Abstract

In this study, tulsi and neem oils were used to effectively synthesise Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite utilising environmentally friendly methods. X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) methods were used to characterise the green synthesised nanocomposite. The triangle-spherical shaped nanoparticles (NPs) with an average size of 26–42 nm were shown by XRD and SEM investigations to be crystalline in Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite, respectively. Additionally, the dynamic light scattering histogram was used to quantify the size distribution of these NPs, and the results were consistent with those of the SEM picture, having an approximate element size of 28 nm. The Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite is reduced and stabilised as a result of functional groups present in acacia, and neem, and tulsi oils, as shown by FT-IR measurements. In a nutshell, this method offers a quick, affordable, and environmentally safe technique to create NPs without the use of potentially dangerous chemical agents.

1 Introduction

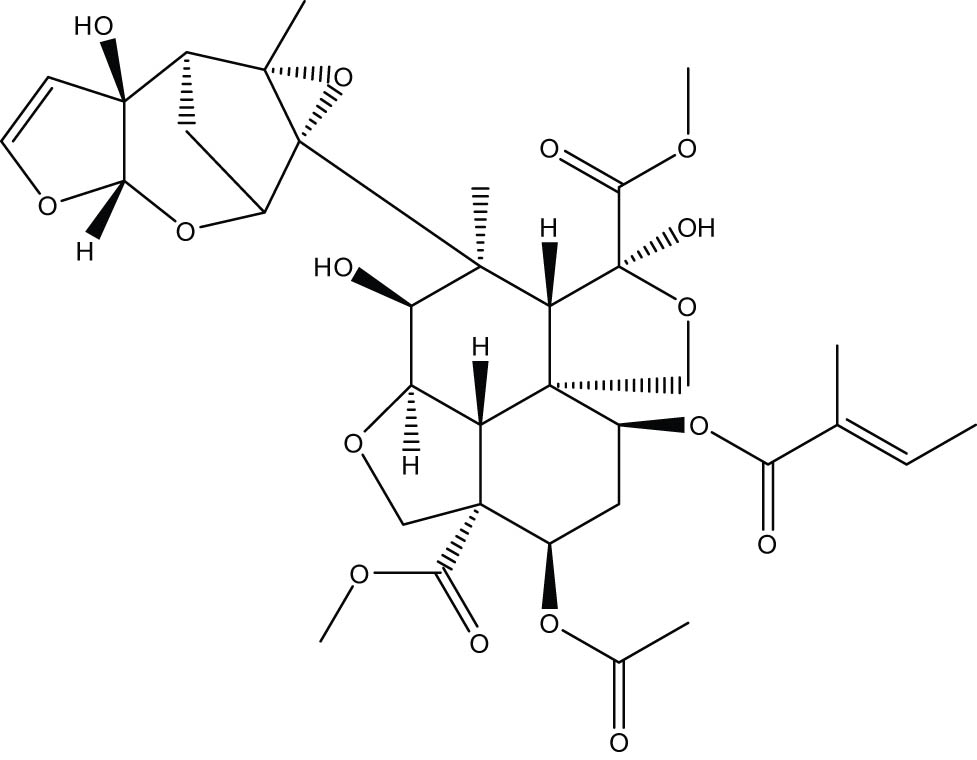

Biosynthesis of nanomaterials using medicinal plant oils has received much attention in recent years. The synthesis of nanomaterials by medicinal plant oils is more environmentally friendly and cost-effective than other synthesis methods, such as chemical reduction and physical methods [1,2]. Biosynthesis of nanomaterials has gained attention as an emerging feature of the interface between nanotechnology and biotechnology due to the increasing demand for environmentally friendly material manufacturing techniques [3]. The biosynthesis of inorganic materials, especially metal nanoparticles (NPs), using microbes and plants has received great attention [4,5,6]. “Green” synthesis strategies include the use of non-toxic materials, hazardous chemicals, biodegradable polymers, and eco-friendly solvents such as plant extracts These methods use extracts from various plant parts, microbial cells, and biopolymers, and are thus classified as green synthesis methods. The essential benefit of using plant extracts as biogenic sources of metallic synthesis is because they accelerate the reduction and stability of the NPs at room temperature and pressure (e.g., [7,8,9]). Due to its reputed therapeutic properties, tulsi (Ocimum sanctum), or Holy basil, from the family Lamiaceae, has been referred to as the “Queen of plants” and the “mother medicine of nature” [10]. Almost every component of the plant has been shown to have medicinal effects, making it one of the most revered and all-encompassing herbs utilised in Indian traditional medicine over the years [11]. Since Ocimum sanctum is used in several ways in traditional medicine; aqueous extracts from the leaves (naturally picked or even dried) are added to herbal teas or blended with various types of other herbs or honey to increase their therapeutic potency. Aqueous extracts of Tulsi have long been used to treat a variety of poisonings, stomach-aches, migraines, the parasite malaria, chronic inflammation, as well as heart conditions [12]. As medicines, painkillers, anti-emetics, antipyretics, stress relievers, inflammatory agents, as well as hepatoprotective, anti-asthmatic, hypoglycaemic, hypotensive, hypolipidemic, and immuno-modulatory agents, oils obtained from Ocimum sanctum as well as its leaves are considered to have a number of beneficial properties [12,13]. Due to the presence of vital or essential oil, which is mostly concentrated in the leaf of tulsi, the plant has a distinctive fragrant scent. The primary constituents of this aromatic volatile oil include phenols, terpenes, and aldehydes [14]. Fixed oil is the term for the oil that is derived from seeds and is mostly made up of fatty acids. The plant also has alkaloids, glycosides, saponins, and tannins in addition to oil. The leaves also contain carotene and ascorbic acid [15,16]. Figure 1 displays the specifics of the chemical components described in several publications.

Chemical constituents of Ocimum sanctum.

The neem tree (Azadirachta indica Juss), a member of the Meliaceae family that originated in India and is today regarded as a significant resource of phytochemicals which is effectively utilised not only in human health but also in pest management, is used to extract neem oil [17]. A small to medium evergreen tree with broad and spreading branches, Azadirachta grows quickly. Both high temperatures and weak or deteriorated soil are acceptable to it. The mature leaves, which have a brilliant green petiole, lamina, and the base that connects the leaf to the stem, are reddish to purple in colour in contrast to the young leaves’ reddish to purple hues [18].

A minimum of 100 physiologically active substances can be found in neem oil [19]. Triterpenes known as limonoids, the most significant of which is azadirachtin (Figure 1), are among their main ingredients and are thought to be responsible for 90% of the action on most pests [20]. The substance has a molecular weight of 720 g·mol−1 and a melting point of 160°C. Nimbidin, meliantriol, nimbin, nimbolides, fatty acids (oleic, stearic, and palmitic), and salannin are also included [21,22]. The oil obtained by various methods from the seeds is the primary neem product. Although the other neem tree sections are utilised to extract oil, they do not have as much azadirachtin [23]. It has been proposed that artificial inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhiza can enhance the amount of azadirachtin in seeds [24] (Figure 2).

Azadirachtin chemical structure.

Iron oxide has numerous advantages, including a narrow band gap energy of about 2.2 eV, low cost, non-toxicity, availability, and thermal stability. Magnetite contains both ferrous and ferric iron. As a result, it is commonly referred to as iron II and III oxide. There are three types of iron oxides found in nature: maghemite, magnetite, and hematite [25]. The hexagonal unit cell of hematite contains only octahedral coordinated Fe3+ atoms (corundum structure), whereas the cubic unit cell of magnetite contains both octahedral and tetrahedral coordinated Fe3+ atoms (the defect spinel structure) [26].

Due to its relatively low level poisonousness, new super-paramagnetic behaviour, good chemical constancy, and potent coat functionalisation with beneficial molecules to bind various biological ligands, magnetic iron oxide (Fe3O4) NPs have attracted amplified consideration in the biomedical commerce [25,26,27]. Fe3O4 nanoparticles (NPs), the most conventional magnetic nanoparticles because its exceptional magnetism, biocompatibility, reduced toxicity, biodegradability, and other qualities, have drawn a lot of interest in the biomedical area, particularly for targeted drug/gene delivery systems [28,29,30].

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) have generated interest during the past few years in a number of industries, including biosensors, electrical conductivity, biomedicine, catalysis, pharmaceuticals, as well as environmental uses [31]. AgNPs are the most exciting and promising material in nanotechnology due to their high specific surface energy, which encourages surface reactivity. However, AgNP agglomeration is inevitable. Therefore, a coating of magnetite onto AgNPs is required as an appropriate supplementary medium for the immobilisation of AgNPs in order to address the issues related to parting, retrieval, and constancy of AgNPs and to prevent its agglomeration throughout the creation process.

Consequently, the combining of Fe3O4 NPs and AgNPs to form a single hybrid functionalised nanostructure (Ag/Fe3O4 NPs) reveals a method to enable the improvement of every single component of a NP [32]. There are several physical and chemical approaches that may be used to create metal/Fe3O4 NPs, but they frequently call for pricey equipment, hazardous chemicals, and physical and chemical tactics that can actually affect the environment and human life [33]. Paul and co-workers synthesised Ag-Fe2O3 and applied them for the chemoselective reduction of nitroarenes [34], Ji and co-workers synthesised silver supported on cobalt oxide for photocatalytic oxidation of aromatic alcohols [35].

By entering bacterial biofilms, the Fe3O4/AgNP has previously demonstrated an improved potential bactericidal impact, acting as particularly acceptable antibacterial agents that reduce toxicity in healthy cells while also providing the ability to remove them from the media by means of a magnetic field [36,37,38,39,40]. Uncoated Fe3O4 NP oxidation and aggregation, which are accompanied by reduced magnetisation values, provide a considerable problem for several applications in the biomedical sector. A potentially useful multifunctional NP in this view is the augmentation of physical characteristics by magnetic behaviour with organic/inorganic NPs. While preventing the accumulation and oxidation of Fe3O4 NPs, this structure retains the qualities and advantages of each component [41]. TiO2 rutile, on the other hand, was selected as the host of the so-formed Ag/Fe2O3 NPs to acquire further properties for the intended nanocomposites owing to its known bioactivity. We are aware of no information about the biosynthesis of Ag/Fe2O3 nanocomposites utilising acacia in the presence of tulsi and neem oils. In green chemistry, we investigate the simple and sustainable synthesis of the Ag/Fe2O3 hybrid using acacia as the reducing agent in bioactive oils and in conjunction with TiO2 rutile to make the desired Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2.

2 Materials and methods

Analytical grade silver nitrate (AgNO3, >99.98%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. TiO2 rutile, sodium acetate (CH3COONa), ethanol (C2H5OH, >98%), and iron(iii) sulphate hydrate Fe2(SO4)3·6H2O was acquired from Sigma-Aldrich. Distilled deionised (DI) water was used to make all aqueous solutions.

2.1 Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 biosynthesis

For the synthesis of Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2, prepare 90 mL of a mixture solution (1% acacia, 0.1 g Fe(SO4)3·6H2O, and 0.1 g AgNO3, and 0.2 g TiO2), which is blended together. Following complete homogenisation of the solution, 10 mL of tulsi or neem oil is added dropwise to the solution using a magnetic stirrer at 300 rpm and 70°C for 3 h (Scheme 1). The colour shift of the reaction system was observed and recorded visually. After the precipitate has completely formed, the solution is allowed to stand for 3 h before being centrifuged for 10 min at 4,000 rpm. To remove ionic contaminants, the precipitate is thoroughly rinsed with DI water, followed by acetone to remove any organic impurities. Before being burned at 350°C for 12–15 h, the precipitate is oven dried.

2.2 Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 characterisation

The measurements of the powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the materials were made on a Holland Philips X-ray powder diffractometer using Cu K radiation (=0.1542 nm) with smattering angles (2) of 5–80. Additionally, a few samples of synthetic Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 NPs were generated for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) experiments by ultrasonically dispersing the NPs in ethanol, and the suspensions were then placed onto a copper grid covered in carbon. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) spectra were obtained on a Bruker VERTEX 80 v model to investigate the functional group of materials that were analyzed using KBr disc technique on a Bruker VERTEX 80 v model while SEM was performed using a (CM30 3000Kv). The functional group of materials was investigated utilising The dynamic light scattering (DLS) method was used to characterise the size distribution of Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 NPs, and a computerised inspection system (MALVERN Zen3600) with DTS® (nano) software was used. Using a Varian Cary 50 UV-vis spectrophotometer, UV-Vis studies were performed. Spectra between 350 and 800 nm were captured.

3 Results and discussion

In this investigation on the production of Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2, the oils of neem and tulsi were selected and used. Neem and tulsi oils, which can act as a dropping and stabilising mediator in the synthesis of Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite, are the main ingredients in this process, which aim to offer a clean, ecologically friendly approach of producing nanomaterials.

Fe (SO4)3·6H2O and AgNO3 were used as precursors in the synthesis of Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 by adding them to neem and tulsi until a gradual change in reaction colour was seen. The reaction mixture’s colour changed from white to brown after 3 h of incubation at 70°C (Figure 3). Figure 3 shows the Ag/Fe2O3 nanocomposite’s UV-Vis spectra after 3 h, which were measured in the 300–800 nm region. The large peak created at 320 nm, as shown in the UV-Vis spectra, served as a signal to recognise the development of Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite. Similar to this, Berastegui et al.’s UV-Vis investigations of AgFeO2 NPs exhibited strong absorptions between 300 and 650 nm [42]. The increase in absorbance at 320 nm was brought on by the addition of Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite (Figure 3).

Colour change and UV-Vis absorption spectra of Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nano-composite synthesis by tulsi and neem oils.

The physical characteristics of the bioactive components in tulsi and neem oils, as well as potential biochemical changes brought on by the production of Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2, were examined using FT-IR spectroscopic examination with a spectrum range of 400–4,000 cm−1, as shown in Figure 4. The hydroxyl and phenolic groups in tulsi and neem oils were found to vibrate in a wide range between 3,367.9 and 3,216.9 cm−1 [43]. The bands located at 2,918.5 cm−1 and 2,850.6 cm−1 belong to the –CH group. The sharp peaks on 1,728.7 cm−1 point to the presence of C–O in the ester group. The peak on 1,603.8 cm−1 signifies the existence of NH amine. The peak value of 1,008 cm−1 provided by FT-IR analysis, which further supports the presence of practical groups like carboxylic acid and ether, is used in this context. The bioactive substances in tulsi and neem oils are used to change ions into the proper metal forms. Additionally, these phytochemicals have highly sensitive hydroxyl groups that produce hydrogen and reduce free radicals by doing so. The results provide credence to the hypothesis that these phytochemicals are involved in the bio-reduction process that generates nanomaterials [44]. According to the IR spectra of Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 (Figure 4), changes during Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 formation, including redox of phytochemicals, can be blamed for the suppression of aliphatic molecules. Additionally, IR measurements showed that chemical groups from the extract were attached to the Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 layer, proving that the use of tulsi and neem oils as stabilisers aided in the production of nanocomposite materials. The presence of peaks at 611.4 and 561.4 cm−1, respectively, in (Figure 4) may be explained by the bending vibration of AgO and FeO interactions in Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2.

FTIR spectral analysis of neem and tulsi oils, and Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite.

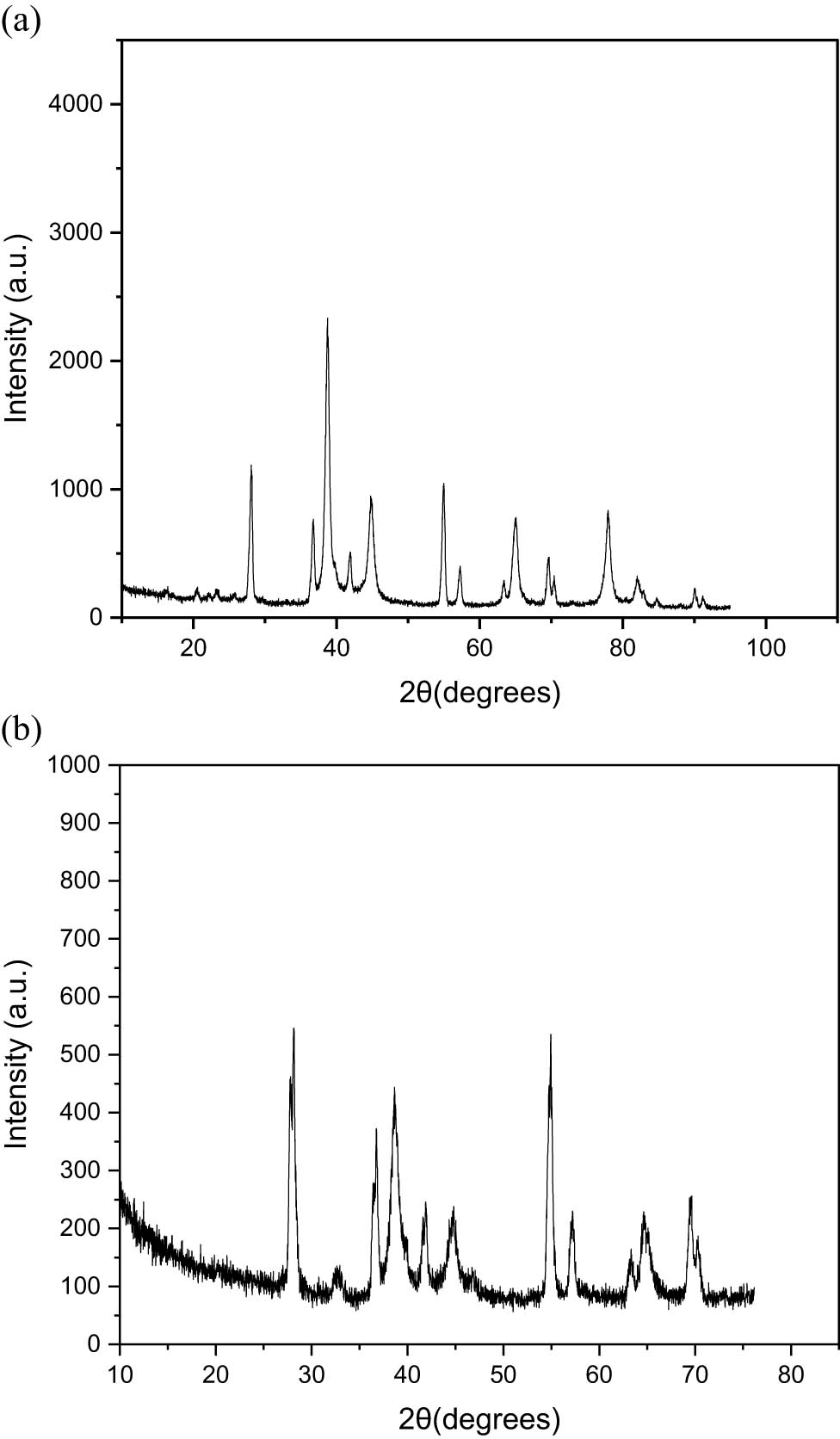

XRD analysis was used to verify the Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 NPs’ crystalline structure, as shown in Figure 5. The diffraction peaks of TiO2 rutile at 2θ = 27.3°, 36.0°, 41.1°, 54.2°, 62.7°, and 69.0° are related to the (110), (101), (111), (211), (002), and (112) reticular planes of rutile [45]. Characteristic diffraction peaks due to AgNPs at 2θ values of 38.32, 44.54, 64.61, 77.54, and 81.68 corresponding to (111), (200), (220), (311), and (222) planes of silver is observed (JCPDS, silver file No. 04–0783). On the other hand, Fe2O3 diffraction peaks appear partially overlapped with those of AgNPs and TiO2 and can be observed at 35.7, 53.1, 57.1, and 62.7 and attributed to the planes of (311), (422), (511), and (440) from the cubic structure of γ-Fe2O3 NPs (JCPDS, No. 04-0755).

XRD of the synthesised Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 by (a) tulsi oil and (b) neem oil.

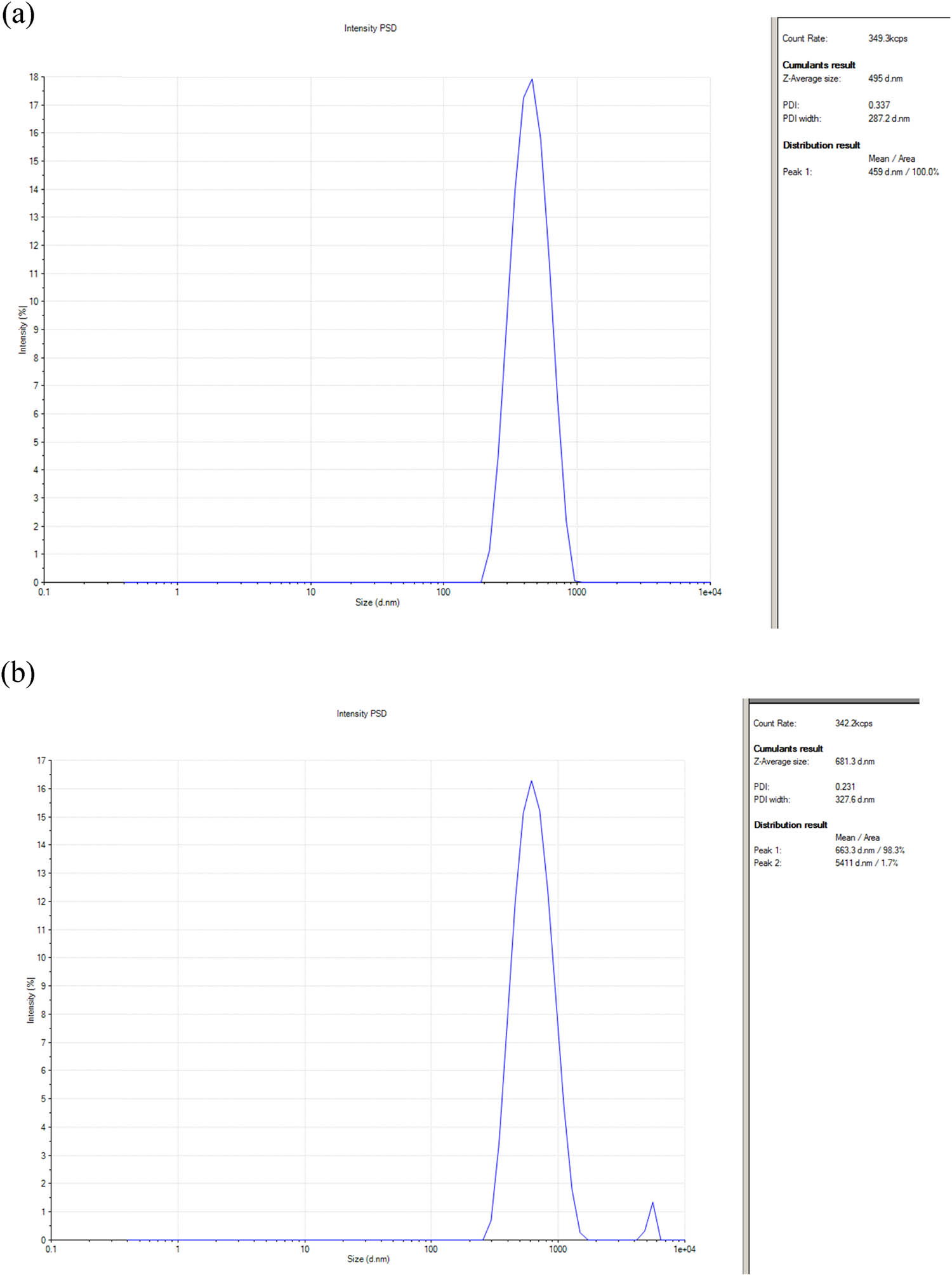

The SEM is the method that is most frequently used to determine the morphological characteristics and sizes of manufactured nanostructures. As observed in the SEM images (Figures 6 and 7), the Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposites are produced in a spherical shape, with an average size range of 25–174 nm. The bright circular spots revealed the nanocomposite planes and the degree of crystallinity of the Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 particles made up of neem and tulsi oils (Figures 6 and 7). DLS analysis was used to measure the average diameter of the Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite. The bulk diameter of the Ag/Fe2O3 nanocomposite is 270.9 nm. However, the metal core (Ag and Fe) of the Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite as well as the biomaterials (organic chemicals related as stabilisers) deposited by neem and tulsi oils on the Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 surface change the size estimated by DLS [46] (Figure 8 and Table 1).

SEM of the synthesised Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 by tulsi oil.

SEM of the synthesised Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 by neem oil.

DLS of the synthesised Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 by (a) tulsi oil and (b) neem oil.

DLS of the synthesised Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 by tulsi and neem oils

| Sample reference | Z-Average (d·nm) | PDI | PDI width (d·nm) | Mean value/area (d·nm) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tulsi oil | 495.0 | 0.337 | 287.2 | 459/100 |

| Neem oil | 681.3 | 0.231 | 327.6 | Peak 1/98.3 |

| 663.3 | ||||

| Peak 2/1.7 | ||||

| 5,411 |

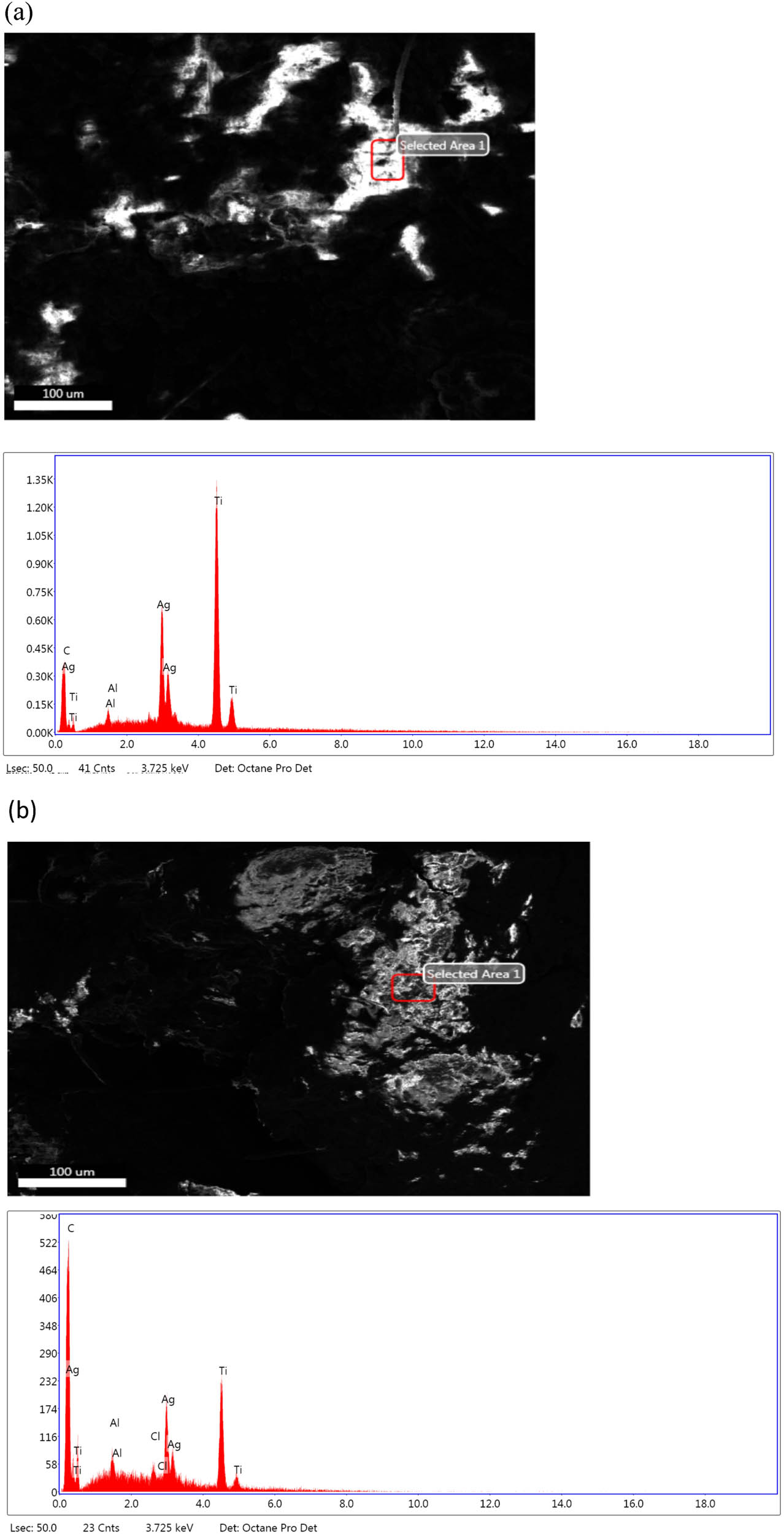

The Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite surface had components efficiently deposited on it, according to an energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis (Figure 9). The Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite was found to include multiple distinct peaks in the EDX spectra which were linked to the oxygen, silver, iron, and carbon constituents (Figure 9). The development of an extremely pure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite with no extra impurity-related peaks was further demonstrated by EDX spectra. The SEM image and EDX spectra of the nanocomposite showed that the Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanostructures were evenly distributed throughout the neem and tulsi. In addition, the composition of Ag and Fe in Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 was determined by elemental EDX mapping. Figure 9 shows the charting of Fe, Ag, O, and C. As stated by the EDX fundamental analysis in the Fe, Ag, O, and C component charting imageries of Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 (Figure 9), both Ag and Fe were uniformly distributed throughout the sample [47].

EDX analysis (a) Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 tulsi oil and (b) Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 neem oil.

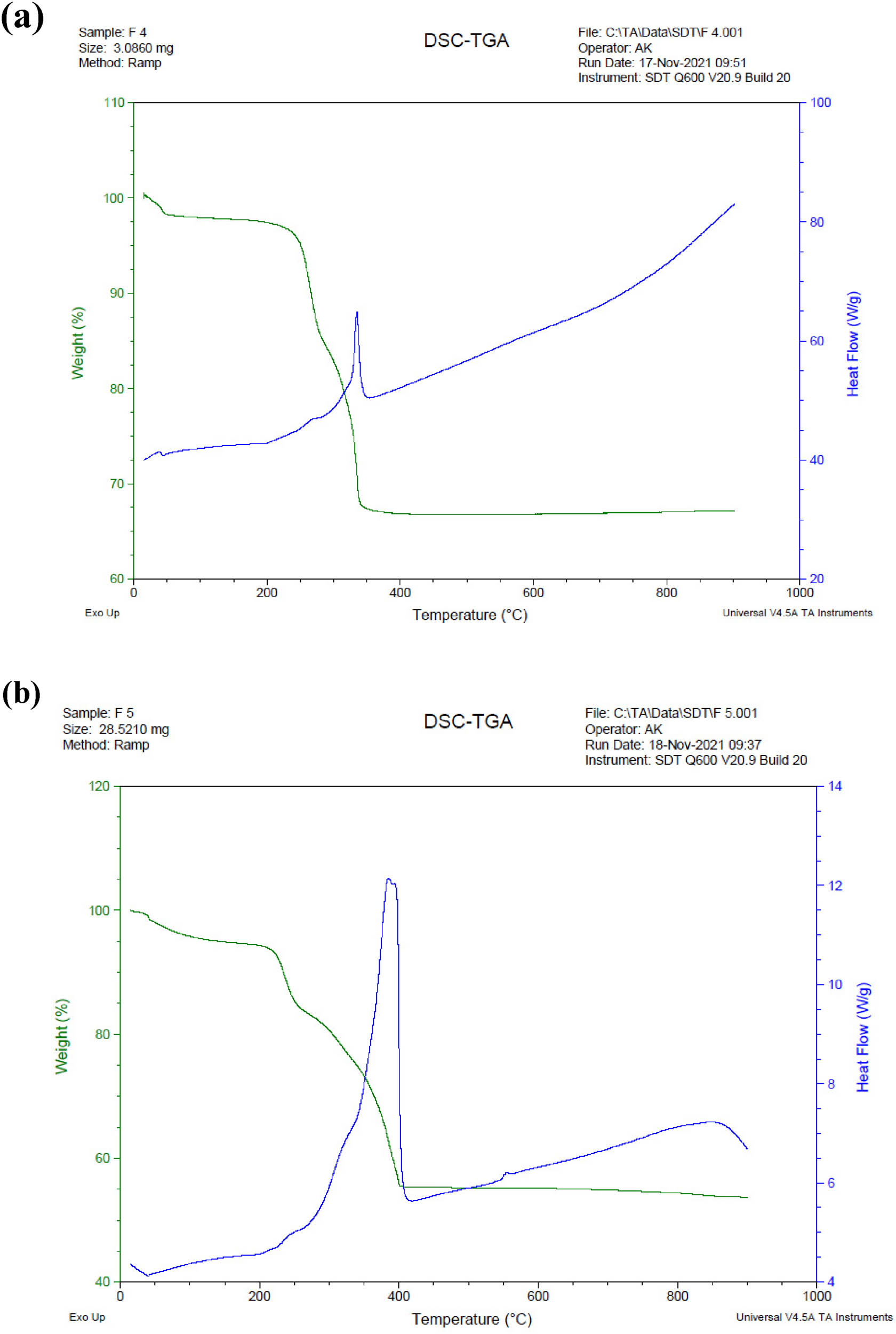

TGA studies are performed by heating the materials in air to 600°C (Figure 10) in order to determine the thermal stability.

TGA of (a) Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 tulsi oil and (b) Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 neem oil.

Figure 10(a and b) depicts the Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite TGA curves produced by tulsi and neem oils. The greatest loss of weight (65%) at the range of temperature between 170°C and 525°C may be attributed to the pyrolysis of the labile oxygen-comprising clusters in the forms of CO2, CO, and vapour. The loss of weight of approximately 5% at the temperatures between 100°C and 170°C may be because of the water molecules elimination and it was confined inside the GO. When the Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nano-composite sample was heated to 800°C at an incremental rate of 10°C·min−1, there was only a 17% total weight loss. This weight loss is due to the removal of remaining Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite oxygen-containing groups from tulsi and neem oils.

Although the quantitative findings from this approach are not as precise as those from atomic absorption analysis, they are nevertheless reliable when comparing the amounts of silver in the samples.

4 Conclusion

One of the most fascinating subjects in the realm of nanotechnology is the green production of nanomaterials. In this sense, recent years have seen advancements in biosynthesis utilising medicinal plant oils. Tulsi and neem oils were used in this study as reducing agents to change the Ag0 cation in AgNO3 solution to Ag0. Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 NPs were created as a result of the interaction between AgNO3 solution and acacia in the presence of tulsi and neem oils. The effective synthesis of Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 NPs was validated by a variety of characterisation techniques, including XRD, SEM, FT-IR, DLS, and UV-vis spectroscopy. The outcome of the DLS study and the SEM picture indicated that the average particle size was 28 nm. Similarly, SEM scans showed that Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 NPs had spherical shapes. The FT-IR data also showed that tulsi and neem oils were used as surfactants and capping agents to regulate the form and size of these NPs. Last but not least, this technique may be used to produce various kinds of metal NPs on a big scale and remove a lot of harmful chemical reagents used in manufacturing nanomaterials. Future work would be the potential application of the new materials made, and the outcome of this work will be published elsewhere.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the King Deanship of Scientific Research at Khalid University for funding this work through a large group Research Project under grant number RGP2/143/44.

-

Funding information: Khalid University for funding this work through a large group Research Project under grant number RGP2/143/44.

-

Author contributions: Fatimah Ali M. Al-Zahrani: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, methodology, and formal analysis; project administration; Reda M. El-Shishtawy: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, methodology, and formal analysis

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Al-Zahrani FAM, AL-Zahrani NA, Al-Ghamdi SN, Lin L, Salem SS, El-Shishtawy RM, et al. Synthesis of Ag/Fe2O3 nanocomposite from essential oil of ginger via green method and its bactericidal activity. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2022;12(10):1–9.10.1007/s13399-022-03248-9Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Al-Zahrani F, Salem SS, Al-Ghamdi HA, Nhari LM, Lin L, El-Shishtawy RM. Green synthesis and antibacterial activity of Ag/Fe2O3 nanocomposite using Buddleja lindleyana extract. Bioengineering. 2022;9(9):452.10.3390/bioengineering9090452Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Paul B, Bhuyan B, Dhar Purkayastha D, Dey M, Dhar SS. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Pogestemon benghalensis (B) O. Ktz. leaf extract and studies of their photocatalytic activity in degradation of methylene blue. Mater Lett. 2015;148:37–40.10.1016/j.matlet.2015.02.054Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Koech RK, Olanrewaju YA, Ichwani R, Kigozi M, Oyewole DO, Oyelade OV, et al. Effects of polyethylene oxide particles on the photo-physical properties and stability of FA-rich perovskite solar cells. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):12860.10.1038/s41598-022-15923-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Anderson SD, Gwenin VV, Gwenin CD. Magnetic functionalized nanoparticles for biomedical, drug delivery and imaging applications. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2019;14:1–16.10.1186/s11671-019-3019-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Comanescu C. Magnetic nanoparticles: Current advances in nanomedicine, drug delivery and MRI. Chemistry. 2022;4(3):872–930.10.3390/chemistry4030063Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Varadavenkatesan T, Pai S, Vinayagam R, Selvaraj R. Characterization of silver nano-spheres synthesized using the extract of Arachis hypogaea nuts and their catalytic potential to degrade dyes. Mater Chem Phys. 2021;272:125017.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2021.125017Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Bhole R, Gonsalves D, Murugesan G, Narasimhan MK, Srinivasan NR, Dave N, et al. Superparamagnetic spherical magnetite nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization and catalytic potential. Appl Nanosci. 2023;13(9):6003–14.10.1007/s13204-022-02532-4Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Shet VB, Kumar PS, Vinayagam R, Selvaraj R, Vibha C, Rao S, et al. Cocoa pod shell mediated silver nanoparticles synthesis, characterization, and their application as nanocatalyst and antifungal agent. Appl Nanosci. 2023;13(6):4235–45.10.1007/s13204-023-02873-8Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Agarwal P, Nagesh L. Evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of various concentrations of Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum) extract against Streptococcus mutans: An in vitro study. Indian J Dental Res. 2010;21(3):357–9.10.4103/0970-9290.70800Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Pandey G, Madhuri S. Pharmacological activities of Ocimum sanctum (tulsi): a review. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2010;5(1):61–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Baliga MS, Jimmy R, Thilakchand KR, Sunitha V, Bhat NR, Saldanha E, et al. Ocimum sanctum L (Holy Basil or Tulsi) and its phytochemicals in the prevention and treatment of cancer. Nutr cancer. 2013;65(sup1):26–35.10.1080/01635581.2013.785010Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Borah R, Biswas S. Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum), excellent source of phytochemicals. Int J Environ Agric Biotechnol. 2018;3(5):265258.10.22161/ijeab/3.5.21Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Verma S. Chemical constituents and pharmacological action of Ocimum sanctum (Indian holy basil-Tulsi). J Phytopharmacol. 2016;5(5):205–7.10.31254/phyto.2016.5507Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Yamani HA, Pang EC, Mantri N, Deighton MA. Antimicrobial activity of Tulsi (Ocimum tenuiflorum) essential oil and their major constituents against three species of bacteria. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:681.10.3389/fmicb.2016.00681Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Mohan L, Amberkar M, Kumari M. Ocimum sanctum linn (TULSI) - an overview. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2011;7(1):51–3.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Rahmani A, Almatroudi A, Alrumaihi F, Khan A. Pharmacological and therapeutic potential of neem (Azadirachta indica). Pharmacogn Rev. 2018;12(24):250–5.10.4103/phrev.phrev_8_18Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Saha S, Singh D, Rangari S, Negi L, Banerjee T, Dash S, et al. Extraction optimization of neem bioactives from neem seed kernel by ultrasonic assisted extraction and profiling by UPLC-QTOF-ESI-MS. Sustain Chem Pharm. 2022;29:100747.10.1016/j.scp.2022.100747Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Campos EV, de Oliveira JL, Pascoli M, de Lima R, Fraceto LF. Neem oil and crop protection: from now to the future. Front plant Sci. 2016;7:1494.10.3389/fpls.2016.01494Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Roy A, Saraf S. Limonoids: overview of significant bioactive triterpenes distributed in plants kingdom. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29(2):191–201.10.1248/bpb.29.191Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Igbo UE, Ishola RO, Siedoks AO, Akubueze EU, Isiba VI, Igwe CC. Comparative study of physicochemical and fatty acid profiles of oils from under utilised nigerian oil seeds. The Pharmaceutical and Chemical Journal. 2019;6(5):103–9Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Kumari P, Geat N, Maurya S, Meena S. Neem: Role in leaf spot disease management: A review. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2020;9(1):1995–2000.10.22271/phyto.2020.v9.i2ab.11094Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Khanam Z, Al-Yousef HM, Singh O, Bhat IU. Neem oil. Green pesticides handbook: Essential oils for pest control. New York, NY, USA: CRC Press; 2017. p. 377.10.1201/9781315153131-20Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Islas JF, Acosta E, G-Buentello Z, Delgado-Gallegos JL, Moreno-Treviño MG, Escalante B, et al. An overview of Neem (Azadirachta indica) and its potential impact on health. J Funct Foods. 2020;74:104171.10.1016/j.jff.2020.104171Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Pourbahar N, Alamdar SS. Phytofabrication, and characterization of Ag/Fe3O4 nanocomposite from rosa canina plant extracts using a green method. Asian J Green Chem. 2023;7:9–16.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Taha AB, Essa MS, Chiad BT. Spectroscopic study of iron oxide nanoparticles synthesized via hydrothermal method. Chem Methodol. 2022;6(12):977–84.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Fadli A, Amri A, Sari EO, Sukoco S, Saprudin D. Superparamagnetic nanoparticles with mesoporous structure prepared through hydrothermal technique. In Materials science forum. 2020;1000(1):203–9.10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.1000.203Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Liu M, Ye Y, Ye J, Gao T, Wang D, Chen G, et al. Recent advances of magnetite (Fe3O4)-based magnetic materials in catalytic applications. Magnetochemistry. 2023;9(4):110.10.3390/magnetochemistry9040110Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Noh J, Osman OI, Aziz SG, Winget P, Brédas JL. Magnetite Fe3O4 (111) surfaces: impact of defects on structure, stability, and electronic properties. Chem Mater. 2015;27(17):5856–67.10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b02885Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Jain S, Shah J, Dhakate SR, Gupta G, Sharma C, Kotnala RK. Environment-friendly mesoporous magnetite nanoparticles-based hydroelectric cell. J Phys Chem C. 2018;122(11):5908–16.10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b12561Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Ravichandran R, Annamalai K, Annamalai A, Elumalai S. Solid state–Green construction of starch-beaded Fe3O4@ Ag nanocomposite as superior redox catalyst. Colloids Surf A: Physicochem Eng Asp. 2023;664:131117.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2023.131117Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Elhouderi ZA, Beesley DP, Nguyen TT, Lai P, Sheehan K, Trudel S, et al. Synthesis, characterization, and application of Fe3O4/Ag magnetic composites for mercury removal from water. Mater Res Express. 2016;3(4):045013.10.1088/2053-1591/3/4/045013Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Qi C-C, Zheng J-B. Synthesis of Fe3O4–Ag nanocomposites and their application to enzymeless hydrogen peroxide detection. Chem Pap. 2016;70(4):404–11.10.1515/chempap-2015-0224Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Paul B, Purkayastha DD, Dhar SS, Das S, Haldar S. Facile one-pot strategy to prepare Ag/Fe2O3 decorated reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite and its catalytic application in chemoselective reduction of nitroarenes. J Alloy Compd. 2016;681:316–23.10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.04.229Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Ji X, Chen Y, Paul B, Vadivel S. Photocatalytic oxidation of aromatic alcohols over silver supported on cobalt oxide nanostructured catalyst. J Alloy Compd. 2019;783:583–92.10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.12.307Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Katz E. Synthesis, properties and applications of magnetic nanoparticles and nanowires – A brief introduction. Magnetochemistry. 2019;5(4):61.10.3390/magnetochemistry5040061Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Pang Y, Wang C, Wang J, Sun Z, Xiao R, Wang S. Fe3O4@Ag magnetic nanoparticles for microRNA capture and duplex-specific nuclease signal amplification based SERS detection in cancer cells. Biosens Bioelectron. 2016;79:574–80.10.1016/j.bios.2015.12.052Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Chen T, Geng Y, Wan H, Xu Y, Zhou Y, Kong X, et al. Facile preparation of Fe3O4/Ag/RGO reusable ternary nanocomposite and its versatile application as catalyst and antibacterial agent. J Alloy Compd. 2021;876:160153.10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.160153Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Nguyen-Tri P, Nguyen VT, Nguyen TA. Biological activity and nanostructuration of Fe3O4-Ag/high density polyethylene nanocomposites. J Compos Sci. 2019;3(2):34.10.3390/jcs3020034Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Venkateswarlu S, Natesh Kumar B, Prathima B, Anitha K, Jyothi NVV. A novel green synthesis of Fe3O4-Ag core shell recyclable nanoparticles using Vitis vinifera stem extract and its enhanced antibacterial performance. Phys B: Condens Matter. 2015;457:30–5.10.1016/j.physb.2014.09.007Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Thu TV, Ko PJ, Nguyen TV, Vinh NT, Khai DM, Lu LT. Green synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/Fe3O4/Ag ternary nanohybrid and its application as magnetically recoverable catalyst in the reduction of 4‐nitrophenol. Appl Organomet Chem. 2017;31(11):e3781.10.1002/aoc.3781Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Berastegui P, Tai C-W, Valvo M. Electrochemical reactions of AgFeO2 as negative electrode in Li-and Na-ion batteries. J Power Sources. 2018;401:386–96.10.1016/j.jpowsour.2018.09.002Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Kaloti M, Kumar A. Synthesis of chitosan-mediated silver coated γ-Fe2O3 (Ag− γ-Fe2O3@Cs) superparamagnetic binary nanohybrids for multifunctional applications. J Phys Chem C. 2016;120(31):17627–44.10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b05851Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Kulkarni S, Jadhav M, Raikar P, Barretto DA, Vootla SK, Raikar US. Green synthesized multifunctional Ag@Fe2O3 nanocomposites for effective antibacterial, antifungal and anticancer properties. N J Chem. 2017;41(17):9513–20.10.1039/C7NJ01849ESuche in Google Scholar

[45] Du J, Sun H. Polymer/TiO2 hybrid vesicles for excellent UV screening and effective encapsulation of antioxidant agents. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6:13535–41.10.1021/am502663jSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Mirzaei A, Janghorban K, Hashemi B, Bonavita A, Bonyani M, Leonardi SG, et al. Synthesis, characterization and gas sensing properties of Ag@ α-Fe2O3 core–shell nanocomposites. Nanomaterials. 2015;5(2):737–49.10.3390/nano5020737Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Liu J, Wu W, Tian Q, Dai Z, Wu Z, Xiao X, et al. Anchoring of Ag6Si2O7 nanoparticles on α-Fe2O3 short nanotubes as a Z-scheme photocatalyst for improving their photocatalytic performances. Dalton Trans. 2016;45(32):12745–55.10.1039/C6DT02499HSuche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”