Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

Abstract

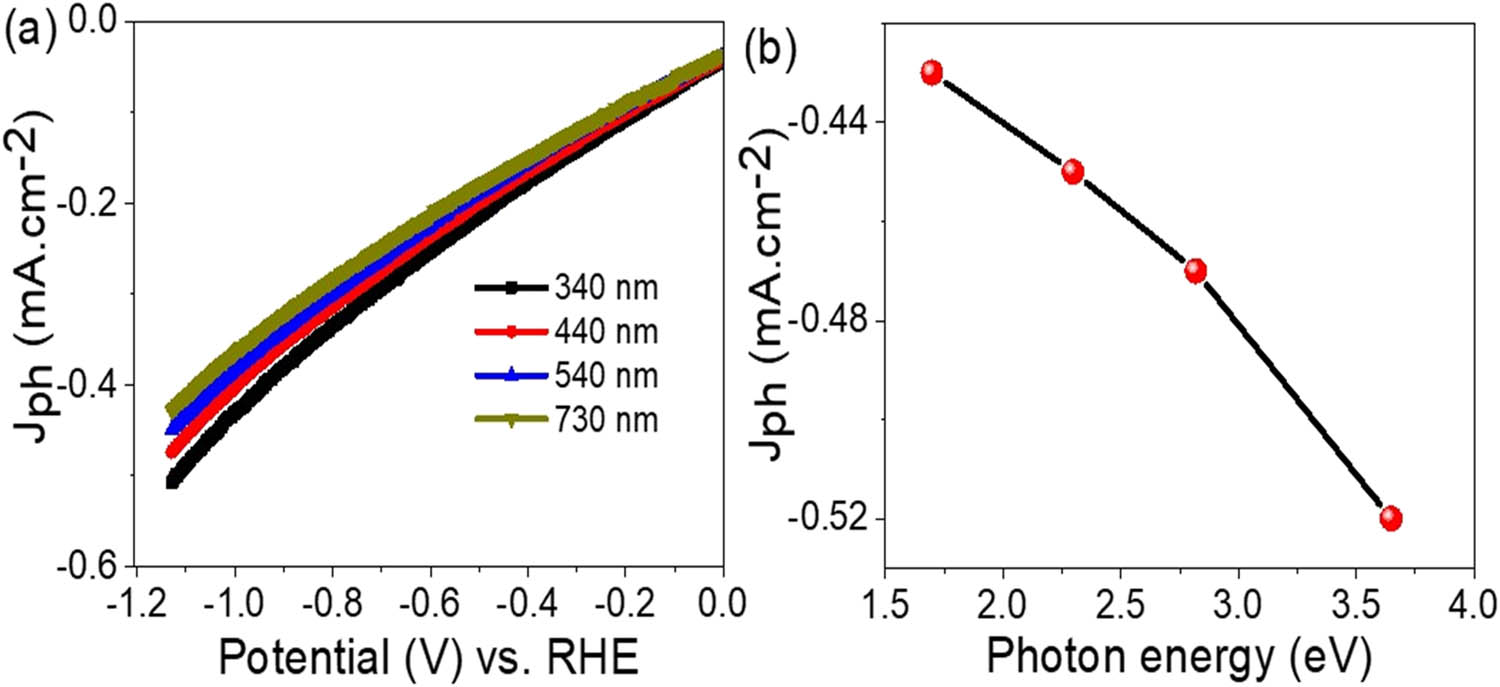

This research focuses on converting Red Sea seawater into environmentally friendly hydrogen (H2) gas by developing an innovative photocathode termed MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB. Fabricated through a single-step process, this photocathode demonstrates impressive performance, achieving an H2 production rate of 6.0 µmol/10 cm²·h with a current density (J ph) of −0.7 mA·cm⁻². The effectiveness of this photocathode is highlighted by its favorable morphological properties, characterized by semi-spherical shapes measuring 130 nm in width and 170 nm in length. Moreover, the MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB photocathode exhibits excellent light absorbance across a wide spectrum, benefiting from a small bandgap of 1.6 eV, which significantly enhances its efficiency in converting light energy into hydrogen gas. The photocathode’s performance is rigorously tested under various optical conditions, with photon energies ranging from 3.6 to 1.7 eV. As the photon energies decrease from 3.6 to 1.7 eV, the J ph values decrease from −0.53 to −0.43 mA·cm⁻², demonstrating the photocathode’s adaptability to different optical environments. Overall, the successful synthesis of the MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB photocathode marks a significant advancement in H2 gas production directly from seawater. This technology shows potential for commercial applications, particularly in remote and economically disadvantaged areas where access to conventional energy sources is limited, offering a promising solution for sustainable energy generation.

1 Introduction

Transitioning toward renewable energy sources, either alongside or in lieu of fossil fuels, presents a primary challenge for scientists worldwide. This challenge stems from the diverse techniques required to facilitate reactions for harnessing renewable energy [1,2,3]. Moreover, fossil fuels are plagued by the production of harmful byproducts, rendering them hazardous as an energy source. In recent years, dichalcogenide and trichalcogenide materials have garnered attention as promising photocatalysts for H2 gas generation [4,5]. This interest is attributed to their ability to efficiently absorb photons and generate hot electrons, which play a pivotal role in initiating the water-splitting reaction. These chalcogenide materials exhibit enhanced performance in H2 gas generation when their morphologies are optimized through the preparation of nanomaterials with favorable optical properties. By refining the morphological characteristics at the nanoscale, these materials can maximize their surface area-to-volume ratio, thereby increasing their catalytic activity and efficiency in light absorption. Furthermore, the incorporation of chalcogenides with additional oxide materials enhances their light absorption capacity and stability, leading to improved overall performance in H2 gas generation. These oxide materials exhibit complementary properties, such as enhanced light absorbance and structural stability, which synergistically amplify the photocatalytic activity of the chalcogenides [6,7].

By combining chalcogenides with oxide materials, researchers can create composite materials with superior light absorption capabilities, thereby increasing the efficiency of H2 gas production. This synergistic approach not only maximizes the utilization of incident light but also enhances the stability and durability of the photocatalyst, resulting in a more sustainable and efficient process for renewable H2 gas generation. Certain scientists are exploring the integration of chalcogenide materials within polymer matrices characterized by exceptional optical absorbance. This strategy involves embedding chalcogenides within polymers to serve as both a protective barrier and a facilitator of their photocatalytic behavior. Among these polymers, thiophene derivatives stand out as particularly promising candidates due to their high light absorption properties and remarkable ability to mitigate corrosion [8,9]. Thiophene derivatives exhibit exceptional optical absorbance characteristics, making them ideal candidates for encapsulating chalcogenide materials. By incorporating chalcogenides within thiophene-based polymers, researchers aim to create a protective environment that shields the chalcogenides from environmental degradation while simultaneously enhancing their photocatalytic activity. One of the key advantages of using thiophene derivatives as encapsulating materials is their ability to absorb a broad range of light wavelengths. This property ensures efficient utilization of incident light, thereby promoting effective photocatalysis. Additionally, thiophene-based polymers offer excellent protection against corrosion, safeguarding the embedded chalcogenide materials from degradation caused by exposure to harsh environmental conditions. The incorporation of chalcogenides within thiophene-based polymers also enables synergistic interactions between the two components. The polymer matrix provides structural support to the chalcogenides, enhancing their stability and durability during photocatalytic reactions. Furthermore, the polymer represents a barrier for preventing the leaching of chalcogenide particles into the surrounding environment and facilitating their controlled release [10,11]. Moreover, thiophene derivatives possess inherent chemical stability, ensuring the long-term integrity of the composite material. This stability is crucial for maintaining the efficiency and functionality of the photocatalytic system over extended periods of time.

A significant limitation observed in previous studies is the relatively low current density (J ph) values associated with H2 production, indicating a correspondingly low rate of H2 generation. Additionally, the widespread use of corrosive media such as NaOH, Na2SO4, NaBH4, and H2SO4 as sacrificial agents exacerbates electrode corrosion [12,13]. While these materials do contain hydrogen, they also have adverse effects on the electrodes by promoting corrosion. Furthermore, their corrosive nature and associated costs pose significant challenges to the commercial application of H2 gas in industrial settings.

One notable drawback identified in the literature is the limited efficiency in H2 generation, as evidenced by the low current density values recorded. These values serve as a crucial indicator of the H2 gas rate. However, the observed values suggest that the H2 generation rate achieved in previous studies is relatively modest. This limitation highlights the need for improved methodologies and materials for efficient H2 production process enhancements [14]. Furthermore, the use of corrosive media such as NaOH, Na2SO4, NaBH4, and H2SO4 as sacrificial agents exacerbates the issue of electrode corrosion. While these materials contain hydrogen and play a role in facilitating H2 generation, they also have adverse effects on the electrodes. Specifically, these corrosive agents can lead to the degradation of electrode materials over time, compromising their performance and longevity. The corrosive nature of these mediums poses significant challenges in maintaining the integrity and functionality of electrodes used in H2 production systems. Moreover, the use of these corrosive media introduces additional costs and complexities to the H2 production process. Not only are these materials expensive to procure, but they also require careful handling and disposal procedures to mitigate environmental and safety risks. The increased cost associated with acquiring and managing these corrosive agents further impedes the commercial viability of H2 gas production on an industrial scale. Additionally, the cohesive effect of these corrosive media on the electrodes exacerbates the issue of electrode corrosion. This cohesion hampers the performance of the electrodes, limiting their efficiency in catalyzing H2 generation reactions. As a result, the overall effectiveness of H2 production processes is compromised, further highlighting the need for alternative approaches that minimize electrode corrosion and improve H2 generation efficiency [15].

In this research, a novel photocathode named MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB is developed through a single-step fabrication process. This photocathode exhibits promising performance in generating hydrogen gas using Red Sea water as a promising eco-friendly electrolyte source, highlighting its effectiveness as a photocatalyst. The noteworthy success of this photocathode is attributed to its favorable optical properties and small bandgap, which enable efficient light absorption. Furthermore, the photocathode is subjected to testing across a wide range of light photons with energies ranging from 3.6 to 1.7 eV. The rate of H2 gas production aligns with this optical spectrum, indicating the photocathode’s sensitivity to light energy. The successful synthesis of the MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB photocathode represents a breakthrough in the field, opening the door to potential commercial applications, especially for the direct conversion of seawater into H2 gas. This technology holds significant promise for use in various environments, including remote locations and economically disadvantaged areas where access to conventional energy sources is limited.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Sodium molybdate (Na2MoO4, 99.9%) and 1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene (99.9%) are sourced from Pio-chem (Egypt) and Merck (Berlin), respectively. Meanwhile, HCl (36%) is provided by Merck Co. (Germany). Additionally, potassium persulfate (K2S2O8, 99.8%) is acquired from El-Nasr Chemical Company (Egypt).

2.2 One-pot synthesis of MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB nanocomposite thin film

The synthesis of MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB is achieved through a one-pot reaction, where 0.06 M 1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene is directly polymerized using the oxidant K2S2O8 in the presence of 0.07 M Na2MoO4. This reaction ensures complete polymerization, leading to the precipitation of the polymer, which forms a film on a glass substrate placed in the reaction solution during oxidation. The monomer-to-oxidant ratio is precisely maintained at 1:2.2, and the monomer-to-HCl ratio is carefully adjusted to 1:15. The reaction is carried out at room temperature and lasts for 2 days. In contrast, the preparation of PA2MB as a pristine polymer is conducted under the same conditions but without the addition of Na2MoO4.

Upon the conclusion of the reaction, chloride ions (Cl−) emerge as significant residues that intricately intercalate with the polymer chains. This integration has a vital role in augmenting the conductivity of the chains, thereby contributing to an additional boost in the conductivity of the resulting MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB thin film. This heightened conductivity not only characterizes the overall nature of the composite but also acts as a catalyst for improving its optical properties.

The conductivity enhancement achieved through the intercalation of Cl− ions is particularly promising for advancing the optoelectronic characteristics of the produced MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB thin film. This improvement is vital for its application in various areas, including optoelectronics and renewable energy. The optimized thin film is envisioned to exhibit superior optical behavior, paving the way for enhanced performance in optoelectronic devices and showcasing significant potential for applications such as the production of H2 gas, further contributing to advancements in the field of renewable energy.

2.3 Characterization techniques

The validation of the synthesized MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB materials is substantiated through the utilization of diverse analytical instruments. Morphological analyses, encompassing both two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) examinations, are conducted using SEM provided by ZEISS and TEM from Joel, respectively. Meanwhile, the optical properties are investigated using a Berkin-Elmer spectrophotometer. In-depth structural assessments are carried out through XRD utilizing the X’Pert Pro instrument, shedding light on the crystalline nature of the synthesized materials. Chemical analyses, specifically XPS, are performed with Kratos Analytical devices in the USA. These analyses are complemented by FTIR utilizing a Bruker device in the UK, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of functional group estimations within the synthesized materials.

This multi-faceted approach involving SEM, TEM, spectrophotometry, XRD, XPS, and FTIR spectroscopy collectively provides a thorough characterization of the MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB materials. The combination of morphological, optical, and chemical analyses contributes to a comprehensive understanding of the structural, optical, and chemical attributes of the prepared materials, thereby substantiating their synthesis and paving the way for potential applications in various scientific and technological domains.

2.4 H2 gas production study by the photoelectrochemical reaction

The generation of H2 is achieved through the utilization of the highly promising MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB photocathode. This innovative photocathode operates effectively under light exposure, facilitating the conversion of light into hot electrons on its surface. These hot electrons serve as a power force for the neighboring Red Sea water, initiating a process of water splitting and subsequently leading to the production of molecular hydrogen gas (H2).

The fundamental concept underlying this reaction involves the absorption and trapping of photons on the surface of the MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB photocathode. This interaction plays a pivotal role in the creation of photo-carriers: holes and electrons. Significantly, the focus is on harnessing the photo-carried electrons as the primary carriers for initiating the water-splitting process within the adjacent Red Sea water. The chemical composition of this seawater consists of NaCl, MgCl2, MgSO4, CaSO4, K2SO4, and K2CO3, with concentrations of 13.58, 3.79, 1.59, 1.39, 0.19, and 0.2 g·L−1, respectively[16]. By leveraging the surface of MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB to capture and convert incident light into hot electrons, the photocathode is used as a catalyst for the photoelectrochemical reaction. The generated hot electrons drive the electrolysis of Red Sea water, causing the separation of water molecules into oxygen and hydrogen ions. Subsequently, the collected electrons and hydrogen ions combine to produce molecular hydrogen gas.

This innovative approach holds great promise for green hydrogen production, as it capitalizes on the unique properties of the MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB photocathode to efficiently harness light energy and convert it into a sustainable and environmentally friendly source of hydrogen. The utilization of photo-carried electrons in this process signifies a significant advancement in the realm of renewable energy, with potential applications for clean and sustainable hydrogen fuel production.

The quantification of the generated electrons is applied through a three-electrode cell, with the primary working electrode being the MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB thin film. This specialized cell is designed explicitly for water-to-hydrogen conversion, utilizing seawater as the electrolyte. To enhance ion movements and expedite the reaction kinetics, natural heavy water is introduced as an additional catalyst.

The thin film of MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB with a surface area of 1.0 cm2 serves as the main catalyst for the hot electrons provided during the photoelectrochemical reaction. The estimation of these electrons is attributed to the measurement of current density (J ph). As the value of J ph increases, it signifies a greater number of hot electrons being generated on the surface of MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB. This enhanced J ph value is indicative of the increased efficacy of the photocathode in splitting a larger quantity of seawater, consequently leading to a higher production rate of J ph.

The augmentation of J ph reflects the effectiveness of the MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB thin film in harnessing incident light and converting it into hot electrons. These hot electrons play a pivotal role in initiating water-splitting, contributing to the elevated hydrogen gas. The utilization of heavy water as an additional catalyst further promotes efficient ion movements, enhancing the overall performance of the photoelectrochemical cell.

The determination of the produced J ph values is conducted using the CHI608E workstation model, which is adept at assessing various light conditions. These conditions encompass the entire spectrum, ranging from full white light to absolute darkness, as well as under precisely regulated monochromatic light with specific frequencies and energies. The workstation facilitates a comprehensive analysis of the MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB thin film’s performance under diverse lighting scenarios, providing valuable insights into its photoelectrochemical capabilities.

Furthermore, the quantification of the moles of hydrogen gas generated is achieved by employing the Faraday equation of electrolysis. This equation, Eq. 1 [17], involves the correlation between the J ph value obtained from the workstation model and the Faraday constant. By utilizing this relationship, the Faraday equation offers a means to accurately estimate the amount of hydrogen gas produced. This approach enables a quantitative assessment of the photoelectrochemical process’s efficiency under different light conditions, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB thin film’s performance in hydrogen generation.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB physicochemical characterization

XRD analysis provided insights into the crystalline properties of both PA2MB and its composite MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB, as depicted in Figure 1(a). The characteristic peaks associated with MoO3, observed at diffraction angles of 16.92°, 31.94°, 41.82°, 44.74°, and 47.82°, correspond to the (020), (111), (040), (200), and (220) planes, respectively (JCPDS-05-0508) [18]. Similarly, MoS3 is identified by weak peaks at 14.84°, 25.88°, 29.04°, 35.44°, 39.94°, and 51.2°, and these peaks reflect the semicrystalline behavior of the MoS3 materials. The distinct presence of PA2MB is discerned at 19.86°, 22.7°, and 33°. Upon the insertion of these inorganic constituents into the polymer matrix, a significant reduction in peak intensity is observed, indicative of interactions occurring with the organic PA2MB.

The estimated (a) XRD and (b) FTIR analyses for the synthesized MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB nanocomposite.

Specifically, the pure PA2MB exhibits characteristic peaks within the range of 20°–35°, featuring a distinct trio within the crystalline range. In its pristine form, PA2MB displays four peaks spanning 15°–25°. The introduction of MoO3 and MoS3 within the PA2MB matrix leads to an observable decrease in the peak intensity. This reduction underscores the impact of the coating process, signifying the interaction between the inorganic components and the organic PA2MB. The observed alterations in peak intensity offer valuable insights into the structural modifications and crystalline nature of the composite, emphasizing the successful integration of MoO3 and MoS3 into the PA2MB matrix.

The analysis of functional groups within the MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB nanocomposite is conducted through FTIR analyses in comparison to the pure PA2MB polymer (Figure 1(b)). The FTIR spectra of the pure polymer, as outlined in Table 1, reveal distinctive main groups. The introduction of inorganic MoO3–MoS3 groups significantly influences bond vibrations, resulting in observable shifts in group positions. This phenomenon is attributed to electrostatic attractions between the polymer groups and the intercalated inorganic materials.

FT-IR spectral data of PA2MB, MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB and their assignments

| IR data of PA2MB (cm−1) | IR data of MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB (cm−1) | Assignment |

|---|---|---|

| 3,366 (m) | 3,409 (s) | υ (adventitious H2O) |

| 3,062 (m), 3,034 (m) | – | υ (C–H) |

| 2,812 (m) | 2,733 (w) | υ s. (S–H) |

| 1,619 (m) | 1,622 (s) | υ s. (C═N) [19] |

| 1,514 (s) | 1,554 (w) | δ (N–H)ip. |

| 1,428 (vs) | – | δ (N–H)rock |

| 1,126 (s) | 1,112 (w) | δ (C–H)oop [20] |

| 755 (m) | 749 (w) | δ (N–H)tor. |

| 732 (s) | 713 (w) | υ as. (C–S–C endocyclic) |

| 649 (m) | 636 (m) | υ s. (C–S–C endocyclic) |

| 593 (w) | – | υ (S–C–S) |

w: weak, m: medium, s: strong, vs: very strong, υ: stretch, δ: deformation, as.: asymmetric, s.: symmetric, ip.: in-plane, tor.: torsion, and oop: out-of-plane.

The alterations in group positions identified through FTIR analyses provide valuable insights into the dynamic’s insertion between the organic polymer and inorganic materials. These interactions are crucial for understanding the composite’s optical behavior. The shifts in group positions indicate modifications in bond strengths and configurations induced by the incorporation of MoO3–MoS3, elucidating the composite’s structural changes.

This in-depth investigation of the nanocomposite’s functional groups sheds light on the intricate interplay between these constituents. Such insights are pivotal for understanding the composite’s optical behavior and, consequently, enhancing its performance in renewable energy applications. The observed alterations in the FTIR spectra serve as a promising avenue for tailoring the nanocomposite’s properties to optimize its efficiency in applications such as renewable energy, emphasizing its potential significance in advancing clean and sustainable energy technologies.

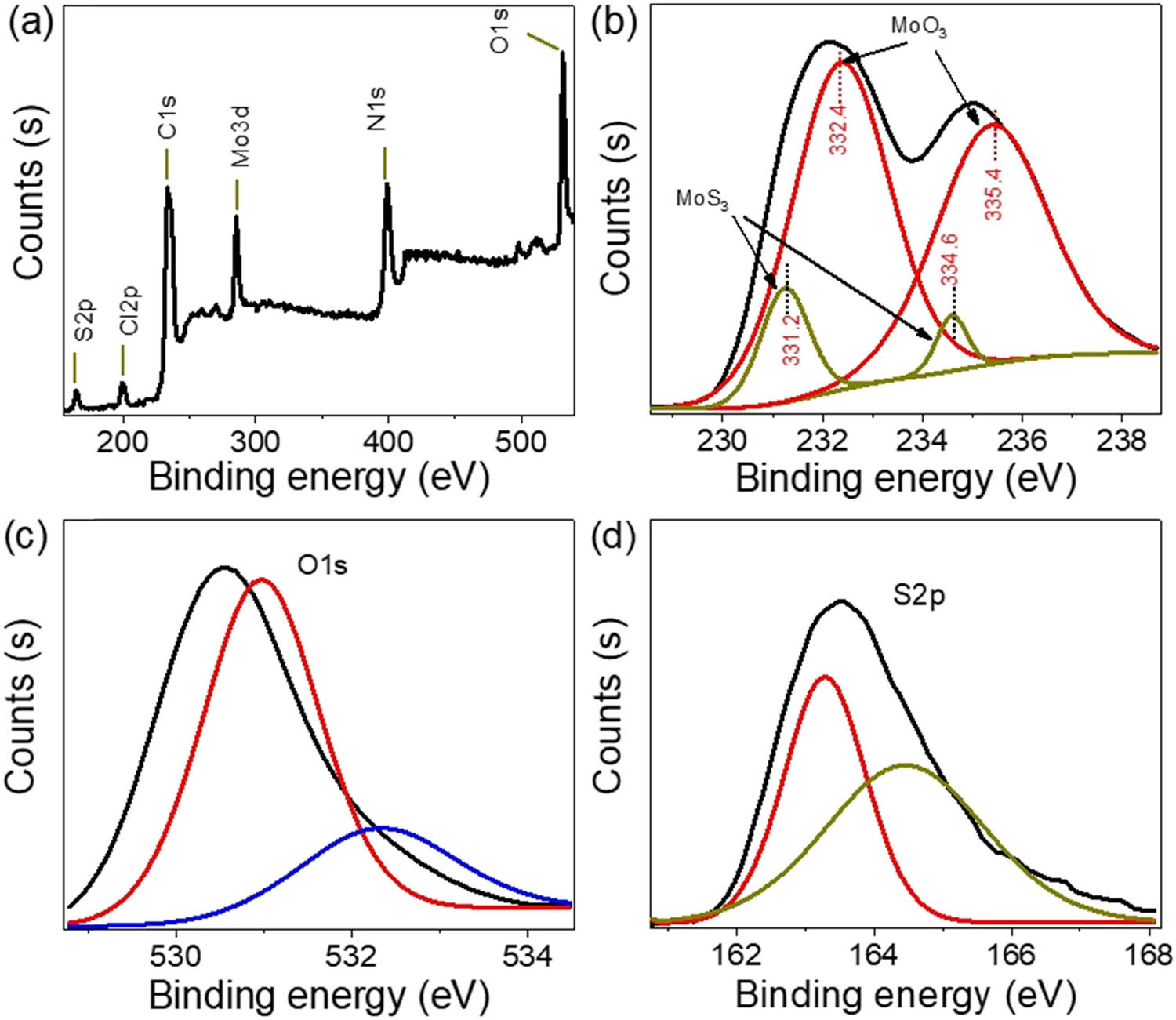

To complement the characterization process, XPS analyses are presented in Figure 2. The survey spectrum (Figure 2(a)) captures the main elements – C, O, N, and S – related to the pristine PA2MB polymer, providing a comprehensive overview of its organic composition and associated electrical and optical properties. The weak peaks observed in the XRD analysis for the MoS3 and PA2MB materials prompted the utilization of XPS for a more detailed examination.

The chemical estimation of the synthesized MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB using (a) XPS survey, (b) Mo3d, (c) O1s orbit, and (d) S2p orbit.

Figure 2(b)–(d) focuses on the inorganic Mo, O, and S elements, respectively. The XPS spectra confirm the main Mo atom in an oxidation state of VI, as evidenced by doublet peaks corresponding to Mo3d5/2 and Mo3d3/2 in both oxide and sulfide states. The positions of these orbits are validated, with Mo3d5/2 peaks at 331.3 and 332.4 eV for sulfide [21] and oxide states [22], respectively, as depicted in Figure 2(b). The oxide and sulfide curves in Figure 2(c) and (d), respectively, are situated at 531 and 163.5 eV, corroborating the distinctive oxidation states.

The XPS analysis thus provides great insights into for chemical constitution and oxidation states of the inorganic MoS3–MoO3 components within the PA2MB matrix. This complements the information obtained from XRD and FTIR analyses, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the composite’s structural and chemical properties. The utilization of XPS proves to be a promising tool in elucidating the intricate details of the nanocomposite, enhancing the overall characterization and paving the way for a nuanced exploration of its electrical and optical features.

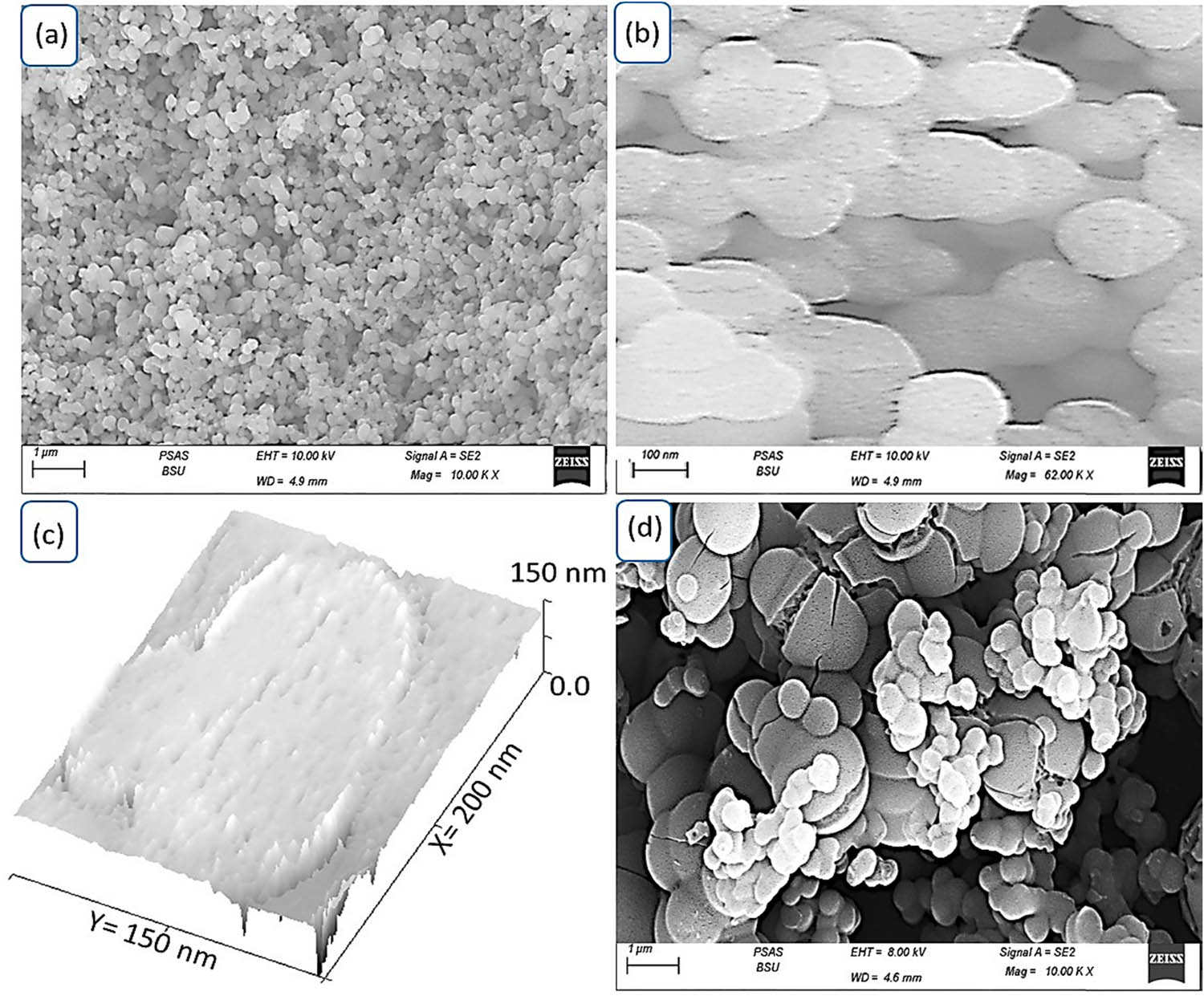

In Figure 3, the topographical and morphological characteristics of the synthesized MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB are highlighted through 3D analyses employing scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and theoretical modeling estimations. The SEM images, as depicted in Figure 3(a) and (b), reveal a remarkable morphological profile of MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB under varying magnifications.

The topographic and morphological of the MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB nanocomposite: (a) SEM at different magnifications for this composite, (c) theoretical simulation, and (d) SEM of PA2MB.

From these SEM figures, a distinct and consistent formation of semi-spherical porous particles is evident, each measuring approximately 130 nm in size. As the magnification increases, the porous structure becomes more apparent, emphasizing the unique features resulting from the integration of inorganic materials within the polymer network. This integration creates spaces for molecular contacts, contributing to the formation of a porous structure within the molecules themselves. Furthermore, at higher magnifications, the SEM images unveil intricate details of the porous structure, demonstrating the presence of voids and interconnected spaces between the formed particles. This porous nature is a direct consequence of the inorganic materials being embedded within the polymer matrix [23].

The porous structure observed in the synthesized MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB is significant, as it not only offers molecular contact points but also creates substantial voids between the molecules. This dual characteristic causes the formation of a highly porous material. The SEM analysis, combined with theoretical modeling estimations, provides a great explanation of the intricate topography and morphology of the composite material, laying the foundation for a thorough exploration of its optical properties and potential applications in various scientific and technological domains.

In Figure 3(c), the theoretical simulation effectively captures the behavior of the MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB nanocomposite. Shiny spots in the simulation represent the presence of inorganic materials inserted through the polymer network. The simulation highlights the larger molecules, indicative of the primary polymer composite, with dimensions of 170 nm in length and 130 nm in width. This simulation visually emphasizes the exceptional characteristics of the nanocomposite, showcasing shiny spots that signify active sites where inorganic materials are embedded within the polymer matrix. These spots create effective traps for incident photons, illustrating the potential for efficient light absorption, and form a cooperative system acting as a source for generating hot electrons.

The trapped photons within these spots serve as active sites, initiating the charge carriers. This phenomenon contributes to the formation of photocurrent (J ph). The visual representation of the theoretical simulation underscores the composite’s ability to efficiently capture and utilize incident light, demonstrating the intricate interplay between the inorganic and organic constituents. These findings further support the nanocomposite’s potential in optoelectronics and renewable energy use, showcasing its promising behavior in generating charge carriers for enhanced functionality [24]. This distinctive characteristic sets the nanocomposite apart from the pristine polymer (Figure 3(d)), which exhibits the formation of larger, cleaved particles of 350 nm. This notable distinction in behavior underscores the unique points of composite formation within the nanocomposite, a phenomenon not observed in the pristine polymer. The nanocomposite’s ability to form smaller and more defined shiny spots, as evidenced in the theoretical simulation, contrasts with the larger cleaved particles observed in the pristine polymer.

The nanocomposite’s capability to create well-defined points of composite formation is a significant feature, showcasing its enhanced structural organization and the incorporation of additional materials. This behavior highlights the impact of introducing inorganic components into the polymer matrix, leading to a more intricate and finely tuned composite structure. The contrast in particle size and morphology between the nanocomposite and the pristine polymer emphasizes the influence of the inorganic materials on the overall composition and structure of the synthesized material, contributing to its unique characteristics and potential applications in various scientific and technological domains.

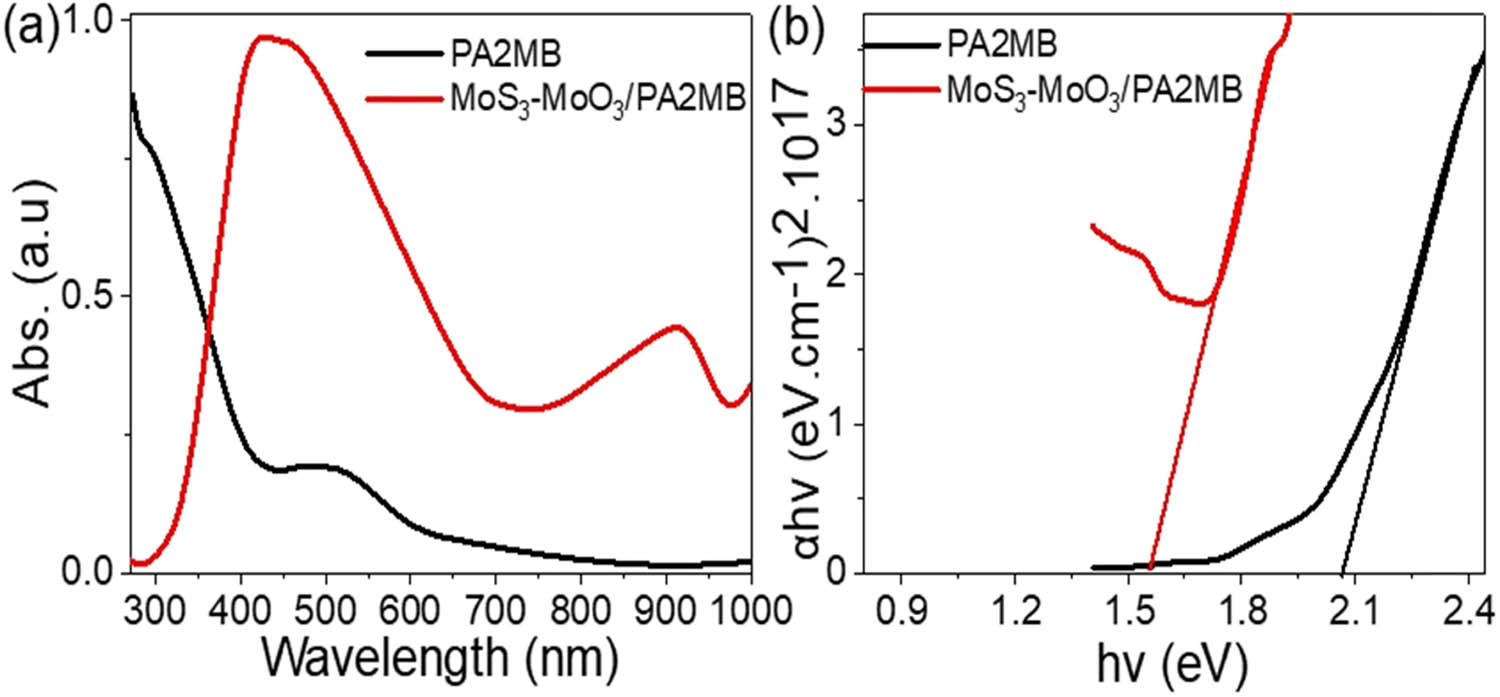

The MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB composite showcases distinctive absorbance characteristics, as illustrated in Figure 4(a), with a broad absorption spectrum extending up to 1,000 nm. This broad absorption range signifies an enhanced efficiency in photon absorption. In contrast, the absorption spectrum of pure PA2MB is primarily limited to the onset of the visible spectrum. The integration of MoS3-MoO3 with PA2MB leads to a synergistic enhancement of the optical capabilities of the resulting nanocomposite.

The optical estimation of the synthesized MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB using (a) optical and (b) bandgap calculations.

This enhancement in optical properties is further substantiated by the assessment of bandgap energies for both pristine PA2MB and the MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB composite. Tauc analysis, incorporating the absorption coefficient (α), reveals a substantial bandgap energy of 1.6 eV for the MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB composite, as indicated in Eq. 2 [25,26]. This bandgap energy determination highlights the composite’s significant potential for effective light absorption for various photocatalytic applications (Figure 4(b)). The observed broad absorption spectrum and lowered bandgap energy underscore the nanocomposite’s capability to harness a wider range of wavelengths and efficiently absorb photons, making it a compelling material for applications in optoelectronics and photocatalysis. The synergistic effects arising from the integration of MoS3–MoO3 with PA2MB contribute to the unique optical properties exhibited by the composite material, opening avenues for diverse technological applications:

The MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB materials, characterized by their narrow bandgap, exhibit substantial potential in optoelectronic applications. Their physical properties confer heightened sensitivity to light photons across various energies and frequencies. This provides great proof for integration into a diverse range of optoelectronic devices, particularly those designed for detecting light across extensive wavelengths.

Due to the small bandgap, MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB composites efficiently absorb photons across a diverse energy spectrum, enhancing their capability to detect light signals over a wide spectral range. This characteristic of broad-spectrum light absorption significantly improves the functionality of optoelectronic devices by providing heightened sensitivity to a range of light wavelengths. The materials’ enhanced receptivity to various photon frequencies and energies provides new possibilities for their integration into advanced optoelectronic structures.

The MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB composites are well-equipped to meet rigorous light-sensing requirements across different wavelength conditions, whether the light is visible, ultraviolet, or infrared. The narrow bandgap of these materials underscores their substantial compatibility with sophisticated optoelectronic systems. Their proficiency in photon absorption across an extensive spectrum not only makes them ideal for complex optoelectronic devices but also significantly enhances light-sensing capabilities under various wavelength scenarios, making these composites suitable for integration into a wide array of cutting-edge applications.

3.2 MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB photocathode electrochemical study

The performance of the MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB photocathode in the water-splitting reaction demonstrates significant promise, particularly in response to photon illumination. With a particle size of 130 nm, coupled with remarkable morphological porous characteristics and a bandgap of 1.6 eV, this photocathode emerges as an optimal candidate for catalyzing this reaction. These attributes act as attractors for photons within the porous structure, which is replete with active sites conducive to the splitting reaction.

The bandgap of 1.6 eV renders the photocathode adept at absorbing photons across a broad spectrum, including regions extending into the FTIR range. This broad optical absorbance efficiency, exceeding 50% concerning sunlight, underscores its proficiency in harnessing solar energy. Upon photon absorption, these energy-rich photons induce multiple electron transitions within the photocathode, leading to the formation of an extensive electron cloud. This cloud predominantly accumulates on the inorganic MoO3–MoS3 materials, facilitated by an additional electron transition occurring within the PA2MB polymer.

The suitability of the MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB photocathode for the water-splitting reaction is intricately linked to its structural and compositional characteristics. The porous nature of the surface offers a multitude of active sites, promoting efficient photon capture and subsequent electron transfer processes. Additionally, the bandgap of 1.6 eV enables the absorption of photons spanning a wide range of wavelengths, ensuring robust performance across diverse optical spectra.

The orchestrated interplay between the MoO3–MoS3 and the PA2MB polymer further enhances the photocathode’s efficacy. As photons impinge upon the photocathode, they trigger electron transitions within both the inorganic and organic components. The resulting electron cloud, predominantly localized on the MoO3–MoS3 materials, signifies the initiation of the water-splitting. Furthermore, the presence of the PA2MB polymer not only facilitates electron transfer but also contributes to the stability of this photocathode [27]. Its synergistic interaction with the inorganic materials ensures efficient charge separation and prevents undesired charge recombination, thereby enhancing the photocathode’s durability under prolonged operation.

The MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB photocathode is constructed using a combination of metal oxide, metal sulfide, and polymer materials. This diverse composition enables the photocathode to exhibit broad optical absorbance across a wide spectrum. Additionally, the electrical properties of these materials resemble those of semiconductor materials, allowing them to effectively respond to incident light. The network structure formed by the PA2MB polymer serves a crucial role as a protective coating for the entire photocathode assembly.

As photons are absorbed by the photocathode, they induce the formation of electron clouds within the material. These electron clouds can be likened to a river of electrons flowing through the photocathode. This accumulation of electrons initiates a cascade of reactions upon contact with the surrounding seawater. The electrons released from the photocathode react with the water molecules, driving the reduction reaction of green hydrogen gas. This process is facilitated by the electron-rich environment created within the photocathode, which promotes efficient electron transfer to the water molecules.

Overall, the unique combination of materials in the MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB photocathode enables it to efficiently harness solar energy and drive the sustainable generation of hydrogen gas. The protective coating provided by the PA2MB polymer ensures the durability of the photocathode, allowing for continuous operation and long-term performance in diverse environmental conditions. The production of green H2 gas is assessed via the electrochemical reaction, which correlates with the generated J ph value. This value directly corresponds to the amount of H2 gas produced as a result of the reduction reaction. The evaluation process employs the CHI608E instrument within a specially designed three-electrode cell tailored to the specifics of the laboratory study. The cell features three necks corresponding to the three electrodes utilized, with the MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB photocathode serving as the primary electrode. This setup enables precise measurement and analysis of the electrochemical performance of the photocathode, providing valuable insights into its efficiency and effectiveness in facilitating the generation of hydrogen gas. This green H2 gas holds significant promise due to its high combustion energy and environmentally friendly combustion by-products. Leveraging Red Sea water as a natural source of electricity offers several advantages, including widespread availability and cost-effectiveness, thus enhancing the economic viability of this promising reaction. The inclusion of heavy metals plays a self-sacrificing role, further facilitating the reaction process. The utilization of a neutral medium contributes to prolonging the life of the photoelectrode. Unlike the literature that employs highly basic or acidic media, such as H2SO4 or NaOH, which not only increase the economic costs associated with the splitting reaction but also exacerbate the corrosion of the cathode, a neutral medium offers a more sustainable and cost-effective alternative. By avoiding the need for expensive and corrosive chemicals, the overall economic feasibility of the process is greatly enhanced. Additionally, the neutral medium ensures the longevity of the photoelectrode by minimizing corrosion, thereby reducing maintenance costs and increasing operational efficiency.

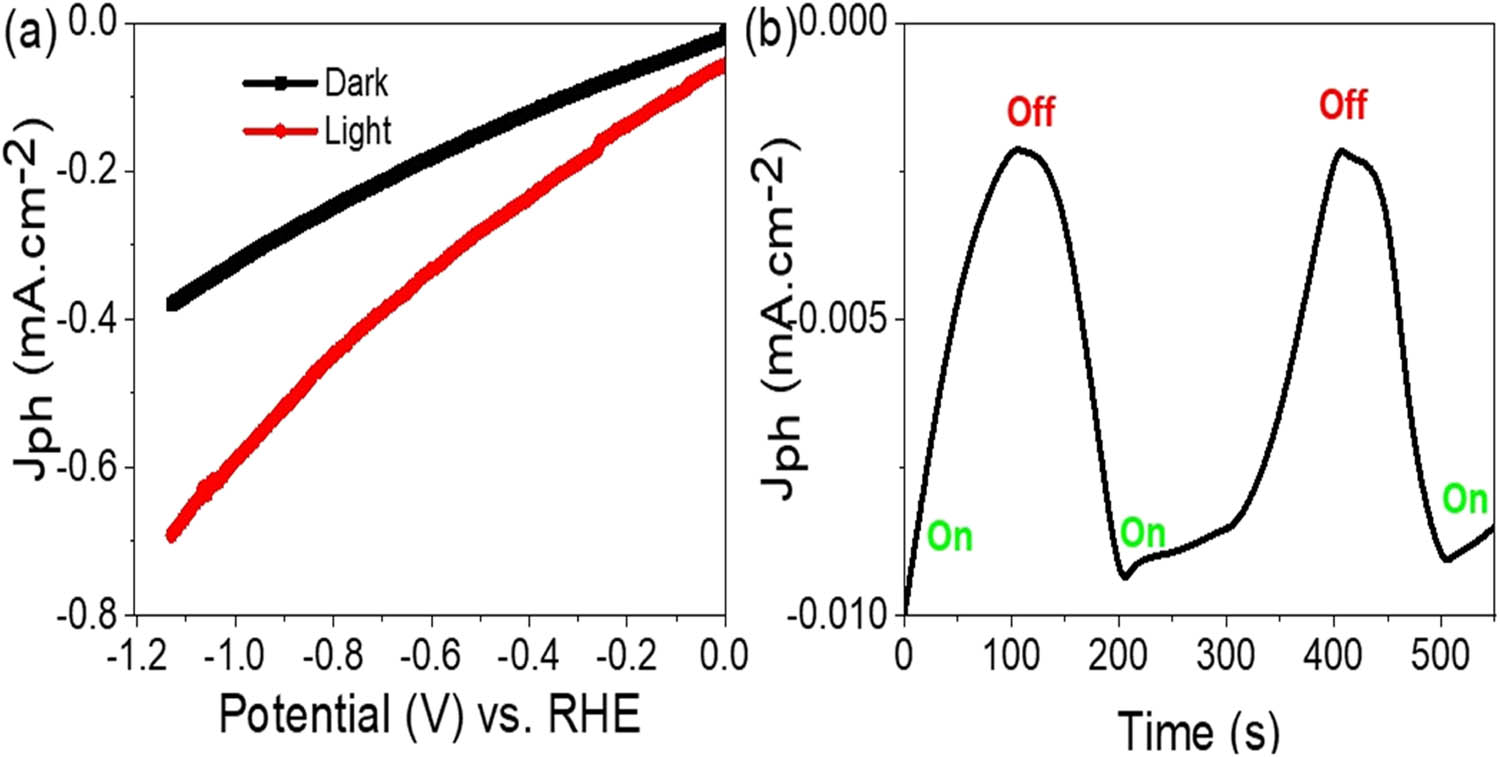

The assessment of the fabricated MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB photocathode under white light, as depicted in Figure 5(a), involves evaluating its sensitivity based on the H2 moles generated, represented by the rate of H2 moles, J ph. The calculated J ph value of −0.7 mA·cm−2 indicates promising performance, highlighting the high sensitivity of this photocathode in producing hydrogen gas through seawater splitting. The J ph value strongly indicates the rate or amount of the splitting reaction driven by the generated hot electrons. A high J ph value signifies a substantial production of H2 gas. One notable advantage of the MoO3-MoS3/PA2MB photocathode is its construction on a cost-effective glass substrate. This aspect contributes to the overall affordability of the hydrogen gas produced. The utilization of seawater as a natural resource, coupled with the inexpensive glass substrate, renders the entire process economically advantageous. The obtained J ph value of −0.7 mA·cm−2 illustrates the significance of this combination of materials in achieving efficient hydrogen gas production. The efficacy of the MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB photocathode hinges on the sequential collaboration of its constituent materials. The interaction between MoO3, MoS3, and PA2MB facilitates electron accumulation, particularly over the inorganic materials, due to their lower conducting band levels compared to PA2MB. This electron accumulation results in the formation of electron clouds with a substantial electric field encompassing all the materials [24,28]. Furthermore, this electron accumulation initiates a series of reactions for the generation of OH radicals, which subsequently react with additional water molecules to produce H2 gas on the photocathode surface. Meanwhile, O2 gas is concurrently generated on the auxiliary electrode.

Response of the fabricated MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB photocathode under (a) white light and (b) chopped white light.

In essence, the orchestrated interplay between MoO3, MoS3, and PA2MB, facilitated by the glass substrate, drives the efficient generation of hydrogen gas from seawater. This process underscores the potential for sustainable and cost-effective hydrogen production, positioning the MoO3-MoS3/PA2MB photocathode as a promising solution for renewable energy applications.

The sensitivity of the fabricated MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB photocathode is assessed by observing the chopped on/off light conditions, as illustrated in Figure 5(b). This experimental setup demonstrates a significant sequential increase and decrease in the J ph value, corresponding to the modulation of light exposure. The observed behavior elucidates the correlation between light intensity and the generation rate of H2 gas, with an increase during illumination and a decrease in the absence of light. The phenomenon of sequential changes in J ph values under light conditions is indicative of the formation of hot electrons. These hot electrons are generated as a result of the activation of active sites on the photocathode surface by incident photons possessing various kinetic energies. The interaction between light and the photocathode material triggers a cascade of events leading to the liberation of electrons, subsequently contributing to the enhanced generation of H2 gas. The role of the PA2MB polymer in this context is particularly promising. Beyond its function as a component of the photocathode material, PA2MB exhibits photoactivity and serves a protective role. This appeared in the sequential changes in J ph values in response to the on/off chopped light conditions. The PA2MB polymer not only participates in the photochemical processes involved in hydrogen generation but also acts as a shield, safeguarding the active sites and preserving their functionality. Overall, the integration of MoO3, MoS3, and PA2MB in the photocathode assembly, coupled with the modulation of light exposure, highlights the intricate interplay between materials and external stimuli in driving efficient hydrogen production. The role of PA2MB as both a photoactive component and a protective barrier underscores its significance in enhancing the sensitivity and performance of the fabricated photocathode system.

The sensitivity of the MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB photocathode to incident photons and its potential for hydrogen gas generation is further explored by investigating the effect of photon energy (Figure 6(a)). The evaluated J ph values vary depending on the photon energy, indicating a correlation between photon energy and photocurrent generation. Figure 6(b) demonstrates a decrease in J ph from −0.53 to −0.43 mA·cm−2, as the photon energies decrease from 3.6 to 1.7 eV, respectively.

Response of the fabricated MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB photocathode under (a) various wavelengths and (b) the evaluated photon energy.

Considering the estimated bandgap value of 1.6 eV for the MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB photocathode, all incident photons possess energies sufficient for generating photocarriers. Additionally, photons with energies exceeding the bandgap contribute excess energy, which manifests as kinetic energy, further motivating the generated electrons. This results in an increase in kinetic energy as photon energy ranges from 1.7 to 3.6 eV. The hot electrons generated as a result of photon absorption serve as initiators for the splitting reaction by interacting with water molecules. These hot electrons have a great role in catalyzing the reaction, driving the production of hydrogen gas [29].

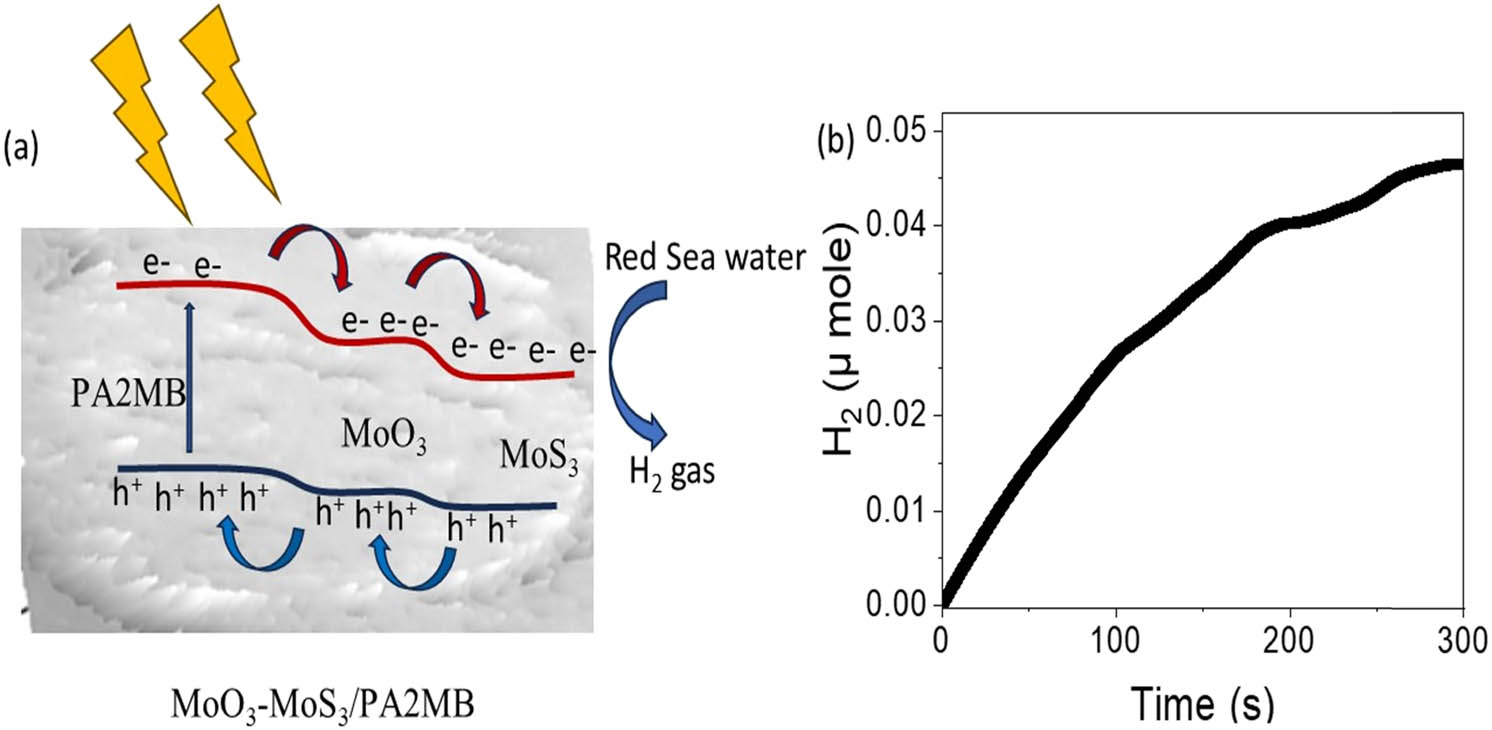

To estimate the energies of these hot electrons, the general equation E = hv is utilized, where E represents energy and v is the photon frequency [30]. Since energy (E) is directly proportional to frequency (v), the energy of hot electrons can be estimated for the frequency of incident light. The determination of hot electron energies provides insights into their catalytic potential and their ability to facilitate the splitting of water molecules [31]. By harnessing photons with appropriate energies, the MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB photocathode demonstrates its versatility in efficiently generating hydrogen gas. Utilizing the Faraday equation (Eq. 1), the evolution of H2 gas from the MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB photocathode is estimated, as depicted in Figure 7. This equation leverages the relationship between electrolysis and the Faraday constant (96,500 C), yielding a promising estimation of 6.0 µmol/10 cm·h−1 for H2 gas generation. Supported on a glass substrate, this photocathode offers significant advantages for mass production and easy fabrication, enhancing its suitability for industrial applications. Particularly noteworthy is its compatibility with Red Sea water, a readily available natural source. These technical and commercial advantages position the MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB photocathode as a compelling option for widespread adoption. The stepwise electron flow through the upper levels of this photocathode leads to charge accumulation on the MoS3, which is then transferred to water, facilitating further splitting and hydrogen gas generation. Meanwhile, the holes move in the opposite direction, accumulating positive charges to counterbalance the reduction in negative charges. This sequential process is illustrated in Figure 7(a). The heavy metals present in seawater play a significant role in hydrogen gas production by enhancing mobility, which drives the splitting reaction through the formation of OH radicals. In Table 2, the efficiency of this photocathode is compared with other electrodes from the existing literature. This comparative analysis provides valuable insights into its performance relative to alternative technologies, further highlighting its potential as a leading candidate for hydrogen generation applications. From this table, the fabricated MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB photocathode estimates the optimum J ph of 0.7 mA·cm−2, which is much greater than any other previous literature, and then the rate of the H2 gas is much greater.

The estimated (a) mechanism and (b) H2 moles with time on the fabricated MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB photocathode for the H2 gas generation.

Estimated H2 moles with time on the fabricated MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB photocathode relative to the other literature related to our lab

| Photoelectrode | Electrolyte | J ph (mA·cm−2) |

|---|---|---|

| As2O3-poly(1H-pyrrole) [32] | Red Sea water | 0.15 |

| Polypyrrole/NiO [33] | Wastewater | 0.1 |

| Polypyrrole/graphene oxide [34] | Wastewater | 0.11 |

| ANI/Ag2O/Ag [35] | Wastewater | 0.012 |

| PMT/roll-GO [36] | Sewage water | 0.09 |

| MoO3–MoS3/PA2MB (this work) | Red Sea water | 0.7 |

4 Conclusions

This study focuses on generating environmentally friendly hydrogen gas from Red Sea water by developing a novel photocathode made from MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB. The newly fabricated photocathode demonstrates excellent performance, achieving a current density of −0.7 mA·cm−² and producing hydrogen gas at a rate of 6.0 µmol per 10 cm² per hour. Its effectiveness is further supported by its favorable morphological features, including semi-spherical structures sized at 130 × 170 nm. The photocathode was subjected to extensive testing under various optical conditions, with photon energies and frequencies ranging from 3.6 to 1.7 eV. These tests revealed the photocathode’s ability to adapt to different optical environments, making it highly versatile for hydrogen gas production. As photon energies decreased from 3.6 to 1.7 eV, the photocurrent density (J ph) correspondingly reduced from −0.53 to −0.43 mA·cm−², demonstrating the photocathode’s capability to harness light energy efficiently across a range of energy levels. The successful synthesis of the MoS3–MoO3/PA2MB photocathode represents a significant step forward in the direct conversion of seawater into hydrogen gas, opening new possibilities for commercial applications. This technology is particularly promising for use in remote areas and economically disadvantaged regions, where access to traditional energy sources is often limited. The adaptability and effectiveness of the photocathode under varying optical conditions make it an ideal solution for hydrogen gas production in a wide range of environments. This advancement holds great potential for contributing to renewable energy solutions, offering a sustainable and efficient method of producing hydrogen gas directly from seawater, with broad applications for global energy needs.

Acknowledgments

Researchers Supporting Program Number (RSPD2024R845), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Funding information: This research was supported by Researchers Supporting Program (Number RSPD2024R845), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contributions: Mohamed Rabia: experimental, analyses, and writing. Eman Aldosari, Mahmoud Moussa, Ahmed Adel A. Abdelazeez, and Asmaa M. Elsayed: writing, supervision, revision, and ordering the work. The funding is related to Eman Aldosari.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Yan J, Hu L, Cui L, Shen Q, Liu X, Jia H, et al. Synthesis of disorder–order TaON homojunction for photocatalytic hydrogen generation under visible light. J Mater Sci. 2021;56:9791–806. 10.1007/S10853-021-05896-0/FIGURES/12.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Wang P, Guan Z, Li Q, Yang J. Efficient visible-light-driven photocatalytic hydrogen production from water by using Eosin Y-sensitized novel g-C3N4/Pt/GO composites. J Mater Sci. 2018;53:774–86. 10.1007/S10853-017-1540-5/FIGURES/10.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Giuntoli F, Menegon L, Siron G, Cognigni F, Leroux H, Compagnoni R, et al. Methane-hydrogen-rich fluid migration may trigger seismic failure in subduction zones at forearc depths. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):1–16. 10.1038/s41467-023-44641-w.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Moridon SNF, Arifin K, Yunus RM, Minggu LJ, Kassim MB. Photocatalytic water splitting performance of TiO2 sensitized by metal chalcogenides: A review. Ceram Int. 2022;48:5892–907. 10.1016/J.CERAMINT.2021.11.199.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Lamiel C, Hussain I, Rabiee H, Ogunsakin OR, Zhang K. Metal-organic framework-derived transition metal chalcogenides (S, Se, and Te): Challenges, recent progress, and future directions in electrochemical energy storage and conversion systems. Coord Chem Rev. 2023;480:215030. 10.1016/J.CCR.2023.215030.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Alnuwaiser MA, Rabia M. Hollow mushroom nanomaterials for potentiometric sensing of Pb2+ ions in water via the intercalation of iodide ions into the polypyrrole matrix. Open Chem. 2024;22(1):20240217.10.1515/chem-2024-0217Suche in Google Scholar

[7] El Ouardi M, Idrissi E, Ahsaine A, BaQais A, Saadi M, Arab M. Current advances on nanostructured oxide photoelectrocatalysts for water splitting: A comprehensive review. Surf Interfaces. 2024;45:103850. 10.1016/J.SURFIN.2024.103850.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Xing Y, Liu Z, Li B, Li L, Yang X, Zhang G. The contrastive study of two thiophene-derived symmetrical Schiff bases as fluorescence sensors for Ga3+ detection. Sens Actuators B: Chem. 2021;347:130497. 10.1016/J.SNB.2021.130497.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Aydın EB, Aydın M, Sezgintürk MK. A label-free electrochemical biosensor for highly sensitive detection of GM2A based on gold nanoparticles/conducting amino-functionalized thiophene polymer layer. Sens Actuators B: Chem. 2023;392:134025. 10.1016/J.SNB.2023.134025.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Chen H, Zhu L, Jiang W, Ji H, Zhou X, Qin Y, et al. Multiple fluorescence polymer dots-based differential array sensors for highly efficient heavy metal ions detection. Environ Res. 2023;232:116278. 10.1016/J.ENVRES.2023.116278.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Liu T, Finn L, Yu M, Wang H, Zhai T, Lu X, et al. Polyaniline and polypyrrole pseudocapacitor electrodes with excellent cycling stability. Nano Lett. 2014;14:2522–7. 10.1021/nl500255v.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Baydaroglu FO, Özdemir E, Gürek AG. Polypyrrole supported Co–W–B nanoparticles as an efficient catalyst for improved hydrogen generation from hydrolysis of sodium borohydride. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2022;47:9643–52. 10.1016/J.IJHYDENE.2022.01.052.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Ecer Ü, Zengin A, Şahan T. Hydrogen generation from NaBH4 hydrolysis catalyzed by cobalt (0)-Deposited cross-linked polymer brushes: Optimization with an experimental design approach. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2023;48:12814–25. 10.1016/J.IJHYDENE.2022.12.224.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Al Angari YM, Ewais HA, Rabia M. Hydrogen generation from Red Sea water using CsSnI2Cl lead-free perovskite/porous CuO nanomaterials: Coast of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron. 2023;34:1–12. 10.1007/S10854-023-11597-Y/METRICS.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] El-Rahman AMA, Rabia M, Mohamed SH. Nitrogen doped TiO2 films for hydrogen generation and optoelectronic applications. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron. 2023;34(14):1–9. 10.1007/S10854-023-10551-2.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Aguirre-Astrain A, Luévano-Hipólito E, Torres-Martínez LM. Integration of 2D printing technologies for AV2O6 (A = Ca, Sr, Ba)-MO (M = Cu, Ni, Zn) photocatalyst manufacturing to solar fuels production using seawater. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2021;46:37294–310. 10.1016/J.IJHYDENE.2021.09.007.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Mohamed F, Rabia M, Shaban M. Synthesis and characterization of biogenic iron oxides of different nanomorphologies from pomegranate peels for efficient solar hydrogen production. J Mater Res Technol. 2020;9:4255–71. 10.1016/J.JMRT.2020.02.052.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Sen SK, Dutta S, Khan MR, Manir MS, Dutta S, Al Mortuza A, et al. Characterization and antibacterial activity study of hydrothermally synthesized h-MoO3 nanorods and α-MoO3 nanoplates. BioNanoScience. 2019;9:873–82. 10.1007/S12668-019-00671-7/TABLES/3.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Azzam EMS, Abd El-Salam HM, Aboad RS. Kinetic preparation and antibacterial activity of nanocrystalline poly(2-aminothiophenol). Polym Bull. 2019;76:1929–47. 10.1007/S00289-018-2405-Z/FIGURES/14.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Atta A, Abdeltwab E, Negm H, Al-Harbi N, Rabia M, Abdelhamied MM. Characterization and linear/non-linear optical properties of polypyrrole/NiO for optoelectronic devices. Inorg Chem Commun. 2023;152:110726. 10.1016/J.INOCHE.2023.110726.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Cheng CK, Lin JY, Huang KC, Yeh TK, Hsieh CK. Enhanced efficiency of dye-sensitized solar counter electrodes consisting of two-dimensional nanostructural molybdenum disulfide nanosheets supported Pt nanoparticles. Coatings. 2017;7(10):167. 10.3390/COATINGS7100167.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Elsayed AM, Alkallas FH, Trabelsi ABG, Rabia M. Highly uniform spherical MoO2-MoO3/polypyrrole core-shell nanocomposite as an optoelectronic photodetector in UV, Vis, and IR domains. Micromachines. 2023;14(9):1694. 10.3390/MI14091694.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Seredych M, Łoś S, Giannakoudakis DA, Rodríguez-Castellón E, Bandosz TJ. Photoactivity of g-C3N4/S-doped porous carbon composite: Synergistic effect of composite formation. ChemSusChem. 2016;9:795–9. 10.1002/CSSC.201501658.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Valenti M, Venugopal A, Tordera D, Jonsson MP, Biskos G, Schmidt-Ott A, et al. Hot carrier generation and extraction of plasmonic alloy nanoparticles. ACS Photonics. 2017;4:1146–52. 10.1021/acsphotonics.6b01048.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Haryński Ł, Olejnik A, Grochowska K, Siuzdak K. A facile method for Tauc exponent and corresponding electronic transitions determination in semiconductors directly from UV–Vis spectroscopy data. Opt Mater. 2022;127:112205. 10.1016/J.OPTMAT.2022.112205.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Mergen ÖB, Arda E. Determination of optical band gap energies of CS/MWCNT bio-nanocomposites by Tauc and ASF methods. Synth Met. 2020;269:116539. 10.1016/J.SYNTHMET.2020.116539.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Boomi P, Anandha Raj J, Palaniappan SP, Poorani G, Selvam S, Gurumallesh Prabu H, et al. Improved conductivity and antibacterial activity of poly(2-aminothiophenol)-silver nanocomposite against human pathogens. J Photochem Photobiol B: Biol. 2018;178:323–9. 10.1016/J.JPHOTOBIOL.2017.11.029.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Kim M, Lin M, Son J, Xu H, Nam JM. Hot-electron-mediated photochemical reactions: Principles, recent advances, and challenges. Adv Opt Mater. 2017;5:1–21. 10.1002/adom.201700004.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Sharma S, Kumar D, Khare N. Plasmonic Ag nanoparticles decorated Bi 2 S 3 nanorods and nanoflowers: Their comparative assessment for photoelectrochemical water splitting. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2019;44:3538–52. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.11.238.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Ahzan S, Darminto D, Nugroho FAA, Prayogi S. Synthesis and characterization of ZnO thin layers using sol-gel spin coating method. J Penelit dan Pengkaj Ilmu Pendidikan: e-Saintika. 2021;5:182–94. 10.36312/ESAINTIKA.V5I2.506.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] An X, Kays JC, Lightcap IV, Ouyang T, Dennis AM, Reinhard BM. Wavelength-dependent bifunctional plasmonic photocatalysis in Au/chalcopyrite hybrid nanostructures. ACS Nano. 2022;16:6813–24. 10.1021/ACSNANO.2C01706/SUPPL_FILE/NN2C01706_SI_001.PDF.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Hadia NMA, Rabia M, Alzaid M, Mohamed WS, Hasaneen MF, Ezzeldien M, et al. As2O3-poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite for hydrogen generation from Red Sea water with high efficiencey. Phys Scr. 2023;98:085509. 10.1088/1402-4896/ACE391.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Atta A, Negm H, Abdeltwab E, Rabia M, Abdelhamied MM. Facile fabrication of polypyrrole/NiOx core-shell nanocomposites for hydrogen production from wastewater. Polym Adv Technol. 2023;34(5):1633–41. 10.1002/PAT.5997.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Hamid MM, Alruqi M, Elsayed AM, Atta MM, Hanafi HA, Rabia M. Testing the photo-electrocatalytic hydrogen production of polypyrrole quantum dot by combining with graphene oxide sheets on glass slide. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron. 2023;34:1–11. 10.1007/S10854-023-10229-9/METRICS.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Hadia NMA, Hajjiah A, Elsayed AM, Mohamed SH, Alruqi M, Shaban M, et al. Bunch of grape-like shape PANI/Ag2O/Ag nanocomposite photocatalyst for hydrogen generation from wastewater. Adsorpt Sci Technol. 2022;2022:1–11. 10.1155/2022/4282485.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Helmy A, Rabia M, Shaban M, Ashraf AM, Ahmed S, Ahmed AM. Graphite/rolled graphene oxide/carbon nanotube photoelectrode for water splitting of exhaust car solution. Int J Energy Res. 2020;44:7687–97. 10.1002/er.5501.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation