]. Arabis alpina L. in the mountain habitats of Anatolia, which is distributed on the alpine habitats, so named alpine rock-cress, emerges as model species in the ecological and evolutionary researches which have been conducted in recent years [10,11]. As a perennial herb, A. alpina L. subsp. brevifolia (DC.) Cullen is one of the two subspecies (brevifolia and caucasica) and generally grows on rocks and screes in Turkey [12].

Brassicaceae family has received a great deal of attention in recent years because of its antioxidative and antimicrobial properties [13-16]. It is one of the most studied family due to its rich phytochemical contents [17]. They have great importance in terms of preventing oxidative damage [18] and diseases like cancer, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s [19]. Karakoca et al. [20] report high chlorogenic acid in the methanolic root extract of Isatis floribunda, which is used to reduce the relative risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and Alzheimer’s disease [21-23]. Ethanol extracts of the leaf and seed of Eruca sativa have shown anti-secretory, cytoprotective, and anti-ulcer effects against gastric lesions [24]. Recent studies have indicated that the essential oils of the root-stem-leaf-fruit of Eruca vesicaria subsp. longirostris have shown significant antimicrobial activity against S. aureus, B. subtilis, B. amyloliquefaciens, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. enterica, and C. albicans [25]. Similarly, Rani et al. [26] report that the crude water extracts of the seed of Eruca sativa posses highest antibacterial activity against Enterobacter agglomerans and Hafnia alvei.

In scope of my knowledge, the present study is the first attempt to investigate A. alpina L. subsp. brevifolia (DC.) Cullen. The objectives of this study are to determine the phenolic compound composition of this plant, to examine antimicrobial activities of the various extracts of aboveground organs (leaf, flower) of the plant against various food pathogens, and to determine antioxidant capacity of the extracts.

2 Methods

2.1 Plant material

The samples of A. alpina subsp. brevifolia were collected from Burdur/ Turkey (37°41ʹ44.82ʺN, 30°20ʹ43.50ʺE; 1157m asl.) in its blooming season in May 2015. The identification of the specimens was made according to Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands [12,27], and the samples were deposited at the Botanical Research Laboratory of the Biology Department, Mehmet Akif Ersoy University (voucher number: Balpinar, 1551).

2.2 Microorganisms

In order to specify in vitro antimicrobial activities, the following food pathogens were utilized in this study: Bacillus subtilis RSKK245, Candida albicans RSKK02029, Escherichia coli ATCC11229, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC8093, Listeria monocytogenes ATCC7644, Salmonella Typhimurium RSKK19, Staphylococcus aureus RSKK2392 and Yersinia enterocolitica NCTC11174. These microorganisms were supplied from ATCC (American Type Culture Collection, USA), RSKK (Refik Saydam National Type Culture Collection, Turkey) and NCTC (North Central Texas College, USA).

2.3 Cultivation of microorganisms

Among these food-borne pathogens, the yeast C. albicans was cultivated in Sabouraud Dextrose agar plates (SDA, Merck) at 30°C for 24 h, and the other bacteria were in Mueller-Hinton agar plates (MHA, Merck) at 37°C for 24 h.

2.4 Extraction process

The above-ground organs of plant were washed 2-3 times in running water and once in sterile water. The plant materials were divided into their pieces (stem, leaf and flower). Next, they were air-dried and milled by using a blender. The homogenized fine powder was stored at 4°C in a room which is away from natural sunlight until extraction process. These materials (40 g) were extracted separately in a soxhlet apparatus (Isotex) with 250 ml methanol and ethanol solvents. Time of extraction process was 4-8 h. The purpose of preparing both methanol and ethanol extracts of the plant is that the presence of polar groups (e.g. phenolics, alcoholoids etc.) which shows antimicrobial activity and are highly soluble in these two solvents. The obtained extracts were evaporated by using an evaporator and transferred into the sterilized falcon tubes which contain their own solvents (i.e. the material extracted in methanol was placed in falcon tubes containing methanol; the material extracted in ethanol was transferred in the tubes containing ethanol). The extracts prepared in the concentration of 200 mg/ ml were kept under refrigerated conditions until the analysis.

2.5 HPLC analysis of phenolic compounds in the extracts

The HPLC analysis (described by Caponio et al. [28]) that was slightly modified was used to determine phenolic components. A modular Shimadzu Prominence Auto Sampler (SIL 20 ACHT) HPLC system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) comprised of a LC-20AT pump, a CTO-10ASVp column oven, a SPD-M20A DAD detector, a 20ACBM interface was utilized in the analysis. The flow rate of run was maintained at 0.8 mL/min, and the detection wavelength was 240 nm for ellagic acid, 260 nm for epicatechin, 280 nm for gallic acid, 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic, 4-hydroxybenzoic, caffeic, cinnamic acids and naringin, 320 nm for 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic, chlorogenic, vanillic, p-coumaric, ferulic acids, and 360 nm for rutin and quercetin. A Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 (4.6×250 mm) 5 μm column was used and its temperature was 40°C. The separation was executed by using a gradient program with a two-solvent system (solution A was 3% formic acid, solution B was methanol). Injection volume was 100 μL. Data were acquired by Shimadzu LC Solution software.

2.6 In vitro antimicrobial assay

In order to determine antimicrobial activities, disc diffusion assay was used. The organic solvents of this study were ethanol and methanol. The turbidity of the active cultures was equalled to 0.5 McFarland (1.5 x 108 cfu/mL), and then they were inoculated to the plates (0.1 ml) under aseptic conditions. The plant extracts (45 μL from 200 mg/mL concentration) were ingrained into blank discs (6mm) and they were placed on plate surface. After the incubation, the diameter of inhibition zones was measured in millimeters. The solvents of extraction (ethanol and methanol) were defined as negative control group while ampicillin (10 μg), tetracycline (30 μg) and nystatin (100 μg) were used as positive control group [29]. All measurements were performed in triplicate parallel cultures, and the values obtained were given in average.

2.7 Determination of minimal inhibitory concentration

Broth dilution method was employed for determination of MIC values of the extracts. The active culture concentrations were standardized to 0.5 McFarland and all experiments were conducted in 2 mL Mueller-Hinton Broth. Serial dilutions, each of their concentrations was 13000; 6500; 3250; 1625; 812.5 μg/mL, were prepared, and the same amounts of active cultures (100 μL) were inoculated into each of them [30,31]. After incubation at 37°C for 24 h and the lowest concentration was defined as MIC value.

2.8 Non-enzymatic antioxidant assay

The determination of antioxidant activity was accomplished by using DPPH radical scavenging assay. The absorbance of the extracts was measured at a wavelength of 515 nm in an UV/Vis spectrophotometer (Optizen POP, Korea) [32]. The methanol DPPH solution was used as control. Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethychroman-2-carboxylic acid; Sigma) was used as reference standard and the results were given through the equivalent of mM Trolox/g DW (TE).

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

3 Results

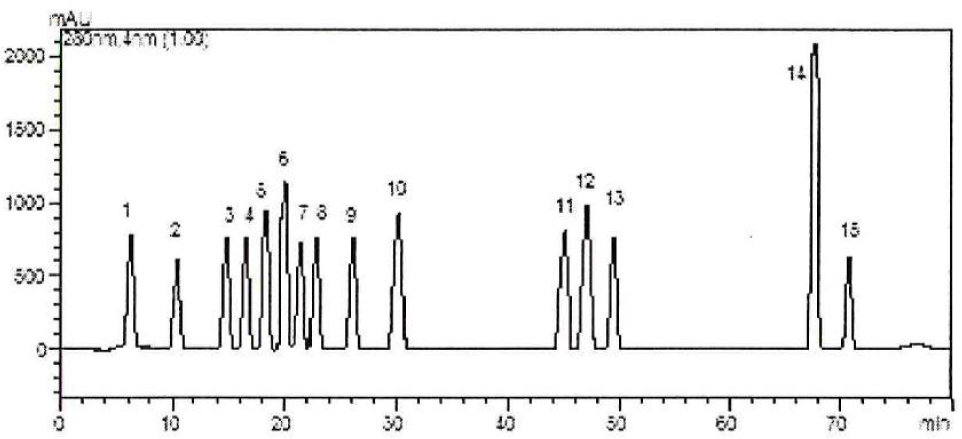

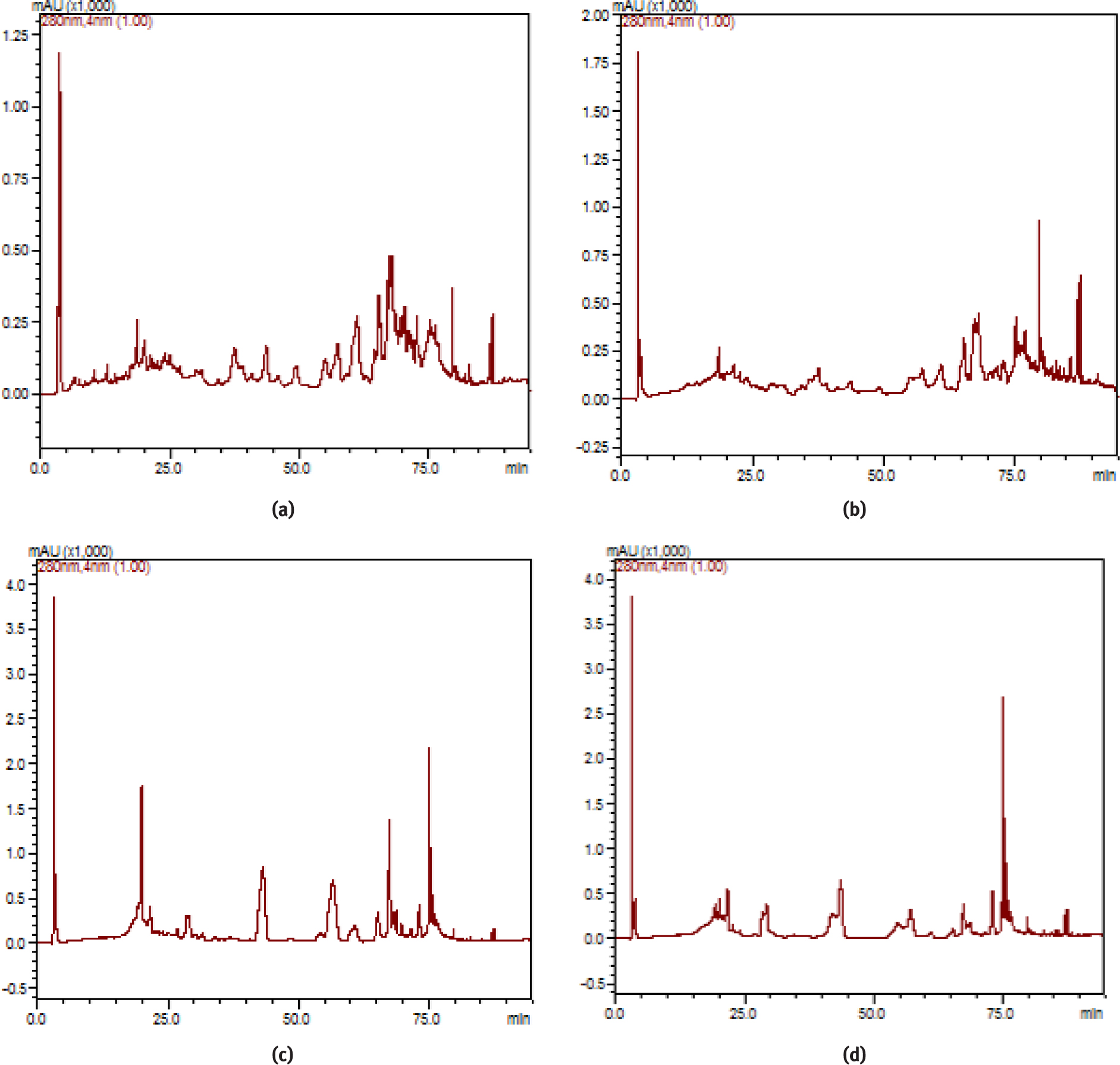

The analysis of phenolic acid compounds in A. alpina subsp. brevifolia was performed utilizing the HPLC technique. A total of 15 phenolic standards were used and 14 phenolic components were determined in this study (Table 1). The results of the analysis showed that the major components were ellagic acid, which was followed by rutin, caffeic acid and epicatechin, for the methanolic stem-leaf extract, rutin for the ethanolic stem-leaf extract, 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid for the methanolic fruit-flower extract, and 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid for the ethanolic fruit-flower extract. The chromatogram for the standards and the HPLC chromatograms of the various extracts are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively.

Standard chromatogram; 1 = gallic acid, 2 = 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid, 3 = 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, 4 = 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid, 5 = chlorogenic acid, 6 = vanillic acid, 7 = epicatechin, 8 = caffeic acid, 9 = p-coumaric acid, 10 = ferulic acid, 11 = rutin, 12 = ellagic acid, 13 = naringin, 14 = cinnamic acid, 15 = quercetin.

HPLC chromatograms of A. alpina subsp. brevifolia. a: methanol stem-leaf extract, b: ethanol stem-leaf extract, c: methanol fruit-flower extract, d: ethanol fruit-flower extract.

Phenolic compositions of the various extracts from A. alpina subsp. brevifolia.

| The various extracts of A. alpina subsp. brevifolia (μg/mg) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic compounds | A | B | C | D |

| Gallic acid | 0.96 | 2.91 | 3.14 | 1.96 |

| 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid | 0.65 | 2.69 | 3.4 | 2.25 |

| 4-hydroxybenzoic acid | 2.71 | 5.98 | 19.19 | 20.62 |

| 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid | 141.76 | 353.33 | 1458..09 | 14672.68 |

| Chlorogenic acid | 7.73 | 24.23 | 32.7 | 83.22 |

| Vanillic acid | 49.79 | 110.08 | 124.71 | 109.14 |

| Epicatechin | 212.86 | 73.01 | 663.83 | 136.25 |

| Caffeic acid | 278.37 | 315.72 | 847.90 | 543.91 |

| p-coumaric acid | (nd) | (nd) | (nd) | (nd) |

| Ferulic acid | 8.07 | 12.04 | 1.23 | 0.01 |

| Rutin | 300.43 | 1238.77 | 582.93 | (nd) |

| Ellagic acid | 319.01 | 493.19 | 726.41 | 157.09 |

| Naringin | 119.60 | 167.27 | 32.80 | 267.31 |

| Cinnamic acid | 25.09 | 17.98 | 6.72 | 13.30 |

| Quercetin | 131.374 | 155.39 | 289.904 | 322.974 |

A:methanol stem-leaf extract, B: ethanol stem-leaf extract, C: methanol fruit-flower extract, D: ethanol fruit-flower extract, (nd): not determined

Using disc diffusion assay, which it was utilized as a method for determining antimicrobial activity in this study, it was determined whether the various extracts of some parts of A. alpina subsp. brevifolia would show activity or not against the food-borne pathogens by measuring their inhibition zone. The results indicated that no activity was observed in the ethanol extract of the flowers while the ethanol extract of the leaves revealed antibacterial activities against S. Typhimurium RSKK19 (7 mm). The methanol extracts of the leaves and the flowers showed antibacterial activities against S. Typhimurium RSKK19 (7 mm). Moreover, neither ethanol nor methanol extracts of the plant parts exhibited antifungal activity against C. albicans RSKK02029. The results are illustrated in Table 2.

Antimicrobial activities of A. alpina subsp. brevifolia against food-borne pathogens (200 mg/mL).

| Inhibition zone (mm) Extracts of Plant Parts | Antibiotics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microorganisms | Leaf Ethanol | Flower | Leaf Methanol | Flower | TE | NS | A |

| Bacillus subtilis RSKK245 | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | nt | nt | 10±0.001 |

| Staphylococcus aureus RSKK2392 | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | nt | nt | 10±0.001 |

| Salmonella Typhimurium RSKK19 | 7±0.01 | (-) | 7±0.01 | 7±0.01 | 14±0.001 | nt | nt |

| Enterococcus faecalis ATCC8093 | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | nt | nt | - |

| Escherichia coli ATCC11229 | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | 14±0.001 | nt | nt |

| Listeria monocytogenes ATCC7644 | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | nt | nt | 12±0.001 |

| Yersinia enterocolitica NCTC11174 | (-) | (-) | 7±0.01 | (-) | 20±0.001 | nt | nt |

| Candida albicans RSKK02029 | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | nt | 7±0.001 | nt |

(-):no inhibition, nt: not tested, TE: tetracycline (30 μg), NS: nystatin (100 μg), A: ampicillin (10 μg)

The other test applied in this study was MIC which was conducted in order to determine the antibacterial activity [30,31]. According to the results, the MIC value of A. alpina subsp. brevifolia extracts was determined to be 13000 μg/mL (Table 3).

Minimum inhibitory concentrations of A. alpina subsp. brevifolia (μg/mL).

| Microorganisms | LE | FE | LM | FM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salmonella | 13000 | (nt) | 13000 | 13000 |

| Typhimurium RSKK19 | ||||

| Yersinia enterocolitica | (nt) | (nt) | 13000 | (nt) |

| NCTC11174 |

LE:leaf ethanol extract, FE: flower ethanol extract, LM: leaf methanol extract, FM: flower methanol extract, (nt): not tested

In order to characterize the non-enzymatic antioxidant activities of the plant extracts, DPPH assay was used. The highest DPPH scavenging capacity was 76.3% in the ethanol extracts of the flowers-fruits-seeds of A. alpina subsp. brevifolia. Its trolox equivalent was 2.134 mM/ g DW (Table 4).

DPPH radical scavenging activities of A. alpina subsp. brevifolia extracts.

| Radical scavenging activity | Stem-Leaf | Flower-Fruit-Seed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Methanol | Ethanol | Methanol | |

| DPPH (%) | 0 | 70.0 | 76.3 | 74.7 |

| Trolox equivalent (mM/g DW) | 0 | 1.96 | 2.1 | 2.06 |

DW:dry weight

4 Discussion

The present analysis showed the presence of tannins (ellagic acid, epicatechin), flavonoids (rutin) and phenolic acids (caffeic acid, 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid) in various extracts of the different parts of A. alpina subsp. brevifolia (Table 1). Recent pharmacological studies on tannins have revealed that they have antibacterial [33,34], anticarcinogenic [35], and antioxidant [36,37] properties. Flavonoids have been previously associated with antioxidant properties [38]. Among all phenolic compounds identified in A. alpina subsp. brevifolia, 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid showed the highest level, and it has remarkable antioxidant characteristics against oxidative stress [39].

Because of its economic value, Brassicaceae has been in the centre of attraction among the studies of antimicrobial activity. For instance, Razavi et al. [40] and Esmaeili et al. [19] reported there were 27.7 and 20 mm zones for B. subtilis in the methanol extracts of Crambe orientalis (Brassicaceae) and Malcolmia africana (Brassicaceae), respectively. Moreover, Razavi et al. [40] reported the presence of 23 mm activity zone for E. coli while Esmaeili et al. [19] found no activity against the same bacteria. In the studies by Karakoca et al. [20] regarding the flower ethanol extracts of Isatis floribunda (Brassicaceae), it was detected 12.9 mm activity zone for S. aureus and 13.5 mm for E. coli. In the present study, 7 mm zone was obtained against the gram negative bacteria S. Typhimurium while there was no activity against E. coli. However, these bacteria are more complex regarding the structure of cell membrane in comparison to the gram positive bacteria [25]. Generally it was difficult to determine striking antimicrobial activity against Gram negative bacteria. Another study supports my results. For example, Esmaeili et al. [19] found no inhibition zone against the second Gram negative bacteria at issue.

The results of this study showed that the MIC value was 13000 μg/mL both in the ethanolic extracts of the leaves and the methanolic extracts of flowers against S. Typhimurium RSKK19 and in the methanolic extracts of the leaves against Y. enterocolitica NCTC11174. In the studies of Crambe orientalis (Brassicaceae), this value was measured as 500 μg/mL for E. coli by Razavi et al. [40]. MIC result of this study is higher than Razavi’s result. The possible reason of their finding may come from a phytochemical called isothiocyanates which is responsible for some biological activities [40]. Grosso et al. [41] found the MIC value of 125 mg/mL in the methanol extracts of Capsella bursa-pastoris for S. Typhimurium and E. coli. The MIC result of this study is better than the result of Grosso et al. [41].

In this study, the highest inhibitory percentage of DPPH was 76.3% and the trolox equivalent was 2.1 mM/g DW. The highest DPPH scavenging activity was determined by Karakoca et al. [20] in the flower extracts of Isatis floribunda (89.6%). Omri et al. [25] recorded the radical activity as 56.3% in the leaf extracts and 83.6% in the fruit extracts of Eruca vesicaria subsp. longirostris. These results are similar to result of the present study. The studies conducted on the members of Brassicaceae family report that there is a high correlation between antioxidant activity and polyphenolic contents [25].

In the present study, the phenolic components of A. alpina subsp. brevifolia is reported for the first time. It indicates that this species is an interesting source of polyphenols and phenolic acids. This study is also the first attempt in utilizing antimicrobial tests on the various extracts of the different body parts (leaf, flower) of A. alpina subsp. brevifolia. Besides, it differs from the others in terms of the variety of bacteria used in the tests. The findings obtained in this research reveal that the extracts of the leaves of A. alpina subsp. brevifolia generally indicate higher antimicrobial activity than the extracts of the flowers, and that the extracts of the flower-fruit-seed of this plant have a high antioxidant capacity (Table 2 and 4). The data of this study indicate that A. alpina subsp. brevifolia may be used as a potential source of natural antioxidant and antibacterial agents. Nevertheless, I am of the opinion that Brassicaceae family, which is rich in isothiocynate derivatives, should be further investigated in in vivo and in vitro studies.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Mehmet Akif Ersoy University Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit (No. 0338-NAP-16). No sponsors have got involved in any stage of the study; which are collection, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscripting of the study and making decision on publishing the results.The author thanks Assoc. Prof. Dr. Gulten OKMEN for her contributions in the laboratory studies.

The HPLC analysis of phenolic compounds in the extracts was conducted in Scientific and Technological Research and Application Center at Mehmet Akif Ersoy University (Burdur-Turkey); (Protocol no: E.5045).

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Anjum N.A., The plant family Brassicaceae: An introduction, In: Anjum N.A., Ahmad I., Pereira M., Duarte A., Umar S., Khan N. (Eds.), The plant family Brassicaceae, vol. 21, Springer, Dordrecht, 2012.10.1007/978-94-007-3913-0Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Hohmann N., Wolf E.M., Lysak M.A., Koch M.A., A time-calibrated road map of Brassicaceae species radiation and evolutionary history, The Plant Cell, 2015, 27, 2770-2784.10.1105/tpc.15.00482Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Lopez L., Wolf E.M., Pires J.C., Edger P.P., Koch M.A., Molecular resources from transcriptomes in the Brassicaceae family, Frontiers in Plant Science, 2017, 8, 1488.10.3389/fpls.2017.01488Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Al-Shehbaz I.A., A generic and tribal synopsis of the Brassicaceae (Cruciferae), Taxon, 2012, 61, 931-954.10.1002/tax.615002Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Kiefer M., Schmickl R., German D.A., Mandáková T., Lysak M.A., Al-Shehbaz I.A., et al., BrassiBase: Introduction to a novel knowledge database on Brassicaceae evolution, Plant Cell Physiol., 2013, 55, 1-9.10.1093/pcp/pct158Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Dönmez A., Aydın Z.U., Koch M.A., Aubrieta alshehbazii (Brassicaceae), a new species from Central Turkey, Phytotaxa, 2017, 299, 103-110.10.11646/phytotaxa.299.1.8Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Koch M.A., Karl R., Kiefer C., Al-Shehbaz I.A., Colonizing the American continent: Systematics of the genus Arabis in North America (Brassicaceae), Am. J. Bot., 2010, 97, 1040-1057.10.3732/ajb.0900366Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Mutlu B., Erik S., Distribution maps and new IUCN threat categories for the genus of Arabis, Pseudoturritis and Turritis (Brassicaceae) in Turkey, Hacettepe J. Biol. & Chem., 2015, 43, 133-143.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Özüdoğru S., Fırat M., Arabis watsonii (P.H. Davis) F.K. Mey.: An overlooked cruciferous species from eastern Anatolia and its phylogenetic position, PhytoKeys, 2016, 75, 57-68.10.3897/phytokeys.75.10568Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Toräng P., Wunder J., Obeso J.R., Herzog M., Coupland G., Ågren J., Large scale adaptive differentiation in the alpine perennial herb Arabis alpina, New Phytol., 2015, 206, 459-470.10.1111/nph.13176Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Pavlova D., Laporte F., Ananiev E.D., Herzog M., Pollen morphological studies on Arabis alpina L. (Brassicaceae) populations from the alps and the Rila mountains, Genet. Plant Physiol., 2016, 6, 27-42.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Cullen J., Arabis L., In: Davis P.H.(Eds.), Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands, volume 1, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 1965.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Cartea M.E., Francisco M., Soengas P., Velasco P., Phenolic compounds in Brassica vegetables, Molecules, 2010, 16, 251280.10.3390/molecules16010251Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Koubaa M., Driss D., Bouaziz F., Ghorbel R.E., Chaabouni S.E., Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of solvent extract obtained from rocket (Eruca sativa L.) flowers, Free Radicals & Antioxidants, 2015, 5, 29-34.10.5530/fra.2015.1.5Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Alqahtani F.Y., Aleanizy F.S., Mahmoud A.Z., Farshori N.N., Alfaraj R., Al-sheddi E.S., et al., Chemical composition and antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities of Lepidium sativum seed oil, Saudi J. Biol. Sci., 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2018.05.007.10.1016/j.sjbs.2018.05.007Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Rashid M.A., Akhtar M.N., Ashraf A., Nazir S., Ijaz A., Omar N.A., et al., Chemical composition and antioxidant, antimicrobial and haemolytic activities of Crambe cordifolia roots, Farmacia, 2018, 66, 165-171.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Rizwana H., Alwhibi M.S., Khan F., Soliman D.A., Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of Eruca sativa seeds against pathogenic bacteria and fungi, J. Anim. Plant. Sci., 2016, 26, 1859-1871.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Boutemak K., Chekirine A., Tail G., Phytochemical screening, antioxidant and insecticidal activities of Ajuga iva, Int. J. Biol. Med. Sci., 2016, 1, 1-5.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Esmaeili A., Moaf L., Rezazadeh S., Ayyari M., Antioxidant and antibacterial activity of various extracts of Malcolmia africana (L.) R. Br., Zahedan J. Res. Med. Sci., 2014, 16, 6-11.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Karakoca K., Ozusaglam M., Cakmak Y., Erkul S.K., Antioxidative, antimicrobial and cytotoxic properties of Isatis floribunda Boiss. ex Bornm. extracts, EXCLI J., 2013, 12, 150167.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Lindsay J., Laurin D., Verreault R., Hebert R., Helliwell B., Hill G.B., et al., Risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective analysis from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging, Am. J. Epidemiol., 2002, 156, 445-453.10.1093/aje/kwf074Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Salazar-Martinez E., Willett W.C., Ascherio A., Manson J.E., Leitzmann M.F., Stampfer M.J., et al., Coffee consumption and risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus, Ann. Intern. Med., 2004, 140, 1-8.10.7326/0003-4819-140-1-200401060-00005Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Ranheim T., Halvorsen B., Coffee consumption and human health: beneficial or detrimental? Mechanisms for effects of coffee consumption on different risk factors for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus, Mol. Nutr. Food Res., 2005, 49, 274-284.10.1002/mnfr.200400109Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Alqasoumi S., Carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity: protective effect of “Rocket” Eruca sativa L. in rats., Am. J. Chinese Med., 2010, 38, 75-88.10.1142/S0192415X10007671Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Omri H.A., Mosbah H., Majouli K., Hlila M.B., Jannet H.B., Flamini G., et al., Chemical composition and biological activities of Eruca vesicaria subsp. longirostris essential oil, Pharm. Biol., 2016, 54, 2236-2243.10.3109/13880209.2016.1151445Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Rani I., Akhund S., Suhail M., Abro H., Antimicrobial potential of seed extract of Eruca sativa, Pa k. J. Bot., 2010, 42, 29492953.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Davis P.H., Mill R.R., Tan K., Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands, volume 10, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 1988.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Caponio F., Alloggio V., Gomes T., Phenolic compounds of virgin olive oil: influence of paste preparation techniques, Food Chem., 1999, 64, 203-209.10.1016/S0308-8146(98)00146-0Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Bauer A.W., Kirby W.M.M., Sherris J.C., Turck M., Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method, Am. J. Clin. Pathol., 1966, 45, 493-496.10.1093/ajcp/45.4_ts.493Suche in Google Scholar

[30] CLSI, Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility test for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard, 6th ed., National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Philadelphia, 2003.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] CLSI, Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 16th informational supplement, National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Philadelphia, 2006.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Brand-Williams W., Cuvelier M.E., Berset C., Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity, LWT-Food Sci. Technol., 1995, 28, 25-30.10.1016/S0023-6438(95)80008-5Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Oliveira R., Lima E.O., Vieira W.L., Freire K.L., Trajano V., Lima I.O., et al., Estudo da interferência de óleos essenciais sobre a atividade de alguns antibióticos usados na clínica, Rev. Bras. Farmacogn., 2006, 16, 77-82.10.1590/S0102-695X2006000100014Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Widsten P., Cruz C.D., Fletcher G.C., Pajak M.A., McGhie T.K., Tannins and extracts of fruit by products: Antibacterial activity against foodborne bacteria and antioxidant capacity, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2014, 62, 11146-11156.10.1021/jf503819tSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Yıldırım I. and Kutlu T., Anticancer Agents: Saponin and Tannin. Int. J. Biol. Chem., 2015, 9, 332-340.10.3923/ijbc.2015.332.340Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Namiki M., Antioxidants/antimutagens in food, Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr., 1990, 29, 273-300.10.1007/978-1-4684-5182-5_11Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Chung K.T., Wong T.Y., Wei C.I., Huang Y.W., Lin Y., Tannins and human health: a review, Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr., 1998, 38, 421-464.10.1080/10408699891274273Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Rosa E.A., Silva B.C., Silva F.M., Tanaka C.M.A., Peralta R.M., Oliveira C.M.A., et al., Flavonoides e atividade antioxidante em Palicourea rigida Kunth, Rubiaceae, Rev. Bras. Farmacogn., 2010, 20, 484-488.10.1590/S0102-695X2010000400004Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Joshi R., Gangabhagirathi R., Venu S., Adhikari S., Mukherjee T., Antioxidant activity and free radical scavenging reactions of gentisic acid: in-vitro and pulse radiolysis studies, Free Radic. Res., 2012, 46, 11-20.10.3109/10715762.2011.633518Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Razavi S.M., Zarrini G., Zahri S., Ghasemi K., Mohammadi S., Biological activity of Crambe orientalis L. growing in Iran, Pharmacognosy Res., 2009, 1, 125-129.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Grosso C., Vinholes J., Silva R.S., Pinho P.G., Gonçalves R.F., Valentão P., et al., Chemical composition and biological screening of Capsella bursa-pastoris, Rev. Bras. Farmacogn., 2011, 21, 635-643.10.1590/S0102-695X2011005000107Suche in Google Scholar

© 2018 N. Balpinar et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- The effect of CuO modification for a TiO2 nanotube confined CeO2 catalyst on the catalytic combustion of butane

- The preparation and antibacterial activity of cellulose/ZnO composite: a review

- Linde Type A and nano magnetite/NaA zeolites: cytotoxicity and doxorubicin loading efficiency

- Performance and thermal decomposition analysis of foaming agent NPL-10 for use in heavy oil recovery by steam injection

- Spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, UV, 1H and 13C NMR) insights, electronic profiling and DFT computations on ({(E)-[3-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-1-phenylpropylidene] amino}oxy)(4-nitrophenyl)methanone, an imidazole-bearing anti-Candida agent

- A Simplistic Preliminary Assessment of Ginstling-Brounstein Model for Solid Spherical Particles in the Context of a Diffusion-Controlled Synthesis

- M-Polynomials And Topological Indices Of Zigzag And Rhombic Benzenoid Systems

- Photochemical Transformation of some 3-benzyloxy-2-(benzo[b]thiophen-2-yl)-4Hchromen-4-ones: A Remote Substituent Effect

- Dynamic Changes of Secondary Metabolites and Antioxidant Activity of Ligustrum lucidum During Fruit Growth

- Studies on the flammability of polypropylene/ammonium polyphosphate and montmorillonite by using the cone calorimeter test

- DSC, FT-IR, NIR, NIR-PCA and NIR-ANOVA for determination of chemical stability of diuretic drugs: impact of excipients

- Antioxidant and Hepatoprotective Effects of Methanolic Extracts of Zilla spinosa and Hammada elegans Against Carbon Tetrachlorideinduced Hepatotoxicity in Rats

- Prunus cerasifera Ehrh. fabricated ZnO nano falcates and its photocatalytic and dose dependent in vitro bio-activity

- Organic biocides hosted in layered double hydroxides: enhancing antimicrobial activity

- Experimental study on the regulation of the cholinergic pathway in renal macrophages by microRNA-132 to alleviate inflammatory response

- Synthesis, characterization, in-vitro antimicrobial properties, molecular docking and DFT studies of 3-{(E)-[(4,6-dimethylpyrimidin-2-yl)imino]methyl} naphthalen-2-ol and Heteroleptic Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Zn(II) complexes

- M-Polynomials and Topological Indices of Dominating David Derived Networks

- Human Health Risk Assessment of Trace Metals in Surface Water Due to Leachate from the Municipal Dumpsite by Pollution Index: A Case Study from Ndawuse River, Abuja, Nigeria

- Analysis of Bowel Diseases from Blood Serum by Autofluorescence and Atomic Force Microscopy Techniques

- Hydrographic parameters and distribution of dissolved Cu, Ni, Zn and nutrients near Jeddah desalination plant

- Relationships between diatoms and environmental variables in industrial water biotopes of Trzuskawica S.A. (Poland)

- Optimum Conversion of Major Ginsenoside Rb1 to Minor Ginsenoside Rg3(S) by Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Acid Hydrolysis Treatment

- Antioxidant, Anti-microbial Properties and Chemical Composition of Cumin Essential Oils Extracted by Three Methods

- Regulatory mechanism of ulinastatin on autophagy of macrophages and renal tubular epithelial cells

- Investigation of the sustained-release mechanism of hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose skeleton type Acipimox tablets

- Bio-accumulation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Grey Mangrove (Avicennia marina) along Arabian Gulf, Saudi Coast

- Dynamic Change of Secondary Metabolites and spectrum-effect relationship of Malus halliana Koehne flowers during blooming

- Lipids constituents from Gardenia aqualla Stapf & Hutch

- Effect of using microwaves for catalysts preparation on the catalytic acetalization of glycerol with furfural to obtain fuel additives

- Effect of Humic Acid on the Degradation of Methylene Blue by Peroxymonosulfate

- Serum containing drugs of Gua Lou Xie Bai decoction (GLXB-D) can inhibit TGF-β1-Induced Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in A549 Cells

- Antiulcer Activity of Different Extracts of Anvillea garcinii and Isolation of Two New Secondary Metabolites

- Analysis of Metabolites in Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz Dry Red Wines from Shanxi by 1H NMR Spectroscopy Combined with Pattern Recognition Analysis

- Can water temperature impact litter decomposition under pollution of copper and zinc mixture

- Released from ZrO2/SiO2 coating resveratrol inhibits senescence and oxidative stress of human adipose-derived stem cells (ASC)

- Validated thin-layer chromatographic method for alternative and simultaneous determination of two anti-gout agents in their fixed dose combinations

- Fast removal of pollutants from vehicle emissions during cold-start stage

- Review Article

- Catalytic activities of heterogeneous catalysts obtained by copolymerization of metal-containing 2-(acetoacetoxy)ethyl methacrylate

- Antibiotic Residue in the Aquatic Environment: Status in Africa

- Regular Articles

- Mercury fractionation in gypsum using temperature desorption and mass spectrometric detection

- Phytosynthetic Ag doped ZnO nanoparticles: Semiconducting green remediators

- Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Induced by SMAD4 Activation in Invasive Growth Hormone-Secreting Adenomas

- Physicochemical properties of stabilized sewage sludge admixtures by modified steel slag

- In Vitro Cytotoxic and Antiproliferative Activity of Cydonia oblonga flower petals, leaf and fruit pellet ethanolic extracts. Docking simulation of the active flavonoids on anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2

- Synthesis and Characterization of Pd exchanged MMT Clay for Mizoroki-Heck Reaction

- A new selective, and sensitive method for the determination of lixivaptan, a vasopressin 2 (V2)-receptor antagonist, in mouse plasma and its application in a pharmacokinetic study

- Anti-EGFL7 antibodies inhibit rat prolactinoma MMQ cells proliferation and PRL secretion

- Density functional theory calculations, vibration spectral analysis and molecular docking of the antimicrobial agent 6-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-ylmethyl)-5-ethyl-2-{[2-(morpholin-4-yl)ethyl] sulfanyl}pyrimidin-4(3H)-one

- Effect of Nano Zeolite on the Transformation of Cadmium Speciation and Its Uptake by Tobacco in Cadmium-contaminated Soil

- Effects and Mechanisms of Jinniu Capsule on Methamphetamine-Induced Conditioned Place Preference in Rats

- Calculating the Degree-based Topological Indices of Dendrimers

- Efficient optimization and mineralization of UV absorbers: A comparative investigation with Fenton and UV/H2O2

- Metabolites of Tryptophane and Phenylalanine as Markers of Small Bowel Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

- Adsorption and determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water through the aggregation of graphene oxide

- The role of NR2C2 in the prolactinomas

- Chromium removal from industrial wastewater using Phyllostachys pubescens biomass loaded Cu-S nanospheres

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Preparation of Calcium Fluoride using Phosphogypsum by Orthogonal Experiment

- The mechanism of antibacterial activity of corylifolinin against three clinical bacteria from Psoralen corylifolia L

- 2-formyl-3,6-bis(hydroxymethyl)phenyl benzoate in Electrochemical Dry Cell

- Electro-photocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin using calcium titanate

- Effect of Malus halliana Koehne Polysaccharides on Functional Constipation

- Structural Properties and Nonlinear Optical Responses of Halogenated Compounds: A DFT Investigation on Molecular Modelling

- DMFDMA catalyzed synthesis of 2-((Dimethylamino)methylene)-3,4-dihydro-9-arylacridin-1(2H)-ones and their derivatives: in-vitro antifungal, antibacterial and antioxidant evaluations

- Production of Methanol as a Fuel Energy from CO2 Present in Polluted Seawater - A Photocatalytic Outlook

- Study of different extraction methods on finger print and fatty acid of raw beef fat using fourier transform infrared and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- Determination of trace fluoroquinolones in water solutions and in medicinal preparations by conventional and synchronous fluorescence spectrometry

- Extraction and determination of flavonoids in Carthamus tinctorius

- Therapeutic Application of Zinc and Vanadium Complexes against Diabetes Mellitus a Coronary Disease: A review

- Study of calcined eggshell as potential catalyst for biodiesel formation using used cooking oil

- Manganese oxalates - structure-based Insights

- Topological Indices of H-Naphtalenic Nanosheet

- Long-Term Dissolution of Glass Fibers in Water Described by Dissolving Cylinder Zero-Order Kinetic Model: Mass Loss and Radius Reduction

- Topological study of the para-line graphs of certain pentacene via topological indices

- A brief insight into the prediction of water vapor transmissibility in highly impermeable hybrid nanocomposites based on bromobutyl/epichlorohydrin rubber blends

- Comparative sulfite assay by voltammetry using Pt electrodes, photometry and titrimetry: Application to cider, vinegar and sugar analysis

- MicroRNA delivery mediated by PEGylated polyethylenimine for prostate cancer therapy

- Reversible Fluorescent Turn-on Sensors for Fe3+ based on a Receptor Composed of Tri-oxygen Atoms of Amide Groups in Water

- Sonocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in aqueous solution using Fe-doped TiO2 nanoparticles under mechanical agitation

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Production and Analysis of Recycled Ammonium Perrhenate from CMSX-4 superalloys

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- New phosphorus biofertilizers from renewable raw materials in the aspect of cadmium and lead contents in soil and plants

- Survey of content of cadmium, calcium, chromium, copper, iron, lead, magnesium, manganese, mercury, sodium and zinc in chamomile and green tea leaves by electrothermal or flame atomizer atomic absorption spectrometry

- Biogas digestate – benefits and risks for soil fertility and crop quality – an evaluation of grain maize response

- A numerical analysis of heat transfer in a cross-current heat exchanger with controlled and newly designed air flows

- Freshwater green macroalgae as a biosorbent of Cr(III) ions

- The main influencing factors of soil mechanical characteristics of the gravity erosion environment in the dry-hot valley of Jinsha river

- Free amino acids in Viola tricolor in relation to different habitat conditions

- The influence of filler amount on selected properties of new experimental resin dental composite

- Effect of poultry wastewater irrigation on nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon contents in farmland soil

- Response of spring wheat to NPK and S fertilization. The content and uptake of macronutrients and the value of ionic ratios

- The Effect of Macroalgal Extracts and Near Infrared Radiation on Germination of Soybean Seedlings: Preliminary Research Results

- Content of Zn, Cd and Pb in purple moor-grass in soils heavily contaminated with heavy metals around a zinc and lead ore tailing landfill

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Synthesis of (±)-3,4-dimethoxybenzyl-4-methyloctanoate as a novel internal standard for capsinoid determination by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS(QTOF)

- Repellent activity of monoterpenoid esters with neurotransmitter amino acids against yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti

- Effect of Flammulina velutipes (golden needle mushroom, eno-kitake) polysaccharides on constipation

- Bioassay-directed fractionation of a blood coagulation factor Xa inhibitor, betulinic acid from Lycopus lucidus

- Antifungal and repellent activities of the essential oils from three aromatic herbs from western Himalaya

- Chemical composition and microbiological evaluation of essential oil from Hyssopus officinalis L. with white and pink flowers

- Bioassay-guided isolation and identification of Aedes aegypti larvicidal and biting deterrent compounds from Veratrum lobelianum

- α-Terpineol, a natural monoterpene: A review of its biological properties

- Utility of essential oils for development of host-based lures for Xyleborus glabratus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae), vector of laurel wilt

- Phenolic composition and antioxidant potential of different organs of Kazakh Crataegus almaatensis Pojark: A comparison with the European Crataegus oxyacantha L. flowers

- Isolation of eudesmane type sesquiterpene ketone from Prangos heyniae H.Duman & M.F.Watson essential oil and mosquitocidal activity of the essential oils

- Comparative analysis of the polyphenols profiles and the antioxidant and cytotoxicity properties of various blue honeysuckle varieties

- Special Issue on ICCESEN 2017

- Modelling world energy security data from multinomial distribution by generalized linear model under different cumulative link functions

- Pine Cone and Boron Compounds Effect as Reinforcement on Mechanical and Flammability Properties of Polyester Composites

- Artificial Neural Network Modelling for Prediction of SNR Effected by Probe Properties on Ultrasonic Inspection of Austenitic Stainless Steel Weldments

- Calculation and 3D analyses of ERR in the band crack front contained in a rectangular plate made of multilayered material

- Improvement of fuel properties of biodiesel with bioadditive ethyl levulinate

- Properties of AlSi9Cu3 metal matrix micro and nano composites produced via stir casting

- Investigation of Antibacterial Properties of Ag Doped TiO2 Nanofibers Prepared by Electrospinning Process

- Modeling of Total Phenolic contents in Various Tea samples by Experimental Design Methods

- Nickel doping effect on the structural and optical properties of indium sulfide thin films by SILAR

- The effect mechanism of Ginnalin A as a homeopathic agent on various cancer cell lines

- Excitation functions of proton induced reactions of some radioisotopes used in medicine

- Oxide ionic conductivity and microstructures of Pr and Sm co-doped CeO2-based systems

- Rapid Synthesis of Metallic Reinforced in Situ Intermetallic Composites in Ti-Al-Nb System via Resistive Sintering

- Oxidation Behavior of NiCr/YSZ Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs)

- Clustering Analysis of Normal Strength Concretes Produced with Different Aggregate Types

- Magnetic Nano-Sized Solid Acid Catalyst Bearing Sulfonic Acid Groups for Biodiesel Synthesis

- The biological activities of Arabis alpina L. subsp. brevifolia (DC.) Cullen against food pathogens

- Humidity properties of Schiff base polymers

- Free Vibration Analysis of Fiber Metal Laminated Straight Beam

- Comparative study of in vitro antioxidant, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase activity of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) collected during different growth stages

- Isothermal Oxidation Behavior of Gadolinium Zirconate (Gd2Zr2O7) Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs) produced by Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition (EB-PVD) technique

- Optimization of Adsorption Parameters for Ultra-Fine Calcite Using a Box-Behnken Experimental Design

- The Microstructural Investigation of Vermiculite-Infiltrated Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition Thermal Barrier Coatings

- Modelling Porosity Permeability of Ceramic Tiles using Fuzzy Taguchi Method

- Experimental and theoretical study of a novel naphthoquinone Schiff base

- Physicochemical properties of heat treated sille stone for ceramic industry

- Sand Dune Characterization for Preparing Metallurgical Grade Silicon

- Catalytic Applications of Large Pore Sulfonic Acid-Functionalized SBA-15 Mesoporous Silica for Esterification

- One-photon Absorption Characterizations, Dipole Polarizabilities and Second Hyperpolarizabilities of Chlorophyll a and Crocin

- The Optical and Crystallite Characterization of Bilayer TiO2 Films Coated on Different ITO layers

- Topical Issue on Bond Activation

- Metal-mediated reactions towards the synthesis of a novel deaminolysed bisurea, dicarbamolyamine

- The structure of ortho-(trifluoromethyl)phenol in comparison to its homologues – A combined experimental and theoretical study

- Heterogeneous catalysis with encapsulated haem and other synthetic porphyrins: Harnessing the power of porphyrins for oxidation reactions

- Recent Advances on Mechanistic Studies on C–H Activation Catalyzed by Base Metals

- Reactions of the organoplatinum complex [Pt(cod) (neoSi)Cl] (neoSi = trimethylsilylmethyl) with the non-coordinating anions SbF6– and BPh4–

- Erratum

- Investigation on Two Compounds of O, O’-dithiophosphate Derivatives as Corrosion Inhibitors for Q235 Steel in Hydrochloric Acid Solution

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- The effect of CuO modification for a TiO2 nanotube confined CeO2 catalyst on the catalytic combustion of butane

- The preparation and antibacterial activity of cellulose/ZnO composite: a review

- Linde Type A and nano magnetite/NaA zeolites: cytotoxicity and doxorubicin loading efficiency

- Performance and thermal decomposition analysis of foaming agent NPL-10 for use in heavy oil recovery by steam injection

- Spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, UV, 1H and 13C NMR) insights, electronic profiling and DFT computations on ({(E)-[3-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-1-phenylpropylidene] amino}oxy)(4-nitrophenyl)methanone, an imidazole-bearing anti-Candida agent

- A Simplistic Preliminary Assessment of Ginstling-Brounstein Model for Solid Spherical Particles in the Context of a Diffusion-Controlled Synthesis

- M-Polynomials And Topological Indices Of Zigzag And Rhombic Benzenoid Systems

- Photochemical Transformation of some 3-benzyloxy-2-(benzo[b]thiophen-2-yl)-4Hchromen-4-ones: A Remote Substituent Effect

- Dynamic Changes of Secondary Metabolites and Antioxidant Activity of Ligustrum lucidum During Fruit Growth

- Studies on the flammability of polypropylene/ammonium polyphosphate and montmorillonite by using the cone calorimeter test

- DSC, FT-IR, NIR, NIR-PCA and NIR-ANOVA for determination of chemical stability of diuretic drugs: impact of excipients

- Antioxidant and Hepatoprotective Effects of Methanolic Extracts of Zilla spinosa and Hammada elegans Against Carbon Tetrachlorideinduced Hepatotoxicity in Rats

- Prunus cerasifera Ehrh. fabricated ZnO nano falcates and its photocatalytic and dose dependent in vitro bio-activity

- Organic biocides hosted in layered double hydroxides: enhancing antimicrobial activity

- Experimental study on the regulation of the cholinergic pathway in renal macrophages by microRNA-132 to alleviate inflammatory response

- Synthesis, characterization, in-vitro antimicrobial properties, molecular docking and DFT studies of 3-{(E)-[(4,6-dimethylpyrimidin-2-yl)imino]methyl} naphthalen-2-ol and Heteroleptic Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Zn(II) complexes

- M-Polynomials and Topological Indices of Dominating David Derived Networks

- Human Health Risk Assessment of Trace Metals in Surface Water Due to Leachate from the Municipal Dumpsite by Pollution Index: A Case Study from Ndawuse River, Abuja, Nigeria

- Analysis of Bowel Diseases from Blood Serum by Autofluorescence and Atomic Force Microscopy Techniques

- Hydrographic parameters and distribution of dissolved Cu, Ni, Zn and nutrients near Jeddah desalination plant

- Relationships between diatoms and environmental variables in industrial water biotopes of Trzuskawica S.A. (Poland)

- Optimum Conversion of Major Ginsenoside Rb1 to Minor Ginsenoside Rg3(S) by Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Acid Hydrolysis Treatment

- Antioxidant, Anti-microbial Properties and Chemical Composition of Cumin Essential Oils Extracted by Three Methods

- Regulatory mechanism of ulinastatin on autophagy of macrophages and renal tubular epithelial cells

- Investigation of the sustained-release mechanism of hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose skeleton type Acipimox tablets

- Bio-accumulation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Grey Mangrove (Avicennia marina) along Arabian Gulf, Saudi Coast

- Dynamic Change of Secondary Metabolites and spectrum-effect relationship of Malus halliana Koehne flowers during blooming

- Lipids constituents from Gardenia aqualla Stapf & Hutch

- Effect of using microwaves for catalysts preparation on the catalytic acetalization of glycerol with furfural to obtain fuel additives

- Effect of Humic Acid on the Degradation of Methylene Blue by Peroxymonosulfate

- Serum containing drugs of Gua Lou Xie Bai decoction (GLXB-D) can inhibit TGF-β1-Induced Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in A549 Cells

- Antiulcer Activity of Different Extracts of Anvillea garcinii and Isolation of Two New Secondary Metabolites

- Analysis of Metabolites in Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz Dry Red Wines from Shanxi by 1H NMR Spectroscopy Combined with Pattern Recognition Analysis

- Can water temperature impact litter decomposition under pollution of copper and zinc mixture

- Released from ZrO2/SiO2 coating resveratrol inhibits senescence and oxidative stress of human adipose-derived stem cells (ASC)

- Validated thin-layer chromatographic method for alternative and simultaneous determination of two anti-gout agents in their fixed dose combinations

- Fast removal of pollutants from vehicle emissions during cold-start stage

- Review Article

- Catalytic activities of heterogeneous catalysts obtained by copolymerization of metal-containing 2-(acetoacetoxy)ethyl methacrylate

- Antibiotic Residue in the Aquatic Environment: Status in Africa

- Regular Articles

- Mercury fractionation in gypsum using temperature desorption and mass spectrometric detection

- Phytosynthetic Ag doped ZnO nanoparticles: Semiconducting green remediators

- Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Induced by SMAD4 Activation in Invasive Growth Hormone-Secreting Adenomas

- Physicochemical properties of stabilized sewage sludge admixtures by modified steel slag

- In Vitro Cytotoxic and Antiproliferative Activity of Cydonia oblonga flower petals, leaf and fruit pellet ethanolic extracts. Docking simulation of the active flavonoids on anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2

- Synthesis and Characterization of Pd exchanged MMT Clay for Mizoroki-Heck Reaction

- A new selective, and sensitive method for the determination of lixivaptan, a vasopressin 2 (V2)-receptor antagonist, in mouse plasma and its application in a pharmacokinetic study

- Anti-EGFL7 antibodies inhibit rat prolactinoma MMQ cells proliferation and PRL secretion

- Density functional theory calculations, vibration spectral analysis and molecular docking of the antimicrobial agent 6-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-ylmethyl)-5-ethyl-2-{[2-(morpholin-4-yl)ethyl] sulfanyl}pyrimidin-4(3H)-one

- Effect of Nano Zeolite on the Transformation of Cadmium Speciation and Its Uptake by Tobacco in Cadmium-contaminated Soil

- Effects and Mechanisms of Jinniu Capsule on Methamphetamine-Induced Conditioned Place Preference in Rats

- Calculating the Degree-based Topological Indices of Dendrimers

- Efficient optimization and mineralization of UV absorbers: A comparative investigation with Fenton and UV/H2O2

- Metabolites of Tryptophane and Phenylalanine as Markers of Small Bowel Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

- Adsorption and determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water through the aggregation of graphene oxide

- The role of NR2C2 in the prolactinomas

- Chromium removal from industrial wastewater using Phyllostachys pubescens biomass loaded Cu-S nanospheres

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Preparation of Calcium Fluoride using Phosphogypsum by Orthogonal Experiment

- The mechanism of antibacterial activity of corylifolinin against three clinical bacteria from Psoralen corylifolia L

- 2-formyl-3,6-bis(hydroxymethyl)phenyl benzoate in Electrochemical Dry Cell

- Electro-photocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin using calcium titanate

- Effect of Malus halliana Koehne Polysaccharides on Functional Constipation

- Structural Properties and Nonlinear Optical Responses of Halogenated Compounds: A DFT Investigation on Molecular Modelling

- DMFDMA catalyzed synthesis of 2-((Dimethylamino)methylene)-3,4-dihydro-9-arylacridin-1(2H)-ones and their derivatives: in-vitro antifungal, antibacterial and antioxidant evaluations

- Production of Methanol as a Fuel Energy from CO2 Present in Polluted Seawater - A Photocatalytic Outlook

- Study of different extraction methods on finger print and fatty acid of raw beef fat using fourier transform infrared and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- Determination of trace fluoroquinolones in water solutions and in medicinal preparations by conventional and synchronous fluorescence spectrometry

- Extraction and determination of flavonoids in Carthamus tinctorius

- Therapeutic Application of Zinc and Vanadium Complexes against Diabetes Mellitus a Coronary Disease: A review

- Study of calcined eggshell as potential catalyst for biodiesel formation using used cooking oil

- Manganese oxalates - structure-based Insights

- Topological Indices of H-Naphtalenic Nanosheet

- Long-Term Dissolution of Glass Fibers in Water Described by Dissolving Cylinder Zero-Order Kinetic Model: Mass Loss and Radius Reduction

- Topological study of the para-line graphs of certain pentacene via topological indices

- A brief insight into the prediction of water vapor transmissibility in highly impermeable hybrid nanocomposites based on bromobutyl/epichlorohydrin rubber blends

- Comparative sulfite assay by voltammetry using Pt electrodes, photometry and titrimetry: Application to cider, vinegar and sugar analysis

- MicroRNA delivery mediated by PEGylated polyethylenimine for prostate cancer therapy

- Reversible Fluorescent Turn-on Sensors for Fe3+ based on a Receptor Composed of Tri-oxygen Atoms of Amide Groups in Water

- Sonocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in aqueous solution using Fe-doped TiO2 nanoparticles under mechanical agitation

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Production and Analysis of Recycled Ammonium Perrhenate from CMSX-4 superalloys

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- New phosphorus biofertilizers from renewable raw materials in the aspect of cadmium and lead contents in soil and plants

- Survey of content of cadmium, calcium, chromium, copper, iron, lead, magnesium, manganese, mercury, sodium and zinc in chamomile and green tea leaves by electrothermal or flame atomizer atomic absorption spectrometry

- Biogas digestate – benefits and risks for soil fertility and crop quality – an evaluation of grain maize response

- A numerical analysis of heat transfer in a cross-current heat exchanger with controlled and newly designed air flows

- Freshwater green macroalgae as a biosorbent of Cr(III) ions

- The main influencing factors of soil mechanical characteristics of the gravity erosion environment in the dry-hot valley of Jinsha river

- Free amino acids in Viola tricolor in relation to different habitat conditions

- The influence of filler amount on selected properties of new experimental resin dental composite

- Effect of poultry wastewater irrigation on nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon contents in farmland soil

- Response of spring wheat to NPK and S fertilization. The content and uptake of macronutrients and the value of ionic ratios

- The Effect of Macroalgal Extracts and Near Infrared Radiation on Germination of Soybean Seedlings: Preliminary Research Results

- Content of Zn, Cd and Pb in purple moor-grass in soils heavily contaminated with heavy metals around a zinc and lead ore tailing landfill

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Synthesis of (±)-3,4-dimethoxybenzyl-4-methyloctanoate as a novel internal standard for capsinoid determination by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS(QTOF)

- Repellent activity of monoterpenoid esters with neurotransmitter amino acids against yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti

- Effect of Flammulina velutipes (golden needle mushroom, eno-kitake) polysaccharides on constipation

- Bioassay-directed fractionation of a blood coagulation factor Xa inhibitor, betulinic acid from Lycopus lucidus

- Antifungal and repellent activities of the essential oils from three aromatic herbs from western Himalaya

- Chemical composition and microbiological evaluation of essential oil from Hyssopus officinalis L. with white and pink flowers

- Bioassay-guided isolation and identification of Aedes aegypti larvicidal and biting deterrent compounds from Veratrum lobelianum

- α-Terpineol, a natural monoterpene: A review of its biological properties

- Utility of essential oils for development of host-based lures for Xyleborus glabratus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae), vector of laurel wilt

- Phenolic composition and antioxidant potential of different organs of Kazakh Crataegus almaatensis Pojark: A comparison with the European Crataegus oxyacantha L. flowers

- Isolation of eudesmane type sesquiterpene ketone from Prangos heyniae H.Duman & M.F.Watson essential oil and mosquitocidal activity of the essential oils

- Comparative analysis of the polyphenols profiles and the antioxidant and cytotoxicity properties of various blue honeysuckle varieties

- Special Issue on ICCESEN 2017

- Modelling world energy security data from multinomial distribution by generalized linear model under different cumulative link functions

- Pine Cone and Boron Compounds Effect as Reinforcement on Mechanical and Flammability Properties of Polyester Composites

- Artificial Neural Network Modelling for Prediction of SNR Effected by Probe Properties on Ultrasonic Inspection of Austenitic Stainless Steel Weldments

- Calculation and 3D analyses of ERR in the band crack front contained in a rectangular plate made of multilayered material

- Improvement of fuel properties of biodiesel with bioadditive ethyl levulinate

- Properties of AlSi9Cu3 metal matrix micro and nano composites produced via stir casting

- Investigation of Antibacterial Properties of Ag Doped TiO2 Nanofibers Prepared by Electrospinning Process

- Modeling of Total Phenolic contents in Various Tea samples by Experimental Design Methods

- Nickel doping effect on the structural and optical properties of indium sulfide thin films by SILAR

- The effect mechanism of Ginnalin A as a homeopathic agent on various cancer cell lines

- Excitation functions of proton induced reactions of some radioisotopes used in medicine

- Oxide ionic conductivity and microstructures of Pr and Sm co-doped CeO2-based systems

- Rapid Synthesis of Metallic Reinforced in Situ Intermetallic Composites in Ti-Al-Nb System via Resistive Sintering

- Oxidation Behavior of NiCr/YSZ Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs)

- Clustering Analysis of Normal Strength Concretes Produced with Different Aggregate Types

- Magnetic Nano-Sized Solid Acid Catalyst Bearing Sulfonic Acid Groups for Biodiesel Synthesis

- The biological activities of Arabis alpina L. subsp. brevifolia (DC.) Cullen against food pathogens

- Humidity properties of Schiff base polymers

- Free Vibration Analysis of Fiber Metal Laminated Straight Beam

- Comparative study of in vitro antioxidant, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase activity of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) collected during different growth stages

- Isothermal Oxidation Behavior of Gadolinium Zirconate (Gd2Zr2O7) Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs) produced by Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition (EB-PVD) technique

- Optimization of Adsorption Parameters for Ultra-Fine Calcite Using a Box-Behnken Experimental Design

- The Microstructural Investigation of Vermiculite-Infiltrated Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition Thermal Barrier Coatings

- Modelling Porosity Permeability of Ceramic Tiles using Fuzzy Taguchi Method

- Experimental and theoretical study of a novel naphthoquinone Schiff base

- Physicochemical properties of heat treated sille stone for ceramic industry

- Sand Dune Characterization for Preparing Metallurgical Grade Silicon

- Catalytic Applications of Large Pore Sulfonic Acid-Functionalized SBA-15 Mesoporous Silica for Esterification

- One-photon Absorption Characterizations, Dipole Polarizabilities and Second Hyperpolarizabilities of Chlorophyll a and Crocin

- The Optical and Crystallite Characterization of Bilayer TiO2 Films Coated on Different ITO layers

- Topical Issue on Bond Activation

- Metal-mediated reactions towards the synthesis of a novel deaminolysed bisurea, dicarbamolyamine

- The structure of ortho-(trifluoromethyl)phenol in comparison to its homologues – A combined experimental and theoretical study

- Heterogeneous catalysis with encapsulated haem and other synthetic porphyrins: Harnessing the power of porphyrins for oxidation reactions

- Recent Advances on Mechanistic Studies on C–H Activation Catalyzed by Base Metals

- Reactions of the organoplatinum complex [Pt(cod) (neoSi)Cl] (neoSi = trimethylsilylmethyl) with the non-coordinating anions SbF6– and BPh4–

- Erratum

- Investigation on Two Compounds of O, O’-dithiophosphate Derivatives as Corrosion Inhibitors for Q235 Steel in Hydrochloric Acid Solution