Abstract

Tissue engineering is an enabling technology that can be used to repair, replace, and regenerate different types of biological tissues and holds great potential in various biomedical applications. As the first line of defense for the human body, the skin has a complex structure. When skin is injured by trauma or disease, the skin tissues may regenerate under natural conditions, though often resulting in irreversible and aesthetically unpleasant scarring. The development of skin tissue engineering strategies was reviewed. Although the traditional approaches to skin tissue engineering have made good progress, they are still unable to effectively deal with large-area injuries or produce full-thickness grafts. In vitro three-dimensional (3D) skin constructs are good skin equivalent substitutes and they have promoted many major innovative discoveries in biology and medicine. 3D skin manufacturing technology can be divided into two categories: scaffold-free and scaffold-based. The representatives of traditional scaffold-free approaches are transwell/Boyden chamber approach and organotypic 3D skin culture. Because of its low cost and high repeatability, the scaffold-free 3D skin model is currently commonly used for cytotoxicity analysis, cell biochemical analysis, and high-throughput cell function. At present, many drug experiments use artificial skin developed by traditional approaches to replace animal models. 3D bioprinting technology is a scaffold-based approach. As a novel tissue manufacturing technology, it can quickly design and build a multi-functional human skin model. This technology offers new opportunities to build tissues and organs layer by layer, and it is now used in regenerative medicine to meet the increasing need for tissues and organs suitable for transplantation. 3D bioprinting can generate skin substitutes with improved quality and high complexity for wound healing and in vitro disease modeling. In this review, we analyze different types of conventional techniques to engineer skin and compare them with 3D bioprinting. We also summarized different types of equipment, bioinks, and scaffolds used in 3D skin engineering. In these skin culture techniques, we focus on 3D skin bioprinting technology. While 3D bioprinting technology is still maturing and improvements to the techniques and protocols are required, this technology holds great promise in skin-related applications.

1 Introduction

Skin accounts for about 16% of our body weight, and is the largest organ in the human body. The skin consists of two primary layers, i.e., the epidermis and dermis, along with an additional layer called the hypodermis. Each layer has unique structures, compositions, and synergistic functions (Figure 1) [1,2,3]. The epidermis consists of keratinocytes, melanocytes, Langerhans cells, Merkel cells, and inflammatory cells. The epidermis protects the body from external damage, preserves hydration, and maintains temperature regulation [1]. The thickness of the epidermis is different in different parts of the body. The thinnest epidermis is on the eyelid which is about 0.5 mm thick. The thickest epidermis is about 1.5 mm thick which is on the palms or soles [2]. The dermis is a thick layer that consists of fibers and glycosaminoglycans. The thickness of the dermis varies in different parts of the body [3]. On the eyelid, the dermis is about 0.7 mm thick. On the back, the dermis can reach up to 1 cm thick. The dermis contains small-diameter blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, sebaceous glands, sweat glands, hair follicles, arrector pili muscles, nerves, and tactile bodies [1]. The functions of the dermis are skin immune response and wound repair in addition to structural support for the epidermis. Hypodermis contains adipocytes, nerves, and larger diameter blood vessels, and plays the role of storing nutrition and buffering mechanical pressure [4]. The three major cell types used to engineer traditional skin constructs are keratinocytes, melanocytes, and dermal fibroblasts. Keratinocytes and melanocytes are important parts of the epidermis, and dermal fibroblasts reside in the dermis.

![Figure 1

Structure of human skin. The skin layers include epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis (subcutaneous tissue). Reproduced with permission from Yan et al. [1].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2022-0289/asset/graphic/j_rams-2022-0289_fig_001.jpg)

Structure of human skin. The skin layers include epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis (subcutaneous tissue). Reproduced with permission from Yan et al. [1].

Wound care and skin transplantation are the very problems in healthcare all over the world. According to statistics, the world spends more than 25 billion US dollars on skin healing every year [5]. When human skin is severely burned, damaged in a large area, or affected by diseases such as skin cancer and diabetic foot ulcers, the original cellular environment cannot be completely repaired, which makes some skin appendages, such as hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and sweat glands, unable to regenerate [6,7]. Currently, to heal the injured skin, the common treatment is the use of a skin graft, i.e., by transplanting healthy skin to replace the damaged skin area. Skin grafts include autografts, allografts, xenografts, and synthetic tissues [7,8]. The first three are traditional treatment options, and synthetic skin tissues are usually produced in vitro by tissue culture and are the techniques gaining popularity in skin grafting models due to advances in culture and regeneration techniques.

Traditional skin graft methods have certain defects. Autografts are the skin tissues obtained from the same patient. This method can be used for small-scale injuries. For patients with large-scale skin injury, the limited donor tissue availability and weak wound healing ability are major challenges facing the use of autografts [7]. Allografts are skin tissues from other human sources, such as cadavers, for transplantation. Although they are highly compatible, their sources are limited and immune rejection may still occur [9,10]. Xenografts are animal skin tissues for transplantation. Although they have higher availability and good biocompatibility, their drawbacks include immune rejection and risks of infection due to extended healing times and the unique requirements for tissue care and maintenance [7,8].

The emergence of engineered skin constructs offers a promising solution to the significant challenges and demand from the healthcare community, the shortage of donor tissues and the high medical cost associated with skin disease treatment. Artificial skin tissues may be engineered by traditional tissue engineering strategies and 3D bioprinting. Most of the traditional approaches use scaffold-free tissue engineering [11]. Methods of 3D bioprinting mostly employ scaffold-based tissue engineering principles [4]. To move this technology forward, a better understanding of 3D bioprinting is the key to its successful applications in engineering human skin and other tissues.

2 Traditional approaches to tissue engineering

Tissue engineering began in the twentieth century and it is used in regenerative medicine to meet the needs of tissues and organs suitable for transplantation such as skin, vessels, muscles, and cartilage [11]. In order to address the challenges posed by generating human skin models that approach full-thickness reconstructions, skin vascularization is a means by which the research community can begin to address difficulties in both long-term tissue maintenance and also improve future skin engraftment.

DiVito et al. developed an effective way to construct human blood vessels for use in a variety of applications, including human skin and the blood-brain-barrier [12,13,14]. Here modified polyethylene glycol in combination with gelatin-methacrylamide (GelMA) was used as the scaffold for vessel fabrication and the substrate for cell attachment, respectively. The cells for this experiment were endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and human vascular pericytes [13]. During the experiment, endothelial cells can form a monolayer on the lumen wall and remodel the scaffold with human extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, such as collagen and laminin [12]. This experimental approach combines microfluidic technology and 3D biological tissue culture. This tissue system was applied to drug screening and characterization of pathological processes, as a first step toward the creation of organ repair engineering. The blood vessel fabrication conducted by DiVito et al. was an application experiment combining microfluidic technology and 3D biological tissue culture [14]. They use hydrodynamic focusing technology to develop functional, perfusion capable three-dimensional microvessels for blood-brain-barrier. This technology uses fluid dynamics to control the mixing of biomaterials, which can organize living cells into a complex and orderly three-dimensional structure. According to the results, the cultured microvessels have fully developed endothelial cell-lined lumen and astrocytic outgrowth. Therefore, in the future, hydrodynamic focusing technology can promote the manufacture of complete functional microvessels for in vitro research as nerve substitutes.

Roberts et al. designed an inclusive on-chip platform capable of maintaining laminar flow through porous biosynthetic microvessels by coupling tissue engineering with microfluidics and recirculating perfusion [15]. This device can stably infuse a medium containing small molecules of nutrients, drugs, and dissolved gases into the three-dimensional cell cultures. The artificial microvascular tissue cultivated here beings to simulate the complex cell culture environment and mechanical properties, such as pulsed stresses, circular flow, chemical gradients, and advanced developmental processes including neoangiogenesis, tubulogenesis, and anastomosis required of medium-diameter (100–500 µm) vessels such as venules and arterioles. This tissue system can also be applied to bionic systems. Therefore, it is important to introduce microvessels into 3D tissue construction research. At the same time, many future engineering technologies, such as heart or skin culture, can also achieve better development in combination with the microvascular system. One of the difficulties in skin culture is that it is challenging to cultivate sufficient and effective vascularized tissue. Therefore, if the vessel or microvessel systems can be combined with artificial skin, the function of artificial skin will be greatly improved.

Skin is vulnerable and the damage is usually caused by trauma, burns, skin diseases, or skin loss. Skin tissue engineering offers a potential solution to the shortage of skin transplants, tissue engineering has experienced rapid development in the last decade. Traditional approaches to skin tissue engineering mostly use scaffold-free strategies. Scaffold-free 3D engineering constructs are aggregates of cells resulting from the self-assembly of one or more cell types [11,16,17,18]. Researchers usually cultivate tissues or organs in cell culture vessels. The two common techniques for traditional scaffold-free approaches are transwell/Boyden chamber culture and organotypic 3D skin culture (Table 1). The operational steps of the transwell/Boyden chamber approach and organotypic 3D skin culture are similar. The main differences between the two methods are that different cell types and culture media are used (Figure 2).

Advantages and disadvantages of traditional approaches and 3D bioprinting technologies

| Tissue engineering techniques | Examples | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional approaches | Transwell/Boyden chamber approach and organotypic 3D skin culture | Low technical difficulty, low cost, high throughput, and reduced animal experiments | Limitation of lack of some skin structures, low physiological relevance, and poor repeatability |

| 3D bioprinting technologies | Stereolithography (SLA)-based bioprinting; inkjet bioprinting; laser-assisted bioprinting; extrusion-based bioprinting; and electrospinning-based bioprinting | Personalized treatment, precise manufacturing process, can be used for drug and treatment testing, and reduced rejection risks | High cost of equipment and maintenance, limitation of lack of some skin structures, and ethical and legal problems |

![Figure 2

The overview of transwell/Boyden chamber approach protocol. The protocol of the organotypic human skin culture approach is similar to it. The main differences are the cell types and medium for each experiment. Reproduced with permission from Meier et al. [19].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2022-0289/asset/graphic/j_rams-2022-0289_fig_002.jpg)

The overview of transwell/Boyden chamber approach protocol. The protocol of the organotypic human skin culture approach is similar to it. The main differences are the cell types and medium for each experiment. Reproduced with permission from Meier et al. [19].

Reijnders et al. used human TERT-immortalized keratinocytes and fibroblasts to construct human skin equivalents (TERT-HSE) [20]. Their experimental aim was to develop a fully differentiated, healthy, and safe skin equivalent completely constructed from human skin cell lines that could be used for in vitro wound healing tests. The cells they used were primary human epidermal keratinocytes and primary human dermal fibroblasts. They used the organotypic skin culture approach to create the skin equivalents. They examined the function of TERT-HSE under burn and cold injury conditions, followed by immunohistochemical staining, measurement of epithelization, and testing of wound healing. Finally, they observed that TERT-HSE was very similar to normal natural human skin in morphology and proliferation rate. It can also react to the secretion of trauma and inflammatory mediators in a manner similar to primary HSE. After testing, TERT-HSE can re-epithelialize and secrete the medium that helps inflammation wound healing. The new TERT-HSE completely constructed from human cell lines can be used for drug targeting tests and skin chip manufacturing in the future.

Frade et al. in 2015 also used the traditional approaches to create the human skin constructs [21]. This experiment used human organotypic skin explant culture (hOSEC) method to create an artificial skin as a substitute for testing the effectiveness of cosmetics. They conducted an in vitro culture experiment on human skin. After 1, 7, 30, and 75 days of culture, they collected the skin fragments for histomorphological examination (HE staining) analysis and performed immunohistochemical analysis on the 75th day. The artificial skin in this experiment maintained skin features with viable melanocytes, keratinocytes, and dermal fibroblasts. This artificial skin can be used to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of skin-related drugs or cosmetics, and can highlight its advantages in vitro wound healing research. However, a detraction to this skin construct was the lack of complex skin structures, such as corneum, blood vessels, nerves, secretory glands, and hair follicles present in naive human skin.

Traditional modeling methods can produce artificial skin, but this artificial skin is typically incomplete and often not fully representative. The advantages of scaffold-free skin tissue engineering include its low costs and high reproducibility. These limitations will likely affect skin migration, differentiation, and simple long-term durability [4]. Also, the skin tissues produced by scaffold-free methods are usually very thick. Generally, the thickness of the human skin is less than 2 mm. Therefore, the thickness of the artificial skin should not be too different from the thickness of the natural skin [22]. Scaffold-free skin tissue engineering has been used for cytotoxicity analysis and drug testing [23]. The traditional modeling method can model a part of the skin, and it is still a great challenge to produce a model with comparable structural and functional features of the natural skin.

3 3D bioprinting: an emerging tissue engineering technology

At present, due to the increasing demand for organ transplantation, there is a shortage of organ donors all over the world. Although traditional tissue engineering has been widely used in disease research and drug discovery, traditional methods cannot meet the complex spatial structure and cell–cell interaction required by artificial tissues or organs [24]. The development of 3D bioprinting offers a potential solution. In 1984, Charles W. Hull invented the first 3D printer with the stereolithography (SLA) technique [25]. Until 1988, Robert used Hewlett Packard inkjet printer to conduct the deposit cells experiment. Since then, 3D bioprinting technology has become better recognized by the scientific community for its potential value [26]. Compared with the traditional approaches, 3D bioprinting technology can systematically and reproducibly build tissues or organs layer by layer (Table 1).

In the past decade, 3D bioprinting technology has developed rapidly from individual laboratory-specific printers to commercially available equipment available in an off-the-shelf type format [4]. 3D bioprinting normally uses scaffold-based 3D models and cells grow in the presence of supporting scaffolds that are composed of natural, synthetic, or a combination of different polymers. Different biological scaffolds have different effects. Both natural and synthetic polymers play an important role in tissue engineering. In recent years, a variety of polymers have been synthesized to prepare composite polymers for tissue engineering research [4]. A major component of 3D bioprinting is the bioink implemented for the given task because it can affect the development of organ or tissue structures. Different kinds of bioink have different characteristics, so it is very important to choose a suitable bioink for the 3D bioprinting to be completed. 3D bioprinting has the advantage of accurately positioning cells suspended in the bioink layer by layer. It is suitable for the perfusion of gas and nutrients, as well as supporting intercellular and intracellular communication [27]. Therefore, 3D bioprinting technology is becoming a technology well-suited to face these challenges.

To obtain a better understanding of the 3D bioprinting technology, we introduce three different aspects. We compared the commercially available 3D bioprinters and analyzed the specifications of each. We analyzed different types of bioink with their advantages and limitations [28]. We analyzed four basic types of 3D bioprinting technologies with their characteristics [29]. We used representative studies on different types of 3D bioprinting technologies to explain the functions of 3D bioprinting and showed how the 3D bioprinting technologies can be used in skin research or treatment field [30]. The ultimate goal of 3D bioprinting is to use specific materials and cells to imitate natural tissue structure and provide an implant to replace autologous or allogeneic tissue. The final product of bioprinting is used to restore the normal structure and function of complex tissues. It also can be used to reduce our dependency on the use of laboratory animals, such as rodents in developing potential therapeutics [31,32].

3.1 Commercial 3D bioprinter

A commercially available 3D bioprinter is an attractive option for the laboratory seeking to increase the throughput and reproducibility of their experimental models. A 3D bioprinter is a device that can assemble and accurately position biomaterials or cell units through modeling and printing. 3D bioprinters can be used to manufacture cells, biological scaffolds, and tissues and organs [33]. There are many commercially available 3D bioprinters, and they are chosen for different applications based on their features and parameters (Table 2). For those experiments that need to print large-scale organs, such as the liver and kidney, it is best to choose a printer with a large build volume. While those experiments that need accurate printing, such as artificial neural catheter printing, need to choose a printer with higher resolution. One of the most common commercially available 3D bioprinters that balances both high resolution and economic considerations is available via 3D systems. These devices are available in a range of platforms which can include from one to three print heads based on need and complexity. The printer uses extrusion printing technology with a total build volume of 7,020 mm3, and a resolution of 1 µm in the X, Y, and Z dimensions. This bioprinter is very suitable for the research of skin printing, and can perfectly meet various needs.

Commercially available 3D bioprinter with parameters

| 3D printer | Company | Technology | Number of printing heads | Temperature control | Build volume (mm3) | Axis resolution (XYZ in µm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allevi 1, 2, or 3 | 3D systems | Extrusion | 3 | 4–160°C | 90 × 60 × 130 | 1 |

| 3D-Bioplotter | EnvisionTEC, INC. | Extrusion | 2 | −10 to 80°C | 150 × 150 × 150 | 1 |

| R-GEN 200 | RegenHU | Laser-assisted, extrusion | 5 | 4–80°C | 130 × 90 × 65 | Unavailable |

| BioAssemblyBot 400 | Advanced solutions life sciences | Extrusion | Up to 8 BioAssemblyBot tools | 10–60°C | 304.8 × 254 × 177.8 | Unavailable |

| Bio-Architect WS | Regenovo Biotechnology Co. Ltd | Extrusion | 1 | −10 to 260°C | 170 × 170 × 150 | 1 |

| Bio X6 | Cellink | Extrusion | 6 | 4–250°C | 128 × 90 × 90 | 1 |

| Dr. INVIVO 4D6 | Rokit Healthcare | Extrusion | 6 | 4–60°C | 80 × 80 × 80 | 10 |

The bioprinter designed by Advanced Solutions Life Sciences was a frontier. The printer uses extrusion printing technology with a total build volume of more than 136,000 mm3. Therefore, this bioprinter can print large organs like the heart or lung. Unlike other biological printers, this bioprinter has eight BioAssemblyBot hands with printing heads. Besides, this bioprinter can be operated automatically. It can detect tissues over time and provide the biological status of models in a timely manner. This bioprinter has advanced technology, which can carry out independent learning, automatic calibration, and fault analysis. With its large capacity operating platform, this bioprinter will play a good role in the research and application of many large precision organs in the future. In addition to determining the suitability of a given 3D bioprinter, bioinks must also be well matched to the needs of a particular experiment.

3.2 Bioink for tissue engineering

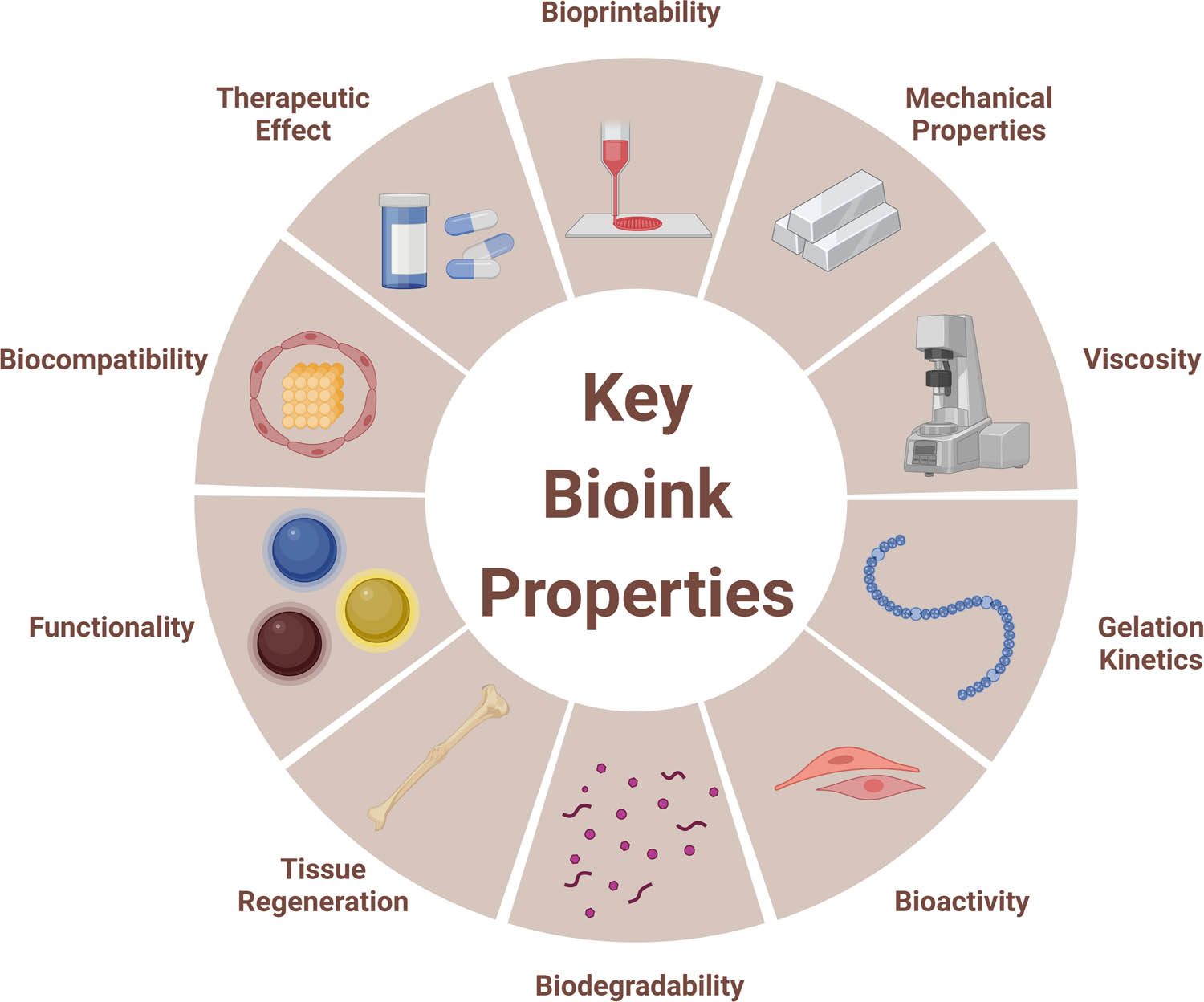

The chosen bioink is a key component for successful bioprinting to obtain optimal results with varying complexities [28]. Bioink is a biomaterial loaded with living cells, which can be used as a raw material or scaffold for 3D bioprinting [34]. The lack of suitable biomaterials for advancing the state of the art in 3D bioprinting is a major limitation and currently restricts the development of this field. Bioink is composed of materials that can be used to encapsulate cells and bind biomolecules [35]. Good bioinks have low toxicity and low immunogenicity and can be biodegradable at a controlled rate. To meet the physiological needs of skin tissue, an ideal bioink should have the following considerations: bioprintability, mechanical properties, viscosity, functionality, bioactivity, biodegradability, tissue regeneration, gelation kinetics, biocompatibility, and therapeutic effect (Figure 3). Bioinks must support the cells and tissues needed for a given tissue construct, and therefore, they must typically retain sufficient mechanical properties. For example, bioinks for bones should be robust and sturdy, while bioinks for skin need to be flexible and elastic. The final applications of bioinks are used in organisms. Excellent bioinks should be able to match organisms well, maintain the activity of living cells or tissues, with limited immune reaction or biological toxicity. In bone, some bioinks play the role of repair, so bioinks need to be able to maintain a good therapeutic effect and can be fully degraded after repair. Bioinks are diverse, and the demand for bioinks depends on different printing methods and application fields [35,36,37]. While comprehensive reviews covering dozens of bioinks and their potential advantages and disadvantages exist [38], this review will focus on a broader discussion on the efficacy of bioinks useful for human skin applications. In tissue engineering, the bioinks can also be known as the scaffolds. The main functions of scaffolds are to provide a support structure, provide mechanical stability, maintain cell viability, ensure cell compatibility and provide physical growth space. The functions of the scaffold are similar to that of the ECM, so an ideal scaffold needs to be the same as the ECM of the target tissue in its natural state. The scaffolds can be divided into porous scaffolds, fibrous scaffolds, microsphere scaffolds, hydrogel scaffolds, acellular scaffolds, and composite scaffolds [39,40]. To achieve these functions, the scaffolds should be safe, stable, bioactive, biocompatible, and permeable [39].

Key properties of the bioink in 3D bioprinting.

3.2.1 Polymers

Biomaterials can be divided into two categories: natural polymer and synthetic polymer (Table 3). Natural polymers are found in nature and can be extracted and purified. Polymers that are widely used for 3D bioprinting include agarose, collagen, hyaluronic acid (HA), alginate, chitosan, and fibrin with varying degrees of success based on the tissue type being investigated [28,41,42].

Advantages and disadvantages for common polymers used in bioprinting

| Bioink type | Polymer | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | Agarose | Good gelation and mechanical properties; high stability; non-toxic crosslinking | Limited by temperature and concentration; not degradable; poor cell adhesion | [28,69] |

| Collagen | Low immunogenicity; high biological relevance | Acid-soluble; difficult to control; requires complex process conditions | [28,43,44] | |

| HA | Good biological relevance; good cytocompatibility; good shear thinning properties | Low mechanical properties; slow gelation behavior | [28,45,46,70] | |

| Alginate | Non-immunogenicity; viscosity is suitable for printing; fast gelation rate | The degradation rate is very slow; lacks shear thinning behavior and rheological properties | [28,48] | |

| Chitosan | Good antibacterial properties; good biodegradability; good biocompatibility | Slow gelation rate; weak mechanical properties | [49,50,51] | |

| Fibrin | Good adhesion; high biological relevance; fast gelation rate | Limited bioprintability | [42,52,53] | |

| Synthetic | PU | Strong mechanical properties and biocompatibility | Requires high process conditions; in vivo stability needs to be enhanced | [55,56,57,71] |

| PEG | Good biocompatibility; non-immunogenicity | Not biodegradable; lacks cell adhesion | [58,59] | |

| PLGA | High strength; high rigidity; good mechanical properties | Low cell adhesion; low proliferation; poor biological activity and induction ability | [60,61,71] | |

| PCL | High strength; high rigidity | Low cell adhesion; low proliferation; weak biodegradable | [62,63,72,73] |

Agaroses are extracted from seaweed. Agaroses have excellent gel forming characteristics and are widely used. The gelation and mechanical properties of this polymer make it particularly useful as a bioink. However, limitations including long thermal gelation and hysteresis behavior persist and can make agarose not suitable for many applications. The limitations allow it to be processed in a limited range of concentration and temperature only [28].

Next we assess collagen-based bioinks, which are naturally derived. Collagen has excellent biocompatibility as a bioink material in 3D bioprinting [43]. However, it is difficult to use collagen directly in 3D bioprinting because of the extended crosslinking of gelatin required by collagen above room temperature. Hence, it is often combined with other materials such as methacrylate to generate gelatin-methacrylate. This chemically crosslinked collagen has higher tensile strength and viscoelastic properties and can be modified to undergo ultra-violet (or blue-light) photo crosslinking abilities which avoid dependency on thermal (temperature-mediated) gelation [28,44].

HA is a natural ECM. HA has advantages in biological relevance, cytocompatibility, and shear-thinning properties. The limitations are its low mechanical properties and slow gelation behavior, so it also needs to be combined with other materials [45,46].

Alginate-based bioinks are cheap, natural bioinks [47]. Alginates are extracted from brown algae [48]. The polymer has been shown to limit the inflammatory response when implanted in vivo. This polymer is one of the most preferred materials in 3D bioprinting with many advantages [28]. The drawbacks include difficulty in attaining a balance between proper shear-thinning qualities and rapid gelation required for medium- to high-speed printing.

Chitosan is a linear polysaccharide prepared by deacetylation of natural chitin [49]. Chitosan has good antibacterial properties, biodegradability, and biocompatibility [50]. Therefore, chitosan is often used as a wound dressing and anti-inflammatory agent. Chitosan has a good effect on the proliferation and adhesion of keratinocytes and fibroblasts. Yet, its mechanical properties are weak and its gelation rate is slow, so chitosan is often used in combination with other polymers in applications [51].

Fibrin is found in blood plasma and fibrinogen can be converted into fibrin by thrombin during clotting. Fibrin has good adhesion and biocompatibility. It can promote cell proliferation and vascularization, so fibrin is often used as a hemostatic agent and acts as a natural scaffold in bioengineering applications [42,52,53].

Synthetic polymers are artificial polymers with adjustable chemical structures and physical properties (Table 3). Most synthetic polymers have super-mechanical properties and are relatively biologically inert. Synthetic polymers have good tensile strength, fracture toughness, and elongation. Synthetic polymers have the advantage of convenient synthesis, easy processing, rich resources, and typically low cost. Therefore, they have great room for development in 3D bioprinting of organs or hard tissue. Commonly used synthetic polymers include polyurethane (PU), polyethylene glycol (PEG), polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA), and polycaprolactone (PCL) [42,54].

PU is a new material produced by polycondensation of isocyanate and liquid polyether or glycol polyester. PU has strong mechanical properties and biocompatibility, so it is often used in biomedical research [55]. The chemical composition of PU will affect its physical and chemical properties. PU can be synthesized with other substances to produce compounds with excellent mechanical properties, degradability, and biocompatibility [56,57].

PEG is a hydrophilic synthetic polymer with a linear and branched structure. It has good biocompatibility and non-immunogenicity. It is a synthetic polymer commonly used in soft tissue repair. However, PEG is not biodegradable and lacks inherent cell adhesion. Therefore, PEG is usually synthesized with other substances [58,59].

PLGA is a polymer produced by the synthesis of lactic acid and glycolic acid [60]. PLGA is widely used as a film, porous scaffold, and hydrogel in the regenerative medicine area. Due to its poor biological activity and induction ability, PLGA is mostly used to print support structures with sufficient mechanical strength to provide a suitable growth environment for cells [61]. However, these disadvantages may be outweighed by the ability of the polymer to degrade at various lengths of time which can be tuned through concentration.

PCL is a biodegradable thermoplastic polymer and its melting point is about 60°C. It can be degraded by ester bond hydrolysis, and the degradation rate is slower than that of many natural polymers [62]. Because PCL has certain requirements for temperature, it is not suitable for many cases of biological transplantation. But for some special cases, such as making bones, PCL is still a good material to choose. PCL is often used in the field of biomedical materials because of its excellent mechanical stability and biocompatibility. PCL can be used to manufacture scaffolds for various tissues, such as bones and nerves. The excellent mechanical properties of PCL enable it to become a stable scaffold and ensure biological activity [63].

Both natural polymer and synthetic polymer can be used to make bioink for artificial skin printing. Collagen is the most commonly used natural polymer for 3D bioprinting. According to the current research data, more than 26% of artificial tissue related experiments use collagen to construct the bioprinting tissue [64]. The earliest 3D bioprinting skin was studied by Lee et al. in 2009. The polymer used in the first 3D printed skin was collagen [65].

Kang et al. created tyramine-conjugated HA and collagen (HA-Tyr/Col-Tyr) hydrogel bioinks [66]. They made HA-Tyr and Col-Tyr polymers separately and then these two kinds of polymers cross-linked together to make HA-Tyr/Col-Tyr polymer. They used normal human dermal fibroblasts and the extrusion-based 3D bioprinter to create the models. Through physical characterization and immunocytochemistry analysis, this kind of bioink had good printing applicability, the structure will not shrink and degrade after 1 day, while it can promote cell metabolism and achieve long-term culture. Therefore, this collagen-based bioink has a good application prospect in skin tissue engineering.

In addition to the bioink prepared from common materials, new biomaterials, such as decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM), have brought a more advanced development direction to the field of bioink. In various printable hydrogels, dECM can support various cells to play a synergistic role at any component by promoting specific physiological characteristics [67].

Kim et al. studied the ability of skin-derived extracellular matrix (S-dECM) bioink in tissue engineering of 3D bioprinting skin [68]. They developed the S-dECM as the novel material for creating bioink. They studied the abilities of S-dECM through skin related in vitro and in vivo applications. Through in vitro analysis, compared with collagen type I, S-dECM bioink had better rheological properties, proliferation, and cell vitality. Through in vivo analysis, compared with the skin equivalent printed with collagen protein, the human skin equivalent printed with S-dECM bioink provided a more stable dermal compartment and improved epidermal tissue. To prove the effect of S-dECM on skin repair, they implanted skin into the back wound of mice and observed it for 8 weeks. The results showed that the bioink based on S-dECM could stimulate the formation of new blood vessels, re-epithelialization, and had significant advantages in the speed of wound healing. Therefore, S-dECM based materials had great potential for skin healing in the clinical field in the future.

3.3 Cells for bioprinting

The cell types commonly used for skin repair in 3D bioprinting include keratinocytes, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, melanocytes, and stem cells [35,74,75]. Fibroblasts and keratinocytes are two kinds of natural skin cells mainly used in bioink at present. Keratinocytes are used to construct the skin surface and replace the missing epidermis. At the same time, keratinocytes can also promote the healing process and help epidermal formation. Fibroblasts are distributed in the lower layer of biological skin structure to simulate the dermis. Moreover, glycosaminoglycans, proteoglycans, and collagen secreted by fibroblasts can restore the damaged tissue structure [76].

Keratinocytes are common cell types in the epidermis, which can initiate the healing process and re-epithelization. Keratinocytes will move from the basement membrane to the stratum corneum during the keratinization. Keratinocytes can synthesize keratin and help to completely close the wound and promote epidermal regeneration during periods of inflammation [77,78].

Fibroblasts exist in the dermis, which can secrete ECM components for the production of ECM and non-fibrous components, and provide structural integrity [79,80]. Fibroblasts are composed of many subtypes with unique phenotypes and functions. Different subtypes play different roles in wound healing and skin regeneration. The biological behaviors of fibroblasts will increase the deposition of collagen in wound tissue, promote the process of wound epithelialization, and shorten the time of wound healing and improve angiogenesis for repair [81,82].

Artificial skin should have various functions and appendages. The endothelium is a thin membrane that can be found in arteries, veins, and capillaries of the skin. Endothelial cells usually play a role in angiogenesis, regulating hemostasis, and can be used for cytokine secretion and cell communication [83,84]. Because angiogenesis plays a key role in skin modeling, endothelial cells are usually used for bioprinting together with other cells like melanocytes.

Melanocytes are cells of neural crest origin which are often used for creating melanin. Melanin is a pigment that mainly affects the color of skin, and it will migrate around keratinocytes to induce pigmentation. Therefore, melanocytes can provide pigment precipitation and protect skin from DNA damage caused by ultraviolet rays. Melanocytes also play a role in immune system modeling, The function of the pigment system can be demonstrated by inducing pigmentation through treatment with known pro-pigmenting molecules, αMSH and forskolin. As the main cell of skin modeling, melanocytes can effectively solve the skin color problem in 3D bioprinting and can be used for studying the role of cell–cell, cell–matrix, and mesenchymal epithelial interactions in controlling skin pigmentation [75,85,86].

The stem cells can also be incorporated in advanced skin tissue constructs and can include: epidermal stem cells (ESCs), adipose-derived stem cells, amniotic fluid-derived stem cells, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), and induced pluripotent stem cells [35]. Different types of stem cells can be used in different areas for 3D bioprinting. For example, ESCs, MSCs, and BMSCs may be used for sweat gland regeneration. Stem cells have shown their potential and role in the field of skin modeling, but the specific mechanism of stem cells in wound healing is not yet fully understood. In the process of using stem cells to culture skin, it is difficult to avoid potential risks such as mutation and tumorigenicity. The ethical challenge surrounding stem cells is also a problem that cannot be ignored at present [35].

At present, many researchers focus on how to develop an effective and safe cell for bioprinting. Baltazar et al. developed a method to culture the xeno-free cells. The cells were used for creating xeno-free dermal and epidermal bioinks to print the skin equivalents [87]. The dermal bioink contained human dermal fibroblasts, human endothelial cells, and human pericytes. The epidermal contained human keratinocytes. The primary human cells in these bioinks were isolated, expanded, and cryopreserved in the absence of xeno-free conditions. The bioinks prepared by xeno-free cells were used to print xeno-free skin equivalents. The bioprinter in this experiment was an extrusion bioprinter (Model BioX; CELLINK). Xeno-free skin grafts were implanted in the back of immunodeficient mice. According to the observation, the researchers found that keratinocytes formed a mature layered epidermis with a reticular ridge structure. After implantation, endothelial cells and pericytes formed human endothelial-cell-lined perfused microvessels in 2 weeks to prevent graft necrosis, and lead to further perfusion of the graft. This study used cells for bioink that were cultured under xeno-free conditions successfully. They had developed a technology that can successfully isolate, culture, and preserve xeno-free primary cells for the development of bioink and scaffold. When the skin equivalents printed by xeno-free bioink were transplanted into the host body, the graft can support vascularized dermis with perfused human endothelial-cell-lined vessels. Therefore, this technology confirmed the practicability of cultivating artificial tissues or organs under strict xeno-free conditions.

4 Nanotechnology

In skin tissue engineering, nanotechnology is mainly used to build scaffolds and add nanoparticles to scaffolds for drug-targeted delivery or treatment assistance [88,89].

Nanofibers are a good nanomaterial for scaffold construction. The structure of nanofibers can well simulate the ultrastructure of natural ECM, so nanofiber scaffolds will strengthen the interaction between cells and the matrix. Nanofibers have good stability and can control the degradation rate, so it is used in skin regeneration and wound dressing [90,91]. Nanofibers can be divided into degradable and nondegradable. The main components of degradable nanofibers are collagen or chitosan and the main components of nondegradable nanofibers are polylactide or polyvinyl alcohol polymers [90]. The technology for making nanofibers is electrospinning, which is a widely used scaffold manufacturing technology. Electrospinning bioprinting technology can create nanofibers for artificial skin. Electrospinning bioprinting has the advantages of easy repeatability, easy manufacturing, and can produce scaffolds with a large surface-to-volume ratio and good pore interconnectivity.

Gao et al. created a flexible bilayered scaffold with a nano structure for building skin substitutes [92]. They used solvent exchange deposition modeling with electrospinning bioprinting technology to build the bilayered scaffold. PLGA was the sub-layer of this scaffold, and nanofibers was upper-layer of this scaffold. They used the bioorthogonal approach to prepare 3,4-dihydroxyphenethylamine-epidermal growth factor (DOPA-EGF) and fix it on the bilayered scaffold. They designed four different groups on the mouse model to determine how different skin printing methods on the scaffold affected wound healing. By observing the situation of the control group, blank group, EGF group, and DOPA group for 21 days, we can find the healing of the wound in the mouse model (Figure 4). By directly observing the wound healing, we can observe the wound on the mouse model (Figure 4c). After 21 days, we can see that the DOPA-EGF group had the best wound healing, and the control group was the worst (Figure 4a). It can also be seen from the wound closure rate data that the DOPA-EGF group has the highest degree of healing (Figure 4b). Images of H&E staining and Masson’s trichrome staining can better analyze wound healing (Figure 4d and e). At 21 days, both images of H&E staining and Masson’s trichrome staining showed the situation of culturing of the artificial skin. There were obvious epidermis and dermis in the images. The skin between different layers was also very complete, and the growth condition was also very close to the natural skin. Therefore, the bilayered scaffold with nano structure made by electrospinning bioprinting has a great effect on wound healing. This special scaffold can enhance the ability of wound healing and effectively treat skin wounds. Thus, this nano-tech bilayered scaffold is a potential candidate for wound care applications.

![Figure 4

(a) Images of wound closure for control group, blank group, EGF group, and DOPA group at day 7, 14, and 21. (b) Wound closure rate for control group, blank group, EGF group, and DOPA group at day 7, 14, and 21. (c) Image of the excisional wound model (scale bar is 5 mm). (d) Images of H&E staining for different groups at day 14 and 21 (magnification is 200×, scale bar is 100 µm). (e) Masson’s trichrome staining for different groups at day 14 and 21 (magnification is 400×, scale bar is 50 µm). Reproduced with permission from Gao et al. [92].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2022-0289/asset/graphic/j_rams-2022-0289_fig_004.jpg)

(a) Images of wound closure for control group, blank group, EGF group, and DOPA group at day 7, 14, and 21. (b) Wound closure rate for control group, blank group, EGF group, and DOPA group at day 7, 14, and 21. (c) Image of the excisional wound model (scale bar is 5 mm). (d) Images of H&E staining for different groups at day 14 and 21 (magnification is 200×, scale bar is 100 µm). (e) Masson’s trichrome staining for different groups at day 14 and 21 (magnification is 400×, scale bar is 50 µm). Reproduced with permission from Gao et al. [92].

The properties of materials will change greatly when their size is reduced to nano-scale, and nano-scale materials will improve the performance of the system to an excellent level. Mixing nanoparticles into scaffolds through nanotechnology can help deliver drugs to tissues and assist in tissue therapy. Gold nanoparticles and silver nanoparticles are commonly used in combination with scaffolds for skin wound treatment. The scaffolds mixed with silver nanoparticles had biocompatibility and can effectively improve the antibacterial ability of artificial tissues [93]. The scaffolds mixed with gold nanoparticles can enhance biocompatibility, oxidation resistance, and enzyme resistance. Due to the physical properties of gold, the mechanical strength of scaffolds containing gold nanoparticles had also been improved [94]. Nanoparticles have many advantages in tissue engineering. They can assist in drug delivery and accelerate wound healing. They can be injected directly into the normal tissue near the damaged part to prevent a direct impact on the wound. They carry out precise regulation and adjust the release curve according to physiological conditions [88,90,91].

Nanotechnology will meet the current difficulties in wound treatment, such as insufficient accuracy of artificial skin preparation, or low drug delivery efficiency. Based on the advantages of nanotechnology in scaffold construction, drug delivery, and treatment, it can be seen that nanotechnology will be more combined with existing tissue engineering technology in the future, and better applied to artificial tissue construction.

5 3D bioprinting technologies for skin

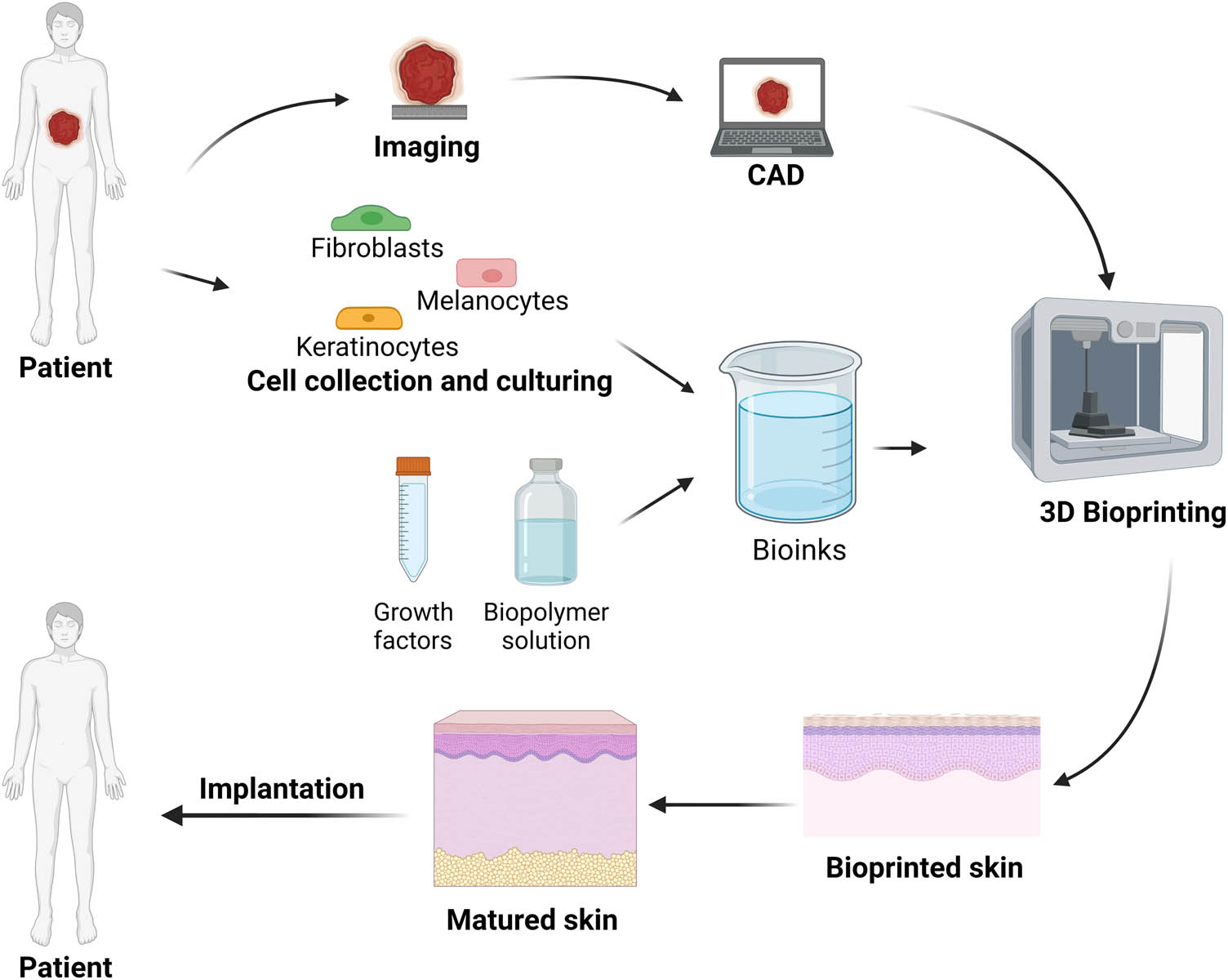

3D skin bioprinting can be divided into three steps, pre-bioprinting, bioprinting, and post-bioprinting (Figure 5). In the pre-bioprinting step, computed tomography and the magnetic resonance imaging are used to analyze the skin tissues. A digital model was then created using a specific modeling method (CAD). In the bioprinting step, the bioink is placed in the printer, and then the bioinks are distributed to the scaffold by printing layer by layer. The post-bioprinting step is to ensure the stability of the printed structure and provide mechanical and chemical stimulation for artificial tissues or organs to control cell growth [83,95].

Schematic of the key steps of 3D bioprinting of skin.

There are five commonly used bioprinting technologies [29] (Figure 6). SLA-based bioprinting originated in 1989 [25]. The two-dimensional pattern of the target is projected onto the bioink reserve, so it is not necessary to move the print head in the XY direction to obtain a complex 3D structure. SLA bioprinting has a high biological printing speed. The bioink cross-linked by light will not produce shear stress on cells, so the cell vitality can reach more than 85%. Complex printing systems limit the development of SLA bioprinting, and special photosensitive bioink makes cell density unable to reach a high level [96].

![Figure 6

Schematic diagram of different 3D bioprinting technologies: (a) SLA-based bioprinting. (b) Inkjet bioprinting with thermal or piezoelectric actuation. (c) Laser-assisted bioprinting. (d) Extrusion-based bioprinting. (e) Electrospinning-based bioprinting. Reproduced with permission from Heinrich et al. [96].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2022-0289/asset/graphic/j_rams-2022-0289_fig_006.jpg)

Schematic diagram of different 3D bioprinting technologies: (a) SLA-based bioprinting. (b) Inkjet bioprinting with thermal or piezoelectric actuation. (c) Laser-assisted bioprinting. (d) Extrusion-based bioprinting. (e) Electrospinning-based bioprinting. Reproduced with permission from Heinrich et al. [96].

The original technique was developed using inkjet printing and works by ejecting small droplets of cells and hydrogel to build up tissues. Under the piezoelectric actuation or thermal actuation, the bioink inside the machine will gradually flow out to the platform. The printing speed is medium to low, though the cell viability is relatively high with average viability of 85%. The resolution is approximately 50 µm [96,97]. This technology has the advantages of a fair degree of printing resolution and simple sample loading requirements. It can also be used to print thermosensitive hydrogels. The disadvantages of this technology are poor mechanical properties, difficulty to print complex structures, and limited materials [98,99].

Laser-assisted bioprinting allows cells and hydrogels to be printed with an accurate resolution and the printing speed is medium. The viability of laser-assisted bioprinting is greater than 85% and the resolution is less than 500 nm making it one of the bioprinting techniques with the highest resolution. The advantages of this technology are its extremely high resolution and a wide range of printable viscosities. However, due to its high cost, low efficiency, and difficulty to combine with a variety of bioactive agents, this technology has not yet gained wide acceptance in the field [96,100].

Extrusion-based technology has different kinds of systems. The two systems for extrusion-based 3D bioprinting are pneumatic-driven and mechanical-driven systems. Pneumatic-driven system is suitable for high-precision biological printing. Mechanical-driven systems are suitable for printing high viscosity materials. Because the pressure at the nozzle outlet decreases rapidly, mechanical-driven systems will be harmful for cells [96]. The type of printing uses pneumatics or piston to continuously squeeze liquid cells-hydrogel solutions through small diameter needles for deposition. The printing speed is slow. The viability is typically 40–80% but the resolution is much better than injecting printing at 1–5 µm [101]. This technology can print complex geometric shapes, combine a variety of biomaterials, and print cells with high viability [102].

Electrospinning-based bioprinting can use polymer, composite materials, and other materials to produce nano and micro fibers. This method uses electricity to quickly stretch the charged polymer solution and spray it out, while collecting the cured filaments into the fiber felt [96]. Because the fiber diameter produced by electrospinning technology is small, this technology can be used as a new method to improve the resolution of the current biological printing platform. Its high-resolution characteristics make it suitable for manufacturing high-resolution scaffolds for cell attachment and long-term culture. The disadvantages of electrospinning technology are that the chaotic agitation of the charged jet will lead to the instability of bioink and fiber structure. Also, the high costs and complex systems limit the development of this technology [96].

These bioprinting technologies can be applied to skin engineering, and are closely related to artificial skin engineering. The various skin bioprinting applications mentioned in this review use different printing technologies. These technologies for skin engineering include soft-lithographic technology, inkjet technology, extrusion-based technology, and electrospinning bioprinting technology [65,66,87,92,103,104,105].

In the current field of regenerative medicine, the most common technology for wound skin care and repair is extrusion-based bioprinting. At the same time, the most widely used technology among commercial bioprinters is extrusion. Extrusion has become the most popular technology in 3D bioprinting for two reasons. The first reason is that this technology appeared very early. Therefore, after a long time of development, this technology is mature enough to be widely used. In 2002, Landers and colleagues designed the first extrusion-based bioprinter. Later, this printing technology became the “3D-Bioplotter” through commercialization [106]. The second reason is that extrusion is a very suitable technology for 3D bioprinting currently. Extrusion technology does not require high costs, and has accessibility and the ability to replicate complex organizations [35]. The bioink related to extrusion-based bioprinting technology is usually composed of natural sources and synthetic materials. This kind of bioink is a mixture of macromolecular polymers with shear thinning characteristics, which can be further cross-linked to ensure product stability [44]. Extrusion-based bioprinting will extrude the bioink into a freely movable platform through the nozzle in the form of a chain through a layer by layer preset way to create a complex 3D structure. Compared with other 3D bioprinting technologies, extrusion-based bioprinting can handle more kinds of biological materials or cell types, and cause relatively less cell damage caused by processes. More importantly, extrusion-based bioprinting can promote cell growth, and even help cells target regeneration [107]. Because of these reasons and advantages, the current extrusion technology has become the most popular technology for commercial printers in the market.

Huyan et al. used the extrusion 3D bioprinter to design and manufacture a double-layer structure model consisting of human dermal fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and microvascular endothelial cells [104]. The cells used in this study were normal human dermal fibroblasts, human dermal microvascular endothelial cells, and normal human epithelial keratinocytes. The extrusion-based 3D bioprinter for the study was customized. This bioprinter was composed of a control system, motion mechanism, and feeding and nozzle system. The bioprinter has four axes, so it can move independently in different directions. The valid printing range of this bioprinter was 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm with repeatable accuracy of 0.05 mm. This bioprinter used a pneumatic pump to extrude bioinks. The artificial skin printed by this technology on mice models was observed to have a cell survival rate of more than 90%. The printed double-layer structure was conducive to skin wound healing and had obvious advantages of microvascular regeneration.

In addition to the extrusion-based 3D bioprinting technology, another technology often used in the field of skin engineering is the laser-assisted bioprinting technology. This technology mainly uses ultraviolet or near ultraviolet nanosecond laser as energy to print bioink. Also, its resolution can be up to picometer level and could accurately locate different cell types in three-dimensional space. As a new generation of biological printing technology, many 3D bioprinters, such as R-GEN 200 bioprinter from RegenHU, have started to use this technology. Researchers have demonstrated that it is feasible to print skin using laser-assisted bioprinting technology. Michael et al. used laser-assisted bioprinting technology to create skin substitutes in the back skin fold chamber of mice [105]. In this experiment, they selected NIH3T3 fibroblasts and HaCaT keratinocytes as the materials to culture skin equivalents. They used the dorsal skin fold chamber of mice to evaluate the skin structure. After 11 days of observation, the skin printed by laser-assisted bioprinting technology formed a tissue very similar to the natural skin. By analyzing the characteristics of printed skin tissue in vivo and in vitro, they found that this artificial skin equivalent can form 3D tissue similar to natural skin. This study provides a multi-layer, fully cellular skin equivalent that can be used for burn treatment.

6 Applications of 3D bioprinting in skin-related research

3D skin printing technology has a wide range of applications. At present, the two major applications of artificial skin are to supplement the use of animal models for pathological and drug research and as the skin substitute for wound reconstruction or cosmetology.

6.1 Disease modeling and drug testing

The animal model is an effective method for modern medicine to analyze pathology and drug action. The disadvantages of animal models are high cost and poor repeatability, so it is a good way to use artificial tissue to replace animal models for pathological and drug experiments.

In 2009, Lee et al. proposed a method to create artificial skin with a multi-layer tissue structure. The printing method they used was the soft-lithographic method. Lee and coworkers mixed the collagen hydrogel precursor, fibroblasts, and keratinocytes together as the bioink [65]. After 8 days of culture and observation of the printed skin, they observed that the cell density of the skin construct was very ideal. At the same time, the epidermis and dermis of the skin construct can be clearly observed. The defect of the artificial skin constructed in this experiment was that the activity of the skin construct was relatively low, and the printing resolution was insufficient. While skin printed using this technique can be used for surgical transplantation, these defects can likely be resolved in future refinements to the technique. This skin construct has the advantages of easy production and low printing difficulty. From the results, it is feasible to use designated cells for organ type skin tissue print culture. The artificial skin tissue produced by this printing method can be applied to disease modeling and drug testing analysis [65].

The study by Lee and colleagues used extrusion bioprinting technology to create the artificial skin [30]. The study used an Allevi bioprinter. The cell types of this study are fibroblasts and keratinocytes, while bioink is collagen hydrogel. Printed skin is cultured under submerged conditions for a week and grown in the air–liquid interface for one more week. The morphology of the resulting skin construct was then assessed using hematoxylin and eosin staining. On day 7, the epidermis has about three cell layers and the dermis is relatively loose but well defined. By day 14, the epidermis becomes denser containing approximately five cell layers and the dermis becomes more compact, as expected. Compared to human skin tissues, this model lacks a well-defined stratum corneum; however, some linear, elongated cells were observed in the outermost portion of the epidermis which indicates that the stratum corneum may be beginning to fully develop. The skin constructs established in this way has a complex skin secondary structure, which can be well applied to the study of skin diseases. The skin printed by 3D bioprinting technology is more accurate and the structure is more complex. Through the characterization data, this artificial skin construct may be able to be used in skin-related diseases such as psoriasis, vitiligo, atopic dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, and skin malignancies [30].

Kim et al. constructed an in vitro skin equivalent for type 2 diabetes [103]. The traditional way of drug development for type 2 diabetes was to use animal models. However, animal models had many inevitable problems. Therefore, this study used 3D bioprinting to create an artificial skin model for type 2 diabetes research. They simulated the skin of patients with type 2 diabetes through 3D cell printing of the main skin layer with physiological phenomena in natural patient skin. The cells in this study were mainly from ordinary human cells and cells isolated from diabetic type 2 donors. They used inkjet and extrusion-based technologies to create the skin models. They added perfusion vascularized subcutaneous tissue of diabetes through 3D printing to make the structure of artificial skin equivalent or more similar to that of diabetic skin model and let the characteristics of diabetic skin become more significant. According to observation, slow re-epithelization, adipocyte hypertrophy, and inflammatory reaction had occurred in the artificial diabetes models. Those characteristics were the representative signs of diabetic skin. Through the application of experimental drugs, they proved that this artificial skin disease model can be used for drug development analysis. In the future, the use of 3D bioprinting to produce skin disease models in vitro will become a development direction of 3D bioprinting.

6.2 Skin regeneration and cosmetology

Printing the skin in vitro and then transplanting it to the injured areas or in situ 3D bioprinting are two technologies for the treatment of skin trauma. In vitro printing technology is the method that is more used in skin surgery.

In situ 3D bioprinting is another leading application direction of 3D skin bioprinting for wound treatment. In situ 3D bioprinting is an emerging technique for 3D skin printing which can print bioinks directly into the defect areas. Unlike other in vitro culture techniques, it directly prints the skin on the wound [108,109,110].

Hakimi et al., in 2018, designed a handheld skin bioprinter that can form skin tissue in situ [111]. They conducted in vivo experiments in mice. Then, in vitro experiments were carried out to verify the efficacy of this artificial skin. The feasibility of this technique can be well demonstrated by detecting cell viability, and cell deposition and comparing the wound recovery after treatment. The degree of skin tissue formation and re-epithelization for the treatment group and the control group proved that this technology is useful. Through different experimental results, we know that skin 3D bioprinting technologies do have higher accuracy and diversity. This advanced technology can gradually replace the traditional methods. However, the generation of epidermal cells is still a huge problem for 3D artificial skin. At present, no matter what method is used, artificial skin still cannot achieve the same structure as organic/naturally derived skin. In situ bioprinting technology is an important breakthrough. This technology makes 3D bioprinting simple and convenient. The printer used in this technology is portable, so it cannot be applied to some complex situations. Furthermore, as an emerging technology, this printing method still has room for development.

Zhao et al. combined platelet rich plasma (PRP) and alginate gelatin (AG) to prepare a composite hydrogel bioink, and evaluated its biological effects in vitro and in vivo. To simulate dermis and epidermis in skin substitutes, they chose dermal fibroblasts and ESCs as seed cells (Figure 7a) [112]. The bioprinter for this experiment used extrusion bioprinting technology for in situ printing (Figure 7b and c). They used the mouse as the animal model. They set up three groups, the control group, AG group, and AG-5P (AG with 5% PRP) group, under different conditions. After 21 days of observation, they compared the data of the three groups and found that AG-5P group had great advantages for wound healing. Through visual images, AG-5P group had the best wound closure at 21 days (Figure 7d). At the same time, after 21 days, the wound diameter and area of AG-5P group were the smallest (Figure 7e and f). HE staining was performed to evaluate the length of the remaining epithelial space, which also confirmed that AG-5P group can form the most complete epithelial tissue and has the fastest wound closure speed (Figure 7g and h). In conclusion, the AG-based bioink mixed with PRP of appropriate concentration can effectively enhance biological activity. This compound bioink can promote important physiological processes, such as ECM synthesis and angiogenesis. Combined with in situ printing technology, this treatment method can be applied to clinical practice. This technique can provide a new clinical treatment method for in situ wound repair during surgery.

![Figure 7

(a) Schematic diagram of bioprinting process using PRP containing different component bioink. (b) Image of the in vitro extrusion-based bioprinting equipment. (c) Image of the robotic arm-based equipment for in situ bioprinting. (d) Images of wound closure for control group, AG group, and AG-5P group in 21 days (scale bar is 5 mm). (e) Images of wound closure in 21 days. Different colors represent the wound size at different times. (f) The wound area changes in 21 days. (g) Images of HE staining of the wound on day 21. (h) Quantitative results within 21 days. Reproduced with permission from Zhao et al. [112].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2022-0289/asset/graphic/j_rams-2022-0289_fig_007.jpg)

(a) Schematic diagram of bioprinting process using PRP containing different component bioink. (b) Image of the in vitro extrusion-based bioprinting equipment. (c) Image of the robotic arm-based equipment for in situ bioprinting. (d) Images of wound closure for control group, AG group, and AG-5P group in 21 days (scale bar is 5 mm). (e) Images of wound closure in 21 days. Different colors represent the wound size at different times. (f) The wound area changes in 21 days. (g) Images of HE staining of the wound on day 21. (h) Quantitative results within 21 days. Reproduced with permission from Zhao et al. [112].

7 Future perspectives

Compared with traditional methods, 3D bioprinting has the advantages of high-throughput output, improved reproducibility, shortened implementation time, high resolution, and flexible operation. The limitations of 3D skin bioprinting lie in the current technical difficulty and high cost. For the technical difficulty, like those studies discussed in this review, although many of the skin constructs have developed secondary structures of the skin, compared with natural human skin, some complex parts cannot be completely restored. How to form blood vessels, nerves, and complex skin appendages, such as stratum corneum and hair follicles, are common difficulties in skin tissue engineering which remains a significant hurdle to overcome. Blood vessels and nerves, are integral components of artificial skin. However, the current technology cannot build useful nerves and blood vessels. The skin transplanted to animals or humans is more akin to a skin-like patch than a fully-functional graft. The reason for this is that the blood vessels and nerves of the artificial skin cannot be well connected with the original parts of the human body, so the artificial skin cannot grow well on the wound. Because 3D bioprinting technology has not been widely popularized and applied, the price of 3D bioprinters or materials used for 3D bioprinting has been relatively high, yet is experiencing a more attainable trajectory. The development of bioink is still facing several challenges for future 3D bioprinting applications. The current bioink cannot satisfy the needs of the ideal 3D bioprinting. There is still a lack of stable, safe, and effective bioink in the field of tissue engineering research. For example, the current bioink is too directional, and different bioinks need to be used in different areas. At the same time, different bioprinting technologies need different bioinks. The bioink for inkjet technology cannot be used with SLA technology. Due to the unique physical characteristics of human skin, the bioink used for bioprinting should have tissue compatibility, and its physical characteristics will not be weakened or changed after printing. One way to solve this problem is to add nanoparticles to the bioink. This can effectively improve the biological regeneration and physical stability of the bioink, yet more work is needed in this regard. Also, we need to consider how to reduce the technical difficulty of 3D bioprinting, so that 3D bioprinters and consumables can be produced more easily. In addition to developing high-quality bioinks, improving the bioprinters themselves can also reduce costs and technical difficulties. In situ bioprinting technology is a viable direction for tissue bioprinting engineering, but can be further optimized by improving the ease of use for the printer. The portable in situ printer can be used in many complex situations, such as field surgery or emergency treatment. In situ printing technology can not only be applied to skin but with the improvement in this technology, in the future, in situ printing technology can be developed to be used in organ repair and limb repair. In addition, artificial intelligence technology can also be combined with bioprinters. Artificial intelligence can help analyze the wound condition and observe the wound treatment in real time through high-resolution scanning. Through the analysis of artificial intelligence, 3D bioprinters can more effectively select bioinks or bioprinting technologies for treatment. Accurate analysis and selection of treatment methods can make 3D bioprinting technology possible for personalized treatment, and also improve the efficiency and safety of treatment. The artificial intelligence 3D bioprinter reduces the dependence on people. Therefore, the 3D bioprinting will become more convenient and simpler in terms of technology. At the same time, it can reduce labor cost and avoid errors caused by manual operation. From now on, 3D bioprinting technology will become more mature, and many amazing technologies such as in situ bioprinting will be derived.

8 Conclusion

This review analyzed different approaches to produce human skin equivalents, from conventional cultures to 3D bioprinting technologies. The traditional approaches, such as the transwell/Boyden chamber approach and organotypic 3D skin culture, are mature and have long been used to create skin constructs. However, the difference in structural and functional characteristics between artificial skin and natural skin is also a problem we need to face. Some key skin structures such as blood vessels, stratum corneum, and nerves are difficult to form in artificial skin. In the future, the new skin tissue culture method represented by 3D bioprinting technology will be widely used in medical research. In situ bioprinting, as a distinctive form of 3D bioprinting, represents a promising direction for the future development of 3D bioprinting. The emergence of this technology makes 3D bioprinting more versatile and brings it closer to point-of-care applications, making it especially advantageous in emergency care. We expect exciting developments in this novel 3D bioprinting technology, which will greatly extend the future applications, particularly bench-to-bedside translation, of 3D bioprinted skin constructs.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Runxuan Cai: organization, investigation, and writing – original draft; Kyle A. DiVito: investigation, writing – review and editing, and supervision; Shuguang Bi: validation and supervision; Naroa Gimenez-Camino: paper-reviewing; Ming Xiao: paper-reviewing. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable for this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

[1] Yan, W.-C., P. Davoodi, S. Vijayavenkataraman, Y. Tian, W. C. Ng, J. Y. H. Fuh, et al. 3D bioprinting of skin tissue: from pre-processing to final product evaluation. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, Vol. 132, 2018, pp. 270–295.10.1016/j.addr.2018.07.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Lai-Cheong, J. E. and J. A. McGrath. Structure and function of skin, hair and nails. Medicine, Vol. 49, No. 6, 2021, pp. 337–342.10.1016/j.mpmed.2021.03.001Search in Google Scholar

[3] Gao, C., C. Lu, Z. Jian, T. Zhang, Z. Chen, Q. Zhu, et al. 3D bioprinting for fabricating artificial skin tissue. Colloids and Surfaces, B: Biointerfaces, Vol. 208, 2021, id. 112041.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2021.112041Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Randall, M. J., A. Jüngel, M. Rimann, and K. Wuertz-Kozak. Advances in the biofabrication of 3D skin in vitro: healthy and pathological models. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, Vol. 6, 2018, id. 154.10.3389/fbioe.2018.00154Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Maniţă, P. G., I. García-Orue, E. Santos-Vizcaíno, R. M. Hernandez, and M. Igartua. 3D bioprinting of functional skin substitutes for chronic wound treatment: from current achievements to future goals. Pharmaceuticals, Vol. 14, 2021, id. 362.10.2139/ssrn.3751557Search in Google Scholar

[6] Trabosh, V. A., A. Daher, K. A. Divito, K. Amin, C. M. Simbulan-Rosenthal, and D. S. Rosenthal. UVB upregulates the bax promoter in immortalized human keratinocytes via ROS induction of Id3. Experimental Dermatology, Vol. 18, No. 4, 2009, pp. 387–395.10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00801.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Tavakoli, S. and A. S. Klar. Bioengineered skin substitutes: advances and future trends. Applied Sciences, Vol. 11, No. 4, 2021, id. 1493.10.3390/app11041493Search in Google Scholar

[8] Lima-Junior, E. M., M. O. de Moraes Filho, B. A. Costa, F. V. Fechine, M. E. A. de Moraes, F. R. Silva-Junior, et al. Innovative treatment using tilapia skin as a xenograft for partial thickness burns after a gunpowder explosion. Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Vol. 6, 2019, pp. 1–4.10.1093/jscr/rjz181Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Gupta, S., D. Mohapatra, R. Chittoria, E. Subbarayan, S. Reddy, V. Chavan, et al. Human skin allograft: is it a viable option in management of burn patients? JCAS, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2019, pp. 132–135.10.4103/JCAS.JCAS_83_18Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Wang, C., F. Zhang, and W. C. Lineaweaver. Clinical applications of allograft skin in burn care. Annals of Plastic Surgery, Vol. 84, No. 3S, 2020, pp. S158–S160.10.1097/SAP.0000000000002282Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Ng, W. L., J. T. Z. Qi, W. Y. Yeong, and M. W. Naing. Proof-of-concept: 3D bioprinting of pigmented human skin constructs. Biofabrication, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2018, id. 025005.10.1088/1758-5090/aa9e1eSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] DiVito, K. A., M. A. Daniele, S. A. Roberts, F. S. Ligler, and A. A. Adams. Microfabricated blood vessels undergo neoangiogenesis. Biomaterials, Vol. 138, 2017, pp. 142–152.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.05.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] DiVito, K. A., M. A. Daniele, S. A. Roberts, F. S. Ligler, and A. A. Adams. Data characterizing microfabricated human blood vessels created via hydrodynamic focusing. Data in Brief, Vol. 14, 2017, pp. 156–162.10.1016/j.dib.2017.07.011Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] DiVito, K. A., J. Luo, K. E. Rogers, S. Sundaram, S. Roberts, B. Dahal, et al. Hydrodynamic focusing-enabled blood vessel fabrication for in vitro modeling of neural surrogates. Journal of Medical and Biological Engineering, Vol. 41, No. 4, 2021, pp. 456–469.10.1007/s40846-021-00629-9Search in Google Scholar

[15] Roberts, S. A., K. A. DiVito, F. S. Ligler, A. A. Adams, and M. A. Daniele. Microvessel manifold for perfusion and media exchange in three-dimensional cell cultures. Biomicrofluidics, Vol. 10, No. 5, 2016, id. 054109.10.1063/1.4963145Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Vu, B., G. R. Souza, and J. Dengjel. Scaffold-free 3D cell culture of primary skin fibroblasts induces profound changes of the matrisome. Matrix Biology, Vol. 11, 2021, id. 100066.10.1016/j.mbplus.2021.100066Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Bacakova, M., J. Musilkova, T. Riedel, D. Stranska, E. Brynda, M. Zaloudkova, et al. The potential applications of fibrin-coated electrospun polylactide nanofibers in skin tissue engineering. International Journal of Nanomedicine, Vol. 11, 2016, pp. 771–789.10.2147/IJN.S99317Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Seol, Y.-J., H.-W. Kang, S. J. Lee, A. Atala, and J. J. Yoo. Bioprinting technology and its applications. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Vol. 46, No. 3, 2014, pp. 342–348.10.1093/ejcts/ezu148Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Meier, F., M. Nesbit, M.-Y. Hsu, B. Martin, P. Van Belle, D. E. Elder, et al. Human melanoma progression in skin reconstructs: biological significance of bFGF. American Journal of Pathology, Vol. 156, No. 1, 2000, pp. 193–200.10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64719-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Reijnders, C. M. A., A. van Lier, S. Roffel, D. Kramer, R. J. Scheper, and S. Gibbs. Development of a full-thickness human skin equivalent in vitro model derived from TERT-immortalized keratinocytes and fibroblasts. Tissue Engineering. Part A, Vol. 21, No. 17–18, 2015, pp. 2448–2459.10.1089/ten.tea.2015.0139Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Frade, M. A., T. A. Andrade, A. F. Aguiar, F. A. Guedes, M. N. Leite, W. R. Passos, et al. Prolonged viability of human organotypic skin explant in culture method (hOSEC). Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia, Vol. 90, No. 3, 2015, pp. 347–350.10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153645Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Wong, R., S. Geyer, W. Weninger, J.-C. Guimberteau, and J. K. Wong. The dynamic anatomy and patterning of skin. Experimental Dermatology, Vol. 25, No. 2, 2016, pp. 92–98.10.1111/exd.12832Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Vidal Yucha, S. E., K. A. Tamamoto, H. Nguyen, D. M. Cairns, and D. L. Kaplan. Human skin equivalents demonstrate need for neuro-immuno-cutaneous system. Advanced Biosystems, Vol. 3, No. 1, 2019, id. 1800283.10.1002/adbi.201800283Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Bom, S., A. M. Martins, H. M. Ribeiro, and J. Marto. Diving into 3D (bio)printing: a revolutionary tool to customize the production of drug and cell-based systems for skin delivery. International Journal of Phamaceutics, Vol. 605, 2021, id. 120794.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120794Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Li, B., W. Qi, and Q. Wu. Research progress of carbon materials in the field of three-dimensional printing polymer nanocomposites. Nanotechnology Reviews, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2022, pp. 1193–1208.10.1515/ntrev-2022-0051Search in Google Scholar

[26] Klebe, R. J. Cytoscribing: a method for micropositioning cells and the construction of two- and three-dimensional synthetic tissues. Experimental Cell Research, Vol. 179, No. 2, 1988, pp. 362–373.10.1016/0014-4827(88)90275-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed