Abstract

Selenium-binding protein 1 (SELENBP1) is frequently dysregulated in various malignancies including colorectal cancer (CRC); however, its roles in progression of CRCs and the underlying mechanism remain to be elucidated. In this study, we compared the expression of SELENBP1 between CRCs and colorectal normal tissues (NTs), as well as between primary and metastatic CRCs; we determined the association between SELENBP1 expression and CRC patient prognoses; we conducted both in vitro and in vivo experiments to explore the functional roles of SELENBP1 in CRC progression; and we characterized the potential underlying mechanisms associated with SELENBP1 activities. We found that the expression of SELENBP1 was significantly and consistently decreased in CRCs than that in adjacent NTs, while significantly and frequently decreased in metastatic than primary CRCs. High expression of SELENBP1 was an independent predictor of favorable prognoses in CRC patients. Overexpression of SELENBP1 suppressed, while silencing of SELENBP1 promoted cell proliferation, migration and invasion, and in vivo tumorigenesis of CRC. Mechanically, SELENBP1 may suppress CRC progression by inhibiting the epithelial–mesenchymal transition.

1 Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most prevalent and fatal malignancies worldwide [1]. Radical surgery alone or in combination with adjuvant therapies has been effective in CRC patients at earlier stages; however, many of these patients experience recurrence within the next several years, while approximately 20% of CRC patients already have metastatic diseases at the time of diagnosis [2]. Although some contributing events have been identified for the progression of CRCs [3,4,5], our understanding of this process is still limited. Characterizing the underlying mechanisms of CRC progression and identifying novel biomarkers are therefore urgently needed.

Selenium-binding protein 1 (SELENBP1), one of the proteins that directly bind to selenium, is encoded by a gene located at 1q21.3 near the epidermal differentiation complex (EDC), which is closely related to terminal differentiation of the human epidermis [6]. Previous evidence showed that SELENBP1 participated in a variety of physiological processes, such as cell differentiation and maturation [7,8], protein transport and degradation [9,10], and H2S biosynthesis and adipogenesis [11], while mutations in SELENBP1 caused dysregulated methanethiol oxidation and extraoral halitosis [12]. As a binding partner for selenium, SELENBP1 may mediate the connection between selenium deficiency and carcinogenesis [13]. Actually, suppression of SELENBP1 has been associated with carcinogenesis and disease progression in CRC [7,14] and many other malignancies [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]; however, the underlying mechanism is not fully elucidated. Besides, the emerging open access datasets in recent years necessitate further validation of these pilot studies.

In the current study, we utilized data from the Human Protein Atlas (HPA), the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) to determine SELENBP1 expression under physiological conditions and compare the expression of SELENBP1 between CRCs and colorectal normal tissues (NTs), as well as between primary and metastatic CRCs. We also used TCGA Colon Adenocarcinoma (COAD) and Rectum Adenocarcinoma (READ) datasets (combined into the TCGA cohort), and a tissue microarray cohort [the tissue microarray (TMA) cohort] to validate the association between SELENBP1 expression and CRC patient prognoses. Furthermore, we conducted both in vitro and in vivo experiments to explore the functional roles of SELENBP1 in CRC progression. Finally, we characterized the potential underlying mechanisms associated with SELENBP1 activities.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Access to public datasets

HPA is an open access program that integrates various omics data to map all the human proteins in cells, tissues, and organs (www.proteinatlas.org) [23]. We used HPA to predict SELENBP1 expression under both physiological and pathological conditions. We then searched CRC datasets that compared gene transcription between normal colorectal mucosae and CRCs, or between primary and metastatic CRCs in the GEO database [24], as described in our previously report [25]. Eleven datasets were retrieved to compare SELENBP1 expression between NTs and CRCs, including GSE3629 [26], GSE28000 [27], GSE31279 [28], GSE37182 [29], GSE44861 [30], GSE87221 [31], GSE90627 [32], GSE106582 (unpublished data), GSE6988 [33], GSE21510 [34], and GSE62322 [35]. We also downloaded the TCGA COAD and READ datasets from UCSC Xena (https://xenabrowser.net/heatmap/) and combined them into one CRC dataset[*]. These 12 datasets included 767 NTs and 1224 CRCs. In addition, 15 datasets containing both primary and metastatic CRCs were retrieved from GEO (GSE6988 [33], GSE18105 [36], GSE21510 [34], GSE27854 [37], GSE28722 [38], GSE29623 [39], GSE38832 [40], GSE40967 [41], GSE41568 [42], GSE51244 (unpublished data), GSE62322 [35], GSE71222 [43], GSE81582 [44], GSE81986 [45], and GSE68648 [46]), which included 1,534 primary and 667 metastatic CRCs.

2.2 Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

To explore the potential mechanisms of SELENBP1 in CRC progression, a GSEA was employed using the combined TCGA COAD and READ datasets [47,48]. Gene sets with a false discovery rate q-value of <0.25 and a nominal p value of <0.05 were regarded as significantly enriched.

2.3 CRC TMA and immunohistochemical (IHC) staining

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee at Shanghai Fifth People’s Hospital and adhered to the principles listed in the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. Collection of clinical samples and preparation of TMA were performed as described previously [25]. Detailed clinical variables of the TMA cohort, such as patient age and sex, are listed in Table 1. IHC staining and review of slides were performed as described in our previous report [49], using an immunoreactive score (IRS) system [50]. An anti-SELENBP1 rabbit polyclonal antibody was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (HPA005741; St. Louis, MO, USA) and used at a dilution of 1:50.

Clinical significance of SELENBP1 expression in colon cancers (n = 100)

| Clinicopathological features | Cases (N) | SELENBP1 expression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | P-value | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 59 | 35 | 24 | |

| Female | 41 | 28 | 13 | 0.405 |

| Age | ||||

| <67 | 43 | 26 | 17 | |

| ≥67 | 57 | 37 | 20 | 0.680 |

| Histological grade | ||||

| G2 | 70 | 41 | 29 | |

| G3 | 30 | 22 | 8 | 0.182 |

| Tumor size (cm) | ||||

| <7 | 70 | 38 | 32 | |

| ≥7 | 30 | 25 | 5 | 0.007 |

| Lymph node metastasis (n) | ||||

| <3 | 84 | 50 | 34 | |

| ≥3 | 16 | 13 | 3 | 0.157 |

| pStage | ||||

| I/II | 51 | 32 | 19 | |

| III/IV | 49 | 31 | 18 | 1.000 |

| Gross typing | ||||

| Protruded | 20 | 15 | 5 | |

| Ulcerative | 47 | 24 | 23 | |

| Infiltrative | 25 | 16 | 9 | |

| Colloid | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0.030 |

| Location | ||||

| Transverse colon | 7 | 5 | 2 | |

| Left colon | 42 | 26 | 16 | |

| Right colon | 51 | 32 | 19 | 0.904 |

2.4 Cell culture

A colon epithelial cell line fetal human cells (FHC) and four human CRC cell lines COLO205, COLO320DM, HCT116, and HT15 were obtained from the Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco′s Modified Eagle′s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 µg/mL of penicillin, and 100 mg/mL of streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA) [25].

2.5 Cell viability assays

A Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay was conducted as described in our previously study [25]. Briefly, stably transfected HCT15 and HCT116 cells (5 × 103 cells per well) were seeded in 96-well plates and cultivated overnight. Then, cells were serum-starved for another 24 h and 10% CCK-8 reagent (v/v in serum-free DMEM) was added to each well of the 96-well plates at 24, 48, 72, or 96 h. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured 1 h after addition of the reagent.

2.6 Cell proliferation assays

An EdU incorporation assay was performed using an EdU kit (C0071; Beyotime, Nantong, China) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. Briefly, stably transfected HCT15 and HCT116 cells (1 × 105 cells/mL) were seeded in 6-well plates and cultivated for 24–48 h, and then 10 μM/L EDU was added to cells. After 2 h, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized by 0.3% Triton X-100, and stained with the Click Additive Solution in the kit. Cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 for 10 min. The number of EdU-positive cells was counted under a microscope in five random fields. All assays were independently performed in triplicate.

2.7 Transwell migration and invasion assays

These assays were conducted as described in our previous report [51]. Briefly, cells (4 × 105 cells/mL) were seeded in serum-free DMEM in the top chamber of a Transwell® insert coated without (migration assay) or with (invasion assay) Matrigel. The medium containing 20% FBS in the lower chamber served as a chemoattractant. After incubation for 24 h at 37°C, the cells on the top side of the membrane were removed with a cotton swab and those on the bottom side were fixed with methanol for 20 min and then stained with crystal violet (0.1% in PBS) for 15 min. Five randomly selected fields per well were photographed, and the numbers of migrated cells were enumerated.

2.8 Protein extraction and western blotting (WB)

Proteins were extracted and plotted as previously described [51]. Primary and secondary antibodies used are listed in Table S1. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (1:2,000 dilutions, rabbit anti-human; Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) served as a loading control.

2.9 Ectopic expression or silencing of SELENBP1

Lentiviral plasmids expressing SELENBP1 (using GV367 vector), short hairpin RNA oligos of SELENBP1 (using GV248 vector), or respective controls were constructed by Shanghai Genechem Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). The target sequences were CACTTATATGTATGGGACT (shSELENBP1) and TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT (scramble control). Transfection and construction of stable transfectants were performed as previously reported [25].

2.10 Animal experiments

Female athymic BALB/c nude mice of 6–8 weeks old were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Beijing, China) and maintained in the Animal Experimental Facility of Normal University of Eastern China in a pathogen-free environment. HCT-15 cells (2 × 106/mouse) stably expressing SELENBP1 or the vector were seeded subcutaneously into flanks of mice (n = 5 per group) and tumor growth was closely monitored twice a week (tumor volume = length × width2 × 3.14/6). One month after inoculation, tumors were isolated and weighed (g), and growth curves were drawn. Tumor samples were prepared for further use. All experiment procedures were conducted according to the Animal Care and Use guideline and were approved by the Animal Care Committee at the Normal University of Eastern China.

2.11 Immunofluorescence (IF) staining

The TMA was stained with antibodies against SELENBP1, E-cadherin, and N-cadherin by Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd (Wuhan, China) according to their standard protocols as previously described [52] and signals were quantified by the same company using procedures recommended by Stephan et al. [53].

2.12 Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism7 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA), Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA), and SPSS statistical software for Windows, version 22 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Independent sample t-test or one-way analysis of variance was performed for comparisons of continuous variables. Nonparametric tests were performed if data did not follow a normal distribution. Pearson’s χ 2 test and Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical comparisons. IRSs of SELENBP1 staining in CRCs and paired NTs were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Survival analyses were conducted using the Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate survival analyses were conducted with a Cox proportional hazards regression model. Statistical significance was defined as a value of p < 0.05. All statistical tests were two-sided.

-

Compliance with ethical standards: The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee at the Fifth People’s Hospital of Shanghai, Fudan University (Ethical Approval Form no. 2017-097) and adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to tissue collection for experimentation.

3 Results

3.1 SELENBP1 expression was suppressed during CRC metastasis

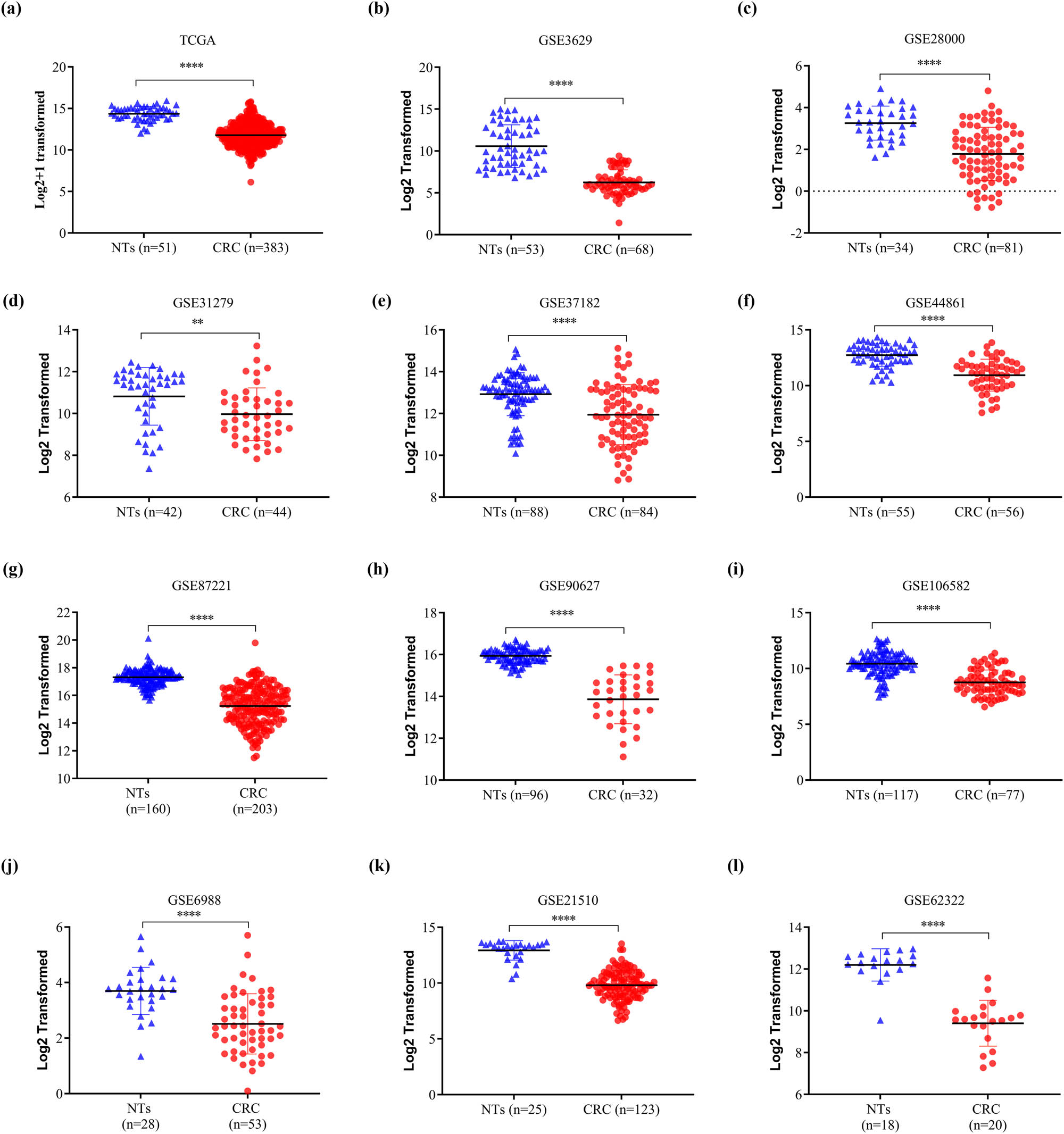

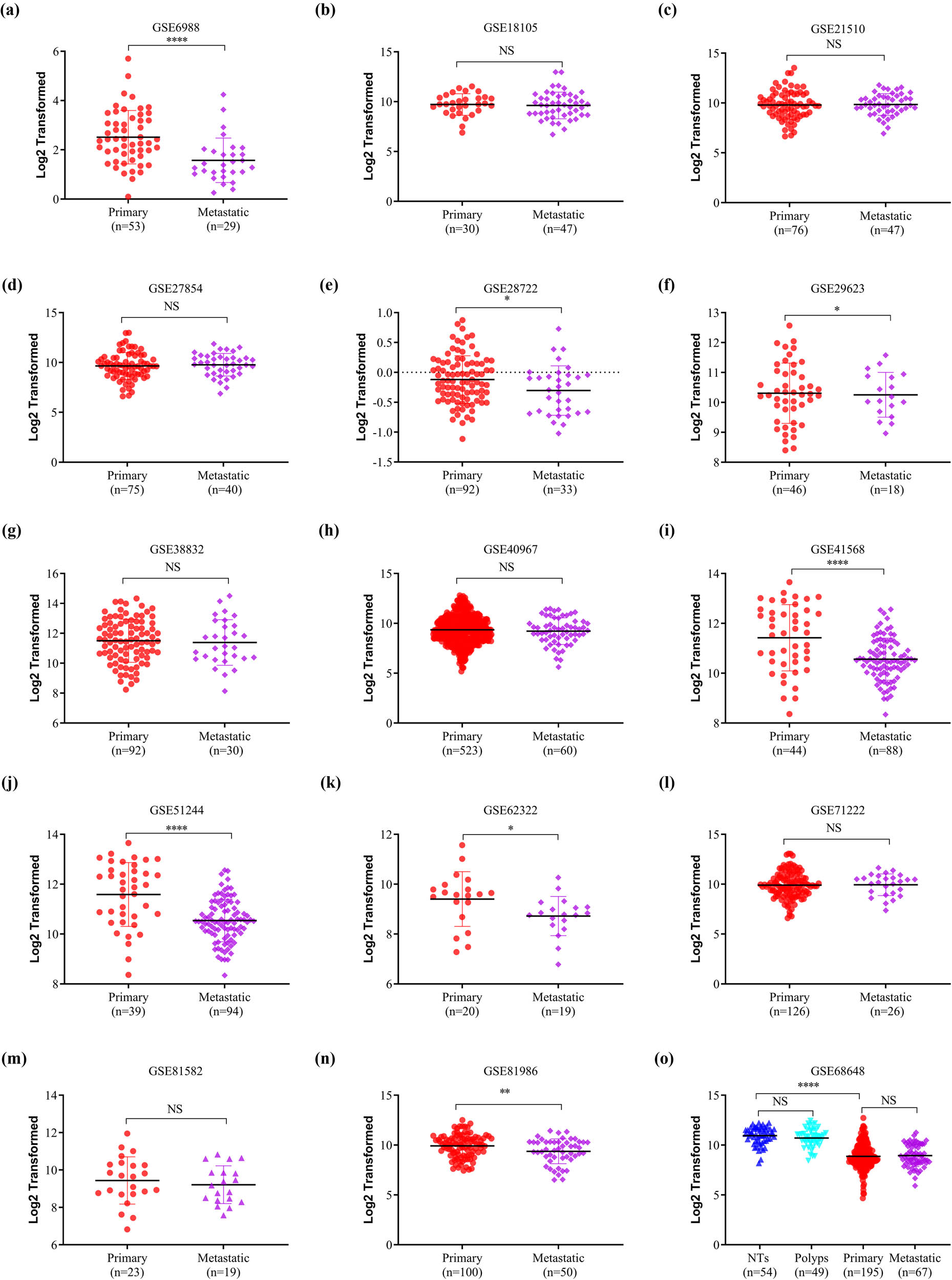

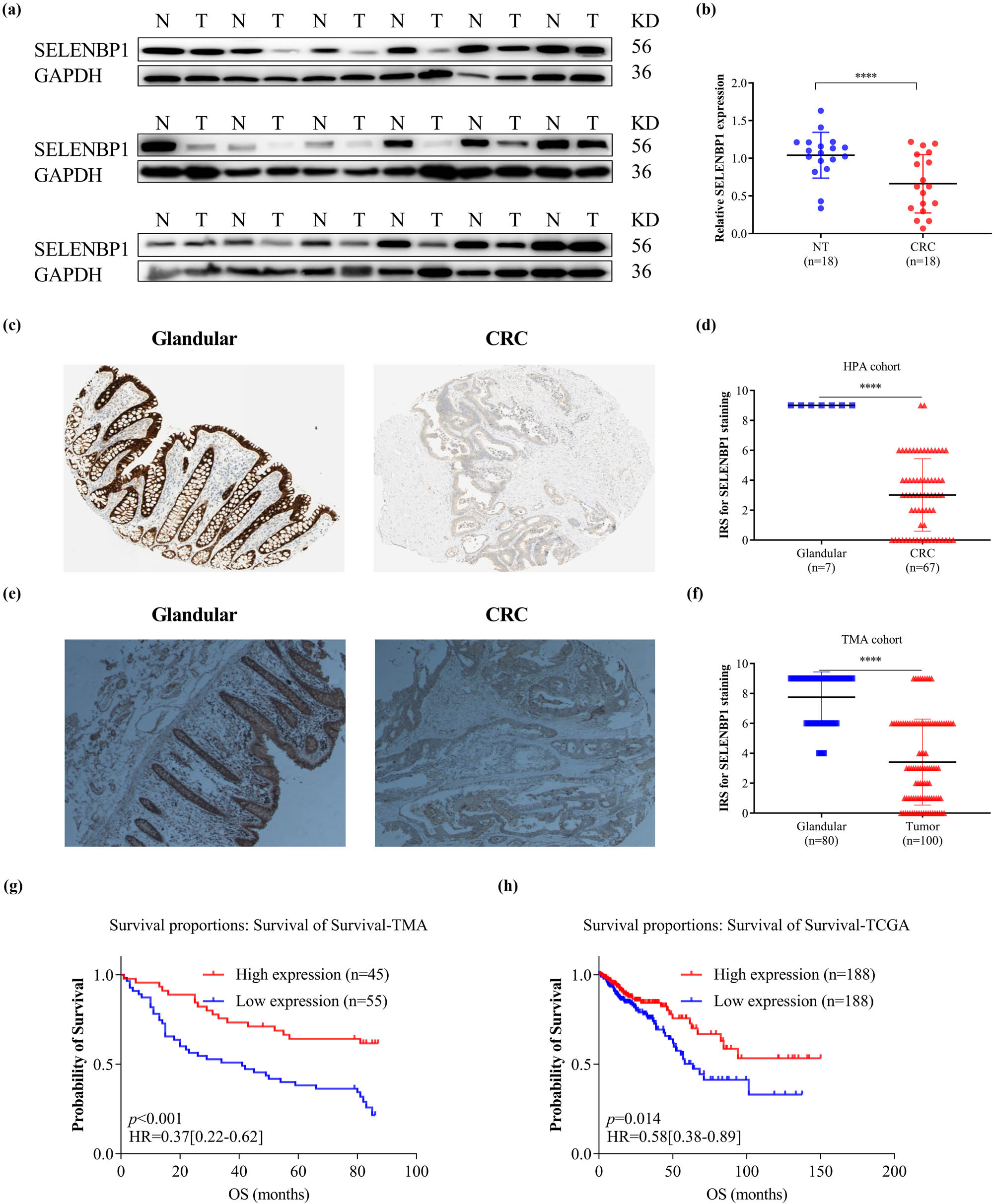

The HPA database was used to examine SELENBP1 expression profiles under physiological conditions. As shown in Figure S1, the mRNA and protein expressions of SELENBP1 were most abundant in the colon, rectum, and thyroid, followed by liver, lung, and appendix, suggesting its functional relevance in these organs. To further elucidate the roles of SELENBP1 in CRC progression, 12 and 15 public datasets were used to examine the differences of SELENBP1 mRNA expressions between CRCs and colorectal NTs, and between primary and metastatic CRCs, respectively. The mRNA expression of SELENBP1 was dramatically decreased in CRCs compared to that in NTs (all, p < 0.01; Figure 1a–l). In addition, SELENBP1 expression was significantly lower in metastatic than in primary CRCs in seven out of 15 datasets (Figure 2a–o). Meanwhile, no significant difference in SELENBP1 expression was observed between NTs and polyps (Figure 2o). To validate these observations, we first examined the protein content of SELENBP1 in 18 paired CRC samples. As shown in Figure 3a and b, SELENBP1 expression was significantly decreased in most CRCs compared to their matched NTs. Then, IHC staining of SELENBP1 in colorectal NTs and CRCs in the HPA database indicated that SELENBP1 was distributed diffusively in the nuclei and cytoplasm and on the membrane, and its expression was significantly lower in tumor cells than in glandular cells (p < 0.0001; Figure 3c and d). These observations were further confirmed by IHC staining of SELENBP1 in 100 CRCs and 80 NTs, which showed that the intensity of SELENBP1 expression was much less in tumors than in adjacent NTs (p < 0.0001; Figure 3e and f). Taken together, these results suggest that suppression of SELENBP1 is common during carcinogenesis and frequent during the metastasis of CRCs.

SELENBP1 expression is consistently downregulated in CRCs. The expression of SELENBP1 was compared between colorectal NTs and CRCs in 12 datasets from the TCGA and GEO databases (a–l). ** p < 0.01; **** p < 0.0001 vs the control group.

SELENBP1 expression is frequently downregulated in metastatic CRCs. The expression of SELENBP1 was compared between primary and metastatic CRCs in 15 datasets (a–o), and among different stages of colorectal tumors in one dataset (o). Abbreviation: NS, nonsignificant. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; **** p < 0.0001 vs the control group.

Suppressed expression of SELENBP1 in CRCs is associated with poor patient survival. The expression of SELENBP1 protein was detected by WB in 18 pairs of NTs and CRCs (a) and quantified by gray-scale analysis (b). Immunohistochemistry data of SELENBP1 were downloaded from the HPA database and compared between glandular tissues and CRCs using an IRS method (c and d). A TMA consisting of 100 CRCs and 80 NTs was stained with an anti-SELENBP1 antibody (d, 40×) and the IRS was evaluated (f). Kaplan–Meier plots were drawn for OS of patients in the TMA cohort (g) and TCGA cohort (h). Patients were stratified into low and high SELENBP1 expression groups according to SELENBP1 mRNA expression in the TCGA cohort and IRS of SELENBP1 in the TMA cohort (<median vs ≥median). Values of p were obtained using the log-rank test. Censored data are indicated by the + symbol. *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.0001 vs the control group.

3.2 Suppression of SELENBP1 in CRCs correlated with an unfavorable prognosis

To test whether SELENBP1 suppression in CRCs contributed to increased tumor invasiveness, we analyzed the relationships between SELENBP1 expression and clinicopathological variables. As shown in Table 1, SELENBP1 expression was significantly associated with tumor size and gross typing.

Next, we determined the relationship between SELENBP1 expression and patient outcomes in the tissue microarray cohort. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis revealed that patients with high SELENBP1 expression had a better overall survival (OS) than those with low expression (Figure 3g). Using multivariate analysis with a Cox proportional hazards model, high SELENBP1 expression was significantly associated with a better OS, after adjustment for age, tumor size, lymph node metastasis number, and TNM stage (Table 2). Similarly, a Kaplan–Meier survival analysis using the combined TCGA COAD and READ dataset also revealed that high SELENBP1 expression was correlated with a better OS in patients (Figure 3h). Along with those already reported in the literature [7,14], these findings clearly indicate that SELENBP1 is a prognostic marker in CRCs and its abundance in tumors could predict favorable prognoses.

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models for overall survival in CRC patients (n = 100)

| Clinicopathological features | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR [95% CIs] | P-value | HR [95% CIs] | P-value | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Female | 0.78[0.44–1.38] | 0.389 | ||

| Age | ||||

| <67 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| ≥67 | 1.90[1.05–3.44] | 0.033 | 2.90[1.52–5.53] | 0.001 |

| Histological grade | ||||

| G2 | 1 [Reference] | |||

| G3 | 1.40[0.78–2.50] | 0.260 | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | ||||

| <7 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| ≥7 | 1.79[1.01–3.16] | 0.045 | 1.64[0.90–3.01] | 0.110 |

| Lymph node metastasis (n) | ||||

| <3 | 1 [Reference] | 0.000 | ||

| ≥3 | 4.69[2.50–8.77] | 4.30[1.99–9.31] | 0.000 | |

| pStage | ||||

| I/II | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 0.068 | |

| III/IV | 1.82[1.04–3.19] | 0.035 | 1.92[0.95–3.87] | |

| Gross typing | ||||

| Protruded | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Ulcerative | 0.80[0.39–1.65] | 0.547 | ||

| Infiltrative | 0.83[0.37–1.85] | 0.650 | ||

| Colloid | 1.23[0.43–3.54] | 0.704 | ||

| Tumor location | ||||

| Left colon | 1 [Reference] | 0.821 | ||

| Right colon | 0.94[0.53–1.66] | |||

| Transverse colon | 1.13[0.39–3.28] | 0.822 | ||

| SELENBP1 expression | ||||

| Low | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| High | 0.42[0.23–0.76] | 0.004 | 0.34[0.17–0.68] | 0.002 |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

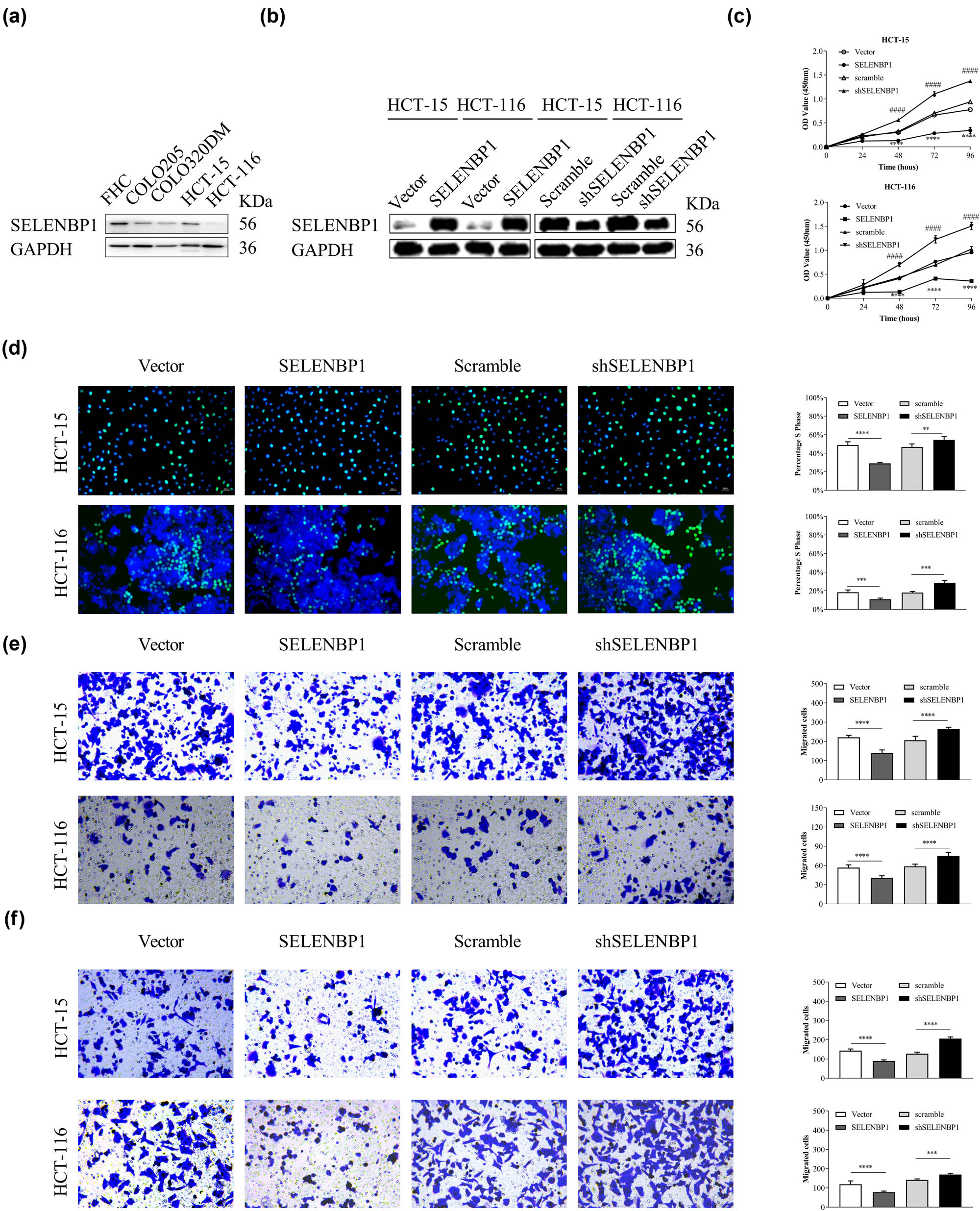

3.3 SELENBP1 inhibited CRC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion

To investigate the in vitro activities of SELENBP1 in CRC, we first compared its expression in a fetal colon cell line FHC and four CRC cell lines. As shown in Figure 4a, the expression of SELENBP1 was decreased in CRC cell lines compared to that in FHC. We then induced or knocked down the expression of SELENBP1 in HCT-15 and HCT-116 cells using lentiviruses (Figure 4b) and carried out CCK-8, Edu, Transwell® migration, and invasion assays. The results showed that overexpression of SELENBP1 inhibited while knocking down of SELENBP1 promoted cell viability (Figure 4c), proliferation (Figure 4d), migration (Figure 4e), and invasion (Figure 4f) in both cell lines. Taken together, these observations indicate that SELENBP1 has tumor-suppressive roles in vitro.

SELENBP1 inhibits cell proliferation, migration, and invasion of cultured CRC cells. The expression of SELENBP1 protein was determined in a fetal colon cell line FHC and several CRC cell lines (a). SELENBP1 was inducibly overexpressed and silenced in HCT-15 and HCT-116 cells (b). The in vitro effects of SELENBP1 on cell proliferation, migration, and invasion were evaluated by CCK-8 (c), Edu (d), Transwell migration (e), and invasion (f) assays, respectively. Experiments were repeated independently at least three times, and data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.0001 vs the control group; #### p < 0.0001 vs the control group (for shSELENBP1 vs scramble in the CCK-8 assays only).

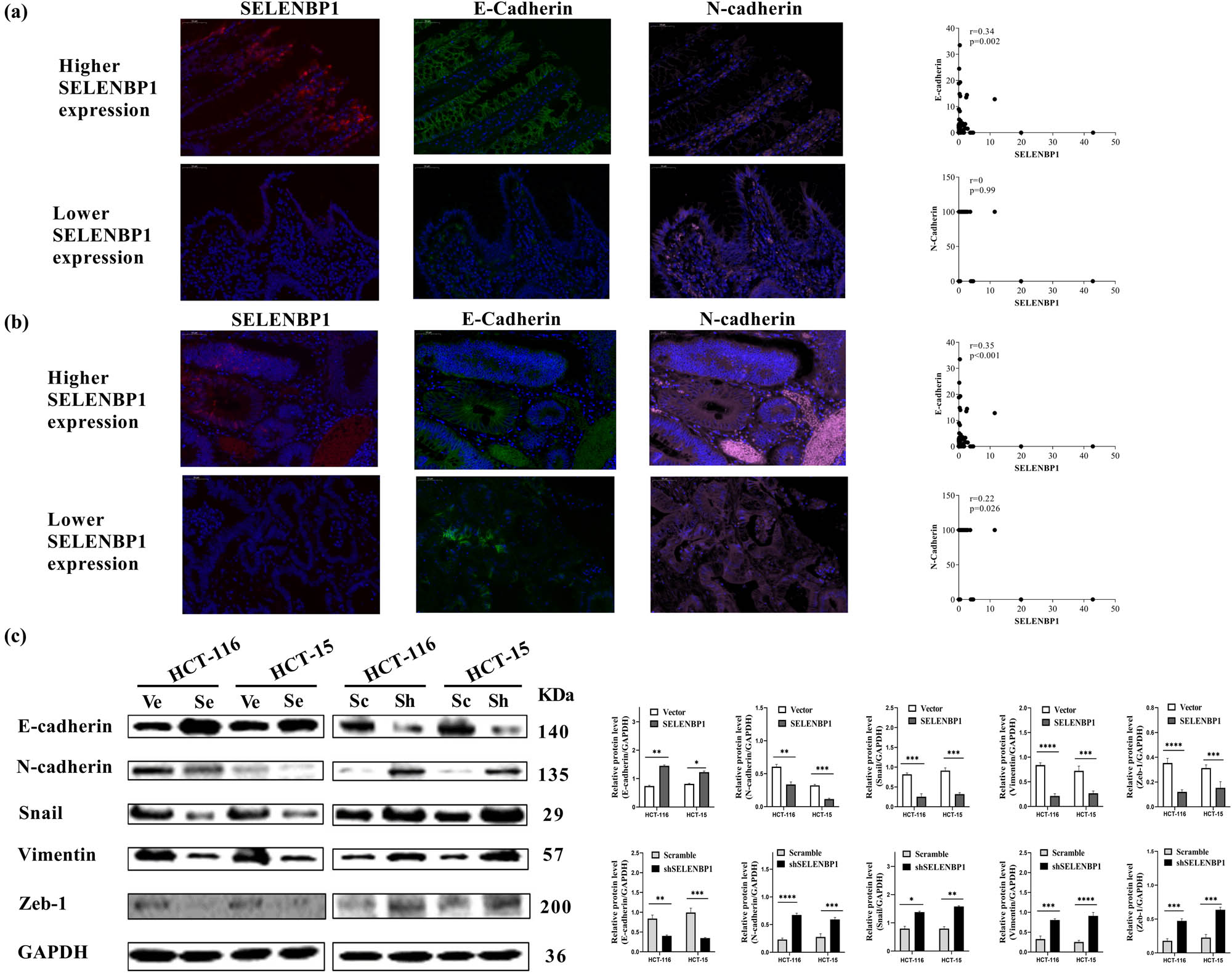

3.4 SELENBP1 may inhibit CRC progression by modulating epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT)

To characterize the potential mechanism of SELENBP1 in inhibiting tumor progression, we first used the combined TCGA COAD and READ dataset to conduct a GSEA [54] and found that high SELENBP1 expression was negatively correlated with the hallmark EMT gene set (Figure S2a). Subsequent gene–gene correlation analyses using the same dataset further confirmed that the expression of SELENBP1 was positively correlated with that of CDH1 but negatively correlated with that of CDH2 and several other EMT markers and transcription factors both in NTs (Figure S2b) and CRCs (Figure S2c). To further confirm these observations, we investigated the relationship between SELENBP1 and E-cadherin or N-cadherin in NTs and CRCs by staining the tissue microarray with IF. As shown in Figure 5, SELENBP1 was located in colon mucosae and its expression correlated with that of E-cadherin in both NTs (A) and CRCs (B). By contrast, no consistent trend was observed between SELENBP1 and N-cadherin, as the expression of N-cad was diffusive in these samples. In addition, overexpression of SELENBP1 increased the expression of E-cadherin but decreased that of N-cadherin, SNAIL, Vimentin, and Zeb-1 in CRC cell lines, which was reversed in cells with SELENBP1 silencing (Figure 5c). Taken together, these results indicate that SELENBP1 played an active role in antagonizing CRC progression via modulating EMT.

SELENBP1 inhibits EMT in CRC cells. A multicolor IF staining method was used to evaluate the expression and localization of SELENBP1 (red), E-cadherin (green), and N-cadherin (pink) in NTs (a) and CRCs (b), using the TMA cohort (scale bar = 50 μm). Percent of positive cells were calculated and correlation analyses were conducted based on the expression of these proteins (scatter plots on the right). Total proteins were extracted from HCT-15 and HCT-116 cells stably infected with SELENBP1, shSELENBP1, or relative control lentiviruses and were used to evaluate the expression of EMT markers and transcription factors by WB with GAPDH as a loading control (c). Experiments were repeated independently at least three times, and data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001 vs the control group.

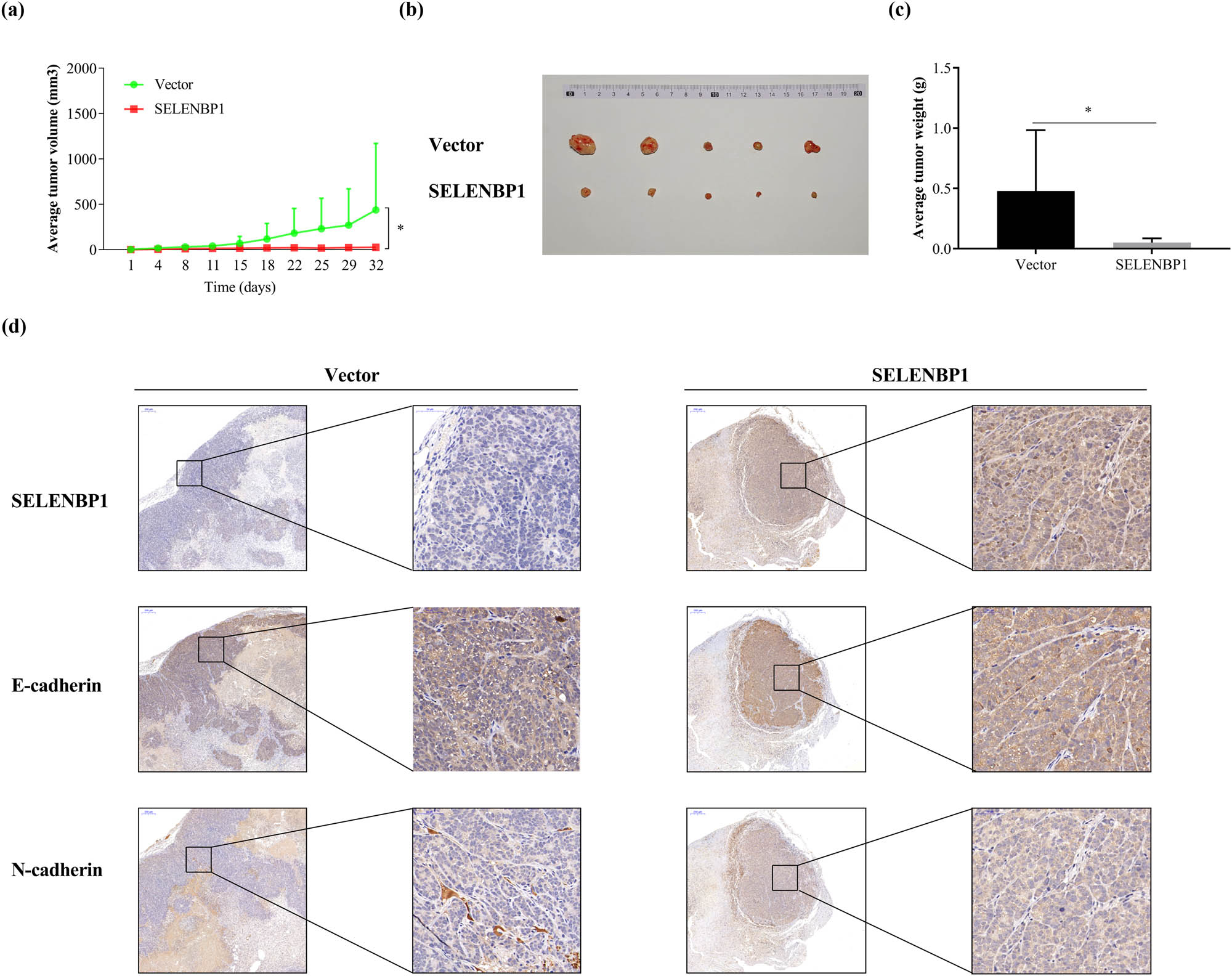

3.5 SELENBP1 inhibited in vivo tumorigenesis

To confirm whether SELENBP1 suppress CRC tumorigenesis in vivo, we inoculated HCT-15 cells that stably overexpressed SELENBP1 or the control subcutaneously into the flanks of nude mice (n = 5/group). As shown in Figure 6, SELENBP1 significantly inhibited tumor growth and tumor weight (a–c). Similar to the in vitro observations, SELENBP1 promoted E-cadherin but inhibited N-cadherin expression in vivo (Figure 6d).

SELENBP1 inhibits tumorigenesis of CRC cells. HCT-15 cells stably overexpressing SELENBP1 or vector were inoculated subcutaneously into the right flank of nude mice (n = 5 per group). Tumor growth was monitored twice a week (a). On Day 32 after inoculation, tumors were removed, photographed (b), and weighed (c). Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tumor blocks were cut into 5 μm sections and stained with respective antibodies against SELENBP1, E-cadherin, and N-cadherin (d). * p < 0.05 vs the control group.

4 Discussion

Although rapid progress has been made in recent years regarding the evolvement of CRCs, it is still incredibly challenging to interrupt this process. Identifying events that lead to progression of this malignancy could be beneficial, both clinically and scientifically. In the current study, we found that suppression of SELENBP1 might be such an event.

SELENBP1 was highly abundant in the colon and rectum under physiological conditions, but consistently suppressed in CRCs across different patient cohorts. A more remarkable suppression was observed in metastatic CRCs in some patient cohorts; in contrast, the expression of SELENBP1 was similar between NTs and polyps. Besides, suppression of SELENBP1 was correlated with increased tumor size and unfavorable patient prognosis, which validated the results from previous studies [7,14,55,56]. These observations, along with those from studies of other malignancies [15,16,17,22,57], suggest that suppression of SELENBP1 might be a common event during carcinogenesis across different malignancies, although the underlying mechanisms may vary.

Being a selenium-binding protein, SELENBP1 may duplicate some of the tumor-suppressive roles of selenium (Se), which is an essential trace mineral indispensable to human health [58]. In the form of selenocysteine, selenium constitutes the catalytic center of selenoproteins, such as glutathione peroxidases, iodothyronine deiodinases, and thioredoxin reductases. Many of these selenoproteins function as oxidoreductases that help maintain homeostasis of the internal environment by curbing the propagation of oxidative damages [59]. As such, selenium is regarded as an antioxidant, while inadequate selenium intake has been associated with increased cancer incidence and mortality [60]. Although initial clinical trials supported the use of dietary selenium replenishment in reducing both the incidence and mortality of cancer [61,62], later studies revealed that high selenium intake did not bring benefit, or even brought harmful effects [63,64,65]. The inconsistent efficacy of selenium as a candidate anticancer agent may in part be ascribed to its complex interactions with selenoproteins and selenium-binding proteins [9,13,17,55]. In the current study, we demonstrated that SELENBP1 has tumor-suppressive roles both in vitro and in vivo, in consistent with observations from other researchers [21,22,56]. Thus, the contribution of SELENBP1 should be considered in future selenium-oriented studies.

One intriguing observation was that SELENBP1 may inhibit EMT, which is one of the key processes mediating tumor metastasis [66]. The regulatory involvement of SELENBP1 in EMT has been reported in hepatobiliary tumors [22,67] but remains to be elucidated in CRC and other malignancies. Our investigation demonstrated that SELENBP1 induced the expression of E-cadherin and inhibited that of N-cadherin, which partly explains its suppressive roles during metastasis of CRC. The SELENBP1 gene located at chromosome 1q21.3 near the EDC, which contains genes that encode the S100A family members [6]. Amplification of 1q21.3, especially those fragments that encode the S100A family members, has been associated with tumor progression [68], while many of these family members are closely related to EMT and tumor metastasis [69–72]. Using the GEPIA database (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/), we found that the expression of SELENBP1 was negatively correlated with those of S100A1, S100A2, S100A3, S100A4, S100A7, S100A8, S100A9, S100A11, S100A12, and S100A13 in the TCGA COAD and READ datasets (data not shown). Thus, we surmise that SELENBP1 may interact with EDC genes to suppress EMT in CRCs.

Although this study presents some findings that are clinically and scientifically meaningful, there are some inherent limitations. First, we did not characterize the potential interaction of SELENBP1 with selenium and selenoproteins in CRC. Second, we did not observe a significant correlation between SELENBP1 expression and TNM staging in our patient cohort, maybe due to the sample size and patient heterogeneity. In addition, we only confirmed the in vivo tumor-suppressive activity of SELENBP1 using the subcutaneous xenograft model, since the cell lines we used failed to derive liver or lung metastasis. Finally, although we uncovered the inhibitory impact of SELENBP1 on EMT of CRCs, we did not further elaborate the underlying mechanism in the current study. These limitations should be addressed in future studies.

5 Conclusion

This study confirmed the active involvement of SELENBP1 in tumor progression of CRCs via modulating the EMT. SELENBP1 is therefore a candidate tumor suppressor, which should be further investigated in future studies.

Abbreviations

- CRC

-

colorectal cancer

- EMT

-

epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- GEO

-

Gene Expression Omnibus

- GSEA

-

gene set enrichment analysis

- HPA

-

Human Protein Atlas

- IHC

-

immunohistochemical

- SELENBP1

-

selenium-binding protein 1

- TCGA

-

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TCGA-COAD

-

The Cancer Genome Atlas Colorectal Adenocarcinoma

- TMA

-

tissue microarray

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the technological help from the Department of Pathology at our hospital for the IHC staining and data analysis. We also appreciate the valuable work done by Dr. Jun Hou at Zhongshan Hospital (Shanghai, China) for her interpretation of the IHC staining. The authors give special thanks to Shuyu Zheng from Shanghai Jiao Tong University, School of Medicine, for her help in proofreading the manuscript.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the Medical System of Shanghai Minhang District (grant numbers 2017MWDXK01 and 2020MWDXK02) and the Shanghai Minhang District Science and Technology Commission (grant numbers 2017MHZ02, 2019MHZ054, 2020MHZ080, and 2021MHZ038). The funding sources were not involved in the study design; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

-

Author contributions: Chongwei Ke, Gengming Niu, and Tao Song: study design; Xiaotian Zhang, Runqi Hong, Lanxin Bei, and Ximin Yang: conducted the experiments, Zhiqing Hu, Liang Chen, and He Meng: data analyses; Xiaotian Zhang and Gengming Niu: wrote the manuscript; Chongwei Ke and Gengming Niu: revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final article.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

[1] Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49.10.3322/caac.21660Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Tauriello DV, Calon A, Lonardo E, Batlle E. Determinants of metastatic competency in colorectal cancer. Mol Oncol. 2017;11(1):97–119.10.1002/1878-0261.12018Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Schmitt M, Greten FR. The inflammatory pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21:653–67.10.1038/s41577-021-00534-xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Saus E, Iraola-Guzmán S, Willis JR, Brunet-Vega A, Gabaldón T. Microbiome and colorectal cancer: Roles in carcinogenesis and clinical potential. Mol Asp Med. 2019;69:93–106.10.1016/j.mam.2019.05.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Jung G, Hernández-Illán E, Moreira L, Balaguer F, Goel A. Epigenetics of colorectal cancer: biomarker and therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(2):111–30.10.1038/s41575-019-0230-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Lioumi M, Olavesen MG, Nizetic D, Ragoussis J. High-resolution YAC fragmentation map of 1q21. Genomics. 1998;49(2):200–88.10.1006/geno.1998.5234Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Li T, Yang W, Li M, Byun DS, Tong C, Nasser S, et al. Expression of selenium-binding protein 1 characterizes intestinal cell maturation and predicts survival for patients with colorectal cancer. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008;52(11):1289–99.10.1002/mnfr.200700331Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Steinbrenner H, Micoogullari M, Hoang NA, Bergheim I, Klotz L-O, Sies H. Selenium-binding protein 1 (SELENBP1) is a marker of mature adipocytes. Redox Biol. 2019;20:489–95.10.1016/j.redox.2018.11.004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Jeong J-Y, Wang Y, Sytkowski AJ. Human selenium binding protein-1 (hSP56) interacts with VDU1 in a selenium-dependent manner. Biochemical Biophys Res Commun. 2009;379(2):583–8.10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.12.110Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Porat A, Sagiv Y, Elazar Z. A 56-kDa selenium-binding protein participates in intra-Golgi protein transport. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(19):14457–65.10.1074/jbc.275.19.14457Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Randi EB, Casili G, Jacquemai S, Szabo C. Selenium-binding protein 1 (SELENBP1) supports hydrogen sulfide biosynthesis and adipogenesis. Antioxid (Basel). 2021;10(3).10.3390/antiox10030361Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Pol A, Renkema GH, Tangerman A, Winkel EG, Engelke UF, de Brouwer APM, et al. Mutations in SELENBP1, encoding a novel human methanethiol oxidase, cause extraoral halitosis. Nat Genet. 2018;50(1):120–99.10.1038/s41588-017-0006-7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Yang M, Sytkowski AJ. Differential expression and androgen regulation of the human selenium-binding protein gene hSP56 in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58(14):3150–3.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Kim H, Kang HJ, You KT, Kim SH, Lee KY, Kim TI, et al. Suppression of human selenium-binding protein 1 is a late event in colorectal carcinogenesis and is associated with poor survival. Proteomics. 2006;6(11):3466–76.10.1002/pmic.200500629Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Huang KC, Park DC, Ng SK, Lee JY, Ni X, Ng WC, et al. Selenium binding protein 1 in ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(10):2433–40.10.1002/ijc.21671Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Ha YS, Lee GT, Kim YH, Kwon SY, Choi SH, Kim TH, et al. Decreased selenium-binding protein 1 mRNA expression is associated with poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma. World J Surgical Oncol. 2014;12:288.10.1186/1477-7819-12-288Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Zhang S, Li F, Younes M, Liu H, Chen C, Yao Q. Reduced selenium-binding protein 1 in breast cancer correlates with poor survival and resistance to the anti-proliferative effects of selenium. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63702.10.1371/journal.pone.0063702Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Zhang J, Dong W-G, Lin J. Reduced selenium-binding protein 1 is associated with poor survival rate in gastric carcinoma. Med Oncol (Northwood, London, Engl). 2011;28(2):481–7.10.1007/s12032-010-9482-7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Chen G, Wang H, Miller CT, Thomas DG, Gharib TG, Misek DE, et al. Reduced selenium-binding protein 1 expression is associated with poor outcome in lung adenocarcinomas. J Pathol. 2004;202(3):321–9.10.1002/path.1524Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Silvers AL, Lin L, Bass AJ, Chen G, Wang Z, Thomas DG, et al. Decreased selenium-binding protein 1 in esophageal adenocarcinoma results from posttranscriptional and epigenetic regulation and affects chemosensitivity. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(7):2009–21.10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2801Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Huang C, Ding G, Gu C, Zhou J, Kuang M, Ji Y, et al. Decreased selenium-binding protein 1 enhances glutathione peroxidase 1 activity and downregulates HIF-1α to promote hepatocellular carcinoma invasiveness. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(11):3042–53.10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0183Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Zhang XY, Gao PT, Yang X, Cai JB, Ding GY, Zhu XD, et al. Reduced selenium-binding protein 1 correlates with a poor prognosis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and promotes the cell epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Am J Transl Res. 2018;10(11):3567–78.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Sci (New York, NY). 2015;347(6220):1260419.10.1126/science.1260419Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Barrett T, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P, Evangelista C, Kim IF, Tomashevsky M, et al. NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets – update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(D1):D991–D5.10.1093/nar/gks1193Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Niu G, Deng L, Zhang X, Hu Z, Han S, Xu K, et al. GABRD promotes progression and predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Open Med (Wars). 2020;15(1):1172–83.10.1515/med-2020-0128Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Watanabe T, Kobunai T, Toda E, Kanazawa T, Kazama Y, Tanaka J, et al. Gene expression signature and the prediction of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer by DNA microarray. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(2 Pt 1):415–20.10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0753Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Jovov B, Araujo-Perez F, Sigel CS, Stratford JK, McCoy AN, Yeh JJ, et al. Differential gene expression between African American and European American colorectal cancer patients. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e30168.10.1371/journal.pone.0030168Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Abba M, Laufs S, Aghajany M, Korn B, Benner A, Allgayer H. Look who’s talking: deregulated signaling in colorectal cancer. Cancer Genomics Proteom. 2012;9(1):15–25.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Musella V, Verderio P, Reid JF, Pizzamiglio S, Gariboldi M, Callari M, et al. Effects of warm ischemic time on gene expression profiling in colorectal cancer tissues and normal mucosa. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53406.10.1371/journal.pone.0053406Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Ryan BM, Zanetti KA, Robles AI, Schetter AJ, Goodman J, Hayes RB, et al. Germline variation in NCF4, an innate immunity gene, is associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;134(6):1399–407.10.1002/ijc.28457Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Hosen MR, Militello G, Weirick T, Ponomareva Y, Dassanayaka S, Moore JB, et al. Airn Regulates Igf2bp2 Translation in Cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2018;122(10):1347–53.10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.312215Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Guo H, Zeng W, Feng L, Yu X, Li P, Zhang K, et al. Integrated transcriptomic analysis of distance-related field cancerization in rectal cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8(37):61107–17.10.18632/oncotarget.17864Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Ki DH, Jeung HC, Park CH, Kang SH, Lee GY, Lee WS, et al. Whole genome analysis for liver metastasis gene signatures in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(9):2005–12.10.1002/ijc.22975Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Tsukamoto S, Ishikawa T, Iida S, Ishiguro M, Mogushi K, Mizushima H, et al. Clinical significance of osteoprotegerin expression in human colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(8):2444–50.10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2884Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Del Rio M, Molina F, Bascoul-Mollevi C, Copois V, Bibeau F, Chalbos P, et al. Gene expression signature in advanced colorectal cancer patients select drugs and response for the use of leucovorin, fluorouracil, and irinotecan. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(7):773–80.10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4187Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Matsuyama T, Ishikawa T, Mogushi K, Yoshida T, Iida S, Uetake H, et al. MUC12 mRNA expression is an independent marker of prognosis in stage II and stage III colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(10):2292–9.10.1002/ijc.25256Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Kikuchi A, Ishikawa T, Mogushi K, Ishiguro M, Iida S, Mizushima H, et al. Identification of NUCKS1 as a colorectal cancer prognostic marker through integrated expression and copy number analysis. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(10):2295–302.10.1002/ijc.27911Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Loboda A, Nebozhyn MV, Watters JW, Buser CA, Shaw PM, Huang PS, et al. EMT is the dominant program in human colon cancer. BMC Med Genomics. 2011;4:9.10.1186/1755-8794-4-9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Chen DT, Hernandez JM, Shibata D, McCarthy SM, Humphries LA, Clark W, et al. Complementary strand microRNAs mediate acquisition of metastatic potential in colonic adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surgery. 2012;16(5):905–12; discussion 12–3–12.10.1007/s11605-011-1815-0Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Tripathi MK, Deane NG, Zhu J, An H, Mima S, Wang X, et al. Nuclear factor of activated T-cell activity is associated with metastatic capacity in colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74(23):6947–57.10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1592Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Marisa L, de Reyniès A, Duval A, Selves J, Gaub MP, Vescovo L, et al. Gene expression classification of colon cancer into molecular subtypes: characterization, validation, and prognostic value. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):e1001453.10.1371/journal.pmed.1001453Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Lu M, Zessin AS, Glover W, Hsu DS. Activation of the mTOR pathway by oxaliplatin in the treatment of colorectal cancer liver metastasis. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169439.10.1371/journal.pone.0169439Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Takahashi H, Ishikawa T, Ishiguro M, Okazaki S, Mogushi K, Kobayashi H, et al. Prognostic significance of Traf2- and Nck- interacting kinase (TNIK) in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:794.10.1186/s12885-015-1783-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Sayagués JM, Corchete LA, Gutiérrez ML, Sarasquete ME, Del Mar Abad M, Bengoechea O, et al. Genomic characterization of liver metastases from colorectal cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2016;7(45):72908–22.10.18632/oncotarget.12140Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Low YS, Blöcker C, McPherson JR, Tang SA, Cheng YY, Wong JYS, et al. A formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE)-based prognostic signature to predict metastasis in clinically low risk stage I/II microsatellite stable colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2017;403:13–20.10.1016/j.canlet.2017.05.031Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Conde P, Rodriguez M, van der Touw W, Jimenez A, Burns M, Miller J, et al. DC-SIGN( +) macrophages control the induction of transplantation tolerance. Immunity. 2015;42(6):1143–58.10.1016/j.immuni.2015.05.009Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102(43):15545–50.10.1073/pnas.0506580102Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson K-F, Subramanian A, Sihag S, Lehar J, et al. PGC-1α-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet. 2003;34:267–73.10.1038/ng1180Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Ren J, Niu G, Wang X, Song T, Hu Z, Ke C. Overexpression of FNDC1 in gastric cancer and its prognostic significance. J Cancer. 2018;9(24):4586–95.10.7150/jca.27672Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Specht E, Kaemmerer D, Sanger J, Wirtz RM, Schulz S, Lupp A. Comparison of immunoreactive score, HER2/neu score and H score for the immunohistochemical evaluation of somatostatin receptors in bronchopulmonary neuroendocrine neoplasms. Histopathology. 2015;67(3):368–77.10.1111/his.12662Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Hong R, Gu J, Niu G, Hu Z, Zhang X, Song T, et al. PRELP has prognostic value and regulates cell proliferation and migration in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer. 2020;11(21):6376–89.10.7150/jca.46309Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Chen G, Wang Y, Wu P, Zhou Y, Yu F, Zhu C, et al. Reversibly stabilized polycation nanoparticles for combination treatment of early-and late-stage metastatic breast cancer. ACS Nano. 2018;12(7):6620–36.10.1021/acsnano.8b01482Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Stephan T, Héctor GP, Oriol A, Irene C, Isabel P. Standardized relative quantification of immunofluorescence tissue staining. Protocol exchange (Nature Portfolio). 10.1038/protex.2012.008.Suche in Google Scholar

[54] D'errico M, de Rinaldis E, Blasi MF, Viti V, Falchetti M, Calcagnile A, et al. Genome-wide expression profile of sporadic gastric cancers with microsatellite instability. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990). 2009;45(3):461–9.10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.032Suche in Google Scholar

[55] Hughes DJ, Kunicka T, Schomburg L, Liska V, Swan N, Soucek P. Expression of selenoprotein genes and association with selenium status in colorectal adenoma and colorectal cancer. Nutrients. 2018;10:11.10.3390/nu10111812Suche in Google Scholar

[56] Pohl NM, Tong C, Fang W, Bi X, Li T, Yang W. Transcriptional regulation and biological functions of selenium-binding protein 1 in colorectal cancer in vitro and in nude mouse xenografts. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7774.10.1371/journal.pone.0007774Suche in Google Scholar

[57] Xia YJ, Ma YY, He XJ, Wang HJ, Ye ZY, Tao HQ. Suppression of selenium-binding protein 1 in gastric cancer is associated with poor survival. Hum Pathol. 2011;42(11):1620–8.10.1016/j.humpath.2011.01.008Suche in Google Scholar

[58] Rayman MP. The importance of selenium to human health. Lancet. 2000;356(9225):233–41.10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02490-9Suche in Google Scholar

[59] Hatfield DL, Tsuji PA, Carlson BA, Gladyshev VN. Selenium and selenocysteine: roles in cancer, health, and development. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39(3):112–20.10.1016/j.tibs.2013.12.007Suche in Google Scholar

[60] Rayman MP. The importance of selenium to human health. Lancet (London, Engl). 2000;356(9225):233–41.10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02490-9Suche in Google Scholar

[61] Clark LC, Combs Jr GF, Turnbull BW, Slate EH, Chalker DK, Chow J, et al. Effects of selenium supplementation for cancer prevention in patients with carcinoma of the skin. A randomized controlled trial. Nutritional Prevention of Cancer Study Group. JAMA. 1996;276(24):1957–63.10.1001/jama.276.24.1957Suche in Google Scholar

[62] Yu SY, Zhu YJ, Li WG. Protective role of selenium against hepatitis B virus and primary liver cancer in Qidong. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1997;56(1):117–24.10.1007/BF02778987Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[63] Vinceti M, Filippini T, Del Giovane C, Dennert G, Zwahlen M, Brinkman M, et al. Selenium for preventing cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1:Cd005195.10.1002/14651858.CD005195.pub4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[64] Lippman SM, Klein EA, Goodman PJ, Lucia MS, Thompson IM, Ford LG, et al. Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of prostate cancer and other cancers: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA. 2009;301(1):39–51.10.1001/jama.2008.864Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[65] Vinceti M, Vicentini M, Wise LA, Sacchettini C, Malagoli C, Ballotari P, et al. Cancer incidence following long-term consumption of drinking water with high inorganic selenium content. Sci Total Environ. 2018;635:390–6.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.04.097Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(6):1420–8.10.1172/JCI39104Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[67] Gao P-T, Ding G-Y, Yang X, Dong R-Z, Hu B, Zhu X-D, et al. Invasive potential of hepatocellular carcinoma is enhanced by loss of selenium-binding protein 1 and subsequent upregulation of CXCR4. Am J Cancer Res. 2018;8(6):1040–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[68] Goh JY, Feng M, Wang W, Oguz G, Yatim SMJM, Lee PL, et al. Chromosome 1q21.3 amplification is a trackable biomarker and actionable target for breast cancer recurrence. Nat Med. 2017;23(11):1319–30.10.1038/nm.4405Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[69] Li S, Zhang J, Qian S, Wu X, Sun L, Ling T, et al. S100A8 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis under TGF-β/USF2 axis in colorectal cancer. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2021;41(2):154–70.10.1002/cac2.12130Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[70] Wagner NB, Weide B, Gries M, Reith M, Tarnanidis K, Schuermans V, et al. Tumor microenvironment-derived S100A8/A9 is a novel prognostic biomarker for advanced melanoma patients and during immunotherapy with anti-PD-1 antibodies. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):343.10.1186/s40425-019-0828-1Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[71] Liu Y, Geng Y-H, Yang H, Yang H, Zhou Y-T, Zhang H-Q, et al. Extracellular ATP drives breast cancer cell migration and metastasis via S100A4 production by cancer cells and fibroblasts. Cancer Lett. 2018;430:430–10.10.1016/j.canlet.2018.04.043Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[72] Fang D, Zhang C, Xu P, Liu Y, Mo X, Sun Q, et al. S100A16 promotes metastasis and progression of pancreatic cancer through FGF19-mediated AKT and ERK1/2 pathways. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2021;37:555–71.10.1007/s10565-020-09574-wSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2022 Xiaotian Zhang et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- AMBRA1 attenuates the proliferation of uveal melanoma cells

- A ceRNA network mediated by LINC00475 in papillary thyroid carcinoma

- Differences in complications between hepatitis B-related cirrhosis and alcohol-related cirrhosis

- Effect of gestational diabetes mellitus on lipid profile: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Long noncoding RNA NR2F1-AS1 stimulates the tumorigenic behavior of non-small cell lung cancer cells by sponging miR-363-3p to increase SOX4

- Promising novel biomarkers and candidate small-molecule drugs for lung adenocarcinoma: Evidence from bioinformatics analysis of high-throughput data

- Plasmapheresis: Is it a potential alternative treatment for chronic urticaria?

- The biomarkers of key miRNAs and gene targets associated with extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma

- Gene signature to predict prognostic survival of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Effects of miRNA-199a-5p on cell proliferation and apoptosis of uterine leiomyoma by targeting MED12

- Does diabetes affect paraneoplastic thrombocytosis in colorectal cancer?

- Is there any effect on imprinted genes H19, PEG3, and SNRPN during AOA?

- Leptin and PCSK9 concentrations are associated with vascular endothelial cytokines in patients with stable coronary heart disease

- Pericentric inversion of chromosome 6 and male fertility problems

- Staple line reinforcement with nebulized cyanoacrylate glue in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: A propensity score-matched study

- Retrospective analysis of crescent score in clinical prognosis of IgA nephropathy

- Expression of DNM3 is associated with good outcome in colorectal cancer

- Activation of SphK2 contributes to adipocyte-induced EOC cell proliferation

- CRRT influences PICCO measurements in febrile critically ill patients

- SLCO4A1-AS1 mediates pancreatic cancer development via miR-4673/KIF21B axis

- lncRNA ACTA2-AS1 inhibits malignant phenotypes of gastric cancer cells

- circ_AKT3 knockdown suppresses cisplatin resistance in gastric cancer

- Prognostic value of nicotinamide N-methyltransferase in human cancers: Evidence from a meta-analysis and database validation

- GPC2 deficiency inhibits cell growth and metastasis in colon adenocarcinoma

- A pan-cancer analysis of the oncogenic role of Holliday junction recognition protein in human tumors

- Radiation increases COL1A1, COL3A1, and COL1A2 expression in breast cancer

- Association between preventable risk factors and metabolic syndrome

- miR-29c-5p knockdown reduces inflammation and blood–brain barrier disruption by upregulating LRP6

- Cardiac contractility modulation ameliorates myocardial metabolic remodeling in a rabbit model of chronic heart failure through activation of AMPK and PPAR-α pathway

- Quercitrin protects human bronchial epithelial cells from oxidative damage

- Smurf2 suppresses the metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma via ubiquitin degradation of Smad2

- circRNA_0001679/miR-338-3p/DUSP16 axis aggravates acute lung injury

- Sonoclot’s usefulness in prediction of cardiopulmonary arrest prognosis: A proof of concept study

- Four drug metabolism-related subgroups of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in prognosis, immune infiltration, and gene mutation

- Decreased expression of miR-195 mediated by hypermethylation promotes osteosarcoma

- LMO3 promotes proliferation and metastasis of papillary thyroid carcinoma cells by regulating LIMK1-mediated cofilin and the β-catenin pathway

- Cx43 upregulation in HUVECs under stretch via TGF-β1 and cytoskeletal network

- Evaluation of menstrual irregularities after COVID-19 vaccination: Results of the MECOVAC survey

- Histopathologic findings on removed stomach after sleeve gastrectomy. Do they influence the outcome?

- Analysis of the expression and prognostic value of MT1-MMP, β1-integrin and YAP1 in glioma

- Optimal diagnosis of the skin cancer using a hybrid deep neural network and grasshopper optimization algorithm

- miR-223-3p alleviates TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and extracellular matrix deposition by targeting SP3 in endometrial epithelial cells

- Clinical value of SIRT1 as a prognostic biomarker in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, a systematic meta-analysis

- circ_0020123 promotes cell proliferation and migration in lung adenocarcinoma via PDZD8

- miR-22-5p regulates the self-renewal of spermatogonial stem cells by targeting EZH2

- hsa-miR-340-5p inhibits epithelial–mesenchymal transition in endometriosis by targeting MAP3K2 and inactivating MAPK/ERK signaling

- circ_0085296 inhibits the biological functions of trophoblast cells to promote the progression of preeclampsia via the miR-942-5p/THBS2 network

- TCD hemodynamics findings in the subacute phase of anterior circulation stroke patients treated with mechanical thrombectomy

- Development of a risk-stratification scoring system for predicting risk of breast cancer based on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, non-alcoholic fatty pancreas disease, and uric acid

- Tollip promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression via PI3K/AKT pathway

- circ_0062491 alleviates periodontitis via the miR-142-5p/IGF1 axis

- Human amniotic fluid as a source of stem cells

- lncRNA NONRATT013819.2 promotes transforming growth factor-β1-induced myofibroblastic transition of hepatic stellate cells by miR24-3p/lox

- NORAD modulates miR-30c-5p-LDHA to protect lung endothelial cells damage

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis telemedicine management during COVID-19 outbreak

- Risk factors for adverse drug reactions associated with clopidogrel therapy

- Serum zinc associated with immunity and inflammatory markers in Covid-19

- The relationship between night shift work and breast cancer incidence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies

- LncRNA expression in idiopathic achalasia: New insight and preliminary exploration into pathogenesis

- Notoginsenoside R1 alleviates spinal cord injury through the miR-301a/KLF7 axis to activate Wnt/β-catenin pathway

- Moscatilin suppresses the inflammation from macrophages and T cells

- Zoledronate promotes ECM degradation and apoptosis via Wnt/β-catenin

- Epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related genes in coronary artery disease

- The effect evaluation of traditional vaginal surgery and transvaginal mesh surgery for severe pelvic organ prolapse: 5 years follow-up

- Repeated partial splenic artery embolization for hypersplenism improves platelet count

- Low expression of miR-27b in serum exosomes of non-small cell lung cancer facilitates its progression by affecting EGFR

- Exosomal hsa_circ_0000519 modulates the NSCLC cell growth and metastasis via miR-1258/RHOV axis

- miR-455-5p enhances 5-fluorouracil sensitivity in colorectal cancer cells by targeting PIK3R1 and DEPDC1

- The effect of tranexamic acid on the reduction of intraoperative and postoperative blood loss and thromboembolic risk in patients with hip fracture

- Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 mutation in cholangiocarcinoma impairs tumor progression by sensitizing cells to ferroptosis

- Artemisinin protects against cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury via inhibiting the NF-κB pathway

- A 16-gene signature associated with homologous recombination deficiency for prognosis prediction in patients with triple-negative breast cancer

- Lidocaine ameliorates chronic constriction injury-induced neuropathic pain through regulating M1/M2 microglia polarization

- MicroRNA 322-5p reduced neuronal inflammation via the TLR4/TRAF6/NF-κB axis in a rat epilepsy model

- miR-1273h-5p suppresses CXCL12 expression and inhibits gastric cancer cell invasion and metastasis

- Clinical characteristics of pneumonia patients of long course of illness infected with SARS-CoV-2

- circRNF20 aggravates the malignancy of retinoblastoma depending on the regulation of miR-132-3p/PAX6 axis

- Linezolid for resistant Gram-positive bacterial infections in children under 12 years: A meta-analysis

- Rack1 regulates pro-inflammatory cytokines by NF-κB in diabetic nephropathy

- Comprehensive analysis of molecular mechanism and a novel prognostic signature based on small nuclear RNA biomarkers in gastric cancer patients

- Smog and risk of maternal and fetal birth outcomes: A retrospective study in Baoding, China

- Let-7i-3p inhibits the cell cycle, proliferation, invasion, and migration of colorectal cancer cells via downregulating CCND1

- β2-Adrenergic receptor expression in subchondral bone of patients with varus knee osteoarthritis

- Possible impact of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on suicide behavior among patients in Southeast Serbia

- In vitro antimicrobial activity of ozonated oil in liposome eyedrop against multidrug-resistant bacteria

- Potential biomarkers for inflammatory response in acute lung injury

- A low serum uric acid concentration predicts a poor prognosis in adult patients with candidemia

- Antitumor activity of recombinant oncolytic vaccinia virus with human IL2

- ALKBH5 inhibits TNF-α-induced apoptosis of HUVECs through Bcl-2 pathway

- Risk prediction of cardiovascular disease using machine learning classifiers

- Value of ultrasonography parameters in diagnosing polycystic ovary syndrome

- Bioinformatics analysis reveals three key genes and four survival genes associated with youth-onset NSCLC

- Identification of autophagy-related biomarkers in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension based on bioinformatics analysis

- Protective effects of glaucocalyxin A on the airway of asthmatic mice

- Overexpression of miR-100-5p inhibits papillary thyroid cancer progression via targeting FZD8

- Bioinformatics-based analysis of SUMOylation-related genes in hepatocellular carcinoma reveals a role of upregulated SAE1 in promoting cell proliferation

- Effectiveness and clinical benefits of new anti-diabetic drugs: A real life experience

- Identification of osteoporosis based on gene biomarkers using support vector machine

- Tanshinone IIA reverses oxaliplatin resistance in colorectal cancer through microRNA-30b-5p/AVEN axis

- miR-212-5p inhibits nasopharyngeal carcinoma progression by targeting METTL3

- Association of ST-T changes with all-cause mortality among patients with peripheral T-cell lymphomas

- LINC00665/miRNAs axis-mediated collagen type XI alpha 1 correlates with immune infiltration and malignant phenotypes in lung adenocarcinoma

- The perinatal factors that influence the excretion of fecal calprotectin in premature-born children

- Effect of femoral head necrosis cystic area on femoral head collapse and stress distribution in femoral head: A clinical and finite element study

- Does the use of 3D-printed cones give a chance to postpone the use of megaprostheses in patients with large bone defects in the knee joint?

- lncRNA HAGLR modulates myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury in mice through regulating miR-133a-3p/MAPK1 axis

- Protective effect of ghrelin on intestinal I/R injury in rats

- In vivo knee kinematics of an innovative prosthesis design

- Relationship between the height of fibular head and the incidence and severity of knee osteoarthritis

- lncRNA WT1-AS attenuates hypoxia/ischemia-induced neuronal injury during cerebral ischemic stroke via miR-186-5p/XIAP axis

- Correlation of cardiac troponin T and APACHE III score with all-cause in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients with acute pulmonary embolism

- LncRNA LINC01857 reduces metastasis and angiogenesis in breast cancer cells via regulating miR-2052/CENPQ axis

- Endothelial cell-specific molecule 1 (ESM1) promoted by transcription factor SPI1 acts as an oncogene to modulate the malignant phenotype of endometrial cancer

- SELENBP1 inhibits progression of colorectal cancer by suppressing epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- Visfatin is negatively associated with coronary artery lesions in subjects with impaired fasting glucose

- Treatment and outcomes of mechanical complications of acute myocardial infarction during the Covid-19 era: A comparison with the pre-Covid-19 period. A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Neonatal stroke surveillance study protocol in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland

- Oncogenic role of TWF2 in human tumors: A pan-cancer analysis

- Mean corpuscular hemoglobin predicts the length of hospital stay independent of severity classification in patients with acute pancreatitis

- Association of gallstone and polymorphisms of UGT1A1*27 and UGT1A1*28 in patients with hepatitis B virus-related liver failure

- TGF-β1 upregulates Sar1a expression and induces procollagen-I secretion in hypertrophic scarring fibroblasts

- Antisense lncRNA PCNA-AS1 promotes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma progression through the miR-2467-3p/PCNA axis

- NK-cell dysfunction of acute myeloid leukemia in relation to the renin–angiotensin system and neurotransmitter genes

- The effect of dilution with glucose and prolonged injection time on dexamethasone-induced perineal irritation – A randomized controlled trial

- miR-146-5p restrains calcification of vascular smooth muscle cells by suppressing TRAF6

- Role of lncRNA MIAT/miR-361-3p/CCAR2 in prostate cancer cells

- lncRNA NORAD promotes lung cancer progression by competitively binding to miR-28-3p with E2F2

- Noninvasive diagnosis of AIH/PBC overlap syndrome based on prediction models

- lncRNA FAM230B is highly expressed in colorectal cancer and suppresses the maturation of miR-1182 to increase cell proliferation

- circ-LIMK1 regulates cisplatin resistance in lung adenocarcinoma by targeting miR-512-5p/HMGA1 axis

- LncRNA SNHG3 promoted cell proliferation, migration, and metastasis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma via regulating miR-151a-3p/PFN2 axis

- Risk perception and affective state on work exhaustion in obstetrics during the COVID-19 pandemic

- lncRNA-AC130710/miR-129-5p/mGluR1 axis promote migration and invasion by activating PKCα-MAPK signal pathway in melanoma

- SNRPB promotes cell cycle progression in thyroid carcinoma via inhibiting p53

- Xylooligosaccharides and aerobic training regulate metabolism and behavior in rats with streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetes

- Serpin family A member 1 is an oncogene in glioma and its translation is enhanced by NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 through RNA-binding activity

- Silencing of CPSF7 inhibits the proliferation, migration, and invasion of lung adenocarcinoma cells by blocking the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

- Ultrasound-guided lumbar plexus block versus transversus abdominis plane block for analgesia in children with hip dislocation: A double-blind, randomized trial

- Relationship of plasma MBP and 8-oxo-dG with brain damage in preterm

- Identification of a novel necroptosis-associated miRNA signature for predicting the prognosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- Delayed femoral vein ligation reduces operative time and blood loss during hip disarticulation in patients with extremity tumors

- The expression of ASAP3 and NOTCH3 and the clinicopathological characteristics of adult glioma patients

- Longitudinal analysis of factors related to Helicobacter pylori infection in Chinese adults

- HOXA10 enhances cell proliferation and suppresses apoptosis in esophageal cancer via activating p38/ERK signaling pathway

- Meta-analysis of early-life antibiotic use and allergic rhinitis

- Marital status and its correlation with age, race, and gender in prognosis of tonsil squamous cell carcinomas

- HPV16 E6E7 up-regulates KIF2A expression by activating JNK/c-Jun signal, is beneficial to migration and invasion of cervical cancer cells

- Amino acid profiles in the tissue and serum of patients with liver cancer

- Pain in critically ill COVID-19 patients: An Italian retrospective study

- Immunohistochemical distribution of Bcl-2 and p53 apoptotic markers in acetamiprid-induced nephrotoxicity

- Estradiol pretreatment in GnRH antagonist protocol for IVF/ICSI treatment

- Long non-coding RNAs LINC00689 inhibits the apoptosis of human nucleus pulposus cells via miR-3127-5p/ATG7 axis-mediated autophagy

- The relationship between oxygen therapy, drug therapy, and COVID-19 mortality

- Monitoring hypertensive disorders in pregnancy to prevent preeclampsia in pregnant women of advanced maternal age: Trial mimicking with retrospective data

- SETD1A promotes the proliferation and glycolysis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells by activating the PI3K/Akt pathway

- The role of Shunaoxin pills in the treatment of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion and its main pharmacodynamic components

- TET3 governs malignant behaviors and unfavorable prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by activating the PI3K/AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin pathway

- Associations between morphokinetic parameters of temporary-arrest embryos and the clinical prognosis in FET cycles

- Long noncoding RNA WT1-AS regulates trophoblast proliferation, migration, and invasion via the microRNA-186-5p/CADM2 axis

- The incidence of bronchiectasis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Integrated bioinformatics analysis shows integrin alpha 3 is a prognostic biomarker for pancreatic cancer

- Inhibition of miR-21 improves pulmonary vascular responses in bronchopulmonary dysplasia by targeting the DDAH1/ADMA/NO pathway

- Comparison of hospitalized patients with severe pneumonia caused by COVID-19 and influenza A (H7N9 and H1N1): A retrospective study from a designated hospital

- lncRNA ZFAS1 promotes intervertebral disc degeneration by upregulating AAK1

- Pathological characteristics of liver injury induced by N,N-dimethylformamide: From humans to animal models

- lncRNA ELFN1-AS1 enhances the progression of colon cancer by targeting miR-4270 to upregulate AURKB

- DARS-AS1 modulates cell proliferation and migration of gastric cancer cells by regulating miR-330-3p/NAT10 axis

- Dezocine inhibits cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by targeting CRABP2 in ovarian cancer

- MGST1 alleviates the oxidative stress of trophoblast cells induced by hypoxia/reoxygenation and promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by activating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway

- Bifidobacterium lactis Probio-M8 ameliorated the symptoms of type 2 diabetes mellitus mice by changing ileum FXR-CYP7A1

- circRNA DENND1B inhibits tumorigenicity of clear cell renal cell carcinoma via miR-122-5p/TIMP2 axis

- EphA3 targeted by miR-3666 contributes to melanoma malignancy via activating ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK pathways

- Pacemakers and methylprednisolone pulse therapy in immune-related myocarditis concomitant with complete heart block

- miRNA-130a-3p targets sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 to activate the microglial and astrocytes and to promote neural injury under the high glucose condition

- Review Articles

- Current management of cancer pain in Italy: Expert opinion paper

- Hearing loss and brain disorders: A review of multiple pathologies

- The rationale for using low-molecular weight heparin in the therapy of symptomatic COVID-19 patients

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and delayed onset muscle soreness in light of the impaired blink and stretch reflexes – watch out for Piezo2

- Interleukin-35 in autoimmune dermatoses: Current concepts

- Recent discoveries in microbiota dysbiosis, cholangiocytic factors, and models for studying the pathogenesis of primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Advantages of ketamine in pediatric anesthesia

- Congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Role of dentist in early diagnosis

- Migraine management: Non-pharmacological points for patients and health care professionals

- Atherogenic index of plasma and coronary artery disease: A systematic review

- Physiological and modulatory role of thioredoxins in the cellular function

- Case Reports

- Intrauterine Bakri balloon tamponade plus cervical cerclage for the prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage in late pregnancy complicated with acute aortic dissection: Case series

- A case of successful pembrolizumab monotherapy in a patient with advanced lung adenocarcinoma: Use of multiple biomarkers in combination for clinical practice

- Unusual neurological manifestations of bilateral medial medullary infarction: A case report

- Atypical symptoms of malignant hyperthermia: A rare causative mutation in the RYR1 gene

- A case report of dermatomyositis with the missed diagnosis of non-small cell lung cancer and concurrence of pulmonary tuberculosis

- A rare case of endometrial polyp complicated with uterine inversion: A case report and clinical management

- Spontaneous rupturing of splenic artery aneurysm: Another reason for fatal syncope and shock (Case report and literature review)

- Fungal infection mimicking COVID-19 infection – A case report

- Concurrent aspergillosis and cystic pulmonary metastases in a patient with tongue squamous cell carcinoma

- Paraganglioma-induced inverted takotsubo-like cardiomyopathy leading to cardiogenic shock successfully treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- Lineage switch from lymphoma to myeloid neoplasms: First case series from a single institution

- Trismus during tracheal extubation as a complication of general anaesthesia – A case report

- Simultaneous treatment of a pubovesical fistula and lymph node metastasis secondary to multimodal treatment for prostate cancer: Case report and review of the literature

- Two case reports of skin vasculitis following the COVID-19 immunization

- Ureteroiliac fistula after oncological surgery: Case report and review of the literature

- Synchronous triple primary malignant tumours in the bladder, prostate, and lung harbouring TP53 and MEK1 mutations accompanied with severe cardiovascular diseases: A case report

- Huge mucinous cystic neoplasms with adhesion to the left colon: A case report and literature review

- Commentary

- Commentary on “Clinicopathological features of programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma”

- Rapid Communication

- COVID-19 fear, post-traumatic stress, growth, and the role of resilience

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Tollip promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression via PI3K/AKT pathway”

- Erratum to “Effect of femoral head necrosis cystic area on femoral head collapse and stress distribution in femoral head: A clinical and finite element study”

- Erratum to “lncRNA NORAD promotes lung cancer progression by competitively binding to miR-28-3p with E2F2”

- Retraction

- Expression and role of ABIN1 in sepsis: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Retraction to “miR-519d downregulates LEP expression to inhibit preeclampsia development”

- Special Issue Computational Intelligence Methodologies Meets Recurrent Cancers - Part II

- Usefulness of close surveillance for rectal cancer patients after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- AMBRA1 attenuates the proliferation of uveal melanoma cells

- A ceRNA network mediated by LINC00475 in papillary thyroid carcinoma

- Differences in complications between hepatitis B-related cirrhosis and alcohol-related cirrhosis

- Effect of gestational diabetes mellitus on lipid profile: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Long noncoding RNA NR2F1-AS1 stimulates the tumorigenic behavior of non-small cell lung cancer cells by sponging miR-363-3p to increase SOX4

- Promising novel biomarkers and candidate small-molecule drugs for lung adenocarcinoma: Evidence from bioinformatics analysis of high-throughput data

- Plasmapheresis: Is it a potential alternative treatment for chronic urticaria?

- The biomarkers of key miRNAs and gene targets associated with extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma

- Gene signature to predict prognostic survival of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Effects of miRNA-199a-5p on cell proliferation and apoptosis of uterine leiomyoma by targeting MED12

- Does diabetes affect paraneoplastic thrombocytosis in colorectal cancer?

- Is there any effect on imprinted genes H19, PEG3, and SNRPN during AOA?

- Leptin and PCSK9 concentrations are associated with vascular endothelial cytokines in patients with stable coronary heart disease

- Pericentric inversion of chromosome 6 and male fertility problems

- Staple line reinforcement with nebulized cyanoacrylate glue in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: A propensity score-matched study

- Retrospective analysis of crescent score in clinical prognosis of IgA nephropathy

- Expression of DNM3 is associated with good outcome in colorectal cancer

- Activation of SphK2 contributes to adipocyte-induced EOC cell proliferation

- CRRT influences PICCO measurements in febrile critically ill patients

- SLCO4A1-AS1 mediates pancreatic cancer development via miR-4673/KIF21B axis

- lncRNA ACTA2-AS1 inhibits malignant phenotypes of gastric cancer cells

- circ_AKT3 knockdown suppresses cisplatin resistance in gastric cancer

- Prognostic value of nicotinamide N-methyltransferase in human cancers: Evidence from a meta-analysis and database validation

- GPC2 deficiency inhibits cell growth and metastasis in colon adenocarcinoma

- A pan-cancer analysis of the oncogenic role of Holliday junction recognition protein in human tumors

- Radiation increases COL1A1, COL3A1, and COL1A2 expression in breast cancer

- Association between preventable risk factors and metabolic syndrome

- miR-29c-5p knockdown reduces inflammation and blood–brain barrier disruption by upregulating LRP6

- Cardiac contractility modulation ameliorates myocardial metabolic remodeling in a rabbit model of chronic heart failure through activation of AMPK and PPAR-α pathway

- Quercitrin protects human bronchial epithelial cells from oxidative damage

- Smurf2 suppresses the metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma via ubiquitin degradation of Smad2

- circRNA_0001679/miR-338-3p/DUSP16 axis aggravates acute lung injury

- Sonoclot’s usefulness in prediction of cardiopulmonary arrest prognosis: A proof of concept study

- Four drug metabolism-related subgroups of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in prognosis, immune infiltration, and gene mutation

- Decreased expression of miR-195 mediated by hypermethylation promotes osteosarcoma

- LMO3 promotes proliferation and metastasis of papillary thyroid carcinoma cells by regulating LIMK1-mediated cofilin and the β-catenin pathway

- Cx43 upregulation in HUVECs under stretch via TGF-β1 and cytoskeletal network

- Evaluation of menstrual irregularities after COVID-19 vaccination: Results of the MECOVAC survey

- Histopathologic findings on removed stomach after sleeve gastrectomy. Do they influence the outcome?

- Analysis of the expression and prognostic value of MT1-MMP, β1-integrin and YAP1 in glioma

- Optimal diagnosis of the skin cancer using a hybrid deep neural network and grasshopper optimization algorithm

- miR-223-3p alleviates TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and extracellular matrix deposition by targeting SP3 in endometrial epithelial cells

- Clinical value of SIRT1 as a prognostic biomarker in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, a systematic meta-analysis

- circ_0020123 promotes cell proliferation and migration in lung adenocarcinoma via PDZD8

- miR-22-5p regulates the self-renewal of spermatogonial stem cells by targeting EZH2

- hsa-miR-340-5p inhibits epithelial–mesenchymal transition in endometriosis by targeting MAP3K2 and inactivating MAPK/ERK signaling

- circ_0085296 inhibits the biological functions of trophoblast cells to promote the progression of preeclampsia via the miR-942-5p/THBS2 network

- TCD hemodynamics findings in the subacute phase of anterior circulation stroke patients treated with mechanical thrombectomy

- Development of a risk-stratification scoring system for predicting risk of breast cancer based on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, non-alcoholic fatty pancreas disease, and uric acid

- Tollip promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression via PI3K/AKT pathway

- circ_0062491 alleviates periodontitis via the miR-142-5p/IGF1 axis

- Human amniotic fluid as a source of stem cells

- lncRNA NONRATT013819.2 promotes transforming growth factor-β1-induced myofibroblastic transition of hepatic stellate cells by miR24-3p/lox