Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

-

Mikhlid H. Almutairi

, Madeeha Aslam

, Mika Sillanpää

Abstract

This groundbreaking study explores the eco-friendly production of titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) to investigate their impact on health. TiO2 NPs were synthesized utilizing a plant extract from Fagonia cretica, acting as both stabilizers and reducers. Various techniques, including energy dispersive X-ray (EDX), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), UV-Vis, and X-ray diffraction (XRD), were employed to analyze the synthesized TiO2 NPs. FT-IR revealed functional groups crucial for nanoparticle (NP) formation. SEM confirmed the particle size of synthesized TiO2 NPs, ranging from 20 to 80 nm. XRD analysis highlighted the rutile phase crystalline structure, and EDX determined the elemental composition of TiO2 NPs. These NPs displayed potent antimicrobial properties, proving toxic to bacterial and the fungal strains at 50 µg·mL−1 concentration. Impressively, TiO2 NPs showcased significant antidiabetic effects in adult male albino mice, effectively reducing Streptozotocin-induced hyperglycemia and hypercholesterolemia by the improvement in behavior via random blood glucose, triglyceride, low density lipoproteins, high density lipoprteins, very low density lipoproteins, and GTT pathway at 100 and 200 µL. Furthermore, they exhibited a remarkable impact on human liver cancer cell lines, with a 43.2% reduction in cell viability at 100 µg·mL−1 concentration. In essence, the study highlights TiO2 NPs as a safe, natural therapeutic agent with immense potential in diabetes treatment. The MTT assay was utilized to assess their cytotoxicity and biocompatibility, affirming their promising role in healthcare.

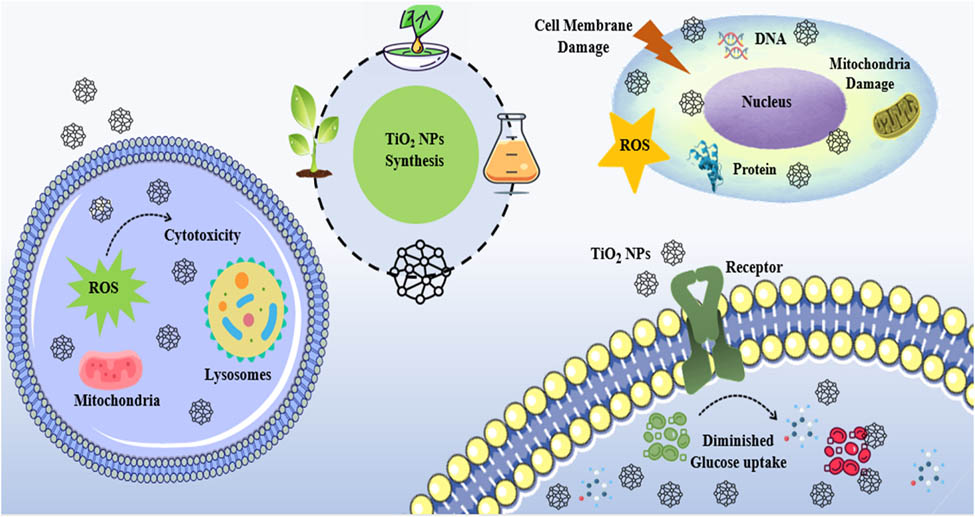

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Nanoparticles (NPs) are used in various fields due to their unique chemical and physical properties, such as pollution control, solar energy, agriculture, cosmetics, and electrochemical devices [1]. Among metallic NPs, TiO2 NPs are rare semiconducting transition metal oxide NPs with easy-to-manage, inexpensive, non-toxic, and fine resilience to minor erosion by chemicals. Researchers have discovered TiO2 NPs due to their exceptional (magnetic, electrical, and optical) properties, as well as the low cost synthesis when compared to other metals NPs such as Au, Ag, and Pt [2]. Numerous additional structural factors have been reported that influence the optical activities of TiO2 NPs, including phase composition, crystalline nature, band gap energy, morphology, size distribution, porosity, and particle size [3]. Interestingly, the optical properties of TiO2 NPs change from opaque to transparent in the visible region of the light spectrum when their size is reduced from 200 nm to less than 10 nm, developing unique UV light blockers [4]. Thus, the n-type pure semiconductor TiO2 NPs have a wide band gap energy such as 2.96 eV are for the brookite phase, 3.02 eV for the rutile phase, and 3.2 eV for the anatase phase. Moreover, it was reported that the rutile Fermi level is approximately 0.1 eV lower than the anatase level [5,6]. The band gap energy plays an important role in environments, because it significantly enhances the catalytic behavior in TiO2 NPs by generating a hole (h+) that contacts with water to form an OH radical, which effectively removes pollutants, pesticides, and heavy metals from wastewater through photo-oxidation [7]. Furthermore, the anatase phase of TiO2 NPs, with a smaller electron effective mass compared to rutile, enhances the mobility of its charge carriers, making it advantageous for optoelectronic device production [8]. TiO2 has 3d titanium orbitals in its conduction band and 2p oxygen orbitals in its valence band (VB), which combine to form hybrids with the 3d titanium orbitals [9]. Due to these remarkable properties, TiO2 NPs are used in a wide range of application, such as electrochemical cells, printing inks, gas sensing, plastics, antiseptic and antibacterial compositions, nanomedicine, cosmetics, and gas sensing [10,11]. TiO2 NPs have currently made significant contributions to the development of antimicrobial agents for treating pathogenic microorganisms. Nanoscale NPs have gained a lot of attention due to their exceptional efficacy and reactivity, making them most widely used antimicrobial agents. TiO2 NPs are being utilized as innovative and resource-efficient antibacterial and antifungal drugs to combat harmful microorganisms [12]. TiO2 NPs were typically synthesized using chemical, physical, and biological methods. The physical and chemical methods which required high temperatures, toxic substances, are expensive, and their exposure to the environment give rise to major ecotoxicological issues and limits their applications in different fields [13]. Therefore, green synthesis of TiO2 NPs has attracted considerable attention due to its significant advantages including cost effective, quick, environmental-friendly, and less toxic way to synthesize TiO2 NPs from biodegradable products. In recent years, plant-based methods have emerged as the most cost-effective, biocompatible, and environmentally friendly method for synthesizing NPs. Different plants extracts including, Solanum surattense [14], Aloe Barbadensis miller [15], and Vigna unguiculata [16] were used to synthesize TiO2 NPs by using an aqueous extract that was responsible for the stabilization and reduction.

The chronic hyperglycemia that is one of the main characteristic of diabetes mellitus is an irreversible disease brought on by abnormal protein, lipid, and carbohydrate metabolism [17]. The incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus is more severe compared to that of type 1 diabetes mellitus and gestational diabetes [18]. Type 2 diabetes mellitus affects 460 million people globally, with a 90% prevalence rate. According to statistics, this number will increase to more than 700 million in 25 years [19]. The autoimmune destruction of beta cells, which make insulin, is the possible cause of type 1 diabetes mellitus. It is one of the most prevalent illnesses in children, with an annual incidence rate ranging from 2% to 5%. Insulin resistance is linked to decreased glucose tolerance in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus [20]. Diabetes is treated with different pharmaceutical drugs, but plant-based therapies are frequently believed to be less harmful and to have no side effects. But a complex drug reagent reduces drug absorption, which reduces the bioavailability of a medication. Therefore, using medicinal plants may increase drug availability. It has been demonstrated that certain native plants impede the α-amylase enzyme [21]. Based on this, the current study investigates the antidiabetic property of green produced TiO2 NPs.

In Ayurvedic literature, there is no specific literature available on green synthesis of TiO2 NPs using an aqueous plant extract of Fagonia cretica. Thus, Fagonia cretica L. (family: Zygophyllaceae) is a short, erect, terete striates, spiny undershrub with slender branches and a glabrous or sparsely glandular puberulous growth that occurs almost all year primarily in north-west India [22]. The plant is used to treat thirst, diarrhea, asthma, vomiting, urinary discharges, fever, liver problems, stomach problems, typhoid, toothaches, dyslipidemia, and skin conditions. It has also been used as diuretic, astringent, smallpox, and bitter tonic preventive [23]. Numerous in vitro and in vivo investigations have provided an explanation for a broad range of pharmacological characteristics of crude plant extracts, including anticancer [24], analgesic, anti-microbial [25], immunomodulatory [26], and antioxidant [27]. The previous reports available on phytoconstituent present on plant extract of Fagonia cretica includes alkaloids, saponins, phenolics, flavonoids, and tannins [22,28]. These phytochemicals were responsible for the synthesis of titanium dioxide NPs and serve as stabilizing and reducing agents. Furthermore, different methods including energy dispersive X-ray analysis (EDX), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), X-ray diffractometer and UV-visible spectrophotometry have been used to investigate the geometry, morphological, elemental composition as well as optical properties of synthesized TiO2 NPs. In addition, the synthesized TiO2 NPs can be reproducible by choosing the whole plant that grows during the months of March and April, irrespective of the natural variability in the chemical content. Furthermore, it is also crucial to recognize that Fagonia cretica-mediated synthesis of TiO2 NPs can be highly reproducible for commercial applications. Moreover, the scientific and industrial research is an important step toward the commercialization of TiO2 NPs using plant extracts of Fagonia cretica. Fagonia cretica-based TiO2 NPs synthesis is also feasible for industrial applications in a bulk counterpart under optimized conditions. This method is simple, low cost, non-toxic, facile, and has shown its compatibility in various industrial and environmental applications without damaging the ecosystem. Hence, the Fagonia cretica-based TiO2 NPs are expected to be economically feasible as compared to conventional methods for large-scale production and commercialization. Therefore, the present study was used to examine the green synthesis of TiO2 NPs and explore their potential applications in biomedical fields, including antimicrobial, antidiabetic, and cytotoxic activity using MTT assay to determine biocompatibility for practical applications.

2 Materials and method

2.1 Preparation of plant extract

The plant was collected from Kohat development authority area of district Kohat. The plant was found scattered on the hilly area of the district. The plant was washed, and shade dried for about 2 weeks. After drying process, the whole plant of Fagonia cretica was powdered using a grinder. Then, 200 mL of distilled water were mixed with 20 g of powder Fagonia cretica and was heated at 40°C on a hot plate for 30 min. After that, the plant extract was cooled down and the extract was obtained via filtering using Whatman filter paper No.1. The extract was kept at 4°C for further synthesis of TiO2 NPs.

2.2 Green synthesis of TiO2 NPs

The synthesis of titanium dioxide NPs was obtained by mixing 10 mL of an aqueous plant extract into 70 mL solution of titanyl hydroxide (0.5 M) in a conical flask. After that, the flask was kept at 50°C temperature for 5 h. Then, the reaction mixture was continuously stirred in a rotatory orbital. The solution changed from light green to a white, brown color, indicating the synthesis of NPs. The phenolic group present in plant extract functions as a reducing agent that reduces the metal ions which was validated by changing the color of reaction mixture. Furthermore, UV-visible spectrophotometry was used to confirm the synthesis of TiO2 NPs. Subsequently, the reaction mixture was centrifuged for 20 min at 5,000 rpm in order to separate the NPs from its suspension form. The organic component was extracted after centrifugation, and the resultant pellet was cleaned with distilled water and methanol. The powdered form of the NPs was obtained for characterizations and other biological screening [29].

2.3 Characterization of TiO2 NPs

The NPs were examined using different characterization methods, including FT-IR, SEM, XRD, UV-Vis, and EDX analysis. These techniques were usually done to find out an average particle size, shape, morphology, crystallinity, and the optical properties of TiO2 NPs.

2.3.1 UV-Vis spectroscopy

The absorption spectra of UV-Vis analysis used for TiO2 NPs were chronicled at room temperature by UV-Vis (Shimadzu Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) spectrophotometer. The NPs sample was captured with a 1 nm resolution at 200 nm·min−1 over a 200–900 nm range.

2.3.2 FT-IR analysis

The FT-IR spectroscopy is a characterization method employed to achieved infrared spectra of NPs. The potential functional groups in the synthesized samples were also identified by using FT-IR spectroscopy, which records the FT-IR spectra at a resolution of 4 cm−1 in the range of 4,000 to 400 cm−1. These measurements were performed on KBr pellets in the diffuse reflectance mode using a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum-One instrument. The pellets were combined with KBr powder and pelletized after proper drying.

2.3.3 XRD analysis

The XRD pattern of the synthesized NPs has been used to analyze its structural characteristics, such as crystallinity and phase evaluation. X-ray diffraction was used to examine the synthesized NPs using a 9 kW anode rotating X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku X-ray diffractometer) with a diffraction angle ranging between 20° and 70° at scanning rate of 20·min−1.

2.3.4 SEM analysis

The TiO2 NPs were examined with SEM. The tiny sample size was spread out using air on carbon tape, then coated or sputtered using gold before being placed for examination. The sample, in small amounts, was sonicated for 10 min in dry ethanol to create a solution, which was then wetted onto the copper grid coated in holy carbon. After allowing the grid to dry under normal conditions, it was mounted for SEM analysis.

2.3.5 EDX

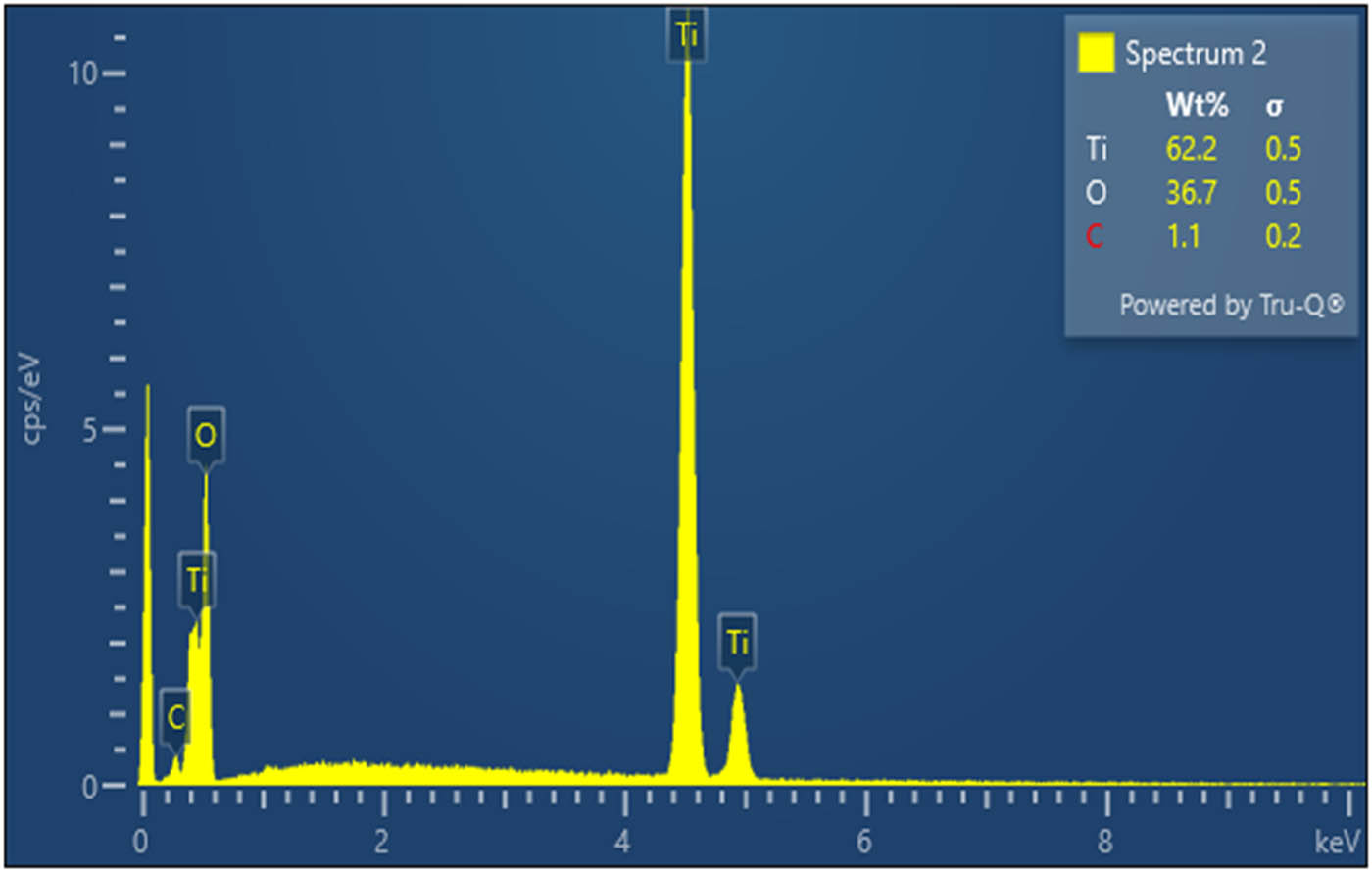

The elemental composition of TiO2 NPs was confirmed by the EDX using an accelerating voltage of 20 keV.

2.4 Antimicrobial activity

2.4.1 Antibacterial activity of TiO2 NPs

The antibacterial activity of the synthesized TiO2 NPs was assessed against bacterial strains of K. pneumoniae, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and E. coli. The disc diffusion technique was used to investigate the antibacterial activity of titanium dioxide NPs. The exponential bacterial cultures were seeded into Muller Hinton agar and impregnated using the sterile discs. After that, different concentrations of titanium dioxide NPs (10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 µg·mL−1) were loaded onto the discs, while an empty sterile disc acts as a control. The plates were incubated at room temperature for overnight with the impregnated discs remaining on the agar surface. The experiment was carried out in triplicate (n = 3) to calculate the formation of the clear zone inhibition [30].

2.4.2 Antifungal activity of TiO2 NPs

In this analysis, the sterilized petri plates were filled with the prepared potato dextrose agar (PDA). PDA plates were swabbed with the cultures of A. flavus, A. niger, C. albicans, and U. tritici. The separate sterile discs containing titanium dioxide NPs at concentrations of 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 µg·mL−1 were loaded and subsequently inverted onto the swabbed plate. A control group of sterile empty discs was used, and the plates were incubated at room temperature with the impregnated discs on the agar surface. The zones of inhibition on the plates were measured in triplicate (n = 3) after a 48 h incubation period [31].

2.5 Antidiabetic activity

2.5.1 Experimental animals and their grouping

Male adult albino mice aged 7–8 weeks were allocated into four groups (n = 5) randomly. The Veterinary Research Institute, located in Peshawar, Pakistan, purchased these mice and delivered them to the Neuro Molecular Medicines Research Centre (NMMRC, Peshawar). Mice were put into their appropriate cages one at a time (Biobased China). These Male adult albino mice were grouped as follows:

Control group

Streptozotocin (STZ) remedied mice (90 mg·kg−1)

STZ (90 mg·kg−1) + TiO2 NPs remedied mice (100 µL)

STZ (90 mg·kg−1) + TiO2 NPs mice treated (200 µL)

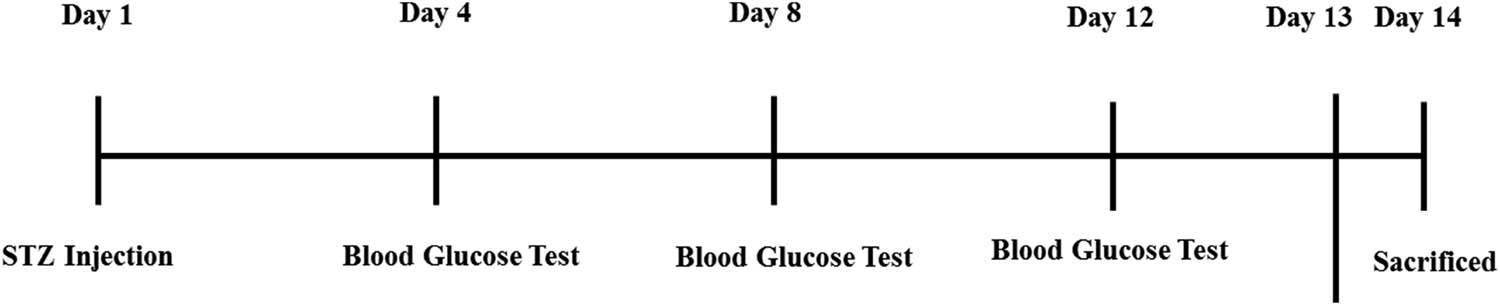

The breeding environment was set up with a 25°C temperature, a 12/12 h light/dark cycle, and unlimited access to food and water for the male mice (average body weight: 30–32 g). All animals were handled very carefully, according to the relevant animal ethics committee of the NMMRC, Peshawar. The blood sugar levels of the four separate experimental groups were randomly monitored on days 1, 4, 8, 12, 13, and 14 of the trial using a glucometer. Overall schedule has been displayed in Figure 1. This shows the injection details of STZ and random blood glucose tests sequence [32].

Injection details of STZ and random blood glucose test sequence.

2.5.2 STZ-induced diabetes mellitus and treatment with TiO2 NPs

In this analysis, the mice were randomly divided into four groups, the control animals were untreated, STZ group received a single injection of STZ (90 mg·kg−1), STZ plus TiO2 NPs group received STZ and TiO2 NPs (200 and 100 µL on alternate days) injections and TiO2 NPs group received only TiO2 NPs intraperitoneally. To show the therapeutic effects of NP on induced impairment of memory, the behavioral tests were executed where STZ and Vt. D were used that were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, USA. An injection of STZ was administered in the peritoneum cavity of mice at a dose of 60 mg·kg−1 of the body weight of mice in order to induce Diabetes mellitus in the animal. TiO2 NPs were given intraperitoneally at a dose of 100 mg·kg−1 of the body weight after 4 h of STZ injection, every other day, until the animals were sacrificed [33]. The first day of treatment was observed as soon as the hyperglycemic condition was confirmed. The intraperitoneal injections of TiO2NPs at a dose of 1.7 mg·kg−1 weight/day were given to each mouse in the group for a duration of 2 weeks, using a tuberculin syringe. After that, the blood glucose levels were randomly checked on day 1, 4, 8, 12, 13, and 14, respectively.

2.5.3 Glucose tolerance test (GTT)

The GTT was conducted after the titanium dioxide NPs treatment for 2 weeks in order to investigate the control effect of titanium dioxide NPs over glucose induced tolerance. The mice were allowed to fast for roughly 6–8 h, during which time blood was drawn from the tail vein tip to determine the blood glucose level during fasting. GTT was carried out by giving the fasted animals 1 g·kg−1 of glucose orally that was dissolved in 0.1 mL of clean water. The blood samples were obtained from the tail vein at different time intervals of 15, 30, 60, 120, and 180 min following the oral glucose load to estimate glucose. Potassium oxalate and sodium fluoride were added to the blood samples. After the drug course was completed, the animals were put to death, and blood was drawn for biochemical tests such as random blood glucose, triglyceride (TGL), low density lipoproteins (LDL), high density lipoprteins (HDL), Total cholesterol, very low density lipoproteins (VLDL), and GTT, among others. Blood glucose results were expressed as milligrams per deciliter (mg·dL−1) [34].

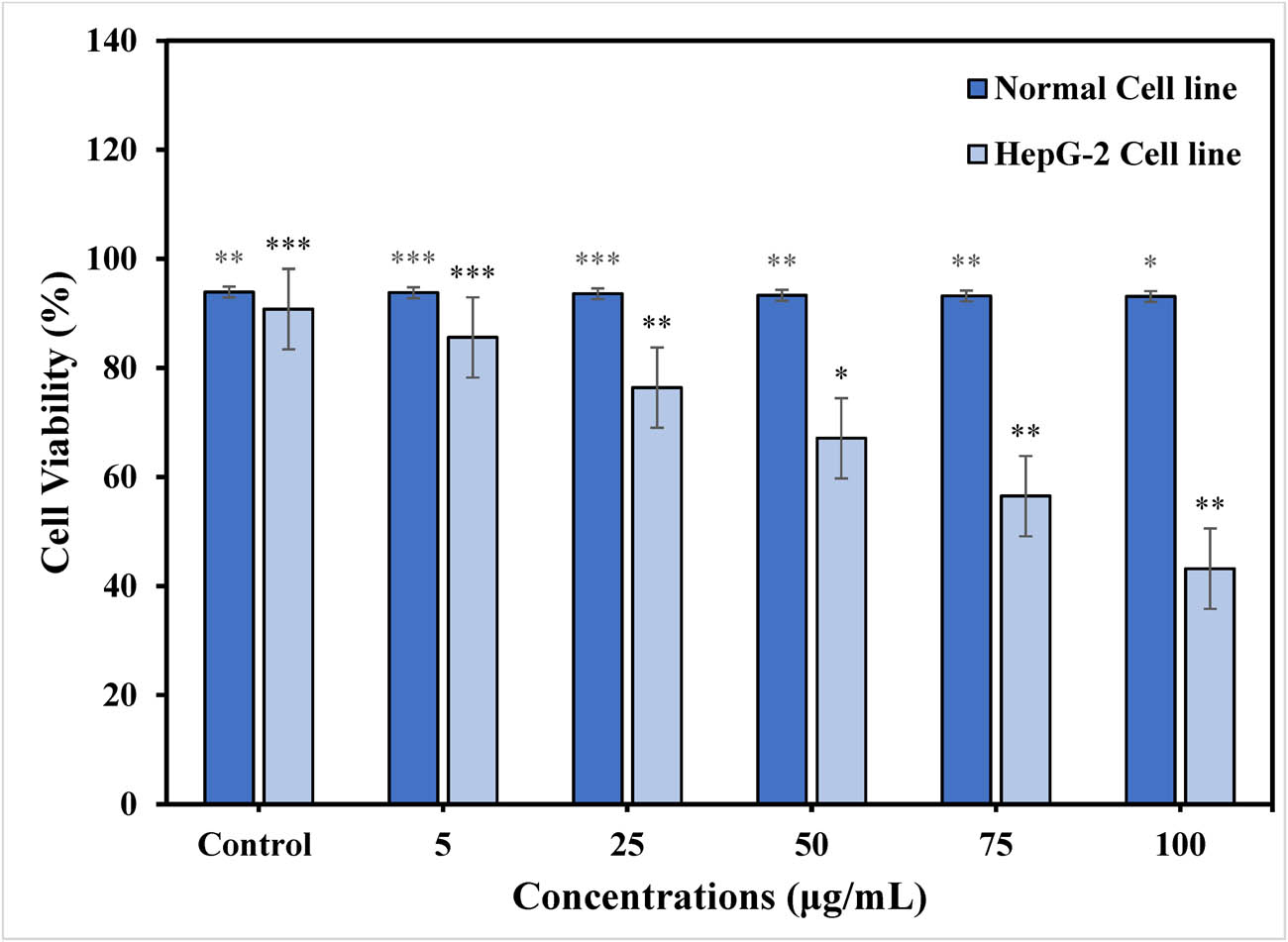

2.6 Cytotoxic activity of TiO2 NPs using human cancer cell lines

The cytotoxicity of the synthesized TiO2 NPs was analyzed against both HepG-2 human cancer cell lines and normal cell lines. In this analysis, cell lines (HepG-2) were cultivated separately, i.e., grown in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS. The cancer cells and normal cell lines were placed in 4 × 103 wells within 96-well sterile plates, respectively. After that, both the cell lines were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in an incubator with 5% CO2 at different concentrations of the tested TiO2 NPs (5, 25, 50, 75, and 100 μg·mL−1). The viability of the cell lines was measured after the incubation period [35]. After that, each well received 20 μL of 5 mg·mL−1 MTT (Sigma, USA), and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 3 h. The MTT solution was removed and 100 μL DMSO was put in after the TiO2 NPs were incubated for 72 h. The absorption value of each well was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader (BMG LabTech, Germany) to estimate the growth inhibition of cancer cells and normal cell line. The test was performed in triplicates (n = 3). Furthermore, Eq. 1 was used to assess the percentage of cell activity based on the optical density (OD) values.

where the cell viability is measured in (%), the optical density of the test group is represented by ODtreated, and the optical density of the control group is denoted by ODuntreated.

2.7 Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as mean values ± S.D. for each of the above techniques, which were performed in triplicate (n = 3). One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD analysis of variance with the significance of P < 0.05 were used in the statistical analysis, that was carried out with GraphPad Prism version 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

-

Ethical approval: The research related to animals’ use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations and institutional policies for the care and use of animals. The ethical approval for this study was obtained from KUST Ethical Committee Kohat University of Science and Technology, Kohat, Pakistan under Reference No. KUST/Ethical Committee/154 dated 02/08/2023.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 UV-visible analysis of TiO2 NPs

The current study revealed the reduction of the titanium ions by the Fagonia cretica plant extract, which led to the synthesis of TiO2 NPs. The UV-Vis spectral analysis was used for the confirmation analysis of TiO2 NP synthesis. The plant extract of Fagonia cretica did not show any noticeable color change in its aqueous form, and the synthesis of TiO2 NPs was not confirmed. A discernible color change was observed by mixing Fagonia cretica plant extract with titanium salt solution at 36°C temperature for 5 h of incubation period. This distinctive color shift was caused by the surface plasmon resonance being excited during the TiO2 NP synthesis. Thus, the results showed that the synthesis of TiO2 NPs was completed by the reduction of titanium ions which was further verified by UV-Vis spectrophotometer [36]. The UV-vis spectra of TiO2 NPs and plant extract were compared, revealing no visible peak in the plant extracts, as shown in Figure 2. However, the UV-Vis analysis demonstrates an absorption spectrum for the TiO2 NPs synthesis at around 307 nm when reduction was completed [30]. The characteristic absorption peak of synthesized TiO2 NPs was due to the light absorption properties of NPs which enhanced the photocatalytic activity with the help of stronger UV absorption intensity. The electrons in the VBs of TiO2 NPs are excited to conduction bands (CBs) upon exposure to UV light. The reaction causes the electrons to gain energy, which causes holes (h+) to form on the VBs. In this instance, the excited electrons (e−) are only in three-dimensional states due to their dissimilar parity, which reduces the probability of an e− transition as a result, the e−/h+ recombination occurs [37]. Accordingly, the rutile phase is an active photocatalytic component that are responsible for producing charge carriers (e− and h+) due to its band gap-corresponding ability to absorb UV light [8]. Eq. 2 was used to determine the optical band-gap(s) of the NPs.

where β is a constant, E g is the band gap of the NPs, h is the Planck’s constant and ν is the photon frequency, and α is the absorption coefficient (cm−1). The optical band gap energy was 4.04 eV that was revealed by the result of synthesized TiO2 NPs. Moreover, different factors (such as temperature, pH, and reaction time) were used for the optimum synthesis of TiO2 NPs. The synthesis TiO2 NPs were obtained by reacting with 10 mL of Fagonia cretica extract and 70 mL of 0.5 M titanyl hydroxide solution at room temperature and was monitored under UV-Vis spectroscopy. It was found that the intensity of absorption peaks of the synthesized NPs increases with the increase in the contact time of the reaction mixture, which became stronger and sharper after 5 h. In addition, the absorbance vs reaction time graph shows that the absorbance peaks increase more quickly for the first 2 h of the reaction time and then reach a high absorbance at the 5 h (Figure 2b). The optimum temperatures used to synthesize TiO2 NPs were achieved by ranging the temperature from 10 to 50°C. The observation of UV-Vis was carried out on the reaction mixture. The intensity of the absorption peaks increases from 30°C as the temperature of the reaction reached 50°C. So, the optimum temperature for TiO2 NPs was at 50°C, as shown in Figure 2c. Moreover, the reaction mixture was carried out at various pH levels in order to optimize the pH of the synthesized TiO2 NPs. The UV-Vis absorption peak at a wavelength of 307 nm, which increases in intensity with the increase in pH from 3 to 5, but decreases at pH between 7 and 9, confirmed the reaction used to synthesize TiO2 NPs. It was evident that the strong surface plasmon resonance peak of synthesized TiO2 NPs in acidic conditions was successfully obtained, indicating a rapid synthesis rate. Based on the results, it was determined that at pH = 3, the synthesized TiO2 NPs were mostly homogenous particles. However, if the pH of the reaction increases, a non-homogenous NP may be formed. The optimum synthesis of TiO2 NPs was obtained at pH 5 level, as illustrated in Figure 2d.

UV-Visible spectra of synthesized TiO2 NPs and plant extract (a), UV-visible absorption of TiO2 NPs at different time intervals (b), UV-visible absorption of TiO2 NPs at different reaction temperatures (c), and UV-visible absorption of TiO2 NPs observed at different pH level (d).

3.2 FT-IR analysis of TiO2 NPs

The FT-IR analysis was carried out to investigate the existence of biomolecules that cause the reduction of TiO2 NPs. FT-IR spectra of samples have been obtained using the KBr pelletization method, with an average resolution of 2 cm−1 and a wavenumber range from 4,000–400 cm−1. Figure 3 illustrates the FT-IR absorption band spectrum of an aqueous plant extract and TiO2 NPs at different positions. The broad band at 3,313 cm−1 related to O–H stretching vibration reveals the existence of polyphenolic functional groups. The broadness of band is due to the existence of intermolecular hydrogen-bond in the hydroxyl group of polyphenolic compounds. The absorption band at 1,644 cm−1 is associated with both symmetric (amide II) and asymmetric (amide I) N–H bending; the rise of these absorption bands is related to protein carbonyl stretching vibrations. The peak at 1,194 cm−1 corresponds to the C═C group of the aromatic rings. Similarly, the band observed at 866 cm−1 was due to C–H bending vibrations of aromatic compounds [30]. It was observed from the FT-IR spectra of green synthesized TiO2 NPs showed a prominent peak at 642 cm−1 which corresponds to the vibrational modes of Ti–O that was typically found in TiO2 NPs [38]. The shrinkage of the peak at 3,173 cm−1 (O–H stretching) of TiO2 NPs is due to the formation of a week intermolecular hydrogen bond between the polyphenolic groups. As a result, majority of the H-bonds connecting the O–H groups will be broken, causing a bathochromic shift, or a change in wavenumber and peak intensity of synthesized TiO2 NP, as shown in Figure 3 [39]. In contrast, the TiO2 NPs spectrum shows a bathochromic shift at 1,542 and 1,135 cm−1 and a decrease in peak intensity was due to the C═C group of aromatic rings and the N–H bending vibrations of amides observed in the FT-IR spectra of an aqueous extract that capped TiO2 NPs. The main difference between the two spectra in Figure 3 is the correct alteration of various peaks before and after the reduction of TiO2 NPs. Thus, the obtained results suggest that biomolecules like amino acids, glycosides, flavonoids, alkaloids, and tannins that are present in plant extract are responsible for the biotransformation of Ti ions into TiO2 NPs.

FT-IR spectrum of synthesized TiO2 NPs and aqueous plant extract Fagonia cretica.

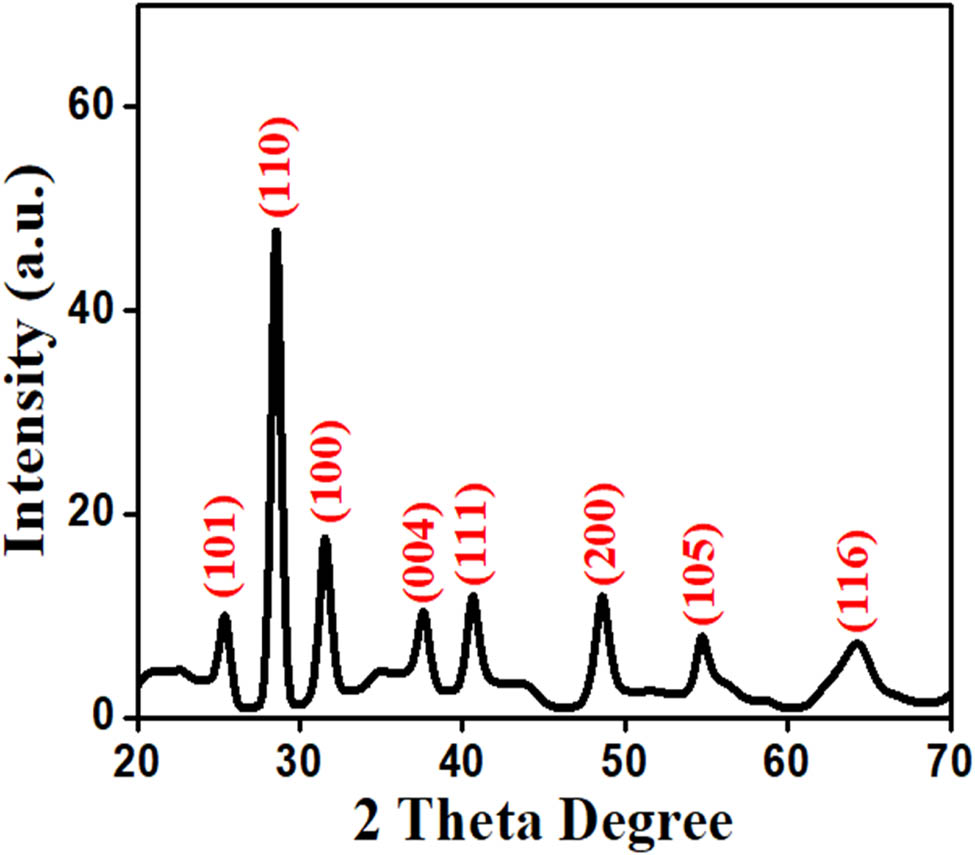

3.3 XRD pattern of TiO2 NPs

XRD was carried out to study the crystalline structure and the grain size of TiO2 NPs. XRD pattern was obtained at a scanning rate of 0.02·s−1 in a range of 20°–70° employing the Cu Ka radiation (wavelength = 1.54060 Å). The TiO2 NP XRD pattern is illustrated in Figure 4. The sharp strongest peak corresponding to the occurrence of a well-crystallized sample is observed in the results of XRD point. In the synthesized NPs, the Bragg’s reflection peaks were observed at 24.91°, 28.66°, 31.34°, 37.41°, 40.98°, 47.92°, 54.09°, and 64.32° at 2θ that corresponds to the reflection planes of (101), (110), (100), (004), (111), (200), (105), and (116), respectively. This could suggest that the NPs have a rutile phase by comparing the JCPDS data No. 46-1238 with the NP structure. Furthermore, the crystallite size for the synthesized TiO2 NPs was determined by using the Debye–Scherrer equation, D = Kλ/(β cos θ). where D is the crystallite size, λ is the Bragg’s angle, β is the full width half maximum (FWHM), and the wavelength of X-rays used is 1.5406 Å. The size of the crystallite was 11.92 nm and its strong peak intensity (FWHM) at (110) at peak angle was 28.66° [40].

XRD patterns of synthesized TiO2 NPs.

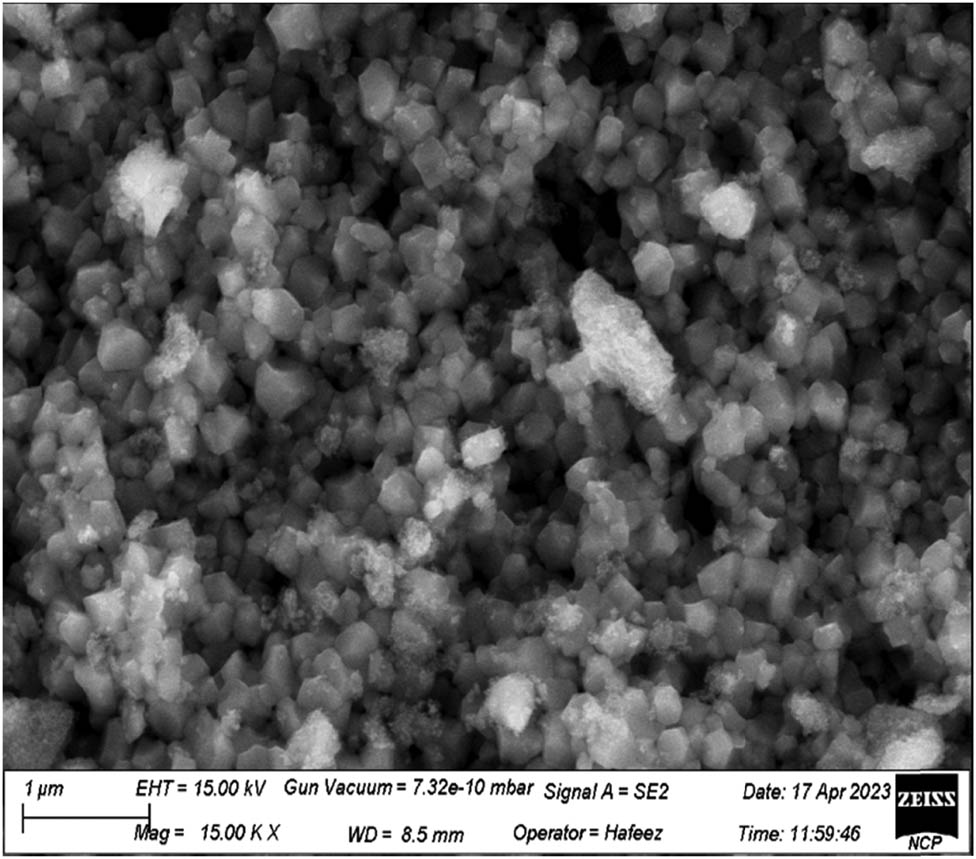

3.4 SEM analysis of TiO2 NPs

SEM was used to investigate the shape, size, as well as the surface morphological features of NPs. Figure 5 shows a micrograph of SEM for TiO2 NPs synthesized from an aqueous extract. Figure 5 shows the uniform distribution of NPs across the surface, revealing the spherical morphology with marginal agglomeration of synthesized NPs. It demonstrates that the NPs had a narrow spectrum of dispersal and were compactly distributed. The morphological structure of TiO2 NPs was found to be uniformly dispersed, smooth, and spherical in shape using the SEM image of the synthesized NPs. The average size of the synthesized NPs has been determined to be existing between 20 and 80 nm. The result of the current study was consistent with the recently used Mentha arvensis leaves extract that were used for the synthesis of spherical TiO2 NPs with a size of 20–70 nm in a green source synthesis [41].

SEM image of synthesized TiO2 NPs.

3.5 EDX analysis of TiO2 NPs

The elemental composition of green synthesized TiO2 NPs was analyzed using EDX techniques. The resultant TiO2 NP-derived titanium oxide signal is discernible in the EDX spectrum. The TiO2 NPs with weight percentage-related dominant signal in the EDX spectrum is depicted in Figure 6. The peaks at around 0.2, 4.3, and 4.5 were related to the binding energy of titanium as well as oxygen with weight percentage of 62.2%, 36.7%, respectively. The obtained result confirmed the successful synthesis TiO2 NPs [16]. This result demonstrates that the obtained NPs were extremely pure and that the elemental compounds were present in the TiO2 NPs without any impurity peaks.

EDX analysis for TiO2 NPs.

3.6 Antimicrobial activity

3.6.1 Antibacterial activity

The antibacterial activity of TiO2 NPs was evaluated against different kinds of pathogens, such as S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, and E. coli. The mean inhibition zone (measured in mm) surrounding each disc was calculated for each strain. Table 1 shows how the TiO2 NPs may inhibit the growth of bacteria. The highest zone of inhibition was identified in response to P. aeruginosa (45 ± 0.56 mm), followed by E. coli (43 ± 0.43 mm), S. aureus (37 ± 0.34 mm), and K. pneumoniae (33 ± 0.29 mm) at concentrations of 50 µg·mL−1. The significant antibacterial activity was revealed by P. aeruginosa (42 ± 0.45 mm), followed by E. coli (39 ± 0.34 mm), S. aureus (35 ± 0.24 mm), K. pneumoniae (30 ± 0.14 mm) at concentrations of 40 µg·mL−1. Furthermore, TiO2 NPs showed moderate activity (37 ± 0.25) against P. aeruginosa while (35 ± 0.21 mm), (31 ± 0.19 mm), and (29 ± 0.17 mm) against E. coli, S. aurous, and K. pneumonia at 30 µg·mL−1 of concentrations, respectively. The inhibition zone of TiO2 NPs revealed against P. aeruginosa was 36 ± 0.23 mm, followed by E. coli (33 ± 0.22 mm), S. aureus (30 ± 0.18 mm), and K. pneumoniae (25 ± 0.15 mm) at concentrations of 20 µg·mL−1. Whereas, the lowest inhibition zone was exhibited at 10 µg·mL−1 of concentration for P. aeruginosa (25 ± 0.33 mm), followed by E. coli (23 ± 0.44 mm), S. aureus (21 ± 0.53 mm), K. pneumoniae (19 ± 0.13 mm), respectively. The findings revealed that the highest zone of inhibition was observed by increasing the concentrations of TiO2 NPs which may lead to the interactions between the biological molecules and NPs. There is no reliable description available on mechanism study of antimicrobial activity. However, it was observed that TiO2 NPs produce intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) that may induce destructive effects inside the microbial cell. When TiO2 NPs are in contact with microbial cells, they will initiate the generation of ROS. These ROS can effectively destroy microbes by affecting the integrity of their cell walls, primarily due to the oxidation of phospholipids, which reduces adhesion and distorts the ion balance. The negative charge of microorganisms and the positive charge of TiO2 NPs cause an electromagnetic reaction, resulting in cell death [42]. The interaction of NPs with phosphorus or sulfur containing compounds, such as DNA and thiol groups of proteins can damage microorganisms by preventing DNA replication and inactivating proteins. These cause holes in the cell walls of bacteria, which increase permeability and cause cell death [43]. According to recent reports, the metal NPs may cause cell death by forming a long-lasting electrostatic interaction with the bacterial cell wall. Therefore, TiO2 NPs exhibit an excellent antibacterial activity and make them suitable for use as antibacterial agents against bacterial strains [30].

Zone of inhibition observed using the disc diffusion method against selected bacterial strains under different concentrations

| Concentration (zone of inhibition in mm) TiO2 NPs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains (µg·mL−1) | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 |

| P. aeruginosa | 25 ± 0.33 | 36 ± 0.23 | 37 ± 0.25 | 42 ± 0.45 | 45 ± 0.56 |

| E. coli | 23 ± 0.44 | 33 ± 0.22 | 35 ± 0.21 | 39 ± 0.34 | 43 ± 0.43 |

| S. aureus | 21 ± 0.53 | 30 ± 0.18 | 31 ± 0.19 | 35 ± 0.24 | 37 ± 0.34 |

| K. pneumonia | 19 ± 0.13 | 25 ± 0.15 | 29 ± 0.17 | 30 ± 0.14 | 33 ± 0.29 |

Results are expressed as mean value ± SE.

3.6.2 Antifungal activity

The potential antimicrobial activity of NPs to prevent an infection at the initial stage and inhibit the spread of diseases has sparked interest in developing new approaches to control the infection. NPs were used in pharmaceutical products, clinical diagnostic imaging, and clinical treatments due to their unique physical, chemical, and biological properties. The antifungal properties of titanium dioxide NPs were demonstrated by the zone inhibition on the culture medium. The concentration of fungi and the concentration of NPs determine the extent to which fungal growth is inhibited [31]. The diameter of the zone of inhibition for different strains of A. flavus, A. niger, C. albicans, and U. tritici was used to measure the antifungal activity of TiO2 NPs. The mean inhibition zone of TiO2 NPs was calculated in millimeters around each disc. The zones of inhibition were observed for all concentrations against the selected fungal pathogens. The maximum zone of inhibition was shown against C. albicans (37 ± 0.26 mm), followed by A. niger (35 ± 0.25 mm), A. flavus (33 ± 0.24 mm), and U. tritici (31 ± 0.23 mm) at 50 µg·mL−1 concentration (Table 2). The significant inhibition zone was shown against C. albicans (32 ± 0.24 mm), followed by A. niger (30 ± 0.23 mm), A. flavus (29 ± 0.21 mm), and U. tritici (27 ± 0.20 mm) at 40 µg·mL−1 concentration. Furthermore, TiO2 NPs show moderate activity at 30 µg·mL−1 of concentrations for C. albicans (29 ± 0.21 mm), followed by A. niger (27 ± 0.20 mm), A. flavus (24 ± 0.18 mm), and U. tritici (23 ± 0.15 mm), respectively. The inhibition zone against C. albicans was 25 ± 0.17 mm, followed by A. niger (23 ± 0.16 mm), A. flavus (21 ± 0.14 mm), and U. tritici (19 ± 0.11 mm) at 20 µg·mL−1 concentration. While, the lowest inhibition zone was exhibited at 10 µg·mL−1 of concentration for C. albicans (23 ± 0.19 mm), followed by A. niger (20 ± 0.17 mm), A. flavus (17 ± 0.15 mm), and U. tritici (16 ± 0.13 mm), respectively. The TiO2 NPs at the highest concentration showed the maximum zone of inhibition as also referred to as self-cleaning NPs and have efficient antimicrobial properties. Similarly, TiO2 NPs affected the antifungal activity on an aqueous extracts surface and found that the treatment inhibited the growth of fungi [44].

Zone of inhibition observed using the disc diffusion method against selected fungal strains under different concentrations

| Concentration (zone of inhibition in mm) TiO2 NPs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungal strains (µg·mL−1) | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 |

| C. albicans | 23 ± 0.19 | 25 ± 0.17 | 29 ± 0.21 | 32 ± 0.24 | 37 ± 0.26 |

| A. niger | 20 ± 0.17 | 23 ± 0.16 | 27 ± 0.20 | 30 ± 0.23 | 35 ± 0.25 |

| A. flavus | 17 ± 0.15 | 21 ± 0.14 | 24 ± 0.18 | 29 ± 0.21 | 33 ± 0.24 |

| U. tritici | 16 ± 0.13 | 19 ± 0.11 | 23 ± 0.15 | 27 ± 0.20 | 31 ± 0.23 |

Results are expressed as mean value ± SE.

3.7 Antidiabetic activity

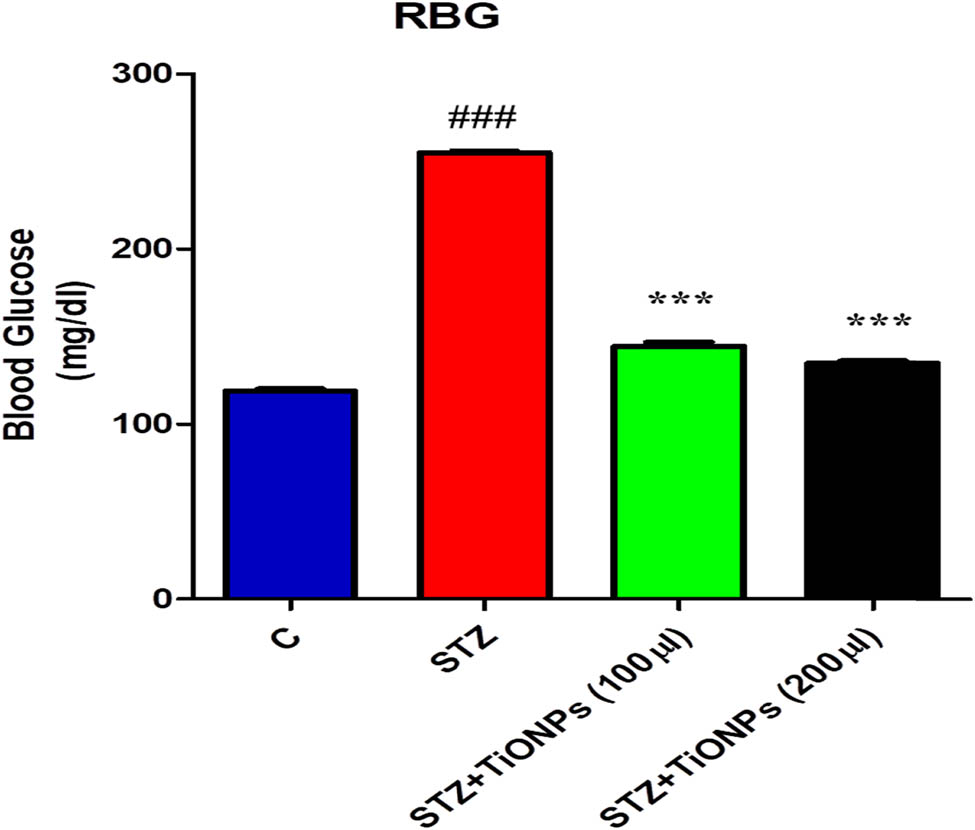

3.7.1 STZ induced hyperglycemia reduced by the treatment of TiO2 NPs

Diabetes causes chronic diseases such as nephropathy, polyneuropathy, retinopathy, cataracts, and cardiovascular disease. STZ-induced diabetes in tested animals is the most widely used animal model of human diabetes. The current study evaluates the potential of TiO2 NPs whether it can reduce the blood glucose level induced by STZ [45]. To achieve this, the mice received a single intraperitoneal injection of STZ at a dose of 90 mg·kg−1. Similarly, TiO2 NPs were also administered as a co-treatment at a dose of 100 and 200 µL on alternate days. Glucometer was used to check the blood glucose level. After that, the random glucose levels of all the animals of the group were checked after 72 h, respectively. The reading was taken after the induction of STZ injection as shown in Figure 7. The result indicates that a single injection of STZ caused hyperglycemia (upregulation of BGL) as compared to the untreated control in the mice suggesting that it induced diabetes in the mice. Similarly, the co-administration of TiO2 NPs along with STZ significantly reduced the blood glucose level in mice [46]. Interestingly, TiO2 NPs administration showed good effect on the blood glucose level at 200 µL, as shown in Figure 7. The findings demonstrate that the blood glucose levels were randomly high in all STZ group as compared to the normal one. In contrast, the random blood glucose levels were significantly reduced by the TiO2 NPs treatment.

Effect of STZ and STZ with TiO2-NPs that depict the random blood sugar in the experimental animals after the administration of STZ and TiO2 NPs and the blood glucose levels were checked with the glucometer. Significance; ### = 0.001, different from the control and *** = 0.01, different from STZ group, respectively.

3.7.2 Effect of TiO2 NPs on STZ-induced hyperglycemia and hypercholesterolemia

In order to assess the impact of STZ treatment on diabetic mice, an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) was performed a day before the animal’s sacrifice. In this analysis, the mice were kept on fasting for a period of 6–8 h. After that, the blood glucose was analyzed termed as at zero time [47]. Then, glucose solution was given to all the experimental mice at a dose of 200 mg·kg−1 to. Then, the blood glucose level was checked in a sequence like after 15, 30, 60, 120, and 180 min, respectively. The OGTT results indicate that at zero time, the STZ administered displayed high level of blood glucose. On the other hand, the animals, which received TiO2 NPs along with STZ, showed low level of blood glucose in GTT test. Interestingly both the control group and the group with animals treated with STZ and TiO2 NPs showed much difference in the blood glucose concentration in GTT test. The results suggest that STZ induced diabetes in animals revealed high blood glucose levels as compared to STZ with TiO2 NPs treated group at concentrations of 100 and 200 µL. The obtained results confirmed that the induced hyperglycemia of diabetes caused by STZ and both concentrations of TiO2 NPs can reduce its hyperglycemia in the experimental mice and indicate that it significantly reduced it [48]. Additionally, after receiving TiO2 NP treatment, a number of blood profile parameters were examined in mice with diabetes induced by STZ. In comparison to the control group, the diabetic mice treated using TiO2 NPs had significantly lower levels of TC, LDL, TGL, and VLDL. As demonstrated in Figure 8, it was also discovered that the administration of titanium dioxide NPs to diabetic mice resulted in a partial increase in HDL levels relative to the diabetic control group (p < 0.05).

The figure shows the GTT test performed in the experimental mice received STZ alone, STZ along with TiO2-NPs (a), total cholesterol (b), TGL (c), LDL test (d), VLDL (e), and HDL test (f). Glucose was administered at a dose of 200 mg·kg−1 to all the mice including control animals as well. The glucose level was checked with glucometer. Significance: # = 0.05, ## = 0.01, ### = 0.001 different from the control and * = 0.05, ** = 0.01, and *** = 0.001 different from STZ group, respectively.

3.8 Cytotoxic activity on HepG-2 cancer cell

The present investigation demonstrates the intense growth inhibition of TiO2 NPs against both human liver cancers cell lines and normal cell lines. Different concentration of TiO2 NPs (5, 25, 50, 75, and 100 μg·mL−1) were used to observe the potential cytotoxic activity against normal cell lines and HepG-2 cells lines The TiO2 NPs obtained through the green source synthesis showed significant cell viability in contrast to control group that was 43.2% at 100 µg·mL−1 of sample concentration. There was a significant decrease in the cell viability recorded in treated concentrations when compared to control. The results revealed that TiO2 NPs inhibited the growth of cancer cell lines in a concentration-dependent manner, based on the estimated cell viability percentages. The cancer cell proliferation in cell viability reached a maximum as the concentration of TiO2 NPs was increased. Accordingly, the cytotoxicity effect of TiO2 NPs on HepG-2 cells was dose dependent as shown in Figure 9. In addition, the effects of TiO2 NPs on cell viability were compared to normal (healthy) cell lines. However, no discernible differences were found in the viability of the cells or in their ability to grow effectively. Therefore, all subsequent experiments were carried out for cancer cell treatment with TiO2 NPs [49]. This is because biomolecules found in plant extract generate extra electrons in TiO2 NPs, which increase the production of ROS on the surface of cancer cell lines and favorable for cell death. The obtained results demonstrated a gradual decrease in cell viability with increasing TiO2 NP concentration. TiO2 NPs at dosages ranging from 5, 25, 50, 75, and 100 μg·mL−1 have the potential to induce oxidative stress, harm cell membranes, and elevate lipid peroxidation stress. This could be the result of oxidative stress increasing and decreasing the viability of HepG-2 cell lines. Similarly, Gandamalla et al., examined the cytotoxicity of titanium NPs on human epithelial lung and colon cells, which is dependent on dosage and size. They observed that small size TiO2 NPs showed the minimum IC50 values that were 21.80 and 24.83 mg·mL−1 for TiO2 NPs with size diameters of 18, 30, and 87 nm at concentrations of 0.1–100 mg·mL−1. It was determined that a concentration-dependent anticancer activity of titanium NPs was obtained. Accordingly, TiO2 NPs obtained stronger anticancer effects against the liver cancer cell line HepG-2 via an environmentally friendly approach [50].

% Cell viability of TiO2 NPs on HepG-2 cancer cell lines and normal cell lines at different concentrations (μg·mL−1). Statistical significance is represented as *p < 0.05), **p < 0.01), and ***p < 0.001).

3.9 Proposed mechanism for TiO2 NPs

The phytochemical study of Fagonia cretica plant extract reveals high content of secondary metabolites such as alkaloids, saponins, phenolics, flavonoids, and tannins [22,28] that act as reducing and stabilizing agent. The possible reaction mechanism of green synthesized TiO2 NPs was examined to find out the role of secondary metabolites which are present in an aqueous extract of Fagonia cretica that helps in the formation of TiO2 NPs. It was shown that an aqueous extract contains compounds having acid group carboxylic acid as a functional group in the structure. The major metabolite which are present in an aqueous extract is glycyl-l-proline. The titanyl hydroxide can be dehydrated by reacting with Fagonia cretica extract to synthesize TiO2 NPs. The lone pairs of electrons on the oxygen picks up a hydrogen ion from glycyl-l-proline. The TiO(OH)2 is said to be protonated and the protonated TiO (OH)2 loses a water molecule to form Ti3+ ions. Finally, the compound successfully removes a hydrogen ion from the Ti3+. Hence, the stabilization of TiO2 NPs is likely due to the reaction between Fagonia cretica aqueous and TiO (OH)2, involving water-soluble compounds with carboxylic acid groups, as illustrated in Scheme 1. Similar mechanism has been previously reported for the synthesis of TiO2 NPs using plant extract of Aeromonas hydrophila and the plant plays a dual role as a reducing as well as a stabilizing agent [51].

Possible mechanism for the synthesis of TiO2 NPs.

4 Conclusion

The current study highlights the potential of titanium dioxide NPs on biological processes. The plant extract was used to synthesize TiO2 NPs using Fagonia cretica, which serves as a capping and reducing agent. Different characterization techniques, such as FT-IR, UV-Vis, SEM, XRD, and EDX analysis were used to analyze the optical, structural, surface morphology, functional group, and elemental composition of the synthesized titanium dioxide NPs. The findings show that synthesized NPs were spherical in shape and crystalline in nature with size ranges from 20 to 80 nm. Moreover, the antimicrobial activity of synthesized titanium oxide NPs was studied against fungal and bacterial strains that showed potent zone of inhibition for all the selected pathogens. The TiO2 NPs demonstrated a remarkable dose-dependent antihyperglycemic activity that exceeded the antidiabetic activity. Increased electron production in titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) boosted reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation on the surface of cancer cells, leading to enhanced cell death. This study determined the optimal cytotoxic effect of TiO2 NPs. Furthermore, we think that this study may open a way for applications involving nanoscale drug delivery for the management of cytotoxic antimicrobial, and antidiabetic implications.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2025R191), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Funding information: The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2025R191), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The publication charges for this article are partially borne from Khyber Medical University Publication Fund (No. DIR/ORIC/Ref/24/00045).

-

Author contributions: conceptualization: M.H.A., I.A., and F.F.; formal analysis: B.O.A. and S.K.; funding acquisition: M.H.A; Investigation, S.K., M.H.A., F.F., and M.A.; methodology: S.K.; project administration: I.A.; resources: I.A.; supervision: I.A. and F.F.; writing – original draft: S.K. and M.A.; writing – review and editing: M.S., I.A., F.F., M.H.A., B.O.A., and Z.Z.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Torfi‐Zadegan S, Buazar F, Sayahi MH. Accelerated sonosynthesis of chromeno [4,3‐b] quinoline derivatives via marine‐bioinspired tin oxide nanocatalyst. Appl Organomet Chem. 2023;37(12):e7286.10.1002/aoc.7286Search in Google Scholar

[2] Nabi G, Raza W, Tahir M. Green synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticle using cinnamon powder extract and the study of optical properties. J Inorg Organomet Polym Mater. 2020;30:1425–9.10.1007/s10904-019-01248-3Search in Google Scholar

[3] Pathinti RS, Gollapelli B, Jakka SK, Vallamkondu J. Green synthesized TiO2 nanoparticles dispersed cholesteric liquid crystal systems for enhanced optical and dielectric properties. J Mol Liq. 2021;336:116877.10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116877Search in Google Scholar

[4] Auvinen S, Alatalo M, Haario H, Jalava J-P, Lamminmaki R-J. Size and shape dependence of the electronic and spectral properties in TiO2 nanoparticles. J Phys Chem C. 2011;115(17):8484–93.10.1021/jp112114pSearch in Google Scholar

[5] Kumar SG, Devi LG. Review on modified TiO2 photocatalysis under UV/visible light: selected results and related mechanisms on interfacial charge carrier transfer dynamics. J Phys Chem A. 2011;115(46):13211–41.10.1021/jp204364aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Tripathi AK, Singh MK, Mathpal MC, Mishra SK, Agarwal A. Study of structural transformation in TiO2 nanoparticles and its optical properties. J Alloy Compd. 2013;549:114–20.10.1016/j.jallcom.2012.09.012Search in Google Scholar

[7] Fazli S, Buazar F, Matroudi A. Theoretical insights into benzophenone pollutants removal from aqueous solutions using graphene oxide nanosheets. Theor Chem Acc. 2023;142(12):134.10.1007/s00214-023-03076-8Search in Google Scholar

[8] Muthee DK, Dejene BF. Effect of annealing temperature on structural, optical, and photocatalytic properties of titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Heliyon. 2021;7(6).10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07269Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Gupta SM, Tripathi M. A review of TiO2 nanoparticles. Chin Sci Bull. 2011;56:1639–57.10.1007/s11434-011-4476-1Search in Google Scholar

[10] Camps I, Borlaf M, Colomer MT, Moreno R, Duta L, Nita C, et al. Structure-property relationships for Eu doped TiO2 thin films grown by a laser assisted technique from colloidal sols. RSC Adv. 2017;7(60):37643–53.10.1039/C7RA05074GSearch in Google Scholar

[11] Sagadevan S, Imteyaz S, Murugan B, Anita Lett J, Sridewi N, Weldegebrieal GK, et al. A comprehensive review on green synthesis of titanium dioxide nanoparticles and their diverse biomedical applications. Green Process Synth. 2022;11(1):44–63.10.1515/gps-2022-0005Search in Google Scholar

[12] Singhal G, Bhavesh R, Kasariya K, Sharma AR, Singh RP. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ocimum sanctum (Tulsi) leaf extract and screening its antimicrobial activity. J Nanopart Res. 2011;13:2981–8.10.1007/s11051-010-0193-ySearch in Google Scholar

[13] Edison TNJI, Atchudan R, Lee YR. Binder-free electro-synthesis of highly ordered nickel oxide nanoparticles and its electrochemical performance. Electrochim Acta. 2018;283:1609–17.10.1016/j.electacta.2018.07.101Search in Google Scholar

[14] Mohany M, Ullah I, Fozia F, Aslam M, Ahmad I, Sharifi-Rad M, et al. Biofabrication of titanium dioxide nanoparticles catalyzed by solanum surattense: characterization and evaluation of their antiepileptic and cytotoxic activities. ACS Omega. 2023;8(19):16948–55.10.1021/acsomega.3c00858Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Rao KG, Ashok C, Rao KV, Chakra C, Tambur P. Green synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles using aloe vera extract. Int J Adv Res Phys Sci. 2015;2(1A):28–34.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Chatterjee A, Ajantha M, Talekar A, Revathy N, Abraham J. Biosynthesis, antimicrobial and cytotoxic effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Vigna unguiculata seeds. Int J Pharmacogn Phytochem Res. 2017;9(1):95–9.10.25258/ijpapr.v9i1.8047Search in Google Scholar

[17] Parameswaran G, Ray DW. Sleep, circadian rhythms, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Endocrinol. 2022;96(1):12–20.10.1111/cen.14607Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Herold Z, Herold M, Rosta K, Doleschall M, Somogyi A. Lower serum chromogranin B level is associated with type 1 diabetes and with type 2 diabetes patients with intensive conservative insulin treatment. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2020;12:1–5.10.1186/s13098-020-00569-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, Malanda B, Karuranga S, Unwin N, et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157:107843.10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107843Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Oguntibeju OO. Type 2 diabetes mellitus, oxidative stress and inflammation: examining the links. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol IJPPP. 2019;11(3):45.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Bhutkar M, Bhise S. In vitro assay of alpha amylase inhibitory activity of some indigenous plants. Int J Chem Sci. 2012;10(1):457–62.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Patel D, Kumar V. Phytochemical analysis & in-vitro anti obesity activity of different fractions of methanolic extract of Fagonia cretica L. Int J Pharm Sci Drug Res. 2020;12(3):282–6.10.25004/IJPSDR.2020.120311Search in Google Scholar

[23] Qureshi H, Asif S, Ahmed H, Al-Kahtani HA, Hayat K. Chemical composition and medicinal significance of Fagonia cretica: a review. Nat Prod Res. 2016;30(6):625–39.10.1080/14786419.2015.1036268Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Lam M, Carmichael AR, Griffiths HR. An aqueous extract of Fagonia cretica induces DNA damage, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in breast cancer cells via FOXO3a and p53 expression. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e40152.10.1371/journal.pone.0040152Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Sharma S, Joseph L, George M, Gupta V. Analgesic and anti-microbial activity of Fagonia indica. Pharmacologyonline. 2009;3:623–32.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Madhubala V, Pugazhendhi A, Thirunavukarasu K. Cytotoxic and immunomodulatory effects of the low concentration of titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) on human cell lines-An in vitro study. Process Biochem. 2019;86:186–95.10.1016/j.procbio.2019.08.004Search in Google Scholar

[27] Iqbal P, Ahmed D, Asghar MN. A comparative in vitro antioxidant potential profile of extracts from different parts of Fagonia cretica. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2014;7:S473–80.10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60277-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Hussain I, Ullah R, Khurram M, Ullah N, Baseer A, Khan FA, et al. Phytochemical analysis of selected medicinal plants. Afr J Biotechnol. 2011;10(38):7487–92.10.5897/AJB11.1948Search in Google Scholar

[29] Patidar V, Jain P. Green synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticle using Moringa oleifera leaf extract. Int Res J Eng Technol. 2017;4(3):1–4.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Anbumani D, Vizhi Dhandapani K, Manoharan J, Babujanarthanam R, Bashir A, Muthusamy K, et al. Green synthesis and antimicrobial efficacy of titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Luffa acutangula leaf extract. J King Saud Univ Sci. 2022;34(3):101896.10.1016/j.jksus.2022.101896Search in Google Scholar

[31] Chidambaram Jayaseelan CJ, Rajendiran Ramkumar RR, Rahuman A, Pachiappan Perumal PP. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using seed aqueous extract of Abelmoschus esculentus and its antifungal activity. Ind Crops Prod. 2013;45:423–9.10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.12.019Search in Google Scholar

[32] Nagaraja S, Ahmed SS, DR B, Goudanavar P, Fattepur S, Meravanige G, et al. Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles of psidium guajava leaf extract and evaluation for its antidiabetic activity. Molecules. 2022;27(14):4336.10.3390/molecules27144336Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Roe K, Gibot S, Verma S. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 (TREM-1): a new player in antiviral immunity? Front Microbiol. 2014;5:627.10.3389/fmicb.2014.00627Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Ramakrishna V, Jailkhani R. Evaluation of oxidative stress in Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus (IDDM) patients. Diagn Pathol. 2007;2(1):1–6.10.1186/1746-1596-2-22Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Hamzeh M, Sunahara GI. In vitro cytotoxicity and genotoxicity studies of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles in Chinese hamster lung fibroblast cells. Vitro Toxicol. 2013;27(2):864–73.10.1016/j.tiv.2012.12.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Subhapriya S, Gomathipriya P. Green synthesis of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles by Trigonella foenum-graecum extract and its antimicrobial properties. Microb Pathog. 2018;116:215–20.10.1016/j.micpath.2018.01.027Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Parrino F, De Pasquale C, Palmisano L. Influence of surface‐related phenomena on mechanism, selectivity, and conversion of TiO2‐induced photocatalytic reactions. ChemSusChem. 2019;12(3):589–602.10.1002/cssc.201801898Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Goutam SP, Saxena G, Singh V, Yadav AK, Bharagava RN, Thapa KB. Green synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles using leaf extract of Jatropha curcas L. for photocatalytic degradation of tannery wastewater. J Chem Eng. 2018;336:386–96.10.1016/j.cej.2017.12.029Search in Google Scholar

[39] Hudlikar M, Joglekar S, Dhaygude M, Kodam K. Green synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles by using aqueous extract of Jatropha curcas L. latex. Mater Lett. 2012;75:196–9.10.1016/j.matlet.2012.02.018Search in Google Scholar

[40] Patil PB, Mali SS, Kondalkar VV, Pawar NB, Khot KV, Hong CK, et al. Single step hydrothermal synthesis of hierarchical TiO2 microflowers with radially assembled nanorods for enhanced photovoltaic performance. RSC Adv. 2014;4(88):47278–86.10.1039/C4RA07682FSearch in Google Scholar

[41] Ahmad W, Jaiswal KK, Soni S. Green synthesis of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles by using Mentha arvensis leaves extract and its antimicrobial properties. Inorg Nano-Met Chem. 2020;50(10):1032–8.10.1080/24701556.2020.1732419Search in Google Scholar

[42] Aslam M, Abdullah AZ, Rafatullah M. Recent development in the green synthesis of titanium dioxide nanoparticles using plant-based biomolecules for environmental and antimicrobial applications. J Ind Eng Chem. 2021;98:1–16.10.1016/j.jiec.2021.04.010Search in Google Scholar

[43] Vizhi DK, Supraja N, Devipriya A, Tollamadugu NVKVP, Babujanarthanam R. Evaluation of antibacterial activity and cytotoxic effects of green AgNPs against Breast Cancer Cells (MCF 7). Adv Nano Res. 2016;4(2):129.10.12989/anr.2016.4.2.129Search in Google Scholar

[44] Irshad MA, Nawaz R, ur Rehman MZ, Imran M, Ahmad J, Ahmad S, et al. Synthesis and characterization of titanium dioxide nanoparticles by chemical and green methods and their antifungal activities against wheat rust. Chemosphere. 2020;258:127352.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127352Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] BarathManiKanth S, Kalishwaralal K, Sriram M, Pandian SRK, Youn H-S, Eom S, et al. Anti-oxidant effect of gold nanoparticles restrains hyperglycemic conditions in diabetic mice. J Nanobiotechnol. 2010;8(1):1–15.10.1186/1477-3155-8-16Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Kumar BD, Mitra A, Manjunatha M. In vitro and in vivo studies of antidiabetic Indian medicinal plants: A review. J Herb Med Toxicol. 2009;3(2):9–14.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Tariq M, Ullah B, Khan MN, Ali A, Hussain K. Skimmia lareoula fractions via TLR-4/COX2/IL-1β rescues adult mice against Alloxan induced hyperglycemia induced synaptic and memory dysfunction. J Xi’an Shiyou Univ Nat Sci Ed. 2023;19(1).Search in Google Scholar

[48] Houghton PJ, Zarka R, de las Heras B, Hoult J. Fixed oil of Nigella sativa and derived thymoquinone inhibit eicosanoid generation in leukocytes and membrane lipid peroxidation. Planta Med. 1995;61(01):33–6.10.1055/s-2006-957994Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Balashanmugam P, Durai P, Balakumaran MD, Kalaichelvan PT. Phytosynthesized gold nanoparticles from C. roxburghii DC. leaf and their toxic effects on normal and cancer cell lines. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2016;165:163–73.10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.10.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Gandamalla D, Lingabathula H, Yellu N. Nano titanium exposure induces dose- and size-dependent cytotoxicity on human epithelial lung and colon cells. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2019;42(1):24–34.10.1080/01480545.2018.1452930Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Jayaseelan C, Rahuman AA, Roopan SM, Kirthi AV, Venkatesan J, Kim S-K, et al. Biological approach to synthesize TiO2 nanoparticles using Aeromonas hydrophila and its antibacterial activity. Spectrochim Acta Part A: Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2013;107:82–9.10.1016/j.saa.2012.12.083Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase