Abstract

Daylighting in traditional mosques is intricately linked to local architectural design, which responds to the unique climate conditions of the region, creating spaces that balance natural light with the cultural and environmental needs of the community. Traditional mosques in Indonesia reflect indigenous architectural knowledge that adapts to local climates. These mosques often feature designs such as four-sided sloping or pyramid-shaped roofs, a style known as typical Javanese. This study investigates the impact of architectural design on daylighting provision in two traditional and historical mosques in the Gayo Highlands of Aceh: Asal Penampaan Mosque (M1) and Tue Kebayakan Mosque (M2). Despite their similar roof styles, these mosques differ in materials and window designs, affecting their interior illumination levels. The study is conducted through field measurements to measure the existing daylight, and simulation utilizing VELUX Daylight Visualizer to simulate daylight levels (illuminance) and daylight factor (DF) in both mosques. The results show that M2, which has been refurbished with modern materials and larger windows, achieves higher illuminance and DF values compared to M1, which retains its traditional sago palm roof and smaller apertures. The findings suggest that window placement and interior surface reflectance significantly influence daylight availability. The dark surface colour of the natural material, such as the sago palm roof, dominates the interior and provides little reflectance of daylight, thus minimizing its distribution throughout the room.

1 Introduction

Traditional mosques are similar to traditional dwellings, which are characterized by indigenous knowledge that adopts the local climate. This is essential to the reduction of climate change [1]. The traditional mosque in warm, humid tropics, such as Indonesia, has a four-sided sloping roof, a pyramid hip roof in a simple style, or a pyramid-shaped stacked roof [2]. In Indonesia, this mosque design is known as the typical Javanese style [2]. The style invites the airflow, cooling the interior, which also contributes to the indoor light [3]. The ground plan is square, and the mosque does not stand on poles. Regarding the design, many discussions are attached to the earthquake fragility, thermal comfort, and visual comfort. Some studies on traditional housing indicate that historical people tend to design a more thermally comfortable space rather than the more lighted ones [4,5].

In Aceh, as in other parts of Indonesia, the cultural and religious functions of traditional mosques deeply influence their architectural choices, particularly regarding materials and design elements. In terms of religious practice, Islamic worship requires large, open prayer halls that face the qibla (the direction of Mecca). This functional need shapes the interior design, leading to minimal internal partitions and often a simple rectangular or square floor plan. Traditional mosques in Aceh feature modest, non-ornate designs to maintain focus on worship. This simplicity is reflected in the use of natural, local materials like wood, which is readily available and easily shaped into clean, functional forms.

Traditional Acehnese mosques are often built from local hardwood, reflecting the region’s rich natural resources. Timber construction allows for flexibility in design, and wooden structures can be modified or repaired relatively easily using traditional techniques. The use of materials like bamboo, thatch, and palm fibres in roof or wall elements aligns with the need for sustainable, environmentally integrated buildings. These materials are well-suited for both thermal insulation and acoustic control, which are important in communal worship settings.

It has been observed that traditional mosques in lowland areas feature more roof openings compared to their counterparts in highland regions. Traditional dwellings in highland areas are generally characterized by smaller windows and fewer apertures. In mosques, the presence of windows and other fenestration elements significantly influences the interior quality and the illumination of the prayer space. The Gayo Highlands, the highest area in Aceh province, hosts several traditional mosques. Among these, the Asal Penampaan Mosque in Blang Kejeren is the oldest, followed by the Tue Kebayakan Mosque in Takengon. Although these two mosques share a similar roof type, they differ in terms of wall and roof materials and window designs. This study investigates the impact of mosque architectural design in highland areas on the provision of natural light within these structures.

The building design above may represent the global environmental conditions of Aceh. The lowland area in Aceh Province, Indonesia has a low air temperature compared with the highland. The lowland average air temperature runs from 26 to 27°C. However, on the highlands located at the altitude of 900–1,350 m above sea level, the average air temperature is about 12–23°C, which is around 5°C lower than that in lowland areas [6,7]. In general, the Gayo Highlands, like other humid tropical climate zones, experience varying sky conditions, from cloudy to overcast, with natural daytime lighting levels reaching up to 5,000–20,000 lux [8]. Within that range, the average solar irradiance level is between 36 and 91% [9]. Highland areas typically receive less solar irradiation and, therefore, experience more consistent and diffused daylight compared to lowland regions [10]. The elevation in highlands results in lower solar angles, which contribute to softer, less intense sunlight. Additionally, frequent cloud cover or mist in these regions further diffuses sunlight, reducing its direct intensity and creating a more uniform natural lighting environment. This contrasts with lowland areas, where clearer skies often allow for stronger, more direct sunlight, leading to higher-intensity illumination [11]. These differences in solar and atmospheric conditions significantly influence natural lighting dynamics in buildings and outdoor settings [12].

1.1 Daylighting and mosque

Daylighting is obtained from natural light, primarily from indirect sunlight. It is an optimal light source because it comfortably aligns with the human visual response [13]. Natural light in buildings represents an attractive component of interior life and gives a great psychological benefit in terms of health and visual comfort [14,15]. Windows contribute to health and well-being both by delivering light to the eyes and providing a means to see the outside environment [16]. Daylighting also improves human psychological comfort [17]. However, it does not reach deep spaces, and this is more acute when there are not enough light-controlling devices to help increase the penetrated light level on the external envelope. Mosques are one clear example where this lighting problem occurs. Therefore, such architectural spaces need to be installed with skylights throughout to ensure sufficient natural light in the central zone [18]. Building designs using a natural light system are considered to have excellent passive lighting design [19], which thus saves energy [20].

In Islamic Architecture, natural light in mosque design is necessary to create an environment where the worshipper can fulfil religious needs and regular visual comfort objectives [21,22]. Mosques are the first Islamic building types wherever a community is built. As Islam spread, mosque design changed and became more diverse due to local influence. For example, Byzantine and Persian architectural styles differ for multiple reasons, such as building materials, techniques, and elements of the environment. Light, regarded as the ultimate representation of Divine Unity, plays a crucial role in the design of openings within Islamic architecture [23,24]. In mosques, these openings transform natural light by shielding its direct source, producing a dramatic interplay of illumination between indoor spaces and the external environment [25]. Therefore, the strategic positioning of openings is essential for achieving this effect and enhancing the overall spatial experience [26].

1.2 Traditional and historical mosques in Gayo Highland

In this study, two traditional and historical mosques in the Gayo Highlands region were evaluated, namely Asal Penampaan Mosque (M1), located in Blang Kejeren, Gayo Lues, and Tue Kebayakan Mosque (M2), located in Takengon, Aceh Tengah (Figure 1). The study focuses on the highland area rather than the lowland region, where most of the population resides, due to the distinct architectural and environmental challenges presented by highland environments. These areas are characterized by lower solar angles and cooler temperatures, which influence daylight availability and intensity.

![Figure 1

The location of M1 and M2 (the map is modified from the study of Iskandar et al. [27]).](/document/doi/10.1515/eng-2025-0135/asset/graphic/j_eng-2025-0135_fig_001.jpg)

The location of M1 and M2 (the map is modified from the study of Iskandar et al. [27]).

In the highlands, cooler temperatures and unique daylight conditions require more specific architectural responses to natural light, ventilation, and insulation [28]. By focusing on these highland mosques, the study aims to provide a deeper understanding of how traditional architecture in this unique environment has evolved and how it can inform sustainable design strategies for similar regions. Additionally, the highland context offers an opportunity to explore how these traditional designs can be adapted or preserved in modern times, contributing to broader discussions on heritage conservation and climate-responsive architecture.

M1, a historic mosque dating back to 1412, stands as a testament to the spread of Islam in Indonesia. Situated approximately 900 m above sea level and just 10 m east of the Penampaan River, the mosque features a timber structure with a roof made of sago palm. Encircled by a stone wall, its original design has been preserved (Figures 2a and 3a). The mosque’s floor measures around 11.5 m by 11.5 m, with four central pillars serving as the main support for the roof [7].

![Figure 2

The historic traditional mosques evaluated in the study: (a) Asal Penampaan Mosque (M1) and (b) Tue Kebayakan Mosque (M2) [7].](/document/doi/10.1515/eng-2025-0135/asset/graphic/j_eng-2025-0135_fig_002.jpg)

The historic traditional mosques evaluated in the study: (a) Asal Penampaan Mosque (M1) and (b) Tue Kebayakan Mosque (M2) [7].

![Figure 3

The interior of (a) Asal Penampaan Mosque (M1) and (b) Tue Kebayakan Mosque (M2) [7].](/document/doi/10.1515/eng-2025-0135/asset/graphic/j_eng-2025-0135_fig_003.jpg)

The interior of (a) Asal Penampaan Mosque (M1) and (b) Tue Kebayakan Mosque (M2) [7].

The Tue Kebayakan Mosque (M2), established in 1903, holds the distinction of being the earliest mosque constructed in Takengon, Central Aceh. Located 1,270 m above sea level and roughly 500 m from Lut Tawar Lake, the mosque was originally crafted using traditional materials, including a timber structure and a roof made of serule leaves [7]. However, it was refurbished with a concrete wall and zinc corrugated roof (Figures 2b and 3b). The floor size of Tue Kebayakan Mosque is similar to Asal Penampaan mosque, i.e. 11.5 m × 11.5 m [6]. In contrast to the Asal Penampaan mosque, The Tue Kebayakan Mosque does not have additional pillars in the middle to support the roof load. Instead, the rooftop structure is supported by two trusses that are directly connected to the pillar at the wall structure [7].

M1 with the enclosed characteristics is also similar to some other highland mosques in Indonesia, such as in Lombok (Bayan Baleq Mosque). Bayan mosque is built using thatched roofs and timber structures. The difference is the wall that is made from bamboo [29].

1.3 Quantifying daylight

To quantify the amount of light level accepted on a surface, illuminance (E) must be measured. Illuminance is the measure of the amount of light received on a surface, which is typically expressed in lux (lm/m2). In the mosque, activities in the reading area require illuminance of up to 250 lux [17]. Daylight factor (DF) is an indicator for quantifying the amount of daylight and its relationship to energy and overheating due to the light [30–32].

DF is a measurement that quantifies the proportion of natural light available within a room, expressed as a percentage of the daylight present outdoors under overcast skies. Several factors influence the level and spread of DF within a space, including the dimensions, placement, arrangement, and transparency of windows in the facade and roof; the spatial layout and dimensions of the interior; the reflective qualities of both interior and exterior surfaces; and the extent to which external obstructions block the view of the sky [13]. The higher the DF, the more daylight available in the room. According to CIBSE (BS EN 17037) and standard practices, recommended DF values are as follows:

>5% (ample daylight, rarely requiring artificial lighting during the day)

2–5% (adequate daylight, artificial lighting occasionally needed)

1–2% (minimal but acceptable daylight, frequent need for artificial lighting)

<1% (insufficient natural light; primarily dependent on artificial lighting).

DF can be measured using Equation (1):

Notes:

Ei is the indoor daylight illuminance level,

Eo is the outdoor daylight illuminance level from an unobstructed overcast sky on a horizontal plane.

The daylight illuminance level at the point is also the sum of the internally reflected components (IRC), externally reflected components (ERC), and sky component (SC), as shown in Equation (2):

where IRC is the internally reflected components, ERC is the externally reflected component, SC is the direct light from the sky.

In the context of daylighting, IRC, ERC, and SC are essential factors that elucidate how natural light penetrates and illuminates interior spaces. IRC pertains to the fraction of daylight that enters a building and subsequently reflects off internal surfaces such as walls, ceilings, and floors. This reflection enhances light distribution within the space, mitigating high-contrast areas and thereby improving overall illumination. ERC denotes the segment of daylight that is reflected into the building from external surfaces, including nearby structures, ground surfaces, and other reflective elements in the vicinity. SC, or direct light from the sky, refers to the portion of daylight that enters a building directly from the sky, without any intermediary reflections.

For optimal daylighting, architects and designers must take into account IRC, ERC, and SC to create environments that are well-lit, energy-efficient, and comfortable. Strategic window design and the use of reflective surfaces both within and outside the building are crucial for maximizing natural light while minimizing issues such as glare and heat gain. This comprehensive approach ensures the effective integration of natural light, enhancing both the functional and aesthetic qualities of indoor spaces.

1.4 VELUX Daylight Visualizer

VELUX Daylight Visualizer is a comprehensive tool dedicated to lighting simulation, commonly used for design phases [33]. It is also widely trusted for daylight simulations in both research and professional applications [12,34]. The software allows architects and engineers to conduct daylighting analyses and perform simulations, modelling daylight behaviour to predict factors such as illuminance, daylight autonomy, and useful daylight illuminance (UDI) in various building spaces [35]. Additionally, the tool supports the calculation and visualization of the DF, a crucial measure of natural light that indicates the ratio of indoor to outdoor illumination under overcast conditions. Numerous case studies and research papers highlight the tool’s effectiveness in simulating DF and other daylight metrics. Moreover, VELUX Daylight Visualizer adheres to international lighting standards, including CIE and LEED, ensuring reliable and standardized results for daylight analysis [33].

2 Methods

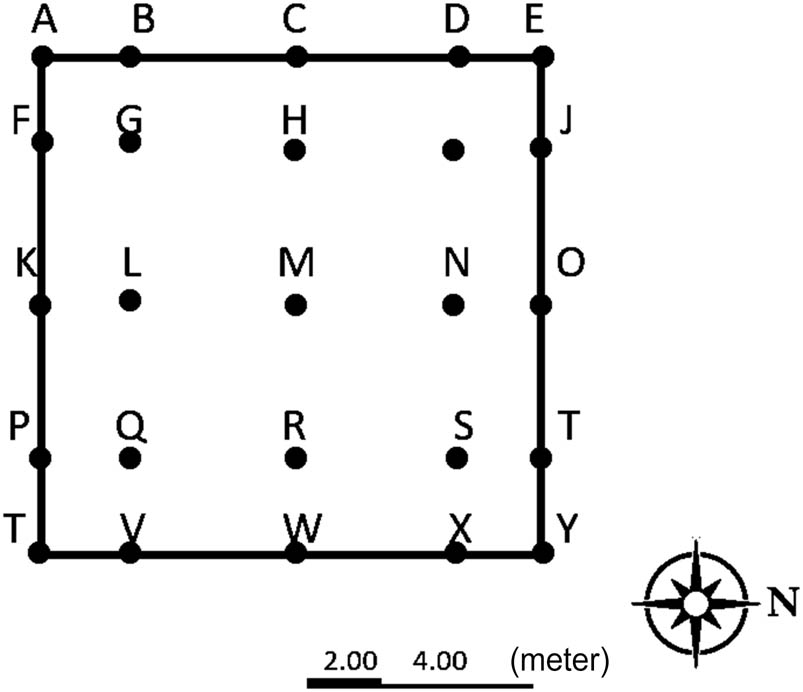

This study builds upon the research conducted by Sari et al. [7]. In a previous study, the results focused on the general descriptions of sustainability values in the old mosque architecture. In the current study, we investigate the daylighting performance of mosque interiors. The performance of natural light levels (illuminance) and the DF in two historic mosques was assessed using the data obtained from both field measurements and simulations. The field measurements were conducted on 21 September 2023, at 09:00, 12:00, and 15:00 over 3 days. A digital lux meter (Benetech, GM1010) with a measuring range of 0–200,000 lux was utilized. The meter was set at a height of 0.75 m above the floor surface. The illuminance data were contoured on the floor plan using Surfer 19 software. Measurements were recorded at nine spots (Figure 4), with points A, B, C, D, and E positioned facing west.

Nine measurement points run at M1 and M2.

A simulation was also conducted using VELUX Daylight Visualizer software. The illuminance rendering was set at the same height as the field measurement, i.e. 0.75 m above the floor surface (Figure 5). The types of rendering used were a plan view and a false colour technique. Illuminance simulations were carried out at 09:00, 12:00, and 15:00 on 21 March. This date was selected because it coincides with the sun’s trajectory during equinox conditions (21 March/21 September). Overcast sky conditions were used in the simulation. Meanwhile, the DF was simulated at 12:00 when the sun is directly overhead. At this time, the distribution of light tends to be more uniform, minimizing the effects of shadows cast by surrounding objects and structures. This uniformity simplifies the calculation of the DF and makes it easier to analyze the overall daylighting effectiveness of a design.

Plan view and cross-section: (a) Asal Penampaan Mosque (M1), and (b) Tue Kebayakan Mosque (M2) set in VELUX visualizer.

The field measurement and the simulations for both mosques were conducted with open windows. The Indonesian standards (SNI) were utilized to evaluate the quality of the daylight. Specifically, SNI 03-6575-2001 was applied to assess daylight levels (illuminance-E), while SNI 03-2396-2001 was used to evaluate the DF. Additionally, the Illuminating Engineering Society (IES) Handbook [36] was referenced as an alternative for the recommended illuminance levels.

3 Results

3.1 Illuminance (E)

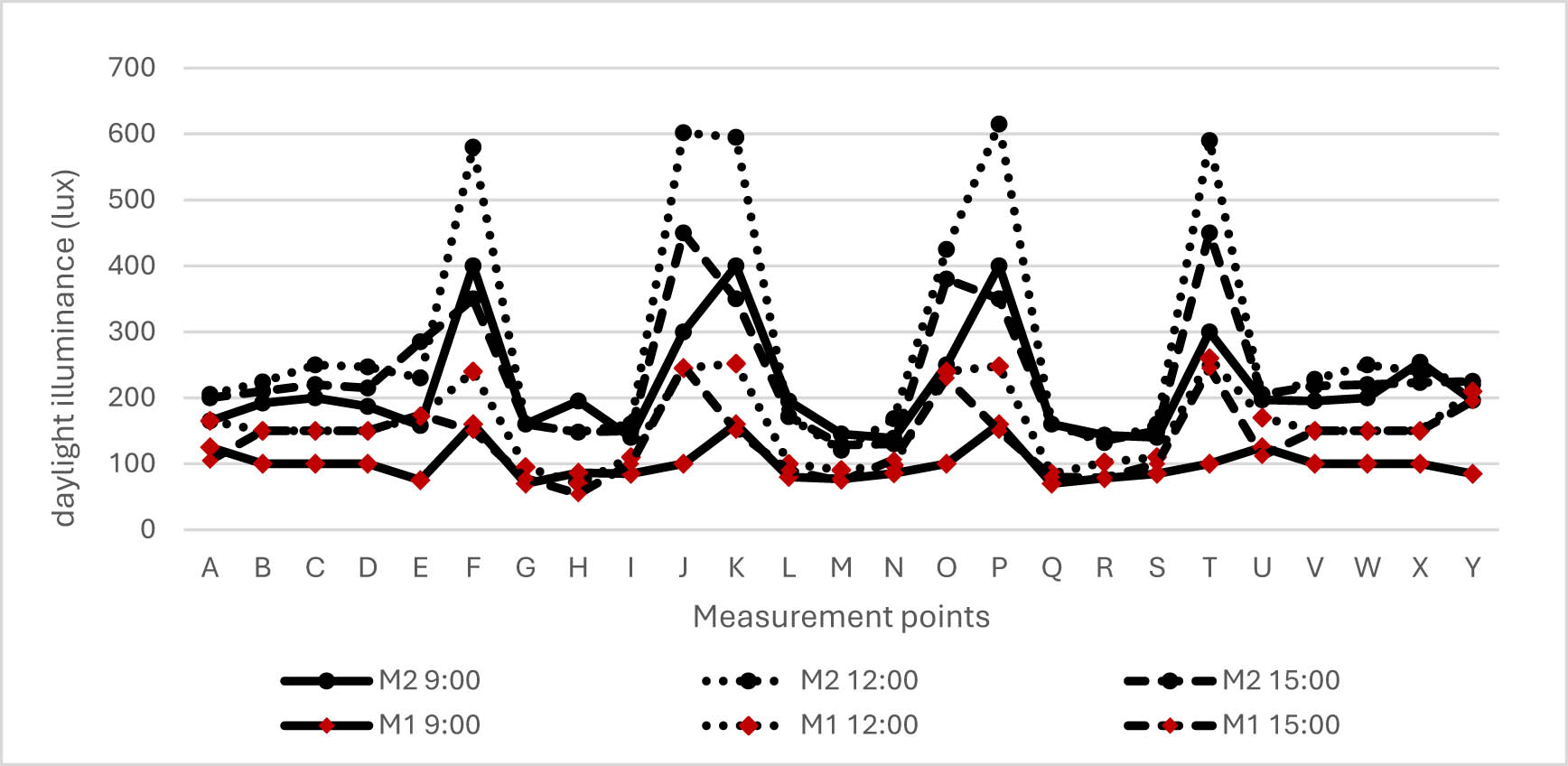

Table 1 and Figure 6 show the field measurement data of daylight illuminance in M1 and M2. During the measurements, the sky was overcast, and the outdoor illuminance was approximately 20,000 lux. From both the field measurements and simulations, we observed that the amount of daylight (illuminance) entering the interior of M2 is higher than that of M1. Figure 6 shows the high illuminance of daylight entering at 12:00, which is distributed near the openings. M2 has higher illuminance, as shown in Table 1, where the average daylight level is around 216.46 lux, while M1’s daylight level ranges from 100.29 to 159.09 lux.

Daylight illuminance values (lux) received in the interior of the mosques

| M1 | M2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 09:00 | 12:00 | 15:00 | 09:00 | 12:00 | 15:00 | |

| Avg | 100.288 | 159.092 | 137.876 | 216.46 | 283.956 | 235.384 |

| Max | 160 | 250 | 250 | 400 | 600 | 450 |

| Min | 70 | 69.7 | 54.2 | 138.8 | 120.4 | 128.3 |

| SD | 26.57 | 61.43 | 55.18 | 82.24 | 171.73 | 97.76 |

The average indoor daylight illuminance (lux) from three days of measurement in M1 and M2, distributed across nine measurement points (A–Y) throughout the rooms.

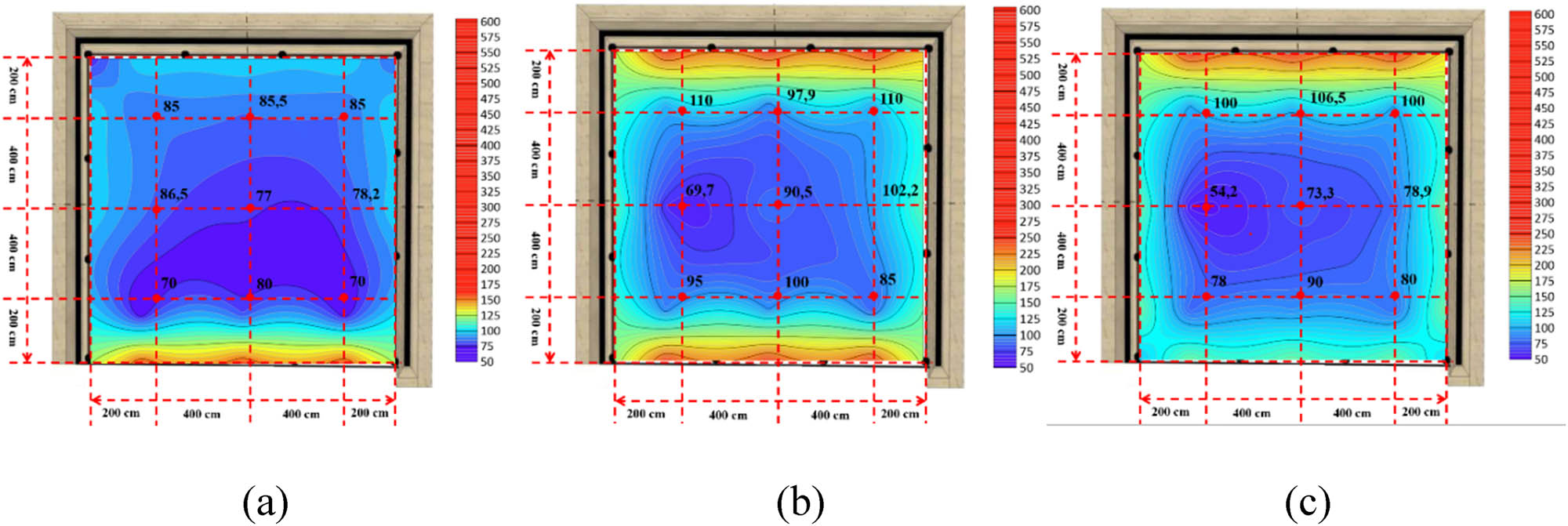

Figure 7 shows the contour of the measured illuminance distribution in M1, generated by Surfer 19. From morning to afternoon, the daylight illuminance received in the room ranges from 60 to 250 lux. The highest illuminance is mostly near the openings on the west and east sides. In the centre of the room, the illuminance ranges from 70 to 86.5 lux at 09:00, 85 to 110 lux at 12:00, and 54.2 to 160 lux at 15:00.

Distribution of daylight illuminance (lux) in the floor plan of M1 run by Surfer at (a) 09:00, (b) 12:00, and (c) 15:00.

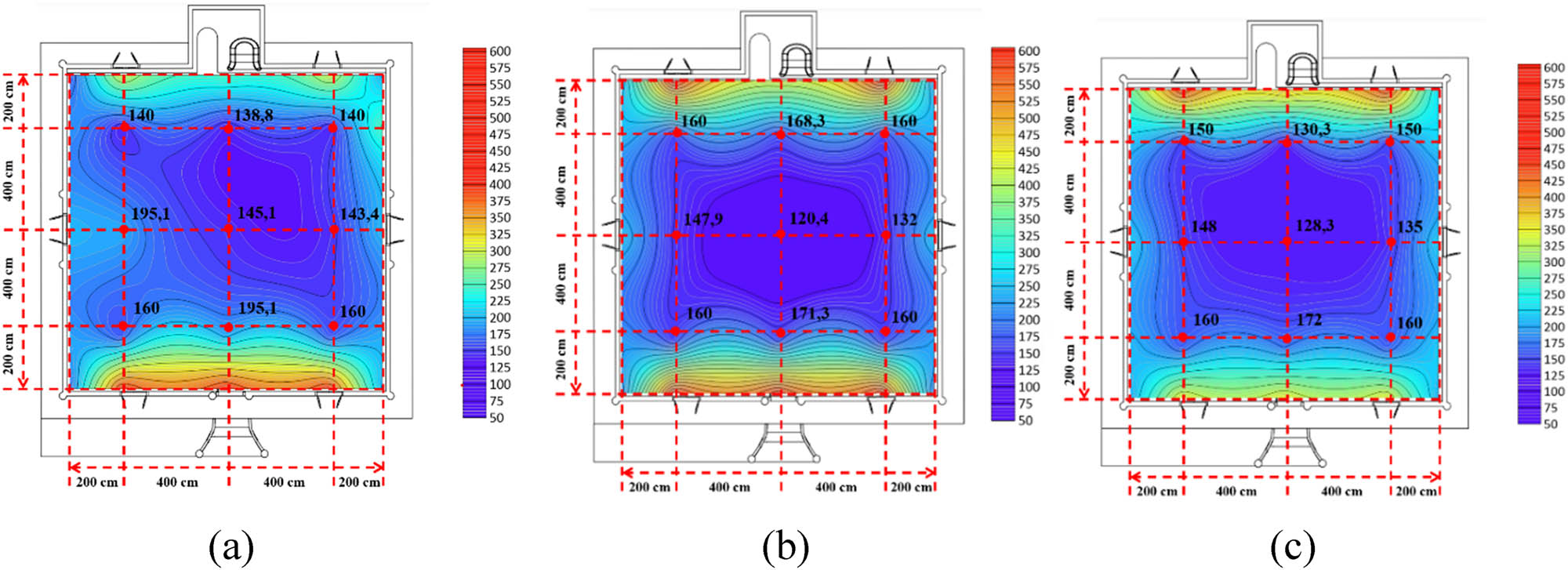

M2 has higher indoor illuminance, ranging from 120 to 600 lux from morning to afternoon (Figure 8). Similar to M1, the highest illuminance occurs near the apertures. In the centre of M2, the illuminance ranges from 138.8 to 195.1 lux at 09:00, 120.4 to 171.3 lux at 12:00, and 128.3 to 172 lux at 15:00.

The distribution of daylight illuminance (lux) in the floor plan of M2 run by Surfer at (a) 9:00, (b) 12:00, and (c) 15:00.

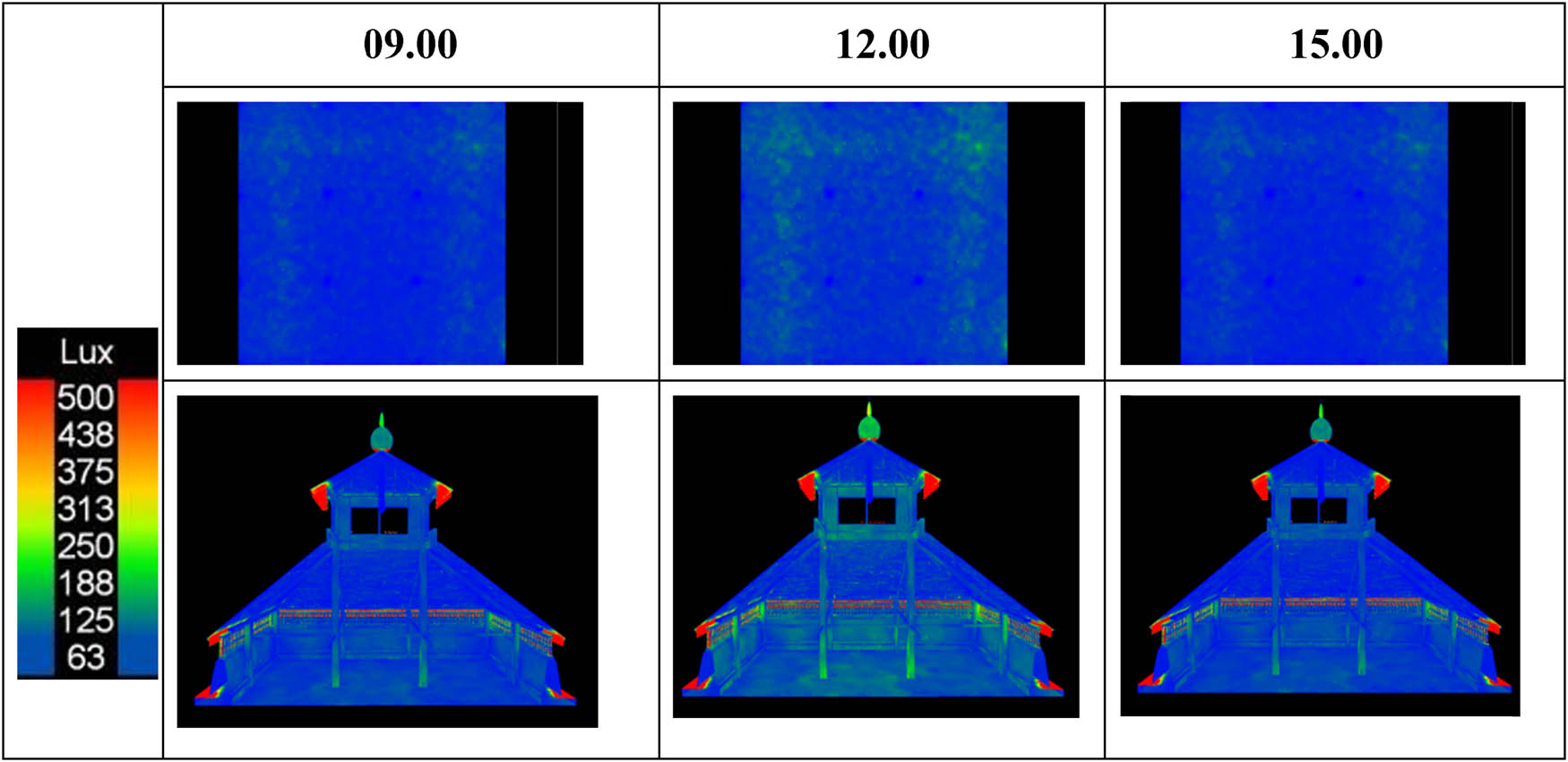

In order to identify how the two mosques handle daylight, the same outdoor illuminance value (600 lux), ignoring any possible external distractions, was applied in the VELUX Daylight Visualizer to predict the illuminance levels, and to calculate the predicted DF. The VELUX simulations showed results consistent with the field measurements, where M2 demonstrates a greater ability to bring more daylight into the interior. Figure 9 shows the rendering of the VELUX simulation for M1, where the openings along the wall perimeter and the attic openings are open. The illuminance (E) values ranged from 63 to 250 lux. While not significantly different, we observed that at noon, natural light predominantly enters through the fenestrations, either from the wall perimeter or the roof ventilation.

Distribution of daylight illuminance throughout the interior of M1.

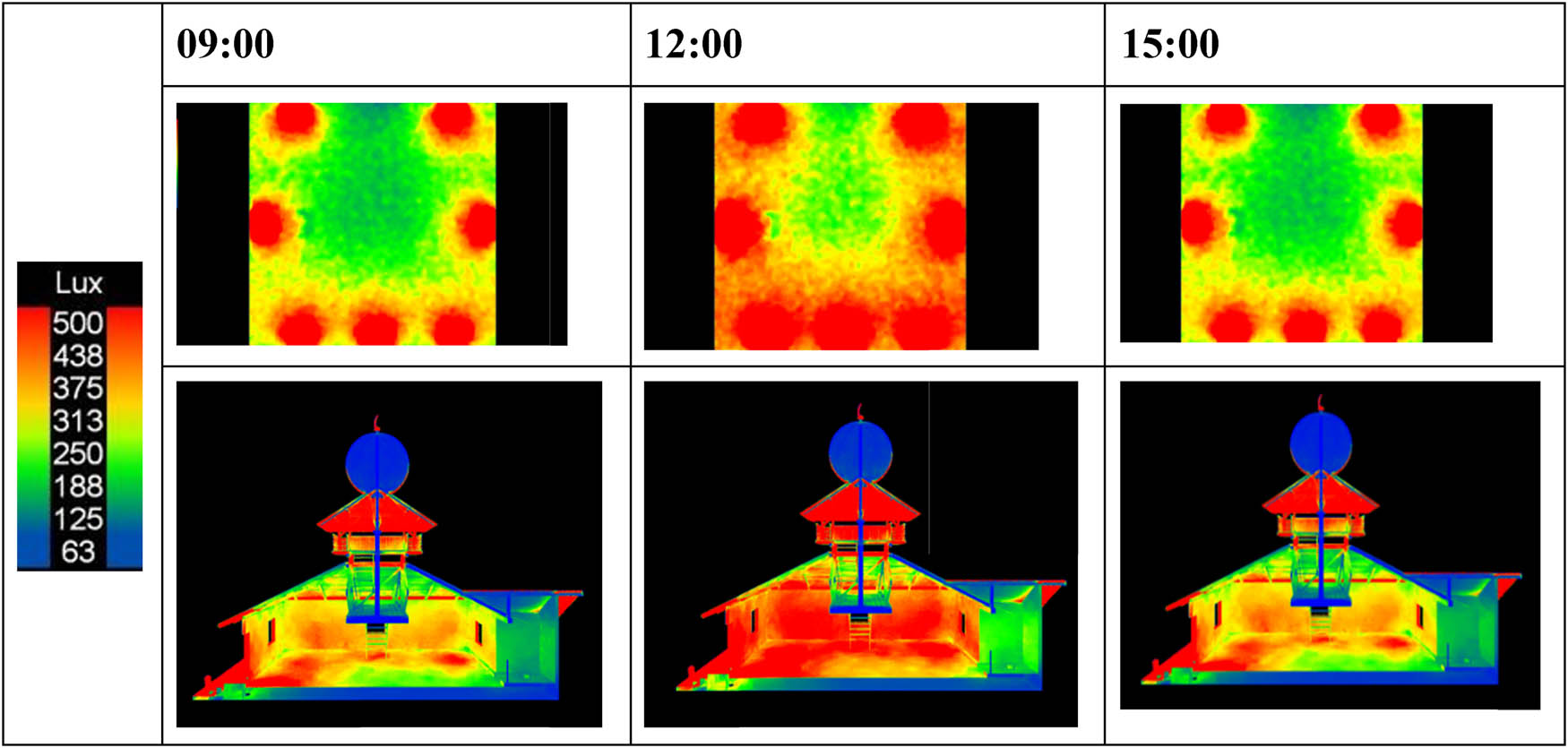

Figure 10 shows the illuminance rendering value of the M2 mosque when the door and the windows are left open. Illuminance (E) values were in the range of 63–500 lux. The E value was quite high near the opening zone because of the large size of the windows that gave the light access from outside. At noon, all the zones had high illuminance, which was around 250–500 lux. The VELUX simulation shows a higher value of illuminance compared with field measurement data. It is because VELUX software uses idealized conditions for simulation, such as consistent weather patterns, perfect material properties, and no interference from surroundings. Field measurements, on the other hand, are subject to real-world variables like weather fluctuations, unexpected shading, or imperfect material conditions.

Distribution of daylight illuminance throughout the interior of M2.

The primary function of the mosque was originally prayer, which did not require a particularly bright environment. According to IES [36], the simple function can be justified as requiring around 50–100 lux. Therefore, in general, the daylight illuminance levels in the interiors of M1 and M2 comply with this standard. However, the function of the mosque has since evolved to include more complex activities, such as Islamic study circles, marriage contract ceremonies, and celebrations of Islamic events, all of which require more light to support these activities. In response to this, the Indonesian standard (SNI 03-6575-2001) sets the average illuminance value (E) for mosques at 200 lux.

3.2 DF

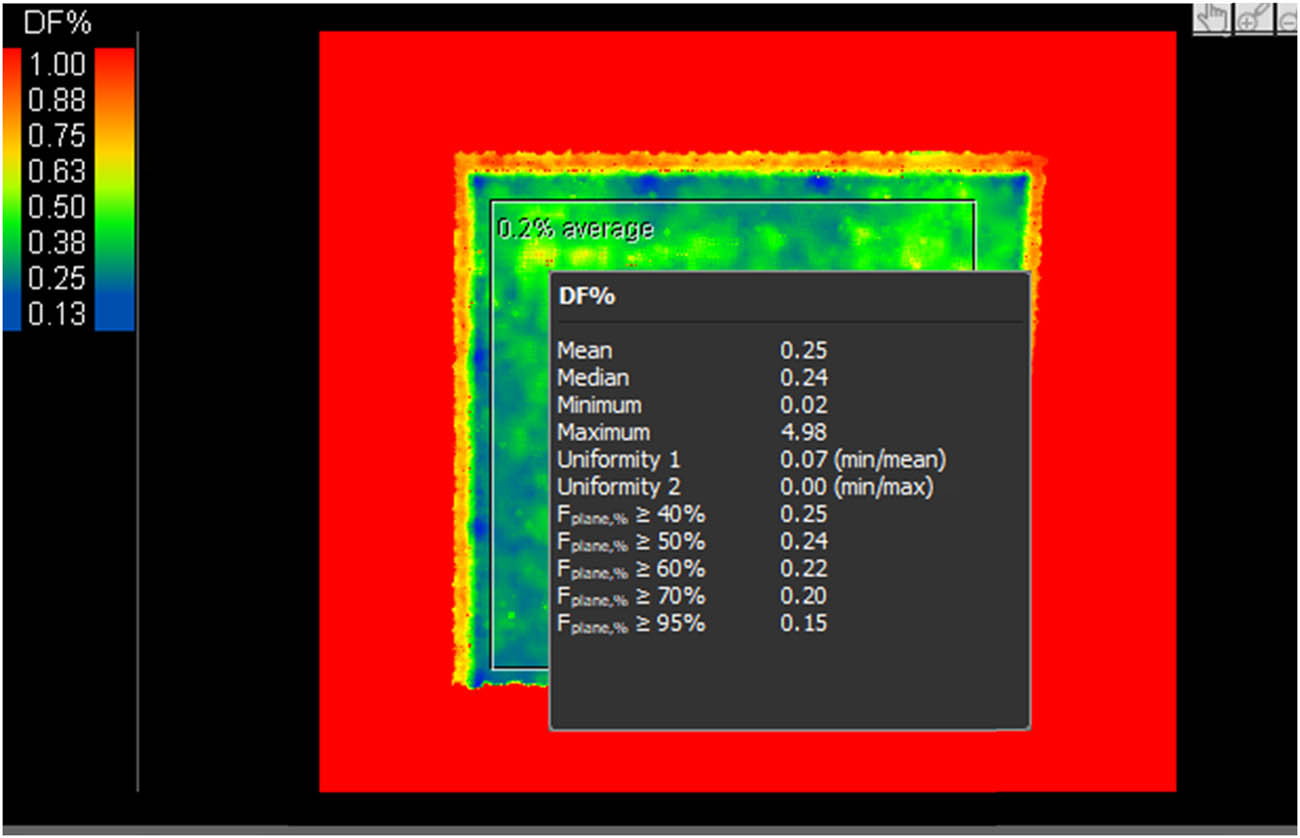

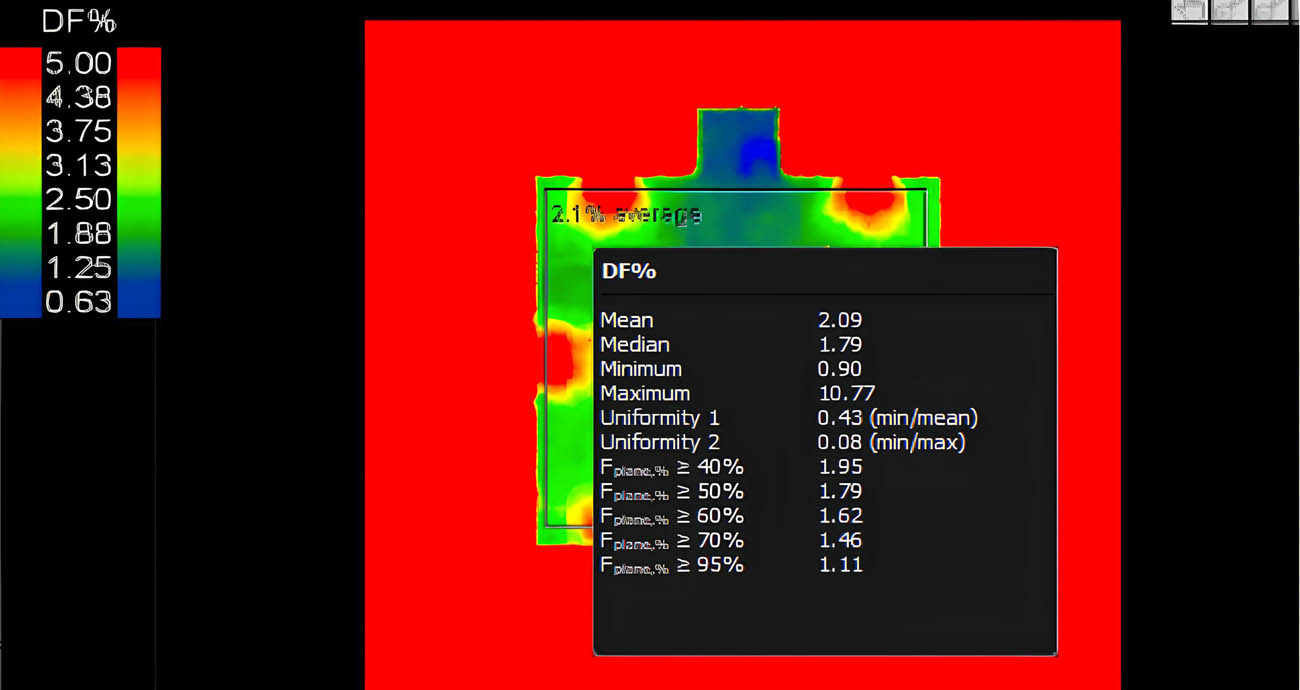

The average value of the DF obtained in the two mosques from the simulation is various, and follows the daylight level in the interior. The mean value of DF in M1 is 0.25%, while the minimum and the maximum are 0.02 and 4.98%, respectively (Figure 11). In contrast, M2 has a higher DF, which is up to 10.77% at the maximum level. The mean value is 2.09% and the minimum one is 0.9% (Figure 12).

DF distribution in M1 at 12:00.

DF distribution in M2 at 12:00.

Based on SNI 03-2396-200 and CIBSE (BS EN 17037), the average DF in M1 falls below 2%, indicating a need for additional artificial lighting. However, certain spots may exhibit DF values that meet the daylighting standard. Conversely, in M2, the average DF is notably higher at 2%, indicating well-lit conditions overall.

4 Discussion

4.1 Architectural features and their influence on daylight distribution

4.1.1 M1 (Asal Penampaan Mosque)

The dark interior of M1 can be attributed to its traditional design elements, which prioritize functionality and cultural values over maximizing interior brightness. The central four-pillared timber structure and sago palm roof highlight the mosque’s traditional craftsmanship and the use of lightweight, natural materials. While the open roof structure and timber elements may allow for diffused daylight patterns, they are not optimized for maximizing light penetration, instead focusing on reducing glare and maintaining a serene atmosphere suitable for worship. The compact dimensions (11.5 m × 11.5 m) and single-volume space, combined with limited openings for natural light, further contribute to the subdued interior brightness. The mosque relies on carefully positioned windows or small gaps in the roof structure to provide daylight, but the surrounding stone wall restricts external light reflection, reducing the overall luminosity inside. This interplay between architectural design and the environmental setting emphasizes the role of indirect light diffusion in creating a balanced yet intentionally dim lighting condition. As a largely unaltered fifteenth-century structure, M1 exemplifies traditional Acehnese architecture, with its reliance on natural materials aligning with sustainable design principles.

4.1.2 M2 (Tue Kebayakan Mosque)

The interior of M2 gains more daylight compared to M1 primarily due to the modern architectural adaptations introduced during its renovation. The zinc corrugated roof, a significant departure from M1’s traditional sago palm roof, plays a critical role in this increase. Zinc, being a metallic material, has a reflective surface that enhances internal light diffusion, creating a brighter interior environment. This contrasts with the sago palm roof of M1, which absorbs more light and produces a softer, more subdued lighting effect. Additionally, the absence of central pillars in M2, replaced by two trusses supporting the roof, opens up the interior space. This unobstructed layout allows for a better distribution of light throughout the mosque, especially from windows or other openings. In contrast, M1’s four central pillars may create shadowed zones, contributing to its darker interior.

These design changes in M2 reflect a shift towards addressing practical considerations such as durability, maintenance, and accommodating community preferences for brighter spaces. However, while the increased daylight in M2 offers functional benefits, it may come at the cost of disrupting the traditional lighting patterns that were integral to the spiritual ambience and cultural identity of mosques like M1. The more reflective zinc roof and the removal of structural elements that traditionally influenced light and ventilation highlight the tension between the preservation of heritage and modernization to meet contemporary needs.

4.2 Effect of the window area and type on daylight provision

M2 has a brighter interior and a higher daylight level compared to M1, which has a darker interior. The percentage of window or ventilation area to floor area in both mosques is relatively similar, approximately 22.8%. However, the type and placement of openings significantly influence the distribution and quality of daylight within the interiors.

In M1 (Asal Penampaan Mosque), the design features ground-level wall ventilations that are 50 cm high and 26.4 m2 wide along the 140 cm high perimeter wall. Additionally, it incorporates clerestory ventilation with a total area of 10.56 m2, which remains uncovered by glass. These open clerestory windows can deliver up to 40–50% of the required daylight for a room under clear sky conditions. The placement and type of openings in M1 – combining ground-level ventilation and high-level clerestories – contribute to a balanced distribution of daylight. However, the relatively smaller openings and reliance on a diffused light result in a dimmer, more subdued interior ambience, which aligns with its traditional and spiritual setting.

On the other hand, M2 incorporates roof openings but also features larger wall windows compared to the narrower windows in M1. These windows use jalousie designs with horizontal, wood-carved awnings that remain open. The larger openings in M2 allow for significantly more daylight to enter, creating a brighter interior. However, the uneven distribution of daylight becomes a concern. The wall windows, positioned lower and without clerestory counterparts, allow direct light penetration, which may create bright spots and areas of contrast, disrupting the uniformity of lighting within the space.

Thus, while M2 benefits from greater daylight levels due to its larger openings, the traditional design of M1 ensures a more even and functional daylight distribution. This comparison highlights the trade-offs between maximizing daylight and maintaining balanced interior lighting when adapting traditional architectural features. It also emphasizes the importance of carefully considering opening types and placement to achieve both functional and aesthetic goals in mosque design.

This study also indicates that the height of windows from the floor significantly influences interior daylight levels. Higher window placements may reduce brightness during specific morning and afternoon periods. The 140 cm-high and 80 cm-deep walls in M1 result in sunlight rejection before 9 am and after 3 pm. Conversely, M2 receives more daylight than M1, with windows positioned around 40 cm high and extending up to 100 cm, facilitating longer daylight exposure across a larger area. This study agrees that building forms would impact the performance of indoor daylight [37].

4.3 Ceiling surface impact on daylighting

The type and size of apertures/windows also influence natural light and DF values [16]. Larger aperture surfaces enhance interior light levels [38]. Additionally, this study highlights the IRC as a critical factor contributing to brightness. M2 achieves a higher DF percentage, attributed to its polished corrugated zinc ceiling with a light reflective value (LRV) of 75%. This contrasts with M1’s sago palm ceiling, which has a lower LRV of 18% due to its brown colour.

4.4 Building orientation and daylight quality

Building orientation significantly impacts daylight availability, with east-facing sides receiving more morning light and west-facing sides benefiting from afternoon light [30]. Both mosques are oriented towards Mecca, located close to the west at 295° clockwise from the north in Aceh, with minimal fenestration on the qibla side to reduce afternoon glare and maintain focus during prayer. Openings are predominantly situated on the east, north, and south sides to maximize daylight penetration. The interior surface reflectance values also play a crucial role in determining daylight quality.

4.5 Constraints on modifying traditional designs

Traditional mosques hold significant historical value, but several constraints make it easier to replace them with modern buildings. One challenge is the lack of natural materials, such as hardwood and palm fibres, to preserve the structure. Additionally, the shortage of skilled artisans who can work with these materials complicates efforts to modify the mosques while maintaining their original style and integrity. This issue is compounded by the typically dark interiors of traditional buildings, as highlighted in this study. However, there may be other factors that older generations consider beyond simply brightening the interior.

Modern materials like zinc roofing offer durability and weather resistance, but they can diminish the mosque’s connection to local heritage. Similarly, new windows might disrupt the original design, which was adapted to the highland climate and cultural needs, affecting both aesthetics and function. This can alter the mosque’s historical and cultural continuity, disconnecting it from the past.

In Aceh, preserving traditional and historical buildings is challenging because many aspects of old structures no longer meet modern needs. People tend to prioritize comfort, including visual comfort. Without strict government regulations to protect them, there is a significant risk that these buildings, such as mosques, may be lost.

4.6 Improving daylight and design in historic architecture

To improve daylight and design in historic architecture, based on the study of traditional mosques like M1 and M2 in Gayo Highland, several aspects can be considered. First, optimizing window placement is key; the design of openings should be enhanced to capture more natural light while maintaining thermal and acoustic performance. Strategically positioning windows, such as clerestories or larger wall openings, can increase daylight penetration without compromising the building’s aesthetics or structural integrity.

Additionally, material selection plays a crucial role in light distribution – traditional materials like wood can be complemented with light-reflective surfaces, such as light-coloured walls or ceilings, to evenly distribute daylight within the space. Preserving the mosque’s cultural identity while incorporating modern materials, like glass and sustainable technologies, is essential. This can be achieved by integrating these modern systems discreetly, ensuring they blend with the traditional design.

Finally, to prevent harsh sunlight from entering directly, light diffusion techniques, such as frosted glass or louvred systems, can be used to ensure an even distribution of daylight throughout the interior. By combining these strategies, it is possible to enhance the daylighting and design of historic mosques while preserving their cultural and architectural integrity.

5 Conclusion

This study evaluates the design of historic mosques located in Gayo Highlands, Indonesia. There are two mosques with distinct designs: Asal Penampaan Mosque (M1) in Blang Kejeren, constructed in its original form with a sago palm roof, stone walls, and long apertures along the walls and roof. The other mosque is the Tue Kebayakan Mosque (M2) in Takengon, which has been renovated with concrete walls, zinc corrugated roof, and different ventilation types, including awning jalousie windows. The percentage of opening area to floor area is similar in both M1 and M2. M1 features long apertures along the walls and roof, while M2 utilizes modern awning jalousie windows.

This study reveals that the mosque with the original sago palm roof, stone walls, and traditional ventilation (M1) has lower levels of natural illuminance and DF compared to M2. M2 benefits from a brighter interior due to its window type and zinc ceiling surface. However, the lower values of illuminance and DF in M1 still support basic activities. This study demonstrates that the reflectance of interior surfaces significantly affects indoor brightness. The brown colour of the sago palm roof diminishes internal reflection values, resulting in lower brightness compared to the shiny metal zinc surface used in M2.

This research has broader implications for architectural design and daylight in historic buildings. However, due to the limitations of this study, which focuses solely on daylight assessment, further research is needed on the relationship between historic mosque design, daylight, and thermal comfort. Generally, light can bring heat, so future studies should explore how the integration of modern building practices can improve light access without undermining the thermal benefits of traditional designs. Additionally, addressing the limitations of this study, such as its focus on only two mosques, highlights the necessity for further investigations across a wider array of traditional buildings to validate these findings.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our deepest gratitude to Universitas Syiah Kuala and the Indonesian Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology for supporting this research. Our thanks also go to Salsabila for helping to run the VELUX daylight visualizer, and Dinda Ramadani for running the Surfer application.

-

Funding information: This study is part of the 2023 PDKN research Grant, funded by the Indonesian Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology. (Research Grant Contract Number: 563/UN11.2.1/PT.01.03/DPRM/2023).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript. All the authors’ contributions are as follows: LHS: conceptualization, methodology, writing – original draft, supervision, and acting as the corresponding author; YI: data analyzing, reviewing, and editing; EW: assisting with the data collection; SNMK: interpreting the data collected from the simulation.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Husin AE, Priyawan P, Kussumardianadewi BD, Pangestu R, Prawina RS, Kristiyanto K. Renewable energy approach with Indonesian regulation guide uses blockchain-BIM to green cost performance. Civ Eng J. 2023;9(10):2486–502. https://mail.civilejournal.org/index.php/cej/article/view/4305/pdf.10.28991/CEJ-2023-09-10-09Search in Google Scholar

[2] Jamaludin J, Salura P. Understanding the meaning of triangular shape in mosque architecture in Indonesia. Int J Eng Technol. 2018 Sep;7(4.7):458.10.14419/ijet.v7i4.7.27359Search in Google Scholar

[3] Budi BS. A study on the history and development of the Javanese mosque. J Asian Archit Build Eng. 2004 May;3(1):189–95. 10.3130/jaabe.3.189.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Ridhaini P. Sejarah Masjid Tertua Di Aceh Tengah. Lhoksemawe; 2021. https://www.academia.edu/49966905/SEJARAH_MASJID_TUA_KEBAYAKAN_ACEH_TENGAH.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Putra RA, Zahrah A, Dewi C, Izziah. The influence of architecture of Umah Pitu Ruang on Gayonese modern housing in Takengon. IOP Conf Ser: Mater Sci Eng. 2021;1087:012008. 10.1088/1757-899X/1087/1/012008.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Salsabila S, Sari LH, Edytia MHA. Optimization of natural lighting level in Umah Pitu Ruang in Gayo Higland, Indonesia. J Build Des Environ. 2024;3(1):1–15. 10.37155/2811-0730-0301-2.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Sari LH, Wulandari E, Idris Y. An investigation of the sustainability of old traditional mosque architecture: case study of three mosques in Gayo Highland, Aceh, Indonesia. J Asian Archit Build Eng. 2024 Mar;23(2):528–41. 10.1080/13467581.2023.2245006.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Lechner N. Chapter 13: Daylighting. In Heating, cooling, lighting: Sustainable design methods for architect. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2014. p. 399–451.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Olgay V, Egan M. Architectural lighting. 2nd edn. New York: McGraw-Hill Company; 2002.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Ferry A, Thebault M, Nérot B, Berrah L, Ménézo C. Modeling and analysis of rooftop solar potential in highland and lowland territories: Impact of mountainous topography. Sol Energy. 2024;275:112632. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0038092X2400327X.10.1016/j.solener.2024.112632Search in Google Scholar

[11] Siswanto S, Nuryanto DE, Ferdiansyah MR, Prastiwi AD, Dewi OC, Gamal A, et al. Spatio-temporal characteristics of urban heat Island of Jakarta metropolitan. Remote Sens Appl. 2023;32:101062. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352938523001441.10.1016/j.rsase.2023.101062Search in Google Scholar

[12] Ahmad A, Kumar A, Prakash O, Aman A. Daylight availability assessment and the application of energy simulation software – A literature review. Mater Sci Energy Technol. 2020;3:679–89. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2589299120300410.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Tregenza P, Mardaljevic J. Daylighting buildings: Standards and the needs of the designer. Lighting Res Technol. 2018 Jan;50(1):63–79.10.1177/1477153517740611Search in Google Scholar

[14] Arab Y, Sanusi Hassan A. Daylight performance of single pedentive dome mosque design during winter solstice. Am J Environ Sci. 2013 Jan;9(1):25–32.10.3844/ajessp.2013.25.32Search in Google Scholar

[15] Mba EJ, Okeke FO, Ezema EC, Oforji PI, Ozigbo CA. Post occupancy evaluation of ventilation coefficient desired for thermal comfort in educational facilities. J Human Earth Future. 2023;4(1):88–102.10.28991/HEF-2023-04-01-07Search in Google Scholar

[16] Boyce P, Hunter C, Howlett O. The benefits of daylight through windows sponsored by: Capturing the daylight dividend program. New York: Lighting Research Center, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute; 2003.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Hassan AS, Arab Y. Lighting analysis of single pendentive dome mosque design in Sarajevo and Istanbul during summer solstice. Arab World Geogr. 2012;15(2):163–79. Search in Google Scholar

[18] Alkhater M, Alsukkar M and Su Y. Evaluation and improvement of daylighting performance with the use of light shelves in mosque prayer halls with a dome structure: A comparative study of four cases in Saudi Arabia. Buildings. 2025;15(16):2826. 10.3390/buildings15162826.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Debnath R, Bardhan R. Daylight performance of a naturally ventilated building as parameter for energy management. In Energy Procedia. Elsevier Ltd; 2016. p. 382–94.10.1016/j.egypro.2016.11.205Search in Google Scholar

[20] Harsritanto BIR, Nugroho S, Dewanta F, Prabowo AR. Mosque design strategy for energy and water saving. Open Eng. 2021;11(1):723–33. 10.1515/eng-2021-0070.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Belakehal A, Tabet Aoul K, Farhi A. Daylight as a design strategy in the Ottoman mosques of Tunisia and Algeria. Int J Archit Herit. 2016 Aug;10(6):688–703.10.1080/15583058.2015.1020458Search in Google Scholar

[22] Hoomani RTM. Assessment of daylight role in creating spiritual mood in contemporary mosques. Armanshahr Archit Urban Dev. 2014 Jun;7(1):11–23.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Askarizad R, He J, Ardejani RS. Semiology of art and mysticism in Persian architecture according to Rumi’s mystical opinions (Case Study: Sheikh Lotf-Allah Mosque, Iran). Religions (Basel). 2022 Nov;13(11):1059. 10.3390/rel13111059.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Burckhardt T. Language and meaning. Art of Islam. Bloomington, Indiana: World Wisdom, Inc.; 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Gherri B. Assessment of daylight performance in buildings: Methods and design strategies. Billerica, MA: WIT Press; 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Shahani M. Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque: A story of daylight in sequential spaces. Space Cult. 2021 Feb;24(1):19–36.10.1177/1206331218782406Search in Google Scholar

[27] Iskandar D, Sinar TS, Samad IA, Gadeng AN. Natural disaster mitigation values in discourse: The true story of the Acehnese tsunami victims. Forum Geografi. 2022;36(1):80–90. 10.23917/forgeo.v36i1.14032 2022.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Philokyprou M, Michael A, Malaktou E, Savvides A. Environmentally responsive design in Eastern Mediterranean. The case of vernacular architecture in the coastal, lowland and mountainous regions of Cyprus. Build Environ. 2017;111:91–109. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360132316304024.10.1016/j.buildenv.2016.10.010Search in Google Scholar

[29] Hamdani M. Acculturation of local culture and islamic teachings in Bayan, North Lombok Regency a review of symbolic interaction in cultural communication. Gema Wiralodra. 2024;15(1):372–9.10.31943/gw.v15i1.613Search in Google Scholar

[30] Kaminska A. Impact of building orientation on daylight availability and energy savings potential in an academic classroom. Energies (Basel). 2020;3(18):4916. 10.3390/en13184916.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Simm S, Coley D. The relationship between wall reflectance and daylight factor in real rooms. Archit Sci Rev. 2011;54:329–4.10.1080/00038628.2011.613642Search in Google Scholar

[32] Sari DP. Visualising daylight for designing optimum openings in tropical context. ARSNET. 2024 Apr;4(1):74–85.10.7454/arsnet.v4i1.87Search in Google Scholar

[33] de Kok VCAJ. DaylightGuide: A tool for personalized daylight recommendations for the home office. Doctorate thesis. Eindhoven, The Netherlands: Eindhoven University of Technology; 2024.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Yang W, Wong NH, Zhang G. A comparative analysis of human thermal conditions in outdoor urban spaces in the summer season in Singapore and Changsha, China. Int J Biometeorol. 2013;57:895–907.10.1007/s00484-012-0616-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Ahmad A, Kumar A, Prakash O, Aman A. Daylight availability assessment and the application of energy simulation software – A literature review. Mater Sci Energy Technol. 2020 Jan;3:679–89.10.1016/j.mset.2020.07.002Search in Google Scholar

[36] DiLaura DL. The lighting handbook: Reference and Application, Illuminating Engineering Society of North America. Lighting handbook reference & application. IES; 2011.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Alhilo IA, Ismael Kamoona GM. Parametric analysis of the influence of climatic factors on the formation of traditional buildings in the city of Al Najaf. 2024;14(1):4916. 10.1515/eng-2022-0525.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Kousalyadevi G, Lavanya G. Optimal investigation of daylighting and energy efficiency in industrial building using energy-efficient velux daylighting simulation. J Asian Archit Build Eng. 2019 Jul;18(4):271–84.10.1080/13467581.2019.1618860Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Modification of polymers to synthesize thermo-salt-resistant stabilizers of drilling fluids

- Study of the electronic stopping power of proton in different materials according to the Bohr and Bethe theories

- AI-driven UAV system for autonomous vehicle tracking and license plate recognition

- Enhancement of the output power of a small horizontal axis wind turbine based on the optimization approach

- Design of a vertically stacked double Luneburg lens-based beam-scanning antenna at 60 GHz

- Synergistic effect of nano-silica, steel slag, and waste glass on the microstructure, electrical resistivity, and strength of ultra-high-performance concrete

- Expert evaluation of attachments (caps) for orthopaedic equipment dedicated to pedestrian road users

- Performance and rheological characteristics of hot mix asphalt modified with melamine nanopowder polymer

- Second-order design of GNSS networks with different constraints using particle swarm optimization and genetic algorithms

- Impact of including a slab effect into a 2D RC frame on the seismic fragility assessment: A comparative study

- Analytical and numerical analysis of heat transfer from radial extended surface

- Comprehensive investigation of corrosion resistance of magnesium–titanium, aluminum, and aluminum–vanadium alloys in dilute electrolytes under zero-applied potential conditions

- Performance analysis of a novel design of an engine piston for a single cylinder

- Modeling performance of different sustainable self-compacting concrete pavement types utilizing various sample geometries

- The behavior of minors and road safety – case study of Poland

- The role of universities in efforts to increase the added value of recycled bucket tooth products through product design methods

- Adopting activated carbons on the PET depolymerization for purifying r-TPA

- Urban transportation challenges: Analysis and the mitigation strategies for road accidents, noise pollution and environmental impacts

- Enhancing the wear resistance and coefficient of friction of composite marine journal bearings utilizing nano-WC particles

- Sustainable bio-nanocomposite from lignocellulose nanofibers and HDPE for knee biomechanics: A tribological and mechanical properties study

- Effects of staggered transverse zigzag baffles and Al2O3–Cu hybrid nanofluid flow in a channel on thermofluid flow characteristics

- Mathematical modelling of Darcy–Forchheimer MHD Williamson nanofluid flow above a stretching/shrinking surface with slip conditions

- Energy efficiency and length modification of stilling basins with variable Baffle and chute block designs: A case study of the Fewa hydroelectric project

- Renewable-integrated power conversion architecture for urban heavy rail systems using bidirectional VSC and MPPT-controlled PV arrays as an auxiliary power source

- Exploitation of landfill gas vs refuse-derived fuel with landfill gas for electrical power generation in Basrah City/South of Iraq

- Two-phase numerical simulations of motile microorganisms in a 3D non-Newtonian nanofluid flow induced by chemical processes

- Sustainable cocoon waste epoxy composite solutions: Novel approach based on the deformation model using finite element analysis to determine Poisson’s ratio

- Impact and abrasion behavior of roller compacted concrete reinforced with different types of fibers

- Architectural design and its impact on daylighting in Gayo highland traditional mosques

- Structural and functional enhancement of Ni–Ti–Cu shape memory alloys via combined powder metallurgy techniques

- Design of an operational matrix method based on Haar wavelets and evolutionary algorithm for time-fractional advection–diffusion equations

- Design and optimization of a modified straight-tapered Vivaldi antenna using ANN for GPR system

- Analysis of operations of the antiresonance vibration mill of a circular trajectory of chamber vibrations

- Functions of changes in the mechanical properties of reinforcing steel under corrosive conditions

- 10.1515/eng-2025-0153

- Hybrid mechanics-informed machine learning models for predicting mechanical failure in graphene sponge: a low-data strategy for mechanical engineering applications

- Review Articles

- A modified adhesion evaluation method between asphalt and aggregate based on a pull off test and image processing

- Architectural practice process and artificial intelligence – an evolving practice

- Enhanced RRT motion planning for autonomous vehicles: a review on safety testing applications

- Special Issue: 51st KKBN - Part II

- The influence of storing mineral wool on its thermal conductivity in an open space

- Use of nondestructive test methods to determine the thickness and compressive strength of unilaterally accessible concrete components of building

- Use of modeling, BIM technology, and virtual reality in nondestructive testing and inventory, using the example of the Trzonolinowiec

- Tunable terahertz metasurface based on a modified Jerusalem cross for thin dielectric film evaluation

- Integration of SEM and acoustic emission methods in non-destructive evaluation of fiber–cement boards exposed to high temperatures

- Non-destructive method of characterizing nitrided layers in the 42CrMo4 steel using the amplitude-frequency technique of eddy currents

- Evaluation of braze welded joints using the ultrasonic method

- Analysis of the potential use of the passive magnetic method for detecting defects in welded joints made of X2CrNiMo17-12-2 steel

- Analysis of the possibility of applying a residual magnetic field for lack of fusion detection in welded joints of S235JR steel

- Eddy current methodology in the non-direct measurement of martensite during plastic deformation of SS316L

- Methodology for diagnosing hydraulic oil in production machines with the additional use of microfiltration

- Special Issue: IETAS 2024 - Part II

- Enhancing communication with elderly and stroke patients based on sign-gesture translation via audio-visual avatars

- Optimizing wireless charging for electric vehicles via a novel coil design and artificial intelligence techniques

- Evaluation of moisture damage for warm mix asphalt (WMA) containing reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP)

- Comparative CFD case study on forced convection: Analysis of constant vs variable air properties in channel flow

- Evaluating sustainable indicators for urban street network: Al-Najaf network as a case study

- Node failure in self-organized sensor networks

- Comprehensive assessment of side friction impacts on urban traffic flow: A case study of Hilla City, Iraq

- Design a system to transfer alternating electric current using six channels of laser as an embedding and transmitting source

- Security and surveillance application in 3D modeling of a smart city: Kirkuk city as a case study

- Modified biochar derived from sewage sludge for purification of lead-contaminated water

- The future of space colonisation: Architectural considerations

- Design of a Tri-band Reconfigurable Antenna Using Metamaterials for IoT Applications

- Special Issue: AESMT-7 - Part II

- Experimental study on behavior of hybrid columns by using SIFCON under eccentric load

- Special Issue: ICESTA-2024 and ICCEEAS-2024

- A selective recovery of zinc and manganese from the spent primary battery black mass as zinc hydroxide and manganese carbonate

- Special Issue: REMO 2025 and BUDIN 2025

- Predictive modeling coupled with wireless sensor networks for sustainable marine ecosystem management using real-time remote monitoring of water quality

- Management strategies for refurbishment projects: A case study of an industrial heritage building

- Structural evaluation of historical masonry walls utilizing non-destructive techniques – Comprehensive analysis

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Modification of polymers to synthesize thermo-salt-resistant stabilizers of drilling fluids

- Study of the electronic stopping power of proton in different materials according to the Bohr and Bethe theories

- AI-driven UAV system for autonomous vehicle tracking and license plate recognition

- Enhancement of the output power of a small horizontal axis wind turbine based on the optimization approach

- Design of a vertically stacked double Luneburg lens-based beam-scanning antenna at 60 GHz

- Synergistic effect of nano-silica, steel slag, and waste glass on the microstructure, electrical resistivity, and strength of ultra-high-performance concrete

- Expert evaluation of attachments (caps) for orthopaedic equipment dedicated to pedestrian road users

- Performance and rheological characteristics of hot mix asphalt modified with melamine nanopowder polymer

- Second-order design of GNSS networks with different constraints using particle swarm optimization and genetic algorithms

- Impact of including a slab effect into a 2D RC frame on the seismic fragility assessment: A comparative study

- Analytical and numerical analysis of heat transfer from radial extended surface

- Comprehensive investigation of corrosion resistance of magnesium–titanium, aluminum, and aluminum–vanadium alloys in dilute electrolytes under zero-applied potential conditions

- Performance analysis of a novel design of an engine piston for a single cylinder

- Modeling performance of different sustainable self-compacting concrete pavement types utilizing various sample geometries

- The behavior of minors and road safety – case study of Poland

- The role of universities in efforts to increase the added value of recycled bucket tooth products through product design methods

- Adopting activated carbons on the PET depolymerization for purifying r-TPA

- Urban transportation challenges: Analysis and the mitigation strategies for road accidents, noise pollution and environmental impacts

- Enhancing the wear resistance and coefficient of friction of composite marine journal bearings utilizing nano-WC particles

- Sustainable bio-nanocomposite from lignocellulose nanofibers and HDPE for knee biomechanics: A tribological and mechanical properties study

- Effects of staggered transverse zigzag baffles and Al2O3–Cu hybrid nanofluid flow in a channel on thermofluid flow characteristics

- Mathematical modelling of Darcy–Forchheimer MHD Williamson nanofluid flow above a stretching/shrinking surface with slip conditions

- Energy efficiency and length modification of stilling basins with variable Baffle and chute block designs: A case study of the Fewa hydroelectric project

- Renewable-integrated power conversion architecture for urban heavy rail systems using bidirectional VSC and MPPT-controlled PV arrays as an auxiliary power source

- Exploitation of landfill gas vs refuse-derived fuel with landfill gas for electrical power generation in Basrah City/South of Iraq

- Two-phase numerical simulations of motile microorganisms in a 3D non-Newtonian nanofluid flow induced by chemical processes

- Sustainable cocoon waste epoxy composite solutions: Novel approach based on the deformation model using finite element analysis to determine Poisson’s ratio

- Impact and abrasion behavior of roller compacted concrete reinforced with different types of fibers

- Architectural design and its impact on daylighting in Gayo highland traditional mosques

- Structural and functional enhancement of Ni–Ti–Cu shape memory alloys via combined powder metallurgy techniques

- Design of an operational matrix method based on Haar wavelets and evolutionary algorithm for time-fractional advection–diffusion equations

- Design and optimization of a modified straight-tapered Vivaldi antenna using ANN for GPR system

- Analysis of operations of the antiresonance vibration mill of a circular trajectory of chamber vibrations

- Functions of changes in the mechanical properties of reinforcing steel under corrosive conditions

- 10.1515/eng-2025-0153

- Hybrid mechanics-informed machine learning models for predicting mechanical failure in graphene sponge: a low-data strategy for mechanical engineering applications

- Review Articles

- A modified adhesion evaluation method between asphalt and aggregate based on a pull off test and image processing

- Architectural practice process and artificial intelligence – an evolving practice

- Enhanced RRT motion planning for autonomous vehicles: a review on safety testing applications

- Special Issue: 51st KKBN - Part II

- The influence of storing mineral wool on its thermal conductivity in an open space

- Use of nondestructive test methods to determine the thickness and compressive strength of unilaterally accessible concrete components of building

- Use of modeling, BIM technology, and virtual reality in nondestructive testing and inventory, using the example of the Trzonolinowiec

- Tunable terahertz metasurface based on a modified Jerusalem cross for thin dielectric film evaluation

- Integration of SEM and acoustic emission methods in non-destructive evaluation of fiber–cement boards exposed to high temperatures

- Non-destructive method of characterizing nitrided layers in the 42CrMo4 steel using the amplitude-frequency technique of eddy currents

- Evaluation of braze welded joints using the ultrasonic method

- Analysis of the potential use of the passive magnetic method for detecting defects in welded joints made of X2CrNiMo17-12-2 steel

- Analysis of the possibility of applying a residual magnetic field for lack of fusion detection in welded joints of S235JR steel

- Eddy current methodology in the non-direct measurement of martensite during plastic deformation of SS316L

- Methodology for diagnosing hydraulic oil in production machines with the additional use of microfiltration

- Special Issue: IETAS 2024 - Part II

- Enhancing communication with elderly and stroke patients based on sign-gesture translation via audio-visual avatars

- Optimizing wireless charging for electric vehicles via a novel coil design and artificial intelligence techniques

- Evaluation of moisture damage for warm mix asphalt (WMA) containing reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP)

- Comparative CFD case study on forced convection: Analysis of constant vs variable air properties in channel flow

- Evaluating sustainable indicators for urban street network: Al-Najaf network as a case study

- Node failure in self-organized sensor networks

- Comprehensive assessment of side friction impacts on urban traffic flow: A case study of Hilla City, Iraq

- Design a system to transfer alternating electric current using six channels of laser as an embedding and transmitting source

- Security and surveillance application in 3D modeling of a smart city: Kirkuk city as a case study

- Modified biochar derived from sewage sludge for purification of lead-contaminated water

- The future of space colonisation: Architectural considerations

- Design of a Tri-band Reconfigurable Antenna Using Metamaterials for IoT Applications

- Special Issue: AESMT-7 - Part II

- Experimental study on behavior of hybrid columns by using SIFCON under eccentric load

- Special Issue: ICESTA-2024 and ICCEEAS-2024

- A selective recovery of zinc and manganese from the spent primary battery black mass as zinc hydroxide and manganese carbonate

- Special Issue: REMO 2025 and BUDIN 2025

- Predictive modeling coupled with wireless sensor networks for sustainable marine ecosystem management using real-time remote monitoring of water quality

- Management strategies for refurbishment projects: A case study of an industrial heritage building

- Structural evaluation of historical masonry walls utilizing non-destructive techniques – Comprehensive analysis