A new selective, and sensitive method for the determination of lixivaptan, a vasopressin 2 (V2)-receptor antagonist, in mouse plasma and its application in a pharmacokinetic study

Abstract

A new, selective and sensitive HPLC method for the determination of lixivaptan, an oral selective vasopressin 2 (V2)-receptor antagonist, was investigated and validated. A Waters symmetry C18 column was used as a stationary phase in isocratic elution mode using a mobile phase composed of KH2PO4 (100 mM)-acetonitrile (40: 60, v/v) at a flow rate of 1.5 mL min-1. Diclofenac was used as the internal standard (IS). Lixivaptan and the IS were extracted from plasma by protein precipitation and were detected at 260 nm. Lixivaptan and diclofenac were eluted at 3.6 and 6.2 min, respectively. The developed method showed good linearity over the calibration range of 50 -1000 ng mL-1 with a lower limit of detection of 16.5 ng mL-1. The extraction percentage of lixivaptan in the mouse plasma was in the range of 88.88 - 114.43%, which indicates acceptable extraction. The aforementioned method was validated according to guidelines of the International Council on Harmonization (ICH). The intra- and inter-day coefficients of variation did not exceed 5.5%. This method was presented to be simple, sensitive, and accurate and was successfully adapted in a pharmacokinetic study of the profile of lixivaptan in mouse plasma. A mean maximum plasma concentration of lixivaptan of 113.82 ng mL-1 was achieved in 0.5 h after oral administration of a 10 mg kg-1 dose in mouse as determined using the developed method.

1 Introduction

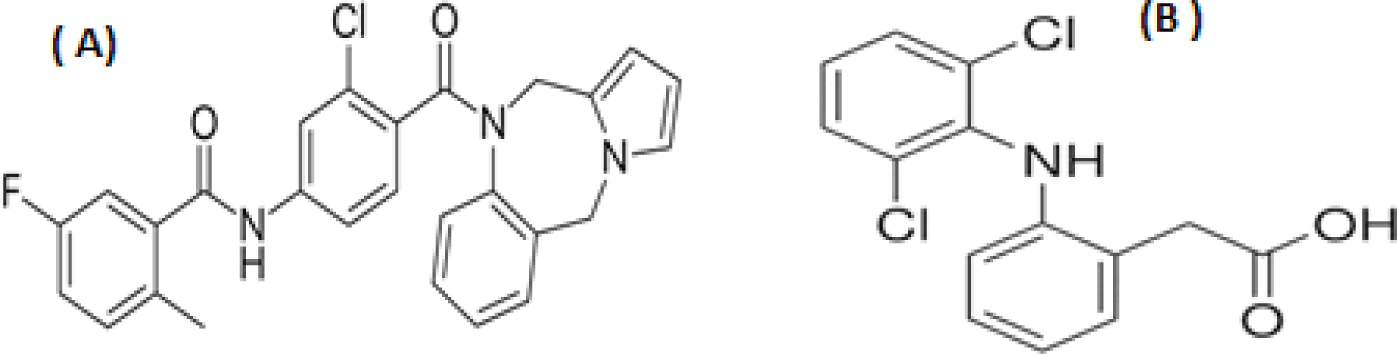

Lixivaptan (LIX) is an orally-administered pharmacological compound used as an antagonist of vasopressin, a hormone that is associated with heart failure [1, 2] and has a role in maintaining water balance in the body. Lixivaptan functions by blocking the vasopressin 2 (V2) receptor and can potentially be used for the treatment of hyponatremia [3,4,5]. Hyponatremia is the condition in which the concentration of sodium in the blood is lower than normal. Lixivaptan can eliminate excess fluids from the body and keep blood sodium levels within the normal range. It is a selective nonpeptide V2 antagonist [3, 4] and a chemical derivative of benzodiazepine, with the chemical name 5-fluoro- 2-methyl-N-[4-(5H-pyrrolo[2,1-c]-[1,4]benzodiazepin- 10(11H)-ylcarbonyl)-3 chlorophenyl]benzamide (Figure 1) [6]. Lixivaptan strongly binds to V2 receptors in the kidneys, preventing the insertion of aquaporin channels into the apical membrane layer, thus resulting in an increase in solute-free water excretion and sodium retention [7].

Chemical structure of: (A) lixivaptan and (B) the internal standard (IS) diclofenac (DC).

Several studies were directed toward assessing the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of lixivaptan [8,9,10,11]. Lixivaptan is absorbed quickly with a mean estimated Tmax of < 1 h. A crosswise analysis showed that the rate of clearance, volume of distribution, and half-life of lixivaptan were in a correlation between the LIX concentration with free water clearance [10]. The pharmacokinetic study need to highly sensitive technique to determine LIX in lower concentration as well as their detection in plasma metrics without interferences. Therefor this study aimed to develop an HPLC for determination of LIX in mice plasma and its application to pharmacokinetic study.

Validation of any developed method is essential in order to prove that the method is acceptable for the proposed use. The proposed method should also satisfy criteria related to estimating the drug in biological fluids or various matrices (biological samples) as well as in clinical studies [12,13,14]. We therefore developed a new HPLC method to which international standards, such as the guidelines of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [15] and the International Council for Harmonization (ICH) [16], were accordingly applied for validation.

The rationale for choosing HPLC is based on the advantages of this technique, including its simplicity, sensitivity and accuracy, which have made it commonly used for drug analysis in many laboratories [17,18,19]. The proposed HPLC method involves detection via ultraviolet spectroscopy, and it was optimized according to the selected validation criteria [15, 16]. This work represents a complementary study to our initial work, which was based on HPLC-MS/MS analysis [20].

In the present investigation, a sensitive, selective, and accurate HPLC-UV method is proposed for the assay of lixivaptan in mouse plasma. A protein precipitation procedure as an extraction method was used for extracting lixivaptan from mouse plasma. The validation parameters of lixivaptan determination as a bioanalytical method were optimized according to ICH guidelines. The suggested method was successfully applied in a pharmacokinetic study of lixivaptan in mouse plasma.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Reagents and materials

Lixivaptan and diclofenac sodium (DC) (Figure 1) of purity > 99% (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) were used as references in this study. HPLC-grade acetonitrile and methanol were purchased from Zeus Quimica S.A (Barcelona, Spain). Analytical grade “potassium dihydrogen phosphate, phosphoric acid, perchloric acid and trifluoroacetic acid were acquired from AVONCHEM (Macclesfield, Cheshire, England). Double distilled water was produced using a cartridge system (Waters Millipore, Milford, USA)”. Naltrexone hydrochloride, cyclobenzaprine hydrochloride, clonidine hydrochloride, tizanidine hydrochloride, pravastatin sodium, fenofibrate, fenofibric acid, phenobarbital sodium, and 7-Methyl- 6,7,8,9,14,15-hexahydro-5H-benz[d]indolo[2,3-g]azecine (LE 300) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo, USA).

2.2 Apparatus and chromatographic conditions

“The HPLC analysis was carried out using a Waters HPLC system (Milford, USA) equipped with 1500 series HPLC pump”, operated at a flow rate of 1.5 mL min-1. A dualwavelength “ultraviolet detector (2489) and an autosampler (717plus)” were used. Data were collected with an “Empower pro Chromatography Manager for data acquisition and analysis”.

Chromatographic separations were completed using an analytical Waters Symmetry “C18 analytical column (125 mm ´ 4.6 mm i.d. ´ 3 μm particle size (Waters, USA) coupled with a Symmetry C18 sentry guard column (20 mm)”. All solutions were degassed by “ultra-sonication and filtered through a 0.45 μm filter (Millipore)”.

The mobile phase consisted of KH2PO4 (100 mM) and acetonitrile (40: 60, v/v). All separations were achieved in isocratic mode at a flow rate of 1.5 mL min-1 at 25°C. The injection volume was 50μL and the absorbance of eluents was recorded at 260 nm.

2.3 Preparation of solutions and plasma samples

Stock solutions of lixivaptan and DC were prepared by dissolving a quantity of the drug and standard in acetonitrile and methanol, respectively, to yield a concentration of 1 mg mL.1 Three working solutions of LIX (100 and 10 and 1 μg mL-1 ) and two working solution of DC (100 and 10 μg mL-1) were prepared by suitable dilution. All solutions were stored at 4°C.

Mouse plasma (100 μL) was spiked with a suitable amount of lixivaptan ( 10 and 1 μg mL-1) and DC (10 μg mL-1) to give a final concentration of 50, 100, 200, 400, 800, and 1000 ng mL-1 lixivaptan and 2 μg mL-1 DC, with each sample being prepared in a 2.0 mL disposable polypropylene micro-centrifuge tube. Then, 500 μL acetonitrile was added to induce protein precipitation, and each tube was vortexed for about 1 min. The samples were then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm at room temperature (25°C) for 9 min. The upper layer solution was filtered through a simple pure filter (0.22 μm) and the clarified sample was injected into the HPLC system. Analysis of each lixivaptan concentration was repeated six times. The average peak area ratio for each sample was estimated and plotted against LIX concentration. Blank mouse plasma samples were prepared in the same way using the diluting solvent instead of lixivaptan and DC.

2.4 Bioanalytical method of validation

The linearity of the method was evaluated according to ICH guidelines [16]. A calibration graph was obtained by plotting the area ratios of lixivaptan to DC (IS) against the initial lixivaptan concentration. The equation of the calibration curve was obtained using the fitting of the plot. Calibration plots for lixivaptan were prepared using six concentration points (50, 100, 200, 400, 800, and 1000 ng mL-1). Each concentration point was repeated six times, and the average value was calculated and used to plot the calibration graph.

The accuracy of the determination of lixivaptan was assessed explicitly by spiking known concentrations of lixivaptan into mouse plasma. The % recovery was calculated using the following formula: ([peak area ratio of extract/mean peak area ratio of un-extracted drug] ´100).

The intra-day and inter-day precisions of the lixivaptan assay were calculated by the repeatability of the analysis of three quality control samples (75, 300 and 700 ng mL-1) within the same day or in three different days, respectively. The accuracy and precision of the established method for lixivaptan were determined according to ICH guidelines for bio-analytical method validation [16].

The stability of lixivaptan in mouse plasma was evaluated using three replicate samples of QC concentrations (75, 300, and 750 ng mL-1). The stability conditions were: at 25°C (room temperature) for 8 h, at - 4°C for one week, and in the auto-sampler tray for 12 h. Calculation of accuracy and precision of the quality control samples was carried out using a calibration curve based on fresh mouse plasma.

2.5 Pharmacokinetic Application

2.5.1 Animal maintenance

Adult male white” Swiss albino mice” weighing 25-30 g (10 - 12 weeks old) were obtained from the “Experimental Animal Care Center, King Saud University”. The animals were maintained in an “air-conditioned animal house at a temperature of 25-28°C, relative humidity of 50%, and 12:12h light and dark photo-cycle”. The animals were provided with standard diet pellets and water ad libitum.The experiments were approved by the “Ethics Committee of the Experimental Animal Care Society, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.”

2.5.2 Pharmacokinetic study

After two days of housing, the mice were randomly divided into eight groups (six mice each), then seven of the groups were orally administered with 10 mg kg-1 of lixivaptan, and the remaining group was administered “dimethyl sulfoxide in saline to serve as blank mouse plasma” [21]. The injection volume of the drug was 0.01 mL g-1 body weight. Lixivaptan was administered at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, and 8h before blood sampling. Each time point was repeated six times with different mice. The blood samples were withdrawn from the heart (1.0 mL). The plasma samples were separated from the serum by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 5 min, and then preserved at -20°C until analysis.

3 Results and discussion

This study describes an HPLC-UV method for the assay of lixivaptan. To select an internal standard (IS), we tested different drugs with similar chemical structures or pKa values to the drug, including naltrexone, cyclobenzaprine, clonidine, tizanidine, pravastatin, fenofibrate, fenofibric acid, LE 300, and phenobarbital sodium. Most of the tested drugs failed because they had short elution times (less than 1 min), because they interfered with lixivaptan, or because an excessively large separation was obtained. DC was selected as the IS for the quantification of lixivaptan because it was separated at a suitable elution time of approximately 3.6 min under optimal chromatographic separation conditions.

Suitable chromatographic conditions were studied and optimized through multiple trials to achieve good resolution and a symmetric peak shape for lixivaptan and DC, as well as a suitable elution time. For the optimization of the mobile phase composition, different mobile phase components, such as methanol, water and acetonitrile in different ratios, were tested. Acetonitrile: KH2PO4 showed better separation than methanol: KH2PO4; however, the resolution was still not complete, and approximately 1.2 (about 90%) resolution was obtained. Another trial involved the use of KH2PO4 of different ionic strengths (25, 50, and 100 mM), and 100 mM appeared to be the most suitable ionic strength to obtain satisfactory resolution.

The absorbance spectrum of lixivaptan showed two maxima, at 210 and 260 nm. The peak at 260 nm resulted in acceptable selectivity when compared with that at 210 nm. In addition, at 210 nm, the blank showed a higher absorbance intensity compared with that at 260 nm. Therefore, the optimal conditions of chromatographic separation were found to be a mobile phase consisting of acetonitrile:100 mM KH2PO4, 60:40 (v/v) and detection at wavelength 260 nm. Under these conditions, lixivaptan analysis demonstrated a good capacity factor, separation factor, resolution, and peak symmetry.

3.1 Extraction procedure

A clean-up procedure is often essential to remove plasma proteins prior to analysis. The extraction step in general involves time-consuming and laborious sample pretreatments, which often include the use of liquid or solid phase extraction. A solvent-based protein precipitation method was developed using different solvents such as perchloric acid, trifluoroacetic acid and acetonitrile. The optimal solvent was acetonitrile, which resulted in a good recovery (see Table 1). The extraction recovery of lixivaptan from mouse plasma was in the range of 88.88-114.43%, which is consistent with published standards [12].

Extraction % recovery of lixivaptan from spiked mouse plasma using solvent deproteinization procedure.

| Conc., ng mL-1 | Peak area ratio of standard | Peak area ratio of spiked plasma | Recovery, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 0.048 | 0.044 | 91.66 |

| 100 | 0.090 | 0.080 | 88.88 |

| 200 | 0.180 | 0.170 | 94.44 |

| 400 | 0.370 | 0.420 | 113.51 |

| 800 | 0.840 | 0.760 | 90. 47 |

| 1000 | 0.970 | 1.110 | 114.43 |

n=6

3.2 Specificity

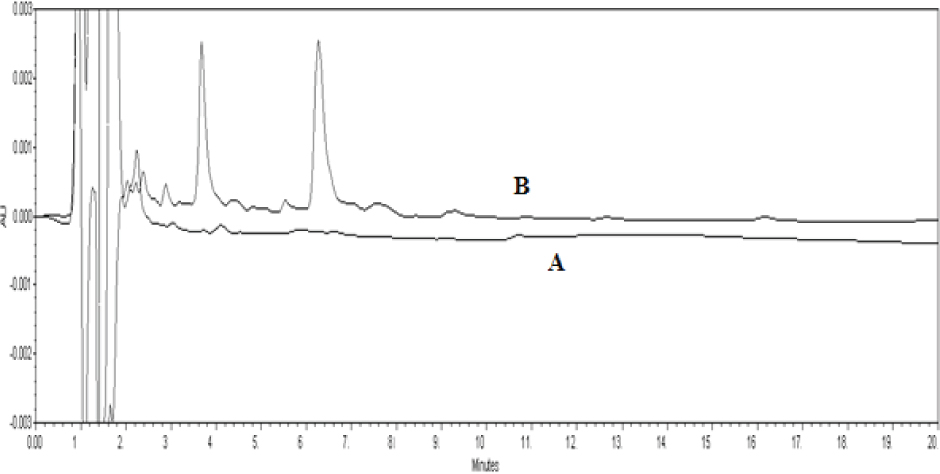

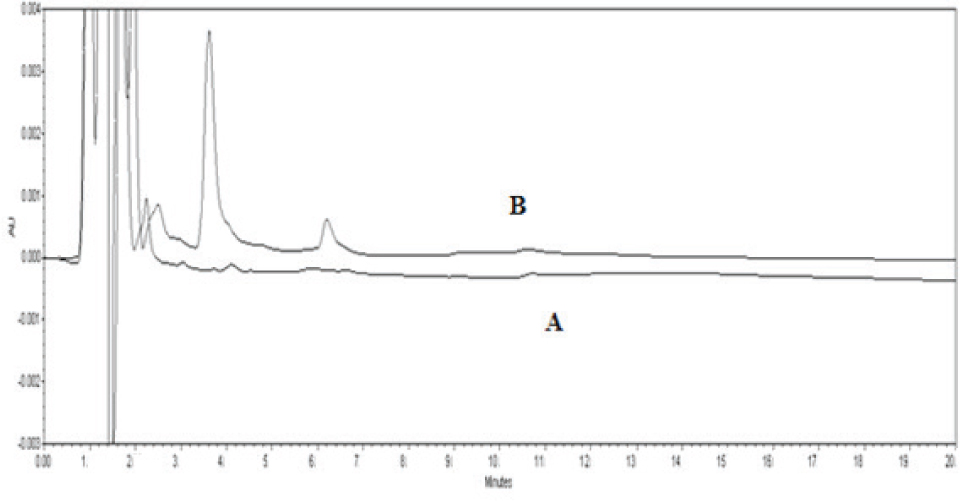

To investigate the specificity of the new method, a variety of blank mouse plasma samples were examined individually to detect any potential interference. Chromatograms of mouse blank plasma and mouse plasma spiked with 2 μg mL-1 DC and 200 ng mL-1 lixivaptan are presented in Figure 2. The peaks of lixivaptan and DC were well resolved at the correct retention times of 6.2 and 3.6 min, respectively. In mouse plasma, no peaks similar to either lixivaptan or DC were observed over the elution time of both the drug and the IS. The analysis was completed within 10 min with complete separation. The protein precipitation procedure of the plasma samples was appropriate for the separation and extraction of the drug from the plasma in the absence of any interference from similar peaks (Figure 3). The system suitability parameters for lixivaptan are listed in Table 2 based on isocratic elution of the drug at a flow rate of 1.5 mL min-1 and a detection wavelength of 260 nm.

HPLC chromatogram of the analysis of lixivaptan in drug-free plasma: (A) blank plasma, (B) mouse plasma spiked with 200 ng mL-1 and 2 μg mL-1 of lixivaptan and DC, respectively.

HPLC chromatograms of mouse plasma (A) at zero time (Blank) and (B) 0.5 h after injection.

Chromatographic system suitability parameters.

| Parameters | RT | K | Selectivity “a” | Resolution “Rs” | Symmetry factor | Number of theoretical plates “N” |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS | 3.6 | 127.16 | 1.5 | - | 1.06 | 2452 |

| Lixivaptan | 6.2 | 210.34 | 2.47 | 6.98 | 1.0 | 3956 |

RT = Retention time

K = Capacity factor for drug and IS

α = Separation factor, calculated as K2/K1, where k = the capacity factor for drug and IS

Rs = 2 (t2 – t1) / (w1 + w2), where t2 and t1 are the retention times of the drug and IS and w2 and w1 are the half-peak width values for the drug and IS, respectively

N = number of theoretical plates = (RT/w)2

3.3 Validation of the Method

3.3.1 Linearity and sensitivity

The investigated method showed good linearity for lixivaptan over the calibration range of 50-1000 ng mL-1 lixivaptan. The regression correlation coefficient was r2 = 0.9989. The calibration curve equation was y = 0.001x- 0.0127. The good linearity of the calibration graph is indicated by the high value of the correlation coefficient and the standard deviation parameters of the obtained calibration curve [22]. Table 3 gives an outline of the general analytical characterization of the investigated method. The lower limit of quantification and lower limit of detection of lixivaptan in mouse plasma was estimated at 50.0 and 16.5 ng mL,-1 respectively (signal-to-noise ratio of 10 or 3)

Analytical parameters of the investigated HPLC method

| Parameter | Value aa |

|---|---|

| Slope | 0.001 |

| Standard error of slope | 3.2×10-5 |

| Intercept | 0.0127 |

| Standard error of intercept | -0.005 |

| STE YX | 0.005 |

| Correlation coefficient, (r2) | 0.9989 |

| Calibration range ( ng mL-1) | 50.0 - 1000.0 |

| LOD (ng mL-1) | 16.50 |

| LOQ (ng mL-1) | 50.0 |

| Retention time of lixivaptan (min) | 3.6 |

| Retention time of IS(min) | 6.2 |

a Values are presented the mean of three determinations.

3.3.2 Accuracy and precision

The accuracy and precision of the studied method were evaluated by assaying different concentrations plotted in the calibration curve, encompassing a broad range of concentrations (75, 300 and 700 ng mL-1) of lixivaptan. The precision of the method was estimated in terms of injection repeatability, analysis repeatability during a single day, and intermediate precision over multiple days. The accuracy and precision of the investigated method were within an adequate range as defined by ICH guidelines [16]. The intra-day accuracy and precision were within the range 95.0-97.77% and 0.94 - 4.63%, respectively. The interday accuracy ranges were 91.0-92.3% and 0.97 - 4.66%, respectively (Table 4).

Intra- and inter-day accuracy and precision of lixivaptan quality control samples determined for the investigated HPLC method.

| Conc. (ng mL-1) | Intra-day Mean | SD | RSD% | Accuracy % | Inter-day Mean | SD | RSD% | Accuracy % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 75.0 | 71.2 | 3.3 | 4.63 | 95.0 | 69.22 | 3.23 | 4.66 | 92.3 |

| 300 | 294.5 | 5.3 | 1.79 | 98.18 | 273.00 | 5.23 | 1.91 | 91.0 |

| 700.0 | 684.4 | 6.46 | 0.94 | 97.77 | 642.53 | 6.25 | 0.97 | 91.79 |

3.3.3 Stability

Drug stability was assessed under standard conditions. The concentrations calculated following the trials varied only within ±10%. During optimization, sample processing, or bench study, no degradation of lixivaptan was observed (Table 5). In addition, no loss of lixivaptan concentration was recorded for a relatively short period of time or during refrigeration. The newly developed procedure for the assay of lixivaptan can be performed under ordinary research facility conditions with a high degree of reproducibility without any recorded loss.

Stability of lixivaptan in mouse plasma based on the proposed HPLC method.

| Concentration (ng mL-1) | Mean | Recovery, % | RSD, % | RE, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Room Temp. for 8h | ||||

| 75 | 71.25 | 95 | 5.0 | -5% |

| 300 | 288 | 96 | 4.5 | -4% |

| 750 | 720 | 96 | 4.0 | -4% |

| Storage at -4° C ( | ||||

| 75 | 70.5 | 94 | 6 | -6% |

| 300 | 285 | 95 | 4.5 | -5% |

| 750 | 720 | 96 | 4.0 | -4% |

| Injector stability for 12h | ||||

| 75 | 71.25 | 95 | 5.0 | -5% |

| 300 | 288 | 96 | 4.9 | -4% |

| 750 | 720 | 94 | 4.5 | 6.0% |

3.4 Pharmacokinetic Study

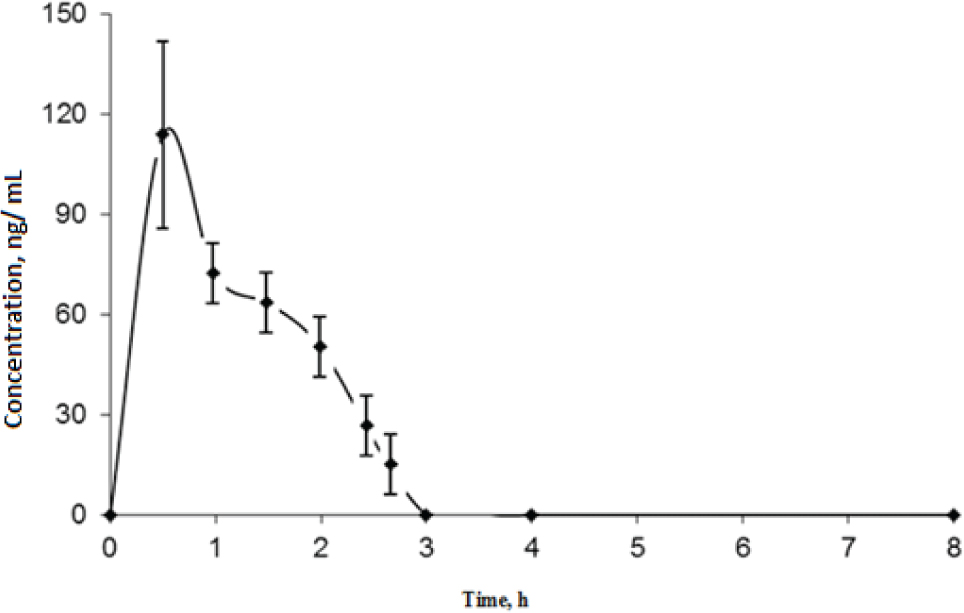

The investigated method was used to perform a preliminary pharmacokinetic study of lixivaptan in mouse plasma. The concentrations of lixivaptan in plasma samples at different time points after dosing were assessed individually. A plasma concentration time curve (AUC) of lixivaptan was plotted (Figure 4) using the lixivaptan concentration determined at each time point. Lixivaptan pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated from the concentration time curve. After oral administration of 10 mg Kg-1 lixivaptan, the mean values of the pharmacokinetic parameters Tmax and Cmax were determined to be 0.5 h and 113.82±28.1 ng mL-1, respectively. Determination of these parameters represents a demonstration of the utility of the developed method in pharmacokinetic research.

Concentration-time curve of lixivaptan in mouse plasma after oral administration of 10 mg kg-1 lixivaptan. Each point represents mean value ± SD.

4 Conclusion

In the current study, we investigated, for the earliest time, a simple, sensitive, and selective method for the determination of lixivaptan in mouse plasma samples using HPLC separation and UV detection. Acetonitrile was used as protein precipitation solvent for extracting lixivaptan from mouse plasma, and the method was validated using ICH guidelines. The method proved to be of acceptable accuracy, precision, recovery, selectivity, and sensitivity. The assay was further applied in a pharmacokinetic study of lixivaptan in mouse plasma, which shows the applicability of the method for use in clinical studies.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding the work through research group project no. RGP-1436-024.

References

[1] Ku E., Nobakht N., Campese V.M., Lixivaptan: a novel vasopressin receptor antagonist, Expert opinion on investigational drugs, 2009, 18, 657-662.10.1517/13543780902889760Search in Google Scholar

[2] Zmily H.D, Alani A., Ghali J.K, Evaluation of lixivaptan in euvolemic and hypervolemic hyponatremia and heart failure treatment, Expert opinion on drug metabolism & toxicology, 2013, 9, 645-655.10.1517/17425255.2013.783566Search in Google Scholar

[3] Liamis G., Filippatos T.D., Elisaf S., Treatment of hyponatremia: the role of lixivaptan, Expert review of clinical pharmacology, 2014, 7, 431-441.10.1586/17512433.2014.911085Search in Google Scholar

[4] Ring T., Lixivaptan and hyponatremia, Kidney international, 2013, 83, 1205-1206.10.1038/ki.2013.39Search in Google Scholar

[5] Bowman B.T., Rosner M.H., Lixivaptan–an evidence-based review of its clinical potential in the treatment of hyponatremia, Core evidence, 2013, 8, 47.10.2147/CE.S36744Search in Google Scholar

[6] O’Neil M.J., The Merck index: an encyclopedia of chemicals, drugs, and biologicals, RSC Publishing, 2013.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Rusinaru D., Tribouilloy C., Berry C., Richards A.M., Whalley G.A., Earle N., Poppe K.K., Guazzi M., Macin S.M., Komajda M., Relationship of serum sodium concentration to mortality in a wide spectrum of heart failure patients with preserved and with reduced ejection fraction: an individual patient data meta-analysis, European journal of heart failure, 2012, 10, 1139-1146.10.1093/eurjhf/hfs099Search in Google Scholar

[8] Muralidharan G., Meng X., DeCleene S., evallos W.C, Fruncillo Hicks D., Orczyk, G., Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of A Novel Vasopressin Receptor Antagonist, VPA-985, in Healthy Subjects, Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 1999, 65, 189-198.10.1016/S0009-9236(99)80286-0Search in Google Scholar

[9] Ellis-Grosse E., Meng X., Orczyk G., Single dose pharmacokinetic (PK)-pharmacodynamic (PD) profile of VPA-985, a novel, V2 receptor antagonist, in patients with congestive heart failure (CHF), AAPS Pharm. Sci., 1999, 1, S1.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Guyader D., Patat A., Ellis-Grosse E.J., Orczyk G., Pharmacodynamic effects of a nonpeptide antidiuretic hormone V2 antagonist in cirrhotic patients with ascites Hepatology, 2002, 36, 1197-1205.10.1053/jhep.2002.36375Search in Google Scholar

[11] Swan S., Lambvrecht L., Orczyk G., E. Ellis-Grosse E, Interaction between VPA-985, an ADH (V2) antagonist, and furosemide, J. Am. Soc. Nephrol., 1999, 10, 124A.Search in Google Scholar

[12] US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Bioanalytical Method Validation. US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research and Center for Veterinary Medicine: Rockville, MD, 2013.Search in Google Scholar

[13] González O., Blanco M.E., Iriarte G., Bartolomé L., Maguregui M.I., Alonso R.M., Bioanalytical chromatographic method validation according to current regulations, with a special focus on the non-well defined parameters limit of quantification, robustness and matrix effect, Journal of Chromatography A, 2014, 1353, 10-27.10.1016/j.chroma.2014.03.077Search in Google Scholar

[14] Shabir G., Validation of HPLC methods for pharmaceutical analysis: Understanding the differences and similarities between validation requirements of the US Food and Drug Administration, the US Pharmacopoeia and the International Conference on Harmonization, J. Chromatogr. A, 2003, 987, 57-66.10.1016/S0021-9673(02)01536-4Search in Google Scholar

[15] Health U.D.O., Services H., Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Center for Veterinary Medicine, Guidance for Industry, Bioanalytical Method Validation, 2001.Search in Google Scholar

[16] ICH I., In Harmonised Tripartite Guideline, Validation of Analytical Procedures: Test and Methodology, International conference on harmonisation of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use, 1996.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Ermer J., Miller J. H. M., Method validation in pharmaceutical analysis: A guide to best practice; John Wiley & Sons, 2006.10.1002/3527604685Search in Google Scholar

[18] Snyder L.R., Kirkland J.J., Glajch J.L., Practical HPLC method development, John Wiley & Sons, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Snyder, L. R., Kirkland, J. J., Dolan., J.W.; Introduction to modern liquid chromatography; John Wiley & Sons: 2011.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Kadi A.A., Alrabiah H., Attwa M.W., Attia S., Mostafa G.A.E., Development and validation of HPLC-MS/MS method for the determination of lixivaptan in mouse plasma and its application in a pharmacokinetic study, Biomedical Chromatography, 2017.10.1002/bmc.4007Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Bhat M.A., Al-Omar M.A., Ansari M.A., Zoheir K.M., Imam F., Attia S.M., Bakheet S.A., Nadeem A., Korashy H.M., Voronkov A., Berishvili V., Ahmad S.F., Design and Synthesis of N-Arylphthalimides as Inhibitors of Glucocorticoid-Induced TNF Receptor-Related Protein, Proinflammatory Mediators, and Cytokines in Carrageenan-Induced Lung Inflammation, J. Med Chem., 2015, 58 , 8850-67.10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00934Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Miller J.N., Miller J.C., Statistics and chemometrics for analytical chemistry, Pearson Education, 2005.Search in Google Scholar

© 2018 Haitham Alrabiah et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The effect of CuO modification for a TiO2 nanotube confined CeO2 catalyst on the catalytic combustion of butane

- The preparation and antibacterial activity of cellulose/ZnO composite: a review

- Linde Type A and nano magnetite/NaA zeolites: cytotoxicity and doxorubicin loading efficiency

- Performance and thermal decomposition analysis of foaming agent NPL-10 for use in heavy oil recovery by steam injection

- Spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, UV, 1H and 13C NMR) insights, electronic profiling and DFT computations on ({(E)-[3-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-1-phenylpropylidene] amino}oxy)(4-nitrophenyl)methanone, an imidazole-bearing anti-Candida agent

- A Simplistic Preliminary Assessment of Ginstling-Brounstein Model for Solid Spherical Particles in the Context of a Diffusion-Controlled Synthesis

- M-Polynomials And Topological Indices Of Zigzag And Rhombic Benzenoid Systems

- Photochemical Transformation of some 3-benzyloxy-2-(benzo[b]thiophen-2-yl)-4Hchromen-4-ones: A Remote Substituent Effect

- Dynamic Changes of Secondary Metabolites and Antioxidant Activity of Ligustrum lucidum During Fruit Growth

- Studies on the flammability of polypropylene/ammonium polyphosphate and montmorillonite by using the cone calorimeter test

- DSC, FT-IR, NIR, NIR-PCA and NIR-ANOVA for determination of chemical stability of diuretic drugs: impact of excipients

- Antioxidant and Hepatoprotective Effects of Methanolic Extracts of Zilla spinosa and Hammada elegans Against Carbon Tetrachlorideinduced Hepatotoxicity in Rats

- Prunus cerasifera Ehrh. fabricated ZnO nano falcates and its photocatalytic and dose dependent in vitro bio-activity

- Organic biocides hosted in layered double hydroxides: enhancing antimicrobial activity

- Experimental study on the regulation of the cholinergic pathway in renal macrophages by microRNA-132 to alleviate inflammatory response

- Synthesis, characterization, in-vitro antimicrobial properties, molecular docking and DFT studies of 3-{(E)-[(4,6-dimethylpyrimidin-2-yl)imino]methyl} naphthalen-2-ol and Heteroleptic Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Zn(II) complexes

- M-Polynomials and Topological Indices of Dominating David Derived Networks

- Human Health Risk Assessment of Trace Metals in Surface Water Due to Leachate from the Municipal Dumpsite by Pollution Index: A Case Study from Ndawuse River, Abuja, Nigeria

- Analysis of Bowel Diseases from Blood Serum by Autofluorescence and Atomic Force Microscopy Techniques

- Hydrographic parameters and distribution of dissolved Cu, Ni, Zn and nutrients near Jeddah desalination plant

- Relationships between diatoms and environmental variables in industrial water biotopes of Trzuskawica S.A. (Poland)

- Optimum Conversion of Major Ginsenoside Rb1 to Minor Ginsenoside Rg3(S) by Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Acid Hydrolysis Treatment

- Antioxidant, Anti-microbial Properties and Chemical Composition of Cumin Essential Oils Extracted by Three Methods

- Regulatory mechanism of ulinastatin on autophagy of macrophages and renal tubular epithelial cells

- Investigation of the sustained-release mechanism of hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose skeleton type Acipimox tablets

- Bio-accumulation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Grey Mangrove (Avicennia marina) along Arabian Gulf, Saudi Coast

- Dynamic Change of Secondary Metabolites and spectrum-effect relationship of Malus halliana Koehne flowers during blooming

- Lipids constituents from Gardenia aqualla Stapf & Hutch

- Effect of using microwaves for catalysts preparation on the catalytic acetalization of glycerol with furfural to obtain fuel additives

- Effect of Humic Acid on the Degradation of Methylene Blue by Peroxymonosulfate

- Serum containing drugs of Gua Lou Xie Bai decoction (GLXB-D) can inhibit TGF-β1-Induced Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in A549 Cells

- Antiulcer Activity of Different Extracts of Anvillea garcinii and Isolation of Two New Secondary Metabolites

- Analysis of Metabolites in Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz Dry Red Wines from Shanxi by 1H NMR Spectroscopy Combined with Pattern Recognition Analysis

- Can water temperature impact litter decomposition under pollution of copper and zinc mixture

- Released from ZrO2/SiO2 coating resveratrol inhibits senescence and oxidative stress of human adipose-derived stem cells (ASC)

- Validated thin-layer chromatographic method for alternative and simultaneous determination of two anti-gout agents in their fixed dose combinations

- Fast removal of pollutants from vehicle emissions during cold-start stage

- Review Article

- Catalytic activities of heterogeneous catalysts obtained by copolymerization of metal-containing 2-(acetoacetoxy)ethyl methacrylate

- Antibiotic Residue in the Aquatic Environment: Status in Africa

- Regular Articles

- Mercury fractionation in gypsum using temperature desorption and mass spectrometric detection

- Phytosynthetic Ag doped ZnO nanoparticles: Semiconducting green remediators

- Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Induced by SMAD4 Activation in Invasive Growth Hormone-Secreting Adenomas

- Physicochemical properties of stabilized sewage sludge admixtures by modified steel slag

- In Vitro Cytotoxic and Antiproliferative Activity of Cydonia oblonga flower petals, leaf and fruit pellet ethanolic extracts. Docking simulation of the active flavonoids on anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2

- Synthesis and Characterization of Pd exchanged MMT Clay for Mizoroki-Heck Reaction

- A new selective, and sensitive method for the determination of lixivaptan, a vasopressin 2 (V2)-receptor antagonist, in mouse plasma and its application in a pharmacokinetic study

- Anti-EGFL7 antibodies inhibit rat prolactinoma MMQ cells proliferation and PRL secretion

- Density functional theory calculations, vibration spectral analysis and molecular docking of the antimicrobial agent 6-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-ylmethyl)-5-ethyl-2-{[2-(morpholin-4-yl)ethyl] sulfanyl}pyrimidin-4(3H)-one

- Effect of Nano Zeolite on the Transformation of Cadmium Speciation and Its Uptake by Tobacco in Cadmium-contaminated Soil

- Effects and Mechanisms of Jinniu Capsule on Methamphetamine-Induced Conditioned Place Preference in Rats

- Calculating the Degree-based Topological Indices of Dendrimers

- Efficient optimization and mineralization of UV absorbers: A comparative investigation with Fenton and UV/H2O2

- Metabolites of Tryptophane and Phenylalanine as Markers of Small Bowel Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

- Adsorption and determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water through the aggregation of graphene oxide

- The role of NR2C2 in the prolactinomas

- Chromium removal from industrial wastewater using Phyllostachys pubescens biomass loaded Cu-S nanospheres

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Preparation of Calcium Fluoride using Phosphogypsum by Orthogonal Experiment

- The mechanism of antibacterial activity of corylifolinin against three clinical bacteria from Psoralen corylifolia L

- 2-formyl-3,6-bis(hydroxymethyl)phenyl benzoate in Electrochemical Dry Cell

- Electro-photocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin using calcium titanate

- Effect of Malus halliana Koehne Polysaccharides on Functional Constipation

- Structural Properties and Nonlinear Optical Responses of Halogenated Compounds: A DFT Investigation on Molecular Modelling

- DMFDMA catalyzed synthesis of 2-((Dimethylamino)methylene)-3,4-dihydro-9-arylacridin-1(2H)-ones and their derivatives: in-vitro antifungal, antibacterial and antioxidant evaluations

- Production of Methanol as a Fuel Energy from CO2 Present in Polluted Seawater - A Photocatalytic Outlook

- Study of different extraction methods on finger print and fatty acid of raw beef fat using fourier transform infrared and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- Determination of trace fluoroquinolones in water solutions and in medicinal preparations by conventional and synchronous fluorescence spectrometry

- Extraction and determination of flavonoids in Carthamus tinctorius

- Therapeutic Application of Zinc and Vanadium Complexes against Diabetes Mellitus a Coronary Disease: A review

- Study of calcined eggshell as potential catalyst for biodiesel formation using used cooking oil

- Manganese oxalates - structure-based Insights

- Topological Indices of H-Naphtalenic Nanosheet

- Long-Term Dissolution of Glass Fibers in Water Described by Dissolving Cylinder Zero-Order Kinetic Model: Mass Loss and Radius Reduction

- Topological study of the para-line graphs of certain pentacene via topological indices

- A brief insight into the prediction of water vapor transmissibility in highly impermeable hybrid nanocomposites based on bromobutyl/epichlorohydrin rubber blends

- Comparative sulfite assay by voltammetry using Pt electrodes, photometry and titrimetry: Application to cider, vinegar and sugar analysis

- MicroRNA delivery mediated by PEGylated polyethylenimine for prostate cancer therapy

- Reversible Fluorescent Turn-on Sensors for Fe3+ based on a Receptor Composed of Tri-oxygen Atoms of Amide Groups in Water

- Sonocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in aqueous solution using Fe-doped TiO2 nanoparticles under mechanical agitation

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Production and Analysis of Recycled Ammonium Perrhenate from CMSX-4 superalloys

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- New phosphorus biofertilizers from renewable raw materials in the aspect of cadmium and lead contents in soil and plants

- Survey of content of cadmium, calcium, chromium, copper, iron, lead, magnesium, manganese, mercury, sodium and zinc in chamomile and green tea leaves by electrothermal or flame atomizer atomic absorption spectrometry

- Biogas digestate – benefits and risks for soil fertility and crop quality – an evaluation of grain maize response

- A numerical analysis of heat transfer in a cross-current heat exchanger with controlled and newly designed air flows

- Freshwater green macroalgae as a biosorbent of Cr(III) ions

- The main influencing factors of soil mechanical characteristics of the gravity erosion environment in the dry-hot valley of Jinsha river

- Free amino acids in Viola tricolor in relation to different habitat conditions

- The influence of filler amount on selected properties of new experimental resin dental composite

- Effect of poultry wastewater irrigation on nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon contents in farmland soil

- Response of spring wheat to NPK and S fertilization. The content and uptake of macronutrients and the value of ionic ratios

- The Effect of Macroalgal Extracts and Near Infrared Radiation on Germination of Soybean Seedlings: Preliminary Research Results

- Content of Zn, Cd and Pb in purple moor-grass in soils heavily contaminated with heavy metals around a zinc and lead ore tailing landfill

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Synthesis of (±)-3,4-dimethoxybenzyl-4-methyloctanoate as a novel internal standard for capsinoid determination by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS(QTOF)

- Repellent activity of monoterpenoid esters with neurotransmitter amino acids against yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti

- Effect of Flammulina velutipes (golden needle mushroom, eno-kitake) polysaccharides on constipation

- Bioassay-directed fractionation of a blood coagulation factor Xa inhibitor, betulinic acid from Lycopus lucidus

- Antifungal and repellent activities of the essential oils from three aromatic herbs from western Himalaya

- Chemical composition and microbiological evaluation of essential oil from Hyssopus officinalis L. with white and pink flowers

- Bioassay-guided isolation and identification of Aedes aegypti larvicidal and biting deterrent compounds from Veratrum lobelianum

- α-Terpineol, a natural monoterpene: A review of its biological properties

- Utility of essential oils for development of host-based lures for Xyleborus glabratus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae), vector of laurel wilt

- Phenolic composition and antioxidant potential of different organs of Kazakh Crataegus almaatensis Pojark: A comparison with the European Crataegus oxyacantha L. flowers

- Isolation of eudesmane type sesquiterpene ketone from Prangos heyniae H.Duman & M.F.Watson essential oil and mosquitocidal activity of the essential oils

- Comparative analysis of the polyphenols profiles and the antioxidant and cytotoxicity properties of various blue honeysuckle varieties

- Special Issue on ICCESEN 2017

- Modelling world energy security data from multinomial distribution by generalized linear model under different cumulative link functions

- Pine Cone and Boron Compounds Effect as Reinforcement on Mechanical and Flammability Properties of Polyester Composites

- Artificial Neural Network Modelling for Prediction of SNR Effected by Probe Properties on Ultrasonic Inspection of Austenitic Stainless Steel Weldments

- Calculation and 3D analyses of ERR in the band crack front contained in a rectangular plate made of multilayered material

- Improvement of fuel properties of biodiesel with bioadditive ethyl levulinate

- Properties of AlSi9Cu3 metal matrix micro and nano composites produced via stir casting

- Investigation of Antibacterial Properties of Ag Doped TiO2 Nanofibers Prepared by Electrospinning Process

- Modeling of Total Phenolic contents in Various Tea samples by Experimental Design Methods

- Nickel doping effect on the structural and optical properties of indium sulfide thin films by SILAR

- The effect mechanism of Ginnalin A as a homeopathic agent on various cancer cell lines

- Excitation functions of proton induced reactions of some radioisotopes used in medicine

- Oxide ionic conductivity and microstructures of Pr and Sm co-doped CeO2-based systems

- Rapid Synthesis of Metallic Reinforced in Situ Intermetallic Composites in Ti-Al-Nb System via Resistive Sintering

- Oxidation Behavior of NiCr/YSZ Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs)

- Clustering Analysis of Normal Strength Concretes Produced with Different Aggregate Types

- Magnetic Nano-Sized Solid Acid Catalyst Bearing Sulfonic Acid Groups for Biodiesel Synthesis

- The biological activities of Arabis alpina L. subsp. brevifolia (DC.) Cullen against food pathogens

- Humidity properties of Schiff base polymers

- Free Vibration Analysis of Fiber Metal Laminated Straight Beam

- Comparative study of in vitro antioxidant, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase activity of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) collected during different growth stages

- Isothermal Oxidation Behavior of Gadolinium Zirconate (Gd2Zr2O7) Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs) produced by Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition (EB-PVD) technique

- Optimization of Adsorption Parameters for Ultra-Fine Calcite Using a Box-Behnken Experimental Design

- The Microstructural Investigation of Vermiculite-Infiltrated Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition Thermal Barrier Coatings

- Modelling Porosity Permeability of Ceramic Tiles using Fuzzy Taguchi Method

- Experimental and theoretical study of a novel naphthoquinone Schiff base

- Physicochemical properties of heat treated sille stone for ceramic industry

- Sand Dune Characterization for Preparing Metallurgical Grade Silicon

- Catalytic Applications of Large Pore Sulfonic Acid-Functionalized SBA-15 Mesoporous Silica for Esterification

- One-photon Absorption Characterizations, Dipole Polarizabilities and Second Hyperpolarizabilities of Chlorophyll a and Crocin

- The Optical and Crystallite Characterization of Bilayer TiO2 Films Coated on Different ITO layers

- Topical Issue on Bond Activation

- Metal-mediated reactions towards the synthesis of a novel deaminolysed bisurea, dicarbamolyamine

- The structure of ortho-(trifluoromethyl)phenol in comparison to its homologues – A combined experimental and theoretical study

- Heterogeneous catalysis with encapsulated haem and other synthetic porphyrins: Harnessing the power of porphyrins for oxidation reactions

- Recent Advances on Mechanistic Studies on C–H Activation Catalyzed by Base Metals

- Reactions of the organoplatinum complex [Pt(cod) (neoSi)Cl] (neoSi = trimethylsilylmethyl) with the non-coordinating anions SbF6– and BPh4–

- Erratum

- Investigation on Two Compounds of O, O’-dithiophosphate Derivatives as Corrosion Inhibitors for Q235 Steel in Hydrochloric Acid Solution

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The effect of CuO modification for a TiO2 nanotube confined CeO2 catalyst on the catalytic combustion of butane

- The preparation and antibacterial activity of cellulose/ZnO composite: a review

- Linde Type A and nano magnetite/NaA zeolites: cytotoxicity and doxorubicin loading efficiency

- Performance and thermal decomposition analysis of foaming agent NPL-10 for use in heavy oil recovery by steam injection

- Spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, UV, 1H and 13C NMR) insights, electronic profiling and DFT computations on ({(E)-[3-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-1-phenylpropylidene] amino}oxy)(4-nitrophenyl)methanone, an imidazole-bearing anti-Candida agent

- A Simplistic Preliminary Assessment of Ginstling-Brounstein Model for Solid Spherical Particles in the Context of a Diffusion-Controlled Synthesis

- M-Polynomials And Topological Indices Of Zigzag And Rhombic Benzenoid Systems

- Photochemical Transformation of some 3-benzyloxy-2-(benzo[b]thiophen-2-yl)-4Hchromen-4-ones: A Remote Substituent Effect

- Dynamic Changes of Secondary Metabolites and Antioxidant Activity of Ligustrum lucidum During Fruit Growth

- Studies on the flammability of polypropylene/ammonium polyphosphate and montmorillonite by using the cone calorimeter test

- DSC, FT-IR, NIR, NIR-PCA and NIR-ANOVA for determination of chemical stability of diuretic drugs: impact of excipients

- Antioxidant and Hepatoprotective Effects of Methanolic Extracts of Zilla spinosa and Hammada elegans Against Carbon Tetrachlorideinduced Hepatotoxicity in Rats

- Prunus cerasifera Ehrh. fabricated ZnO nano falcates and its photocatalytic and dose dependent in vitro bio-activity

- Organic biocides hosted in layered double hydroxides: enhancing antimicrobial activity

- Experimental study on the regulation of the cholinergic pathway in renal macrophages by microRNA-132 to alleviate inflammatory response

- Synthesis, characterization, in-vitro antimicrobial properties, molecular docking and DFT studies of 3-{(E)-[(4,6-dimethylpyrimidin-2-yl)imino]methyl} naphthalen-2-ol and Heteroleptic Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Zn(II) complexes

- M-Polynomials and Topological Indices of Dominating David Derived Networks

- Human Health Risk Assessment of Trace Metals in Surface Water Due to Leachate from the Municipal Dumpsite by Pollution Index: A Case Study from Ndawuse River, Abuja, Nigeria

- Analysis of Bowel Diseases from Blood Serum by Autofluorescence and Atomic Force Microscopy Techniques

- Hydrographic parameters and distribution of dissolved Cu, Ni, Zn and nutrients near Jeddah desalination plant

- Relationships between diatoms and environmental variables in industrial water biotopes of Trzuskawica S.A. (Poland)

- Optimum Conversion of Major Ginsenoside Rb1 to Minor Ginsenoside Rg3(S) by Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Acid Hydrolysis Treatment

- Antioxidant, Anti-microbial Properties and Chemical Composition of Cumin Essential Oils Extracted by Three Methods

- Regulatory mechanism of ulinastatin on autophagy of macrophages and renal tubular epithelial cells

- Investigation of the sustained-release mechanism of hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose skeleton type Acipimox tablets

- Bio-accumulation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Grey Mangrove (Avicennia marina) along Arabian Gulf, Saudi Coast

- Dynamic Change of Secondary Metabolites and spectrum-effect relationship of Malus halliana Koehne flowers during blooming

- Lipids constituents from Gardenia aqualla Stapf & Hutch

- Effect of using microwaves for catalysts preparation on the catalytic acetalization of glycerol with furfural to obtain fuel additives

- Effect of Humic Acid on the Degradation of Methylene Blue by Peroxymonosulfate

- Serum containing drugs of Gua Lou Xie Bai decoction (GLXB-D) can inhibit TGF-β1-Induced Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in A549 Cells

- Antiulcer Activity of Different Extracts of Anvillea garcinii and Isolation of Two New Secondary Metabolites

- Analysis of Metabolites in Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz Dry Red Wines from Shanxi by 1H NMR Spectroscopy Combined with Pattern Recognition Analysis

- Can water temperature impact litter decomposition under pollution of copper and zinc mixture

- Released from ZrO2/SiO2 coating resveratrol inhibits senescence and oxidative stress of human adipose-derived stem cells (ASC)

- Validated thin-layer chromatographic method for alternative and simultaneous determination of two anti-gout agents in their fixed dose combinations

- Fast removal of pollutants from vehicle emissions during cold-start stage

- Review Article

- Catalytic activities of heterogeneous catalysts obtained by copolymerization of metal-containing 2-(acetoacetoxy)ethyl methacrylate

- Antibiotic Residue in the Aquatic Environment: Status in Africa

- Regular Articles

- Mercury fractionation in gypsum using temperature desorption and mass spectrometric detection

- Phytosynthetic Ag doped ZnO nanoparticles: Semiconducting green remediators

- Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Induced by SMAD4 Activation in Invasive Growth Hormone-Secreting Adenomas

- Physicochemical properties of stabilized sewage sludge admixtures by modified steel slag

- In Vitro Cytotoxic and Antiproliferative Activity of Cydonia oblonga flower petals, leaf and fruit pellet ethanolic extracts. Docking simulation of the active flavonoids on anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2

- Synthesis and Characterization of Pd exchanged MMT Clay for Mizoroki-Heck Reaction

- A new selective, and sensitive method for the determination of lixivaptan, a vasopressin 2 (V2)-receptor antagonist, in mouse plasma and its application in a pharmacokinetic study

- Anti-EGFL7 antibodies inhibit rat prolactinoma MMQ cells proliferation and PRL secretion

- Density functional theory calculations, vibration spectral analysis and molecular docking of the antimicrobial agent 6-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-ylmethyl)-5-ethyl-2-{[2-(morpholin-4-yl)ethyl] sulfanyl}pyrimidin-4(3H)-one

- Effect of Nano Zeolite on the Transformation of Cadmium Speciation and Its Uptake by Tobacco in Cadmium-contaminated Soil

- Effects and Mechanisms of Jinniu Capsule on Methamphetamine-Induced Conditioned Place Preference in Rats

- Calculating the Degree-based Topological Indices of Dendrimers

- Efficient optimization and mineralization of UV absorbers: A comparative investigation with Fenton and UV/H2O2

- Metabolites of Tryptophane and Phenylalanine as Markers of Small Bowel Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

- Adsorption and determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water through the aggregation of graphene oxide

- The role of NR2C2 in the prolactinomas

- Chromium removal from industrial wastewater using Phyllostachys pubescens biomass loaded Cu-S nanospheres

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Preparation of Calcium Fluoride using Phosphogypsum by Orthogonal Experiment

- The mechanism of antibacterial activity of corylifolinin against three clinical bacteria from Psoralen corylifolia L

- 2-formyl-3,6-bis(hydroxymethyl)phenyl benzoate in Electrochemical Dry Cell

- Electro-photocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin using calcium titanate

- Effect of Malus halliana Koehne Polysaccharides on Functional Constipation

- Structural Properties and Nonlinear Optical Responses of Halogenated Compounds: A DFT Investigation on Molecular Modelling

- DMFDMA catalyzed synthesis of 2-((Dimethylamino)methylene)-3,4-dihydro-9-arylacridin-1(2H)-ones and their derivatives: in-vitro antifungal, antibacterial and antioxidant evaluations

- Production of Methanol as a Fuel Energy from CO2 Present in Polluted Seawater - A Photocatalytic Outlook

- Study of different extraction methods on finger print and fatty acid of raw beef fat using fourier transform infrared and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- Determination of trace fluoroquinolones in water solutions and in medicinal preparations by conventional and synchronous fluorescence spectrometry

- Extraction and determination of flavonoids in Carthamus tinctorius

- Therapeutic Application of Zinc and Vanadium Complexes against Diabetes Mellitus a Coronary Disease: A review

- Study of calcined eggshell as potential catalyst for biodiesel formation using used cooking oil

- Manganese oxalates - structure-based Insights

- Topological Indices of H-Naphtalenic Nanosheet

- Long-Term Dissolution of Glass Fibers in Water Described by Dissolving Cylinder Zero-Order Kinetic Model: Mass Loss and Radius Reduction

- Topological study of the para-line graphs of certain pentacene via topological indices

- A brief insight into the prediction of water vapor transmissibility in highly impermeable hybrid nanocomposites based on bromobutyl/epichlorohydrin rubber blends

- Comparative sulfite assay by voltammetry using Pt electrodes, photometry and titrimetry: Application to cider, vinegar and sugar analysis

- MicroRNA delivery mediated by PEGylated polyethylenimine for prostate cancer therapy

- Reversible Fluorescent Turn-on Sensors for Fe3+ based on a Receptor Composed of Tri-oxygen Atoms of Amide Groups in Water

- Sonocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in aqueous solution using Fe-doped TiO2 nanoparticles under mechanical agitation

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Production and Analysis of Recycled Ammonium Perrhenate from CMSX-4 superalloys

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- New phosphorus biofertilizers from renewable raw materials in the aspect of cadmium and lead contents in soil and plants

- Survey of content of cadmium, calcium, chromium, copper, iron, lead, magnesium, manganese, mercury, sodium and zinc in chamomile and green tea leaves by electrothermal or flame atomizer atomic absorption spectrometry

- Biogas digestate – benefits and risks for soil fertility and crop quality – an evaluation of grain maize response

- A numerical analysis of heat transfer in a cross-current heat exchanger with controlled and newly designed air flows

- Freshwater green macroalgae as a biosorbent of Cr(III) ions

- The main influencing factors of soil mechanical characteristics of the gravity erosion environment in the dry-hot valley of Jinsha river

- Free amino acids in Viola tricolor in relation to different habitat conditions

- The influence of filler amount on selected properties of new experimental resin dental composite

- Effect of poultry wastewater irrigation on nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon contents in farmland soil

- Response of spring wheat to NPK and S fertilization. The content and uptake of macronutrients and the value of ionic ratios

- The Effect of Macroalgal Extracts and Near Infrared Radiation on Germination of Soybean Seedlings: Preliminary Research Results

- Content of Zn, Cd and Pb in purple moor-grass in soils heavily contaminated with heavy metals around a zinc and lead ore tailing landfill

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Synthesis of (±)-3,4-dimethoxybenzyl-4-methyloctanoate as a novel internal standard for capsinoid determination by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS(QTOF)

- Repellent activity of monoterpenoid esters with neurotransmitter amino acids against yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti

- Effect of Flammulina velutipes (golden needle mushroom, eno-kitake) polysaccharides on constipation

- Bioassay-directed fractionation of a blood coagulation factor Xa inhibitor, betulinic acid from Lycopus lucidus

- Antifungal and repellent activities of the essential oils from three aromatic herbs from western Himalaya

- Chemical composition and microbiological evaluation of essential oil from Hyssopus officinalis L. with white and pink flowers

- Bioassay-guided isolation and identification of Aedes aegypti larvicidal and biting deterrent compounds from Veratrum lobelianum

- α-Terpineol, a natural monoterpene: A review of its biological properties

- Utility of essential oils for development of host-based lures for Xyleborus glabratus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae), vector of laurel wilt

- Phenolic composition and antioxidant potential of different organs of Kazakh Crataegus almaatensis Pojark: A comparison with the European Crataegus oxyacantha L. flowers

- Isolation of eudesmane type sesquiterpene ketone from Prangos heyniae H.Duman & M.F.Watson essential oil and mosquitocidal activity of the essential oils

- Comparative analysis of the polyphenols profiles and the antioxidant and cytotoxicity properties of various blue honeysuckle varieties

- Special Issue on ICCESEN 2017

- Modelling world energy security data from multinomial distribution by generalized linear model under different cumulative link functions

- Pine Cone and Boron Compounds Effect as Reinforcement on Mechanical and Flammability Properties of Polyester Composites

- Artificial Neural Network Modelling for Prediction of SNR Effected by Probe Properties on Ultrasonic Inspection of Austenitic Stainless Steel Weldments

- Calculation and 3D analyses of ERR in the band crack front contained in a rectangular plate made of multilayered material

- Improvement of fuel properties of biodiesel with bioadditive ethyl levulinate

- Properties of AlSi9Cu3 metal matrix micro and nano composites produced via stir casting

- Investigation of Antibacterial Properties of Ag Doped TiO2 Nanofibers Prepared by Electrospinning Process

- Modeling of Total Phenolic contents in Various Tea samples by Experimental Design Methods

- Nickel doping effect on the structural and optical properties of indium sulfide thin films by SILAR

- The effect mechanism of Ginnalin A as a homeopathic agent on various cancer cell lines

- Excitation functions of proton induced reactions of some radioisotopes used in medicine

- Oxide ionic conductivity and microstructures of Pr and Sm co-doped CeO2-based systems

- Rapid Synthesis of Metallic Reinforced in Situ Intermetallic Composites in Ti-Al-Nb System via Resistive Sintering

- Oxidation Behavior of NiCr/YSZ Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs)

- Clustering Analysis of Normal Strength Concretes Produced with Different Aggregate Types

- Magnetic Nano-Sized Solid Acid Catalyst Bearing Sulfonic Acid Groups for Biodiesel Synthesis

- The biological activities of Arabis alpina L. subsp. brevifolia (DC.) Cullen against food pathogens

- Humidity properties of Schiff base polymers

- Free Vibration Analysis of Fiber Metal Laminated Straight Beam

- Comparative study of in vitro antioxidant, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase activity of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) collected during different growth stages

- Isothermal Oxidation Behavior of Gadolinium Zirconate (Gd2Zr2O7) Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs) produced by Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition (EB-PVD) technique

- Optimization of Adsorption Parameters for Ultra-Fine Calcite Using a Box-Behnken Experimental Design

- The Microstructural Investigation of Vermiculite-Infiltrated Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition Thermal Barrier Coatings

- Modelling Porosity Permeability of Ceramic Tiles using Fuzzy Taguchi Method

- Experimental and theoretical study of a novel naphthoquinone Schiff base

- Physicochemical properties of heat treated sille stone for ceramic industry

- Sand Dune Characterization for Preparing Metallurgical Grade Silicon

- Catalytic Applications of Large Pore Sulfonic Acid-Functionalized SBA-15 Mesoporous Silica for Esterification

- One-photon Absorption Characterizations, Dipole Polarizabilities and Second Hyperpolarizabilities of Chlorophyll a and Crocin

- The Optical and Crystallite Characterization of Bilayer TiO2 Films Coated on Different ITO layers

- Topical Issue on Bond Activation

- Metal-mediated reactions towards the synthesis of a novel deaminolysed bisurea, dicarbamolyamine

- The structure of ortho-(trifluoromethyl)phenol in comparison to its homologues – A combined experimental and theoretical study

- Heterogeneous catalysis with encapsulated haem and other synthetic porphyrins: Harnessing the power of porphyrins for oxidation reactions

- Recent Advances on Mechanistic Studies on C–H Activation Catalyzed by Base Metals

- Reactions of the organoplatinum complex [Pt(cod) (neoSi)Cl] (neoSi = trimethylsilylmethyl) with the non-coordinating anions SbF6– and BPh4–

- Erratum

- Investigation on Two Compounds of O, O’-dithiophosphate Derivatives as Corrosion Inhibitors for Q235 Steel in Hydrochloric Acid Solution