Abstract

SiC foam ceramics are extensively used in numerous industrial applications that require high-temperature conditions. They can be used as thermal insulation, structural catalyst supports and energy storage materials. In this article, effective thermal conductivity of SiC foam ceramics at high temperature is studied by steady plane heat source method. This research aims to investigate the variations of effective thermal conductivity with pore density, stacking thickness, heat source temperature, and pore arrangement structure of foam ceramics. By a comparison of effective thermal conductivities of various pore density ceramic sheets, the experimental results show that the effective thermal conductivity of foam ceramics decreases with the increase of the pore density and stacking thickness. The effective thermal conductivity of the foam ceramics increases significantly when the heat source temperature is more than 200°C. For modular SiC foam ceramics, increasing the average pore density and sudden change of the pore density between ceramic sheets are not conducive to the increase of the effective thermal conductivity.

Nomenclature

- Λ

-

thermal conductivity, W (m °C)−1

- δ

-

thickness of material, m

- δ′

-

total thickness of material of the two-layer ceramic foam, m

- q

-

heat flux, W m−2

- t

-

material surface temperature, °C

- T

-

surface temperature of double-layer ceramic foam, °C

- R

-

thermal resistance of each layer of ceramic foam, °C W−1

Subscripts

- eff

-

effective

- h

-

hot surface

- c

-

cold surface

- lf

-

lower surface of the first layer of foam ceramics

- uf

-

upper surface of the first layer of foam ceramics

- ls

-

lower surface of the second layer of ceramic foam

- us

-

upper surface of the second layer of ceramic foam

- C

-

contact

1 Introduction

Foam ceramics are widely used in many engineering fields due to their large specific surface area, high heat transfer efficiency, and uniform mixing of fluids. The parameter, effective thermal conductivity, is a major concern in predicting the heat transfer efficiency of systems, such as porous media combustion system [1], heat exchangers [2], and solar collectors [3].

Many researchers have paid attention to heat transfer in SiC foam ceramics from different perspectives. Based on experimental tests [4], analytical analysis [5], and numerical simulations [6,7], researchers mostly focused on effects of temperature, pore parameters, and solid thermal conductivity on effective thermal conductivity of SiC foam ceramics. Nemoto et al. [8] investigated thermal conductivity of foam ceramics at low temperature. Results pointed out that the thermal conductivity of SiC foam ceramics increases gradually with the increase in temperature during a temperature rise from 4 to 300 K. Zhou et al. [9] investigated the effective thermal conductivity of foam ceramics at 800°C. Experimental results showed that foamed mullite-SiC ceramics have an excellent potential as thermal-insulating materials for cement kiln preheaters. Jiang et al. [10] reported the effect of SiC foam ceramic particle size on an effective thermal conductivity of form-stable NaNO3. It was found that form-stable NaNO3 (56.6%) that had a skeleton modified by 10% SiC foam ceramics with particle size of 50 nm possessed an effective thermal conductivity of 2.06 W (m K)−1 at 25°C, which was 265% higher than that of pure NaNO3. Qiu et al. [11] experimentally studied effects of specific surface area and pore size on thermal conductivity from mesoporous to macroporous SiC ceramics. Results showed that the thermal conductivity of both gas and solid phases increased with the pore size.

Pore structure directly affects the heat transfer performance of foam ceramics and plays a leading role in the control of temperature distribution under high temperature heat source [12]. Many researchers have studied the effect of porosity and pore density on the effective thermal conductivity of foam ceramics. Mendes et al. [13] experimentally investigated the effect of 10 pores per inch (PPI) foam ceramics porosity on the effective thermal conductivity by the transient surface heat source method. Their results showed that the effective thermal conductivity increased by 22% when porosity increased from 0.57 to 0.74 at 1,500 K. Dietrich et al. [14] reported that the effective thermal conductivity increased with the increase of porosity, and effective thermal conductivity of foam ceramics with low PPI number was higher than that with high PPI number. Kang et al. [15] added nano-sized SiO2 to a nano-sized SiC and nano-sized carbon template mixture to reduce porosity, resulting in an extremely low effective thermal conductivity in porous SiC–SiO2 foam ceramics reaching as low as 0.066 W (m K)−1. Liu and Zhao [16] numerically investigated the influence of geometric (e.g., pore size, pore type, and porosity) on effective thermal conductivity of porous structures with open and closed pores. They found that using nanoscale pores is an effective strategy to achieve an ultralow effective thermal conductivity for the highly porous structures with open and closed pores.

Most of earlier studies focused on measurements of the effective thermal conductivity with single homogeneous materials, especially at high temperature environment for test conditions. However, modular nonuniform foam ceramic composed of foam ceramic sheets with different pore densities are mostly used in porous media burners. Xie et al. [17] revealed that the use of high-porosity ceramic foam in combustion zone and low-porosity ceramic foam in preheating zone can achieve efficient combustion. Song et al. [18] conducted an experimental study on the premixed combustion of low calorific gas an axial and radial gradually varied porous media burner. They found that the gradually varied porous media burner can burn ultra-low calorific gas of 1.4 MJ m−3. Al-attab et al. [19] designed a two-layer porous medium combustion regenerative device for burning low heating value. Results showed that the maximum heat recovery heat exchanger effectiveness was about 93% with an overall system efficiency of 54%. The arrangement of pore structure affects combustion temperature by affecting heat flow transfer characteristics [20,21]. The effective thermal conductivity of modular nonuniform ceramic foam with different pore densities is probably not a simple superposition relationship. Moreover, there are very few studies on the effect of pore mutation and solid skeleton discontinuity on the effective thermal conductivity of foam ceramics. This research aims to investigate effective thermal conductivity of variable pore densities SiC foam ceramics formed by stacking heterogeneous or homogeneous porous media. Three nonuniform pore structures will be designed by superposition of porous media with different pore densities. Effects of heat source temperature, pore density, thickness of porous media, and pore arrangement structure on the effective thermal conductivity will be investigated using a steady plane heat source method. Results have a great significance to the research of high-temperature heat transfer in porous media with variable porosity. This study provides insight into the understanding of effective thermal conductivity of modular SiC foam ceramics and has reference value for the design of thermal insulation materials and energy storage materials.

2 Experimental system

2.1 Experimental setup and methods

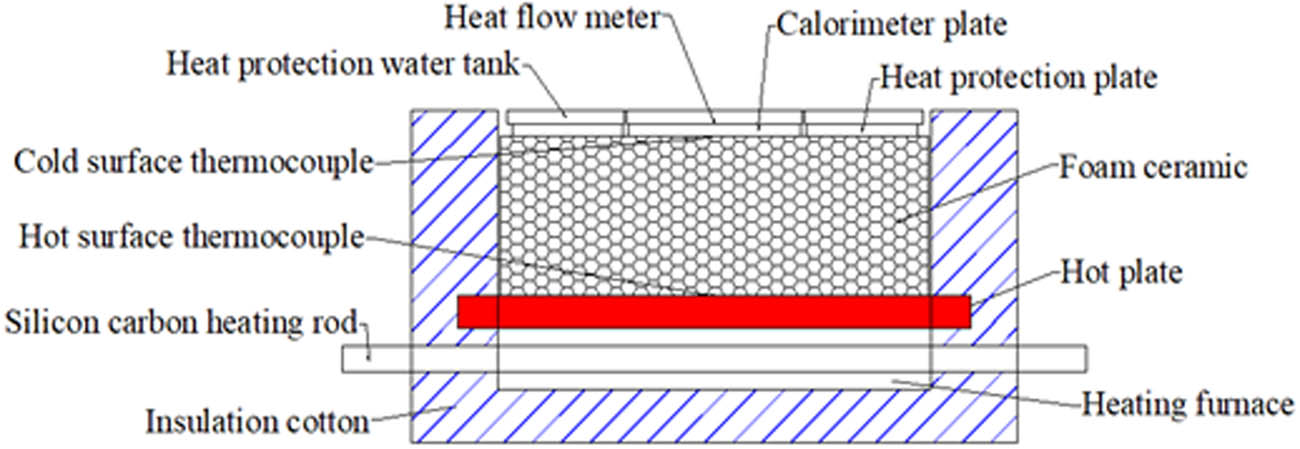

DRS-4A series effective thermal conductivity tester (produced by Xiangtan Instrument Co., Ltd.) was used to test the effective thermal conductivity of porous media in high temperature as shown in Figure 1. The tests are carried out in a heating furnace, which is wrapped with insulation cotton to prevent the heat loss. The effective thermal conductivity of foam ceramics is tested based on the steady plane heat source method. Figure 2 shows the schematic of the test principle. The tester consists of three main parts: a temperature control system, a measurement control system, and a data acquisition system. In the instrument heating furnace, silicon carbide rods are used for the heating. The temperature of the hot plate is controlled by a high-precision temperature controller by adjusting current and voltage. The cold plate is composed of a calorimeter plate and a heat protection plate. Four heat flow meters are installed in the calorimeter plate to detect heat flow through the sample. There is a semiconductor refrigeration plate in heat protection plate, which is used to keep the heat protection plate and the calorimeter plate in the same temperature. The constant temperature water tank provides a stable temperature as a reference temperature of the heat flow meter. The hot and cold surface temperatures of foam ceramics are measured by two K-type thermocouples. Thermocouples, heat flux meter and pressure sensor in the instrument, transmit the measured data to computer in real time.

Picture of high-temperature thermal conductivity tester.

Schematic of the test principle.

In this test, it is regarded as a pure heat conduction process. The thermal conductivity of the material is calculated according to Fourier’s law as follows:

where λ is the thermal conductivity (W (m °C)−1), q is the heat flux (W m−2), δ is the thickness of material (m), t h and t c represent the temperature values of hot and cold surfaces of the material (°C).

2.2 Tested materials

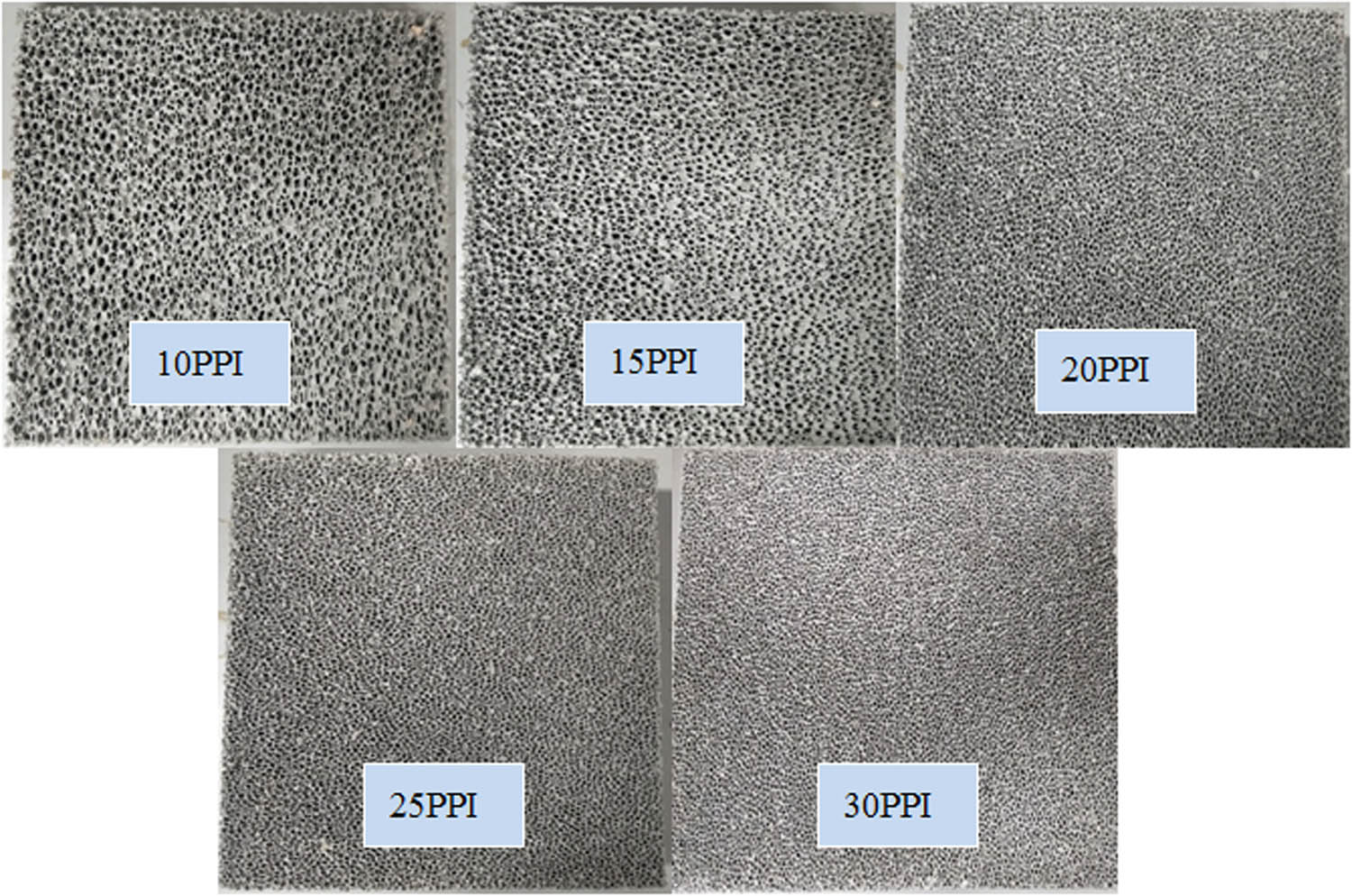

The tested section is SiC foam ceramic material with dimensions of 250 mm × 250 mm × 20 mm as shown in the Figure 3. The porosity is 0.85. Table 1 shows main performance indicators of SiC foam ceramics. With the material stacking thickness of 20–60 mm, and the pore density of 10–30 PPI, experiments are conducted under heat source temperature of 50–600°C.

Images of SiC foams.

Performance indicators of SiC ceramics foam

| Porous medium | SiC foam ceramics |

|---|---|

| Temperature range (°C) | <1,300 |

| Pore density (PPI) | 10–30 |

| Porosity | 0.85 |

| Bending strength (MPa/25°C) | 0.8 |

| Compressive strength (MPa/25°C) | 0.9 MPa/25°C |

| Thermal shock resistance | 6×/1,100°C |

2.3 Uncertainty analysis

The uncertainties of the experimental results are estimated based on an error analysis of present measurements. The measuring range of the thermal conductivity tester is 0.001–3 W (m °C)−1, and the measurement accuracy is better than 5%. K-type thermocouples are calibrated with an accuracy of 0.1°C, and the heat flow meter has an accuracy of 0.01 W m−2. The accuracy of the instrument to measure the thickness of the material is 0.1 mm.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Calibration test of equipment

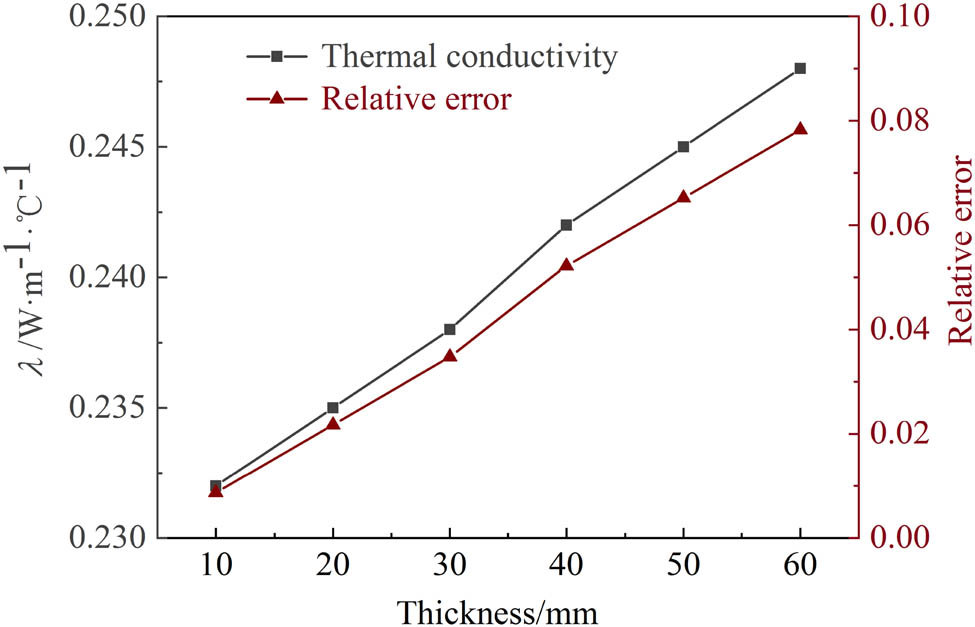

Neoprene is used to verify the test accuracy of equipment. The thermal conductivity of neoprene at 25°C is 0.23 W (m °C)−1. Figure 4 shows relative errors of the thermal conductivity of neoprene with different thicknesses at 25°C. It is found from the figure that the measured thermal conductivity and the relative error increase with the increase of neoprene thickness. This is mainly because the thermal conductivity increases with the increase of neoprene thickness under conditions of constant heat source temperature and heat flux. Increasing the thickness of neoprene makes the thermal insulation conditions more harsh, and errors of its thermal conductivity will be relatively increased. When the thickness is 60 mm, the relative error is still less than 8%, which proves the reliability of the test device.

Thermal conductivity and its relative error of neoprene with different thicknesses.

3.2 Determination of testing pressure

When multiple layers of ceramic foams are superimposed, pressure can directly affect the contact thermal resistance between the ceramic sheets, which cannot be ignored in the measurement of the effective thermal conductivity. The effective thermal conductivity varies with the pressure of two 10 PPI ceramic foam stack at 200°C as shown in Figure 5. It is found that the effective thermal conductivity increases by 2.89% from 0.4009 to 0.4125 W (m °C)−1 when the pressure increases from 50 to 100 N. Increasing the pressure makes the contact between the ceramic sheets more compact, which reduces the thermal contact resistance. The effective thermal conductivity increases. However, the deviation of the effective thermal conductivity is within 0.49%, and the deviation tends to be stable when the pressure increases from 100 to 250 N. Ceramic foam is made up of solid skeleton and pore part; hence, the compressive strength of foam ceramics is relatively small at high temperature. To ensure high measurement accuracy of the test, a smaller pressure should be selected for this test. Therefore, 100 N is selected as the pressure for all tests in this study.

Effective thermal conductivity under different pressures.

3.3 Effect of pore density of foam ceramics

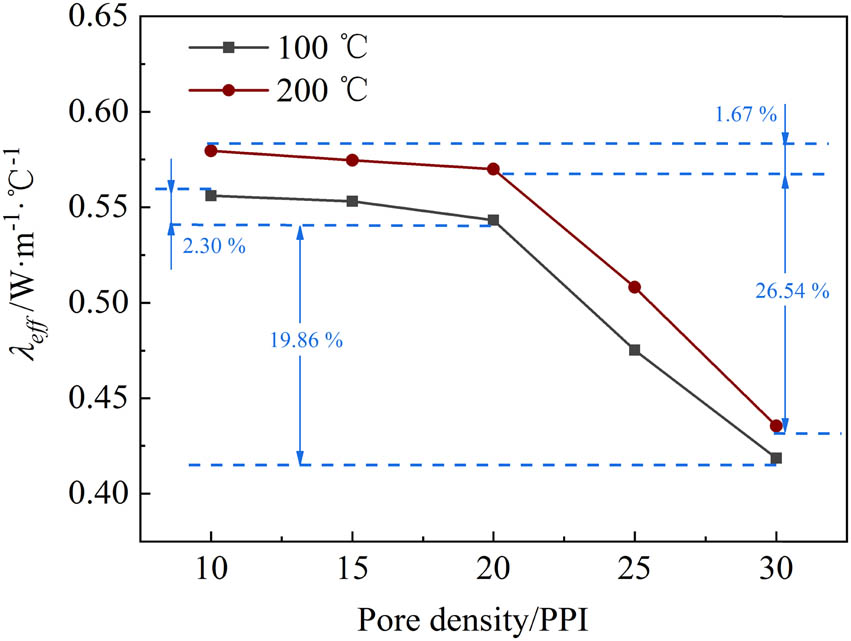

Figure 6 shows the effective thermal conductivity of a single layer ceramic foam under various pore densities, when the heat source temperatures are 100°C and 200°C. At different heat source temperatures, when the pore density increases from 10 to 20 PPI, the effective thermal conductivity decreases slightly in the range of 2.30%. However, the effective thermal conductivity decreases, obviously, when the pore density is higher than 20 PPI. The effective thermal conductivity decreases by 19.86 and 26.54% at 100°C and 200°C, respectively, when the pore density increases from 20 to 30 PPI. This result is mainly because the increase of the pore density of foam ceramics reduces the pore size, which weakens radiation heat transfer capability of foam ceramics. Moreover, the solid skeleton becomes thinner with the increase of the pore density, which leads to the decrease of thermal conductivity. The combined effect results in a reduction of the effective thermal conductivity. Figure 6 also shows that the effective thermal conductivity of foam ceramics with different pore densities slightly increases, when the heat source temperature increases from 100°C to 200°C. With the increase of the heat source temperature, the radiation heat of foam ceramics with the same pore density will increase, leading to an increase in the effective thermal conductivity.

Effect of pore density of foam ceramics on effective thermal conductivity.

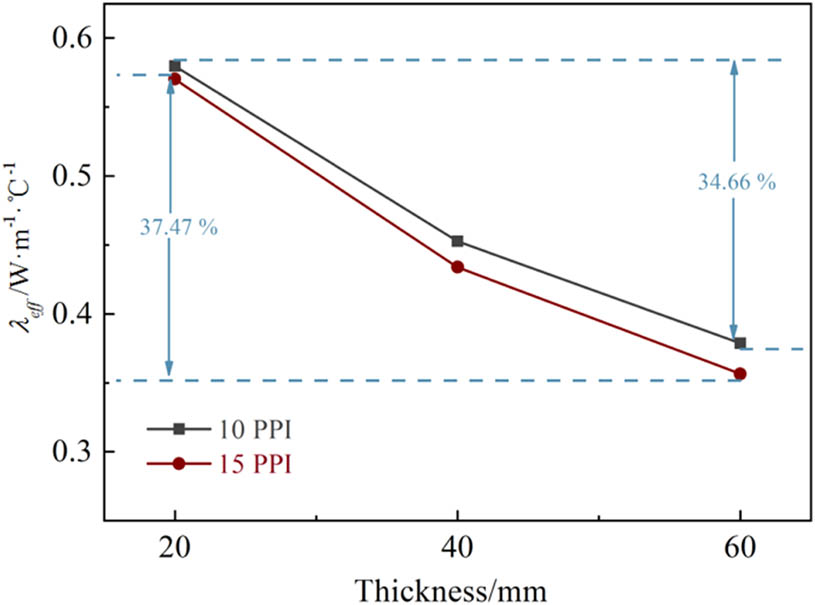

3.4 Effect of thickness of foam ceramic

Figure 7 shows effects of stacking thickness on the effective thermal conductivities of 10 and 15 PPI foam ceramics, when the heat source temperature is 200°C. Effective thermal conductivities of 10 and 15 PPI foam ceramics decrease by 34.66 and 37.47%, respectively, with the increase of stacking thickness from 20 to 60 mm. With the increase of foam ceramic thickness, the increase of thermal contact resistance between ceramic foams is the reason for the reduction of the effective thermal conductivity.

Effect of thickness of foam ceramic on effective thermal conductivity.

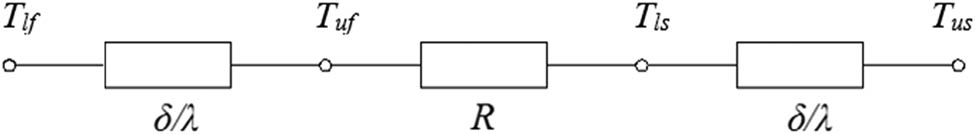

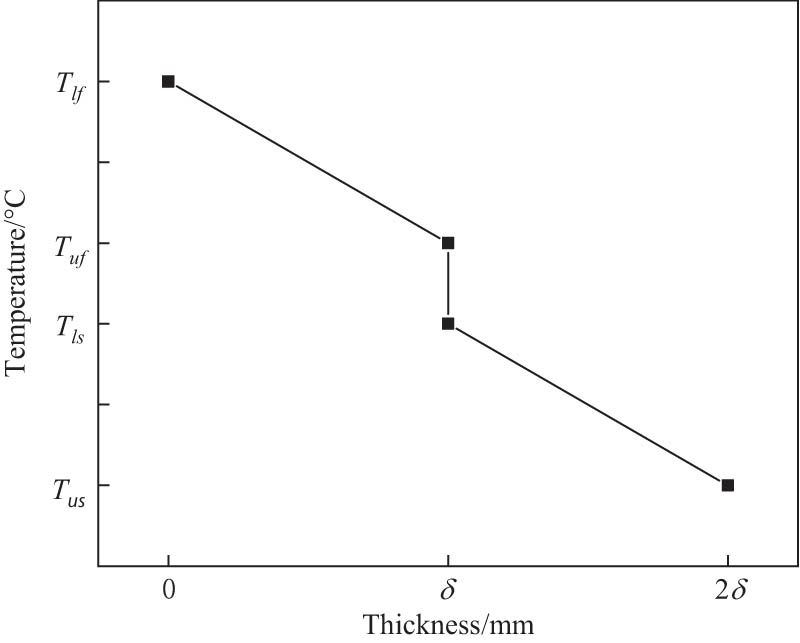

Figure 8 shows thermal resistance of two foam ceramic stacking during heat transfer. The lower surface temperature of the first layer of foam ceramics is represented by T lf, and the upper surface temperature is represented by T uf. The lower surface temperature of the second layer of ceramic foam is represented by T ls, and the upper surface temperature is represented by T us. R and δ are the thermal resistance and thickness of each layer of ceramic foam, respectively. In the process of series heat transfer with the same heat flux, the sum of the thermal resistance of each link is the total thermal resistance.

Analysis of thermal resistance during heat transfer.

Figure 9 shows the temperature changes with thickness when two layers of foam ceramics are superimposed. It is found that the temperature decreases with the increase of thickness. The continuous change of temperature appears fault when the thickness is δ. This is because there is a contact thermal resistance here. According to formula (2), the superposition of multilayer foam ceramics increases the contact thermal resistance, reducing the total effective thermal conductivity.

where

Relationship between temperature and thickness of each layer.

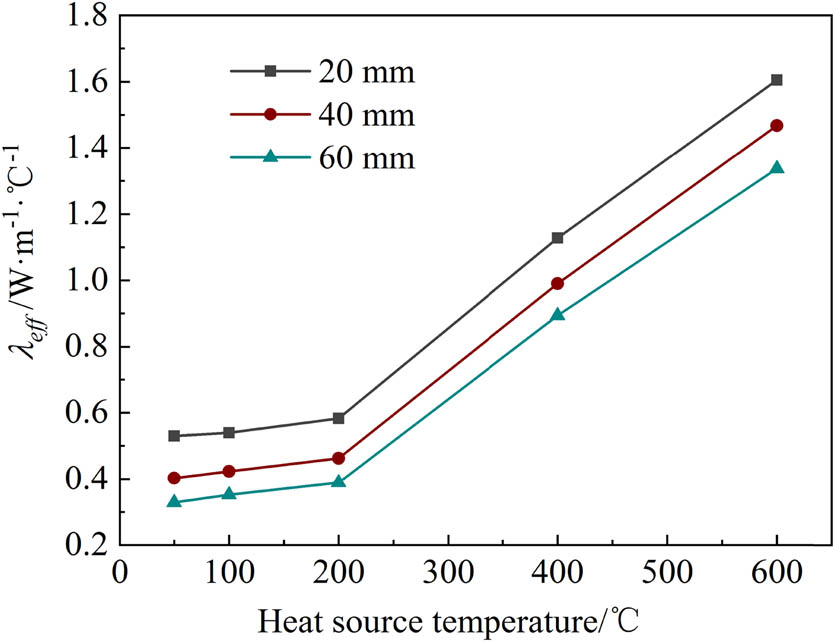

3.5 Effect of heat source temperature

For 10 PPI foam ceramics with different thicknesses, Figure 10 shows the effect of heat source temperature on the effective thermal conductivity. The effective thermal conductivity increases slowly when the heat source temperature is less than 200°C. It increases almost linearly when the temperature is more than 200°C. This is because under low temperature conditions, the heat transfer method of foam ceramics mainly depends on the heat conduction of solid skeleton. The radiant heat transfer under the heat source temperature of more than 200°C accounts for a certain proportion of heat transfer method of foam ceramics, which increases the overall effective thermal conductivity. It is found that the effective thermal conductivity decreases with the increase of stacking thickness of foam ceramic at the same heat source temperature. With the superposition of foam ceramic layers, the thermal contact resistance between layers increases, which leads to a reduction of the effective thermal conductivity.

Effect of heat source temperature on effective thermal conductivity.

3.6 Effect of pore structure

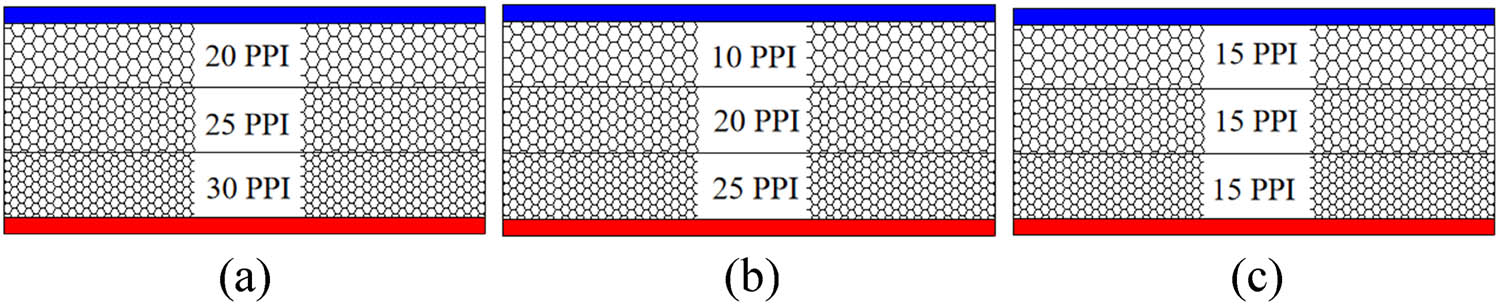

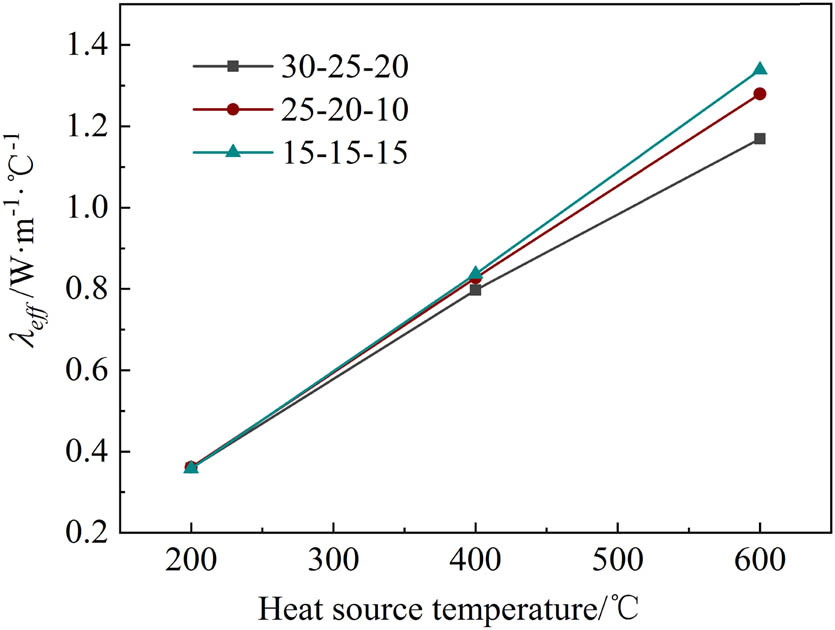

Figure 11 shows three pore structures with various pore densities from the hot surface to the cold surface, namely 30-25-20 (module type), 25-20-10 (module type), and 15-15-15 (uniform type). Figure 12 shows the effect of heat source temperature on the effective thermal conductivity of foam ceramics with different pore structures. With the increase of temperature, the radiant heat transfer capacity continues to increase. The effective thermal conductivity of foam ceramics increases with different pore structures. However, when the heat source temperature is lower than 400°C, the effective thermal conductivity of foam ceramics with different pore structures changes very little. This is because the main heat transfer method is heat conduction at lower temperature, and the radiation heat transfer has little effect on the overall effective thermal conductivity. The difference of effective thermal conductivity of three pore structures become significant when the heat source temperature increases to 400°C. The pore structure with the largest effective thermal conductivity at 600°C is 15-15-15 type, and that with the smallest effective thermal conductivity is 30-25-20 type. The pore density arrangement of the foam ceramic pore structure shows significant influence on this result. Among three structures, 30-25-20 type has the largest average pore density and the smallest average pore diameter, which hinders the radiation heat transfer of pore structure, so the effective thermal conductivity is the smallest. However, the average pore density of 15-15-15 type is the smallest, and the radiation heat transfer is the largest under the same conditions. Therefore, the effective thermal conductivity is the largest. Except the average pore density, sudden changes in the pore density between the foam ceramic sheets also affect the effective thermal conductivity of different pore structures. Compared with the uniform structure (15-15-15 type), there is a sudden change in the pore density between the foam ceramic sheets of modular structure (30-25-20 type and 25-20-10 type). The sudden change in pore density weakens the radiative heat transfer between the foamed ceramic sheets, resulting in a decrease in the effective thermal conductivity. These results indicate that a nonuniform porous medium with a larger average pore density has a smaller effective thermal conductivity. The sudden change of pore density between the foam ceramic sheets is also not conducive to the increase of the effective thermal conductivity. In the field of engineering applications, when SiC foam ceramics are used in thermal insulation materials, a strategy of increasing the average pore density of nonuniform porous media and the sudden change of pore density between ceramic sheets can be adopted. When SiC foam ceramics are used for heat exchangers and solar heat storage, the situation is reversed.

Schematic arrangement of three pore structures (a) 30-25-20 type, (b) 25-20-10 type, and (c) 15-15-15 type.

Effect of heat source temperature on effective thermal conductivity.

4 Conclusion

In this study, effects of pore density, stack thickness, and heat source temperature on the effective thermal conductivity of foam ceramics were investigated by a steady plane heat source method. Variations of the effective thermal conductivity of three variable pore structures were compared and analyzed. The main conclusions are shown as follows:

The effective thermal conductivity does not change significantly when the pore density of ceramic foam is less than 20 PPI. The effective thermal conductivity decreases by 26.54% when pore density of ceramic foam increases from 20 to 30 PPI. Increasing the stack thickness of foam ceramics is also not conducive to the increase of the effective thermal conductivity.

The effective thermal conductivity of foam ceramics with different stacking thickness increases slowly when heat source temperature is less than 200°C, whereas the effective thermal conductivity increases linearly when heat source temperature is more than 200°C.

For modular SiC foam ceramics, increasing the average pore density and sudden change of the pore density between ceramic sheets can reduce the effective thermal conductivity. The difference of the effective thermal conductivity of different variable pore structures increases significantly when the heat source temperature is more than 400°C.

-

Funding information: This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51806057) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (No. E2019202451).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Gao HB, Qu ZG, Feng XB, Tao WQ. Methane/air premixed combustion in a two-layer porous burner with different foam materials. Fuel. 2014;115:154–61.10.1016/j.fuel.2013.06.023Search in Google Scholar

[2] Zheng D, Yang J, Wang J, Kabelac S, Sundén B. Analyses of thermal performance and pressure drop in a plate heat exchanger filled with ferrofluids under a magnetic field. Fuel. 2021;293(1):120432.10.1016/j.fuel.2021.120432Search in Google Scholar

[3] Chen S, Li WH, Yan FW. Thermal performance analysis of a porous solar cavity receiver. Renew Energy. 2020;156:558–69.10.1016/j.renene.2020.04.077Search in Google Scholar

[4] Sans M, Schick V, Pr GP, Farges O. Experimental characterization of the coupled conductive and radiative heat transfer in ceramic foams with a flash method at high temperature. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2020;148:119077.10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2019.119077Search in Google Scholar

[5] Zimmerman RW. Thermal conductivity of fluid-saturated rocks. J Pet Sci Eng. 1989;3(3):219–7.10.1016/0920-4105(89)90019-3Search in Google Scholar

[6] Moumen AE, Kanit T, Imad A, Minor HE. Computational thermal conductivity in porous materials using homogenization techniques: numerical and statistical approaches. Comput Mater Sci. 2015;97:148–58.10.1016/j.commatsci.2014.09.043Search in Google Scholar

[7] Bourih K, Kaddouri W, Kanit T, Djebara Y, Imad A. Modelling of void shape effect on effective thermal conductivity of lotus-type porous materials. Mech Mater. 2020;151:103626.10.1016/j.mechmat.2020.103626Search in Google Scholar

[8] Nemoto T, Sasaki S, Hakuraku Y. Thermal conductivity of alumina and silicon carbide ceramics at low temperatures. Cryogenics. 1985;25(8):531–2.10.1016/0011-2275(85)90080-3Search in Google Scholar

[9] Zhou WZ, Yan W, Li N, Li YB, Dai Y, Lin YD, et al. Fabrication, characterization and thermal-insulation modeling of foamed mullite-SiC ceramics. J Alloy Compd. 2020;829:154523.10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.154523Search in Google Scholar

[10] Jiang F, Ling X, Zhang LL, Cang DQ, Ding YL. Improved thermal conductivity of form-stable NaNO3: using the skeleton of porous ceramic modified by SiC. Sol Energy Mater Sol Cell. 2021;231:111310.10.1016/j.solmat.2021.111310Search in Google Scholar

[11] Qiu L, Du YB, Bai YY, Feng YH, Zhang XX, Wu J, et al. Experimental characterization and model verification of thermal conductivity from mesoporous to macroporous SiOC ceramics. J Therm Sci. 2021;30(2):465–76.10.1007/s11630-021-1422-7Search in Google Scholar

[12] Dyga R, Witczak S. Investigation of effective thermal conductivity aluminum foams. Procedia Eng. 2012;42:1088–99.10.1016/j.proeng.2012.07.500Search in Google Scholar

[13] Mendes MAA, Talukdar P, Ray S, Trimis D. Detailed and simplified models for evaluation of effective thermal conductivity of open-cell porous foams at high temperatures in presence of thermal radiation. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2014;68:612–24.10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2013.09.071Search in Google Scholar

[14] Dietrich B, Fischedick T, Wallenstein M, Kind M. Thermal conductivity of ceramic sponges at temperatures up to 1000°C. Spec Top Rev Porous Media. 2015;6(2):133–43.10.1615/IHTC15.pmd.008405Search in Google Scholar

[15] Kang ES, Kim YW, Nam WH. Multiple thermal resistance induced extremely low thermal conductivity in porous SiC-SiO2 ceramics with hierarchical porosity. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2021;41:1171–80.10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2020.10.004Search in Google Scholar

[16] Liu H, Zhao XP. Thermal conductivity analysis of high porosity structures with open and closed pores. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2022;183:122089.10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2021.122089Search in Google Scholar

[17] Xie MZ, Shi JR, Deng YB, Liu H. Experimental and numerical investigation on performance of a porous medium burner with reciprocating flow. Fuel. 2009;88(1):206–13.10.1016/j.fuel.2008.07.020Search in Google Scholar

[18] Song FQ, Wen Z, Dong ZY, Wang EY, Liu X. Ultra-low calorific gas combustion in a gradually-varied porous burner with annular heat recirculation. Energy. 2017;119:497–503.10.1016/j.energy.2016.12.077Search in Google Scholar

[19] Al-attab KA, Ho JC, Zainal ZA. Experimental investigation of submerged flame in packed bed porous media burner fueled by low heating value producer gas. Exp Therm Fluid Sci. 2015;62:1–8.10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2014.11.007Search in Google Scholar

[20] Mohammadi I, Ajam H. Theoretical study on optimization of porous media burner by the improvement of coefficients of porosity variation equations. Int J Therm Sci. 2020;153:106386.10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2020.106386Search in Google Scholar

[21] Devi S, Sahoo N, Muthukumar P. Experimental studies on biogas combustion in a novel double layer inert Porous Radiant Burner. Renew Energy. 2020;149:1040–52.10.1016/j.renene.2019.10.092Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Enyu Wang et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Test influence of screen thickness on double-N six-light-screen sky screen target

- Analysis on the speed properties of the shock wave in light curtain

- Abundant accurate analytical and semi-analytical solutions of the positive Gardner–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili equation

- Measured distribution of cloud chamber tracks from radioactive decay: A new empirical approach to investigating the quantum measurement problem

- Nuclear radiation detection based on the convolutional neural network under public surveillance scenarios

- Effect of process parameters on density and mechanical behaviour of a selective laser melted 17-4PH stainless steel alloy

- Performance evaluation of self-mixing interferometer with the ceramic type piezoelectric accelerometers

- Effect of geometry error on the non-Newtonian flow in the ceramic microchannel molded by SLA

- Numerical investigation of ozone decomposition by self-excited oscillation cavitation jet

- Modeling electrostatic potential in FDSOI MOSFETS: An approach based on homotopy perturbations

- Modeling analysis of microenvironment of 3D cell mechanics based on machine vision

- Numerical solution for two-dimensional partial differential equations using SM’s method

- Multiple velocity composition in the standard synchronization

- Electroosmotic flow for Eyring fluid with Navier slip boundary condition under high zeta potential in a parallel microchannel

- Soliton solutions of Calogero–Degasperis–Fokas dynamical equation via modified mathematical methods

- Performance evaluation of a high-performance offshore cementing wastes accelerating agent

- Sapphire irradiation by phosphorus as an approach to improve its optical properties

- A physical model for calculating cementing quality based on the XGboost algorithm

- Experimental investigation and numerical analysis of stress concentration distribution at the typical slots for stiffeners

- An analytical model for solute transport from blood to tissue

- Finite-size effects in one-dimensional Bose–Einstein condensation of photons

- Drying kinetics of Pleurotus eryngii slices during hot air drying

- Computer-aided measurement technology for Cu2ZnSnS4 thin-film solar cell characteristics

- QCD phase diagram in a finite volume in the PNJL model

- Study on abundant analytical solutions of the new coupled Konno–Oono equation in the magnetic field

- Experimental analysis of a laser beam propagating in angular turbulence

- Numerical investigation of heat transfer in the nanofluids under the impact of length and radius of carbon nanotubes

- Multiple rogue wave solutions of a generalized (3+1)-dimensional variable-coefficient Kadomtsev--Petviashvili equation

- Optical properties and thermal stability of the H+-implanted Dy3+/Tm3+-codoped GeS2–Ga2S3–PbI2 chalcohalide glass waveguide

- Nonlinear dynamics for different nonautonomous wave structure solutions

- Numerical analysis of bioconvection-MHD flow of Williamson nanofluid with gyrotactic microbes and thermal radiation: New iterative method

- Modeling extreme value data with an upside down bathtub-shaped failure rate model

- Abundant optical soliton structures to the Fokas system arising in monomode optical fibers

- Analysis of the partially ionized kerosene oil-based ternary nanofluid flow over a convectively heated rotating surface

- Multiple-scale analysis of the parametric-driven sine-Gordon equation with phase shifts

- Magnetofluid unsteady electroosmotic flow of Jeffrey fluid at high zeta potential in parallel microchannels

- Effect of plasma-activated water on microbial quality and physicochemical properties of fresh beef

- The finite element modeling of the impacting process of hard particles on pump components

- Analysis of respiratory mechanics models with different kernels

- Extended warranty decision model of failure dependence wind turbine system based on cost-effectiveness analysis

- Breather wave and double-periodic soliton solutions for a (2+1)-dimensional generalized Hirota–Satsuma–Ito equation

- First-principle calculation of electronic structure and optical properties of (P, Ga, P–Ga) doped graphene

- Numerical simulation of nanofluid flow between two parallel disks using 3-stage Lobatto III-A formula

- Optimization method for detection a flying bullet

- Angle error control model of laser profilometer contact measurement

- Numerical study on flue gas–liquid flow with side-entering mixing

- Travelling waves solutions of the KP equation in weakly dispersive media

- Characterization of damage morphology of structural SiO2 film induced by nanosecond pulsed laser

- A study of generalized hypergeometric Matrix functions via two-parameter Mittag–Leffler matrix function

- Study of the length and influencing factors of air plasma ignition time

- Analysis of parametric effects in the wave profile of the variant Boussinesq equation through two analytical approaches

- The nonlinear vibration and dispersive wave systems with extended homoclinic breather wave solutions

- Generalized notion of integral inequalities of variables

- The seasonal variation in the polarization (Ex/Ey) of the characteristic wave in ionosphere plasma

- Impact of COVID 19 on the demand for an inventory model under preservation technology and advance payment facility

- Approximate solution of linear integral equations by Taylor ordering method: Applied mathematical approach

- Exploring the new optical solitons to the time-fractional integrable generalized (2+1)-dimensional nonlinear Schrödinger system via three different methods

- Irreversibility analysis in time-dependent Darcy–Forchheimer flow of viscous fluid with diffusion-thermo and thermo-diffusion effects

- Double diffusion in a combined cavity occupied by a nanofluid and heterogeneous porous media

- NTIM solution of the fractional order parabolic partial differential equations

- Jointly Rayleigh lifetime products in the presence of competing risks model

- Abundant exact solutions of higher-order dispersion variable coefficient KdV equation

- Laser cutting tobacco slice experiment: Effects of cutting power and cutting speed

- Performance evaluation of common-aperture visible and long-wave infrared imaging system based on a comprehensive resolution

- Diesel engine small-sample transfer learning fault diagnosis algorithm based on STFT time–frequency image and hyperparameter autonomous optimization deep convolutional network improved by PSO–GWO–BPNN surrogate model

- Analyses of electrokinetic energy conversion for periodic electromagnetohydrodynamic (EMHD) nanofluid through the rectangular microchannel under the Hall effects

- Propagation properties of cosh-Airy beams in an inhomogeneous medium with Gaussian PT-symmetric potentials

- Dynamics investigation on a Kadomtsev–Petviashvili equation with variable coefficients

- Study on fine characterization and reconstruction modeling of porous media based on spatially-resolved nuclear magnetic resonance technology

- Optimal block replacement policy for two-dimensional products considering imperfect maintenance with improved Salp swarm algorithm

- A hybrid forecasting model based on the group method of data handling and wavelet decomposition for monthly rivers streamflow data sets

- Hybrid pencil beam model based on photon characteristic line algorithm for lung radiotherapy in small fields

- Surface waves on a coated incompressible elastic half-space

- Radiation dose measurement on bone scintigraphy and planning clinical management

- Lie symmetry analysis for generalized short pulse equation

- Spectroscopic characteristics and dissociation of nitrogen trifluoride under external electric fields: Theoretical study

- Cross electromagnetic nanofluid flow examination with infinite shear rate viscosity and melting heat through Skan-Falkner wedge

- Convection heat–mass transfer of generalized Maxwell fluid with radiation effect, exponential heating, and chemical reaction using fractional Caputo–Fabrizio derivatives

- Weak nonlinear analysis of nanofluid convection with g-jitter using the Ginzburg--Landau model

- Strip waveguides in Yb3+-doped silicate glass formed by combination of He+ ion implantation and precise ultrashort pulse laser ablation

- Best selected forecasting models for COVID-19 pandemic

- Research on attenuation motion test at oblique incidence based on double-N six-light-screen system

- Review Articles

- Progress in epitaxial growth of stanene

- Review and validation of photovoltaic solar simulation tools/software based on case study

- Brief Report

- The Debye–Scherrer technique – rapid detection for applications

- Rapid Communication

- Radial oscillations of an electron in a Coulomb attracting field

- Special Issue on Novel Numerical and Analytical Techniques for Fractional Nonlinear Schrodinger Type - Part II

- The exact solutions of the stochastic fractional-space Allen–Cahn equation

- Propagation of some new traveling wave patterns of the double dispersive equation

- A new modified technique to study the dynamics of fractional hyperbolic-telegraph equations

- An orthotropic thermo-viscoelastic infinite medium with a cylindrical cavity of temperature dependent properties via MGT thermoelasticity

- Modeling of hepatitis B epidemic model with fractional operator

- Special Issue on Transport phenomena and thermal analysis in micro/nano-scale structure surfaces - Part III

- Investigation of effective thermal conductivity of SiC foam ceramics with various pore densities

- Nonlocal magneto-thermoelastic infinite half-space due to a periodically varying heat flow under Caputo–Fabrizio fractional derivative heat equation

- The flow and heat transfer characteristics of DPF porous media with different structures based on LBM

- Homotopy analysis method with application to thin-film flow of couple stress fluid through a vertical cylinder

- Special Issue on Advanced Topics on the Modelling and Assessment of Complicated Physical Phenomena - Part II

- Asymptotic analysis of hepatitis B epidemic model using Caputo Fabrizio fractional operator

- Influence of chemical reaction on MHD Newtonian fluid flow on vertical plate in porous medium in conjunction with thermal radiation

- Structure of analytical ion-acoustic solitary wave solutions for the dynamical system of nonlinear wave propagation

- Evaluation of ESBL resistance dynamics in Escherichia coli isolates by mathematical modeling

- On theoretical analysis of nonlinear fractional order partial Benney equations under nonsingular kernel

- The solutions of nonlinear fractional partial differential equations by using a novel technique

- Modelling and graphing the Wi-Fi wave field using the shape function

- Generalized invexity and duality in multiobjective variational problems involving non-singular fractional derivative

- Impact of the convergent geometric profile on boundary layer separation in the supersonic over-expanded nozzle

- Variable stepsize construction of a two-step optimized hybrid block method with relative stability

- Thermal transport with nanoparticles of fractional Oldroyd-B fluid under the effects of magnetic field, radiations, and viscous dissipation: Entropy generation; via finite difference method

- Special Issue on Advanced Energy Materials - Part I

- Voltage regulation and power-saving method of asynchronous motor based on fuzzy control theory

- The structure design of mobile charging piles

- Analysis and modeling of pitaya slices in a heat pump drying system

- Design of pulse laser high-precision ranging algorithm under low signal-to-noise ratio

- Special Issue on Geological Modeling and Geospatial Data Analysis

- Determination of luminescent characteristics of organometallic complex in land and coal mining

- InSAR terrain mapping error sources based on satellite interferometry

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Test influence of screen thickness on double-N six-light-screen sky screen target

- Analysis on the speed properties of the shock wave in light curtain

- Abundant accurate analytical and semi-analytical solutions of the positive Gardner–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili equation

- Measured distribution of cloud chamber tracks from radioactive decay: A new empirical approach to investigating the quantum measurement problem

- Nuclear radiation detection based on the convolutional neural network under public surveillance scenarios

- Effect of process parameters on density and mechanical behaviour of a selective laser melted 17-4PH stainless steel alloy

- Performance evaluation of self-mixing interferometer with the ceramic type piezoelectric accelerometers

- Effect of geometry error on the non-Newtonian flow in the ceramic microchannel molded by SLA

- Numerical investigation of ozone decomposition by self-excited oscillation cavitation jet

- Modeling electrostatic potential in FDSOI MOSFETS: An approach based on homotopy perturbations

- Modeling analysis of microenvironment of 3D cell mechanics based on machine vision

- Numerical solution for two-dimensional partial differential equations using SM’s method

- Multiple velocity composition in the standard synchronization

- Electroosmotic flow for Eyring fluid with Navier slip boundary condition under high zeta potential in a parallel microchannel

- Soliton solutions of Calogero–Degasperis–Fokas dynamical equation via modified mathematical methods

- Performance evaluation of a high-performance offshore cementing wastes accelerating agent

- Sapphire irradiation by phosphorus as an approach to improve its optical properties

- A physical model for calculating cementing quality based on the XGboost algorithm

- Experimental investigation and numerical analysis of stress concentration distribution at the typical slots for stiffeners

- An analytical model for solute transport from blood to tissue

- Finite-size effects in one-dimensional Bose–Einstein condensation of photons

- Drying kinetics of Pleurotus eryngii slices during hot air drying

- Computer-aided measurement technology for Cu2ZnSnS4 thin-film solar cell characteristics

- QCD phase diagram in a finite volume in the PNJL model

- Study on abundant analytical solutions of the new coupled Konno–Oono equation in the magnetic field

- Experimental analysis of a laser beam propagating in angular turbulence

- Numerical investigation of heat transfer in the nanofluids under the impact of length and radius of carbon nanotubes

- Multiple rogue wave solutions of a generalized (3+1)-dimensional variable-coefficient Kadomtsev--Petviashvili equation

- Optical properties and thermal stability of the H+-implanted Dy3+/Tm3+-codoped GeS2–Ga2S3–PbI2 chalcohalide glass waveguide

- Nonlinear dynamics for different nonautonomous wave structure solutions

- Numerical analysis of bioconvection-MHD flow of Williamson nanofluid with gyrotactic microbes and thermal radiation: New iterative method

- Modeling extreme value data with an upside down bathtub-shaped failure rate model

- Abundant optical soliton structures to the Fokas system arising in monomode optical fibers

- Analysis of the partially ionized kerosene oil-based ternary nanofluid flow over a convectively heated rotating surface

- Multiple-scale analysis of the parametric-driven sine-Gordon equation with phase shifts

- Magnetofluid unsteady electroosmotic flow of Jeffrey fluid at high zeta potential in parallel microchannels

- Effect of plasma-activated water on microbial quality and physicochemical properties of fresh beef

- The finite element modeling of the impacting process of hard particles on pump components

- Analysis of respiratory mechanics models with different kernels

- Extended warranty decision model of failure dependence wind turbine system based on cost-effectiveness analysis

- Breather wave and double-periodic soliton solutions for a (2+1)-dimensional generalized Hirota–Satsuma–Ito equation

- First-principle calculation of electronic structure and optical properties of (P, Ga, P–Ga) doped graphene

- Numerical simulation of nanofluid flow between two parallel disks using 3-stage Lobatto III-A formula

- Optimization method for detection a flying bullet

- Angle error control model of laser profilometer contact measurement

- Numerical study on flue gas–liquid flow with side-entering mixing

- Travelling waves solutions of the KP equation in weakly dispersive media

- Characterization of damage morphology of structural SiO2 film induced by nanosecond pulsed laser

- A study of generalized hypergeometric Matrix functions via two-parameter Mittag–Leffler matrix function

- Study of the length and influencing factors of air plasma ignition time

- Analysis of parametric effects in the wave profile of the variant Boussinesq equation through two analytical approaches

- The nonlinear vibration and dispersive wave systems with extended homoclinic breather wave solutions

- Generalized notion of integral inequalities of variables

- The seasonal variation in the polarization (Ex/Ey) of the characteristic wave in ionosphere plasma

- Impact of COVID 19 on the demand for an inventory model under preservation technology and advance payment facility

- Approximate solution of linear integral equations by Taylor ordering method: Applied mathematical approach

- Exploring the new optical solitons to the time-fractional integrable generalized (2+1)-dimensional nonlinear Schrödinger system via three different methods

- Irreversibility analysis in time-dependent Darcy–Forchheimer flow of viscous fluid with diffusion-thermo and thermo-diffusion effects

- Double diffusion in a combined cavity occupied by a nanofluid and heterogeneous porous media

- NTIM solution of the fractional order parabolic partial differential equations

- Jointly Rayleigh lifetime products in the presence of competing risks model

- Abundant exact solutions of higher-order dispersion variable coefficient KdV equation

- Laser cutting tobacco slice experiment: Effects of cutting power and cutting speed

- Performance evaluation of common-aperture visible and long-wave infrared imaging system based on a comprehensive resolution

- Diesel engine small-sample transfer learning fault diagnosis algorithm based on STFT time–frequency image and hyperparameter autonomous optimization deep convolutional network improved by PSO–GWO–BPNN surrogate model

- Analyses of electrokinetic energy conversion for periodic electromagnetohydrodynamic (EMHD) nanofluid through the rectangular microchannel under the Hall effects

- Propagation properties of cosh-Airy beams in an inhomogeneous medium with Gaussian PT-symmetric potentials

- Dynamics investigation on a Kadomtsev–Petviashvili equation with variable coefficients

- Study on fine characterization and reconstruction modeling of porous media based on spatially-resolved nuclear magnetic resonance technology

- Optimal block replacement policy for two-dimensional products considering imperfect maintenance with improved Salp swarm algorithm

- A hybrid forecasting model based on the group method of data handling and wavelet decomposition for monthly rivers streamflow data sets

- Hybrid pencil beam model based on photon characteristic line algorithm for lung radiotherapy in small fields

- Surface waves on a coated incompressible elastic half-space

- Radiation dose measurement on bone scintigraphy and planning clinical management

- Lie symmetry analysis for generalized short pulse equation

- Spectroscopic characteristics and dissociation of nitrogen trifluoride under external electric fields: Theoretical study

- Cross electromagnetic nanofluid flow examination with infinite shear rate viscosity and melting heat through Skan-Falkner wedge

- Convection heat–mass transfer of generalized Maxwell fluid with radiation effect, exponential heating, and chemical reaction using fractional Caputo–Fabrizio derivatives

- Weak nonlinear analysis of nanofluid convection with g-jitter using the Ginzburg--Landau model

- Strip waveguides in Yb3+-doped silicate glass formed by combination of He+ ion implantation and precise ultrashort pulse laser ablation

- Best selected forecasting models for COVID-19 pandemic

- Research on attenuation motion test at oblique incidence based on double-N six-light-screen system

- Review Articles

- Progress in epitaxial growth of stanene

- Review and validation of photovoltaic solar simulation tools/software based on case study

- Brief Report

- The Debye–Scherrer technique – rapid detection for applications

- Rapid Communication

- Radial oscillations of an electron in a Coulomb attracting field

- Special Issue on Novel Numerical and Analytical Techniques for Fractional Nonlinear Schrodinger Type - Part II

- The exact solutions of the stochastic fractional-space Allen–Cahn equation

- Propagation of some new traveling wave patterns of the double dispersive equation

- A new modified technique to study the dynamics of fractional hyperbolic-telegraph equations

- An orthotropic thermo-viscoelastic infinite medium with a cylindrical cavity of temperature dependent properties via MGT thermoelasticity

- Modeling of hepatitis B epidemic model with fractional operator

- Special Issue on Transport phenomena and thermal analysis in micro/nano-scale structure surfaces - Part III

- Investigation of effective thermal conductivity of SiC foam ceramics with various pore densities

- Nonlocal magneto-thermoelastic infinite half-space due to a periodically varying heat flow under Caputo–Fabrizio fractional derivative heat equation

- The flow and heat transfer characteristics of DPF porous media with different structures based on LBM

- Homotopy analysis method with application to thin-film flow of couple stress fluid through a vertical cylinder

- Special Issue on Advanced Topics on the Modelling and Assessment of Complicated Physical Phenomena - Part II

- Asymptotic analysis of hepatitis B epidemic model using Caputo Fabrizio fractional operator

- Influence of chemical reaction on MHD Newtonian fluid flow on vertical plate in porous medium in conjunction with thermal radiation

- Structure of analytical ion-acoustic solitary wave solutions for the dynamical system of nonlinear wave propagation

- Evaluation of ESBL resistance dynamics in Escherichia coli isolates by mathematical modeling

- On theoretical analysis of nonlinear fractional order partial Benney equations under nonsingular kernel

- The solutions of nonlinear fractional partial differential equations by using a novel technique

- Modelling and graphing the Wi-Fi wave field using the shape function

- Generalized invexity and duality in multiobjective variational problems involving non-singular fractional derivative

- Impact of the convergent geometric profile on boundary layer separation in the supersonic over-expanded nozzle

- Variable stepsize construction of a two-step optimized hybrid block method with relative stability

- Thermal transport with nanoparticles of fractional Oldroyd-B fluid under the effects of magnetic field, radiations, and viscous dissipation: Entropy generation; via finite difference method

- Special Issue on Advanced Energy Materials - Part I

- Voltage regulation and power-saving method of asynchronous motor based on fuzzy control theory

- The structure design of mobile charging piles

- Analysis and modeling of pitaya slices in a heat pump drying system

- Design of pulse laser high-precision ranging algorithm under low signal-to-noise ratio

- Special Issue on Geological Modeling and Geospatial Data Analysis

- Determination of luminescent characteristics of organometallic complex in land and coal mining

- InSAR terrain mapping error sources based on satellite interferometry