Abstract

Thermal modification is an environment-friendly technology for improving various wood properties, especially the dimensional stability, decay resistance, and color homogeneity. In this work, four tropical wood species (African padauk, merbau, mahogany, and iroko) were thermally modified by the ThermoWood process. The influence of heat treatment on the color and chemical changes of wood was studied by spectrophotometry, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, and wet chemistry methods. As the temperature increased, a decrease in lightness (L*) and a simultaneous decrease in chromatic values (a*, b*) were observed, indicating darkening and browning of the wood surface. As a result of the heat treatment, the relative content of hemicelluloses decreased the most in merbau and mahogany, while the thermal stability of iroko and African padauk was higher. All examined wood species showed a strong correlation between the lightness difference value (ΔL*) and the content of hemicelluloses (r = 0.88–0.96). The FTIR spectroscopy showed that the breakdown of C═O and C═C bonds in hemicelluloses and lignin plays an important role in the formation of chromophoric structures responsible for the color changes in the wood.

1 Introduction

Wood, a biobased material, composed of cellulose, hemicelluloses, lignin, and extractives, is widely applied for indoor and outdoor purposes. Because of this nature, the wood is sensitive to natural decompositions. For some applications, e.g., furniture, cladding, flooring, the color is a very important parameter; however, it is sensitive to light, heat, and moisture. It is a great challenge for wood scientists to preserve this excellent color harmony of wood [1,2]. Various chemical and physical processes are used to improve wood durability, wettability, discoloration, and color homogeneity. The ThermoWood process is an environmentally friendly and rapidly developing wood treatment technology, and it can contribute to mitigating climate change and promoting sustainable development by reducing energy intake, carbon footprint reduction, solid and volatile emissions reducing pollution, and ecosystem damage [3,4]. In this process, the wood darkens due to chemical changes in the main wood components and in the extractives, and simultaneously color variations are equalized. The predominant wood species treated by the ThermoWood process are coniferous, e.g., spruce and pine, or light-colored deciduous wood species, e.g., birch, oak. The typical dark tones of these heat-treated wood species increase their economic value. Typical treatment temperatures in the ThermoWood process are approximately 160 to 210°C. In this region, oak samples showed smaller color changes than spruce ones at all temperature values [5]. Chemical and color changes of Norway spruce and European silver fir were evaluated at temperatures up to 280°C [6,7]. Obtained results show the strong relationship between chemical changes and darkener in both wood species. The darker color of heat-treated wood was attributed to the formation of degradation products from hemicelluloses, changes in extractives, and the formation of oxidation products. Similar findings during the thermal treatment have been reported for birch, black locust, beech, and oak wood, respectively [8,9,10,11].

For darker tropical wood species, the color changes are smaller, and the main purpose of color modifications is its homogeneity, especially between sapwood and heartwood. This is probably why less attention has been paid to this topic, and thus, reported results are quite rare. The decrease in teak and meranti wood lightness was observed in thermally treated wood, and meranti showed a greater drop of lightness in comparison to teak wood [12,13]. Oak, spruce, and meranti wood species thermally treated at 160, 180, 200, and 220°C showed the decrease in lightness; however, the overall color change was different for each wood species – the smallest for meranti and the largest for spruce [14]. Brachystegia spiciformis and Julbernardia globiflora woods were thermally treated at three different temperatures (215, 230, and 245°C) for 2 h. The results show that the originally light-colored sapwood of both wood species darkened gradually as the intensity of thermal modification increased [15].

Exotic wood species are used to produce high-quality furniture but, sometimes, boards from the same species have a very different color, which is disadvantageous. With heat treatment, these differences are mitigated. The change in color following the heat treatment has been attributed to numerous factors, all of them linked to chemical changes due to thermal degradation (formation of colored degradation products from hemicelluloses, changes in extractives, formation of oxidation products, such as quinines, etc.) [16].

Even though it is quality material, the behavior of the market is different from our logic. The demands of customers, the activities of producers and sellers, the effort to establish themselves on the market, as well as legislative measures often influence the methods of processing materials. In the search for alternative types of materials, concepts such as recycling and upcycling are increasingly opened and used in wood processing. All types of materials will enter the recycling process and will be delivered, regardless of what we considered in the past to be more or less quality material. They appeared and are used as old wood. Old wood is not used as fuel for weapons, but it is an irreplaceable material source for new types of materials. Our results provide data with valuable information about the properties that will influence the new products forming the output of this process in the application sphere.

In contrast to the color changes in temperate wood species during thermal treatment, the effect of the ThermoWood process on exotic woods has not been enough studied. The aim of this article is therefore to determine the effect of the thermal modification temperature on color changes and the chemical composition of four wood species in terms of their exterior and interior use.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

The experiment consisted of two basic sets of test samples: African padauk (Pterocarpus soyauxii) (Cameroon), merbau (Intsia bijuga) (Papua New Guinea), mahogany (Entandrophragma utile) (Nigeria), and iroko (Milicia excelsa) (Republic of the Congo). Each set was divided into subsets according to the thermal modification temperature (20 untreated, 160, 180, and 210°C) and consisted of ten 100 mm × 20 mm × 200 mm (tangential × radial × longitudinal) samples. These samples were conditioned (relative humidity (RH) = 65 ± 3% and temperature = 20 ± 2°C) for more than 6 months to achieve an equilibrium moisture content (EMC) of 12 ± 1%. EMC was calculated according to Mitchel [17]. Heartwood samples were always used for all experiments.

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Thermal modification

The wood samples were modified in the thermal chamber, type S400/03 (LAC Ltd., Rajhrad, Czech Republic) according to the ThermoWood process at 160, 180, and 210°C [5]. The thermal modification was performed in three steps. In the first phase, heating was carried out to the temperature corresponding to the individual degrees of thermal modification (160, 180, and 210°C); this phase varied in time within the individual wood species. After the end of this phase, the phase of thermal modification occurred, which lasted 3 h for all degrees of thermal modification. After finishing this phase, the cooling phase starts, ensuring controlled cooling and re-moistening to achieve moisture in the wood in the range of 5–7%.

2.2.2 Chemical analyses

Samples were disintegrated into sawdust, and fractions from 0.5 to 1.0 mm in size were used for carrying out chemical analyses. According to ASTM D1107-21 [18], the extractives content was determined in a Soxhlet apparatus with a mixture of absolute ethanol for analysis (Merck, Germany) and toluene for analysis (Merck, Germany) (1.0/0.427, v/v). The duration of extraction was 8 h with six siphoning’s per hour. The lignin content was determined according to Sluiter et al. [19], the cellulose according to the method by Seifert [20], and the holocellulose according to Wise et al. [21]. Hemicelluloses were calculated as a difference between the holocellulose and cellulose contents. Measurements were performed on four replicates per sample. The results were presented as oven-dry weight (odw) per unextracted wood.

2.2.3 Color measurement

After thermal modification, samples were relaxed for 3 h in a chamber APT Line II (Binder, Germany) to an EMC of 8% at a temperature of 20°C and RH of 42%.

Color values of the wood surface were measured by CM-700D spectrophotometer (Konica Minolta, Japan) (10° standard observer, D65 standard illuminate, color difference format ΔE*ab). To quantify the color, we used the three-dimensional colorimetric system L * a * b *. This color space consists of three mutually perpendicular axes: axis L * determines the lightness from 0 (black) to 100 (white), axis a * determines the ratio of red (positive) to green (negative), and axis b * specifies the ratio of yellow (positive) to blue (negative). To ensure the most accurate results, the color was measured at three specific places for each sample before and after thermal modification. Areas for color measurement were marked on the surfaces of the test specimens before thermal modification to obtain reference data. The marking was done according to the measured area of the spectrophotometer used. After thermal modification, color coordinates were measured at premarked locations. To assess the difference between two colors, we used a total color difference ΔE * (expressing the distance between two points in the L * a * b * system). The ΔE * was evaluated according to and calculated using the formula (equation (1)):

where ΔL *, Δa *, and Δb * are differences in individual axes (difference between the values measured after thermal modification of the sample and the reference sample). Untreated samples at 20°C were chosen as references for each treatment. The measured color values were evaluated in Statistica 14 software by a two-factor analysis, and the analysis factors were the wood species and the temperature.

2.2.4 FTIR analysis of the wood’s main components

Samples were dried before Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy measurements in the vacuum at the temperature of 80°C for 8 h and kept in the desiccator over silica gel. FTIR spectra of the wood surface were recorded on the Nicolet iS10 FT-IR spectrometer, equipped with Smart iTR using an attenuated total reflectance sampling accessory attached to a diamond crystal (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The spectra were measured from 4,000 to 650 cm−1 at a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1, and 32 scans were used. Measurements were performed in four replicates per sample.

2.2.5 Density determination

The wood density was determined before and after thermal modification according to ISO 13061-2 [22]. The dimensions (radial, tangential, and longitudinal) were measured at three places in the middle and 10 mm from the edges of the test samples to calculate the density. The corresponding arithmetic averages for the individual dimensions of the test specimens were calculated from these measurements. The weighing of the test samples followed the measurement of the dimensions to calculate the respective densities.

3 Results and discussion

The impact of different degrees of temperature on chemical components in the examined type of wood samples is presented in Table 1.

Impact of different degrees of temperature on chemical components of wood

| Temperature (°C) | African padauk | Merbau | Mahogany | Iroko | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extractives (%) | 20 | 11.64 (0.07) | 12.30 (0.08) | 7.97 (0.06) | 5.51 (0.11) |

| 160 | 10.64 (0.07) | 9.84 (0.06) | 8.20 (0.06) | 7.16 (0.07) | |

| 180 | 10.45 (0.06) | 7.75 (0.10) | 11.42 (0.08) | 7.31 (0.04) | |

| 210 | 9.48 (0.04) | 11.90 (0.06) | 13.51 (0.08) | 4.33 (0.05) | |

| Lignin (%) | 20 | 33.77 (0.11) | 33.77 (0.23) | 24.84 (0.16) | 29.09 (0.21) |

| 160 | 34.84 (0.04) | 33.24 (0.07) | 25.26 (0.08) | 29.00 (0.14) | |

| 180 | 35.53 (0.05) | 35.78 (0.20) | 27.40 (0.13) | 29.85 (0.10) | |

| 210 | 39.73 (0.08) | 44.64 (0.23) | 31.59 (0.13) | 36.94 (0.22) | |

| Holocellulose (%) | 20 | 66.09 (0.14) | 58.51 (0.32) | 68.42 (0.45) | 72.67 (0.46) |

| 160 | 65.04 (0.47) | 58.58 (2.03) | 67.47 (1.64) | 68.78 (0.46) | |

| 180 | 61.87 (0.33) | 57.11 (0.92) | 61.49 (0.76) | 65.84 (0.30) | |

| 210 | 54.23 (0.12) | 51.70 (0.42) | 54.54 (0.39) | 61.66 (0.51) | |

| Cellulose (%) | 20 | 40.47 (0.09) | 41.44 (0.11) | 45.35 (0.11) | 42.91 (0.37) |

| 160 | 40.81 (0.25) | 42.81 (0.19) | 45.92 (0.15) | 44.08 (2.97) | |

| 180 | 40.40 (0.10) | 47.22 (0.39) | 47.43 (0.35) | 42.45 (0.71) | |

| 210 | 44.07 (0.28) | 49.95 (0.50) | 49.40 (0.48) | 50.89 (0.69) | |

| Hemicelluloses (%) | 20 | 25.62 (0.18) | 17.07 (0.29) | 23.07 (0.38) | 29.77 (0.82) |

| 160 | 24.24 (0.29) | 15.77 (1.51) | 21.55 (1.78) | 24.70 (1.22) | |

| 180 | 21.47 (0.24) | 9.89 (0.11) | 14.06 (0.16) | 23.40 (0.81) | |

| 210 | 10.17 (0.39) | 1.74 (0.25) | 5.13 (0.12) | 10.78 (0.18) |

Note: Values in parentheses are standard deviations.

During thermal treatment, the extractive content changes significantly; however, the trends are different among the species (Table 1). In African padauk, it decreases by approximately 19%, whereas in mahogany, its content increase by approximately 70% compared to the original amount. Changes in merbau and iroko wood species are ambiguous: in merbau, the extractive content decreases and then increases, whereas in the iroko, it first increases and then decreases. The composition of extractives changes at higher temperatures – some disappear, and new ones are formed. They can also migrate to the surface if they are mobile under thermal modification conditions. The drop of extractives content is because of their removal from the wood or degradation during the thermal modification process. According to Esteves et al. [23] and Candelier et al. [24], most of the raw extractives disappeared, and new compounds such as anhydrosugars, mannosan, galactosan, levoglucosan, and two C5 anhydrosugars were generated. Syringaldehyde, sinapaldehyde, and syringic acid appeared to be the products formed in the largest amounts, all of which came from lignin degradation. This hypothesis regarding the formation of new extractives and their role in heat-treated wood durability therefore remains to be confirmed [23,24]. The extractive content of heat-treated wood increased when the treatment was carried out at low temperatures and decreased with treatment carried out at higher temperatures (>220°C) when new compounds are also generated but, under the heat effect, they are then converted into volatile products, leading to a decrease in extractives [24,25]. In our experiments, trends are different for all wood species, which indicates diversity in extractives, and also, different changes in the components of main wood at high temperatures were observed.

The obtained results showed that as the temperature increased, the saccharides content in the wood decreased (Table 1). Hemicelluloses are the least stable wood component by thermal modification [26,27]. Despite having the same trends, certain differences between the individual wood species were observed. As a result of the heat treatment, the relative percentage of hemicelluloses in merbau decreased by around 90%, and in mahogany, there is a drop of about 78%. Hemicelluloses in iroko wood and African padauk are more stable, and the decrease is approximately 64 and 60%, respectively. Similar results were reported for oak and spruce wood modified by the ThermoWood process; however, hemicelluloses in coniferous wood were thermally more stable than hemicelluloses in deciduous wood [5,28]. This phenomenon can be due to different chemical compositions of hemicelluloses in hardwoods vs softwoods; pentosans (mainly in deciduous) degrade more easily on heating than hexosans (mainly in coniferous). However, in our work, only hardwoods were studied; thus, the different losses of hemicelluloses are probably due to their different structures (e.g., molar mass, branch degree, substitution of acetyl groups).

Cellulose is thermally more stable, but it may undergo an esterification and hydrolysis reactions due to the acetic acid generated during the deacetylation of hemicelluloses [24,29]. Cellulose contents increased in evaluated samples with the heat treatment (Table 1). Changes in the cellulose content (the increase or decrease) are highly dependent on the treatment itself and also on the analysis method. Cellulose percentage is likely to increase due to the decrease in hemicelluloses and because of crosslinking reactions [30]. Similar results were reported by other authors with heat-treated Norway spruce, Scots pine, radiata pine, and oak wood [5,6,31].

The lignin content increased in thermally treated wood (Table 1), this being mainly caused by the degradation of the polysaccharides (mostly hemicelluloses). Degradation products of polysaccharides and lignin fragments arising at higher temperatures can contribute to polymerization reactions of lignin, leading to the formation of lignin-like structures, so-called pseudo-lignin [32,33]. Detailed analyzes of meranti, padauk, iroko, teak, and merbau lignins after thermal modification have already been published [34].

According to the overall color change (Table 2), the least significant changes in the thermal modification at 160°C occur in the African padauk. However, even this change falls into the category of high-color changes. For merbau and mahogany wood species, the modification at 160°C showed a higher overall color change; however, these changes can also be included in the same category of changes, i.e., a high-color change. In the case of thermal modification of iroko at the same temperature, the resulting color change can already be classified as a different color. At modification temperatures above 160°C, the color change of all observed wood species was such that in all cases, it could be classified as a different color concerning the reference measurements.

Color space changes due to the temperature of thermal modification according to CIE Lab

| Temperature (°C) | African padauk | Merbau | Mahogany | Iroko | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L * | 20 | 46.60 | 38.53 | 51.19 | 63.12 |

| 160 | 40.28 | 30.35 | 40.16 | 51.48 | |

| 180 | 35.33 | 27.83 | 28.50 | 42.40 | |

| 210 | 30.60 | 13.92 | 19.62 | 32.45 | |

| a * | 20 | 25.90 | 11.46 | 12.39 | 8.22 |

| 160 | 24.01 | 7.71 | 14.61 | 11.19 | |

| 180 | 19.58 | 3.62 | 12.95 | 11.02 | |

| 210 | 9.57 | 1.81 | 5.33 | 7.50 | |

| b * | 20 | 23.37 | 14.47 | 20.53 | 26.05 |

| 160 | 22.40 | 6.76 | 19.72 | 23.62 | |

| 180 | 17.09 | 3.42 | 16.71 | 17.50 | |

| 210 | 8.81 | 1.71 | 7.08 | 9.20 | |

| Δ E | 20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 160 | 6.91 | 11.93 | 11.29 | 12.32 | |

| 180 | 18.58 | 18.50 | 23.02 | 22.38 | |

| 210 | 33.04 | 37.01 | 42.47 | 38.96 |

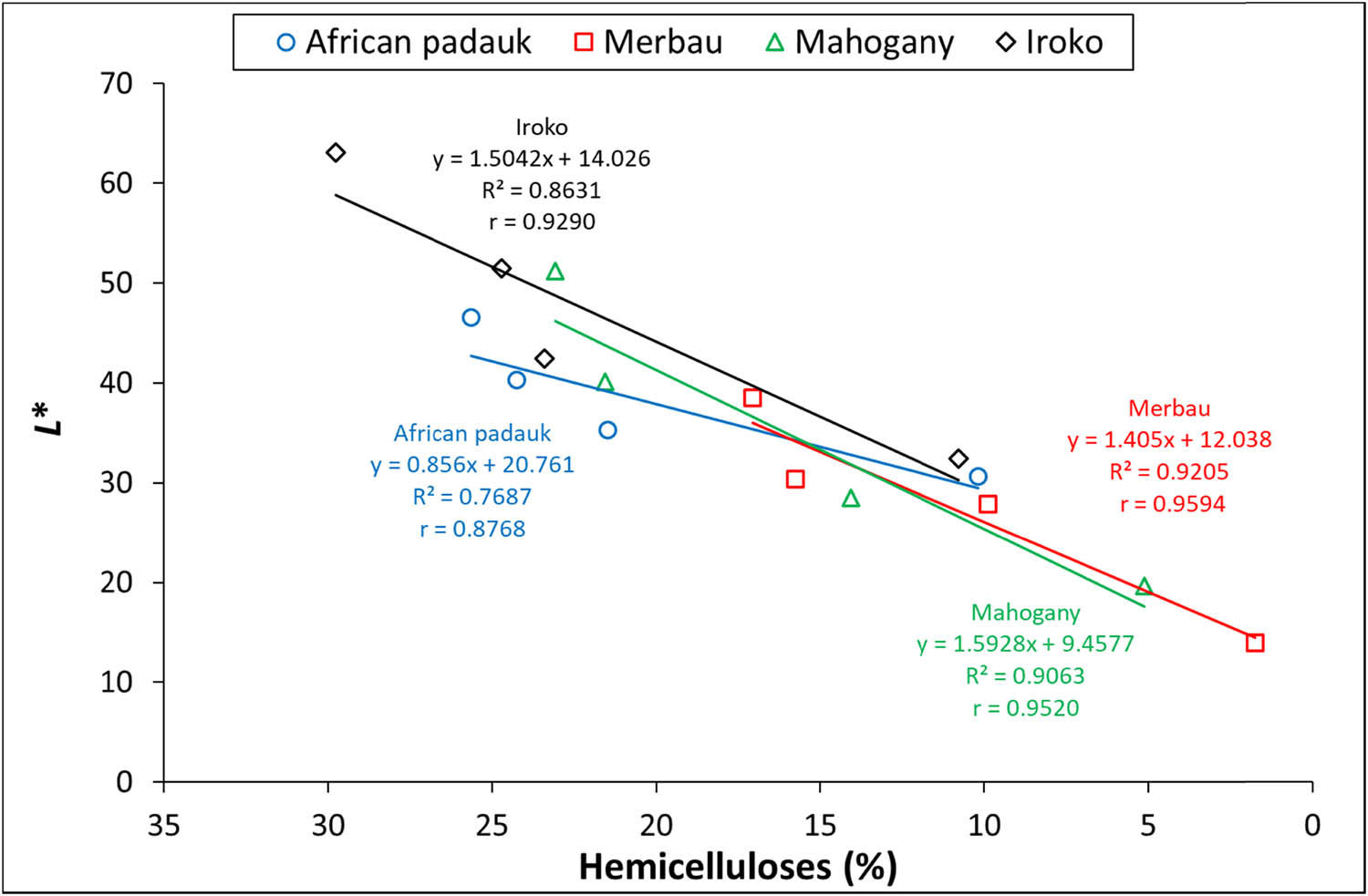

Thermal treatment of the wood resulted in the degradation of lignin and hemicelluloses and a darkening of the wood color, which becomes more significant as the temperature increases [35]. The graph shown in Figure 1 demonstrates the dependence of the ΔL* on the degradation of the hemicelluloses.

Dependence of the ΔL* on the degradation of the hemicelluloses.

A very strong linear relationship with correlation coefficients (r > 0.9) for merbau, mahogany, and iroko wood species was observed; a strong relationship was observed for African padauk (r > 0.8) (Figure 1).

Similarly, a very strong linear relationship between L* and lignin content with correlation coefficients (r > 0.9) for merbau and mahogany wood species was observed; a strong relationship was observed for iroko and African padauk (r > 0.8). It should be noted that wood darkening is not only due to changes in the lignin content but also due to changes in the lignin structure, which is richer than carbohydrates in latent chromophoric groups, e.g., differences taking place between 1,710 and 1,600 cm−1 were associated with quinone formation, due to condensation reactions taking place in lignin [26,36]. The absorbance increase in this infrared region was observed in our work (Figures 2–5).

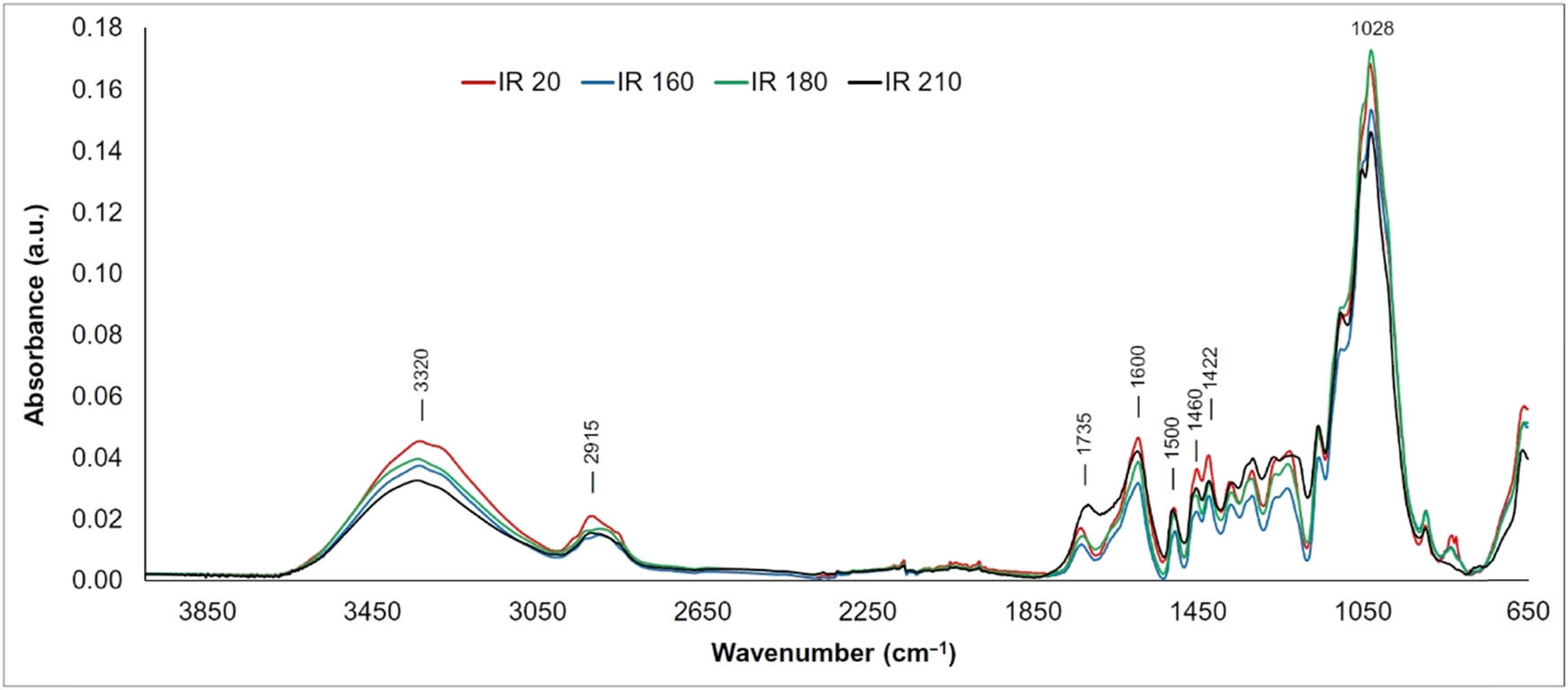

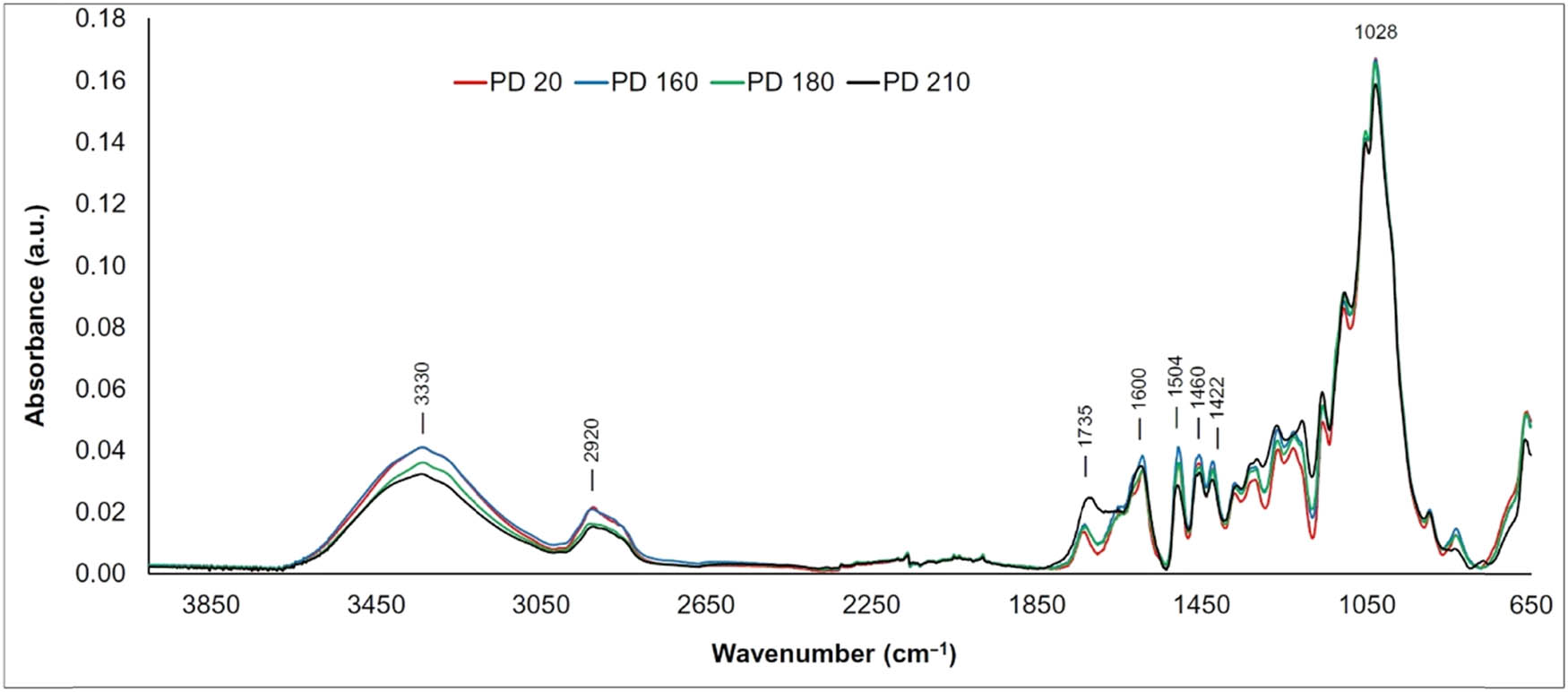

FTIR spectra of the thermally treated iroko wood.

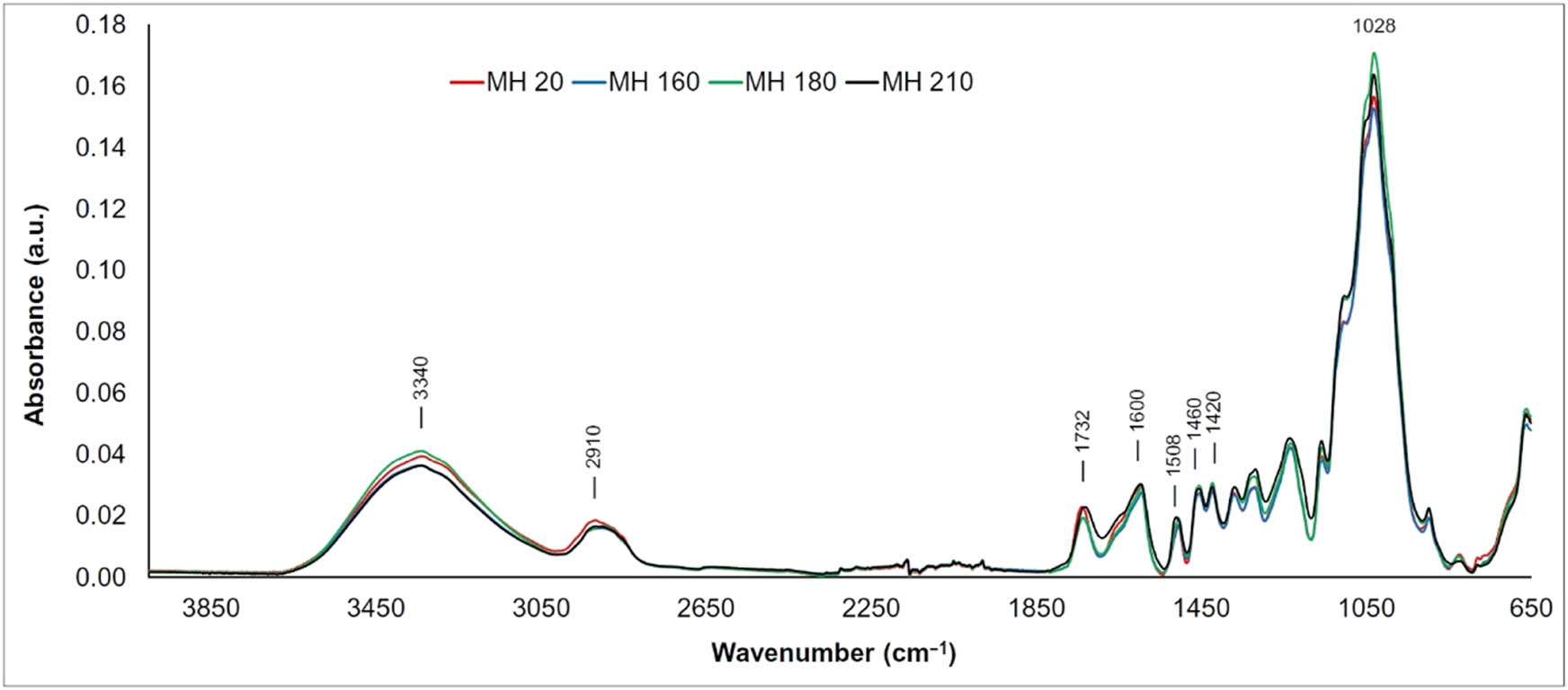

FTIR spectra of the thermally treated mahogany wood.

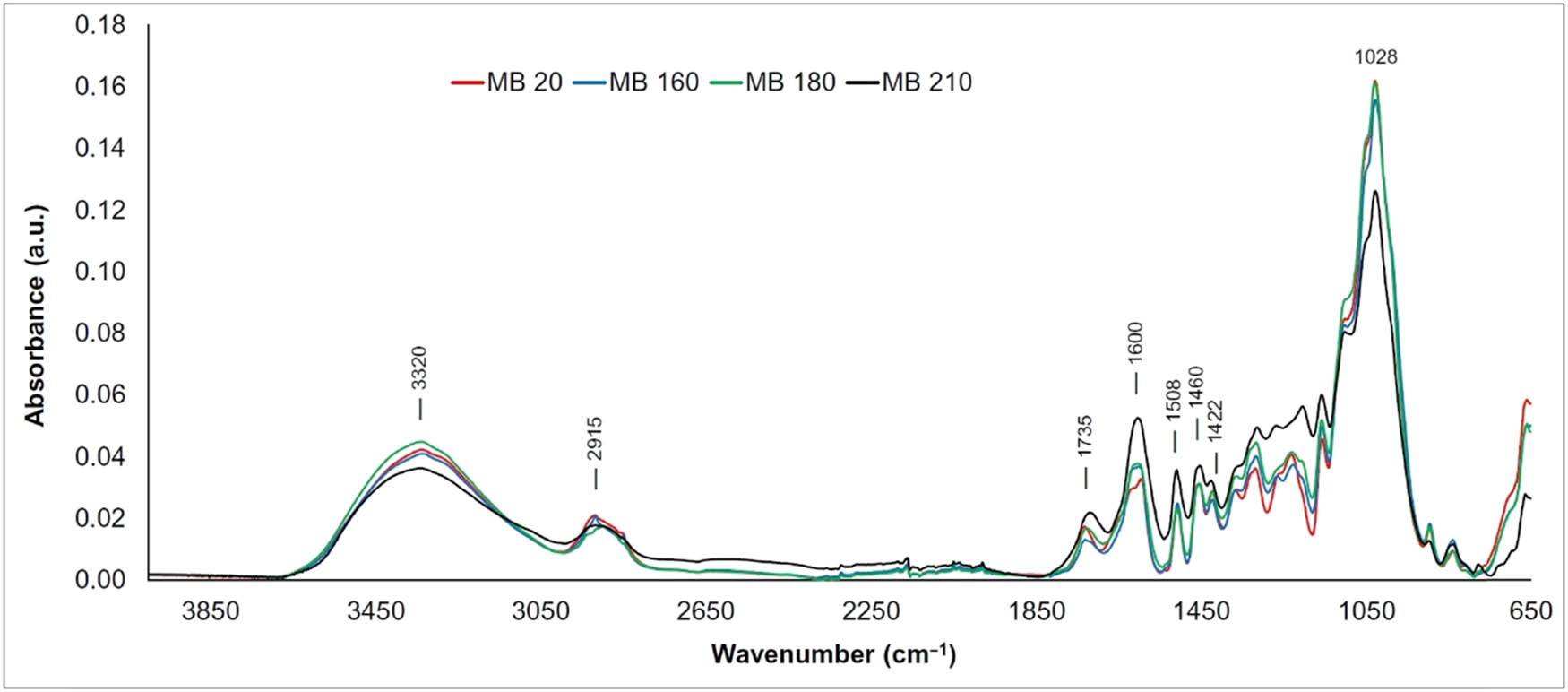

FTIR spectra of the thermally treated merbau wood.

FTIR spectra of the thermally treated African padauk wood.

3.1 Changes in the FTIR spectra

The color of the wood is mainly influenced by chromophoric structures with double bonds, found in lignin and partly also in hemicelluloses [9]. In the FTIR spectra (Figures 2–5), these are mainly bands around 1,735, 1,600, 1,500, 1,460, and 1,422 cm−1 but also near 3,400, 2,900, and 1,030 cm−1 [37]. The wide band with a peak around 3,300 cm−1 (O–H and CH2/CH3 stretching vibrations in the polysaccharides and lignin) gradually decreases with the increasing temperature. According to Hill et al. [38], the thermal modification of wood results in a reduction in the accessible hydroxyl content. The decrease may be due to a decrease in the content of hydroxyl groups in polysaccharides due to their dehydration and in lignin also by gradual condensation of lignin [39]. A similar trend was observed at 2,900 cm−1 (asymmetric CH2, CH3 vibrations), probably due to oxidation and hydrolysis of acetyl groups from hemicelluloses [40].

The absorbance around the 1,735 cm−1 band (C═O vibrations of unconjugated acetyl, carbonyl, and carboxyl groups) shows a slight decrease in temperatures up to 180°C. However, at the highest temperature value (210°C), the absorbance increased. The drop in the band can be caused by the deacetylation of hemicelluloses when thermally treated with wood. This phenomenon was also observed by Windeisen et al. [41]. Other authors also observed an increase in the absorbance of the band around 1,740 cm−1 during thermal modification of wood [40,42]. This trend can be explained by the increased number of acetyl groups and carboxyl groups in lignin, while changes also occur in the C═O group. The increase in intensity may be due to the more pronounced cleavage of beta-alkyl-aryl bonds and the production of carbonyl groups in the thermally degraded lignin, which affects the color changes in the wood [26]. At the highest temperature, a shift of the band maximum of 1,735 cm−1 to the value of 1,720 cm−1 was also observed. This shift to lower wavelengths can be due to the conjugation of the carbonyl group to other double bonds (alkenes, aromatics) while increasing the number of carbonyl or carboxyl groups. These groups are formed in the process of thermal degradation due to oxidation reactions accelerated by high temperature [40]. According to Chen et al. [43], this suggests a reduction in the number of ester structures and carboxyl groups and the formation of α, β-unsaturated ketone and α–C═O in the lignin structure.

Bands at 1,600 and 1,500 cm−1 are assigned C═C aromatic vibrations of the benzene core skeleton in the lignin. In our case, the decrease of both bands (with the exception of merbau) prevailed, accompanied at a temperature of 210°C by a slight shift to higher wavelengths (about 4–8 cm−1). The decrease in absorbance at higher temperatures is caused by a decrease in the number of methoxyl groups as well as the elimination of syringyl units [44]. The growth of the band may be caused by the cleavage of the propyl groups in the lignin, with the concomitant formation of condensed structures [45].

Bands near 1,460 cm−1 (asymmetric C–H deformations of methyl and methylene groups in lignin) and 1,422 cm−1 (aromatic skeletal vibration in lignin with C−H deformation and carbohydrates) show a similar trend in the monitored woody plants. On these belts, a decrease was observed in padauk, iroko, and mahogany, while in merbau, its increase was recorded. The decrease in the band intensity indicates degradation processes in lignin and cleavage of bonds in methoxyl groups, with the formation of conjugated ethylene bonds during heat treatment of lignin [46]. The increase in intensity at 1,460 cm−1 supports the assumption of lignin condensation by −CH2− groups. The band at 1,028 cm−1 (methoxyl groups in lignin and C−O−C stretching of primary alcohol in cellulose and hemicelluloses) [41,47] shows a predominant decrease. This trend may be related to the partial demethoxylation of lignin and its gradual cross-linking [42].

The correlation among the temperature of thermal modification, color parameters, and color space changes by chemical components of the monitored wood samples is evident (Table 3).

Correlation analyzes

| Variable | Temperature (°C) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | −0.9285 | −0.9219 | −0.9733 | −0.9134 |

| a* | −0.7768 | −0.9262 | −0.5797 | 0.0165 |

| b* | −0.7452 | −0.9410 | −0.8156 | −0.7949 |

| ΔE | 0.8729 | 0.9058 | 0.9026 | 0.9176 |

| Extractives (%) | −0.9787 | −0.3129 | 0.8675 | −0.1490 |

| Lignin (%) | 0.8573 | 0.7502 | 0.8456 | 0.7259 |

| Holocellulose (%) | −0.8505 | −0.7647 | −0.8722 | −0.9718 |

| Cellulose (%) | 0.6861 | 0.8954 | 0.8914 | 0.6636 |

| Hemicelluloses (%) | −0.8228 | −0.8700 | −0.8793 | −0.8867 |

| Sample | African padauk | Merbau | Mahogany | Iroko |

Marked correlations are significant at p < 0.05. N = 120 (casewise deletion of missing data).

Density has a close relationship to the mechanical properties of wood and can be used as a parameter to predict some of them, e.g., modulus of rupture and modulus of elasticity [48]. There is a decrease in density during thermal modification (Table 4), indicating the deterioration of mechanical properties. According to Boonstra et al. [49], the drop in wood density after heat treatment is mainly caused by the degradation of hemicelluloses and the evaporation of extractives. Nuopponen et al. [50] reported that low-density samples had somewhat higher lignin contents than high-density samples. Correspondingly, high-density samples contained slightly more polysaccharides than low-density samples.

Wood density before and after thermal modification (g·cm−3)

| Temperature (°C) | African padauk | Merbau | Mahogany | Iroko |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 0.640 (5.5) | 0.822 (4.3) | 0.768 (7.2) | 0.713 (7.8) |

| 160 | 0.623 (6.2) | 0.789 (12.2) | 0.737 (5.1) | 0.673 (17.2) |

| 180 | 0.622 (7.5) | 0.772 (22.0) | 0.738 (6.4) | 0.660 (12.0) |

| 210 | 0.612 (8.5) | 0.749 (20.0) | 0.701 (9.4) | 0.634 (10.0) |

Note: Values in parentheses are coefficients of variation in %.

4 Conclusions

Four types of tropical wood species (African padauk, merbau, mahogany, and iroko) were thermally modified by the ThermoWood process at 160, 180, and 210°C, respectively. Color changes and alterations in extractives and main wood components (lignin, cellulose, and hemicelluloses) were examined by spectrophotometry, infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and wet chemistry methods. From the obtained results can be concluded that observed changes are strongly influenced by the nature of the studied wood species and their respective chemical composition. As the temperature increased, a decrease in lightness (L*) and a simultaneous decrease in chromatic values (a*, b*) were detected, indicating darkening and browning of the wood surface. Results from FTIR spectra confirm the fact that hemicelluloses are the least thermally stable component of wood. Due to heat treatment, the relative content of hemicelluloses decreased the most in merbau and mahogany (90 and 78%, respectively), while the thermal stability of iroko and African padauk was higher (the drop of hemicelluloses about 64 and 60%, respectively). All examined wood species showed a strong correlation between the lightness difference value (ΔL*) and the content of hemicelluloses (r = 0.88–0.96). The findings showed that the breakdown of C═O and C═C bonds in hemicelluloses and lignin plays an important role in the formation of chromophoric structures responsible for the color changes of wood. The obtained information can be applied in the use of heat-treated wood in the exterior and interior. Further studies should be achieved to obtain data on decay durability, dimensional stability, and mechanical properties.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the research agencies listed in the Funding information section for financial support. In addition, they thank the anonymous reviewers for their fruitful suggestions to improve the article.

-

Funding information: The authors are grateful for the support of “Advanced research supporting the forestry and wood-processing sector´s adaptation to global change and the 4th industrial revolution,” No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000803 financed by OP RDE (30%) and from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement N°952314 (20%), by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under contracts APVV-17-0005 (10%), APVV-16-0326 (10%), and APVV-20-0159 (10%) and by the VEGA Agency of Ministry of Education, Science, Research, and Sport of the Slovak Republic no. 1/0117/22 (20%).

-

Author contributions: M.G. and F.K.: design of the study. I.K., A.S., and D.K.: experimentation. M.G., F.K., D.K., I.K., and H.L.: drafting of the manuscript. M.G., I.K., A.S., D.K., H.L., M.K., and F.K.: editorial suggestions and revisions. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Csanády, E., E. Magoss, and L. Tolvaj. Quality of machined wood surfaces, Springer, Berlin, 2015, p. 444.10.1007/978-3-319-22419-0Search in Google Scholar

[2] Yan, J., L. Q. Zhang, X. J. Li, Q. D. Wu, and J. N. Liu. Effect of temperature on color changes and mechanical properties of poplar/bismuth oxide wood alloy during warm-press forming. Journal of Wood Science, Vol. 68, No. 1, 2022, pp. 1–9.10.1186/s10086-022-02032-7Search in Google Scholar

[3] Candelier, K. and J. Dibdiakova. A review on life cycle assessments of thermally modified wood. Holzforschung, Vol. 75, 2021, pp. 199–224.10.1515/hf-2020-0102Search in Google Scholar

[4] Jones, D. and D. Sandberg. A review of wood modification globally–updated findings from COST FP1407. Interdisciplinary Perspectives on the Built Environment, Vol. 1, 2020, id. 1.10.37947/ipbe.2020.vol1.1Search in Google Scholar

[5] Sikora, A., F. Kacik, M. Gaff, V. Vondrova, T. Bubenikova, and I. Kubovsky. Impact of thermal modification on color and chemical changes of spruce and oak wood. Journal of Wood Science, Vol. 64, 2018, pp. 406–416.10.1007/s10086-018-1721-0Search in Google Scholar

[6] Kacikova, D., F. Kacik, I. Cabalova, and J. Durkovic. Effects of thermal treatment on chemical, mechanical and colour traits in Norway spruce wood. Bioresource Technology, Vol. 144, 2013, pp. 669–674.10.1016/j.biortech.2013.06.110Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Kucerova, V., R. Lagana, and T. Hyrosova. Changes in chemical and optical properties of silver fir (Abies alba L.) wood due to thermal treatment. Journal of Wood Science, Vol. 65, 2019, id. 1.10.1186/s10086-019-1800-xSearch in Google Scholar

[8] Johansson, D. and T. Moren. The potential of colour measurement for strength prediction of thermally treated wood. Holz Als Roh-Und Werkstoff, Vol. 64, 2006, pp. 104–110. 10.1007/s00107-005-0082-8Search in Google Scholar

[9] Chen, Y., Y. M. Fan, J. M. Gao, and N. M. Stark. The effect of heat treatment on the chemical and color change of black locust (Robinia Pseudoacacia) wood flour. Bioresources, Vol. 7, 2012, pp. 1157–1170.10.15376/biores.7.1.1157-1170Search in Google Scholar

[10] Kudela, J., I. Kubovsky, and M. Andrejko. Surface properties of beech wood after CO2 laser engraving. Coatings, Vol. 10, 2020, id. 77.10.3390/coatings10010077Search in Google Scholar

[11] Timar, M. C., A. Varodi, M. Hacibektasoglu, and M. Campean. Color and FTIR analysis of chemical changes in beech wood (Fagus sylvatica L.) after light steaming and heat treatment in two different environments. Bioresources, Vol. 11, 2016, pp. 8325–8343.10.15376/biores.11.4.8325-8343Search in Google Scholar

[12] Cuccui, I., F. Negro, R. Zanuttini, M. Espinoza, and O. Allegretti. Thermo-vacuum modification of teak wood from fast-growth plantation. Bioresources, Vol. 12, 2017, pp. 1903–1915. 10.15376/biores.12.1.1903-1915Search in Google Scholar

[13] Gasparik, M., M. Gaff, F. Kacik, and A. Sikora. Color and chemical changes in teak (Tectona grandis L. f.) and Meranti (Shorea spp.) wood after thermal treatment. Bioresources, Vol. 14, 2019, pp. 2667–2683.10.15376/biores.14.2.2667-2683Search in Google Scholar

[14] Hrckova, M., P. Koleda, S. Barcik, and J. Stefkova. Color change of selected wood species affected by thermal treatment and sanding. Bioresources, Vol. 13, 2018, pp. 8956–8975.10.15376/biores.13.4.8956-8975Search in Google Scholar

[15] Nhacila, F., E. Sitoe, E. Uetimane, A. Manhica, A. Egas, and V. Mottonen. Effects of thermal modification on physical and mechanical properties of Mozambican Brachystegia spiciformis and Julbernardia globiflora wood. European Journal of Wood and Wood Products, Vol. 78, 2020, pp. 871–878. 10.1007/s00107-020-01576-zSearch in Google Scholar

[16] Ayata, U., L. Gurleyen, and B. Esteves. Effect of heat treatment on the surface of selected exotic wood species. Drewno, Vol. 60, 2017, pp. 105–116.10.12841/wood.1644-3985.198.08Search in Google Scholar

[17] Mitchel, P. Calculating the equilibrium moisture content for wood based on humidity measurements. BioResources, Vol. 13, 2018, pp. 171–175.10.15376/biores.13.1.171-175Search in Google Scholar

[18] ASTM-D1107-21. Standard Test Method for Ethanol-Toluene Solubility of Wood, American Society for Testing and Materials, Philadelphia. 2021.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Sluiter, A., B. Hames, R. Ruiz, C. Scarlata, J. Sluiter, D. Templeton, et al. Determination of Structural Carbohydrates and Lignin in Biomass; Laboratory analytical procedure (LAP), National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Golden, CO, USA, 2012, NREL/TP-510−42618. http://www.nrel.gov/biomass/analytical_procedures.html.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Seifert, V. K. Űber ein neues Verfahren zur Schnellbestimmung der Rein-Cellulose (About a new method for rapid determination of pure cellulose). Das Papier, Vol. 13, 1956, pp. 301–306.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Wise, L. E., M. Murphy, and A. A. Daddieco. Chlorite holocellulose, its fractionation and bearing on summative wood analysis and on studies on the hemicelluloses. Technical Association Papers, Vol. 29, 1946, pp. 210–218.Search in Google Scholar

[22] ISO/CIE 11664-6:2014. Colorimetry — Part 6: CIEDE2000 Colour-difference formula; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Esteves, B., R. Videira, and H. Pereira. Chemistry and ecotoxicity of heat-treated pine wood extractives. Wood Science and Technology, Vol. 45, 2011, pp. 661–676.10.1007/s00226-010-0356-0Search in Google Scholar

[24] Candelier, K., M. F. Thevenon, R. Collet, P. Gerardin, and S. Dumarcay. Anti-fungal and anti-termite activity of extractives compounds from thermally modified ash woods. Maderas-Ciencia Y Tecnologia, Vol. 22, 2020, pp. 223–240. 10.4067/S0718-221X2020005000209Search in Google Scholar

[25] Wang, Z., X. Yang, B. L. Sun, Y. B. Chai, J. L. Liu, and J. Z. Cao. Effect of vacuum heat treatment on the chemical composition of larch wood. Bioresources, Vol. 11, 2016, pp. 5743–5750. 10.15376/biores.11.3.5743-5750Search in Google Scholar

[26] Torniainen, P., C. M. Popescu, D. Jones, A. Scharf, and D. Sandberg. Correlation of studies between colour, structure and mechanical properties of commercially produced thermowood(R) treated norway spruce and scots pine. Forests, Vol. 12, 2021, id. 1165.10.3390/f12091165Search in Google Scholar

[27] Dauletbek, A., H. Li, Z. Xiong, and R. Lorenzo. A review of mechanical behavior of structural laminated bamboo lumber. Sustainable Structure, Vol. 1, 2021, id. 18.10.54113/j.sust.2021.000004Search in Google Scholar

[28] Zaman, A., R. Alen, and R. Kotilainen. Thermal behavior of scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) and silver birch (Betula pendula) at 200–230°C. Wood and Fiber Science, Vol. 32, 2000, pp. 138–143.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Gao, Y. F., H. T. Wang, J. H. Guo, P. Peng, M. Z. Zhai, and D. She. Hydrothermal degradation of hemicelluloses from triploid poplar in hot compressed water at 180–340°C. Polymer Degradation and Stability, Vol. 126, 2016, pp. 179–187. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2016.02.003Search in Google Scholar

[30] Esteves, B., H. Ferreira, H. Viana, J. Ferreira, I. Domingos, L. Cruz-Lopes, et al. Termite resistance, chemical and mechanical characterization of Paulownia tomentosa wood before and after heat treatment. Forests, Vol. 12, 2021, id. 12.10.3390/f12081114Search in Google Scholar

[31] Boonstra, M. J. and B. Tjeerdsma. Chemical analysis of heat treated softwoods. Holz Als Roh-Und Werkstoff, Vol. 64, 2006, pp. 204–211.10.1007/s00107-005-0078-4Search in Google Scholar

[32] Hu, F., S. Jung, and A. Ragauskas. Pseudo-lignin formation and its impact on enzymatic hydrolysis. Bioresource Technology, Vol. 117, 2012, pp. 7–12.10.1016/j.biortech.2012.04.037Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Shinde, S. D., X. Meng, R. Kumar, and A. J. Ragauskas. Recent advances in understanding the pseudolignin formation in a lignocellulosic biorefinery. Green Chemistry, Vol. 20, 2018, pp. 2192–2205.10.1039/C8GC00353JSearch in Google Scholar

[34] Kacikova, D., I. Kubovsky, N. Ulbrikova, and F. Kacik. The impact of thermal treatment on structural changes of teak and iroko wood lignins. Applied Sciences-Basel, Vol. 10, 2020, id. 10.10.3390/app10145021Search in Google Scholar

[35] Huang, X. A., D. Kocaefe, Y. Kocaefe, Y. Boluk, and A. Pichette. Study of the degradation behavior of heat-treated jack pine (Pinus banksiana) under artificial sunlight irradiation. Polymer Degradation and Stability, Vol. 97, 2012, pp. 1197–1214. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2012.03.022Search in Google Scholar

[36] Gonzalez-Pena, M. M. and M. D. C. Hale. Colour in thermally modified wood of beech, Norway spruce and Scots pine. Part 1: Colour evolution and colour changes. Holzforschung, Vol. 63, 2009, pp. 385–393.10.1515/HF.2009.078Search in Google Scholar

[37] Faix, O. Classification of lignins from different botanical origins by FTIR spectroscopy, Vol. 45, 1991, pp. 21–27. 10.1515/hfsg.1991.45.s1.21Search in Google Scholar

[38] Hill, C., M. Altgen, and L. Rautkari. Thermal modification of wood-a review: chemical changes and hygroscopicity. Journal of Materials Science, Vol. 56, 2021, pp. 6581–6614. 10.1007/s10853-020-05722-zSearch in Google Scholar

[39] Missio, A. L., B. D. Mattos, P. H. G. de Cademartori, A. Pertuzzatti, B. Conte, and D. A. Gatto. Thermochemical and physical properties of two fast-growing eucalypt woods subjected to two-step freeze heat treatments. Thermochimica Acta, Vol. 615, 2015, pp. 15–22. 10.1016/j.tca.2015.07.005Search in Google Scholar

[40] Esteves, B., A. V. Marques, I. Domingos, and H. Pereira. Chemical changes of heat treated pine and eucalypt wood monitored by FTIR. Maderas-Ciencia Y Tecnologia, Vol. 15, 2013, pp. 245–258. 10.4067/S0718-221X2013005000020Search in Google Scholar

[41] Windeisen, E., C. Strobel, and G. Wegener. Chemical changes during the production of thermo-treated beech wood. Wood Science and Technology, Vol. 41, 2007, pp. 523–536. 10.1007/s00226-007-0146-5Search in Google Scholar

[42] Kacik, F., D. Kacikova, and T. Bubenikova. Spruce wood lignin alterations after infrared heating at different wood moistures. Cellulose Chemistry and Technology, Vol. 40, 2006, pp. 643–648.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Chen, Y., J. M. Gao, Y. M. Fan, M. A. Tshabalala, and N. M. Stark. Heat-induced chemical and color changes of extractive-free black locust (Robinia Pseudoacacia) wood. Bioresources, Vol. 7, 2012, pp. 2236–2248.10.15376/biores.7.2.2236-2248Search in Google Scholar

[44] Kubovsky, I., D. Kacikova, and F. Kacik. Structural changes of oak wood main components caused by thermal modification. Polymers, Vol. 12, 2020, id. 485.10.3390/polym12020485Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Colom, X., F. Carrillo, F. Nogues, and P. Garriga. Structural analysis of photodegraded wood by means of FTIR spectroscopy. Polymer Degradation and Stability, Vol. 80, 2003, pp. 543–549.10.1016/S0141-3910(03)00051-XSearch in Google Scholar

[46] Bourgois, J. and R. Guyonnet. Characterization and analysis of torrefied wood. Wood Science and Technology, Vol. 22, 1988, pp. 143–155.10.1007/BF00355850Search in Google Scholar

[47] Bhagia, S., J. Durkovic, R. Lagana, M. Kardosova, F. Kacik, A. Cernescu, et al. Nanoscale FTIR and mechanical mapping of plant cell walls for understanding biomass deconstruction. Acs Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, Vol. 10, 2022, pp. 3016–3026.10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c08163Search in Google Scholar

[48] Missanjo, E. and J. Matsumura. Wood density and mechanical properties of Pinus kesiya Royle ex Gordon in Malawi. Forests, Vol. 7, 2016, id. 135.10.3390/f7070135Search in Google Scholar

[49] Boonstra, M. J., J. Van Acker, B. F. Tjeerdsma, and E. V. Kegel. Strength properties of thermally modified softwoods and its relation to polymeric structural wood constituents. Annals of Forest Science, Vol. 64, 2007, pp. 679–690.10.1051/forest:2007048Search in Google Scholar

[50] Nuopponen, M. H., G. M. Birch, R. J. Sykes, S. J. Lee, and D. Stewart. Estimation of wood density and chemical composition by means of diffuse reflectance mid-infrared fourier transform (DRIFT-MIR) spectroscopy. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, Vol. 54, 2006, pp. 34–40.10.1021/jf051066mSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Progress in preparation and ablation resistance of ultra-high-temperature ceramics modified C/C composites for extreme environment

- Solar lighting systems applied in photocatalysis to treat pollutants – A review

- Technological advances in three-dimensional skin tissue engineering

- Hybrid magnesium matrix composites: A review of reinforcement philosophies, mechanical and tribological characteristics

- Application prospect of calcium peroxide nanoparticles in biomedical field

- Research progress on basalt fiber-based functionalized composites

- Evaluation of the properties and applications of FRP bars and anchors: A review

- A critical review on mechanical, durability, and microstructural properties of industrial by-product-based geopolymer composites

- Multifunctional engineered cementitious composites modified with nanomaterials and their applications: An overview

- Role of bioglass derivatives in tissue regeneration and repair: A review

- Research progress on properties of cement-based composites incorporating graphene oxide

- Properties of ultra-high performance concrete and conventional concrete with coal bottom ash as aggregate replacement and nanoadditives: A review

- A scientometric review of the literature on the incorporation of steel fibers in ultra-high-performance concrete with research mapping knowledge

- Weldability of high nitrogen steels: A review

- Application of waste recycle tire steel fibers as a construction material in concrete

- Wear properties of graphene-reinforced aluminium metal matrix composite: A review

- Experimental investigations of electrodeposited Zn–Ni, Zn–Co, and Ni–Cr–Co–based novel coatings on AA7075 substrate to ameliorate the mechanical, abrasion, morphological, and corrosion properties for automotive applications

- Research evolution on self-healing asphalt: A scientometric review for knowledge mapping

- Recent developments in the mechanical properties of hybrid fiber metal laminates in the automotive industry: A review

- A review of microscopic characterization and related properties of fiber-incorporated cement-based materials

- Comparison and review of classical and machine learning-based constitutive models for polymers used in aeronautical thermoplastic composites

- Gold nanoparticle-based strategies against SARS-CoV-2: A review

- Poly-ferric sulphate as superior coagulant: A review on preparation methods and properties

- A review on ceramic waste-based concrete: A step toward sustainable concrete

- Modification of the structure and properties of oxide layers on aluminium alloys: A review

- A review of magnetically driven swimming microrobots: Material selection, structure design, control method, and applications

- Polyimide–nickel nanocomposites fabrication, properties, and applications: A review

- Design and analysis of timber-concrete-based civil structures and its applications: A brief review

- Effect of fiber treatment on physical and mechanical properties of natural fiber-reinforced composites: A review

- Blending and functionalisation modification of 3D printed polylactic acid for fused deposition modeling

- A critical review on functionally graded ceramic materials for cutting tools: Current trends and future prospects

- Heme iron as potential iron fortifier for food application – characterization by material techniques

- An overview of the research trends on fiber-reinforced shotcrete for construction applications

- High-entropy alloys: A review of their performance as promising materials for hydrogen and molten salt storage

- Effect of the axial compression ratio on the seismic behavior of resilient concrete walls with concealed column stirrups

- Research Articles

- Effect of fiber orientation and elevated temperature on the mechanical properties of unidirectional continuous kenaf reinforced PLA composites

- Optimizing the ECAP processing parameters of pure Cu through experimental, finite element, and response surface approaches

- Study on the solidification property and mechanism of soft soil based on the industrial waste residue

- Preparation and photocatalytic degradation of Sulfamethoxazole by g-C3N4 nano composite samples

- Impact of thermal modification on color and chemical changes of African padauk, merbau, mahogany, and iroko wood species

- The evaluation of the mechanical properties of glass, kenaf, and honeycomb fiber-reinforced composite

- Evaluation of a novel steel box-soft body combination for bridge protection against ship collision

- Study on the uniaxial compression constitutive relationship of modified yellow mud from minority dwelling in western Sichuan, China

- Ultrasonic longitudinal torsion-assisted biotic bone drilling: An experimental study

- Green synthesis, characterizations, and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles from Themeda quadrivalvis, in conjugation with macrolide antibiotics against respiratory pathogens

- Performance analysis of WEDM during the machining of Inconel 690 miniature gear using RSM and ANN modeling approaches

- Biosynthesis of Ag/bentonite, ZnO/bentonite, and Ag/ZnO/bentonite nanocomposites by aqueous leaf extract of Hagenia abyssinica for antibacterial activities

- Eco-friendly MoS2/waste coconut oil nanofluid for machining of magnesium implants

- Silica and kaolin reinforced aluminum matrix composite for heat storage

- Optimal design of glazed hollow bead thermal insulation mortar containing fly ash and slag based on response surface methodology

- Hemp seed oil nanoemulsion with Sapindus saponins as a potential carrier for iron supplement and vitamin D

- A numerical study on thin film flow and heat transfer enhancement for copper nanoparticles dispersed in ethylene glycol

- Research on complex multimodal vibration characteristics of offshore platform

- Applicability of fractal models for characterising pore structure of hybrid basalt–polypropylene fibre-reinforced concrete

- Influence of sodium silicate to precursor ratio on mechanical properties and durability of the metakaolin/fly ash alkali-activated sustainable mortar using manufactured sand

- An experimental study of bending resistance of multi-size PFRC beams

- Characterization, biocompatibility, and optimization of electrospun SF/PCL composite nanofiber films

- Morphological classification method and data-driven estimation of the joint roughness coefficient by consideration of two-order asperity

- Prediction and simulation of mechanical properties of borophene-reinforced epoxy nanocomposites using molecular dynamics and FEA

- Nanoemulsions of essential oils stabilized with saponins exhibiting antibacterial and antioxidative properties

- Fabrication and performance analysis of sustainable municipal solid waste incineration fly ash alkali-activated acoustic barriers

- Electrostatic-spinning construction of HCNTs@Ti3C2T x MXenes hybrid aerogel microspheres for tunable microwave absorption

- Investigation of the mechanical properties, surface quality, and energy efficiency of a fused filament fabrication for PA6

- Experimental study on mechanical properties of coal gangue base geopolymer recycled aggregate concrete reinforced by steel fiber and nano-Al2O3

- Hybrid bio-fiber/bio-ceramic composite materials: Mechanical performance, thermal stability, and morphological analysis

- Experimental study on recycled steel fiber-reinforced concrete under repeated impact

- Effect of rare earth Nd on the microstructural transformation and mechanical properties of 7xxx series aluminum alloys

- Color match evaluation using instrumental method for three single-shade resin composites before and after in-office bleaching

- Exploring temperature-resilient recycled aggregate concrete with waste rubber: An experimental and multi-objective optimization analysis

- Study on aging mechanism of SBS/SBR compound-modified asphalt based on molecular dynamics

- Evolution of the pore structure of pumice aggregate concrete and the effect on compressive strength

- Effect of alkaline treatment time of fibers and microcrystalline cellulose addition on mechanical properties of unsaturated polyester composites reinforced by cantala fibers

- Optimization of eggshell particles to produce eco-friendly green fillers with bamboo reinforcement in organic friction materials

- An effective approach to improve microstructure and tribological properties of cold sprayed Al alloys

- Luminescence and temperature-sensing properties of Li+, Na+, or K+, Tm3+, and Yb3+ co-doped Bi2WO6 phosphors

- Effect of molybdenum tailings aggregate on mechanical properties of engineered cementitious composites and stirrup-confined ECC stub columns

- Experimental study on the seismic performance of short shear walls comprising cold-formed steel and high-strength reinforced concrete with concealed bracing

- Failure criteria and microstructure evolution mechanism of the alkali–silica reaction of concrete

- Mechanical, fracture-deformation, and tribology behavior of fillers-reinforced sisal fiber composites for lightweight automotive applications

- UV aging behavior evolution characterization of HALS-modified asphalt based on micro-morphological features

- Preparation of VO2/graphene/SiC film by water vapor oxidation

- A semi-empirical model for predicting carbonation depth of RAC under two-dimensional conditions

- Comparison of the physical properties of different polyimide nanocomposite films containing organoclays varying in alkyl chain lengths

- Effects of freeze–thaw cycles on micro and meso-structural characteristics and mechanical properties of porous asphalt mixtures

- Flexural performance of a new type of slightly curved arc HRB400 steel bars reinforced one-way concrete slabs

- Alkali-activated binder based on red mud with class F fly ash and ground granulated blast-furnace slag under ambient temperature

- Facile synthesis of g-C3N4 nanosheets for effective degradation of organic pollutants via ball milling

- DEM study on the loading rate effect of marble under different confining pressures

- Conductive and self-cleaning composite membranes from corn husk nanofiber embedded with inorganic fillers (TiO2, CaO, and eggshell) by sol–gel and casting processes for smart membrane applications

- Laser re-melting of modified multimodal Cr3C2–NiCr coatings by HVOF: Effect on the microstructure and anticorrosion properties

- Damage constitutive model of jointed rock mass considering structural features and load effect

- Thermosetting polymer composites: Manufacturing and properties study

- CSG compressive strength prediction based on LSTM and interpretable machine learning

- Axial compression behavior and stress–strain relationship of slurry-wrapping treatment recycled aggregate concrete-filled steel tube short columns

- Space-time evolution characteristics of loaded gas-bearing coal fractures based on industrial μCT

- Dual-biprism-based single-camera high-speed 3D-digital image correlation for deformation measurement on sandwich structures under low velocity impact

- Effects of cold deformation modes on microstructure uniformity and mechanical properties of large 2219 Al–Cu alloy rings

- Basalt fiber as natural reinforcement to improve the performance of ecological grouting slurry for the conservation of earthen sites

- Interaction of micro-fluid structure in a pressure-driven duct flow with a nearby placed current-carrying wire: A numerical investigation

- A simulation modeling methodology considering random multiple shots for shot peening process

- Optimization and characterization of composite modified asphalt with pyrolytic carbon black and chicken feather fiber

- Synthesis, characterization, and application of the novel nanomagnet adsorbent for the removal of Cr(vi) ions

- Multi-perspective structural integrity-based computational investigations on airframe of Gyrodyne-configured multi-rotor UAV through coupled CFD and FEA approaches for various lightweight sandwich composites and alloys

- Influence of PVA fibers on the durability of cementitious composites under the wet–heat–salt coupling environment

- Compressive behavior of BFRP-confined ceramsite concrete: An experimental study and stress–strain model

- Interval models for uncertainty analysis and degradation prediction of the mechanical properties of rubber

- Preparation of PVDF-HFP/CB/Ni nanocomposite films for piezoelectric energy harvesting

- Frost resistance and life prediction of recycled brick aggregate concrete with waste polypropylene fiber

- Synthetic leathers as a possible source of chemicals and odorous substances in indoor environment

- Mechanical properties of seawater volcanic scoria aggregate concrete-filled circular GFRP and stainless steel tubes under axial compression

- Effect of curved anchor impellers on power consumption and hydrodynamic parameters of yield stress fluids (Bingham–Papanastasiou model) in stirred tanks

- All-dielectric tunable zero-refractive index metamaterials based on phase change materials

- Influence of ultrasonication time on the various properties of alkaline-treated mango seed waste filler reinforced PVA biocomposite

- Research on key casting process of high-grade CNC machine tool bed nodular cast iron

- Latest research progress of SiCp/Al composite for electronic packaging

- Special Issue on 3D and 4D Printing of Advanced Functional Materials - Part I

- Molecular dynamics simulation on electrohydrodynamic atomization: Stable dripping mode by pre-load voltage

- Research progress of metal-based additive manufacturing in medical implants

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Progress in preparation and ablation resistance of ultra-high-temperature ceramics modified C/C composites for extreme environment

- Solar lighting systems applied in photocatalysis to treat pollutants – A review

- Technological advances in three-dimensional skin tissue engineering

- Hybrid magnesium matrix composites: A review of reinforcement philosophies, mechanical and tribological characteristics

- Application prospect of calcium peroxide nanoparticles in biomedical field

- Research progress on basalt fiber-based functionalized composites

- Evaluation of the properties and applications of FRP bars and anchors: A review

- A critical review on mechanical, durability, and microstructural properties of industrial by-product-based geopolymer composites

- Multifunctional engineered cementitious composites modified with nanomaterials and their applications: An overview

- Role of bioglass derivatives in tissue regeneration and repair: A review

- Research progress on properties of cement-based composites incorporating graphene oxide

- Properties of ultra-high performance concrete and conventional concrete with coal bottom ash as aggregate replacement and nanoadditives: A review

- A scientometric review of the literature on the incorporation of steel fibers in ultra-high-performance concrete with research mapping knowledge

- Weldability of high nitrogen steels: A review

- Application of waste recycle tire steel fibers as a construction material in concrete

- Wear properties of graphene-reinforced aluminium metal matrix composite: A review

- Experimental investigations of electrodeposited Zn–Ni, Zn–Co, and Ni–Cr–Co–based novel coatings on AA7075 substrate to ameliorate the mechanical, abrasion, morphological, and corrosion properties for automotive applications

- Research evolution on self-healing asphalt: A scientometric review for knowledge mapping

- Recent developments in the mechanical properties of hybrid fiber metal laminates in the automotive industry: A review

- A review of microscopic characterization and related properties of fiber-incorporated cement-based materials

- Comparison and review of classical and machine learning-based constitutive models for polymers used in aeronautical thermoplastic composites

- Gold nanoparticle-based strategies against SARS-CoV-2: A review

- Poly-ferric sulphate as superior coagulant: A review on preparation methods and properties

- A review on ceramic waste-based concrete: A step toward sustainable concrete

- Modification of the structure and properties of oxide layers on aluminium alloys: A review

- A review of magnetically driven swimming microrobots: Material selection, structure design, control method, and applications

- Polyimide–nickel nanocomposites fabrication, properties, and applications: A review

- Design and analysis of timber-concrete-based civil structures and its applications: A brief review

- Effect of fiber treatment on physical and mechanical properties of natural fiber-reinforced composites: A review

- Blending and functionalisation modification of 3D printed polylactic acid for fused deposition modeling

- A critical review on functionally graded ceramic materials for cutting tools: Current trends and future prospects

- Heme iron as potential iron fortifier for food application – characterization by material techniques

- An overview of the research trends on fiber-reinforced shotcrete for construction applications

- High-entropy alloys: A review of their performance as promising materials for hydrogen and molten salt storage

- Effect of the axial compression ratio on the seismic behavior of resilient concrete walls with concealed column stirrups

- Research Articles

- Effect of fiber orientation and elevated temperature on the mechanical properties of unidirectional continuous kenaf reinforced PLA composites

- Optimizing the ECAP processing parameters of pure Cu through experimental, finite element, and response surface approaches

- Study on the solidification property and mechanism of soft soil based on the industrial waste residue

- Preparation and photocatalytic degradation of Sulfamethoxazole by g-C3N4 nano composite samples

- Impact of thermal modification on color and chemical changes of African padauk, merbau, mahogany, and iroko wood species

- The evaluation of the mechanical properties of glass, kenaf, and honeycomb fiber-reinforced composite

- Evaluation of a novel steel box-soft body combination for bridge protection against ship collision

- Study on the uniaxial compression constitutive relationship of modified yellow mud from minority dwelling in western Sichuan, China

- Ultrasonic longitudinal torsion-assisted biotic bone drilling: An experimental study

- Green synthesis, characterizations, and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles from Themeda quadrivalvis, in conjugation with macrolide antibiotics against respiratory pathogens

- Performance analysis of WEDM during the machining of Inconel 690 miniature gear using RSM and ANN modeling approaches

- Biosynthesis of Ag/bentonite, ZnO/bentonite, and Ag/ZnO/bentonite nanocomposites by aqueous leaf extract of Hagenia abyssinica for antibacterial activities

- Eco-friendly MoS2/waste coconut oil nanofluid for machining of magnesium implants

- Silica and kaolin reinforced aluminum matrix composite for heat storage

- Optimal design of glazed hollow bead thermal insulation mortar containing fly ash and slag based on response surface methodology

- Hemp seed oil nanoemulsion with Sapindus saponins as a potential carrier for iron supplement and vitamin D

- A numerical study on thin film flow and heat transfer enhancement for copper nanoparticles dispersed in ethylene glycol

- Research on complex multimodal vibration characteristics of offshore platform

- Applicability of fractal models for characterising pore structure of hybrid basalt–polypropylene fibre-reinforced concrete

- Influence of sodium silicate to precursor ratio on mechanical properties and durability of the metakaolin/fly ash alkali-activated sustainable mortar using manufactured sand

- An experimental study of bending resistance of multi-size PFRC beams

- Characterization, biocompatibility, and optimization of electrospun SF/PCL composite nanofiber films

- Morphological classification method and data-driven estimation of the joint roughness coefficient by consideration of two-order asperity

- Prediction and simulation of mechanical properties of borophene-reinforced epoxy nanocomposites using molecular dynamics and FEA

- Nanoemulsions of essential oils stabilized with saponins exhibiting antibacterial and antioxidative properties

- Fabrication and performance analysis of sustainable municipal solid waste incineration fly ash alkali-activated acoustic barriers

- Electrostatic-spinning construction of HCNTs@Ti3C2T x MXenes hybrid aerogel microspheres for tunable microwave absorption

- Investigation of the mechanical properties, surface quality, and energy efficiency of a fused filament fabrication for PA6

- Experimental study on mechanical properties of coal gangue base geopolymer recycled aggregate concrete reinforced by steel fiber and nano-Al2O3

- Hybrid bio-fiber/bio-ceramic composite materials: Mechanical performance, thermal stability, and morphological analysis

- Experimental study on recycled steel fiber-reinforced concrete under repeated impact

- Effect of rare earth Nd on the microstructural transformation and mechanical properties of 7xxx series aluminum alloys

- Color match evaluation using instrumental method for three single-shade resin composites before and after in-office bleaching

- Exploring temperature-resilient recycled aggregate concrete with waste rubber: An experimental and multi-objective optimization analysis

- Study on aging mechanism of SBS/SBR compound-modified asphalt based on molecular dynamics

- Evolution of the pore structure of pumice aggregate concrete and the effect on compressive strength

- Effect of alkaline treatment time of fibers and microcrystalline cellulose addition on mechanical properties of unsaturated polyester composites reinforced by cantala fibers

- Optimization of eggshell particles to produce eco-friendly green fillers with bamboo reinforcement in organic friction materials

- An effective approach to improve microstructure and tribological properties of cold sprayed Al alloys

- Luminescence and temperature-sensing properties of Li+, Na+, or K+, Tm3+, and Yb3+ co-doped Bi2WO6 phosphors

- Effect of molybdenum tailings aggregate on mechanical properties of engineered cementitious composites and stirrup-confined ECC stub columns

- Experimental study on the seismic performance of short shear walls comprising cold-formed steel and high-strength reinforced concrete with concealed bracing

- Failure criteria and microstructure evolution mechanism of the alkali–silica reaction of concrete

- Mechanical, fracture-deformation, and tribology behavior of fillers-reinforced sisal fiber composites for lightweight automotive applications

- UV aging behavior evolution characterization of HALS-modified asphalt based on micro-morphological features

- Preparation of VO2/graphene/SiC film by water vapor oxidation

- A semi-empirical model for predicting carbonation depth of RAC under two-dimensional conditions

- Comparison of the physical properties of different polyimide nanocomposite films containing organoclays varying in alkyl chain lengths

- Effects of freeze–thaw cycles on micro and meso-structural characteristics and mechanical properties of porous asphalt mixtures

- Flexural performance of a new type of slightly curved arc HRB400 steel bars reinforced one-way concrete slabs

- Alkali-activated binder based on red mud with class F fly ash and ground granulated blast-furnace slag under ambient temperature

- Facile synthesis of g-C3N4 nanosheets for effective degradation of organic pollutants via ball milling

- DEM study on the loading rate effect of marble under different confining pressures

- Conductive and self-cleaning composite membranes from corn husk nanofiber embedded with inorganic fillers (TiO2, CaO, and eggshell) by sol–gel and casting processes for smart membrane applications

- Laser re-melting of modified multimodal Cr3C2–NiCr coatings by HVOF: Effect on the microstructure and anticorrosion properties

- Damage constitutive model of jointed rock mass considering structural features and load effect

- Thermosetting polymer composites: Manufacturing and properties study

- CSG compressive strength prediction based on LSTM and interpretable machine learning

- Axial compression behavior and stress–strain relationship of slurry-wrapping treatment recycled aggregate concrete-filled steel tube short columns

- Space-time evolution characteristics of loaded gas-bearing coal fractures based on industrial μCT

- Dual-biprism-based single-camera high-speed 3D-digital image correlation for deformation measurement on sandwich structures under low velocity impact

- Effects of cold deformation modes on microstructure uniformity and mechanical properties of large 2219 Al–Cu alloy rings

- Basalt fiber as natural reinforcement to improve the performance of ecological grouting slurry for the conservation of earthen sites

- Interaction of micro-fluid structure in a pressure-driven duct flow with a nearby placed current-carrying wire: A numerical investigation

- A simulation modeling methodology considering random multiple shots for shot peening process

- Optimization and characterization of composite modified asphalt with pyrolytic carbon black and chicken feather fiber

- Synthesis, characterization, and application of the novel nanomagnet adsorbent for the removal of Cr(vi) ions

- Multi-perspective structural integrity-based computational investigations on airframe of Gyrodyne-configured multi-rotor UAV through coupled CFD and FEA approaches for various lightweight sandwich composites and alloys

- Influence of PVA fibers on the durability of cementitious composites under the wet–heat–salt coupling environment

- Compressive behavior of BFRP-confined ceramsite concrete: An experimental study and stress–strain model

- Interval models for uncertainty analysis and degradation prediction of the mechanical properties of rubber

- Preparation of PVDF-HFP/CB/Ni nanocomposite films for piezoelectric energy harvesting

- Frost resistance and life prediction of recycled brick aggregate concrete with waste polypropylene fiber

- Synthetic leathers as a possible source of chemicals and odorous substances in indoor environment

- Mechanical properties of seawater volcanic scoria aggregate concrete-filled circular GFRP and stainless steel tubes under axial compression

- Effect of curved anchor impellers on power consumption and hydrodynamic parameters of yield stress fluids (Bingham–Papanastasiou model) in stirred tanks

- All-dielectric tunable zero-refractive index metamaterials based on phase change materials

- Influence of ultrasonication time on the various properties of alkaline-treated mango seed waste filler reinforced PVA biocomposite

- Research on key casting process of high-grade CNC machine tool bed nodular cast iron

- Latest research progress of SiCp/Al composite for electronic packaging

- Special Issue on 3D and 4D Printing of Advanced Functional Materials - Part I

- Molecular dynamics simulation on electrohydrodynamic atomization: Stable dripping mode by pre-load voltage

- Research progress of metal-based additive manufacturing in medical implants