Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

Abstract

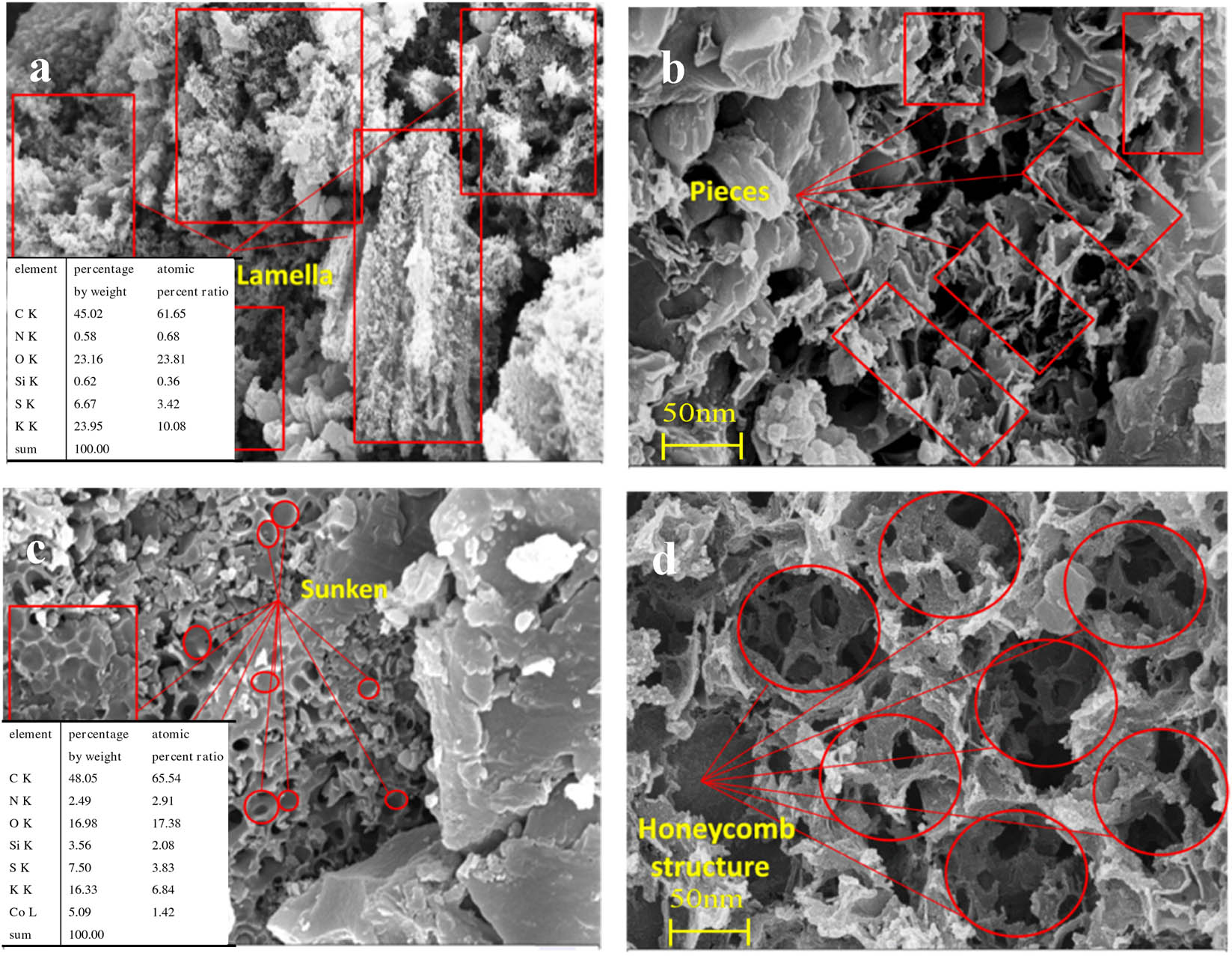

The coal base electrodes and efficient coal base loaded cobalt electrodes (Co-CE) were prepared by pyrolysis method of low rank coal united activation method of KOH in order to develop more pores structures. The morphology of electrodes were characterized by Scanning electron microscopy, meanwhile, the type of elements were detected by energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). The electrochemical performance of electrodes were tested by cyclic voltammetry and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. The lamella structures and pores were observed in microtopography of electrodes and the cobalt were successfully loaded in Co-CE from the EDS analysis. The operating conditions of processing time, current density, electrolyte concentration, pH and initial phenol concentration on this electrochemical system in single factor experiment were separately explored, correspondingly, the value was 180 min, 40 mA·cm−2, 0.01 mol·L−1, 2, 100 mg·L−1, and the phenol removal rate (R) were at the range of 47.64–67.84%. In the optimization experiment of JMP design, the removal rate could reach at 83.47%. The response surface methodology was employed for optimizing operation conditions to improve R. And the prediction model obtained for the response can be represented as: R = 66.5275 + 6.7311X 1 – 5.4197X 4 – 5.2303X 5 + 4.9555X 1 2 – 12.5219X 2 2 – 6.2912X 4 2 + 16.0937X 5 2 + 2.4109X 2 X 4 – 7.910X 3 X 4 – 3.0123X 3 X 5 – 2.183X 4 X 5. The optimized conditions were pH 3, 100 mg·L−1 of phenol concentration, 0.1 mol/L of electrolyte concentration, 35 mA/cm2 of current density, and 180 min of processing time. Meanwhile, the predicted R was 90.86%, the actual R of three parallel experiments were 91.2%, 89.3%, 91.05%, which were well consistent with the predicted value. Additionally, the degradation mechanism was proposed as that the adsorption in pore structures synergy electrocatalytic effect of Co-CE. Micro-electric fields formed in pores and the transition metal catalysis accelerated the transformation of cathode hydrogen peroxide to generate hydroxyl radical (·OH). Furthermore, the ·OH were produced both by cathode and anode which promoted the degradation of phenol. This high catalytic activity and low cost Co-CE is a kind of prospective electrode for electrochemical degradation of phenolic wastewater.

Abbreviations

- ACGIH

-

American government conference of industrial hygienists

- ANOVA

-

Analysis of Variance

- AOPs

-

Advanced oxidation processes

- AR

-

Analytical reagent

- CCD

-

Central composite design

- CE

-

Coal based electrode

- CEM

-

Coal based electrode materials

- Co-CE

-

Coal base loaded cobalt electrode

- Co-CE-Hy

-

Co-coal based electrode loaded with Co by hydrothermal method

- Co-CE2

-

Co-coal based electrode added with 2% cobalt nitrate powder tablet

- Co-CE5

-

Co-coal based electrode added with 5% cobalt nitrate powder tablet

- CV

-

Cyclic voltammetry

- DCLR

-

Direct coal liquefaction residue

- Df

-

Degrees of freedom

- DSA

-

Dimension stable anode

- EDS

-

Energy dispersive spectroscopy

- EIS

-

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy

- EPA

-

Environmental protection agency

- Gr

-

Graphite electrode

- OCP

-

Open circuit potential

- OEP

-

Oxygen evolution potential

- OH

-

Hydroxyl radical

- R

-

Removal rate

- R 2

-

Correlation coefficient

- RSM

-

Response Surface Methodology

- R ct

-

charge transfer resistance

- SCE

-

Saturated calomel electrode

- SEM

-

Scanning electron microscopy

- SJC

-

Sunjiacha coal mine

1 Introduction

As the simplest phenolic compound, phenol was first recovered from coal tar, and most of it was prepared by sulfonation, cumene and other synthetic methods [1]. Phenol is not only an important chemical raw material, also has been widely used in industries such as petroleum industries, oil refining, pharmaceutical industry [2]. According to classification of Environmental protection agency, phenolic compounds were classified as the primary pollutants [3]. The American government conference of industrial hygienists set the standard of phenol exposure limit as 100 ppm. Due to its high toxicity, a small amount of phenol does great harm to people and animals, phenol removal is of great significance for environmental protection treatment and wastewater utilization [4]. The widespread demand for phenol in industry and the increasingly stringent national discharge standards for phenol-contain wastewater, determines phenolic wastewater treatment technology is facing great challenges [5].

Electrochemical method has great significance for industrial wastewater treatment and has been successfully applied for many kind of refractory wastewater [6]. Phenolic wastewater was treated using manifold process like adsorption, chemical method, biological degradation, photocatalysis and Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) [7,8]. The adsorption has been identified as a promising method due to its simplicity and high efficiency, but the adsorbent reuse is relatively difficult to regeneration [9,10,11,12]. Although biological treatment is simple in operation and low in energy consumption, it has limited effect on the removal of toxic refractory substances and cannot completely remove phenolic compounds [13,14]. The chemical oxidation method is easy to operate, but the operation cost is high, and it also easy to cause secondary pollution [15]. The photocatalytic oxidation method has strong oxidation ability and good performance, whereas, the catalyst requirements are high and the recovery is difficult [16,17]. AOPs uses ozone, hydrogen peroxide, UV radiation produce free radical, a strong oxidizer that promote the degradation of refractory organic molecules [18]. Due to the high oxidation potential and non-selective to contaminant, AOPs have high efficiency [19], however, It is also easy to cause energy consumption [20,21], the cost of chemicals and energy is an important issue. Electrochemical oxidation as one of the AOPs, owing the features of low capital cost, simplicity of operation and no secondary pollution, attracted a wide spread attention [7,22]. Electrochemical methods comparative have better environmental compatibility, higher energy efficiency and easier automation [23]. hydroxyl radical (·OH) with strong oxidizing property was produced by electrochemical method. It can efficiently decompose organic pollutants through oxidation reactions, and even completely convert them into harmless inorganic substances [24]. Oxide species play a great role in the oxidative decomposition of pollutants. The formation of ·OH mainly depends on the electrode materials [22]. Because of its green and efficient characteristics, electrochemical method is considered to be a method with great development potential, and has been deeply explored and studied [25].

The catalytic efficiency of the electrode is improved by doping modification of the electrode [26], Coal based electrode materials (CEM) is a kind of electrode material with great development potential because of its porous, environmental protection and high efficiency. In recent years, although scholars have made great efforts to develop modified electrodes, carbon, metal oxides and other electrocatalysts still limited by the shortcoming of poor stability and high cost [27]. Many scientists are committed to developing cathodes with high catalytic activity and stability for electrochemical advanced oxidation to remove organic pollutants. With the advantages of low cost, rich porosity, high specific surface area and many active sites on the molecular structure of coal, it has been widely used in the fields of catalysis and adsorption [28]. The advantages of corrosion resistance make it stable under acidic conditions through adsorption synergistic electrochemical degradation of benzene.

Transition metals have become a research hotspot in the field of electrochemistry because of their variable valence state and strong redox ability [29]. The coal base electrodes (CE) can refine the particle size of the electrode by doping metal ions, the compactness and stability were improved, and the transition metal Co ions were doped to promote the production of ·OH, thereby improving the catalytic activity [30,31]. Li doped an appropriate amount of polyethylene glycol and bismuth into the active layer of lead dioxide, which significantly improved the catalytic oxidation performance. The degradation rate of phenol by the prepared electrode was 1.57 times than that of the pure lead dioxide electrode [32]. Yu Zhiyong [33] found that the introduction of Co ions into the Li2MoO3 lattice can reduce the particle size of the cathode material, so the doping operation of Co improved the structural stability of the material and reduces the impedance, thereby improving the electrochemical stability of the material is very important. Wang Ying [31] also insisted that the doping of Co can reduce the particle size of PbO2 and increase the lifetime of PbO2, which is beneficial to improve the electrocatalytic activity. After the addition of cobalt hydroxide to nickel hydroxide, the mechanical properties have been greatly improved. Even after the charge-discharge cycle, the particle size of the active material in the cobalt-containing electrode is still smaller than that in the cobalt-free electrode. Thereby it is necessary to improve the surface utilization of the active material. When the cobalt content in the active material is not less than 5%, the brittleness is small and the sensitivity to the generated stress is low, which can prolong the cycle life of material [34]. Chang [35] found that direct incorporation of cobalt into the prepared electrode will greatly increase the utilization rate of the active material and increase the average discharge voltage of the battery. And the effect increases with the increase of cobalt content. Among them, the 5 wt% cobalt electrode exhibits the highest average discharge voltage, and further increase of cobalt content has limited performance improvement.

Response surface methodology (RSM) is a statistical technique based on polynomial equation to fit experimental data. It is one of the effective methods to design experimental conditions [36]. To design and optimized the experiment, RSM were used to design and optimize appropriate statistics for the study process. When a set of responses of interest is affected by multiple variables, compared with the traditional single-factor statistical method, the RSM method not only the influence of a single variable can be predicted, but also can optimize and model the linear and complex relationship between variables and system response under limited number of experiments [21]. Dargahi used Central composite design (CCD-RSM) modeling to explore the removal of phenolic compounds by the adsorption process of modified adsorbents [9]. The electrochemical experiments were designed by RSM. The Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) results obtained from RSM showed that the removal of tetracycline by electrochemical process could be predicted logically and accurately [20].

Coking wastewater contains a large number of phenolic pollutants, the electrochemical degradation of simulated phenol wastewater was carried out by using coal base loaded cobalt electrodes (Co-CE) as cathode, meanwhile the removal effect of phenol was evaluated. The objectives of this work are: (i) select the potential effect electrode by compare experiments of CE, graphite and Co-CE electrodes. (ii) investigate the effect of pH, processing time, current density, electrolyte concentration and phenol concentration, and optimize the system process by CCD-RSM. (iii) the possible degradation pathway of phenol was proposed based on the behavior of this electrochemical system.

2 Experiment

2.1 Materials and reagents

The raw materials are low rank coal from Sunjiacha coal mine (SJC) and Direct coal liquefaction residue (DCLR) from a coal chemical plant, which were both originated from Yulin, Shaanxi Province. The industrial analysis and elemental analysis of them were shown in the Table 1.

Industrial analysis and elemental analysis of raw materials

| Sample | Industrial analysis (%) | Elemental analysis (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mt | Aad | Vad | FCad | Cad | Oad | Had | Nad | St,ad | |

| SJC | 2.94 | 4.21 | 30.51 | 56.16 | 76.40 | 17.60 | 4.70 | 1.00 | 0.30 |

| DCLR | 0.14 | 17.64 | 33.75 | 48.37 | 75.00 | 17.33 | 4.72 | 0.77 | 2.13 |

ad: air dry basis; Mt: total moisture; St,ad: total sulfur.

All the chemical drug were commercially available and directly used without further purification. Phenol (AR Grade) was provided by Tianjin Zhiyuan Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd, China. Nitric acid (HNO3, 65–68%) was supplied by Chengdu Kelong Chemical Reagent Factory, China. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, ≥96%) was provided by Tianjin Hedong Hongyan Reagent Factory, China. Sodium sulfate anhydrous (Na2SO4, ≥99.0%)) was purchased from Tianjin Damao Chemical Reagent Factory. 4-Aminoantipyrine (≥98.5%) was provided by Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd, China. Ammonium chloride (NH4Cl, ≥99.5%)) was provided by Tianjin Sheng’ao Chemical Reagents Co., Ltd, China. Potassium hexacyanoferrate (K3(Fe(CN)6), ≥99.5%) was provided by Tianjin Tianli Chemical Reagents Co., Ltd, China. Cobalt(ii) nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO3)2·6H2O, AR Grade) was obtained from Guangdong Guanghua Sci-Tech Co., Ltd, China. Ethanol (C2H5OH, ≥99.7%) was purchased from Tianjin Fuyu Fine Chemical Co., Ltd, China. Ammonia solution (NH3, AR Grade), Sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 95–98%) was purchased from Tianjin Kermel Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd, China.

2.2 Preparation of Co-CE materials

The specific diagram of the Preparation flow of Co-CE is illustrated in Figure 1. For a typical run, the SJC and DCLR first ground separately in a planet-wheel ball mill at a rotation, then was sieved to a powder in a diameter of fewer than 120 μm and mixed in a weight ratio of 4:1. Thereafter, the 10% KOH were added into coal dry material as an activator solution and dried under vacuum at 120°C for overnight [37]. The CoNO3 were mixed with fine pretreated coal powers in a wight ratio of 5 wt%, Under a pressure of 5 MPa to form a table (ϕ30 mm × 2 mm) marked as CEM-Ⅰ. After dried for 24 h, thermal decomposition for 0.5 h at 800°C under a N2 atmosphere, CEM-Ⅱ was gained. Immersed in 40% HNO3 for 8 h [38], washed with distilled water until the wash water was neutral, and after air drying, CEM-Ⅲ was formed. Annealing at 300°C for 30 min and after air drying, CEM-Ⅳ was obtained. The above is the preparation method of Co-coal based electrode added with 5% cobalt nitrate powder tablet (Co-CE5). For comparison, Co-coal based electrode added with 2% cobalt nitrate powder tablet (Co-CE2) was fabricated under similar condition but with 2 wt% CoNO3 addition. CE was also obtained without cobalt addition.

Schematic diagram of preparation of Co-CE.

2.3 Characterizations of electrodes

2.3.1 Structural characterizations

The Co-CE was characterized by Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), in which the surface morphology was observed by SEM (Gemini Sigma 300 VP SEM, Zeiss) and the elements on the surface of the doped electrode were analyzed by EDS. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were conducted using an electrochemical workstation (CH1660D, Shanghai). The CV tests were carried out at a scan rate of 20, 50, 100 mV·s−1 in the range of −1.2 to 0 V, and a scan cycle of 50 cycles. The EIS measurement was carried out in a frequency range from 100 kHz to 0.01 Hz with an applied sine wave of 10 mV amplitude at Open circuit potential. All the electrochemical tests were performed in 10 mg·L−1 nitrate aqueous solution and 0.05 mol/L Na2SO4 (the Saturated calomel electrode as the reference electrode, the Dimension stable anode electrode as the counter electrode and the prepared electrodes as the working electrode). The absorbance of phenol at a specific wavelength of 510 nm was determined by the 4-aminoantipyrine spectrophotometric method (HJ 503-2009) using a VIS spectrophotometer (722 N, Shanghai Jinghua Technology Instrument Co., Ltd, China) and substituted into the standard curve equation to calculate the concentration of phenol.

2.3.2 Electrochemical experiments

Electrocatalytic degradation of phenol was carried out in a beaker with the working volume of 250 mL, equipped with a magnetic stirrer. The effective dimensions of the Co-CE in solution was 30 mm × 30 mm × 2 mm, and a graphite electrode (Gr) of the same effective area were used as the anode. The catalytic performance of the electrodes was performed in a simulated wastewater solution consisting of 200 mL, 0.05 mol/L Na2SO4 and 100 mg·L−1 phenol. At the beginning of treatment, the electrode was immersed in the electrolyte for 30 min to make it fully contact with the simulated solution to reach a stable state. The optimal electrode spacing between the working electrode were analysied in our previous work [39], before the systematic research of the electrode spacing between the electrodes, it was set as 20 mm in this experiment. Otherwise, the phenol wastewater was degraded by a constant current at a current density of 20 mA/cm2 for 180 min.

The electrochemical performance of Co-CE was evaluated by phenol degradation rate. The R is calculated by Eq. 1.

where C 0 is the initial phenol concentration and C t is the phenol concentration at specified time t.

The yield = the (actual) yield of the target product/the theoretical yield of the target product × 100%. Yield calculation of Co-CE in Eq. 2.

where m 1 is the mass of electrode plate before the reaction and m 2 is the mass of electrode plate after the reaction.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Electrode

3.1.1 Electrode treatment process

The efficiencies of the prepared Co-CE were assessed from the weight transformation. As can be observed in Figure 2, gravimetric analysis indicate that the thermal decomposition weightlessness rate is quite high, which is because the presence of oxygenated species in SJC and DCLR, and produced CO2, H2O, tars and other volatiles when subjected to high thermal decomposition temperature. With the continuous oxidation of electrode materials by HNO3, new micropores were etched on the electrode. In addition, previous infrared analysis results show that HNO3 treatment can improve the distribution of functional groups on the surface of coal-based electrode. With the extension of activation time, the content of oxygen-containing functional groups such as carboxyl, lactone and phenolic hydroxyl groups on the electrode surface gradually increases, which is also the source of activity in electrochemical reactions [38]. Moreover, the high concentration of HNO3 will etch the carbon skeleton, resulting in the collapse of the carbon structure surface and the yield will inevitably decrease. This is consistent with the results of SEM analysis, the lamella structures and pores were observed in microtopography of electrodes and the cobalt were successfully loaded in Co-CE.

The yield change of electrode preparation process.

3.1.2 Analysis of SEM-EDS

The SEM images of prepared two electrodes are shown in Figure 3. It can be seen from Figure 3(a) and (b) that the surface of the unsupported metal CE is observed to have less void structure and the surface is relatively flat. As showed in Figure 3(c) and (d), the Co element is uniformly distributed on the electrode. when treated by ball milling and carbonization process, the coal-based material particles are accumulated with carbon blocks in the sub-micron order, and microporous structures are observed owing to produced CO2, H2O, tars and other volatiles when pyrolyzing the electrode precursor, which would act as the pore-forming agents, thus leading to porous structures. Noted that some generated hole defects generated during the thermal decomposition can anchor active sites. Such microporous structures could cat as ion-buffering reservoirs, by increasing the ion transport channel to accelerate the penetration of electrolyte, and contribute to improved electrochemical performance. In addition, the elemental compositions of CE and Co-CE were revealed by element analysis, the detailed contents of which are showed in Figure 3(b) and (c), the result confirmed the existence of the metallic Co array on the coal-based support. It should be pointed out that concentrated HNO3 has efficiently washed off the interference metal and impurity.

SEM images of the electrode (a) and (b) of CE, (c) and (d) of Co-CE.

3.1.3 Analysis of CV and EIS

The effects of the added of Co on the electrochemical properties of the CE are studied. In order to evaluate the charge transfer effect of the electrode, EIS tests were carried out. The original curve and the fitted curve have been shown in all EIS plots. It can be seen that the EIS Nyquist diagram mainly includes the semicircle part of the high frequency region and the straight line part of the low frequency region. From Figure 4(a) and (b) it can seen that the Co enhanced the interaction of investigated compounds and the CE, indicating the Co would reinforce positive effect of increasing and activating active sites. The results of the increase in electrocatalytic activity were attributed to the changes in the structure and morphology of the Co-CE surface by chemical bonding of Co, which can affect the growth of grain. Cobalt doping increases the pore structure of the electrode material, which is beneficial to the electron transport inside the electrode, reduces Co3+ to Co2+, promotes the oxidation and reduction of cobalt, releases ·OH, and forms a stable cycle. Appropriate Co doped would also decrease the electrode’s electrochemical impedance and the diffusion impedance. The degrees of freedom (R ct) is related to the semicircle diameter of the EIS curve. With the decrease of the semicircle diameter of EIS curve, the charge transfer efficiency of the electrode is higher [40]. Clearly, the semicircle diameter of Co-CE on EIS curve was significantly smaller than that of CE. It demonstrated that Co-CE exhibited higher electron transfer ability in electrochemical oxidation, which was quite consistent with the results of CV tests.

Electrochemical testing of electrodes: (a) EIS Nyquist curves of CE (In 0.05 M Na2SO4), (b) EIS Nyquist curves of Co-CE (In 0.05 M Na2SO4), (c) CV curves of CE (In 0.05 M Na2SO4 and 0.1 g·L−1 phenol at a scan rate of 20, 50, 100 mV·s−1), (d) CV curves of Co-CE (In 0.05 M Na2SO4 and 0.1 g·L−1 phenol at a scan rate of 20, 50, 100 mV·s−1).

CV curves at different scan rates are tested to further explore their kinetic behaviors. Figure 4(c) and (d) shows the same pattern of CV corresponding to phenol on the electrode materials (CE, Co-CE), no obvious peak could be seen from the CV curves because of the characteristics of coal-based materials themselves. The CV curves of CE and Co-CE are fully preserved and show similar potential when the scan rate increases from 20 to 100 mV·s−1, implying good reversible property of the electrode. The Co-CE had an oxygen evolution potential (OEP) higher than CE, which suggested that the electrochemical catalytic performance of Co-CE was sightly higher than CE, The higher OEP is desirable because it reduces the occurrence of oxygen evolution reaction and is beneficial to the oxidation of organic matter by ·OH.

3.2 Selection of electrodes from removal rate of different electrodes

The phenol solution was electrolyzed using different electrodes under the experimental conditions of a current density of 20 mA/cm2 and an electrolyte of 0.05 mol/L anhydrous sodium sulfate. The electrodes include Gr, unsupported CE, Co-coal based electrode loaded with Co by hydrothermal method (Co-CE-Hy), Co-CE2, and Co-CE5.

Table 2 shows the R of phenol, respectively, with 180 min for different electrodes, it can be obtained that the anode using Gr is better than the CE. The cathode using the Co-CE5 is better than the Co-CE-Hy. The Co-CE-Hy loaded with the reactor can only be loaded on one side of the electrode and the loaded is easily shedding. The load layer will fall off when it encounters water, and the effect is not as good as the CE with cobalt nitrate powder. When the amount of cobalt nitrate added reaches 5%, the removal rate of volatile phenol in phenol reaches 47.64%. The results of previous studies show that the electrode degradation effect is different with different Co loading methods. When the loading is less than 5%, the electrode performance improved with the increase of Co loading. Therefore, the graphite electrode was used as the anode and the Co-CE5 was used as the cathode to explore the effect of Co-CE on the electrochemical removal of phenol.

Effect of different electrodes on electrochemical treatment of phenol

| Anode | Cathode | R (%) |

|---|---|---|

| CE | CE | 21.43 |

| CE | Co-CE-Hy | 27.17 |

| Gr | CE | 30.61 |

| Gr | Co-CE-Hy | 41.24 |

| Gr | Co-CE2 | 38.75 |

| Gr | Co-CE5 | 47.64 |

The Co-CE5 material has the highest degradation efficiency and the best degradation performance for phenol, which is consistent with the electrochemical test results and the previous characterization results. It shows that the combination of Co and CEM can produce more electrocatalytic active sites, accelerate the reduction process of O2, promote the conversion of hydrogen peroxide to ·OH, and improve the degradation rate of phenol. There is a certain gap in the degradation effect of composites with different Co contents, indicating that it is very important to select the appropriate composite ratio.

3.3 Effects of parameters on the degradation of phenol

3.3.1 Effect of electrolysis time

Figure 5 show the various variable parameters of the electrocatalytic degradation of 200 mL phenol by the Co-CE. Figure 5(a) shows after decorated with Co, the Co-CE shows a good activity for activation, and ∼48% phenol could be degraded in 180 min. The R increased slowly at 90–120 min, probably because the R increased, the electrocatalytic reaction generated more intermediate products, and the intermediate products could compete with phenol. The effect slows down the growth of phenol degradation rate. The R increased slowly at 150–180 min, because with the removal of phenol, the concentration of phenol in the solution decreased, the contact with ·OH was reduced, and the increase of R was reduced.

(a) Effect of electrolysis time (20 mA·cm−2 in 100 mg·L−1 phenol with 0.05 mol·L−1 Na2SO4); (b) effect of current density (100 mg·L−1 phenol with 0.05 mol·L−1 Na2SO4); (c) effect of Na2SO4 concentration (40 mA·cm2 in 100 mg·L−1 phenol); (d) effect of initial concentration (40 mA·cm−2 in 0.01 mol·L−1 Na2SO4); (e) effect of pH (40 mA·cm−2 in 100 mg·L−1 phenol with 0.01 mol·L−1 Na2SO4); (f) mechanical stability test.

3.3.2 Effect of current density

Current density is an important factor affecting phenol degradation. As shown in Figure 5(b), when no electric voltage is adopted, low R (15.73%) for 100 mg·L−1 phenol solution are observed after 180 min treatment. When improving current density, the R gain obvious improvement owing to the cooperative oxidization processes of the reactive free radicals and adsorption. When the current density was 5, 10, 20, 30 and 40 mA/cm2, the R of phenol were 40.64%, 41.04%, 44.21%, 44.63%, 47.64%. Appropriately increasing the current density can not only enhance the adsorption electrosorption capacity, but also accelerate the electron transport, rapidly reduce O2 to produce more H2O2 and ·OH, thereby improving the efficiency of pollutant removal [25]. Further improving the current density to 50 mA/cm2, the R at 180 min instead decreases (42.47%), Excessive current density will cause side reactions such as electron reaction (Eq. 3), hydrogen evolution reaction (Eq. 4) and decomposition reaction (Eq. 5) in the electrocatalytic system, resulting in more intermediate products. The gas generated by the side reaction brings stirring to the solution, resulting in a decrease in the thickness of the diffusion layer, thereby reducing the mass transfer coefficient, thus hindering the conversion of H2O2 to ·OH during the degradation process. At the same time, excessive current will also cause the increase of resistance value in the system, thus affecting the degradation effect of phenol. In this experiment, the optimal current density for phenol degradation was 40 mA/cm2.

3.3.3 Effect of electrolyte concentration

The relationship between electrolyte and conductivity is very close, which has an important influence on the degradation of pollution. Studies have shown that the electrolyte concentration will significantly affect the performance of electrochemical treatment of organic wastewater. As shown in Figure 5(c), with the increase of electrolyte concentration from 0.01 to 0.5 mol/L, the R of phenol decreased from 53.95% to 41.47%. The phenomenon can be explained by that the excess Na2SO4 will cover the surface of the electrode, and block the pores, resulting in the decline of R. Although the high concentration of Na2SO4 can improve the conductivity of the solution, excessive Na2SO4 will lead to the adsorption of

3.3.4 Effect of initial phenol concentration

The R of adsorption coupled with the electrochemical reduction process at different phenol concentrations are provided in Figure 5(d). It can be found that with the increase of the phenol concentration from 20 to 100 mg·L−1, the R increased from 51.06% to 53.95% at 180 min. This is because when the initial concentration of phenol is low, a sufficient amount of ·OH can oxidize phenol. The increase of concentration helps the diffusion of phenol, and the free radicals fully contact with the pollutants, thereby accelerating the degradation rate of phenol [7]. Above 100 mg·L−1, removal after 180 min treatment show a decline trend. This is because the electrochemical degradation ability of the electrode is limited when facing an aqueous solution with a high concentration of phenol. At the same current density, the number of strong oxidizing groups generated during the electrolysis process remains unchanged. For the same number of active species, the change of degradation rate increases with the increase of the number of organic molecules. With the degradation of some phenol, a large number of intermediate products will be produced. Due to the non-selective oxidation of ·OH, the competition between phenol and other intermediate products is fierce, and the oxidation reaction of active particles becomes more complicated, which reduces the degradation rate [41].

3.3.5 Effect of pH

The influence of the pH on the degradation efficiency depends on several factors, such as the type of oxidizing species and its oxidizing ability. In order to avoid the contamination of foreign anions, dilute H2SO4 and NaOH solutions were used for pH adjustment. Figure 5(e) shows the effect of initial pH on the degradation of phenol in the range of 2–11. A change in the pH from acidic to alkaline pH reduced the R of phenol from 67.84% to 47.54% for 180 min. The maximum R was obtained at pH 2. A decreasing trend of the R was observed above pH 2. According to the previous literature reference [42,43], this phenomenon may be due to the decrease of OEP with the increase of pH. The higher OEP value under acidic conditions weakens the side reaction of oxygen evolution and promotes the indirect catalytic degradation of phenol by ·OH. Under alkaline conditions, ·OH shows weaker reactivity, and has stronger oxidation ability under acidic conditions than under alkaline conditions.

3.3.6 Stability test of Co-CE

Stability is the key factor to determine the application of Co-CE. Stability of the Co-CE for phenol removal was analyzed through the repetitive experiments for phenol removal and was show in Figure 5(f), which was tested by ultrasonic oscillation. Weight loss rate of phenol in every 30 min were 3.49%, 6.37%, 7.30%, 7.52%, respectively. Besides, the Co-CE maintained the same structure after 180 min reaction. The total loss rate in each cycle were lower than 10%, indicating that the structure of Co-CE is relatively stable, and there is a certain weight loss, which can be controlled within 10%. Because the electrode is prepared by pressing the pulverized coal, there is a phenomenon of particle shedding during the electrolysis process. Through multiple sets of experimental verification, as shown in Table 2, when the electrode stability is 15%, the removal effect can reach 88.3%. The loss rate is determined to be less than 10%, thus, there will be a higher R. The above results suggested that Co-CE maintained a satisfying stability (Table 3).

Effect of loss rate on phenol removal process

| Loss rate (%) | R (%) |

|---|---|

| 15.00 | 88.30 |

| 13.20 | 88.65 |

| 10.74 | 89.02 |

| 8.35 | 89.73 |

3.4 Process optimization by RSM

3.4.1 Statistical analysis

The RSM was used to design the required experiments to determine the optimal conditions and the effects of independent variables on the response performance of the electrochemical process (phenol removal). According to the results of single factor experiment, the experimental area was determined roughly, the further optimal experiment were conducted as Table 4. Factors of A (processing time), B (current density), C (electrolyte concentration), D (pH) and E (initial phenol concentration) were list, as well as the value interval. The results of 21 runs of the experiment were obtained from RSM. It was shown in Table 5 taking R as the response value.

Range of variables

| Factors | Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 0 | 1 | |

| A (min) | 150 | 180 | 210 |

| B (mA/cm2) | 20 | 35 | 50 |

| C (mol/L) | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.10 |

| D | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| E (mg·L−1) | 50.0 | 100.0 | 150.0 |

Design of experiment and experimental response for electrochemical reduction runs

| No. | A | B | C | D | E | R (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 59.11 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 54.94 |

| 3 | −1 | 1 | 0 | −1 | 1 | 61.69 |

| 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | −1 | 67.6 |

| 5 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 53.52 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 63.22 |

| 7 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 76.15 |

| 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 76.87 |

| 9 | −1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 76.40 |

| 10 | 1 | 0 | −1 | 1 | 0 | 77.74 |

| 11 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 68.4 |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 77.27 |

| 13 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 43.25 |

| 14 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 74.29 |

| 15 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 64.96 |

| 16 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 77.97 |

| 17 | 0 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 70.06 |

| 18 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 77.61 |

| 19 | 0 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 77.19 |

| 20 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | −1 | 83.47 |

| 21 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 70.05 |

3.4.2 ANOVA and effect test of regression model

The ANOVA results revealed an excellent agreement between the experimental results and predicted values of phenol degradation efficiency. The regression surface model was used to explore and predict the interaction of various process variables on the removal efficiency [44]. The degree of importance and efficiency of the suggested response model were determined by P-value, Correlation coefficient (R 2), F-value and adjusted R 2, as described in Table 6.

ANOVA results for coefficient of quadratic model for phenol removal

| Source | DF | Sum of squares | Mean square | F-value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 17 | 2062.8486 | 121.344 | 25.4151 | 0.0108* |

| A | 1 | 370.71903 | 77.6460 | 0.0031* | |

| B | 1 | 1.70661 | 0.3574 | 0.5921 | |

| C | 1 | 44.72570 | 9.3677 | 0.0550 | |

| D | 1 | 390.64124 | 81.8187 | 0.0029* | |

| E | 1 | 369.78176 | 77.4497 | 0.0031* | |

| A 2 | 1 | 73.32053 | 15.3568 | 0.0295* | |

| B 2 | 1 | 247.75007 | 51.8905 | 0.0055* | |

| C 2 | 1 | 0.01542 | 0.0031 | 0.9583 | |

| D 2 | 1 | 107.93647 | 22.6070 | 0.0177* | |

| E 2 | 1 | 411.13534 | 86.1111 | 0.0026* | |

| A*D | 1 | 0.69084 | 0.1447 | 0.7290 | |

| B*D | 1 | 56.33118 | 11.7984 | 0.0414* | |

| C*D | 1 | 423.27825 | 88.6544 | 0.0025* | |

| A*E | 1 | 26.66704 | 5.5853 | 0.0991 | |

| B*E | 1 | 23.19302 | 4.8577 | 0.1147 | |

| C*E | 1 | 72.74173 | 15.2355 | 0.0299* | |

| D*E | 1 | 49.14879 | 10.2941 | 0.0490 | |

| Pure error | 3 | 14.3234 | 4.774 | ||

| Cor total | 20 | 2077.1721 | |||

| R 2 = 0.993104 | |||||

| Adjusted R 2 = 0.954029 | |||||

*Significant influencing factors.

With the help of the phenol grading removal model proposed by RSM, the phenol removal amount of any combination of five parameters can be predicted within the experimental influence range. The significance and sufficiency of phenol removal factors and their interactions were analyzed by p-test [45]. In this study, all the independent variables such as A, D, E, A 2, B 2, D 2, E 2, B*D, C*D, C*E and D*E have P-values lower than 0.05 are obtained as significant model terms for phenol degradation and obtain a model. The order of these key factors is C*D > E 2 > D > A = E > B 2 > D 2 > A 2 > C*E > B*D > D*E. The factors in the front of the order will have a significant impact on the wastewater treatment experiment. The interaction between the two factors in the two-factor influence factor is obviously not a simple linear relationship. We will analyze it through the quadratic regression surface.

3.4.3 RSM optimization and verification

The response of R was determined to study the influence of process operation variables over the response. The RSM was used to analyze the experimental data in Table 4. After eliminating the insignificant items, a quadratic regression surface model was established to fit the experimental results, which correlates all process parameters [16]. The model equation was obtained for the response can be represented in terms of coded factors as follows:

Where X 1 = (A − 180)/30, X 2 = (B − 35)/15, X 3 = (C − 0.055)/0.045, X 4 = (D − 3.5)/1.5, X 5 = (E − 100)/50. In above equation, as mentioned earlier, R has been employed to show the removal rate (%), and A, B, C, D and E are utilized to symbolize the time, current density, electrolyte concentration, pH and initial phenol concentration, respectively. The codes X 1, X 2, X 3, X 4, X 5 are used to represent the algebraic expressions of time, current density, electrolyte concentration, initial phenol concentration and pH, so that the variable factor interval is kept within −1 to 1 to express the prediction model.

The three-dimensional response surface diagram can solve the problem of the optimal conditions of the factors, and is mainly used to establish the understanding of the interaction types between variables, which can be used to improve the efficiency of process treatment. Figure 6(a–d) represents the interaction of two independent parameters in the significant influencing factors. It can be seen from Figure 6(a) that if all other variables are kept unchanged, if pH (2–5) is increased, the degradation rate will increase slightly and then decrease, and the R is the highest when pH is 3. If the concentration of phenol (50–100 mg·L−1) is increased, the degradation rate will decrease first and then increase slightly. It can be seen from Figure 6(c) and (d) that the R is the highest when the concentration of phenol is 50 mg·L−1. Although other conditions remain unchanged, the electrolyte concentration increases (0.01–0.1 mol/L), and the degradation rate decreases slightly. However, compared with Figure 6(c) and (d), it is found that when the two factors interact, the R is the highest when the electrolyte concentration is 0.1 mol/L. In summary, the optimum electrochemical treatment conditions were current density of 35 mA/cm2, Na2SO4 concentration of 0.1 mol/L, pH = 3, and initial phenol concentration of 50 mg·L−1. The model data showed that the highest R was 90.86% under this condition. Thereafter, there paralleled experiments were performed in the laboratory with the optimal parameters and the R was 91.2%, 89.3% and 91.05%, it is depicted that the predicted values of RSM is very close of experimental values.

Two-factor response surface diagram: (a) X 2*X 4, (b) X 3*X 4, (c) X 3*X 5, (d) X 4*X 5.

3.5 Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation mechanism

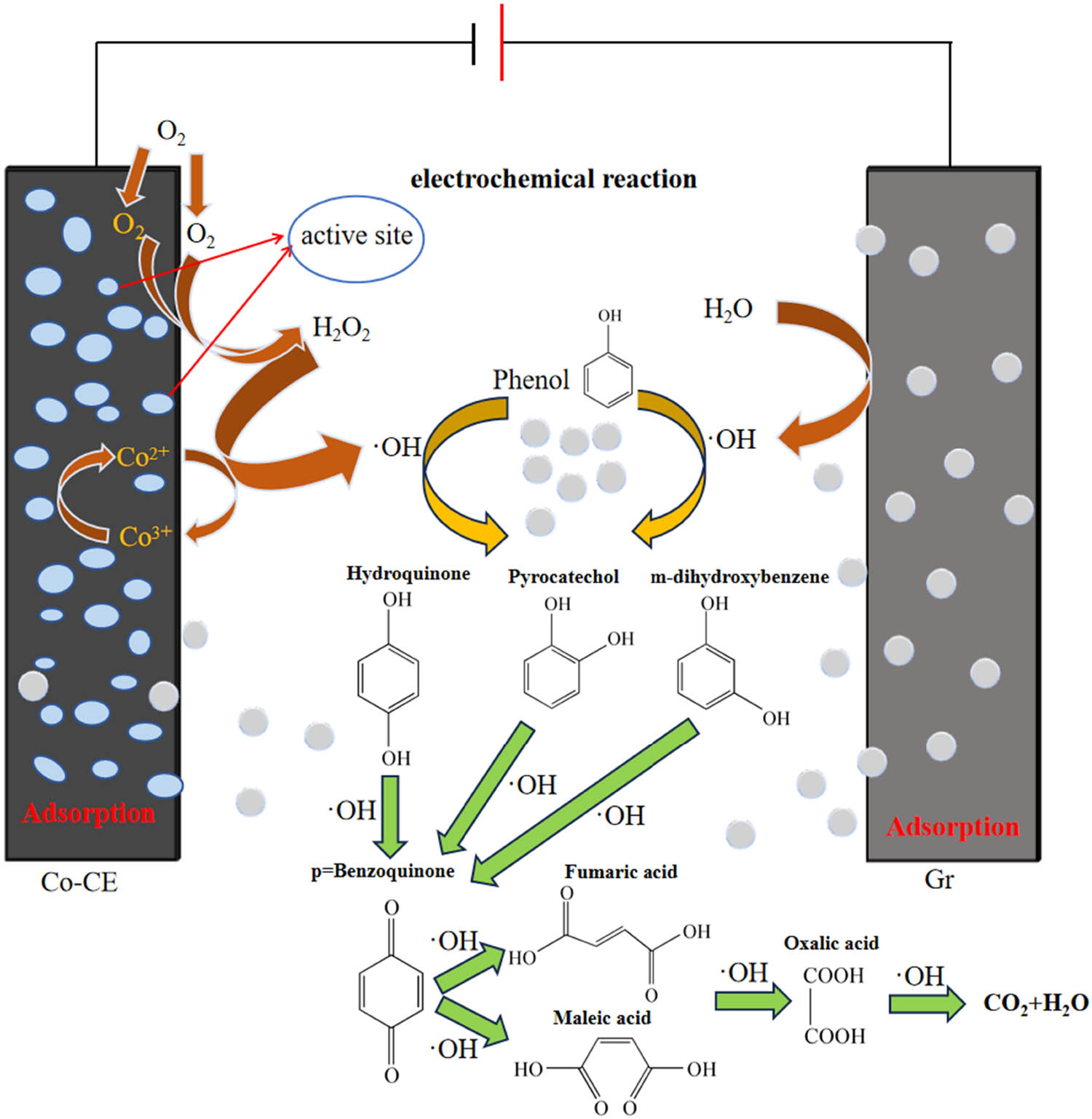

Studies have shown that H2O2 and ·OH play an important role in cathodic electrocatalytic oxidation. The direct conversion from H2O2 to ·OH is usually difficult [27]. The simultaneous presence of Co2+ and Co3+ and the redox reaction promote the production of H2O2 and ·OH (as follows Eqs. 6 and 7). Studies have shown that, similar to Fe2+, Co2+ can also in situ activate H2O2 decomposition to produce ·OH, and achieved good treatment effect [46]. The H2O2 produced by the cathode reacts rapidly with the transition metal element Co2+, which promotes the conversion of H2O2 to strong oxidizing substances, making phenol more easily mineralized into CO2 and water. The introduction of Co species not only acts as a catalyst for the redox process, but more importantly promotes the valence cycle. The production of ·OH is increased by accelerating the redox cycle between Co species, thereby achieving enhanced mineralization of phenol.

Based on the above analysis, a reasonable electrocatalytic mechanism for removing phenol was proposed. As a highly effective adsorbent and electrocatalyst, the pores of Co-CE are abundant, forming a micro-electric field in the pores, which promotes the reaction of adsorbed water with oxygen to produce hydrogen peroxide. The porous structure provides more active sites for the reaction and has better degradation effect. The improved electrochemical resulting from Co doping sites and CE hierarchical pores, efficiently facilitate the conversion of H2O2 to ·OH. The in-situ generated H2O2 were catalyzed with Co-CE, and much more ·OH were quickly produced through the active sites of Co(ii) on the Co-CE surface. Under the optimal operating conditions, the removal rate obtained by phenol was nearly 91%. Meanwhile, adsorption rate obtained by electrode was 15.73%. There are white adhesions on the cathode surface, and it is irregularly crystallized, indicating that in addition to adsorption, redox reaction also occurs [47]. Hence, the total phenol removal should be the result of synergistic adsorption and electrocatalytic oxidation.

The mechanism of synergistic adsorption/electrocatalytic oxidation by Co-CE with multi-hole structure was expounded in Figure 7. As above experimental results, For the Co-CE, phenol was first adsorbed on the surface for its multi-hole structure, At the same time, O2 adsorbed on Co-CE surface is reduced to H2O2 by electrons (as follows Eq. 8) and the redox reaction between Co2+ and Co3+ promotes the conversion of H2O2 to ·OH potent oxidizing substances, then, a part of phenol was adsorbed inside the electrode and a part of phenol was effectively oxidized to intermediate product, finally was degradation into CO2 and H2O. In the electrolytic solution, ·OH was produced at both cathode and anode, this makes it easier to mineralize the organic pollutant phenol into carbon dioxide and water. Wang studied the mechanism of electro-oxidation of phenol in aqueous phase based on in-situ infrared spectroscopy. It was found that different potentials affected the oxidation products of phenol [48]. Some researchers [7,44,48] believed that phenol was first oxidized to pyrogallol and further changed to quinone, and then oxidized to small molecule acid, which was decomposed into CO2 and H2O (as follows Eq. 9). Due to the large potential range of the experiment, it is speculated that both of them exist in the process of electro-oxidation decomposition, and the possible oxidation pathway is shown in Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of phenol degradation mechanism in electrochemical system.

4 Conclusion

Co-CE was successfully prepared to study the efficiency of electrocatalytic degradation of phenol. Comparing different electrodes, it was found that graphite as anode, Co-CE5 as cathode had the best phenol degradation effect, and R was 47.64%. The single factor degradation experiments of phenol in simulated wastewater was carried out to determine the following optimal reaction conditions: the time was 180 min, the applied current density was 40 mA/cm2, the electrode concentration was 0.01 mol/L, the initial pH was 2, the initial phenol concentration was 100 mg·L−1 and the R were at the range of 47.64–67.84%. The results of ANOVA obtained from RSM showed that the quadratic polynomial model with R 2 = 0.993 was suitable and logical for accurate prediction of phenol removal by electrochemical process. The independent variables include A, D, E, Under optimal conditions for time, current density, pH, electrolyte concentration, initial phenol concentration were 180 min, 35 mA/cm2, 3, 0.1 mol/L, 100 mg·L−1, the R of three parallel experiments were nearly predicting value (91.2%, 89.3%, 91.05%). The redox reaction between Co2+ and Co3+ promotes the conversion of H2O2 to ·OH potent oxidizing substances, both anode and cathode produce ·OH, ·OH attacks the benzene ring to degrade phenol, and adsorption synergistic electrocatalysis accelerates the mineralization of pollutants. This high catalytic activity and low cost Co-CE is a kind of prospective electrode for electrochemical degradation of phenolic wastewater. It is also of great significance for industrial application and provides a feasibility for coal chemical wastewater treatment. However, it is in a bottleneck period in achieving large-scale industrial applications.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful for the financial support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22065035), and the Science and Technology Foundation of Yulin (CXY202110104).

-

Funding information: This work was supported by: National Natural Science Foundation of China [National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant numbers: 22065035]; the Joint foundation of Clean Energy Innovation Institute and Yulin University [Yulin Finance Bureau, grant numbers: Grant. YLU-DNL Fund 2021003]; the Science and Technology Foundation of Yulin [Yulin Science and Technology Bureau, grant numbers: CXY202110104].

-

Author contributions: Ting Su: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing; Mengdan Wang: conduction of experiment; Bozhou Xianyu: editing; Wenwen Gao: data curation and software; Yanli Gao: formal analysis and investigation; Pingqiang Gao: conceptualization, methodology; Cuiying Lu: project administration, visualization.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Almasi A, Dargahi A, Amrane A, Fazlzadeh M, Mahmoudi M, Hashemian A. Effect of the retention time and the phenol concentration on the stabilization pond efficiency in the treatment of oil refinery wastewater. Fresen Environ Bull. 2014;23(10):2541–8.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Kadhum ST, Alkindi GY, Albayati TM. Remediation of phenolic wastewater implementing nano zerovalent iron as a granular third electrode in an electrochemical reactor. Int J Environ Sci Technol. 2022;19(3):1383–92. 10.1007/s13762-021-03205-5.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Shokoohi R, Movahedian H, Dargahi A, Jafari AJ, Parvaresh A. Survey on efficiency of BF/AS integrated biological system in phenol removal of wastewater. Desalin Water Treat. 2017;82:315–21. 10.5004/dwt.2017.20957.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Divya N, Sreerag AV, Yadukrishna, Joseph T, Soloman PA. A study on electrochemical oxidation of phenol for wastewater remediation. Iop Conf Ser-Mater Sci. 2021;1114(1):012073. 10.1088/1757-899X/1114/1/012073.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Mei X, Li J, Jing C, Fang C, Liu Y, Wang Y, et al. Separation and recovery of phenols from an aqueous solution by a green membrane system. J Clean Prod. 2020;251:119675. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119675.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Jia Z, Zhao X, Yu C, Wan Q, Liu Y. Design and properties of Sn–Mn–Ce supported activated carbon composite as particle electrode for three-dimensionally electrochemical degradation of phenol. Environ Technol Innov. 2021;23:101554. 10.1016/j.eti.2021.101554.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Zhou Q, Liu D, Yuan G, Tang Y, Cui K, Jiang S, et al. Efficient degradation of phenolic wastewaters by a novel Ti/PbO2-Cr-PEDOT electrode with enhanced electrocatalytic activity and chemical stability. Sep Purif Technol. 2022;281:119735. 10.1016/j.seppur.2021.119735.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Golestanifar H, Asadi A, Alinezhad A, Haybati B, Vosoughi M. Isotherm and kinetic studies on the adsorption of nitrate onto nanoalumina and iron-modified pumice. Desalin Water Treat. 2016;57(12):5480–7. 10.1080/19443994.2014.1003975.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Dargahi A, Samarghandi MR, Shabanloo A, Mahmoudi MM, Nasab HZ. Statistical modeling of phenolic compounds adsorption onto low-cost adsorbent prepared from aloe vera leaves wastes using CCD-RSM optimization: effect of parameters, isotherm, and kinetic studies. Biomass Conv Bioref. 2023;13(9):7859–73. 10.1007/s13399-021-01601-y.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Mohammadifard A, Allouss D, Vosoughi M, Dargahi A, Moharrami A. Synthesis of magnetic Fe3O4/activated carbon prepared from banana peel (BPAC@Fe3O4) and salvia seed (SSAC@Fe3O4) and applications in the adsorption of Basic Blue 41 textile dye from aqueous solutions. Appl Water Sci. 2022;12(5):88. 10.1007/s13201-022-01622-6.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Pourali P, Rashtbari Y, Behzad A, Ahmadfazeli A, Poureshgh Y, Dargahi A. Loading of zinc oxide nanoparticles from green synthesis on the low cost and eco-friendly activated carbon and its application for diazinon removal: isotherm, kinetics and retrieval study. Appl Water Sci. 2023;13(4):101. 10.1007/s13201-023-01871-z.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Peyghami A, Moharrami A, Rashtbari Y, Afshin S, Vosuoghi M, Dargahi A. Evaluation of the efficiency of magnetized clinoptilolite zeolite with Fe3O4 nanoparticles on the removal of basic violet 16 (BV16) dye from aqueous solutions. J Disper Sci Technol. 2023;44(2):278–87. 10.1080/01932691.2021.1947847.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Lin YH. Kinetics of cometabolic transformation of 4-chlorophenol and phenol degradation by pseudomonas putida cells in batch and biofilm reactors. Processes. 2021;9:1663. 10.3390/pr9091663.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Luo H, Liu G, Zhang R, Jin S. Phenol degradation in microbial fuel cells. Chem Eng J. 2009;147:259–64. 10.1016/j.cej.2008.07.011.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Honarmandrad Z, Javid N, Malakootian M. Removal efficiency of phenol by ozonation process with calcium peroxide from aqueous solutions. Appl Water Sci. 2021;11:14. 10.1007/s13201-020-01344-7.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Zulfiqar M, Samsudin MFR, Sufian S. Modelling and optimization of photocatalytic degradation of phenol via TiO2 nanoparticles: An insight into response surface methodology and artificial neural network. J Photochem Photobiol A. 2019;384:112039. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2019.112039.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Seid-Mohammadi A, Ghorbanian Z, Asgari G, Dargahi A. Photocatalytic degradation of metronidazole (MNZ) antibiotic in aqueous media using copper oxide nanoparticles activated by H2O2/UV process: Biodegradability and kinetic studies. Desalin Water Treat. 2020;193:369–80. 10.5004/dwt.2020.25772.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Bar-Niv N, Azaizeh H, Kuc ME, Azerrad S, Haj-Zaroubi M, Menashe O, et al. Advanced oxidation process UV-H2O2 combined with biological treatment for the removal and detoxification of phenol. J Water Process Eng. 2022;48:102923. 10.1016/j.jwpe.2022.102923.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Mokhtari SA, Gholami M, Dargahi A, Vosoughi M. Removal of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) from contaminated sewage sludge using advanced oxidation process (hydrogen peroxide and sodium persulfate). Desalin Water Treat. 2021;213:311–8. 10.5004/dwt.2021.26716.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Dargahi A, Moradi M, Hasani K, Vosoughi M. Improved degradation of tetracycline antibiotic in electrochemical advanced oxidation processes (EAOPs): bioassay using bacteria and identification of intermediate compounds. Int J Chem React Eng. 2023;21(2):205–23. 10.1515/ijcre-2022-0041.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Afshin S, Rashtbari Y, Ramavandi B, Fazlzadeh M, Vosoughi M, Mokhtari SA, et al. Magnetic nanocomposite of filamentous algae activated carbon for efficient elimination of cephalexin from aqueous media. Korean J Chem Eng. 2020;37(1):80–92. 10.1007/s11814-019-0424-6.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Gan L, Wu Y, Song H, Lu C, Zhang S, Li A. Self-doped TiO2 nanotube arrays for electrochemical mineralization of phenols. Chemosphere. 2019;226:329–39. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.03.135.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Salman RH, Hafiz MH, Abbas AS. Preparation and characterization of graphite substrate manganese dioxide electrode for indirect electrochemical removal of phenol. Russ J Electrochem. 2019;55:407–18. 10.1134/S1023193519050124.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Martínez-Huitle CA, Rodrigo MA, Sirés I, Scialdone O. Single and coupled electrochemical processes and reactors for the abatement of organic water pollutants: a critical review. Chem Rev. 2015;115(24):13362–407. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00361.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Saputera WH, Putrie AS, Esmailpour AA, Esmailpour AA, Sasonngko D, Suendo V, et al. Technology advances in phenol removals: current progress and future perspectives. Catalysts. 2021;11(8):99. 10.3390/catal11080998.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Fan L, Gong Y, Wan J, Wei Y, Shi H, Liu C. Flower-like molybdenum disulfide decorated ZIF-8-derived nitrogen-doped dodecahedral carbon for electro-catalytic degradation of phenol. Chemosphere. 2022;298:134315. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134315.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Salazar-Banda GR, Santos GDOS, Duarte Gonzaga IM, Dória AR, Barrios Eguiluz KI. Developments in electrode materials for wastewater treatment. Curr Opin Electrochem. 2021;26:100663. 10.1016/j.coelec.2020.100663.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Li Y, Chen X, Zeng Z, Dong Y, Yuan S, Zhao W, et al. Coal-based electrodes for energy storage systems: Development, challenges, and prospects. ACS Appl Energy Mater. 2022;5(6):7874–88. 10.1021/acsaem.2c01423.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Guo X, Chen C, Zhang Y, Xu Y, Pang H. The application of transition metal cobaltites in electrochemistry. Energy Storage Mater. 2019;23:439–65. 10.1016/j.ensm.2019.04.017.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Yousif SH, Abdullah GH. Development of a new process for phenol in situ oxidation using a bifunctional cathode reactor. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2023;62(12):4905–16. 10.1021/acs.iecr.2c04263.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Wang Y, Shen C, Li L, Li H, Zhang M. Electrocatalytic degradation of ibuprofen in aqueous solution by a cobalt-doped modified lead dioxide electrode: influencing factors and energy demand. RSC Adv. 2016;6(36):30598–610. 10.1039/C5RA27382J.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Akhtar A, Akram K, Aslam Z, Ihsanullah I, Baig N, Bello MM. Photocatalytic degradation of p‐nitrophenol in wastewater by heterogeneous cobalt supported ZnO nanoparticles: Modeling and optimization using response surface methodology. Environ Prog Sustain. 2023;42(2):e13984. 10.1002/ep.13984.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Yu Z, Hao J, Li W, Liu H. Enhanced Electrochemical Performances of Cobalt-Doped Li2MoO3 Cathode Materials. Materials. 2019;12(6):843. 10.3390/ma12060843.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Law HH, Sapjeta J. Effect of cobalt on fibrous nickel hydroxide electrodes. J Electrochem Soc. 1989;136(6):1603–6. 10.1149/1.2096976.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Chang Z, Zhao Y, Ding Y. Effects of different methods of cobalt addition on the performance of nickel electrodes. J Power Sources. 1999;77:69–73. 10.1016/S0378-7753(98)00174-8.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Pourali P, Fazlzadeh M, Aaligadri M, Dargahi A, Poureshgh Y, Kakavandi B. Enhanced three-dimensional electrochemical process using magnetic recoverable of Fe3O4@GAC towards furfural degradation and mineralization. Arab J Chem. 2022;15(8):103980. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.103980.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Su T, Lan X, Song Y, Gao W, Jing X. Effects of KOH addition methods on structure and properties of coal-based electrode material. Coal Conversion. 2020;43(3):73–80. 10.19726/j.cnki.ebcc.202003011.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Ting S, Yonghui S, Shan Z, Yuhong T, Xinzhe L. Influence of nitric acid activation time on the structure and property of coal-based electrode materials. Mater Rep. 2018;32(2):528–32. 10.11896/j.issn.1005-023X.2018.04.004.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Su T, Gao W, Xing X, Lan X, Song Y. Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3 -N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method. Green Process Synth. 2021;10(1):756–67. 10.1515/gps-2021-0072.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Xu J, Liang X, Fan X, Song Y, Zhao Z, Hua J, et al. Highly enhanced electrocatalytic activity of nano-TiO2/Ti membrane electrode for phenol wastewater treatment. J Mater Sci-Mater Electron. 2020;31(16):13511–20. 10.1007/s10854-020-03907-5.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Lei S, Song Y. Study on electrosorption behavior of weak metal cyanide complex ions based on coal-based electrode. Arab J Chem. 2023;16(8):104981. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.104981.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Lingfeng Q, Erling N. Preparation of dimensionless stable anode in the electro-catalytic oxidation and its phenol degrading characteristics. Environ Chem. 2010;29(6):1019–26.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Zambrano J, Park H, Min B. Enhancing electrochemical degradation of phenol at optimum pH condition with a Pt/Ti anode electrode. Environ Technol. 2020;41(24):3248–59. 10.1080/09593330.2019.1649468.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Cai J, Zhou M, Pan Y, Du X, Lu X. Extremely efficient electrochemical degradation of organic pollutants with co-generation of hydroxyl and sulfate radicals on Blue-TiO2 nanotubes anode. Appl Catal B-Environ. 2019;257:117902. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.117902.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Yonghui S, Siming L, Ning Y, Wenjin H. Treatment of cyanide wastewater dynamic cycle test by three-dimensional electrode system and the reaction process analysis. Environ Technol. 2021;42(11):1693–702. 10.1080/09593330.2019.1677783.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Min SJ, Kim JG, Baek K. Role of carbon fiber electrodes and carbonate electrolytes in electrochemical phenol oxidation. J Hazard Mater. 2020;400:123083. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123083.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Li B, Sun JD, Tang C, Yan ZY, Zhou J, Wu XY, et al. A novel core-shell Fe@Co nanoparticles uniformly modified graphite felt cathode (Fe@Co/GF) for efficient bio-electro-Fenton degradation of phenolic compounds. Sci Total Environ. 2021;760:143415. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143415.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Wang J, Yuan T, Zhou D, Zhou X, Gan Y. Mechanism of phenol electro-oxidation in aqueous solution based on in situ infrared spectroscopy. CIESC J. 2019;70(12):4821–7. 10.11949/0438-1157.20190689.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones