Abstract

While polyethylene terephthalate (PET) recycling is crucial for environmental sustainability, existing chemical recycling methods face challenges in achieving high-purity recycled terephthalic acid (r-TPA) due to impurities generated during depolymerization. This often necessitates complex and costly purification steps, hindering the widespread adoption of r-TPA. This study presents a novel approach to enhance the purity of r-TPA by incorporating activated carbon treatment in the PET depolymerization process. Quilting cotton containing PET was depolymerized, and the resulting product was purified using activated carbons to remove impurities. The effectiveness of this method was assessed through comprehensive analyses. Remarkably, the activated carbon treatment yielded r-TPA with a high purity of 96.28%. Furthermore, the r-TPA exhibited comparable thermal properties and functional groups to virgin terephthalic acid, demonstrating that the purification process did not compromise its inherent characteristics. This approach offers a promising solution for producing high-quality r-TPA, paving the way for more efficient and sustainable PET waste management strategies.

1 Introduction

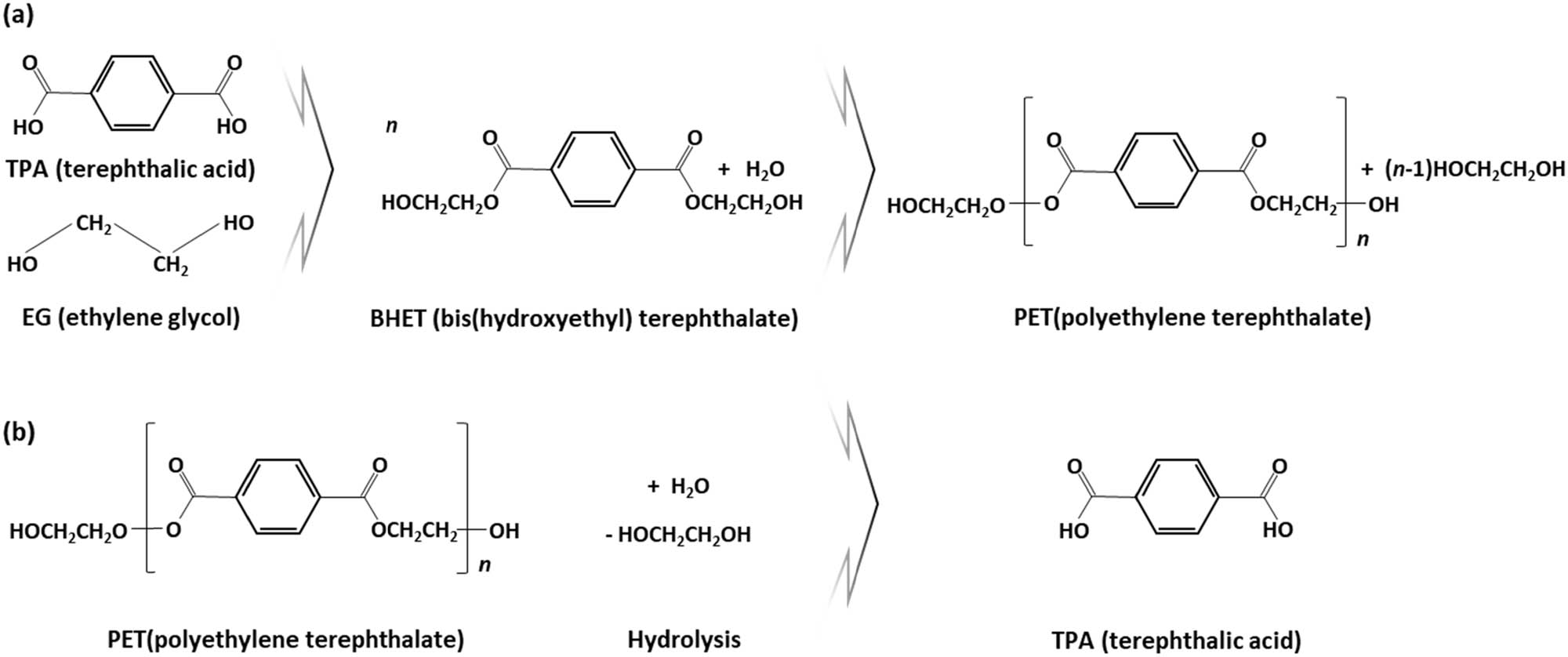

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET), a common polyester used in various applications such as packaging and textiles, is synthesized through the polymerization of ethylene glycol (EG) and terephthalic acid (TPA) or its dimethyl ester [1]. This process results in long chains of repeating ester units, contributing to desirable properties of PET, including transparency, durability, and light weight. However, the extensive use of PET has unfortunately led to a significant accumulation of plastic waste, posing substantial challenges [2,3,4]. This accumulation leads to overflowing landfills, pollution of waterways and oceans, and harm to wildlife through ingestion and entanglement. Economically, this waste represents a loss of valuable resources and necessitates costly waste management solutions. To mitigate this issue, chemical recycling has emerged as a promising strategy to convert PET waste back into its original monomers or oligomers [5,6]. Here, hydrolysis is a widely used technique that breaks down PET using water in the presence of a catalyst. These catalysts, including tetraoctylammonium bromide (TOMAB), hydrotalcite, tetrabutylammonium bromide (TBAB), and tetrabutylammonium iodide (TBAI), have demonstrated promising results in promoting the breakdown of PET [7,8,9,10]. These phase transfer catalysts enhance the solubility of reactants by shuttling ions between the aqueous and organic phases, significantly boosting the reaction rate. Despite its effectiveness, the depolymerization of PET often generates impurities that can negatively impact the purity and quality of the recycled terephthalic acid (r-TPA). These impurities can hinder the performance and limit the applications of recycled PET. To overcome this challenge, various purification techniques have been explored. In many previous studies, adsorption using activated carbon has gained considerable attention due to its efficiency, versatility, and cost-effectiveness [11,12,13]. Yet, its application in purifying r-TPA during the depolymerization process remains relatively unexplored. Previous research has primarily focused on using activated carbon for treating wastewater from PET production or removing specific contaminants from PET flakes before depolymerization.

This study aims to investigate the effects of incorporating activated carbon treatment on the purity of r-TPA during PET depolymerization. The research involves a two-step process, illustrated in Figure 1: first, depolymerizing PET via hydrolysis to break it down into its constituent monomers, and second, purifying the resulting TPA using activated carbon to remove any contaminants generated during hydrolysis. This two-step process may offer a potentially efficient and sustainable approach to PET recycling, contributing to waste reduction and valuable monomer recovery.

Two-step process to recycle PET.

2 Materials and methods

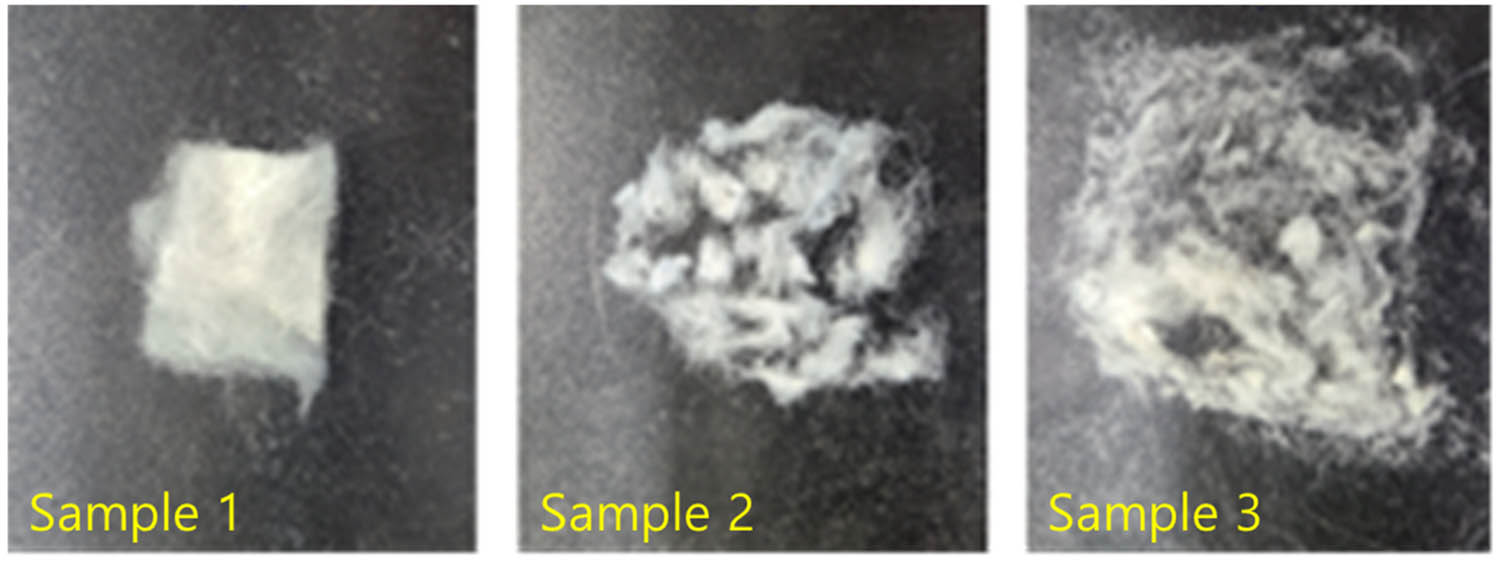

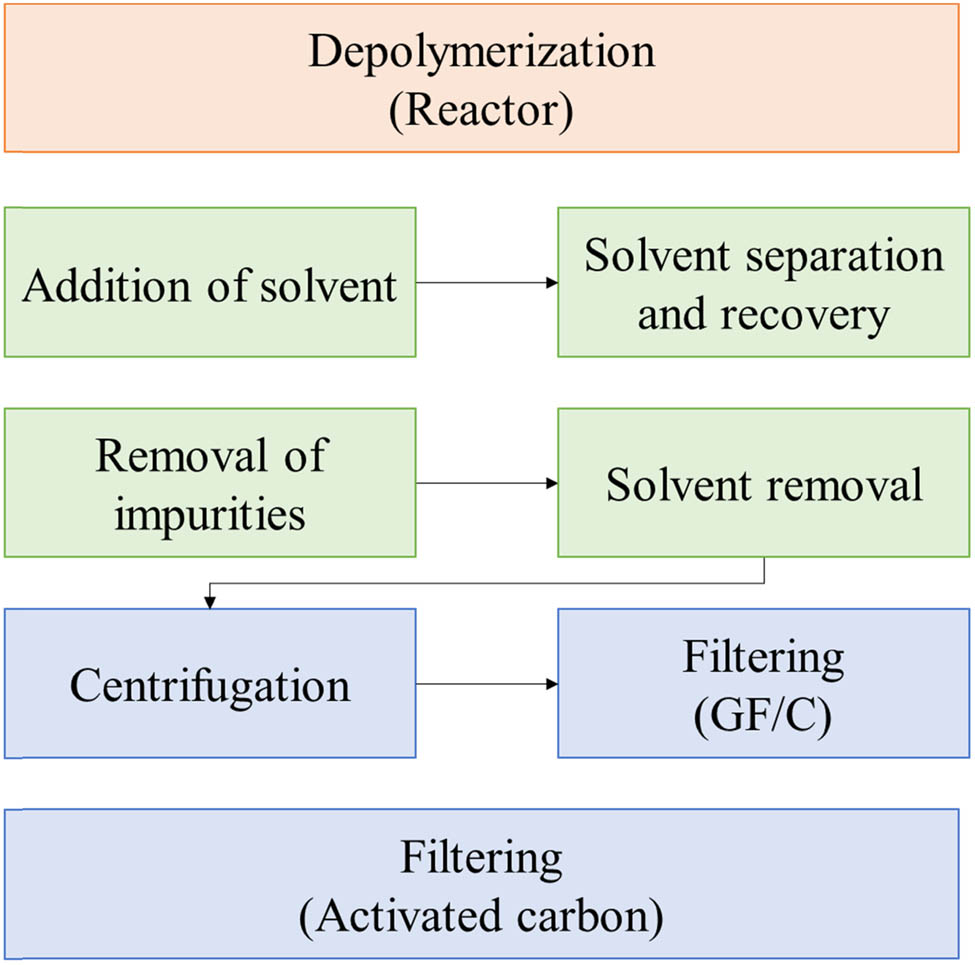

All reagents were used as received without further purification. Three quilting cotton samples were randomly collected from a municipal waste disposal site (Figure 2). The samples, which contained various impurities such as adhesives and surfactants, underwent depolymerization to recover TPA (Figure 3). Acid hydrolysis, employing a 2 M acetic acid solution at 280°C for 4 h, was used for PET depolymerization. This process facilitated an exchange reaction between the carboxylic acid and ester, resulting in the breakdown of PET into TPA and EG. TPA was then separated from EG via filtration. To enhance the purity of the recovered TPA and remove residual impurities, the solid TPA was dissolved in a NaOH solution and subjected to a multi-step purification process. This process involved centrifugation and filtration through a glass fiber filter and activated carbon. The purified sample was then isolated by titrating with HCl to a pH of 2, followed by washing.

Physical outlook of samples collected from the garbage dump.

Route for recycling PET using activated carbons to remove impurities.

Effective impurity removal is crucial in material processing. Adhesive residues in the quilting cotton samples posed a significant challenge to TPA purification using activated carbon. These residues can block pores and hinder adsorption. To address this, a centrifugation step was introduced to remove the adhesive component in the initial stage of the purification process. A Cryste VARISPIN L6R centrifuge was utilized for this purpose, operating at 300 rpm for 3 h. This centrifugation-based pre-treatment effectively removed the adhesive residues, preventing pore blockage during the subsequent activated carbon purification. The final TPA product obtained after activated carbon treatment exhibited high purity, confirming the effectiveness of this approach.

The acidity of r-TPA samples purified with activated carbons was analyzed by the following method. To confirm the amount of KOH required to neutralize free fatty acids, the degree of free fatty acids present in samples was analyzed by the reaction of R-COOH + KOH → R-COOK + H2O. Functional groups of each sample were identified using FT-IR 6100 (Jasco) through Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) analysis. Thermal properties were observed by a thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) using TGA/DSC STARRe2 (Metler Toledo). To analyze the type of contaminants, ultraviolet-visible (UV) analysis was performed using UV-1900i (Shimadzu). UV analysis was conducted within the range of 200–400 nm using a data interval of 0.1 nm and a medium scan speed. For a better insight in the regeneration efficiency using carbonaceous materials, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis was added to UV using 1200 Infinity Series (Agilent) referring to the standard (ASTM D 7884-20).

3 Results and discussion

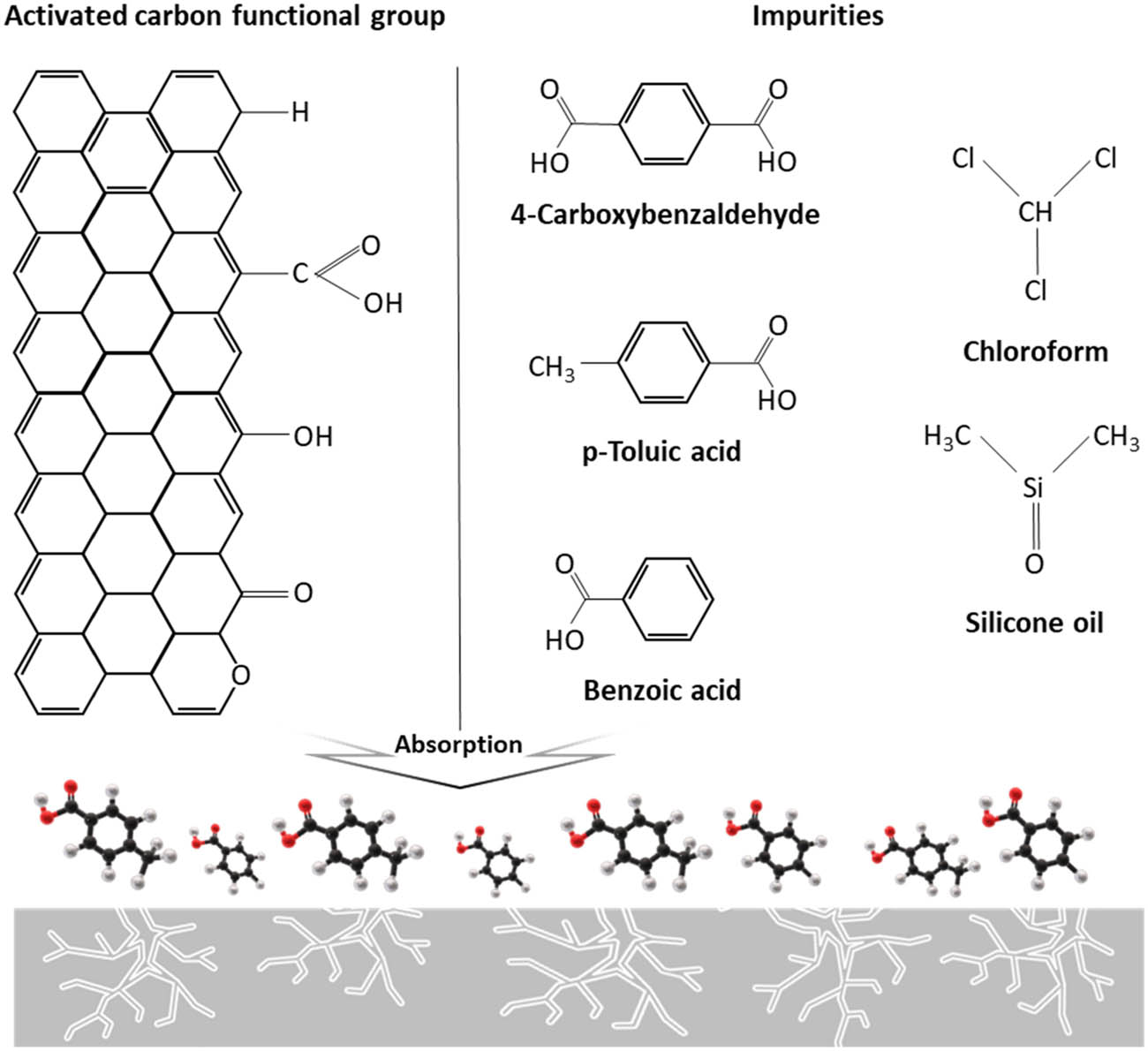

The depolymerization of PET can generate various contaminants, including silicone oil, chloroform, benzoic acid, p-toluic acid, and 4-carboxybenzaldehyde. Figure 4 illustrates the physicochemical adsorption mechanism of these contaminants by activated carbon.

Physiochemical adsorption mechanism of contaminants via functional groups on the surface of activated carbon.

The process involves physisorption, where contaminants are absorbed into the micro-, meso-, and/or macro-pores of the activated carbon via van der Waals forces. This mechanism is consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated the effectiveness of activated carbon in removing a wide range of organic contaminants from aqueous solutions through physisorption [14,15]. The remaining contaminants, which may not be effectively removed through physisorption, are subsequently adsorbed onto the surface functional groups of the activated carbon. This secondary adsorption mechanism can involve various interactions, such as electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and π–π interactions, depending on the nature of the contaminants and the surface chemistry of the activated carbon [16].

To analyze the TPA yield in the PET depolymerization process and TPA production, Equations (1) and (2) were applied [17]. The principle is to assess the efficiency of the TPA production process by determining how much of the potential TPA is actually obtained. A higher yield indicates a more efficient process with minimal losses due to side reactions, incomplete conversion, or purification issues. The calculated result showed a yield of 91.5% each.

The acidity of the r-TPA samples was analyzed according to the American Society for Testing and Materials D 8032-20 standard and compared to a reference TPA sample. As shown in Table 1, the reference sample exhibited an acidity of 675 mg KOH/g. Samples 1 and 2 showed minor deviations within an error range of ± 1 mg KOH/g compared to the reference sample, while Sample 3 displayed an acidity value identical to the reference sample. These results indicate that the activated carbon treatment did not significantly alter the acidity of the r-TPA. This finding is crucial because the acidity of TPA can influence its reactivity and performance in subsequent polymerization reactions to produce recycled PET.

Acidity of samples after the purification via activated carbons

| Test items | Unit | Test result | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference sample | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 | ||

| Acid value | mg KOH/g | 675 | 676 | 674 | 675 |

HPLC-UV analysis was conducted to determine the levels of contaminants in the r-TPA samples. The reference sample showed trace amounts of 4-carboxybenzaldehyde, benzoic acid, and p-toluic acid (Figure 5). In contrast, Samples 2 and 3 were free of these contaminants, indicating the effectiveness of the activated carbon treatment in removing these impurities. Interestingly, Sample 1 exhibited a significant increase in 4-carboxybenzaldehyde content compared to the reference sample, along with a minor amount of p-toluic acid. This observation suggests that the depolymerization process, particularly for Sample 1, may have favored the formation of 4-carboxybenzaldehyde, possibly through the oxidation of p-toluic acid or other intermediates.

HPLC-UV analyses of the reference sample and Sample 1.

The results from Figures 4 and 5 suggest that the physical state of the PET waste can influence the effectiveness of activated carbon treatment. Samples that were physically less damaged, such as Sample 1, may have exhibited stronger cross-linking between the contaminants and the PET matrix, hindering the access of activated carbon to these contaminants. This highlights the importance of proper pre-treatment of PET waste, such as shredding or grinding, to enhance the efficiency of activated carbon treatment.

FT-IR analysis was performed to assess the impact of 4-carboxybenzaldehyde on the functional groups of r-TPA (Figure 6(a)). The characteristic functional groups identified in each sample are listed in Table 2. All samples, including the reference and r-TPA samples, exhibited similar FT-IR spectra, indicating the presence of C–H phenyl stretching, C═O stretching, OH group, C–O stretching, C═C stretching, C–OH deformation, and C–H out-of-plane bands [18,19]. This consistency in the FT-IR spectra suggests that the activated carbon treatment did not significantly alter the functional groups of r-TPA, even in the presence of residual 4-carboxybenzaldehyde.

FT-IR results are shown in (a), while TGA and DSC results are shown in (b) and (c), respectively.

Wavenumber and the corresponding functional groups of samples

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Functional group |

|---|---|

| ≒ 3,000–2,840 | C–H Phenyl stretching band |

| ≒ 1,680 | C═O stretching band |

| ≒ 1,440–1,395 | OH group band |

| ≒ 1,315–1,280 | C–O stretching band |

| ≒ 1,135 | C═C stretching band |

| ≒ 1,111 | C–OH deformation band |

| ≒ 780 | C–H out of plane band |

TGA was conducted to evaluate the thermal stability of the r-TPA samples and to identify any undetected contaminants (Figure 6(b) and Table 3). The TGA curves of all samples, except Sample 3, exhibited similar thermal characteristics. This similarity indicates that the activated carbon treatment did not significantly affect the thermal stability of r-TPA. The deviation observed for Sample 3, which was physically damaged during collection, suggests that the physical state of the r-TPA can influence its thermal behavior. The relatively weak cross-linking in Sample 3 may have contributed to its altered thermal characteristics.

Numerical data set of TGA results

| Sample | Thermal decomposition (%) | Pyrolysis temperature (°C) | Residual mass (%, 800°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample 1 | 99.57 | 337.3 | 1.13 |

| Sample 2 | 99.12 | 320.7 | 2.06 |

| Sample 3 | 96.15 | 307.7 | 6.34 |

| Reference | 99.98 | 337.3 | 0.63 |

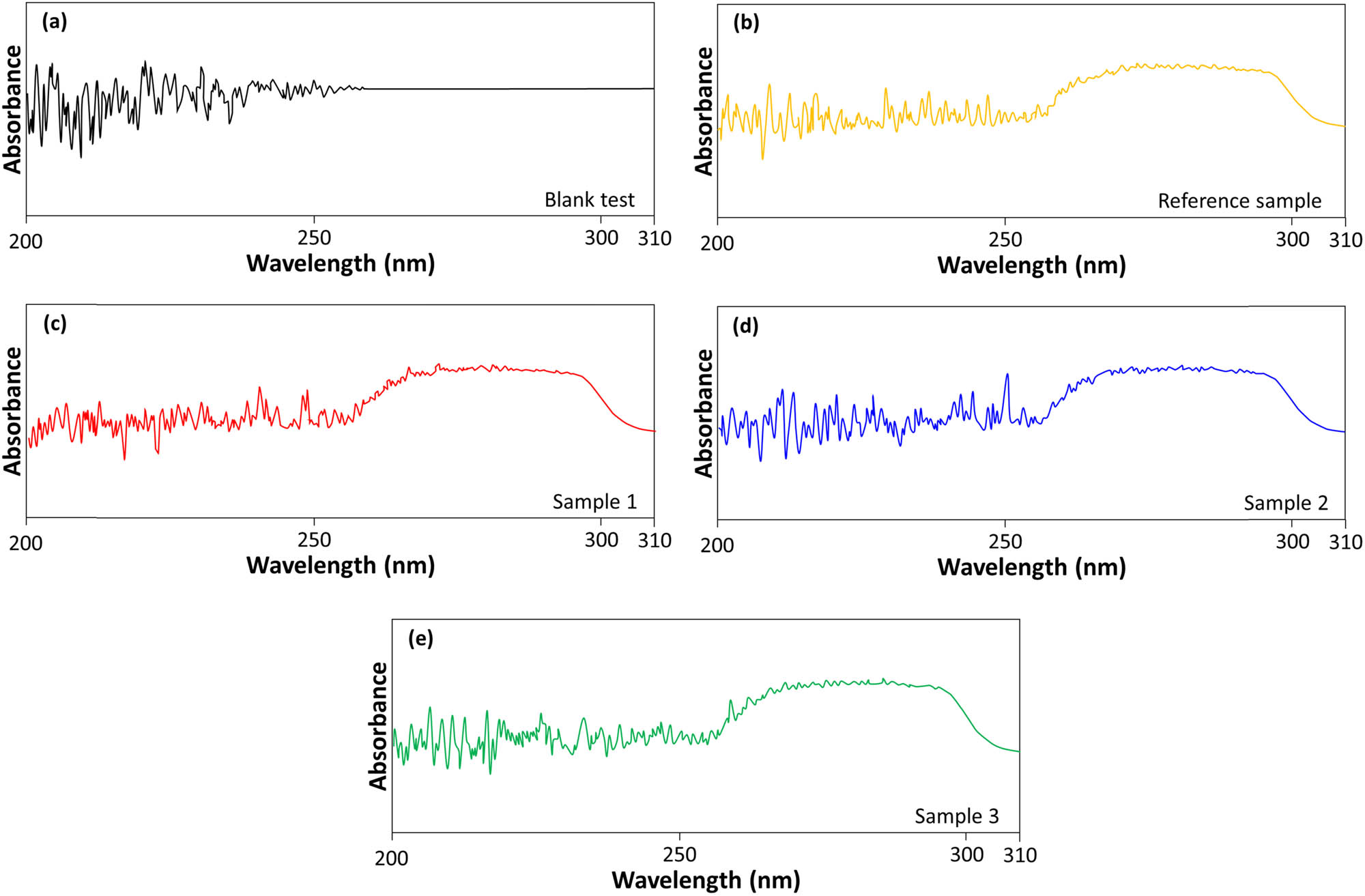

UV absorbance analysis was performed to further characterize the r-TPA samples (Figure 7). All samples showed a similar absorbance pattern in the 200–400 nm range. Figure 7(b)–(d) exhibited a slight increase in the peak around 250 nm, which, considering the margin of error, suggests the presence of residual TPA. However, Figure 7(e) showed a negligible peak at 250 nm and a distinct peak increase at 260 nm, indicating the presence of organic impurities other than TPA. These findings highlight the importance of optimizing the activated carbon treatment process to minimize residual impurities in r-TPA.

UV absorbance analysis of (a) blank test, (b) reference sample, (c) Sample 1, (d) Sample 2, and (e) Sample 3.

The r-TPA content in the samples was quantified using HPLC analysis, and the numerical values were calculated using Equation (3) (Table 4). Here, A, B, V, D, and W refer to the concentration of TPA in HPLC measured test solution (μg/mL), the concentration of TPA in HPLC measured blank solution (μg/mL), the amount of test solution (mL), the dilution of test solution (g), and the sampling amount (g), 10,000: unit conversion coefficient (μg/mL, ppm → %). The results revealed that Sample 1 had an average TPA content of 96.22%, Sample 2 had 94.56%, and Sample 3 had 94.90%. In comparison, the reference sample had an average TPA content of 97.52%. These values are higher than those reported for hydrolysis using TBAI as a catalyst (90%) but lower than those achieved with TOMAB and TBAB catalysts (99%) [20]. However, it is important to consider that the activated carbon treatment is a relatively environmentally friendly and cost-effective purification method compared to catalyst-based approaches.

Results of TPA content analysis using HPLC

| Test item | Unit | Test result | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 | Reference | ||

| TPA content | % | 96.28 | 94.52 | 94.96 | 97.50 |

| 96.14 | 94.59 | 94.77 | |||

| 96.25 | 94.27 | 94.99 | |||

| Average: 96.22 | Average: 94.56 | Average: 94.90 | |||

4 Conclusions

This study investigated a novel approach to purifying r-TPA obtained from the depolymerization of post-consumer PET waste, specifically quilting cotton, using activated carbon. The two-step process involved acid hydrolysis of the PET followed by purification of the resulting r-TPA with activated carbon. The results demonstrated the potential of this method to produce high-purity r-TPA, achieving a purity of 96.28% and a yield of 91.5%. The characterization of the r-TPA samples also revealed important insights. Acidity measurements indicated that the activated carbon treatment did not significantly alter the acidity of the r-TPA. HPLC analysis confirmed the effectiveness of activated carbon in removing contaminants such as 4-carboxybenzaldehyde, benzoic acid, and p-toluic acid. FT-IR analysis confirmed the preservation of the expected functional groups in the r-TPA. TGA results corroborated this, showing consistent thermal stability between r-TPA and reference for most samples, except Sample 3, which was noted as being physically compromised. UV analysis indicated the presence of residual TPA and other organic impurities, reinforcing the need for optimization and further research. By addressing these future research directions, the activated carbon purification method can be further refined and optimized for large-scale implementation, contributing significantly to more sustainable PET waste management and a circular economy.

-

Funding information: We thank Korea Evaluation Institute of Industrial Technology (KEIT) for supporting our research (00155462).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. Woo Seok Cho (Ph.D. student) conducted conceptualization, methodology, wrote the original draft, and finalized the manuscript. Joon Hyuk Lee (Ph.D) helped analyze the results and assisted in the experiments. Da Yun Na (Master student) assisted in the experiments. Sang Sun Choi (Professor) reviewed the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Singh AK, Bedi R, Kaith BS. Composite materials based on recycled polyethylene terephthalate and their properties–A comprehensive review. Compos B Eng. 2021;219:108928.10.1016/j.compositesb.2021.108928Search in Google Scholar

[2] Jambeck JR, Geyer R, Wilcox C, Siegler TR, Perryman M, Andrady A, et al. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science. 2015;347:768–71.10.1126/science.1260352Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Lebreton LCM, Slat B, Ferrari F, Sainte-Rose B, Aitken J, Marthouse R, et al. Evidence that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is rapidly accumulating plastic. Sci Rep. 2018;8:4666.10.1038/s41598-018-22939-wSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Geyer R, Jambeck JR, Law KL. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci Adv. 2017;3:e1700782.10.1126/sciadv.1700782Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Ben Zair MM, Jakarni FM, Muniandy R, Hassim S. A brief review: application of recycled polyethylene terephthalate in asphalt pavement reinforcement. Sustainability. 2021;13(3):1303.10.3390/su13031303Search in Google Scholar

[6] Bharadwaj C, Purbey R, Bora D, Chetia P, Maheswari RU, Duarah R, et al. A review on sustainable PET recycling: Strategies and trends. Mater Today Sustain. 2024;27:100936.10.1016/j.mtsust.2024.100936Search in Google Scholar

[7] Karayannidis G, Chatziavgoustis A, Achilias D. Poly(ethylene terephthalate) recycling and recovery of pure terephthalic acid by alkaline hydrolysis. Adv Polym Technol J Polym Process Inst. 2002;21:250–9.10.1002/adv.10029Search in Google Scholar

[8] Siddiqui MN, Achilias DS, Redhwi HH, Bikiaris DN, Katsogiannis KAG, Karayannidis GP. Hydrolytic depolymerization of PET in a microwave reactor. Macromol Mater Eng. 2010;295:575–84.10.1002/mame.201000050Search in Google Scholar

[9] Khalaf HI, Hasan OA. Effect of quaternary ammonium salt as a phase transfer catalyst for the microwave depolymerization of polyethylene terephthalate waste bottles. Chem Eng J. 2012;192:45–8.10.1016/j.cej.2012.03.081Search in Google Scholar

[10] Paliwal NR, Mungray AK. Ultrasound assisted alkaline hydrolysis of poly(ethylene terephthalate) in presence of phase transfer catalyst. Polym Degrad Stab. 2013;98:2094–101.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2013.06.030Search in Google Scholar

[11] Lee JH, Sim SJ, Kang JH, Choi SS. Isotherm and thermodynamic modelling of malachite green on CO2-activated carbon fibers. Chem Phys Lett. 2021;780:138962.10.1016/j.cplett.2021.138962Search in Google Scholar

[12] Yang X, Wan Y, Zheng Y, He F, Yu Z, Huang J, et al. Surface functional groups of carbon-based adsorbents and their roles in the removal of heavy metals from aqueous solutions: a critical review. Chem Eng J. 2019;366:608–21.10.1016/j.cej.2019.02.119Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Lee JH, Lee SH, Suh DH. Using nanobubblized carbon dioxide for effective microextraction of heavy metals. J CO2 Util. 2020;39:101163.10.1016/j.jcou.2020.101163Search in Google Scholar

[14] Atif M, Haider HZ, Bongiovanni R, Fayyaz M, Razzaq T, Gul S. Physisorption and chemisorption trends in surface modification of carbon black. Surf Interfaces. 2022;31:102080.10.1016/j.surfin.2022.102080Search in Google Scholar

[15] El Maguana Y, Elhadiri N, Benchanaa M, Chikri R. Activated carbon for dyes removal: modeling and understanding the adsorption process. J Chem. 2020;2020(1):2096834.10.1155/2020/2096834Search in Google Scholar

[16] Choi SS, Lee SH, Yun KJ, Jin YM, Lee JH. High entropy allows a better affinity between metal ions and activated carbon fibers. Mater Technol. 2021;55(5):603–7.10.17222/mit.2020.202Search in Google Scholar

[17] Peng Y, Yang J, Deng C, Deng J, Shen L, Fu Y. Acetolysis of waste polyethylene terephthalate for upcycling and life-cycle assessment study. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):3249.10.1038/s41467-023-38998-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Ioakeimidis C, Fotopoulou KN, Karapanagioti HK, Geraga M, Zeri C, Papathanassiou E, et al. The degradation potential of PET bottles in the marine environment: An ATR-FTIR based approach. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):23501.10.1038/srep23501Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Tabary SAAB, Fayazfar HR. Circular economy solutions for plastic waste: improving rheological properties of recycled polyethylene terephthalate (r-PET) for direct 3D printing. Prog Addit Manuf. 2024;1–10.10.1007/s40964-024-00784-wSearch in Google Scholar

[20] Enache AC, Grecu I, Samoila P. Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) recycled by catalytic glycolysis: A bridge toward circular economy principles. Materials. 2024;17(12):2991.10.3390/ma17122991Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Modification of polymers to synthesize thermo-salt-resistant stabilizers of drilling fluids

- Study of the electronic stopping power of proton in different materials according to the Bohr and Bethe theories

- AI-driven UAV system for autonomous vehicle tracking and license plate recognition

- Enhancement of the output power of a small horizontal axis wind turbine based on the optimization approach

- Design of a vertically stacked double Luneburg lens-based beam-scanning antenna at 60 GHz

- Synergistic effect of nano-silica, steel slag, and waste glass on the microstructure, electrical resistivity, and strength of ultra-high-performance concrete

- Expert evaluation of attachments (caps) for orthopaedic equipment dedicated to pedestrian road users

- Performance and rheological characteristics of hot mix asphalt modified with melamine nanopowder polymer

- Second-order design of GNSS networks with different constraints using particle swarm optimization and genetic algorithms

- Impact of including a slab effect into a 2D RC frame on the seismic fragility assessment: A comparative study

- Analytical and numerical analysis of heat transfer from radial extended surface

- Comprehensive investigation of corrosion resistance of magnesium–titanium, aluminum, and aluminum–vanadium alloys in dilute electrolytes under zero-applied potential conditions

- Performance analysis of a novel design of an engine piston for a single cylinder

- Modeling performance of different sustainable self-compacting concrete pavement types utilizing various sample geometries

- The behavior of minors and road safety – case study of Poland

- The role of universities in efforts to increase the added value of recycled bucket tooth products through product design methods

- Adopting activated carbons on the PET depolymerization for purifying r-TPA

- Urban transportation challenges: Analysis and the mitigation strategies for road accidents, noise pollution and environmental impacts

- Enhancing the wear resistance and coefficient of friction of composite marine journal bearings utilizing nano-WC particles

- Sustainable bio-nanocomposite from lignocellulose nanofibers and HDPE for knee biomechanics: A tribological and mechanical properties study

- Effects of staggered transverse zigzag baffles and Al2O3–Cu hybrid nanofluid flow in a channel on thermofluid flow characteristics

- Mathematical modelling of Darcy–Forchheimer MHD Williamson nanofluid flow above a stretching/shrinking surface with slip conditions

- Energy efficiency and length modification of stilling basins with variable Baffle and chute block designs: A case study of the Fewa hydroelectric project

- Renewable-integrated power conversion architecture for urban heavy rail systems using bidirectional VSC and MPPT-controlled PV arrays as an auxiliary power source

- Exploitation of landfill gas vs refuse-derived fuel with landfill gas for electrical power generation in Basrah City/South of Iraq

- Two-phase numerical simulations of motile microorganisms in a 3D non-Newtonian nanofluid flow induced by chemical processes

- Sustainable cocoon waste epoxy composite solutions: Novel approach based on the deformation model using finite element analysis to determine Poisson’s ratio

- Impact and abrasion behavior of roller compacted concrete reinforced with different types of fibers

- Architectural design and its impact on daylighting in Gayo highland traditional mosques

- Structural and functional enhancement of Ni–Ti–Cu shape memory alloys via combined powder metallurgy techniques

- Design of an operational matrix method based on Haar wavelets and evolutionary algorithm for time-fractional advection–diffusion equations

- Design and optimization of a modified straight-tapered Vivaldi antenna using ANN for GPR system

- Analysis of operations of the antiresonance vibration mill of a circular trajectory of chamber vibrations

- Functions of changes in the mechanical properties of reinforcing steel under corrosive conditions

- 10.1515/eng-2025-0153

- Review Articles

- A modified adhesion evaluation method between asphalt and aggregate based on a pull off test and image processing

- Architectural practice process and artificial intelligence – an evolving practice

- Enhanced RRT motion planning for autonomous vehicles: a review on safety testing applications

- Special Issue: 51st KKBN - Part II

- The influence of storing mineral wool on its thermal conductivity in an open space

- Use of nondestructive test methods to determine the thickness and compressive strength of unilaterally accessible concrete components of building

- Use of modeling, BIM technology, and virtual reality in nondestructive testing and inventory, using the example of the Trzonolinowiec

- Tunable terahertz metasurface based on a modified Jerusalem cross for thin dielectric film evaluation

- Integration of SEM and acoustic emission methods in non-destructive evaluation of fiber–cement boards exposed to high temperatures

- Non-destructive method of characterizing nitrided layers in the 42CrMo4 steel using the amplitude-frequency technique of eddy currents

- Evaluation of braze welded joints using the ultrasonic method

- Analysis of the potential use of the passive magnetic method for detecting defects in welded joints made of X2CrNiMo17-12-2 steel

- Analysis of the possibility of applying a residual magnetic field for lack of fusion detection in welded joints of S235JR steel

- Eddy current methodology in the non-direct measurement of martensite during plastic deformation of SS316L

- Methodology for diagnosing hydraulic oil in production machines with the additional use of microfiltration

- Special Issue: IETAS 2024 - Part II

- Enhancing communication with elderly and stroke patients based on sign-gesture translation via audio-visual avatars

- Optimizing wireless charging for electric vehicles via a novel coil design and artificial intelligence techniques

- Evaluation of moisture damage for warm mix asphalt (WMA) containing reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP)

- Comparative CFD case study on forced convection: Analysis of constant vs variable air properties in channel flow

- Evaluating sustainable indicators for urban street network: Al-Najaf network as a case study

- Node failure in self-organized sensor networks

- Comprehensive assessment of side friction impacts on urban traffic flow: A case study of Hilla City, Iraq

- Design a system to transfer alternating electric current using six channels of laser as an embedding and transmitting source

- Security and surveillance application in 3D modeling of a smart city: Kirkuk city as a case study

- Modified biochar derived from sewage sludge for purification of lead-contaminated water

- The future of space colonisation: Architectural considerations

- Design of a Tri-band Reconfigurable Antenna Using Metamaterials for IoT Applications

- Special Issue: AESMT-7 - Part II

- Experimental study on behavior of hybrid columns by using SIFCON under eccentric load

- Special Issue: ICESTA-2024 and ICCEEAS-2024

- A selective recovery of zinc and manganese from the spent primary battery black mass as zinc hydroxide and manganese carbonate

- Special Issue: REMO 2025 and BUDIN 2025

- Predictive modeling coupled with wireless sensor networks for sustainable marine ecosystem management using real-time remote monitoring of water quality

- Management strategies for refurbishment projects: A case study of an industrial heritage building

- Structural evaluation of historical masonry walls utilizing non-destructive techniques – Comprehensive analysis

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Modification of polymers to synthesize thermo-salt-resistant stabilizers of drilling fluids

- Study of the electronic stopping power of proton in different materials according to the Bohr and Bethe theories

- AI-driven UAV system for autonomous vehicle tracking and license plate recognition

- Enhancement of the output power of a small horizontal axis wind turbine based on the optimization approach

- Design of a vertically stacked double Luneburg lens-based beam-scanning antenna at 60 GHz

- Synergistic effect of nano-silica, steel slag, and waste glass on the microstructure, electrical resistivity, and strength of ultra-high-performance concrete

- Expert evaluation of attachments (caps) for orthopaedic equipment dedicated to pedestrian road users

- Performance and rheological characteristics of hot mix asphalt modified with melamine nanopowder polymer

- Second-order design of GNSS networks with different constraints using particle swarm optimization and genetic algorithms

- Impact of including a slab effect into a 2D RC frame on the seismic fragility assessment: A comparative study

- Analytical and numerical analysis of heat transfer from radial extended surface

- Comprehensive investigation of corrosion resistance of magnesium–titanium, aluminum, and aluminum–vanadium alloys in dilute electrolytes under zero-applied potential conditions

- Performance analysis of a novel design of an engine piston for a single cylinder

- Modeling performance of different sustainable self-compacting concrete pavement types utilizing various sample geometries

- The behavior of minors and road safety – case study of Poland

- The role of universities in efforts to increase the added value of recycled bucket tooth products through product design methods

- Adopting activated carbons on the PET depolymerization for purifying r-TPA

- Urban transportation challenges: Analysis and the mitigation strategies for road accidents, noise pollution and environmental impacts

- Enhancing the wear resistance and coefficient of friction of composite marine journal bearings utilizing nano-WC particles

- Sustainable bio-nanocomposite from lignocellulose nanofibers and HDPE for knee biomechanics: A tribological and mechanical properties study

- Effects of staggered transverse zigzag baffles and Al2O3–Cu hybrid nanofluid flow in a channel on thermofluid flow characteristics

- Mathematical modelling of Darcy–Forchheimer MHD Williamson nanofluid flow above a stretching/shrinking surface with slip conditions

- Energy efficiency and length modification of stilling basins with variable Baffle and chute block designs: A case study of the Fewa hydroelectric project

- Renewable-integrated power conversion architecture for urban heavy rail systems using bidirectional VSC and MPPT-controlled PV arrays as an auxiliary power source

- Exploitation of landfill gas vs refuse-derived fuel with landfill gas for electrical power generation in Basrah City/South of Iraq

- Two-phase numerical simulations of motile microorganisms in a 3D non-Newtonian nanofluid flow induced by chemical processes

- Sustainable cocoon waste epoxy composite solutions: Novel approach based on the deformation model using finite element analysis to determine Poisson’s ratio

- Impact and abrasion behavior of roller compacted concrete reinforced with different types of fibers

- Architectural design and its impact on daylighting in Gayo highland traditional mosques

- Structural and functional enhancement of Ni–Ti–Cu shape memory alloys via combined powder metallurgy techniques

- Design of an operational matrix method based on Haar wavelets and evolutionary algorithm for time-fractional advection–diffusion equations

- Design and optimization of a modified straight-tapered Vivaldi antenna using ANN for GPR system

- Analysis of operations of the antiresonance vibration mill of a circular trajectory of chamber vibrations

- Functions of changes in the mechanical properties of reinforcing steel under corrosive conditions

- 10.1515/eng-2025-0153

- Review Articles

- A modified adhesion evaluation method between asphalt and aggregate based on a pull off test and image processing

- Architectural practice process and artificial intelligence – an evolving practice

- Enhanced RRT motion planning for autonomous vehicles: a review on safety testing applications

- Special Issue: 51st KKBN - Part II

- The influence of storing mineral wool on its thermal conductivity in an open space

- Use of nondestructive test methods to determine the thickness and compressive strength of unilaterally accessible concrete components of building

- Use of modeling, BIM technology, and virtual reality in nondestructive testing and inventory, using the example of the Trzonolinowiec

- Tunable terahertz metasurface based on a modified Jerusalem cross for thin dielectric film evaluation

- Integration of SEM and acoustic emission methods in non-destructive evaluation of fiber–cement boards exposed to high temperatures

- Non-destructive method of characterizing nitrided layers in the 42CrMo4 steel using the amplitude-frequency technique of eddy currents

- Evaluation of braze welded joints using the ultrasonic method

- Analysis of the potential use of the passive magnetic method for detecting defects in welded joints made of X2CrNiMo17-12-2 steel

- Analysis of the possibility of applying a residual magnetic field for lack of fusion detection in welded joints of S235JR steel

- Eddy current methodology in the non-direct measurement of martensite during plastic deformation of SS316L

- Methodology for diagnosing hydraulic oil in production machines with the additional use of microfiltration

- Special Issue: IETAS 2024 - Part II

- Enhancing communication with elderly and stroke patients based on sign-gesture translation via audio-visual avatars

- Optimizing wireless charging for electric vehicles via a novel coil design and artificial intelligence techniques

- Evaluation of moisture damage for warm mix asphalt (WMA) containing reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP)

- Comparative CFD case study on forced convection: Analysis of constant vs variable air properties in channel flow

- Evaluating sustainable indicators for urban street network: Al-Najaf network as a case study

- Node failure in self-organized sensor networks

- Comprehensive assessment of side friction impacts on urban traffic flow: A case study of Hilla City, Iraq

- Design a system to transfer alternating electric current using six channels of laser as an embedding and transmitting source

- Security and surveillance application in 3D modeling of a smart city: Kirkuk city as a case study

- Modified biochar derived from sewage sludge for purification of lead-contaminated water

- The future of space colonisation: Architectural considerations

- Design of a Tri-band Reconfigurable Antenna Using Metamaterials for IoT Applications

- Special Issue: AESMT-7 - Part II

- Experimental study on behavior of hybrid columns by using SIFCON under eccentric load

- Special Issue: ICESTA-2024 and ICCEEAS-2024

- A selective recovery of zinc and manganese from the spent primary battery black mass as zinc hydroxide and manganese carbonate

- Special Issue: REMO 2025 and BUDIN 2025

- Predictive modeling coupled with wireless sensor networks for sustainable marine ecosystem management using real-time remote monitoring of water quality

- Management strategies for refurbishment projects: A case study of an industrial heritage building

- Structural evaluation of historical masonry walls utilizing non-destructive techniques – Comprehensive analysis