Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

-

Patcharin Naemchanthara

Abstract

In this research, cockleshell waste from food processing is developed into a humidity adsorbent using a simple technique. Cockleshells were first heated at 1,000°C. The crystal structure, functional group, and morphology of cockleshells before and after heat treatment were investigated. Cockleshells before heat treatment had the aragonite phase of CaCO3 compound, but it transformed into the CaO phase after heat treatment. Next, fried fish crackers, Keropok, were selected for humidity testing. The behavior of the humidity adsorbent and fried fish crackers was investigated for 0–180 days. After humidity testing, the CaO phase of the humidity adsorbent reacted with the humidity or water molecules and transformed into the Ca(OH)2 phase. The amount of crack and roughness on the humidity adsorbent surface increased with the increase in humidity testing time. The humidity adsorbent underwent a high humidity reaction and transformed into Ca(OH)2 after 30 days. The water activity, crispness, and thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) of fried fish crackers were analyzed. The water activity of fried fish crackers rapidly decreased, whereas the crispness slowly decreased in the range of 0–30 days. The humidity adsorbent controlled the TBARS value by increasing slowly. Based on these results, cockleshell waste can be developed as a humidity adsorbent and used to prolong the shelf-life of local food products to at least 90 days.

1 Introduction

Sea animals are of various types such as fish, shrimp, jellyfish, squid, crab, shell, etc. Some of the sea animals can be cooked to a variety of seafoods that have a unique taste and high protein content [1]. Moreover, seafood is popular among people of many religions and nationalities. Thailand is one of the countries that export various types of frozen seafoods due to the Southern Thailand border on the Gulf of Thailand and the Andaman Sea. Pattani province is a small area in Southern Thailand. Most of the Pattani people living near the coastal area are mostly local fishermen involved in fishing, floating basket farming, and seafood processing. Especially, the well-known local fishery is a traditional net fishing technique that using the net with floats and weights [2]. Fisheries provide fresh sea animals as raw materials for seafood restaurants and fresh seafood markets. Nevertheless, the large number of Thai seafood restaurants and food processing by the local people give rise to a considerable amount of seafood waste. For instance, the fresh shrimp provided the waste about a quarter of shrimp [3,4]. The waste management from this seafood waste is a big problem for local officers as a Municipality. Seafood waste not only causes a problem of waste management but also pollutes the air and can disturb the coastal tourism in these areas [5]. Though the solution to this waste management is also landfill, the key factor is its unsustainability. So, recycling the waste is a worthy way for zero waste management that follows the United Nation (UN) statements on March 30, 2023 [6]. In addition, this way also results in sustainable waste management for the community and follows the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of Thailand policy [7]. Thus, the cockleshell waste from Thai seafood processing, approximately 579 tons per year in Pattani, is considered for the study [8,9]. Cockleshells, widely used as a source for animal feed, soil additive, and additive to structural and paper industries, consist of more than 95% of calcium compound [10]. However, these calcium compounds are utilized due to the complex recycling process and cannot operate with the local people [11].

Therefore, this work focuses on developing calcium sources from cockleshell waste with a simple technique that can be used in the Pattani community following the SDGs. Nonetheless, our previous works present the success of the development of humidity adsorption material from various calcium sources [12,13,14]. So, the aim of this work is to develop the cockleshell waste in Pattani as a humidity adsorbent that the local people can use.

Additionally, fried fish crackers, namely Keropok, a famous local snack and an appetizer in pub and bar restaurants, were used in the study [15]. Production of fried fish crackers is encouraged by the Thai government policy as a “One Tambon (sub-district) One Product; OTOP,” causing the fried fish crackers to be recognized and made available in tourist towns and all regions of Thailand [16]. Fried fish crackers were contributed by hawkers from Pattani. As the fried fish crackers were produced without food additives and preservatives by households or small enterprises in the Pattani community, the crispness of this fried fish crackers may be easily decreased by the humidity during the delivery and marketing [17].

Consequently, the humidity adsorbent of this work was developed from cockleshell waste by the heat treatment process. The cockleshells before and after heat treatment were characterized for their crystal structure, functional group, and morphology. Afterward, the humidity adsorbent was applied with fried fish crackers and characterized. The humidity adsorbent before and after humidity testing was analyzed for the crystal structure, functional group, and morphology. However, the water activity, crispness, and thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) of fried fish crackers before and after humidity testing were addressed.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Preparation of the humidity adsorbent and fried fish cracker

2.1.1 Humidity adsorbent preparation

Cockleshells were collected from a local seafood restaurant at Rusamilae subdistrict in Pattani province, Thailand. The cockleshells were soaked in fresh water for 24 h. Then, they were cleaned and polished to remove the soil and organic matter contamination. The cockleshells were air-dried for 12 h under atmospheric pressure at room temperature. The cockleshells were crushed by a jaw crusher machine (Retsch, model BB200) and ground by a grinder machine (SPEX CertiPrep, model 8000-D Mixer Mill) to get cockleshell powder. The cockleshell powder was passed through a sieve of stainless steel (Endecotts, pore size: 106 µm) as the particle size was less than 100 µm. Next, the cockleshell powder was heated up to 1,000°C using a high-temperature furnace (Carbolite, AAF1100/18) with a heating rate of 5°C·min−1 for 4 h and cooled down in a furnace to room temperature. Then, 3 g of cockleshell powder was filled in a tea filter bag and heat-sealed as a humidity adsorbent. Eight groups of humidity adsorbents were made for humidity adsorption testing for 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 60, 90, and 180 days and stored in a desiccator to prevent exposure to humidity.

2.1.2 Fried fish cracker preparation

Sheet-dried fish crackers (fresh fish crackers) were purchased from the people of Thailand Muslim community in Pattani, Thailand. Samples with an approximate diameter of 40 mm, a thickness of 2 mm, and a weight of 1.25 g were selected from the sheet-dried fish crackers. Then, all samples were fried at 180°C using an electric deep fryer containing 2 l of palm oil. The samples were put in the frying stainless steel basket (18 × 20 × 11 cm3) and then dipped into palm oil for 30 s. Then, the fried fish crackers were drained on a screen for 5 min and blotted with a paper towel to remove the excess oil. All fried fish crackers were allowed to cool at room temperature for 15 min. Finally, 15 g of fried fish crackers was taken in a polyethylene terephthalate plastic bag with a size of 175 × 210 mm2 for humidity adsorption testing under various conditions and stored in a desiccator to prevent humidity exposure.

2.2 Humidity adsorption testing and characterization

2.2.1 Humidity adsorption testing

For humidity adsorption testing, a humidity adsorbent and a fried fish cracker were taken and heat sealed and tested for various time ranges. After humidity adsorption testing was carried out, the behavior of fried fish crackers without a humidity adsorbent (control) and with 3 g of humidity adsorbent was investigated at 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 60, 90, and 180 days.

2.2.2 Characterization of cockleshell powder before and after humidity adsorption testing

For characterization of the cockleshell powder before humidity adsorption testing, its crystal structure and phase transformation before and after heating at 1,000°C were investigated by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku SmartLab SE). The XRD was performed with CuKα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å) at 30 kV and 40 mA in a 2θ range of 10°–80° with a scan step of 0.02°. The XRD patterns were used to obtain the quantitative phase composition by Rietveld refinement using the Match! Program, version 4.0. The functional groups of cockleshell powder before and after heating at 1,000°C were analyzed by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (PerkinElmer, Spectrum Two) in a range of 4,000–400 cm−1 with a resolution of 1 cm−1. The morphology of cockleshell powder before and after heating at 1,000°C was monitored by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Thermo Scientific, Axia ChemiSEM). The samples were put on carbon tape and coated with gold using sputtering for 30 s. The SEM image was converted to the grayscale. The rectangular zone of the SEM image was selected and analyzed for the surface roughness (R a) by the ImageJ program, version 1.54d. After humidity testing of the humidity adsorbent, the XRD, FTIR, and SEM techniques were also used to identify the phase transformation, functional groups, and morphology.

2.2.3 Characterization of fried fish crackers before and after humidity adsorption testing

The water activity of fried fish crackers before and after humidity adsorption testing was determined using a water activity meter (AquaLab 4TE). The fried fish crackers were ground by an agate mortar and pestle. About 2 g of fried fish cracker powder was placed in a water activity tray [18,19]. For the penetration test before and after humidity adsorption testing, the crispness of fried fish crackers was measured using a Texture Analyzer (Stable Micro Systems, TA.XTplus). The fried fish crackers were placed onto a heavy-duty platform/crisp fracture support rig and a spherical probe (P/0.25) was used. The conditions of the Texture Analyzer were a test speed of 2.0 mm·s−1, a probe travel distance of 5 mm, and a trigger force of 5 g. The penetration test was repeated till precision data were obtained. TBARS in fried fish crackers were determined according to the method recommended by Tarladgis et al. and expressed as mg of malondialdehyde per kg (mg MDA·kg−1) sample [20]. The water activity, crispness, and TBARS of fried fish crackers without a humidity adsorbent (control) and with 3 g of humidity adsorbent were analyzed and addressed.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of cockleshells

The cockleshell waste was collected from a local seafood restaurant and ground into cockleshell powder. The cockleshell powder was studied by the FTIR technique for determining functional groups, and the results are shown in Figure 1.

FTIR spectrum of cockleshell powder.

Figure 1 displays the FTIR spectrum of cockleshell powder, which shows peaks at 713 cm−1 (v

4), 858 cm−1 (v

2), 1,468 cm−1 (v

3), and 1,083 cm−1 (v

1), assigned to the C–O symmetric bending vibrations of

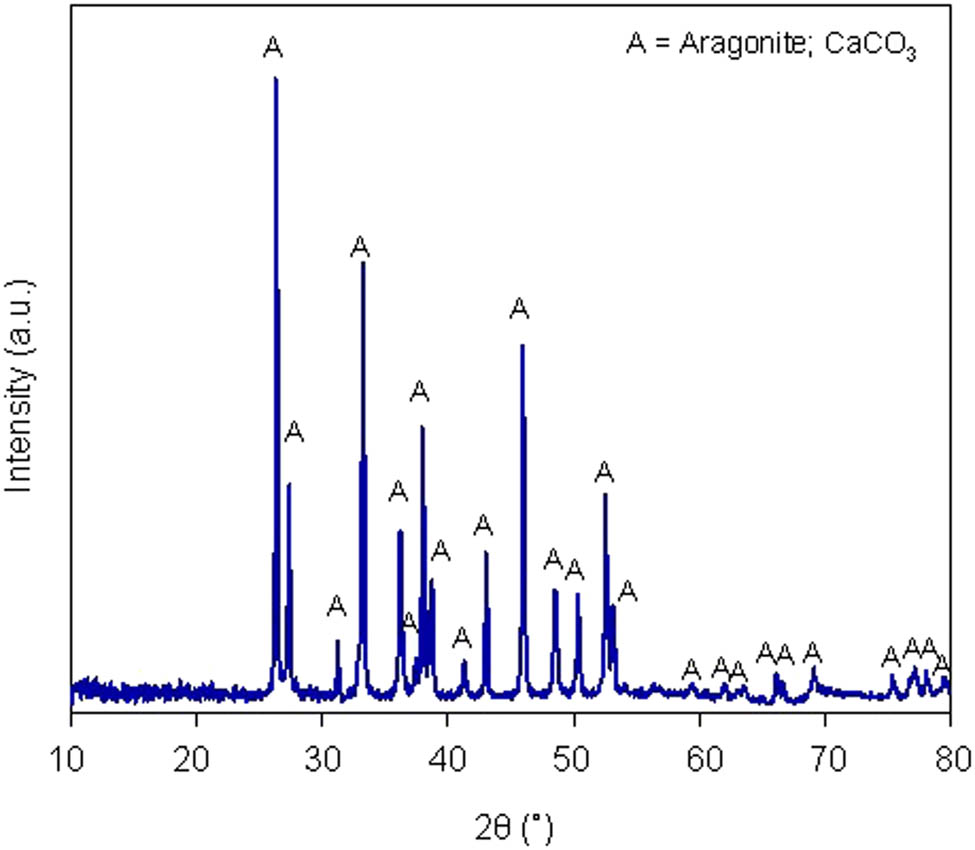

Next, the crystal structure of cockleshell powder was investigated by the XRD technique, and the XRD pattern is shown in Figure 2.

XRD pattern of cockleshell powder.

Figure 2 displays the XRD pattern of cockleshell powder, which shows peaks at 2θ ≈ 26.32, 33.24, 37.96, 45.96, and 52.52°, assigned to the aragonite phase of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) compound according to the Joint Committee Powder Diffraction Standard (JCPDS) No. 05-0453. This result is related to the carbonate group and in good agreement with the FTIR result.

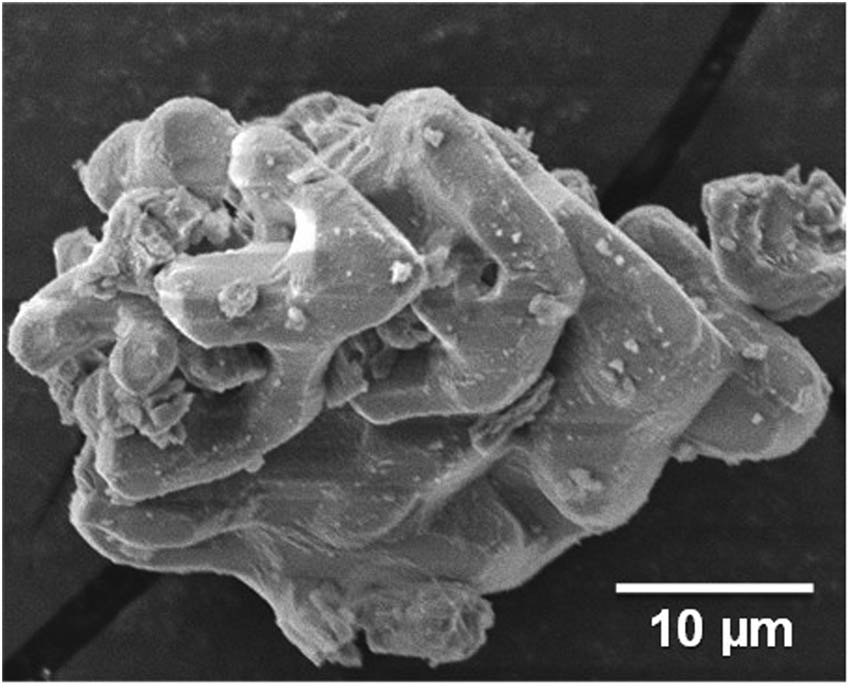

Then, the morphology of cockleshell powder was analyzed by the SEM technique, and the SEM image is shown in Figure 3.

Morphology of cockleshell powder.

Figure 3 shows the morphology of cockleshell powder, which revealed dense accumulated layers of needle and rod shaped sheets, indicating aragonite sheet layers. This morphology is commonly found in shells [23].

After the cockleshell powder was heated at 1,000°C for 4 h, the functional group of cockleshell powder was analyzed by FTIR, and the spectrum is shown in Figure 4.

FTIR spectrum of cockleshell powder after heating at 1,000°C for 4 h.

The FTIR spectrum of cockleshell powder after heating at 1,000°C for 4 h (Figure 4) shows peaks at 870 and 1,068 cm−1, assigned to the symmetric stretching vibration of C–O [24]. The peak at 451 cm−1 is assigned to symmetric vibrations of Ca–O [25]. This means that the FTIR spectrum of cockleshell powder after heating did not show a carbonate peak, as compared with cockleshell powder before heating, and this confirms that the heating at 1,000°C can decompose the carbonate group in the cockleshell powder.

The decomposition of calcium carbonate of cockleshell powder was confirmed by investigating the crystal structure and phase transformation by XRD (Figure 5).

XRD pattern of cockleshell powder after heating at 1,000°C for 4 h.

Figure 5 displays the XRD pattern of cockleshell powder after heating at 1,000°C for 4 h, which shows peaks of 2θ at 32.30, 37.45, 53.95, 64.25, and 67.45°, which is a lime phase of calcium oxide (CaO) according to the JCPDS No. 82-1691. The XRD results indicated that the aragonite phase of cockleshell powder can be completely transformed into calcium oxide. During heat treatment at 1,000°C for 4 h, calcium carbonate consists of carbonate ions (

Moreover, the morphology of cockleshell powder after heating at 1,000°C for 4 h was analyzed by SEM, and the SEM image is shown in Figure 6.

Morphology of cockleshell powder after heating at 1,000°C for 4 h.

The morphology of cockleshell powder after heating at 1,000°C for 4 h (Figure 6) shows a fragile cylindrical shape (spherical shape interconnected to a skeleton structure) with a smooth surface. The fragile cylindrical shape had an average diameter of approximately 5 µm. Moreover, the fragile cylindrical shape had an agglomeration and interconnection like a skeleton structure that is commonly found in the calcium oxide compound [12,26]. Normally, calcium oxide has a hydrophilic property and easily interacts with water molecules [27]. So, the fragile cylindrical shape of calcium oxide compound from cockleshell waste is interesting to further study in more detail its potential for humidity adsorption in fried fish crackers.

3.2 Humidity adsorption testing of cockleshell powder

The humidity adsorbent (heat-treated cockleshell powder) prepared from cockleshell powder was applied with fried fish crackers, and the humidity adsorption was studied on 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 60, 90, and 180 days. The functional groups of humidity adsorbent after humidity adsorption testing were identified by FTIR, and the results are shown in Figure 7.

FTIR spectra of the humidity adsorbent from cockleshell powder for the testing time range of 0–180 days.

Figure 7 presents the FTIR spectrum of the humidity adsorbent, which shows a new strong peak at 3,640 cm−1 as compared with that before humidity adsorption testing. This intensity of new peak was assigned to the O–H stretching vibration of water molecules after humidity testing from 5 to 180 days [28]. The new peak increased the intensity with increasing humidity adsorption testing time. In addition, the FTIR spectrum of the humidity adsorbent still shows a broadened peak around 1,408 cm−1, assigned to the asymmetric stretch of O–C–O corresponding to

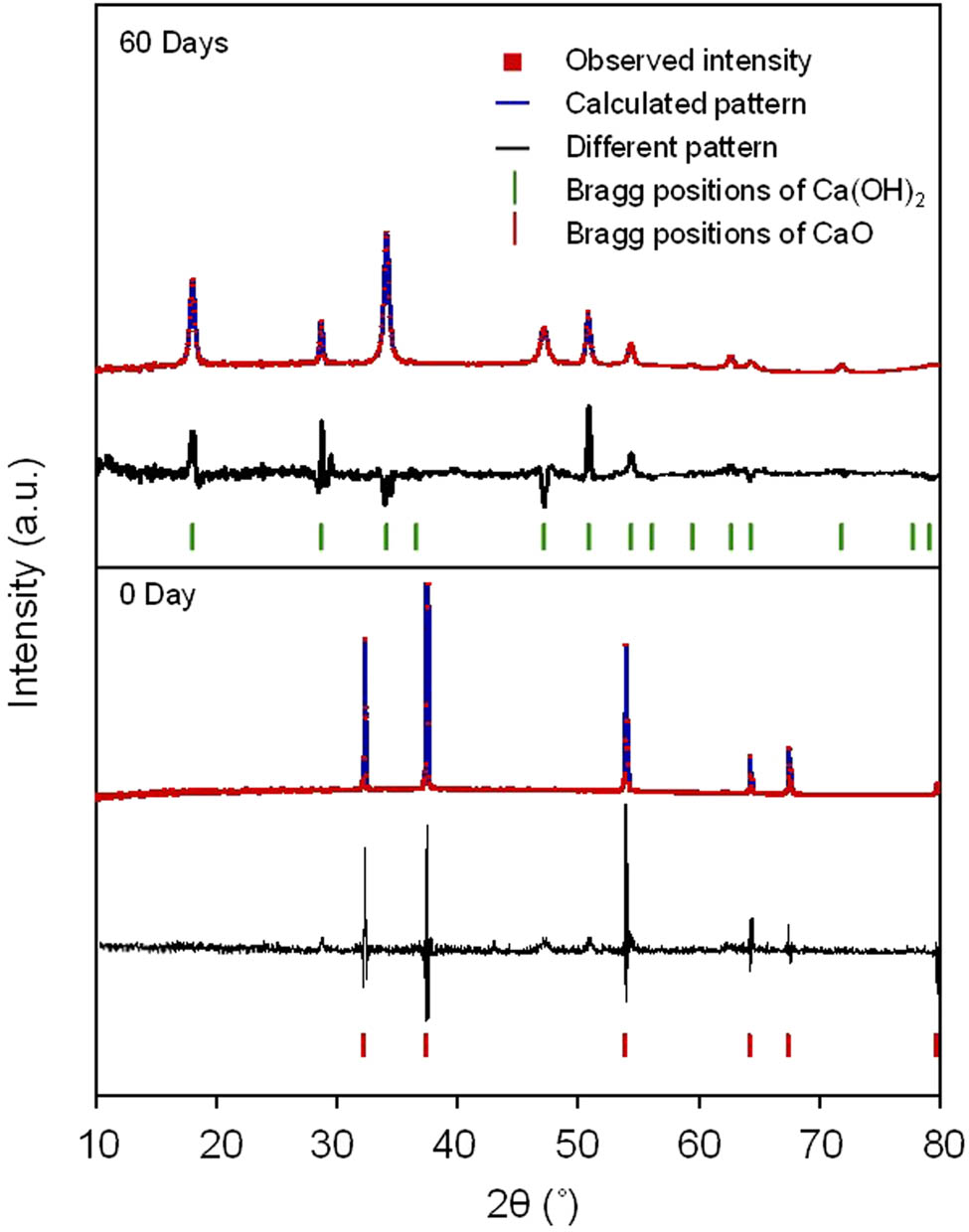

Moreover, the crystal structure and phase composition of the humidity adsorbent are shown in Figure 8.

XRD patterns of the humidity adsorbent from cockleshell powder for the testing time range of 0–180 days.

In Figure 8, the XRD patterns of the humidity adsorbent initially at day 0 show only the phase of CaO. The XRD patterns of the humidity adsorbent at day 5 show new peaks at 2θ of 17.95, 28.70, 34.05, 47.10, 50.85, 54.45, 62.75, and 71.90° corresponding to JCPDS No. 44-1481 of the portlandite phase of calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2) compound [31]. While the intensity of CaO as an initial phase decreased, the CaO compound adsorbs the humidity or water molecules resulting in the transformation to Ca(OH)2 according to Eq. 2 [32].

Considering the XRD pattern of Ca(OH)2, the intensity increased with the increase in the humidity adsorption testing time from 10 to 90 days, indicating that the humidity adsorbent adsorbed the humidity or water molecules. However, the XRD pattern of CaO decreased from 0 to 30 days and disappeared at 60 days. The disappearance of CaO indicated that CaO had completely transformed to Ca(OH)2 by reacting with humidity or water molecules. Then, the XRD pattern of only Ca(OH)2 was observed during 60–180 days, and there was no change in the XRD pattern intensity.

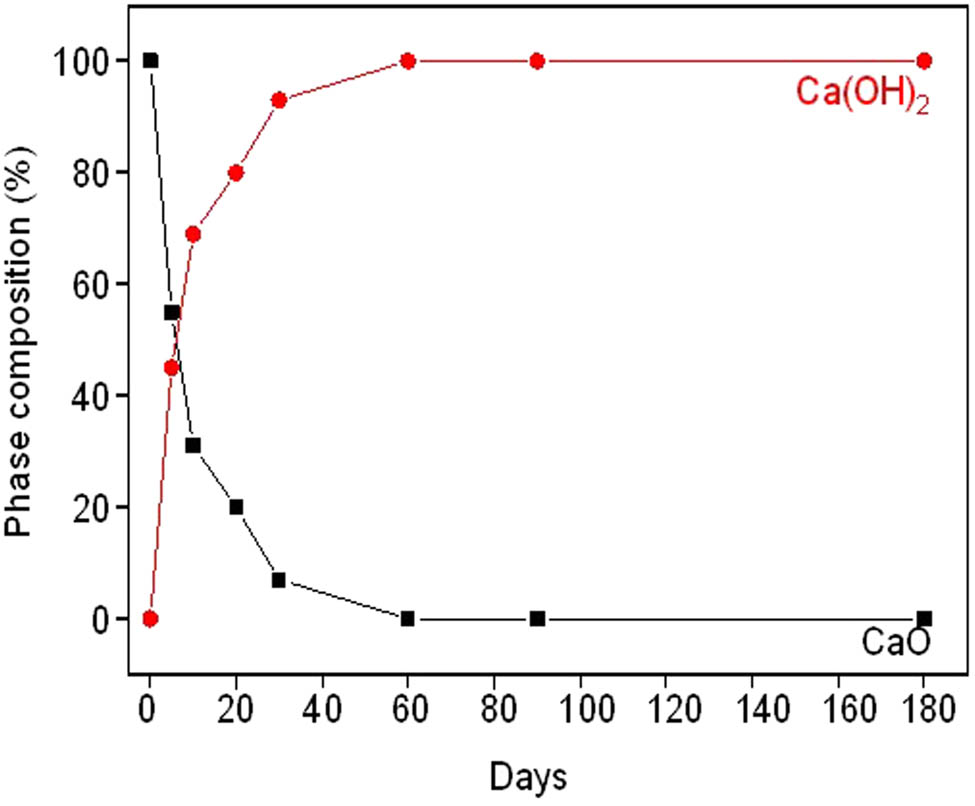

Next, the intensity of XRD patterns of the humidity adsorbent was studied in the time range of 0–180 days, and the quantitative phase composition was calculated by Rietveld refinement [33]; the results are shown in Figure 9.

Quantitive phase compositions of cockleshell powder after humidity adsorption testing.

Figure 9 shows that the CaO phase rapidly decreased after 60 days of humidity adsorption testing. At the same time, the Ca(OH)2 phase rapidly increased after 60 days.

To clarify the phase transformation of the humidity adsorbent from CaO to Ca(OH)2, the XRD patterns at 0 and 60 days were confirmed by Rietveld refinement, as shown in Figure 10.

Quantitive phase compositions of the humidity adsorbent after humidity testing at days 0 and 60.

Figure 10 shows that only the lime phase was present at day 0, whereas only the Ca(OH)2 phase was present at 60 days. It means that the CaO phase of the humidity adsorbent can be completely transformed into Ca(OH)2 within 60 days.

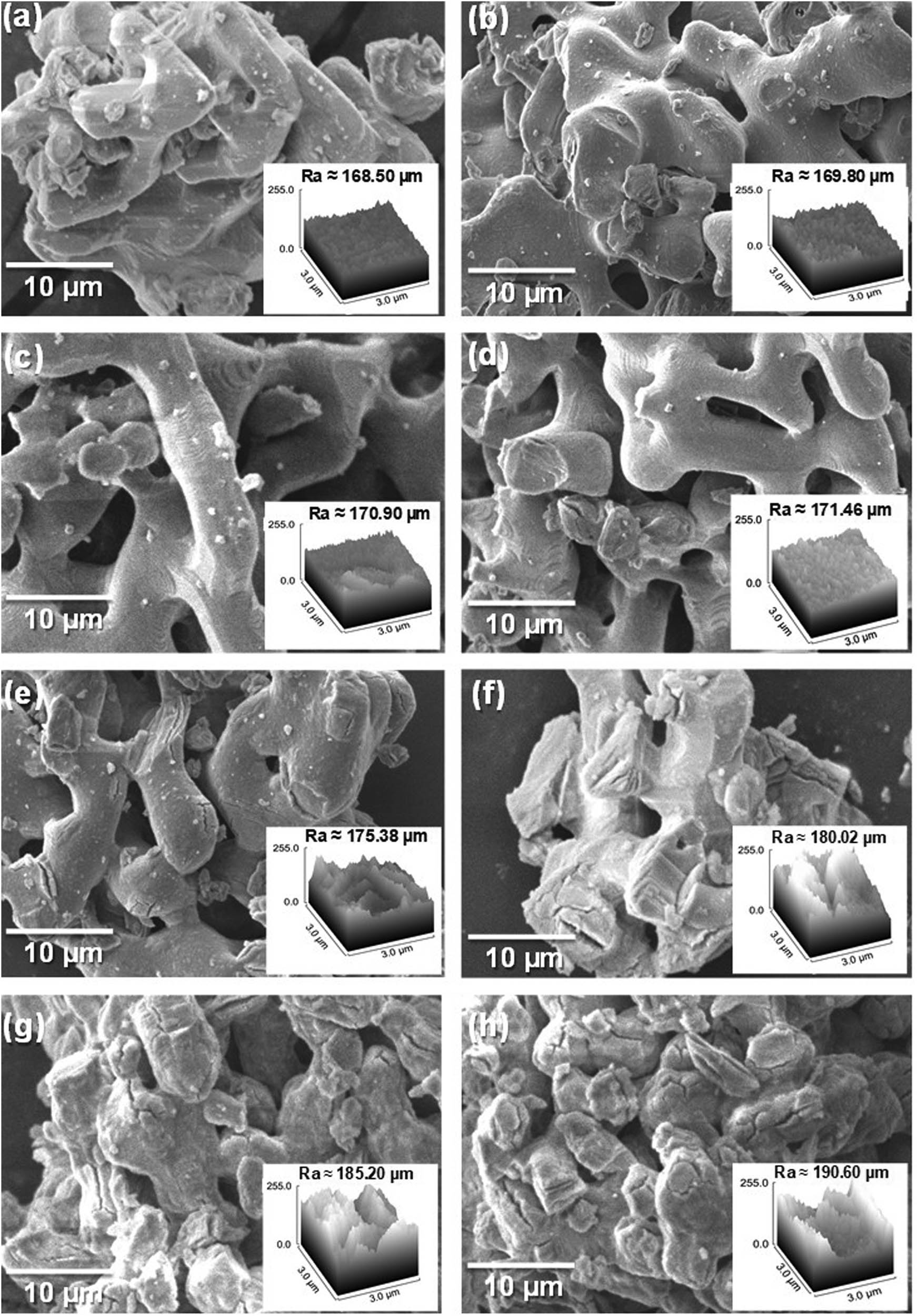

The morphology of the humidity adsorbent was identified by SEM, and the SEM images are shown in Figure 11.

Morphology of the humidity adsorbent after humidity testing at (a) 0, (b) 5, (c) 10, (d) 20, (e) 30, (f) 60, (g) 90, and (h) 180 days.

Figure 11(a)–(d) shows the morphology of the surface of the humidity adsorbent after humidity testing from 5 to 20 days; it still has a smooth surface similar to that at day 0 (before humidity testing). However, the humidity adsorbent after humidity testing for 30 days showed some of the microcracks on the surface.

After 30 days of humidity testing (Figure 11(e)–(h)), the crack on the surface clearly showed an increase with the increase of humidity testing time. This means that the appearance of the crack on the surface was due to the skeleton structure of CaO that adsorbed the water molecules and then swelled [12,34,35].

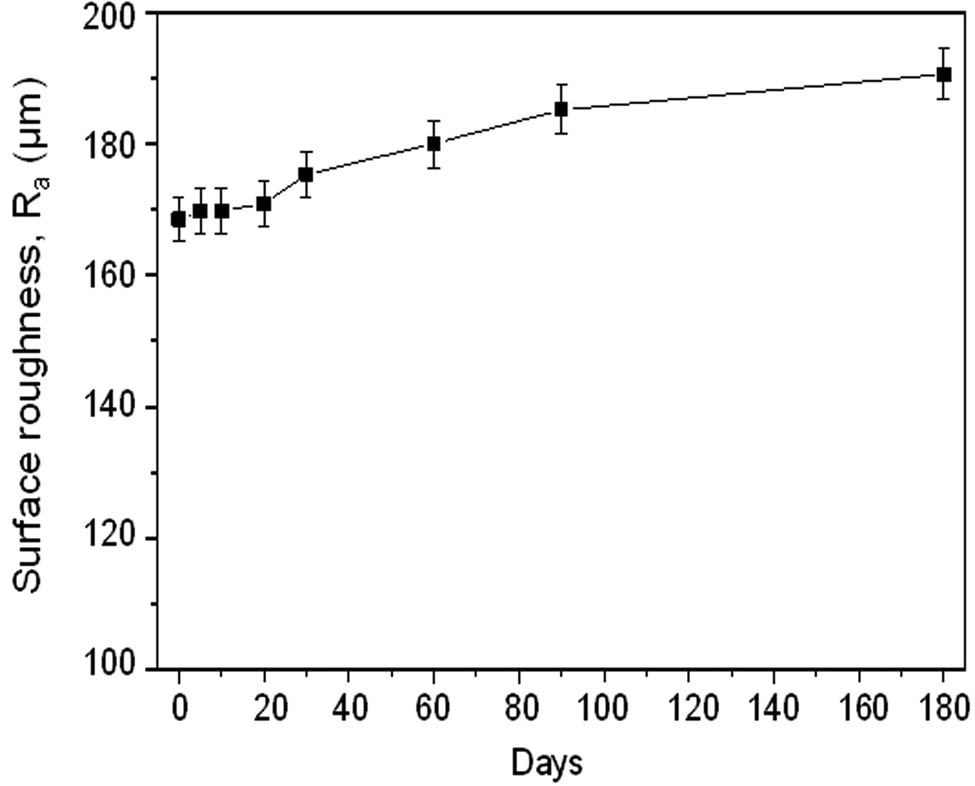

In addition, the surface roughness of the humidity adsorbent was analyzed on ten areas of SEM images using the ImageJ program [36]. The topography of each humidity adsorbent is shown at the right corner of Figure 11 images. The relationship between the average surface roughness (R a) [37] and the humidity testing time is shown in Figure 12.

Average surface roughness of the humidity adsorbent after humidity testing in the range of 0–180 days.

The average surface roughness of the humidity adsorbent during the humidity testing time of 0–20 days slightly increased with increasing humidity testing time. However, the average surface roughness of the humidity adsorbent between 20 and 30 days increased from 170.90 to 175.38 µm. Moreover, the average surface roughness dramatically increased after 30 days of humidity testing. This means that the increase in average surface roughness value results from the humidity adsorbent that adsorbed the humidity or water molecules. These results can confirm the previous results and explain the swelling of the skeleton structure.

3.3 Characterization of fried fish crackers

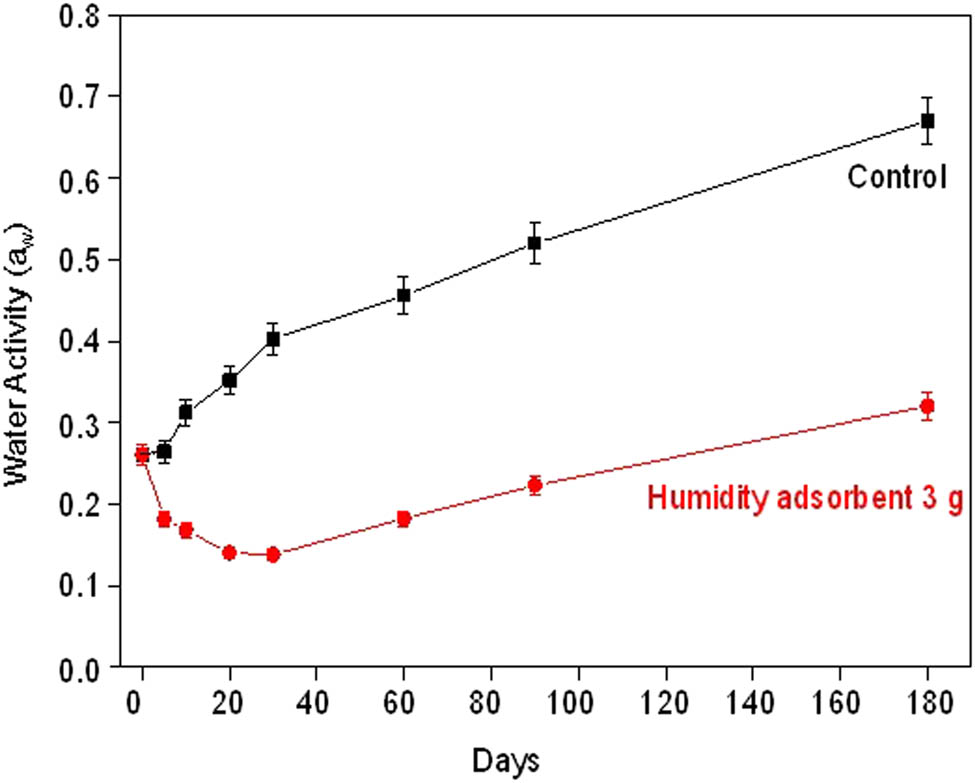

To prevent the spoilage from microorganisms and extend the shelf-life of fried fish crackers, an important parameter to control is water activity. The water activity on the surface of fried fish crackers was measured and is shown in Figure 13.

Water activity of fried fish crackers without humidity adsorbent (control) and with 3 g of humidity adsorbent for various humidity testing times.

The initial water activity (day 0) of fried fish crackers was on average 0.26 a w. Generally, the fried fish crackers have the water activity in the range of 0.30–0.40 a w [38]. This indicates that these fried fish crackers have a low level of water activity. During the test, the fried fish crackers with humidity adsorbent had water activity in the range of 0.26–0.32 a w, while that of control was in the range of 0.26–0.67 a w. The water activity value of the control is higher than that of the humidity adsorbent for all humidity testing time. However, fried fish crackers with the humidity adsorbent show a decrease of water activity during the humidity testing time of 0–30 days. This dramatic decrease in water activity resulted from the humidity adsorbent that adsorbed the humidity or water molecules. This means that the humidity adsorbent with a CaO phase has high sensitivity in the reaction of humidity or water molecules. Additionally, the water activity after the humidity testing time of 30 days slightly increased from 0.14 a w to 0.17, 0.22, and 0.32 a w at 60, 90, and 180 days, respectively. These results show that the potential of humidity adsorbent is close to the saturation point or like a constant slope of a linear relationship (about 60 days of humidity testing time) and relates to the complete phase transformation of humidity adsorbent from CaO to Ca(OH)2. Although the humidity adsorbent is close to the saturation point, the water activity value of fried fish crackers slightly increased. In addition, the water activity of fried fish crackers with the humidity adsorbent at 180 days was still 0.32 a w. This water activity can prevent microorganism growth and prolongs the shelf-life of fried fish crackers [38].

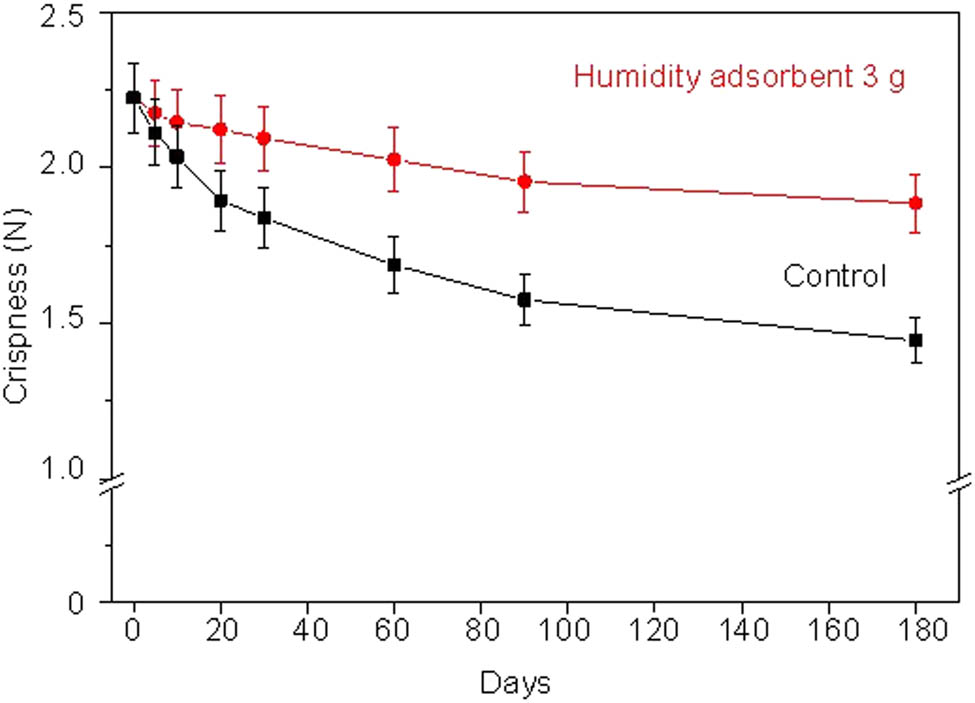

Crispness is an important parameter of fried fish crackers for consumer attraction. The crispness results are shown in Figure 14.

Crispness of fried fish crackers without humidity adsorbent (control) and with 3 g of humidity adsorbent for various humidity testing times.

From Figure 14, the initial crispness (0 day) of fried fish crackers had the highest value of 2.22 N. The fried fish crackers with humidity adsorbent have a crispness in the range of 2.22–1.88 kg·force, while that of control was 2.22–1.44 N. The crispness value of fried fish crackers with the humidity adsorbent is higher than that of the control during all humidity testing times. The crispness of fried fish crackers with the humidity adsorbent did not significantly decrease after a humidity testing time of 0–30 days when compared with the control. The humidity adsorbent adsorbed the humidity or water molecules that transmit into the air cell structure of fried fish crackers resulting in a fluidizing network. The fluidizing network in the fried fish crackers makes the crispness decrease [39]. After 30–180 days of testing, the crispness of fried fish crackers with the humidity adsorbent also decreased after humidity testing, whereas the crispness of control decreased gradually. Furthermore, the humidity adsorbent has high sensitivity in reacting with humidity and maintain the crispness of fried fish crackers.

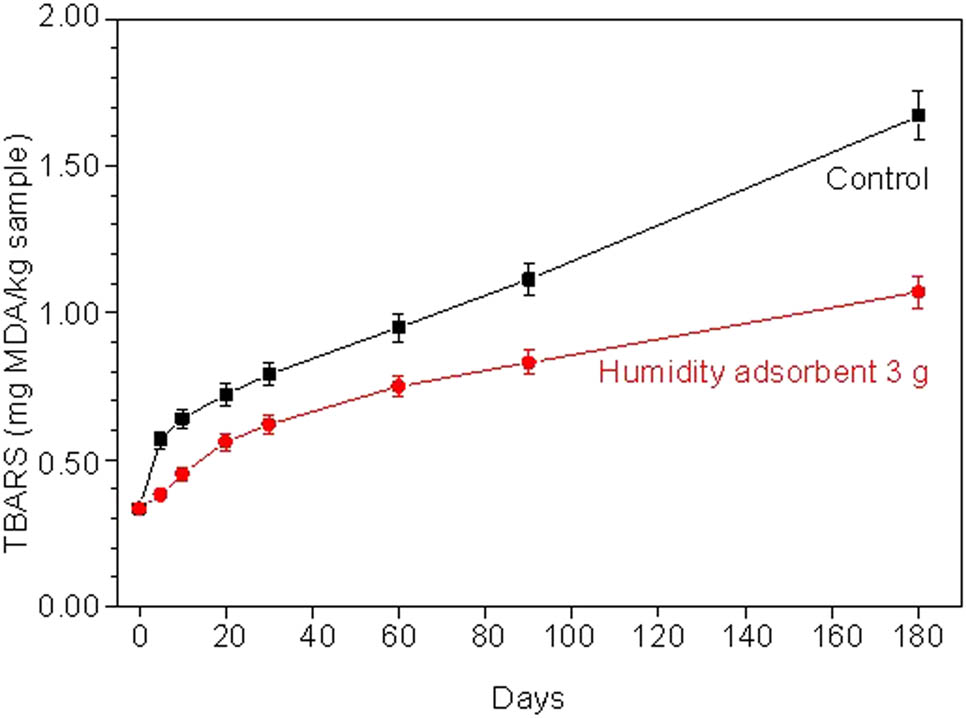

To support the potential for the humidity adsorbent from cockleshells, the rancid odor of the fried fish crackers was studied [40]. The TBARS values in all samples are shown in Figure 15.

TBAS values of fried fish crackers without humidity adsorbent (control) and with 3 g of humidity adsorbent for various humidity testing times.

The initial TBARS values (day 0) of fried fish crackers were about 0.29 mg MDA·kg−1 sample. The control in all periods of testing time shows the TBARS values in the range of 0.29–1.67 mg MDA·kg−1 sample. For 5 days, the TBARS values rapidly increased to 0.58 mg MDA·kg−1 sample. Because the initial packaging has oxygen molecules, the oxygen molecules immediately reacted with the lipid on the surface of the fried fish crackers [17]. After 5 days, the TBARS values gradually increased from 0.64, 0.72, and 0.79 mg MDA·kg−1 sample at 10, 20, and 30 days, respectively. This means that the oxygen concentration in packaging is low leading to the low reaction between lipids and oxygen. After 30 days, the TBARS values increased linearly to 0.95, 1.11, and 1.67 mg MDA·kg−1 sample at 60, 90, and 180 days, respectively. The tissue of fried fish crackers was damaged by the humidity or water molecules, resulting in the lipids in fried fish crackers easily reacting with the oxygen molecules due to lipid peroxidation [41]. While the fried fish crackers with the humidity adsorbent in all periods of testing time show the TBARS values in the range of 0.29–1.07 mg MDA·kg−1 sample. For 0–20 days, the TBARS value gradually increased from 0.29 to 0.56 mg MDA·kg−1 sample. The increase of TBARS in this range is affected by various mechanisms including the reaction of lipids with oxygen and humidity or water molecules in both the packaging and pores of fried fish crackers. However, the TBARS value of fried fish crackers with the humidity adsorbent is lower than that of the control. This is because the humidity or water molecules in the initial packaging were adsorbed by the humidity adsorbent resulting in low lipid oxidation. For 30–180 days, the TBARS values slightly increased from 0.62 to 1.07 mg MDA·kg−1 sample. At 180 days, the TBARS of the fried fish crackers with the humidity adsorbent had a low value of about 60% when compared with the control. The humidity adsorbent in packaging helps to adsorb humidity or water molecules and disrupt lipid oxidation.

Nevertheless, the general food has TBARS value in the range of 5.00–20.00 mg MDA·kg−1 sample [42]. For Thai food, the TBARS value should be less than 3.00 mg MDA·kg−1 sample, indicating that this food does not have a rancid odor [43,44]. Furthermore, the TBARS values at all times of fried fish crackers with and without humidity adsorbent show less than 3.00 mg MDA·kg−1 sample. Moreover, the TBARS results also related to the water activity results. All humidity testing results indicated that the humidity adsorbent from cockleshells can preserve the quality of fried fish crackers for at least 90 days.

4 Conclusions

The cockleshell waste was synthesized as the humidity adsorbent with the heat treatment process at approximately a temperature of 1,000°C for 4 h. XRD, FTIR, and SEM were used to characterize and confirm the crystal structure, functional group, and morphology of the humidity adsorbent, respectively. The cockleshell waste was mostly composed of calcium carbonate in the aragonite phase, which after the heat treatment process transforms into calcium oxide as a humidity adsorbent. The humidity adsorbent was applied to fried fish crackers during humidity testing for up to 180 days. After humidity testing of 30 days, the humidity adsorbent has high sensitivity in reacting with humidity and transforming into calcium hydroxide. At the same time, the fried fish crackers were studied for water activity, crispness, and TBARS. During the initial 30 days of humidity testing time, the values of water activity and crispness of fried fish cracker with the humidity adsorbent decreased, whereas the value of TBARS of fried fish cracker with the humidity adsorbent increased. After 30 days of humidity testing time, only the water activity value increased. Considering all the studied parameters, the humidity adsorbent from the cockleshells can maintain the quality of fried fish crackers for at least 90 days.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Science, King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi for supporting some experiments in this work.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding is involved.

-

Author contributions: Patcharin Naemchanthara: writing – original draft, data curation, formal analysis, conceptualization, methodology, funding acquisition, resources; Sirikorn Pongtornkulpanich: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software; Surapat Pansumrong: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software; Kanokwan Boonsook: data curation, formal analysis, methodology, investigation; Kridsada Faksawat: data curation, formal analysis, methodology, investigation; Weeranut Kaewwiset: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, software; Pichet Limsuwan: supervision, validation, visualization, writing – review and editing; Kittisakchai Naemchanthara: writing – review and editing, conceptualization, project administration, resources, visualization, and supervision. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Cropotova J, Kvangarsnes K, Aas GH, Tappi S, Rustad T. Chapter 6 – Protein from seafood. In: Tiwari BK, Healy LE, editors. Future proteins. San Diego, CA, US: Academic Press; 2023. p. 107–29.10.1016/B978-0-323-91739-1.00006-4Search in Google Scholar

[2] Pattani Fishery Inspection Office. Annual reports 2023 in Statistical information 2023. Pattani, Thailand: Department of Fisheries; 2024. p. 10–18 (in Thai).Search in Google Scholar

[3] Sridharan J, Aanand S. Shrimp waste - A valuable protein source for aqua feed. AgriCos e-Newsletter. 2022;2:64–7.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Topić PN, Lorencin V, Strunjak-Perović I, Čož-Rakovac R. Shell waste management and utilization: mitigating organic pollution and enhancing sustainability. Appl Sci. 2023;13:623.10.3390/app13010623Search in Google Scholar

[5] Office of The Permanent Secretary for Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. Report on the monitoring and evaluation of the community wastewater treatment system and the community waste disposal system in Chapter 2 Wastewater and solid waste situation in each of the provinces. Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, Songkhla, Thailand; p. 5–6 (in Thai).Search in Google Scholar

[6] Global Waste Management Outlook 2024 – Beyond an age of waste: Turning rubbish into a resource. Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Environment Programme; 2024.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Aroonsrimorakot S, Laiphrakpam M, Paisantanakij W. Impacts of green office projects in Thailand: an evaluation consistent with sustainable development goals (SDGs). J Sustain Dev. 2020;13:164.10.5539/jsd.v13n4p164Search in Google Scholar

[8] Abouzied AS, Amin HF, Ibrahim SM. Quality and safety determination of blood cockle (Tegillarca granosa) Meat, Alexandria, Egypt. Egypt J Aquat Biol Fish. 2022;26:1039–54.10.21608/ejabf.2022.278975Search in Google Scholar

[9] Department of Fisheries. Statistic of marine shellfish culture survey. Department of Fisheries, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives. Bangkok, Thailand; 2010. p. 27 (in Thai).Search in Google Scholar

[10] Mohamed M, Yousuf S, Maitra S. Decomposition study of calcium carbonate in cockle shell. J Eng Sci Technol. 2012;7:1–10.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Lu J, Lu Z, Li X, Xu H, Li X. Recycling of shell wastes into nanosized calcium carbonate powders with different phase compositions. J Clean Prod. 2015;92:223–9.10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.12.093Search in Google Scholar

[12] Boonsook K, Limsuwan P, Naemchanthara K, Naemchanthara P. Development of eggshell waste incorporated with a porous host as a humidity adsorption material. J Wuhan Univ Technol, Mater Sci Ed. 2023;38:974–83.10.1007/s11595-023-2785-2Search in Google Scholar

[13] Pongtonglor P, Hoonnivathana E, Limsuwan P, Limsuwan S, Naemchanthara K. Utilization of waste eggshells as humidity adsorbent. J Appl Sci. 2011;11:3659–62.10.3923/jas.2011.3659.3662Search in Google Scholar

[14] Rattanachoung N, Pankaew P, Hoonnivathana E, Suttisiri N, Limsuwan P, Naemchanthara K. Performance study of humidity adsorbent prepared from waste shells. In the 2nd International Conference on Key Engineering Materials, ICKEM. Advanced Materials Research; 2012. p. 154–58.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.488-489.154Search in Google Scholar

[15] Kingwascharapong P, Paewpisakul P, Sripoovieng W, Sanprasert S, Pongsetkul J, Meethong R, et al. Development of fish snack (Keropok) with sodium reduction using alternative salts (KCl and CaCl2). Future Foods. 2024;9:100285.10.1016/j.fufo.2023.100285Search in Google Scholar

[16] Chaimongkol L, Kaewmanee T, Boonkamnerd S. Good manufacturing practices, production data and quality of fish cracker produced in Pattani province. Pattani, Thailand: Prince of Songkla University; 2013. p. 1–3.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Ibadullah WZW, Idris AA, Shukri R, Mustapha NA, Saari N, Abedin NHZ. Stability of fried fish crackers as influenced by packaging material and storage temperatures. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci. 2019;7:369–81.10.12944/CRNFSJ.7.2.07Search in Google Scholar

[18] Maisont S, Samutsri W, Phae-ngam W, Limsuwan P. Development and Characterization of Crackers Substitution of Wheat Flour With Jellyfish. Front Nutr. 2021;8:772220.10.3389/fnut.2021.772220Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Reid DS. Water Activity: Fundamentals and relationships. Water activity in foods. Asia, Carlton, Australia: Blackwell Publishing; 2007. p. 15–28.10.1002/9780470376454.ch2Search in Google Scholar

[20] Tarladgis BG, Watts BM, Younathan MT, Dugan Jr L. A distillation method for the quantitative determination of malonaldehyde in rancid foods. JAOCS. 1960;37:44–8.10.1007/BF02630824Search in Google Scholar

[21] Chakrabarty D, Mahapatra S. Aragonite crystals with unconventional morphologies. J Mater Chem. 1999;9:2953–57.10.1039/a905407cSearch in Google Scholar

[22] Geng J, Tang X, Xu J. Calcium oxide addition and ultrasonic pretreatment-assisted hydrothermal carbonization of granatum for adsorption of lead. Green Process Synth. 2022;11:338–44.10.1515/gps-2022-0037Search in Google Scholar

[23] Nayeem A, Mizi F, Ali MF, Shariffuddin JH. Utilization of cockle shell powder as an adsorbent to remove phosphorus-containing wastewater. Environ Res. 2023;216:114514.10.1016/j.envres.2022.114514Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Borkowski G, Martyła A, Dobrosielska M, Marciniak P, Głowacka J, Pakuła D, et al. Characterisation of carbonate lake sediments as a potential filler for polymer composites. Green Process Synth. 2023;12:20228082.10.1515/gps-2022-8082Search in Google Scholar

[25] Habte L, Shiferaw N, Mulatu D, Thenepalli T, Chilakala R, Ahn JW. Synthesis of nano-calcium oxide from waste eggshell by sol–gel method. Sustainability. 2019;11:3196.10.3390/su11113196Search in Google Scholar

[26] Buasri A, Loryuenyong V. The new green catalysts derived from waste razor and surf clam shells for biodiesel production in a continuous reactor. Green Process Synth. 2015;4:389–97.10.1515/gps-2015-0047Search in Google Scholar

[27] Silva C, Bobillier F, Canales D, Antonella Sepúlveda F, Cament A, Amigo N, et al. Mechanical and antimicrobial polyethylene composites with CaO nanoparticles. Polymers. 2020;12:2132.10.3390/polym12092132Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Miura K, Mae K, Li W, Kusakawa T, Morozumi F, Kumano A. Estimation of hydrogen bond distribution in coal through the analysis of OH stretching bands in diffuse reflectance infrared spectrum measured by in-situ technique. Energy Fuels. 2001;15:599–610.10.1021/ef0001787Search in Google Scholar

[29] Colnago LRL, Santos AKV, dos Santos Potensa B, Chaves FP, de Almeida Santos GT, de Souza AE, et al. Preparation and characterization of geopolymers obtained from alkaline activated hollow brick waste. Mater Res. 2024;27:e20240203.10.1590/1980-5373-mr-2024-0203Search in Google Scholar

[30] Cizer O, Rodriguez-Navarro C, Ruiz-Agudo E, Elsen J, Van Gemert D, Van Balen K. Phase and morphology evolution of calcium carbonate precipitated by carbonation of hydrated lime. J Mater Sci. 2012;47:6151–65.10.1007/s10853-012-6535-7Search in Google Scholar

[31] Ma W, Zhu G, Guan X, Yan K, Li H, Meng Z, et al. An innovative approach to prepare calcium oxide from calcium carbide slag based on sequential mineral transformation. ACS SRM. 2024;1:1279–90.10.1021/acssusresmgt.4c00164Search in Google Scholar

[32] Blamey J, Zhao M, Manovic V, Anthony EJ, Dugwell DR, Fennell PS. A shrinking core model for steam hydration of CaO-based sorbents cycled for CO2 capture. Chem Eng J. 2016;291:298–305.10.1016/j.cej.2016.01.086Search in Google Scholar

[33] Louër D. Powder x-ray diffraction, applications. In: Lindon JC, Tranter GE, Koppenaal DW, editors. Encyclopedia of spectroscopy and spectrometry. 3rd edn. Oxford: Academic Press; 2017. p. 723–31.10.1016/B978-0-12-803224-4.00257-0Search in Google Scholar

[34] Mirghiasi Z, Bakhtiari F, Darezereshki E, Esmaeilzadeh E. Preparation and characterization of CaO nanoparticles from Ca(OH)2 by direct thermal decomposition method. J Ind Eng Chem. 2014;20:113–7.10.1016/j.jiec.2013.04.018Search in Google Scholar

[35] Wang S, Han L, Meng Q, Jin Y, Zhao W. Investigation of pore structure and water imbibition behavior of weakly cemented silty mudstone. Adv Civ Eng. 2019;2019(1):1–13.10.1155/2019/8360924Search in Google Scholar

[36] Thilagashanthi T, Gunasekaran K, Satyanarayanan KS. Microstructural pore analysis using SEM and ImageJ on the absorption of treated coconut shell aggregate. J Clean Prod. 2021;324:129217.10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129217Search in Google Scholar

[37] Faksawat K, Limsuwan P, Naemchanthara K. 3D printing technique of specific bone shape based on raw clay using hydroxyapatite as an additive material. Appl Clay Sci. 2021;214:106269.10.1016/j.clay.2021.106269Search in Google Scholar

[38] Fontana AJ, Carter BP. Measurement of water activity, moisture sorption isotherm, and moisture content of foods. Water activity in foods; 2020. p. 207–26.10.1002/9781118765982.ch8Search in Google Scholar

[39] Luyten H J, Plijter J, Van Vliet T. Crispy/crunchy crusts of cellular solid foods: a literature review with discussion. J Texture Stud. 2004;35:445–92.10.1111/j.1745-4603.2004.35501.xSearch in Google Scholar

[40] Nilsuwan K, Benjakul S, Prodpran T. Quality changes of shrimp cracker covered with fish gelatin film without and with palm oil incorporated during storage. Int Aquat Res. 2016;8:227–38.10.1007/s40071-016-0138-xSearch in Google Scholar

[41] Moula Ali AM, Caba KDL, Prodpran T, Benjakul S. Quality characteristics of fried fish crackers packaged in gelatin bags: Effect of squalene and storage time. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;99:105378.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.105378Search in Google Scholar

[42] Shamberger RJ, Shamberger BA, Willis CE. Malonaldehyde content of food. J Nutr. 1977;107:1404–9.10.1093/jn/107.8.1404Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Klamklomjit S, Wooti C, Leelahapongstom A. The product development of riceberry cookie stuffed with pineapple. Burapha Sci J. 2022;27:1357–74.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Tanikawa E, Motohiro T, Akiba M. Marine Products in Japan. Koseisha Koseikaku: Size, Technology and Research; 1985.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”