Abstract

A new selective cobalt acetate tetrahydrate or cerium nitrate hexahydrate mediated cleavage of the C–N bond of a benzoyl isothiocyanate derivative to give (carbamoylamino)methanethioamide is presented. The cleavage of the C–N could not be achieved in the absence of thione. The novel silver-mediated conversion of a thione to the carbonyl was achieved on 1-((benzamido)formyl)urea and replicated on (carbamoylamino)methanethioamide to give the deaminolyzed bisurea (dicarbamolyamine). The compounds were characterized by IR, NMR, microanalysis and GC–MS. The single crystal X–ray diffraction studies of the crystal structures of compounds I, II, III and V is discussed.

Graphical Abstract

1 Introduction

Benzoyl isothiocyanates have been reported extensively [1,2], as was their transformation to other classes of compounds [3,4]. Some transformations of benzoyl isothiocyanates and their analogs allow the simple access to certain compounds [5,6,7,8,9]. The isothiocyanates typically have an electrophillic carbon of the thiocyanate moiety which can be attacked by nucleophiles such as nitrogen and oxygen atoms. A reaction with amines typically leads to thiourea derivatives [10]. Metal-catalyzed reactions have been a subject of much interest for many decades and new metal catalysts are currently being invented.

Ackermann et al. [11] have reported a method for the activation and cleavage of a C–H in the synthesis of biaryls using palladium and ruthenium catalysts. The method has been extensively applied in the synthesis of some bioactive compounds.

Cobalt has been used to catalyze the cross-dehydrogenative coupling of benzoxazoles and ethers [12].

Cyclopentanone-2-carboxylates have been converted to (δ-lactones by cerium catalysis with α-arylvinylacetate [13]. The synthesis of a molecular cobalt complex that generates super stoichiometric yields of NH3via the direct reduction of N2 with protons and electrons has been reported [14]. The cobalt(II) diacetonitrilo has been used to catalyze the activation of weak C–H bonds by either iodosobenzene or m-chloroperbenzoic acid [15]. Another impactful bond activation metal-catalyzed reaction is the ruthenium-catalyzed bond-shifting methathesis reactions by Grubbs [16,17]. The cleavage of C–N bonds has been reported to be carried out using transition metals [18]. Carbon–carbon bond formation has been achieved through the cleavage of aromatic C–N bonds from aniline derivatives [19, 20]. Palladium catalyzed C–C bond formation via olefin carbon nitrogen bond cleavage has been reported by Zhu et al. [21].

In this work, we report new preliminary findings of a selective cobalt or cerium mediated cleavage of the C–N bond of a benzoyl isothiocyanate derivative to give (carbamoylamino) methanethioamide. The cleavage of the C–N could not be achieved in the absence of the thione group. The novel silver-catalyzed conversion of the thione to the carbonyl has been achieved on (carbamoylamino) methanethioamide to produce bisurea, dicarbamolyamine. These researchers cannot claim that the cleavage reactions are metal-catalyzed since stoichiometric quantities of the metal ions were used, but more work needs to be done to ascertain the mechanism of the reaction; the first step would be to decode the intermediate species of the metal ions. Hence, the activation of the C–N bonds presented here is termed metal-mediated and not metal-catalyzed reactions.

2 Experimental methods

2.1 Reagent and instrumentation

Analytical grade reagents and solvents for synthesis such as ammonium thiocyanate, dimethyl sulfoxide, cerium nitrate hexahydrate, cobalt acetate tetrahydrate and toluene were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (USA) while silver nitrate, tetrahydrofuran, methanol, diethyl ether, ethyl acetate, benzoyl chloride, acetone, celite, ethanol and hexane were obtained from Merck Chemicals (SA). The chemicals were used as received (i.e. without further purification). 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance AV 400 MHz Spectrometer operating at 400 MHz for 1H and 100 MHz for 13C using DMSO-d6 as solvent and tetramethylsilane as internal standard. Chemical shifts are expressed in ppm. FT–IR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Platinum ATR Spectrophotometer Tensor 27. Elemental analyses were performed using a Vario Elementar Microcube ELIII. Melting points were obtained using a Stuart Lasec SMP30. Masses were determined using an Agilent 7890A GC system connected to a 5975C VL–MSC with an electron impact as the ionization mode and detection by a triple-axis detector. The GC was fitted with a 30 m x 0.25 mm x 0.25 μm DB-5 capillary column. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.6 mL.min–1 with an average velocity of 30.2 cm s–1 and a pressure of 63.7 KPa.

2.2 Preparation

2.2.1 1-((Benzamido)sulfanylenemethyl)urea (I)

1-((Benzamido)sulfanylenemethyl) urea was accessed by dissolving ammonium thiocyanate (0.04 mol, 3.05 g) in 80 mL of acetone; benzoyl chloride (0.04 mol, 5.62 g) was then added and heated under reflux for 2 h. The benzoyl isothiocyanate solution was filtered to remove ammonium chloride, and the urea (0.04 mol, 2.40 g) was then added to the resulting benzoyl isothiocyanate solution and refluxed for 6 h. The initial liquid stood overnight in a fume hood. The obtained product was filtered and recrystallized from DMSO:Toluene (1:1) as a yellow solid. Melting point = 124–126°C. Yield = 88%. 1H NMR (ppm): 11.23 (s, 1H, N–H), 9.86 (s, 1H, N–H), 9.56 (s, 1H, N–H), 7.94 (d, 2H, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.64 (t, 1H, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.51 (t, 2H, J = 7.6 Hz). 13C NMR (ppm): 182.4 (C=S), 168.4 (C=O), 133.3, 132.3, 129.0, IR (νmax, cm–1): 3343 (N–H), 3197 (N–H), 1691 (C=O), 1651 (C=O), 1615 (C=C), 1577 (C=C), 1528 (C–N), 1489 (C–N), 1449 (C–N). Anal. Calcd for C9H9N3O2S: C, 48.42; H, 4.06; N, 18.82; S, 14.36. Found: C, 48.53; H, 4.01; N, 18.34; S, 14.45. LRMS (m/z, M+): Found for C9H9N3O2S = 223.10, expected mass = 223.25.

2.2.2 1-((Benzamido)formyl)urea (II)

1-((Benzamido) sulfanylenemethyl)urea (0.009 mol, 2.03 g) was dissolved in tetrahydrofuran in the presence of silver nitrate (0.009 mol, 1.55 g) and heated under reflux in tetrahydrofuran (20 mL) for 24 h. The reaction mixture was then extracted with diethyl ether:methanol (1:1) (100 mL) and filtered over celite. The solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. The product was recrystallized from DMSO:Toluene (1:1) as a white puffy solid with a melting point of 204–206°C. Yield = 33.0%. 1H NMR (ppm): 11.42 (s, 1H, N–H,), 10.33 (s, 1H, N–H), 8.02 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.72 (t, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.60 (t, 2H, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.47 (s, 1H, N–H). 13C NMR (ppm): 169.6 (C=O), 132.1, 128.9, 127.8. IR (νmax, cm–1): 3345 (N–H), 3225 (N–H), 1711 (C=O), 1664 (C=O), 1598 (C=C), 1578 (C=C), 1466 (C–N). Anal. Calcd for C9H9N3O3: C 52.17; H, 4.38; N, 20.28. Found: C 52.37; H, 4.45; N, 20.40. LRMS (m/z, M+): Found for C9H9N3O3 = 207.06, expected mass = 207.19.

2.2.3 (Carbamoylamino)methanethioamide (III)

Compound I (0.01 mol, 2.23 g) was dissolved in 30 mL of solvent (methanol or tetrahydrofuran) 0.01 mol of cerium nitrate hexahydrate (in tetrahydrofuran) or cobalt acetate tetrahydrate (in methanol) and heated under reflux at 100-120°C for 24 h. The solvent was removed at the pump, and the product was purified on the column using ethyl acetate: hexane (1:1). The product recrystallized from ethanol: acetone (1:1) as a colorless solid with a melting point of 113–115°C. Yield = 76%. 1H NMR (ppm): 9.69 (s, N–H, 1H), 9.49 (s, N–H, 1H), 8.95 (s, N–H, 1H), 6.95 (br, N–H, 1H), 6.33 (br, N–H, 1H), 13C NMR (ppm): 181.7 (C=S), 155.0 (C=O). IR (νmax, cm–1): 3438 (N–H), 3367 (N–H), 3167(N–H), 1716 (C=S), 1699 (C=O), 1438 (C–N). Anal. Calcd for C2H5N3OS·H2O: C, 17.51; H, 5.14; N, 30.64; S, 23.37. Found: C, 17.42; H, 4.98; N, 30.95; S, 23.62. LRMS (m/z, M+): Found for C2H5N3OS = 119.36, expected mass = 119.15.

2.2.4 Dicarbamolyamine (IV)

Compound III (0.0003 mol, 0.036 g) and silver nitrate (0.0003 mol, 0.051 g) were heated under reflux in tetrahydrofuran (20 mL) for 24 h. The reaction mixture was then extracted with diethyl ether:methanol (1:1) (100 mL) and filtered over celite. The solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. The product was recrystallized from DMSO:Toluene (1:1) as a light brown solid with a melting point of 98–101°C. Yield = 35%. 1H NMR (ppm): 10.20 (s, N–H, 1H), 9.87 (s, N–H, 1H), 9.74 (s, N–H, 1H), 9.49 (s, N–H, 1H). 13C NMR (ppm): 155.3 (C=O). IR (νmax, cm–1): 3377 (N–H), 3334 (N–H), 3234 (N–H), 1654 (C=O), 1470 (C–N). Anal. Calc for C2H5N3O2: C, 23.30; H, 4.89; N, 40.76. Found: C, 23.42; H, 4.82; N, 40.83. LRMS (m/z, M2+): Found for C2H5N5O2 = 105.1, expected mass = 105.08.

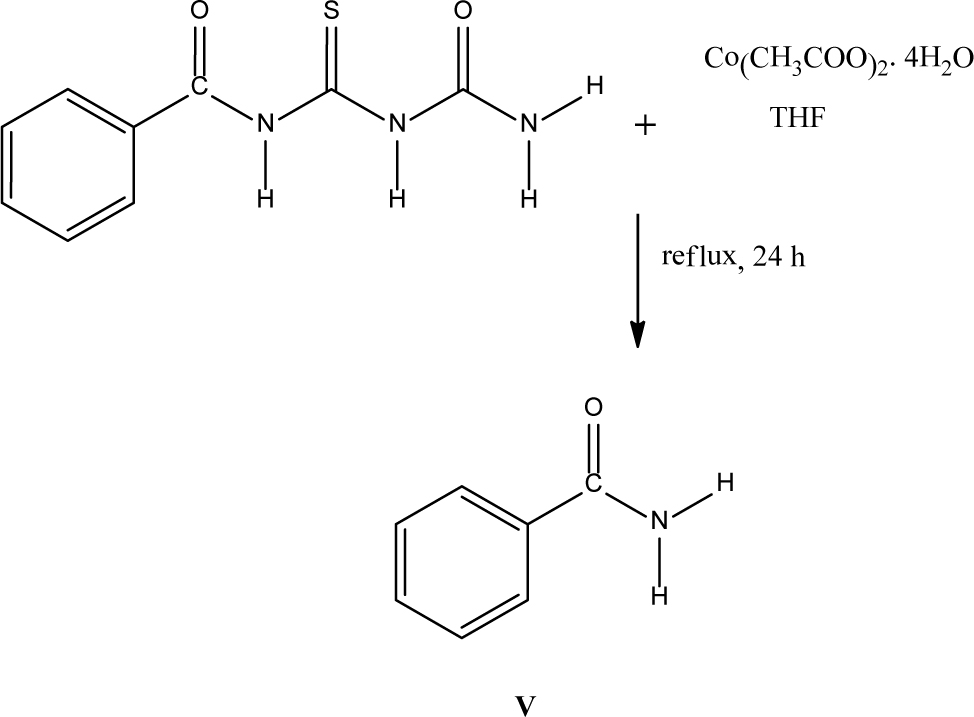

2.2.5 Benzamide (V)

1-((Benzamido)sulfanylenemethyl)urea (0.01 mol, 2.23g) was dissolved in tetrahydrofuran. Cobalt acetate tetrahydrate (0.01 mol) was then added and heated under reflux for 24 h. The product was filtered through celite, and the solvent was removed by slow evaporation. The product recrystallized from ethanol as a colorless solid with a melting point of 172–174°C. Yield = 55.0%. 1H NMR (ppm): 7.97 (s, N–H, 1H), 7.85 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.52 (t, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.47 (t, 2H, J = 7.6 Hz). 13C NMR ( ppm): 168.4 (C=O), 134.9 (C), 131.8 (C–H), 128.7 (C–H), 127.9 (C–H). IR (νmax, cm–1): 3323 (N–H), 3120 (N–H), 1670 (C=O), 1596 (C=C), 1523 (C=C), 1448 (C–N). Anal. Calcd for C7H7NO: C 69.41; H, 5.82; N, 11.56. Found: C 69.35; H, 5.76; N, 11.48. LRMS (m/z, M+): Found for C7H7NO = 121.06, expected mass = 121.14.

2.2.6 X-ray crystallography

X-ray diffraction analysis of 1-((benzamido) sulfanylenemethyl) urea (I),1-([benzamido]formyl) urea (II), carbamoylamino)methanethioamide (III) and benzamide (V) were performed at 200 K using a Bruker Kappa Apex II diffractometer with monochromated Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). APEXII [22], was used for data collection and SAINT [22], for cell refinement and data reduction. The structures were solved using direct methods such as SHELXS–2013 [22] and refined by least-squares procedures using SHELXL–2013 [23], with SHELXLE [24], as a graphical interface. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. Carbon-bound H atoms were placed in calculated positions (C–H 0.95 Å for aromatic carbon atoms and C–H 0.99 Å for methylene groups) and were included in the refinement in the model approximation, with Uiso (H) set to 1.2Ueq (C). The H atoms of the methyl groups were allowed to rotate with a fixed angle around the C–C bond to best fit the experimental electron density (HFIX 137 in the SHELX program suite [23]), with Uiso (H) set to 1.5 Ueq (C). Nitrogen-bound H atoms were located on a different Fourier map and refined freely. Data were corrected for absorption effects using the numerical method implemented in SADABS [24].

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animals use.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Synthesis and spectroscopic characterization of compounds

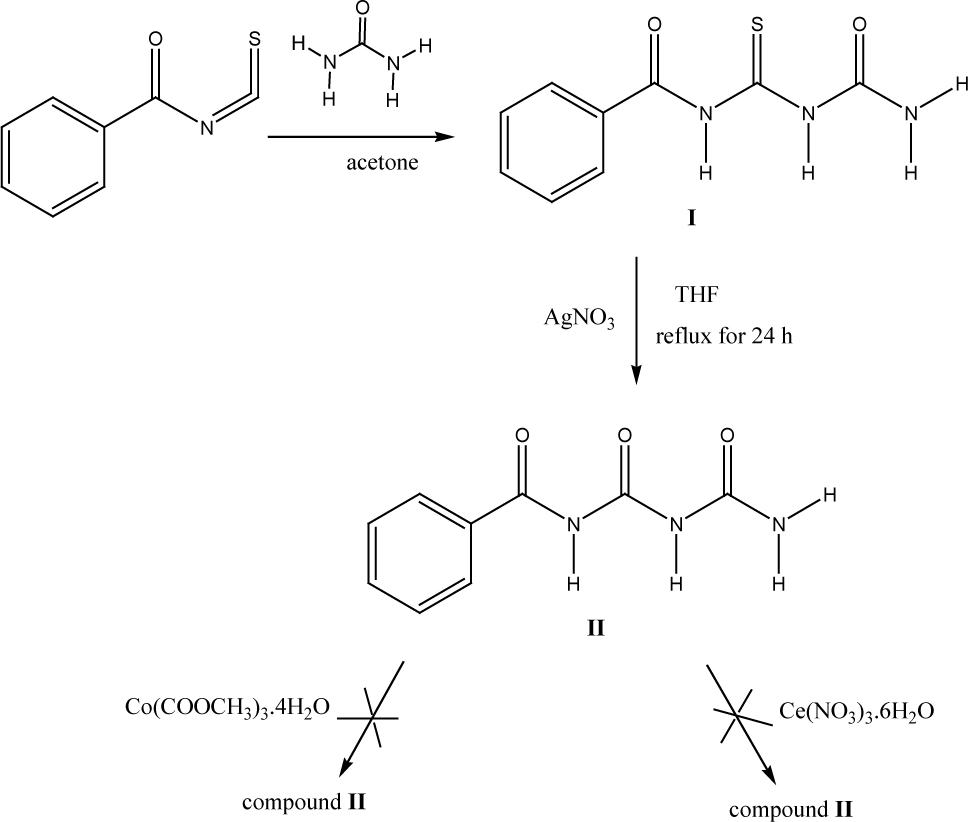

In the synthesis of compound I, urea attacks the benzoyl isothiocyanate on the electrophilic carbon of the thiocyanate moiety. Potassium thiocyanate in acetone has been reported to react with benzoyl chloride [25] to form isothiocyanate. Urea was added and heated at 55°C for 5 h, and this gave a yield of 30% while heating under a reflux of acetone for 6 h gave a yield of 88%. The IR spectrum showed bands at 3343 and 3197 cm-1 for N–H intervals. Signals were observed at 1691 and 1651 cm–1for the C=O stretch. While signals for the C=C intervals were observed at 1615 and 1577 cm-1, signals for C–N intervals were observed at 1528, 1489 and 1449 cm-1. The 1H NMR spectrum of compound I showed singlet signals at 11.23, 9.86 and 9.56 ppm for the N–H protons which were consistent with signals of protons attached to a nitrogen atom making them occur downfield. A doublet signal for an aromatic proton was observed at 7.94 ppm for two protons, while a triplet signal for one proton was observed at 7.64 ppm, also a signal for two aromatic protons resonated at 7.51 ppm. The 13C NMR spectrum showed signals at 182.4 and 168.4 ppm for the C=S and the C=O of a carbonyl respectively. Signals for aromatic carbons occurred between 133.3 and 129.0 ppm.

Compound II was formed by the silver mediated substitution of sulfur with oxygen in compound I; the source of oxygen was presumably water, and the silver by-product was also presumably an allotrope of silver sulfide. The IR spectrum showed bands for the N–H intervals at 3345 and 3225 cm–1. The band for the C=O interval was observed at 1710 cm–1 [26]. A band for the C=N and the aromatic C=C were observed at 1663 and 1598 cm–1, respectively [27], suggesting that the C–N were not distinct single bonds. The 1H NMR spectrum gave three single signals at 11.42, 10.33 and 7.47 ppm for the N–H protons, a double signal was observed for two protons at 8.02 ppm while a triple signal for a proton was observed at 7.72 ppm; another triple signal was observed at 7.60 ppm for two protons. The 13C NMR spectrum gave a signal at 169.6 ppm for the carbonyl. Signals between 132.1 and 127.8 ppm were observed for aromatic carbons.

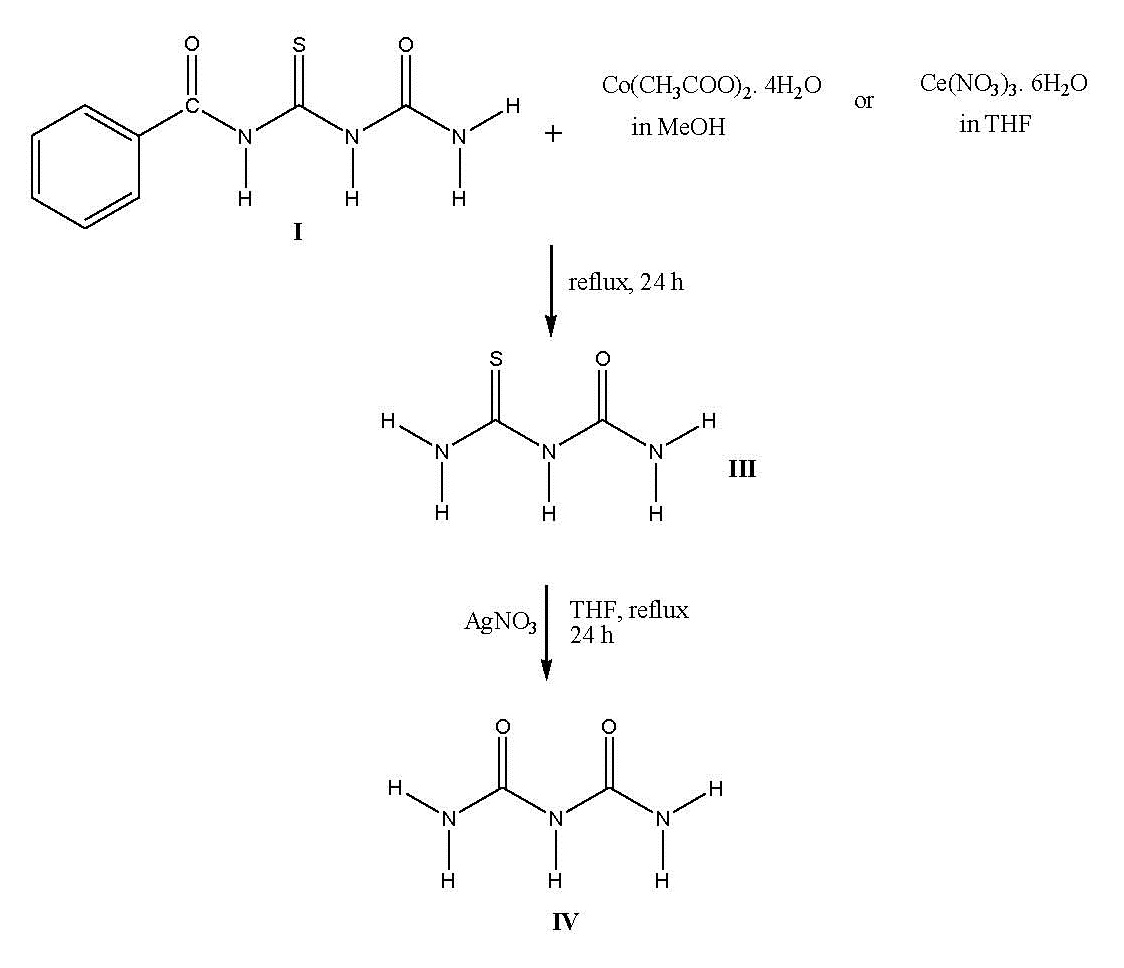

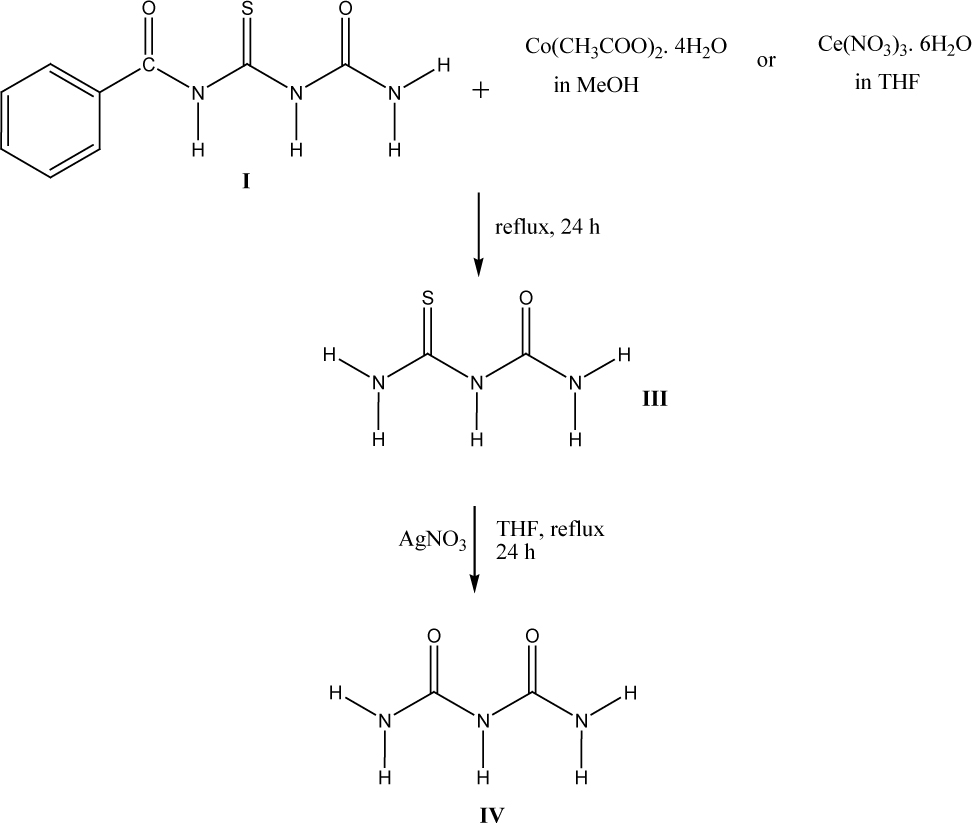

An attempt to cleave the C–N bond, in the a position to the benzoyl group of compound II using cobalt acetate tetrahydrate or cerium nitrate hexahydrate was not successful as only the initial material was obtained (Scheme 5). But the cleavage was successful when compound I was used as the initial material (Scheme 6).

![Scheme 1 Transition-metal-catalyzed direct arylation of arenes by C–H bond cleavage [11].](/document/doi/10.1515/chem-2018-0058/asset/graphic/j_chem-2018-0058_fig_006.jpg)

Transition-metal-catalyzed direct arylation of arenes by C–H bond cleavage [11].

![Scheme 2 Cobalt-catalyzed peroxidation of 2-oxindoles with hydroperoxides [12].](/document/doi/10.1515/chem-2018-0058/asset/graphic/j_chem-2018-0058_fig_007.jpg)

Cobalt-catalyzed peroxidation of 2-oxindoles with hydroperoxides [12].

![Scheme 4 Palladium catalyzed C–N bond cleavage resulting in C–C coupling [21].](/document/doi/10.1515/chem-2018-0058/asset/graphic/j_chem-2018-0058_fig_009.jpg)

Palladium catalyzed C–N bond cleavage resulting in C–C coupling [21].

Synthesis of compounds I and II.

Synthesis of compounds III and IV.

This showed that the cobalt and cerium catalyzed cleavage reaction required the presence of the thione group for the cleavage to occur, possibly due to the weakening of the C–N bond by the polarizing effect of the sulfur. Compound III was formed by the cerium nitrate hexahydrate or cobalt acetate tetrahydrate mediated cleavage of compound I in THF and methanol, respectively. The IR spectrum showed bands at 3438, 3367 and 3167 cm–1 for the N–H interval, a band was observed at 1716 cm-1 for the C=S interval [28], while the C=O interval was observed at 1699 cm–1. The 1H NMR spectrum of compound III showed single resonances for protons at 9.69, 9.49 and 8.95 ppm, while broad signals for protons were also observed at 6.95 and 6.33 ppm. The 13C NMR spectrum gave resonances at 181.7 for the (C=S) of a thione and 155.0 for the C=O of a carbonyl.

The cobalt acetate mediated cleavage of compound I in THF gave a benzamide (V) as the only isolable product (Scheme 7). The reaction of cobalt acetate tetrahydrate with benzoyl iosthiocyanate derivatives yielded a benzamide (V) as one of the side products regardless of the initial material. This reaction was confirmed using three different benzoyl isothiocyanate derivatives. But with methanol as a solvent, (carbamoylamino) methanethioamide (III) was obtained. Cobalt cleaves benzamide from 1-((benzamido) sulfanylenemethyl)urea (I) in a non-specific way resulting in a mixture of products. But cobalt acetate tetrahydrate in methanol yields (carbamoylamino) methanethioamide and possibly benzoic acid. Scheme 6 gives the synthesis scheme for the synthesis of compounds III and IV with the last step being the silver reaction. The IR spectrum of compound IV, dicarbamolyamine, showed bands at 3377, 3334 and 3234 cm–1 for the N–H interval, and a band was observed at 1654 cm–1 for the C=O interval. The 1H NMR spectrum of compound IV showed single resonances for protons at 10.20, 9.87, 9.74 and 9.49 ppm due to the amine protons. To our knowledge, this is the first presentation of dicarbamolyamine in the literature, the closest derivatives being diacyl ureas which were recently published by Hernandez et al. [29].

Synthesis of compound V.

3.2 Crystal structures of compounds I, II, III and V

X-ray crystal structures of the compounds I, II, III and V were obtained using single crystals grown by crystallization. Table 1 and 2 shows the crystallographic data, selected bond lengths and bond angles for the crystal structures of compounds I, II, III and V.

Crystallographic data and structure refinement summary for compounds I, II, III, and V.

| Property | Compound I | Compound II | Compound III | Compound V |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formula | C9H9N3O2S | C9H9N3O3 | C2H5N3OS, H2O | C7H7NO |

| CCDC Numbers | 1549036 | 1549037 | 1836320 | 1549034 |

| Formula Weight | 223.26 | 207.19 | 137.17 | 121.14 |

| Crystal System | Monoclinic | Monoclinic | Monoclinic | Monoclinic |

| Space group | C2/c | P21/c | P21/m | P21/c |

| a [Ǻ] | 10.2528(5) | 7.8993(4) | 9.2101(7) | 5.5666(3) |

| b [Ǻ] | 12.8418(6) | 22.3734(10) | 6.2485(5) | 5.0317(3) |

| c [Ǻ] | 16.0986(7) | 5.1861(2) | 10.2174(8) | 21.7543(15) |

| α [°] | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| β [°] | 106.159(2) | 99.912(2) | 103.340(4) | 90.184(3) |

| γ [°] | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| V [Å^3] | 2035.87(16) | 902.88(7) | 572.14(8) | 609.32(6) |

| Z | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| D(calc) [g/cm^3] | 1.457 | 1.524 | 1.592 | 1.321 |

| Mu(MoKa) [ /mm ] | 0.301 | 0.118 | 0.478 | 0.090 |

| F(000) | 928 | 432 | 288 | 256 |

| Crystal Size [mm] | 0.24 × 0.41 × 0.47 | 0.04 x0.32 × 0.62 | 0.40 × 0.47 × 0.55 | 0.08 × 0.13 × 0.34 |

| Temperature | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| Radiation MoKa, [Ǻ] | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 |

| Theta Min-Max [°] | 2.6, 28.3 | 1.8, 28.3 | 2.0, 28.4 | 3.7, 28.4 |

| Dataset | -9: 13 ; -13: 17 ; -21: | 21 -9: 10 ; -29: 29 ; -6: | 6 -12: 12 ; -8: 8 ; -5: 13 | -7: 7 ; -6: 6 ; -29: 29 |

| Tot., Uniq. Data, R(int) | 9431, 2514, 0.013 | 12790, 2244, 0.022 | 1550, 1550, 0.000 | 5655, 1514, 0.015 |

| Observed Data [I > 2.0 | 2215 | 1939 | 1478 | 1267 |

| sigma(I)] | ||||

| Nref | 2514 | 2244 | 1550 | 1514 |

| Npar | 152 | 152 | 136 | 90 |

| R | 0.0351 | 0.0354 | 0.0292 | 0.0367 |

| wR2 | 0.1000 | 0.0948 | 0.0812 | 0.1050 |

| S | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.09 | 1.03 |

| Max. and Av. Shift/Error | 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00 |

| Min. and Max. Resd. Dens. [e/Å^3] | -0.58 | -0.22 | -0.26 | -0.17 |

| Min. and Max. Resd. Dens. [e/Å^3] | 0.47 | 0.30 | 0.44 | 0.35 |

Selected bond lengths (Å) and bond angles (°) for compounds I, II, III and V.

| Bond lengths (Å) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | V | ||||

| S1-C2 | 1.648(1) | O1-C1 | 1.220(1) | S1-C11 | 1.697(2) | O1-C7 | 1.240(1) |

| O1-C1 | 1.215(2) | O2-C2 | 1.218(1) | N21-C21 | 1.307(3) | C3-C4 | 1.375(2) |

| O2-C3 | 1.239(2) | O3-C3 | 1.229(1) | S2-C21 | 1.708(2) | N1-C7 | 1.330(2) |

| N1-C1 | 1.386(2) | N1-C1 | 1.377(1) | N22-C21 | 1.365(2) | C4-C5 | 1.384(2) |

| N1-C2 | 1.367(2) | N1-C2 | 1.396(1) | O1-C12 | 1.240(2) | C1-C2 | 1.389(2) |

| N2-C3 | 1.402(2) | N2-C2 | 1.359(1) | N22-C22 | 1.396(2) | C5-C6 | 1.388(2) |

| N3-C3 | 1.325(2) | N2-C3 | 1.410(1) | N11-C11 | 1.312(2) | C1-C6 | 1.386(2) |

| N2-C2 | 1.374(2) | N3-C3 | 1.327(1) | N23-C22 | 1.327(2) | C1-C7 | 1.499(2) |

| Bond angles (°) | |||||||

| I | II | III | V | ||||

| C1-N1-C2 | 128.8(1) | C1-N1-C2 | 129.1(1) | C11-N12-C12 | 127.8(2) | C2-C1-C6 | 119.5(1) |

| C2-N2-C3 | 128.6(1) | O1-C1-N1 | 121.7(1) | S2-C21-N21 | 122.0(1) | O1-C7-C1 | 120.3(1) |

| N2-C3-N3 | 113.9(1) | N1-C2-N2 | 116.6(1) | S1-C11-N11 | 121.8(1) | C2-C1-C7 | 122.0(1) |

| O2-C3-N3 | 124.4(1) | O2-C2-N2 | 124.9(1) | S2-C21-N22 | 118.5(1) | C6-C1-C7 | 118.5(1) |

| S1-C2-N2 | 118.2(1) | O2-C2-N1 | 118.6(1) | S1-C11-N12 | 118.7(1) | C1-C2-C3 | 120.0(1) |

| N1-C2-N2 | 114.2(1) | O3-C3-N3 | 124.9(1) | N21-C21-N22 | 119.5(2) | C2-C3-C4 | 120.2(1) |

| O2-C3-N2 | 121.8(1) | N2-C3-N3 | 117.9(1) | N11-C11-N12 | 119.4(2) | C3-C4-C5 | 120.3(1) |

| S1-C2-N1 | 127.6(1) | O3-C3-N2 | 117.2(1) | O2-C22-N22 | 123.0(2) | C4-C5-C6 | 119.8(1) |

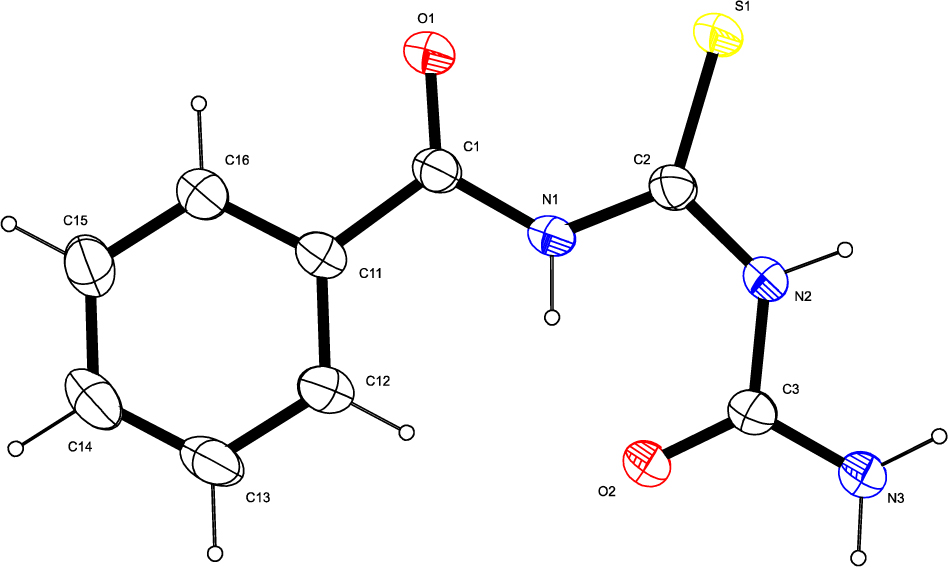

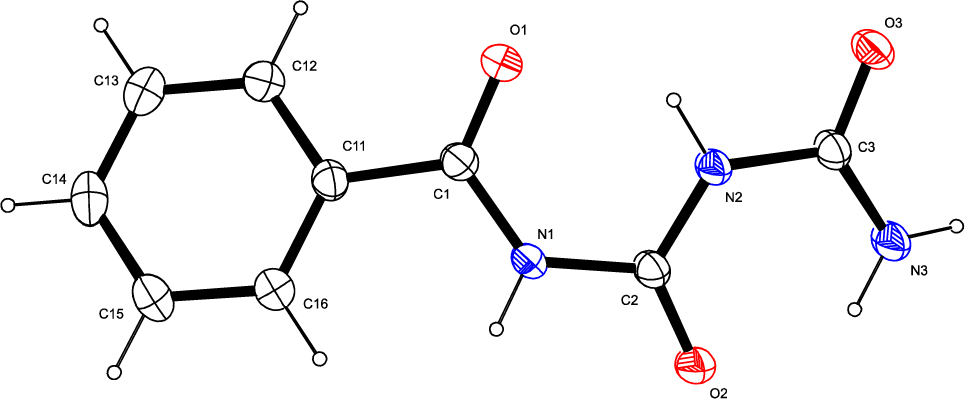

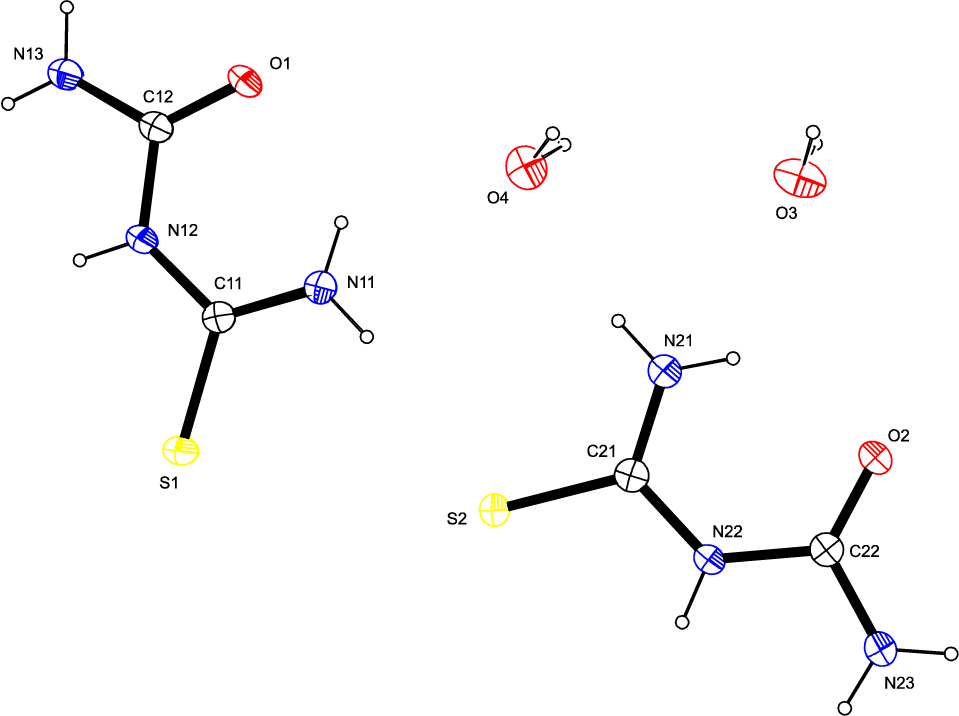

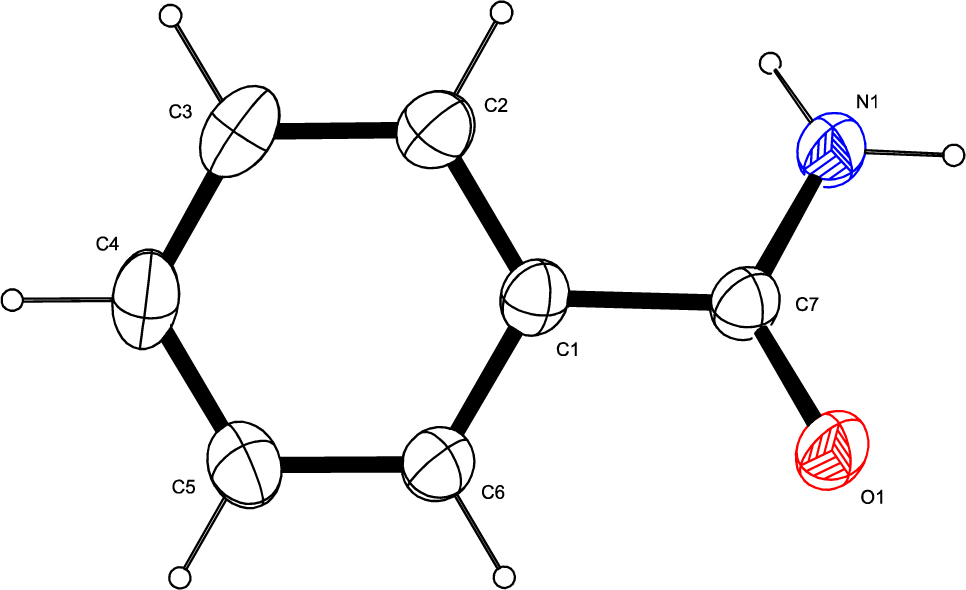

Compound I was recrystallized from DMSO:Toluene (1:1) and obtained as a yellow solid. It recrystallized in the monoclinic space group C2/c while compound II was recrystallized from DMSO:Toluene (1:1) as a white solid. It was crystallized in the monoclinic space group P21/c. The ORTEP diagram for compound I is presented in Figure 2 while the ORTEP diagram for compound II is presented in Figure 3. Compound III was recrystallized from ethanol: acetone (1:1) and obtained as a colorless solid. It recrystallized in the monoclinic space group P21/m. Figure 4 shows the ORTEP diagram for compound III, while Figure 5 displays the ORTEP diagram for compound V. Compound V was recrystallized from ethanol as a colorless solid in the monoclinic space group P21/c.

An ORTEP view of 1-((benzamido) sulfanylenemethyl) urea (I) shows 50% probability displacement ellipsoids and the atom labeling.

An ORTEP view of 1-((benzamido)formyl) urea (II) shows 50% probability displacement ellipsoids and the atom labeling.

An ORTEP view of (carbamoylamino) methanethioamide (III) shows 50% probability displacement ellipsoids and the atom labeling.

An ORTEP view of benzamide (V) shows 50% probability displacement ellipsoids and the atom labeling.

The bond distance of O1-C1 in compound I which was 1.215(2) Å, is consistent with a carbonyl while the N1-C1, N1-C2, and N2-C3 bond distances in compound I were 1.386(2), 1.367(2) and 1.402(2) Ǻ respectively which were consistent with the C–N single bond [30]. The bond distance of S1-C2, which was 1.648 (2) Ǻ, is consistent with a bond length of a thione [31]. The bond angles of O2-C3-N2 and S1-C2-N1 are 121.8(1) and 127.6(1) respectively showed that the carbon atom is sp2 hybridized.

In the crystal structure of compound II, the carbonyl group (O2-C2) is in an opposite position from the benzoyl carbonyl while the thione group in compound I is aligned. The oxygen and sulfur atoms are as far removed from each other as possible to reduce repulsion between their respective electron densities. The bond distances of O1-C1, O2-C2, O3-C3 which were 1.220(1), 1.218(1) and 1.229(1) Å, respectively, were consistent with a carbonyl while the N1-C1, N1-C2, N2-C2 and N2-C3 bond distances in compound II were 1.377(1), 1.396(1), 1.359(1) and 1.410(1) Ǻ respectively and consistent with the C–N single bond [31]. The bond angles of O1-C1-N1, N1-C2-N2 and O2-C2-N2 were 121.7(1), 116.6(1) and 124.9(1) respectively.

In compound III, the bond distances of O1-C12 and O2-C22 in compound III were 1.240(2) and 1.234(2) Å respectively, and were consistent with a carbonyl, while the N21-C21, N11-C11 and N12-C11 bond distances in compound III were 1.307(3), 1.312(2), and 1.366(2)Ǻ respectively which were also consistent with the C–N single bond. However, these were stronger C–N bonds. The S1-C11 and S2-C21 were also found to be 1.697(2) and 1.708(2) respectively. The bond angles of S2-C21-N21, S1-C11-N11 and S2-C21-N22, O2-C2-N2 were 122.0(1), 121.8(1) and 118.5(1) respectively, while the N11-C11-N12, N22-C22-N23, N12-C12-N13 were 119.4(2), 113.2(2), and 113.2(2) respectively. These were comparable to reported values [32].

The bond distances of O1-C7 in compound V which were 1.240(1) unit were consistent with a carbonyl while the N1-C7 bond distances in compound V were 1.330(2) unit, consistent with the C-N single bond [33]. The bond distances of C3-C4, C4-C5 and C1-C2, were 1.375(2), 1.384(2) and 1.389(2) unit respectively. The bond angles of C2-C1-C6, C1-C2-C3, and O1-C7-C1 were 119.5(1), 120.0(1) unit and 120.3(1) respectively.

Because of the strength of the C–N bonds, it is not easy to justify the observed reactions. The benzamide formation is probably the only one that fits the justification for its formation as the C–N bonds in the β position to the benzoyl group were weaker than the rest found in compounds 1 and II. It is clear therefore, that the metals play a significant role in these reactions to activate the C–N bond cleavage. A further study will be the detailed mechanisms of these reactions as well as the formation of 3,5-diamino- 1,2,4-triazole by a reaction with hydrazine and synthesis of a new urea-formaldehyde resin which will be compared with the current standard using monomeric urea.

4 Conclusions

A novel selective C–N bond cleavage of a benzoyl isothiocyanate derivative to give (carbamoylamino) methanethioamide has been achieved using cobalt acetate tetrahydrate in methanol. The product has also been accessed using cerium nitrate hexahydrate as a catalyst in THF. The cleavage of the C–N bond does not occur in the absence of the thione group in compound II. A novel silver catalyzed conversion of a thione to the carbonyl has been achieved on 1-([benzamido]formyl)urea (I) and replicated on (carbamoylamino) methanethioamide (III) to give bisurea (dicarbamolyamine). The structures of the compounds have been confirmed using IR, NMR, microanalysis and GC-MS. Single crystal X-ray diffraction studies of the crystal structures of compounds I, II, III and V have been presented. These show evidence of the formation of the new molecules via metal mediation, and a further study is to investigate the detailed mechanisms of these reactions.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material CCDC-1549036 for 1, CCDC-1549037 for II, CCDC-1836320 for III and CCDC-1549034 for V contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge at www.ccdc.cam.ac. uk/conts/ retrieving.html or from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44(0)1223-336033; e-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam. ac.uk.

Acknowledgements

We thank MRC for the research funding (MRC-SIR). F. Odame thanks the National Research Foundation for awarding him a postdoctoral Fellowship.

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

Supplemental Material: The online version of this article offers supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/chem-2018-0058).

References

[1] Siddiqui N., Arshad, M.F., Ahsan W., Alam M.S., Thiazoles: a valuable insight into the recent advances and biological activities, Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Drug Res., 2009, 1(3), 136–143.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Yu H., Shao L., Fang J., Synthesis and biological activity research of novel ferrocenyl-containing thiazole imine derivatives, J. Organomet. Chem., 2007, 692, 991–996.10.1016/j.jorganchem.2006.10.059Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Bruno F.P., Caira M.R., Martin E.C., Monti G.A., Sperandeo N.R., Characterization and structural analysis of the potent antiparasitic and antiviral agent tizoxanide, J. Mol. Struc., 2013, 1036, 318–325.10.1016/j.molstruc.2012.12.004Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Odame F., Hosten E.C., Betz R., Lobb K., Tshentu Z.R., Characterization of some amino acid derivatives of benzoyl isothiocyanate: Crystal structures and theoretical prediction of their reactivity J. Mol. Struc, 2015, 1099, 38–48.10.1016/j.molstruc.2015.05.053Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Hodgetts K.J., Kershaw T.M., Regiocontrolled synthesis of substituted thiazoles, Org. Lett., 2002, 8, 1363–1365.10.1021/ol025688uSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Ochiai M., Nishi Y., Hashimoto S., Tscuhimoto Y., Chen D.W., Synthesis of 2,4-disubstituted thiazoles from (Z)-(2-acetoxyvinyl)phenyl-λ3-iodanes: nucleophilic substitution of r-λ3-Iodanyl ketones with thioureas and thioamides, J. Org. Chem., 2003, 68, 7887–7888.10.1021/jo020759oSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Allevi P., Ciuffreda P., Tarcco G., Anastasia M., Enzymatic resolution of (R)- and (S)-2-(1-hydroxyalkyl)thiazoles, synthetic equivalents of (R)- and (S)-2-hydroxy aldehydes, J. Org. Chem., 1996, 61, 4144–4147.10.1021/jo952082tSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Williams G.D., Pike R.A., Wade, C.E., Wills M., A one-pot process for the enantioselective synthesis of amines via reductive amination under transfer hydrogenation conditions, Org. Lett., 2003, 22, 4227–4230.10.1021/ol035746rSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Izumisawa Y., Togo H. Preparation of α-bromoketones and thiazoles from ketones with NBS and thioamides in ionic liquids, Green and Sustainable Chem., 2011, 1, 54–62.10.4236/gsc.2011.13010Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Ngaini Z., Zulkiplee W.S.H.W., Halim A.N.A., One-pot multicomponent synthesis of thiourea derivatives in cyclotriphosphazenes moieties, J. Chem., 2017, Article ID 1509129, 1–710.1155/2017/1509129Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Ackermann L., Vicente R., Kapdi A.R., Transition-metal-catalyzed direct arylation of (hetero)arenes by C–H bond cleavage, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2009, 48, 9792–9826.10.1002/anie.200902996Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Li Y., Wang M., Fan W., Qian F., Li G., Hongjian Lu. Cobalt-catalyzed cross-dehydrogenative coupling reactions of (benz) oxazoles with ethers, J. Org. Chem., 2016, 81, 11743–11750.10.1021/acs.joc.6b02211Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Geibel I., Dierks A., Schmidtmann M., Christoffers J., Formation of δ-lactones by cerium-catalyzed, Baeyer–Villiger-type coupling of β-oxoesters, enol acetates, and dioxygen, J. Org. Chem., 2016, 81, 7790–7798.10.1021/acs.joc.6b01441Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Castillo T.J.D., Thompson N.B., Suess D.L.M., Ung G., Peters J.C., Evaluating molecular cobalt complexes for the conversion of N2 to NH3, Inorg. Chem, 2015, 54, 9256–9262.10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b00645Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Zhang Q., Bell-Taylor A., Bronston F.M., Gorden J.D., Goldsmith C.R. Aldehyde deformylation and datalytic C–H activation resulting from a shared cobalt(II) precursor, Inorg. Chem., 2017, 56, 773–782.10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b02127Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Schwab P., France M.B., Ziller J.W., Grubbs R.H., A Series of well-defined metathesis catalysts-synthesis of [RuCl2(ͰCHR’) (PR3)2] and its reactions, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 1995, 34(18): 2039–2041.10.1002/anie.199520391Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Scholl M., Trnka T.M., Morgan J.P., Grubbs R.H., Increased ring closing metathesis activity of ruthenium-based olefin metathesis catalysts coordinated with imidazolin-2-ylidene ligands, Tetrahedron Lett., 1999, 40(12), 2247–2250.10.1016/S0040-4039(99)00217-8Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Ouyang K., Hao W., Zhang W. X., Xi Z., Transition-metal-catalyzed cleavage of C–N single bonds, Chem. Rev., 2015, 115, 12045–12090.10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00386Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Ueno S., Chatani N., Kakiuchi F., Ruthenium-Catalyzed Carbon-Carbon Bond Formation via the Cleavage of an Unreactive Aryl Carbon-Nitrogen Bond in Aniline Derivatives with Organoboronates, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2007, 129, 6098–6099.10.1021/ja0713431Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Koreeda T., Kochi T., Kakiuchi F. Substituent effects on stoichiometric and catalytic cleavage of carbon-nitrogen bonds in aniline derivatives by ruthenium-phosphine complexes, Organometallics, 2013, 32, 682–690.10.1021/om3011855Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Zhu M.K., Zhao J.F., Loh T.P., Palladium-catalyzed C–C bond formation of arylhydrazines with olefins via carbonnitrogen bond cleavage, Org. Lett., 2011, 13(23), 6308–631110.1021/ol202862tSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] APEX2, SADABS and SAINT. Bruker AXS Inc: Madison, WI, USA, 2010.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Sheldrick G.M., A short history of SHELX, Acta. Cryst. A, 2008, 64, 112–122.10.1107/S0108767307043930Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Hübschle C.B., Sheldrick G.M., Dittrich B., ShelXle: a Qt graphical user interface for SHELXL, J. Appl. Cryst., 2011, 44, 1281–1284.10.1107/S0108767319098143Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Kang S.K., Cho N. S., Jeon M.K., 1-Benzoyl-2-thiobiuret. Acta Cryst., 2012, E68, o395.10.1107/S1600536812000621Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Lewis R.N.A.H., McElhaney R.N., Walter Pohle W., Mantsch H.H., Components of the carbonyl stretching band in the infrared spectra of hydrated 1,2-diacylglycerolipid bilayers: a reevaluation, Biophy. J., 1994, 67, 2367–2375.10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80723-4Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Wiles D.M., Gingras, B.A., Suprunchuk, T., Canadian J. Chem., 1907, 5, 469.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Mishra A., Dwivedi J., Shukla K., Malviya P., X-Ray diffraction and fourier transformation infrared spectroscopy studies of copper (II) thiourea chloro and sulphate complexes, J. Phy: Conference Series, 2014, 534, 012014.10.1088/1742-6596/534/1/012014Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Hernandez A.G., Grooms G.M., El-Alfy A.T., Stec. J., Convenient one-pot two-step synthesis of symmetrical and unsymmetrical diacyl ureas, acyl urea/carbamate/thiocarbamate derivatives, and related compounds, Synthesis, 2017, 49(10), 2163–2176.10.1055/s-0036-1588724Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Allen F.H., Kennard O., David G., Watson D.G., Brammer L., Orpen A.G., Taylor R., Tables of bond lengths determined by X-ray and neutron diffraction. Part 1. bond lengths in organic compounds, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans., 1987, 2(1), S1–S19.10.1039/p298700000s1Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Kavak G., Őzbey S., Bǐnzet G., Kulcü N., Synthesis and single crystal structure analysis of three novel benzoylthiourea derivatives, Turk. J. Chem., 2009, 33, 857–868.10.3906/kim-0901-1Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Zhao X.Z., Jia J.J., Yang M.O., Huanga F.P., Jianga Y.M., 1-[2-(pyrazin-2-ylsulfanyl) ethyl]pyrazine-2(1H)-thione, Acta Cryst. E, 2011, 67, o418.10.1107/S1600536811001474Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Binzet G., Kavak G., Külcü N., Özbey S., Flörke U., Arslan H., Synthesis and Characterization of novel thiourea derivatives and their nickel and copper complexes, J. Chem., 2013, 1–9.10.1155/2013/536562Suche in Google Scholar

© 2018 Felix Odame et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- The effect of CuO modification for a TiO2 nanotube confined CeO2 catalyst on the catalytic combustion of butane

- The preparation and antibacterial activity of cellulose/ZnO composite: a review

- Linde Type A and nano magnetite/NaA zeolites: cytotoxicity and doxorubicin loading efficiency

- Performance and thermal decomposition analysis of foaming agent NPL-10 for use in heavy oil recovery by steam injection

- Spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, UV, 1H and 13C NMR) insights, electronic profiling and DFT computations on ({(E)-[3-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-1-phenylpropylidene] amino}oxy)(4-nitrophenyl)methanone, an imidazole-bearing anti-Candida agent

- A Simplistic Preliminary Assessment of Ginstling-Brounstein Model for Solid Spherical Particles in the Context of a Diffusion-Controlled Synthesis

- M-Polynomials And Topological Indices Of Zigzag And Rhombic Benzenoid Systems

- Photochemical Transformation of some 3-benzyloxy-2-(benzo[b]thiophen-2-yl)-4Hchromen-4-ones: A Remote Substituent Effect

- Dynamic Changes of Secondary Metabolites and Antioxidant Activity of Ligustrum lucidum During Fruit Growth

- Studies on the flammability of polypropylene/ammonium polyphosphate and montmorillonite by using the cone calorimeter test

- DSC, FT-IR, NIR, NIR-PCA and NIR-ANOVA for determination of chemical stability of diuretic drugs: impact of excipients

- Antioxidant and Hepatoprotective Effects of Methanolic Extracts of Zilla spinosa and Hammada elegans Against Carbon Tetrachlorideinduced Hepatotoxicity in Rats

- Prunus cerasifera Ehrh. fabricated ZnO nano falcates and its photocatalytic and dose dependent in vitro bio-activity

- Organic biocides hosted in layered double hydroxides: enhancing antimicrobial activity

- Experimental study on the regulation of the cholinergic pathway in renal macrophages by microRNA-132 to alleviate inflammatory response

- Synthesis, characterization, in-vitro antimicrobial properties, molecular docking and DFT studies of 3-{(E)-[(4,6-dimethylpyrimidin-2-yl)imino]methyl} naphthalen-2-ol and Heteroleptic Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Zn(II) complexes

- M-Polynomials and Topological Indices of Dominating David Derived Networks

- Human Health Risk Assessment of Trace Metals in Surface Water Due to Leachate from the Municipal Dumpsite by Pollution Index: A Case Study from Ndawuse River, Abuja, Nigeria

- Analysis of Bowel Diseases from Blood Serum by Autofluorescence and Atomic Force Microscopy Techniques

- Hydrographic parameters and distribution of dissolved Cu, Ni, Zn and nutrients near Jeddah desalination plant

- Relationships between diatoms and environmental variables in industrial water biotopes of Trzuskawica S.A. (Poland)

- Optimum Conversion of Major Ginsenoside Rb1 to Minor Ginsenoside Rg3(S) by Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Acid Hydrolysis Treatment

- Antioxidant, Anti-microbial Properties and Chemical Composition of Cumin Essential Oils Extracted by Three Methods

- Regulatory mechanism of ulinastatin on autophagy of macrophages and renal tubular epithelial cells

- Investigation of the sustained-release mechanism of hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose skeleton type Acipimox tablets

- Bio-accumulation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Grey Mangrove (Avicennia marina) along Arabian Gulf, Saudi Coast

- Dynamic Change of Secondary Metabolites and spectrum-effect relationship of Malus halliana Koehne flowers during blooming

- Lipids constituents from Gardenia aqualla Stapf & Hutch

- Effect of using microwaves for catalysts preparation on the catalytic acetalization of glycerol with furfural to obtain fuel additives

- Effect of Humic Acid on the Degradation of Methylene Blue by Peroxymonosulfate

- Serum containing drugs of Gua Lou Xie Bai decoction (GLXB-D) can inhibit TGF-β1-Induced Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in A549 Cells

- Antiulcer Activity of Different Extracts of Anvillea garcinii and Isolation of Two New Secondary Metabolites

- Analysis of Metabolites in Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz Dry Red Wines from Shanxi by 1H NMR Spectroscopy Combined with Pattern Recognition Analysis

- Can water temperature impact litter decomposition under pollution of copper and zinc mixture

- Released from ZrO2/SiO2 coating resveratrol inhibits senescence and oxidative stress of human adipose-derived stem cells (ASC)

- Validated thin-layer chromatographic method for alternative and simultaneous determination of two anti-gout agents in their fixed dose combinations

- Fast removal of pollutants from vehicle emissions during cold-start stage

- Review Article

- Catalytic activities of heterogeneous catalysts obtained by copolymerization of metal-containing 2-(acetoacetoxy)ethyl methacrylate

- Antibiotic Residue in the Aquatic Environment: Status in Africa

- Regular Articles

- Mercury fractionation in gypsum using temperature desorption and mass spectrometric detection

- Phytosynthetic Ag doped ZnO nanoparticles: Semiconducting green remediators

- Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Induced by SMAD4 Activation in Invasive Growth Hormone-Secreting Adenomas

- Physicochemical properties of stabilized sewage sludge admixtures by modified steel slag

- In Vitro Cytotoxic and Antiproliferative Activity of Cydonia oblonga flower petals, leaf and fruit pellet ethanolic extracts. Docking simulation of the active flavonoids on anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2

- Synthesis and Characterization of Pd exchanged MMT Clay for Mizoroki-Heck Reaction

- A new selective, and sensitive method for the determination of lixivaptan, a vasopressin 2 (V2)-receptor antagonist, in mouse plasma and its application in a pharmacokinetic study

- Anti-EGFL7 antibodies inhibit rat prolactinoma MMQ cells proliferation and PRL secretion

- Density functional theory calculations, vibration spectral analysis and molecular docking of the antimicrobial agent 6-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-ylmethyl)-5-ethyl-2-{[2-(morpholin-4-yl)ethyl] sulfanyl}pyrimidin-4(3H)-one

- Effect of Nano Zeolite on the Transformation of Cadmium Speciation and Its Uptake by Tobacco in Cadmium-contaminated Soil

- Effects and Mechanisms of Jinniu Capsule on Methamphetamine-Induced Conditioned Place Preference in Rats

- Calculating the Degree-based Topological Indices of Dendrimers

- Efficient optimization and mineralization of UV absorbers: A comparative investigation with Fenton and UV/H2O2

- Metabolites of Tryptophane and Phenylalanine as Markers of Small Bowel Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

- Adsorption and determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water through the aggregation of graphene oxide

- The role of NR2C2 in the prolactinomas

- Chromium removal from industrial wastewater using Phyllostachys pubescens biomass loaded Cu-S nanospheres

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Preparation of Calcium Fluoride using Phosphogypsum by Orthogonal Experiment

- The mechanism of antibacterial activity of corylifolinin against three clinical bacteria from Psoralen corylifolia L

- 2-formyl-3,6-bis(hydroxymethyl)phenyl benzoate in Electrochemical Dry Cell

- Electro-photocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin using calcium titanate

- Effect of Malus halliana Koehne Polysaccharides on Functional Constipation

- Structural Properties and Nonlinear Optical Responses of Halogenated Compounds: A DFT Investigation on Molecular Modelling

- DMFDMA catalyzed synthesis of 2-((Dimethylamino)methylene)-3,4-dihydro-9-arylacridin-1(2H)-ones and their derivatives: in-vitro antifungal, antibacterial and antioxidant evaluations

- Production of Methanol as a Fuel Energy from CO2 Present in Polluted Seawater - A Photocatalytic Outlook

- Study of different extraction methods on finger print and fatty acid of raw beef fat using fourier transform infrared and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- Determination of trace fluoroquinolones in water solutions and in medicinal preparations by conventional and synchronous fluorescence spectrometry

- Extraction and determination of flavonoids in Carthamus tinctorius

- Therapeutic Application of Zinc and Vanadium Complexes against Diabetes Mellitus a Coronary Disease: A review

- Study of calcined eggshell as potential catalyst for biodiesel formation using used cooking oil

- Manganese oxalates - structure-based Insights

- Topological Indices of H-Naphtalenic Nanosheet

- Long-Term Dissolution of Glass Fibers in Water Described by Dissolving Cylinder Zero-Order Kinetic Model: Mass Loss and Radius Reduction

- Topological study of the para-line graphs of certain pentacene via topological indices

- A brief insight into the prediction of water vapor transmissibility in highly impermeable hybrid nanocomposites based on bromobutyl/epichlorohydrin rubber blends

- Comparative sulfite assay by voltammetry using Pt electrodes, photometry and titrimetry: Application to cider, vinegar and sugar analysis

- MicroRNA delivery mediated by PEGylated polyethylenimine for prostate cancer therapy

- Reversible Fluorescent Turn-on Sensors for Fe3+ based on a Receptor Composed of Tri-oxygen Atoms of Amide Groups in Water

- Sonocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in aqueous solution using Fe-doped TiO2 nanoparticles under mechanical agitation

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Production and Analysis of Recycled Ammonium Perrhenate from CMSX-4 superalloys

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- New phosphorus biofertilizers from renewable raw materials in the aspect of cadmium and lead contents in soil and plants

- Survey of content of cadmium, calcium, chromium, copper, iron, lead, magnesium, manganese, mercury, sodium and zinc in chamomile and green tea leaves by electrothermal or flame atomizer atomic absorption spectrometry

- Biogas digestate – benefits and risks for soil fertility and crop quality – an evaluation of grain maize response

- A numerical analysis of heat transfer in a cross-current heat exchanger with controlled and newly designed air flows

- Freshwater green macroalgae as a biosorbent of Cr(III) ions

- The main influencing factors of soil mechanical characteristics of the gravity erosion environment in the dry-hot valley of Jinsha river

- Free amino acids in Viola tricolor in relation to different habitat conditions

- The influence of filler amount on selected properties of new experimental resin dental composite

- Effect of poultry wastewater irrigation on nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon contents in farmland soil

- Response of spring wheat to NPK and S fertilization. The content and uptake of macronutrients and the value of ionic ratios

- The Effect of Macroalgal Extracts and Near Infrared Radiation on Germination of Soybean Seedlings: Preliminary Research Results

- Content of Zn, Cd and Pb in purple moor-grass in soils heavily contaminated with heavy metals around a zinc and lead ore tailing landfill

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Synthesis of (±)-3,4-dimethoxybenzyl-4-methyloctanoate as a novel internal standard for capsinoid determination by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS(QTOF)

- Repellent activity of monoterpenoid esters with neurotransmitter amino acids against yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti

- Effect of Flammulina velutipes (golden needle mushroom, eno-kitake) polysaccharides on constipation

- Bioassay-directed fractionation of a blood coagulation factor Xa inhibitor, betulinic acid from Lycopus lucidus

- Antifungal and repellent activities of the essential oils from three aromatic herbs from western Himalaya

- Chemical composition and microbiological evaluation of essential oil from Hyssopus officinalis L. with white and pink flowers

- Bioassay-guided isolation and identification of Aedes aegypti larvicidal and biting deterrent compounds from Veratrum lobelianum

- α-Terpineol, a natural monoterpene: A review of its biological properties

- Utility of essential oils for development of host-based lures for Xyleborus glabratus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae), vector of laurel wilt

- Phenolic composition and antioxidant potential of different organs of Kazakh Crataegus almaatensis Pojark: A comparison with the European Crataegus oxyacantha L. flowers

- Isolation of eudesmane type sesquiterpene ketone from Prangos heyniae H.Duman & M.F.Watson essential oil and mosquitocidal activity of the essential oils

- Comparative analysis of the polyphenols profiles and the antioxidant and cytotoxicity properties of various blue honeysuckle varieties

- Special Issue on ICCESEN 2017

- Modelling world energy security data from multinomial distribution by generalized linear model under different cumulative link functions

- Pine Cone and Boron Compounds Effect as Reinforcement on Mechanical and Flammability Properties of Polyester Composites

- Artificial Neural Network Modelling for Prediction of SNR Effected by Probe Properties on Ultrasonic Inspection of Austenitic Stainless Steel Weldments

- Calculation and 3D analyses of ERR in the band crack front contained in a rectangular plate made of multilayered material

- Improvement of fuel properties of biodiesel with bioadditive ethyl levulinate

- Properties of AlSi9Cu3 metal matrix micro and nano composites produced via stir casting

- Investigation of Antibacterial Properties of Ag Doped TiO2 Nanofibers Prepared by Electrospinning Process

- Modeling of Total Phenolic contents in Various Tea samples by Experimental Design Methods

- Nickel doping effect on the structural and optical properties of indium sulfide thin films by SILAR

- The effect mechanism of Ginnalin A as a homeopathic agent on various cancer cell lines

- Excitation functions of proton induced reactions of some radioisotopes used in medicine

- Oxide ionic conductivity and microstructures of Pr and Sm co-doped CeO2-based systems

- Rapid Synthesis of Metallic Reinforced in Situ Intermetallic Composites in Ti-Al-Nb System via Resistive Sintering

- Oxidation Behavior of NiCr/YSZ Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs)

- Clustering Analysis of Normal Strength Concretes Produced with Different Aggregate Types

- Magnetic Nano-Sized Solid Acid Catalyst Bearing Sulfonic Acid Groups for Biodiesel Synthesis

- The biological activities of Arabis alpina L. subsp. brevifolia (DC.) Cullen against food pathogens

- Humidity properties of Schiff base polymers

- Free Vibration Analysis of Fiber Metal Laminated Straight Beam

- Comparative study of in vitro antioxidant, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase activity of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) collected during different growth stages

- Isothermal Oxidation Behavior of Gadolinium Zirconate (Gd2Zr2O7) Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs) produced by Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition (EB-PVD) technique

- Optimization of Adsorption Parameters for Ultra-Fine Calcite Using a Box-Behnken Experimental Design

- The Microstructural Investigation of Vermiculite-Infiltrated Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition Thermal Barrier Coatings

- Modelling Porosity Permeability of Ceramic Tiles using Fuzzy Taguchi Method

- Experimental and theoretical study of a novel naphthoquinone Schiff base

- Physicochemical properties of heat treated sille stone for ceramic industry

- Sand Dune Characterization for Preparing Metallurgical Grade Silicon

- Catalytic Applications of Large Pore Sulfonic Acid-Functionalized SBA-15 Mesoporous Silica for Esterification

- One-photon Absorption Characterizations, Dipole Polarizabilities and Second Hyperpolarizabilities of Chlorophyll a and Crocin

- The Optical and Crystallite Characterization of Bilayer TiO2 Films Coated on Different ITO layers

- Topical Issue on Bond Activation

- Metal-mediated reactions towards the synthesis of a novel deaminolysed bisurea, dicarbamolyamine

- The structure of ortho-(trifluoromethyl)phenol in comparison to its homologues – A combined experimental and theoretical study

- Heterogeneous catalysis with encapsulated haem and other synthetic porphyrins: Harnessing the power of porphyrins for oxidation reactions

- Recent Advances on Mechanistic Studies on C–H Activation Catalyzed by Base Metals

- Reactions of the organoplatinum complex [Pt(cod) (neoSi)Cl] (neoSi = trimethylsilylmethyl) with the non-coordinating anions SbF6– and BPh4–

- Erratum

- Investigation on Two Compounds of O, O’-dithiophosphate Derivatives as Corrosion Inhibitors for Q235 Steel in Hydrochloric Acid Solution

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- The effect of CuO modification for a TiO2 nanotube confined CeO2 catalyst on the catalytic combustion of butane

- The preparation and antibacterial activity of cellulose/ZnO composite: a review

- Linde Type A and nano magnetite/NaA zeolites: cytotoxicity and doxorubicin loading efficiency

- Performance and thermal decomposition analysis of foaming agent NPL-10 for use in heavy oil recovery by steam injection

- Spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, UV, 1H and 13C NMR) insights, electronic profiling and DFT computations on ({(E)-[3-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-1-phenylpropylidene] amino}oxy)(4-nitrophenyl)methanone, an imidazole-bearing anti-Candida agent

- A Simplistic Preliminary Assessment of Ginstling-Brounstein Model for Solid Spherical Particles in the Context of a Diffusion-Controlled Synthesis

- M-Polynomials And Topological Indices Of Zigzag And Rhombic Benzenoid Systems

- Photochemical Transformation of some 3-benzyloxy-2-(benzo[b]thiophen-2-yl)-4Hchromen-4-ones: A Remote Substituent Effect

- Dynamic Changes of Secondary Metabolites and Antioxidant Activity of Ligustrum lucidum During Fruit Growth

- Studies on the flammability of polypropylene/ammonium polyphosphate and montmorillonite by using the cone calorimeter test

- DSC, FT-IR, NIR, NIR-PCA and NIR-ANOVA for determination of chemical stability of diuretic drugs: impact of excipients

- Antioxidant and Hepatoprotective Effects of Methanolic Extracts of Zilla spinosa and Hammada elegans Against Carbon Tetrachlorideinduced Hepatotoxicity in Rats

- Prunus cerasifera Ehrh. fabricated ZnO nano falcates and its photocatalytic and dose dependent in vitro bio-activity

- Organic biocides hosted in layered double hydroxides: enhancing antimicrobial activity

- Experimental study on the regulation of the cholinergic pathway in renal macrophages by microRNA-132 to alleviate inflammatory response

- Synthesis, characterization, in-vitro antimicrobial properties, molecular docking and DFT studies of 3-{(E)-[(4,6-dimethylpyrimidin-2-yl)imino]methyl} naphthalen-2-ol and Heteroleptic Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Zn(II) complexes

- M-Polynomials and Topological Indices of Dominating David Derived Networks

- Human Health Risk Assessment of Trace Metals in Surface Water Due to Leachate from the Municipal Dumpsite by Pollution Index: A Case Study from Ndawuse River, Abuja, Nigeria

- Analysis of Bowel Diseases from Blood Serum by Autofluorescence and Atomic Force Microscopy Techniques

- Hydrographic parameters and distribution of dissolved Cu, Ni, Zn and nutrients near Jeddah desalination plant

- Relationships between diatoms and environmental variables in industrial water biotopes of Trzuskawica S.A. (Poland)

- Optimum Conversion of Major Ginsenoside Rb1 to Minor Ginsenoside Rg3(S) by Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Acid Hydrolysis Treatment

- Antioxidant, Anti-microbial Properties and Chemical Composition of Cumin Essential Oils Extracted by Three Methods

- Regulatory mechanism of ulinastatin on autophagy of macrophages and renal tubular epithelial cells

- Investigation of the sustained-release mechanism of hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose skeleton type Acipimox tablets

- Bio-accumulation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Grey Mangrove (Avicennia marina) along Arabian Gulf, Saudi Coast

- Dynamic Change of Secondary Metabolites and spectrum-effect relationship of Malus halliana Koehne flowers during blooming

- Lipids constituents from Gardenia aqualla Stapf & Hutch

- Effect of using microwaves for catalysts preparation on the catalytic acetalization of glycerol with furfural to obtain fuel additives

- Effect of Humic Acid on the Degradation of Methylene Blue by Peroxymonosulfate

- Serum containing drugs of Gua Lou Xie Bai decoction (GLXB-D) can inhibit TGF-β1-Induced Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in A549 Cells

- Antiulcer Activity of Different Extracts of Anvillea garcinii and Isolation of Two New Secondary Metabolites

- Analysis of Metabolites in Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz Dry Red Wines from Shanxi by 1H NMR Spectroscopy Combined with Pattern Recognition Analysis

- Can water temperature impact litter decomposition under pollution of copper and zinc mixture

- Released from ZrO2/SiO2 coating resveratrol inhibits senescence and oxidative stress of human adipose-derived stem cells (ASC)

- Validated thin-layer chromatographic method for alternative and simultaneous determination of two anti-gout agents in their fixed dose combinations

- Fast removal of pollutants from vehicle emissions during cold-start stage

- Review Article

- Catalytic activities of heterogeneous catalysts obtained by copolymerization of metal-containing 2-(acetoacetoxy)ethyl methacrylate

- Antibiotic Residue in the Aquatic Environment: Status in Africa

- Regular Articles

- Mercury fractionation in gypsum using temperature desorption and mass spectrometric detection

- Phytosynthetic Ag doped ZnO nanoparticles: Semiconducting green remediators

- Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Induced by SMAD4 Activation in Invasive Growth Hormone-Secreting Adenomas

- Physicochemical properties of stabilized sewage sludge admixtures by modified steel slag

- In Vitro Cytotoxic and Antiproliferative Activity of Cydonia oblonga flower petals, leaf and fruit pellet ethanolic extracts. Docking simulation of the active flavonoids on anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2

- Synthesis and Characterization of Pd exchanged MMT Clay for Mizoroki-Heck Reaction

- A new selective, and sensitive method for the determination of lixivaptan, a vasopressin 2 (V2)-receptor antagonist, in mouse plasma and its application in a pharmacokinetic study

- Anti-EGFL7 antibodies inhibit rat prolactinoma MMQ cells proliferation and PRL secretion

- Density functional theory calculations, vibration spectral analysis and molecular docking of the antimicrobial agent 6-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-ylmethyl)-5-ethyl-2-{[2-(morpholin-4-yl)ethyl] sulfanyl}pyrimidin-4(3H)-one

- Effect of Nano Zeolite on the Transformation of Cadmium Speciation and Its Uptake by Tobacco in Cadmium-contaminated Soil

- Effects and Mechanisms of Jinniu Capsule on Methamphetamine-Induced Conditioned Place Preference in Rats

- Calculating the Degree-based Topological Indices of Dendrimers

- Efficient optimization and mineralization of UV absorbers: A comparative investigation with Fenton and UV/H2O2

- Metabolites of Tryptophane and Phenylalanine as Markers of Small Bowel Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

- Adsorption and determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water through the aggregation of graphene oxide

- The role of NR2C2 in the prolactinomas

- Chromium removal from industrial wastewater using Phyllostachys pubescens biomass loaded Cu-S nanospheres

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Preparation of Calcium Fluoride using Phosphogypsum by Orthogonal Experiment

- The mechanism of antibacterial activity of corylifolinin against three clinical bacteria from Psoralen corylifolia L

- 2-formyl-3,6-bis(hydroxymethyl)phenyl benzoate in Electrochemical Dry Cell

- Electro-photocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin using calcium titanate

- Effect of Malus halliana Koehne Polysaccharides on Functional Constipation

- Structural Properties and Nonlinear Optical Responses of Halogenated Compounds: A DFT Investigation on Molecular Modelling

- DMFDMA catalyzed synthesis of 2-((Dimethylamino)methylene)-3,4-dihydro-9-arylacridin-1(2H)-ones and their derivatives: in-vitro antifungal, antibacterial and antioxidant evaluations

- Production of Methanol as a Fuel Energy from CO2 Present in Polluted Seawater - A Photocatalytic Outlook

- Study of different extraction methods on finger print and fatty acid of raw beef fat using fourier transform infrared and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- Determination of trace fluoroquinolones in water solutions and in medicinal preparations by conventional and synchronous fluorescence spectrometry

- Extraction and determination of flavonoids in Carthamus tinctorius

- Therapeutic Application of Zinc and Vanadium Complexes against Diabetes Mellitus a Coronary Disease: A review

- Study of calcined eggshell as potential catalyst for biodiesel formation using used cooking oil

- Manganese oxalates - structure-based Insights

- Topological Indices of H-Naphtalenic Nanosheet

- Long-Term Dissolution of Glass Fibers in Water Described by Dissolving Cylinder Zero-Order Kinetic Model: Mass Loss and Radius Reduction

- Topological study of the para-line graphs of certain pentacene via topological indices

- A brief insight into the prediction of water vapor transmissibility in highly impermeable hybrid nanocomposites based on bromobutyl/epichlorohydrin rubber blends

- Comparative sulfite assay by voltammetry using Pt electrodes, photometry and titrimetry: Application to cider, vinegar and sugar analysis

- MicroRNA delivery mediated by PEGylated polyethylenimine for prostate cancer therapy

- Reversible Fluorescent Turn-on Sensors for Fe3+ based on a Receptor Composed of Tri-oxygen Atoms of Amide Groups in Water

- Sonocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in aqueous solution using Fe-doped TiO2 nanoparticles under mechanical agitation

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Production and Analysis of Recycled Ammonium Perrhenate from CMSX-4 superalloys

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- New phosphorus biofertilizers from renewable raw materials in the aspect of cadmium and lead contents in soil and plants

- Survey of content of cadmium, calcium, chromium, copper, iron, lead, magnesium, manganese, mercury, sodium and zinc in chamomile and green tea leaves by electrothermal or flame atomizer atomic absorption spectrometry

- Biogas digestate – benefits and risks for soil fertility and crop quality – an evaluation of grain maize response

- A numerical analysis of heat transfer in a cross-current heat exchanger with controlled and newly designed air flows

- Freshwater green macroalgae as a biosorbent of Cr(III) ions

- The main influencing factors of soil mechanical characteristics of the gravity erosion environment in the dry-hot valley of Jinsha river

- Free amino acids in Viola tricolor in relation to different habitat conditions

- The influence of filler amount on selected properties of new experimental resin dental composite

- Effect of poultry wastewater irrigation on nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon contents in farmland soil

- Response of spring wheat to NPK and S fertilization. The content and uptake of macronutrients and the value of ionic ratios

- The Effect of Macroalgal Extracts and Near Infrared Radiation on Germination of Soybean Seedlings: Preliminary Research Results

- Content of Zn, Cd and Pb in purple moor-grass in soils heavily contaminated with heavy metals around a zinc and lead ore tailing landfill

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Synthesis of (±)-3,4-dimethoxybenzyl-4-methyloctanoate as a novel internal standard for capsinoid determination by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS(QTOF)

- Repellent activity of monoterpenoid esters with neurotransmitter amino acids against yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti

- Effect of Flammulina velutipes (golden needle mushroom, eno-kitake) polysaccharides on constipation

- Bioassay-directed fractionation of a blood coagulation factor Xa inhibitor, betulinic acid from Lycopus lucidus

- Antifungal and repellent activities of the essential oils from three aromatic herbs from western Himalaya

- Chemical composition and microbiological evaluation of essential oil from Hyssopus officinalis L. with white and pink flowers

- Bioassay-guided isolation and identification of Aedes aegypti larvicidal and biting deterrent compounds from Veratrum lobelianum

- α-Terpineol, a natural monoterpene: A review of its biological properties

- Utility of essential oils for development of host-based lures for Xyleborus glabratus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae), vector of laurel wilt

- Phenolic composition and antioxidant potential of different organs of Kazakh Crataegus almaatensis Pojark: A comparison with the European Crataegus oxyacantha L. flowers

- Isolation of eudesmane type sesquiterpene ketone from Prangos heyniae H.Duman & M.F.Watson essential oil and mosquitocidal activity of the essential oils

- Comparative analysis of the polyphenols profiles and the antioxidant and cytotoxicity properties of various blue honeysuckle varieties

- Special Issue on ICCESEN 2017

- Modelling world energy security data from multinomial distribution by generalized linear model under different cumulative link functions

- Pine Cone and Boron Compounds Effect as Reinforcement on Mechanical and Flammability Properties of Polyester Composites

- Artificial Neural Network Modelling for Prediction of SNR Effected by Probe Properties on Ultrasonic Inspection of Austenitic Stainless Steel Weldments

- Calculation and 3D analyses of ERR in the band crack front contained in a rectangular plate made of multilayered material

- Improvement of fuel properties of biodiesel with bioadditive ethyl levulinate

- Properties of AlSi9Cu3 metal matrix micro and nano composites produced via stir casting

- Investigation of Antibacterial Properties of Ag Doped TiO2 Nanofibers Prepared by Electrospinning Process

- Modeling of Total Phenolic contents in Various Tea samples by Experimental Design Methods

- Nickel doping effect on the structural and optical properties of indium sulfide thin films by SILAR

- The effect mechanism of Ginnalin A as a homeopathic agent on various cancer cell lines

- Excitation functions of proton induced reactions of some radioisotopes used in medicine

- Oxide ionic conductivity and microstructures of Pr and Sm co-doped CeO2-based systems

- Rapid Synthesis of Metallic Reinforced in Situ Intermetallic Composites in Ti-Al-Nb System via Resistive Sintering

- Oxidation Behavior of NiCr/YSZ Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs)

- Clustering Analysis of Normal Strength Concretes Produced with Different Aggregate Types

- Magnetic Nano-Sized Solid Acid Catalyst Bearing Sulfonic Acid Groups for Biodiesel Synthesis

- The biological activities of Arabis alpina L. subsp. brevifolia (DC.) Cullen against food pathogens

- Humidity properties of Schiff base polymers

- Free Vibration Analysis of Fiber Metal Laminated Straight Beam

- Comparative study of in vitro antioxidant, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase activity of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) collected during different growth stages

- Isothermal Oxidation Behavior of Gadolinium Zirconate (Gd2Zr2O7) Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs) produced by Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition (EB-PVD) technique

- Optimization of Adsorption Parameters for Ultra-Fine Calcite Using a Box-Behnken Experimental Design

- The Microstructural Investigation of Vermiculite-Infiltrated Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition Thermal Barrier Coatings

- Modelling Porosity Permeability of Ceramic Tiles using Fuzzy Taguchi Method

- Experimental and theoretical study of a novel naphthoquinone Schiff base

- Physicochemical properties of heat treated sille stone for ceramic industry

- Sand Dune Characterization for Preparing Metallurgical Grade Silicon

- Catalytic Applications of Large Pore Sulfonic Acid-Functionalized SBA-15 Mesoporous Silica for Esterification

- One-photon Absorption Characterizations, Dipole Polarizabilities and Second Hyperpolarizabilities of Chlorophyll a and Crocin

- The Optical and Crystallite Characterization of Bilayer TiO2 Films Coated on Different ITO layers

- Topical Issue on Bond Activation

- Metal-mediated reactions towards the synthesis of a novel deaminolysed bisurea, dicarbamolyamine

- The structure of ortho-(trifluoromethyl)phenol in comparison to its homologues – A combined experimental and theoretical study

- Heterogeneous catalysis with encapsulated haem and other synthetic porphyrins: Harnessing the power of porphyrins for oxidation reactions

- Recent Advances on Mechanistic Studies on C–H Activation Catalyzed by Base Metals

- Reactions of the organoplatinum complex [Pt(cod) (neoSi)Cl] (neoSi = trimethylsilylmethyl) with the non-coordinating anions SbF6– and BPh4–

- Erratum

- Investigation on Two Compounds of O, O’-dithiophosphate Derivatives as Corrosion Inhibitors for Q235 Steel in Hydrochloric Acid Solution

![Scheme 3 Cleavage of C–N bonds in aniline derivatives on a ruthenium center [19,20].](/document/doi/10.1515/chem-2018-0058/asset/graphic/j_chem-2018-0058_fig_008.jpg)