Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

-

Mohit Vij

, Neha Dand

, Shahid Ud Din Wani

Abstract

Recently, microwave-based cyclodextrin nanosponges (CDNS) of domperidone (DOM) for their solubility and dissolution improvement have been studied. However, microwave-based CDNS for the dual-loading of cinnarizine (CIN) and DOM have not been documented. Therefore, this research concentrates explicitly on the concurrent loading of two drugs employing these nanocarriers, namely CIN and DOM, both categorized under Class II of the Biopharmaceutical Classification System. A green approach involving microwave synthesis was employed to fabricate these nanocarriers. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy confirmed the formation of CDNS, while scanning electron microscopy scans illustrated their porous nature. X-ray diffraction studies established the crystalline structure of the nanocarriers. Differential scanning calorimetry and FTIR analyses corroborated the drugs’ loading and subsequent amorphization. In vitro drug release studies demonstrated an enhanced solubility of the drugs, suggesting a potential improvement in their bioavailability. The in vivo pharmacokinetic investigation emphatically substantiated this hypothesis, revealing a 4.54- and 2.90-fold increase in the bioavailability of CIN and DOM, respectively. This enhancement was further supported by the results of the pharmacodynamic study utilizing the gastrointestinal distress/pica model, which indicated a significantly reduced consumption of kaolin. Conclusively, this study affirms the adaptability of microwave-based CDNS for the concurrent loading of multiple drugs, leading to improved solubility and bioavailability.

Graphical Abstract

1 Introduction

The simultaneous administration of two or more active substances in a single dosage form to enhance therapeutic response is termed combination drug therapy [1]. This approach is advantageous for achieving a synergistic effect improving patient compliance and reducing dosing frequency, especially in chronic conditions. Pathological complexities such as cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, pain management, and infectious diseases necessitate the use of combination drug therapy for effective treatment and management [2]. Motion sickness, nausea, and vertigo are all treated with the antihistaminic drug cinnarizine (CIN) [3,4]. As an antiemetic medication, domperidone (DOM) is frequently used to temporarily reduce nausea and vomiting [5,6]. Combining CIN and DOM is more beneficial than using either drug alone, according to clinical research on human subjects [7]. According to the Biopharmaceutical Classification System, both CIN and DOM medicines are classified as class II pharmaceuticals, meaning they have weak solubility and good permeability [8,9]. The co-administration of combined drugs in a single formulation can be facilitated by a variety of nanocarriers, such as liposomes, niosomes, organic or inorganic nanoparticles, polymeric or lipid nanoparticles, nanotubes, microemulsions, nanoemulsions, and surfactant or polymeric micelles [10,11]. Improved bioavailability, enhanced therapeutic efficacy, protection against degradation, a controlled release profile, and site-specific delivery of the pharmaceuticals under study are provided by these nanocarriers [11,12,13,14]. Nevertheless, despite ongoing advancements and impressive outcomes, the majority of the aforementioned nanocarrier types have a number of disadvantages that limit their effectiveness in combination therapy, including low drug entrapment efficiency, poor drug-loading, limited stability, potential toxicity of the nanocarrier components, and unintended side effects [11]. Recently, researchers have looked into combining drug complexation with cyclodextrins into various nanocarrier types as a potential way to get around the disadvantages of each individual nanocarrier and then increase their efficacy by combining their individual positive effects into a single nanocarrier [11,14]. Therefore, cyclodextrin nanosponges (CDNS) for dual-loaded drug delivery of CIN and DOM were selected in this study.

While native cyclodextrins have historically been successful in enhancing the solubility and stability of poorly soluble drugs, limitations such as the ability to load only one drug at a time and limited loading capacity have prompted researchers to seek solutions [15]. The emergence of cyclodextrin-based nanosponges as a carrier system addresses these challenges, offering the capability to load multiple lipophilic or hydrophilic drugs with superior capacity compared to native cyclodextrins. CDNS, polymerized derivatives of native cyclodextrins through cross-linking, possess biodegradable and non-toxic monomers, enjoying widespread regulatory acceptance in the pharmaceutical industry [16]. Previous studies on the encapsulation of various drugs like nicosulfuron [17], quercetin [18], resveratrol [19], and fisetin [20] have proven the merit of these nanocarriers in effective drug delivery.

Despite the theoretical advantages of loading multiple drugs within the same nanocarrier, few systems have explored this aspect of CDNS, likely due to the physical characteristics of these nanocarriers. Various synthetic approaches have been discussed in the literature, and the choice of method has been linked to the physicochemical properties of nanosponges. Two distinct forms of CDNS – amorphous and crystalline – have been identified, with preparation methods influencing their nature [21,22]. Traditional methods, such as fusion and solvent evaporation, were initially employed but faced challenges related to non-uniform reactions, large solvent requirements, low yield, and, more importantly, yielding nanosponges having an amorphous nature, which would lead to reduced drug loading [23]. To address these limitations, newer and more environmentally friendly techniques, such as microwave and ultrasonic-assisted synthesis, have gained attention. These methods seek to enhance the morphological, physical, and functional properties of nanosponges. The shift to these microwave-based approaches is driven by the need for straightforward, inexpensive, quick, and scalable procedures for the mass manufacturing of monodisperse, stable nanosponges with regulated size and shape [24]. Recently, we reported microwave-based CDNS of DOM for its solubility and dissolution improvement [25]. However, microwave-based CDNS for the combined therapy of CIN and DOM has not been documented. Therefore, the present research has focused on the microwave-mediated synthesis of crystalline CDNS, demonstrating their potential in complexing with poorly soluble model drugs – CIN and DOM. The goal is to enhance these drugs’ solubility, dissolution, and oral bioavailability while achieving a controlled release profile.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

CIN and DOM were graciously supplied as gift samples by Ankur Drugs and Pharma Ltd. (Baddi, India). β-Cyclodextrin (βCD) was generously provided by Roquette India Pvt., Ltd. (Mumbai, India). Diphenylcarbonate (DPC) and dimethylformamide (DMF) were procured from Sigma Aldrich (Mumbai, India). All additional chemicals and reagents utilized in this study were of analytical grade. Milli Q water (Millipore) was employed throughout the experimental procedures.

2.2 Synthesis of blank and dual drug-loaded CDNS

Using a fiber optic temperature sensor with an infrared camera and a magnetic stirring system, microwave reactions were conducted at 2,450 MHz in a scientific microwave system (Raga Tech, Bangalore, India). This integrated system proved to be useful in upholding and monitoring the reaction conditions required for the synthesis of nanosponge materials. The process involved the mixing of 100 mL of DMF with the monomer (βCD) and cross linker (DPC) in various molar ratios in a 250 mL flask before microwave irradiation. The solvent was extracted using a distillation procedure following a predetermined amount of time spent carrying out the reaction. To purify the final product after complete solvent removal, it was first washed with water and then extracted using a Soxhlet apparatus with ethanol for 4 h. The obtained formulation was optimized to get stable and insoluble blank nanosponges, which are referred to as microwave-nanosponges (MW-NS) [23]. Equimolar proportions of the drugs and the MW-NS were equilibrated under slow-stirring, centrifuged to remove uncomplexed drugs, and finally lyophilized using a lyophilizer (Bio gene, India) to obtain dual drug-loaded MW-NS.

2.3 Physicochemical characterization of dual drug-loaded MW-NS

2.3.1 Particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential

The average size, PDI, and zeta potential of dual drug-loaded MW-NS were assessed with a “Malvern® Zetasizer Nano ZS 90 (Malvern® Instruments Limited, Worcestershire, UK).” Each test sample was diluted 200 times with deionized water before three measurements were taken at a fixed scattering angle of 90° and a temperature of 25°C, respectively.

2.3.2 Drug loading and entrapment efficiency

To get rid of any leftover medication, 50 mg of dual drug-loaded MW-NS was thoroughly cleaned with methanol. To release the medication contained, they were sonicated for 15 min after being dried and further triturated with methanol. After filtering, the solutions were examined using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) at 270 nm and spectrophotometry at 254 and 287 nm [26]. Using standard formulae, the drug encapsulation efficiency was calculated.

2.3.3 Fourier transform infrared-attenuated total reflectance (FTIR-ATR) spectroscopy

The FTIR-3000B (Analytical Technologies Ltd., Mumbai, India) was used to produce FTIR-ATR spectra for both blank and dual drug-loaded MW-NS in the 4,000–600 cm−1 frequency range. To prevent contamination, each spectrum was recorded in a dry atmosphere with a sensitivity of 4 cm−1. The resulting average of over 100 repeats produced a satisfactory signal-to-noise ratio and reproducibility.

2.3.4 Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

A Hitachi, DSC 7020 calorimeter (Tokyo, Japan) was used for the DSC analysis. The heat of fusion and indium melting point were used to calibrate the device. Heating was done at a pace of 10°C per minute to reach temperatures between 35 and 300°C. An empty sample pan was used as a reference when sourcing aluminum sample pans. Five-milligram samples were examined in triplicate while under nitrogen purge.

2.3.5 X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD)

We used a Bruker diffractometer (D8 Advance, Coventry, UK) to conduct a comprehensive XRPD investigation to investigate the differential crystallinity behavioral patterns of blank MW-NS and dual drug-loaded MW-NS. The chosen specimens were photographed over a 2θ range across a 5–90° angle at a 40 kV voltage and 40 mA current utilizing copper wire as a radiation source.

2.3.6 Morphological studies

Using field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (JSM-7610F Plus, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan), the surface morphology of both blank and dual drug-loaded MW-NS was examined. The nanosponges were carelessly dispersed across a double-sided carbon adhesive tape. Then, to lessen the charging effects, those were hit on 300 Å gold-coated aluminum stubs, and photomicrographs were obtained at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV.

2.4 In vitro drug release and release kinetics

Using the USP dissolution tester apparatus II (Paddle type, Lab, India), release tests were conducted for plain medicines, dual drug-loaded MW-NS, and the physical mixing of the medications with βCD. At 37 ± 0.5°C, the temperature was maintained while the paddles rotated at 50 rpm. Dialysis bags were filled with amounts of pure CIN and DOM with and without βCD, as well as dual drug-loaded MW-NS equal to 20 mg of CIN and 15 mg of DOM. After being submerged in the release medium, the dialysis bags were fastened to a paddle. After the initial release tests were carried out in 900 mL of 0.1 N HCl (pH 1.2) for 2 h, the dialysis bag sample was transferred to a hemispherical dissolution container with 900 mL of pH 6.8 phosphate buffer for a further 22 h. Five-milliliter samples were removed after 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 24 h and replaced with an equivalent volume of the new drug-free medium. Spectrophotometric analysis was performed on the filtered samples at wavelengths of 254 and 287 nm. The average values of the three distinct release studies were displayed as the cumulative percentage of drugs released over time. Furthermore, release profiles between dual drug-loaded MW-NS and plain drug combinations were compared using the f 1 and f 2 values. Many kinetic models were used to analyze the drug release from dual drug-loaded MW-NS. The best model for determining the release mechanism was chosen [27] based on the coefficient of determination (R 2).

2.5 Pharmacokinetic studies

A single-dose, randomized block trial design was selected for this investigation. Male albino Wistar rats, around 6 weeks old and weighing 250–300 g, were used in this experiment. The Wistar rats were starved for 24 h before receiving treatment [28]. The study animals were divided into four groups, each consisting of six individuals. Group I, which was given an oral dose of the pure drug combination (CIN + DOM) suspension in distilled water, was regarded as the positive control group. Group II was regarded as a negative control group since it was given blank MW-NS in distilled water. The oral-marketed tablet containing the combination of DOM and CIN was given to the animals in Group III through oral gavage. The tablet was dissolved in distilled water and then taken orally. Group IV was given MW-NS which was dual drug-loaded. Group IV received the same dosage of DOM and CIN as a market tablet formulation plus a positive control.

Blood from each rat’s retro-orbital plexus vein was continuously collected at 1, 2, 3, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h intervals [29]. The time points for the blood collection were based on the time to reach the maximum plasma concentration (T max) of both drugs. The T max of CIN in healthy human volunteers after oral administration has been reported to be 1–3 h with a mean value of 2 h [30]. However, the average T max of DOM in healthy male volunteers after oral administration has been reported to be 1.2 h [31]. The reported T max values of CIN and DOM indicated that both drugs would reach their maximum plasma concentration (C max) values before 3 h of administration (absorption phase) [30,31]. After reaching C max, the elimination phase started. Therefore, initially, the blood sampling was carried out frequently (1, 2, and 3 h) after that it was delayed due to the start of the elimination phase (8, 12, 24, and 48 h). Heparinized containers were used to collect the blood samples, and red blood cells were whirled at 3,000 rpm for 30 min to enable them to settle. After being collected in tubes, the supernatant plasma was housed at −20°C before being assessed using the established HPLC technique [26]. The pharmacokinetic parameters following oral administration of different formulations were estimated for each rat in each group. The values of C max and T max were directly read from the plasma concentration–time profile curves. The values of area under curve from time 0–t (AUC0–48), area under curve from time0–∞ (AUC0–∞), clearance (Cl), volume of distribution (V d), elimination rate constant (K el), mean residence times (MRT), and elimination half-life (t 1/2) for CIN and DOM were derived from the plasma concentrations of CIN and DOM vs time plot using the non-compartmental method.

2.6 Pharmacodynamics study

Male albino Wistar rats ranging between 250 and 300 g were employed in the investigation. Prior to administration, the Wistar rats were fasted for 24 h. This pharmacodynamics study was carried out by using the rat emesis model. Using a brusque oral needle as an emetic inducer, an oral dosage of 40 mg·kg−1 of copper sulfate in distilled water was delivered to the rats intragastrically to measure their degree of pica [32]. The gram count of kaolin ingested by rats is used to measure pica [33]. A thick paste was made by blending 1:100 w/w of hydrated kaolin and acacia gum with distilled water. Kaolin pellets were made to imitate the normal food of rats kept in the lab. The pellets were allowed to air dry at room temperature.

Pica was constantly monitored for 48 h after receiving test materials (dual drug-loaded MW-NS in 1 mL of distilled water suspension) orally 10 min before emetic stimulation. The ingestion of these kaolin pellets within the first 24 and 48 h after the drug’s administration provided the pica data. To get the final number, the consumption of the dual drug-loaded MW-NS group was subtracted from the consumption of the control group.

2.7 HPLC analysis

The HPLC technique employed in the current investigation adheres to the methodology previously elucidated by Sirisha and Kumari [34]. Chromatographic isolation of the two pharmaceutical compounds was executed utilizing a C-18 column with dimensions of 250 mm × 4.6 mm i.d., and a particle size of 5 µm. The mobile phase, comprising a mixture of acetonitrile and methanol in a volumetric ratio of 30:70 v/v, was delivered at a flow rate of 1 mL·min−1. An autosampler facilitated the injection of 10 µL of the prepared solution, and the detection of the compounds was accomplished at a wavelength of 270 nm. Both the sample solutions and the mobile phase were degassed and filtered through a 0.45 µm membrane filter (Millipore, USA) before analysis.

2.8 Statistical analysis

With GraphPad Prism Software (version 9.4.1, San Diego, CA, USA), the statistical test was run. To compare the two groups, an independent t-test was run, and for multiple group comparisons, a post hoc Tukey’s test was run after the one-way analysis of variance. For results with a p-value of below 0.05, they were deemed statistically significant.

2.9 Ethical approval

The research related to animal use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations and institutional policies for the care and use of animals. The protocol was reviewed and approved for ethical conduct by the PBRI, Bhopal’s Institutional Animal Ethics Committee prior to the experiment’s execution. The study’s protocol number was PBRI/IAEC/29-03/010.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Synthesis of blank and dual drug-loaded nanosponges

Initially, conventional methods, such as fusion and solvent evaporation, were used to prepare CDNS. However, these methods produced non-uniform reactions, large amounts of solvent consumption, and low yield. The yield of CDNS using fusion and solvent evaporation methods was found to be 31.58% and 40.61%, respectively. However, the yield of CDNS using a microwave-based approach was recorded to be 77.80%. Microwave-based synthesis stands out as a highly advantageous method for crafting cyclodextrin-based nanosponges due to its unique features. This technique offers unparalleled efficiency and speed, significantly reducing reaction times compared to conventional methods [35]. The ability to precisely control reaction conditions under microwave irradiation ensures reproducibility and consistency in nanosponge preparation [36]. The rapid and uniform heating provided by microwaves enhances the overall yield of the synthesis process [37]. Additionally, the simplicity and ease of operation associated with microwave synthesis contribute to its appeal [38]. The method proves particularly beneficial for cyclodextrin-based nanosponges, as it facilitates the formation of well-defined, crystalline structures with desirable properties [39]. Overall, microwave synthesis emerges as a robust and time-efficient approach, holding promise for advancing the production of these innovative nanomaterials. Thus, it was opted to use microwave irradiation as a technique to synthesize these dual drug-loaded cyclodextrin-based nanosponges.

3.2 Particle size, PDI, and zeta potential

The zeta potential value for dual drug-loaded MW-NS was found to be −8.69 ± 0.36 mV, which was deemed adequate to prevent particle collisions caused by electric repulsion. The formulation’s particle size of 198.3 ± 1.7 nm confirmed its nano-size. The PDI value of 0.242 is commonly recognized as a moderately dispersed nature of nanocarriers [40].

3.3 Entrapment efficiency

The entrapment competence of dual drug-loaded MW-NS was 80.60 ± 1.56% for CIN and 79.00 ± 2.08% for DOM. Substantial encapsulation efficiencies within the formulation may plausibly stem from the incorporation of active components into the non-polar interstices inherent in the molecular arrangement of nanosponge entities. This behavior can also be explained by H-bond formation, which is made possible by the presence of H-atoms on the active species, or by interactions between aromatic rings and the protons connected to βCD that result in strong van der Waals forces [41,42]. As a result, the high entrapment efficiencies of CIN and DOM were possible due to the presence of βCD, which forms inclusion complexes with hydrophobic drugs like CIN and DOM [11]. This inclusion of complex formation could also maximize the drug-loading efficiencies for both drugs.

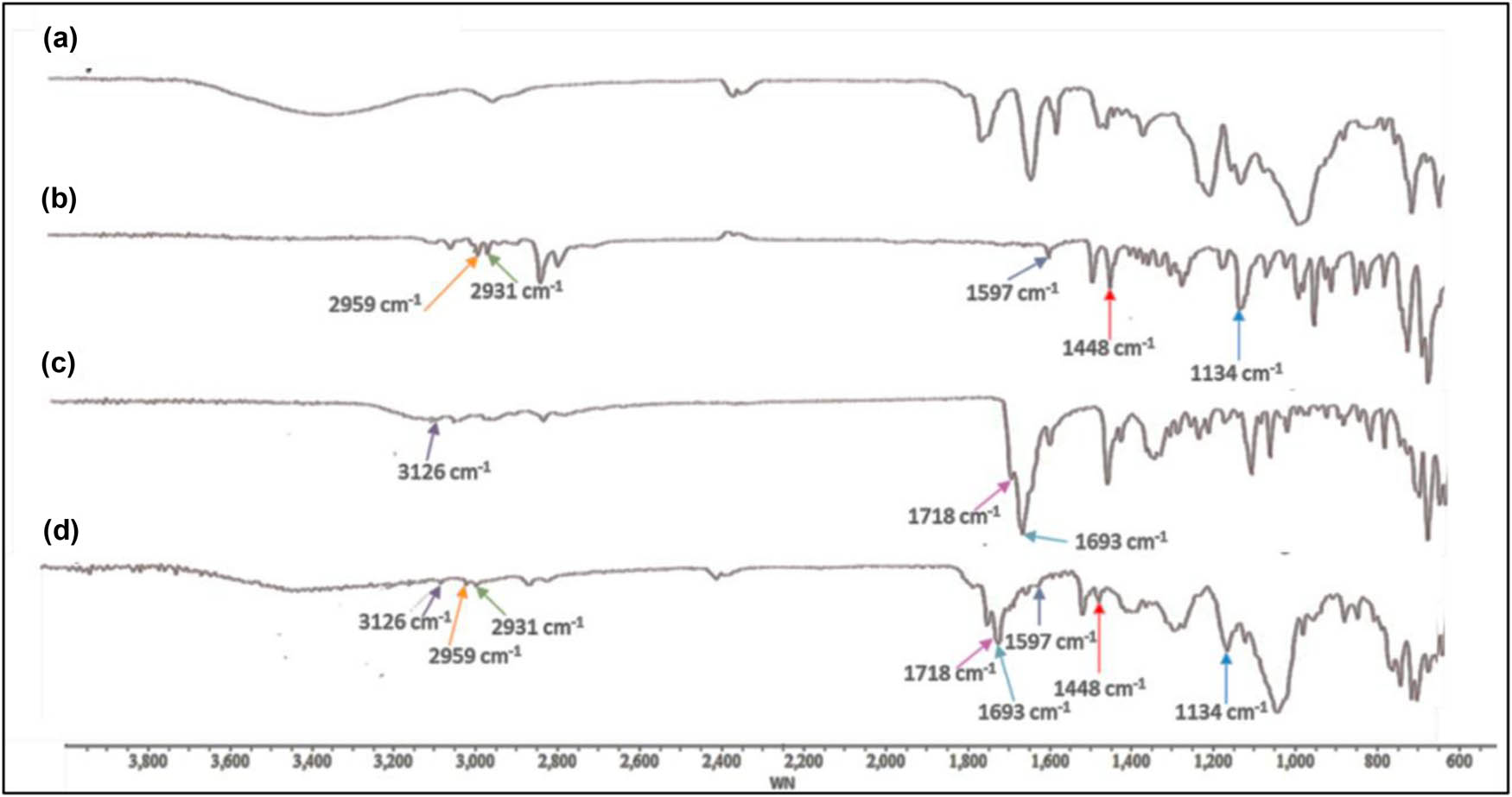

3.4 FTIR-ATR

FTIR-ATR was used to assess if the pharmaceutical substance could be encapsulated by the nanosponges. Figure 1 shows the FTIR spectra of the medicines, blank MW-NS, and dual drug-loaded MW-NS. Characteristic peaks for C–H stretching (aromatic, alkene, mono-substituted), C═C (aromatic stretch), –CH2 (alkane), and C–N stretching were shown by CIN at 2,959, 1,597, 1,490, 1,448, and 1,134 cm−1, respectively [43]. At the same time, DOM showed peaks at 3,126, 2,933, 1,718, and 1,693 cm−1, which were attributed to N–H bending, C═O stretching, asymmetric C–H stretching, and N–H stretching, respectively [44]. The cross-linking procedure is complete when the spectra of blank MW-NS do not show the typical non-hydrogen-bonded O–H stretching peak at 3,350 cm−1, which is attributed to the primary alcohol group in βCD. Additionally, the presence of a peak around 1,750 cm−1 is indicative of carbonate cross-linked MW-NS. These observations have been reported by previous researchers [45,46,47]. During the drug loading and encapsulation phases, characteristic drug peaks were anticipated to diminish, decrease in intensity, or exhibit a shift in wave number. In the spectrum of dual drug-loaded MW-NS, all prominent peaks associated with CIN and DOM appeared at markedly low intensity [29]. Notably, the distinctive peak at around 1,780 cm−1 and no peak at 3,350 cm−1 suggest the successful formation of nanosponges and the concurrent encapsulation of both drugs in combination.

FTIR spectra of (a) blank MW-NS, (b) plain CIN, (c) plain DOM, and (d) dual drug-loaded MW-NS.

3.5 DSC

The typical βCD peaks were detected between 316°C and 328°C, while the DPC (linker) peaks were seen between 72°C and 74°C (Figure 2). The absence of these peaks in the dual drug-loaded MW-NS suggested that the reaction had occurred and that the individual components were missing. It also emphasizes how well the post-synthesis cleaning mechanism worked. The peak temperatures of the medicines CIN and DOM are 118°C and 254°C, respectively. The presence of both peaks in the dual drug-loaded MW-NS suggests that there was no chemical reaction between the medicines (Figure 3). The drug peaks have decreased, suggesting that the drug was trapped in the generated nanosponges and that these nanosponges later amorphized [29,48].

DSC curves of βCD, DPC, and dual drug-loaded MW-NS.

DSC curves of CIN, DOM, and dual drug-loaded MW-NS.

3.6 XRPD

The XRPD analysis, as depicted in Figure 4a, substantiates the crystalline nature of βCD. In contrast, the XRD pattern of CDNS synthesized through conventional methods, as illustrated in Figure 4b, exhibited diffuseness devoid of discernible peaks, indicative of the amorphous configuration of the polymer. The XRD profile of blank MW-NS, presented in Figure 4c, manifested alterations in peak intensities along with a distinct peak pattern, suggesting the crystalline or para-crystalline characteristics of the resultant nanosponge [49].

XRPD spectra of (a) βCD, (b) blank nanosponges prepared by the melt method, and (c) blank nanosponges prepared by the microwave-based technique.

The XRPD patterns of CIN and DOM, as illustrated in Figure 5a and b, respectively, unequivocally verify their crystalline structures. The physical mixture’s XRD pattern is shown in Figure 5c as a composite representation that overlays the separate patterns of βCD, CIN, and DOM. Contrarily, the diffraction pattern of the dual drug-loaded MW-NS (Figure 5d) attests to its crystalline/para-crystalline nature, distinct from the individual patterns of CIN and DOM. This disparity implies the encapsulation of both drugs within the nanosponge, potentially resulting in their amorphization [16,50]. The amorphization of MW-NS indicated the changes in the physicochemical properties of CIN and DOM. This would result in enhanced solubility of CIN and DOM in nanosponges [11,26]. This improvement in solubility would ultimately result in improved drug release and overall bioavailability of CIN and DOM [11].

XPRD spectra of (a) CIN, (b) DOM, (c) physical mixture and βCD, and (d) dual drug-loaded loaded MW-NS.

3.7 Morphological evaluation

Through experiments using SEM, the shape of the particles was assessed. Figure 6a and b displays the SEM topography pictures of βCD and dual drug-loaded MW-NS, respectively. The crystalline character of βCD is illustrated by an SEM picture. Samples with the characteristic sponge-like conformation of βCD nanosponges were seen when βCD molecules were joined together with the use of a linker to produce nanosponges. A recent study reports that following lyophilization, nanosponges maintain their distinctive sponge-like shape. Our samples’ porosity might help with the enhanced loading and delivery of medications [51]. Other researchers have also reported a similar porous nature of these nanosponges as detected by SEM scanning [51,52].

SEM images of (a) βCD and (b) dual drug-loaded MW-NS.

3.8 In vitro drug release studies

Figures 7 and 8 show the drug release profiles of CIN and DOM, respectively. Table 1 lists the corresponding f 1 and f 2 values. The application of nanosponges, particularly those synthesized via microwave techniques, demonstrates a statistically significant enhancement in drug release profiles. Notably, nanosponges exhibit a remarkable 2- to 3-fold increase in the release of CIN compared to the plain drug and physical mixture counterparts, achieving a release ranging from 60% to 70% within 24 h (p < 0.05). Furthermore, for DOM, the nanosponge formulation results in a sustained release profile with a statistically significant difference in the cumulative release compared to the plain drug and physical mixture (p < 0.01). The initial release of DOM from nanosponges, albeit slightly lower at 30–40%, becomes highly significant as it surpasses 80% by the end of the 24-h period. The significant release profiles of CIN and DOM from nanosponges were possible due to the nanometer range particle size of dual drug-loaded nanosponges (198.3 nm) compared to plain drug and physical mixture. In addition, the improvement in the solubility and porosity of dual drug-loaded nanosponges could be the other reason for the significant release of CIN and DOM from nanosponges compared to the plain drugs and physical mixture. These statistically robust findings underscore the efficacy of nanosponges, especially those prepared innovatively, as a statistically significant and promising strategy for controlled and prolonged drug release, thus presenting a statistically justified avenue for potential therapeutic improvements.

In vitro release profile of CIN from drug mixture, physical mixture with βCD, and dual drug-loaded MW-NS.

In vitro release profile of DOM from drug mixture, physical mixture with βCD, and dual drug-loaded MW-NS.

In vitro drug release kinetics – model fitting

| Drug | Zero order (R 2) | First order (R 2) | Higuchi square root (R 2) | Korsmeyer-Peppas (R 2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIN | 0.8934 | 0.9612 | 0.8238 | 0.8451 |

| DOM | 0.9900 | 0.9715 | 0.9877 | 0.9781 |

The f 1 values were 83 for CIN from the dual drug-loaded MW-NS and 26 for DOM. The acceptable limit for f 1 is less than 15, indicating significant differences between release profiles. On the other hand, the f 2 values were 34 for CIN and 42 for DOM, which did not comply with the prescribed limit of f 2, which is 50–100 [53]. The calculated f 1 and f 2 values for nanosponges synthesized via the microwave method deviated significantly from the prescribed range, signifying substantial distinctions between the release profiles of the unaltered drug and the encapsulated nanosponges. This observation indicates a pronounced escalation in the quantity of released drugs from the nanosponges, a phenomenon observed for both CIN and DOM. Intriguingly, the dissimilarity in release profiles was notably more pronounced in the case of CIN compared to DOM within the dual-loaded nanosponges prepared through the microwave-based method.

The R² for CIN and DOM from dual drug-loaded MW-NS, modeled under various kinetic release profiles, exhibited distinct trends as shown in Table 1 [54]. The amount of medication left to be released from either nanosponge affects the release of CIN, according to the release kinetics studies. This allows for a predictable and sustained release of the drug, avoiding potential adverse effects associated with high initial burst releases. By following zero-order kinetics, the drug release from nanosponges demonstrated concentration-independent behavior in the case of DOM, as shown by the greatest values of R 2. This difference in the kinetic model for the drugs could be attributed to CIN’s higher aqueous solubility as compared to that of DOM [55,56], which suggests that it may readily dissolve and release from the βCD nanosponge, potentially exhibiting a first-order release profile.

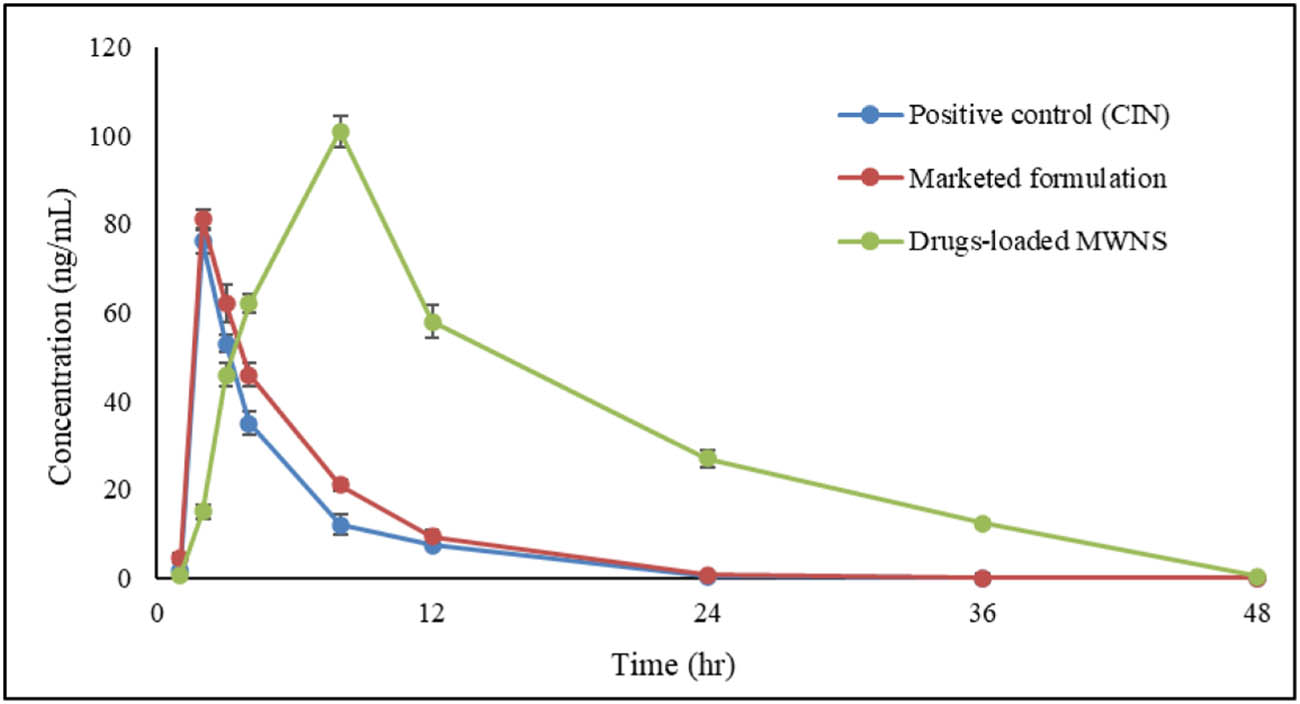

3.9 Pharmacokinetic evaluation

The plasma concentration–time profiles for both drugs are shown in Figures 9 and 10. To determine the pharmacokinetic parameters, Microsoft® Excel 2019’s PKSolver 2.0 add-in was utilized. The results are shown in Table 2.

Comparative plasma concentration–time profile curves for CIN.

Comparative plasma concentration–time profile curves for DOM.

Findings of pharmacokinetics evaluation of CIN and DOM

| PK parameter | Positive control | Marketed formulation | Dual drug-loaded MW-NS |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIN | |||

| t 1/2 (h) | 3.32 ± 0.36 | 3.32 ± 0.43 | 6.58 ± 0.45*,# |

| t max (h) | 2 ± 0 | 2 ± 0 | 4 ± 0 |

| C max (ng·mL−1) | 76 ± 3.18 | 81 ± 2.47 | 101 ± 2.55*,# |

| AUC0 to ∞ (ng·h·mL−1) | 331.79 ± 49.67 | 430.59 ± 51.9 | 1507.95 ± 121.63*,# |

| MRT (h) | 5.75 ± 0.54 | 6.05 ± 0.37 | 14.80 ± 0.89*,# |

| V d (L) | 7.41 ± 0.05 | 5.69 ± 0.07* | 3.22 ± 0.06*,# |

| Cl (ng·h·L−1) | 1.54 ± 0.02 | 1.19 ± 0.04* | 0.34 ± 0.02*,# |

| DOM | |||

| t 1/2 (h) | 6.44 ± 0.38 | 5.38 ± 0.50 | 5.95 ± 0.35* |

| t max (h) | 3 ± 0 | 3 ± 0 | 8 ± 0 |

| C max (ng·mL−1) | 49 ± 2.87 | 52 ± 3.75 | 71 ± 2.67*,# |

| AUC0 to ∞(ng·h·mL−1) | 578.99 ± 39.48 | 689.38 ± 45.75 | 1676.45 ± 109.56*,# |

| MRT (h) | 11.88 ± 0.88 | 12.53 ± 0.73 | 18.43 ± 0.59*,# |

| V d (L) | 6.17 ± 0.12 | 4.33 ± 0.08* | 1.97 ± 0.04* |

| Cl (ng·h·L−1) | 0.66 ± 0.02 | 0.56 ± 0.01* | 0.23 ± 0.02*,# |

*Significant (p < 0.001) compared to the pure drug (positive control).

#Significant (p < 0.001) compared to the commercial product.

Finally, dual drug-loaded MW-NS demonstrated CIN and DOM-regulated release patterns, which resulted in their absorption in vivo. There was a noticeable and significant difference in the bioavailability of the ordinary medicines and the nanosponges. When a commercial formulation or a simple drug suspension was administered, the absorption phase began quickly and abruptly, but when the dual drug-loaded MW-NS was administered, the absorption took longer to complete. The clearance of previously absorbed drugs and the delayed release of drugs from the nanosponges in vivo were responsible for the post-absorption phase that followed C max. The standard formulation exhibited swift absorption kinetics for both CIN and DOM, with mean t max values of 2.0 and 3.0 h, respectively. On the other hand, the mean t max for CIN and DOM in the dual drug-loaded MW-NS was 4.0 and 8.0 h, respectively. The controlled-release tablet facilitated sustained plasma concentrations in vivo, delaying peak plasma concentrations, as seen by the significantly longer MRT for both medicines. The reference formulation at the same dose (81 ± 2.47 ng·mL−1) was not as effective as the dual drug-loaded MW-NS, with a C max of CIN of 101 ± 2.55 ng·mL−1. As a result, in the first stage, the controlled release formulation successfully reduced drug release and subsequent absorption. The immediate release reference tablet and the controlled release dual drug-loaded MW-NS had mean t 1/2 of 3.32 ± 0.43 and 6.58 ± 0.45 h for CIN, respectively, and 5.95 ± 0.35 and 5.38 ± 0.50 h for DOM. The agreement in these values between the conventionally marketed tablet and the prolonged release MW-NS suggests that the elimination function, independent of dose form, predominantly influences the decreasing phase of the plasma concentration–time curve. Compared to CIN from the oral reference tablet, which had an AUC0–∞ of 430.59 ± 51.9 ng·h·mL−1, the controlled release of CIN from dual drug-loaded MW-NS had an AUC0–∞ of 1,507.95 ± 121.63 ng·h·mL−1. Comparably, the oral reference tablet produced 689.38 ± 45.75 ng·h·mL−1, whereas the controlled release of DOM from the MW-NS had an AUC0–∞ of 1,676.45 ± 109.56 ng·h·mL−1. As a result, the overall absorption of CIN from MW-NS was 4.54 times higher than that of its reference tablet, whereas the absorption of DOM was 2.90 times higher. This highlights the nanosponge formulation’s better bioavailability, which is attributed to its enhanced dissolving and sustained release properties. In summary, the pharmacokinetic evaluation suggests that the dual drug-loaded MW-NS significantly influence the absorption, distribution, and elimination of both CIN and DOM, exhibiting notable improvements in key parameters such as t 1/2, C max, AUC, MRT, V d, and Cl compared to the positive control and the marketed formulation. The possible reasons for the improvements in these parameters were nanometer size range, improved solubility, enhanced dissolution, and improvement in overall bioavailability of CIN and DOM in nanosponge formulation compared to the positive control and marketed formulation. These findings underscore the potential of MW-NS as a viable formulation strategy to modulate drug pharmacokinetics for enhanced therapeutic outcomes.

3.10 Pharmacodynamics study

A study conducted by Mitchell et al. elucidated that inducers of gastrointestinal distress in rats, such as toxic substances or motion, prompt the consumption of non-nutritive substances like kaolin (China clay), suggesting a correlation between pica behaviors in rats and vomiting in other species [57]. Various researchers have used this as a basis for their study to evaluate the effect on the vomiting behavior in rats [33,58,59]. Consistent with this knowledge, the effects of the dual drug-loaded MW-NS on the pica reflex were examined in a rat animal model, demonstrating a clear correlation with emesis in people. The review took into account notable elements linked to human pica, such as the release of 5-HT from enterochromaffin cells, elevated c-fos expression in the nucleus tractus solitarius, and delayed gastric emptying. The results of this study are tabulated in Table 3. The findings suggest that the dual drug-loaded MW-NS effectively mitigated the duration compared to both controls during the specified time periods. Importantly, the reduced consumption of kaolin in animals upon loading the drugs into nanosponges indicates diminished gastrointestinal distress/pica. The possible reasons for the reduced consumption of kaolin in animals treated with nanosponges could be due to the enhanced solubility, drug release, and overall bioavailability of CIN and DOM in nanosponges compared to the positive control, negative control, and marketed formulation. Furthermore, the statistically significant differences observed between the drugs-loaded MW-NS and the marketed formulation align with observations from pharmacokinetic studies, substantiating the potential of nanosponge formulations in modulating both behavioral and pharmacokinetic responses.

Consumption of kaolin (g) by rats of five distinct groups

| Duration | Positive control | Negative control | Marketed formulation | Dual drug-loaded MW-NS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 12.164 ± 1.478 | 17.391 ± 1.563 | 10.573 ± 1.496 | 3.440 ± 1.521* |

| 48 h | 13.452 ± 1.632 | 19.987 ± 1.732 | 12.115 ± 1.648 | 5.480 ± 1.746* |

*Significant difference (p < 0.001) when compared with positive control as well as the marketed formulation.

4 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study presents a comprehensive investigation into the development and application of microwave-synthesized dual-loaded CDNS for the enhanced solubility and bioavailability of CIN and DOM. The utilization of CDNS, particularly in a dual-drug loading scenario, offers a promising strategy for improving therapeutic outcomes. The microwave synthesis approach demonstrated in this research provides an environmentally friendly and efficient method for fabricating CDNS, overcoming challenges associated with traditional methods such as fusion and solvent evaporation. Physicochemical characterization confirmed the successful synthesis of dual drug-loaded nanosponges with desirable attributes, including nano-sized particles, moderately dispersed nature, and high entrapment efficiency. FTIR, DSC, and XRPD analyses supported the encapsulation of CIN and DOM within the nanosponges and their subsequent amorphization. Notably, in vitro drug release studies revealed a statistically significant enhancement in drug release profiles for both CIN and DOM when loaded into nanosponges compared to plain drug formulations. The controlled and sustained release profiles of the dual drug-loaded nanosponges, especially those synthesized via microwave methods, demonstrated their potential for prolonged therapeutic effects. Pharmacokinetic studies in Wistar rats further substantiated the superiority of the nanosponge formulation, exhibiting significantly improved bioavailability for both CIN and DOM compared to conventional formulations. The delayed absorption, prolonged mean residence time, and enhanced area under the plasma–time curve underscored the sustained release and dissolution-enhanced characteristics of the dual drug-loaded nanosponges. Moreover, the pharmacodynamic study using a rat emesis model provided additional evidence of the nanosponges’ efficacy in mitigating gastrointestinal distress, as indicated by the reduced consumption of kaolin pellets. The observed correlations between behavioral responses and pharmacokinetic parameters further emphasize the potential therapeutic benefits of the developed nanosponge formulation. Overall, this study demonstrates the adaptability of microwave-synthesized dual drug-loaded CDNS as a promising formulation strategy, offering improved solubility, controlled release, and enhanced bioavailability for co-administered drugs. The findings suggest a potential application of these nanosponges in addressing challenges associated with combination drug therapy, especially in conditions requiring synergistic effects and improved patient compliance. However, more clinical and toxicity studies are required to explore the commercial potential of developed dual drug-loaded CDNS.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2024R1040), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work.

-

Funding information: This work was funded by the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2024R1040), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contributions: MV: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, software, data curation writing original draft; ND: methodology, formal analysis, data curation, software; LK: formal analysis, data curation, validation; NC: investigation, validation, software; PK: data curation, formal analysis, software; PW: conceptualization, supervision, project administration, validation; SUDW: data curation, validation, software; FS: software; data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, validation, resources; MA: formal analysis, data curation, validation. Finally, all the authors have read, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Sun W, Sanderson P, Zheng W. Drug combination therapy increases successful drug repositioning. Drug Discov Today. 2016;21:1189–95.10.1016/j.drudis.2016.05.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Güvenç Paltun B, Kaski S, Mamitsuka H. Machine learning approaches for drug combination therapies. Brief Bioinform. 2021;22:bbab293.10.1093/bib/bbab293Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Shi S, Chen H, Lin X, Tang X. Pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution and safety of cinnarizine delivered in lipid emulsion. Int J Pharm. 2010;383:264–70.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.09.025Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Lucertini M, Mirante N, Casagrande M, Trivelloni P, Lugli V. The effect of cinnarizine and cocculus indicus on simulator sickness. Physiol Behav. 2007;91:180–90.10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.02.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Shazly GA, Alshehri S, Ibrahim MA, Tawfeek HM, Razik JA, Hassan YA, et al. Development of domperidone solid lipid nanoparticles: In vitro and in vivo characterization. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2018;19:1712–9.10.1208/s12249-018-0987-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Champion MC, Hartnett M, Yen M. Domperidone, a new dopamine antagonist. Can Med Assoc J. 1986;135:457–61.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Oosterveld WJ. The combined effect of cinnarizine and domperidone on vestibular susceptibility. Aviat Space Env Med. 1987;58:218–23.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Amidon GL, Lennernas H, Shah VP, Crison JR. A theoretical basis for a biopharmaceutic drug classification-the correlation of in-vitro drug product dissolution and in-vivo bioavailability. Pharm Res. 1995;12:413–20.10.1023/A:1016212804288Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Shakeel F, Kazi M, Alanazi FK, Alam P. Solubility of cinnarizine in (Transcutol + water) mixtures: Determination, Hansen solubility parameters, correlation, and thermodynamics. Molecules. 2021;26:E7052.10.3390/molecules26227052Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Mishra B, Patel BB, Tiwari S. Colloidal nanocarriers: A review on formulation technology, types and applications toward targeted drug delivery. Nanomedicine. 2010;6:9–24.10.1016/j.nano.2009.04.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Mura P. Advantages of the combined use of cyclodextrins and nanocarriers in drug delivery: A review. Int J Pharm. 2020;579:E119181.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119181Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Ud Din F, Aman W, Ullah I, Qureshi OS, Mustapha O, Shafique S, et al. Effective use of nanocarriers as drug delivery systems for the treatment of selected tumors. Int J Nanomed. 2017;12:7291–309.10.2147/IJN.S146315Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Patra JK, Das G, Fernandes LF, Campos EVR, Rodriguez-Torres MP, Acosta-Torres LS, et al. Nano based drug delivery systems: Recent developments and future prospects. J Nanobiotechnol. 2018;16:E71.10.1186/s12951-018-0392-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Saeedi M, Eslamifar M, Khezri K, Dizaj SM. Applications of nanotechnology in drug delivery to the central nervous system. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;111:666–75.10.1016/j.biopha.2018.12.133Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Kim DH, Lee SE, Pyo YC, Tran P, Park JS. Solubility enhancement and application of cyclodextrins in local drug delivery. J Pharm Investig. 2020;50:17–27.10.1007/s40005-019-00434-2Search in Google Scholar

[16] Utzeri G, Matias PMC, Murtinho D, Valente AJM. Cyclodextrin-based nanosponges: Overview and opportunities. Front Chem. 2022;10:E859406.10.3389/fchem.2022.859406Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Liu X, Li W, Xuan G. Preparation and characterization of β-cyclodextrin nanosponges and study on enhancing the solubility of insoluble nicosulfuron. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2020;774:E012108.10.1088/1757-899X/774/1/012108Search in Google Scholar

[18] Abou Taleb S, Moatasim Y, GabAllah M, Asfour MH. Quercitrin loaded cyclodextrin based nanosponge as a promising approach for management of lung cancer and COVID-19. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2022;77:E103921.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Dhakar NK, Caldera F, Bessone F, Cecone C, Pedrazzo AR, Cavalli R, et al. Evaluation of solubility enhancement, antioxidant activity, and cytotoxicity studies of kynurenic acid loaded cyclodextrin nanosponge. Carbohydr Polym. 2019;224:E115168.10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115168Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Aboushanab AR, El-Moslemany RM, El-Kamel AH, Mehanna RA, Bakr BA, Ashour AA. Targeted fisetin-encapsulated β-cyclodextrin nanosponges for breast cancer. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15:E1480.10.3390/pharmaceutics15051480Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Kumar S, Dalal P, Rao R. Cyclodextrin nanosponges: A promising approach for modulating drug delivery. In Colloid science in pharmaceutical nanotechnology. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2019.10.5772/intechopen.90365Search in Google Scholar

[22] Sherje AP, Dravyakar BR, Kadam D, Jadhav M. Cyclodextrin-based nanosponges: A critical review. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;173:37–49.10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.05.086Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Singireddy A, Rani Pedireddi S, Nimmagadda S, Subramanian S. Beneficial effects of microwave assisted heating versus conventional heating in synthesis of cyclodextrin based nanosponges. Mater Today Proc. 2016;3:3951–9.10.1016/j.matpr.2016.11.055Search in Google Scholar

[24] Sarabia-Vallejo Á, Caja MDM, Olives AI, Martín MA, Menéndez JC. Cyclodextrin inclusion complexes for improved drug bioavailability and activity: Synthetic and analytical aspects. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15:E2345.10.3390/pharmaceutics15092345Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Vij M, Dand N, Kumar L, Wadhwa P, Wani SUD, Mahdi WA, et al. Optimization of a greener-approach for the synthesis of cyclodextrin-based nanosponges for the solubility enhancement of domperidone, a BCS class II drug. Pharmaceuticals. 2023;16:E567.10.3390/ph16040567Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Vij M, Dand N, Kumar L, Ankalgi A, Wadhwa P, Alshehri S, et al. RP-HPLC-based bioanalytical approach for simultaneous quantitation of cinnarizine and domperidone in rat plasma. Separations. 2023;10:E159.10.3390/separations10030159Search in Google Scholar

[27] Anandam S, Selvamuthukumar S. Optimization of microwave-assisted synthesis of cyclodextrin nanosponges using response surface methodology. J Porous Mater. 2014;21:1015–23.10.1007/s10934-014-9851-2Search in Google Scholar

[28] Dinde M, Galgatte U, Shaikh F. Development and evaluation of cinnarizine loaded nanosponges: Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic study on Wistar rats. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2020;65:96–105.10.47583/ijpsrr.2020.v65i02.015Search in Google Scholar

[29] Omar SM, Ibrahim F, Ismail A. Formulation and evaluation of cyclodextrin-based nanosponges of griseofulvin as pediatric oral liquid dosage form for enhancing bioavailability and masking bitter taste. Saudi Pharm J. 2020;28:349–61.10.1016/j.jsps.2020.01.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Castañeda-Hernández G, Vargas-Alvarado Y, Aguirre F, Flores-Murrieta FJ. Pharmacokinetics of cinnarizine after single and multiple dosing in healthy volunteers. Arzneimittelforschung. 1993;43:539–42.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Helmy SA, El Bedaiwy HM. Pharmacokinetics and comparative bioavailability of domperidone suspension and tablet formulations in healthy adult subjects. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2013;3:126–31.10.1002/cpdd.43Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Yamamoto K, Matsunaga S, Matsui M, Takeda N, Yamatodani A. Pica in mice as a new model for the study of emesis. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2002;24:135–8.10.1358/mf.2002.24.3.802297Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Nakajima S. Pica caused by emetic drugs in laboratory rats with kaolin, gypsum, and lime as test substances. Physiol Behav. 2023;261:E114076.10.1016/j.physbeh.2023.114076Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Sirisha N, Kumari S. Validated RP-HPLC method for simultaneous estimation of cinnarizine and domperidone in bulk and pharmaceutical dosage form. J Pharm Sci Innov. 2013;2:46–50.10.7897/2277-4572.02218Search in Google Scholar

[35] Huang M, Xiong E, Wang Y, Hu M, Yue H, Tian T, et al. Fast microwave heating-based one-step synthesis of DNA and RNA modified gold nanoparticles. Nat Commun. 2022;13:968.10.1038/s41467-022-28627-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Hoz ADL, Alcázar J, Carrillo J, Herrero MA, Muñoz JDM, Prieto P, et al. Reproducibility and scalability of microwave-assisted reactions. In Microwave heating. London, UK: IntechOpen. 2011. 10.5772/19952.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Shah JJ, Mohanraj K. Comparison of conventional and microwave-assisted synthesis of benzotriazole derivatives. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2014;76:46–53.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Virlley S, Shukla S, Arora S, Shukla D, Nagdiya D, Bajaj T, et al. Recent advances in microwave-assisted nanocarrier based drug delivery system: Trends and technologies. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2023;87:E104842.10.1016/j.jddst.2023.104842Search in Google Scholar

[39] Guineo-Alvarado J, Quilaqueo M, Hermosilla J, González S, Medina C, Rolleri A, et al. Degree of crosslinking in β-cyclodextrin-based nanosponges and their effect on piperine encapsulation. Food Chem. 2021;340:E128132.10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128132Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Bhattacharjee S. DLS and zeta potential–What they are and what they are not? J Controlled Rel. 2016;235:337–51.10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.06.017Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Jawaharlal S, Subramanian S, Palanivel V, Devarajan G, Veerasamy V. Cyclodextrin-based nanosponges as promising carriers for active pharmaceutical ingredient. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2024;38:E23597.10.1002/jbt.23597Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Utzeri G, Cova TF, Murtinho D, Pais AACC, Valente AJM. Insights on macro- and microscopic interactions between confidor and cyclodextrin-based nanosponges. Chem Eng J. 2023;455:E140882.10.1016/j.cej.2022.140882Search in Google Scholar

[43] Abdelmonem R, Hamed RR, Abdelhalim SA, ElMiligi MF, El-Nabarawi MA. Formulation and characterization of cinnarizine targeted aural transfersomal gel for vertigo treatment: A pharmacokinetic study on rabbits. Int J Nanomed. 2020;15:6211–23.10.2147/IJN.S258764Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Zayed GM, Rasoul SAE, Ibrahim MA, Saddik MS, Alshora DH. In vitro and in vivo characterization of domperidone-loaded fast dissolving buccal films. Saudi Pharm J. 2020;28:266–73.10.1016/j.jsps.2020.01.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Kumar S, Prasad M, Rao R. Topical delivery of clobetasol propionate loaded nanosponge hydrogel for effective treatment of psoriasis: Formulation, physicochemical characterization, antipsoriatic potential and biochemical estimation. Mater Sci Eng C. 2021;119:E111605.10.1016/j.msec.2020.111605Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Mashaqbeh H, Obaidat R, Al-Shar’i N. Evaluation and characterization of curcumin-β-cyclodextrin and cyclodextrin-based nanosponge inclusion complexation. Polymers. 2021;13:E4073.10.3390/polym13234073Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Taleb SA, Moatasim Y, GabAllah M, Asfour MH. Quercitrin loaded cyclodextrin based nanosponge as a promising approach for management of lung cancer and COVID-19. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2022;77:E103921.10.1016/j.jddst.2022.103921Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Khan SA, Azam W, Ashames A, Fahelelbom KM, Ullah K, Mannan A, et al. β-cyclodextrin-based (IA-Co-AMPS) semi-IPNs as smart biomaterials for oral delivery of hydrophilic drugs: Synthesis, characterization, in-vitro and in-vivo evaluation. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2020;60:E101970.10.1016/j.jddst.2020.101970Search in Google Scholar

[49] Pawar S, Shende P. Dual drug delivery of cyclodextrin cross-linked artemether and lumefantrine nanosponges for synergistic action using 23 full factorial designs. Coll Surf A. 2020;602:E125049.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.125049Search in Google Scholar

[50] Caldera F, Tannous M, Cavalli R, Zanetti M, Trotta F. Evolution of cyclodextrin nanosponges. Int J Pharm. 2017;531:470–9.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.06.072Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Singh V, Xu J, Wu L, Liu B, Guo T, Guo Z, et al. Ordered and disordered cyclodextrin nanosponges with diverse physicochemical properties. RSC Adv. 2017;7:23759–64.10.1039/C7RA00584ASearch in Google Scholar

[52] Salazar S, Yutronic N, Kogan MJ, Jara P. Cyclodextrin nanosponges inclusion compounds associated with gold nanoparticles for potential application in the photothermal release of melphalan and cytoxan. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:E6446.10.3390/ijms22126446Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[53] Kassaye L, Genete G. Evaluation and comparison of in-vitro dissolution profiles for different brands of amoxicillin capsules. Afr Health Sci. 2013;13:369–75.10.4314/ahs.v13i2.25Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] Askarizadeh M, Esfandiari N, Honarvar B, Sajadian SA, Azdarpour A. Kinetic modeling to explain the release of medicine from drug delivery systems. ChemBioEng Rev. 2023;10:1006–49.10.1002/cben.202300027Search in Google Scholar

[55] Abdelrahman MM. Simultaneous determination of cinnarizine and domperidone by area under curve and dual wavelength spectrophotometric methods. Spectrochim Acta A. 2013;113:291–6.10.1016/j.saa.2013.04.120Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Tambawala TS, Shah PJ, Shah SA. Orally disintegrating tablets of cinnarizine and domperidone: A new arsenal for the management of motion sickness. J Pharm Sci Tech Mgmt. 2015;1:81–97.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Mitchell D, Laycock J, Stephens W. Motion sickness-induced pica in the rat. Am J Clin Nutr. 1977;30:147–50.10.1093/ajcn/30.2.147Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[58] Horn CC, De Jonghe BC, Matyas K, Norgren R. Chemotherapy-induced kaolin intake is increased by lesion of the lateral parabrachial nucleus of the rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297:R1375–82.10.1152/ajpregu.00284.2009Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[59] Nakajima S. Running-based pica and taste avoidance in rats. Learn Behav. 2018;46:182–97.10.3758/s13420-017-0301-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance