Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

-

Nibedita Dey

, Thanigaivel Sundaram

and Maximilian Lackner

Abstract

Consumers now have access to synthetic natural organic nanofoods with tailored properties. These nanofoods use organic or inorganic nanostructured ingredients to enhance bioavailability, making them more effective than traditional supplements. Common materials include metals like iron, silver, titanium dioxide, magnesium, calcium, selenium, and silicates. Modifying the surface of these nanoparticles can provide unique benefits such as improved preservation, mechanical strength, moisture control, and flavor enhancement. Nanocarriers, such as polymeric, lipid, and dendrimer-based carriers, are used in food production. Common polymers include polyglycolic acid, poly (lactic acid), chitosan, and sodium alginate. Lipid carriers have a hydrophobic outer layer and a hydrophilic core, while dendrimer carriers are made from materials like polyethylene glycol and polyamidoamine. These nanocarriers can encapsulate up to 99% of active ingredients, ensuring precise delivery and stability. The nanocarriers in commercial foods are emulsions, inorganic coatings, and fiber coatings. For instance, cucumbers coated with nano emulsions show up to 99% antimicrobial effectiveness. Inorganic coatings, such as potassium sorbate, calcium caseinate, and titanium dioxide, significantly extend the shelf life of packaged foods. Lipid and protein-encapsulated nanosystems offer complete gas barrier protection. This review highlights the exclusive use of nanoparticles in food processing and packaging to enhance quality, safety, and shelf life.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Innovation in foods has been of great interest to mankind for ages. They were differentiated based on their size and structure. Several building blocks of food are naturally occurring nanoparticles. For years together they have been a part of the roots of nutrition for centuries. Nanostructures of natural origin are made up of an ordered arrangement of proteins and starch. The ever-increasing demand for nutritionally advanced foods and smart foods has driven scientists to venture into many potential nanoparticles in foods. Both the major categories of nanofoods were studied and discussed in detail. The major edible foods were discussed under the food processing section. Packing of foods did throw light into the fact the incorporation of nanomaterials did yield it to have properties like antimicrobial control, biofilm control, barrier control for gases, sensing ability for toxins, etc. Special emphasis was given to the types, fabrication, and applications of nanocarriers used in food designing and upgradation. Organic-based nanocarriers have been found to be of maximum use in food processing to date. The main applications of nanotechnology in food are emphasized in the current review. Control and enhancement of essence, appeal, biological availability, sensing ability, gas diffusion, monitoring, etc., are very much essential for sensory and customer satisfaction. Smart packaging using functional materials and sensing toxins, pathogens, and undesired substances are also discussed in the present review. The main objective of the present review is to bring a comprehensive article that focuses on the latest updates used in green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and processing. The potential safety issues and trends are also brought to light and pondered on, to still curiosity in future researchers in the field of food nanotechnology.

1.1 Food nanotechnology – an overview

Naturally, our foods contain various essential components. These components are studied and differentiated based on their size and structure. Among them, we have many naturally occurring nanoparticles. They have consumed safely for generations together all around the world. The basic composition of any food (carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids) undergoes transformation and property changes at micro to nanometre ranges [1]. Proteins in food like beta-lactoglobulin get denatured by pH, heat, or pressure to form longer fibers or aggregates. These get assembled systematically to form a gel-like matrix. This is a natural example of the formation of curd from milk. Taking this natural phenomenon as an example, reports have been published on the utilization of alpha-lactalbumin of hydrolyzed protein from milk as a potential carrier of nano grade in pharmaceuticals, supplements, and food sector [2].

When polysaccharides and proteins are mixed in a solution, they separate spontaneously into micro- and nano-phased droplets. The recrystallized starch granules lie between 10 and 20 nm range. These crystals are formed and released in response to heat and hydration. This is the science behind our flat breads. For lipids, triglycerides can be crystallized and arranged as self-assembled hierarchical layers. These will range from 10 to 100 m initially and later will lead to the formation of flocs and finally fat network [3]. Nanostructures of natural origin are made up of ordered arrangements of proteins and starch. For example, arrangement of amylopectin and amylose of starch in food-binding processes are candidates for nanomaterials. Myriad structured proteins of the cow are made in its udder. This is a very apt example of nano assembly, nano synthesis, and nano dispensing of fats. Fine milling and grinding also change the phase of foods into the nanometre range. Milk in homogenized form has droplets ranging from 100 nm in size. The three basic nanostructures of milk namely (1) fat globules, (2) whey, and (3) casein are used to make most of the dairy products we use today. These include emulsions of butter, foams of ice and whipped cream, homogenized milk, solid cheese, and jelly-like yogurt [4]. This through light that the traditional dairy industry was actually a nanotechnology industry for ages together.

Nanotechnology has opened doors for many fields to merge together and thrive toward targeted goals of overall development. Their scope in the field of functional nutrition and foods with enhanced molecules of biological origin, but quite varying from nature, has been a major jump in research and development in the food industry. This field provides new innovative tools and alternatives for scientists to reach new extremes in the area of food sciences. The use of nanosized materials in the advancement of technology is called nanotechnology [5]. They are generally below 100 nm in overall size to be recruited under the nanometer scale. Their properties flip and become unique at the nanoscale compared to their bulk form. To name a few of these changes are novel chemical and physical properties – thermodynamics, solubility, etc., high surface area, enhanced electrical conductivity, etc. [6,7]. Milk protein casein is sought to be a good nanovesicle for drug delivery and food enrichment via encapsulation [8]. Extrusion-based degradation of natural food products like dextrin can be utilized for encapsulation processes [3]. When it comes to food, nanotization leads to enhanced taste, color, and texture perception of food for the customer. To name a few, mayonnaise and ice – creams made up of low nanostructured fat are found to be healthier than the ones made up of natural ingredients. Their consistency is found to be as creamier as its full-fat natural counterpart [9]. They also provide novel protection mechanisms against potential spoilage agents. Sensing through nano sensors and packaging using nanomaterials has enabled rapid, reliable, and highly sensitive alternatives for assaying contaminations in food. The processing of foods in encapsulations of nano forms to trigger heightened bioavailability of bioactive agents in foods is also gaining momentum [10]. These aspects of nanotechnology have revolutionized the food industry [11,12]. Hence, investing in this field is of great interest among the different countries [13].

The rising demand for quality foods with advanced health benefits is pushing researchers to search for ways of incorporating these nano systems, structures, and materials in foods without disturbing their natural nutritional balance [14]. They are designed to be non-toxic and have high stability at elevated temperatures and pressures [15]. The use of nanosized materials delivers a combined package of high-quality food with advanced safety and sensing abilities along with good health benefits of the food. Several industries and laboratories are working day and night to come up with various applications, protocols, and products for direct implementation of nanotechnology in foods [16,17]. Therefore, the overall application of food nanotechnology can be divided into two main categories – (1) nanostructured agents and (2) nano sensors for food. The first category will contain domains like food packing and processing. In food processing, criteria like additives, carriers, anti-caking agents, fillers, etc., will be covered. In the packaging section, criteria like antimicrobial and mechanical durability agents will be emphasized. The second category will deal with food safety and quality assessment and agents [18].

1.2 Green composites and their properties

Green composites, made from renewable resources and biodegradable polymers like starch, chitosan, and cellulose, are eco-friendly alternatives to traditional petroleum-based composites [19,20]. They offer benefits such as lighter weight, flexibility, and reduced carbon emissions, making them carbon-neutral and compostable. However, drawbacks include lower strength, poor fire resistance, and moisture absorption, which can cause fiber swelling [21]. Reinforced with materials like clay nanoparticles or cellulose nanofibers, green composites decompose naturally through microbial action, minimizing environmental impact [22]. Despite some limitations, they are gaining popularity for their sustainability and reduce harm to the ecosystem.

Green composites typically use biodegradable polymers made from substances like chitosan, cellulose, or starch. The biodegradation depends on the polymers, microorganism type, and environmental conditions. Biodegradable polymers based on starch or synthetic polymers may be used as a useful substitute with superior qualities. Nevertheless, the ingredients in packaging materials made from synthetic starch are not entirely harmless. It is possible for harmful compounds to migrate into food products and have an impact on people. This issue is prompting research into substitute packaging materials [23]. Biodegradable films have the following qualities: they are ecological, non-poisonous, flavorless, and odorless. These films protect food products from oxidation and increase shelf life and quality without sacrificing customer acceptability in low-humidity environments by exhibiting extremely little oxygen penetrability [24]. Due to its superior barrier qualities and gas selectivity, plastic packaging not only offers protection during storage and transportation but also stability and an extended shelf life for food. However, because of their hydrophilic nature, natural biopolymers, such as those made from proteins and starch, usually have strong oxygen barriers but low moisture resistance [25]. Improved gas, moisture, and scent barrier qualities of bioplastics are needed to meet the stringent criteria of some food packaging, such as an oxygen barrier lower than 5 cc·m−2-day for items like instant coffee [26]. These barrier qualities, which guard against oxygen, water vapor, and UV light, are crucial for preserving food quality while it is being stored [27]. When it comes to safeguarding food under stressful circumstances like handling, processing, and storage, a packaging system’s mechanical qualities are essential. These mechanical qualities are mostly determined by the polymer matrix’s structure. Important parameters including elastic modulus, elongation at break, and tensile strength are utilized to evaluate the mechanical performance of the material. Since the food may contain acidic ingredients that could interact with the packaging material, chemical resistance is also essential. Knowing the food’s chemical makeup before packing is crucial for safety. Mechanical characteristics of the material can change when molecules from the food are absorbed into the biopolymer matrix. Furthermore, the packing material’s thermal characteristics, as determined by differential scanning calorimetry and thermogravimetric analysis, are significant. These thermal properties ensure that the packaging can withstand the temperatures required for storing and transporting food products safely [28,29]

The mechanical properties of green composites, such as tensile strength, elongation at break, and modulus, are influenced by the type and treatment of natural fibers and the polymer matrix. Fibers like jute or hemp can enhance the strength and stiffness of the material, making it suitable for packaging applications. The strength and flexibility of green composites largely depend on the combination of fibers and the matrix. For example, reinforcing materials with natural fibers like flax or hemp improves mechanical strength. The development of fiber-reinforced polymers also has the potential to reduce the carbon footprint [30]. In the case of sugar palm yarn/glass fiber-reinforced unsaturated polyester hybrid composites, chemical treatment of the sugar palm yarn significantly improved fiber/matrix interfacial adhesion, resulting in enhanced overall mechanical properties [31]. Green composites often have lower thermal stability than synthetic polymers, limiting their use in high-temperature food processing [19]. Some green composites, like those made from polylactic acid (PLA), provide transparency, making them ideal for food packaging where visibility is important. PLA has gained popularity as a biopolymer in recent decades due to its renewable nature, non-toxicity, wide availability, affordability, excellent mechanical properties, and versatile applications in food packaging [32].

1.3 Polymeric nanocarriers and their properties

Polymeric nanocarriers, including nanoparticles, nanofibers, and nano capsules, offer advanced solutions in food processing and packaging, such as enhancing nutrient delivery and providing active packaging functions. Hydrocolloids, such as polysaccharides, are extensively used in both food and non-food applications as crystallization inhibitors, encapsulating agents, gelling agents, solidifying agents, and stabilizers. These hydrocolloid coatings demonstrate excellent permeability to gasses and lipids, but they are less permeable to moisture, making them effective in maintaining food quality [33]. Many hydrocolloid polymers also exhibit remarkable mechanical properties, which are advantageous for protecting delicate food items. Among these, protein-based polymeric foods are particularly intriguing due to their multifunctionality. Polymeric nanocarriers, such as those based on chitosan or PLA nanoparticles, are used to encapsulate bioactive compounds, flavors, or preservatives. These nanocarriers enable controlled release in response to environmental triggers such as pH, temperature, or enzymatic action, which helps to extend food freshness and improve quality [34]. Food systems typically contain complex mixtures of polypeptides and polysaccharides, whose structures vary based on chain length, chemical and physical properties, and molecular aggregation. Polymeric foods derived from plants, animals, and microorganisms composed of peptides, polysaccharides, and proteins are key contributors to the structure, function, and shelf life of food products [35]. The performance of polymeric food coatings depends on several factors, including their color, mechanical strength, and barrier properties, all of which are influenced by the preparation method. For example, coatings made with modified (oxidized) starch exhibit superior mechanical properties compared to those made with unmodified starch [36]. Nanocarriers can also be chemically modified to improve compatibility with food ingredients or packaging materials. For instance, surface modifications using surfactants or coupling agents can enhance the dispersion of nanoparticles within the polymer matrix, improving the barrier properties of the packaging. These advances in polymer nanocarriers hold great promise in food processing, contributing to better preservation and protection while extending shelf life [37].

Nanomaterials differ from bulk materials in their unique properties and behaviors, with their diameters spanning from 1 to 100 nm [38]. More research is being done on their multifaceted functions, especially in antibacterial and antioxidant applications. Numerous sectors, including automotive, aerospace, electronics, packaging, and biomedical, use these materials [39]. Because of their many uses, nanomaterials are becoming more and more in demand in the packaging sector. Usually, smaller than 100 nm in size, polymeric nanocarriers take use of their tiny size and high surface-to-volume ratio to improve their interaction with food matrices. By doing this, it becomes easier to integrate encapsulated active components like antioxidants and antimicrobials into food packaging materials and guarantees that food products are effectively protected and preserved. It also improves the transport efficiency of these compounds [40]. Foods’ physical properties, such as liquid or solid state, affect how well antimicrobial agents are absorbed and diffused in food products, which in turn affects the activities of antimicrobials [41]. Polymeric nanocarriers often exhibit enhanced thermal stability, making them suitable for processing at higher temperatures without degradation. This is critical in food packaging applications, where heat treatments are involved (e.g., during sterilization or pasteurization). The incorporation of nanocarriers into biopolymer matrices can significantly improve the mechanical properties of the packaging material, such as toughness, elasticity, and resistance to breakage. Nanocarriers act as reinforcement fillers, improving the strength of biopolymers like PLA or starch-based materials, which are otherwise brittle.

1.4 Nanostructure materials in the food sector

They are the first category of nanotechnological application in the food industry. They offer new opportunities for processing edible goods [42]. Unique and innovative structures are created and designed using different functional nanostructures. They form the building blocks of such marvelous food varieties. Weiss and his team in 2006 reported that nanostructures in the form of fibers, emulsions, particles, and liposomes have potential applications in food building, processing, storing, and packaging [43]. Materials of nano origin administered in foods basically fall into three sections: (1) organic, (2) inorganic, and (3) surface functionalized compounds [44].

1.4.1 Organic engineered nanostructured food materials

Many substances used in this section are of natural origin. They are engineered to harbor structures and features of their choice in foods. They have specialized characteristics like increased bioavailability, enhanced antioxidant property, and increased uptake in the gut compared to their bulk counterparts. Some of the major candidates in this section are food additives and supplements incorporated into foods to enhance their nutritional value [45]. To name a few examples of the former we have ascorbic acid, citric acid, and benzoic acid. For the latter vitamins E, vitamin A, beta carotenes, isoflavones, omega-3 fatty acids, lutein, and coenzyme-10 are some examples [46]. Evidence for engineered nanomaterial of organic origin is manipulated lycopene. The synthetic carotenoid of tomato is manufactured in nanosized from and is equivalent to its natural bulk counterpart in terms of functionality [47]. Materials whose sources are from plants like fats, proteins, nutraceuticals, and sugars are all part of organic nanomaterials used in foods.

1.4.2 Inorganic engineered nanostructured food materials

Inorganic materials in nanoforms are mostly transition metals. These metals range from iron, silver, and titanium dioxide to earth metals (magnesium and calcium) to non- metals (selenium, silicates). Packaging is the major sector where inorganic nanostructures are used in foods. Silver in its nanoform is in great demand in the consumer market. They cover all areas in food processing and packing (antimicrobial agent, supplement, ant odorant, food contact surfaces, etc.). Nanosilica is an amorphous nanomaterial known for food contact and packing utility applications. Selenium in its nanoform is marketed in green tea for its proclaimed benefits to health [48]. Patents have been filed on the potential food applications of nano calcium. Along with magnesium and iron in nanotized form are used as supplements in foods. Nano iron is also used to clean contaminated water (killing pathogens and breakdown organic matter). A specially engineered salt called nano salt is designed for customers with hypertension to cut down their salt consumption in foods [49]. Their nano size gives them a large surface area that spreads in food even in the smallest of quantities [50]. Milk tasting like cola and fat-reduced mayonnaise is still on the way to the commercial market. Nano sensors in food products act as barcodes that can be detected electronically [51].

1.4.3 Surface-functionalized nanostructured food materials

These structures add some special functionalities to the food. These can be preservation properties, mechanical strength, barrier for gas diffusion, moisture control, flavor control, etc. They have a tendency to have a greater affinity toward food matrices and food components [52]. Therefore, they are restricted from moving out of their packing or the GI tract. Bentonite is engineered to form nano-clay from volcanic rocks. They are bound to polymers with their nano-scaled layers to form a gas barrier packing for foods [53].

2 Nanocarrier

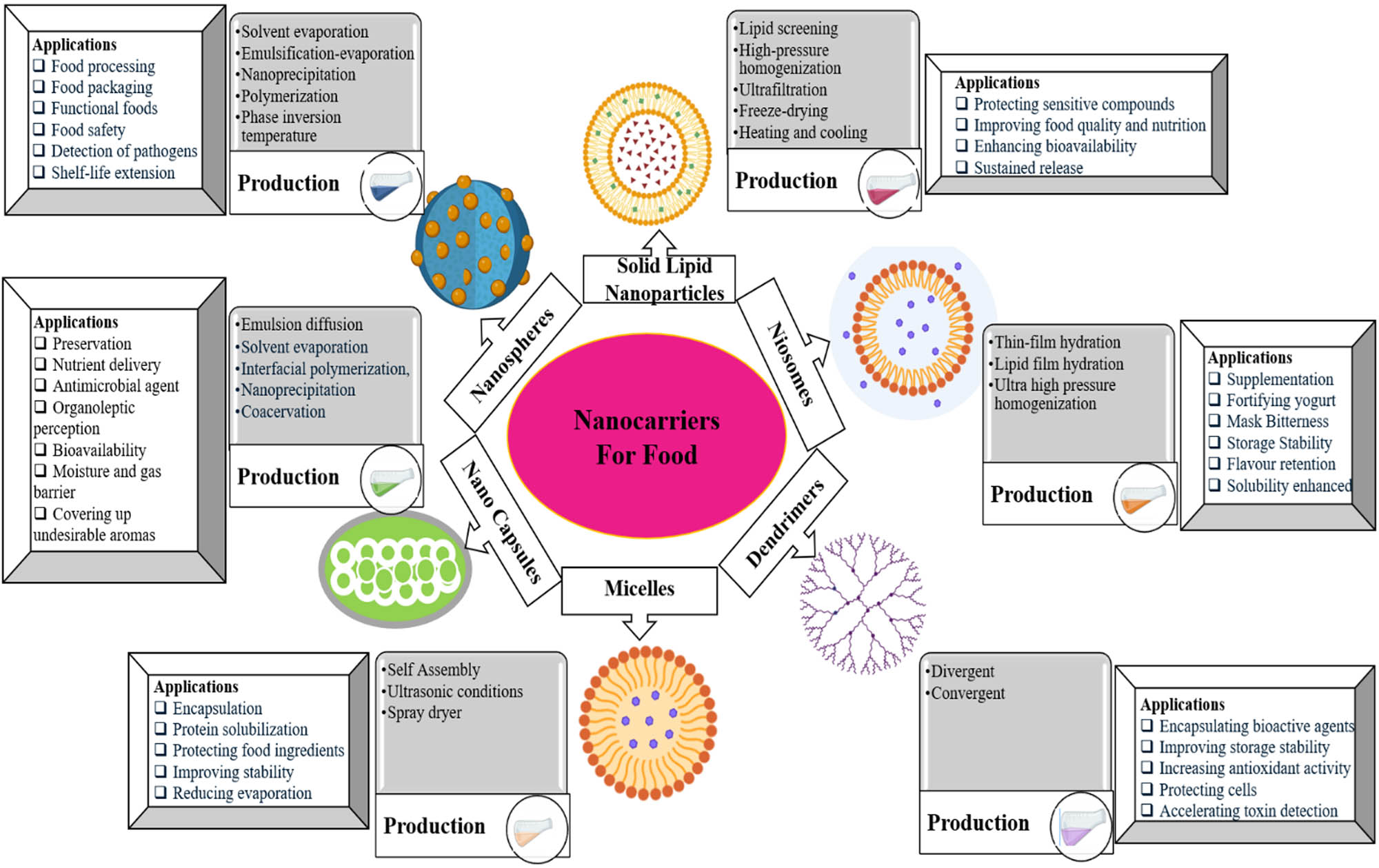

They belong to the first category of nanostructured materials used in foods. They are classified as organic and inorganic or a combination of both [7]. Liposomes, polymers, nano emulsions, micelles, dendrimers, carbon nanotubes, fullerenes, etc., are components of organic-based nanocarriers. Quantum dots and metallic structures are comprised of inorganic-based nanocarriers [14]. The major types of materials of nano origin and different nano carriers that are used in the food sector have been depicted in Figure 1.

Schematic representation of different types of nanocarriers used in foods.

2.1 Polymers

Biodegradable synthetic and natural polymers are utilized to make specialized carriers of nano range. Biocompatibility is also an essential aspect that in kept in mind while designing these carriers [15]. Polyglycolic acid, poly(ε-caprolactone), poly(amino acid), poly(lactic acid), polymethyl methacrylate, and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) are few synthetic resins used for making polymeric nanocarriers. Chitosan, sodium alginate, fibrin, and agarose are few natural polymers used for the same [13]. Polymeric nanoparticles have special features like sustained release and enhanced flexibility to apt integration with food materials in the form of supplements and growth factors [51].

2.2 Liposomes

These are concentric double layers of lipids. Nanocarriers will have a core of aqueous nature enclosed by functionalized surfactants. These can be synthetic or natural phospholipid layers. Liposomal nanocarriers are categorized based on the type of vesicles they contain. These ca be unilamellar vesicles, multilamellar vesicles, and oligolamellar vesicles [52]. They are abbreviated as ULV, MLV, and OLV, respectively. Unilamellar vesicles based on size are divided into four subclasses – nearly 20 nm in diameter (small unilamellar vesicles), 20–100 nm in diameter (medium unilamellar vesicles), larger than 100 nm (large unilamellar vesicles), and larger than 1,000 nm in diameter (giant unilamellar vesicles). Virosomes, archaeosomes, immunoliposomes, and stealth liposomes are some carriers that naturally have stable and soluble biocompatible cores [53].

2.3 Dendrimers

They are macromolecular nanocarriers that are monodispersed in a medium. They consist of an inner core center and branched dendrites outside. They can be constructed from convergent monomers or divergent monomers via polymerization [54]. Their number of branching and repeating units determines the size and shape of the dendrimer. Polyethylene glycol, polyamidoamine, polyethyleneimine, chitin, melamine, polypropyleneimine, and poly l-glutamic acid are some fundamental units used in dendrimer formation [55]. Targeted delivery is feasible using the core of the dendrimer for loading many functional and bioactive agents [56].

2.4 Carbon nanocarriers

Graphene sheets can be arranged in a cylindrical structure for nanotubes or capped structures on both sides as bucky balls. Based on the walls of the carbon structures, they can be classified as single-walled nanotubes and multiwalled nanotubes [57]. Based on the functionalization process and storage conditions, carbon-based nanocarriers can be divided into surface-grafted nanocarriers, ligand-attached nanocarriers, and solvent-dispersed nanocarriers [58]. The geometrical arrangement of carbon atoms to manifest hexagonal and pentagonal sides is also a type of carbon nanocarrier called fullerenes. Bioactive compounds can be loaded in the core and used for sustained and targeted delivery in foods [59].

2.5 Hydrogel nanocarriers

They are three-dimensional networks of polymers with hydrophilic groups on their surfaces. They absorb a large quantity of biological fluids or water. These groups can be –SO3H, −CONH, −OH, CONH2, etc. [60]. The bonds that hold these polymers intact are a combination of van der Waals interactions, covalent bonds, dipole–dipole interactions, physical entanglements, and hydrogen bonds [61]. The polymers also make their own crosslinked networks. Some basic polymers discussed in the above sections form good hydrogel nanocarriers too. They get influenced by temperature, pH, electric field, and light’s intensity [62].

2.6 Quantum dots

They are examples of inorganic nanocarriers. They are crystals in the nano range of semiconductor materials. They have sizes ranging from 2 to 10 nm. They are fabricated in such a way that they emit light in all ranges (from UV to IR) [63]. The emitted intensity is propositional to the subcellular responses. They are biocompatible and stable and harbor surfaces to functionalize with various biomolecules [63,64].

2.7 Nano emulsions

These are tiny drop-like structures with various size ranges. Generally, they are approximately 100 nm. They are classified into two major categories based on the spatial configuration between the two major building blocks – water and oil. Basically, it comprises oil suspended with an aqueous phase [65]. This is referred to as oil in the water micellar system. The reverse of this is termed as water in an oil micellar system. Nanoemulsions have a unique property of light scattering in the weakest order [65]. Hence, they are incorporated in light foods for fortification like soft drinks, whitening cosmetics, soups, waters, and sauces [66].

3 Preparation methods for nanocarriers

There are several methods and approaches to fabricate a nanocarrier. New techniques are emerging every day for the food-based application and generation of nanocarriers. The pioneer technique is emulsification [67]. Each carrier has its own set of specifications incorporated in the fabrication process to yield its characteristic traits. Different methods of preparation of nanocarriers are represented in Figure 2.

Schematic representation of different methods of preparation of nanocarriers.

3.1 Conventional methods

3.1.1 Homogenization

Lipid-based carriers are basically synthesized using high-pressure homogenization. Few examples are solid lipid-based nanoparticles, emulsions, etc. The high-pressure atmosphere creates shear stress of high magnitude. This leads to the breaking of particles to the nano range [68]. The atmosphere in which the homogenization takes place divides the whole process into two as hot and cold. The hot homogenization process gives rise to low particle sizes as the viscosity decreases with an increase in temperature [69,70]. The main drawback associated with this technique is the possibility of degradation of the core food component that is carried in these carriers. Cold homogenization is the remedy for the former disadvantage [71].

3.1.2 Diffusion method

Polymer and lipid-based carriers are nowadays made using this method. The oil medium will harbor the polymer in a solvent of organic nature. Stabilizers are added and mixed well. Water will initiate the diffusion of the solvent and form nanocarriers. Later, the solvent is removed. The complexity of the nanocarriers can be enhanced by double emulsification processes [66]. A minute amount of water is added to an organic solvent that is immiscible in water. The phospholipids are dissolved and further large amount of aqueous medium is incorporated to create a water in oil in water-type medium [72]. A monolayer of fatty acids is formed around the organic matter, resulting in an aqueous core. The ability of entrapment can be increased by the removal of solvent afterward [73,74].

3.1.3 Injection method

The solvent used for this method generally uses two solvents, namely ethanol or ether. Mixtures of ether – methanol and diethyl ether – are also used to dissolve the constituent lipids [75]. The ether-based lipid solution is added to the water medium. This leads to the formation of nanocarriers [76,77]. As the speed is increased, LUVs can be fabricated. Ether injection techniques allow the removal of solvent from the end product. This helps in concentrating products and extending running time. Even the entrapment efficiency is enhanced. The final products are heterogeneous in nature and need high-temperature working conditions [78]. The sizes range from 700 to 200 nm. For the ethanol-based injection technique, concentration can be enhanced for the core in the water phase by doing multiple incorporations of formative lipids [79]. It forms MLVs and the process is also simple and quick [80]. The disadvantage is the same as the former technique which is the formation of heterogenous end products. The sizes vary from 30 to 110 nm. The removal of ethanol is a herculean task followed by liposomes generated in lower concentrations. This removal is very crucial when liposomes are created with a motive for microbial treatment and cell culture-based applications [81].

3.1.4 Evaporation method (reverse phase)

The main principle behind this is the formation of micelles in the reversed order. The central core is an aqueous medium and the lipid surrounds the core in a solvent of organic nature [82]. An organic solvent is sonicated after the addition of minute quantities of aqueous and lipids. This produces micelles in the inverted order. A rotary evaporator is employed on the crude mixture to produce a gel-like matrix [83]. Further removal of the solvent leads to the gel collapsing and vesicles get suspended [84,85]. The major drawback of this method is the fact that the material to be incorporated is in contact with the external organic solvent. Hence, fragile and degradable materials are at great risk of breaking down during the process of incorporation in the nanocarrier. But the potential encapsulation efficiency is 80% [86].

3.2 Emerging technologies

3.2.1 Channel method (microfluids)

Polydimethylsiloxane wafers are usually employed in the fabrication of the channel. Two wafers are attached together and one side of the wafer is engraved [81]. The engraving width is kept to be around 1,000 μm max. One outlet and two inlet lines are carved and connected to the microfluid channel [87]. The central point is the two inlet points merging at the center. The aqueous medium is incorporated from the outer inlet and the lipid is from the central channel. This creates a difference in the shear forces due to the different liquid interfaces and hence leads to the fabrication of the liposome [88]. The perks of this technique are the ease of operation, vesicle size control, and mono-layer dispersion. A continuous system of fabrication through micro channels is yet to be devised.

3.2.2 Fluid method (supercritical)

The drawbacks of the conventional method are tackled at times using gas or liquids. These are called supercritical fluids. A certain parameter gives these fluids or gases unique properties that aid in nanocarrier formation [85]. For example, carbon dioxide and water are used above critical thermodynamic points of pressure (250 bar) and temperature (60°C). Based on the property opted by the supercritical fluid, they are classified as antisolvent precipitation technique and rapid expansion method [86,89]. The main highlights of this method are better liposome particle design and environmental friendliness. Scalability is an issue that needs to be addressed as it may lead to varying size ranges for the end product [90].

3.2.3 Self-assembly method

It is a process where disordered structures arrange and regulate themselves in an ordered fashion [91]. These occur without a prior external force. The formation of micelles itself is a self-assembly. It has not been used to its full potential yet. Encoding them will give way to various properties never ventured [92].

4 Current trends

Attributing to the large surface-to-volume ratio of nanoparticles, the food quality, physical and chemical features, and biological potency can be altered with good efficiency. Gold, silver, titanium, zinc oxides, and carbon nanomaterials of various dimensions are structures used in food storage applications [93]. The main issue that is to be tackled in the current day scenario is the wastage of food. This leads to a major loss for the company and a shortage of supply for the customers. The wastage of raw resources and recycling of the same for environmental cleanliness is an overall loss for the world economy. 1.3 billion tons of food wastages have been recorded every year all around the world by the special division of food and agriculture organizations under the United Nations. These losses are due to poor harvest approaches, market wastages, transport delay, and consumer wastages [88]. The ability to fortify the quality of foods should go hand in hand with food wastage management initiatives. A combined effort will help the present generation to solve the emerging crisis situations related to food wastage and environmental remediation. As previously discussed in the above sections, nanotechnology has been successfully utilized in the food sector for production, processing, preservation, distribution, and sensing [88]. The plastic physical barriers imposed and proposed by these novel functional nanomaterials provide functional fortification to the food component simultaneously. This enhances shelf life and overall quality and productivity. Sensing is also feasible for various toxins and pathogens via changes in color and hue [94]. These intelligent and novel systems have incorporated a greater assessment in the food industry through their smart reporting and controlling of the foods with the help of localized sensing. The nutraceutical value of the food is also enhanced to a good level. Nanotubes have been reported as potent cellular damaging agents for Escherichia coli. The main mechanism is the direct puncturing of the cell wall [94]. Biosensors made up of nanomaterials have been reported previously for their proficiency in sensing pathogenic that are carcinogenic in nature. Ideally, post-harvest-based techniques are preferred and researched on now a day. It aids in the enhancement of texture, flavor, consistency, and availability for assimilation [95]. Many confectionaries use coated with nano edible coatings for their anti-bacterial properties [96]. Innovative filters impregnated with nanomaterials have been devised to remove color from extracts of beetroot. They enable the retention of pigments and flavors for red wine. Similarly, milk is filtered out of its lactose ingredient and altered to be consumer friendly for people who are lactose intolerant. The same principle can be employed for the removal of bacterial pathogens from beverages like milk or water without any heat treatments. Beers are also filtered and refined using nano sieves [97,98].

Healthier foods are feasible at much more economical costs thanks to nanotechnology in the food industry. Low-salt, low-sugar, and low-fat products have their own place in the world share market due to the ever increase in lifestyle disorders among people. Certain nanomaterials are accepted to such a level that they are used in bulk measures in factories as additives in foods. E551 and E171 made of silicon dioxide and titanium dioxide are very well-known additives used in bulk form [99]. Poly-d,l-lactide in bio-degenerative encapsulated form is used to enhance the shelf life of various vegetables and fruits, especially tomatoes [100]. Neosino, a supplement of green tea in the nano range, is commercialized effectively today because of the nanotechnology revolution in the food market. Along with the former Aquanova, an active ingredient of canola oil is used to increase the biological availability and absorption of most of the fat-soluble vitamins through pills. Omega fatty acids, beta carotene, nutraceuticals, and medicinal drugs in carriers of nano range (Nutra lease) have also been successfully commercialized in recent times. Many Western countries have their very own nano-fortified foods in the form of teas, fruit juices, oats drinks, and supplements composed of tuna oil with breads and slim shakes made up of nanoceuticals [101,102].

When it comes to packaging the ultimate main to avoid spoilage and contamination to the maximum. Muscle and meat-based products are packaged with utmost care with the latest smart packing systems to ensure better shelf life, good tenderness of products due to enzymatic activity, retain the hue of the protein meat produced, and reduce overall weight loss [80]. The unique flavors and colors generated through these nanosystems in accordance with the foods help the consumers to analyze the condition of the food products based on the presence of contamination, toxins, pathogens, or pesticides [103,104]. Colloids of starch are often used as carriers for potential antimicrobials for packaging materials [105]. These packaging materials can harbor and transport antioxidants, flavors, enzymes, anti-browning materials, etc., for the preservation of foods post-opening of the sealed package [106]. Many nanoparticles (magnesium dioxide, silicon dioxide, titanium dioxide, gold, silver) used in packaging provide high thermal resistance, mechanical stability, and low mass along with anti-pathogenic properties. They also are capable of generating reactive oxygen species which is found to be detrimental for most of the pathogens. They also provide a suitable barrier against oxygen, carbon dioxide, water vapors, ultraviolet radiations, chemical fumes, etc., and fire resistance can be attained for smart packing materials by filling their matrix with composites in nano sizes. Silicate nanoplatelets, cellulose-based nanofibers, chitin- or chitosan-based materials, carbon nanotubes, clay, graphene, and many more components can be used as fillers for active packaging in foods [107]. The features of the above-mentioned materials get further enhanced due to the uniquely high surface-to-volume ratio attained in the nano dimension [108]. Silver zeolite is specialized used in the antimicrobial packaging of foods. The silver nanoparticle is responsible for the ROS activity and the ceramic used in combination with silver zeolite is in charge of the disinfection mechanism [109]. Nanocarbon is of great use in the elimination of unpleasant odors and flavors, especially carbon dioxide. Many bottles and packaging materials are fabricated from bentonite (nanoclay) as it has advanced gas barrier features, thereby aiding in beverage stabilization and extending shelf life [110]. Nanocor, a US-based company, developed a nanocomposite harboring nanocrystals in beer bottles. These special bottles have very limited carbon dioxide loss and the inflow of oxygen is also very low [111]. Similarly, ethylene-vinyl alcohol incorporated with clay and PLA forms a nanocomposite with good oxygen barrier control for foods [112]. The addition of nanofillers provides better degradation properties to the polymer than when compared to its parent polymer. Hence making the nano system to be environment friendly [110].

4.1 Trends in food processing

There are many companies today in the market that have revolutionized the nano-based food supplements and products in the market. A self-assembled nanostructure made up of Leaseanola essential oil is commercialized by Israel to reduce cholesterol absorption in the gut into the systemic circulation. It is a form of liquid self-assembled structure (NSSL) [113,114]. Shenzhen in China is a major trader for nano tea as a beverage. A team of researchers from United States have come up with micelles incorporated with lycopene. They have been used in fortified juices and beverages. The size of the micelles ranges to a max of 100 nm in dimension (diameter). RBC Life Sciences in the United States has successfully launched a flavor-based diet shake and health drink for people who are calorie conscious. Nanoscale chocolate and vanilla flavors are converted into low-calorie slim shakes of preferred choice [115]. Even baby products are introduced to these remarkable nanosystems for better nutritional support to infants. Los Angeles-based toddler Health Company has launched an oats drink as a beverage for babies to provide enhanced essential nutritional needs. This beverage has 33% more micro and macro nutrients which will aid in the overall development of the infant [116]. In Australia, a bread company has successfully incorporated nanocapsules of essential oils into confectionary items to elevate their nutritive values. Omega 3 FA is one of the main essential oils that they majorly use in their products. A supplement company in the United States has bagged the attention of pharmaceutical as they have formulated nanodroplets that can be loaded with vitamin B-12 with great efficiency [117]. Kimchi has been tailored with nanosized bacterial species to have a dual function of fermentation as well as deal with the colitis of consumers. Lactobacillus plantarum has been nanosized and substituted with traditional probiotics used in kimchi. The nano size gives it a unique feature of being anticolitic [118]. German-based Aquanova has fabricated nano micelles that have special features to improve the solubility of various active agents like omega fatty acids, vitamins, β-carotenes, etc. [119]. Oats-based nutritional drinks with a variety of flavors are formulated in combination with iron nanoparticles. The nanoparticles increase the biological availability and reactivity of the overall health drink with the body. The size ranges to an approximate value of 300 nm [120]. Cutting boards are incorporated with nanosized silver to provide good antimicrobial features to the food in contact with the board [121]. Baby feeding bottles are lined with nano silver for better storage conditions of infant formulas. These bottles are in great demand in South Korea. A special type of nano colloid is utilized to reduce the surface tension of portable drinking water. It also enhances solvent properties and neutralizes free radicals. It is composed of hydracel and silicate minerals [122].

Solgar, a US-based product is a nano nutrient of the CoQ-10 enzyme. It increases the absorption of lipids in the gut. The size of the nano food product is around 30 nm in size. Clusters in the nano range are devised to make a yummy alternative for a low-calorie diet. The flavors are boosted using nanoclusters of cocoa to provide chocolate or coffee essence. The main nanocluster consists of ingredients like spirulina and artichoke. Spirulina provides the protein base for nourishment and muscle mass [123]. Another type of nutrient derived from soya beans is nanochelated to form carrier systems and vehicles for various active nutrients. Their carrier matrix is composed of 50-nm-sized phosphatidylserine base. Even antioxidants can be delivered with sustained release features. Lypo-Spheric is a well-known vitamin C health booster supplement that is used by consumers all around the United States for potential health applications [124]. Hawaii has its very own fortified juice of Jambu that is loaded with daily essential vitamins and minerals. Silver along with 22 rich minerals is supplied to the consumer via this health drink [125]. For patients with acidity and ulcer issues, Aquanova has brought to the market SoluE, a nano supplement with vitamin E. It soothes the stomach and prevents an acidic environment for the mucosal layer of the gut. Appetite can be stimulated by dispersed nanocrystals in association with micronized components. Ceramic products of the nano range have been used to inhibit the breakdown and degradation of oils. They are known by the commercial name Oil Fresh [126].

4.2 Trends in food packaging

Silicon dioxide is a very bright candidate in terms of food drying, hygroscopic, preservation, coloring, anti-caking, and packaging [127]. Titanium dioxide is used along with dairy products like cheese, butter, and milk as a whitening agent. They are also used in food packaging and preservation. Zinc oxide is utilized in packaging materials because of their unique property to inhibit the flow of air, especially oxygen, hence delaying spoilage of products [128]. Silver nanoparticles in smart packaging aid in the antibacterial protection of the foods and eliminate the chemicals produced by ripened fruits and vegetables, hence preserving them for longer hours [129]. For fried food preservation, nanoparticles of inorganic ceramics are opted for extensively [130]. Polymers like chitosan are used to preserve fresh fruits like strawberries and mandarin. Food contaminants and adulterants are efficiently detected through nanoplate-shaped graphene composites [131]. Water packaging is made safe and secure by cellulose nanocrystals lining into packaging bottles. Magnetic nanomaterials are used for monitoring pathogens in foods as they have large surface areas [132]. For foods that require quality inspection and vacuum-sealed packaging, carbon nanotubes are employed with regard to their thermal, electrical, mechanical, and optical properties. The strength of packaging materials along with barrier properties were enhanced by including clay-polymer composites in them. The type of material opted in the packaging for foods will determine the oxidations that it would hinder, the amount of moisture bypassed through, control on respiration rate, volatile fumes managed over time, and the impact on the flavor of the product as a whole [133]. Essential oils of garlic were used in combination with PEG for the packaging of goods. Their unique trait aided in prohibiting pests that feed on foods while stored. Ɛ-Polylysine with nanoparticles of phyto glycogen octenyl has been shown to increase the shelf life of various fresh and synthetic produce [134]. Glycerine-based nano micelle in packaging identifies vegetable and fruit pesticide residues as well as dirt and oil contaminants from cutlery.

Overwraps can be used as chilled storage systems for many foods. However, the duration should be kept short along with modified atmospheric conditions. Vacuum can be used for sealing and packaging with a 100% carbon dioxide flushing system. If the duration of refrigeration needs to be made longer bulk flushing of gas can be employed. Many simple polymers like polypropylene and polyethylene of lower density are also used in packaging foods even if they are not incorporated with advanced nano systems. They are known to be hydrophobic and inert in nature with minimum surface energy. Food spoilage can be avoided on the basis of modifications of the inserted nanosystems both functionally and chemically. Special and intensive care should be taken for meat products. They have various parameters that get altered like aroma, hue, dehydration, and oxidation leading to changes in texture [135]. Modified atmospheric conditions are a key aspect that needs to be considered during meat handling and storage. Very cold conditions are always favored by protein producers to sustain their quality.

A unique formulation of non-inert gases is employed on the meat product to replace the surrounding air and sealed well for transportation and storage in deep freezers. The commonly used gases in MAP are oxygen and carbon dioxide. Their profiles are varied based on criteria like product type, packaging material used, size and dimension of the product, respiration rates involved with the ingredients of the products, the integrity of the package, and the conditions for storage [136]. The German-based chemical company has launched nano-dispersed clay in plastic storage materials. They have heightened gas barrier features. Even moisture is controlled for maintaining the freshness of the meat. Several patents are filed all around the world in regard to nano silver and nano clay for innovative food packaging fillers [137]. Carbon nanotubes and allyl isothiocyanate are known to regulate many metabolisms associated with cooked products, especially chicken. It also aids in the depletion of the pathogenic population and any change in the aesthetic appeal of the cooked chicken for up to 40 days. Figure 3 and Table 1 summarize the trends followed incurred by nanosystems in the food industry [138].

Schematic representation of different trends in food processing and packaging by nanosystems.

Different nanosystems used in the food Industry

| Nanosystems | Components | Properties | Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Films | Lipids, proteins, and polysaccharides | Oxygen barrier, gas diffusion | Smart packaging (coatings) | [143,144] |

| Zinc | Multifunctional nanoparticles | Antimicrobial | Food additives and fortification agents (Coatings) | [141,145] |

| Nano-SiO2x | Nano-SiO2 and PVA | Thickening agent | CODEX food additives (coatings) | [141,146] |

| Nanoclay | Silicates | Enhancing the mechanical attributes | Reinforcing materials (coatings) | [147,148] |

| Nanotubes | Milk protein, Polymers, nanotubes | Targeted delivery | Controlled release (coatings) | [142,149] |

| Nano fiber | Enzymes, carrot starch fibers, gelatin of fish, polymers | Modified properties mechanical stiffness | Transport and carry numerous active ingredients (coatings) | [142,150] |

| Nanoemulsions | Carvacrol chitosan cucumber, cinnamaldehyde pectin, garlic essential oil with gelatin, α-tocopherol, lemon grass on fresh fruits like apples | Antimicrobial properties | Delivery vehicle (carriers) coatings | [140,151] |

| Polymers | Essential oils, cellulose, chitosan, gelatin, Tragacanth | Antioxidant, biodegradable, non-toxic, biologically compatible | Shelf-life extender, spray-coated films, carriers | [152,153] |

| Solid lipid nanoparticles | Lipid carriers, flavonoids, carotenoids, phytosterols, polyphenols | Antioxidants, lipophilic, accelerate the creaming effect | Nutraceuticals, coating for groceries | [154,155] |

| Beverage coatings | Krill oil, NLC coatings, Rutin, coco butter NLC with olive oil and cardamom oil, silver nanoparticles | Better stability, transport, mechanical, thermal, and optical features, rarely interfere with the sensory trait | Dietary supplement, coatings for milk-based beverages and juices | [156,157] |

| Inorganic coatings | Montmorillonite, potassium sorbate, calcium caseinate, titanium dioxide, silver nanoparticles | Antimicrobial activity | Increase the longevity of foods | [139,158] |

From the current review, it can be suggested that the most common forms of nanocarriers for commercial foods are emulsions, inorganic, and fiber coatings. Cucumbers with nanoemulsions have antimicrobial properties up to 99% [136]. To enhance the shelf life of packed foods inorganic coatings of potassium sorbate, calcium caseinate, titanium dioxide, and silver nanoparticles have been reported to provide 100% efficiency [139]. Lipid- and protein-encapsulated nanosystems have manifested 100% gas barrier diffusion [140]. Silicon dioxide is a major component of CODEX additive with a 33% thickening property [141]. Milk proteins and nanotubes have a controlled release characteristics of 88%. Nanofiber coatings on carrots and enzymes have been reported 90% transport agents [142].

4.3 Safety and toxicity assessments

Nanotechnology in food-contact materials, particularly in packaging and coatings, has shown great potential for enhancing food safety and shelf life. However, it raises concerns regarding safety and toxicity, as nanoparticles may migrate from packaging into food and cause potential health risks [159]. The two primary safety issues with employing nanoparticles are allergies and heavy metal leakage. Currently, food items are using nanoparticles more quickly than intended and without the required understanding or laws, endangering both human health and the environment [19]. The similarities between nanoparticles (NPs) and nanostructures, namely their enormous surface area, high reactivity, and nanoscale, could be harmful to human health as well as the health of other living things. Although the usage of nanostructures in food may not directly affect human health, some inevitable side effects may result from their nanoscale properties. The toxicity mechanisms generated by nanoparticles, or NPs, have been well investigated [143]. Nano-entities have the potential to disrupt a variety of cellular pathways and functional processes that change the intracellular milieu which may result in excessive exposure to nanomaterials. This can have unanticipated effects on the overall functionality of the cellular system, fidelity of cell division, and DNA replication. DNA damage has been linked to cellular exposure to some nanomaterials, resulting in genome rearrangements, single- and double-stranded breaks, as well as inter/intra-strand breaks [160]. One key concern is the migration of nanoparticles into food. Studies have demonstrated that under certain conditions, nanoparticles can leach from packaging into the food matrix. For example, silver and zinc oxide nanoparticles, commonly used for their antimicrobial properties in food packaging, have been found to migrate in low concentrations, raising concerns about long-term exposure [161].

Nanomaterials, due to their small size and large surface area, have the potential to interact with biological systems in unintended ways. Cytotoxicity tests involving cells in vitro have shown that certain nanoparticles, like titanium dioxide and silver nanoparticles, can cause oxidative stress, inflammation, and even DNA damage [162], Genotoxicity testing is essential to determine the potential of nanoparticles to induce mutations, which could have long-term health implications. Toxicity assessments often involve in vivo testing on animals, where doses of nanoparticles are introduced through ingestion or skin contact to study their effects on different organs [145]. Recent studies using rodents have shown that nanoparticles such as zinc oxide and silicon dioxide, when ingested at high doses, can accumulate in organs such as the liver and spleen, leading to systemic toxicity [163]. This highlights the importance of establishing safe limits for nanoparticle exposure in food-contact materials. Government agencies like the European Food Safety Authority and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration have issued guidelines for the use of engineered nanomaterials in food-contact applications [162]. These guidelines emphasize the need for thorough risk assessment which includes evaluations of toxicity, bio persistence, and potential bioaccumulation in the body. The EFSA recommends that any new nanomaterial intended for use in food packaging must undergo a full safety evaluation, focusing on migration studies, as well as acute and chronic toxicity assessments [164]. To mitigate the potential toxicity risks associated with nanotechnology in food contact materials, researchers are focusing on developing biodegradable nanomaterials and safer nanoparticle coatings. These materials are designed to minimize migration and ensure that any exposure to nanoparticles is well within safe limits.

4.4 Limitations and challenges

Assessment of risks pertaining to the health of the consumers is the most important parameter that needs to be kept in mind when working with nanomaterials. The safety and quality of food is the utmost priority of any food inspecting authority. The utilization of nanomaterials to purify water has been already noted to be toxic to the environment and to human life forms. Nanoforms used in these exports of quality drinking water need to be addressed in detail in the future [140,159]. Various forms of nanocarbon like single-walled, multi-walled, buckyballs and quantum dots have shown undesirable interactions with markers and test reagents that make it quite an unreliable nanosystem for food processing. Thus, extensive real-time evaluation is termed necessary for the application of nanomaterials when applied to food products. Developing targeted and specific assessment assays is a major challenge that researchers face that would aid them to analyze the safety of nanosystems for enhancing food quality for commercial applications [165,166]. Furthermore, less heat is used for nanoencapsulation to inactivate or kill microorganisms than in the thermal process, which allows for energy savings. It is important to remember that an innovative ohmic heating method can be used in place of traditional heating [167]. Biodegradable polymers can decompose or degrade after use, making them great substitutes for the non-biodegradable packaging stated above. This is due to the difficulties in achieving oxygen/water vapor barrier performance on par with conventional petroleum-based polymers, or their blends [168]. In the food sector, encapsulating natural preservatives is a useful tactic for shielding delicate ingredients from unfavorable processing-related environmental factors. Even in modest concentrations, this method improves the stability and effectiveness of preservatives, enabling continuous release and residual antibacterial action. Nanoemulsions, polymer nanoparticles, and nanoliposomes are often used as nanocarriers for this reason since they all provide the enclosed substances with controlled release characteristics [169,170]. Despite the fact that nanocomposites are widely used in the production of food, active food packaging, and delivery of functional ingredients, the majority of these applications have focused on the nanoparticles that incorporate nanocomposites. There are fewer applications for other nanocarriers such as nanogels, nanoemulsions, nano-micelles, and nanoliposomes. These systems have greater advantages over nanoparticles, like higher loading and absorption efficiencies. It is necessary to expand the application ranges of different nanoencapsulation systems [161].

5 Conclusion

The present article deals with the use of nanotechnology in food processing using promising polymeric nanomaterials. Among the various polymeric nanomaterials used in food processing carbon nanotubes and allyl isothiocyanate are known to regulate many metabolisms associated with cooked produces especially chicken by depleting pathogenic population and change in aesthetic appeal of the cooked chicken for up to 40 days. Nanoscience provides new innovative tools and alternatives to scientists to reach new extremes in the area of food sciences. For example, the arrangement of amylopectin and amylose of starch in food binding processes are candidates for nanomaterials. In all the innovations done, one thing is tried to keep constant is the natural balance and the originality of the food. Nanosystem-based health drinks have 33% more micro and macro nutrients which will aid in the overall development of infants. Design protocols were mostly found to be biocompatible and environment friendly. The concentration of 0.2% of nanosized zinc oxide is found to be optimal to effectively reduce the mold proliferation for up to 12 days. Two main crossroads for any food researcher would be to either go for nanofood processing or nano food sensing aspect. The use of a green approach to manufacture most of the components related to novel foods is in great demand as it gives a sense of clean and green technology-based drive. The application of polymeric nanomaterials like allyl isothiocyanate and carbon nanotubes, which have been demonstrated to improve the shelf life and aesthetic quality of cooked goods like chicken by lowering pathogenic populations, opens up revolutionary possibilities for food processing and preservation using nanotechnology. Applications of nanoscience in food science, such as the alignment of amylopectin and amylose in starch binding processes, show how versatile nanoscale substances are in enhancing the texture, structure, and usefulness of food. Furthermore, by providing 33% more nutritional content than conventional formulations, nano-based health drinks enhanced with micro- and macronutrients hold the potential for enhancing nutritional outcomes, especially in vulnerable groups like babies. Biocompatibility and environmental sustainability are crucial factors to take into account as research progresses, with an increased emphasis on eco-friendly techniques and green synthesis processes. In addition to improving food safety, innovations like edible and biodegradable packaging materials also lessen their negative environmental effects. These advancements are in line with the industry’s increased emphasis on sustainability and clean technology. Even yet, there are still a lot of obstacles to overcome. Nanofood technologies need to be further refined to make them commercially viable. More efficient production procedures are also required. Furthermore, even though nanoparticles have a lot to offer in terms of food safety, preservation, and nutrient delivery, more research needs to be done on their possible toxicity and long-term health impacts. To fully comprehend how nanoparticles interact with biological systems and how they affect the environment, more thorough research is needed. Global laws and safety standards need to advance together with technology to address these worries. For consumer use of nano-based food items to be both safe and effective, a strong regulatory framework must be established. Furthermore, by providing a methodical way to mimic and improve the physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of nanofood systems, mathematical modeling tools may be crucial in optimizing design and development processes. Even though there have been great advancements in the use of nanotechnology in food science, innovation in this field must be balanced with sustainability, scalability, and safety. To fully utilize nanotechnology in food processing and produce safer, more nutrient-dense, and environmentally friendly food items, extensive regulatory policies and ongoing research are required.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this research work through a Large Research Project under the grant number RGP2/292/1445.

-

Funding information: The research was granted by Large Research Project under the grant number RGP2/292/1445.

-

Author contributions: Nibedita Dey and Monisha Mohan: original draft, writing – review and editing, methodology, and formal Analysis; Ramesh Malarvizhi Dhaswini, Arpita Roy, and Mohammed Mujahid Alam: writing – original draft, formal analysis, visualization, and project administration; Abdullah G. Al-Sehemi, Rasiravathanahalli Kaveriyappan Govindarajan, Muhammad Fazle Rabbee, Thanigaivel Sundaram, and Maximilian Lackner: resource.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Huimin C, Xixi C, Jing C, Shaoyun W. Self-assembling peptides: Molecule nanostructure-function and application on food industry. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2022;120:212–22. 10.1016/j.tifs.2021.12.027.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Bugusu B, Mejia C, Magnuson B, Tafazoli S. Global regulatory policies on: Food nanotechnology. Food Technol. 2009;63:24–8, https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20093148676 (accessed November 24, 2022).Search in Google Scholar

[3] Gilmore LA, Redman LM. Weight gain in pregnancy and application of the 2009 IOM guidelines: Toward a uniform approach. Obesity. 2015;23:507–11. 10.1002/oby.20951.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Aguilera J, Stanley D. Microstructural principles of food processing and engineering. Germany: Springer Science & Business Media; 1999, https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=nIeJiL_dLeQC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=Aguilera+JM+and+Stanley+DW+1999&ots=q-WmIJD8K4&sig=E6-4aKIIohdodclPyJijsP7hMAg (accessed November 24, 2022).Search in Google Scholar

[5] Nasrollahi M, Fathi MR, Sobhani SM, Khosravi A, Noorbakhsh A. Modeling resilient supplier selection criteria in desalination supply chain based on fuzzy DEMATEL and ISM. Int J Manag Sci Eng Manag. 2021;16:264–78. 10.1080/17509653.2021.1965502.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Freger V, Ramon GZ. Polyamide desalination membranes: Formation, structure, and properties. Prog Polym Sci. 2021;122:101451. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2021.101451.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Chen C, Sun M, Wang J, Su L, Lin J, Yan X. Active cargo loading into extracellular vesicles: Highlights the heterogeneous encapsulation behaviour. J Extracell Vesicles. 2021;10:12163. 10.1002/jev2.12163.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] VanDecar JC, Russo RM, James DE, Ambeh WB, Franke M. Aseismic continuation of the Lesser Antilles slab beneath continental South America. J Geophys Res Solid Earth. 2003;108:2043. 10.1029/2001jb000884.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Sebaaly C, Greige-Gerges H. Advances in the application of liposomes in dairy industries. In Liposomal Encapsulation Food Sci. Technol. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2023. p. 125–44. 10.1016/b978-0-12-823935-3.00008-4.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Zhang L, Gu FX, Chan JM, Wang AZ, Langer RS, Farokhzad OC. Nanoparticles in medicine: Therapeutic applications and developments. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83:761–9. 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100400.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Tripathi PK, Gorain B, Choudhury H, Srivastava A, Kesharwani P. Dendrimer entrapped microsponge gel of dithranol for effective topical treatment. Heliyon. 2019;5:01343. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01343.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Baruah A, Chaudhary V, Malik R, Tomer VK. Nanotechnology based solutions for wastewater treatment. Nanotechnol Water Wastewater Treat Theory Appl. 2019;1:337–68. 10.1016/B978-0-12-813902-8.00017-4.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Singh AR, Desu PK, Nakkala RK, Kondi V, Devi S, Alam MS, et al. Nanotechnology-based approaches applied to nutraceuticals. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2022;12:485–99. 10.1007/s13346-021-00960-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Kesharwani P, Choudhury H, Meher JG, Pandey M, Gorain B. Dendrimer-entrapped gold nanoparticles as promising nanocarriers for anticancer therapeutics and imaging. Prog Mater Sci. 2019;103:484–508. 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2019.03.003.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Kesharwani P, Banerjee S, Gupta U, Mohd Amin MCI, Padhye S, Sarkar FH, et al. PAMAM dendrimers as promising nanocarriers for RNAi therapeutics. Mater Today. 2015;18:565–72. 10.1016/j.mattod.2015.06.003.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Anzani C, Boukid F, Drummond L, Mullen AM, Álvarez C. Optimising the use of proteins from rich meat co-products and non-meat alternatives: Nutritional, technological and allergenicity challenges. Food Res Int. 2020;137:109575. 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109575.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Dasgupta N, Ranjan S, Gandhi M. Nanoemulsions in food: market demand. Env Chem Lett. 2019;17:1003–9. 10.1007/s10311-019-00856-2.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Delfanian M, Sahari MA. Improving functionality, bioavailability, nutraceutical and sensory attributes of fortified foods using phenolics-loaded nanocarriers as natural ingredients. Food Res Int. 2020;137:109555. 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109555.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Raj H, Tripathi S, Bauri S, Mallick Choudhury A, Sekhar Mandal S, Maiti P. Green composites using naturally occurring fibers: A comprehensive review. Sustain Polym & Energy. 2023;1:1–26.10.35534/spe.2023.10010Search in Google Scholar

[20] Samir A, Ashour FH, Hakim AAA, Bassyouni M. Recent advances in biodegradable polymers for sustainable applications. Npj Mater Degrad. 2022;6:68. 10.1038/s41529-022-00277-7.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Karimah A, Ridho MR, Munawar SS, Adi DS, Ismadi N, Damayanti R, et al. A review on natural fibers for development of eco-friendly bio-composite: characteristics, and utilizations. J Jpn Res Inst Adv Copper-Base Mater Technol. 2021;13:2442–58.10.1016/j.jmrt.2021.06.014Search in Google Scholar

[22] Arun R, Shruthy R, Preetha R, Sreejit V. Biodegradable nano composite reinforced with cellulose nano fiber from coconut industry waste for replacing synthetic plastic food packaging. Chemosphere. 2022;291:132786.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.132786Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Rafiee K, Schritt H, Pleissner D, Kaur G, Brar SK. Biodegradable green composites: It’s never too late to mend. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem. 2021;30:100482.10.1016/j.cogsc.2021.100482Search in Google Scholar

[24] Mugdha Bhat K, Rajagopalan J, Mallikarjunaiah R, Nagaraj Rao N, Sharma A. Eco-friendly and biodegradable green composites. In Biocomposites. London, United Kingdom: IntechOpen; 2022.10.5772/intechopen.98687Search in Google Scholar

[25] Jiménez A, Zaikov GE. Recent advances in research on biodegradable polymers and sustainable composites. USA: Nova Science Publishers Inc; 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Dong T, Yun X, Li M, Sun W, Duan Y, Jin Y. Biodegradable high oxygen barrier membrane for chilled meat packaging. J Appl Polym Sci. 2015;132:41871. 10.1002/app.41871.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Rukmanikrishnan B, Ramalingam S, Rajasekharan SK, Lee J, Lee J. Binary and ternary sustainable composites of gellan gum, hydroxyethyl cellulose and lignin for food packaging applications: Biocompatibility, antioxidant activity, UV and water barrier properties. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;153:55–62.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.03.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Roy S, Rhim J-W, Jaiswal L. Bioactive agar-based functional composite film incorporated with copper sulfide nanoparticles. Food Hydrocoll. 2019;93:156–66.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.02.034Search in Google Scholar

[29] Rukmanikrishnan B, Ismail FRM, Manoharan RK, Kim SS, Lee J. Blends of gellan gum/xanthan gum/zinc oxide based nanocomposites for packaging application: Rheological and antimicrobial properties. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;148:1182–9.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.11.155Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Aaliya B, Sunooj KV, Lackner M. Biopolymer composites: a review. Int J Biobased Plast. 2021;3:40–84.10.1080/24759651.2021.1881214Search in Google Scholar

[31] Haris NIN, Hassan MZ, Ilyas RA, Suhot MA, Sapuan SM, Dolah R, et al. Dynamic mechanical properties of natural fiber reinforced hybrid polymer composites: a review. J Jpn Res Inst Adv Copper-Base Mater Technol. 2022;19:167–82.10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.04.155Search in Google Scholar

[32] Donkor L, Kontoh G, Yaya A, Bediako JK, Apalangya V. Bio-based and sustainable food packaging systems: relevance, challenges, and prospects. Appl Food Res. 2023;3:100356.10.1016/j.afres.2023.100356Search in Google Scholar

[33] Saha D, Bhattacharya S. Hydrocolloids as thickening and gelling agents in food: a critical review. J Food Sci Technol. 2010;47:587–97.10.1007/s13197-010-0162-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Shah P. Polymers in food. Polymer science and innovative applications. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2020. p. 567–92.10.1016/B978-0-12-816808-0.00018-4Search in Google Scholar

[35] Embuscado ME, Huber KC, eds. Edible films and coatings for food applications. 2009th edn. New York, NY: Springer; 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Cazón P, Velazquez G, Ramírez JA, Vázquez M. Polysaccharide-based films and coatings for food packaging: A review. Food Hydrocoll. 2017;68:136–48.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.09.009Search in Google Scholar

[37] Onyeaka H, Passaretti P, Miri T, Al-Sharify ZT. The safety of nanomaterials in food production and packaging. Curr Res Food Sci. 2022;5:763–74.10.1016/j.crfs.2022.04.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Rai M, Ingle AP, Gupta I, Pandit R, Paralikar P, Gade A, et al. Smart nanopackaging for the enhancement of food shelf life. Env Chem Lett. 2019;17:277–90.10.1007/s10311-018-0794-8Search in Google Scholar

[39] Ghanem AF, Youssef AM, Abdel Rehim MH. Hydrophobically modified graphene oxide as a barrier and antibacterial agent for polystyrene packaging. J Mater Sci. 2020;55:4685–700.10.1007/s10853-019-04333-7Search in Google Scholar

[40] Zafar A, Khosa MK, Noor A, Qayyum S, Saif MJ. Carboxymethyl cellulose/gelatin hydrogel films loaded with zinc oxide nanoparticles for sustainable food packaging applications. Polymers. 2022;14:5201. 10.3390/polym14235201.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Wang L, Dekker M, Heising J, Zhao L, Fogliano V. Food matrix design can influence the antimicrobial activity in the food systems: A narrative review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2024;64:8963–89.10.1080/10408398.2023.2205937Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Zhong J, Xia B, Shan S, Zheng A, Zhang S, Chen J, et al. High-quality milk exosomes as oral drug delivery system. Biomaterials. 2021;277:121126. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.121126.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Wadhawan J, Parmar PK, Bansal AK. Nanocrystals for improved topical delivery of medium soluble drug: A case study of acyclovir. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2021;65:102662. 10.1016/j.jddst.2021.102662.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Desai D, Shende P. Monodispersed cyclodextrin-based nanocomplex of neuropeptide Y for targeting MCF-7 cells using a central composite design. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2021;65:102692. 10.1016/j.jddst.2021.102692.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Saadat S, Pandey G, Tharmavaram M, Braganza V, Rawtani D. Nano-interfacial decoration of Halloysite Nanotubes for the development of antimicrobial nanocomposites. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2020;275:102063. 10.1016/J.CIS.2019.102063.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Mishra A, Pradhan D, Biswasroy P, Kar B, Ghosh G, Rath G. Recent advances in colloidal technology for the improved bioavailability of the nutraceuticals. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2021;65:102693. 10.1016/j.jddst.2021.102693.Search in Google Scholar

[47] McCarthy B, O’Neill G, Abu-Ghannam N. Potential psychoactive effects of microalgal bioactive compounds for the case of sleep and mood regulation: Opportunities and challenges. Mar Drugs. 2022;20:493. 10.3390/md20080493.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Lafontaine S, Caffrey A, Dailey J, Varnum S, Hale A, Eichler B, et al. Evaluation of variety, maturity, and farm on the concentrations of monoterpene diglycosides and hop volatile/nonvolatile composition in five Humulus lupulus cultivars. J Agric Food Chem. 2021;69:4356–70. 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c07146.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Mor S, Battula SN, Swarnalatha G, Pushpadass H, Naik LN, Franklin M. Preparation of casein biopeptide-loaded niosomes by high shear homogenization and their characterization. J Agric Food Chem. 2021;69:4371–80. 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c05982.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Wang YY, You LC, Lyu HH, Liu YX, He LL, Di Hu Y, et al. Role of biochar–mineral composite amendment on the immobilization of heavy metals for Brassica chinensis from naturally contaminated soil. Env Technol Innov. 2022;28:102622. 10.1016/j.eti.2022.102622.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Xu C, Qi J, Yang W, Chen Y, Yang C, He Y, et al. Immobilization of heavy metals in vegetable-growing soils using nano zero-valent iron modified attapulgite clay. Sci Total Env. 2019;686:476–83. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.330.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Saint Akadiri S, Bekun FV, Sarkodie SA. Contemporaneous interaction between energy consumption, economic growth and environmental sustainability in South Africa: What drives what? Sci Total Env. 2019;686:468–75. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.421.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Yang X, Lin J, Zhan Y. Effect of aged nanoscale zero-valent iron amendment and capping on phosphorus mobilization in sediment. Chem Eng J. 2023;451:139072. 10.1016/j.cej.2022.139072.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Dai W, Ruan C, Zhang Y, Wang J, Han J, Shao Z, et al. Bioavailability enhancement of EGCG by structural modification and nano-delivery: A review. J Funct Foods. 2020;65:103732. 10.1016/j.jff.2019.103732.Search in Google Scholar

[55] Mu R, Hong X, Ni Y, Li Y, Pang J, Wang Q, et al. Recent trends and applications of cellulose nanocrystals in food industry. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2019;93:136–44. 10.1016/j.tifs.2019.09.013.Search in Google Scholar

[56] Wang H, Zhang M, Hu J, Du H, Xu T, Si C. Sustainable preparation of surface functionalized cellulose nanocrystals and their application for Pickering emulsions. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;297:120062. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.120062.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] De Leo V, Maurelli AM, Giotta L, Catucci L. Liposomes containing nanoparticles: preparation and applications. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2022;218:112737. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2022.112737.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[58] Noah NM, Ndangili PM. Green synthesis of nanomaterials from sustainable materials for biosensors and drug delivery. Sens Int. 2022;3:100166. 10.1016/j.sintl.2022.100166.Search in Google Scholar