Abstract

Warm mix asphalt (WMA) has attracted a lot of interest and attention from the pavement industry since it was introduced as a potential solution to replace traditional hot mix asphalt (HMA). Although WMA has several advantages over HMA pavements, such as lower fuel consumption and emissions, conclusive answers about the feasibility of this replacement have not yet been provided. One of the main issues with WMA is its susceptibility to damage caused by moisture; so, it needs to be monitored and quantified. It is necessary to investigate the feasibility of using locally accessible materials for this technology. Therefore, locally reclaimed asphalt taken from one of the affected streets will be used and the effect of moisture on WMA will be evaluated using different proportions of this reclaimed asphalt. In addition, three types of mineral filler materials, which are available locally will be used. This research presents an experimental investigation aiming at characterizing the mechanical performance of WMA mixes intended for sustainable pavement construction that contains varying percentages of recovered asphalt pavement (RAP) and natural zeolite. One reference HMA and 12 different types of WMA mixtures made with 0.3% zeolite were tested. For each kind of WMA, three filler types – cement, limestone, and hydrated lime – and different RAP contents – 0, 10, 20, and 30% – were utilized. For each type of mixture, a moisture sensitivity test was conducted to determine its moisture resistance. According to the results, the majority of warm combinations, which contain RAP in their mix, met the AASHTO-mandated minimum tensile strength ratio of 80%, but other mixtures did not, indicating that warm mixtures’ moisture resistance is a cause for worry. However, note that the utilization of RAP in WMA enhanced the behavior aspects of asphalt mixes, such as moisture resistance.

1 Introduction

Building environmentally friendly and sustainable transportation infrastructure saves natural resources, protects the environment, and uses less energy [1,2]. Additionally, in today’s world, it is crucial to restrict carbon emissions, reduce dangerous gasses, and save fuel. For these reasons, the pavement sectors are searching for different techniques to lower the temperature at which asphalt concrete is produced [3]. When warm mix asphalt (WMA) was first deployed, green construction was recognized by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) in a 2007 study. In Europe, WMA technologies have been in use for about a decade, with positive outcomes. According to Yee and Hamzah [4], warm mixes can be made more workable by heating them to a lower temperature. Numerous investigations were conducted on a wide range of WMA combinations with various properties, both in the lab and in real-world settings, evaluating their efficacy against traditional hot mix asphalt (HMA) mixtures.

A new WMA technology, beginning to transition from the theoretical to the practical field, is investigated. Despite the first experiments at WMA that began in America in 2004, the technology was investigated in Europe between 1999 and 2001 [5,6]. Currently, WMA makes up roughly 30% of all asphalt concrete mixes produced locally in the United States [7]. Based on the kind of additives used to create WMA, the mixing and compaction temperatures of this form of asphalt concrete are typically less than the temperatures for HMA concrete by 15–40°C. This means that the manufacturing processes for these two types of asphalt concrete are different. The decrease in fuel expenses for heating the raw materials, along with the reduced carbon dioxide emissions, led to both economic and environmental benefits. While WMA has been produced in millions of tons globally since the late 1990s and is widely utilized for paving projects, Iraq has not yet employed this kind of mix. In 2006, Barthel et al. [8] first reported on the creation of WMA with the utilization of zeolite in 2004 [7]. As temperature increases beyond 100°C, the synthetic zeolite, known as Aspha-min or Advera will be a compound consisting of sodium aluminum silicate and 21% of its mass is crystallized water. This results in a foaming effect and increases the workability of the mix since the binder viscosity is lowered [9]. Aspha-min is normally added to the mixture either before or along with the binder, at a rate of 0.3% by weight of the entire mixture. The two primary issues with the use of WMA have been an increased risk of moisture damage and rutting. Moisture damage was described as “the progressive functional deterioration of a pavement mixture by loss of the adhesive bond between the asphalt cement and the aggregate surface and/or loss of the cohesive resistance within the asphalt cement principally from the action of water” by Kiggundu and Roberts (1988, p. 3) [10,11] The presence of both water and traffic significantly induces moisture damage in the field. [12,13,14,15]. Moisture damage is frequently a gradual process of failure and can sometimes result in rapid irreversible deformation, either before or without the loss of adhesion [13].

Multiple researchers have documented that the partially dehydrated aggregates at lower mixing temperatures in WMA can form a weak connection with the asphalt binder, making it susceptible to degradation when exposed to water [16,17,18,19,20]. Prior research has demonstrated varying levels of moisture damage susceptibility in WMA mixtures, based upon the specific technologies and procedures employed. For instance, the Sasobit® modified WMA mix and HMA mix showed comparable tensile strength ratio (TSR) values, according to Goh and You [21]. The moisture damage performance of Evotherm® and Sasobit® WMA and HMA mixes, which were utilized to build field test sections, was also examined by Hurley et al. [22], who found that both mixes functioned similarly well.

The impact of the utilization of Aspha-min on the associated performance parameters of WMA was examined by Hurley and Prowell [23]. The temperatures at which mixes were compacted were 149, 129, 110, and 88°C. The blending temperature was approximately 19°C above the compacting temperature. According to their findings, the moisture-induced damage, as measured by the ratio of tensile force, had decreased in WMA in comparison to HMA. In 2008, Bhusal [24] carried out laboratory research to assess the possibility of moisture damage, ruts characteristics, and the dynamic modulus for WMA employing both kinds of additions (Sasobit and Aspha-min). When these outcomes were contrasted with an HMA reference, it became clear that neither the WMA nor the Control HMA met the required TSR criterion of 80%; instead, the Sasobit produced the greatest TSR and conditioned indirect tensile strength (ITS) values. The findings of the Hamburg wheel tracking show that, as compared to the control HMA and the WMA with Aspha-min, a WMA containing Sasobit has the best level of rut challenge. In the year 2010, Zhang [25] produced WMA using three different types of additives and compared its performance with HMA, which also included the same additives: Advera (synthetic zeolite), Evotherm, and Sasobit. The author carried out several laboratory studies to assess the rutting potential, moisture susceptibility, and dynamic modulus. After evaluating the moisture damage using the TSR, it was discovered that every blend generated TSR values that were lower than the 80% failing criteria. The TSR index for the WMA containing Sasobit is greater than the TSR value of Advera or Evotherm. The results for the dynamic modulus were found to be very similar for all the mixtures. The efficacy of WMA generated with both kinds of additions (Aspha-min® and Sasobit®) was investigated by Al-Jumaili and Al-Jameel [26].

The WMA samples were made at 120–125°C for compaction and 125–135°C for mixing, The researchers found that the WMA exhibited a decreased ITS in comparison to the HMA. Additionally, they determined that the WMA created with Sasobit achieved superior performance compared to the WMA generated with Aspha-min. Furthermore, one of the most popular methods for improving asphalt pavements’ resistance to moisture damage is the application of antistripping chemicals [27]. In this research, Zycotherm, WETMUL-950, GRIPPER L, Evonik, and TeraGrip are the five types of antistripping additives whose effects on asphalt pavements’ moisture resistance were assessed and contrasted with one another. The laboratory evaluation findings demonstrated that every ingredient utilized in this study enhanced the adhesion and cohesiveness qualities and raised the asphalt mixes’ resistance to moisture susceptibility. Another study by Amirkhani et al. [28], assessed how the use of fly ash, calcium carbonate, and Portland cement type II as filler affects the performance of WMAs manufactured with the Kaowax addition. The findings showed that the fly ash filler containing WMA samples exhibited good moisture susceptibility. Also, increased rutting resistance was the outcome of using cement filler in the WMA. Ameri et al. [29] examined how zeolite, a WMA addition, affects combinations of HMA and recycled asphalt (RA). The impact of these modifiers on the characteristics of binders and asphalt mixes was investigated using a variety of tests, including rotating viscosity, dynamic creep, resilient modulus, indirect tensile fatigue, and moisture susceptibility (TSR and RMR). The results show that adding zeolite and CR enhanced the mechanical characteristics. Furthermore, zeolite improved the long-term performance and ability of HMA and RA mixes, but the addition of CR to mixtures not having zeolite lowered the TSR, RMR, and workability of the mixtures. The outcomes of the cost-effective study also showed that when zeolite and CR are used properly, not only is the energy consumption reduced, but so is the cost of manufacturing the modified asphalt mixture.

On the other hand, many different countries have made it a priority in recent decades to move toward ecologically sustainable economic development. Reusing materials from construction is an additional technique to help the environment. Recycling aggregates to replace natural aggregates is a common practice in pavement construction [30]. In this way, it is feasible to protect natural resources and mitigate the effects of resource exploitation, leading to financial and energy savings as well as a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions [31,32,33].

The benefits of RAP for the environment and economy have led to a fast growth in its use in asphalt mixtures [34]. The presence of a binder in RAP decreases the quantity of new binder required for the production of asphalt mixtures. Moreover, the aggregates included in the RAP are utilized again to reduce the original expenses of construction and save natural resources [34,35]. This way of thinking applies to the utilization of reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP). Indeed, the utilization of reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) in asphalt mixture can yield favorable mechanical characteristics when employed appropriately [36,37].

The performance of asphalt mixes was examined by Zhao et al. [38] concerning the kind of WMA technology (foaming process and Evotherm) and the RAP concentration (0–40%). Regardless of the WMA technology employed, the results of the WMA study indicated that mixtures with greater RAP percentages exhibited better fatigue performance compared to both high and low RAP content in HMA. Nevertheless, WMA that has been mixed with larger proportions of Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement (RAP) exhibited reduced susceptibility to moisture and rutting in comparison to HMA with a greater proportion of RAP, but superior to WMA with a reduced RAP percentage. As to Schreck’s research [39], utilizing RAP at rates ranging from 10 to 40% enables cost reductions of 9 and 36% in the production, respectively.

Furthermore, according to Vidal et al. [40], RAP in HMA and WMA (with synthetic zeolite) decreases the ecological effects related to the asphalt mixture’s life cycle analysis. Although the use of RAP in asphalt mixes has presented several difficulties, the enhanced adhesion between the aggregate and binder for RAP might potentially mitigate the risk of damage caused by the presence of moisture caused by foaming WMA [41,42,43]. In 2020, Goli and Latifi [44] conducted an investigation on how moisture impacts the performance of mixtures by experimental methods such as resilient modulus, ITS, semi-circular bending, and dynamic creep tests. In general, the findings showed that even with water-loving and moisture-sensitive aggregates as well as aged binder, the WMA mixes including RAP performed suitably in terms of moisture resistance. As a result, this type of mixture might be advised for areas where there is a risk of moisture damage, environmental issues, and limited natural resources. Another study carried out by Valdes-Vidal et al. [45] conducted a testing investigation to analyze the physical properties of WMA mixes made using zeolite from Chile and varying quantities of reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) for eco-friendly pavement development. The findings indicated that WMA mixes including zeolite could be produced at a certain temperature of 20°C lower than the standard HMA [46], while still meeting the design requirements. An investigation conducted by Joni and Alkhafaji [47] examined the utilization of WMA-RAP and its effects on the efficiency of the asphalt mix. The study involved adding four different percentages of RAP (0, 20, 30, and 40%) to both HMA and WMA that contained 4% Sasobit. There was a little reduction in the ability of both HMA and WMA incorporating RAP to resist moisture compared to control mixtures of Asphalt. This was indicated by a fall in the TSR. However, the TSR values remain much higher than the minimum requirement of 80%. Another research [48] assessed the influence of including Sasobit on the susceptibility of mixtures to permanent distortion and moisture. The results show that the rut depth of the WMA, which underwent testing in the Hamburg wheel tracking device, exhibited a reduction in comparison to the control HMA, and the use of Sasobit resulted in a drop in moisture resistance compared to traditional HMA, as seen by a reduction in TSR. However, the moisture resistance remained over the lowest limit of 80%.

In addition to this, RA mixes with high-performance characteristics may be created at a lower temperature utilizing natural zeolite for environmentally friendly pavement building. In 2021, Rahman et al. [49] assessed the foamed WMA with RAP’s laboratory performance, specifically its susceptibility to deterioration from rutting and moisture, and compared with that of HMA with an equivalent quantity of RAP. Due to the use of cyclic load settings, it is shown that MIST conditioning more accurately replicates moisture-induced damage and can capture the inclination of asphalt mixtures to moisture damage than the AASHTO T283 technique [50]. Due to lower mixing and compaction temperatures, the foamed WMA showed increased susceptibility to rutting and moisture-induced damage compared to HMA. Increasing the RAP concentration was discovered to decrease rutting and susceptibility to moisture-induced damage in WMA. Numerous studies suggest that there is a problem with moisture sensitivity in warm mixes, The potential for damage caused by moisture in warmed blends has a clear relationship to their manufacturing process. A study by Kadhim et al. [6] examined and evaluated organic additive techniques. Based on the results, the majority of warm combinations met the minimal requirement for TSR set by the AASHTO (80%). However, certain mixtures did not meet this criterion, suggesting that moisture resistance is an issue in warm mixes. In the same approach, Asmael et al. [51] conducted a comprehensive investigation to evaluate the performance of WMA combinations using locally sourced components. According to the findings, the rut depth of surface mixtures increases in direct proportion to the concentration of WMA additives. Increasing the amount of Asphaltan A® results in a greater rut depth, whereas increasing the amount of Asphaltan B® leads to a reduction in rut depth. Both WMA and HMA combinations meet the acceptable standards for all mixes.WMA is created by employing the foaming technique or reducing viscosity additions in the binder to improve its rheological characteristics. A study with two rates of Aspha- mean (0.3 and 0.5%) was used [52]. The outcomes point out that the WMA exhibits significant resistance to rutting, comparable to that of the HMA mix. For organic additive techniques [53], the research conducted has shown that the inclusion of organic additives has a beneficial effect on the performance of warmed blends, namely, in terms of enhancing their fatigue resistance.

In the field of asphalt pavement, the demand for ecologically friendly roadway development and building is of utmost importance. The study by Ugla and Ismael [54] examined the impact of using alumina waste, namely, secondary aluminum dross (SAD), with asphalt-compressed samples that include recycled concrete aggregate (RCA) to be the coarse aggregate. Based on the results, by substituting 20% of the traditional filler with SAD in the blend that includes RCA at various proportions, the criteria for TSR and IRS are met. Another research [55] investigated the impact of various fillers, such as coconut peat and bagasse, on the efficiency of asphalt mixtures and their susceptibility to moisture damage. The results indicated a positive correlation between Rigden voids and pore size, as well as a negative correlation between Rigden voids and surface area, The moisture damage testing revealed that all mixes, including both dense and porous ones, exhibited good ability to resist damage caused by moisture.

The moisture sensitivity in warm mixes is an issue and therefore needs to be monitored and quantified. In this research, before adopting WMA technology, it is necessary to investigate the feasibility of using locally accessible materials for this technology. Therefore, locally reclaimed asphalt taken from one of the affected streets will be used and the effect of moisture on WMA will be evaluated using different proportions of this reclaimed asphalt. In addition, three types of mineral filler materials, which are available locally will be used.

2 Materials

A warm asphalt mixture was created using local aggregates and asphalt as the primary components of the pavement. The sections that follow describe the necessary attributes.

2.1 Asphalt binder

The present research utilized bitumen with a penetration grade of 40/50 that comes from the AL Daurah Refinery located in Baghdad City as the asphalt binder. The physical properties of asphalt binder in this study are given in Table 1.

Physical characteristics of asphalt binder

| Property | ASTM designation | Test result | SCRB specification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Penetration | D-5 | 46 | 40–50 |

| Ductility at 25°C | D-113 | 140 | >100 |

| Flash point | D-92 | 323 | Min. 232 |

| Softening point | D-36 | 52 | — |

| Viscosity @ 135°C | D-4402 | 612 | Min. 400 |

| Viscosity @ 165°C | D-4402 | 155 | — |

| Specific gravity | D-70 | 1.04 | — |

2.2 Aggregates

The source of the aggregate is the Al-Nebaee quarry, which is located north of Baghdad. The physical properties of aggregate are shown in Table 2. Both fine and coarse particles are components of aggregate. The chosen aggregate gradation is installed by the SCRB/R9 Specifications of the Iraqi Standard [56].

Physical properties of aggregate

| Property | ASTM designation | Coarse aggregate | Fine aggregate | SCRB specification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk specific gravity | C127, C128 | 2.569 | 2.615 | — |

| Apparent specific gravity | C127, C128 | 2.627 | 2.628 | — |

| Percent water absorption | C127, C128 | 0.94 | 0.92 | — |

| Angularity | D5821 | 95% | — | Min. 90% |

| Toughness | C535 | 20.2% | — | Max. 30% |

| Soundness | C88 | 3.9% | — | Max. 12% |

2.3 Mineral filling

Limestone dust, Portland cement, and hydrated lime, local Iraqi materials, are the three forms of filler that were added to the mixture to create asphalt concrete mixes. Table 3 lists the physical characteristics of these fillers.

Physical properties of filler

| Type of filler | Specific gravity | Surface area (m2/kg) | % Passing sieve No. 200 (0.075) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Portland cement | 3.14 | 290 | 98 |

| Limestone | 2.84 | 247 | 95 |

| Hydrated lime | 2.43 | 395 | 99 |

2.4 Aspha-min

The utilization of Aspha-min powder served as an addition to the manufacturing process of WMA. It is finely powdered sodium aluminosilicate that has been hydrothermally crystallized. Aspha-min, which has a water content of roughly 21% by weight, was included in the mixture at a concentration of 0.3% by weight. The physical properties of the Aspha-min are shown in Table 4, and Figure 1 illustrates this material.

Physical properties of additive (Aspha-min)

| Property | Result |

|---|---|

| Color | White |

| Specific gravity | 2.03 |

| Bulk density | 568 kg/m3 |

| Solubility in water | Insoluble |

| pH value | 11.6 |

| Odor | Odorless |

Aspha-min.

2.5 RAP

The RAP employed in the mixtures in this investigation was sourced via surface milling of Al-Shaab Stadium – Intersection in Baghdad – Iraq, also it was examined to ascertain the proportion of asphalt binder material by the ASTM D6307 – 10 standard. “Asphalt content by Ignition Furnace,” illustrates the RAP’s mean asphalt concentration of 4.79%. A test of this RAP’s particle size distribution was conducted as shown in Table 5. Figure 2 illustrates this material.

Gradation of RAP

| Sieve size | Iraqi specification (SCRB R9, 2003) surface layer type IIIA (% passing) | RAP specification | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard sieves (mm) | English sieves | Min. | Max. | Passing % |

| 19 | 3/4″ | — | 100 | 100 |

| 12.5 | 1/2″ | 90 | 100 | 97 |

| 9.5 | 3/8″ | 76 | 90 | 91 |

| 4.75 | #4 | 44 | 74 | 65 |

| 2.36 | #8 | 28 | 58 | 46 |

| 0.3 | #50 | 5 | 21 | 25 |

| 0.075 | #200 | 4 | 10 | 8.2 |

RAP material.

3 Production of mixtures

Marshall’s mix design process was the mix design technique used in this study to produce both warm and hot mixes. There are three different kinds of asphalt mixtures: warm mixes, hot mixes, and warm mixes with RAP. Asphalt cement, fine and coarse aggregates, three kinds of mineral fillers, a warm additive (Aspha-min), and a waste additive (RAP) make these mixtures. The zeolite was utilized (0.3 % of the total weight of the mixture) to produce the WMA. The aggregate is graded using wearing layer aggregate grade, which has a nominal maximum aggregate sieve size of 12.5 mm.

3.1 Preparation of specimens without RAP

Marshall specimen dimensions were used to create cylindrical samples for HMA and WMA specimens, which are 101.3 mm (diameter) × 63.5 mm (height), The samples were compacted using the Marshall compaction apparatus. According to ASTM D2493, the viscosity of the asphalt binder was measured at 135 and 165°C using the Equiviscous technique to determine the temperature ranges for mixing and compacting HMA samples. The asphalt binder’s mixing and compacting temperature for viscosities ranges 0.17 ± 0.02 Pa s and 0.28 ± 0.03 Pa s is 155 and 145°C, respectively.

In this study, homogeneity was maintained by compacting a mixture of WMA at 120°C after blending at 135°C. These temperatures were selected based on the literature, professional opinions, and suitable recommendations from the manufacturers of WMA technologies [57,58,59,60,61,62,63]. This procedure adheres to the WMA design methodology described in NCHRP Report 714 [52,64]. The bitumen becomes less viscous as a result of this temperature reduction. Following the process of crystallization, the bitumen transforms increased rigidity, resulting in enhanced resistance of the asphalt to deformation.

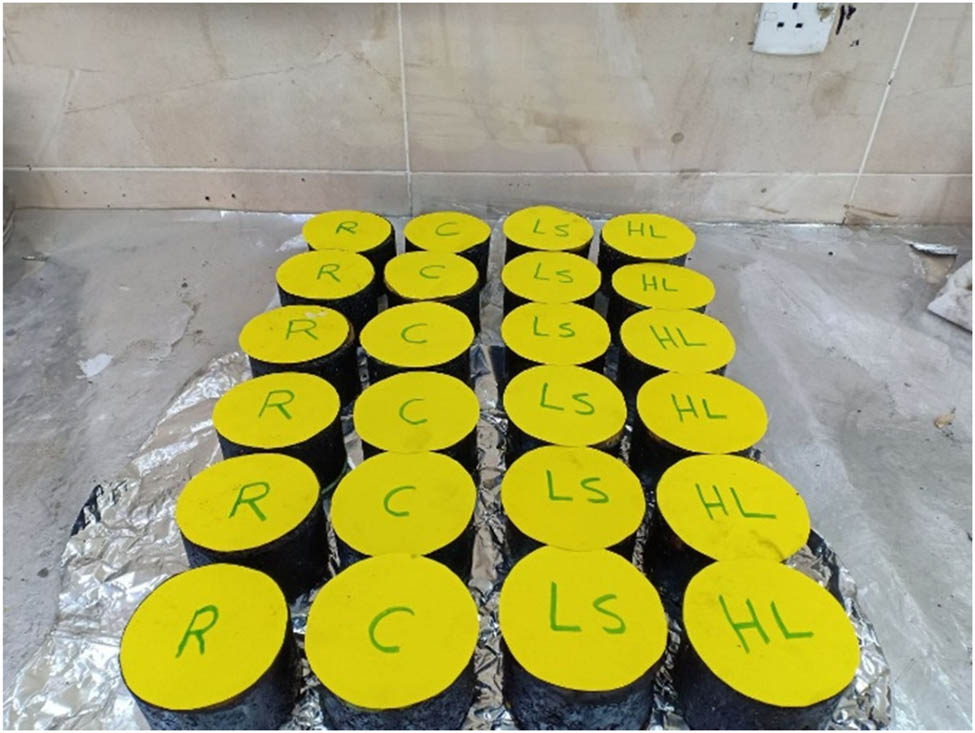

The volumetric characteristics of the WMA mixes are used to calculate the optimum contents of asphalt binder. This will decrease the impact of aging and boost the effectiveness of the warm mix components [58,65,66]. Figure 3 presents the prepared samples without RAP.

WMA samples prepared without RAP.

3.2 WMA with RAP

RAP is utilized as a proportion of the aggregate. The content of the asphalt binder and the crushed RAP aggregates in the recycled mixture must be ascertained. The proportions of the amount of RAP in the blends were 10, 20, and 30% of the mix’s whole weight (for this mixture, the overall amount of asphalt was maintained steady). The Marshall mix design approach was utilized in the laboratory to produce and compress all of the WMA mixes. Figure 4 presents the prepared samples with RAP.

Samples prepared with RAP.

3.2.1 Moisture susceptibility test

The method used to assess WMA and HMA samples’ sensitivity to moisture is ASTM D 4867 [67]. A range of 6–8% air void level was achieved by compacting six specimens of each mix type using the Marshall compaction technique. Three specimens from one subset of the specimens (the unconditioned specimens) were evaluated using an indirect tension test at a temperature of 25°C. When the other group (conditioned specimens) was evaluated, it was initially exposed to a single cycle of freezing and thawing (16 h at −18 ± 2°C and another 24 h at 60 ± 1°C). By loading the specimen along its diameter, the indirect tension test records the applied load (as shown in Figure 5). Below is the calculation of the test parameters:

where P is the applied load, h is the height of specimen (thickness), and D is the diameter of specimen.

Indirect tension test.

To assess the moisture susceptibility of all mixes, the TSR, which is the ratio of the ITS of a wet specimen to the ITS of a dry specimen, was determined. Equation (2) was utilized to get the TSR value for every mixture. According to ASTM D4867M 09, adequate resistance to moisture damage is often defined as having a TSR value higher than or equal to 80%. Figures 6 and 7 show some of the samples prepared and tested.

where TSR is the tensile strength ratio, %, C.ITS is the average tensile strength of the wet condition, kPa (conditioned case), and UC.ITS is the average tensile strength of the dry condition, kPa (unconditioned case).

Some samples at 25°C.

Some samples test.

4 Results and discussion

The mixes were put to the test in both wet and dry environments. Asphalt mixes based on AASHTO T283 requirements were used for the TSR test.

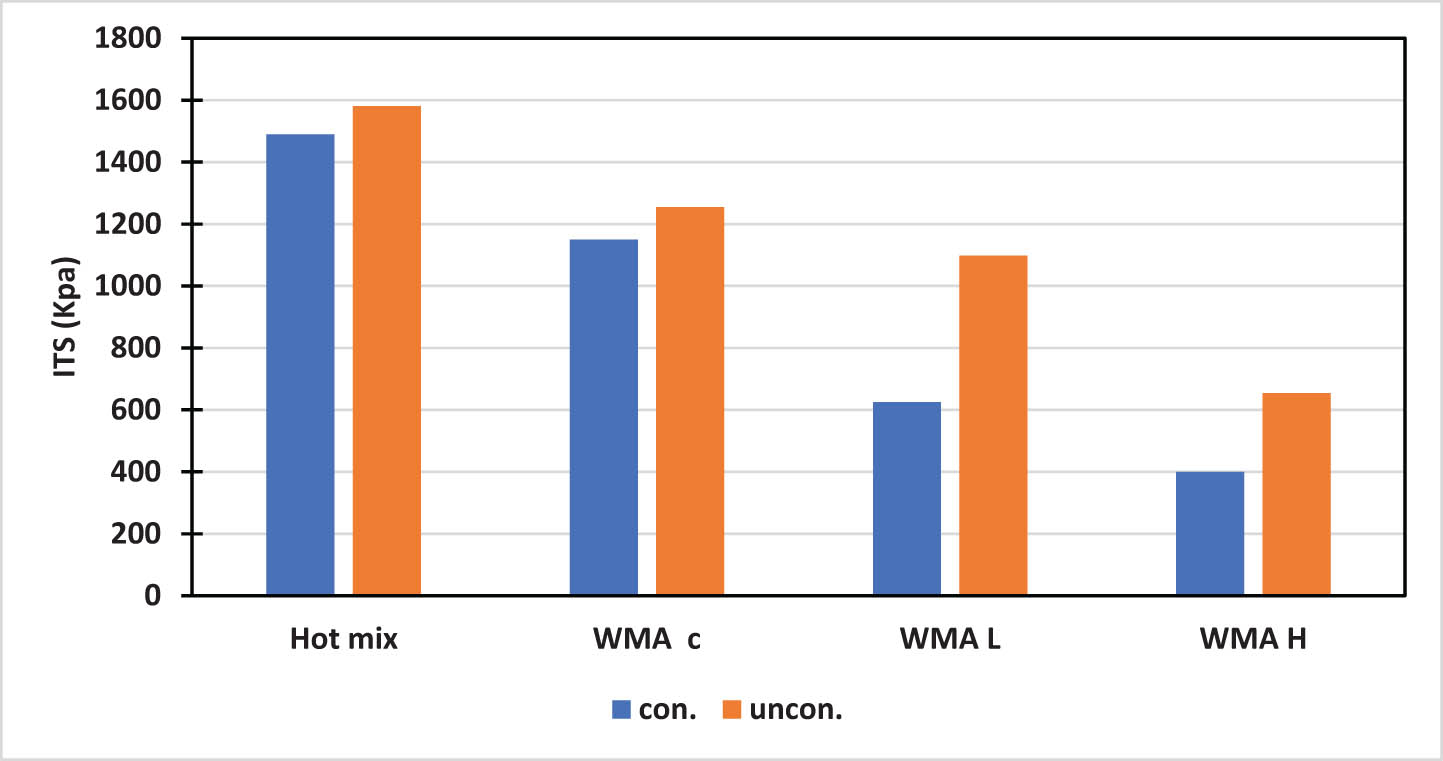

4.1 ITS

For both the conditioned (wet) sample and the unconditioned (dry) sample, the asphalt mixture’s ITS is shown in Figures 8 and 9, and Table 6. Based on these results, for WMA mixtures without including RAP in their mix, it is noticeable that WMA mixtures are more sensitive to moisture degradation than HMA mixes. For all samples, when comparing the WMA mixes with the HMA mixes, the average tensile strength (ITS) is lower. Higher value of ITS was found for samples containing cement as a filler but comparing with the HMA it is lower by about 22.8%, and 20.6% for two cases conditioned and unconditioned, respectively. While the samples with fillers limestone and hydrated lime showed lower values than the cement filler, as shown in Figure 8, which is approximately 58% conditioned, 30.5% unconditioned for limestone, and 73.1% conditioned, 58.6% unconditioned for hydrated lime, respectively lower than the HMA.

Moisture susceptibility values

| Mix type | ITS, kPa (psi) | TSR, % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cond. | Uncond. | ||

| HMA | 1,490 | 1,581 | 94 |

| WMA C 0% RAP | 1,150 | 1,255 | 91.6 |

| WMA C 10% RAP | 1,090 | 1,106 | 98.5 |

| WMA C 20% RAP | 1,361 | 1,493 | 91 |

| WMA C 30% RAP | 1,379 | 1,440 | 95.7 |

| WMA L 0% RAP | 625 | 1,098 | 57 |

| WMA L 10% RAP | 1,019 | 1,480 | 68.8 |

| WMA L 20% RAP | 1,242 | 1,480 | 84 |

| WMA L 30% RAP | 1,004 | 1,621 | 62 |

| WMA H 0% RAP | 400 | 654 | 61 |

| WMA H 10% RAP | 1,321 | 1,389 | 95 |

| WMA H 20% RAP | 1,479 | 1,510 | 99 |

| WMA H 30% RAP | 758 | 828 | 91.5 |

ITS results without RAP.

On the other hand, For the WMA mixtures, the average tensile strength (ITS) increased, when the amount of RAP in WMA mixes increased with different percentages (10, 20, and 30%) as shown in Figure 9. In both dry and wet situations, greater ITS values are achieved with three types of fillers for all mixtures comparable with mixes without RAP in their continents. The results show that the utilization of RAP could enhance the resistance to moisture damage. In addition, a higher value for TS was found for samples containing cement as a filler.

ITS results with RAP.

As presented in Figure 9, for 10% RAP, it is clear that mixes containing hydrated lime as a filler have a higher ITS value for the conditioned state than other fillers by 17.5 and 22.9% for cement and limestone filler respectively, whereas limestone filler shows a higher value of ITS for the unconditioned state than other fillers by 25.2 and 6.1% for cement and hydrated lime, respectively. For 20% of RAP, mixes containing hydrated lime as a filler have a higher ITS value for the conditioned state than other fillers by 8 and 16% for cement and limestone filler, and by 1.1 and 2% for cement and limestone filler for the unconditioned state, respectively. For 30% of RAP, mixes containing cement as a filler have a higher ITS value for the conditioned state than other fillers by 27 and 45% for limestone and hydrated lime filler, whereas for the unconditioned state, limestone filler shows a higher value than other fillers by 11.2 and 49% for cement and hydrated lime, respectively.

4.2 TSR

The susceptibility of the mixes to moisture was calculated using the TSR. A minimum requirement of 80% for the indirect TSR is recommended to distinguish between moisture-resistant and moisture-susceptible combinations (ASTM D4867M-09, 2014) and (AASHTO, T283 - 07, 2007). Figure 10 exhibits the TSR for control hot mix, and WMA mixes with and without RAP.

TSR results.

As presented in the figure, for mixes without RAP, the maximum percentage of TSR is (94%) for the traditional HMA. For the WMA mixture (content 0.3% synthetic Zeolite with 0% RAP), the ratio decreased to 91.6% for the WMA mixture with cement as filler, it is about 2.5% lower than the HMA. However, it satisfied the required minimum value (80%) for TSR, and then the ratio dropped to 61%, and 57% for the WMA mixes that contain hydrated lime and limestone as a filler, respectively. All WMA mixes have TSR values that are lower than those of the traditional HMA mixture without adding the RAP material. This shows that the possibility of moisture damage was raised by the use of synthetic zeolite. Previous investigations [19,57,68] have also reported similar findings.

Because of the possibility of inadequate drying of aggregates caused by lower mixing and compaction temperatures, zeolite WMA mixes may be more susceptible to moisture degradation. Increased moisture sensitivity may be caused by the water that is trapped in the coated aggregate as a result.

As seen in Figure 10, the TSR values of the WMA mixtures with different percentages of RAP (0, 10, 20, and 30%) containing cement as a filler material, met the requirement of a minimum limit of 80% for indirect TSR. It can be concluded that 10% RAP is the optimum value for mixes having cement as a filler material, which has an ITS ratio of 98.5%.

For WMA mixtures that have hydrated lime as a filler, as can be seen in the figure, the TSR values with different percentages of RAP (10, 20, and 30%) met the requirement of a minimum limit of 80% for indirect TSR and the optimum value of the RAP is 20% with ITS ratio of 99%. The enhancement in moisture resistance can be attributed to the intricate surface textures of hydrated lime, which can result in a rise in the asphalt covering the aggregate. This, in turn, can impact the resistance of mixtures to stripping. Consequently, this indicates that the addition of RAP with hydrated lime as a filler in a mixture leads to increased resistance to moisture damage.

Mixtures that contain limestone as a filler show that only 20% RAP met the requirement of a minimum limit of 80% for an indirect TSR value of 84% as presented in Figure 10.

The increase in the amount of RAP needs a higher temperature to be mixed and avoid a weak bond between the aggregate and binder. This indicates that when the proportion of RAP increases, it might lead to a potential decrease in the TSR values and lower resistance to moisture damage.

5 Conclusion

Based on the work presented in this study, considering the constraints of the experiment, and the materials employed, the potential for damage caused by moisture on WMA was assessed and contrasted with that of reference HMA that had the same gradations and RAP content. The following points were concluded from this study:

The WMA mixtures are more sensitive to moisture degradation than the HMA and have a lower average TSR than the HMA mixtures.

The WMA mixture with cement filler (0% RAP) was the only filler type that met the moisture damage standard criterion of a minimum TSR of 80%. However, it is still 2.5% lower than the HMA.

Adding the RAP component to the WMA mixtures enhanced the average tensile strength (ITS) value. The ITS ratio for WMA mixtures having cement, hydrated lime, and limestone filler is 98.5, 99, and 84% respectively, for the optimum percent of RAP for each type of filler.

Higher ITS values are achieved in dry and wet cases using three types of filler for all mixes, comparable to blends without RAP in their compositions.

Utilizing RAP with WMA was shown to decrease the risk of damage caused by moisture. All WMA with 10, 20, and 30% RAP have passed the TSR min. requirement (80%) except 10 and 30% RAP for limestone filler. As a result, the impacts of the RAP and foamed WMA process may balance each other.

The utilization of RAP with hydrated lime as a filler in WMA improves the resistance to moisture damage.

The optimum RAP content for WMA mixtures for cement filler is 10%, and for hydrated lime, and limestone filler is 20%.

It is recommended to use other filler types to evaluate the moisture damage of the WMA and try to use polymers to enhance the resistivity of the WMA mixtures to moisture damage.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization: M.Y.F. and M.M.H.; methodology: M.M.H. and S.S.H.; software: Z.M.; validation: M.Y.F., M.M.H, S.S.H., and H.H.H.; formal analysis: Z.M.; investigation: Z.M.; resources: M.Y.F.; data curation: Z.M.; writing – original draft preparation: Z.M.; supervision: M.M.H. and S.S.H.; project administration: M.Y.F.; funding acquisition: H.H.H. and Z.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Most datasets generated and analyzed in this study are comprised in this submitted manuscript. The other datasets are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author with the attached information.

References

[1] Bonaquist RF. Mix design practices for warm mix asphalt. Vol. 691, Transportation Research Board. NCHRP report 691; 2011.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Kheradmand B, Muniandy R, Hua LT, Yunus RB, Solouki A. An overview of the emerging warm mix asphalt technology. Int J Pavement Eng. 2014;15(1):79–94.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Hilal MM, Fattah MY. A model for variation with time of flexible pavement temperature. Open Eng. 2022;12(1):176–83. 10.1515/eng2022-0012.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Teh SY, Hamzah MO. Asphalt mixture workability and effects of long-term conditioning methods on moisture damage susceptibility and performance of warm mix asphalt. Constr Build Mater. 2019;207:316–28.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Brown DC. Warm mix: the lights are green. Hot Mix Asph Technol. 2008;13:20–22, 25, 27, 30, 32.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Kadhim AJ, Fattah MY, Asmael NM. Evaluation of the moisture damage of warm asphalt mixtures. Innovat Inf Solut. 2020;5:54.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Albayati AH. Performance evaluation of plant-produced warm mix asphalt. J Eng. 2018;24(5):145–64.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Barthel W, Marchand JP, Devivere MV. Warm asphalt mixes by adding asynthetic zeolite. Eurovia; 2006, www.Aspha-Min.com. TRB, The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; 2017. p. 1241–9. http://worldcat.org/isbn/9080288446.Search in Google Scholar

[9] D’Angelo JA, Harm EE, Bartoszek JC, Baumgardner GL, Corrigan MR, Cowsert JE, et al. Warm mix asphalt: European practice. U.S. Department of Transportation; 2008, (No. FHWA-PL-08-007).Search in Google Scholar

[10] Kiggundu BN, Roberts FL. Stripping HMA mixture: State-of-the-art Crit Rev test methods, NCAT Report No. 88-02. Auburn, AL: National Center for Asphalt Technology; 1988.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Doyle JD, Howard IL. Rutting and moisture damage resistance of high reclaimed asphalt pavement warm mixed asphalt: loaded wheel tracking vs conventional methods. Road Mater Pavement Des. 2013;14(sup 2):148–72. 10.1080/14680629.2013.812841.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Hicks RG. Moisture damage in asphalt concrete (NCHRP Synthesis of Highway Practice, No. 175. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board; 1991.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Little D, Jones DR. Chemical and mechanical processes of moisture damage in hot-mix-asphalt pavements. Moisture sensitivity of asphalt pavements: A national seminar. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board; 2003.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Lottman RP. Predicting moisture-induced damage to asphaltic concrete field evaluation (NCHRP Report No. 246). Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board; 1982.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Lu Q. Investigation of conditions for moisture damage in asphalt concrete and appropriate laboratory test methods. PhD dissertation. Berkeley, CA: University of California; 2005.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Hurley GC, Prowell BD. Evaluation of Sasobit for use in warm mix asphalt (NCAT Report 05-06). Auburn, AL: National Center for Asphalt Technology; 2005.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Hurley GC, Prowell BD. Evaluation of Evotherm® for use in warm mix asphalt (NCAT Report 06-02). Auburn, AL: National Center for Asphalt Technology; 2006.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Kvasnak AN, West RC. Case study of warm-mix asphalt moisture susceptibility in Birm ingham, Alabama. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board 88th annual meeting; 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Prowell BD, Hurley GC. Warm-mix asphalt: Best practices, Quality Improvement Series 125. Lanham, MD: National Asphalt Pavement Association; 2007.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Wasiuddin N, Fogle C, Zaman M, O'Rear E. Effect of anti-strip additives on surface free energy characteristics of asphalt binders for moisture-induced damage potential. J Test Eval. 2007;35(1):36–44.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Goh SW, You Z. Evaluation of warm mix asphalt produced at various temperatures through dynamic modulus testing and four-point beam fatigue testing. Proceedings of the GeoHunan international conference– pavements and materials: Recent advances in design, testing, and construction. Vol. 212, HunanChina: Geotechnical Special Publication; 2011. p. 123–30.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Hurley G, Prowell B, Kvasnak A. Wisconsin field trial of warm mix asphalt technologies: Construction summary (NCAT Report 10-04). Auburn, AL: National Center for Asphalt Technology; 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Hurley GC, Prowell BD, 2005, Evaluation of Aspha-Min zeolite for use in warm mix asphalt, NCAT report, 5(04).Search in Google Scholar

[24] Bhusal S. A laboratory study of warm mix asphalt for moisture damage potential and performances issues. PhD thesis. Oklahoma: Oklahoma State University; 2008.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Zhang J. Effects of warm-mix asphalt additives on asphalt mixture characteristics and pavement performance. MSc thesis. USA: University of Nebraska-Lincoln; 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Al-Jumaili MA, Al-Jameel HA. Influence of selected additives on warm asphalt mixtures performance. Kufa J Eng. 2015;6(2):49–62.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Ameri M, Ziari H, Yousefi A, Behnood A. Moisture susceptibility of asphalt mixtures: Thermodynamic evaluation of the effects of antistripping additives. J Mater Civ Eng. 2021;33(2):04020457.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Amirkhani MJ, Fakhri M, Amirkhani A. Evaluating the use of different fillers and Kaowax additive in warm mix asphalt mixtures. Case Studies Construct Mater. 2023;19:e02489.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Ameri M, Abdipour SV, Yengejeh AR, Shahsavari M, Yousefi AA. Evaluation of rubberised asphalt mixture including natural Zeolite as a warm mix asphalt (WMA) additive. Int J Pavement Eng. 2023;24(2):2057977.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Sanchez-Alonso E, Castro-Fresno D, Vega-Zamanillo A, Rodriguez Hernandez J. Sustainable asphalt mixes: use of additives and recycled materials. Balt J Road Bridge Eng. 2011;6(4):249–57.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Horvath A. Life-Cycle Environmental and Economic Assessment of using Recycled Materials for Asphalt Pavements Technical report. California: University of California Transportation Center (UCTC); 2003.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Eckelman MJ, Chertow MR. Quantifying life cycle environmental benefits from the reuse of industrial materials in Pennsylvania. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43(7):2550–6.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Xiao F, Amirkhanian SN. Laboratory investigation of utilizing high percentage of RAP in rubberized asphalt mixture. Mater Struct. 2010;43:223–33.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Al-Qadi IL, Ozer H, Lambros J, El Khatib A, Singhvi P, Khan T, et al. Testing protocols to ensure performance of high asphalt binder replacement mixes using RAP and RAS, Illinois Center for Transportation. Illinois Department of Transportation Series No. 15-017; 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Ghabchi R. Laboratory characterization of recycled and warm mix asphalt for enhanced pavement applications. PhD Dissertation. Norman, OK: The University of Oklahoma; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Valdés G, Pérez-Jiménez F, Miró R, Martínez A, Botella R. Experimental study of recycled asphalt mixtures with high percentages. Constr Build Mater. 2011;25:1289–97.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Miró R, Valdés G, Martínez A, Segura P, Rodríguez C. Evaluation of high modulus mixture behaviour with high reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) percentages for sustainable road construction. Constr Build Mater. 2011;25:3854–62.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Zhao S, Huang B, Shu X, Woods M. Comparative evaluation of warm mix asphalt containing high percentages of reclaimed asphalt pavement. Constr Build Mater. 2013;44:92–100.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Schreck R. More RAP in HMA: Is it worth it? The 2007 Virginia RAP initiative. Hot Mix Asph Technol. 2007;12(4):10–3.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Vidal R, Moliner E, Martínez G, Rubio MC. Life cycle assessment of hot mix asphalt and zeolite-based warm mix asphalt with reclaimed asphalt pavement. Resour, Conserv Recycl. 2013;74:101–14.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Zhao S, Huang B, Shu X, Jia X, Woods M. Laboratory performance evaluation of warm-mix asphalt containing high percentages of reclaimed asphalt pavement. Transp Res Rec. 2012;2294(1):98–105.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Shu X, Huang B, Shrum ED, Jia X. Laboratory evaluation of moisture susceptibility of foamed warm mix asphalt containing high percentages of RAP. Constr Build Mater. 2012;35:125–30.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Hill B, Behnia B, Buttlar WG, Reis H. Evaluation of warm mix asphalt mixtures containing reclaimed asphalt pavement through mechanical performance tests and an acoustic emission approach. J Mater Civ Eng. 2013;25(12):1887–97.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Goli H, Latifi M. Evaluation of the effect of moisture on behavior of warm mix asphalt (WMA) mixtures containing recycled asphalt pavement (RAP). Constr Build Mater. 2020;247:118526.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Valdes-Vidal G, Calabi-Floody A, Sanchez-Alonso E. Performance evaluation of warm mix asphalt involving natural zeolite and reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) for sustainable pavement construction. Constr Build Mater. 2018;174:576–85.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Addahhan AJ, Asmael NM, Fattah MY. Effects of organic warm mix asphalt additives on marshall properties, 2nd international conference on sustainable engineering techniques (ICSET 2019). In IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering. Vol. 518, IOP Publishing; 2019. p. 022071. 10.1088/1757-899X/518/2/022071.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Joni HH, Alkhafaji AY. Laboratory comparative assessment of warm and hot mixes Asphalt containing reclaimed Asphalt pavement. Wasit J Eng Sci. 2020;8(2):14–24.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Joni HH, Alkhafaji AY. Laboratory assessment of performance of WMA containing Sasobit. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. Vol. 1058, No. 1, IOP Publishing; 2021. p. 012036.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Rahman MA, Ghabchi R, Zaman M, Ali SA. Rutting and moisture-induced damage potential of foamed warm mix asphalt (WMA) containing RAP. Vol. 6, Innovative Infrastructure Solutions; 2021. p. 1–11.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Abdulsahib I, Hilal MM, Fattah MY, Dulaimi A. Performance evaluation of grouted porous asphalt concrete. Open Eng. 2024;14:20220556. 10.1515/eng-2022-0556.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Asmael NM, Fattah MY, Kadhim AJ. Evaluate resistance of warm asphalt mixtures to rutting. IOP Conf Ser. 2020;745:012109. 10.1088/1757-899X/745/1/012109.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Hilal MM, Fattah MY. Evaluation of resilient modulus and rutting for warm asphalt mixtures: a local study in Iraq. Appl Sci. 2022;12:12841.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Asmael NM, Fattah MY, Kadhim AJ. Exploring the effect of warm additives on fatigue cracking of asphalt mixtures. J Appl Sci Eng. 2020;23(2):197–205. 10.6180/jase.202006_23(2).0003.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Ugla SK, Ismael MQ. Evaluating the moisture susceptibility of asphalt mixtures containing RCA and modified by Waste Alumina. Civ Eng J. 2023;9:250–62.Search in Google Scholar

[55] Wuttisombatjaroen J, Hemnithi N, Chaturabong P. Investigating the influence of Rigden void of fillers on the moisture damage of asphalt mixtures. Civ Eng J. 2023;9(12):3161–73.Search in Google Scholar

[56] SCRB/R9, 2003, General Specification for Roads and Bridges, Section R/9, Hot-Mix Asphalt Concrete Pavement, Revised Edition. State Corporation of Roads and Bridges, Ministry of Housing and Construction, Republic of Iraq.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Hurley GC, Prowell BD. Evaluation of potential processes for use in warm mix asphalt. J Assoc Asph Paving Technol. 2006;75:41–90.Search in Google Scholar

[58] Malladi H, Ayyala D, Tayebali AA, Khosla NP. Laboratory evaluation of warm mix asphalt mixtures for moisture and rutting susceptibility. J Mater Civil Eng. 2015;27:04014162.Search in Google Scholar

[59] Wasiuddin NM, Selvamohan S, Zaman MM, Guegan M. Comparative laboratory study of sasobit and aspha-min additives in warm-mix asphalt. Transp Res Rec J Transp Res Board. 1998;2007:82–8.Search in Google Scholar

[60] Damm K, Abraham J, Butz T, Hildebrand G, Riebsehl G. Asphalt flow improvers as intelligent fillers for hot asphalts – a new chapter in asphalt technology. J Appl Asph Bind Technol. 2002–2004;2:36–69.Search in Google Scholar

[61] Abbas AR, Ali AW. Mech Prop Warm Mix Asph Prepared Using Foamed Asph Binders, FHWA Rep No: FHWA/OH-2011/06. Columbus, OH, USA: Ohio Department of Transportation; 2011.Search in Google Scholar

[62] Mo L, Li X, Fang X, Huurman M, Wu S. Laboratory investigation of compaction characteristics and performance of warm mix asphalt containing chemical additives. Constr Build Mater. 2012;37:239–47.Search in Google Scholar

[63] Almusawi A, Sengoz B, Topal A. Investigation of mixing and compaction temperatures of modified hot asphalt and warm mix asphalt. period. Polytech Civ Eng. 2021;65:72–83.Search in Google Scholar

[64] Special Mixture Design Considerations and Methods for Warm-Mix Asphalt: A Supplement to NCHRP Report 673: A Manual for Design of Hot-Mix Asphalt with Commentary; NCHRP Report 714; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

[65] Topal A, Sengoz B, Kok BV, Yilmaz M, Aghazadeh Dokandari P, Oner J, et al. Evaluation of mixture characteristics of warm mix asphalt involving natural and synthetic zeolite additives. Constr Build Mater. 2014;57:38–44.Search in Google Scholar

[66] Sengoz B, Topal A, Gorkem C. Evaluation of natural zeolite as warm mix asphalt additive and its comparison with other warm mix additives. Constr Build Mater. 2013;43:242–52.Search in Google Scholar

[67] ASTM D4867M-09. (2014). Standard Test Method for Effect of Moisture on Asphalt Concrete Paving Mixtures. ASTM International, i(Reapproved 2014), 5.Search in Google Scholar

[68] Xiao F, Wenbin Zhao PE, Amirkhanian SN. Fatigue behavior of rubberized asphalt concrete mixtures containing warm asphalt additives. Constr Build Mater. 2009;23(10):3144–51.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Modification of polymers to synthesize thermo-salt-resistant stabilizers of drilling fluids

- Study of the electronic stopping power of proton in different materials according to the Bohr and Bethe theories

- AI-driven UAV system for autonomous vehicle tracking and license plate recognition

- Enhancement of the output power of a small horizontal axis wind turbine based on the optimization approach

- Design of a vertically stacked double Luneburg lens-based beam-scanning antenna at 60 GHz

- Synergistic effect of nano-silica, steel slag, and waste glass on the microstructure, electrical resistivity, and strength of ultra-high-performance concrete

- Expert evaluation of attachments (caps) for orthopaedic equipment dedicated to pedestrian road users

- Performance and rheological characteristics of hot mix asphalt modified with melamine nanopowder polymer

- Second-order design of GNSS networks with different constraints using particle swarm optimization and genetic algorithms

- Impact of including a slab effect into a 2D RC frame on the seismic fragility assessment: A comparative study

- Analytical and numerical analysis of heat transfer from radial extended surface

- Comprehensive investigation of corrosion resistance of magnesium–titanium, aluminum, and aluminum–vanadium alloys in dilute electrolytes under zero-applied potential conditions

- Performance analysis of a novel design of an engine piston for a single cylinder

- Modeling performance of different sustainable self-compacting concrete pavement types utilizing various sample geometries

- The behavior of minors and road safety – case study of Poland

- The role of universities in efforts to increase the added value of recycled bucket tooth products through product design methods

- Adopting activated carbons on the PET depolymerization for purifying r-TPA

- Urban transportation challenges: Analysis and the mitigation strategies for road accidents, noise pollution and environmental impacts

- Enhancing the wear resistance and coefficient of friction of composite marine journal bearings utilizing nano-WC particles

- Sustainable bio-nanocomposite from lignocellulose nanofibers and HDPE for knee biomechanics: A tribological and mechanical properties study

- Effects of staggered transverse zigzag baffles and Al2O3–Cu hybrid nanofluid flow in a channel on thermofluid flow characteristics

- Mathematical modelling of Darcy–Forchheimer MHD Williamson nanofluid flow above a stretching/shrinking surface with slip conditions

- Energy efficiency and length modification of stilling basins with variable Baffle and chute block designs: A case study of the Fewa hydroelectric project

- Renewable-integrated power conversion architecture for urban heavy rail systems using bidirectional VSC and MPPT-controlled PV arrays as an auxiliary power source

- Exploitation of landfill gas vs refuse-derived fuel with landfill gas for electrical power generation in Basrah City/South of Iraq

- Two-phase numerical simulations of motile microorganisms in a 3D non-Newtonian nanofluid flow induced by chemical processes

- Sustainable cocoon waste epoxy composite solutions: Novel approach based on the deformation model using finite element analysis to determine Poisson’s ratio

- Impact and abrasion behavior of roller compacted concrete reinforced with different types of fibers

- Architectural design and its impact on daylighting in Gayo highland traditional mosques

- Structural and functional enhancement of Ni–Ti–Cu shape memory alloys via combined powder metallurgy techniques

- Design of an operational matrix method based on Haar wavelets and evolutionary algorithm for time-fractional advection–diffusion equations

- Design and optimization of a modified straight-tapered Vivaldi antenna using ANN for GPR system

- Analysis of operations of the antiresonance vibration mill of a circular trajectory of chamber vibrations

- Functions of changes in the mechanical properties of reinforcing steel under corrosive conditions

- 10.1515/eng-2025-0153

- Review Articles

- A modified adhesion evaluation method between asphalt and aggregate based on a pull off test and image processing

- Architectural practice process and artificial intelligence – an evolving practice

- Enhanced RRT motion planning for autonomous vehicles: a review on safety testing applications

- Special Issue: 51st KKBN - Part II

- The influence of storing mineral wool on its thermal conductivity in an open space

- Use of nondestructive test methods to determine the thickness and compressive strength of unilaterally accessible concrete components of building

- Use of modeling, BIM technology, and virtual reality in nondestructive testing and inventory, using the example of the Trzonolinowiec

- Tunable terahertz metasurface based on a modified Jerusalem cross for thin dielectric film evaluation

- Integration of SEM and acoustic emission methods in non-destructive evaluation of fiber–cement boards exposed to high temperatures

- Non-destructive method of characterizing nitrided layers in the 42CrMo4 steel using the amplitude-frequency technique of eddy currents

- Evaluation of braze welded joints using the ultrasonic method

- Analysis of the potential use of the passive magnetic method for detecting defects in welded joints made of X2CrNiMo17-12-2 steel

- Analysis of the possibility of applying a residual magnetic field for lack of fusion detection in welded joints of S235JR steel

- Eddy current methodology in the non-direct measurement of martensite during plastic deformation of SS316L

- Methodology for diagnosing hydraulic oil in production machines with the additional use of microfiltration

- Special Issue: IETAS 2024 - Part II

- Enhancing communication with elderly and stroke patients based on sign-gesture translation via audio-visual avatars

- Optimizing wireless charging for electric vehicles via a novel coil design and artificial intelligence techniques

- Evaluation of moisture damage for warm mix asphalt (WMA) containing reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP)

- Comparative CFD case study on forced convection: Analysis of constant vs variable air properties in channel flow

- Evaluating sustainable indicators for urban street network: Al-Najaf network as a case study

- Node failure in self-organized sensor networks

- Comprehensive assessment of side friction impacts on urban traffic flow: A case study of Hilla City, Iraq

- Design a system to transfer alternating electric current using six channels of laser as an embedding and transmitting source

- Security and surveillance application in 3D modeling of a smart city: Kirkuk city as a case study

- Modified biochar derived from sewage sludge for purification of lead-contaminated water

- The future of space colonisation: Architectural considerations

- Design of a Tri-band Reconfigurable Antenna Using Metamaterials for IoT Applications

- Special Issue: AESMT-7 - Part II

- Experimental study on behavior of hybrid columns by using SIFCON under eccentric load

- Special Issue: ICESTA-2024 and ICCEEAS-2024

- A selective recovery of zinc and manganese from the spent primary battery black mass as zinc hydroxide and manganese carbonate

- Special Issue: REMO 2025 and BUDIN 2025

- Predictive modeling coupled with wireless sensor networks for sustainable marine ecosystem management using real-time remote monitoring of water quality

- Management strategies for refurbishment projects: A case study of an industrial heritage building

- Structural evaluation of historical masonry walls utilizing non-destructive techniques – Comprehensive analysis

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Modification of polymers to synthesize thermo-salt-resistant stabilizers of drilling fluids

- Study of the electronic stopping power of proton in different materials according to the Bohr and Bethe theories

- AI-driven UAV system for autonomous vehicle tracking and license plate recognition

- Enhancement of the output power of a small horizontal axis wind turbine based on the optimization approach

- Design of a vertically stacked double Luneburg lens-based beam-scanning antenna at 60 GHz

- Synergistic effect of nano-silica, steel slag, and waste glass on the microstructure, electrical resistivity, and strength of ultra-high-performance concrete

- Expert evaluation of attachments (caps) for orthopaedic equipment dedicated to pedestrian road users

- Performance and rheological characteristics of hot mix asphalt modified with melamine nanopowder polymer

- Second-order design of GNSS networks with different constraints using particle swarm optimization and genetic algorithms

- Impact of including a slab effect into a 2D RC frame on the seismic fragility assessment: A comparative study

- Analytical and numerical analysis of heat transfer from radial extended surface

- Comprehensive investigation of corrosion resistance of magnesium–titanium, aluminum, and aluminum–vanadium alloys in dilute electrolytes under zero-applied potential conditions

- Performance analysis of a novel design of an engine piston for a single cylinder

- Modeling performance of different sustainable self-compacting concrete pavement types utilizing various sample geometries

- The behavior of minors and road safety – case study of Poland

- The role of universities in efforts to increase the added value of recycled bucket tooth products through product design methods

- Adopting activated carbons on the PET depolymerization for purifying r-TPA

- Urban transportation challenges: Analysis and the mitigation strategies for road accidents, noise pollution and environmental impacts

- Enhancing the wear resistance and coefficient of friction of composite marine journal bearings utilizing nano-WC particles

- Sustainable bio-nanocomposite from lignocellulose nanofibers and HDPE for knee biomechanics: A tribological and mechanical properties study

- Effects of staggered transverse zigzag baffles and Al2O3–Cu hybrid nanofluid flow in a channel on thermofluid flow characteristics

- Mathematical modelling of Darcy–Forchheimer MHD Williamson nanofluid flow above a stretching/shrinking surface with slip conditions

- Energy efficiency and length modification of stilling basins with variable Baffle and chute block designs: A case study of the Fewa hydroelectric project

- Renewable-integrated power conversion architecture for urban heavy rail systems using bidirectional VSC and MPPT-controlled PV arrays as an auxiliary power source

- Exploitation of landfill gas vs refuse-derived fuel with landfill gas for electrical power generation in Basrah City/South of Iraq

- Two-phase numerical simulations of motile microorganisms in a 3D non-Newtonian nanofluid flow induced by chemical processes

- Sustainable cocoon waste epoxy composite solutions: Novel approach based on the deformation model using finite element analysis to determine Poisson’s ratio

- Impact and abrasion behavior of roller compacted concrete reinforced with different types of fibers

- Architectural design and its impact on daylighting in Gayo highland traditional mosques

- Structural and functional enhancement of Ni–Ti–Cu shape memory alloys via combined powder metallurgy techniques

- Design of an operational matrix method based on Haar wavelets and evolutionary algorithm for time-fractional advection–diffusion equations

- Design and optimization of a modified straight-tapered Vivaldi antenna using ANN for GPR system

- Analysis of operations of the antiresonance vibration mill of a circular trajectory of chamber vibrations

- Functions of changes in the mechanical properties of reinforcing steel under corrosive conditions

- 10.1515/eng-2025-0153

- Review Articles

- A modified adhesion evaluation method between asphalt and aggregate based on a pull off test and image processing

- Architectural practice process and artificial intelligence – an evolving practice

- Enhanced RRT motion planning for autonomous vehicles: a review on safety testing applications

- Special Issue: 51st KKBN - Part II

- The influence of storing mineral wool on its thermal conductivity in an open space

- Use of nondestructive test methods to determine the thickness and compressive strength of unilaterally accessible concrete components of building

- Use of modeling, BIM technology, and virtual reality in nondestructive testing and inventory, using the example of the Trzonolinowiec

- Tunable terahertz metasurface based on a modified Jerusalem cross for thin dielectric film evaluation

- Integration of SEM and acoustic emission methods in non-destructive evaluation of fiber–cement boards exposed to high temperatures

- Non-destructive method of characterizing nitrided layers in the 42CrMo4 steel using the amplitude-frequency technique of eddy currents

- Evaluation of braze welded joints using the ultrasonic method

- Analysis of the potential use of the passive magnetic method for detecting defects in welded joints made of X2CrNiMo17-12-2 steel

- Analysis of the possibility of applying a residual magnetic field for lack of fusion detection in welded joints of S235JR steel

- Eddy current methodology in the non-direct measurement of martensite during plastic deformation of SS316L

- Methodology for diagnosing hydraulic oil in production machines with the additional use of microfiltration

- Special Issue: IETAS 2024 - Part II

- Enhancing communication with elderly and stroke patients based on sign-gesture translation via audio-visual avatars

- Optimizing wireless charging for electric vehicles via a novel coil design and artificial intelligence techniques

- Evaluation of moisture damage for warm mix asphalt (WMA) containing reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP)

- Comparative CFD case study on forced convection: Analysis of constant vs variable air properties in channel flow

- Evaluating sustainable indicators for urban street network: Al-Najaf network as a case study

- Node failure in self-organized sensor networks

- Comprehensive assessment of side friction impacts on urban traffic flow: A case study of Hilla City, Iraq

- Design a system to transfer alternating electric current using six channels of laser as an embedding and transmitting source

- Security and surveillance application in 3D modeling of a smart city: Kirkuk city as a case study

- Modified biochar derived from sewage sludge for purification of lead-contaminated water

- The future of space colonisation: Architectural considerations

- Design of a Tri-band Reconfigurable Antenna Using Metamaterials for IoT Applications

- Special Issue: AESMT-7 - Part II

- Experimental study on behavior of hybrid columns by using SIFCON under eccentric load

- Special Issue: ICESTA-2024 and ICCEEAS-2024

- A selective recovery of zinc and manganese from the spent primary battery black mass as zinc hydroxide and manganese carbonate

- Special Issue: REMO 2025 and BUDIN 2025

- Predictive modeling coupled with wireless sensor networks for sustainable marine ecosystem management using real-time remote monitoring of water quality

- Management strategies for refurbishment projects: A case study of an industrial heritage building

- Structural evaluation of historical masonry walls utilizing non-destructive techniques – Comprehensive analysis