Abstract

In this study, composite nanofiber films for the wound dressing application were prepared with silk fibroin (SF) and polycaprolactone (PCL) by electrospinning techniques, and the SF/PCL composite nanofiber films were characterized by the combined techniques of scanning electron microscopy (SEM), the equilibrium water content, Fourier transform infrared spectrometer test, X-ray diffraction (XRD) and cell viability test. The results indicated several parameters, including the rotating roller speed, solution concentration, and SF/PCL ratio, affected SF/PCL composite nanofibers’ diameter size, distribution, and wettability. The SF/PCL composite nanofiber manifested a smaller fiber diameter and more uniform nanofibers than pure PCL nanofibers. The contact angle changed from 121 ± 2° of the neat pure PCL to full wetting of 40% SF/PCL composite nanofiber films at 2,000 rpm, indicating good hydrophilicity. Meanwhile, cells exhibit adhesion and proliferation on the composite nanofiber films. These results testified that SF/PCL composite nanofiber films may provide good wettability for cell adhesion and proliferation. It was suggested that optimized SF/PCL composite nanofiber films could be used as a potential biological dressing for skin wound healing.

1 Introduction

The human body’s skin is a natural protective barrier against external pathogens but it is also fragile and easily injured leading to forming wounds to some degree [1]. Normal wound healing needs a long time, and exudation may be produced during the wound recovery period, which leads to adverse consequences such as wound inflammation and even partially purulent infection. So, it is particularly important to select appropriate wound dressings that are non-toxic and biocompatible for absorbing the exudation and accelerating wound healing [2,3]. In clinics, there are more types of wound dressings, such as hydrogels [4] and spinning films [5]. Compared with traditional gauze [6], these materials are antibacterial, hydrophilic, breathable, and biocompatible, and even some may be degradable to avoid secondary injury from multiple replacements [7]. In recent years, with the development of electrostatic spinning technology, electrospun nanofibers have been widely used in many fields such as environmental air filtration [8], biosensing [9], nanoelectronics [10], and biomedical engineering [11] due to their unique properties (e.g., large specific surface area and high porosity). Especially in biomedicine, some good biocompatible materials, such as natural SF [12], gelatin [13], and alginate [14] and synthetic polyethylene glycol [15], polylactic acid, and polycaprolactone (PCL) [16], are often used in wound healing [17], drug transport [18], tissue engineering [19], neural repair [20], and so on. By electrospinning technology, different types of composite nanofiber films were prepared according to the characteristics of the materials [21,22]. In particular, natural silk fibroin (SF) extracted from silk is a good biomaterial [23,24]. It exhibits properties such as good biocompatibility, biodegradability, mechanical properties and hydrophilicity, and non-toxicity, and may make cell proliferation, adhesion, and migration to promote wound healing as wound dressings [25,26]. Yet, high molecular weight PCL has excellent strength, elasticity, and controllable biodegradability, and therefore, was preferred as wound dressings [27]. However, hydrophobic PCL hindered wound exudate absorption and cell adhesion, and further limited the use [28]; while the special structure of pure SF (β-sheet secondary structure) may improve hydrophilicity for electrospinning [29]. So, it is optimal to prepare the PCL/SF composite to electrospun composite nanofibers due to good spinnability and non-toxicity [30,31]. Although the addition of SF will accelerate the degradation of PCL, it only degrades 1.44% after 90 days [32] and 8.08% after 2 weeks [33], and this slow degradation is conducive to structural stability and can effectively promote the long repair period of biological tissues. This composite nanofiber film with good hydrophilicity and biocompatibility can be used as a carrier for other antibacterial substances, such as chitosan [34], minocycline hydrochloride antibiotics [35], etc., which could provide more valuable reference for wound dressings.

Studies have shown that smaller diameter and uniformity of fiber can provide high porosity and easier absorption of water molecules to promote hydrophilicity and cell adhesion and proliferation [34]. The spinning parameters like the fiber diameter, voltage, flow rate, roller speed, and spinning concentration were affected [36,37], but few studies testified SF/PCL composite nanofiber films as wound dressings by the combination of high roller speed and high solution concentration to explore lower fiber diameter and better hydrophilicity, as well as the impact on cell compatibility. In this study, SF/PCL composite nanofiber films were prepared by different roller rotation speeds and SF contents to explore better SF/PCL composite nanofiber films for skin tissue repair.

2 Experimental methods

2.1 Materials

SF powder was obtained from Senyuan Biotechnology Co. Ltd (Xi’an). PCL (average molecular weight: 40,000) was obtained from Shangpu Boyuan (Beijing) Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP, 99.5%) was obtained from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Dichloromethane and other chemical reagents in this experiment were obtained from Chengdu Kolon Chemical Co. Ltd.

2.2 Preparation of the electrospinning solution and electrospinning parameter setting

About 0.8 g of PCL was dissolved in a mixed solvent of 10 mL HFIP and 5 mL DCM, and SF was added according to different SF/PCL weight percentages (0, 5, 20, and 40). Furthermore, the mixed solution was stirred for 12 h at room temperature to finally obtain a transparent spinning solution. The SF/PCL composite nanofibers were electrospun by an electrostatic spinning machine (model: TL-01, Tongli Micro-Nano Technology Co.), and the specific schematic diagram is shown in Figure 1. Briefly, the electrospun solution was loaded into a 10 mL syringe; the liquid was ejected from the catheter through a 22-gauge needle and extruded into nanofibers with a syringe pump at room temperature and an ambient relative humidity of 45–55%. The following optimized electrospinning parameters were kept in the whole experiment: applied electric field voltage, 15–18 kV; feeding rate, 1–1.2 mL·h−1; and the tip to collector distance, 10 cm. During this process, the SF/PCL nanofibers were sprayed on a rotating cylindrical drum with aluminum foil, and different roller rotation speeds (250, 500, 1,000, and 2,000 rpm) were adjusted to prepare sample groups. Finally, the SF/PCL nanofiber films were obtained from the collector surface and dried at room temperature prior to use.

Schematic diagram of the electrospinning process.

2.3 Characterization of SF/PCL nanofiber films

The morphology of SF/PCL composite nanofiber films was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM; SU8010, Japan). The average diameter size and distribution of fibers of 50 fibers randomly selected from each sample were determined. The microstructure was analyzed by using a Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (Nicolet Co., USA) with a scan range of 4,000 to 400 cm−1, and recorded with a resolution of 2 cm−1 by 45 scans. The crystal structure was analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD; Bruker, Germany) with a scan range of 5–80 cm−1. Wettability was evaluated by measuring the contact angle of the fiber films using a contact angle meter (WM2017013, Sweden Beolean Technology Co). All measured samples were tested three times, and the average value was obtained.

2.4 Biocompatibility of SF/PCL nanofiber films

In order to evaluate the biocompatibility of SF/PCL composite nanofiber films (soaked in 75% ethanol, dried overnight, and then sterilized with UV for 5 min), a cell viability test was performed using human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) for 24 h, and cell morphology and distribution were observed by microscope. The specific process was as follows: first, the nanofiber films were put on the bottom of 48-well plates, and cells were seeded on them at a density of 3,000 cells per well; then HUVECs were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle’s medium (10% fetal bovine serum). In all tests (blank, control, and sample groups), HUVECs were incubated at 37°C for 24 h, and then HUVECs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, stained with 0.014% methyl violet for 5 min, and observed and photographed using a microscope. In order to evaluate the cell viability of SF/PCL composite nanofiber films under different spinning conditions, a cell viability test was performed using HUVECs for 5 days, and cell viability was assayed with CCK-8 (Cell Counting Kit-8). The nanofiber films were put on the bottom of 96-well plates and cells were seeded on them at a density of 2,000 cells per well; other culture conditions were the same as above. Then, the medium was replaced with 100 μL of the CCK-8 solution and incubated at 37°C for another 1 h. Finally, the absorbance of each well was measured using a spectrophotometer to obtain the desired optical density (OD450) values.

2.5 Statistical analysis

The data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9 software. A significant difference was considered with p < 0.05.

3 Results and discussion

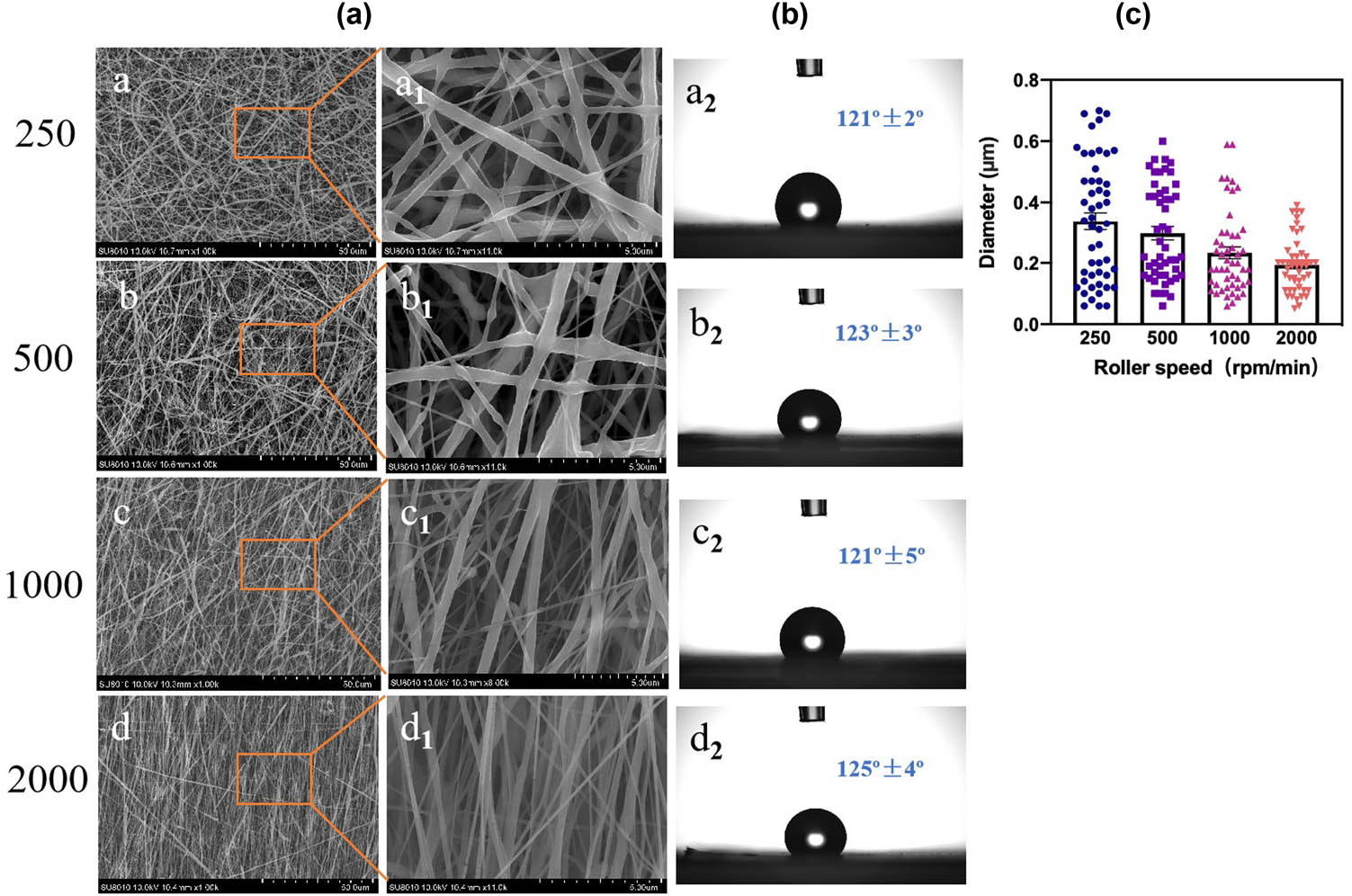

3.1 Effect of roller speed on the structure and hydrophilicity of pure PCL nanofiber films

Uniform and order nanofibers can provide higher surface area and interconnected pores to facilitate cell adhesion and proliferation as wound dressings [38]. The roller speed was one of the key factors to affect the diameter of pure PCL nanofibers. The SEM results showed that with the increase of the roller speed, the diameter size of nanofibers became more uniform and the nanofibers were orderly arranged toward particular directions (Figure 2a). At lower roller speeds (250 and 500 rpm), the electrospun nanofibers were in disorder, and at higher roller speeds (1,000 and 2,000 rpm), the nanofibers tended to be in order. Moreover, the nanofibers’ diameter decreased gradually as the roller speed increased. The average diameter of the nanofibers was in the range of 350–200 nm (Figure 2c) and the distribution was more uniform. It was because the fibers were stretched quickly from the electrospinning needles ejecting rapidly when the roller was accelerated, making the fibers finer. At the same time, acceleration can reduce the number of fibers that are randomly dropped on the roller. Under similar conditions, the fiber diameter distribution at a 150 rpm roller speed was uneven, showing micro-nanometer levels, which was different from our results [39]. Pure PCL is a kind of hydrophobic material, and no matter how the nanofibers are arranged, the contact angle was around 120°, which showed that PCL nanofiber films had good hydrophobicity (Figure 2b). These results indicated that it was feasible to increase the electrospun roller speed to improve the size and uniformity of nanofibers.

SEM micrographs of PCL electrospun films at different roller speeds. The second column shows the high-magnification images corresponding to the first column (a) and the corresponding wettability (b). The diameter size distribution (c).

3.2 Effect of SF content on the structure and hydrophilicity of SF/PCL composite nanofiber films

In the electrospinning process, the spinning solution concentration was considered to be an important parameter to affect the fiber structure [40]. Different contents of SF were used to prepare SF/PCL composite nanofibers at a 250 rpm roller rotation speed (Figure 3). Figure 3a shows that some small beads were formed at lower concentrations (5–10%), which may be the lower viscosity spinning fluid leading to an unstable jet flow. When the SF content was in the range of 0–40%, the fiber size gradually decreased from 330 to 90 nm, and the fiber diameter size distribution was more uniform (Figure 3c). When the roller rotation speed was constant, the viscosity of the solution affected the uniformity and diameter size of the fiber formation. Research showed that the increase of SF content was beneficial to shorten the fiber diameter; however, it did not shorten the fiber diameter below 100 nm [22,33]. Meanwhile, SF may improve the wettability of the fiber film. When SF was added to the PCL solution, the concentration changed from 0 to 40 wt%, the contact angle decreased from 121° to 56°, which showed better hydrophilicity (Figure 3b). Compared with the study by Lee et al. [27], this experiment can reach the contact angle of SF/PCL nanofiber films below 98° after the addition of SF. It has been proved that the increase of SF content may decrease the contact angle of the SF/PCL fiber film; meanwhile, this composite nanofiber film may provide a better moist environment for tissue regeneration. Of course, under the same conditions, the hydrophilicity of 40% SF/PCL films was greater than that of the films, and the contact angle was less than 75° [41]. These results indicated that SF can improve the hydrophilicity and the order of SF/PLC composite nanofiber film, and they have great potential for skin wound healing [42].

SEM micrographs of PCL electrospun films with different SF contents at 250 rpm roller speeds. The second column shows the images at high magnification corresponding to the first column (a) and the corresponding wettability (b). The diameter size distribution at a 250 rpm roller speed (c).

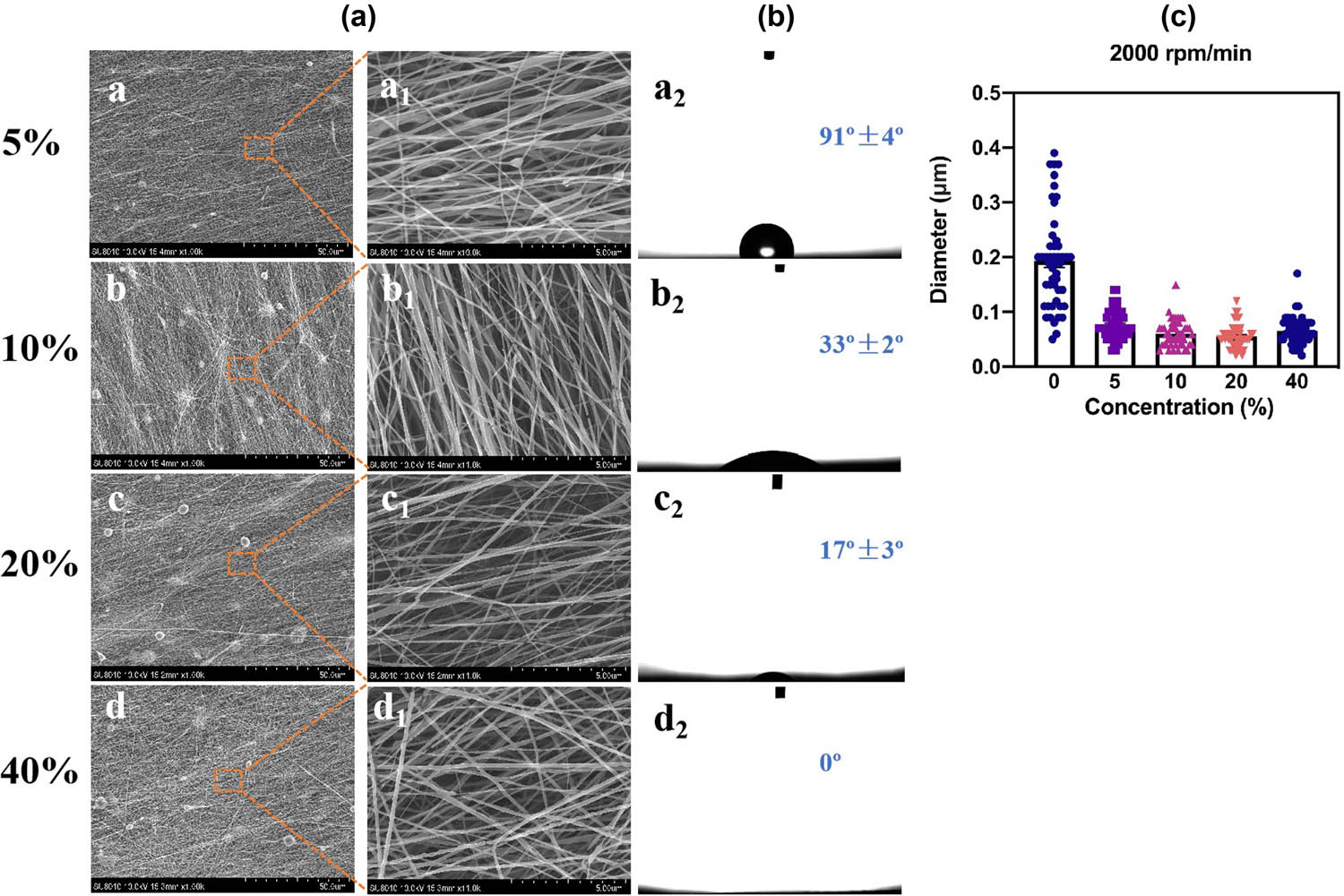

Under the above conditions, the effect of different concentrations of SF solution on the uniformity of nanofiber films was determined when the roller rotation speed was increased to 2,000 rpm. The results are shown in Figure 4: as the SF content increased, the nanofiber remained well organized (Figure 4a) and the average diameter size decreased gradually from 193.4 to 50 nm (Figure 4c). The higher roller rotation speed (2,000 rpm) resulted in a smaller fiber diameter and more uniformity and compacted diameter distribution compared to that of the 250 rpm roller rotation speed. The wettability of SF/PCL composite films also improved gradually with the increase of SF content, especially the 40% SF/PCL fiber, which can achieve complete wetting (Figure 4b). Undoubtedly, it was more advantageous for cell adhesion and proliferation. These results showed that an increase of both SF content and roller speeds may spin finer and more uniform diameter nanofiber, which was beneficial to improve the wettability of SF/PCL composite nanofiber films. It has been shown that the contact angle of SF/PCL nanofiber fibers can be reduced by adding SF [43], after UV-ozone irradiation and acrylic acid treatment [44], or by adding PEO[45]. The last two methods are too complicated, and in both methods, complete wetting cannot be achieved. In comparison, it is more beneficial to the application of biocompatible composite fiber membranes by controlling the SF content and roller rotation speed to achieve complete wetting.

SEM micrographs of PCL electrospun films with different SF contents at 2,000 rpm roller speeds. The second column shows the high-magnification images corresponding to the first column (a) and the corresponding wettability (b). The particle size distribution at 2,000 rpm roller speed (c).

3.3 FTIR analysis

The FTIR spectra of the nanofibers are shown in Figure 5. For the pure SF, PCL, and SF/PCL composite nanofiber films, the peak characteristics of PCL can be observed clearly by comparing the spectra of other samples. The stretching band C═O of carbonyl esters was located at 1,719 cm−1 in pure PCL nanofibers. The strong band of PCL crystalline phase at 1,240 cm−1 was assigned to C−O and C−C stretching, the peak at 1,173 cm−1 was attributed to vibrations in COC, C–O, and C–C, and the peak at 732 cm−1 represented CH2 bending of the caprolactone chain [46]. All characteristic bands of PCL were presented in SF/PCL composite nanofiber films; amide I, amide II and amide III bands appeared in pure SF, and further were more obvious in SF/PCL. These results testified that SF and PCL obtained a good molecular bonding.

FTIR patterns of SF/PCL nanofiber films.

3.4 XRD analysis

The XRD patterns of SF, pure PCL, and 40% SF/PCL composite nanofibers are shown in Figure 6. SF was an amorphous substance, and pure PCL showed a semi-crystalline state with three obvious diffraction peaks at 21.5° (110), 22.2° (111), and 23.9° (200) [47]. After the addition of the SF/PCL composite, the characteristic reflection peak became weaker and wider. Obviously, the crystallinity of PCL decreased while its crystalline structure did not change with the addition of SF.

XRD patterns of SF/PCL nanofiber films.

3.5 Biocompatibility evaluation of SF/PCL composite nanofiber films

The cell viability of HUVECs grown on SF/PCL composite nanofiber films within 24 h was evaluated (Figure 7a). The cell viability of HUVECs grown on SF/PCL composite nanofiber films was continually monitored for 5 days by the CCK-8 assay technique (Figure 7b and c). The results indicated that at lower 250 rpm, higher 2,000 rpm, or with added SF content, there was no significant difference compared with the blank group over 24 h, showing that composite nanofibers were nontoxic. At a high roller rotation speed, the average OD value was 7% higher than that at a low speed, which showed good cell viability. These results indicated that the structure and wettability of SF/PCL affected the cells’ proliferation and differentiation, and it also provided a better research idea for wound healing and skin engineering repair.

Fluorescence images of HUVECs grown on SF/PCL composite nanofiber films within 24 h at 250 and 2,000 rpm roller rotation speeds (a). HUVECs viability was cultured on various specimens for 5 days at 250 and 2,000 rpm roller rotation speeds (b and c). Data represent mean ± standard deviation (n = 5). The bar scale is 200 μm. *p < 0.5, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs blank; # p < 0.5, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 vs 0%.

4 Conclusion

Different contents of SF were mixed with PCL to prepare SF/PCL composite nanofiber films by electrospinning technology. The process parameter of roller rotation speeds affected the diameters and diameter distributions of nanofibers, and SF contents affected the hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity of SF/PCL composite films. The diameter of the 40 wt% SF/PCL composite nanofiber was the smallest and more uniformly distributed at a higher 2,000 rpm roller rotation speed and could be completely wetted to improve cell proliferation and adhesion. SF/PCL composite nanofibers had better cell viability. It was concluded that the SF/PCL composite nanofiber films were valuable for application as a dressing to promote wound healing.

-

Funding information: This research was supported by the Key Project of Sichuan Medical Association (Q17002), Chengdu Municipal Technological Innovation R&D Project (2021-YF05-01871-SN), and Project of Chengdu Municipal Health Commission (2021059).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Li, T. T., Y. Zhong, H. K. Peng, H. T. Ren, H. Chen, J. H. Lin, et al. Multiscale composite nanofiber membranes with asymmetric wetability: preparation, characterization, and applications in wound dressings. Journal of Materials Science, Vol. 56, 2021, pp. 4407–4419.10.1007/s10853-020-05531-4Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Bi, H., T. Feng, B. Li, and Y. Han. In vitro and in vivo comparison study of electrospun PLA and PLA/PVA/SA fiber membranes for wound healing. Polymers, Vol. 12, 2020, id. 839.10.3390/polym12040839Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Mehteroğlu, E., A. B. Çakmen, B. Aksoy, S. Balcıoğlu, S. Köytepe, B. Ateş, et al. Preparation of hybrid PU/PCL fibers from steviol glycosides via electrospinning as a potential wound dressing materials. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, Vol. 137, 2020, id. 49217.10.1002/app.49217Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Liang, Y., J. He, and B. Guo. Functional hydrogels as wound dressing to enhance wound healing. ACS Nano, Vol. 15, 2021, pp. 12687–12722.10.1021/acsnano.1c04206Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Peng, Y., Y. Ma, Y. Bao, Z. Liu, L. Chen, F. Dai, et al. Electrospun PLGA/SF/artemisinin composite nanofibrous membranes for wound dressing. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, Vol. 183, 2021, pp. 68–78.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.04.021Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Gao, Y., Z. Qiu, L. Liu, M. Li, B. Xu, D. Yu, et al. Multifunctional fibrous wound dressings for refractory wound healing. Journal of Polymer Science, Vol. 60, 2022, pp. 2191–2212.10.1002/pol.20220008Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Chaiarwut, S., P. Ekabutr, P. Chuysinuan, T. Chanamuangkon, and P. Supaphol. Surface immobilization of PCL electrospun nanofibers with pexiganan for wound dressing. Journal of Polymer Research, Vol. 28, 2021, id. 344.10.1007/s10965-021-02669-wSuche in Google Scholar

[8] He, Z. Y. and Z. J. Pan. Biobased polymer SF/PHBV composite nanofiber membranes as filtration and protection materials. The Journal of The Textile Institute, Vol. 114, 2021, pp. 55–65.10.1080/00405000.2021.2020419Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Zhang, Y., S. Liu, Y. Li, D. Deng, X. Si, Y. Ding, et al. Electrospun graphene decorated MnCo2O4 composite nanofibers for glucose biosensing. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, Vol. 66, 2015, pp. 308–315.10.1016/j.bios.2014.11.040Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Kundu, S., R. S. Gill, and R. F. Saraf. Electrospinning of PAH nanofiber and deposition of Au NPs for nanodevice fabrication. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, Vol. 115, 2011, pp. 15845–15852.10.1021/jp203851sSuche in Google Scholar

[11] Omer, S., L. Forgách, R. Zelkó, and I. Sebe. Scale-up of electrospinning: market overview of products and devices for pharmaceutical and biomedical purposes. Pharmaceutics, Vol. 13, 2021, pp. 286–306.10.3390/pharmaceutics13020286Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Chen, W., D. Li, A. Ei-Shanshory, M. El-Newehy, H. A. Ei-Hamshary, S. S. Al-Deyab, et al. Dexamethasone loaded core–shell SF/PEO nanofibers via green electrospinning reduced endothelial cells inflammatory damage. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, Vol. 126, 2015, pp. 561–568.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.09.016Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Deng, L., X. Zhang, Y. Li, F. Que, X. Kang, Y. Liu, et al. Characterization of gelatin/zein nanofibers by hybrid electrospinning. Food Hydrocolloids, Vol. 75, 2018, pp. 72–80.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.09.011Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Gutierrez-Gonzalez, J., E. Garcia-Cela, N. Magan, and S. S. Rahatekar. Electrospinning alginate/polyethylene oxide and curcumin composite nanofibers. Materials Letters, Vol. 270, 2020, id. 127662.10.1016/j.matlet.2020.127662Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Karahaliloğlu, Z. Electrospun PU-PEG and PU-PC hybrid scaffolds for vascular tissue engineering. Fibers and Polymers, Vol. 18, 2017, pp. 2135–2145.10.1007/s12221-017-7368-4Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Liu, Q., H. Jia, W. Ouyang, Y. Mu, and Z. Wu. Fabrication of antimicrobial multilayered nanofibrous scaffolds-loaded drug via electrospinning for biomedical application. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, Vol. 9, 2021, pp. 49–60.10.3389/fbioe.2021.755777Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Yang, X., L. Fan, L. Ma, Y. Wang, S. Lin, F. Yu, et al. Green electrospun Manuka honey/silk fibroin fibrous matrices as potential wound dressing. Materials & Design, Vol. 119, 2017, pp. 76–84.10.1016/j.matdes.2017.01.023Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Luraghi, A., F. Peri, and L. Moroni. Electrospinning for drug delivery applications: a review. Journal of Controlled Release, Vol. 334, 2021, pp. 463–484.10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.03.033Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Qasim, S. B., M. S. Zafar, S. Najeeb, Z. Khurshid, A. H. Shah, S. Husain, et al. Electrospinning of chitosan-based solutions for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, Vol. 19, 2018, id. 407.10.3390/ijms19020407Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Zhao, Y., Y. Liang, S. Ding, K. Zhang, H. Q. Mao, and Y. Yang. Application of conductive PPy/SF composite scaffold and electrical stimulation for neural tissue engineering. Biomaterials, Vol. 255, 2020, id. 120164.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120164Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Pang, L., P. Sun, X. Dong, T. Tang, Y. Chen, Q. Liu, et al. Shear viscoelasticity of electrospinning PCL nanofibers reinforced alginate hydrogels. Materials Research Express, Vol. 8, 2021, id. 055402.10.1088/2053-1591/abfb28Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Li, L., H. Li, Y. Qian, X. Li, G. K. Singh, L. Zhong, et al. Electrospun poly(ɛ-caprolactone)/silk fibroin core-sheath nanofibers and their potential applications in tissue engineering and drug release. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, Vol. 49, 2011, pp. 223–232.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2011.04.018Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Juncos Bombin, A. D., N. J. Dunne, and H. O. McCarthy. Electrospinning of natural polymers for the production of nanofibres for wound healing applications. Materials Science and Engineering: C, Vol. 114, 2020, id. 110994.10.1016/j.msec.2020.110994Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Li, Z., P. Liu, T. Yang, Y. Sun, Q. You, J. Li, et al. Composite poly(l-lactic-acid)/silk fibroin scaffold prepared by electrospinning promotes chondrogenesis for cartilage tissue engineering. Journal of Biomaterials Applications, Vol. 30, 2016, pp. 1552–1565.10.1177/0885328216638587Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Singh, R., D. Eitler, R. Morelle, R. P. Friedrich, B. Dietel, C. Alexiou, et al. Optimization of cell seeding on electrospun PCL-silk fibroin scaffolds. European Polymer Journal, Vol. 134, 2020, id. 109838.10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2020.109838Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Liu, Z., J. Liu, N. Liu, X. Zhu, and R. Tang. Tailoring electrospun mesh for a compliant remodeling in the repair of full-thickness abdominal wall defect - The role of decellularized human amniotic membrane and silk fibroin. Materials Science and Engineering: C, Vol. 127, 2021, id. 112235.10.1016/j.msec.2021.112235Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Lee, J. M., T. Chae, F. A. Sheikh, H. W. Ju, B. M. Moon, H. J. Park, et al. Three dimensional poly(ε-caprolactone) and silk fibroin nanocomposite fibrous matrix for artificial dermis. Materials Science and Engineering: C, Vol. 68, 2016, pp. 758–767.10.1016/j.msec.2016.06.019Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Behtaj, S., F. Karamali, E. Masaeli, Y. G. Anissimov, and M. Rybachuk. Electrospun PGS/PCL, PLLA/PCL, PLGA/PCL and pure PCL scaffolds for retinal progenitor cell cultivation. Biochemical Engineering Journal, Vol. 166, 2021, id. 107846.10.1016/j.bej.2020.107846Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Dadras Chomachayi, M., A. Solouk, and H. Mirzadeh. Improvement of the electrospinnability of silk fibroin solution by atmospheric pressure plasma treatment. Fibers and Polymers, Vol. 20, 2019, pp. 1594–1600.10.1007/s12221-019-9015-8Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Liverani, L., J. Lacina, J. A. Roether, E. Boccardi, M. S. Killian, P. Schmuki, et al. Incorporation of bioactive glass nanoparticles in electrospun PCL/chitosan fibers by using benign solvents. Bioactive Materials, Vol. 3, 2018, pp. 55–63.10.1016/j.bioactmat.2017.05.003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Nazeer, M. A., E. Yilgor, and I. Yilgor. Electrospun polycaprolactone/silk fibroin nanofibrous bioactive scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Polymer, Vol. 168, 2019, pp. 86–94.10.1016/j.polymer.2019.02.023Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Dias, J. R., A. Sousa, A. Augusto, P. J. Bártolo, and P. L. Granja. Electrospun polycaprolactone (PCL) degradation: an in vitro and in vivo study. Polymers, Vol. 14, 2022, pp. 3397–3411. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4360/14/16/3397.10.3390/polym14163397Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Liu, X., B. Chen, Y. Li, Y. Kong, M. Gao, L. Z. Zhang, et al. Development of an electrospun polycaprolactone/silk scaffold for potential vascular tissue engineering applications. Journal of Bioactive and Compatible Polymers, Vol. 36, 2020, pp. 59–76.10.1177/0883911520973244Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Chen, H. W. and M. F. Lin. Characterization, biocompatibility, and optimization of electrospun SF/PCL/CS composite nanofibers. Polymers, Vol. 12, 2020, id. 1439.10.3390/polym12071439Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Tham, A. Y., C. Gandhimathi, J. Praveena, J. R. Venugopal, S. Ramakrishna, and S. D. Kumar. Minocycline loaded hybrid composites nanoparticles for mesenchymal stem cells differentiation into osteogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, Vol. 17, 2016, id. 1222.10.3390/ijms17081222Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Fernandes, M. S., E. C. Kukulka, J. R. de Souza, A. L. S. Borges, T. M. B. Campos, G. P. Thim, et al. Development and characterization of PCL membranes incorporated with Zn-doped bioactive glass produced by electrospinning for osteogenesis evaluation. Journal of Polymer Research, Vol. 29, 2022, id. 370.10.1007/s10965-022-03208-xSuche in Google Scholar

[37] Sowmya, B. and P. K. Panda. Electrospinning of poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) and poly ethylene glycol (PEG) composite nanofiber membranes using methyl ethyl ketone (MEK) and N N’-dimethyl acetamide (DMAc) solvent mixture for anti-adhesion applications. Materials Today Communications, Vol. 33, 2022, id. 104718.10.1016/j.mtcomm.2022.104718Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Wang, F., S. Hu, Q. Jia, and L. Zhang. Advances in electrospinning of natural biomaterials for wound dressing. Journal of Nanomaterials, Vol. 2020, 2020, id. 8719859.10.1155/2020/8719859Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Dong, L., L. Li, Y. Song, Y. Fang, J. Liu, P. Chen, et al. MSC-derived immunomodulatory extracellular matrix functionalized electrospun fibers for mitigating foreign-body reaction and tendon adhesion. Acta Biomaterialia, Vol. 133, 2021, pp. 280–296.10.1016/j.actbio.2021.04.035Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Azimi, B., M. Milazzo, A. Lazzeri, S. Berrettini, M. J. Uddin, Z. Qin, et al. Electrospinning piezoelectric fibers for biocompatible devices. Advanced Healthcare Materials, Vol. 9, 2020, id. 1901287.10.1002/adhm.201901287Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Lim, J. S., C. S. Ki, J. W. Kim, K. G. Lee, S. W. Kang, H. Y. Kweon, et al. Fabrication and evaluation of poly (epsilon‐caprolactone)/silk fibroin blend nanofibrous scaffold. Biopolymers, Vol. 97, 2012, pp. 265–275.10.1002/bip.22016Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Zargarian, S. S. and V. Haddadi-Asl. Surfactant-assisted water exposed electrospinning of novel super hydrophilic polycaprolactone based fibers. Artificial Cells, Nanomedicine, and Biotechnology, Vol. 45, 2017, pp. 871–880.10.1080/21691401.2016.1182921Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Wang, Z., X. Song, Y. Cui, K. Cheng, X. Tian, M. Dong, et al. Silk fibroin H-fibroin/poly(ε-caprolactone) core-shell nanofibers with enhanced mechanical property and long-term drug release. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, Vol. 593, 2021, pp. 142–151. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0021979721002514.10.1016/j.jcis.2021.02.099Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Khosravi, A., L. Ghasemi-Mobarakeh, H. Mollahosseini, F. Ajalloueian, M. Masoudi Rad, M. R. Norouzi, et al. Immobilization of silk fibroin on the surface of PCL nanofibrous scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, Vol. 135, 2018, id. 46684.10.1002/app.46684Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Sheikh, F. A., H. W. Ju, B. M. Moon, H. J. Park, J. H. Kim, S. H. Kim, et al. A comparative mechanical and biocompatibility study of poly(ε-caprolactone), hybrid poly(ε-caprolactone)–silk, and silk nanofibers by colloidal electrospinning technique for tissue engineering. Journal of Bioactive and Compatible Polymers, Vol. 29, 2014, pp. 500–514.10.1177/0883911514549717Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Elzein, T., M. Nasser-Eddine, C. Delaite, S. Bistac, and P. Dumas. FTIR study of polycaprolactone chain organization at interfaces. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, Vol. 273, 2004, pp. 381–387.10.1016/j.jcis.2004.02.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Wu, Y., G. Cao, H. Yang, Y. Zhou, X. Liu, and W. Xu. Effects of fabric structures on the mechanical and structural properties of poly(ϵ-caprolactone)/silk fabric biocomposites. Journal of Natural Fibers, Vol. 13, 2016, pp. 1–9.10.1080/15440478.2014.984051Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Review Articles

- Progress in preparation and ablation resistance of ultra-high-temperature ceramics modified C/C composites for extreme environment

- Solar lighting systems applied in photocatalysis to treat pollutants – A review

- Technological advances in three-dimensional skin tissue engineering

- Hybrid magnesium matrix composites: A review of reinforcement philosophies, mechanical and tribological characteristics

- Application prospect of calcium peroxide nanoparticles in biomedical field

- Research progress on basalt fiber-based functionalized composites

- Evaluation of the properties and applications of FRP bars and anchors: A review

- A critical review on mechanical, durability, and microstructural properties of industrial by-product-based geopolymer composites

- Multifunctional engineered cementitious composites modified with nanomaterials and their applications: An overview

- Role of bioglass derivatives in tissue regeneration and repair: A review

- Research progress on properties of cement-based composites incorporating graphene oxide

- Properties of ultra-high performance concrete and conventional concrete with coal bottom ash as aggregate replacement and nanoadditives: A review

- A scientometric review of the literature on the incorporation of steel fibers in ultra-high-performance concrete with research mapping knowledge

- Weldability of high nitrogen steels: A review

- Application of waste recycle tire steel fibers as a construction material in concrete

- Wear properties of graphene-reinforced aluminium metal matrix composite: A review

- Experimental investigations of electrodeposited Zn–Ni, Zn–Co, and Ni–Cr–Co–based novel coatings on AA7075 substrate to ameliorate the mechanical, abrasion, morphological, and corrosion properties for automotive applications

- Research evolution on self-healing asphalt: A scientometric review for knowledge mapping

- Recent developments in the mechanical properties of hybrid fiber metal laminates in the automotive industry: A review

- A review of microscopic characterization and related properties of fiber-incorporated cement-based materials

- Comparison and review of classical and machine learning-based constitutive models for polymers used in aeronautical thermoplastic composites

- Gold nanoparticle-based strategies against SARS-CoV-2: A review

- Poly-ferric sulphate as superior coagulant: A review on preparation methods and properties

- A review on ceramic waste-based concrete: A step toward sustainable concrete

- Modification of the structure and properties of oxide layers on aluminium alloys: A review

- A review of magnetically driven swimming microrobots: Material selection, structure design, control method, and applications

- Polyimide–nickel nanocomposites fabrication, properties, and applications: A review

- Design and analysis of timber-concrete-based civil structures and its applications: A brief review

- Effect of fiber treatment on physical and mechanical properties of natural fiber-reinforced composites: A review

- Blending and functionalisation modification of 3D printed polylactic acid for fused deposition modeling

- A critical review on functionally graded ceramic materials for cutting tools: Current trends and future prospects

- Heme iron as potential iron fortifier for food application – characterization by material techniques

- An overview of the research trends on fiber-reinforced shotcrete for construction applications

- High-entropy alloys: A review of their performance as promising materials for hydrogen and molten salt storage

- Effect of the axial compression ratio on the seismic behavior of resilient concrete walls with concealed column stirrups

- Research Articles

- Effect of fiber orientation and elevated temperature on the mechanical properties of unidirectional continuous kenaf reinforced PLA composites

- Optimizing the ECAP processing parameters of pure Cu through experimental, finite element, and response surface approaches

- Study on the solidification property and mechanism of soft soil based on the industrial waste residue

- Preparation and photocatalytic degradation of Sulfamethoxazole by g-C3N4 nano composite samples

- Impact of thermal modification on color and chemical changes of African padauk, merbau, mahogany, and iroko wood species

- The evaluation of the mechanical properties of glass, kenaf, and honeycomb fiber-reinforced composite

- Evaluation of a novel steel box-soft body combination for bridge protection against ship collision

- Study on the uniaxial compression constitutive relationship of modified yellow mud from minority dwelling in western Sichuan, China

- Ultrasonic longitudinal torsion-assisted biotic bone drilling: An experimental study

- Green synthesis, characterizations, and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles from Themeda quadrivalvis, in conjugation with macrolide antibiotics against respiratory pathogens

- Performance analysis of WEDM during the machining of Inconel 690 miniature gear using RSM and ANN modeling approaches

- Biosynthesis of Ag/bentonite, ZnO/bentonite, and Ag/ZnO/bentonite nanocomposites by aqueous leaf extract of Hagenia abyssinica for antibacterial activities

- Eco-friendly MoS2/waste coconut oil nanofluid for machining of magnesium implants

- Silica and kaolin reinforced aluminum matrix composite for heat storage

- Optimal design of glazed hollow bead thermal insulation mortar containing fly ash and slag based on response surface methodology

- Hemp seed oil nanoemulsion with Sapindus saponins as a potential carrier for iron supplement and vitamin D

- A numerical study on thin film flow and heat transfer enhancement for copper nanoparticles dispersed in ethylene glycol

- Research on complex multimodal vibration characteristics of offshore platform

- Applicability of fractal models for characterising pore structure of hybrid basalt–polypropylene fibre-reinforced concrete

- Influence of sodium silicate to precursor ratio on mechanical properties and durability of the metakaolin/fly ash alkali-activated sustainable mortar using manufactured sand

- An experimental study of bending resistance of multi-size PFRC beams

- Characterization, biocompatibility, and optimization of electrospun SF/PCL composite nanofiber films

- Morphological classification method and data-driven estimation of the joint roughness coefficient by consideration of two-order asperity

- Prediction and simulation of mechanical properties of borophene-reinforced epoxy nanocomposites using molecular dynamics and FEA

- Nanoemulsions of essential oils stabilized with saponins exhibiting antibacterial and antioxidative properties

- Fabrication and performance analysis of sustainable municipal solid waste incineration fly ash alkali-activated acoustic barriers

- Electrostatic-spinning construction of HCNTs@Ti3C2T x MXenes hybrid aerogel microspheres for tunable microwave absorption

- Investigation of the mechanical properties, surface quality, and energy efficiency of a fused filament fabrication for PA6

- Experimental study on mechanical properties of coal gangue base geopolymer recycled aggregate concrete reinforced by steel fiber and nano-Al2O3

- Hybrid bio-fiber/bio-ceramic composite materials: Mechanical performance, thermal stability, and morphological analysis

- Experimental study on recycled steel fiber-reinforced concrete under repeated impact

- Effect of rare earth Nd on the microstructural transformation and mechanical properties of 7xxx series aluminum alloys

- Color match evaluation using instrumental method for three single-shade resin composites before and after in-office bleaching

- Exploring temperature-resilient recycled aggregate concrete with waste rubber: An experimental and multi-objective optimization analysis

- Study on aging mechanism of SBS/SBR compound-modified asphalt based on molecular dynamics

- Evolution of the pore structure of pumice aggregate concrete and the effect on compressive strength

- Effect of alkaline treatment time of fibers and microcrystalline cellulose addition on mechanical properties of unsaturated polyester composites reinforced by cantala fibers

- Optimization of eggshell particles to produce eco-friendly green fillers with bamboo reinforcement in organic friction materials

- An effective approach to improve microstructure and tribological properties of cold sprayed Al alloys

- Luminescence and temperature-sensing properties of Li+, Na+, or K+, Tm3+, and Yb3+ co-doped Bi2WO6 phosphors

- Effect of molybdenum tailings aggregate on mechanical properties of engineered cementitious composites and stirrup-confined ECC stub columns

- Experimental study on the seismic performance of short shear walls comprising cold-formed steel and high-strength reinforced concrete with concealed bracing

- Failure criteria and microstructure evolution mechanism of the alkali–silica reaction of concrete

- Mechanical, fracture-deformation, and tribology behavior of fillers-reinforced sisal fiber composites for lightweight automotive applications

- UV aging behavior evolution characterization of HALS-modified asphalt based on micro-morphological features

- Preparation of VO2/graphene/SiC film by water vapor oxidation

- A semi-empirical model for predicting carbonation depth of RAC under two-dimensional conditions

- Comparison of the physical properties of different polyimide nanocomposite films containing organoclays varying in alkyl chain lengths

- Effects of freeze–thaw cycles on micro and meso-structural characteristics and mechanical properties of porous asphalt mixtures

- Flexural performance of a new type of slightly curved arc HRB400 steel bars reinforced one-way concrete slabs

- Alkali-activated binder based on red mud with class F fly ash and ground granulated blast-furnace slag under ambient temperature

- Facile synthesis of g-C3N4 nanosheets for effective degradation of organic pollutants via ball milling

- DEM study on the loading rate effect of marble under different confining pressures

- Conductive and self-cleaning composite membranes from corn husk nanofiber embedded with inorganic fillers (TiO2, CaO, and eggshell) by sol–gel and casting processes for smart membrane applications

- Laser re-melting of modified multimodal Cr3C2–NiCr coatings by HVOF: Effect on the microstructure and anticorrosion properties

- Damage constitutive model of jointed rock mass considering structural features and load effect

- Thermosetting polymer composites: Manufacturing and properties study

- CSG compressive strength prediction based on LSTM and interpretable machine learning

- Axial compression behavior and stress–strain relationship of slurry-wrapping treatment recycled aggregate concrete-filled steel tube short columns

- Space-time evolution characteristics of loaded gas-bearing coal fractures based on industrial μCT

- Dual-biprism-based single-camera high-speed 3D-digital image correlation for deformation measurement on sandwich structures under low velocity impact

- Effects of cold deformation modes on microstructure uniformity and mechanical properties of large 2219 Al–Cu alloy rings

- Basalt fiber as natural reinforcement to improve the performance of ecological grouting slurry for the conservation of earthen sites

- Interaction of micro-fluid structure in a pressure-driven duct flow with a nearby placed current-carrying wire: A numerical investigation

- A simulation modeling methodology considering random multiple shots for shot peening process

- Optimization and characterization of composite modified asphalt with pyrolytic carbon black and chicken feather fiber

- Synthesis, characterization, and application of the novel nanomagnet adsorbent for the removal of Cr(vi) ions

- Multi-perspective structural integrity-based computational investigations on airframe of Gyrodyne-configured multi-rotor UAV through coupled CFD and FEA approaches for various lightweight sandwich composites and alloys

- Influence of PVA fibers on the durability of cementitious composites under the wet–heat–salt coupling environment

- Compressive behavior of BFRP-confined ceramsite concrete: An experimental study and stress–strain model

- Interval models for uncertainty analysis and degradation prediction of the mechanical properties of rubber

- Preparation of PVDF-HFP/CB/Ni nanocomposite films for piezoelectric energy harvesting

- Frost resistance and life prediction of recycled brick aggregate concrete with waste polypropylene fiber

- Synthetic leathers as a possible source of chemicals and odorous substances in indoor environment

- Mechanical properties of seawater volcanic scoria aggregate concrete-filled circular GFRP and stainless steel tubes under axial compression

- Effect of curved anchor impellers on power consumption and hydrodynamic parameters of yield stress fluids (Bingham–Papanastasiou model) in stirred tanks

- All-dielectric tunable zero-refractive index metamaterials based on phase change materials

- Influence of ultrasonication time on the various properties of alkaline-treated mango seed waste filler reinforced PVA biocomposite

- Research on key casting process of high-grade CNC machine tool bed nodular cast iron

- Latest research progress of SiCp/Al composite for electronic packaging

- Special Issue on 3D and 4D Printing of Advanced Functional Materials - Part I

- Molecular dynamics simulation on electrohydrodynamic atomization: Stable dripping mode by pre-load voltage

- Research progress of metal-based additive manufacturing in medical implants

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Review Articles

- Progress in preparation and ablation resistance of ultra-high-temperature ceramics modified C/C composites for extreme environment

- Solar lighting systems applied in photocatalysis to treat pollutants – A review

- Technological advances in three-dimensional skin tissue engineering

- Hybrid magnesium matrix composites: A review of reinforcement philosophies, mechanical and tribological characteristics

- Application prospect of calcium peroxide nanoparticles in biomedical field

- Research progress on basalt fiber-based functionalized composites

- Evaluation of the properties and applications of FRP bars and anchors: A review

- A critical review on mechanical, durability, and microstructural properties of industrial by-product-based geopolymer composites

- Multifunctional engineered cementitious composites modified with nanomaterials and their applications: An overview

- Role of bioglass derivatives in tissue regeneration and repair: A review

- Research progress on properties of cement-based composites incorporating graphene oxide

- Properties of ultra-high performance concrete and conventional concrete with coal bottom ash as aggregate replacement and nanoadditives: A review

- A scientometric review of the literature on the incorporation of steel fibers in ultra-high-performance concrete with research mapping knowledge

- Weldability of high nitrogen steels: A review

- Application of waste recycle tire steel fibers as a construction material in concrete

- Wear properties of graphene-reinforced aluminium metal matrix composite: A review

- Experimental investigations of electrodeposited Zn–Ni, Zn–Co, and Ni–Cr–Co–based novel coatings on AA7075 substrate to ameliorate the mechanical, abrasion, morphological, and corrosion properties for automotive applications

- Research evolution on self-healing asphalt: A scientometric review for knowledge mapping

- Recent developments in the mechanical properties of hybrid fiber metal laminates in the automotive industry: A review

- A review of microscopic characterization and related properties of fiber-incorporated cement-based materials

- Comparison and review of classical and machine learning-based constitutive models for polymers used in aeronautical thermoplastic composites

- Gold nanoparticle-based strategies against SARS-CoV-2: A review

- Poly-ferric sulphate as superior coagulant: A review on preparation methods and properties

- A review on ceramic waste-based concrete: A step toward sustainable concrete

- Modification of the structure and properties of oxide layers on aluminium alloys: A review

- A review of magnetically driven swimming microrobots: Material selection, structure design, control method, and applications

- Polyimide–nickel nanocomposites fabrication, properties, and applications: A review

- Design and analysis of timber-concrete-based civil structures and its applications: A brief review

- Effect of fiber treatment on physical and mechanical properties of natural fiber-reinforced composites: A review

- Blending and functionalisation modification of 3D printed polylactic acid for fused deposition modeling

- A critical review on functionally graded ceramic materials for cutting tools: Current trends and future prospects

- Heme iron as potential iron fortifier for food application – characterization by material techniques

- An overview of the research trends on fiber-reinforced shotcrete for construction applications

- High-entropy alloys: A review of their performance as promising materials for hydrogen and molten salt storage

- Effect of the axial compression ratio on the seismic behavior of resilient concrete walls with concealed column stirrups

- Research Articles

- Effect of fiber orientation and elevated temperature on the mechanical properties of unidirectional continuous kenaf reinforced PLA composites

- Optimizing the ECAP processing parameters of pure Cu through experimental, finite element, and response surface approaches

- Study on the solidification property and mechanism of soft soil based on the industrial waste residue

- Preparation and photocatalytic degradation of Sulfamethoxazole by g-C3N4 nano composite samples

- Impact of thermal modification on color and chemical changes of African padauk, merbau, mahogany, and iroko wood species

- The evaluation of the mechanical properties of glass, kenaf, and honeycomb fiber-reinforced composite

- Evaluation of a novel steel box-soft body combination for bridge protection against ship collision

- Study on the uniaxial compression constitutive relationship of modified yellow mud from minority dwelling in western Sichuan, China

- Ultrasonic longitudinal torsion-assisted biotic bone drilling: An experimental study

- Green synthesis, characterizations, and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles from Themeda quadrivalvis, in conjugation with macrolide antibiotics against respiratory pathogens

- Performance analysis of WEDM during the machining of Inconel 690 miniature gear using RSM and ANN modeling approaches

- Biosynthesis of Ag/bentonite, ZnO/bentonite, and Ag/ZnO/bentonite nanocomposites by aqueous leaf extract of Hagenia abyssinica for antibacterial activities

- Eco-friendly MoS2/waste coconut oil nanofluid for machining of magnesium implants

- Silica and kaolin reinforced aluminum matrix composite for heat storage

- Optimal design of glazed hollow bead thermal insulation mortar containing fly ash and slag based on response surface methodology

- Hemp seed oil nanoemulsion with Sapindus saponins as a potential carrier for iron supplement and vitamin D

- A numerical study on thin film flow and heat transfer enhancement for copper nanoparticles dispersed in ethylene glycol

- Research on complex multimodal vibration characteristics of offshore platform

- Applicability of fractal models for characterising pore structure of hybrid basalt–polypropylene fibre-reinforced concrete

- Influence of sodium silicate to precursor ratio on mechanical properties and durability of the metakaolin/fly ash alkali-activated sustainable mortar using manufactured sand

- An experimental study of bending resistance of multi-size PFRC beams

- Characterization, biocompatibility, and optimization of electrospun SF/PCL composite nanofiber films

- Morphological classification method and data-driven estimation of the joint roughness coefficient by consideration of two-order asperity

- Prediction and simulation of mechanical properties of borophene-reinforced epoxy nanocomposites using molecular dynamics and FEA

- Nanoemulsions of essential oils stabilized with saponins exhibiting antibacterial and antioxidative properties

- Fabrication and performance analysis of sustainable municipal solid waste incineration fly ash alkali-activated acoustic barriers

- Electrostatic-spinning construction of HCNTs@Ti3C2T x MXenes hybrid aerogel microspheres for tunable microwave absorption

- Investigation of the mechanical properties, surface quality, and energy efficiency of a fused filament fabrication for PA6

- Experimental study on mechanical properties of coal gangue base geopolymer recycled aggregate concrete reinforced by steel fiber and nano-Al2O3

- Hybrid bio-fiber/bio-ceramic composite materials: Mechanical performance, thermal stability, and morphological analysis

- Experimental study on recycled steel fiber-reinforced concrete under repeated impact

- Effect of rare earth Nd on the microstructural transformation and mechanical properties of 7xxx series aluminum alloys

- Color match evaluation using instrumental method for three single-shade resin composites before and after in-office bleaching

- Exploring temperature-resilient recycled aggregate concrete with waste rubber: An experimental and multi-objective optimization analysis

- Study on aging mechanism of SBS/SBR compound-modified asphalt based on molecular dynamics

- Evolution of the pore structure of pumice aggregate concrete and the effect on compressive strength

- Effect of alkaline treatment time of fibers and microcrystalline cellulose addition on mechanical properties of unsaturated polyester composites reinforced by cantala fibers

- Optimization of eggshell particles to produce eco-friendly green fillers with bamboo reinforcement in organic friction materials

- An effective approach to improve microstructure and tribological properties of cold sprayed Al alloys

- Luminescence and temperature-sensing properties of Li+, Na+, or K+, Tm3+, and Yb3+ co-doped Bi2WO6 phosphors

- Effect of molybdenum tailings aggregate on mechanical properties of engineered cementitious composites and stirrup-confined ECC stub columns

- Experimental study on the seismic performance of short shear walls comprising cold-formed steel and high-strength reinforced concrete with concealed bracing

- Failure criteria and microstructure evolution mechanism of the alkali–silica reaction of concrete

- Mechanical, fracture-deformation, and tribology behavior of fillers-reinforced sisal fiber composites for lightweight automotive applications

- UV aging behavior evolution characterization of HALS-modified asphalt based on micro-morphological features

- Preparation of VO2/graphene/SiC film by water vapor oxidation

- A semi-empirical model for predicting carbonation depth of RAC under two-dimensional conditions

- Comparison of the physical properties of different polyimide nanocomposite films containing organoclays varying in alkyl chain lengths

- Effects of freeze–thaw cycles on micro and meso-structural characteristics and mechanical properties of porous asphalt mixtures

- Flexural performance of a new type of slightly curved arc HRB400 steel bars reinforced one-way concrete slabs

- Alkali-activated binder based on red mud with class F fly ash and ground granulated blast-furnace slag under ambient temperature

- Facile synthesis of g-C3N4 nanosheets for effective degradation of organic pollutants via ball milling

- DEM study on the loading rate effect of marble under different confining pressures

- Conductive and self-cleaning composite membranes from corn husk nanofiber embedded with inorganic fillers (TiO2, CaO, and eggshell) by sol–gel and casting processes for smart membrane applications

- Laser re-melting of modified multimodal Cr3C2–NiCr coatings by HVOF: Effect on the microstructure and anticorrosion properties

- Damage constitutive model of jointed rock mass considering structural features and load effect

- Thermosetting polymer composites: Manufacturing and properties study

- CSG compressive strength prediction based on LSTM and interpretable machine learning

- Axial compression behavior and stress–strain relationship of slurry-wrapping treatment recycled aggregate concrete-filled steel tube short columns

- Space-time evolution characteristics of loaded gas-bearing coal fractures based on industrial μCT

- Dual-biprism-based single-camera high-speed 3D-digital image correlation for deformation measurement on sandwich structures under low velocity impact

- Effects of cold deformation modes on microstructure uniformity and mechanical properties of large 2219 Al–Cu alloy rings

- Basalt fiber as natural reinforcement to improve the performance of ecological grouting slurry for the conservation of earthen sites

- Interaction of micro-fluid structure in a pressure-driven duct flow with a nearby placed current-carrying wire: A numerical investigation

- A simulation modeling methodology considering random multiple shots for shot peening process

- Optimization and characterization of composite modified asphalt with pyrolytic carbon black and chicken feather fiber

- Synthesis, characterization, and application of the novel nanomagnet adsorbent for the removal of Cr(vi) ions

- Multi-perspective structural integrity-based computational investigations on airframe of Gyrodyne-configured multi-rotor UAV through coupled CFD and FEA approaches for various lightweight sandwich composites and alloys

- Influence of PVA fibers on the durability of cementitious composites under the wet–heat–salt coupling environment

- Compressive behavior of BFRP-confined ceramsite concrete: An experimental study and stress–strain model

- Interval models for uncertainty analysis and degradation prediction of the mechanical properties of rubber

- Preparation of PVDF-HFP/CB/Ni nanocomposite films for piezoelectric energy harvesting

- Frost resistance and life prediction of recycled brick aggregate concrete with waste polypropylene fiber

- Synthetic leathers as a possible source of chemicals and odorous substances in indoor environment

- Mechanical properties of seawater volcanic scoria aggregate concrete-filled circular GFRP and stainless steel tubes under axial compression

- Effect of curved anchor impellers on power consumption and hydrodynamic parameters of yield stress fluids (Bingham–Papanastasiou model) in stirred tanks

- All-dielectric tunable zero-refractive index metamaterials based on phase change materials

- Influence of ultrasonication time on the various properties of alkaline-treated mango seed waste filler reinforced PVA biocomposite

- Research on key casting process of high-grade CNC machine tool bed nodular cast iron

- Latest research progress of SiCp/Al composite for electronic packaging

- Special Issue on 3D and 4D Printing of Advanced Functional Materials - Part I

- Molecular dynamics simulation on electrohydrodynamic atomization: Stable dripping mode by pre-load voltage

- Research progress of metal-based additive manufacturing in medical implants