Abstract

Samples of layered double hydroxides containing carbonates as compensating anions were prepared by the urea method. These LDHs were used as hosts of anions coming from pipemidic and nalidixic acid. XRD results confirm that these anions were hosted in the interlayer space of LDHs. Further, from 27Al NMR MAS characterization of an interaction between the brucite-like layers and anions was suggested. Then the hybrids LDHs were used as biocide of Salmonella typhi and Escherichia coli. The release profile of pipemidic and nalidixic anions from hybrid LDHs occurs for periods as long as 3.5 hours. The free-organic acid LDHs were not able to kill S. Typhi, neither E. coli. In contrast, the hybrids LDHs eliminate almost completely bacteria within short times.

1 Introduction

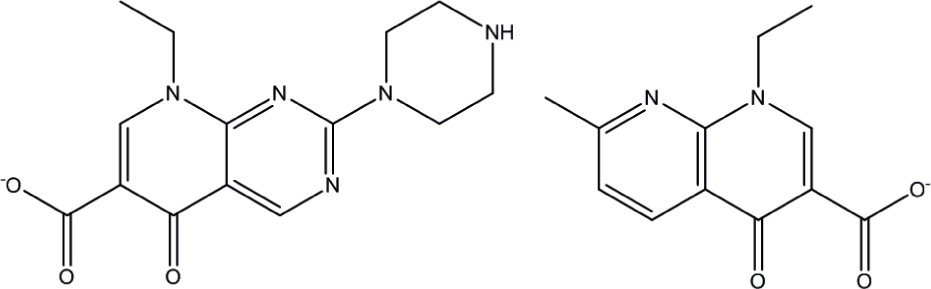

In human society the control mechanisms to inhibit the bacteria proliferation are often not efficient, conversely microbial infections are one of the main killers in the world [1]. The treatment of microbial infections becomes more and more complex because of the number of resistant microbial strains plus that antibiotic immune patients grow significantly faster than the number of useable antibiotics [2,3]. Thus, antimicrobial agents are required to control pathogen growth. Efficiency of antimicrobial materials is determined by several physicochemical factors [4,5,6]. Most commonly bactericides are metal [7,8] for instance copper, gold and silver are well known to be efficient when they are sized at nanoscale [9,10]. Other biocides, however, are toxic, which makes them undesirable for applications in sensitive media such as drinking water, foods or textiles. A lot of organic molecules also have potential to be applied to the control bacterial growth [11,12] but sometimes their use is restricted because they are easily dissolved and they could react before they reach the cell membrane. A way to potentiate the biocide effect of organic molecules is to incorporate them into an inorganic material in order to assure they reach the bacteria. This approach has been applied successfully for other organic molecules with a biological function such as antioxidants [13], glucose sensor [14] and enzymatic processes [15], among others. Taking into account these examples, a good hybrid material with biocide properties could emerge from the combination of nalidixic or pipemidic acids (chemical structure of anions of these two acids is shown in figure 1) as the organic biocide and the layered double hydroxides as inorganic shields.

Chemical structures of anions of pipemidic acid (left) and nalidixic acid (right).

Nalidixic acid acts, at low concentration, is a bacteriostatic agent, which means that it inhibits bacterial growth but at high concentration it becomes a bactericide, in other words, it is able to kill bacteria [16]. Pipemidic acid is also a biocide agent that acts mainly against the gram-negative bacteria [17].

Layered double hydroxides (LDHs), often known as hydrotalcite-type compounds can be described by the formula [MII1-xMIIIx(OH)2]x+(An-x/n)⋅mH2O. MII and MIII are divalent and trivalent cations which are bonded to six OH groups to form octaedra [M(OH)6] which in turn are sharing edges to build brucite-like layers. In layers of LDHs a partial substitution of the divalent cations by trivalent ones occurs and consequently a positive charge is induced in the layer; compensation of this positive charge is made by anions located between the brucite-like layers, these anions are solvated with water molecules [18] in the interlayer space. The chemical composition of LDHs drives their physicochemical properties, thus a great collection of LDHs has been synthesized, varying mainly the nature of trivalent and divalent cations but also diversifying the anions. Commonly, simple inorganic anions such as carbonate, phosphate, halides, or nitrate are the compensating anions in LDHs [19] but organic anions can also be found in LDHs. Synthesis of LDHs containing three or more cations in the layers [20] is also possible.

A unique characteristic of these layered materials is the called memory effect which is their ability to rebuild their layered structure, lost on heating at a moderate temperature (400-500°C), when exposed to water and anion containing solutions [21].

LDHs have found applications, mainly as base catalysts for many organic reactions and in minor amounts as vectors to guide organic and biologic molecules [22,23]. Thus, taking advantage of LDH properties and pipemidic and nalidixic acids, we started this work with the goal to prepare efficient hybrid biocide materials against E. coli and S. typhi.

2 Experimental procedure

2.1 Synthesis

LDHs were synthesized by the urea hydrolysis method [24]. As source of Zn and Al the salts Zn(NO3)2•6H2O and Al(NO3)3•9H2O were used, respectively. The synthesized LDH was dried at 120°C for 12 h. This dried solid was labelled LDH-CO3.

LDHs containing organic biocide were obtained from the carbonated one. 0.5 g of LDH-CO3 was thermally treated at 400°C for 5 h under N2 flux. The thermal-treated LDH was suspended in 30 mL of a solution containing sodium salts coming from pipemidic or nalidixic acid and then pH was adjusted to 9 by adding NaOH 0.1 M. The suspension was shaken for 7 days and after that the solid was recovered, washed and dried at 50°C. LDHs containing biocide were labelled LDH-CO3-PIP and LDH-CO3-NAD for solids with pipemidic or nalidixic acid, respectively. Chemical composition of LDH samples is reported in Table 1.

Chemical composition of hybrid LDH samples.

| Code Sample | Chemical formula | Zn/Al ratio |

|---|---|---|

| ZnAl-CO3 | [Zn0661Al0.214(OH)2(CO3)0.1070.89H2O | 3 |

| ZnAl-CO3-PIP | [Zn0.731Al0.240(OH)2](CO3)0.025(PIP)0.1920.81H2O | 3 |

| ZnAl-CO3-NAD | [Zn0.677Al0.220(OH)2](CO3)0.030(NAD)0.1580.77H2O | 3 |

2.2 Characterization

The layered double hydroxides were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD), solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance, infrared spectroscopy (FTIR-ATR) and N2 adsorption.

The XRD patterns were acquired using a diffractometer D8 Advance-Bruker equipped with a copper anode X-ray tube. The crystalline phases were identified by fitting the diffraction patterns with the corresponding Joint Committee Powder Diffraction Standards (JCPDS cards).

Infrared spectra were recorded in the ATR-FTIR mode using a Perkin-Elmer series spectrophotometer model 6X.

Solid state nuclear magnetic resonance (MAS NMR) measurements were performed in an Avance-400 Bruker (9.39 T) spectrometer. Chemical shifts were referenced to TMS. Solid-state 27Al and 13C magic angle spinning-nuclear magnetic resonance (MAS-NMR) experiments were performed on a Bruker Avance II spectrometer at frequencies of 104.2 and 100.58 MHz, respectively. 13C CP MAS-NMR spectra were acquired using a 4-mm cross-polarisation (CP) MAS probe spinning at a rate of 5 kHz. Typical 13C CP MAS-NMR conditions for the 1H-13C polarization experiment, included a π/2 pulse of 4 μs, contact time of 1 ms and delay time of 5 s. Chemical shifts were referenced to TMS. 27Al MAS-NMR spectra were acquired using short single pulses (π/12) and a delay time of 0.5 s. The samples were spun at 10 kHz, and the chemical shifts were referenced to an aqueous 1 M AlCl3 solution.

2.3 Bacteria experiments

Bacteria were acquired from Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas del Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Mexico. E. coli and S. thyphi strain (ATCC 25922) were grown in tripticaseine broth. For the growth experiments, a starter culture of each strain was inoculated with fresh colonies and incubated for 24 h in Tripticaseine medium. Bacterial growth rates were determined by counting the number of surviving colonies in a selective agar. Fresh medium (10 mL) was inoculated in test tubes with the starter culture and grown at 37°C with continuous agitation at 30 rpm. 2.5 mg of free biocide and the amount required of LDH-biocide to have a similar amount of organic biocide were then added to the culture, and the colonies were measured over a time course. The LDHs were recovered, dried and then used in a second experiment with bacteria. As reference, the bacterial growth rates were also performed in the presence of free biocides. During all experiments treated with bacteria the material used was sterilized and LDH was used immediately after preparation. Experiments were done in triplicate in order to have statistical significance. Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animals use.

3 Results

3.1 Materials

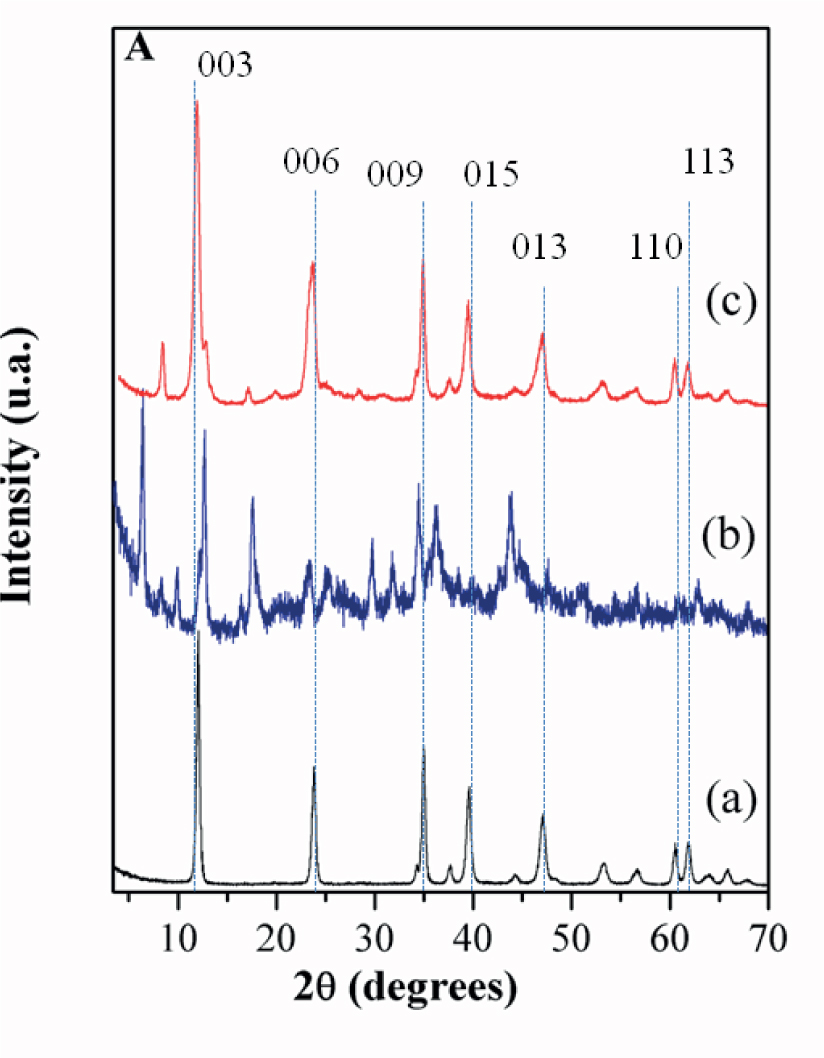

In Figure 2 are compared the XRD patterns of LDHs without or loaded with biocide organic molecules. XRD patterns of samples free of biocide exhibit a peak with Miller index (003) at 11.57 degrees corresponding to an interlayer distance (d003) of 7.64 Å. XRD patterns shows evidence that incorporation of pipemidic acid in LDH-CO3 leads to a loss of crystallinity. In the diffractogram of the LDH-CO3-PIP the presence of a peak at low values of two-theta, close to 6.3 degrees, proves that distance between the layers increased. However, the peak with a d003 of 7.64 Å is also observed in LDH-CO3-PIP. The XRD pattern of LDH-CO3-NAD corresponds to LDH more crystalline than that observed for LDH-CO3-PIP. In XRD pattern of LDH-CO3-NAD the peak labelled (003) is also shifted to lower values if compared to LDH-CO3 suggesting an intercalation of nalidixic anions between the brucite-like layers. XRD pattern of LDH-CO3-NAD exhibits three peaks at 8.43°, 17.13° and 25.12° (2θ) which is indicative of larger distances between brucite-like layers. The peak at 8.43 degrees corresponds to a distance d003 of 10.48 Å. On the other hand, the peaks at 17.13° and 25.12° match with harmonics indexed (006) and (009), respectively.

X-ray diffraction patterns of LDH-CO3: (a) free of organic biocide, (b) containing pipemidic acid, and (c) containing nalidixic acid. As a reference, the lines with Miller index of hydrotalcite phase are included.

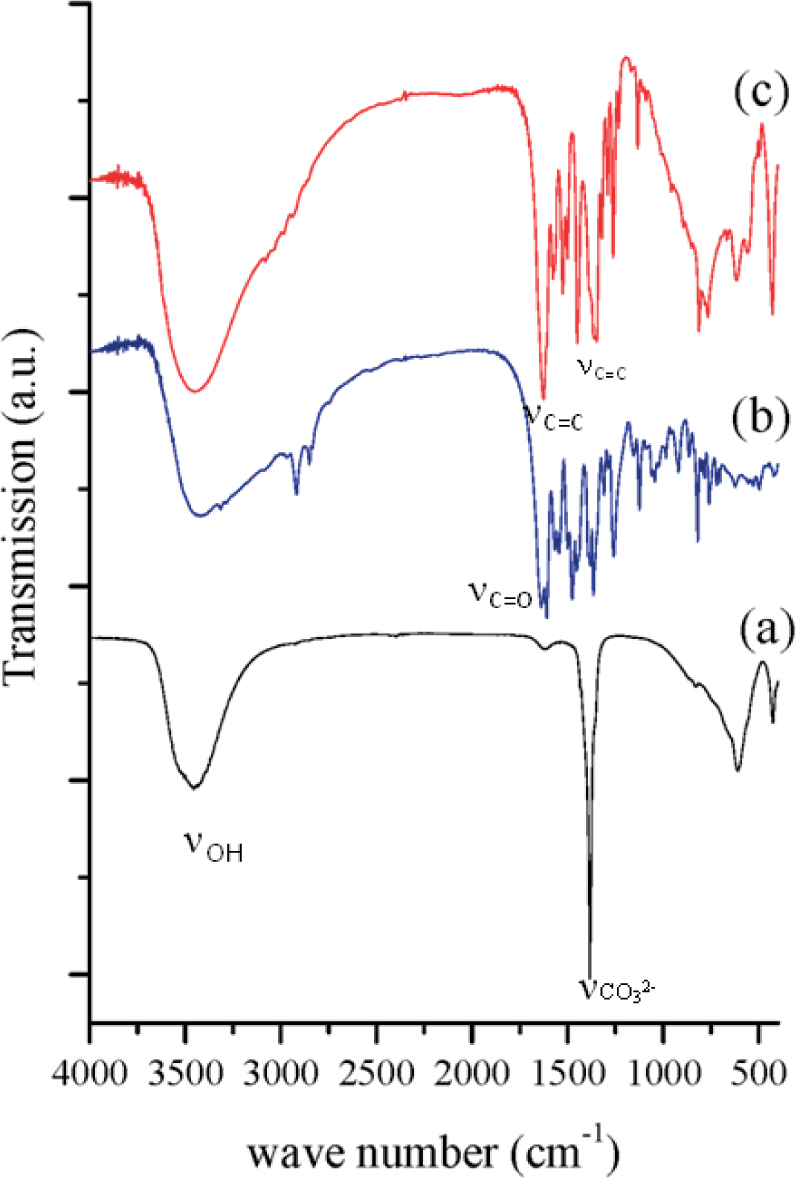

FTIR spectra of LDH-CO3 and biocide-LDHs are displayed in Figure 3. The spectrum of free biocide LDH sample presents the broad band centered at 3445 cm-1, which is assigned to stretching (ν) of O-H bonds. The band due to the bending (δ) vibration of water molecules is found close to 1620 cm-1 for both samples. The band assigned to stretching C-O bonds coming from CO32- species appears very intense at 1363 cm-1. Lastly, a broad and asymmetric band observed is observed at wave number below 1000 cm-1, which is assigned to vibration of metal-oxygen bonds present in brucite-like layers.

FTIR spectra of LDH-CO3: (a) free of organic biocide, (b) containing pipemidic acid, and (c) containing nalidixic acid.

In the spectrum of LDH-CO3-PIP the absorption bands due to main functional groups of pipemidic acid are observed. The band at 1635 cm-1 in the spectrum of LDH-CO3-PIP is assigned to νsym of carboxilate group [25,26,27]. The band at 1550 cm-1 is due to the stretching mode of C=O [28].

The spectrum of LDH-CO3-NAD also shows evidence of the presence of nalidixic acid anions in LDH. In the spectrum of LDH-CO3-NAD, the absorption band at 1463 cm-1 corresponds to νsym C=C of the aromatic rings, the band at 1496 cm-1 is due to v of C=N. Lastly, the bands at 1536 and 1347 cm-1 are assigned to νasym and νsym of COO-, respectively.

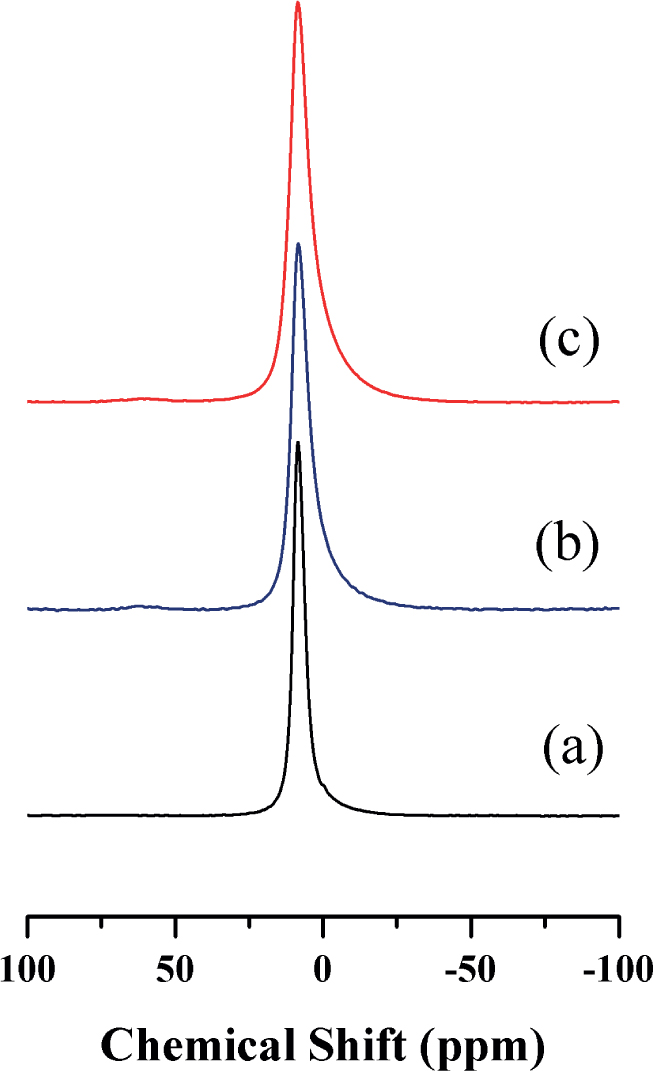

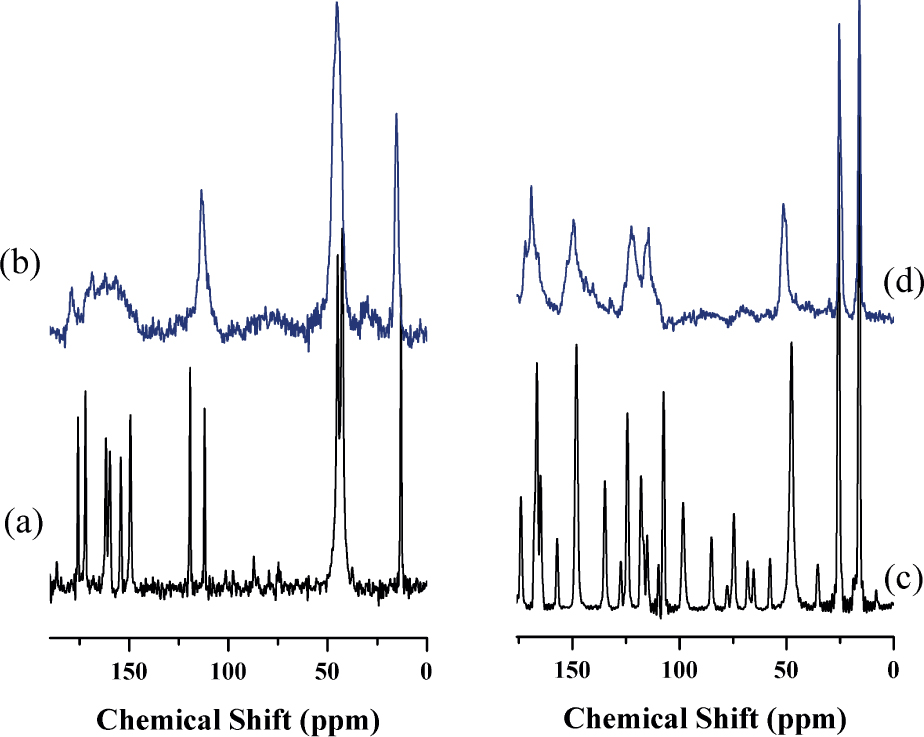

27Al MAS NMR spectra displayed in Figure 4 show that coordination number of aluminium does not change with the biocide loading. In the spectrum of LDH-CO3 only an isotropic peak close to 8 ppm is observed, which is due to aluminium six-fold coordinated to oxygen atoms [29]. When the LDH is loaded with biocide the peak becomes broader. 13C CP-MAS NMR spectra, Figure 5, are in line with the 27Al NMR results. The NMR signal of aliphatic carbons for both nalidixic and pipemidic acid are found in the range of 20-80 ppm and that of aromatic carbons within 90-175 ppm [30]. The spectra of pure sodium salts (spectra a and d) are composed of narrow well-defined peaks. In contrast, when organic molecules are incorporated to LDH, signals become broader, particularly those due to aromatic carbons.

27Al MAS NMR spectra of LDH-CO3: (a) free of organic biocide, (b) containing pipemidic acid, and (c) containing nalidixic acid.

13C CP MAS NMR Spectra of (a) sodium pipemidic salt, (b) LDH-CO3-PIP, (c) sodium nalidixic salt and (d) LDH-CO3-NAD.

3.2 Biocide activity

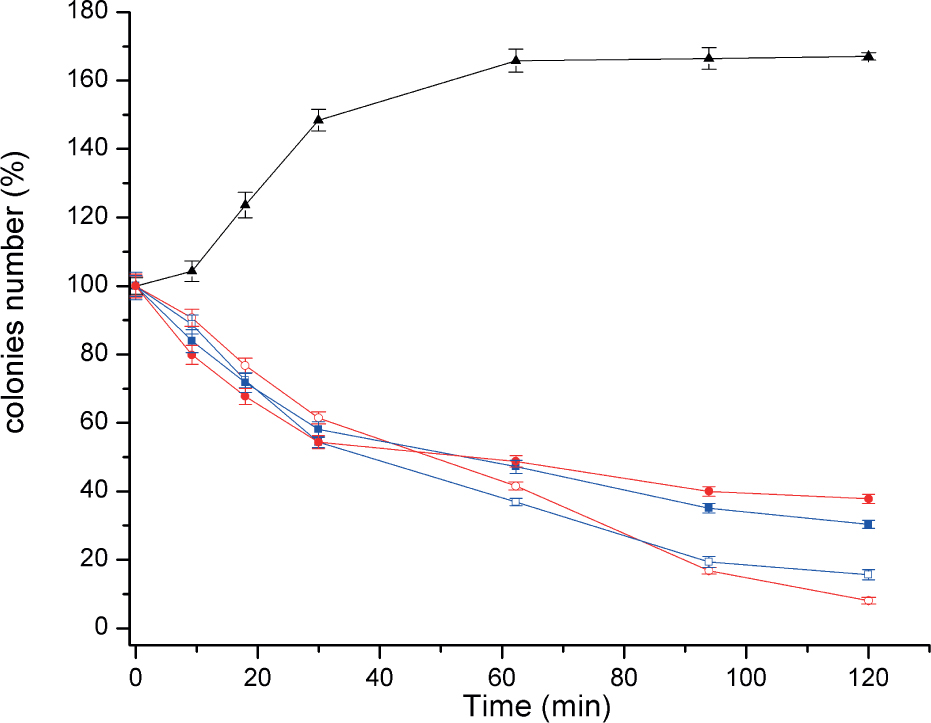

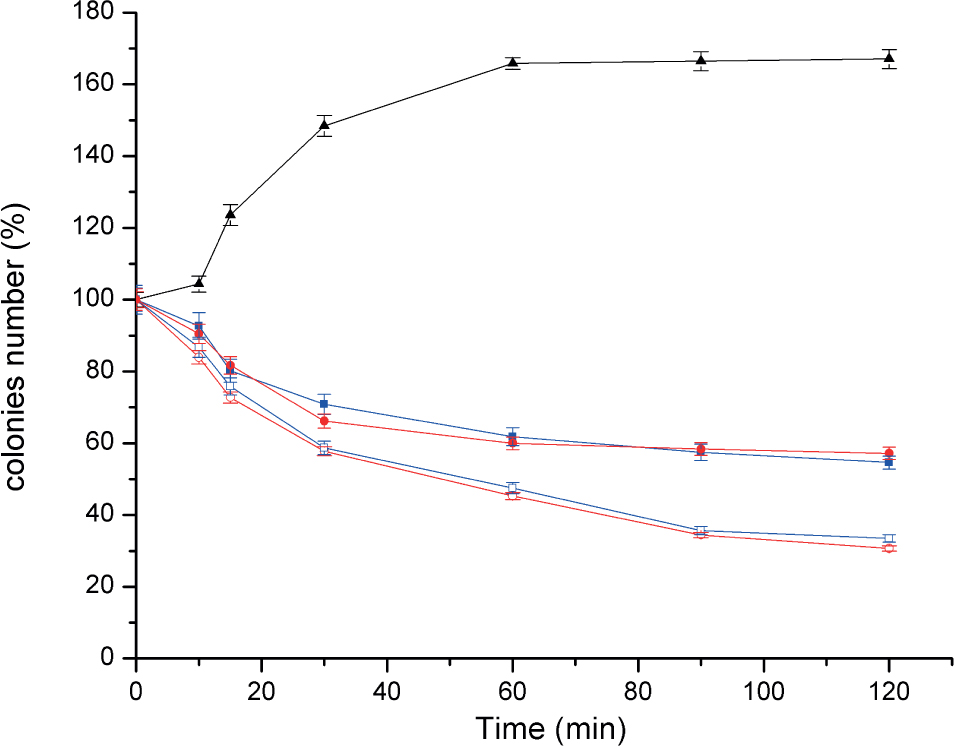

Figure 6 compares the curves of the number of E. coli colonies survived as time went on in the culture media and in the presence of ZnAl-CO3-biocide materials. As reference samples, the free biocide and LDH without organic biocide were also tested. In the presence of ZnAl-CO3 the number of colonies increases always and after 90 minutes the number of colonies was increased by 70%. When the biocides are dissolved in culture media, as free biocide, they are efficient in killing 40% of the colonies for times as short as 30 min but after that the killing rate decreases significantly, and for the period from 30 to 120 min only 20% and 27% of the bacteria are abated by pipemidic and nalidixic acid, respectively.

Evolution as a function of time of number of E coli colonies survived in culture media in the presence of PIP (-●-), NAD (-■-), ZnAl-CO3 (-▲-), ZnAl-CO3-NAD (-□-), ZnAl-CO3-PIP (-○-).

The biocides intercalated in LDHs behave similar to free biocides in the first short period of 30 minutes, killing 46% of colonies. However, contrary to free biocides, both NAD and PIP intercalated in LDH continue to kill a high percentage of colonies at times longer than 30 minutes. Indeed, both biocide-LDH practically kill 85% of colonies in 95 minutes.

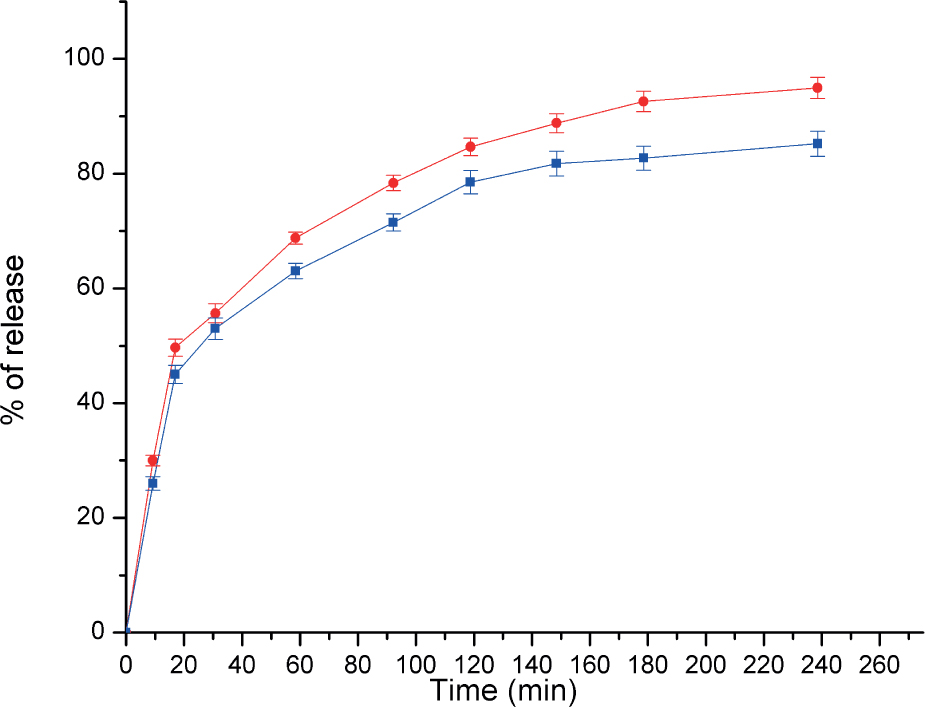

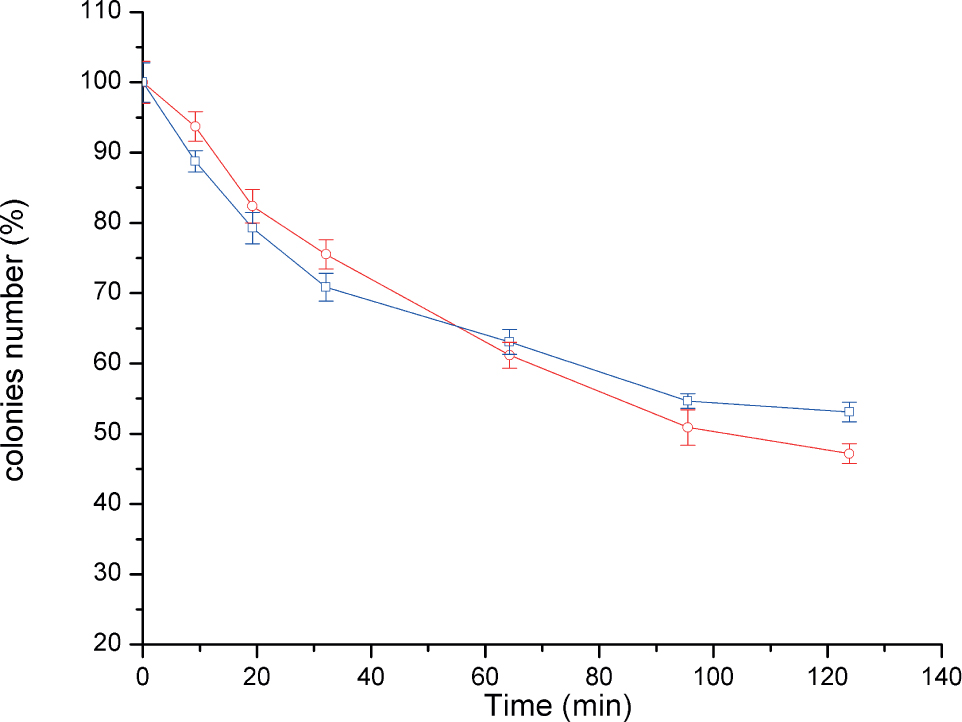

The release profiles of PIP and NAD from ZnAl-CO3-biocide in 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.5 are shown in Figure 7. The release profiles of NAD and PIP are very close in the first two hours, releasing close to 80% of biocide. For times longer than 2 hours the profile of LDH-CO3-NAD is lower than that of LDH-CO3-PIP but both materials release biocide after 2 h and at periods as long as 4 h almost the total biocide was leached from LDH-CO3-PIP. In other words, after 3.5 hours the hybrid LDHs still contain either PIP or NAD, which can be useful to kill bacteria in a second experiment. Coming back to experiments with bacteria, in a first experiment, the maximal percentage of killed bacteria was 86 and 93% in the case of LDH-CO3-NAD and LDH-CO3-PIP, respectively. The biocide-LDH was recovered after experiments reported in Figure 6 and reused as bactericide in a second experiment, and the results are shown in Figure 8. The reused material is still bactericidal but their power to kill bacteria is lower than fresh materials, which should be related to the low remaining biocide after the first cycle as bactericide.

Release profile of NAD from LDH-CO3-NAD (-■-) and PIP from LDH-CO3-PIP (-●-) in 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.5. The amount of NAD or PIP was monitored by UV-vis spectroscopy.

Evolution as a function of time of number of E coli colonies survived in culture media in the presence of reused LDH-biocide ZnAl-CO3-NAD (-□-) and ZnAl-CO3-PIP (-○-).

In Figure 9 is plotted the number of S typhi colonies survived as time went on in the culture media and in the presence of LDH-CO3, organic biocides as well as in the presence of ZnAl-CO3-biocide materials. In the presence of LDH-CO3, nobacteriostatic or bactericide effect was observed and the number of colonies increased rapidly with time, and after 2 hours the number of colonies was nearlyduplicated. Free biocides are bactericides in the first 30 minutes, killing only 30% of the colonies; for longer times the bactericide effect diminishes and after 2 hours 55% of the colonies survive.

Evolution as a function of time of number of S typhi colonies survived in culture media in the presence of PIP (-●-), NAD (-■-), ZnAl-CO3 (-▲-), ZnAl-CO3-NAD (-□-), ZnAl-CO3-PIP.

In the first 30 minutes, LDH-biocide materials behave similarly as bactericide of S. thypi to that observed for E. coli. After 30 minutes in the presence of ZnAl-CO3-biocide materials, the number of colonies had diminished to 42 % of initial bacteria. The most interesting results is that observed after 30 minutes, both ZnAl-CO3-NAD and ZnAl-CO3-PIP continue abating colonies to reach a 72% killing efficiency which is almost 30% more than free biocides.

4 Discussion

The XRD results provides evidence that pipemidic and nalidixic anions where intercalated in LDH-CO3 but with pipemidic acid the intercalation is accompanied with a loss of crystallinity suggesting that stacking of brucite-like layers is less ordered. In both cases, organic anions do not totally replace the carbonate anions. The FTIR and NMR results suggest an interaction between brucite-like layers and organics anions. Actually, when the LDHs are loaded with biocide, the 27Al MAS NMR peaks become broader suggesting that relaxation of the signal is affected most probably because of the presence of a large pi electron density coming from aromatic rings of the biocide.

The behaviour of the biocide-LDHs as antimicrobial agent against E. coli suggested that the system acts as a delivery vehicle of organic biocide and can be used for long periods. On the contrary, free biocide, without support, act as a bactericide at times as short as 30 minutes but after that it has only bacteriostatic properties.

The prolonged release of biocide from biocide-LDHs should be attributed to dipolar interactions between organic biocide and LDHs and occurs in other similar hybrid organic-LDHs composites [31,32]

Even though S. typhi is more resistant than E. coli to both acid nalidixic and pipemidic acids incorporated to LDHs, it is clear that the interactions of LDH-biocide are favourable to kill S. typhi. This could be related to the bactericidal mechanism of bacteria, which in general implies disruption of the cell wall by destabilising cations associated with the cell envelope. Thus, the orientation of biocide molecules through LDH interactions, and long period release could be an additional helpful agent in elimination of bacteria.

5 Conclusion

Pipemidic and nalidixic acid hosted in layered double hydroxides zinc-aluminium can be used as biocide materials of Escherichia coli and Salmonela typhi. Layered double hydroxides containing carbonates as compensating anions, without organic acids, are not able to kill bacteria. When biocides are incorporated to the LDHs, they become more efficient as bactericides, and are able to kill up to 90 and 70% of E. coli and S. typhi, respectively. In general, S. typhi shows more resistance to be killed by biocide materials.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge CONACYT for Grant 220436 and PAPIIT IN106517. We are grateful to G. Cedillo and A. Tejeda for their technical assistance.

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Nicolas P., Mor A., Peptides as Weapons against Microorganisms in the Chemical Defense System of Vertebrates, Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 1995, 49, 277-304.10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.001425Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Lode H. M., Clinical Impact of Antibiotic-Resistant Gram-Positive Pathogens, Clin. Microbiol. Infect., 2009, 15, 212-217.10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02738.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Gonzales F.P., Maisch T., XF Drugs: A New Family of Antibacterials, Drug News Perspect., 2010, 23, 167-174.10.1358/dnp.2010.23.3.1444225Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Chopra I., The increasing use of silver-based products as antimicrobial agents: a useful development or a cause for concern?, J. Antimicrob. Chemother., 2007, 59, 587–590.10.1093/jac/dkm006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Łukasiewicz A., Chmielewska D. K., Walis L., Rowinska L., New silica materials with biocidal active surface, Pol. J. Chem. Technol., 2003, 5, 20–22.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Wan Y., Zhang D., Wang Y., Qi P., Wu Y., Hou B., Vancomycin-functionalised Ag@TiO2 phototoxicity for bacteria, J .Hazard. Mater., 2011, 186, 306–312.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.10.110Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Lemire J. A, Harrison J.J., Turner R.J., Antimicrobial activity of metals: mechanisms, molecular targets and applications, Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2013, 11, 371–384.10.1038/nrmicro3028Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Nies D.H., Microbial heavy-metal resistance, Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1999, 51,730–750.10.1007/s002530051457Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Guerra R., Lima E., Viniegra M., Guzmán A., Lara V., Growth of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhi inhibited by fractal silver nanoparticles supported on zeolites, Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 2012, 147. 267–27310.1016/j.micromeso.2011.06.031Search in Google Scholar

[10] Guerra R., Lima E., Guzmán A., Antimicrobial supported nanoparticles: Gold versus silver for the cases of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typh, i Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 2013, 170, 62-66.10.1016/j.micromeso.2012.11.036Search in Google Scholar

[11] Gilbert P., Pemberton D., Wilkinson D.E., Barrier properties of the Gram-negative cell envelope towards high molecular weight polyhexamethylene biguanides, J. Appl. Microbiol., 1990, 69, 585-592.10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb01552.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Taber H.W., Mueller J.P., Miller P.F., Arrow A.S., Bacterial uptake of aminoglycoside antibiotics, Microbiological Reviews, 1987. 51, 439-457.10.1128/mr.51.4.439-457.1987Search in Google Scholar

[13] Lima E., Flores J., Santana Cruz A., Leyva-Gómez G., Krötzsch E., Controlled realease of ferulic acid from a hybrid hydrotalcite and its application as an antioxidant for human fibroblasts, Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 2013, 181, 1–7.10.1016/j.micromeso.2013.07.014Search in Google Scholar

[14] Koh A., Riccio D.A., Sun B., Carpenter B.W., Nichols S.P., Schoenfisch M.H., Fabrication of nitric oxide-releasing polyurethane glucose sensor membranes, Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 2011, 28, 17–24.10.1016/j.bios.2011.06.005Search in Google Scholar

[15] Ben-Knaz R., Avnir D., Bioactive Enzyme-Metal Composites: The Entrapment of Acid Phosphatase Within Gold and Silver, Biomaterials, 2009, 30, 1263 – 1267.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.11.026Search in Google Scholar

[16] Hooper D.C., Quinolones, in: Churchill Livingstone (Ed.), Princ. Pract. Infect. Dis., New York, 1995.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Mestre Y.F., Zamora L.L., Mart J., Spectrophotometric determination of nalidixic and pipemidic acids in a flow injection assembly with a solid-phase reactor as a highly stable reagent source, Analyt. Chim., 2001, 438, 93-102.10.1016/S0003-2670(01)00917-5Search in Google Scholar

[18] Miyata S., Physico-chemical properties of synthetic hydrotalcites in relation to composition Clays, Clay Minerals, 1980, 28, 50-56.10.1346/CCMN.1980.0280107Search in Google Scholar

[19] Cavani F., Trifiro F., Vaccari A., Hydrotalcite-type anionic clays: preparation, properties and applications, Catal. Today, 1991, 11, 173-301.10.1016/0920-5861(91)80068-KSearch in Google Scholar

[20] Valente J.S., Sánchez-Cantú M., Lima E., Figueras F., Method for Large-Scale Production of Multimetallic Layered Double Hydroxides: Formation Mechanism Discernment, Chem. Mater. 2009, 21, 5809–581810.1021/cm902377pSearch in Google Scholar

[21] Stanimirova T. S., Kirov g., Donolova E. J., Mechanism of hydrotalcite regeneration, Mater. Sci. Lett., 2001, 20, 453-455.10.1023/A:1010914900966Search in Google Scholar

[22] Polato C.M.S., Henriques C.A., Neto A.A., Monteiro J.L.F., Synthesis, characterization and evaluation of CeO2/Mg, Al-mixed oxides as catalysts for SOx removal, J. Mol. Catal. A, 2005, 241, 184-193.10.1016/j.molcata.2005.07.006Search in Google Scholar

[23] Choy J.H., Choi S.J., Oh J.M., Park T., Clay minerals and layered double hydroxides for novel biological applications, Appl. Clay Sci., 2007, 36, 122–132.10.1016/j.clay.2006.07.007Search in Google Scholar

[24] Costantino V., Pinnavaia T., Basic Properties of Mg2+1-xAl3+x Layered Double Hydroxides Intercalated by Carbonate, Hydroxide, Chloride, and Sulfate Anions, Inorg. Chem., 1995, 34, 883-892.10.1021/ic00108a020Search in Google Scholar

[25] Skrzypek D., Szymanska B., Kovala-Demertzi D., Wiecek J., Talik E., Demertzis M.A., Synthesis and spectroscopic studies of iron (III) complex with a quinolone family member (pipemidic acid), J. Phys. Chem. Solids, 2066, 67, 2550-2558.10.1016/j.jpcs.2006.07.013Search in Google Scholar

[26] Yang L., Tao D., Yang X., Li Y., Guo Y., Synthesis, Characterization, and Antibacterial Activities of Some Rare Earth Metal Complexes of Pipemidic Acid, Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 51, 494-498.10.1248/cpb.51.494Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Efthimiadou E.K., Sanakis Y., Katsaros N., Karaliota A., Psomas G., Transition metal complexes with the quinolone antibacterial agent pipemidic acid: synthesis, characterization and biological activity, Polyhedron, 2007, 26, 1148-115810.1016/j.poly.2006.10.017Search in Google Scholar

[28] Yang L., Tao D., Yang X., Li Y., Guo Y., Synthesis, Characterization, and Antibacterial Activities of Some Rare Earth Metal Complexes of Pipemidic Acid, Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 51, 494-498.10.1248/cpb.51.494Search in Google Scholar

[29] Lippmaa E., Samoson A., Mägi M., High-resolution aluminum-27 NMR of aluminosilicates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108,1730-1735.10.1021/ja00268a002Search in Google Scholar

[30] D.A. Skoog, D.M. West, J. Holler, R. Stanley, Analytical Chemistry, Sanders College Publising, New York, 1997.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Lima E., Pfeiffer H., Flores J., Some consequences of the fluorination of brucite-like layers in layered double hydroxides: Adsorption, Appl. Clay. Sc. 2014, 88-89, 26-32.10.1016/j.clay.2013.12.011Search in Google Scholar

[32] Xue T., Gao Y., Zhang Y., Umar A., Yan X., Zhang X., Guo Z., Wang Q., Adsorption of acid red from dye wastewater by Zn2Al-NO3 LDHs and the resource of adsorbent sludge as nanofiller for polypropylene, J. Alloys and Compounds, 2014, 587, 99–104.10.1016/j.jallcom.2013.10.158Search in Google Scholar

© 2018 Alejandra Santana Cruz et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The effect of CuO modification for a TiO2 nanotube confined CeO2 catalyst on the catalytic combustion of butane

- The preparation and antibacterial activity of cellulose/ZnO composite: a review

- Linde Type A and nano magnetite/NaA zeolites: cytotoxicity and doxorubicin loading efficiency

- Performance and thermal decomposition analysis of foaming agent NPL-10 for use in heavy oil recovery by steam injection

- Spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, UV, 1H and 13C NMR) insights, electronic profiling and DFT computations on ({(E)-[3-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-1-phenylpropylidene] amino}oxy)(4-nitrophenyl)methanone, an imidazole-bearing anti-Candida agent

- A Simplistic Preliminary Assessment of Ginstling-Brounstein Model for Solid Spherical Particles in the Context of a Diffusion-Controlled Synthesis

- M-Polynomials And Topological Indices Of Zigzag And Rhombic Benzenoid Systems

- Photochemical Transformation of some 3-benzyloxy-2-(benzo[b]thiophen-2-yl)-4Hchromen-4-ones: A Remote Substituent Effect

- Dynamic Changes of Secondary Metabolites and Antioxidant Activity of Ligustrum lucidum During Fruit Growth

- Studies on the flammability of polypropylene/ammonium polyphosphate and montmorillonite by using the cone calorimeter test

- DSC, FT-IR, NIR, NIR-PCA and NIR-ANOVA for determination of chemical stability of diuretic drugs: impact of excipients

- Antioxidant and Hepatoprotective Effects of Methanolic Extracts of Zilla spinosa and Hammada elegans Against Carbon Tetrachlorideinduced Hepatotoxicity in Rats

- Prunus cerasifera Ehrh. fabricated ZnO nano falcates and its photocatalytic and dose dependent in vitro bio-activity

- Organic biocides hosted in layered double hydroxides: enhancing antimicrobial activity

- Experimental study on the regulation of the cholinergic pathway in renal macrophages by microRNA-132 to alleviate inflammatory response

- Synthesis, characterization, in-vitro antimicrobial properties, molecular docking and DFT studies of 3-{(E)-[(4,6-dimethylpyrimidin-2-yl)imino]methyl} naphthalen-2-ol and Heteroleptic Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Zn(II) complexes

- M-Polynomials and Topological Indices of Dominating David Derived Networks

- Human Health Risk Assessment of Trace Metals in Surface Water Due to Leachate from the Municipal Dumpsite by Pollution Index: A Case Study from Ndawuse River, Abuja, Nigeria

- Analysis of Bowel Diseases from Blood Serum by Autofluorescence and Atomic Force Microscopy Techniques

- Hydrographic parameters and distribution of dissolved Cu, Ni, Zn and nutrients near Jeddah desalination plant

- Relationships between diatoms and environmental variables in industrial water biotopes of Trzuskawica S.A. (Poland)

- Optimum Conversion of Major Ginsenoside Rb1 to Minor Ginsenoside Rg3(S) by Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Acid Hydrolysis Treatment

- Antioxidant, Anti-microbial Properties and Chemical Composition of Cumin Essential Oils Extracted by Three Methods

- Regulatory mechanism of ulinastatin on autophagy of macrophages and renal tubular epithelial cells

- Investigation of the sustained-release mechanism of hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose skeleton type Acipimox tablets

- Bio-accumulation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Grey Mangrove (Avicennia marina) along Arabian Gulf, Saudi Coast

- Dynamic Change of Secondary Metabolites and spectrum-effect relationship of Malus halliana Koehne flowers during blooming

- Lipids constituents from Gardenia aqualla Stapf & Hutch

- Effect of using microwaves for catalysts preparation on the catalytic acetalization of glycerol with furfural to obtain fuel additives

- Effect of Humic Acid on the Degradation of Methylene Blue by Peroxymonosulfate

- Serum containing drugs of Gua Lou Xie Bai decoction (GLXB-D) can inhibit TGF-β1-Induced Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in A549 Cells

- Antiulcer Activity of Different Extracts of Anvillea garcinii and Isolation of Two New Secondary Metabolites

- Analysis of Metabolites in Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz Dry Red Wines from Shanxi by 1H NMR Spectroscopy Combined with Pattern Recognition Analysis

- Can water temperature impact litter decomposition under pollution of copper and zinc mixture

- Released from ZrO2/SiO2 coating resveratrol inhibits senescence and oxidative stress of human adipose-derived stem cells (ASC)

- Validated thin-layer chromatographic method for alternative and simultaneous determination of two anti-gout agents in their fixed dose combinations

- Fast removal of pollutants from vehicle emissions during cold-start stage

- Review Article

- Catalytic activities of heterogeneous catalysts obtained by copolymerization of metal-containing 2-(acetoacetoxy)ethyl methacrylate

- Antibiotic Residue in the Aquatic Environment: Status in Africa

- Regular Articles

- Mercury fractionation in gypsum using temperature desorption and mass spectrometric detection

- Phytosynthetic Ag doped ZnO nanoparticles: Semiconducting green remediators

- Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Induced by SMAD4 Activation in Invasive Growth Hormone-Secreting Adenomas

- Physicochemical properties of stabilized sewage sludge admixtures by modified steel slag

- In Vitro Cytotoxic and Antiproliferative Activity of Cydonia oblonga flower petals, leaf and fruit pellet ethanolic extracts. Docking simulation of the active flavonoids on anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2

- Synthesis and Characterization of Pd exchanged MMT Clay for Mizoroki-Heck Reaction

- A new selective, and sensitive method for the determination of lixivaptan, a vasopressin 2 (V2)-receptor antagonist, in mouse plasma and its application in a pharmacokinetic study

- Anti-EGFL7 antibodies inhibit rat prolactinoma MMQ cells proliferation and PRL secretion

- Density functional theory calculations, vibration spectral analysis and molecular docking of the antimicrobial agent 6-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-ylmethyl)-5-ethyl-2-{[2-(morpholin-4-yl)ethyl] sulfanyl}pyrimidin-4(3H)-one

- Effect of Nano Zeolite on the Transformation of Cadmium Speciation and Its Uptake by Tobacco in Cadmium-contaminated Soil

- Effects and Mechanisms of Jinniu Capsule on Methamphetamine-Induced Conditioned Place Preference in Rats

- Calculating the Degree-based Topological Indices of Dendrimers

- Efficient optimization and mineralization of UV absorbers: A comparative investigation with Fenton and UV/H2O2

- Metabolites of Tryptophane and Phenylalanine as Markers of Small Bowel Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

- Adsorption and determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water through the aggregation of graphene oxide

- The role of NR2C2 in the prolactinomas

- Chromium removal from industrial wastewater using Phyllostachys pubescens biomass loaded Cu-S nanospheres

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Preparation of Calcium Fluoride using Phosphogypsum by Orthogonal Experiment

- The mechanism of antibacterial activity of corylifolinin against three clinical bacteria from Psoralen corylifolia L

- 2-formyl-3,6-bis(hydroxymethyl)phenyl benzoate in Electrochemical Dry Cell

- Electro-photocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin using calcium titanate

- Effect of Malus halliana Koehne Polysaccharides on Functional Constipation

- Structural Properties and Nonlinear Optical Responses of Halogenated Compounds: A DFT Investigation on Molecular Modelling

- DMFDMA catalyzed synthesis of 2-((Dimethylamino)methylene)-3,4-dihydro-9-arylacridin-1(2H)-ones and their derivatives: in-vitro antifungal, antibacterial and antioxidant evaluations

- Production of Methanol as a Fuel Energy from CO2 Present in Polluted Seawater - A Photocatalytic Outlook

- Study of different extraction methods on finger print and fatty acid of raw beef fat using fourier transform infrared and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- Determination of trace fluoroquinolones in water solutions and in medicinal preparations by conventional and synchronous fluorescence spectrometry

- Extraction and determination of flavonoids in Carthamus tinctorius

- Therapeutic Application of Zinc and Vanadium Complexes against Diabetes Mellitus a Coronary Disease: A review

- Study of calcined eggshell as potential catalyst for biodiesel formation using used cooking oil

- Manganese oxalates - structure-based Insights

- Topological Indices of H-Naphtalenic Nanosheet

- Long-Term Dissolution of Glass Fibers in Water Described by Dissolving Cylinder Zero-Order Kinetic Model: Mass Loss and Radius Reduction

- Topological study of the para-line graphs of certain pentacene via topological indices

- A brief insight into the prediction of water vapor transmissibility in highly impermeable hybrid nanocomposites based on bromobutyl/epichlorohydrin rubber blends

- Comparative sulfite assay by voltammetry using Pt electrodes, photometry and titrimetry: Application to cider, vinegar and sugar analysis

- MicroRNA delivery mediated by PEGylated polyethylenimine for prostate cancer therapy

- Reversible Fluorescent Turn-on Sensors for Fe3+ based on a Receptor Composed of Tri-oxygen Atoms of Amide Groups in Water

- Sonocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in aqueous solution using Fe-doped TiO2 nanoparticles under mechanical agitation

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Production and Analysis of Recycled Ammonium Perrhenate from CMSX-4 superalloys

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- New phosphorus biofertilizers from renewable raw materials in the aspect of cadmium and lead contents in soil and plants

- Survey of content of cadmium, calcium, chromium, copper, iron, lead, magnesium, manganese, mercury, sodium and zinc in chamomile and green tea leaves by electrothermal or flame atomizer atomic absorption spectrometry

- Biogas digestate – benefits and risks for soil fertility and crop quality – an evaluation of grain maize response

- A numerical analysis of heat transfer in a cross-current heat exchanger with controlled and newly designed air flows

- Freshwater green macroalgae as a biosorbent of Cr(III) ions

- The main influencing factors of soil mechanical characteristics of the gravity erosion environment in the dry-hot valley of Jinsha river

- Free amino acids in Viola tricolor in relation to different habitat conditions

- The influence of filler amount on selected properties of new experimental resin dental composite

- Effect of poultry wastewater irrigation on nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon contents in farmland soil

- Response of spring wheat to NPK and S fertilization. The content and uptake of macronutrients and the value of ionic ratios

- The Effect of Macroalgal Extracts and Near Infrared Radiation on Germination of Soybean Seedlings: Preliminary Research Results

- Content of Zn, Cd and Pb in purple moor-grass in soils heavily contaminated with heavy metals around a zinc and lead ore tailing landfill

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Synthesis of (±)-3,4-dimethoxybenzyl-4-methyloctanoate as a novel internal standard for capsinoid determination by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS(QTOF)

- Repellent activity of monoterpenoid esters with neurotransmitter amino acids against yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti

- Effect of Flammulina velutipes (golden needle mushroom, eno-kitake) polysaccharides on constipation

- Bioassay-directed fractionation of a blood coagulation factor Xa inhibitor, betulinic acid from Lycopus lucidus

- Antifungal and repellent activities of the essential oils from three aromatic herbs from western Himalaya

- Chemical composition and microbiological evaluation of essential oil from Hyssopus officinalis L. with white and pink flowers

- Bioassay-guided isolation and identification of Aedes aegypti larvicidal and biting deterrent compounds from Veratrum lobelianum

- α-Terpineol, a natural monoterpene: A review of its biological properties

- Utility of essential oils for development of host-based lures for Xyleborus glabratus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae), vector of laurel wilt

- Phenolic composition and antioxidant potential of different organs of Kazakh Crataegus almaatensis Pojark: A comparison with the European Crataegus oxyacantha L. flowers

- Isolation of eudesmane type sesquiterpene ketone from Prangos heyniae H.Duman & M.F.Watson essential oil and mosquitocidal activity of the essential oils

- Comparative analysis of the polyphenols profiles and the antioxidant and cytotoxicity properties of various blue honeysuckle varieties

- Special Issue on ICCESEN 2017

- Modelling world energy security data from multinomial distribution by generalized linear model under different cumulative link functions

- Pine Cone and Boron Compounds Effect as Reinforcement on Mechanical and Flammability Properties of Polyester Composites

- Artificial Neural Network Modelling for Prediction of SNR Effected by Probe Properties on Ultrasonic Inspection of Austenitic Stainless Steel Weldments

- Calculation and 3D analyses of ERR in the band crack front contained in a rectangular plate made of multilayered material

- Improvement of fuel properties of biodiesel with bioadditive ethyl levulinate

- Properties of AlSi9Cu3 metal matrix micro and nano composites produced via stir casting

- Investigation of Antibacterial Properties of Ag Doped TiO2 Nanofibers Prepared by Electrospinning Process

- Modeling of Total Phenolic contents in Various Tea samples by Experimental Design Methods

- Nickel doping effect on the structural and optical properties of indium sulfide thin films by SILAR

- The effect mechanism of Ginnalin A as a homeopathic agent on various cancer cell lines

- Excitation functions of proton induced reactions of some radioisotopes used in medicine

- Oxide ionic conductivity and microstructures of Pr and Sm co-doped CeO2-based systems

- Rapid Synthesis of Metallic Reinforced in Situ Intermetallic Composites in Ti-Al-Nb System via Resistive Sintering

- Oxidation Behavior of NiCr/YSZ Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs)

- Clustering Analysis of Normal Strength Concretes Produced with Different Aggregate Types

- Magnetic Nano-Sized Solid Acid Catalyst Bearing Sulfonic Acid Groups for Biodiesel Synthesis

- The biological activities of Arabis alpina L. subsp. brevifolia (DC.) Cullen against food pathogens

- Humidity properties of Schiff base polymers

- Free Vibration Analysis of Fiber Metal Laminated Straight Beam

- Comparative study of in vitro antioxidant, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase activity of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) collected during different growth stages

- Isothermal Oxidation Behavior of Gadolinium Zirconate (Gd2Zr2O7) Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs) produced by Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition (EB-PVD) technique

- Optimization of Adsorption Parameters for Ultra-Fine Calcite Using a Box-Behnken Experimental Design

- The Microstructural Investigation of Vermiculite-Infiltrated Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition Thermal Barrier Coatings

- Modelling Porosity Permeability of Ceramic Tiles using Fuzzy Taguchi Method

- Experimental and theoretical study of a novel naphthoquinone Schiff base

- Physicochemical properties of heat treated sille stone for ceramic industry

- Sand Dune Characterization for Preparing Metallurgical Grade Silicon

- Catalytic Applications of Large Pore Sulfonic Acid-Functionalized SBA-15 Mesoporous Silica for Esterification

- One-photon Absorption Characterizations, Dipole Polarizabilities and Second Hyperpolarizabilities of Chlorophyll a and Crocin

- The Optical and Crystallite Characterization of Bilayer TiO2 Films Coated on Different ITO layers

- Topical Issue on Bond Activation

- Metal-mediated reactions towards the synthesis of a novel deaminolysed bisurea, dicarbamolyamine

- The structure of ortho-(trifluoromethyl)phenol in comparison to its homologues – A combined experimental and theoretical study

- Heterogeneous catalysis with encapsulated haem and other synthetic porphyrins: Harnessing the power of porphyrins for oxidation reactions

- Recent Advances on Mechanistic Studies on C–H Activation Catalyzed by Base Metals

- Reactions of the organoplatinum complex [Pt(cod) (neoSi)Cl] (neoSi = trimethylsilylmethyl) with the non-coordinating anions SbF6– and BPh4–

- Erratum

- Investigation on Two Compounds of O, O’-dithiophosphate Derivatives as Corrosion Inhibitors for Q235 Steel in Hydrochloric Acid Solution

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The effect of CuO modification for a TiO2 nanotube confined CeO2 catalyst on the catalytic combustion of butane

- The preparation and antibacterial activity of cellulose/ZnO composite: a review

- Linde Type A and nano magnetite/NaA zeolites: cytotoxicity and doxorubicin loading efficiency

- Performance and thermal decomposition analysis of foaming agent NPL-10 for use in heavy oil recovery by steam injection

- Spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, UV, 1H and 13C NMR) insights, electronic profiling and DFT computations on ({(E)-[3-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-1-phenylpropylidene] amino}oxy)(4-nitrophenyl)methanone, an imidazole-bearing anti-Candida agent

- A Simplistic Preliminary Assessment of Ginstling-Brounstein Model for Solid Spherical Particles in the Context of a Diffusion-Controlled Synthesis

- M-Polynomials And Topological Indices Of Zigzag And Rhombic Benzenoid Systems

- Photochemical Transformation of some 3-benzyloxy-2-(benzo[b]thiophen-2-yl)-4Hchromen-4-ones: A Remote Substituent Effect

- Dynamic Changes of Secondary Metabolites and Antioxidant Activity of Ligustrum lucidum During Fruit Growth

- Studies on the flammability of polypropylene/ammonium polyphosphate and montmorillonite by using the cone calorimeter test

- DSC, FT-IR, NIR, NIR-PCA and NIR-ANOVA for determination of chemical stability of diuretic drugs: impact of excipients

- Antioxidant and Hepatoprotective Effects of Methanolic Extracts of Zilla spinosa and Hammada elegans Against Carbon Tetrachlorideinduced Hepatotoxicity in Rats

- Prunus cerasifera Ehrh. fabricated ZnO nano falcates and its photocatalytic and dose dependent in vitro bio-activity

- Organic biocides hosted in layered double hydroxides: enhancing antimicrobial activity

- Experimental study on the regulation of the cholinergic pathway in renal macrophages by microRNA-132 to alleviate inflammatory response

- Synthesis, characterization, in-vitro antimicrobial properties, molecular docking and DFT studies of 3-{(E)-[(4,6-dimethylpyrimidin-2-yl)imino]methyl} naphthalen-2-ol and Heteroleptic Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Zn(II) complexes

- M-Polynomials and Topological Indices of Dominating David Derived Networks

- Human Health Risk Assessment of Trace Metals in Surface Water Due to Leachate from the Municipal Dumpsite by Pollution Index: A Case Study from Ndawuse River, Abuja, Nigeria

- Analysis of Bowel Diseases from Blood Serum by Autofluorescence and Atomic Force Microscopy Techniques

- Hydrographic parameters and distribution of dissolved Cu, Ni, Zn and nutrients near Jeddah desalination plant

- Relationships between diatoms and environmental variables in industrial water biotopes of Trzuskawica S.A. (Poland)

- Optimum Conversion of Major Ginsenoside Rb1 to Minor Ginsenoside Rg3(S) by Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Acid Hydrolysis Treatment

- Antioxidant, Anti-microbial Properties and Chemical Composition of Cumin Essential Oils Extracted by Three Methods

- Regulatory mechanism of ulinastatin on autophagy of macrophages and renal tubular epithelial cells

- Investigation of the sustained-release mechanism of hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose skeleton type Acipimox tablets

- Bio-accumulation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Grey Mangrove (Avicennia marina) along Arabian Gulf, Saudi Coast

- Dynamic Change of Secondary Metabolites and spectrum-effect relationship of Malus halliana Koehne flowers during blooming

- Lipids constituents from Gardenia aqualla Stapf & Hutch

- Effect of using microwaves for catalysts preparation on the catalytic acetalization of glycerol with furfural to obtain fuel additives

- Effect of Humic Acid on the Degradation of Methylene Blue by Peroxymonosulfate

- Serum containing drugs of Gua Lou Xie Bai decoction (GLXB-D) can inhibit TGF-β1-Induced Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in A549 Cells

- Antiulcer Activity of Different Extracts of Anvillea garcinii and Isolation of Two New Secondary Metabolites

- Analysis of Metabolites in Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz Dry Red Wines from Shanxi by 1H NMR Spectroscopy Combined with Pattern Recognition Analysis

- Can water temperature impact litter decomposition under pollution of copper and zinc mixture

- Released from ZrO2/SiO2 coating resveratrol inhibits senescence and oxidative stress of human adipose-derived stem cells (ASC)

- Validated thin-layer chromatographic method for alternative and simultaneous determination of two anti-gout agents in their fixed dose combinations

- Fast removal of pollutants from vehicle emissions during cold-start stage

- Review Article

- Catalytic activities of heterogeneous catalysts obtained by copolymerization of metal-containing 2-(acetoacetoxy)ethyl methacrylate

- Antibiotic Residue in the Aquatic Environment: Status in Africa

- Regular Articles

- Mercury fractionation in gypsum using temperature desorption and mass spectrometric detection

- Phytosynthetic Ag doped ZnO nanoparticles: Semiconducting green remediators

- Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Induced by SMAD4 Activation in Invasive Growth Hormone-Secreting Adenomas

- Physicochemical properties of stabilized sewage sludge admixtures by modified steel slag

- In Vitro Cytotoxic and Antiproliferative Activity of Cydonia oblonga flower petals, leaf and fruit pellet ethanolic extracts. Docking simulation of the active flavonoids on anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2

- Synthesis and Characterization of Pd exchanged MMT Clay for Mizoroki-Heck Reaction

- A new selective, and sensitive method for the determination of lixivaptan, a vasopressin 2 (V2)-receptor antagonist, in mouse plasma and its application in a pharmacokinetic study

- Anti-EGFL7 antibodies inhibit rat prolactinoma MMQ cells proliferation and PRL secretion

- Density functional theory calculations, vibration spectral analysis and molecular docking of the antimicrobial agent 6-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-ylmethyl)-5-ethyl-2-{[2-(morpholin-4-yl)ethyl] sulfanyl}pyrimidin-4(3H)-one

- Effect of Nano Zeolite on the Transformation of Cadmium Speciation and Its Uptake by Tobacco in Cadmium-contaminated Soil

- Effects and Mechanisms of Jinniu Capsule on Methamphetamine-Induced Conditioned Place Preference in Rats

- Calculating the Degree-based Topological Indices of Dendrimers

- Efficient optimization and mineralization of UV absorbers: A comparative investigation with Fenton and UV/H2O2

- Metabolites of Tryptophane and Phenylalanine as Markers of Small Bowel Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

- Adsorption and determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water through the aggregation of graphene oxide

- The role of NR2C2 in the prolactinomas

- Chromium removal from industrial wastewater using Phyllostachys pubescens biomass loaded Cu-S nanospheres

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Preparation of Calcium Fluoride using Phosphogypsum by Orthogonal Experiment

- The mechanism of antibacterial activity of corylifolinin against three clinical bacteria from Psoralen corylifolia L

- 2-formyl-3,6-bis(hydroxymethyl)phenyl benzoate in Electrochemical Dry Cell

- Electro-photocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin using calcium titanate

- Effect of Malus halliana Koehne Polysaccharides on Functional Constipation

- Structural Properties and Nonlinear Optical Responses of Halogenated Compounds: A DFT Investigation on Molecular Modelling

- DMFDMA catalyzed synthesis of 2-((Dimethylamino)methylene)-3,4-dihydro-9-arylacridin-1(2H)-ones and their derivatives: in-vitro antifungal, antibacterial and antioxidant evaluations

- Production of Methanol as a Fuel Energy from CO2 Present in Polluted Seawater - A Photocatalytic Outlook

- Study of different extraction methods on finger print and fatty acid of raw beef fat using fourier transform infrared and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- Determination of trace fluoroquinolones in water solutions and in medicinal preparations by conventional and synchronous fluorescence spectrometry

- Extraction and determination of flavonoids in Carthamus tinctorius

- Therapeutic Application of Zinc and Vanadium Complexes against Diabetes Mellitus a Coronary Disease: A review

- Study of calcined eggshell as potential catalyst for biodiesel formation using used cooking oil

- Manganese oxalates - structure-based Insights

- Topological Indices of H-Naphtalenic Nanosheet

- Long-Term Dissolution of Glass Fibers in Water Described by Dissolving Cylinder Zero-Order Kinetic Model: Mass Loss and Radius Reduction

- Topological study of the para-line graphs of certain pentacene via topological indices

- A brief insight into the prediction of water vapor transmissibility in highly impermeable hybrid nanocomposites based on bromobutyl/epichlorohydrin rubber blends

- Comparative sulfite assay by voltammetry using Pt electrodes, photometry and titrimetry: Application to cider, vinegar and sugar analysis

- MicroRNA delivery mediated by PEGylated polyethylenimine for prostate cancer therapy

- Reversible Fluorescent Turn-on Sensors for Fe3+ based on a Receptor Composed of Tri-oxygen Atoms of Amide Groups in Water

- Sonocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in aqueous solution using Fe-doped TiO2 nanoparticles under mechanical agitation

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Production and Analysis of Recycled Ammonium Perrhenate from CMSX-4 superalloys

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- New phosphorus biofertilizers from renewable raw materials in the aspect of cadmium and lead contents in soil and plants

- Survey of content of cadmium, calcium, chromium, copper, iron, lead, magnesium, manganese, mercury, sodium and zinc in chamomile and green tea leaves by electrothermal or flame atomizer atomic absorption spectrometry

- Biogas digestate – benefits and risks for soil fertility and crop quality – an evaluation of grain maize response

- A numerical analysis of heat transfer in a cross-current heat exchanger with controlled and newly designed air flows

- Freshwater green macroalgae as a biosorbent of Cr(III) ions

- The main influencing factors of soil mechanical characteristics of the gravity erosion environment in the dry-hot valley of Jinsha river

- Free amino acids in Viola tricolor in relation to different habitat conditions

- The influence of filler amount on selected properties of new experimental resin dental composite

- Effect of poultry wastewater irrigation on nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon contents in farmland soil

- Response of spring wheat to NPK and S fertilization. The content and uptake of macronutrients and the value of ionic ratios

- The Effect of Macroalgal Extracts and Near Infrared Radiation on Germination of Soybean Seedlings: Preliminary Research Results

- Content of Zn, Cd and Pb in purple moor-grass in soils heavily contaminated with heavy metals around a zinc and lead ore tailing landfill

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Synthesis of (±)-3,4-dimethoxybenzyl-4-methyloctanoate as a novel internal standard for capsinoid determination by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS(QTOF)

- Repellent activity of monoterpenoid esters with neurotransmitter amino acids against yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti

- Effect of Flammulina velutipes (golden needle mushroom, eno-kitake) polysaccharides on constipation

- Bioassay-directed fractionation of a blood coagulation factor Xa inhibitor, betulinic acid from Lycopus lucidus

- Antifungal and repellent activities of the essential oils from three aromatic herbs from western Himalaya

- Chemical composition and microbiological evaluation of essential oil from Hyssopus officinalis L. with white and pink flowers

- Bioassay-guided isolation and identification of Aedes aegypti larvicidal and biting deterrent compounds from Veratrum lobelianum

- α-Terpineol, a natural monoterpene: A review of its biological properties

- Utility of essential oils for development of host-based lures for Xyleborus glabratus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae), vector of laurel wilt

- Phenolic composition and antioxidant potential of different organs of Kazakh Crataegus almaatensis Pojark: A comparison with the European Crataegus oxyacantha L. flowers

- Isolation of eudesmane type sesquiterpene ketone from Prangos heyniae H.Duman & M.F.Watson essential oil and mosquitocidal activity of the essential oils

- Comparative analysis of the polyphenols profiles and the antioxidant and cytotoxicity properties of various blue honeysuckle varieties

- Special Issue on ICCESEN 2017

- Modelling world energy security data from multinomial distribution by generalized linear model under different cumulative link functions

- Pine Cone and Boron Compounds Effect as Reinforcement on Mechanical and Flammability Properties of Polyester Composites

- Artificial Neural Network Modelling for Prediction of SNR Effected by Probe Properties on Ultrasonic Inspection of Austenitic Stainless Steel Weldments

- Calculation and 3D analyses of ERR in the band crack front contained in a rectangular plate made of multilayered material

- Improvement of fuel properties of biodiesel with bioadditive ethyl levulinate

- Properties of AlSi9Cu3 metal matrix micro and nano composites produced via stir casting

- Investigation of Antibacterial Properties of Ag Doped TiO2 Nanofibers Prepared by Electrospinning Process

- Modeling of Total Phenolic contents in Various Tea samples by Experimental Design Methods

- Nickel doping effect on the structural and optical properties of indium sulfide thin films by SILAR

- The effect mechanism of Ginnalin A as a homeopathic agent on various cancer cell lines

- Excitation functions of proton induced reactions of some radioisotopes used in medicine

- Oxide ionic conductivity and microstructures of Pr and Sm co-doped CeO2-based systems

- Rapid Synthesis of Metallic Reinforced in Situ Intermetallic Composites in Ti-Al-Nb System via Resistive Sintering

- Oxidation Behavior of NiCr/YSZ Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs)

- Clustering Analysis of Normal Strength Concretes Produced with Different Aggregate Types

- Magnetic Nano-Sized Solid Acid Catalyst Bearing Sulfonic Acid Groups for Biodiesel Synthesis

- The biological activities of Arabis alpina L. subsp. brevifolia (DC.) Cullen against food pathogens

- Humidity properties of Schiff base polymers

- Free Vibration Analysis of Fiber Metal Laminated Straight Beam

- Comparative study of in vitro antioxidant, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase activity of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) collected during different growth stages

- Isothermal Oxidation Behavior of Gadolinium Zirconate (Gd2Zr2O7) Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs) produced by Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition (EB-PVD) technique

- Optimization of Adsorption Parameters for Ultra-Fine Calcite Using a Box-Behnken Experimental Design

- The Microstructural Investigation of Vermiculite-Infiltrated Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition Thermal Barrier Coatings

- Modelling Porosity Permeability of Ceramic Tiles using Fuzzy Taguchi Method

- Experimental and theoretical study of a novel naphthoquinone Schiff base

- Physicochemical properties of heat treated sille stone for ceramic industry

- Sand Dune Characterization for Preparing Metallurgical Grade Silicon

- Catalytic Applications of Large Pore Sulfonic Acid-Functionalized SBA-15 Mesoporous Silica for Esterification

- One-photon Absorption Characterizations, Dipole Polarizabilities and Second Hyperpolarizabilities of Chlorophyll a and Crocin

- The Optical and Crystallite Characterization of Bilayer TiO2 Films Coated on Different ITO layers

- Topical Issue on Bond Activation

- Metal-mediated reactions towards the synthesis of a novel deaminolysed bisurea, dicarbamolyamine

- The structure of ortho-(trifluoromethyl)phenol in comparison to its homologues – A combined experimental and theoretical study

- Heterogeneous catalysis with encapsulated haem and other synthetic porphyrins: Harnessing the power of porphyrins for oxidation reactions

- Recent Advances on Mechanistic Studies on C–H Activation Catalyzed by Base Metals

- Reactions of the organoplatinum complex [Pt(cod) (neoSi)Cl] (neoSi = trimethylsilylmethyl) with the non-coordinating anions SbF6– and BPh4–

- Erratum

- Investigation on Two Compounds of O, O’-dithiophosphate Derivatives as Corrosion Inhibitors for Q235 Steel in Hydrochloric Acid Solution