Abstract

This research focuses on studying the impact and abrasion behavior of roller compacted concrete (RCC) reinforced with different types of fibers to enhance their mechanical properties. The problem statement revolves around investigating the effects of adding polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and macro polypropylene (MPP) fiber to concrete mixtures, analyzing how these fibers influence the compressive strength, abrasion resistance, and impact resistance of the RCC. Specifically, this study aims to determine the optimal fiber content that can improve impact and abrasion resistance without compromising compressive strength in RCC. The results show that adding different amounts of PET fiber leads to a decrease in the compressive strength compared to the reference mixture. The addition of 1–3 kg/m3 of MPP increases the compressive strength by 16.5–29.8%, while 5 kg/m3 of MPP decreases the compressive strength by 6.8% compared to the reference mixture. The inclusion of PET and MPP fibers in various ratios enhances the impact resistance of all mixtures compared to the reference mixture. However, the addition of PET fibers and 5 kg/m3 of MPP decreases the abrasion resistance, while 1–3 kg/m3 of MPP increases the abrasion resistance by 13.3–24%.

1 Introduction

Given that concrete is the second most widely used material worldwide and a significant source of CO2 emission, there has been a growing focus on substituting natural aggregate with industrial or construction waste [1]. The annual consumption of plastics is rising sharply, driven by population growth, advancements in daily living standards, and significant developments in the food industry. Contributing factors include the low density of plastics, increased manufacturing capacity, durability, lightweight nature, and low production costs, all of which fuel the rapid expansion of plastic use each year [2]. In recent years, the use of recycled materials such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET) has been studied. Significantly, many types of water bottles and containers are made of this plastic. The production of this product is several million tons. Waste formed after the use of the products is aggressively recycled [3].

Roller compacted concrete (RCC) is a type of concrete known for its durability and cost-effectiveness, particularly in heavy-duty applications such as pavements and storage areas. Recent studies have explored the reinforcement of RCC with PET fibers and other materials to enhance its mechanical properties, including impact and abrasion resistance. The incorporation of PET fibers, derived from recycled plastic bottles, has shown promising results in improving the ductility and toughness of concrete. For instance, the addition of PET fibers in various proportions (0.25–0.5%) to M30 grade concrete significantly improved its compressive, split tensile, and flexural strengths, as well as its impact resistance [4]. Similarly, the use of PET fibers in recycled aggregate concrete increased the critical strain and reduced concrete damage under high strain rates, demonstrating enhanced toughness and reduced brittleness [5]. Additionally, the use of PET fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) for concrete confinement under impact loading has demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional carbon FRPs, owing to PET’s large rupture strain properties [6]. On the other hand, the development of green RCC using local materials and waste products such as silica fume, ground granulated blast furnace slag, crumb rubber, and recycled steel fibers has also been investigated. These materials have been found to improve the impact and abrasion resistance of RCC, making it more suitable for heavy-duty pavements [7]. Specifically, the inclusion of crumb rubber and recycled steel fibers significantly increased the impact energy and abrasion resistance, validating their use in RCC pavements [7]. Moreover, the mix design of RCC for high-volume traffic applications has been optimized to achieve better mechanical properties, including compressive and flexural strengths, as well as reduced shrinkage strains, making it suitable for state highways and other heavily loaded pavements [8].

Overall, the integration of PET fibers and other waste materials into RCC not only enhances its impact and abrasion resistance but also contributes to sustainability by recycling waste products, thereby offering a more durable and environmentally friendly solution for construction applications.

2 Contribution of this work to the current research community

2.1 Enhancing the mechanical properties of RCC

Impact resistance: This study demonstrates that the inclusion of PET and MPP fibers significantly enhances the impact resistance of RCC. This finding is crucial for applications where RCC is subjected to dynamic loadings, such as in airport runways and military facilities.

Abrasion resistance: This research shows that MPP fibers can improve abrasion resistance, making RCC more durable and suitable for high-wear environments. This is particularly relevant for infrastructure projects where surface wear is a critical concern.

2.2 Environmental benefits

Recycling solid waste: By incorporating PET fibers, which are derived from recycled materials, this study addresses the environmental issue of solid waste disposal. This contributes to sustainable construction practices by reducing the environmental footprint of concrete production.

Sustainable development: This research aligns with the broader goals of sustainable development in the construction industry by promoting the use of recycled materials and improving the longevity and durability of concrete structures.

2.3 Practical implications

Cost-effectiveness: The findings suggest that using fibers like PET and MPP can enhance the mechanical properties of RCC without significantly increasing the cost. This makes fiber-reinforced RCC a viable option for a wide range of construction projects.

Versatility in applications: The improved properties of fiber-reinforced RCC make it suitable for various applications, from large-scale infrastructure projects to smaller, more specialized constructions. This versatility can lead to broader adoption of fiber-reinforced concrete in the industry.

2.4 Contribution to existing knowledge

Comprehensive analysis: This study provides a detailed analysis of how different types and amounts of fibers affect the mechanical properties of RCC. This adds to the existing body of knowledge by offering specific data and insights that can be used for further research and development in the field.

Benchmarking: The results serve as a benchmark for future studies, helping researchers compare the effectiveness of various fiber types and compositions in enhancing concrete properties. This can guide future innovations and improvements in concrete technology.

2.5 Addressing research gaps

Impact and abrasion resistance: While many studies have focused on the compressive strength of fiber-reinforced concrete, this research provides valuable data on the impact and abrasion resistance, addressing a gap in the current literature.

Fiber types and ratios: The study explores the effects of different fiber types (PET and MPP) and their varying ratios, offering a nuanced understanding of how these variables influence the concrete properties. This can inform more targeted and effective use of fibers in concrete mixtures,

In summary, this work makes significant contributions to the current research community by enhancing the understanding of how fiber reinforcement can improve the mechanical properties of RCC, promoting sustainable construction practices, and providing practical insights for the industry. The study’s findings and methodologies can serve as a foundation for future research and development in the field of fiber-reinforced concrete.

Research significance: The importance of this study is that it determines the effects of adding different amounts and types of fibers in improving some mechanical properties of RCC, such as the impact resistance and abrasion resistance. On the other hand, improving the environment, benefiting from and disposing of solid waste, which requires a long time to decompose in the soil, is expensive, and requires greater human resources to dispose of this waste.

Methods used:

Impact test was conducted using a drop weight machine in accordance with the technique suggested by the ACI committee 544.

Abrasion resistance was measured using an apparatus according to the requirements of ASTM C 944, which determines abrasion resistance by measuring the amount of concrete abraded by a rotating cutter in a given time period.

The Ve Be apparatus was used to test all RCC samples in accordance with ASTM C1170, and a compression testing machine was utilized for the compressive test following BS: 1881: Part 116: 1983 standards.

3 Novelty of the present study compared to other studies

The present study offers several novel contributions to the field of RCC reinforced with different types of fibers. The key points that highlight its novelty compared to other studies are as follows.

3.1 Comprehensive analysis of fiber types

This study investigates the effects of two different types of fibers, PET and macro polypropylene (MPP) fiber, on the mechanical properties of RCC. This dual focus on both PET and MPP fibers is relatively unique, as many studies tend to focus on a single type of fiber.

3.2 Environmental impact

This research emphasizes the environmental benefits of using PET fibers, which are derived from recycled materials. This approach not only aims to improve the mechanical properties of RCC but also addresses the issue of solid waste disposal, which is a significant environmental concern.

3.3 Detailed mechanical property assessment

The study provides a detailed assessment of various mechanical properties, including the compressive strength, abrasion resistance, and impact resistance. This comprehensive evaluation helps in understanding the trade-offs and benefits associated with the addition of different fibers.

3.4 Quantitative improvements

This research quantifies the improvements in mechanical properties with specific percentages and amounts of fibers. For instance, the addition of 3% PET leads to a significant increase in impact resistance by 239.5%, while the addition of 3 kg/m³ of MPP results in a 29.8% increase in compressive strength and a 24% increase in abrasion resistance.

3.5 Validation with previous studies

The findings of this study are consistent with previous research, which helps in validating the results. For example, the decrease in compressive strength with the addition of PET fibers aligns with earlier studies, providing a robust foundation for the conclusions drawn.

3.6 Impact and abrasion resistance

The study specifically focuses on the impact and abrasion resistance of RCC, which are critical properties for structures subjected to extreme loads. The inclusion of fibers significantly enhances these properties, making the concrete more durable and resilient.

3.7 Practical implications

This research has practical implications for the construction industry, particularly in areas where RCC is used. The findings can guide the selection of fiber types and amounts to achieve the desired mechanical properties, thereby improving the performance and longevity of concrete structures.

In summary, the novelty of this study lies in its dual focus on PET and MPP fibers, its environmental considerations, comprehensive mechanical property assessment, and practical implications for the construction industry. These aspects collectively contribute to advancing the understanding and application of fiber-reinforced RCC.

Excremental work: The flow chart below provides a clear and structured overview of the steps taken in the study, from the initial literature review to the final acknowledgements. Each step is crucial in ensuring the study’s objectives are met and the results are reliable and applicable.

4 Materials

4.1 Cement

Ordinary Portland cement type 1 (OPC) was used. The physical and chemical properties are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Physical and mechanical properties of OPC

| Properties | Test results | Iraqi specification No. 5/2019 limits [9] |

|---|---|---|

| Specific surface area (Blain’s method), m²/kg | 263.6 | ≥230 |

| Soundness (the autoclave method), % | 0.14 | <0.8 |

| Setting time (Vicat’s method) | ||

| Initial setting, h:min | 1:13 | ≥45 min |

| Final setting, h:min | 3:15 | ≤10 h |

| Compressive strength | ||

| 3 days, N/mm² | 21 | ≥15 |

| 7 days, N/mm² | 29 | ≥23 |

Chemical compositions of the OPC used

| Oxide composition (% by weight) | Test results of the cement used | Limits of IQS: 5/2019 |

|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 21.31 | — |

| Al2O3 | 5.89 | — |

| Fe2O3 | 2.67 | — |

| CaO | 62.2 | — |

| MgO | 3.62 | ≤5% |

| SO3 | 2.6 | ≤2.80% (if C3A ≥ 5%) |

| Loss of ignition | 1.59 | ≤4% |

| Insoluble residue | 0.24 | ≤0.15% |

| Main component | ||

| C3S | 40.388 | — |

| C2S | 30.835 | — |

| C3A | 11.09 | — |

| C4AF | 8.12 | — |

4.2 Coarse aggregate

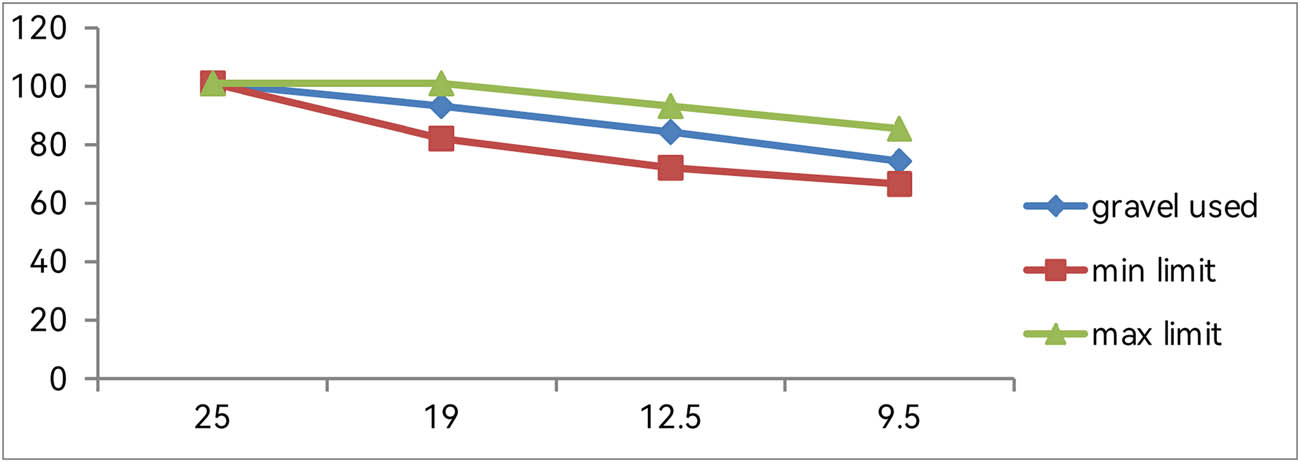

Coarse aggregate with a maximum aggregate size of 19 mm was used. The sieve analysis results are presented in Table 3 and Figure 1.

Sieve analysis of the used coarse aggregate

| Sieve size (mm) | Cumulative passing (%) | Limits of ACI 211.3R [10] |

|---|---|---|

| 25 | 100 | 100 |

| 19 | 93 | 82–100 |

| 12.5 | 84 | 72–93 |

| 9.5 | 74 | 66–85 |

Sieve analysis of the coarse aggregate.

4.3 Fine aggregate

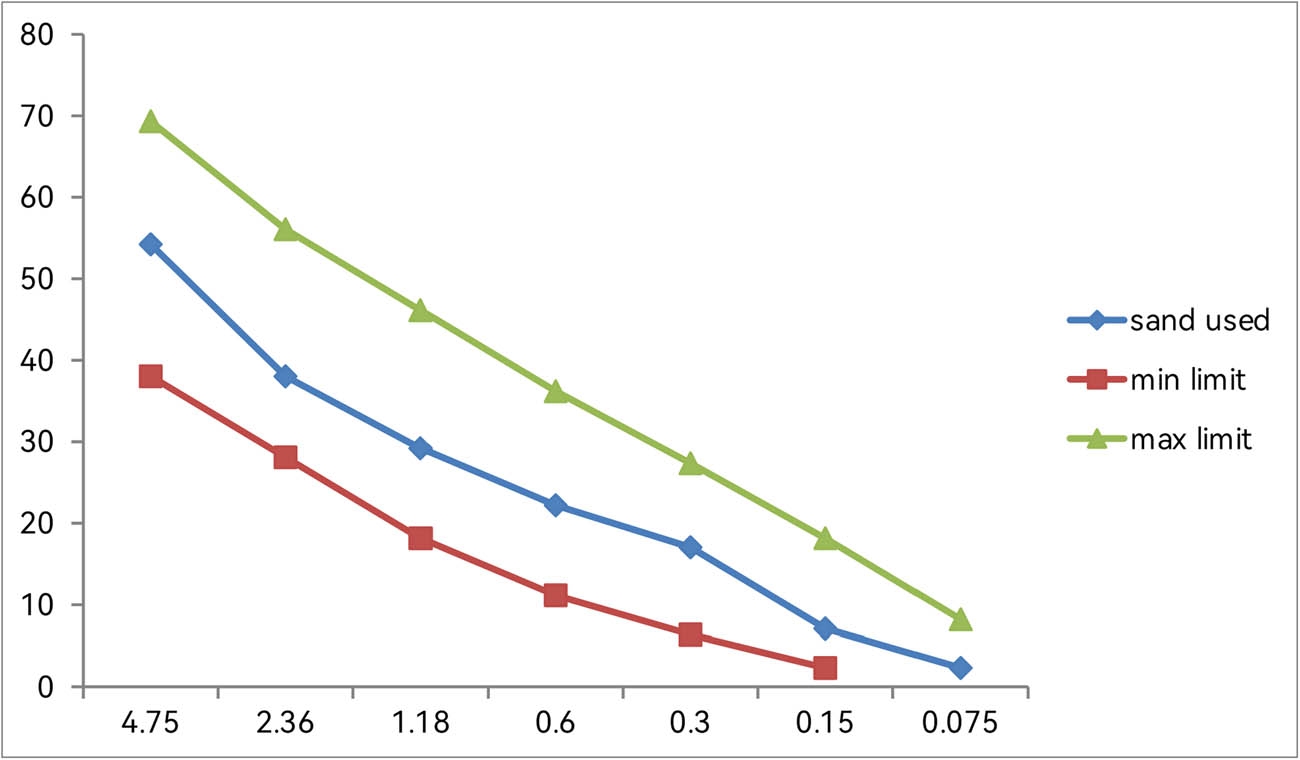

Fine natural sand was sourced from the Kanhash region, and the sieve analysis results for this sand are provided in Table 4 and Figure 2.

Sieve analysis of the used fine aggregate

| Sieve size (mm) | Cumulative passing (%) | Limits of ACI 211.3R |

|---|---|---|

| 4.75 | 54 | 51–69 |

| 2.36 | 38 | 38–56 |

| 1.18 | 29 | 28–46 |

| 0.6 | 22 | 18–36 |

| 0.3 | 17 | 11–27 |

| 0.15 | 7 | 6–18 |

| 0.075 | 2 | 2–8 |

Sieve analysis of the fine aggregate.

4.4 PET

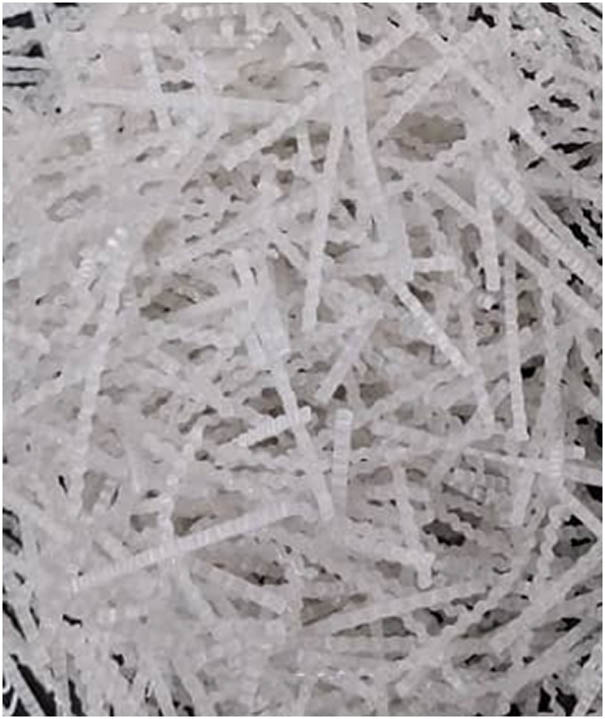

PET: The spent mineral water bottles are collected from cafeterias. The PET fibers are cut after removing the bottom and neck of the bottle; 2 mm wide and 50 mm long PET fibers were used. The cutting process was performed manually using special scissors. Figure 3 shows PET fibers obtained from mineral water bottles after the shredding process. The properties of the PET fibers used are shown in Table 5.

PET used.

Properties of used PET

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Density | 1.335 g cm−3 |

| Tensile strength (v = 5 mm min−1, 23°C) | 57 MPa |

| Water absorption | 0.0% |

4.5 Macro PP fiber

Macro PP fiber, a high-performance monofilament polypropylene macro fiber, is a synthetic material composed of 100% polypropylene fibers. It contains no reprocessed olefin materials and exhibits excellent alkali resistance, impermeability, and non-corrosive properties. The distinctive composition of macro PP fiber makes it a superior alternative to traditional reinforcement steel mesh, effectively reducing plastic shrinkage cracking and enhancing the durability and mechanical properties of cementitious mixes. The characteristics of the polypropylene fibers are illustrated in Table 6 and Figure 4.

Properties of MPP fibers

| Fiber properties | Quantity |

|---|---|

| Color | White |

| Shape | Monofilaments |

| Specific gravity | 0.95 ± 0.05 |

| Modulus of elasticity | 3.4–4.0 GPa |

| Tensile strength | ≥450 MPa |

| Chemical resistance | Very high |

| Electrical conductivity | Very low |

| Melting point | 160°C |

| Ignition point | 580°C |

| Chloride content | Nil |

| Sulfate content | Nil |

| Alkali content | Nil |

| Acid and alkali resistance | Strong |

| Dosage | Typical dosage is between 1.0 and 5.0 kg/m3 of concrete |

MPP fibers.

4.6 Water

All the concrete mixtures were prepared using tap water.

Preparation and casting of specimens: All the concrete mixtures were cast in the laboratory by using a drum mixer. Each batch was used to cast six cubes of (100 × 100 × 100) mm3 to perform the compressive strength, six cylinders of (150 × 63.5) mm2 to perform the impact resistance, and six cylinders of (150 × 75) mm2 to perform the abrasion resistance tests.

5 Designation of the RCC mixture (reference mixture)

5.1 Mixture proportion

The mixture proportions to produce 1 m3 of RCC are shown in Table 7, and the mixture proportions for all RCC reinforced with fibers are illustrated in Table 8.

Mix proportion of concrete constituents using ACI 211.3R

| Constituents | Water | Cement | Sand | Gravel |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg/m³) | 154 | 327 | 1,058 | 861 |

| Percentage | 0.47 | 1 | 3.23 | 2.63 |

Mixtures proportions for fiber-reinforced RCC

| Mixture | Water (kg/m³) | Cement (kg/m³) | Sand (kg/m³) | Gravel (kg/m³) | PET% of cement content | MPP (kg/m³) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 (reference) | 154 | 327 | 1,058 | 861 | — | — |

| C2 | 154 | 327 | 1,058 | 861 | 1 | — |

| C3 | 154 | 327 | 1,058 | 861 | 2 | — |

| C4 | 154 | 327 | 1,058 | 861 | 3 | — |

| C5 | 154 | 327 | 1,058 | 861 | — | 1 |

| C6 | 154 | 327 | 1,058 | 861 | — | 3 |

| C7 | 154 | 327 | 1,058 | 861 | — | 5 |

5.2 Testing machine

5.2.1 Ve Be apparatus

Figure 5 shows a Ve Be test apparatus used to test all RCC samples in accordance with ASTM C1170 [11].

Ve Be apparatus.

5.2.2 Comprehensive strength test

The compressive test was performed using a compression testing machine with a loading rate of 0.3 MPa/s and a capacity of 2,000 kN, as shown in Figure 6, in accordance with BS: 1881: Part 116: 1983 [12].

Compression testing machine.

5.2.3 Impact test (drop weight machine)

The apparatus used in measuring the impact resistance of FRC, with all accessories, was in accordance with the technique suggested by the ACI committee 544 [13]. Figures 7 and 8 show the details of the impact test apparatus.

Drop weight machine.

![Figure 8

Design details of the impact test apparatus [13].](/document/doi/10.1515/eng-2025-0107/asset/graphic/j_eng-2025-0107_fig_008.jpg)

Design details of the impact test apparatus [13].

5.2.4 Abrasion test apparatus

The apparatus, used in measuring the abrasion resistance, with all accessories, was in accordance with the requirements of ASTM C 944 [14]. This test determines the abrasion resistance by measuring the amount of concrete abraded from a surface by a rotating cutter in a given time period. Figures 9–11 show a photo of the apparatus designed according to ASTM C 944.

Abrasion test (rotating – cutter drill press) apparatus.

Design details of the rotating–cutter drill press.

Diagram of the abrasion rotating cutter.

6 Results and discussion

6.1 Fresh results of RCC

6.1.1 Consistency

Table 9 shows the consistency test results of all RCC mixtures.

Consistency test results of all RCC mixtures

| Mixture | PET % of cement content | MPP (kg/m³) | Consistency (Ve Be) test (s) ASTM1170 |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 (reference) | — | — | 40 |

| C2 | 1 | — | 43 |

| C3 | 2 | — | 45 |

| C4 | 3 | — | 52 |

| C5 | — | 1 | 45 |

| C6 | — | 3 | 52 |

| C7 | — | 5 | 58 |

Table 9 shows the consistency values within mixtures based on the volume fraction of PET and MPP. In RCC mixtures reinforced with PET, the Ve Be ranged from 43 to 52 s. The consistency of the reference mixture (C1) stood at 40 s, with consistency values increasing with the increase in the PET fibers. Incorporating 3.0% of PET fibers in the mixture (C4) led to a reduction in consistency to 30.0%. Moreover, the consistency decreased by 45% with the introduction of 5 kg/m3 of MPP fibers in the mixture (C7). This trend suggests that consistency diminishes as the fiber content increases, a pattern also observed by other researchers [15].

6.2 Fresh density

Table 10 shows the density test results of all RCC mixtures.

Dry density test results

| Mixture | PET % of cement content | MPP (kg/m³) | Dry density (kg/m³) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 (reference) | — | — | 2,381 |

| C2 | 1 | — | 2,375 |

| C3 | 2 | — | 2,364 |

| C4 | 3 | — | 2,355 |

| C5 | — | 1 | 2,371 |

| C6 | — | 3 | 2,350 |

| C7 | — | 5 | 2,330 |

Table 10 shows that the fresh density of RCC fluctuates based on the percentages of PET and MPP. RCC reinforced with PET and MPP indicates that the concrete’s density was minimally influenced by the presence of PET and MPP fibers.

6.3 Compressive strength

Table 11 shows the results of the compressive strength test after 7 and 28 days.

Compressive strength test results of all RCC mixtures

| Mixture | PET % of cement content | MPP (kg/m³) | Compressive strength (MPa) | Increase in compressive strength % at day 28 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 days | 28 days | ||||

| C1 | — | — | 26 | 33.8 | Reference |

| C2 | 1 | — | 26.8 | 31.7 | −6.2 |

| C3 | 2 | — | 25.3 | 30.4 | −10.0 |

| C4 | 3 | — | 23.7 | 28.7 | −15.0 |

| C5 | — | 1 | 27.2 | 39.4 | 16.5 |

| C6 | — | 3 | 30.7 | 43.9 | 29.8* |

| C7 | — | 5 | 24.8 | 31.5 | −6.8 |

*Increase in the compressive strength at day 28 = (43.9 – 33.8)/33.8 = 29.8%.

Table 11 shows that the addition of different amounts of PET leads to a decrease in compressive strengths on both days 7 and 28. These findings are consistent with earlier research [6], validating their conclusions.

Table 11 also shows that the addition of 1–3 kg/m3 of MPP leads to an increase in the compressive strength by 16.5–29.8%, while the addition of 5 kg/m3 of MPP leads to a decrease in the compressive strength by 6.8% as compared with the reference mixture. These results align with previous studies, confirming their discoveries.

6.4 Impact resistance results

Table 12 shows the test results of the impact resistance for all RCC mixtures.

Impact resistance test results of all RCC mixtures

| Mixture | PET % of cement content | MPP (kg/m³) | Impact resistance | Increase in the number of blows for failure crack % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average number of blows for first crack | Average number of blows for a failure crack | ||||

| C1 | — | — | 43 | 48 | Reference |

| C2 | 1 | — | 66 | 83 | 72.9 |

| C3 | 2 | — | 111 | 139 | 189.5 |

| C4 | 3 | — | 139 | 163 | 239.5 |

| C5 | — | 1 | 74 | 99 | 106.3 |

| C6 | — | 3 | 165 | 197 | 310.4 |

| C7 | — | 5 | 266 | 315 | 556.3* |

*Increase in the number of blows for failure crack = (315 − 48)/48 = 556.3%.

The impact resistance test results were based on the average number of strikes required to record the first and failure crack for all samples tested. This approach was chosen due to challenges in visually identifying the initial crack, which could occur in any direction within the samples. Additionally, concrete’s impact resistance is influenced by a single point of impact, which may land on either a soft mortar area or a hard aggregate particle. These considerations were applied consistently across all tests conducted on disk specimens using the composition mixtures outlined in Table 12.

Based on the data presented in Table 12, it can be observed that the inclusion of PET and MPP fibers at various ratios in the concrete mixture led to an overall increase in the average number of blows required for specimen failure. Consequently, this delay resulted in a postponed onset of both initial and failure cracking.

The appearance of the first crack recorded at 5 kg/m3 of MPP increased the average number of blows by 556.3% as compared to the reference mixture. Furthermore, the inclusion of 3% PET in the concrete mixture (C4) also delayed the appearance of the first crack with increase in average number of strikes by 239.5% as compared to the reference mixture. This result is considered logically due to the stiffness of concrete with the existence of fibers as well as their mechanical properties.

6.5 Abrasion resistance results

Table 13 shows the test results of abrasion resistance for all RCC mixtures.

Abrasion resistance test results of all RCC mixtures

| Mixture | PET % of cement content | MPP (kg/m³) | Abraded materials (g) | Increase in abrasion resistance % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | — | — | 12.61 | Reference |

| C2 | 1 | — | 13.24 | −5.0 |

| C3 | 2 | — | 13.63 | −8.0 |

| C4 | 3 | — | 14.14 | −10.8 |

| C5 | — | 1 | 10.03 | 13.3 |

| C6 | — | 3 | 9.58 | 24.0* |

| C7 | — | 5 | 13.3 | −5.4 |

*Increase in abrasion resistance % = (12.61 – 9.58)/12.61 = 24%.

Based on the data presented in Table 13, it can be observed that the inclusion of PET fibers at various ratios in the concrete mixture led to an overall decrease in the abrasion resistance.

Table 13 also shows that the addition of 1–3 kg/m3 of MPP leads to an increase in abrasion resistance by 13.3–24%, while the addition of 5 kg/m3 of MPP leads to a decrease in abrasion resistance of 5.4% as compared with the reference mixture.

7 Conclusion

New important findings of this study can be concluded as follows:

7.1 Compressive strength

PET fiber addition: Adding different amounts of PET fibers leads to a decrease in the compressive strength on both days 7 and 28. This finding is consistent with earlier research, validating the negative impact of PET fibers on the compressive strength.

MPP fiber addition: The addition of 1–3 kg/m³ of MPP fibers increases the compressive strength by 16.5–29.8%. However, adding 5 kg/m³ of MPP fibers results in a 6.8% decrease in the compressive strength compared to the reference mixture.

7.2 Impact resistance

Overall improvement: The inclusion of PET and MPP fibers at various ratios in the concrete mixture leads to an overall increase in the impact resistance for all mixtures compared to the reference mixture

Specific increases: The addition of 3% PET fibers increases the average number of strikes required for failure by 239.5%, while 5 kg/m³ of MPP fibers increases it by 556.3% compared to the reference mixture.

7.3 Abrasion resistance

PET fiber addition: The inclusion of PET fibers at various ratios and 5 kg/m³ MPP in the concrete mixture leads to an overall decrease in the abrasion resistance compared to the reference mixture.

MPP fiber addition: The inclusion of 1–3 kg/m³ of MPP fibers increases the abrasion resistance by 13.3–24%.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their heartfelt thanks to Northern Technical University for generously providing all the facilities and essential scientific support required to complete this work.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. Mohammed Hazim Yaseen conducted the experiments under the supervision of the Syed Fuad Saiyid Hashim, Eethar Thanon Dawood, and Megat Azmi Megat Johari. The writing of the paper was viewed and revised by Megat Azmi Megat Johari.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] El-Nemr A, Shaaban IG. Assessment of special rubberized concrete types utilizing portable non-destructive tests. NDT. 2024;2(3):160–89. 10.3390/ndt2030010.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Yaseen MH, Abbu M, Numan HA. Influence of adding different amounts of polyethylene terephthalate on the mechanical properties of gypsum. Int J Civil Eng Tech. 2018;9(10):1721–31.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Yaseen MH, Hashim SFS, Dawood ET, Johari MAM. Effect of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) in development of green roller compacted concrete. Constr Technol Archit. 2023;10:31–9. 10.4028/p-c6l8ag.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Karthikeyan S, Ramgughan B. Experimental investigation of effect of waste PET fibres on the impact behaviour of PET fibre reinforced concrete. Glob NEST J. 2024;26(3):1–5. 10.30955/gnj.005202.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Yan Z, Bai Y, Chen W. Dynamic compressive behaviors of polyethylene terephthalate fiber reinforced recycled aggregate concrete. Struct Concr. 2024;25(5):3883–901. 10.1002/suco.202300756.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Bai YL, Yan ZW, Ozbakkaloglu T, Dai JG, Jia JF, Jia JB. Dynamic behavior of PET FRP and its preliminary application in impact strengthening of concrete columns. Appl Sci. 2019;9(23):4987. 10.3390/app9234987.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Abed ZM, Khalil WI, Ahmed HK. Effect of waste tire products on some characteristics of roller-compacted concrete. Open Eng. 2024;14(1):20220559. 10.1515/eng-2022-0559.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Rambabu D, Sharma SK, Akbar MA. Evaluation of roller compacted concrete for its application as high traffic resisting pavements with fatigue analysis. Constr Build Mater. 2023;401:132977. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132977.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Iraqi Organization Standardization and Quality Control. No. 5, Standard Specifications for Portland cement. Baghdad, Iraq; 2019.Search in Google Scholar

[10] American Concrete Institute Committee ACI 211.3R. Guide for selecting proportions for no-slump concrete; 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[11] ASTM C1170. Standard test method for determining consistency and density of roller compacted concrete using a vibrating table. Philadelphia, United States: American Society for Testing and Materials; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[12] B.S.: 1881: Part 116. Method of testing hardened concrete for other strength. London, United Kingdom: British Standard Institution; 1983.Search in Google Scholar

[13] ACI 544.2R-89 (Reapproved 1999), MCP2005 2005. Measurement of properties of fiber reinforced concrete. Reported by ACI Committee 544, on CD. American Concrete Institute; 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[14] ASTM C944-15. Standard test method for abrasion resistance of concrete or mortar surfaces by the rotating-cutter method. Philadelphia: The American Society for Testing and Materials; 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Topçu İB, Canbaz M. Effect of different fibers on the mechanical properties of concrete containing fly ash. Constr Build Mater. 2006;21(7):1486–91. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2006.06.026.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Modification of polymers to synthesize thermo-salt-resistant stabilizers of drilling fluids

- Study of the electronic stopping power of proton in different materials according to the Bohr and Bethe theories

- AI-driven UAV system for autonomous vehicle tracking and license plate recognition

- Enhancement of the output power of a small horizontal axis wind turbine based on the optimization approach

- Design of a vertically stacked double Luneburg lens-based beam-scanning antenna at 60 GHz

- Synergistic effect of nano-silica, steel slag, and waste glass on the microstructure, electrical resistivity, and strength of ultra-high-performance concrete

- Expert evaluation of attachments (caps) for orthopaedic equipment dedicated to pedestrian road users

- Performance and rheological characteristics of hot mix asphalt modified with melamine nanopowder polymer

- Second-order design of GNSS networks with different constraints using particle swarm optimization and genetic algorithms

- Impact of including a slab effect into a 2D RC frame on the seismic fragility assessment: A comparative study

- Analytical and numerical analysis of heat transfer from radial extended surface

- Comprehensive investigation of corrosion resistance of magnesium–titanium, aluminum, and aluminum–vanadium alloys in dilute electrolytes under zero-applied potential conditions

- Performance analysis of a novel design of an engine piston for a single cylinder

- Modeling performance of different sustainable self-compacting concrete pavement types utilizing various sample geometries

- The behavior of minors and road safety – case study of Poland

- The role of universities in efforts to increase the added value of recycled bucket tooth products through product design methods

- Adopting activated carbons on the PET depolymerization for purifying r-TPA

- Urban transportation challenges: Analysis and the mitigation strategies for road accidents, noise pollution and environmental impacts

- Enhancing the wear resistance and coefficient of friction of composite marine journal bearings utilizing nano-WC particles

- Sustainable bio-nanocomposite from lignocellulose nanofibers and HDPE for knee biomechanics: A tribological and mechanical properties study

- Effects of staggered transverse zigzag baffles and Al2O3–Cu hybrid nanofluid flow in a channel on thermofluid flow characteristics

- Mathematical modelling of Darcy–Forchheimer MHD Williamson nanofluid flow above a stretching/shrinking surface with slip conditions

- Energy efficiency and length modification of stilling basins with variable Baffle and chute block designs: A case study of the Fewa hydroelectric project

- Renewable-integrated power conversion architecture for urban heavy rail systems using bidirectional VSC and MPPT-controlled PV arrays as an auxiliary power source

- Exploitation of landfill gas vs refuse-derived fuel with landfill gas for electrical power generation in Basrah City/South of Iraq

- Two-phase numerical simulations of motile microorganisms in a 3D non-Newtonian nanofluid flow induced by chemical processes

- Sustainable cocoon waste epoxy composite solutions: Novel approach based on the deformation model using finite element analysis to determine Poisson’s ratio

- Impact and abrasion behavior of roller compacted concrete reinforced with different types of fibers

- Architectural design and its impact on daylighting in Gayo highland traditional mosques

- Structural and functional enhancement of Ni–Ti–Cu shape memory alloys via combined powder metallurgy techniques

- Design of an operational matrix method based on Haar wavelets and evolutionary algorithm for time-fractional advection–diffusion equations

- Design and optimization of a modified straight-tapered Vivaldi antenna using ANN for GPR system

- Analysis of operations of the antiresonance vibration mill of a circular trajectory of chamber vibrations

- Functions of changes in the mechanical properties of reinforcing steel under corrosive conditions

- Enhanced PAPR reduction in NOMA systems using modified SLM and PTS techniques for power-efficient 5G and beyond networks

- Hybrid mechanics-informed machine learning models for predicting mechanical failure in graphene sponge: a low-data strategy for mechanical engineering applications

- Design of shafts of a two-piece chain conveyor as a part of a modification of a mobile working machine

- Review Articles

- A modified adhesion evaluation method between asphalt and aggregate based on a pull off test and image processing

- Architectural practice process and artificial intelligence – an evolving practice

- 10.1515/eng-2025-0148

- Special Issue: 51st KKBN - Part II

- The influence of storing mineral wool on its thermal conductivity in an open space

- Use of nondestructive test methods to determine the thickness and compressive strength of unilaterally accessible concrete components of building

- Use of modeling, BIM technology, and virtual reality in nondestructive testing and inventory, using the example of the Trzonolinowiec

- Tunable terahertz metasurface based on a modified Jerusalem cross for thin dielectric film evaluation

- Integration of SEM and acoustic emission methods in non-destructive evaluation of fiber–cement boards exposed to high temperatures

- Non-destructive method of characterizing nitrided layers in the 42CrMo4 steel using the amplitude-frequency technique of eddy currents

- Evaluation of braze welded joints using the ultrasonic method

- Analysis of the potential use of the passive magnetic method for detecting defects in welded joints made of X2CrNiMo17-12-2 steel

- Analysis of the possibility of applying a residual magnetic field for lack of fusion detection in welded joints of S235JR steel

- Eddy current methodology in the non-direct measurement of martensite during plastic deformation of SS316L

- Methodology for diagnosing hydraulic oil in production machines with the additional use of microfiltration

- Special Issue: IETAS 2024 - Part II

- Enhancing communication with elderly and stroke patients based on sign-gesture translation via audio-visual avatars

- Optimizing wireless charging for electric vehicles via a novel coil design and artificial intelligence techniques

- Evaluation of moisture damage for warm mix asphalt (WMA) containing reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP)

- Comparative CFD case study on forced convection: Analysis of constant vs variable air properties in channel flow

- Evaluating sustainable indicators for urban street network: Al-Najaf network as a case study

- Node failure in self-organized sensor networks

- Comprehensive assessment of side friction impacts on urban traffic flow: A case study of Hilla City, Iraq

- Design a system to transfer alternating electric current using six channels of laser as an embedding and transmitting source

- Security and surveillance application in 3D modeling of a smart city: Kirkuk city as a case study

- Modified biochar derived from sewage sludge for purification of lead-contaminated water

- The future of space colonisation: Architectural considerations

- Design of a Tri-band Reconfigurable Antenna Using Metamaterials for IoT Applications

- Special Issue: AESMT-7 - Part II

- Experimental study on behavior of hybrid columns by using SIFCON under eccentric load

- Special Issue: ICESTA-2024 and ICCEEAS-2024

- A selective recovery of zinc and manganese from the spent primary battery black mass as zinc hydroxide and manganese carbonate

- Special Issue: REMO 2025 and BUDIN 2025

- Predictive modeling coupled with wireless sensor networks for sustainable marine ecosystem management using real-time remote monitoring of water quality

- Management strategies for refurbishment projects: A case study of an industrial heritage building

- Structural evaluation of historical masonry walls utilizing non-destructive techniques – Comprehensive analysis

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Modification of polymers to synthesize thermo-salt-resistant stabilizers of drilling fluids

- Study of the electronic stopping power of proton in different materials according to the Bohr and Bethe theories

- AI-driven UAV system for autonomous vehicle tracking and license plate recognition

- Enhancement of the output power of a small horizontal axis wind turbine based on the optimization approach

- Design of a vertically stacked double Luneburg lens-based beam-scanning antenna at 60 GHz

- Synergistic effect of nano-silica, steel slag, and waste glass on the microstructure, electrical resistivity, and strength of ultra-high-performance concrete

- Expert evaluation of attachments (caps) for orthopaedic equipment dedicated to pedestrian road users

- Performance and rheological characteristics of hot mix asphalt modified with melamine nanopowder polymer

- Second-order design of GNSS networks with different constraints using particle swarm optimization and genetic algorithms

- Impact of including a slab effect into a 2D RC frame on the seismic fragility assessment: A comparative study

- Analytical and numerical analysis of heat transfer from radial extended surface

- Comprehensive investigation of corrosion resistance of magnesium–titanium, aluminum, and aluminum–vanadium alloys in dilute electrolytes under zero-applied potential conditions

- Performance analysis of a novel design of an engine piston for a single cylinder

- Modeling performance of different sustainable self-compacting concrete pavement types utilizing various sample geometries

- The behavior of minors and road safety – case study of Poland

- The role of universities in efforts to increase the added value of recycled bucket tooth products through product design methods

- Adopting activated carbons on the PET depolymerization for purifying r-TPA

- Urban transportation challenges: Analysis and the mitigation strategies for road accidents, noise pollution and environmental impacts

- Enhancing the wear resistance and coefficient of friction of composite marine journal bearings utilizing nano-WC particles

- Sustainable bio-nanocomposite from lignocellulose nanofibers and HDPE for knee biomechanics: A tribological and mechanical properties study

- Effects of staggered transverse zigzag baffles and Al2O3–Cu hybrid nanofluid flow in a channel on thermofluid flow characteristics

- Mathematical modelling of Darcy–Forchheimer MHD Williamson nanofluid flow above a stretching/shrinking surface with slip conditions

- Energy efficiency and length modification of stilling basins with variable Baffle and chute block designs: A case study of the Fewa hydroelectric project

- Renewable-integrated power conversion architecture for urban heavy rail systems using bidirectional VSC and MPPT-controlled PV arrays as an auxiliary power source

- Exploitation of landfill gas vs refuse-derived fuel with landfill gas for electrical power generation in Basrah City/South of Iraq

- Two-phase numerical simulations of motile microorganisms in a 3D non-Newtonian nanofluid flow induced by chemical processes

- Sustainable cocoon waste epoxy composite solutions: Novel approach based on the deformation model using finite element analysis to determine Poisson’s ratio

- Impact and abrasion behavior of roller compacted concrete reinforced with different types of fibers

- Architectural design and its impact on daylighting in Gayo highland traditional mosques

- Structural and functional enhancement of Ni–Ti–Cu shape memory alloys via combined powder metallurgy techniques

- Design of an operational matrix method based on Haar wavelets and evolutionary algorithm for time-fractional advection–diffusion equations

- Design and optimization of a modified straight-tapered Vivaldi antenna using ANN for GPR system

- Analysis of operations of the antiresonance vibration mill of a circular trajectory of chamber vibrations

- Functions of changes in the mechanical properties of reinforcing steel under corrosive conditions

- Enhanced PAPR reduction in NOMA systems using modified SLM and PTS techniques for power-efficient 5G and beyond networks

- Hybrid mechanics-informed machine learning models for predicting mechanical failure in graphene sponge: a low-data strategy for mechanical engineering applications

- Design of shafts of a two-piece chain conveyor as a part of a modification of a mobile working machine

- Review Articles

- A modified adhesion evaluation method between asphalt and aggregate based on a pull off test and image processing

- Architectural practice process and artificial intelligence – an evolving practice

- 10.1515/eng-2025-0148

- Special Issue: 51st KKBN - Part II

- The influence of storing mineral wool on its thermal conductivity in an open space

- Use of nondestructive test methods to determine the thickness and compressive strength of unilaterally accessible concrete components of building

- Use of modeling, BIM technology, and virtual reality in nondestructive testing and inventory, using the example of the Trzonolinowiec

- Tunable terahertz metasurface based on a modified Jerusalem cross for thin dielectric film evaluation

- Integration of SEM and acoustic emission methods in non-destructive evaluation of fiber–cement boards exposed to high temperatures

- Non-destructive method of characterizing nitrided layers in the 42CrMo4 steel using the amplitude-frequency technique of eddy currents

- Evaluation of braze welded joints using the ultrasonic method

- Analysis of the potential use of the passive magnetic method for detecting defects in welded joints made of X2CrNiMo17-12-2 steel

- Analysis of the possibility of applying a residual magnetic field for lack of fusion detection in welded joints of S235JR steel

- Eddy current methodology in the non-direct measurement of martensite during plastic deformation of SS316L

- Methodology for diagnosing hydraulic oil in production machines with the additional use of microfiltration

- Special Issue: IETAS 2024 - Part II

- Enhancing communication with elderly and stroke patients based on sign-gesture translation via audio-visual avatars

- Optimizing wireless charging for electric vehicles via a novel coil design and artificial intelligence techniques

- Evaluation of moisture damage for warm mix asphalt (WMA) containing reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP)

- Comparative CFD case study on forced convection: Analysis of constant vs variable air properties in channel flow

- Evaluating sustainable indicators for urban street network: Al-Najaf network as a case study

- Node failure in self-organized sensor networks

- Comprehensive assessment of side friction impacts on urban traffic flow: A case study of Hilla City, Iraq

- Design a system to transfer alternating electric current using six channels of laser as an embedding and transmitting source

- Security and surveillance application in 3D modeling of a smart city: Kirkuk city as a case study

- Modified biochar derived from sewage sludge for purification of lead-contaminated water

- The future of space colonisation: Architectural considerations

- Design of a Tri-band Reconfigurable Antenna Using Metamaterials for IoT Applications

- Special Issue: AESMT-7 - Part II

- Experimental study on behavior of hybrid columns by using SIFCON under eccentric load

- Special Issue: ICESTA-2024 and ICCEEAS-2024

- A selective recovery of zinc and manganese from the spent primary battery black mass as zinc hydroxide and manganese carbonate

- Special Issue: REMO 2025 and BUDIN 2025

- Predictive modeling coupled with wireless sensor networks for sustainable marine ecosystem management using real-time remote monitoring of water quality

- Management strategies for refurbishment projects: A case study of an industrial heritage building

- Structural evaluation of historical masonry walls utilizing non-destructive techniques – Comprehensive analysis