Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

-

Abdulaziz Alangari

, Mukesh Goel

and Kirtanjot Kaur

Abstract

This study presents a sustainable method for producing iron oxide nanoparticles (FeO NPs) using aqueous extracts from coffee seeds. Characterization through X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy, and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed non-spherical NPs ranging from 30 to 50 nm. The XRD analysis confirmed that the face-centred cubic structure and the Debye–Scherrer’s crystalline size support the FeO particle size confirmed from TEM. The synthesized NPs demonstrated significant antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus, as well as antifungal activity against Aspergillus niger. Additionally, they exhibited potent antioxidant properties, effectively inhibiting DPPH, α-amylase, and α-glucosidase compared to acarbose and coffee extract. The findings suggest that these FeO NPs hold promise as antimicrobial, antioxidant, antifungal, and potentially antidiabetic agents.

1 Introduction

Nanotechnology is the ground-breaking technique that comprises managing molecules at the level of nanoscale. The field has become exciting for modern technology as it makes particles of different sizes, chemical properties, textures, dimensions, and shapes. All these products have different properties and applications. The properties of nanoparticles (NPs) differ from their bulk counterparts as a result of their size. Materials at the nanoscale have been extremely progressive in terms of knowledge and applications [1,2,3]. NPs fall into three main categories based on their composition: metallic, ceramic, and polymeric. Metallic NPs find applications in diverse fields like textiles, food, agriculture, health, and cosmetics. Their small size grants them a high surface area-to-volume ratio, significantly influencing their physical and chemical properties [4]. This alteration enhances their potential utility across various applications, owing to the improvements in their properties [5].

Iron oxide (FeO) NPs are the simplest and smallest particles of iron and they display high surface area and reactivity. These particles are not toxic in nature and display exceptional stability in terms of dimensions. FeO NPs have great electrical and thermal stabilities and have a good magnetic effect [6]. On oxidation of FeO by exposure to air and water, free ions of Fe are produced. FeO NPs can be used for various applications such as drug delivery, separation, dye adsorption, photocatalysis, imaging, etc. [7,8]. NPs of FeO have been recognized to play a major role as conducting materials. Due to these unique and attractive properties, a lot of research has been carried out on fabricating FeO NPs. Recently, methods such as sol–gel, chemical precipitation, flow injection, ultrasonic, electro-chemical, and hydrothermal have been developed for the synthesis of FeO NPs [9]. The structure and morphology of FeO is very important for predicting the properties of FeO NPs in terms of applications [10]. Hence, the designing of NPs with different structures is significant. A lot of research has been dedicated to the synthesis of FeO NPs with different morphologies, structures, and forms such as nano-sheets, nano-rods, and nano-particles. However, these methods are expensive, energy-intensive, toxic, and need extreme conditions for operations. Therefore, biological methods for the synthesis of FeO NPs have been recognized to be fast, stable, environmentally viable, efficient, and cost-effective [11,12,13,14].

Synthesis of NPs in a biological way includes the use of plants and microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi as reducing agents. However, due to the ease of handling plants, they have been receiving additional research attention. Green synthesis by use of plant-based sources involves the use of different parts of plants such as roots, stems, leaves, flowers, fruits, and seeds [14,15,16]. The NPs synthesized from plants are more stable in comparison to the NPs synthesized from microorganisms. Plants have several organic reducing agents that occur naturally which it simpler to produce NPs [17]. The relationship between plants and nanotechnology is referred to as green nanotechnology. There is a symbiotic relationship between plant science and nanotechnology as phytochemicals from plants are utilized for synthesizing NPs [18].

Coffee is ranked as the second product after petroleum that is being traded in the world. Coffee possesses various bioactive constituents such as phenols, flavonoids, steroids, alkaloids, saponins, and polysaccharides. These bioactive elements are termed phytochemicals of plants. Phytochemicals are present in coffee seeds (CSs) and they can be extracted and used as reducing agents as well as capping agents for the synthesis of FeO NPs. They play a critical role in converting the ions of iron to atoms of iron by depicting the building blocks of FeO NPs. Some of the most common micro-organisms that are pathogenic to humans are Escherichia coli (E. coli), Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), and Aspergillus niger (A. niger). A few strains of S. aureus are capable of resisting antibiotics like penicillin, vancomycin, methicillin, erythromycin, and tetracycline [19]. In this view, the NPs of FeO have shown anti-microbial potential in combating pathogens. Also, FeO NPs were reported to have good activity against several pathogenic micro-organisms such as fungi and bacteria due to their ability to produce reactive oxygen species [20].

In this study, we have reported the synthesis of FeO NPs from the aqueous extract of CSs for the first time and tested their efficiency in inhibiting the growth of micro-organisms such as E. coli, S. aureus, and fungi A. niger. The particles were characterized to analyse the structures, morphology, and various other properties to understand their applications in diverse sectors. The biological activity of FeO NPs such as anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, and anti-fungal activities were carried out.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

High purity ferrous sulphate heptahydrate (FeSO4·7H2O) was obtained from Rankem private limited, Mumbai, India, while CSs were obtained from standard dealers. Nutrient agar medium (NAM), potato dextrose agar (PDA), and acarbose were procured from Himedia. Triple distilled water was used throughout the reaction.

2.2 Preparation of CS extract

The commercially available coffee powder (10 g) was added to 100 mL of distilled water and boiled for 15 min at 70°C. Then, the extract was filtered by Whatman filter paper No. 42 and stored at 4–5°C for further investigation. Further, filter extract was used in the synthesis of FeO NPs.

2.3 Preparation of green FeO NPs

Green synthesis of FeO NPs was carried out with the coffee extract (100 mL) by heating to 40–60°C with continuous stirring using a magnetic stirrer. When the temperature of the extract reached 50°C, 150 mM of FeSO4·7H2O and 1 M NaOH solution were added and left for about 2 h till a brownish-black precipitate appeared [21]. Now this solution was cooled at room temperature and centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 10 min with the help of centrifuge tubes. After centrifugation, it was washed three times with distilled water and once with ethanol. After washing, the pellets were dried at 100°C. Afterward, the collected particles were transferred to a ceramic crucible cup and heated in a furnace at 500°C for 2 h, and ground into powder with a mortar and pestle. The resultant brown powder is stored in an airtight container for characterization.

2.4 Microorganisms and culture conditions

Microbial cultures were prepared on potato dextrose agar plates and stored at 4°C, while the stock was grown in the dark at 25°C in PDA for 7 days. A growth medium was prepared for use by mixing 80 g of glucose and fresh potato (500 mL) in 3.5 L of distilled water. Fresh potatoes were prepared by dicing 1 kg of potatoes and boiling them in 2 L of distilled water for 30 min. The medium was thus dispensed into 80 beakers with a capacity of 350 mL (50 mL per cup) and autoclaved at 121°C for 30 min. Inoculate vials with fresh microbial samples grown in PDA medium in Petri dishes for 7 days at 28°C. After 10 days of incubation under normal conditions (25°C), the culture media is filtered through filter paper to separate the filtrate and mycelium. The vaccine was shaken with ethyl acetate at 250 rpm for 20 min at room temperature. The extract is filtered and concentrated under vacuum at 40°C with a field evaporator to give a brown product (2 g).

2.5 Preparation of antibacterial assay

The method used to analyse antibacterial activity is a Well diffusion test on NAM [22]. This medium is poured aseptically into a Petri dish and left for 1 h to solidify. After that, fresh overnight cultures of E. coli and S. aureus (100 µg·mL−1) were exposed to nutrient-rich agar using a vacuum and left in the plate for 15–20 min to absorb all bacteria. The wells were prepared by gel puncture (7–8 mm) under sterile conditions. The FeO NPs sample was placed in the well at different concentrations: 50, 100, and 150 µg·mL−1. Plates were placed at room temperature for 30 min to allow the extract to disperse, then incubated at 37°C for 24 h to allow microbial growth. Antibody-containing materials inhibit the growth of bacteria after incubation by revealing a clear zone of inhibition (ZOI) around the well.

2.6 DPPH radical-scavenging activity

The radical scavenging activity of FeO NPs was measured according to their hydrogen donating ability or radical scavenging ability using stable radical DPPH. A solution of DPPH in ethanol (0.1 mM) was prepared and 1.0 mL of this solution was added to 2.0 mL of FeO NP at different concentrations (20–100 µg·mL−1). Thirty minutes later, absorbance was measured at 517 nm. Ascorbic acid was used as a positive control. The low absorbance of the reaction mixture indicates greater free radical scavenging activity [23,24]. Free radical scavenging activity is expressed as the percentage inhibition of free radicals by the sample and the formula for the same is

where

2.7 Alpha-amylase inhibition test

Inhibition testing was done using the DNSA method [25]. The solution contains α-amylase solution (1 U·mL−1) at a concentration of 20 µg·mL−1 and 500 µL of 0.02 M sodium phosphate buffer (containing 6 mM NaCl, pH 6.9) with FeO NPs. The first incubation of the mixture was done at 37°C for 20 min.

After incubation, add 250 µL of 1% starch solution to the above buffer and incubate at 37°C for 15 min. Add 1 mL of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent to quench the reaction and then incubate in a boiling water bath for 10 min. Cool the tube and measure the absorbance at 540 nm. The reference sample contains all other reagents and enzymes except the test sample. Alpha-amylase inhibitory activity is expressed as percentage of inhibition.

Alpha-amylase inhibitory activity was calculated according to the following equation:

where

2.8 Alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity

Alpha-glucosidase inhibition was determined according to the standard method [26]. The analytical mix contains 150 mL of 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (containing 6 mM NaCl, pH 6.9) at a concentration of 20–410 mg mPL, 0.1 unit of α-glucosidase, and FeO NPs. Pre-incubate the mix at 37°C for 10 min. After incubation, add 50 µL of 2 mM p-nitrophenyl-α-d-glucopyranoside to 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer and incubate at 37°C for 20 min. Stop the reaction by adding 50 µL of 0.1 M sodium carbonate (Na2CO3). Measure the absorbance at 405 nm. Tubes containing α-glucosidase but no FeO NPs were controlled with 100% enzyme activity and acarbose positive control.

where

2.9 Instrumentation

UV-Vis absorption spectra were obtained by Shimadzu 1900i at a wavelength of 200–800 nm. X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectra were recorded on a Bruker AXS D8 Advanced using Cuα radiation and Si(Li) position sensitive detector with a wavelength of 5,406 Å was used. Anton Paar TTK 450 accessory was added at 170°C–450°C. Features were obtained using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) JEOL Model JSM-6390LV. Resolution: 0.23 nm, lattice: 0.14 nm, 14 nm, 2,000× 1,500,000× magnification. Size and shape of the NPs were investigated using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) JEM 2100 plus, JEOL, Japan equipment.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 UV analysis

UV-Vis analysis was performed to confirm FeO synthesis by absorption spectroscopy and understand the optical nature. The UV-Vis absorption spectrum of FeO NPs is depicted in Figure 1 and the absorption spectra shows an absorption band at 293 nm which corresponds to the biomolecules. The strong and intense band at 293 nm represents the abundance of the biomolecules on the surface of the FeO NPs. The band at 293 nm is noticed to be broad and the broadening of the peak is just due to the presence of FeO NPs which extends beyond 500 nm [27].

UV-Visible absorption spectra of as synthesized FeO NPs.

3.2 Structure and composition of FeO NPs

The XRD pattern of FeO NPs synthesized with coffee extract is presented in Figure 2. The examination revealed diffraction peaks at 32°, 35°, 38°, 55°, and 65°, these peaks indicated the formation of FeO NPs and is in good agreement with the literature (JCPDS 86-2316) [28]. The sharp and intense peaks revealed the NPs which were obtained from CSs having crystalline nature and Face centred cubic structure [29]. The XRD pattern confirms the formation of FeO NPs. FeO possesses a nonstoichiometric FexO configuration with an x value ranging from 0.83 to 0.96, alongside ordered Fe vacancies. This arrangement exhibits low chemical stability and may degrade into α-Fe. But in this study, the synthesized FeO is found to be stable and not prone to oxidation as suggested in the literature and our observations are in agreement with other similar works [30]. Debye–Scherrer formula is one of the most widely used formulas to estimate the crystallite size of NPs [31,32]. In this study, the Debye–Scherrer formula was used to estimate the average size of crystals and the average size of crystals were seen to be 36 nm. The interlayer spacing (d) is found to be 0.2732 nm and dislocation density (δ) is calculated to be 0.02739 × 10−14 lines·m−2. The strain (ε) is found to be 4.26 × 10−3 and the peak broadening is due to the addition of the lattice strain [33].

XRD analysis of FeO NPs synthesized from aqueous extract of CSs.

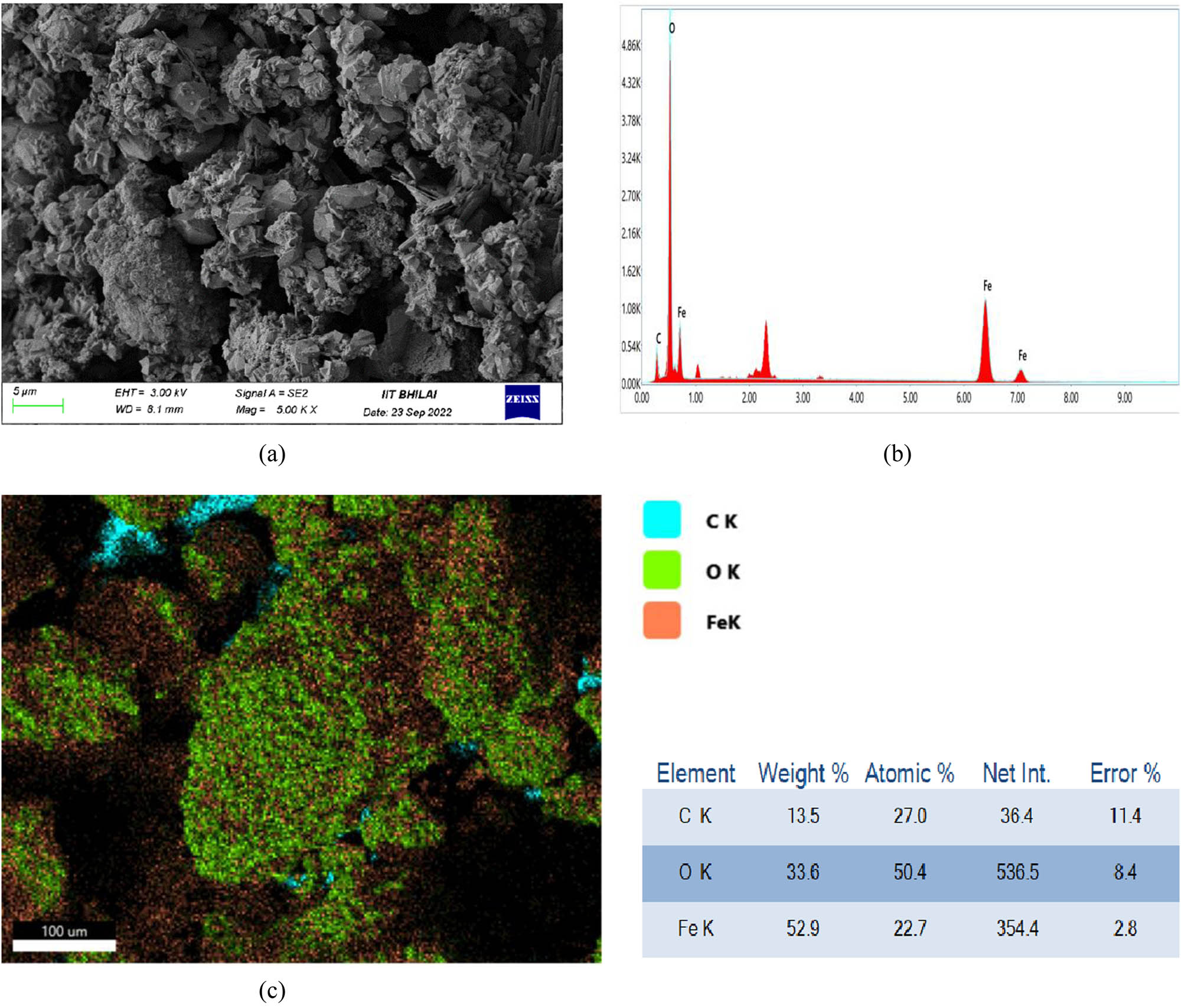

3.3 Morphology

The NPs extracted from CSs were analysed by SEM to study the morphology of NPs. The results of SEM and EDAX analysis are presented in Figure 3(a–c). It can be observed that the NPs synthesized had agglomerates and were non-uniform in nature and appearance. The sizes of the particles were 20–50 nm approximately. The agglomerates were due to the buildup building blocks due to activities of reducing and capping agents of the coffee extract due to the magnetic activity [34,35,36].

(a) SEM micrographs, (b) EDAX analysis, and (c) elemental analysis of FeO NPs prepared from CSs aqueous extract.

The analysis of the elemental configuration was carried out by EDAX analysis. The results are presented in Figure 3b. It can be clearly seen that the peaks of Fe were observed at 6–7 keV, also the peaks at 0.5 and 0.7 keV showed the presence of C and O, respectively. These results were similar to the work reported by Sadasivam et al. [37]. The existence of carbon is due to the carbon available in the plant extract. The elemental analysis of the FeO NP is seen in Figure 3c. The distribution of Fe, C, and O and their amounts in percentage can be seen in Figure 3c.

The TEM analysis of FeO NPs was performed and the images are presented in Figure 4. It is noticed that the FeO NPs are at the nanoscale level and found to be less than 50 nm in scale as observed from the SEM and XRD analysis. The shapes of the NPs are observed to be non-spherical with irregularities and this might be due to the presence of various biomolecules acting as capping agents. However, the NPs are found to be agglomerated as seen in Figure 4 and this might be due to the interaction of biomolecules of coffee extract acting as building blocks of the FeO NPs.

TEM images of FeO NPs prepared with coffee aqueous extract.

3.4 HPLC analysis of CSs

Reverse phase HPLC was performed for the coffee extract to understand the number of biomolecules present in the extract which can help in determining the molecules responsible for reduction and capping of the FeO NPs. The HPLC chromatogram is presented in Figure 5 and it can be seen that there are six peaks and two peaks are major suggesting that these two molecules are present majorly in the extract. Each peak at different retention times represents a type of molecule. These observations conclude that the coffee extract contains various biomolecules and these biomolecules can cap and stabilize the FeO NPs formations.

HPLC chromatogram of aqueous extract of CSs (C18 column, mobile phase: 70% ACN and 30% H2O).

3.5 Antimicrobial activity of FeO NPs

The antibacterial activity of the FeO NPs synthesized using aqueous extract of coffee seeds was evaluated against bacteria E. coli, and S. aureus and it was observed that FeO NPs exhibited a good antimicrobial activity compared to the coffee aqueous extract. The antimicrobial activity is due to the interaction of the NPs onto the cell wall of the bacterial strains. However, the ZOI of standard Streptomycin and Vancomycin were found to be high compared to the FeO NPs suggesting that the FeO NPs are moderate and good microbial agents.

3.6 Antifungal activity of FeO NPs

The antifungal activities of the FeO NPs synthesized by green synthesis with different concentrations against fungus A. niger are presented in Figure 6. It can be clearly seen from Figure 6 that the FeO NPs displayed good antifungal activities against A. niger owing to its size and deposition on the fungus.

Antifungal activity of A. niger in the presence of FeO NPs prepared from CS extract.

3.7 Antioxidant activity

Antioxidants have been recognized in their work against oxidative damage and have been associated with a reduced risk of chronic disease. Figure 7 shows the DPPH radical scavenging activity of FeO NPs at concentrations of 20–100 µg·mL−1 compared to standard (acarbose) and coffee bean extract. IC50 values of FeO NPs were higher compared to acarbose acid and coffee bean extract. The results showed that the free radical scavenging of FeO NPs slightly increased with the dosage. This result is consistent with the DPPH activity of FeO NPs reported in the literature [38,39,40].

DPPH inhibition activity of acarbose, CS extract, and FeO NPs.

3.8 Inhibition of α-amylase and α-glucosidase by FeO NPs

Carbohydrate-digesting enzymes such as pancreatic α-amylase and intestinal α-glucosidase are responsible for breaking down oligosaccharides and disaccharides into monosaccharides suitable for absorption. Inhibiting two digestive enzymes is particularly useful in the treatment of non-insulin diabetes, as it slows the release of sugar from the blood. As shown in Figures 8 and 9, the results showed that α-amylase and α-glucosidase were significantly affected in a concentration-dependent manner after incubation with different FeO NP concentrations. As the concentration of FeO NPs increased, the level of enzyme activity decreased significantly. It can be seen from Figures 8 and 9 that the IC 50 values for amylase and α-glucosidase of FeO NPs were similar to those obtained in previous reports.

α-Amylase inhibition activity of acarbose, CS extract, and FeO NPs.

α-Glucosidase inhibition activity of acarbose, CS extract, and FeO NPs.

According to many in vivo studies, inhibition of α-amylase and α-glucosidase is considered one of the most effective treatments for diabetes.

4 Conclusion

As NPs exhibit many attractive properties and functions in many applications, the study of NP synthesis method has recently become a major area of interest in science and engineering. Biosynthesis of FeO NPs using green sources is an effective method due to its simplicity, environmental protection, and cost. In this study, FeO NPs were successfully produced by bioreducing ferric chloride solution using CS aqueous extract. This is evidenced by UV-Vis spectroscopic analysis, which shows a broad absorption peak at 293 nm. The XRD, SEM, and TEM investigations propounds that the size of the FeO NPs are between 20 and 50 nm in range with non-spherical shape. The synthesized FeO NPs also exhibited potent antibacterial activity against pathogenic bacteria whose MICs inhibited the growth of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. The antioxidant activity of the synthesized FeO was analysed and it was seen that the FeO NPs had excellent inhibiting activity against DPPH, α-amylase, and α-glucosidase in comparison with acarbose and coffee extract. The results conclude that the FeO NPs synthesized via green synthesis using aqueous extract of CSs found to have versatile biological significance and further investigations is required to incorporate the FeO NPs in the pharmaceutical formulations.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2024R739) at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Funding information: This research was funded by King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (RSPD2024R739).

-

Author contributions: Abdulaziz Alangari: formal analysis and visualization; Mohammed S Alqahtani: formal analysis, methodology, and resources; Mudassar Shahid: project administration and original draft writing; Rabbani Syed: writing and reviewing and validation; Mukesh Goel: visualization and editing; R. Lakshmipathy: writing – reviewing and editing; Kirtanjot Kaur: formal analysis.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Moradnia F, Fardood ST, Ramazani A, Osali S, Abdolmaleki I. Green sol–gel synthesis of CoMnCrO4 spinel nanoparticles and their photocatalytic application. Micro Nano Lett. 2020;15(10):674–7. 10.1049/mnl.2020.0189.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Elakkiya GT, Balaji GL, Padhy H, Lakshmipathy R. Synthesis of silver nanoplates using regenerated watermelon rind and their application. Mater Today:-Proc. 2022;55(2):240–5. 10.1016/j.matpr.2021.06.370.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Saeid TF, Farzaneh M, Reza F, Rouzbeh A, Salman J, Ali R, Mika S. Facile green synthesis, characterization and visible light photocatalytic activity of MgFe2O4@CoCr2O4 magnetic nanocomposite. J Photoch Photobio A. 2022;423:113621. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2021.11362.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Taghavi FS, Ramazani A, Asiabi PA. A novel green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using a henna extract powder. J Struct Chem. 2018;59:1737–43. 10.1134/S0022476618070302.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Andal V, Buvaneswari G, Lakshmipathy R. Synthesis of CuAl2O4 nanoparticle and its conversion to CuO nanorods. J Nanomater. 2021;2021:8082522. 10.1155/2021/8082522.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Vasantharaj S, Selvam S, Mythili S, Palanisamy S, Kavitha G, Muthiah S, et al. Synthesis of ecofriendly copper oxide nanoparticles for fabrication over textile fabrics: Characterization of antibacterial activity and dye degradation potential. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2019;191:143–9. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.12.026.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Mohsen B, Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh A. Effect of supporting and hybridizing of FeO and ZnO semiconductors onto an Iranian clinoptilolite nano-particles and the effect of ZnO/FeO ratio in the solar photodegradation of fish ponds waste water. Mat Sci Semicon Proc. 2014;27:833–40. 10.1016/j.mssp.2014.08.030.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Zarifeh-Alsadat M, Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh A. Removal of phenol content of an industrial wastewater via a heterogeneous photodegradation process using supported FeO onto nanoparticles of Iranian clinoptilolite. Des Water Treat. 2016;57:16483–94. 10.1080/19443994.2015.1087881.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Moradnia F, Fardood ST, Ramazani A. Green synthesis and characterization of NiFe2O4@ZnMn2O4 magnetic nanocomposites: An efficient and reusable spinel nanocatalyst for the synthesis of tetrahydropyrimidine and polyhydroquinoline derivatives under microwave irradiation. Appl Organomet Chem. 2024;38(3):e7315. 10.1002/aoc.7315.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Abbas N, Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh A. Preparation, characterization, and investigation of the catalytic property of α-Fe2O3-ZnO nanoparticles in the photodegradation and mineralization of methylene blue. Chem Phy Lett. 2020;752:137587. 10.1016/j.cplett.2020.137587.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Vasantharaj S, Sathiyavimal S, Senthilkumar P, Lewis Oscar F, Pugazhendhi A. Biosynthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using leaf extract of Ruellia tuberosa: Antimicrobial properties and their applications in photocatalytic degradation. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 2019;192:74–82. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.12.025.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Sathiyavimal S, Seerangaraj V, Veerasamy V, Mythili S, Govindaraju R, Thamaraiselvi K, et al. Green chemistry route of biosynthesized copper oxide nanoparticles using Psidium guajava leaf extract and their antibacterial activity and effective removal of industrial dyes. J Environ Chem Eng. 2021;9:105033. 10.1016/j.jece.2021.105033.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Saif S, Tahir A, Chen Y. Green synthesis of iron nanoparticles and their environmental applications and implications. Nanomater. 2016;6:209. 10.3390/nano6110209.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Kalaiarasi R, Jayallakshmi N, Venkatachalam P. Phytosynthesis of nanoparticles and its applications. plant cell biotechnol. Mol Biol. 2010;11:1–16. 10.5555/20133284851.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Shukla R, Chanda N, Katti KK, Katti KV. Green nanotechnology – A sustainable approach in the nanorevolution. In Sustainable preparation of metal nanoparticles: Methods and application. RSC Publishing; 2012. p. 144–56.10.1039/9781849735469-00144Search in Google Scholar

[16] Vayalil PK. Date fruits (Phoenix dactylifera Linn): An emerging medicinal food. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2012;52:249–71. 10.1080/10408398.2010.499824.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Taleb H, Maddocks SE, Morris RK, Kanekanian AD. Chemical characterisation and the anti-infammatory, anti-angiogenic and antibacterial properties of date fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.). J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;194:457–68. 10.1016/j.jep.2016.10.032.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Al Harthi S, Mavazhe A, Al Mahroqi H, Khan SA. Quantifcation of phenolic compounds, evaluation of physicochemical properties and antioxidant activity of four date (Phoenix dactylifera L.) varieties of Oman. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2015;10:346–52. 10.1016/j.jtumed.2014.12.006.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Yasin BR, El-Fawal HA, Mousa SA. Date (Phoenix dactylifera) polyphenolics and other bioactive compounds: A traditional islamic remedy’s potential in prevention of cell damage, cancer therapeutics and beyond. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:30075–90. 10.3390/ijms161226210.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Al-Daihan S, Bhat RS. Antibacterial activities of extracts of leaf, fruit, seed and bark of Phoenix dactylifera. Afr J Biotechnol. 2012;11:10021–5. 10.5897/AJB11.4309.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Lakshminarayanan S, Shereen MF, Niraimathi KL, Brindha P, Arumugam A. One-pot green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles from Bauhinia tomentosa: Characterization and application towards synthesis of 1, 3 diolein. Sci Rep. 2021;11:8643. 10.1038/s41598-021-87960-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Shamaila S, Zafar N, Riaz S, Sharif R, Nazir J, Naseem S. Gold nanoparticles: an efficient antimicrobial agent against enteric bacterial human pathogen. Nanomaterials. 2016;6(4):71. 10.3390/nano6040071.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Pankhurst QA, Connolly J, Jones S, Dobson J. Applications of magnetic nanoparticles in biomedicine. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2003;36:R167. 10.1088/0022-3727/36/13/201.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Kavitha K, Baker S, Rakshith D, Kavith H, Harini BP, Satish S. Plants as green source towards synthesis of nanoparticles. Int Res J Biol Sci. 2013;2:66–76.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Jain, A, Jain, R, Jain, S. Quantitative analysis of reducing sugars by 3, 5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNSA Method). Basic Techniques in biochemistry, microbiology and molecular biology. Springer Protocols Handbooks. New York, NY: Humana; 2020.10.1007/978-1-4939-9861-6_43Search in Google Scholar

[26] Dej-adisai S, Rais IR, Wattanapiromsakul C, Pitakbut T. Alpha-glucosidase inhibitory assay-screened isolation and molecular docking model from Bauhinia pulla active compounds. Molecules. 2021;26:5970. 10.3390/molecules26195970.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Karpagavinayagam P, Vedhi C. Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using Avicennia marina flower extract. Vacuum. 2019;160:286–92. 10.1016/j.vacuum.2018.11.043.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Narges A, Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh A. Modification of clinoptilolite nano-particles with iron oxide: Increased composite catalytic activity for photodegradation of cotrimaxazole in aqueous suspension. Mat Sci Semicon Proc. 2015;31:684–92. 10.1016/j.mssp.2014.12.067.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh A, Shirzadi A. Enhancement of the photocatalytic activity of ferrous oxide by doping onto the nano-clinoptilolite particles towards photodegradation of tetracycline. Chemosphere. 2014;107:136–44. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.02.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Shirin G, Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh A. A double-Z-scheme ZnO/AgI/WO3 photocatalyst with high visible light activity: Experimental design and mechanism pathway in the degradation of methylene blue. J Mol Liquid. 2021;322:114563. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.114563.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Fardood TS, Moradnia F, Moradi S, Forootan R, Yekke Zare F, Heidari M. Eco-friendly synthesis and characterization of α-Fe2O3 nanoparticles and study of their photocatalytic activity for degradation of Congo red dye. Nanochem Res. 2019;4(2):140–7. 10.22036/NCR.2019.02.005.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Farzaneh M, Fardood TS, Ali R, Gupta VK. Green synthesis of recyclable MgFeCrO4 spinel nanoparticles for rapid photodegradation of direct black 122 dye. J Photochem Photobiol A. 2020;392:112433. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2020.112433.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Salesi S, Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh A. Boosted photocatalytic effect of binary AgI/Ag2WO4 nanocatalyst: characterization and kinetics study towards ceftriaxone photodegradation. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29:90191–206. 10.1007/s11356-022-22100-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Mukunthan K, Balaji S. Silver nanoparticles shoot up from the root of Daucus carrota (L.). Int J Green Nanotechnol. 2012;4:54–61. 10.1080/19430892.2012.654745.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Herlekar M, Barve S, Kumar R. Plant-mediated green synthesis of iron nanoparticles. J Nanopart. 2014;2014:140614. 10.1155/2014/140614.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Fazlzadeh M, Rahmani K, Ahmad Z, Hossein A, Nasiri F, Khosravi R. A novel green synthesis of zero valent iron nanoparticles (NZVI) using three plant extracts and their efficient application for removal of Cr (VI) from aqueous solutions. Adv Powder Technol. 2017;28:122–30. 10.1016/j.apt.2016.09.003.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Sadhasivam S, Vinayagam V, Balasubramaniyan M. Recent advancement in biogenic synthesis of iron nanoparticles. J Mol Struct. 2020;1217:128372. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.128372.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Hoag GE, Collins JB, Holcomb JL, Hoag JR, Nadagouda MN, Varma RS. Degradation of bromothymol blue by ‘greener’ nano-scale zero-valent iron synthesized using tea polyphenols. J Mater Chem. 2009;19:8671–7. 10.1039/B909148C.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Kumar KM, Mandal BK, Kumar KS, Reddy PS, Sreedhar B. Biobased green method to synthesise palladium and iron nanoparticles using Terminalia chebula aqueous extract. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2013;102:128–33. 10.1016/j.saa.2012.10.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Makarov VV, Makarova SS, Love AJ, Olga VS, et al. Biosynthesis of stable iron oxide nanoparticles in aqueous extracts of Hordeum vulgare and Rumex acetosa plants. Langmuir. 2014;30:5982–8. 10.1021/la5011924.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Green polymer electrolyte and activated charcoal-based supercapacitor for energy harvesting application: Electrochemical characteristics

- Research on the adsorption of Co2+ ions using halloysite clay and the ability to recover them by electrodeposition method

- Simultaneous estimation of ibuprofen, caffeine, and paracetamol in commercial products using a green reverse-phase HPTLC method

- Isolation, screening and optimization of alkaliphilic cellulolytic fungi for production of cellulase

- Functionalized gold nanoparticles coated with bacterial alginate and their antibacterial and anticancer activities

- Comparative analysis of bio-based amino acid surfactants obtained via Diels–Alder reaction of cyclic anhydrides

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles on yellow phosphorus slag and its application in organic coatings

- Exploring antioxidant potential and phenolic compound extraction from Vitis vinifera L. using ultrasound-assisted extraction

- Manganese and copper-coated nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Carica papaya leaf extract induce antimicrobial activity and breast cancer cell death by triggering mitochondrial caspases and p53

- Insight into heating method and Mozafari method as green processing techniques for the synthesis of micro- and nano-drug carriers

- Silicotungstic acid supported on Bi-based MOF-derived metal oxide for photodegradation of organic dyes

- Synthesis and characterization of capsaicin nanoparticles: An attempt to enhance its bioavailability and pharmacological actions

- Synthesis of Lawsonia inermis-encased silver–copper bimetallic nanoparticles with antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activity

- Facile, polyherbal drug-mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles and their potent biological applications

- Zinc oxide-manganese oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose-folic acid-sesamol hybrid nanomaterials: A molecularly targeted strategy for advanced triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Exploring the antimicrobial potential of biogenically synthesized graphene oxide nanoparticles against targeted bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Biofabrication of silver nanoparticles using Uncaria tomentosa L.: Insight into characterization, antibacterial activities combined with antibiotics, and effect on Triticum aestivum germination

- Membrane distillation of synthetic urine for use in space structural habitat systems

- Investigation on mechanical properties of the green synthesis bamboo fiber/eggshell/coconut shell powder-based hybrid biocomposites under NaOH conditions

- Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using endophytic fungal strain to improve the growth, metabolic activities, yield traits, and phenolic compounds content of Nigella sativa L.

- Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from rice and annual upland crops in Red River Delta of Vietnam using the denitrification–decomposition model

- Synthesis of humic acid with the obtaining of potassium humate based on coal waste from the Lenger deposit, Kazakhstan

- Ascorbic acid-mediated selenium nanoparticles as potential antihyperuricemic, antioxidant, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic agents

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Illicium verum extract: Optimization and characterization for biomedical applications

- Antibacterial and dynamical behaviour of silicon nanoparticles influenced sustainable waste flax fibre-reinforced epoxy composite for biomedical application

- Optimising coagulation/flocculation using response surface methodology and application of floc in biofertilisation

- Green synthesis and multifaceted characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles derived from Senna bicapsularis for enhanced in vitro and in vivo biological investigation

- Potent antibacterial nanocomposites from okra mucilage/chitosan/silver nanoparticles for multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium eradication

- Trachyspermum copticum aqueous seed extract-derived silver nanoparticles: Exploration of their structural characterization and comparative antibacterial performance against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

- Microwave-assisted ultrafine silver nanoparticle synthesis using Mitragyna speciosa for antimalarial applications

- Green synthesis and characterisation of spherical structure Ag/Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite using acacia in the presence of neem and tulsi oils

- Green quantitative methods for linagliptin and empagliflozin in dosage forms

- Enhancement efficacy of omeprazole by conjugation with silver nanoparticles as a urease inhibitor

- Residual, sequential extraction, and ecological risk assessment of some metals in ash from municipal solid waste incineration, Vietnam

- Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using the mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) leaf extract: Comparative preliminary in vitro antibacterial study

- Simultaneous determination of lesinurad and febuxostat in commercial fixed-dose combinations using a greener normal-phase HPTLC method

- A greener RP-HPLC method for quaternary estimation of caffeine, paracetamol, levocetirizine, and phenylephrine acquiring AQbD with stability studies

- Optimization of biomass durian peel as a heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production using microwave irradiation

- Thermal treatment impact on the evolution of active phases in layered double hydroxide-based ZnCr photocatalysts: Photodegradation and antibacterial performance

- Preparation of silymarin-loaded zein polysaccharide core–shell nanostructures and evaluation of their biological potentials

- Preparation and characterization of composite-modified PA6 fiber for spectral heating and heat storage applications

- Preparation and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution of bimetallic phosphates (NiFe)2P/NF

- Rod-shaped Mo(vi) trichalcogenide–Mo(vi) oxide decorated on poly(1-H pyrrole) as a promising nanocomposite photoelectrode for green hydrogen generation from sewage water with high efficiency

- Green synthesis and studies on citrus medica leaf extract-mediated Au–ZnO nanocomposites: A sustainable approach for efficient photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye in aqueous media

- Cellulosic materials for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous environments

- The analytical assessment of metal contamination in industrial soils of Saudi Arabia using the inductively coupled plasma technology

- The effect of modified oily sludge on the slurry ability and combustion performance of coal water slurry

- Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier

- Synthesis of EPAN and applications in the encapsulation of potassium humate

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential

- Enhancing mechanical and rheological properties of HDPE films through annealing for eco-friendly agricultural applications

- Immobilisation of catalase purified from mushroom (Hydnum repandum) onto glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan and characterisation: Its application for the removal of hydrogen peroxide from artificial wastewater

- Sodium titanium oxide/zinc oxide (STO/ZnO) photocomposites for efficient dye degradation applications

- Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress

- Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium and silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride filtrate and their impact on Culex pipiens

- Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)

- Assessment of antiproliferative activity of green-synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against glioblastoma cells using Terminalia chebula

- Chlorine-free synthesis of phosphinic derivatives by change in the P-function

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of nanoemulsions based on water-in-olive oil and loaded on biogenic silver nanoparticles

- Study and mechanism of formation of phosphorus production waste in Kazakhstan

- Synthesis and stabilization of anatase form of biomimetic TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing anti-tumor potential

- Microwave-supported one-pot reaction for the synthesis of 5-alkyl/arylidene-2-(morpholin/thiomorpholin-4-yl)-1,3-thiazol-4(5H)-one derivatives over MgO solid base

- Screening the phytochemicals in Perilla leaves and phytosynthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles for potential antioxidant and wound-healing application

- Graphene oxide/chitosan/manganese/folic acid-brucine functionalized nanocomposites show anticancer activity against liver cancer cells

- Nature of serpentinite interactions with low-concentration sulfuric acid solutions

- Multi-objective statistical optimisation utilising response surface methodology to predict engine performance using biofuels from waste plastic oil in CRDi engines

- Microwave-assisted extraction of acetosolv lignin from sugarcane bagasse and electrospinning of lignin/PEO nanofibres for carbon fibre production

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and investigation of cytotoxic activities of selenium nanoparticles utilizing Limosilactobacillus fermentum

- Highly photocatalytic materials based on the decoration of poly(O-chloroaniline) with molybdenum trichalcogenide oxide for green hydrogen generation from Red Sea water

- Highly efficient oil–water separation using superhydrophobic cellulose aerogels derived from corn straw

- Beta-cyclodextrin–Phyllanthus emblica emulsion for zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characteristics and photocatalysis

- Assessment of antimicrobial activity and methyl orange dye removal by Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated silver nanoparticles

- Influential eradication of resistant Salmonella Typhimurium using bioactive nanocomposites from chitosan and radish seed-synthesized nanoselenium

- Antimicrobial activities and neuroprotective potential for Alzheimer’s disease of pure, Mn, Co, and Al-doped ZnO ultra-small nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bauhinia variegata and their biological applications

- Synthesis and optimization of long-chain fatty acids via the oxidation of long-chain fatty alcohols

- Eminent Red Sea water hydrogen generation via a Pb(ii)-iodide/poly(1H-pyrrole) nanocomposite photocathode

- Green synthesis and effective genistein production by fungal β-glucosidase immobilized on Al2O3 nanocrystals synthesized in Cajanus cajan L. (Millsp.) leaf extracts

- Green stability-indicating RP-HPTLC technique for determining croconazole hydrochloride

- Green synthesis of La2O3–LaPO4 nanocomposites using Charybdis natator for DNA binding, cytotoxic, catalytic, and luminescence applications

- Eco-friendly drugs induce cellular changes in colistin-resistant bacteria

- Tangerine fruit peel extract mediated biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles and their potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic assessments

- Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil

- A highly sensitive β-AKBA-Ag-based fluorescent “turn off” chemosensor for rapid detection of abamectin in tomatoes

- Green synthesis and physical characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from the methanol extract of Euphorbia dracunculoides Lam. (Euphorbiaceae) with enhanced biosafe applications

- Detection of morphine and data processing using surface plasmon resonance imaging sensor

- Effects of nanoparticles on the anaerobic digestion properties of sulfamethoxazole-containing chicken manure and analysis of bio-enzymes

- Bromic acid-thiourea synergistic leaching of sulfide gold ore

- Green chemistry approach to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Fagonia Cretica extract, novel strategy for developing antimicrobial and antidiabetic therapies

- Green synthesis and effective utilization of biogenic Al2O3-nanocoupled fungal lipase in the resolution of active homochiral 2-octanol and its immobilization via aluminium oxide nanoparticles

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC approach for simultaneously estimating the promising combination of pentoxifylline and simvastatin in therapeutic potential for breast cancer: Appraisal of greenness, whiteness, and Box–Behnken design

- Use of a humidity adsorbent derived from cockleshell waste in Thai fried fish crackers (Keropok)

- One-pot green synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico study of pyrazole derivatives obtained from chalcones

- Bio-sorption of methylene blue and production of biofuel by brown alga Cystoseira sp. collected from Neom region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis of motexafin gadolinium: A promising radiosensitizer and imaging agent for cancer therapy

- The impact of varying sizes of silver nanoparticles on the induction of cellular damage in Klebsiella pneumoniae involving diverse mechanisms

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles obtained from lemon peel extract

- Rhus microphylla-mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy

- Harnessing trichalcogenide–molybdenum(vi) sulfide and molybdenum(vi) oxide within poly(1-amino-2-mercaptobenzene) frameworks as a photocathode for sustainable green hydrogen production from seawater without sacrificial agents

- Magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2 supported phosphonium ionic liquids for efficient and sustainable transformation of CO2 into oxazolidinones

- A comparative study of Fagonia arabica fabricated silver sulfide nanoparticles (Ag2S) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with distinct antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties

- Visible light photocatalytic degradation and biological activities of Aegle marmelos-mediated cerium oxide nanoparticles

- Physical intrinsic characteristics of spheroidal particles in coal gasification fine slag

- Exploring the effect of tea dust magnetic biochar on agricultural crops grown in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil

- Crosslinked chitosan-modified ultrafiltration membranes for efficient surface water treatment and enhanced anti-fouling performances

- Study on adsorption characteristics of biochars and their modified biochars for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution

- Zein polymer nanocarrier for Ocimum basilicum var. purpurascens extract: Potential biomedical use

- Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo biological screening of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) generated with hydroalcoholic extract of aerial parts of Euphorbia milii

- Novel microwave-based green approach for the synthesis of dual-loaded cyclodextrin nanosponges: Characterization, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics evaluation

- Bi2O3–BiOCl/poly-m-methyl aniline nanocomposite thin film for broad-spectrum light-sensing

- Green synthesis and characterization of CuO/ZnO nanocomposite using Musa acuminata leaf extract for cytotoxic studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCC2998)

- Review Articles

- Materials-based drug delivery approaches: Recent advances and future perspectives

- A review of thermal treatment for bamboo and its composites

- An overview of the role of nanoherbicides in tackling challenges of weed management in wheat: A novel approach

- An updated review on carbon nanomaterials: Types, synthesis, functionalization and applications, degradation and toxicity

- Special Issue: Emerging green nanomaterials for sustainable waste management and biomedical applications

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mature-pseudostem extracts of Alpinia nigra and their bioactivities

- Special Issue: New insights into nanopythotechnology: current trends and future prospects

- Green synthesis of FeO nanoparticles from coffee and its application for antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-oxidation activity

- Dye degradation activity of biogenically synthesized Cu/Fe/Ag trimetallic nanoparticles

- Special Issue: Composites and green composites

- Recent trends and advancements in the utilization of green composites and polymeric nanocarriers for enhancing food quality and sustainable processing

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cedrela toona leaf extracts: An exploration into their antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant potential”

- Retraction of “Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and biological potentials of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the polar extract of Cyperus scariosus R.Br. (Cyperaceae)”

- Retraction to “Green synthesis on performance characteristics of a direct injection diesel engine using sandbox seed oil”