Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

-

Fatimah Saleh Al-Khattaf

Abstract

Background and objective

As a last option, multidrug-resistant Gram-negative infections (caused by Enterobacteriaceae) are treated with the antibiotic colistin, also known as polymyxin E. Colistin-resistant superbugs predispose people to untreatable infections, possibly leading to a high mortality rate. This project aims to study the effect of Acacia nilotica aqueous extract and zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) on colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumonia (CRKP).

Materials and methods

ZnO-NPs were synthesized using the green method and characterized by UV-vis, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, and X-ray diffraction. The zone of inhibition (ZI) was measured using the agar-well diffusion method, and the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration were estimated to determine the antimicrobial activity of the tested compound. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electronic microscopy (TEM) were used to investigate the alterations in bacterial cells that were treated with the tested drugs.

Results

The synthesized ZnO-NPs presented good chemical and physical properties, and the plant extract and ZnO-NPs displayed a large ZI. ZnO-NPs had the lowest MIC (0.2 mg·mL−1). SEM and TEM observations revealed various morphological modifications in CRKP cells, including cell shrinkage, cell damage, cytoplasm loss, cell wall thinning, and cell death.

Conclusion

A. nilotica aqueous extract and ZnO-NPs could be used as alternative natural products to produce antibacterial drugs and to prevent CRKP infection.

1 Introduction

Polymyxins, particularly colistin, are a crucial “last resort” treatment for carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections [1]. Bacterial resistance to colistin has grown with its usage [1]. First discovered in the United States in 1996 [1], Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases (KPCs) are lactamases produced by Gram-negative bacteria [2]. They are responsible for a wide range of hospital-acquired infections, including wound infection, bacteremia, pneumonia, and urinary tract infections (UTIs), especially in immunocompromised individuals [3,4]. Colistin resistance among KPC-producing bacteria has increased from less than 2–9% globally [5,6]. Since 2013, colistin resistance has spread to one-third of carbapenem-resistant isolates in Europe outbreaks of colistin resistance.

K. pneumoniae have been recorded in the United States, Canada, and South America [5]. Saudi Arabia now has a high frequency of colistin resistance in key Gram-negative bacteria [7]. KPC-producing bacteria have recently developed resistance to the last line of treatment, colistin. Therefore, researchers, clinicians, and patients try to identify strong ecofriendly compounds to reduce the side effects of antibiotics on human cells and the resistance of bacteria to antibiotics. Researchers have extracted the components of medicinal plants used in traditional therapies that can fight resistant microorganisms and used them in the production of small molecules known as nanoparticles. One of the most common medicinal plants applied as an antimicrobial agent is Acacia nilotica (L.) Del., a tropical and subtropical medicinal plant native to Sudan and the Sahelian region and is widely distributed in northern Nigeria [8]. The herbs in folk medicine are useful against a number of human ailments; the leaves, bark, and pods are applied to treat cancer, cough, diarrhea, fever, small pox, piles, vaginitis, and microbial infections [9]. A. nilotica aqueous extract has been used in the green synthesis of nanoparticles due to its unique properties listed below:

Reduction agent which is facilitating the conversion of metal ions to nanoparticles and stabilization agent which is preventing nanoparticle aggregation. A. nilotica helps in the formation and stabilization of nanoparticles during the synthesis process [10].

Eco-friendly approach. A. nilotica provides a sustainable alternative to conventional chemical methods [10].

Antibacterial and antifungal properties: A. nilotica contains bioactive compounds with antibacterial and antifungal properties. These properties make it suitable for synthesizing nanoparticles with potential antimicrobial applications. For example, Elamary and his group [11] detected that A. nilotica aqueous extract reduced the biofilm activity of Escherichia coli, K. pneumoniae, P. mirabilis, and Pseudomonas aeuroginosa isolated from a patient with UTI. Researchers also reported the activity of A. nilotica against fungi and bacteria [11,12].

A. nilotica contains several important secondary metabolites, including amines, cyanogenic glycosides, flavonoids, alkaloids, cyclitols, fluoroacetate, diterpenes, fatty acids, terpenes, hydrolyzable tannins, and condensed tannins. These compounds play significant roles as anticancer, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory agents. Interestingly, this property is similar to that observed in lichens and certain other plants that also produce many of these secondary metabolites [13–15]. Regarding the disadvantages of A. nilotica fruit, there are no documented reports of toxicity or adverse effects associated with its use at appropriate doses and durations [16]. However, as with any substance, excessive consumption or prolonged use may lead to adverse effects. It is crucial to follow recommended guidelines when using herbal remedies.

Scientists have recently shown interest in the production of nanoparticles from plant extracts because their small size, high surface area, and physical properties make them appropriate for use in medical sciences. In addition, they are inexpensive and have no impact on the environment [10,17,18]. One of the metals commonly used to synthesize nanoparticles is ZnO, which has numerous applications due to its excellent optical, electrical, piezoelectric, semiconducting, and chemical sensing properties [19]. Studies have investigated the antibacterial activity of ZnO nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) and the survival of bacteria in the presence of ZnO [19]. Researchers also analyzed the elements associated with the antibacterial activity of ZnO-NPs, the mechanism underlying their toxicity to bacteria, and their uses in food. When ZnO is reduced to micrometer and nanometer sizes, it serves as an antibacterial agent. ZnO-NPs react with the bacteria’s surface and core, resulting in a bactericidal effect [20,21]. Most studies on colistin-resistant K. pneumonia (CRKP) have only focused on the prevalence, characterization, and outbreaks. In addition, information on how ZnO-NPs and A. nilotica affect the cells and activity of CRKP is lacking. The current work aimed to explore the morphological alteration of CRKP cells treated by ZnO-NPs and A. nilotica aqueous extract. The specific objective was to evaluate the zone of inhibition (ZI) of tested bacteria treated by ZnO-NPs and A. nilotica aqueous extract and to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC). The activities of A. nilotica aqueous extract and ZnO-NPs synthesized from A. nilotica plant extract were also compared. The innovative aspects of this study, compared to previous research, involve investigating cell alterations in CRKP. This investigation is conducted using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electronic microscopy (TEM), facilitated by the aqueous extract of A. nilotica and ZnO-NP. These findings shed light on how eco-friendly compounds can impact the most resilient bacterial cells.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Preparation and characterization of A. nilotica aqueous extract and ZnO-NPs

This study was accomplished from February 2023 to September 2023. A. nilotica fruits were purchased from the local herbal market in Khartoum, Sudan and were authenticated by the researcher, Dr Haider Abdelgadir at the Medicinal and Aromatic Plant Research Institute in Khartoum, Sudan. The fruits were rinsed with clean tap water, dried at room temperature, and ground into a coarse powder. The aqueous extract was prepared using Nagappan’s method with few modifications [22]. In brief, 20 g of ground plant was dissolved in 200 mL of distilled water and then incubated in a shaker incubator (New Brunswick Scientific, Eppendorf, CT, USA) at room temperature with 180 rev·min−1 for 48 h. The extract was filtered using Whatman 1 filter paper and Millipore filter membranes to avoid any fungal and bacterial contamination. Finally, the water was evaporated under low pressure using a rotary evaporator, and the residues were collected and stored until further use. ZnO-NPs were prepared using our previous method [15,19]. In brief, 100 mL of A. nilotica aqueous extract was mixed with 5 g of Zn(NO3)2. The mixture was transferred to a stirrer hotplate at 80°C for 2 h. A brown cloud appeared which was then filtered and incubated in an oven for 24 h at 60°C. The resulting brown spongy paste was burned in a furnace oven at 400°C for 2 h to obtain the white powder of ZnO-NPs, which indicated the reduction of Zn(NO3)2 to ZnO-NPs. The following procedures were used to characterize the synthesized ZnO-NPs to confirm their formation, stability, and important functional groups and to analyze their shapes and sizes. UV-vis spectroscopy (UV-1800; Shimadzu UV Spectrophotometer, Kyoto, Japan) was used to verify the presence of the nanoparticles, which were detected in the wavelength range of 100–800 nm. The surface functional groups were investigated and identified by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) (Perkin Elmer, Spectrum BX, Waltham, UK) in the range of 400–4,000 cm−1. The structure, crystalline nature, and composition of synthesized ZnO-NPs were analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD). The formation, symmetry, size, and shape of the nanoparticles were examined in powdered form using a Brucker-Discover D8 X-ray diffractometer operating (CUK-alpha, Sangamon Ave, Gibson, USA) at a scan speed of 2°·min−1 within the range of 10–100°. TEM JEM-2100F (JEOL Ltd, Peabody, MA, USA) and SEM (JEOL model, JSM-761OF, Tokyo, Japan) were used to study the surface, shape, size, and distribution of ZnO-NPs.

2.2 Evaluation of the antibacterial activity of ZnO-NPs and A. nilotica against CRKP using agar well diffusion method, MIC, and MBC

Two samples of CRKP were obtained from the microbiology department, King Khalid University Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia and identified using the VITEK 2 system, version 08.01. In addition, K. pneumonia (ATTC700603) was obtained from the microbiology department, College of Basic Medical Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Agar well diffusion method was first used for the preliminary screening of the activities of A. nilotica aqueous extract and ZnO-NPs20. MIC and MBC were determined using the methodology of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute to confirm the activities of the tested plant extract and nanoparticles [21].

2.3 Preparation of tested bacteria for SEM and TEM

The morphological alterations of the bacterial samples after treatment with ZnO-NP and A. nilotica aqueous extract were evaluated by SEM. Two test tubes were filled with 1 mL of CRKP suspension (108 CFU·mL−1) and mixed with either 1 mL of ZnO-NPs (Tube 1) or 1 mL of A. nilotica aqueous extract (Tube 2) to obtain a final concentration of 0.5 mg·L−1. The test tubes were incubated overnight at 37°C. Two controls – one with only CRKP in the medium (negative control) and the other with KPC treated with colistin (positive control) – were individually cultured in a salt-free lysogeny broth medium. Afterward, the samples underwent rinsing with normal saline and centrifugation at 1,500g. Following fixation with 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4°C for 2 h, they were washed with a phosphate buffer (pH = 7.2). Subsequently, the samples were post-fixed using 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated through an increasing ethanol series, and subjected to critical point drying [10]. Coating with Au–Pd (80:20) was performed using a Polaron E5000 sputter coater, manufactured by Quorum Technologies in Laughton, UK. The samples were examined with a SE detector at an accelerating voltage of 25 kV in an FEI Quanta 250 [22–24]. For the TEM samples, the same buffers and dehydration protocol used in SEM samples were employed, followed by dehydration with a graded acetone series and embedding in epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections were cut on formvar-coated grids and dyed with 3% uranyl acetate. The samples were observed under a JEM-2100F microscope (JEOL Ltd, Peabody, MA, USA) [24].

2.4 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis for the ZI, MIC, and MBC for the synthesized ZnO-NPs, A. nilotica, and colistin was represented as mean ± SD, and the level of significance is set at P < 0.05. The data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA based on different treatments followed by Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. Statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism, Ver. 10.00 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

3 Results

3.1 Characterization of ZnO-NPs

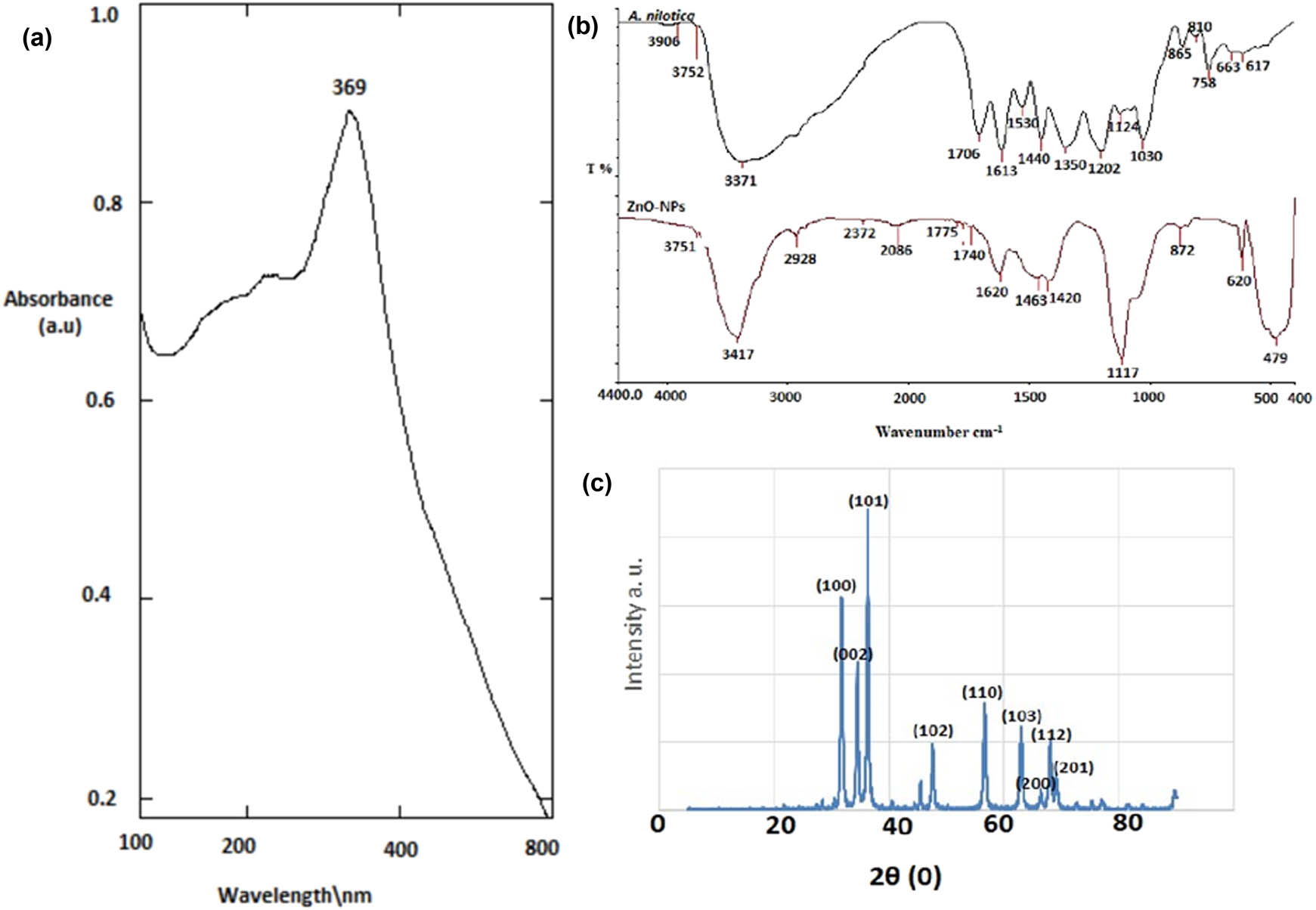

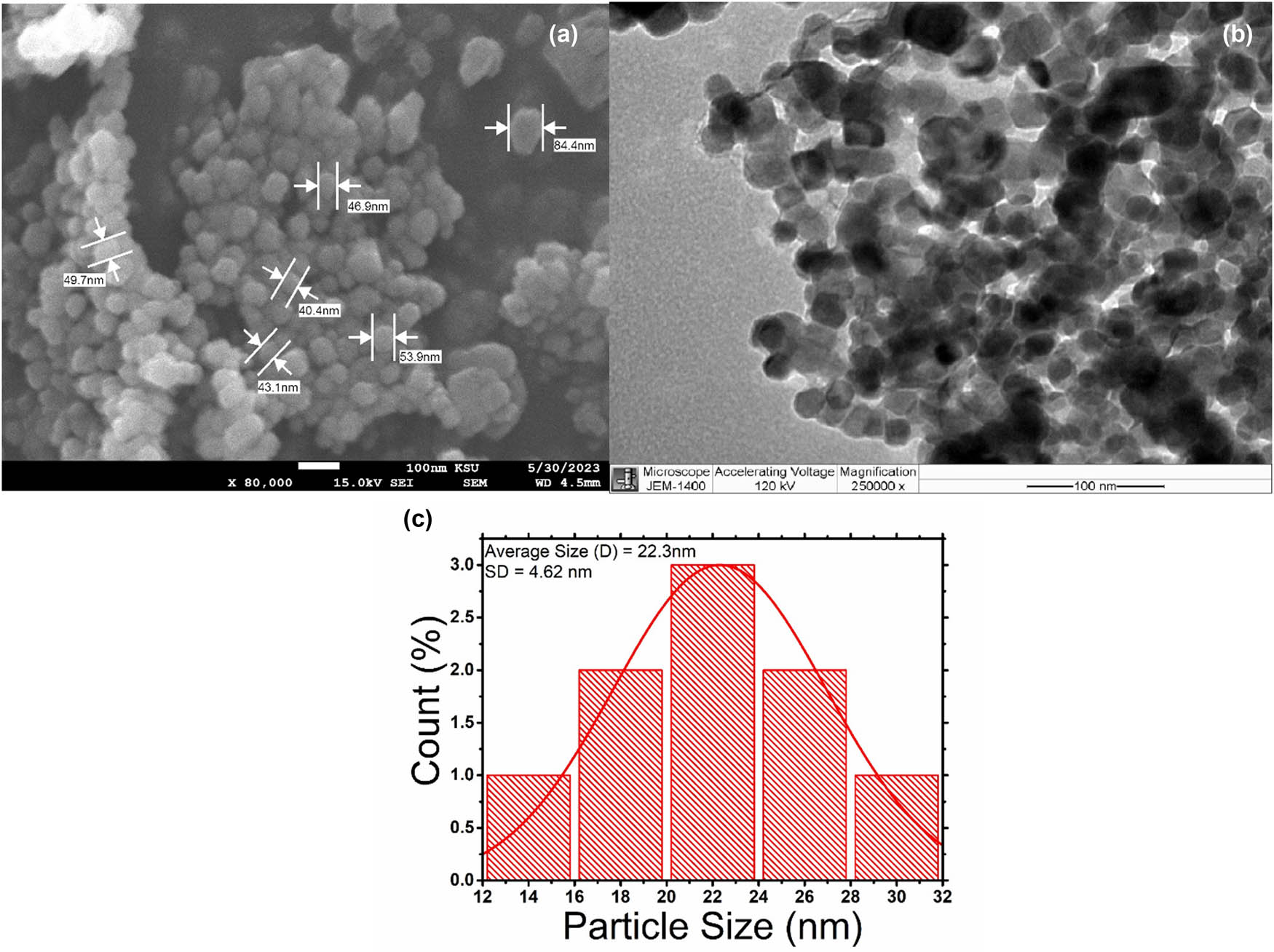

In this study, the aqueous extract of A. nilotica was used to produce ZnO-NPs by applying the green synthesis method previously modified by our research group [23]. As shown in the UV-vis spectra of ZnO-NPs in Figure 1a, a strong and high peak located at 369 nm was observed. The FTIR spectra obtained from the synthesized ZnO-NPs are presented in Figure 1b and Table 1. FTIR spectroscopy is an effective method to identify specific chemical bonds or functional groups present in plant extracts or nanoparticles. The FTIR analysis indicated that the alkene (C═O), nitro carboxylic acid (N–O), alcohol (O–H), fluoro compound (C–F), amin (C–N), and sulfoxide (S═O) groups in the aqueous extract of A. nilotica fruits were mainly responsible for the reduction of Zn(NO3)2 to ZnO-NPs. In the FTIR spectrum of the biosynthesized ZnO-NPs, strong carbon dioxide, esters, and acid halide (O═C–O) were observed in the vibration band at 2,372 cm−1. However, the stretching vibration bands of C═O, N–H, C–H, and C–O groups at 1,799, 1,620, 1,463, and 1,117 cm−1, respectively, exhibited five peaks in ZnO-NPs. A shift to 479 cm−1 was observed for the ZnO group due to the interaction of Zn(NO3)2 ions with the plant extract’s functional groups. The extract’s bands at 3,906, 3,752, 3,371, and 758 cm−1 and the ZnO-NPs’ bands at 3,751, 3,417, 2,928, and 872 cm−1 were ascribed to the methyl, methylene, and methoxy groups, respectively. The extract and nanoparticles shared a number of potent groups, including the bands at 1,420 and 1,440 cm−1 attributed to the hydroxyl group’s OH stretching vibration. This finding suggests the presence of alcoholic, phenolic, and acidic compounds or even water (Figure 2b). The purity and crystalline structure of ZnO-NPs were assessed using XRD. The XRD spectrum revealed three prominent diffraction peaks at 2θ values of 31.727°, 34.379°, and 36.235°, corresponding to the (100), (002), and (101) crystallographic planes. Additional peaks were observed for the (102), (110), (103), (200), and (112) planes. These patterns confirm the presence of pure ZnO with a hexagonal wurtzite crystal structure (Figure 1c). The morphology (size and shape) and distribution of ZnO-NPs were studied using SEM and TEM. The ZnO-NPs made from A. nilotica fruits showed an uneven round structure with a size range of 40–85 nm as indicated by the SEM images in Figure 2a. Agglomerated nanoparticles were also observed on the SEM image. Figure 2b shows TEM image of the produced ZnO-NPs at scales of 25 and 50 nm. Spherical ZnO particles were visible in the TEM photos. Figure 2c displays the average particle size distribution histogram as measured by TEM (22.3 nm).

(a) UV-vis spectra of ZnO-NPs, showed absorbance peak at 369 nm which confirm the formation of ZnO-NPs. (b) FTIR to detect the chemical functional group in ZnO-NPs and the aqueous extract of A. nilotica. (c) XRD of ZnO-NPs.

FTIR bands of A. nilotica aqueous extract and ZnO-NPs

| Peak assignment; functional group | A. nilotica (cm−1) | Peak assignment; functional group | ZnO-NPs (cm−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strong alkyl group (C–H) | 3,906, 3,752, 3,371, and 758 | Strong alkane group (C–H) | 3,751, 3,417, 2,928 and 872 |

| Medium carboxylic acid (O–H) | 1,420 | Medium carboxylic acid (O–H) | 1,440 |

| Strong and medium group of alkene, respectively (C═C) | 865 and 810 | Weak alkene (C═C) | 2,086 |

| Strong halogen group (C–Br) | 663 and 617 | Strong halogen group (C–Br) | 620 |

| Strong ketone (C═O) | 1,706 | Strong carbon dioxide (O═C–O) | 2,372 |

| Medium conjugated alkene (C═O) | 1,613 | Strong acid halide, strong conjugated acid halide, and strong esters, respectively (C═O) | 1,799, 1,775 and 1,740 |

| Strong nitro compound carboxylic acid (N–O–S) | 1,530 | Medium amine (N–H) | 1,620 |

| Zinc oxide (ZnO) | 479 |

(a) SEM to study the size, shape, and distribution of ZnO-NPs. (b) TEM to study the size, shape, and distribution of ZnO-NPs. (c) Average particle size of ZnO-NPs determined by TEM.

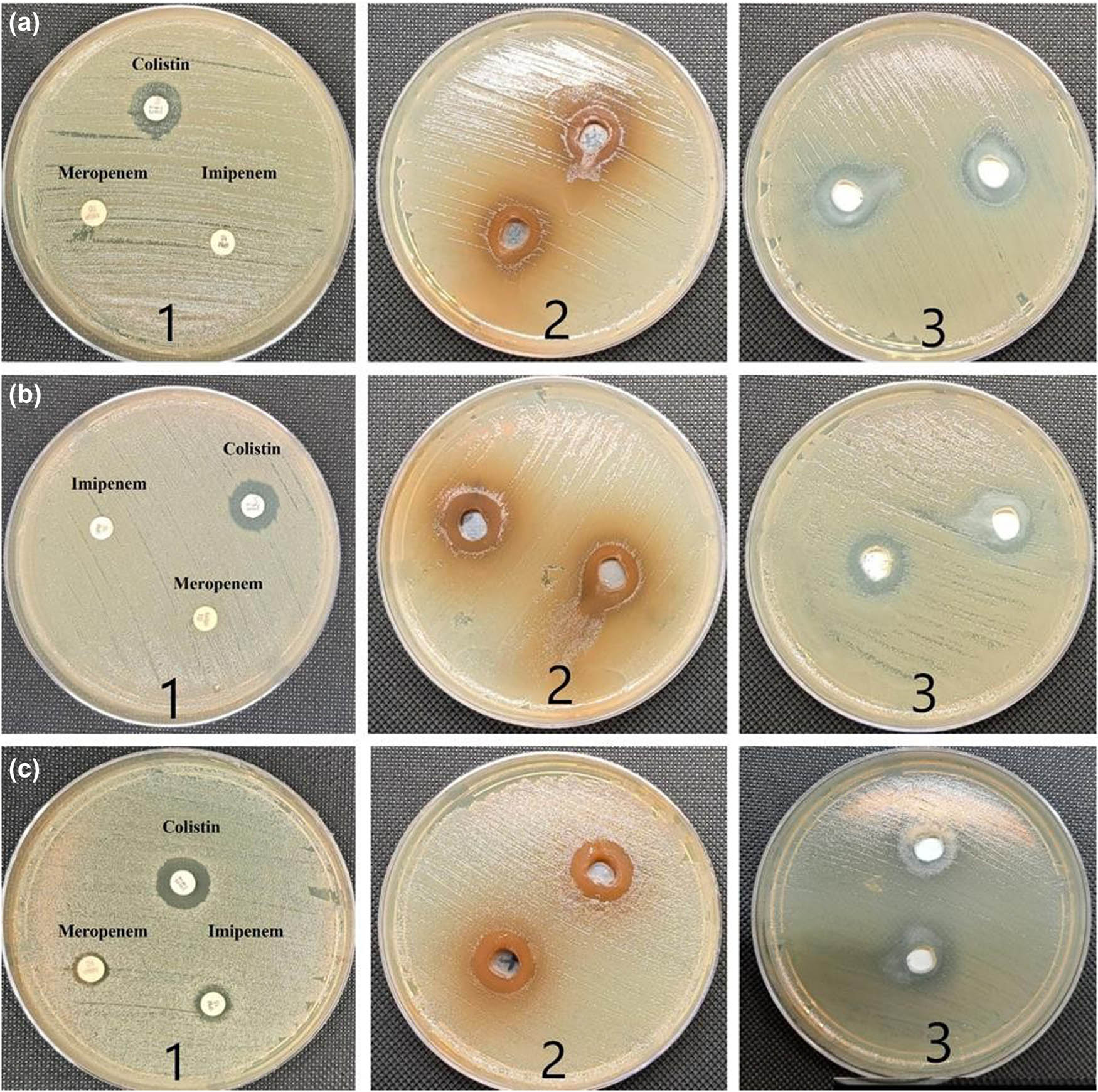

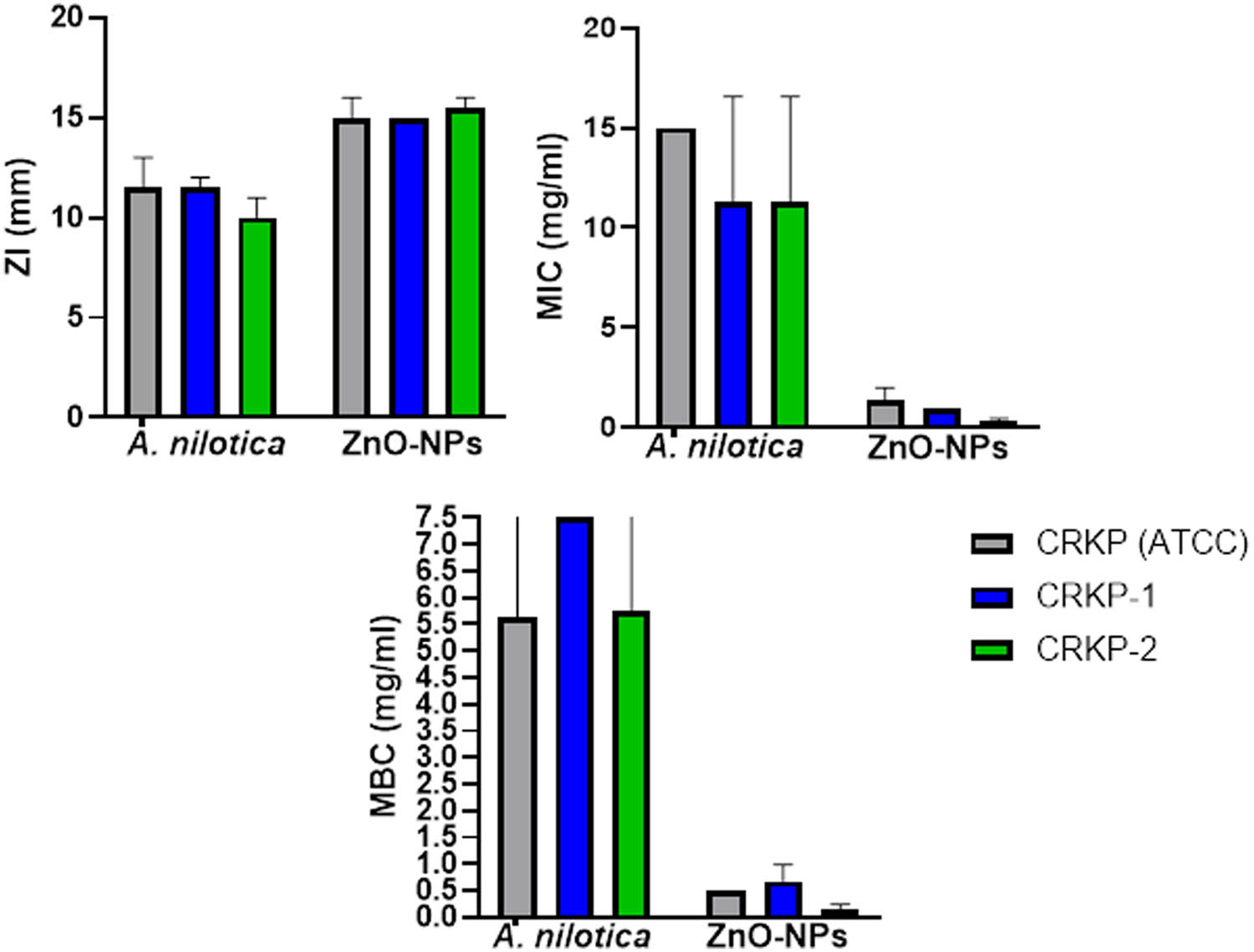

3.2 Activities of A. nilotica aqueous extract and ZnO-NPs against CRKP

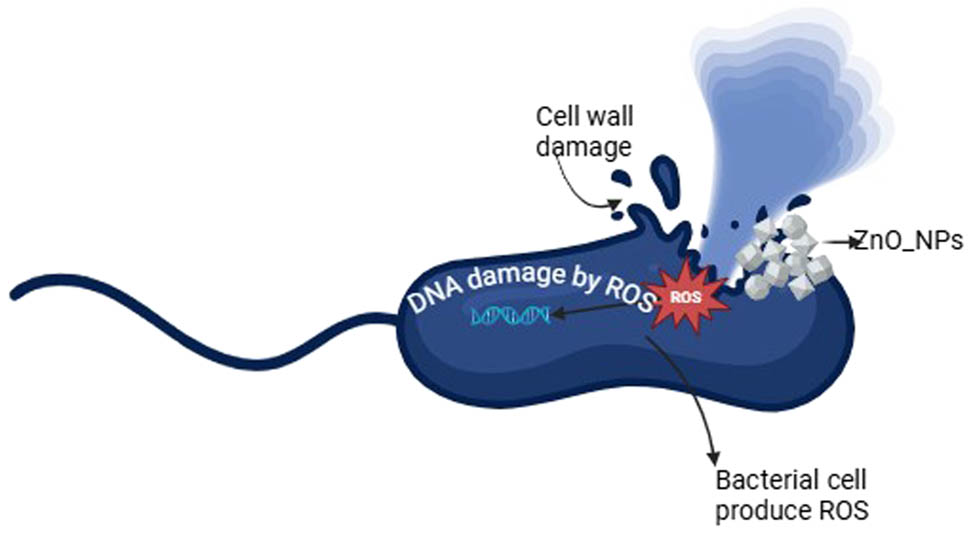

Numerous studies have been conducted to assess the antibacterial activity of ZnO-NPs and A. nilotica aqueous extract; however, the novel approach in this work is to examine the effects on CRKP and discover how they affect cell morphology. Figures 3 and 4 and Table 2 show that ZnO-NPs showed the most potent antimicrobial activity compared to colistin, meropenem, imipenem, and plant extract. According to the size of the ZI, the potency of the antimicrobial activity is often classified as sensitive, intermediate, and resistant. The bacterium is regarded as sensitive to the antibiotic if the observed ZI is larger than or equal to the size of the standard zone (16 mm). In contrast, the microorganism is regarded as resistant if the observed ZI is lower than 10 mm or has intermediate sensitivity if the ZI is between 10 and 16 mm (Figures 3 and 4) [25]. All the tested bacteria were susceptible to ZnO-NPs, exhibited an intermediate ZI to A. nilotica, and were resistant to colistin. After measuring the ZI, we determined the lowest dose that can inhibit the bacterial growth (MIC) and the concentration that kills the bacterial growth (MBC). As shown in Table 2 and Figure 4, the A. nilotica aqueous extract showed intermediate MIC for all the tested bacteria (mean for ATCC is 11 ± 4.6 mg·mL−1 and the clinical samples were 9.58 ± 4.6 and 8.916 4.23 mg·mL−1, respectively). Meanwhile, the MBC of A. nilotica revealed against the standard CRKP (9.29 ± 4.5 mg·mL−1) and (8.67 ± 3.9 and 7.81 ± 3.8 mg·mL−1) against the clinical isolates. The significant results were reported by ZnO-NPs, which showed 1.35 ± 0. 45, 0.9 ± 0, and 0.3 ± 0.1 mg·mL−1 MIC against ATCC, CRKP-1, and CRKP-2, respectively; and the MBC was 0.5 ± 0, 0.68 ± 0.23, and 0.16 ± 0.06 mg·mL−1, respectively. All the tested bacteria were resistant to colistin (MIC more than 16 mg·mL−1 and MBC more than 64 mg·mL−1). Figure 5 presents the antibacterial mode of action of ZnO-NPs against CRKP cells involving the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). These ROS induce oxidative stress in bacterial cells, damaging nucleic acids and proteins, ultimately leading to bacterial cell death. Additionally, ZnO-NPs adhere to bacterial cell membranes, disrupting their integrity and causing membrane damage, which further contributes to cell death.

(a1) and (c1) ZI of imipenem, meropenem, and colistin antibiotics against CRKP, which showed no inhibition zone with meropenem and imipenem and weak inhibition zone with colistin. (a2) and (c2) A. nilotica aqueous extract against CRKP (ATCC) at 7.5 mg·mL−1 concentration showed wide inhibition zone with both clinical samples of colistin-resistant bacteria. (a3 and c3) ZnO-NPs against CRKP at concentration of 7.5 mg·mL−1 showed a wide inhibition zone against both tested clinical isolates. (b1–3) ZI of imipenem, meropenem, colistin, A. nilotica aqueous extract, and ZnO-NPs against CRKP ATCC 700603 which revealed good susceptibility with both ZnO-NPs and A. nilotica extract, while weak response to the commercial antibiotics used.

ZI, MIC, and MBC of A. nilotica, ZnO-NPs, and colistin against CRKP-1, CRK-2, and ATCC 700603.

ZI, MIC, and MBC of A. nilotica, ZnO-NPs, and colistin against CRKP-1, CRK-2, and ATCC 700603 (mean ± std deviation)

| Antimicrobial | Tests | CRKP (ATCC) | CRKP-1 | CRKP-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colistin | ZI (mm) | 0 ± 0 | 8.5 ± 0.707 | 7 ± 0 |

| MIC (mg·mL−1) | 2 ± 0 | >16 | >16 | |

| MBC (mg·mL−1) | 1 ± 0 | >64 | >64 | |

| A. nilotica | ZI (mm) | 11.5 ± 1.5 | 11.5 ± 0.5 | 10 ± 1 |

| MIC (mg·mL−1) | 11 ± 4.6 | 9.58 ± 4.6 | 8.916 4.23 | |

| MBC (mg·ml−1) | 9.29 ± 4.5 | 8.67 ± 3.9 | 7.81 ± 3.8 | |

| ZnO-NPs | ZI (mm) | 9.76 ± 4.56 | 9.23 ± 4.24 | 8.63 ± 4.39 |

| MIC (mg·mL−1) | 1.35 ± 0. 45 | 0.9 ± 0 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | |

| MBC (mg·mL−1) | 0.5 ± 0 | 0.68 ± 0.23 | 0.16 ± 0.06 |

ZnO-NPs activity mechanism. The mechanism of ZnO-NPs on CRKP cell. It is represented by ZnO-NPs when generating ROS, which can cause oxidative stress in bacterial cells. ROS damage nucleic acids and proteins, leading to bacterial cell death. ZnO-NPs adhere to bacterial cell membranes and disrupt their integrity. This interaction can lead to membrane damage and cell death.

3.3 Evaluation of the effects of A. nilotica aqueous extract and ZnO-NPs on the morphology of CRPK cells

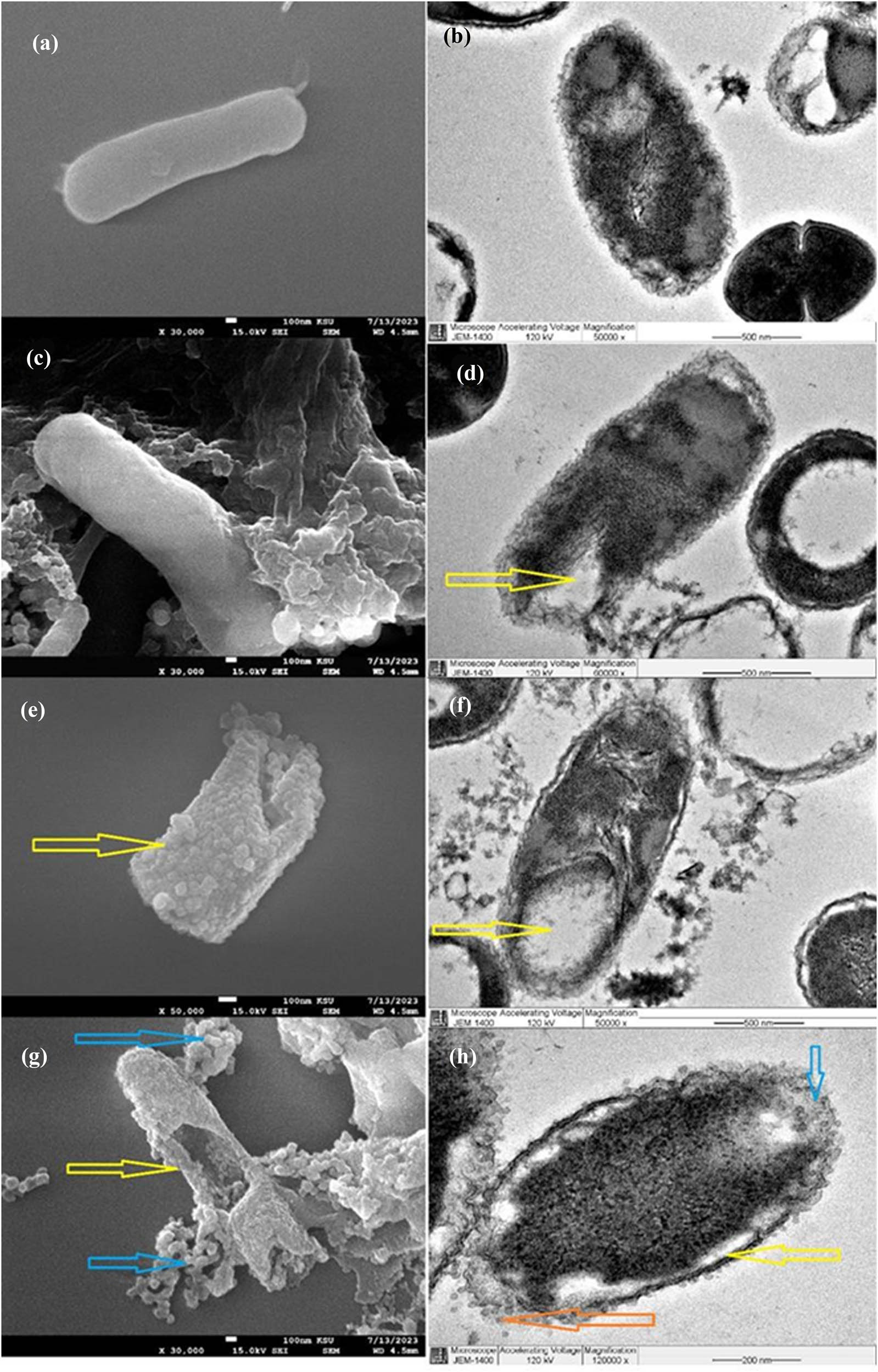

After the effects of A. nilotica and ZnO-NPs on CRKP were examined, we discovered that both treatments showed a promising antibacterial activity that is greater than that of commercial antibiotics. We then verified this result by confirming the morphological effect on the bacterial cell using SEM and TEM. Figure 6 illustrates these outcomes. First, the control negative, which was a typical bacterial cell (Figure 6a and b), showed a normal rod-shaped cell with smooth surface outlines, integral and thick cell walls and cell membranes, and well-distributed intracellular cytoplasm without damage. Second, the SEM images of CRKP treated with colistin as shown in Figure 6c display that the bacterial cell was only mildly abnormal with few bulges on the bacterial surface. As illustrated in the TEM photos of bacterial cells treated with colistin in Figure 6d, some cytoplasm had escaped from the cell. This phenomenon may be related to the bulges observed in the SEM images. Third, Figure 6e and f shows the effects of A. nilotica aqueous extract on CRKP. Major changes occurred in the bacterial cell as shown by a reduction in size and a switch from a rod- to a cylinder-shaped bacterial form. In addition, the bacterial surface developed roughness (Figure 6e) and a thin, unclear cell wall and membrane, together with significant surface shrinkage and a fully ruptured cell wall (Figure 6f). Finally, the synthesized ZnO-NPs on CRKP showed remarkable effects as revealed in the SEM images (Figure 6g). The aggregation of ZnO-NPs surrounding the bacterial cell resulted in extensive damage to the cell center, leading to bacterial cell wall destruction and cytoplasmic leaking. On the side of the TEM image, the cell wall appeared thin and the cytoplasm escaped from the cell, resulting in cell integrity disruption and cell death (Figure 6h). Overall, the present study findings suggest that an eco-friendly drug could be stronger than a commercial drug. The ZnO-NPs produced from A. nilotica have promising antibacterial properties, but further research is required before they can be used to treat colistin-resistant bacteria.

(a) and (b) SEM images show normal rod-shaped cell with smooth surface and well-distributed intracellular cytoplasm without any damage. (c) SEM image of the bacterial cell treated by colistin; the bacterial cell surface has a slight curvature, which is different from the typical flat surface of a normal bacterial cell. (d) TEM image for CRKP treated by colistin; the cytoplasm has escaped from the cell (yellow arrow). (e) SEM image of CRKP cells treated by A. nilotica aqueous extract; the yellow arrow revealed how the bacterial cell became rough with reduced cell size and shape (change from rod shape into cylinder shape). (f) TEM image of CRKP cells treated by A. nilotica aqueous extract; the cell wall and membrane thinned with rupture in some parts, and the intracellular cytoplasm gathered into a network with nodes accompanied by cell cavities (yellow arrow). (g) SEM image of ZnO-NPs against CRKP showing significant cell alterations represented by the complete damage of the cell wall (yellow arrow), leading to cell rupture and death; the blue arrows show ZnO-NPs accumulated around the bacterial cell. (h) TEM image of ZnO-NPs against CRKP revealing a clear area of cell wall disruptions (blue arrow); the cytoplasm has escaped from the cell (orange arrow) and the cell wall has thinned (yellow arrow).

4 Discussion

The frequent use of colistin to treat CRKP infections has led to an increase in the number of resistant bacteria. Recent studies have focused on finding new strategies for fighting CRKP, including the production of new pharmaceuticals, repurposing of existing treatments [26,27], use of colistin in combination with other medications [28,29], a nano-based method, photodynamic therapy [30], and a phage-based approach [5]. The present work aimed to determine the effect of A. nilotica aqueous extract and ZnO-NPs synthesized using the same plant on CRKP. The UV-vis spectra indicated a clear peak in the usual range wavelength (300–390 nm) [19,23,24,31,32]. The produced nanoparticles displayed good characterization (369 nm), confirming the formation of ZnO-NPs. These results corroborated with previous findings on the green synthesis of ZnO-NP [12,17,19,23,33]. FTIR spectroscopy was then applied to assess the chemical characteristics of ZnO-NPs. The results showed that the functional groups in A. nilotica did not differ significantly from those in ZnO-NPs. Only one group was detected, the strong nitro compound carboxylic acid (N–O–S), in A. nilotica aqueous extract. This is mainly responsible for the creation of ZnO-NPs. Owing to its high percentages of alkene, carboxylic acid, carbon dioxide, ketone, and halogen groups, the plant extract contains tannins, flavonoids, alkaloids, fatty acids, and polysaccharides, which are responsible for the reducing action on Zn(NO3)2 and help stabilize the growth of the nanoparticles [8,34,35]. At the tail of the ZnO-NP curve, the ZnO group appeared at 479 cm−1. This finding (450–490 cm−1) was consistent with previous studies [19,37,38].

From the XRD spectra, we observed that the intensities of the (100), (002), and (101) peaks were stronger than the other peaks. This suggests that these crystal planes are preferential for ZnO-NPs, consistent with the findings of Chan and others [10,36]. The XRD results were encouraging, as they closely matched previous reports [10,37,38], although they differed from Aldalbahi et al.s’ [39] work. Our data revealed a crystalline round and hexagonal structure for the ZnO-NPs, similar to the results reported by Liu et al. [38] and Malviya et al. [40]. These findings indicate that the ZnO-NPs formed are pure and possess an excellent crystalline structure, evident from their well-defined and strong diffraction peaks.

The most important results are the SEM and TEM photos showing the size, shape, and distribution of the nanoparticles. The images showed good distribution, no aggregation, irregular to spherical particle shape, and an average size of 22.3 nm. These findings were also in accordance with our earlier observations and were similar to the results when ZnO was synthesized with the help of Aspergillus niger and A. nilotica [3,23]. These outcomes supported the results of many researchers who synthesized ZnO-NPs by several methods [41,42]. As mentioned in the introduction, scientists are exploring the production of nanoparticles from plant extracts due to their small size, large surface area, and relevant physical properties. These nanoparticles are suitable for applications in medical sciences, and they offer the advantage of being cost-effective and environmentally friendly. The ZI’s results showed that all the tested bacteria exhibited susceptibility to the synthesized nanoparticles and the tested antibiotics and moderate susceptibility to A. nilotica aqueous extract. A possible explanation for this result is that synthesized nanoparticles have good chemicals (have more functional groups that bind to the bacterial cell wall’s protein and kill the bacteria, are stable for a long time, and easily dissolve in water and other solvents) and physical properties (have a small size of less than 100 nm, making them suitable as antimicrobial compounds, and low accumulation) that make them more potent than the plant extract. The lowest MIC for CRKP was achieved by ZnO-NPs (0.2 mg·mL−1), followed by A. nilotica aqueous extract (15 mg·mL−1). These results can be attributed to the stronger antibacterial properties of ZnO-NPs compared to A. nilotica [3,23]. These findings are consistent with Chan and others who found that of ZnO-NPs demonstrated significant potential in inhibiting the growth of various bacteria, including Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC BAA-1026), Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633), E. coli (ATCC 25922), and K. pneumoniae (ATCC 13883). The MIC followed a decreasing order: S. aureus = B. subtilis (15.63 μg·mL⁻¹) > E. coli (62.50 μg·mL⁻¹) > K. pneumoniae (125.00 μg·mL⁻¹) [36].

Our research group previously reported the MIC results of synthesized nanoparticles when tested against the porin protein of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumonia using molecular docking and in vitro experiments. It is found that ZnO-NPs have the strongest hydrogen bond with the bacteria’s protein compared with imipenem, meropenem, and cefepime. This bond plays a crucial role in the binding of proteins to ligands [17]. In the present work, the CRKP cells exhibited morphological alterations in their cell surface and internal organs as discovered by SEM and TEM, respectively. Current study results show that compared with normal bacterial cells, the samples treated by ZnO-NPs and A. nilotica aqueous extract showed reduced cell size and shape, membrane damage, bacterial surface roughness and shrinkage, and a fully ruptured cell wall. Meanwhile, the TEM photos showed the following alterations: cell wall disruption leading to cytoplasmic loss, which eventually resulted in cell death. The ZnO-NP-treated cells exhibited the most remarkable cell changes. These results reflect the findings of several researchers, who also found that the bacterial cells treated with nanoparticles exhibit the same changes [14,41,42]. The various modifications observed in CRKP cells supported the results from the earlier studies which reported that ZnO-NPs generate ROS, which can cause oxidative stress in bacterial cells. ROS damage lipids, nucleic acids, and proteins, leading to bacterial cell death. ZnO-NPs adhere to bacterial cell membranes and disrupt their integrity. This interaction can lead to membrane damage and cell death [43,44].

These findings may help further understand how antimicrobial agents inhibit or kill microorganisms. While the study provides promising results regarding the antimicrobial activity of A. nilotica aqueous extract and ZnO-NPs against co CRKP, it is important to acknowledge that this research is limited to in vitro experiments. Further investigations, including in vivo studies, toxicity, adsorption, and other side effects of A. nilotica extract and ZnO-NPs on live cells, are necessary to validate the potential therapeutic applications of these natural products in preventing CRKP infections.

5 Conclusion

This study aimed to determine the morphological alteration of CRKP cells treated by green-synthesized ZnO-NPs and A. nilotica aqueous extract. ZnO-NPs were produced using the green synthesis method modified by our research group. The characterization of ZnO-NPs presented a strong peak at 369 nm when tested with UV-vis spectra. FTIR analysis revealed functional groups (alkene, nitro carboxylic acid, alcohol, etc.) responsible for reducing Zn(NO₃)₂ to ZnO-NPs. XRD confirmed the hexagonal wurtzite crystal structure of pure ZnO. SEM images displayed uneven round ZnO-NPs with a size range of 40–85 nm and the TEM images showed spherical ZnO particles with an average size of 22.3 nm. ZnO-NPs exhibited potent antimicrobial activity against CRKP including the ZI tests indicating sensitivity to ZnO-NPs, intermediate response to A. nilotica extract, and resistance to imipenem, meropenem, and colistin. The MIC and MBC values were determined for bacterial growth inhibition which detected that ZnO-NPs had the lowest MIC (0.2 mg·mL−1). The study of the tested bacterial treated cells with SEM and TEM confirmed the following outcomes: The control group exhibited normal rod-shaped bacterial cells with intact cell walls and membranes, colistin-treated CRKP cells showed mild abnormalities and cytoplasmic leakage, A. nilotica extract caused significant changes, including size reduction and altered cell shape, and ZnO-NPs led to extensive damage, disrupting cell walls and causing cytoplasmic leakage. In general, eco-friendly ZnO-NPs from A. nilotica hold potential for treating colistin-resistant bacteria, pending further research and both A. nilotica and ZnO-NPs demonstrated promising antibacterial activity surpassing that of commercial antibiotics.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their profound gratitude to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University and King Saud University for their invaluable support toward this research project.

-

Funding information: Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2024R357), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contributions: Abeer Salem Aloufi and Ehssan Moglad: formal analysis; Rasha Elsayim and Basmah Almaarik: methodology; Fatimah Saleh Al-Khattaf, Rizwan Ali, and Rasha Elsayim: investigation and writing original draft; Fatimah Saleh Al-Khattaf, Halah Salah Mohammed Abdalaziz, Mohammed Hassan Ibrahim Alaaullah, Abeer Salem Aloufi, Saida Sadek Ncibi, and Nihal Almuraikhi: conceptualization, supervision, project administration, and writing – review and editing; Malek Hassan Ibrahim Alaaullah and Rizwan Ali: validation; Saida Sadek Ncibi, Nihal Almuraikhi, and Abeer Salem Aloufi: funding acquisition.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Rojas LJ, Salim M, Cober E, Richter SS, Perez F, Salata RA, et al. Colistin resistance in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: laboratory detection and impact on mortality. Clin Infect Dis 2017;64:711–8.10.1093/cid/ciw805Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Munoz-Price LS, Poirel L, Bonomo RA, Schwaber MJ, Daikos GL, Cormican M, et al. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(9):785–96. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70190-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Rasha E, Alkhulaifi MM, AlOthman M, Khalid I, Doaa E, Alaa K, et al. Effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using Aspergillus niger on carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumonia in vitro and in vivo. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11(Nov):1–11.10.3389/fcimb.2021.748739Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Rani R, Sharma D, Chaturvedi M, JP Y. Green synthesis, characterization and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles of endophytic fungi Aspergillus terreus. J Nanomed Nanotechnol. 2017;8(4):100457.10.4172/2157-7439.1000457Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Petrosillo N, Taglietti F, Granata G. Treatment options for colistin resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: present and future. J Clin Med. 2019;8.10.3390/jcm8070934Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Marchaim D, Chopra T, Pogue JM, Perez F, Hujer AM, Rudin S, et al. Outbreak of colistin-resistant, carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in metropolitan Detroit, Michigan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(2):593–9.10.1128/AAC.01020-10Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Alqasim A. Colistin-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in Saudi Arabia: a literature review. J King Saud Univ - Sci. The Author; 2021;33:101610. 10.1016/j.jksus.2021.101610.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] State J. Antibacterial effect of Acacia nilotica and Acacia senegalensis fruit extracts on Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhi. FUTY J Environ. 2020;14(2):1–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Sadiq MB, Tarning J, Cho TZA, Anal AK. Antibacterial activities and possible modes of action of Acacia nilotica (L.) Del. against multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Molecules. 2017;22(1):47.10.3390/molecules22010047Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Rasha E, Monerah A, Manal A, Rehab A, Mohammed D, Doaa E. Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from Acacia nilotica (L.) extract to overcome carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Molecules. 2021;26(7):1919.10.3390/molecules26071919Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Elamary RB, Albarakaty FM, Salem WM. Efficacy of Acacia nilotica aqueous extract in treating biofilm-forming and multidrug resistant uropathogens isolated from patients with UTI syndrome. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–14. 10.1038/s41598-020-67732-w.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Dulo B, Phan K, Githaiga J, Raes K, De Meester S. Natural quinone dyes: a review on structure, extraction techniques, analysis and application potential. Waste and biomass valorization. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer Science and Business Media B.V.; Vol. 12, 2021. p. 6339–74.10.1007/s12649-021-01443-9Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Aminnezhad S, Maghsoudloo M, Bagheri R, Aliakbari S. Micro nano bio aspects anticancer, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective effects of bisdemethoxycurcumin: micro and nano facets. Micro Nano Bio Asp. 2023;2023(4):17–24. 10.22034/mnba.2023.416625.1046.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Alavi M, Hamblin MR, Kennedy JF. Nano micro biosystems antimicrobial applications of lichens: secondary metabolites and green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: a review. Nano Micro Biosyst. 2022;2022(1):15–21. 10.22034/nmbj.2022.159216.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Alshareef BB, Alaib MA. Investigation of allelopathic potential of Acacia nilotica L. EPH – Int J Appl Sci. 2019 Mar;5(1):24–9.10.53555/eijas.v5i1.121Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Omer Abdalla K. Biochemistry, medicinal properties & toxicity of Acacia nilotica fruits. Biomed Res Clin Rev. 2021 Feb;3(2):1–6.10.31579/2692-9406/040Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Elsayim R, Aloufi AS, Modafer Y, Eltayb WA, Alameen AA, Abdurahim SA. Molecular dynamic analysis of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumonia’s porin proteins with beta lactam antibiotics and zinc oxide nanoparticles. Molecules. 2023;28(6):2510.10.3390/molecules28062510Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Zowawi HM, Sartor AL, Balkhy HH, Walsh TR, Al Johani M, Aljindan RY, et al. Molecular characterization of carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council: dominance of OXA-48 and NDM producers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(6):3085–90.10.1128/AAC.02050-13Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Dash KK, Deka P, Bangar SP, Chaudhary V, Trif M, Rusu A. Applications of inorganic nanoparticles in food packaging: a comprehensive review. Polymers. 2022;14(3):521.10.3390/polym14030521Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Yagoub AEGA, Al-Shammari GM, Al-Harbi LN, Subash-Babu P, Elsayim R, Mohammed MA, et al. Antimicrobial properties of zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Lavandula pubescens shoot methanol extract. Appl Sci (Switzerland). 2022;12(22).10.3390/app122211613Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Farzana R, Iqra P, Shafaq F, Sumaira S, Zakia K, Hunaiza T, et al. Antimicrobial behavior of zinc oxide nanoparticles and β-lactam antibiotics against pathogenic bacteria. Arch Clin Microbiol. 2017;8(4):1–5.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Nagappan R. Evaluation of aqueous and ethanol extract of bioactive medicinal plant, Cassia didymobotrya (Fresenius) Irwin & Barneby against immature stages of filarial vector, Culex quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae). Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012;2(9):707–11.10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60214-7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Al-Saiym RA, Al-Kamali HH, Al-Magboul AZ. Synergistic antibacterial interaction between Trachyspermum ammi, Senna alexandrina mill and Vachellia nilotica spp. Nilotica extract and antibiotics. Pak J Biol Sci. 2015;18(3):115–21. 10.3923/pjbs.2015.115.121.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Kowalska-Krochmal B, Dudek-Wicher R. The minimum inhibitory concentration of antibiotics: methods, interpretation, clinical relevance. Pathogens. 2021;10(2):1–21.10.3390/pathogens10020165Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Kelly AM, Mathema B, Larson EL. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in the community: a scoping review. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017;50(2):127–34. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.03.012.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Kim KM, Choi MH, Lee JK, Jeong J, Kim YR, Kim MK, et al. Physicochemical properties of surface charge-modified ZnO nanoparticles with different particle sizes. Int J Nanomed. 2014;9:41–56.10.2147/IJN.S57923Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Hartmann M, Berditsch M, Hawecker J, Ardakani MF, Gerthsen D, Ulrich AS. Damage of the bacterial cell envelope by antimicrobial peptides gramicidin S and PGLa as revealed by transmission and scanning electron microscopy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(8):3132–42.10.1128/AAC.00124-10Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Cardozo VF, Oliveira AG, Nishio EK, Perugini MRE, Andrade CGTJ, Silveira WD, et al. Antibacterial activity of extracellular compounds produced by a Pseudomonas strain against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2013;12(1):1–8.10.1186/1476-0711-12-12Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Navarro MOP, Simionato AS, Pérez JCB, Barazetti AR, Emiliano J, Niekawa ETG, et al. Fluopsin c for treating multidrug-resistant infections: in vitro activity against clinically important strains and in vivo efficacy against carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Microbiol. 2019;10(Oct):1–12.10.3389/fmicb.2019.02431Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Goutam J, Kharwar RN, Tiwari VK, Singh R, Sharma D. Efficient production of the potent antimicrobial metabolite “Terrein” from the fungus Aspergillus terreus. Nat Prod Commun. 2020;15(3):1934578X20912863.10.1177/1934578X20912863Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Dizbay M, Tozlu DK, Cirak MY, Isik Y, Ozdemir K, Arman D. In vitro synergistic activity of tigecycline and colistin against XDR-Acinetobacter baumannii. J Antibiotics. 2010;63(2):51–3.10.1038/ja.2009.117Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Almutairi MM. Synergistic activities of colistin combined with other antimicrobial agents against colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates. PLoS One. 2022;17(7 July):1–8. 10.1371/journal.pone.0270908.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Domalaon R, Okunnu O, Zhanel GG, Schweizer F. Synergistic combinations of anthelmintic salicylanilides oxyclozanide, rafoxanide, and closantel with colistin eradicates multidrug-resistant colistin-resistant Gram-negative bacilli. J Antibiotics. 2019;72(8):605–16. 10.1038/s41429-019-0186-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Kalpana VN, Devi Rajeswari V. A review on green synthesis, biomedical applications, and toxicity studies of ZnO NPs. Bioinorg Chem Appl. 2018;2018:3569758.10.1155/2018/3569758Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Gunalan S, Sivaraj R, Rajendran V. Green synthesized ZnO nanoparticles against bacterial and fungal pathogens. Prog Nat Sci: Mater Int. 2012;22(6):693–700. 10.1016/j.pnsc.2012.11.015.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Chan Y B, Aminuzzaman M, Rahman MK, Win YF, Sultana S, Cheah SY, et al. Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study. Green Process Synth. 2024 Jan;13(1):20230251.10.1515/gps-2023-0251Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Bancroft JD, Layton C. Connective and other mesenchymal tissues with their stains Bancroft’s Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques. London: Elsevier; 2019. p. 153–75.10.1016/B978-0-7020-6864-5.00012-8Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Liu S, Long Q, Xu Y, Wang J, Xu Z, Wang L, et al. Assessment of antimicrobial and wound healing effects of Brevinin-2Ta against the bacterium Klebsiella pneumoniae in dermally-wounded rats. Oncotarget. 2017;8(67):111369–85.10.18632/oncotarget.22797Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Aldalbahi A, Alterary S, Ali Abdullrahman Almoghim R, Awad MA, Aldosari NS, Fahad Alghannam S, et al. Greener synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: characterization and multifaceted applications. Molecules. 2020;25(18):1–14.10.3390/molecules25184198Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Malviya S, Rawat S, Kharia A, Verma M. Medicinal attributes of Acacia nilotica Linn.- a comprehensive review on ethnopharmacological claims. Int J Pharm Life Sci. 2011;2(6):830–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Rao TN, Riyazuddin, Babji P, Ahmad N, Khan RA, Hassan I, et al. Green synthesis and structural classification of Acacia nilotica mediated-silver doped titanium oxide (Ag/TiO2) spherical nanoparticles: assessment of its antimicrobial and anticancer activity. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2019;26(7):1385–91. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2019.09.005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Senthilkumar SR, Sivakumar T. Green tea (Camellia sinensis) mediated synthesis of zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles and studies on their antimicrobial activities. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2014;6(6):461–5.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Alavi M, Yarani R. Nano micro biosystems ROS and RNS modulation: the main antimicrobial, anticancer, antidiabetic, and antineurodegenerative mechanisms of metal or metal oxide nanoparticles. Nano Micro Biosyst. 2023;2023:22–30. https://www.nmb-journal.com.Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Jiang S, Lin K, Cai M. ZnO nanomaterials: current advancements in antibacterial mechanisms and applications. Frontiers in Chemistry. Vol. 8. Lausanne, Switzerland: Frontiers Media S.A.; 2020.10.3389/fchem.2020.00580Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles