Poly-ferric sulphate as superior coagulant: A review on preparation methods and properties

-

Nurul Aqilah Mohamad

, Nur Hanis Hayati Hairom

, Mohd Mustafa al Bakri Abdullah

Abstract

Iron-based coagulants are widely used in wastewater treatment due to their high positively charged ion that effectively destabilise colloidal suspension, and thus contribute to the formation of insoluble flocs. Ferric chloride, ferrous sulphate, and poly-ferric sulphate (PFS) are examples of iron-based coagulants that are highly available, and are beneficial in producing denser flocs, thereby improving settling characteristics. This work aims to review the preparation methods of PFS and critically discuss the influence of these methods on the PFS properties and performance as a chemical coagulant for water and wastewater treatment. In polymeric form, PFS is one of the pre-hydrolysing metallic salts with the chemical formula [Fe2(OH) n (SO4)3−n/2] m (where, n < 2, m > 10) and has a dark brownish red colour as well as is more viscous and less corrosive. PFS has an amorphous structure with small traces of crystallinity, containing both hydroxyl and sulphate functional groups. It has been applied in many industries including water or wastewater treatment which is also discussed in this study. It has the ability to remove pollutants contained in water or wastewater, such as turbidity, colour, chemical and biological oxygen demand, phosphorus, and others. This study also provides a review on the combination of PFS with other chemical coagulants or flocculants in the coagulation/flocculation process, and also flocs formed after a more stable treatment process.

With the growth of the urbanisation and industrial sectors, water demand has increased as it is essential in many unit operations, thus resulting in a large amount of water discharge. Industrial wastewater may be of low quality due to its high pollutant content, which poses a major hazard to surface and underground water if not treated properly [1]. It is necessary to remove contaminants from wastewater before it is discharged into a watercourse or re-used or recycled for other purposes [2]. Particles or pollutants contained in wastewater come in a wide range of sizes, shapes, and densities, which affect their reactions in water [3]. There are various treatment methods used for water or wastewater including membrane technology [4], adsorption [5,6,7], filtration [8], ponding system, and others.

Another conventional wastewater treatment method is coagulation/flocculation, where particular chemicals are added to water [9,10,11]. It results in a physical change in the state of dissolved and suspended particles, allowing them to be removed more easily through sedimentation and filtration [12,13]. This method plays a crucial role in adsorbing or connecting colloids, lowering the surface charge of colloids [1] to destabilise colloidal suspensions, and remove suspended particles [12,14,15]. Coagulation/flocculation is a key principle in colloid chemistry that allows fine particles suspended in water to clump together and form large flocs [16], which can then be separated from water [17]. As a result, it can reduce numerous pollutants effectively as well as reduce the concentration of chemical and biological oxygen demand (BOD), turbidity, colour, suspended solids (SS), heavy metal, oil and grease, and other organic matters.

Abujazar et al. asserted that it is crucial to determine the effectiveness of the coagulant function in specific conditions as coagulation is a complicated process considering numerous aspects [16]. There are three major types of coagulants/flocculants, namely, inorganic, organic, and composite coagulants [1,18,19]. They are also categorised as hydrolysing metallic salts, pre-hydrolysing metallic salts, and synthetic cationic polymers [13], as illustrated in Figure 1, which are more efficient than water-soluble hydrolysing metallic salts [20]. They tend to reduce colour concentration at low temperatures and produce less sludge [13].

Chemical coagulant classification.

Conventional metal coagulants, both polymeric and monomeric forms of aluminium (Al) and iron (Fe) salts, are commonly utilised in the treatment of water or wastewater [11,21,22]. However, aluminium salts are toxic to humans and living organisms [23]. As a result, the use of iron salts has expanded as they are more efficient in removing dissolved organic carbon (DOC) than aluminium-based salts [24]. In addition, iron-based coagulants (Figure 2) are another coagulant of choice, and have been widely used in water and wastewater treatment. Copperas or ferrous sulphate (Figure 2a) is one of the inorganic coagulants in the form of iron-based salts that is commercially available, less expensive, and promotes high coagulation efficiency. This type of coagulant has widely been used in rubber processing effluent [25], palm oil mill effluent [11], groundwater [26], and other water or wastewater treatments. It can also control odour and thicken sludge, and can act as a dewatering agent for wastewater treatment [27]. Copperas is a by-product of the titanium dioxide manufacturing industry, which is formed during crystallisation via the sulphate process. However, a significant disadvantage of conventional coagulants is their inability to control the nature, temperature, and pH of the water to be treated, and occasionally it may worsen depending on the change in water characteristics.

Chemical structures of (a) ferrous sulphate and (b) PFS.

Therefore, copperas will be partially neutralised with sulphuric acid under high concentration to form pre-hydrolysing coagulants with high molecular weight. Among them are poly-ferric sulphate (PFS; Figure 2b) [28,29] and poly-ferric chloride [30] which are frequently used to treat heavy metals in contaminated water or wastewater. They have received substantial interest due to their several benefits over monomeric versions as iron-based salts can operate in a wider pH range, are less sensitive to temperature [31,32,33], have lower residual ferric concentrations [31,32], and have low corrosiveness and excellent sewage treatment properties [34]. Gregory and Rossi evaluated the performance of several pre-hydrolysing coagulants for wastewater treatment, and observed that this type of coagulant provided faster flocculation and stronger flocs than hydrolysing salts at equal doses [35]. This is probably because these coagulants are pre-neutralised, have less effect on pH of water, and require less pH correction. In general, ferric ion is more favourable and effective in removing colour, turbidity, and total carbon, and it has no toxicity concerns [36,37,38].

This work reviews and discusses the preparation methods of PFS and their influence on PFS properties. This work also reviews the combination of PFS with other chemical coagulants or flocculants in the coagulation/flocculation process, and also the flocs formed after the more stable treatment process. Overall, a new knowledge base will enhance the quality of the prepared PFS and the treated effluent in various industries.

1 Preparation methods and properties of PFS

1.1 Preparation methods of PFS

There are several methods available for preparing PFS. Traditionally, PFS is prepared through a simple process of oxidation, hydrolysis, and polymerisation of ferrous sulphate in a highly acidic solution. Graham and Jiang patented the preparation and use of PFS (US Patent, Patent no.: 5785862) [39]. The patent described the PFS preparation process involving a catalytic oxidation method of a solution comprising H2SO4 and FeSO4 under highly acidic conditions (pH 3), including hydrolysis, oxidation, and polymerisation as reported by Cheng, Jiang et al., and Fan et al. [31,40,41]. Since then, numerous studies have been conducted on the synthesis and processing of PFS.

Generally, the reaction in the synthesis of PFS through the oxidation process is achieved by these three steps (as illustrated in Figure 3) [15,36,38,42,43]:

In the formation of basic salt Fe2(OH) n (SO4)3−n/2, it requires 3/2 molar feed ratio of Fe2+ to SO4 2−, where OH− substitutes SO4 2− [43] as shown in reaction (2) below:

And finally, the polymerisation reaction occurs in generating PFS as indicated in reaction (3) below:

where, m is the function of n(n < 2) [41]. Figure 3 illustrates the synthesis process of PFS [30,44].

Hydrolysis and polymerisation processes of Fe(iii) species.

In previous studies, the synthesis of PFS could be achieved through the addition of ferric sulphate solution to sodium hydroxide or sodium bicarbonate solution [43], and oxidation of ferrous sulphate to ferric sulphate in highly acidic conditions [45]. Nitric acid, hydrogen peroxide, sodium/potassium chlorate, oxygen, and oxygen-enriched air are the most frequently utilised oxidising agents [12,41,43,46]. It may be essential to find other oxidising agents for the synthesis of PFS that may induce high cationic charge in the coagulant, thus improving the charge neutralising capacity.

Several parameters of PFS synthesis have been reported in previous studies, namely, the temperature and duration of each preparation method stage, type of chemical used, and concentration of ferrous sulphate, as tabulated in Table 1. As mentioned above, seeking alternative oxidising agents may be necessary to synthesise PFS that may induce high cationic charge in the coagulant.

Comparison of PFS and its characteristics according to the relevant literature

| Ref. | Conditions | Properties | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fetotal | Fe(iii) | Fe(ii) | pH | [OH−] /[Fe+3] | Basicity | Density | Viscosity | Conductivity | z-potential | ||

| Catalytic oxidation of ferrous sulphate and sulphuric acid in acidic conditions | |||||||||||

| Cheng [31] |

|

− | 160 g·L−1 Fe(iii) | <1 g·L−1 | 0.56 | 0.4 | − | 1.48 g·mL−1 | 13.5 cp | − | − |

| Huang et al. [51] |

|

11.3% | − | − | 2.7 | − | 12.4% | 1.45 g·cm−3 | − | − | − |

| Jiang et al. [40] |

|

− | 160 g·L−1 [Fe3+] | <1 g·L−1 | − | 0.4 | − | 0.5–1.0 | − | − | − |

| Li and Kang [52] |

|

3.3 wt% | − | 0.0144 wt% | 1.87 | − | − | 1.073 g·mL−1 | − | − | − |

| Moussas and Zouboulis [53] |

|

0.74 mol·L−1 | − | − | 1.78 | 0.5 | − | 1120.71 g·L−1 | − | − | − |

| Zouboulis et al. [15] |

|

47 g·L−1 | 57% | − | 1.4 | 0.35 | − | 1132 g·L−1 | − | 46 mS·cm−1 | −1.9 |

| Zouboulis et al. [38] |

|

52.5 g·L−1 | 38% | − | 1.5 | 0.25 | − | 1182 g·L−1 | − | − | − |

| Modified PFS using reactor | |||||||||||

| Cheng [36] |

|

− | >150 mh·L−1 | <1 mg·L−1 | − | 0–0.6 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Ke et al. [47] |

|

9.64–12.70% | − | 0.11% Fe | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Use of sulphur dioxide (SO2) | |||||||||||

| Zhang et al. [50] |

|

25.34 wt% | − | 0.029 wt% | 2.64 | 16.04 wt% | − | − | − | − | − |

| Butler et al. [48] |

|

≥9.0 wt% | − | ≤0.1 wt% | 2–3 | − | 8.0–12.0 wt% | ≥1.3 g·cm−3 | − | − | − |

On another note, Ke et al. reported a modified method to synthesise PFS, as shown in Figure 4, which generated about 9.64–12.70% of total iron content and 0.11% Fe(ii) [47]. The operating conditions are tabulated in Table 1.

Preparation of experimental equipment for PFS synthesis.

Another PFS preparation method using microbes and organic waste was opted by Wang et al. for water or wastewater treatment [46]. The use of domestic Thiobacillus ferrooxidans resulted in high pH value basicity and total iron content [46]. Despite having a high degree of polymerisation, this method required a longer reaction time. On the other hand, Zhang et al. employed bipolar membrane electrodialysis to produce highly basic PFS [43].

The synthesis of PFS from residual sulphur dioxide (SO2) derived from coal in fossil fuel energy plants has been reported by some previous studies [48,49], and as shown in Figure 5 by Zhang et al. [50]. This may minimise expenses and the presence of nitrates when using hydrogen peroxide [49]. The reactions are as follows:

Schematic diagram of the system for SO2 removal and PFS synthesis as proposed.

Based on the reactions in equations (6)–(8), acid is required for the oxidation of Fe produced via the oxidation of SO2 by sodium chloride(ii) as an oxidant [12]. Sodium chlorate is used to oxidise S(iv) to S(vi), and Fe(ii) to Fe(iii). The resulting acid and water in each equation play their role in the iron oxidation process, and subsequently for hydrolysis, sulphate inclusion, and polymerisation processes.

According to Butler et al., the basicity of the produced PFS decreased with persistent SO2 absorption after Fe(ii) oxidation was completed due to the increase in free acid during the hydrolysis and polymerisation processes [12].

As previously mentioned, several preparation methods have been reported including the traditional process reactor by researchers as mentioned earlier. Several years ago, polymeric iron salts(iii) were developed via different techniques [15,41,43,47]. Table 1 summarises the findings from previous studies for each preparation method described above. Different preparation methods resulted in different PFS characteristics. There are several important indexes in the synthesis of PFS including basicity (OH/Fe molar ratio) as the most important index, density, pH (1% sol), total iron content, and others.

From Table 1, the synthesised PFS contained high concentration of total ion, ferrous ion, and polymerised ion with high acidic conditions. Different concentrations were obtained since the chemicals and reaction conditions applied in synthesising PFS in the laboratory were different. It may be essential to find other oxidising agents for PFS synthesis that may induce high cationic charge in the coagulant to remove pollutants contained in selected wastewater.

1.2 Characteristics of PFS

Generally, PFS is dark brownish red in colour [23,31], more viscous than other commercially available inorganic coagulants, less corrosive [31,41,54], and leaves less iron residue over a wide pH range [41,55]. PFS has the chemical formula [Fe2(OH) n (SO4)3−n/2] m , where n < 2 and m > 10 [38,47]. Table 2 shows the content of analytical grade PFS based on several previous studies.

Properties of analytical grade PFS

| Ref. | Fetotal | Fe(ii) | pH | [OH−]/[Fe+3] | Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetteh and Rathilal [56] | 12.2% w/w | 43.7% w/w | − | − | 673 g·L−1 |

| Shen et al. [57] | 25.0 ± 5.0% (w/w) | − | − | 0.25 | − |

| Huang et al. [51] | ≥11% | ≤0.1% | 2.0–3.0 | − | ≥1.45 g·cm−3 |

Referring to Tables 1 and 2, both the analytical grade and the synthesised PFS fully meet the standard even though they were prepared via different methods. Moreover, all synthesised PFS have low pH, total iron concentration, and stability that are within the national PFS range.

Apart from the properties discussed earlier, physical characteristics in terms of surface morphology, functional groups, elemental content, and others are also discussed. PFS has the morphology of an amorphous material [17,29,43], which forms many aggregates of various sizes and shapes [29,43,47] and smooth-surfaced [58] branch structure [59] characterised using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). Therefore, Zhang et al., concluded that the synthesised PFS is comparable to that of commercial PFS [43] as depicted in Figure 6.

SEM images of (a) analytical grade PFS, and (b–e) synthesised PFS under different operating conditions.

According to Jia et al., PFS displays a distinct cubic and globular rhombohedra shape [17]. It also has a curl-slice and is characterised by an even distribution of long tube-like structures on the surface [60]. Its particle size is between 5 and 10 µm [42] as shown in Figure 7, and in the range of 10–2 µm [47]. The unique morphology reveals the loose porous nature of PFS and may imply that it has a considerable capacity for adsorption [47].

SEM images of PFS synthesised via oxidation, hydrolysis, and polymerisation using pure oxygen gas as oxidant.

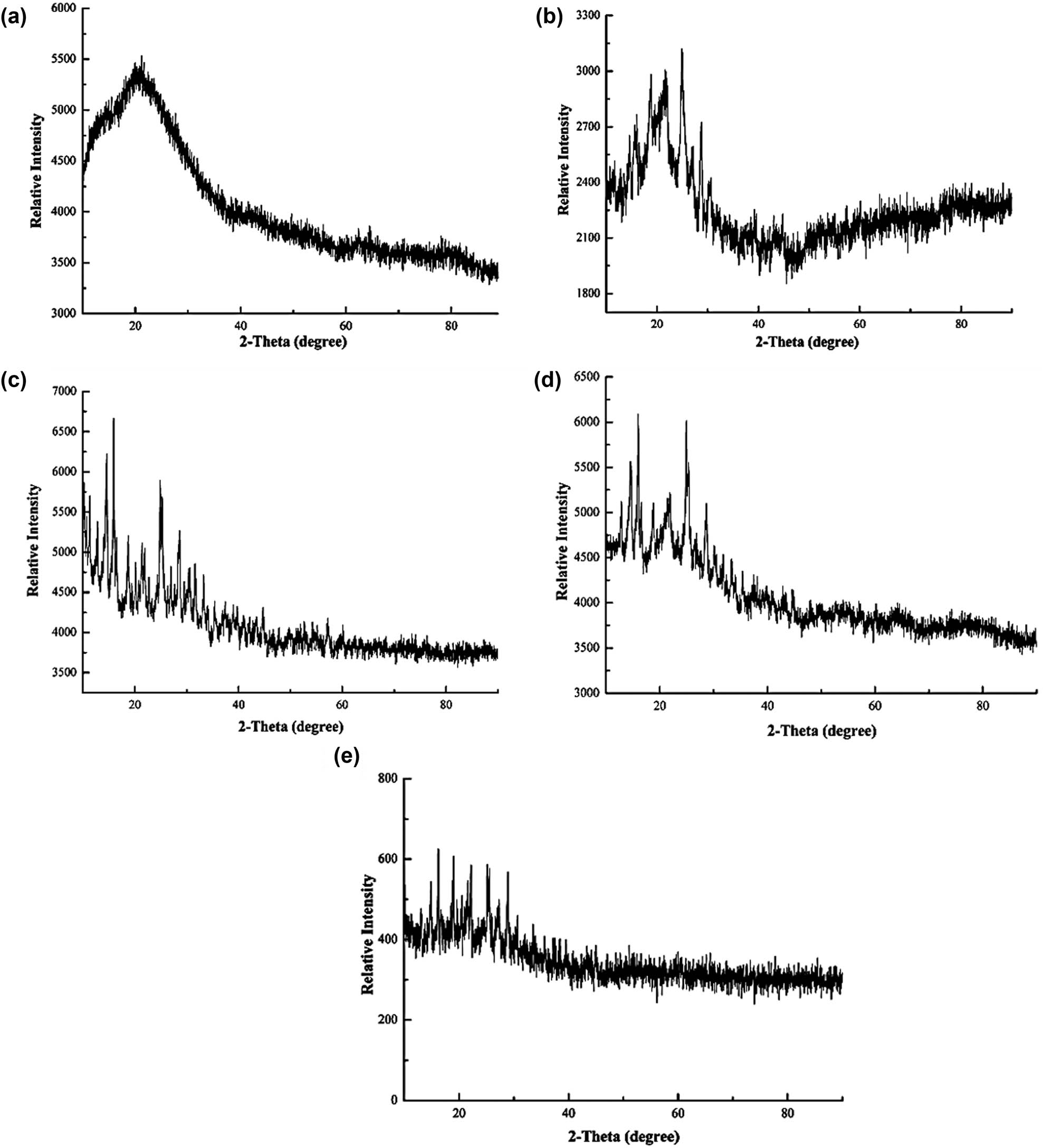

For the X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) patterns, PFS shows an amorphous form with uncertain traces of crystallinity [43,48] at diffraction peaks of 2θ, and peak intensity of 17.51°, 28.57°, and 29.10° [17] as shown in Figure 8 reported by Zhang et al. [43]. In other studies, PFS has been reported to have a crystalline structure at different peaks that varies from a largely amorphous structure to small traces of crystallinity [15,41].

XRD patterns of (a) analytical grade PFS and (b)–(e) synthesised copperas under different conditions.

The chemical composition of the PFS sample is depicted in Figure 9 reported by Wei et al. [58], and the Fourier Transform Infra-Red (FTIR) analysis of PFS is summarised in Table 3. PFS contains both hydroxyl and sulphate groups as stated by Zhan et al. [61]. Previous researchers have reported the stretching vibration of –OH group present at 3,300–3,500 and 1,638–1,641 cm−1 bands referring to the bending vibration of absorbed water [17,43]. For the sulphate group, peaks in the region of 1,008–1,010 cm−1 and 1,160−1,120 cm−1 indicate the formation of polymer [17].

FTIR spectra of PFS.

FTIR analysis of PFS from previous studies

| Group | Wavenumber | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Jia et al. [17] Sodium chlorate was used as oxidant | Zhang et al. [43] Via hydroxide substitution using a membrane | Wei et al. [58] Commercial PFS | |

| −OH groups | 3,300–3,500 cm−1 and 1,638–1,641 cm−1 (referring to the bending vibration of absorbed water, polymerised and crystallised) | 3,250−3,000 cm−1 and 1,628 cm−1 (referring to the stretching vibration of absorbed water or complexes) | 3,381 cm−1 (stretching vibration of OH) and 1,634 cm−1 (bending vibration of –OH groups in the water molecule) |

| Fe–O–Fe | 1,184–1,190 cm−1 and 508–511 cm−1 | 1,000−980 cm−1 (band of Fe–OH) | − |

| Fe–OH–Fe | 1,095–1,099 cm−1 (strong adsorption peaks) | 466 cm−1 | |

| Fe–O | − | − | 598 cm−1 |

| S–O or the O–S–O bonds | 1,008–1,010 cm−1 (strong adsorption peaks, indicating polymer was formed) | 1,160−1,120 cm−1 | − |

| SO4 2− | 626–629 cm−1 (weaker bond) | 680−610 cm−1 (weaker bond) | 1,130 cm−1 |

2 Application of PFS as water coagulant

Numerous studies have been conducted on the use of PFS in controlling the release of arsenic [47], lowering the arsenic concentration that may dissolve in leachate [42], solidifying and stabilising phosphorus, fluorine, and other heavy metals significantly [62], removing silver nanoparticles [63], recovering organic matter [64], and improving acoustic agglomeration efficiency [65]. The application of PFS is extensive in various industries.

In dyeing wastewater treatment, PFS can reduce membrane fouling as it can decrease dissolved organic matter present in the wastewater prior to reverse osmosis treatment [66]. In addition, PFS is able to modify bubble in flotation treatment from distillery wastewater [67], and coagulating mechanism of humic acid [23,31]. In the removal of humic acid by PFS via coagulation examined by Cheng [31], PFS performed well by decreasing the pH value of coagulation due to charge neutralisation between particles and the coagulant. At lower pH, more positively charged Fe(iii) ions are present in the solution [31].

Furthermore, PFS has found its use in industries such as antimony removal in textile wastewater [62,68], phosphorus removal [69,70], arsenic removal [71,72,73], algae removal [74], iron reduction in phosphate-free conditions [75], and total aluminium removal [76]. It is highly efficient in removing pollutants in municipal wastewater [15], slaughterhouse effluent [3], and meat processing effluent [77]. Butler et al., also reported that PFS performed better than traditional aluminium and iron salts in a wide range of applications [12].

Meanwhile, PFS is suitable for use in water treatment plant considering the chemical and physical features of surface water and seasonal pollution [78]. An illustration of coagulation/flocculation process is depicted in Figure 10.

Illustration of coagulation/flocculation process.

When PFS reacts with water, it generates [Fe2(OH)3]3+, [Fe2(OH)2]4+, [Fe3(OH)6]3+, and other complex hydroxyl ions [36,47]. The presence of these polymeric species will enhance the charge neutralisation capability as inorganic polymeric flocculants have a higher cationic charge [79], and greater molecular weight; therefore, they are more effective at lower doses [80]. Higher cationic charge leads to increased surface activity and improves their capacity to neutralise the charge of suspended particles [38]. According to Zhang et al., the presence of these ions [43] can decrease chemical oxygen demand (COD) [81], BOD, turbidity [49], and heavy metal [82] in water through hydrolysis, adsorption, and coagulation/flocculation processes. Dissolved organic matter may be removed from wastewater with excellent efficiency using PFS [83].

The solubility of PFS depends on several factors, including the concentration of PFS, the pH solution, and the presence of other dissolved substances. At low concentrations and/or acidic pH, PFS is highly soluble in water. However, as the concentration of PFS and/or the pH of the solution increases, PFS can become less soluble and may form precipitates. This is because as the pH increases, hydroxide species may form which can combine with PFS to form insoluble precipitates. One study has found that the solubility of PFS decreased with increasing pH, with the solubility dropping from 32.5 g·L−1 at pH 2 to 0.65 g·L−1 at pH 11 [84]. This decrease in solubility was attributed to the formation of insoluble hydroxide species at higher pH values. Additionally, the presence of other dissolved substances such as phosphate ions or natural organic matter (NOM) can also decrease the solubility of PFS by causing it to form precipitates. Zhang et al. has investigated the effect of other dissolved substances on the solubility of PFS and found that the presence of phosphate ions and NOM could decrease the solubility of PFS, potentially leading to the formation of precipitates [85].

PFS acts by neutralising the charge on suspended particles and destabilising them through the formation of floc in coagulation mechanism. The hydrolysis of PFS leads to the formation of various species, including Fe(OH)2+, Fe2(OH)2 4+, Fe4(OH)12 4+, and FE(OH)3 which can all contribute to the coagulation process [86]. The specific conditions under which hydrolysed soluble compound and Fe(OH)3 precipitate form will depend on the concentration of PFS and the pH of the solution [86]. At low concentrations and acidic pH, hydrolysed soluble compounds will be the dominant species. As the concentration of PFS and/or the pH of the solution increases, the solubility of PFS will decrease, leading to the formation of Fe(OH)3 precipitates [84,85,86]. The exact pH and dosage conditions under which this occurs will depend on the specific characteristics of the water being treated and the desired treatment outcomes.

In the coagulation/flocculation process, PFS can reduce the complex reactions resulting from the iron–salt hydrolysis, allowing easier and more precise control of the coagulation process [23]. PFS is more effective in removing different types of pollutants as summarised in Table 4. It is presumed that the removal of organics by PFS mostly occurs through adsorption, although charge neutralisation is weak in the near neutral region, where the removal is substantially higher [87]. Turhan and Turgut also claimed that PFS is an excellent adsorbent and decolouriser [88]. It is less sensitive to temperature and pH, and it works well over a pH range of 4–11 [47], and changes in dosage [36]. As stated by Xing and Sun, iron salts can coagulate in a wider pH range than aluminium salts, produce heavier flocs, and are less toxic if overdosed [37]. It often gives the best performance when the solution is acidic as revealed by Sahu and Chaudhari [89].

Application of PFS in different industrial effluent treatments

| Type of wastewater | Experimental conditions | Removal efficiency (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipal water | Dosage: 2 mg·L−1 | Turbidity (86.6%) | Butler et al. [12] |

| Temp.: 28–30°C | |||

| pH: 7.6–7.9 | |||

| Groundwater sample | Dosage: 0.10 g·L−1 | Arsenic (95%) | Cui et al. [71] |

| Secondary wastewater effluent | Dosage: 20 mg·L−1 | DOC (25.8%) | Huang et al. [91] |

| pH: 7.0 | UV254 (32.6%) | ||

| Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (30%) | |||

| Algae containing wastewater | Dosage: 20 mmol Fe3+ L−1 | Total cell (87%) | Jiang et al. [40] |

| pH: 8.5 | DOC (63%) | ||

| Turbidity (70%) | |||

| Upland coloured water | Dosage: 6 mg·L−1 | Colour (92%) | Jiang et al. [92] |

| pH: 4.0 | UV254 (83.2%) | ||

| DOC (80.3%) | |||

| Sanitary wastewater | Dosage: 100 mg·L−1 | Total phosphorus (78.99%) | Li et al. [70] |

| pH: 6 | |||

| Stir intensity: 250 rpm | |||

| Mixing time: 90 s | |||

| Landfill leachate | Dosage: 1.0 kg·m−3 | COD (63%) | Li et al. [93] |

| Landfill leachate | Dosage: 0.3 g Fe3+·L−1 | COD (70%) | Li et al. [28] |

| SS (93%) | |||

| Turbidity (97%) | |||

| Toxicity (74%) | |||

| Landfill leachate | Dosage: 8 g·L−1 | CODCr (56.38%) | Liu et al. [94] |

| pH: 6.0 | Colour (63.38%) | ||

| Turbidity (89.79%) | |||

| Humic acid (53.64%) | |||

| Textile wastewater | Dosage: 0.75 mM Fe | Antimony (77.6%) | Liu et al. [68] |

| pH: 5.8−6.2 | |||

| Temp.: 25°C | |||

| Stirring: 2 min, 200 rpm and 10 min, 80 rpm | |||

| Settling time: 30 min | |||

| Domestic water treatment | Dosage: 65 mg·L−1 | Turbidity (100%) | Lloyd et al. [49] |

| pH: 4.0 | |||

| Kaolin-humic acid | Dosage: 4 mg·L−1 | Turbidity (98%) | Moussas and Zouboulis [60] |

| Synthetic wastewater | Fe/P molar ratio: 1.61 | Total phosphorus (97.0%) | Ruihua et al. [69] |

| pH: 7.03 | |||

| stirring: 3 min, 160 rpm and 5 min, 30 rpm | |||

| settling time: 30 min | |||

| Water treatment | pH: 7.5 | Silver nanoparticles (76%) | Sun et al. [63] |

| Oil refinery wastewater | Dosage: 50 mg·L−1 | Turbidity (85%) | Tetteh and Rathilal [56] |

| Total suspended solid (74%) | |||

| COD (83%) | |||

| Soap oil and Grease (84%) | |||

| Textile wastewater | Dosage: 500 mg·L−1 | COD (41.4%) | Tianzhi et al. [83] |

| SS (5.7%) | |||

| Water treatment | Dosage: 0.3 mM | Titanium dioxide nanoparticle (84%) | Wang et al. [95] |

| Water treatment | pH: 1.5 | COD (70%) | Wang et al. [46] |

| Dosage: 0.5 g·L−1 | Colour (90%) | ||

| Zn2+(99%) | |||

| Kaolin prepared wastewater | Dosage: 16 mg·L−1 | Turbidity (90.36%) | Wei et al. [58] |

| Surface water | Dosage: 5 mg·L−1 | Turbidity (90%) | Cheng [36] |

| pH: 7 | |||

| Water-based seed coating wastewater | Dosage: 1.5 g·L−1 | Colour (96.8%) | Wen et al. [2] |

| pH: 8.0 | COD (83.4%) | ||

| Sewage wastewater | Dosage: 136 mg·L−1 | SCOD: (69.4%) | Xing et al. [96] |

| TP (92.9%) | |||

| TN (45.0%) | |||

| Antibiotic fermentation wastewater | Dosage: 200 mg·L−1 | Colour (66.6%) | Xing and Sun [37] |

| pH: 4.0 | COD (72.4%) | ||

| Water treatment | Dosage: 40 mg·L−1 | Turbidity (85.1%) | Yang et al. [97] |

| Sewage wastewater | Dosage: 25 mg·L−1 | UV254 (23.0%) | Zhao and Li [98] |

| COD (70.3%) | |||

| TP (91.6%) | |||

| PO4-P (87.0%) | |||

| Cotton pulp wastewater | Dosage: 800 mg·L−1 | COD (94.85%) | Zhang et al. [50] |

| pH: 7.6 | |||

| Paper making wastewater | Dosage: 500 mg·L−1 | COD (82.20%) | |

| pH: 7.0 | |||

| Purple dyeing wastewater | Dosage: 2 mL·L−1 | Colour (76.18%) | Huang et al. [51] |

| pH: 7–9 | SS (92.23%) | ||

| COD (71.43%) | |||

| Biologically pretreated molasses wastewater | Dosage: 5.5 g·L−1 | COD (80%) | Liang et al. [99] |

| Colour (94%) |

As tabulated in Table 4, PFS has the ability in removing numerous pollutants considering its characteristics which are discussed further in the subsequent sections. In general, PFS consists of high positive charge of iron(iii) ions, and also its surface and charge neutralisation capacity. Therefore, these positively charged ions will attract organic matter or suspended particles with opposite charged ions to come into contact, neutralise, and form flocs. The neutralised particles form a larger and denser floc due to the bridging effect of the PFS. PFS polymers form bridges between the neutralised particles, resulting in the formation of larger aggregates. These aggregates can settle faster due to their increased weight [90]. As a result, pollutant present in water and wastewater may be removed.

To enhance the coagulation/flocculation process in wastewater treatment, the combination of different types of coagulants has been attempted. In recent studies and advances in coagulation/flocculation methods to treat polluted water, several researchers have combined inorganic–inorganic, organic–natural, and inorganic–organic coagulants for effective pollutant removal [100]. Table 5 shows the performance of PFS combined with other chemical coagulants. Due to the growing market need for effective wastewater treatment, hybrid coagulants are also used during the coagulation/flocculation phase [16]. The combination of PFS with other chemicals or natural coagulants has high potential in treating water or wastewater. This is due to their greater effectiveness and cheaper cost compared to inorganic coagulants and organic flocculants [101].

Previous studies of composite polymeric iron sulphate for different industrial effluent treatments

| Coagulant | Optimum dosage | Removal (%) | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COD | Turbidity | SS | Phosphate | |||

| PFS + flocculant (FO4440SSH) | (80 mg·L−1 + 6 mg·L−1) | − | − | 90.51 | − | Zhang et al. [107] |

| Polyferric zinc sulphate | 12 mg·L−1 | − | 93.42 | − | − | Wei et al. [58] |

| Polymeric aluminium ferric sulphate | 45 mg·L−1 | 82.8 | 98.2 | − | − | Zhu et al. [1] |

| Polymeric aluminium ferric sulphate | 45 mg·L−1 | 83.6 | − | − | − | Zhu et al. [59] |

| Polyferric silicate sulphate | 75 mg·L−1 | − | 90 | − | 98–99 | Moussas and Zouboulis [105] |

For example, PFS-polyacrylamide [53], polyferric iron-based coagulant [102], poly-ferric-titanium-silicate-sulphate [103], polymer + PFS [57,60,104], polyferric silicate sulphate [52,105,106], PFS with flocculant [107], polyferric phosphatic sulphate [108], polymeric aluminium ferric sulphate [59], and polyferric-zinc-sulphate [58] also receive great attention in water or wastewater treatment. They have shown increased efficiency in removing COD, turbidity, SS, phosphate, and other pollutants. In other applications, PFS was combined with Ca(OH) for the treatment of spent nuclear fuel debris [109], and calcified with CaCl2 to dissolve inorganic phosphorus of sediment [110].

2.1 Effect of operating parameters on coagulation/flocculation process

The removal of NOM and tiny particles from drinking water is one of the crucial procedures involving the coagulation process [111]. The coagulation/flocculation process is an effective and simple method for water and wastewater treatment. Some of the factors that influence the effectiveness of the coagulation/flocculation process are the coagulant type and dose, pH, mixing speed, and time as well as temperature and settling time. Optimum conditions for the coagulation/flocculation process result in acceptable discharge limits and eventually can be discharged to nearby watercourses.

2.1.1 Effect of dosage

One of the imperative parameters in the coagulation/flocculation process is the dosage of coagulant. From Table 4, it can be concluded that different water or wastewater samples require different optimum coagulant dosages for treatment. This is due to the differences in organic matter or pollutant contents in the water or wastewater in terms of type and load of impurities. Alazaiza et al. described that there are three levels of conditions of coagulant dosage, namely, optimal dosage, under dosage, and overdosage, which are different from each other [112]. The optimal dosage refers to the condition when the coagulant aggregates colloidal particles to achieve a higher pollutant removal efficiency. Meanwhile, a low dosage promotes the formation of colloidal particles, but overdose may pollute the wastewater by increasing the level of pollutants as well as treatment costs [112].

Increasing the dosage will increase the removal efficiency [44]. According to Alazaiza et al., high coagulant dosage results in increased coagulation/flocculation effectiveness for water or wastewater treatment [112]. Moreover, Butler et al., reported higher turbidity removal at lower dosage of PFS [12]. In a study conducted by Saxena et al., it was revealed that PFS only required a lower dosage to remove algae and algal-derived organic matter in a large scale [87]. A lower dosage of PFS is required for wastewater pretreatment process but depends on the source of wastewater [15,113].

2.1.2 Effect of initial pH value

Another important parameter in the coagulation/flocculation process is the initial pH value. In this process, pH needs to be adjusted as it affects the removal of pollutants in water and wastewater [27]. As summarised in Table 4, the optimum pH value in treating water or wastewater is in the range of pH 5–7. Cheng asserted that PFS has a wide range of optimum pH values [36]. Increasing the initial pH value will increase the removal of pollutants using poly-ferric based coagulants [103].

The removal of pollutants using PFS can decrease the coagulation pH owing to the availability of more positively charged Fe(iii) ions with more neutral sites on the surface of humic acid at lower pH levels [31]. PFS can also coagulate at low pH through charge neutralisation [23]. When the pH value is increased, the complex formation of PFS by hydroxide ions will decrease, thus causing the pollutant adsorption onto the flocs of Fe(OH)3 or Fe(OH)4 − become difficult [23].

2.1.3 Effect of mixing speed and time

In the coagulation/flocculation process, preferable mixing speed and time can ensure that the coagulants used coagulate well with the suspended particles contained in the water or wastewater samples. In a study by Yukselen and Gregory, it was reported that rapid mixing was in the range of 70–75 rpm for 0.5–3 min, while slow mixing required a range of 30–150 rpm for 5–30 min to promote floc formation [114]. If the speed is too high, the flocs formed will break and result in a high turbidity content in the water [115]. It is necessary to identify the optimum mixing conditions for removing pollutants. A study on wastewater treatment revealed that the phosphorus removal was higher when PSF was subjected to rapid mixing at the coagulation speed and time of 160 rpm and 3 min, respectively, and slow mixing at 30 rpm speed and 5 min time [69]. The PFS disperses equally all over the solution and then collide with each other and form flocs [16].

2.1.4 Effect of temperature

Temperature directly influences floc size, strength, and ability to reassemble after a shear break-up [16]. The influence of temperature may raise the kinetic energy of iron particles, promoting further collisions with organic particles containing negatively charged ions, and therefore boosting the effectiveness of the coagulation process [116]. Low temperature is not ideal for flocculation [117], mostly because the viscosity of the solution increases as the temperature decreases [16]. An increase in temperature is favourable for the formation of larger flocs [118].

2.2 Production of flocs during coagulation/flocculation

The generation of flocs using PFS as coagulant is more stable [31], with floc breakdown occurring less often during the growth phase, as stated by Zhao et al. [119]. This induces faster floc development resulting in faster settling rates [40], and it will be easily removed during the filtration process as less iron residue is formed [36]. The flocs formed from the use of ferric salts are larger than those using aluminium salts [120], and are more compact [68]. The amount of sludge formed during the sedimentation process is small in the range of 0–22 g·kg−1 of total solid sludge [121,122].

Several studies have been conducted on the structure and elemental content of flocs formed using PFS as a coagulant. For instance, Liang et al. conducted SEM analysis and found that the flocs formed were mostly amorphous and random, and the coagulated flocs have uneven sheet-like forms of various sizes (Figure 11) [99]. Figure 12 displays the SEM image of precipitates form with larger aggregates compared to other iron-based coagulants, and the precipitates have the largest surface area, and thus can adsorb various metal ions such as C, O, Na, and other elements [90].

SEM image of the coagulated floc formed from PFS (synthesised via catalytic oxidation using sodium chlorate as oxidant) at 500× magnification.

SEM image of commercial PFS precipitates at 4,000× magnification.

As discussed earlier, the flocs formed from PFS are stable and larger in size at optimum treatment conditions. Thus, PFS can be used as coagulant in treating various types of water or wastewater due to its effectiveness in removing pollutants, and the flocs formed will be easily disposed of.

3 Limitation and future works

PFS has been discovered for its efficiency in the removal of phosphorus, arsenic, algal, total aluminium, turbidity, colour, and heavy metals. The synthesis of PFS from acid waste from the steel and dyestuff industries allows a significant reduction in production costs, which is another benefit of PFS application [36]. However, PFS has certain drawbacks resulting in a smaller market share [17]. Since PFS has high acidity, it may easily lower the pH of the water, further damaging the coagulation process, and possibly contaminating the equipment [17]. PFS-based water treatment processes may require the use of chemicals, such as pH adjusters and cleaning agents, which can have negative environmental impacts if not properly managed. Chemical use can contribute to water pollution and the accumulation of harmful chemicals in the environment [123]. The addition of PFS can affect its pH and potentially lead to changes in water quality that can negatively impact aquatic ecosystems and wildlife [124]. PFS-based water treatment processes require energy to operate, which can contribute to greenhouse emissions and climate changes. The energy required for water treatment can vary depending on the specific process and location but can be significant [125]. In terms of cost, it may vary depending on various factors such as supplier, quantity, and location. In 2023, the average cost of PFS ranges from $0.70 to $1.50 per kilogram, depending on the specific grade and quantity purchased [126]. The cost of using PFS in water treatment can vary depending on the specific application and system design. However, some general cost estimates for PFS-based water treatment processes including coagulation and flocculation were $0.05–0.10 and $0.10–0.30 per 1,000 gallons treated, respectively [127]. Overall, while PFS can be an effective coagulant for water and wastewater treatment application, its use should be carefully considered in light of its economic and environmental impacts. More research is needed to synthesise PFS that is promising and acceptable for use in industry.

4 Conclusion

Polymeric iron-based coagulant or PFS is reviewed in this study in terms of its preparation methods and their effects on the coagulation/flocculation process for treating various types of water or wastewater. Based on previous studies, PFS exhibits an amorphous structure with small traces of crystallinity, and the presence of hydroxyl and sulphate as functional groups. PFS has the potential to be used as a coagulant as it contains higher polymeric species that can aid the coagulation/flocculation process. As a result, this polymeric form of iron-based coagulant is effective in removing pollutants in the wastewater. It is only required in small dosages, and can operate over a wide range of pH values depending on the nature of the water or wastewater. The use of this coagulant solely or in combination with other types of coagulants has a promising potential in the removal of pollutants.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Universiti Malaysia Terengganu for providing funding for this project (UMT/ID2RG/2023) and Venator Asia Sdn Bhd for their contribution and support. This research publication was supported by TUIASI from the University Scientific Research Fund (FCSU).

-

Funding information: Overall research was funded by Universiti Malaysia Terengganu ((UMT/ID2RG/2023) and this research publication was supported by TUIASI from the University Scientific Research Fund (FCSU).

-

Author contributions: Nurul Aqilah Mohamad, Sofiah Hamzah, and Nur Hanis Hayati Hairom – writing and methodology. Mohd Salleh Amri Zahid, Khairol Annuar Mohd Ali, and Che Mohd Ruzaidi Ghazali – data curation, visualisation, and supervision. Andrei Victor Sandu, Mohd Mustafa al Bakri Abdullah, and Petrica Vizureanu – validation, funding acquisition, and review. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Zhu, G., H. Zheng, W. Chen, W. Fan, P. Zhang, and T. Tshukudu. Preparation of a composite coagulant: Polymeric aluminum ferric sulfate (PAFS) for wastewater treatment. Desalination, Vol. 285, 2012, pp. 315–323.10.1016/j.desal.2011.10.019Search in Google Scholar

[2] Wen, C., X. Xu, Y. Fan, C. Xiao, and C. Ma. Pretreatment of water-based seed coating wastewater by combined coagulation and sponge-iron-catalyzed ozonation technology. Chemosphere, Vol. 206, 2018, pp. 238–247.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.04.172Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Aguilar, M. I., J. Sáez, M. Lloréns, A. Soler, and J. F. Ortuño. Microscopic observation of particle reduction in slaughterhouse wastewater by coagulation-flocculation using ferric sulphate as coagulant and different coagulant aids. Water Resource, Vol. 37, No. 9, 2003, pp. 2233–2241.10.1016/S0043-1354(02)00525-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Abdulsalam, M., H. C. Man, A. I. Idris, K. F. Yunos, and Z. Z. Abidin. Treatment of palm oil mill effluent using membrane bioreactor: Novel processes and their major drawbacks. Water (Switzerland), Vol. 10, No. 9, 2018, id. 1165.10.3390/w10091165Search in Google Scholar

[5] Ali, A., A. W. C. Ing, W. R. W. Abdullah, S. Hamzah, and F. Azaman. Preparation of high-performance adsorbent from low-cost agricultural waste (peanut husk) using full factorial design: Application to dye removal. Biointerface Research in Applied. Chemistry, Vol. 10, No. 6, May 2020, pp. 6619–6628.10.33263/BRIAC106.66196628Search in Google Scholar

[6] Hamzah, S., N. I. Yatim, M. Alias, A. Ali, N. Rasit, and A. Abuhabib. Extraction of hydroxyapatite from fish scales and its integration with rice husk for ammonia removal in aquaculture wastewater. Indonesian Journal of Chemistry, Vol. 19, No. 4, August 2019, id. 1019.10.22146/ijc.40907Search in Google Scholar

[7] Mustapha, R., A. Ali, G. Subramaniam, A. A. Zuki, M. Awang, M. H. Harun, et al. Removal of malachite green dye using oil palm empty fruit bunch as a low-cost adsorbent. Biointerface Research in Applied Chemistry, Vol. 11, No. 6, 2001, pp. 14998–15008.10.33263/BRIAC116.1499815008Search in Google Scholar

[8] Harun, M. H. C., M. I. Ahmad, A. Jusoh, A. Ali, and S. Hamzah. Rapid-slow sand filtration for groundwater treatment: effect of filtration velocity and initial head loss. International Journal of Integrated Engineering, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2022, pp. 276–286.10.30880/ijie.2022.14.01.026Search in Google Scholar

[9] Pandey, N., R. Gusain, and S. Suthar. Exploring the efficacy of powered guar gum (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba) seeds, duckweed (Spirodela polyrhiza), and Indian plum (Ziziphus mauritiana) leaves in urban wastewater treatment. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 264, 2020, id. 121680.10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121680Search in Google Scholar

[10] Hasan, M., M. Khalekuzzaman, N. Hossain, and M. Alamgir. Anaerobic digested effluent phycoremediation by microalgae co-culture and harvesting by Moringa oleifera as natural coagulant. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 292, 2021, id. 126042.10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126042Search in Google Scholar

[11] Mohamad, N. A., S. Hamzah, M. H. Harun, A. Ali, N. Rasit, M. Awang, et al. Integration of copperas and calcium hydroxide as a chemical coagulant and coagulant aid for efficient treatment of palm oil mill effluent. Chemosphere, Vol. 281, May 2021, id. 130873.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130873Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Butler, A. D., M. Fan, R. C. Brown, J. Van Leeuwen, S. Sung, and B. Duff. Pilot-scale tests of poly ferric sulfate synthesized using SO2 at Des Moines water works. Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification, Vol. 44, No. 3, 2005, pp. 413-419.10.1016/j.cep.2004.06.003Search in Google Scholar

[13] Verma, A. K., R. R. Dash, and P. Bhunia. A review on chemical coagulation/flocculation technologies for removal of colour from textile wastewaters. Journal of Environmental Management, Vol. 93, No. 1, 2012, pp. 154–168.10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.09.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] He, Z., X. Wang, Y. Luo, Y. Zhu, X. Lai, J. Shang, et al. Effects of suspended particulate matter from natural lakes in conjunction with coagulation to tetracycline removal from water. Chemosphere, Vol. 277, 2021, id. 130327.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130327Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Zouboulis, A. I., P. A. Moussas, and F. Vasilakou. Polyferric sulphate: Preparation, characterisation and application in coagulation experiments. Journal of Hazardous Material, Vol. 155, No. 3, July 2008, pp. 459–468.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.11.108Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Abujazar, M. S. S., S. U. Karaağaç, S. S. Abu Amr, M. Y. D. Alazaiza, and M. J. Bashir. Recent advancement in the application of hybrid coagulants in coagulation-flocculation of wastewater: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 345, 2022, id. 131133.10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131133Search in Google Scholar

[17] Jia, D., M. Li, G. Liu, P. Wu, J. Yang, Y. Li, et al. Effect of basicity and sodium ions on stability of polymeric ferric sulfate as coagulants. Colloids and Surfaces A Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, Vol. 512, 2017, pp. 111–117.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2016.10.021Search in Google Scholar

[18] Dayarathne, H. N. P., M. J. Angove, R. Aryal, H. Abuel-Naga, and B. Mainal. Removal of natural organic matter from source water: Review on coagulants, dual coagulation, alternative coagulants, and mechanisms. Journal of Water Process Engineering, Vol. 40, 2021, id. 101820.10.1016/j.jwpe.2020.101820Search in Google Scholar

[19] Zhou, L., H. Zhou, and X. Yang. Preparation and performance of a novel starch-based inorganic/organic composite coagulant for textile wastewater treatment. Separation and Purification Technology, Vol. 210, August 2018, 2019, pp. 93–99.10.1016/j.seppur.2018.07.089Search in Google Scholar

[20] Gao, B. Y., Y. Wang, Q. Y. Yue, J. C. Wei, and Q. Li. Color removal from simulated dye water and actual textile wastewater using a composite coagulant prepared by ployferric chloride and polydimethyldiallylammonium chloride. Separation and Purification Technology, Vol. 54, No. 2, 2007, pp. 157–163.10.1016/j.seppur.2006.08.026Search in Google Scholar

[21] Lal, K. and A. Gar. Effectiveness of synthesized aluminum and iron based inorganic polymer coagulants for pulping wastewater treatment. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, Vol. 7, No. 5, 2019, id. 103204.10.1016/j.jece.2019.103204Search in Google Scholar

[22] Cao, B., B. Gao, X. Liu, M. Wang, Z. Yang, and Q. Yue. The impact of pH on floc structure characteristic of polyferric chloride in a low DOC and high alkalinity surface water treatment. Water Research, Vol. 4518, 2011, pp. 6181–6188.10.1016/j.watres.2011.09.019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Cheng, W. P. and F. H. Chi. A study of coagulation mechanisms of polyferric sulfate reacting with humic acid using a fluorescence-quenching method. Water Research, Vol. 3618, 2022, pp. 4583–4591.10.1016/S0043-1354(02)00189-6Search in Google Scholar

[24] Wei, J., B. Gao, Q. Yue, Y. Wang, W. Li, and X. Zhu. Comparison of coagulation behavior and floc structure characteristic of different polyferric-cationic polymer dual-coagulants in humic acid solution. Water Research, Vol. 43, No. 3, 2009, pp. 724–732.10.1016/j.watres.2008.11.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Mohammad Ilias, M. K., M. S. Hossain, R. Ngteni, A. Al-Gheethi, H. Ahmad, F. M., Omar, et al. Environmental remediation potential of ferrous sulfate waste as an eco-friendly coagulant for the removal of NH3-N and COD from the rubber processing effluent. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Vol. 18, No. 23, 2021, pp. 1–16.10.3390/ijerph182312427Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Harun, M. H. C., F. Fisol, S. Hamzah, and F. Azaman. Integration of iron coagulant, copperas and calcium hydroxide for low-cost groundwater treatment in Kelantan, Malaysia. Letters in Applied NanoBioScience, Vol. 10, No. 4, 2021, pp. 2869–2876.10.33263/LIANBS104.28692876Search in Google Scholar

[27] Mohamad, N. A., S. Hamzah, M. H. Harun, A. Ali, N. Rasit, M. Awang, et al. Copperas as iron-based coagulant for water and wastewater treatment: A review. Biointerface Research in Applied Chemistry, Vol. 12, No. 3, 2022, pp. 4155–4176.10.33263/BRIAC123.41554176Search in Google Scholar

[28] Li, W., T. Hua, Q. Zhou, S. Zhang, and F. Li. Treatment of stabilized landfill leachate by the combined process of coagulation/flocculation and powder activated carbon adsorption. Desalination, Vol. 264, No. 1–2, 2010, pp. 56–62.10.1016/j.desal.2010.07.004Search in Google Scholar

[29] Wang, Q., Z. Wei, X. Yi, J. Tang, C. Feng, and Z. Dang. Biogenic iron mineralization of polyferric sulfate by dissimilatory iron reducing bacteria: Effects of medium composition and electric field stimulation. Science of the Total Environment, Vol. 684, 2019, pp. 466–475.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.322Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Rong, H., B. Gao, J. Li, B. Zhang, S. Sun, Y. Wang, et al. Floc characterization and membrane fouling of polyferric-polymer dual/composite coagulants in coagulation/ultrafiltration hybrid process. Journal of Colloid Interface Science, Vol. 412, 2013, pp. 39–45.10.1016/j.jcis.2013.09.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Cheng, W. P. Comparison of hydrolysis/coagulation behavior of polymeric and monomeric iron coagulants in humic acid solution. Chemosphere, Vol. 47, No. 9, 2002, pp. 963–969.10.1016/S0045-6535(02)00052-8Search in Google Scholar

[32] Gao, B. and Q. Yue. Effect of SO42−/Al3+ ratio and OH−/Al3+ value on the characterization of coagulant poly-aluminum-chloride-sulfate (PACS) and its coagulation performance in water treatment. Chemosphere, Vol. 61, No. 4, 2005, pp. 579–584.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.03.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Zhao, Y., S. Phuntsho, B. Gao, and H. Shon. Polytitanium sulfate (PTS): Coagulation application and Ti species detection. Journal of Environmental Science (China), Vol. 52, 2017, pp. 250–258.10.1016/j.jes.2016.04.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Zhou, Y., L. Wu, Y. Li, and J. Bai. Analysis of synthesis structures and flocculation stability of a polyphosphate ferric sulfate solid. Chemica Engineering Journal Advances, Vol. 9, 2022, id. 100202.10.1016/j.ceja.2021.100202Search in Google Scholar

[35] Gregory, J. and L. Rossi. Dynamic testing of water treatment coagulants. Water Science and Technology: Water Supply, Vol. 1, No. 4, 2001, pp. 65–72.10.2166/ws.2001.0068Search in Google Scholar

[36] Cheng, W. P. Hydrolysis characteristic of polyferric sulfate coagulant and its optimal condition of preparation. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical Engineering Aspects, Vol. 182, No. 1–3, 2001, pp. 57–63.10.1016/S0927-7757(00)00602-6Search in Google Scholar

[37] Xing, Z. P. and D. Z. Sun. Treatment of antibiotic fermentation wastewater by combined polyferric sulfate coagulation, Fenton and sedimentation process. Journal of Hazardous Materials, Vol. 168, No. 2–3, 2009, pp. 1264–1268.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.03.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Zouboulis, Z., V. Fotini, and M. Panagiotis. Synthesis, characterisation and application in coagulation experiments of polyferric sulphate. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, Vol. 92, 2006, pp. 133–142.10.2495/WM060151Search in Google Scholar

[39] Graham, N. J. D. and J. Jiang. Preparation and uses of polyferric sulphate, US Pat., 5,785,862, 1998.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Jiang, J. Q., N. J. D. Graham, and C. Harward. Comparison of polyferric sulphate with other coagulants for the removal of algae and algae-derived organic matter. Water Science and Technology, Vol. 2711, 1993, pp. 221–230.10.2166/wst.1993.0280Search in Google Scholar

[41] Fan, M., S. Sung, R. C. Brown, T. D. Wheelock, and F. C. Laabs. Synthesis, characterization, and coagulation of polymeric ferric sulfate. Journal of Environmental Engineering, Vol. 128, No. 6, 2002, pp. 483–490.10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9372(2002)128:6(483)Search in Google Scholar

[42] Ke, P., K. Song, A. Ghahreman, and Z. Liu. Improvement of scorodite stability by addition of crystalline polyferric sulfate. Hydrometallurgy, Vol. 185, February, 2019, pp. 162–172.10.1016/j.hydromet.2019.02.012Search in Google Scholar

[43] Zhang, X., X. Wang, Q. Chen, Y. Lv, X. Han, Y. Wei, et al. Batch preparation of high basicity polyferric sulfate by hydroxide substitution from bipolar membrane electrodialysis. ACS Sustainable Chemistry and Engineering, Vol. 5, No. 3, 2017, pp. 2292–2301.10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b02625Search in Google Scholar

[44] Gao, B., B. Liu, T. Chen, and Q. Yue. Effect of aging period on the characteristics and coagulation behavior of polyferric chloride and polyferric chloride-polyamine composite coagulant for synthetic dying wastewater treatment. Journal of Hazardous Materials, Vol. 187, No. 1–3, 2011, pp. 413–420.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.01.044Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Jiang, J. Q. and N. J. D. Graham. Observations of the comparative hydrolysis/precipitation behaviour of polyferric sulphate and ferric sulphate. Water Resources, Vol. 32, No. 3, 1998, pp. 930–935.10.1016/S0043-1354(97)83364-7Search in Google Scholar

[46] Wang, H., X. Min, L. Chai, and Y. Shu. Biological preparation and application of poly-ferric sulfate flocculant. Transactions Nonferrous Metals Society of China (English Edition), Vol. 21, No. 11, 2011, pp. 2542–2547.10.1016/S1003-6326(11)61048-0Search in Google Scholar

[47] Ke, P., K. Song, and Z. Liu. Encapsulation of scorodite using crystalline polyferric sulfate precipitated from the Fe(II)-SO42−-O2-H2O system. Hydrometallurgy, Vol. 180, May, 2018, pp. 78–87.10.1016/j.hydromet.2018.07.011Search in Google Scholar

[48] Butler, A. D., M. Fan, R. C. Brown, A. T. Cooper, J. H. van Leeuwen, and S. Sung. Absorption of dilute SO2 gas stream with conversion to polymeric ferric sulfate for use in water treatment. Chemical Engineering Journal, Vol. 98, No. 3, 2004, pp. 265–273.10.1016/j.cej.2003.10.007Search in Google Scholar

[49] Lloyd, H., A. T. Cooper, M. Fan, R. C. Brown, J. Sawyer, H. van Leeuwen, et al. Pilot plant evaluation of PFS from coal-fired power plant waste. Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification, Vol. 46, No. 3, 2007, pp. 257–261.10.1016/j.cep.2006.05.017Search in Google Scholar

[50] Zhang, Y., S. Guo, J. Zhou, C. Li, and G. Wang. Flue gas desulfurization by FeSO4 solutions and coagulation performance of the polymeric ferric sulfate by-product. Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification, Vol. 49, No. 8, 2010, pp. 859–865.10.1016/j.cep.2010.06.002Search in Google Scholar

[51] Huang, Y., B. Zang, C. Wu, T. Wu, and M. Xu. Study on the preparation and coagulation effect of PFS. 2011 International Conference on Remote Sensing, Environment and Transportation Engineering RSETE 2011 - Proceedings, 2011, pp. 3584–3587.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Li, S. and Y. Kang. Impacts of key preparation factors on polymerization and flocculation performance of polyferric silicate sulfate (PFSiS). Colloids Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, Vol. 635, 2022, id. 128109.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2021.128109Search in Google Scholar

[53] Moussas, P. A. and A. I. Zouboulis. A new inorganic-organic composite coagulant, consisting of Polyferric Sulphate (PFS) and Polyacrylamide (PAA). Water Research, Vol. 4314, 2009, pp. 3511–3524.10.1016/j.watres.2009.05.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[54] Shi, Y., M. Fan, R. C. Brown, S. Sung, and J. Van Leeuwen. Comparison of corrosivity of polymeric sulfate ferric and ferric chloride as coagulants in water treatment. Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification, Vol. 43, No. 8, 2004, pp. 955–964.10.1016/j.cep.2003.09.001Search in Google Scholar

[55] Cheng, W. P. Hydrolytic characteristics of polyferric sulfate and its application in surface water treatment. Separation Science and Technology, Vol. 36, No. 10, 2001, pp. 2265–2277.10.1081/SS-100105917Search in Google Scholar

[56] Tetteh, E. K. and S. Rathilal. Evaluation of different polymeric coagulants for the treatment of oil refinery wastewater.” Cogent Engineering, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2020, id. 1785756.10.1080/23311916.2020.1785756Search in Google Scholar

[57] Shen, J., H. Zhao, H. Cao, Y. Zhang, and Y. Chen. Removal of total cyanide in coking wastewater during a coagulation process: Significance of organic polymers. Journal of Environmental Science (China), Vol. 26, No. 2, 2014, pp. 231–239.10.1016/S1001-0742(13)60512-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[58] Wei, Y., X. Dong, A. Ding, and D. Xie. Characterization and coagulation-flocculation behavior of an inorganic polymer coagulant - poly-ferric-zinc-sulfate. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers, Vol. 58, 2016, pp. 351–356.10.1016/j.jtice.2015.06.004Search in Google Scholar

[59] Zhu, G., H. Zheng, Z. Zhang, T. Tshukudu, P. Zhang, and X. Xiang. Characterization and coagulation-flocculation behavior of polymeric aluminum ferric sulfate (PAFS). Chemical Engineering Journal, Vol. 178, 2011, pp. 50–59.10.1016/j.cej.2011.10.008Search in Google Scholar

[60] Moussas, P. A. and A. I. Zouboulis. Synthesis, characterization and coagulation behavior of a composite coagulation reagent by the combination of polyferric sulfate (PFS) and cationic polyelectrolyte. Separation and Purification Technology, Vol. 96, 2012, pp. 263–273.10.1016/j.seppur.2012.06.024Search in Google Scholar

[61] Zhan, W., Y. Tian, J. Zhang, W. Zuo, L. Li, Y. Jin, et al. Mechanistic insights into the roles of ferric chloride on methane production in anaerobic digestion of waste activated sludge. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 296, 2021, id. 126527.10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126527Search in Google Scholar

[62] Wu, B., J. Li, Y. Gan, H. Zhihao, H. Li, and S. Zhang. Titanium xerogel as a potential alternative for polymeric ferric sulfate in coagulation removal of antimony from reverse osmosis concentrate. Separation and Purification Technology, Vol. 291, 2022, id. 120863.10.1016/j.seppur.2022.120863Search in Google Scholar

[63] Sun, Q., Y. Li, T. Tang, Z. Yuan, and C. P. Yu. Removal of silver nanoparticles by coagulation processes. Journal of Hazardous Materials, Vol. 261, 2013, pp. 414–420.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.07.066Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[64] Ma, J., Z. Wang, Y. Xu, Q. Wang, Z. Wu, and A. Grasmick. Organic matter recovery from municipal wastewater by using dynamic membrane separation process. Chemical Engineering Journals, Vol. 219, 2013, pp. 190–199.10.1016/j.cej.2012.12.085Search in Google Scholar

[65] Zhang, G., T. T. Zhou, L. Zhang, J. Wang, Z. Chi, and E. Hu. Improving acoustic agglomeration efficiency of coal-fired fly-ash particles by addition of liquid binders. Chemical Engineering Journal, Vol. 334, 2018, pp. 891–899.10.1016/j.cej.2017.10.126Search in Google Scholar

[66] Chen, G. Q., Y. H. Wu, Y. J. Tan, Z. Chen, X. Tong, Y. Bai, et al. Pretreatment for alleviation of RO membrane fouling in dyeing wastewater reclamation. Chemosphere, Vol. 292, 2022, id. 133471.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.133471Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[67] Zhang, M., Z. Cai, L. Xie, Y. Zhang, L. Tang, Q. Zhou, et al. Comparison of coagulative colloidal microbubbles with monomeric and polymeric inorganic coagulants for tertiary treatment of distillery wastewater. Science of the Total Environment, Vol. 694, 2019, id. 133649.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.133649Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[68] Liu, Y., Z. Lou, K. Yang, Z. Wang, C. Zhou, Y. Li, et al. Coagulation removal of Sb(V) from textile wastewater matrix with enhanced strategy: Comparison study and mechanism analysis. Chemosphere, Vol. 237, 2019, id. 124494.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124494Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[69] Ruihua, L., Z. Lin, T. Tao, and L. Bo. Phosphorus removal performance of acid mine drainage from wastewater. Journal of Hazardous Materials, Vol. 190, No. 1–3, 2011, pp. 669–676.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.03.097Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[70] Li, B., W. Ma, H. Wang, F. Zeng, C. Deng, and H. Fan. Optimization study on polymeric ferric sulfate (PFS) phosphorous depth removal. Applied Mechanics and Materials, Vol. 71–78, 2011, pp. 3219–3223.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.71-78.3219Search in Google Scholar

[71] Cui, J., C. Jing, D. Che, J. Zhang, and S. Duan. Groundwater arsenic removal by coagulation using ferric(III) sulfate and polyferric sulfate: A comparative and mechanistic study. Journal of Environmental Science (China), Vol. 32, No. Iii, 2015, pp. 42–53.10.1016/j.jes.2014.10.020Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[72] Dodbiba, G., T. Nukaya, Y. Kamioka, Y. Tanimura, and T. Fujita. Removal of arsenic from wastewater using iron compound: Comparing two different types of adsorbents in the context of LCA. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, Vol. 5312, 2009, pp. 688–697.10.1016/j.resconrec.2009.05.002Search in Google Scholar

[73] Katsoyiannis I. A., N. M Tzollas, M. Tolkou, M. Mitrakas, and A. I. Zouboulis. Use of novel composite coagulants for arsenic removal from waters - experimental insight for the application of polyferric sulfate (PFS). Sustainability, Vol. 9, No. 4, 2017, id. 590.10.3390/su9040590Search in Google Scholar

[74] Xu, M., Y. Luo, X. Wang, and L. Zhou. Coagulation-ultrafiltration efficiency of polymeric Al-, Fe-, and Ti- coagulant with or without polyacrylamide composition. Separation and Purification Technology, Vol. 280, September 2021, 2022, pp. 1–10.10.1016/j.seppur.2021.119957Search in Google Scholar

[75] Hao, X., J. Tang, X. Yi, K. Gao, Q. Yao, C. Feng, et al. Extracellular polymeric substance induces biogenesis of vivianite under inorganic phosphate-free conditions. Journal of Environmental Science (China), Vol. 120, 2022, pp. 115–124.10.1016/j.jes.2021.08.043Search in Google Scholar

[76] Yue, X., Y. Yang, X. Li, J. Ren, Z. Zhou, Y. Zhang, et al. Effect of Fe-based micro-flocculation combined with gravity-driven membrane ultrafiltration on removal of aluminum species during water treatment. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, Vol. 9, No. 6, 2021, pp. 1–9.10.1016/j.jece.2021.106803Search in Google Scholar

[77] de Sena, R. F., P. M. Moreira, and H. J. José. Comparison of coagulants and coagulation aids for treatment of meat processing wastewater by column flotation. Bioresource Technology, Vol. 9917, 2008, pp. 8221–8225.10.1016/j.biortech.2008.03.014Search in Google Scholar

[78] Osweiler, S. H., M. Fan, S. W. Sung, R. C. Brown, S. Lebepe-Mazur, and G. Ronald Myers. Toxicity evaluation of polymeric ferric sulphate. International Journal of Environmental Technology and Management, Vol. 1, No. 4, 2001, pp. 464–471.10.1504/IJETM.2001.000775Search in Google Scholar

[79] Jiang, J. Q. and N. J. D. Graham. Preparation and characterisation of an optimal polyferric sulphate (PFS) as a coagulant for water treatment. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology, Vol. 73, No. 4, 1998, pp. 351–358.10.1002/(SICI)1097-4660(199812)73:4<351::AID-JCTB964>3.0.CO;2-SSearch in Google Scholar

[80] Zouboulis, A. I. and P. A. Moussas. Polyferric silicate sulphate (PFSiS): Preparation, characterisation and coagulation behaviour. Desalination, Vol. 224, No. 1–3, 2008, pp. 307–316.10.1016/j.desal.2007.06.012Search in Google Scholar

[81] Meng, X., S. A. Khoso, J. Kang, J. Wu, J. Gao, S. Lin, et al. A novel scheme for flotation tailings pulp settlement and chemical oxygen demand reduction with polyferric sulfate. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 241, 2019, 118371.10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118371Search in Google Scholar

[82] Li, C., X. Yi, Z. Dang, H. Yu, T. Zeng, C. Wei, et al. Fate of Fe and Cd upon microbial reduction of Cd-loaded polyferric flocs by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Chemosphere, Vol. 144, 2016, pp. 2065–2072.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.10.095Search in Google Scholar

[83] Tianzhi, W., W. Weijie, H. Hongying, and S. T. Khu. Effect of coagulation on bio-treatment of textile wastewater: Quantitative evaluation and application. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 312, May, 2021, id. 127798.10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127798Search in Google Scholar

[84] Zhao, Y., X. Li, L. Li, and A. Li. The solubility of polyferric sulfate. Journal Environmental Science, Vol. 2211, 2010, pp. 1749–1754.Search in Google Scholar

[85] Zhang, J., Z. Wang, J. Zheng, X. Zhang, and J. Qu. Effects of phosphate and natural organic matter on the solubility and aggregation of polyferric sulfate. Journal of Colloid Interface Science, Vol. 406, 2013, pp. 72–77.Search in Google Scholar

[86] Wang, D., C. Li, and L. Zhang. Formation of Fe(OH)3 precipitates from the hydrolysis of polyferric sulfate and its effect on coagulation performance. Journal of Water Process Engineering, Vol. 25, 2018, pp. 141–146.Search in Google Scholar

[87] Saxena, K., U. Brighu, and A. Choudhary. Parameters affecting enhanced coagulation: a review. Environmental Technology Reviews, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2018, pp. 156–176.10.1080/21622515.2018.1478456Search in Google Scholar

[88] Turhan, K. and Z. Turgut. Decolorization of direct dye in textile wastewater by ozonization in a semi-batch bubble column reactor. Desalination, Vol. 242, No. 1–3, 2009, pp. 256–263.10.1016/j.desal.2008.05.005Search in Google Scholar

[89] Sahu, O. and P. Chaudhari. Review on chemical treatment of industrial waste water. Journal of Applied Sciences and Environmental Management, Vol. 17, No. 2, 2013, pp. 241–257.10.4314/jasem.v17i2.8Search in Google Scholar

[90] Zhang, X., L. Zhang, Y. Liu, and X. Wang. Characterization of dissolved organic matter removal from a natural water source by polyferric sulfate coagulation: Coagulation behavior and mechanisms. Journal of Environmental Management, Vol. 222, 2018, pp. 122–128.Search in Google Scholar

[91] Huang, Y., Q. Chen, Z. Wang, H. Yan, C. Chen, D. Yan, et al. Abatement technology of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) by means of enhanced coagulation and ozonation for wastewater reuse. Chemosphere, Vol. 285, July, 2021.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131515Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[92] Jiang, J. Q., N. J. D. Graham, and C. Harward. Coagulation of upland coloured water with polyferric sulphate compared to conventional coagulants. Journal of Water Supply: Research and Technology - AQUA, Vol. 45, No. 3, 1996, pp. 143–154.Search in Google Scholar

[93] Li, H. S., S. Q. Zhou, Y. B. Sun, and P. Feng. Advanced treatment of landfill leachate by a new combination process in a full-scale plant. Journal of Hazardous Material, Vol. 172, No. 1, 2009, pp. 408–415.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.07.034Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[94] Liu, X., X. M. Li, Q. Yang, X. Yue, T. T. Shen, W. Zheng, et al. Landfill leachate pretreatment by coagulation-flocculation process using iron-based coagulants: Optimization by response surface methodology. Chemical Engineering Journal, Vol. 200–202, 2012, pp. 39–51.10.1016/j.cej.2012.06.012Search in Google Scholar

[95] Wang, H. T., Y. Y. Ye, J. Qi, F. T. Li, and Y. L. Tang. Removal of titanium dioxide nanoparticles by coagulation: Effects of coagulants, typical ions, alkalinity and natural organic matters. Water Science and Technology, Vol. 68, No. 5, 2013, pp. 1137–1143.10.2166/wst.2013.356Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[96] Xing, Y., S. Chen, B. Wu, X. Song, and Z. Jin. Multi-objective optimized pre-collection of sewage resources by sustainable enhanced coagulation process. Journal of Water Process Engineering, Vol. 47, 2022, id. 102701.10.1016/j.jwpe.2022.102701Search in Google Scholar

[97] Yang, Z., Y. Shang, Y. Lu, Y. Chen, X. Huang, A. Chen, et al. Flocculation properties of biodegradable amphoteric chitosan-based flocculants. Chemical Engineering Journal, Vol. 172, No. 1, 2011, pp. 287–295.10.1016/j.cej.2011.05.106Search in Google Scholar

[98] Zhao, Y. X. and X. Y. Li. Polymerized titanium salts for municipal wastewater preliminary treatment followed by further purification via crossflow filtration for water reuse. Separation and Purification Technology, Vol. 211, September 2018, 2019, pp. 207–217.10.1016/j.seppur.2018.09.078Search in Google Scholar

[99] Liang, Z., Y. Wang, Y. Zhou, H. Liu, and Z. Wu. Hydrolysis and coagulation behavior of polyferric sulfate and ferric sulfate. Water Science and Technology, Vol. 59, No. 6, 2009, pp. 1129–1135.10.2166/wst.2009.096Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[100] Wu, Z., D. Fang, Q. Cheng, W. Zhang, Q. Wang, J. Xie, et al. Preparation and performance characterization of solid polyferric sulfate (SPFS) water purifier from sintering dust. Materials Research Express, Vol. 6, No. 7, 2019, id. 75503.10.1088/2053-1591/ab1120Search in Google Scholar

[101] Maćczak, P., H. Kaczmarek, and M. Ziegler-Borowska. Recent achievements in polymer bio-based flocculants for water treatment. Materials, Vol. 13, No. 18, 2020, id. 3951.10.3390/ma13183951Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[102] Zhu, G., Y. Bian, A. S. Hursthouse, S. Xu, N. Xiong, and P. Wan. The role of magnetic MOFs nanoparticles in enhanced iron coagulation of aquatic dissolved organic matter. Chemosphere, Vol. 247, 2020, id. 125921.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.125921Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[103] Huang, X., Y. Wan, B. Shi, J. Shi, H. Chen, H. and Liang. Characterization and application of poly-ferric-titanium-silicate-sulfate in disperse and reactive dye wastewaters treatment. Chemosphere, Vol. 249, 2020, id. 126129.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126129Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[104] Chen, M., K. Oshita, Y. Mahzoun, M. Takaoka, S. Fukutani, and K. Shiota. Survey of elemental composition in dewatered sludge in Japan. Science of the Total Environment, Vol. 752, 2021, id. 141857.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141857Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[105] Moussas, P. A. and A. I. Zouboulis. A study on the properties and coagulation behaviour of modified inorganic polymeric coagulant-polyferric silicate sulphate (PFSiS). Separation and Purification Technology, Vol. 63, No. 2, 2008, pp. 475–483.10.1016/j.seppur.2008.06.009Search in Google Scholar

[106] Song, Z. and N. Ren. Properties and coagulation mechanisms of polyferric silicate sulfate with high concentration. Journal of Environmental Sciences, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2008, pp. 129–134.10.1016/S1001-0742(08)60020-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[107] Zhang, X., X. Zhang, Y. Liu, Q. Zhang, S. Yang, and X. He. Removal of viscous and clogging suspended solids in the wastewater from acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene resin production by a new dissolved air release device. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, Vol. 148, 2021, pp. 524–535.10.1016/j.psep.2020.10.031Search in Google Scholar

[108] Li, S. and Y. Kang. Effect of PO43− on the polymerization of polyferric phosphatic sulfate and its flocculation characteristics for different simulated dye wastewater. Separation and Purification Technology, Vol. 276, July, 2021, id. 119373.10.1016/j.seppur.2021.119373Search in Google Scholar

[109] Huang, C. P., J. Y. Wu, and Y. J. Li. Treatment of spent nuclear fuel debris contaminated water in the Taiwan Research Reactor spent fuel pool. Progress in Nuclear Energy, Vol. 108, May, 2018, pp. 26–33.10.1016/j.pnucene.2018.05.006Search in Google Scholar

[110] Yang, N., H. Xiao, K. Pi, J. Fang, S. Liu, Y. Chen, et al. Synchronization of dehydration and phosphorous immobilization for river sediment by calcified polyferric sulfate pretreatment. Chemosphere, Vol. 269, 2021, pp. 1–10.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.129403Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[111] Hu, C., H. Liu, J. Qu, D. Wang, and J. Ru. Coagulation behavior of aluminum salts in eutrophic water: Significance of Al13 species and pH control. Environmental Science and Technology, Vol. 40, No. 1, 2006, pp. 325–331.10.1021/es051423+Search in Google Scholar

[112] Alazaiza, M. Y., A. Albahnasawi, G. A. Ali, M. J. Bashir, D. E. Nassani, T. Al Maskari, et al. Application of Natural Coagulants for Pharmaceutical Removal from Water and Wastewater: A Review. Water (Switzerland), Vol. 14, No. 2, 2022, pp. 1–16.10.3390/w14020140Search in Google Scholar

[113] Chu, Y. B., M. Li, J. W. Liu, W. Xu, S. H. Cheng, and H. Z. Zhao. Molecular insights into the mechanism and the efficiency-structure relationship of phosphorus removal by coagulation. Water Research, Vol. 147, 2018, pp. 195–203.10.1016/j.watres.2018.10.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[114] Yukselen, M. A. and J. Gregory. The effect of rapid mixing on the break-up and re-formation of flocs. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology, Vol. 79, No. 7, 2004, pp. 782–788.10.1002/jctb.1056Search in Google Scholar

[115] Al-Asheh, S. and A. Aidan. Operating Conditions of Coagulation-Flocculation Process for High Turbidity Ceramic Wastewater. Journal Water Environmental Nanotechnology, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2017, pp. 80–87.Search in Google Scholar

[116] Hossain, M. S., F. Omar, A. J. Asis, R. T. Bachmann, M. Z. Islam Sarker, and M. O. Ab Kadir. Effective treatment of palm oil mill effluent using FeSO4.7H2O waste from titanium oxide industry: Coagulation adsorption isotherm and kinetics studies. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 219, 2019, pp. 86–98.10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.069Search in Google Scholar

[117] Duan, J. and J. Gregory. Coagulation by hydrolysing metal salts. Advances in Colloid Interface Science, Vol. 100–102, 2003, pp. 475–502.10.1016/S0001-8686(02)00067-2Search in Google Scholar

[118] Zhao, C., J. Zhou, Y. Yan, L. Yang, G. Xing, H. Li, et al. Application of coagulation/flocculation in oily wastewater treatment: A review. Science of the Total Environment, Vol. 765, 2021, id. 142795.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142795Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[119] Zhao, Y. X., B. Y. Gao, H. K. Shon, B. C. Cao, and J. H. Kim. Coagulation characteristics of titanium (Ti) salt coagulant compared with aluminum (Al) and iron (Fe) salts. Journal of Hazardous Material, Vol. 185, No. 2–3, 2011, pp. 1536–1542.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.10.084Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[120] Jarvis, P., B. Jefferson, and S. A. Parsons. Breakage, regrowth, and fractal nature of natural organic matter flocs. Environmental Science and Technology, Vol. 39, No. 7, 2005, pp. 2307–2314.10.1021/es048854xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[121] Lin, L., R. H. Li, Z. Y. Yang, and X. Y. Li. Effect of coagulant on acidogenic fermentation of sludge from enhanced primary sedimentation for resource recovery: Comparison between FeCl3 and PACl. Chemical Engineering Journal, Vol. 325, 2017, pp. 681–689.10.1016/j.cej.2017.05.130Search in Google Scholar

[122] Zhou, G. J., L. Lin, X. Y. Li, and K. M. Leung. Removal of emerging contaminants from wastewater during chemically enhanced primary sedimentation and acidogenic sludge fermentation. Water Research, Vol. 175, 2020, id. 115646.10.1016/j.watres.2020.115646Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[123] WHO. Guidelines for drinking-water quality, 4th edn. World Health Organization, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[124] EPA. National primary drinking water regulations. Environmental Protection Agency, 2010[Online]Search in Google Scholar

[125] CPCB. Energy Conservation Guidelines for Water Supply and Wastewater Sector, Central Pollution Control Board, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[126] Chemsrc. Polyferric Sulfate, Chemsrc, 2023.Search in Google Scholar

[127] Loprest Water Treatment. “Polyferric Sulfate (PFS) Cost Comparison, Loprest Water Treatment, 2021.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Progress in preparation and ablation resistance of ultra-high-temperature ceramics modified C/C composites for extreme environment

- Solar lighting systems applied in photocatalysis to treat pollutants – A review

- Technological advances in three-dimensional skin tissue engineering

- Hybrid magnesium matrix composites: A review of reinforcement philosophies, mechanical and tribological characteristics

- Application prospect of calcium peroxide nanoparticles in biomedical field

- Research progress on basalt fiber-based functionalized composites

- Evaluation of the properties and applications of FRP bars and anchors: A review

- A critical review on mechanical, durability, and microstructural properties of industrial by-product-based geopolymer composites

- Multifunctional engineered cementitious composites modified with nanomaterials and their applications: An overview

- Role of bioglass derivatives in tissue regeneration and repair: A review

- Research progress on properties of cement-based composites incorporating graphene oxide