Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

-

Fayez M. Saleh

Abstract

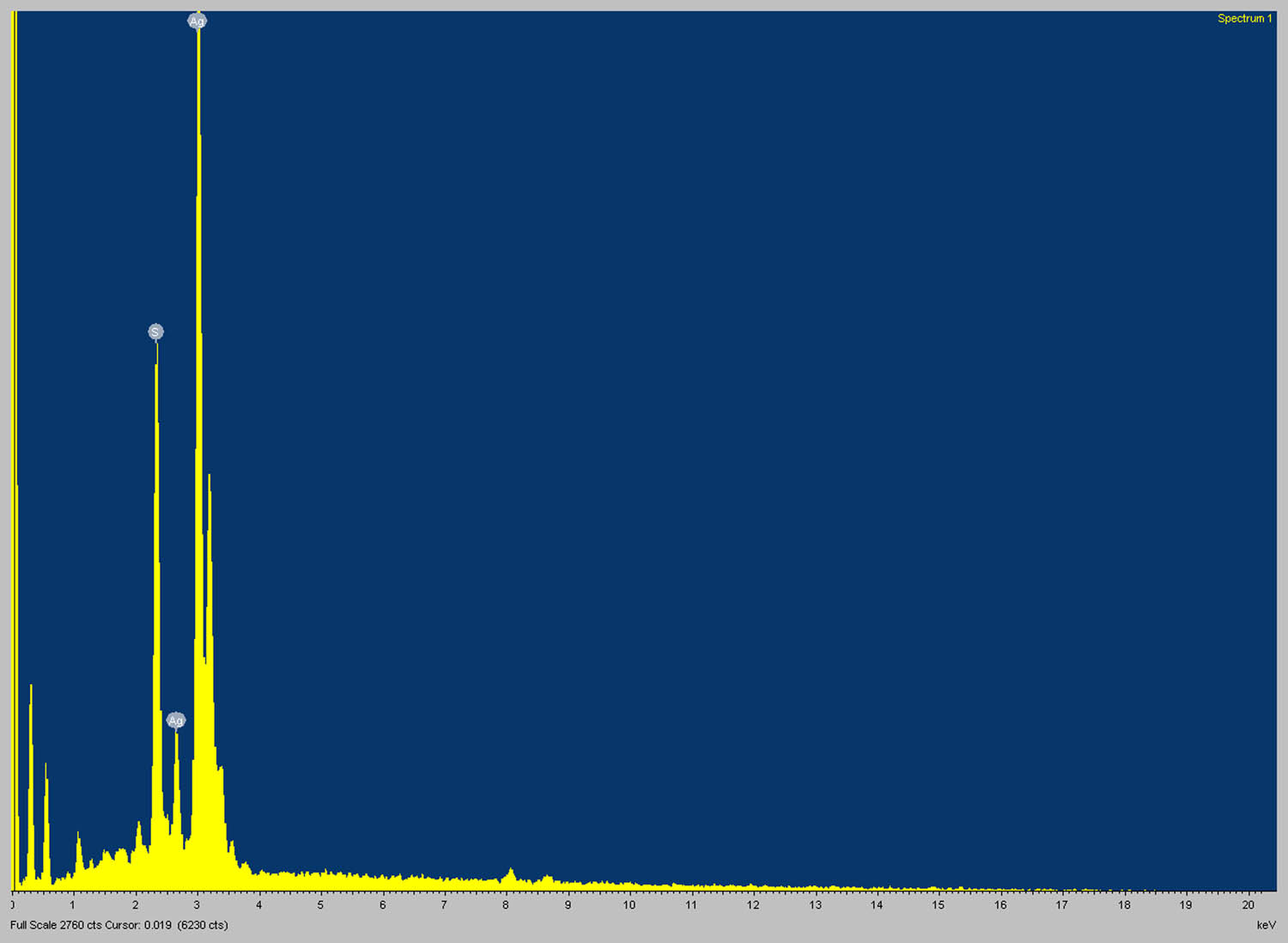

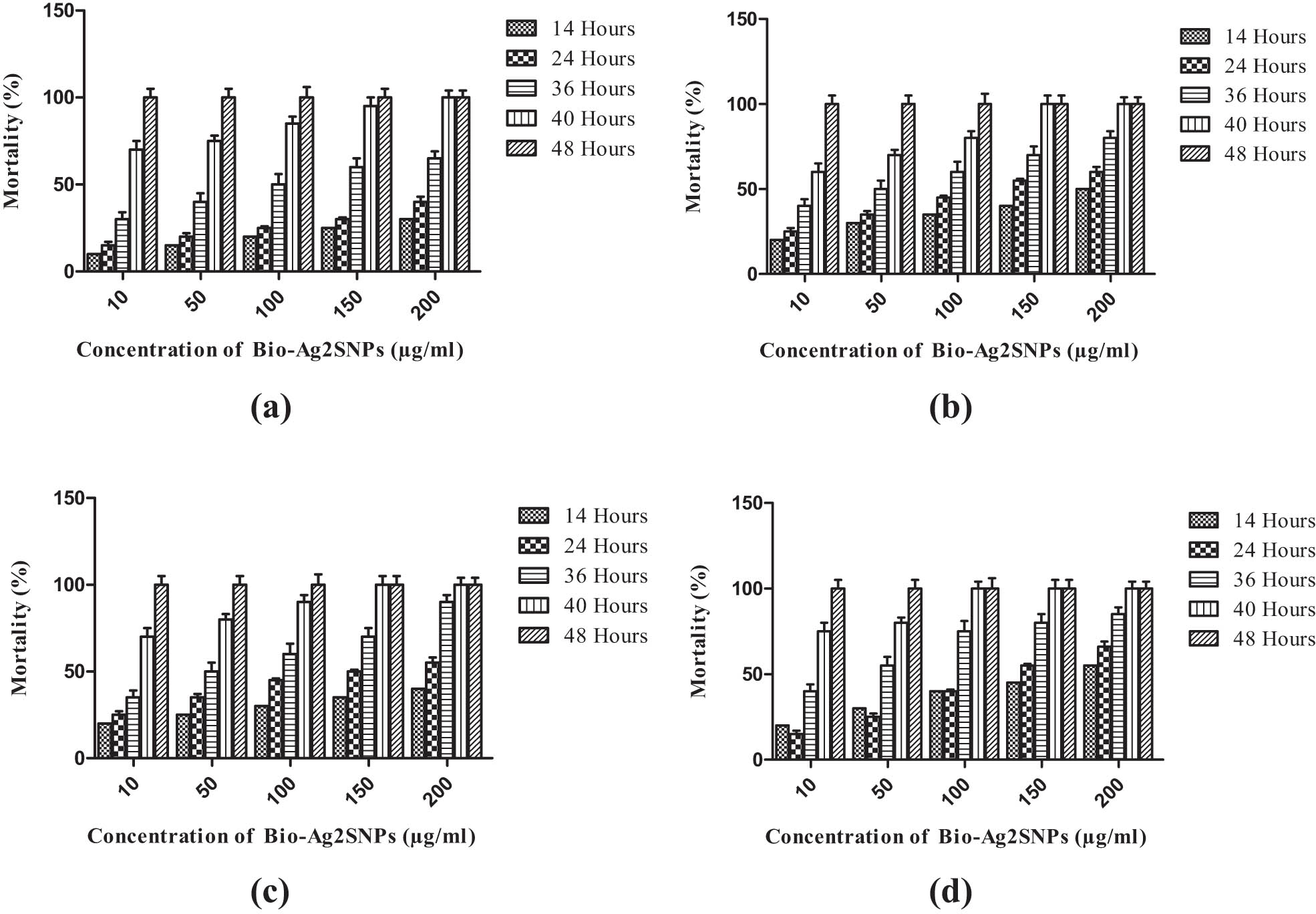

In this research, cell-free extracts from magnesite mine-isolated actinobacterial strain (M10A62) were used to produce silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2SNPs). Streptomyces minutiscleroticus JX905302, actinobacteria capable of producing Ag2SNPs, was used to synthesize Ag2NPs. The UV–vis range was used to confirm the biosynthesized Ag2NPs; Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), atomic force microscopy (AFM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDAX), and dynamic light scattering analysis were employed to characterize them further. Surface resonance plasma (SRP) for Ag2SNPs was obtained at 355 nm using UV–visible spectroscopy; FT-IR detected bimolecular and eventually microbial-reduced Ag2SNPs from S. minutiscleroticus culture extract. Furthermore, AFM and TEM analysis confirms that the synthesized Ag2SNPs were spherical in shape. Dynamic light scattering revealed a negatively charged Ag2NPs surface with a diameter of 10 nm. The XRD spectrum showed the crystalline nature of the obtained particles. EDAX revealed a pure crystalline nature, and a significant silver particle signal confirms the presence of metallic silver and sulfide nanoparticles together with the signals of Cu and C atoms. After 40 and 48 h of treatment at 150–200 µg·ml−1, Ag2SNPs produced the highest mortality in Spodoptera litura, H. armigera, Aedes aegypti, and Culex quinquefasciatus larvae. Hence, the biosynthesized Ag2SNPs may be useful for potential pest control in integrated pest management and vector control program as a safer, cost-effective, selective, and environmentally friendly approaches.

1 Introduction

The focus of nanoparticles is on the development of nanotechnology in several fields, such as material science, medical, agricultural, and environmental remediation [1,2]. Nanoparticles (NPs) have increased catalytic, mechanical, optical, and magnetic properties due to their high surface area-to-volume ratio [3]. Among various nanomaterials (gold, silver, copper, iron, aluminum, cobalt, titanium, and zinc), silver NPs have offered novel designs of NPs (1–100 nm) that were used in various pest management programs [4,5]. Recently, silver sulfide NPs (Ag2SNPs) synthesized from green plants and microbial origin have gained an important place in nanofabrication with a wide range of applications, including anticancer, anti-inflammatory, anthelmintic and wastewater treatment, and antimicrobial properties [6,7].

The phylum Actinomycetota is primarily composed of gram-positive bacteria with a high nitrogenous base content. By acting as a reducing agent, the metabolites secreted by these bacteria can promote the fusion of NPs [8]. For instance, AgNPs synthesized by Nocardiopsis sp. MBRC-1 (marine antimicrobial strain) showed potent antimicrobial and cytotoxic properties [9]. Similar results were obtained when Streptomyces xinghaiensis OF1-derived AgNPs were tested against pathogenic bacteria and yeast [10]. Due to their metal nature, AgNPs must be suited for a biological system to reduce their cytotoxic effect and the ways in which they interact and connect with biological cells [11].

The common cutworm and cotton bollworm (Spodoptera litura and H. armigera) are well-known lepidopteran agricultural pests that almost occupy entire agricultural crops due to their polyphagous nature and are responsible for major crop damage [12]. Besides crop pests, mosquitoes, Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus, served as a vector for spreading many deadly diseases worldwide [13]. Since their outbreak as a pest, the persistent use of chemical insecticides to combat these insect pests may lead to the development of resistance against them through various resistance mechanisms [14]. Apart from resistance, chemical insecticide residues may harm the environment, humans, and other non-target organisms [15]. Therefore, alternatives to chemical pesticides for insect pest management must be investigated. Nanotechnology has provided a different strategy for the pest control program to overcome pesticide resistance [16].

Numerous lines of research have demonstrated the antimicrobial characteristics of AgNPs; however, the insecticidal properties of Ag2SNPs produced through biological synthesis have not been studied properly [17,18]. Comparably, various biomedical applications and mosquito larvicidal activities of selenium NPs synthesized from the M10A62 strain [19,20]. Hence, the present study investigated the biosynthesis of Ag2SNPs and its possible application in pest control using the Streptomyces minutiscleroticus actinobacterial strain (M10A62) isolated from a magnesite mine soil sample.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Actinobacterial strain

S. minutiscleroticus M10A62 (GenBank Accession Number: JX905302) actinobacterial strain was isolated from a magnesite mine soil sample from Salem district, Tamil Nadu, India. This strain was isolated on casein starch agar (CSA) medium with the supplement of ampicillin (15 μg·ml−1) and fluconazole (20 μg·ml−1) to inhibit undesirable microorganism development and purified on ISP-2 (International Streptomyces Project 2) medium [21]. The phenotypic characterization was done by TEM analysis to confirm the presence of aerial and substrate mycelium; further, 16s rDNA sequencing was used to confirm the strain of Streptomyces sp. [19].

2.2 Biosynthesis of Ag2SNPs

The Ag2SNPs were synthesized by using a shaking incubator. For 5 days at 250 rpm, the S. minutiscleroticus M10A62 strain was transferred to a 250 ml conical flask filled with 100 ml of yeast and malt extract broth and placed in a shaking incubator. Further, the biomass and cell fluids were separated by centrifugation, which ran for 30 min at 4˚C and 6,000 rpm. 5 g of fresh, wet biomass was added to a 100 ml aqueous solution containing 1 mM AgNO3 (silver nitrate) and Na2S⸱9H2O (sodium sulfide nonahydrate), rinsed three times with sterile distilled water, and mixed (HiMedia). After 48 h of consistent shaking at 250 rpm, at room temperature, the entire mixture was centrifuged for 30 min at 10,000 rpm to obtain a cell extract that was used in subsequent research.

2.3 Characterization of Ag2SNPs

2.3.1 UV–visible spectral analysis

The visual color shift of the media from white to black served as a preliminary confirmation of the biosynthesis of Ag2SNPs [28]. Afterwards, the mixture was centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 15 min to separate the nanoparticles from the liquid. The reduction of nanoparticles was observed in a UV–vis spectrophotometer (Cyber Lab dual-beam spectrophotometer) at the wavelength of 200–700 nm by using 2 ml of aqueous solution at 1 nm resolution [22].

2.3.2 Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) analysis

FT-IR was used to examine the nanoparticles containing allied functional groups (free amines, amides, or cysteine residues of protein) using the FT-IR model EXI. The lowest amount of dried powder sample was ground with 100 mg of potassium bromide of FT-IR quality before being formed into a pellet [23]. The compressed sample was held in the sample holder, and infrared spectra with a resolution of 4 cm−1 in the wavelength range of 400–4,000 cm−1 were collected. By contrasting functional peaks with already-existing peaks, the resulting nanoparticle spectrum was identified.

2.3.3 Atomic force microscopic (AFM) analysis

AFM analysis was carried out to monitor surface images of Ag2SNPs by using Nanosurf-AFM. The samples were prepared by mixing nanoparticles with methanol, and a drop of the mixture was coated in a silicon slide and further evaporated to form a thin film. Finally, a thin film (1 cm × 1 cm) containing the sample was observed using AFM [24].

2.3.4 X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis

An XRD (SHIMADZU XRD 6000) was used to analyze the purity and phase formation in Ag2SNPs by using a 40 kV voltage and 30 mA current. The nanoparticle samples were centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 20 min to ensure purity and re-dispersed in 10 ml of sterile deionized water. Then, the samples were freeze-dried, powdered, and used for structural characterization. The lucid nature of the nanoparticles was identified by comparing the XRD peaks with the Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards (JCPDS) pattern [25].

2.3.5 Transmission electron microscopic (TEM) analysis

The morphological structure of the Ag2SNPs was determined by the TEM model (HITACHI H-600). The silver sulfide sample was prepared by mixing nanoparticles with methanol and ground well. Further, the samples were dehydrated with acetone and infiltrated. Then, the drop of the sample solution was coated in a silicon slide and evaporated to form a thin film, and 1% osmium tetraoxide was poured over the slide, which acts as a post-fixative agent. By using TEM analysis at 80 kV, the size and form of the nanoparticles in the carbon-coated copper grid were determined [26].

2.3.6 AFM analysis

AFM was used to analyze the size of the synthesized Ag2SNPs with selected area electron diffraction [27]. The samples were diluted in distilled water in a 1:9 ratio for AFM analysis. Then, two drops of the dilution were placed in a sample holder and allowed to air dry.

2.3.7 Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis

To determine the nanoparticle size dispersion, DLS was used. By injecting 2 ml of deionized water into the interior flow cell, the remaining particles that were present in the flow cell were removed. In order to determine a baseline scattering intensity, the light scattering measurements were logged for 2 min. A 1 ml syringe with 0.8 ml of nanoparticle solution was streaming into the flow cell at the end of the baseline intensity setup. To investigate the scattering intensity within the detector limit, only 0.7 ml of the 0.8 ml solution was pumped into the flow cell. The flow rate was halted once the 0.7 ml of solution had entered the flow cell, and the light scattering measurement was taken for 25 min. Subsequently, sterilized deionized water was used to flush out the nanoparticle’s solution [28].

2.3.8 EDAX analysis

The percentage of the elemental composition of the nanoparticles was determined by EDAX studies by using Bruker AXS Inc., USA, Quantax-200 micro-analysis system coupled with TEM [29].

2.4 Insecticidal activity of Ag2SNPs on lepidopteran insects

The toxicity of biosynthesized Ag2SNPs was investigated on two important lepidopteran insects using the leaf dip method [30]. The H. armigera and S. litura (Accession no. NBAII-MP-NOC-01) egg mass was purchased from the National Bureau of Agricultural Insect Resources live insect repository (NBAIR), Bangalore, Karnataka, India. The first instar larvae hatched from each culture were maintained in the laboratory on castor leaves (25 ± 1°C, 70 ± 5% RH, and 12:12 h light: dark) without exposure to any insecticide. Fresh, clean, and young castor leaves were soaked in different concentrations of Ag2SNPs (10, 50, 100, 150, and 200 µg·ml−1) for 20 s and left for a few minutes until getting dry; the control received water only. Approximately 25 early third instar H. armigera and S. litura larvae were released in Ag2SNPs dipped and control leaves. Three replications were maintained for each concentration. After 14, 24, 36, 40, and 48 h of treatment, the larval mortality was determined.

2.5 Insecticidal activity of Ag2SNPs on dipterans insects

The insecticidal activity of Ag2SNPs was evaluated on two dipterans insects as per the method of Muthusamy and Shivakumar [31]. The Ae. aegypti and Cx. quinquefasciatus were collected in the form of egg mass and egg raft from the Institute of Vector Control and Zoonoses (IVCZ, Hosur, Tamil Nadu, India). The eggs were brought into the laboratory and cultured under controlled conditions (25 ± 1°C, 70 ± 5% RH, and 12:12 h light: dark) on fresh tap water containing trays covered with mosquito net cloth. During the culture period, dog biscuits were provided as larval food. The newly hatched early third instar mosquito larvae were used for the insecticidal efficacy of Ag2SNPs. Serial concentrations of Ag2SNPs were prepared (as mentioned above) in a 250 ml paper cup containing distilled water. There were three replicates for each dose, and 25 larval (uniform-sized) were released in each paper cups; the control received only water. The larval mortality was assessed at 7, 14, 24, 36, 40, and 48 h of post treatment.

3 Results and discussion

The Actinobacteria are a significant bacterial group that is present in both terrestrial and aquatic settings. It has economic importance as a source of many antibiotics and the decomposing ability of many organic matters [32]. The present study revealed that five bacterial isolates with vegetative mycelium development on selective media were isolated. However, based on the quantitative analysis of metal-producing ability, actinomycete isolate S. minutiscleroticus M10A62 strain was used in this research to produce Ag2SNPs in the fight against target insect pests.

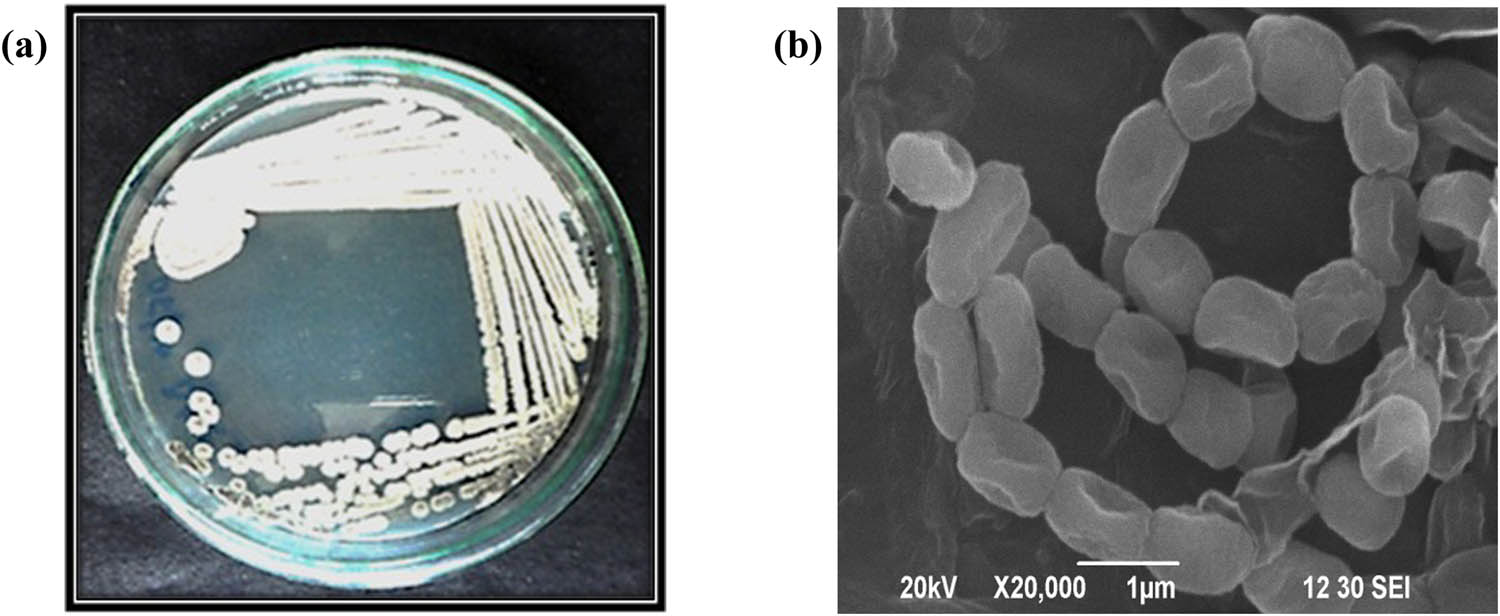

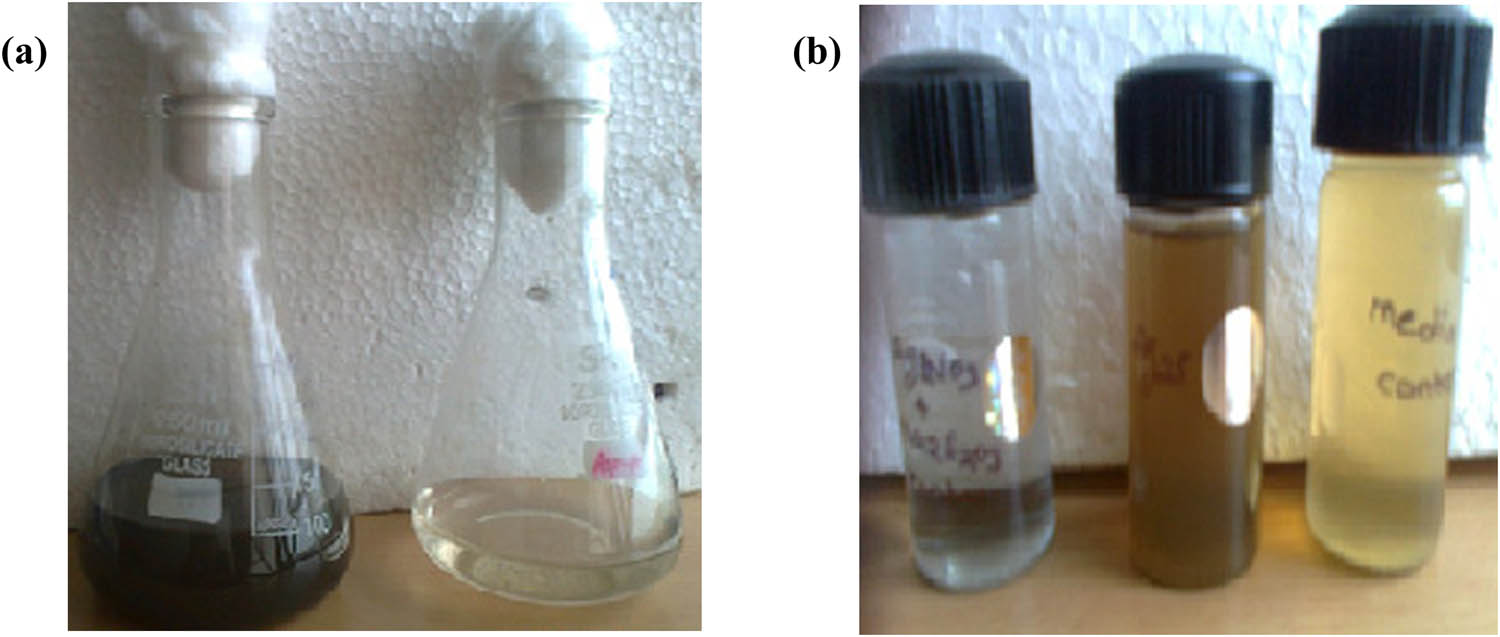

Figure 1 illustrates the morphological characteristics of the M10A62 strain, and the texture and color of white aerial mycelium are depicted in Figure 1a. The SEM image (Figure 1b) shows the morphology of spores with recti flexible (RF) arrangement of smooth surface. After being identified as a potential source of AgNPs, physicochemical characteristics such as temperature, pH, and various reaction combinations were optimized [33]. The conversion of AgNO3 and Na2S⸱9H2O into Ag2SNPs was validated during M10A62 strain incubation by color changes to a brown, yellow, indicating the production of Ag2SNPs (Figure 2a and b), is well in accord with the reports of Ramya et al. [20].

Morphological characteristics of S. minutiscleroticus M10A62 (a); (b) SEM analysis of strain M10A62.

Production of Ag2SNPs by M10A62 strain (a and b).

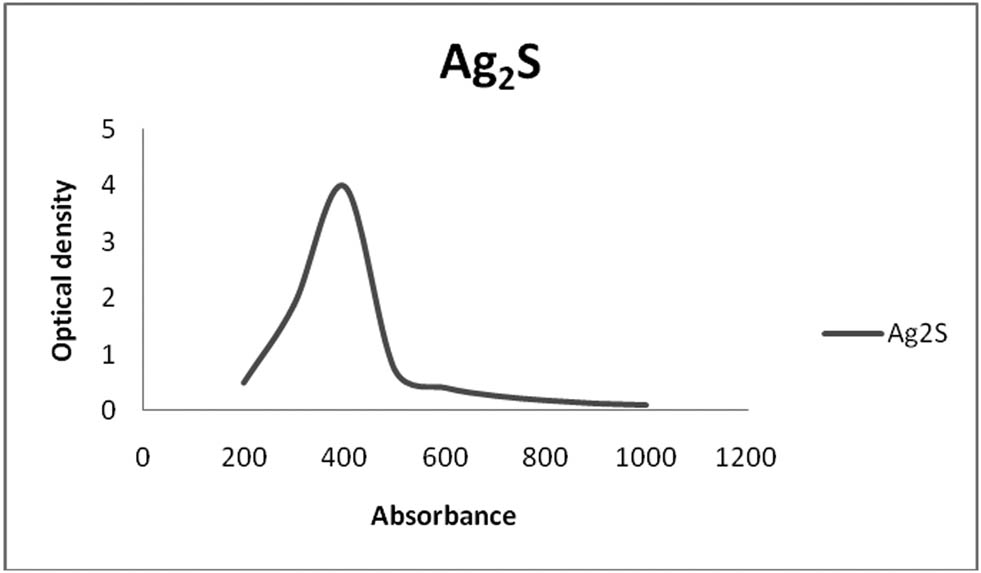

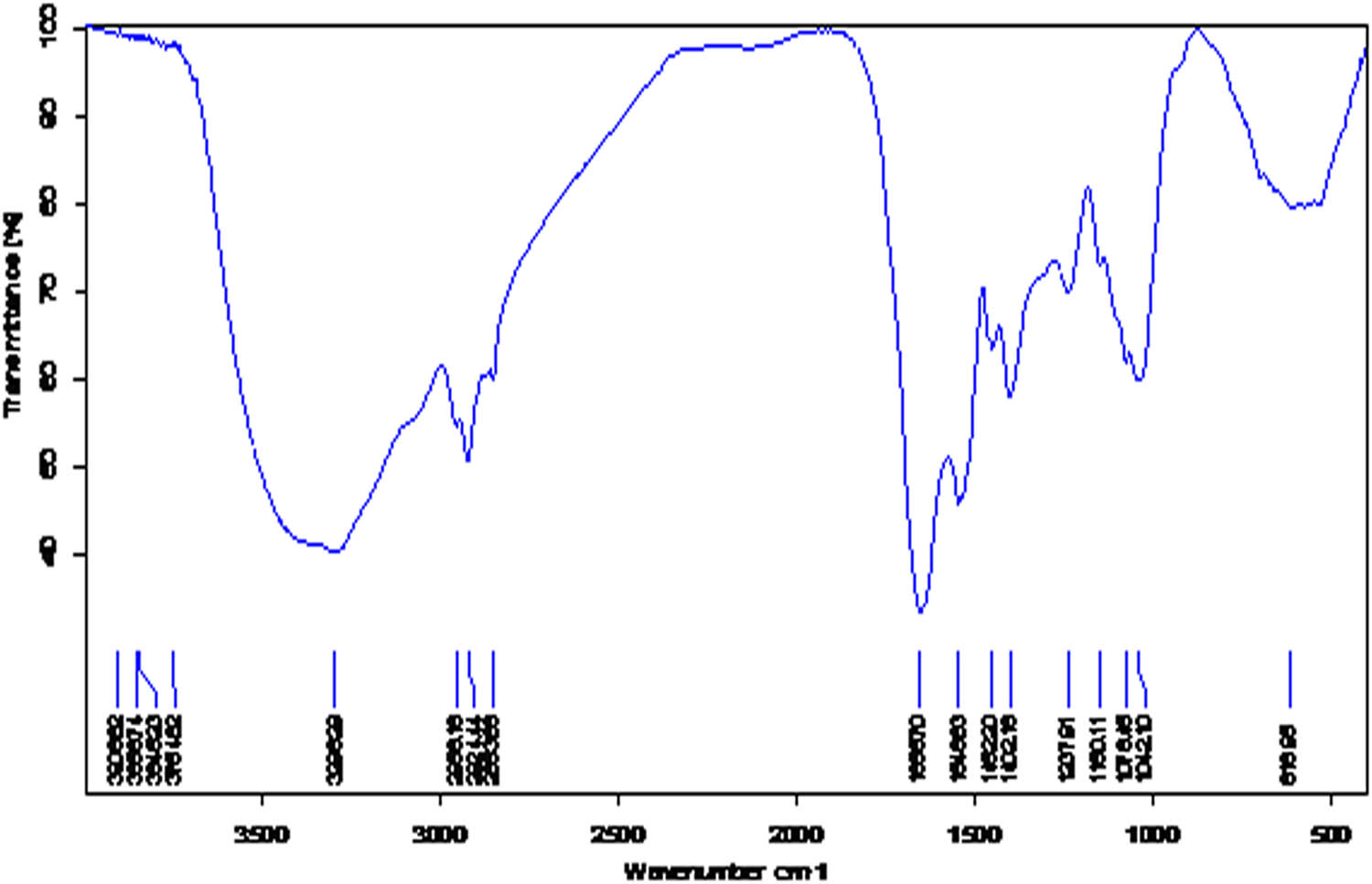

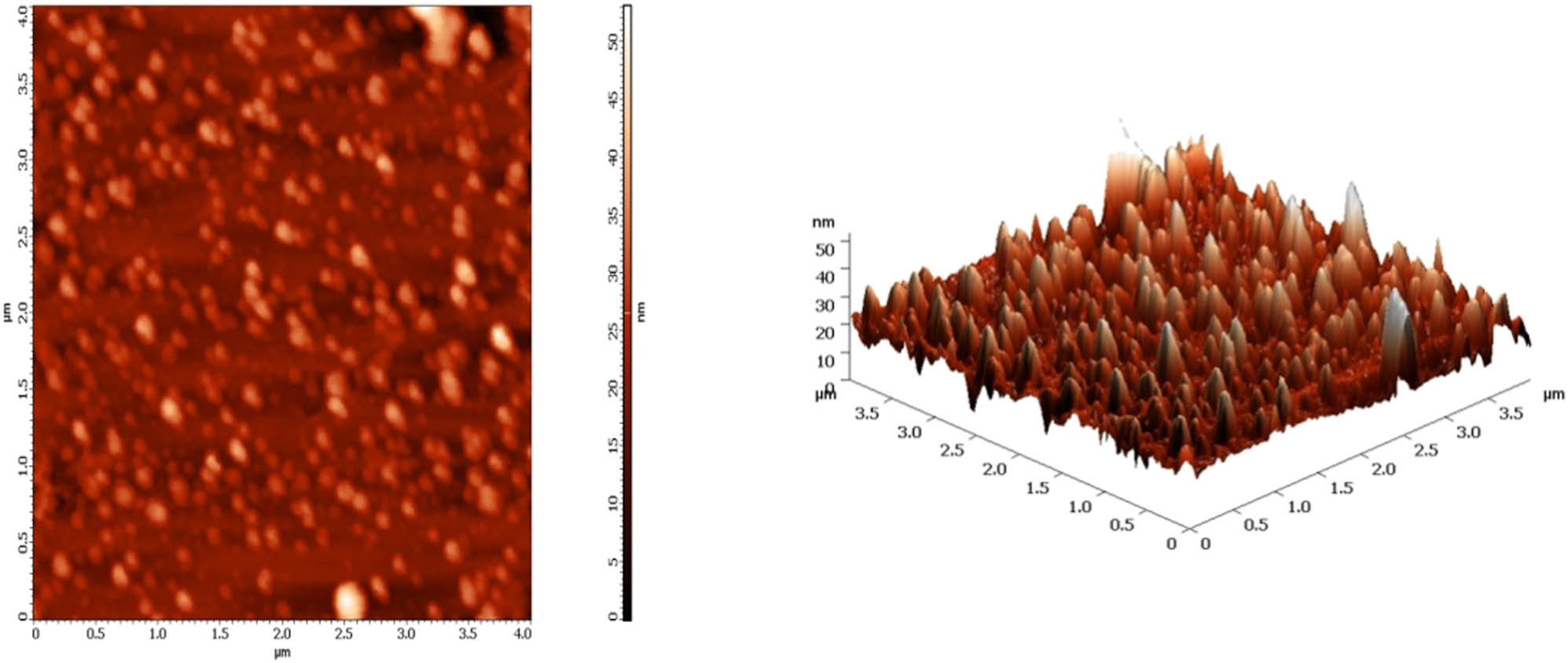

The UV–vis spectrum data revealed the confirmation of Ag2SNP production, and the surface plasma resonance (SPR) phenomenon was responsible for the color shift [34]. The absorption maxima of synthesized Ag2SNPs were obtained at 355 nm (Figure 3). The FT-IR measurement was used primarily to identify the possible biomolecules that are acting as reducing agents in Ag2SNP synthesis by actinobacterial culture filtrate (Figure 4). The FT-IR spectra of Ag2SNPs showed various bands at different wave numbers with respective functional groups (Table 1). The observation for Ag2SNPs indicates that the protein binds to nanoparticles by means of free amines, amides or cysteine residues of protein bind to the negatively charged groups of enzymes present in the cell wall of actinobacterial mycelium through the electrostatic interaction [35,20]. Further, AFM analysis shows that the synthesized Ag2SNPs were mostly spherical in shape with an average size ranging from 0.5 to 5 µm, respectively (Figure 5).

UV–visible spectra of S. minutiscleroticus derived Ag2SNPs.

FT-IR spectrum of S. minutiscleroticus derived Ag2SNPs.

FT-IR peaks and their functional groups for Ag2SNPs

| S. No | Peaks (cm−1) | Functional groups |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3,777 | Strong sharp O–H stretching |

| 2 | 3,471 | Amide I |

| 3 | 2,926 | C–H stretching |

| 4 | 2,139 | Alkyene |

| 5 | 1,776 | C═O stretching |

| 6 | 1,650 | Amide II |

| 7 | 1,597 | Amide conjugated |

| 8 | 1,356 | Amide III |

| 9 | 1,128 | C–N stretching |

| 10 | 1,019 | C–O stretching |

| 11 | 647 | Residues of

|

AFM images of S. minutiscleroticus derived Ag2SNPs.

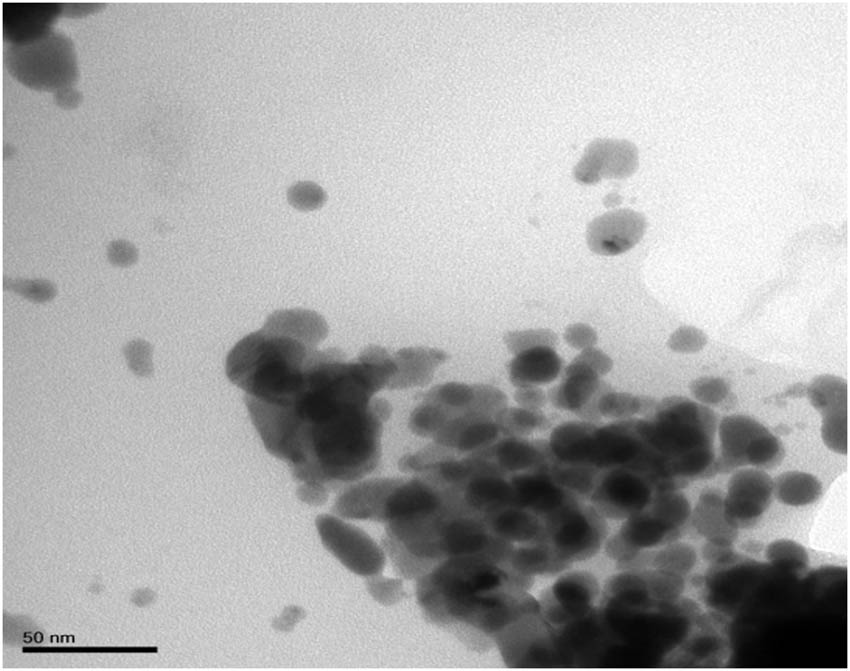

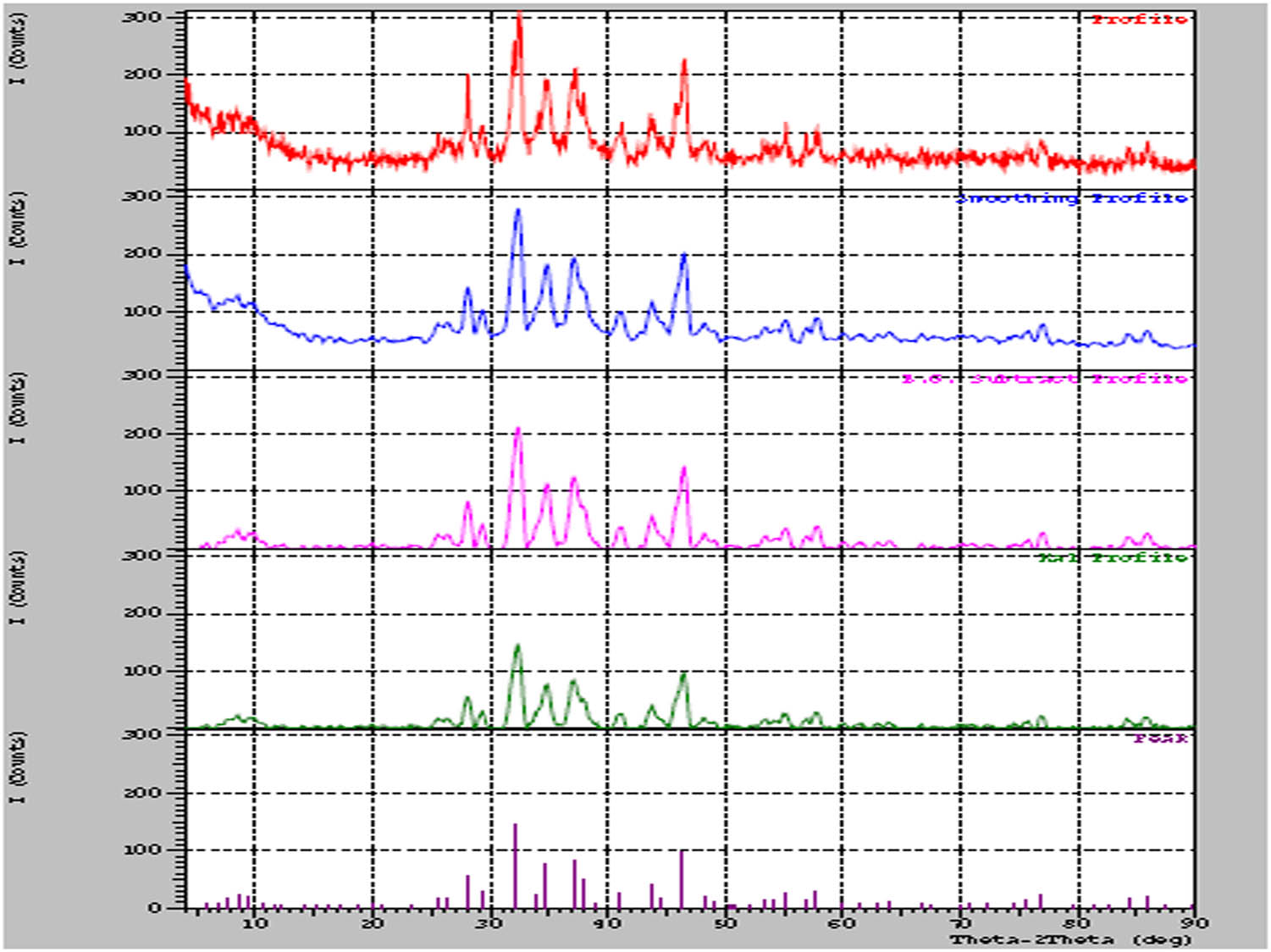

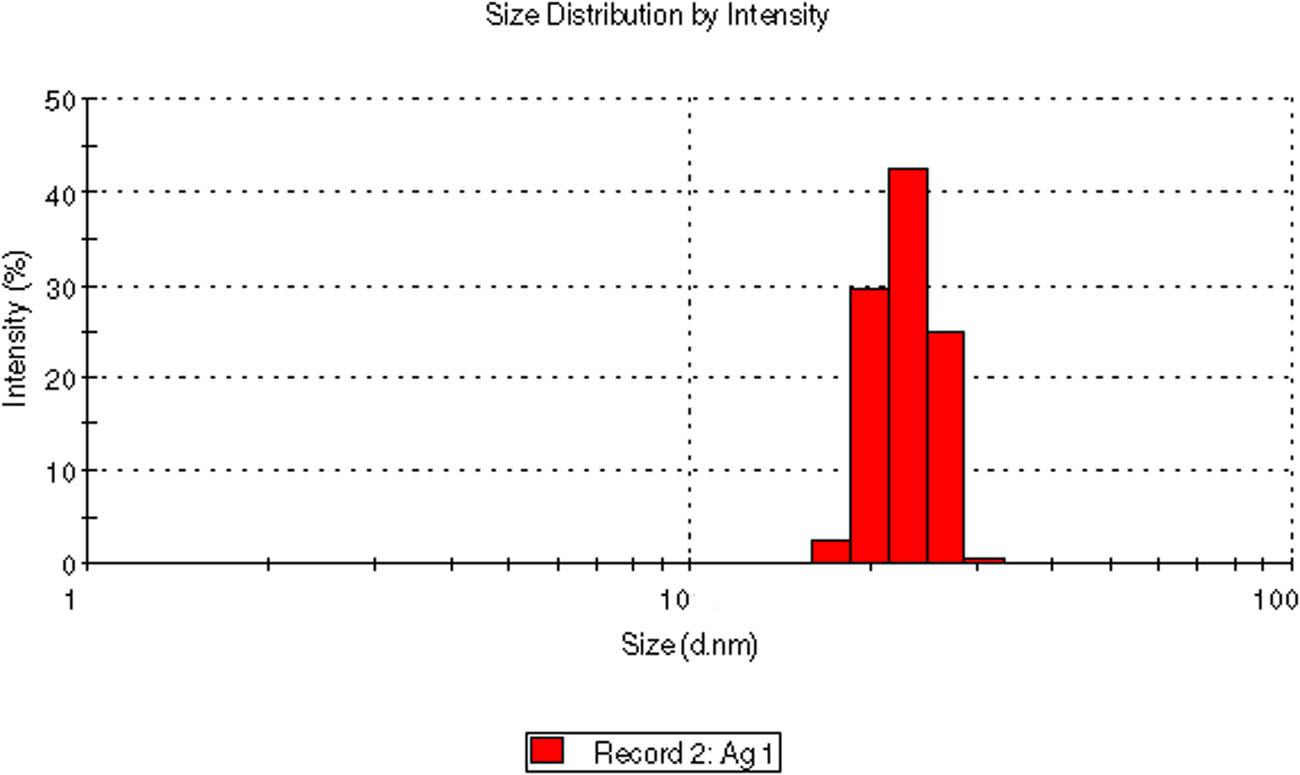

The TEM pictures revealed that the actinobacterial strain M10A62 produced well-disseminated nanoparticles that were attached to capping protein molecules. The morphology and size of the Ag2SNPs were 50–85 nm in size with spherical in shape (Figure 6). TEM analysis results were well matched with Ramya et al. [19], who studied the biological properties of actinobacterial-synthesized selenium nanoparticles. Figure 7 shows the XRD pattern of the Ag2SNPs exhibited strong reflections at 2θ values of 46.25°, 44.12°, 32.23°, and 37.10° corresponding to the planes −111, 111, 112, and 120 (JCPDS card No. 14-0072). Comparably, similar results from pomegranate peel extract and Nicotiana tabacum leaf extract derived XRD pattern were documented [36,37]. The dynamic light dispersion experiment revealed that Ag2SNP particle size was about 10 nm (Figure 8). Figure 9 illustrates that the EDAX analysis of sulfide nanoparticles exhibited a strong signal at 3 keV due to SPR [10,38].

TEM image of S. minutiscleroticus derived Ag2SNPs.

XRD pattern of S. minutiscleroticus derived Ag2SNPs.

DLS of S. minutiscleroticus derived Ag2SNPs.

EDAX spectrum of S. minutiscleroticus derived Ag2SNPs.

Numerous researchers have studied the toxic effect of nanoparticles on pathogenic bacteria and other pathogens of animals [39,40,41]. There have been relatively few investigations on the biocidal effect of biosynthesized nanoparticles [42,43]. However, no reports were evidenced in Ag2SNPs against insects as insecticidal compounds. The biosynthesized Ag2SNPs from the M10A62 strain were shown to have a high mortality rate on S. litura and H. armigera at 150 and 200 g·ml−1 after 40 and 48 h post-treatment (Figure 10a and b). Followed by lepidopteran, Ag2SNPs showed 100% mortality at 150 and 200 µg·ml−1 on Ae. aegypti after 40 and 48 h post-treatment (Figure 10c), whereas in Cx. quinquefasciatus Ag2SNPs produced 100% mortality at 100, 150, and 200 µg·ml−1 after 36, 40, and 48 h treatment (Figure 10d). Similarly, in support of our research, Jafir et al. [16] found that the silver nanoparticles from Ocimum basilicum had effective insecticidal activity against S. litura at a dose of 1,500 mg·l−1. Further, the Annona glabra-derived NPs displayed potent larvicidal activity against the dengue vector Ae. aegypti and Aedes albopictus [44]. The essential oil-wrapped AgNPs showed good toxicity against the larvae and pupae of Ae. albopictus [45]. Cassia hirsute-derived AgNPs showed LC50 4.43 ppm against Cx. quinquefasciatus [46]. Consequently, the results of this work bring up a new application for Ag2SNPs from actinobacterial strain M10A62 and can be used as an alternative technique for pest management.

Insecticidal activity of Ag2SNPs at different time intervals. (a) Insecticidal activity against S. litura. (b) H. armigera. (c) Ae. aegypti. (d) Cx. quinquefasciatus; Mortality (%) represents mean of three replicates, bar indicates standard deviation (SD) of the mean.

4 Conclusion

In this research, an eco-friendly and target-specific stable Ag2SNPs were fabricated from actinobacterial strain M10A62. The synthesized nanoparticles were confirmed by various bio-physical techniques, and the obtained nanoparticles were mostly spherical in shape with an average size ranging from 50 to 85 nm. Based on the results of this research, the Ag2SNPs had significant toxicity on both crop and human pests. Overall, the actinobacterial-derived nanoparticles could be used as alternative insecticides in pest management programs since they are more affordable and safer. The process of biogenic synthesis may be optimized in the future, and field applications may be developed.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Sánchez-López E, Gomes D, Esteruelas G, Bonilla L, Lopez-Machado AL, Galindo R, et al. Metal-based nanoparticles as antimicrobial agents: an overview. Nanomaterials. 2020;10(2):292.10.3390/nano10020292Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Subramaniam S, Kumarasamy S, Narayanan M, Ranganathan M, Rathinavel T, Chinnathambi A, et al. Spectral and structure characterization of Ferula assafoetida fabricated silver nanoparticles and evaluation of its cytotoxic, and photocatalytic competence. Environ Res. 2022;204:111987.10.1016/j.envres.2021.111987Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Ali SS, Moawad MS, Hussein MA, Azab M, Abdelkarim EA, Badr A, et al. Efficacy of metal oxide nanoparticles as novel antimicrobial agents against multi-drug and multi-virulent Staphylococcus aureus isolates from retail raw chicken meat and giblets. Int J Food Microbiol. 2021;344:109116.10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2021.109116Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Ortigosa MS, Valenstein JS, Lin VSY, Trewyn BG, Wang K. Gold functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticle mediated protein and DNA co delivery to plant cells via the biolistic method. Adv Funct Mater. 2012;22:3576–82.10.1002/adfm.201200359Search in Google Scholar

[5] Benelli G. Mode of action of nanoparticles against insects. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;25:12329–41.10.1007/s11356-018-1850-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Kim B, Park CS, Murayama M, Hochella MF. Discovery and characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles in final sewage sludge products. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44(19):7509–14.10.1021/es101565jSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Habeeb Rahuman HB, Dhandapani R, Narayanan S, Palanivel V, Paramasivam R, Subbarayalu R, et al. Medicinal plants mediated the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their biomedical applications. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2022;16(4):115–44.10.1049/nbt2.12078Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Manimaran M, Kannabiran K. Actinomycetes-mediated biogenic synthesis of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles: progress and challenges. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2017;64:401–8.10.1111/lam.12730Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Manivasagan P, Venkatesan J, Senthikumar K, Sivakumar K, Kim SK. Biosynthesis, antimicrobial and cytotoxic effect of silver nanoparticles using a novel Nocardiopsis sp. MBRC-1. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:287638.10.1155/2013/287638Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Wypij M, Czarnecka J, Swiecimska M, Dahm H, Rai M, Golinska P. Synthesis, characterization and evaluation of antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of biogenic silver nanoparticles synthesized from Streptomyces xinghaiensis OF1 strain. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;34:1–13.10.1007/s11274-017-2406-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Liao C, Li Y, Tjong SC. Bactericidal and cytotoxic properties of silver nanoparticles. Inter J Mol Sci. 2019;20:449.10.3390/ijms20020449Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Zhang Z, Gao B, Qu C, Gong J, Li W, Luo C, et al. Resistance monitoring for six insecticides in vegetable field-collected populations of Spodoptera litura from China. Horticulturae. 2022;8(3):255.10.3390/horticulturae8030255Search in Google Scholar

[13] Muthusamy R, Shivakumar MS. Involvement of metabolic resistance and F1534C kdr mutation in the pyrethroid resistance mechanisms of Aedes aegypti in India. Acta Trop. 2015;148:137–41.10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.04.026Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Narayanan M, Ranganathan M, Subramanian SM, Kumarasamy S, Kandasamy S. Toxicity of cypermethrin and enzyme inhibitor synergists in red hairy caterpillar Amsacta albistriga (Lepidoptera: Arctiidae). J Basic Appl Zool. 2020;81:45.10.1186/s41936-020-00185-9Search in Google Scholar

[15] Narayanan M, Kumarasamy S, Ranganathan M, Kandasamy S, Kandasamy G, Gnanavel G. Enzyme and metabolites attained in degradation of chemical pesticides ß Cypermethrin by Bacillus cereus. Mater Today. 2020;33(7):3640–5.10.1016/j.matpr.2020.05.722Search in Google Scholar

[16] Jafir M, Ahmad JN, Arif MJ, Ali S, Ahmad SJN. Characterization of Ocimum basilicum synthesized silver nanoparticles and its relative toxicity to some insecticides against tobacco cutworm. Spodoptera litura Feb (Lepidoptera; Noctuidae) Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;218:112278.10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112278Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Pang M, Hu J, Zeng HC. Synthesis, morphological control, and antibacterial properties of hollow/solid Ag2S/Ag heterodimers. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:10771–85.10.1021/ja102105qSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Wang L, Hu C, Shao L. The antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles: present situation and prospects for the future. Int J Nanomed. 2017;12:1227–49.10.2147/IJN.S121956Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Ramya S, Shanmugasundaram T, Balagurunathan R. Biomedical potential of actinobacterially synthesized selenium nanoparticles with special reference to anti-biofilm, anti-oxidant, wound healing, cytotoxic and anti-viral activities. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2015;32:30–9.10.1016/j.jtemb.2015.05.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Ramya S, Shanmugasundaram T, Balagurunathan R. Actinobacterial enzyme mediated synthesis of selenium nanoparticles for antibacterial, mosquito larvicidal and anthelminthic applications. Part Sci Technol. 2020;38(1):63–72.10.1080/02726351.2018.1508098Search in Google Scholar

[21] El Karkouri A, Assou SA, El Hassouni M. Isolation and screening of actinomycetes producing antimicrobial substances from an extreme Moroccan biotope. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;33:329.10.11604/pamj.2019.33.329.19018Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Vahabi K, Mansoori GA, Karimi S. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by fungus Trichoderma reesei (a route for large-scale production of AgNPs). Sciences J. 2012;1(1):65–79.10.5640/insc.010165Search in Google Scholar

[23] Khalil MA, El-Shanshoury AERR, Alghamdi MA, Alsalmi FA, Mohamed SF, Sun J, et al. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by marine actinobacterium Nocardiopsis dassonvillei and exploring their therapeutic potentials. Front Microbiol. 2022;3(12):705673.10.3389/fmicb.2021.705673Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Christensen L, Vivekanandhan S, Misra M, Mohanty AK. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Murraya koenigii (curry leaf): an investigation on the effect of broth concentration in reduction mechanism and particle size. Adv Mater Lett. 2011;2:429–34.10.5185/amlett.2011.4256Search in Google Scholar

[25] Mohanty S, Mishra S, Jena P, Jacob B, Sarkar B, Sonawane A. An investigation on the antibacterial, cytotoxic, and antibiofilm efficacy of starch-stabilized silver nanoparticles. Nanomed Nanotechnol Biol Med. 2012;8(6):916–24.10.1016/j.nano.2011.11.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Mukherjee P, Ahmad A, Mandal D, Senapati S, Sainkar SR, Khan MI, et al. Fungus-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their immobilization in the mycelial matrix: a novel biological approach to nanoparticle synthesis. Nano Lett. 2001;1(10):515–9.10.1021/nl0155274Search in Google Scholar

[27] Mohammed Fayaz A, Balaji K, Girilal M, Kalaichelvan PT, Venkatesan R. Mycobased synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their incorporation into sodium alginate films for vegetable and fruit preservation. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57(14):6246–52.10.1021/jf900337hSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Smiechowicz E, Kulpinski P, Niekraszewicz B, Bacciarelli A. Cellulose fibers modified with silver nanoparticles. Cellulose. 2011;18:975–85.10.1007/s10570-011-9544-9Search in Google Scholar

[29] Goel N, Ahmad R, Singh R, Sood S, Khare S. Biologically synthesized silver nanoparticles by Streptomyces sp. EMB24 extracts used against the drug-resistant bacteria. Bioresour Technol Rep. 2021;15:100753.10.1016/j.biteb.2021.100753Search in Google Scholar

[30] Bhattacharyya A, Prasad R, Buhroo AA, Duraisamy P, Yousuf I, Umadevi M, et al. One-pot fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Solanum lycopersicum: an eco-friendly and potent control tool against rose aphid, Macrosiphum rosae. J Nanosci. 2016;2016:4679410.10.1155/2016/4679410Search in Google Scholar

[31] Muthusamy R, Shivakumar MS. Susceptibility status of Aedes aegypti (L.) (Diptera: Culicidae) to temephos from three districts of Tamil Nadu, India. J Vector Borne Dis. 2015;52(2):159–65.10.4103/0972-9062.159502Search in Google Scholar

[32] Ganesan P, Reegan AD, David RHA, Gandhi MR, Paulraj MG, Al-Dhabi NA, et al. Antimicrobial activity of some actinomycetes from Western Ghats of Tamil Nadu, India. Alex Med J. 2017;53:101–10.10.1016/j.ajme.2016.03.004Search in Google Scholar

[33] Veerasamy R. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using mangosteen leaf extract and evaluation of their antimicrobial activities. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2011;15:113–20.10.1016/j.jscs.2010.06.004Search in Google Scholar

[34] Awwad AM, Salem NM, Aqarbeh MM, Abdulaziz FM. Green synthesis, characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles and antibacterial activity evaluation. Chem Int. 2000;6(1):42–8.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Seyedeh MG, Sepideh H, Shojaosadati SA. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles by a novel method: comparative study of their properties. Carbohydr Polym. 2012;89:467–72.10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.03.030Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Nazeruddin GM, Prasad SR, Shaikh YI, Ansari J, Sonawane KD, Nayak AK, et al. In-vitro bio-fabrication of multi-applicative silver nanoparticles using Nicotiana tabacum leaf extract. Life Sci Inf Public. 2016;2:6–30.10.1016/j.rinp.2016.02.007Search in Google Scholar

[37] Bharani RA, Namasivayam SKR. Biogenic silver nanoparticles mediated stress on developmental period and gut physiology of major lepidopteran pest Spodoptera litura (Fab.) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). An eco-friendly approach of insect pest control. J Environ Chem Eng. 2027;5:453–67.10.1016/j.jece.2016.12.023Search in Google Scholar

[38] Das A, Mukherjee P, Singla SK, Guturu P, Frost MC, Mukhopadhyay D, et al. Fabrication and characterization of an inorganic gold and silica nanoparticle mediated drug delivery system for nitric oxide. Nanotechnology. 2010;21:305102.10.1088/0957-4484/21/30/305102Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Siddiqi KS, Husen A, Rao RA. A review on biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles and their biocidal properties. J Nanobiotechnol. 2018;16:1–28.10.1186/s12951-018-0334-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Hernández-Díaz JA, Garza-García JJ, León-Morales JM, Zamudio-Ojeda A, Arratia-Quijada J, Velázquez-Juárez G, et al. Antibacterial activity of biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using extracts of Calendula officinalis against potentially clinical bacterial strains. Molecules. 2021;26(19):5929.10.3390/molecules26195929Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Abdelsattar AS, Hakim TA, Rezk N, Farouk WM, Hassan YY, Gouda SM, et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ocimum basilicum L. and Hibiscus sabdariffa L. extracts and their antibacterial activity in combination with phage ZCSE6 and sensing properties. J Inorg Organomet Polym. 2022;32:1951–65.10.1007/s10904-022-02234-ySearch in Google Scholar

[42] Ramkumar G, Asokan R, Ramya S, Gayathri G. Characterization of Trigonella foenum-graecum derived iron nanoparticles and its potential pesticidal activity against Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera). J Clust Sci. 2021;32(1):1–6.10.1007/s10876-020-01867-8Search in Google Scholar

[43] Ramkumar G, Shivakumar MS, Alshehri MA, Panneerselvam C, Sayed SM. Larvicidal potential of Cipadessa baccifera leaf extract-synthesized zinc nanoparticles against three major mosquito vectors. Green Process Synth. 2022;11(1):757–65.10.1515/gps-2022-0071Search in Google Scholar

[44] Amarasinghe LD, Wickramarachchi PASR, Aberathna AAAU, Sithara WS, De Silva CR. Comparative study on larvicidal activity of green synthesized silver nanoparticles and Annona glabra (Annonaceae) aqueous extract to control Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae). Heliyon. 2020;6(6):e04322. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04322.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Ga’al H, Fouad H, Mao G, Tian J, Jianchu M. Larvicidal and pupicidal evaluation of silver nanoparticles synthesized using Aquilaria sinensis and Pogostemon cablin essential oils against dengue and zika viruses vector Aedes albopictus mosquito and its histopathological analysis. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2018;46(6):1171–9.10.1080/21691401.2017.1365723Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Adesuji ET, Oluwaniyi OO, Adegoke HI, Moodley R, Labulo AH, Bodede OS, et al. Investigation of the larvicidal potential of silver nanoparticles against Culex quinquefasciatus: a case of a ubiquitous weed as a useful bioresource. J Nanomater. 2016:1–11. 10.1155/2016/4363751.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Value-added utilization of coal fly ash and recycled polyvinyl chloride in door or window sub-frame composites

- High removal efficiency of volatile phenol from coking wastewater using coal gasification slag via optimized adsorption and multi-grade batch process

- Evolution of surface morphology and properties of diamond films by hydrogen plasma etching

- Removal efficiency of dibenzofuran using CuZn-zeolitic imidazole frameworks as a catalyst and adsorbent

- Rapid and efficient microwave-assisted extraction of Caesalpinia sappan Linn. heartwood and subsequent synthesis of gold nanoparticles

- The catalytic characteristics of 2-methylnaphthalene acylation with AlCl3 immobilized on Hβ as Lewis acid catalyst

- Biodegradation of synthetic PVP biofilms using natural materials and nanoparticles

- Rutin-loaded selenium nanoparticles modulated the redox status, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways associated with pentylenetetrazole-induced epilepsy in mice

- Optimization of apigenin nanoparticles prepared by planetary ball milling: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Origanum onites leaves: Cytotoxic, apoptotic, and necrotic effects on Capan-1, L929, and Caco-2 cell lines

- Exergy analysis of a conceptual CO2 capture process with an amine-based DES

- Construction of fluorescence system of felodipine–tetracyanovinyl–2,2′-bipyridine complex

- Excellent photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Bi2O3 supported on Zn-MOF nanocomposites under visible light

- Optimization-based control strategy for a large-scale polyhydroxyalkanoates production in a fed-batch bioreactor using a coupled PDE–ODE system

- Effectiveness of pH and amount of Artemia urumiana extract on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of UV-fabricated biogold nanoparticles

- Geranium leaf-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their transcriptomic effects on Candida albicans

- Synthesis, characterization, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities, and docking studies of 3,5-disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones

- Synthesis and stability of phospholipid-encapsulated nano-selenium

- Putative anti-proliferative effect of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) seed and its nano-formulation

- Enrichment of low-grade phosphorites by the selective leaching method

- Electrochemical analysis of the dissolution of gold in a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate system

- Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites

- Evaluation of nano-selenium biofortification characteristics of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)

- Quality of oil extracted by cold press from Nigella sativa seeds incorporated with rosemary extracts and pretreated by microwaves

- Heteropolyacid-loaded MOF-derived mesoporous zirconia catalyst for chemical degradation of rhodamine B

- Recovery of critical metals from carbonatite-type mineral wastes: Geochemical modeling investigation of (bio)hydrometallurgical leaching of REEs

- Photocatalytic properties of ZnFe-mixed oxides synthesized via a simple route for water remediation

- Attenuation of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by naringin nanoparticles in a rat model

- Novel in situ synthesis of quaternary core–shell metallic sulfide nanocomposites for degradation of organic dyes and hydrogen production

- Microfluidic steam-based synthesis of luminescent carbon quantum dots as sensing probes for nitrite detection

- Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder

- Preparation of Zr-MOFs for the adsorption of doxycycline hydrochloride from wastewater

- Green nanoarchitectonics of the silver nanocrystal potential for treating malaria and their cytotoxic effects on the kidney Vero cell line

- Carbon emissions analysis of producing modified asphalt with natural asphalt

- An efficient and green synthesis of 2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones via t-BuONa-mediated oxidative condensation of 2-aminobenzamides and benzyl alcohols under solvent- and transition metal-free conditions

- Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with mesosulfuron methyl and mesosulfuron methyl + florasulam + MCPA isooctyl to manage weeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- Synergism between lignite and high-sulfur petroleum coke in CO2 gasification

- Facile aqueous synthesis of ZnCuInS/ZnS–ZnS QDs with enhanced photoluminescence lifetime for selective detection of Cu(ii) ions

- Rapid synthesis of copper nanoparticles using Nepeta cataria leaves: An eco-friendly management of disease-causing vectors and bacterial pathogens

- Study on the photoelectrocatalytic activity of reduced TiO2 nanotube films for removal of methyl orange

- Development of a fuzzy logic model for the prediction of spark-ignition engine performance and emission for gasoline–ethanol blends

- Micro-impact-induced mechano-chemical synthesis of organic precursors from FeC/FeN and carbonates/nitrates in water and its extension to nucleobases

- Green synthesis of strontium-doped tin dioxide (SrSnO2) nanoparticles using the Mahonia bealei leaf extract and evaluation of their anticancer and antimicrobial activities

- A study on the larvicidal and adulticidal potential of Cladostepus spongiosus macroalgae and green-fabricated silver nanoparticles against mosquito vectors

- Catalysts based on nickel salt heteropolytungstates for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide

- Powerful antibacterial nanocomposites from Corallina officinalis-mediated nanometals and chitosan nanoparticles against fish-borne pathogens

- Removal behavior of Zn and alkalis from blast furnace dust in pre-reduction sinter process

- Environmentally friendly synthesis and computational studies of novel class of acridinedione integrated spirothiopyrrolizidines/indolizidines

- The mechanisms of inhibition and lubrication of clean fracturing flowback fluids in water-based drilling fluids

- Adsorption/desorption performance of cellulose membrane for Pb(ii)

- A one-pot, multicomponent tandem synthesis of fused polycyclic pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolinone/pyrrolizino[2,3-c]quinolinone hybrid heterocycles via environmentally benign solid state melt reaction

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using durian rind extract and optical characteristics of surface plasmon resonance-based optical sensor for the detection of hydrogen peroxide

- Electrochemical analysis of copper-EDTA-ammonia-gold thiosulfate dissolution system

- Characterization of bio-oil production by microwave pyrolysis from cashew nut shells and Cassia fistula pods

- Green synthesis methods and characterization of bacterial cellulose/silver nanoparticle composites

- Photocatalytic research performance of zinc oxide/graphite phase carbon nitride catalyst and its application in environment

- Effect of phytogenic iron nanoparticles on the bio-fortification of wheat varieties

- In vitro anti-cancer and antimicrobial effects of manganese oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the Glycyrrhiza uralensis leaf extract on breast cancer cell lines

- Preparation of Pd/Ce(F)-MCM-48 catalysts and their catalytic performance of n-heptane isomerization

- Green “one-pot” fluorescent bis-indolizine synthesis with whole-cell plant biocatalysis

- Silica-titania mesoporous silicas of MCM-41 type as effective catalysts and photocatalysts for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide by H2O2

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from molted feathers of Pavo cristatus and their antibiofilm and anticancer activities

- Clean preparation of rutile from Ti-containing mixed molten slag by CO2 oxidation

- Synthesis and characterization of Pluronic F-127-coated titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of Atractylodes macrocephala leaf for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties

- Effect of pretreatment with alkali on the anaerobic digestion characteristics of kitchen waste and analysis of microbial diversity

- Ameliorated antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties by Plectranthus vettiveroides root extract-mediated green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles

- Microwave-accelerated pretreatment technique in green extraction of oil and bioactive compounds from camelina seeds: Effectiveness and characterization

- Studies on the extraction performance of phorate by aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in plasma samples

- Investigation of structural properties and antibacterial activity of AgO nanoparticle extract from Solanum nigrum/Mentha leaf extracts by green synthesis method

- Green fabrication of chitosan from marine crustaceans and mushroom waste: Toward sustainable resource utilization

- Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

- The enhanced adsorption properties of phosphorus from aqueous solutions using lanthanum modified synthetic zeolites

- Separation of graphene oxides of different sizes by multi-layer dialysis and anti-friction and lubrication performance

- Visible-light-assisted base-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of highly functionalized cinnolines

- The experimental study on the air oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with Co–Mn–Br system

- Highly efficient removal of tetracycline and methyl violet 2B from aqueous solution using the bimetallic FeZn-ZIFs catalyst

- A thermo-tolerant cellulase enzyme produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M7, an insight into synthesis, optimization, characterization, and bio-polishing activity

- Exploration of ketone derivatives of succinimide for their antidiabetic potential: In vitro and in vivo approaches

- Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis and in silico study of 6-(4-(butylamino)-6-(diethylamino)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxypyridazine derivatives

- A study of the anticancer potential of Pluronic F-127 encapsulated Fe2O3 nanoparticles derived from Berberis vulgaris extract

- Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Consolida orientalis flowers: Identification, catalytic degradation, and biological effect

- Initial assessment of the presence of plastic waste in some coastal mangrove forests in Vietnam

- Adsorption synergy electrocatalytic degradation of phenol by active oxygen-containing species generated in Co-coal based cathode and graphite anode

- Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of the aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum-mediated synthesized novel silver nanoparticles

- Synthesis of a silica matrix with ZnO nanoparticles for the fabrication of a recyclable photodegradation system to eliminate methylene blue dye

- Natural polymer fillers instead of dye and pigments: Pumice and scoria in PDMS fluid and elastomer composites

- Study on the preparation of glycerylphosphorylcholine by transesterification under supported sodium methoxide

- Wireless network handheld terminal-based green ecological sustainable design evaluation system: Improved data communication and reduced packet loss rate

- The optimization of hydrogel strength from cassava starch using oxidized sucrose as a crosslinking agent

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Saccharum officinarum leaf extract for antiviral paint

- Study on the reliability of nano-silver-coated tin solder joints for flip chips

- Environmentally sustainable analytical quality by design aided RP-HPLC method for the estimation of brilliant blue in commercial food samples employing a green-ultrasound-assisted extraction technique

- Anticancer and antimicrobial potential of zinc/sodium alginate/polyethylene glycol/d-pinitol nanocomposites against osteosarcoma MG-63 cells

- Nanoporous carbon@CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a green absorbent for the adsorptive removal of Hg(ii) from aqueous solutions

- Characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles from actinobacterial strain (M10A62) and its toxicity against lepidopteran and dipterans insect species

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Withania somnifera: Investigating antioxidant potential

- Effect of e-waste nanofillers on the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of epoxy-blend sisal woven fiber-reinforced composites

- Magnesium nanohydroxide (2D brucite) as a host matrix for thymol and carvacrol: Synthesis, characterization, and inhibition of foodborne pathogens

- Synergistic inhibitive effect of a hybrid zinc oxide-benzalkonium chloride composite on the corrosion of carbon steel in a sulfuric acidic solution

- Review Articles

- Role and the importance of green approach in biosynthesis of nanopropolis and effectiveness of propolis in the treatment of COVID-19 pandemic

- Gum tragacanth-mediated synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and their applications as a bactericide, catalyst, antioxidant, and peroxidase mimic

- Green-processed nano-biocomposite (ZnO–TiO2): Potential candidates for biomedical applications

- Reaction mechanisms in microwave-assisted lignin depolymerisation in hydrogen-donating solvents

- Recent progress on non-noble metal catalysts for the deoxydehydration of biomass-derived oxygenates

- Rapid Communication

- Phosphorus removal by iron–carbon microelectrolysis: A new way to achieve phosphorus recovery

- Special Issue: Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications (Guest Editors: Arpita Roy and Fernanda Maria Policarpo Tonelli)

- Biomolecules-derived synthesis of nanomaterials for environmental and biological applications

- Nano-encapsulated tanshinone IIA in PLGA-PEG-COOH inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach ripened fruit extract, their characterization, and biological properties

- Green-synthesized nanoparticles and their therapeutic applications: A review

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxicity potential of synthesized silver nanoparticles from the Cassia alata leaf aqueous extract

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Callisia fragrans leaf extract and its anticancer activity against MCF-7, HepG2, KB, LU-1, and MKN-7 cell lines

- Algae-based green AgNPs, AuNPs, and FeNPs as potential nanoremediators

- Green synthesis of Kickxia elatine-induced silver nanoparticles and their role as anti-acetylcholinesterase in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Phytocrystallization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia alata flower extract for effective control of fungal skin pathogens

- Antibacterial wound dressing with hydrogel from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol from the red cabbage extract loaded with silver nanoparticles

- Leveraging of mycogenic copper oxide nanostructures for disease management of Alternaria blight of Brassica juncea

- Nanoscale molecular reactions in microbiological medicines in modern medical applications

- Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/β-cyclodextrin/nicotinic acid nanocomposite and its biological and environmental application

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana Zucc. plant-derived Taxol: Novel utilization as anticancer, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antiurolithic potential

- Recyclability and catalytic characteristics of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from bougainvillea plant flower extract for biomedical application

- Phytofabrication, characterization, and evaluation of novel bioinspired selenium–iron (Se–Fe) nanocomposites using Allium sativum extract for bio-potential applications

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of nanoparticles of clodinofop propargyl and fenoxaprop-P-ethyl on weed control, growth, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)”