Abstract

In this study, a simple method was developed for the aggregation of graphene oxide (GO) with the addition of NaCl to concentrate and separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) from water samples, and this method was used as a environmentally friendly method for the determination of PAHs. We demonstrate the uniform dispersion of GO sheets in aqueous samples for the fast high-efficiency adsorption of PAHs. Aggregation occurred immediately upon elimination of electrostatic repulsion by adding NaCl to neutralize the excessive negative charges on the surfaces of the GO sheets. The aggregates of GO and PAHs were separated and treated with hexane to form a slurry. The slurry was filtered and subjected to gas chromatography–mass spectroscopy (GC-MS) analysis. Based on a 40-mL sample volume, limits of detection of 10–30 ng L-1 were obtained for 16 PAHs, with correlation coefficients (R2) exceeding 0.99. The method yielded good recovery, ranging from 80 to 111% and 80 to 107% for real spiked water samples at 100 and 500 ng L-1, respectively. Compared to traditional solid-phase extraction and liquid–liquid extraction methods, this method is free of organic reagents in the pretreatment procedure and uses only 1 mL hexane for sample introduction.

1 Introduction

Environmentally friendly (green) analytical methodologies are in high demand to reduce the risks of chemical use to humans and the environment [1]. However, the traditional analytical methods used to detect environmental pollutants often contribute to further pollution through the chemicals used in analysis, as hazardous chemicals are required for analytical sample preparation, quality control, and calibration [2,3]. Sometimes these chemicals are more toxic than the original analyzed sample. Therefore, the development of novel green analytical methods remains necessary.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are a class of common and persistent environmental pollutants containing three or more benzene rings, and they are toxic to aquatic animals and humans [4]. PAHs are frequently found in the soil, air and water, where they can negatively impact human health [5]. Therefore, the rapid and sensitive determination of PAH compounds in environmental samples is urgently needed [6,7,8,9]. However, the traditional liquid–liquid [10] and solid-phase (SPE) [11,12] methods for extraction before determination of PAHs usually consume large quantities of solvents, which lead to further polluting of the environment [13,14,15,16].

Graphene oxide (GO) is a two-dimensional carbon nanomaterial that has attracted significant scientific attention in recent years [17,18,19]. GO can be obtained by the strong oxidation of graphite; it possesses a layered structure and negatively charged surfaces [20]. At the edges of the carbon layers, dense carboxyl groups significantly affect the van der Waals interactions among adjacent graphene layers and render the material strongly hydrophilic [21,22]. Thus, many hydrophilic and polar substances including pigments [23,24], endogenous estrogen [25], heavy metal ions [26,27], phenols [28], and basic species [29] can be adsorbed onto the GO surface through hydrogen bonding, anion-π, and electrostatic interactions [30,31].

GO has been reported to adsorb PAH compounds with high efficiency [31]. However, the complete removal of small GO sheets from a well-dispersed solution is difficult. The traditional separation methods of highspeed centrifugation and filtering through 0.22-μm porous membrane filters are usually relatively cumbersome, time-consuming, and inefficient, and they typically result in incomplete separation. When GO is used to adsorb target compounds, the separation of GO from the solution remains slow and difficult. Fortunately, GO can form stable aqueous colloids that aggregate by changing the pH [32,33] or adding electrolyte solutions [34,35]. Based on this theory, GO was successfully used to extract and separate trace toxic metals including Pb, Cd, Bi, and Sb [36].

Recently, carbon nanomaterials were also applied successfully to the extraction and separation of organic compounds through SPE. For example, graphene has been used as a sorbent for the isolation of propyl gallate and butylated hydroxyanisole from complex food sample matrices [37]. Magnetic SPE based Fe3O4@GO nanocomposite was also used to extract ethyl vanillin, trans-cinnamic acid, methyl cinnamate, ethyl cinnamate, and benzyl cinnamate from food samples [38]. However, carbon nanomaterial packed in a SPE cartridge usually becomes increasingly more compact during elution due to an aggregation phenomenon, which decreases extraction and purification efficiency over time. Moreover, large amounts of organic solvent are consumed in the elution of SPE column. Therefore, the aggregation of GO by adding electrolytes in liquid samples was applied to potentially improve the efficiency of the nanomaterial and to reduce the consumption of organic solvents.

The aim of this work was to investigate the impact of the aggregation of GO by introducing NaCl as an electrolyte solute during the extraction of PAHs from water. The isolated GO-adsorbed PAH aggregates were transferred to a GC-MS detection system using a hexane solution for the introduction of a liquid sample. By exploiting the superior properties of GO, the proposed method showed excellent extraction efficiency and minimal organic solvent consumption compared to those in traditional methods.

2 Experimental Section

2.1 Materials and Reagents

All chemicals used in this work were of at least analytical grade. All solutions were prepared using 18 MΩ·cm deionized water (DIW) produced by a water-purification system (Millipore, USA). Commercial GO (thickness 0.55–1.2 nm, purity > 95 wt%; size 0.5–3 μm) was obtained from Chengdu Organic Chemicals Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China). The GO solution of 1.0 mg mL-1 prepared with DIW was used directly for the extraction. The liquid PAH standards (1000 mg L-1) dissolved in methanol were purchased from the Agro-Environment Protection Institute (Tianjin, China). The selected PAHs were defined and nominated as priority pollutants by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), including naphthalene (NAP), acenaphthylene (ANY), acenaphthene (ANA), fluorene (FLU), phenanthrene (PHE), anthracene (ANT), fluoranthene (FLT), pyrene (PYR), benzo(a)anthracene (BaA), chrysene (CHR), benzo(b) fluoranthene (BbF), benzo(k)fluoranthene (BkF), benzo(a) pyrene (BaP), indeno(1,2,3-cd)pyrene (IPY), dibenzo(a, h) anthracene (DBA), and benzo(g, h, i)perylene (BPE). A stock solution of each compound with the concentration of 10 mg L-1 was prepared in acetone and stored in amber screwcapped glass vials in the dark at –20°C. Working solutions were prepared daily by the appropriate dilution of the stock solutions with hexane before use. NaCl and other reagents were purchased from Guangzhou Chemical Reagent Factory (Guangzhou, China).

2.2 Extraction Procedure

A total of 15 water samples were used to evaluate the accuracy of the proposed method. Five river, five lake and five sea water samples were collected from Nandu River, Hongcheng Lake and Holiday Beach of Haikou, Hainan province of China. The samples were collected in precleaned quartz bottles and directly transported to the laboratory for immediate study after filtration with 0.22-μm membrane filters. A 40-mL portion of each water sample was accurately weighed and placed directly in a 50-mL precleaned Teflon centrifuge tube. After that, 4.0 mL of a high concentration (1 mg mL-1) of the GO dispersion was added to the tubes, which were allowed to mix for 5 min to achieve the complete adsorption of the analyte PAHs. When NaCl was added and mixed with the GO in the sample solution, GO aggregated quickly and was gradually deposited on the bottom of the tubes. Complete phase separation was accomplished by centrifuging for 5 min at 15000 rpm (high-speed refrigerated centrifuge, CR22N, Hitachi, Japan). The supernatant was transferred to another pre-cleaned 50-mL centrifuge tube, and another 4.0 mL of GO solution was added for a second extraction as described above. The second supernatant was discarded and the GO aggregates were mixed to slurry with 1 mL hexane. The slurry was centrifuged for 1 min at 15000 rpm and the supernatant was filtered through 0.22 μm membrane (Tianjin Jinteng Experiment Equipment Ltd., Co., Tianjin, China) automatic sampling and analyzed by GC-MS.

2.3 GC-MS Analysis

The selected PAHs were analyzed on a Trace GC Ultra equipped with a DSQ ⍰ quadrupole MS system (Thermo, USA). Liquid samples of 1 μL each were injected to the GC apparatus via a TriPlus RSH Autosampler by the headspace and liquid mode, respectively. The GC analyzer was equipped with a Thermo Scientific TR-5MS column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm). He (purity ≥ 99.999%) was used as the carrier gas at the flow rate of 1.5 mL min-1. The oven temperature program was set as follows: 45°C for 0.8 min, heated to 150°C at 25°C min-1, then to 200°C at 3°C min-1, and finally to 280°C at 8°C min-1 for 18 min. The injection port, ion source, and interface temperatures were 250, 230, and 280°C, respectively. The MS detector was operated in the electron ionization (EI) mode with an ionizing energy of 70 eV. The selective ion monitoring mode was adopted for the quantitative determination of the analytes, and the selected ion masses are listed in Table 1.

Analytical performances of the developed method.

| PAHs | Retention time (min) | Selected ions | Regression equation | r2 | Liner range (ng L-1) | LODs (ng L-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAP | 6.05 | 128[a], 129, 127 | Y=0.982x+0.003 | 0.996 | 50-2000 | 10 |

| ANY | 9.29 | 152[a], 151, 153 | Y=0.983x+0.003 | 0.998 | 50-2000 | 10 |

| ANA | 9.81 | 153[a], 154, 152 | Y=0.970x+0.005 | 0.997 | 50-2000 | 10 |

| FLU | 11.74 | 166[a], 165, 167 | Y=1.003x-0.001 | 0.999 | 50-2000 | 10 |

| PHE | 16.83 | 178[a], 179, 152 | Y=0.995x+0.001 | 0.999 | 50-2000 | 15 |

| ANT | 16.55 | 178[a], 179,176 | Y=1.002x-0.001 | 0.999 | 50-2000 | 15 |

| FLT | 24.61 | 202[a], 101, 100 | Y=0.987x+0.002 | 0.999 | 50-2000 | 15 |

| PYR | 26.71 | 202[a], 200, 203 | Y=0.938x+0.008 | 0.995 | 50-2000 | 15 |

| BaA | 42.27 | 228[a], 226, 229 | Y=0.944x+0.008 | 0.994 | 50-2000 | 15 |

| CHR | 42.50 | 228[a], 229, 226 | Y=0.945x+0.008 | 0.994 | 50-2000 | 15 |

| BbF | 47.52 | 252[a], 253, 125 | Y=1.003x-0.001 | 0.999 | 50-2000 | 20 |

| BKF | 47.65 | 252[a], 253, 250 | Y=1.002x-0.001 | 0.999 | 50-2000 | 20 |

| BaP | 48.96 | 252[a], 253, 250 | Y=1.022x-0.004 | 0.999 | 50-2000 | 20 |

| IPY | 55.49 | 276[a], 277, 138 | Y=0.985x+0.003 | 0.997 | 50-2000 | 30 |

| DBA | 55.81 | 278[a], 276, 139 | Y=0.996x-0.001 | 0.999 | 50-2000 | 30 |

| BPE | 57.40 | 276[a], 274, 138 | Y=1.009x-0.001 | 0.999 | 50-2000 | 30 |

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animals use.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Proposed Mechanism of Aggregation

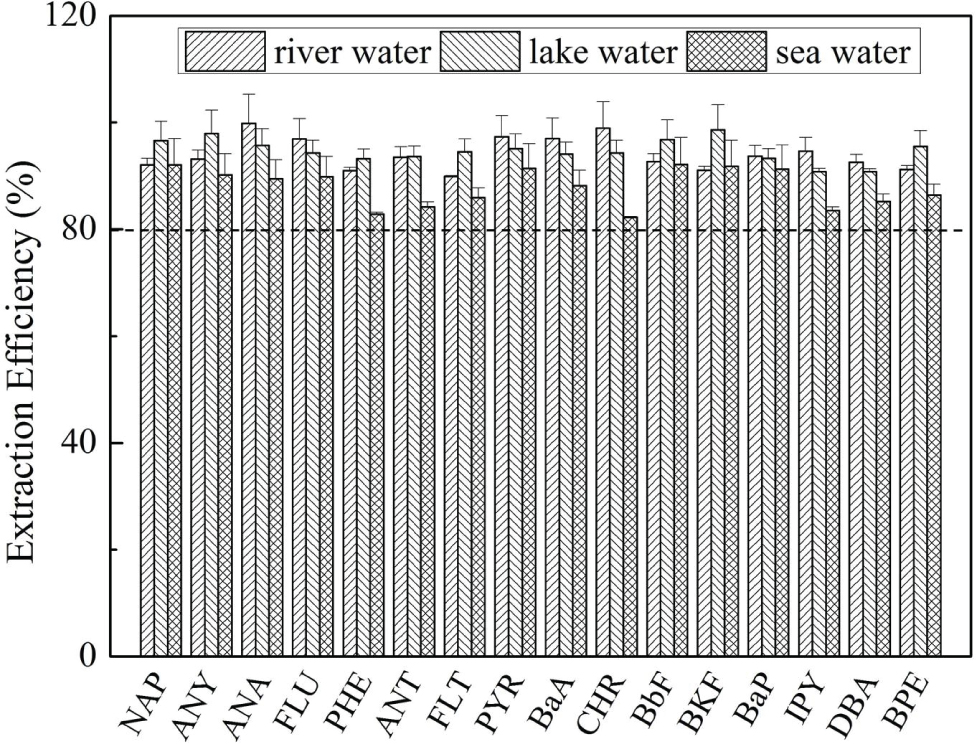

GO is regarded as a promising nanomaterial for the adsorption of pollutants because it features abundant O-containing functional groups, large surface areas, highly negative surface charge, and high adsorption capacity. The first study was designed to test whether PAHs could be adsorbed onto GO from water samples with high efficiency. Therefore, the river, lake, and sea water samples were treated for 10 min in the presence of GO to permit adsorption, and the contents of PAHs in pre- and post-treatment samples were determined with a standard SPE method [39]. The results (Fig 1) demonstrate that GO successfully adsorbed the PAHs.

Extraction efficiency of PAHs with GO from river, lake and sea water.

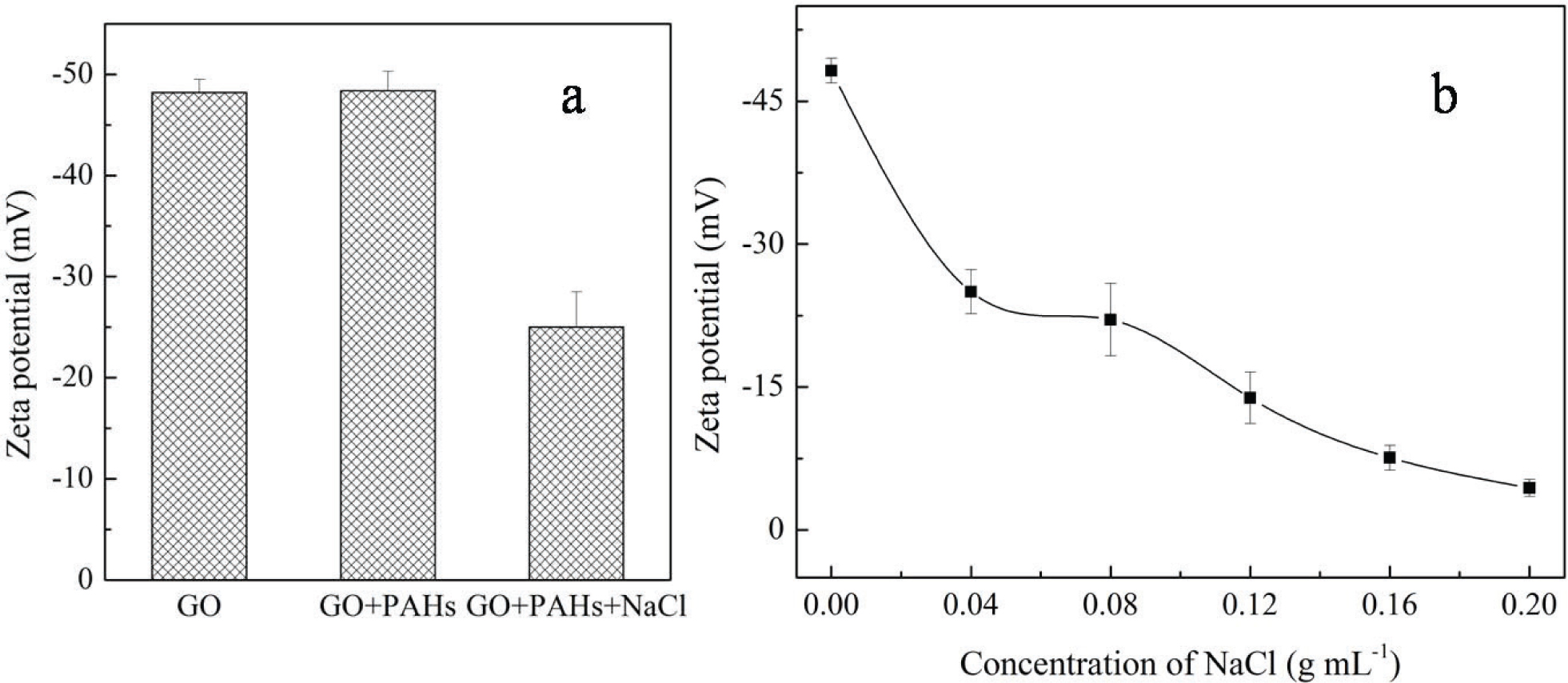

After adsorption, the GO solution must be aggregated for the separation of PAHs from the water sample. The GO sheets are highly negatively charged because of the edge carboxyl groups. Aqueous colloids and dispersions are stabilized via electrostatic repulsion; therefore, the dispersion and aggregation of GO depend on the degree of ionization of its carboxylic acid and phenolic hydroxyl groups. In this study, NaCl was chosen to neutralize the excessive negative charges and decrease the electrostatic repulsion to accomplish GO aggregation. The effect of NaCl on the zeta potential of GO was thus evaluated by an MPT-2 Zetasizer Nano (Malvern, England), with results summarized in Figure 2. The change in zeta potential upon the introduction of 1000 μg·L-1 PAHs was negligible (Figure 2a), demonstrating that the GO solvent maintains good dispersion under high concentrations of PAHs. However, once 0.04 g mL-1 of NaCl was added to the GO solvent, the zeta potentials decreased sharply from –48.4 to –25.0 mV. The effects of different NaCl masses on the zeta potential of 1 mg mL-1 GO were studied as shown in Figure 2b. When the mass of NaCl was increased from 0.04 to 0.20 g mL-1, the zeta potential gradually increased from –25.0 to –4.4 mV. A previous study found that instability in colloid dispersions, caused by insufficient mutual repulsion, appeared when the absolute zeta potential values were <30 mV [34,40]. This proves that the introduction of NaCl can achieve GO aggregation and phase separation.

Zeta potential measurement of GO suspensions: (a) Zeta potential values after addition of PAHs (1000 μg mL-1) and NaCl (0.04 g mL-1) into GO suspensions (1 mg mL-1), and (b) Zeta potential of GO at 1 mg mL-1 as a function of NaCl.

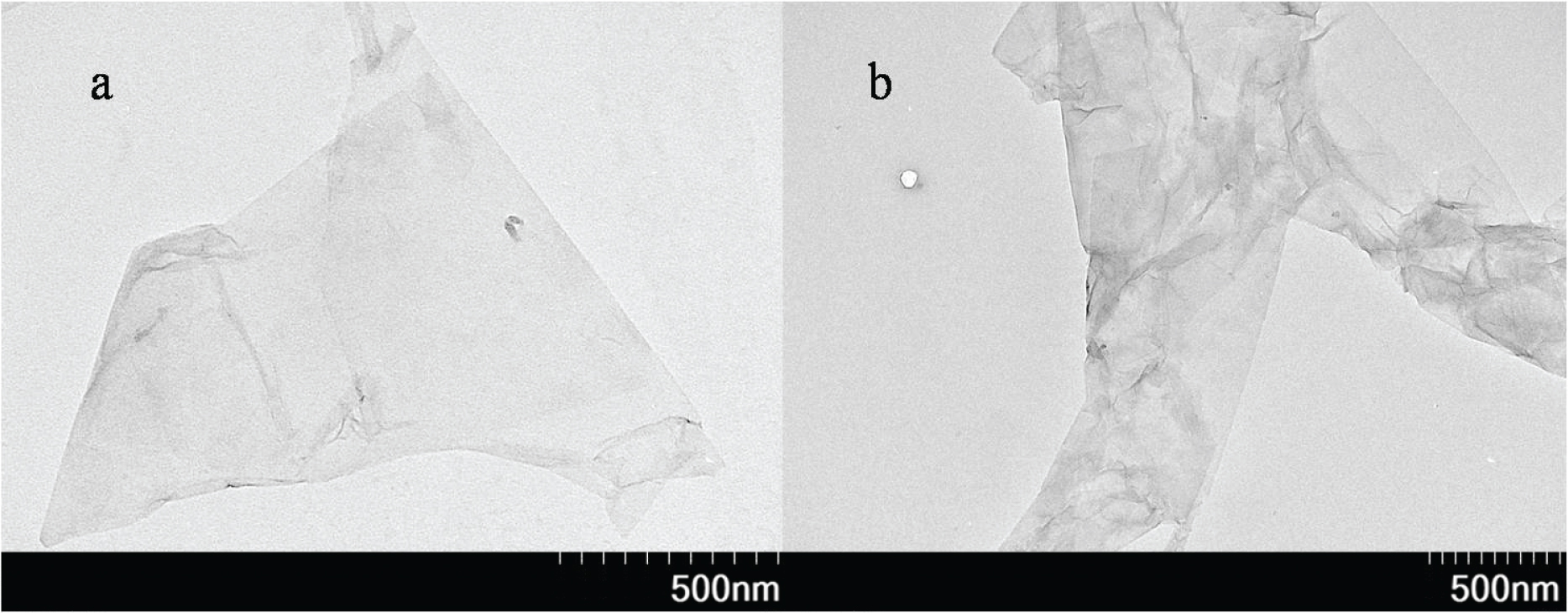

To further illuminate the morphologies of the GO sheets, transmission electron microscopy (TEM, HT7700, Hitachi, Japan) was used to observe changes in the images of GO after the addition of NaCl, with results summarized in Figure 3. In Figure 3a, a large GO sheet with intrinsic wrinkles is observed. Figure 3b shows the aggregated GO sheets, confirming that the neutralization of GO negative charges by NaCl induced GO aggregation in aqueous GO suspensions.

TEM images of GO suspensions (a), and GO+PAHs+NaCl (b).

3.2 Optimization of Extraction Conditions

To optimize the adsorption conditions of PAHs by GO, DIW water spiked with the sixteen kinds of PAHs at concentrations of 200 ng L-1 were used for sequential assessments. The extraction efficiency was evaluated by the recovery of the spiked PAHs.

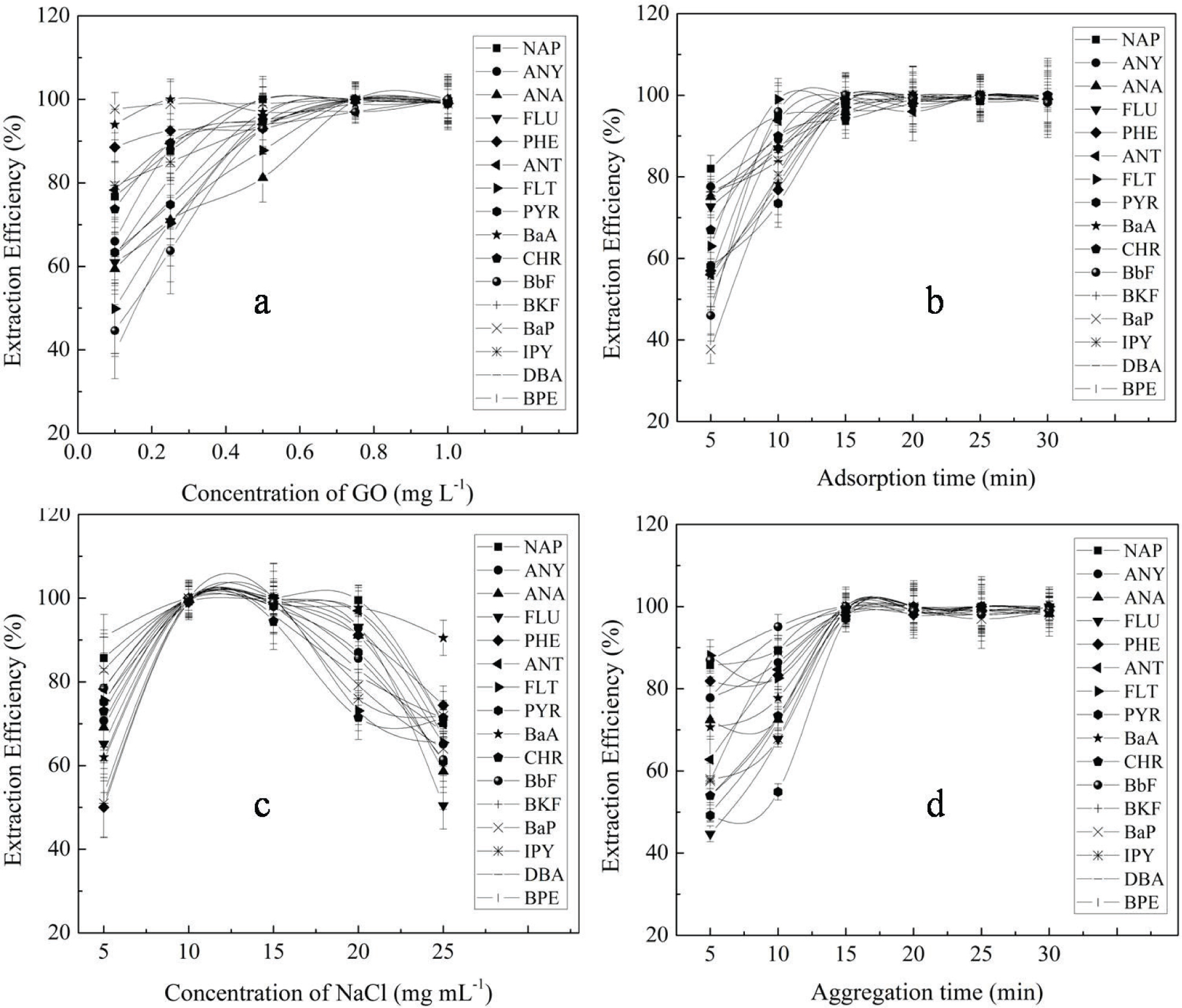

As mentioned earlier, GO displays high affinity for the PAHs. However, the mass of the GO strongly affected the adsorption capacity for the analytes, which affected the extraction efficiency. In this work, the adsorption capacities of GO for PAHs were first investigated by adding 4.0 mL of GO dispersion solutions with different concentrations (0.10–1.00 mg mL-1) to a series of 40-mL solutions containing 200 ng L-1 PAHs. The results are summarized in Figure 4a, which shows that the extraction efficiencies of all four tested PAH targets increased with increased mass of GO. A plateau for each analyte was obtained in the range of 2.0 to 4.0 mg GO. Lower masses of GO resulted in the inefficient adsorption of the analytes because of the limited adsorption capacity of GO. Therefore, 4 mL of GO at 0.75 mg mL-1 was used for all subsequent extractions in this work.

Optimization of the effects of influencing parameters on the extraction efficiency of PAHs. (a) Effect of concentration of GO. Adsorption time, 15 min; concentration of NaCl, 10 mg mL-1; and aggregation time, 15 min. (b) Effect of concentration of Adsorption time. Concentration of GO, 1.0 mg L-1; concentration of NaCl, 10 mg mL-1; and aggregation time, 15 min. (c) Effect of concentration of NaCl. Concentration of GO, 1.0 mg L-1; adsorption time, 15 min; and aggregation time, 15 min. (a) Effect of aggregation time. Concentration of GO, 1.0 mg L-1; adsorption time, 15 min; and concentration of NaCl, 10 mg mL-1.

The adsorption time of the PAHs onto GO is another critical parameter for the proposed method. Therefore, the effects of adsorption time were also studied, with results summarized in Figure 4b. All PAH compound recoveries increased with adsorption time in the range of 5 to 15 min. A plateau occurred for times exceeding 15 min, indicating that the GO and PAHs reach equilibrium in 15 min. The adsorption time of 15 min was thus applied in subsequent experiments.

In the extraction, NaCl was chosen to neutralize the excessive negative charges and decrease the electrostatic repulsion to induce GO aggregation. Therefore, the effect of the concentration of NaCl on the extraction efficiency was investigated using 200 ng L-1 PAHs as the test samples. Results of these experiments are shown in Figure 4c. A plateau of extraction efficiency for each PAH compound occurs in the range of 10–15 mg mL-1 NaCl solution. The recoveries are decreased for both higher and lower concentrations of NaCl. Lower NaCl concentrations resulted in inefficient GO aggregation and poor extraction efficiency of the analytes from the aqueous phase, while higher NaCl concentrations induced low analyte recovery from GO because of competition between Na+ and the PAHs. Therefore, the NaCl concentration of 10 mg mL-1 was used for further experiments.

The GO aggregation could be observed immediately upon the addition of NaCl. However, the deposition time was assessed to determine whether GO was completely deposited. Different deposition times were selected to evaluate the efficiency of GO aggregation, and the results were summarized in Figure 4d. The recoveries of all analytes reached 40–80% for the deposition time of 5 min, and recoveries increased to 60–90% after 10 min. For longer times, the recoveries plateau at approximately 100% for each analyte, indicating a deposition balance between NaCl and the GO solution. Therefore, we repeated the GO extraction and aggregation twice with 15 min allotted for each aggregation in subsequent studies to enhance the recoveries of the PAH compounds.

3.3 Interference

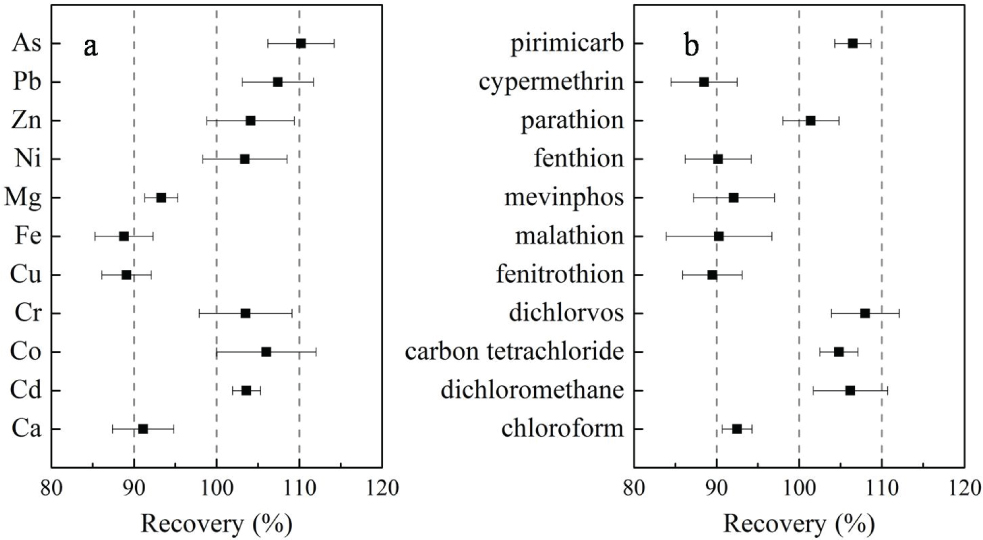

GO demonstrated high efficiency for PAH adsorption. However, some coexisting chemicals may affect the adsorption efficiencies of analytes if competitive adsorption occurs between the tested targets and potential interferential chemicals, such as inorganic ions and organic materials. Consequently, the effects of several inorganic ions and organic materials were carefully studied. In these experiments, standard solutions of 200 ng L-1 of the PAHs were used, and 13 inorganic ions (namely As3+, Ca2+, Cd2+, Co2+, Cr3+, Cu2+, Fe3+, Mg2+, Mn2+, Ni2+, Zn2+, Pb2+, and Se2+) and 11 organic chemicals (namely chloroform, dichloromethane, carbon tetrachloride, dichlorvos, fenitrothion, malathion, mevinphos, fenthion, parathion, cypermethrin, and pirimicarb) at concentrations of 100 μg mL-1 were introduced. The results are summarized in Figure 5. With the tolerance limits defined as the largest concentrations of coexisting ions causing less than 15% signal variation, no significant interferences were observed.

(a) Interferences owing to the coexistence of different inorganic ions at a concentration of 100 μg mL-1. (b) Interferences owing to the coexistence of different organic materials at a concentration of 100 μg mL-1.

3.4 Analytical performance

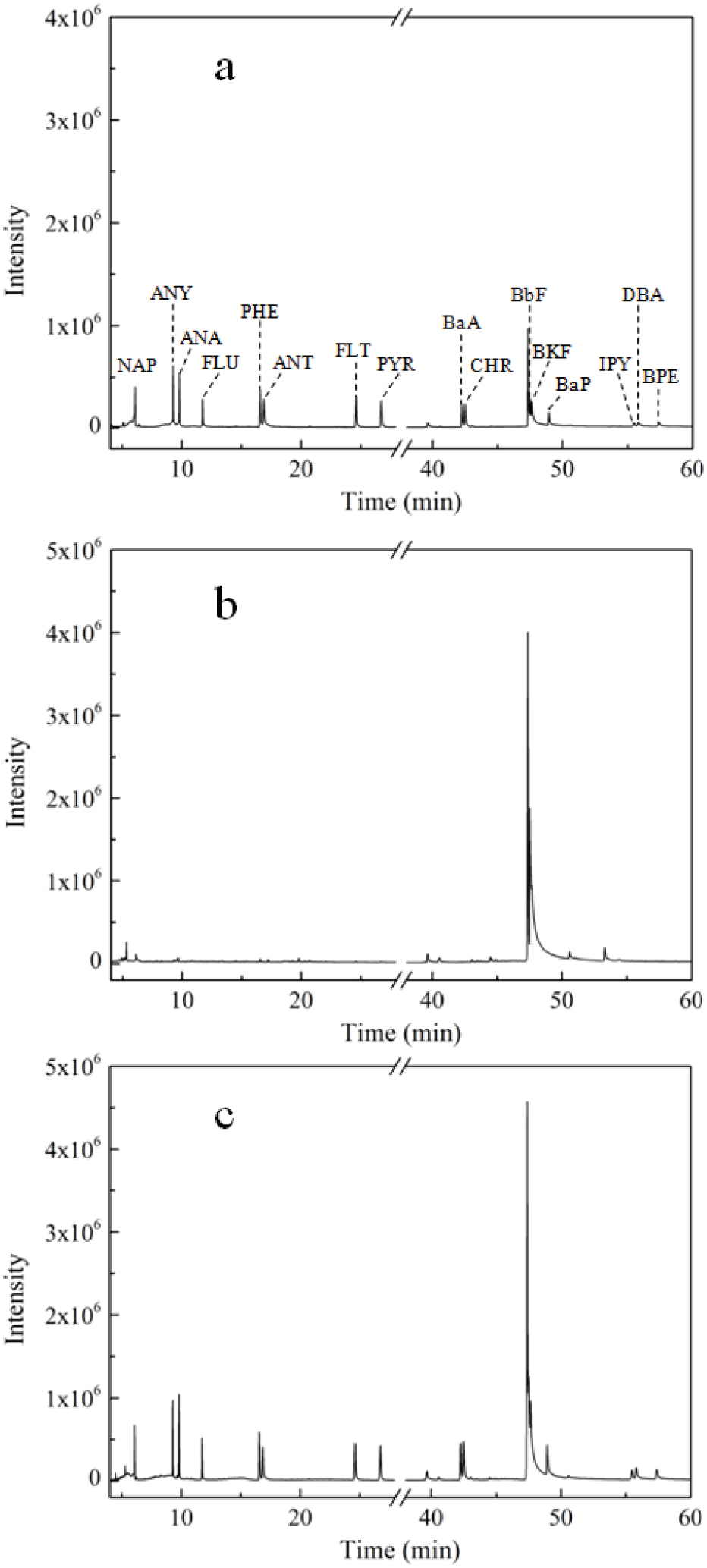

Analysis of PAHs by GC-MS was accomplished in the SIM mode based on the use of one target as quantification ion and two confirmation ions. PAHs were recognized according to their retention times, target and confirmation ions. The retention time, diagnostic ions and quantification ion for each analyte are presented in Table1. Representative selected ion chromatograms of non-spiked and spiked water samples are shown in Figure 6. The method showed no interfering background signal and therefore excellent selectivity for PAHs in the presence of other sample constituents.

GC-MS chromatograms under SIM mode of PAHs in (a) PAHs standard solution, (b) blank water sample and (c) spiked water sample.

The analytical performance of the PAHs obtained using GC-MS were evaluated under optimal experimental conditions. The linearity, regression, and linear ranges of the PAHs compounds are presented in Table 1. The linear coefficient (R2) was better than 0.99. The determined limits of detection (LODs), as defined as the lowest analyte concentration that yielded a signal of three times the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N), ranged from 10 to 30 ng L-1. Considering that the Chinese Ministry of Health has established maximum residue limits (MRLs) of PAHs in drinking water at a value of 2 μg L-1 (GB 5749-2006, Chinese national standard), this method meets requirements for the determination of PAHs in water samples.

The applicability of the proposed method was first used to analyze 15 real samples from river, lake, and sea water to allow comparison with standard methods. The river and lake water samples were concentrated directly after filtering through a 0.22 μm membrane filter. However, as mentioned earlier, GO aggregation occurred immediately upon GO addition because of the high salt content of sea water, which decreased the extraction efficiency. Therefore, with this method, sea water should be diluted before analysis, and no additional NaCl is needed to trigger GO aggregation in this case. However, the PAH contents in the water samples collected in Haikou were below the limits of quantitation (LOQs) of both the proposed and standard methods (data not shown). Therefore, river and sea water samples were chosen to further validate the accuracy of the proposed method via the evaluation of the recoveries of the spiked PAHs, because no certified PAH values in these samples are available. The results are summarized in Table 2. Satisfactory spike recoveries were measured in the ranges of 80–111% and 80–107% for real spiked water samples at 100 and 500 ng L-1, confirming the suitability of the proposed method for PAH analysis.

Analytical performances of the developed method.

| PAHs | Added, 100 ng L-1 | Added, 500 ng L-1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Found[a] (ng L1) | Recovery[a] (%) | Found[b] (ng L-1) | Recovery[b] (%) | Found[a] (ng L-1) | Recovery[a] (%) | Found[b] (ng L-1) | Recovery[b] (%) | |

| NAP | 90.4±4.8 | 90 | 106.1±7.9 | 106 | 535.2±24.7 | 107 | 451.0±34.8 | 90 |

| ANY | 103.2±7.0 | 103 | 102.8±3.6 | 103 | 440.8±37.3 | 88 | 511.2±13.2 | 102 |

| ANA | 81.1±8.0 | 81 | 103.3±6.0 | 103 | 470.1±54.7 | 94 | 466.8±19.0 | 93 |

| FLU | 103.1±6.9 | 103 | 91.4±3.3 | 91 | 448.3±40.3 | 90 | 462.2±42.4 | 92 |

| PHE | 110.4±1.8 | 110 | 89.5±5.7 | 89 | 471.8±14.4 | 94 | 453.8±25.2 | 91 |

| ANT | 110.3±8.2 | 110 | 88.8±3.0 | 89 | 441.7±19.4 | 88 | 511.0±16.7 | 102 |

| FLT | 93.7±6.5 | 94 | 94.2±4.3 | 94 | 423.0±35.9 | 85 | 462.2±19.3 | 92 |

| PYR | 81.7±5.9 | 82 | 88.8±4.9 | 89 | 438.3±16.9 | 88 | 437.7±35.2 | 88 |

| BaA | 80.1±6.0 | 80 | 96.7±7.3 | 97 | 502.7±20.2 | 101 | 509.0±39.9 | 102 |

| CHR | 84.8±4.6 | 85 | 106.2±2.0 | 106 | 438.6±15.6 | 88 | 406.9±41.1 | 81 |

| BbF | 88.3±6.9 | 88 | 109.0±2.0 | 109 | 479.3±26.4 | 96 | 457.8±22.1 | 92 |

| BKF | 110.3±2.0 | 110 | 110.7±7.3 | 111 | 495.8±37.0 | 99 | 514.0±25.5 | 103 |

| BaP | 95.2±4.0 | 95 | 89.2±5.5 | 89 | 429.0±36.1 | 86 | 443.2±23.4 | 89 |

| IPY | 87.9±3.4 | 88 | 84.6±4.4 | 85 | 470.2±35.6 | 94 | 533.7±37.2 | 107 |

| DBA | 99.3±4.7 | 99 | 100.3±8.3 | 100 | 452.8±12.6 | 91 | 474.4±25.9 | 95 |

| BPE | 86.7±6.5 | 87 | 106.9±5.9 | 107 | 489.8±26.9 | 98 | 401.3±14.6 | 80 |

Comparisons of PAH analysis by the proposed and standard methods are summarized in Table 3. Extraction and separation by the aggregation of GO using NaCl as the electrolyte solution coupled to GC-MS detection is friendlier to the environment, simpler in operation, and enhanced in both sample throughput and costeffectiveness.

Comparison of the features of the proposed method and the standard methods.

| pretreated method | determined instrument | organic reagents for pretreatment | organic reagents for determination | enrichment coefficient | LODs (ng L-1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GB/T 26411-2010 | solid phase extraction | GC-MS | methylene chloride, 13 mL; methanol, 1.5 mL; actone, 1.5 mL | hexane, 0.5 mL | 2000 | 1-2 |

| EPA method 610 | Liquid-liquid extraction | HPLC-UVD | methylene chloride, 150 mL | acetonitrile, 1 mL | 500 | 13-2300 |

| [15] | multi-walled carbon nanotubes SPE | GC-MS | 25 mL n-hexane, 10 mL methanol | hexane, 1 mL | 500 | 2.0-8.5 |

| [18] | molecularly imprinted SPE | GC-MS | 2.0 mL methanol/H2O (1:9, v/v) ;10 mL DCM/acetic acid (9:1, v/v) | 0.5 mL DCM/acetic acid (9:1, v/v) | 60 | 5.2-12.6 |

| this method | adsorption/aggregation | GC-MS | - | hexane, 1.0 mL | 50 | 10-30 |

4 Conclusions

In this work, GO was successfully applied for the preconcentration/separation of PAHs from water samples through aggregation by the addition of NaCl. The method is free of organic reagents in the pretreatment procedure and uses only 1 mL hexane for sample introduction in GC-MS. The proposed method is environmentally friendly and demonstrates great applicability for the green analysis of PAH contents in surface waters.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded in part by the National Science and Technology Major Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (Grant No.16YFD0201203), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21467008), the International Cooperation Project of the Ministry of Agriculture (No. ZYLH2018010402), and the Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund for Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences (No. 1630082018001, 1630082017005).

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Rocha F.R.P., Nobrega J.A., Filho O.F., Flow analysis strategies to greener analytical chemistry. An overview, Green Chemistry, 2001, 3, 216-20.10.1039/b103187mSearch in Google Scholar

[2] Keith L.H., Gron L.U., Young J.L., Green Analytical Methodologies, Chemical Reviews, 2007, 107, 2695-708.10.1021/cr068359eSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Ibrahim Ahmed S.A., Al-Farawati R., Hawas U., Shaban Y., Recent Microextraction Techniques for Determination and Chemical Speciation of Selenium, Open Chemistry, 2017, 15, 103-122.10.1515/chem-2017-0013Search in Google Scholar

[4] Keyte I.J., Harrison R.M., Lammel G., Chemical reactivity and long-range transport potential of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons - a review, Chemical Society Reviews, 2013, 42, 9333-91.10.1039/c3cs60147aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] El-Amin Bashir M., El-Maradny A., El-Sherbiny M., Mohammed Orif Rasiq K. T., Bio-concentration of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the grey Mangrove (Avicennia marina) along eastern coast of the Red Sea, Open Chemistry, 2017, 15, 344-351.10.1515/chem-2017-0038Search in Google Scholar

[6] Siemers A.-K., Mänz J.S., Palm W.-U., Ruck W.K., Development and application of a simultaneous SPE-method for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), alkylated PAHs, heterocyclic PAHs (NSO-HET) and phenols in aqueous samples from German Rivers and the North Sea, Chemosphere, 2015, 122, 105-14.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.11.022Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Margoum C., Guillemain C., Yang X., Coquery M., Stir bar sorptive extraction coupled to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry for the determination of pesticides in water samples: Method validation and measurement uncertainty, Talanta, 2013, 116, 1-7.10.1016/j.talanta.2013.04.066Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Fisichella M., Odoardi S., Strano-Rossi S., High-throughput dispersive liquid/liquid microextraction (DLLME) method for the rapid determination of drugs of abuse, benzodiazepines and other psychotropic medications in blood samples by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and application to forensic cases, Microchemical Journal, 2015, 123, 33-41.10.1016/j.microc.2015.05.009Search in Google Scholar

[9] Takáčová A., Smolinská M., Ryba J., Mackuľak T., Jokrllová J., Hronec P., Čík G., Biodegradation of Benzo[a]Pyrene through the use of algae, Open Chemistry, 2014, 12, 1133-43.10.2478/s11532-014-0567-6Search in Google Scholar

[10] Smoker M., Tran K., Smith R.E., Determination of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Shrimp, Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2010, 58, 12101-4.10.1021/jf1029652Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Wen Y., Chen L., Li J., Liu D., Chen L., Recent advances in solid-phase sorbents for sample preparation prior to chromatographic analysis, TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2014, 59, 26-41.10.1016/j.trac.2014.03.011Search in Google Scholar

[12] Ma J., Yao Z., Hou L., Lu W., Yang Q., Li J., Chen L., Metal organic frameworks (MOFs) for magnetic solid-phase extraction of pyrazole/pyrrole pesticides in environmental water samples followed by HPLC-DAD determination, Talanta, 2016, 161, 686-92.10.1016/j.talanta.2016.09.035Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Gu H.-X., Hu K., Li D.-W., Long Y.-T., SERS detection of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons using a bare gold nanoparticles coupled film system, Analyst, 2016, 141,4 359-6510.1039/C6AN00319BSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Hawthorne S.B., Jonker M.T.O., van der Heijden S.A., Grabanski C.B., Azzolina N. A., Miller D.J., Measuring Picogram per Liter Concentrations of Freely Dissolved Parent and Alkyl PAHs (PAH-34), Using Passive Sampling with Polyoxymethylene, Analytical Chemistry, 2011,83,6754-61.10.1021/ac201411vSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Ma J., Xiao R., Li J., Yu J., Zhang Y., Chen L., Determination of 16 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in environmental water samples by solid-phase extraction using multi-walled carbon nanotubes as adsorbent coupled with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, Journal of Chromatography A, 2010, 1217, 5462-9.10.1016/j.chroma.2010.06.060Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Roy G., Vuillemin R., Guyomarch J., On-site determination of polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons in seawater by stir bar sorptive extraction (SBSE) and thermal desorption GC–MS, Talanta, 2005, 66, 540-6.10.1016/j.talanta.2004.11.035Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Jariwala D., Sangwan V.K., Lauhon L.J., Marks T.J., Hersam M.C., Carbon nanomaterials for electronics, optoelectronics, photovoltaics, and sensing, Chemical Society Reviews, 2013, 42, 2824-60.10.1039/C2CS35335KSearch in Google Scholar

[18] Song X., Li J., Xu S., Ying R., Ma J., Liao C., Liu D., Yu J., Chen L., Determination of 16 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in seawater using molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction coupled with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, Talanta, 2012, 99, 75-82.10.1016/j.talanta.2012.04.065Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Wen Y., Niu Z., Ma Y., Ma J., Chen L., Graphene oxide-based microspheres for the dispersive solid-phase extraction of non-steroidal estrogens from water samples, Journal of Chromatography A, 2014, 1368, 18-25.10.1016/j.chroma.2014.09.049Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Chen C., Zhou P., Wang N., Ma Y., San H., UV-Assisted Photochemical Synthesis of Reduced Graphene Oxide/ZnO Nanowires Composite for Photoresponse Enhancement in UV Photodetectors, Nanomaterials, 2018, 8, 26.10.3390/nano8010026Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Dreyer D.R., Park S., Bielawski C.W., Ruoff R.S., The chemistry of graphene oxide, Chemical Society Reviews, 2010, 39, 228-40.10.1039/B917103GSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Si Y., Samulski E.T., Synthesis of water soluble graphene, Nano letters, 2008, 8, 1679-82.10.1021/nl080604hSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Li Y., Du Q., Liu T., Sun J., Wang Y., Wu S., Wang Z., Xia Y., Xia L., Methylene blue adsorption on graphene oxide/calcium alginate composites, Carbohydrate Polymers, 2013, 95, 501-7.10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.01.094Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Li Y., Du Q., Liu T., Peng X., Wang J., Sun J., Wang Y., Wu S., Wang Z., Xia Y., Comparative study of methylene blue dye adsorption onto activated carbon, graphene oxide, and carbon nanotubes, Chemical Engineering Research and Design, 2013, 91, 361-8.10.1016/j.cherd.2012.07.007Search in Google Scholar

[25] Ning F., Peng H., Li J., Chen L., Xiong H., Molecularly Imprinted Polymer on Magnetic Graphene Oxide for Fast and Selective Extraction of 17β-Estradiol, Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2014, 62, 7436-43.10.1021/jf501845wSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Li L., Wang Z., Zhang S., Wang M., Directly-thiolated graphene based organic solvent-free cloud point extraction-like method for enrichment and speciation of mercury by HPLC-ICP-MS, Microchemical Journal, 2017, 132, 299-307.10.1016/j.microc.2017.02.011Search in Google Scholar

[27] Mo J., Zhou L., Li X., Li Q., Wang L., Wang Z., On-line separation and pre-concentration on a mesoporous silica-grafted graphene oxide adsorbent coupled with solution cathode glow discharge-atomic emission spectrometry for the determination of lead, Microchemical Journal, 2017, 130, 353-9.10.1016/j.microc.2016.10.008Search in Google Scholar

[28] Gao Y., Li Y., Zhang L., Huang H., Hu J., Shah S. M., Su X., Adsorption and removal of tetracycline antibiotics from aqueous solution by graphene oxide, Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 2012, 368, 540-6.10.1016/j.jcis.2011.11.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Wu M., Kempaiah R., Huang P.-J.J., Maheshwari V., Liu J., Adsorption and desorption of DNA on graphene oxide studied by fluorescently labeled oligonucleotides, Langmuir, 2011, 27, 2731-8.10.1021/la1037926Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Xu J., Zheng J., Tian J., Zhu F., Zeng F., Su C., Ouyang G., New materials in solid-phase microextraction, TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2013, 47, 68-83.10.1016/j.trac.2013.02.012Search in Google Scholar

[31] Wang J., Chen Z., Chen B., Adsorption of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons by Graphene and Graphene Oxide Nanosheets, Environmental Science & Technology, 2014, 48, 4817-25.10.1021/es405227uSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Zhao G., Li J., Ren X., Chen C., Wang X., Few-Layered Graphene Oxide Nanosheets As Superior Sorbents for Heavy Metal Ion Pollution Management, Environmental Science & Technology, 2011, 45, 10454-62.10.1021/es203439vSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Yang S.-T., Chang Y., Wang H., Liu G., Chen S., Wang Y., Liu Y., Cao A., Folding/aggregation of graphene oxide and its application in Cu2+ removal, Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 2010, 351, 122-7.10.1016/j.jcis.2010.07.042Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Li D., Müller M. B., Gilje S., Kaner R. B., Wallace G. G., Processable aqueous dispersions of graphene nanosheets, Nature Nanotechnology, 2008,3,101.10.1038/nnano.2007.451Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Chandra V., Kim K.S., Highly selective adsorption of Hg2+ by a polypyrrole-reduced graphene oxide composite, Chemical Communications, 2011, 47, 3942-4.10.1039/c1cc00005eSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Deng D., Jiang X., Yang L., Hou X., Zheng C., Organic Solvent-Free Cloud Point Extraction-like Methodology Using Aggregation of Graphene Oxide, Analytical Chemistry, 2014, 86, 758-65.10.1021/ac403345sSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Mateos R., Vera S., Díez-Pascual A.M., San Andrés M.P., Graphene solid phase extraction (SPE) of synthetic antioxidants in complex food matrices, Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 2017, 62, 223-30.10.1016/j.jfca.2017.07.006Search in Google Scholar

[38] Xiao R., Zhang X., Zhang X., Niu J., Lu M., Liu X., Cai Z., Analysis of flavors and fragrances by HPLC with Fe3O4@GO magnetic nanocomposite as the adsorbent, Talanta, 2017, 166, 262-7.10.1016/j.talanta.2017.01.065Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Determination of 16 polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons in seawater by GC-MS. Beijing: Standards Press of China, 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[40] White B., Banerjee S., O’Brien S., Turro N.J., Herman I.P., Zeta-Potential Measurements of Surfactant-Wrapped Individual Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes, Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 2007, 111, 13684-90.10.1021/jp070853eSearch in Google Scholar

© 2018 Bingjun Han et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The effect of CuO modification for a TiO2 nanotube confined CeO2 catalyst on the catalytic combustion of butane

- The preparation and antibacterial activity of cellulose/ZnO composite: a review

- Linde Type A and nano magnetite/NaA zeolites: cytotoxicity and doxorubicin loading efficiency

- Performance and thermal decomposition analysis of foaming agent NPL-10 for use in heavy oil recovery by steam injection

- Spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, UV, 1H and 13C NMR) insights, electronic profiling and DFT computations on ({(E)-[3-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-1-phenylpropylidene] amino}oxy)(4-nitrophenyl)methanone, an imidazole-bearing anti-Candida agent

- A Simplistic Preliminary Assessment of Ginstling-Brounstein Model for Solid Spherical Particles in the Context of a Diffusion-Controlled Synthesis

- M-Polynomials And Topological Indices Of Zigzag And Rhombic Benzenoid Systems

- Photochemical Transformation of some 3-benzyloxy-2-(benzo[b]thiophen-2-yl)-4Hchromen-4-ones: A Remote Substituent Effect

- Dynamic Changes of Secondary Metabolites and Antioxidant Activity of Ligustrum lucidum During Fruit Growth

- Studies on the flammability of polypropylene/ammonium polyphosphate and montmorillonite by using the cone calorimeter test

- DSC, FT-IR, NIR, NIR-PCA and NIR-ANOVA for determination of chemical stability of diuretic drugs: impact of excipients

- Antioxidant and Hepatoprotective Effects of Methanolic Extracts of Zilla spinosa and Hammada elegans Against Carbon Tetrachlorideinduced Hepatotoxicity in Rats

- Prunus cerasifera Ehrh. fabricated ZnO nano falcates and its photocatalytic and dose dependent in vitro bio-activity

- Organic biocides hosted in layered double hydroxides: enhancing antimicrobial activity

- Experimental study on the regulation of the cholinergic pathway in renal macrophages by microRNA-132 to alleviate inflammatory response

- Synthesis, characterization, in-vitro antimicrobial properties, molecular docking and DFT studies of 3-{(E)-[(4,6-dimethylpyrimidin-2-yl)imino]methyl} naphthalen-2-ol and Heteroleptic Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Zn(II) complexes

- M-Polynomials and Topological Indices of Dominating David Derived Networks

- Human Health Risk Assessment of Trace Metals in Surface Water Due to Leachate from the Municipal Dumpsite by Pollution Index: A Case Study from Ndawuse River, Abuja, Nigeria

- Analysis of Bowel Diseases from Blood Serum by Autofluorescence and Atomic Force Microscopy Techniques

- Hydrographic parameters and distribution of dissolved Cu, Ni, Zn and nutrients near Jeddah desalination plant

- Relationships between diatoms and environmental variables in industrial water biotopes of Trzuskawica S.A. (Poland)

- Optimum Conversion of Major Ginsenoside Rb1 to Minor Ginsenoside Rg3(S) by Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Acid Hydrolysis Treatment

- Antioxidant, Anti-microbial Properties and Chemical Composition of Cumin Essential Oils Extracted by Three Methods

- Regulatory mechanism of ulinastatin on autophagy of macrophages and renal tubular epithelial cells

- Investigation of the sustained-release mechanism of hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose skeleton type Acipimox tablets

- Bio-accumulation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Grey Mangrove (Avicennia marina) along Arabian Gulf, Saudi Coast

- Dynamic Change of Secondary Metabolites and spectrum-effect relationship of Malus halliana Koehne flowers during blooming

- Lipids constituents from Gardenia aqualla Stapf & Hutch

- Effect of using microwaves for catalysts preparation on the catalytic acetalization of glycerol with furfural to obtain fuel additives

- Effect of Humic Acid on the Degradation of Methylene Blue by Peroxymonosulfate

- Serum containing drugs of Gua Lou Xie Bai decoction (GLXB-D) can inhibit TGF-β1-Induced Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in A549 Cells

- Antiulcer Activity of Different Extracts of Anvillea garcinii and Isolation of Two New Secondary Metabolites

- Analysis of Metabolites in Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz Dry Red Wines from Shanxi by 1H NMR Spectroscopy Combined with Pattern Recognition Analysis

- Can water temperature impact litter decomposition under pollution of copper and zinc mixture

- Released from ZrO2/SiO2 coating resveratrol inhibits senescence and oxidative stress of human adipose-derived stem cells (ASC)

- Validated thin-layer chromatographic method for alternative and simultaneous determination of two anti-gout agents in their fixed dose combinations

- Fast removal of pollutants from vehicle emissions during cold-start stage

- Review Article

- Catalytic activities of heterogeneous catalysts obtained by copolymerization of metal-containing 2-(acetoacetoxy)ethyl methacrylate

- Antibiotic Residue in the Aquatic Environment: Status in Africa

- Regular Articles

- Mercury fractionation in gypsum using temperature desorption and mass spectrometric detection

- Phytosynthetic Ag doped ZnO nanoparticles: Semiconducting green remediators

- Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Induced by SMAD4 Activation in Invasive Growth Hormone-Secreting Adenomas

- Physicochemical properties of stabilized sewage sludge admixtures by modified steel slag

- In Vitro Cytotoxic and Antiproliferative Activity of Cydonia oblonga flower petals, leaf and fruit pellet ethanolic extracts. Docking simulation of the active flavonoids on anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2

- Synthesis and Characterization of Pd exchanged MMT Clay for Mizoroki-Heck Reaction

- A new selective, and sensitive method for the determination of lixivaptan, a vasopressin 2 (V2)-receptor antagonist, in mouse plasma and its application in a pharmacokinetic study

- Anti-EGFL7 antibodies inhibit rat prolactinoma MMQ cells proliferation and PRL secretion

- Density functional theory calculations, vibration spectral analysis and molecular docking of the antimicrobial agent 6-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-ylmethyl)-5-ethyl-2-{[2-(morpholin-4-yl)ethyl] sulfanyl}pyrimidin-4(3H)-one

- Effect of Nano Zeolite on the Transformation of Cadmium Speciation and Its Uptake by Tobacco in Cadmium-contaminated Soil

- Effects and Mechanisms of Jinniu Capsule on Methamphetamine-Induced Conditioned Place Preference in Rats

- Calculating the Degree-based Topological Indices of Dendrimers

- Efficient optimization and mineralization of UV absorbers: A comparative investigation with Fenton and UV/H2O2

- Metabolites of Tryptophane and Phenylalanine as Markers of Small Bowel Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

- Adsorption and determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water through the aggregation of graphene oxide

- The role of NR2C2 in the prolactinomas

- Chromium removal from industrial wastewater using Phyllostachys pubescens biomass loaded Cu-S nanospheres

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Preparation of Calcium Fluoride using Phosphogypsum by Orthogonal Experiment

- The mechanism of antibacterial activity of corylifolinin against three clinical bacteria from Psoralen corylifolia L

- 2-formyl-3,6-bis(hydroxymethyl)phenyl benzoate in Electrochemical Dry Cell

- Electro-photocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin using calcium titanate

- Effect of Malus halliana Koehne Polysaccharides on Functional Constipation

- Structural Properties and Nonlinear Optical Responses of Halogenated Compounds: A DFT Investigation on Molecular Modelling

- DMFDMA catalyzed synthesis of 2-((Dimethylamino)methylene)-3,4-dihydro-9-arylacridin-1(2H)-ones and their derivatives: in-vitro antifungal, antibacterial and antioxidant evaluations

- Production of Methanol as a Fuel Energy from CO2 Present in Polluted Seawater - A Photocatalytic Outlook

- Study of different extraction methods on finger print and fatty acid of raw beef fat using fourier transform infrared and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- Determination of trace fluoroquinolones in water solutions and in medicinal preparations by conventional and synchronous fluorescence spectrometry

- Extraction and determination of flavonoids in Carthamus tinctorius

- Therapeutic Application of Zinc and Vanadium Complexes against Diabetes Mellitus a Coronary Disease: A review

- Study of calcined eggshell as potential catalyst for biodiesel formation using used cooking oil

- Manganese oxalates - structure-based Insights

- Topological Indices of H-Naphtalenic Nanosheet

- Long-Term Dissolution of Glass Fibers in Water Described by Dissolving Cylinder Zero-Order Kinetic Model: Mass Loss and Radius Reduction

- Topological study of the para-line graphs of certain pentacene via topological indices

- A brief insight into the prediction of water vapor transmissibility in highly impermeable hybrid nanocomposites based on bromobutyl/epichlorohydrin rubber blends

- Comparative sulfite assay by voltammetry using Pt electrodes, photometry and titrimetry: Application to cider, vinegar and sugar analysis

- MicroRNA delivery mediated by PEGylated polyethylenimine for prostate cancer therapy

- Reversible Fluorescent Turn-on Sensors for Fe3+ based on a Receptor Composed of Tri-oxygen Atoms of Amide Groups in Water

- Sonocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in aqueous solution using Fe-doped TiO2 nanoparticles under mechanical agitation

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Production and Analysis of Recycled Ammonium Perrhenate from CMSX-4 superalloys

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- New phosphorus biofertilizers from renewable raw materials in the aspect of cadmium and lead contents in soil and plants

- Survey of content of cadmium, calcium, chromium, copper, iron, lead, magnesium, manganese, mercury, sodium and zinc in chamomile and green tea leaves by electrothermal or flame atomizer atomic absorption spectrometry

- Biogas digestate – benefits and risks for soil fertility and crop quality – an evaluation of grain maize response

- A numerical analysis of heat transfer in a cross-current heat exchanger with controlled and newly designed air flows

- Freshwater green macroalgae as a biosorbent of Cr(III) ions

- The main influencing factors of soil mechanical characteristics of the gravity erosion environment in the dry-hot valley of Jinsha river

- Free amino acids in Viola tricolor in relation to different habitat conditions

- The influence of filler amount on selected properties of new experimental resin dental composite

- Effect of poultry wastewater irrigation on nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon contents in farmland soil

- Response of spring wheat to NPK and S fertilization. The content and uptake of macronutrients and the value of ionic ratios

- The Effect of Macroalgal Extracts and Near Infrared Radiation on Germination of Soybean Seedlings: Preliminary Research Results

- Content of Zn, Cd and Pb in purple moor-grass in soils heavily contaminated with heavy metals around a zinc and lead ore tailing landfill

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Synthesis of (±)-3,4-dimethoxybenzyl-4-methyloctanoate as a novel internal standard for capsinoid determination by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS(QTOF)

- Repellent activity of monoterpenoid esters with neurotransmitter amino acids against yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti

- Effect of Flammulina velutipes (golden needle mushroom, eno-kitake) polysaccharides on constipation

- Bioassay-directed fractionation of a blood coagulation factor Xa inhibitor, betulinic acid from Lycopus lucidus

- Antifungal and repellent activities of the essential oils from three aromatic herbs from western Himalaya

- Chemical composition and microbiological evaluation of essential oil from Hyssopus officinalis L. with white and pink flowers

- Bioassay-guided isolation and identification of Aedes aegypti larvicidal and biting deterrent compounds from Veratrum lobelianum

- α-Terpineol, a natural monoterpene: A review of its biological properties

- Utility of essential oils for development of host-based lures for Xyleborus glabratus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae), vector of laurel wilt

- Phenolic composition and antioxidant potential of different organs of Kazakh Crataegus almaatensis Pojark: A comparison with the European Crataegus oxyacantha L. flowers

- Isolation of eudesmane type sesquiterpene ketone from Prangos heyniae H.Duman & M.F.Watson essential oil and mosquitocidal activity of the essential oils

- Comparative analysis of the polyphenols profiles and the antioxidant and cytotoxicity properties of various blue honeysuckle varieties

- Special Issue on ICCESEN 2017

- Modelling world energy security data from multinomial distribution by generalized linear model under different cumulative link functions

- Pine Cone and Boron Compounds Effect as Reinforcement on Mechanical and Flammability Properties of Polyester Composites

- Artificial Neural Network Modelling for Prediction of SNR Effected by Probe Properties on Ultrasonic Inspection of Austenitic Stainless Steel Weldments

- Calculation and 3D analyses of ERR in the band crack front contained in a rectangular plate made of multilayered material

- Improvement of fuel properties of biodiesel with bioadditive ethyl levulinate

- Properties of AlSi9Cu3 metal matrix micro and nano composites produced via stir casting

- Investigation of Antibacterial Properties of Ag Doped TiO2 Nanofibers Prepared by Electrospinning Process

- Modeling of Total Phenolic contents in Various Tea samples by Experimental Design Methods

- Nickel doping effect on the structural and optical properties of indium sulfide thin films by SILAR

- The effect mechanism of Ginnalin A as a homeopathic agent on various cancer cell lines

- Excitation functions of proton induced reactions of some radioisotopes used in medicine

- Oxide ionic conductivity and microstructures of Pr and Sm co-doped CeO2-based systems

- Rapid Synthesis of Metallic Reinforced in Situ Intermetallic Composites in Ti-Al-Nb System via Resistive Sintering

- Oxidation Behavior of NiCr/YSZ Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs)

- Clustering Analysis of Normal Strength Concretes Produced with Different Aggregate Types

- Magnetic Nano-Sized Solid Acid Catalyst Bearing Sulfonic Acid Groups for Biodiesel Synthesis

- The biological activities of Arabis alpina L. subsp. brevifolia (DC.) Cullen against food pathogens

- Humidity properties of Schiff base polymers

- Free Vibration Analysis of Fiber Metal Laminated Straight Beam

- Comparative study of in vitro antioxidant, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase activity of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) collected during different growth stages

- Isothermal Oxidation Behavior of Gadolinium Zirconate (Gd2Zr2O7) Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs) produced by Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition (EB-PVD) technique

- Optimization of Adsorption Parameters for Ultra-Fine Calcite Using a Box-Behnken Experimental Design

- The Microstructural Investigation of Vermiculite-Infiltrated Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition Thermal Barrier Coatings

- Modelling Porosity Permeability of Ceramic Tiles using Fuzzy Taguchi Method

- Experimental and theoretical study of a novel naphthoquinone Schiff base

- Physicochemical properties of heat treated sille stone for ceramic industry

- Sand Dune Characterization for Preparing Metallurgical Grade Silicon

- Catalytic Applications of Large Pore Sulfonic Acid-Functionalized SBA-15 Mesoporous Silica for Esterification

- One-photon Absorption Characterizations, Dipole Polarizabilities and Second Hyperpolarizabilities of Chlorophyll a and Crocin

- The Optical and Crystallite Characterization of Bilayer TiO2 Films Coated on Different ITO layers

- Topical Issue on Bond Activation

- Metal-mediated reactions towards the synthesis of a novel deaminolysed bisurea, dicarbamolyamine

- The structure of ortho-(trifluoromethyl)phenol in comparison to its homologues – A combined experimental and theoretical study

- Heterogeneous catalysis with encapsulated haem and other synthetic porphyrins: Harnessing the power of porphyrins for oxidation reactions

- Recent Advances on Mechanistic Studies on C–H Activation Catalyzed by Base Metals

- Reactions of the organoplatinum complex [Pt(cod) (neoSi)Cl] (neoSi = trimethylsilylmethyl) with the non-coordinating anions SbF6– and BPh4–

- Erratum

- Investigation on Two Compounds of O, O’-dithiophosphate Derivatives as Corrosion Inhibitors for Q235 Steel in Hydrochloric Acid Solution

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The effect of CuO modification for a TiO2 nanotube confined CeO2 catalyst on the catalytic combustion of butane

- The preparation and antibacterial activity of cellulose/ZnO composite: a review

- Linde Type A and nano magnetite/NaA zeolites: cytotoxicity and doxorubicin loading efficiency

- Performance and thermal decomposition analysis of foaming agent NPL-10 for use in heavy oil recovery by steam injection

- Spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, UV, 1H and 13C NMR) insights, electronic profiling and DFT computations on ({(E)-[3-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-1-phenylpropylidene] amino}oxy)(4-nitrophenyl)methanone, an imidazole-bearing anti-Candida agent

- A Simplistic Preliminary Assessment of Ginstling-Brounstein Model for Solid Spherical Particles in the Context of a Diffusion-Controlled Synthesis

- M-Polynomials And Topological Indices Of Zigzag And Rhombic Benzenoid Systems

- Photochemical Transformation of some 3-benzyloxy-2-(benzo[b]thiophen-2-yl)-4Hchromen-4-ones: A Remote Substituent Effect

- Dynamic Changes of Secondary Metabolites and Antioxidant Activity of Ligustrum lucidum During Fruit Growth

- Studies on the flammability of polypropylene/ammonium polyphosphate and montmorillonite by using the cone calorimeter test

- DSC, FT-IR, NIR, NIR-PCA and NIR-ANOVA for determination of chemical stability of diuretic drugs: impact of excipients

- Antioxidant and Hepatoprotective Effects of Methanolic Extracts of Zilla spinosa and Hammada elegans Against Carbon Tetrachlorideinduced Hepatotoxicity in Rats

- Prunus cerasifera Ehrh. fabricated ZnO nano falcates and its photocatalytic and dose dependent in vitro bio-activity

- Organic biocides hosted in layered double hydroxides: enhancing antimicrobial activity

- Experimental study on the regulation of the cholinergic pathway in renal macrophages by microRNA-132 to alleviate inflammatory response

- Synthesis, characterization, in-vitro antimicrobial properties, molecular docking and DFT studies of 3-{(E)-[(4,6-dimethylpyrimidin-2-yl)imino]methyl} naphthalen-2-ol and Heteroleptic Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Zn(II) complexes

- M-Polynomials and Topological Indices of Dominating David Derived Networks

- Human Health Risk Assessment of Trace Metals in Surface Water Due to Leachate from the Municipal Dumpsite by Pollution Index: A Case Study from Ndawuse River, Abuja, Nigeria

- Analysis of Bowel Diseases from Blood Serum by Autofluorescence and Atomic Force Microscopy Techniques

- Hydrographic parameters and distribution of dissolved Cu, Ni, Zn and nutrients near Jeddah desalination plant

- Relationships between diatoms and environmental variables in industrial water biotopes of Trzuskawica S.A. (Poland)

- Optimum Conversion of Major Ginsenoside Rb1 to Minor Ginsenoside Rg3(S) by Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Acid Hydrolysis Treatment

- Antioxidant, Anti-microbial Properties and Chemical Composition of Cumin Essential Oils Extracted by Three Methods

- Regulatory mechanism of ulinastatin on autophagy of macrophages and renal tubular epithelial cells

- Investigation of the sustained-release mechanism of hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose skeleton type Acipimox tablets

- Bio-accumulation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Grey Mangrove (Avicennia marina) along Arabian Gulf, Saudi Coast

- Dynamic Change of Secondary Metabolites and spectrum-effect relationship of Malus halliana Koehne flowers during blooming

- Lipids constituents from Gardenia aqualla Stapf & Hutch

- Effect of using microwaves for catalysts preparation on the catalytic acetalization of glycerol with furfural to obtain fuel additives

- Effect of Humic Acid on the Degradation of Methylene Blue by Peroxymonosulfate

- Serum containing drugs of Gua Lou Xie Bai decoction (GLXB-D) can inhibit TGF-β1-Induced Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in A549 Cells

- Antiulcer Activity of Different Extracts of Anvillea garcinii and Isolation of Two New Secondary Metabolites

- Analysis of Metabolites in Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz Dry Red Wines from Shanxi by 1H NMR Spectroscopy Combined with Pattern Recognition Analysis

- Can water temperature impact litter decomposition under pollution of copper and zinc mixture

- Released from ZrO2/SiO2 coating resveratrol inhibits senescence and oxidative stress of human adipose-derived stem cells (ASC)

- Validated thin-layer chromatographic method for alternative and simultaneous determination of two anti-gout agents in their fixed dose combinations

- Fast removal of pollutants from vehicle emissions during cold-start stage

- Review Article

- Catalytic activities of heterogeneous catalysts obtained by copolymerization of metal-containing 2-(acetoacetoxy)ethyl methacrylate

- Antibiotic Residue in the Aquatic Environment: Status in Africa

- Regular Articles

- Mercury fractionation in gypsum using temperature desorption and mass spectrometric detection

- Phytosynthetic Ag doped ZnO nanoparticles: Semiconducting green remediators

- Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Induced by SMAD4 Activation in Invasive Growth Hormone-Secreting Adenomas

- Physicochemical properties of stabilized sewage sludge admixtures by modified steel slag

- In Vitro Cytotoxic and Antiproliferative Activity of Cydonia oblonga flower petals, leaf and fruit pellet ethanolic extracts. Docking simulation of the active flavonoids on anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2

- Synthesis and Characterization of Pd exchanged MMT Clay for Mizoroki-Heck Reaction

- A new selective, and sensitive method for the determination of lixivaptan, a vasopressin 2 (V2)-receptor antagonist, in mouse plasma and its application in a pharmacokinetic study

- Anti-EGFL7 antibodies inhibit rat prolactinoma MMQ cells proliferation and PRL secretion

- Density functional theory calculations, vibration spectral analysis and molecular docking of the antimicrobial agent 6-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-ylmethyl)-5-ethyl-2-{[2-(morpholin-4-yl)ethyl] sulfanyl}pyrimidin-4(3H)-one

- Effect of Nano Zeolite on the Transformation of Cadmium Speciation and Its Uptake by Tobacco in Cadmium-contaminated Soil

- Effects and Mechanisms of Jinniu Capsule on Methamphetamine-Induced Conditioned Place Preference in Rats

- Calculating the Degree-based Topological Indices of Dendrimers

- Efficient optimization and mineralization of UV absorbers: A comparative investigation with Fenton and UV/H2O2

- Metabolites of Tryptophane and Phenylalanine as Markers of Small Bowel Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

- Adsorption and determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water through the aggregation of graphene oxide

- The role of NR2C2 in the prolactinomas

- Chromium removal from industrial wastewater using Phyllostachys pubescens biomass loaded Cu-S nanospheres

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Preparation of Calcium Fluoride using Phosphogypsum by Orthogonal Experiment

- The mechanism of antibacterial activity of corylifolinin against three clinical bacteria from Psoralen corylifolia L

- 2-formyl-3,6-bis(hydroxymethyl)phenyl benzoate in Electrochemical Dry Cell

- Electro-photocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin using calcium titanate

- Effect of Malus halliana Koehne Polysaccharides on Functional Constipation

- Structural Properties and Nonlinear Optical Responses of Halogenated Compounds: A DFT Investigation on Molecular Modelling

- DMFDMA catalyzed synthesis of 2-((Dimethylamino)methylene)-3,4-dihydro-9-arylacridin-1(2H)-ones and their derivatives: in-vitro antifungal, antibacterial and antioxidant evaluations

- Production of Methanol as a Fuel Energy from CO2 Present in Polluted Seawater - A Photocatalytic Outlook

- Study of different extraction methods on finger print and fatty acid of raw beef fat using fourier transform infrared and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- Determination of trace fluoroquinolones in water solutions and in medicinal preparations by conventional and synchronous fluorescence spectrometry

- Extraction and determination of flavonoids in Carthamus tinctorius

- Therapeutic Application of Zinc and Vanadium Complexes against Diabetes Mellitus a Coronary Disease: A review

- Study of calcined eggshell as potential catalyst for biodiesel formation using used cooking oil

- Manganese oxalates - structure-based Insights

- Topological Indices of H-Naphtalenic Nanosheet

- Long-Term Dissolution of Glass Fibers in Water Described by Dissolving Cylinder Zero-Order Kinetic Model: Mass Loss and Radius Reduction

- Topological study of the para-line graphs of certain pentacene via topological indices

- A brief insight into the prediction of water vapor transmissibility in highly impermeable hybrid nanocomposites based on bromobutyl/epichlorohydrin rubber blends

- Comparative sulfite assay by voltammetry using Pt electrodes, photometry and titrimetry: Application to cider, vinegar and sugar analysis

- MicroRNA delivery mediated by PEGylated polyethylenimine for prostate cancer therapy

- Reversible Fluorescent Turn-on Sensors for Fe3+ based on a Receptor Composed of Tri-oxygen Atoms of Amide Groups in Water

- Sonocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in aqueous solution using Fe-doped TiO2 nanoparticles under mechanical agitation

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Production and Analysis of Recycled Ammonium Perrhenate from CMSX-4 superalloys

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- New phosphorus biofertilizers from renewable raw materials in the aspect of cadmium and lead contents in soil and plants

- Survey of content of cadmium, calcium, chromium, copper, iron, lead, magnesium, manganese, mercury, sodium and zinc in chamomile and green tea leaves by electrothermal or flame atomizer atomic absorption spectrometry

- Biogas digestate – benefits and risks for soil fertility and crop quality – an evaluation of grain maize response

- A numerical analysis of heat transfer in a cross-current heat exchanger with controlled and newly designed air flows

- Freshwater green macroalgae as a biosorbent of Cr(III) ions

- The main influencing factors of soil mechanical characteristics of the gravity erosion environment in the dry-hot valley of Jinsha river

- Free amino acids in Viola tricolor in relation to different habitat conditions

- The influence of filler amount on selected properties of new experimental resin dental composite

- Effect of poultry wastewater irrigation on nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon contents in farmland soil

- Response of spring wheat to NPK and S fertilization. The content and uptake of macronutrients and the value of ionic ratios

- The Effect of Macroalgal Extracts and Near Infrared Radiation on Germination of Soybean Seedlings: Preliminary Research Results

- Content of Zn, Cd and Pb in purple moor-grass in soils heavily contaminated with heavy metals around a zinc and lead ore tailing landfill

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Synthesis of (±)-3,4-dimethoxybenzyl-4-methyloctanoate as a novel internal standard for capsinoid determination by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS(QTOF)

- Repellent activity of monoterpenoid esters with neurotransmitter amino acids against yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti

- Effect of Flammulina velutipes (golden needle mushroom, eno-kitake) polysaccharides on constipation

- Bioassay-directed fractionation of a blood coagulation factor Xa inhibitor, betulinic acid from Lycopus lucidus

- Antifungal and repellent activities of the essential oils from three aromatic herbs from western Himalaya

- Chemical composition and microbiological evaluation of essential oil from Hyssopus officinalis L. with white and pink flowers

- Bioassay-guided isolation and identification of Aedes aegypti larvicidal and biting deterrent compounds from Veratrum lobelianum

- α-Terpineol, a natural monoterpene: A review of its biological properties

- Utility of essential oils for development of host-based lures for Xyleborus glabratus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae), vector of laurel wilt

- Phenolic composition and antioxidant potential of different organs of Kazakh Crataegus almaatensis Pojark: A comparison with the European Crataegus oxyacantha L. flowers

- Isolation of eudesmane type sesquiterpene ketone from Prangos heyniae H.Duman & M.F.Watson essential oil and mosquitocidal activity of the essential oils

- Comparative analysis of the polyphenols profiles and the antioxidant and cytotoxicity properties of various blue honeysuckle varieties

- Special Issue on ICCESEN 2017

- Modelling world energy security data from multinomial distribution by generalized linear model under different cumulative link functions

- Pine Cone and Boron Compounds Effect as Reinforcement on Mechanical and Flammability Properties of Polyester Composites

- Artificial Neural Network Modelling for Prediction of SNR Effected by Probe Properties on Ultrasonic Inspection of Austenitic Stainless Steel Weldments

- Calculation and 3D analyses of ERR in the band crack front contained in a rectangular plate made of multilayered material

- Improvement of fuel properties of biodiesel with bioadditive ethyl levulinate

- Properties of AlSi9Cu3 metal matrix micro and nano composites produced via stir casting

- Investigation of Antibacterial Properties of Ag Doped TiO2 Nanofibers Prepared by Electrospinning Process

- Modeling of Total Phenolic contents in Various Tea samples by Experimental Design Methods

- Nickel doping effect on the structural and optical properties of indium sulfide thin films by SILAR

- The effect mechanism of Ginnalin A as a homeopathic agent on various cancer cell lines

- Excitation functions of proton induced reactions of some radioisotopes used in medicine

- Oxide ionic conductivity and microstructures of Pr and Sm co-doped CeO2-based systems

- Rapid Synthesis of Metallic Reinforced in Situ Intermetallic Composites in Ti-Al-Nb System via Resistive Sintering

- Oxidation Behavior of NiCr/YSZ Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs)

- Clustering Analysis of Normal Strength Concretes Produced with Different Aggregate Types

- Magnetic Nano-Sized Solid Acid Catalyst Bearing Sulfonic Acid Groups for Biodiesel Synthesis

- The biological activities of Arabis alpina L. subsp. brevifolia (DC.) Cullen against food pathogens

- Humidity properties of Schiff base polymers

- Free Vibration Analysis of Fiber Metal Laminated Straight Beam

- Comparative study of in vitro antioxidant, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase activity of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) collected during different growth stages

- Isothermal Oxidation Behavior of Gadolinium Zirconate (Gd2Zr2O7) Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs) produced by Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition (EB-PVD) technique

- Optimization of Adsorption Parameters for Ultra-Fine Calcite Using a Box-Behnken Experimental Design

- The Microstructural Investigation of Vermiculite-Infiltrated Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition Thermal Barrier Coatings

- Modelling Porosity Permeability of Ceramic Tiles using Fuzzy Taguchi Method

- Experimental and theoretical study of a novel naphthoquinone Schiff base

- Physicochemical properties of heat treated sille stone for ceramic industry

- Sand Dune Characterization for Preparing Metallurgical Grade Silicon

- Catalytic Applications of Large Pore Sulfonic Acid-Functionalized SBA-15 Mesoporous Silica for Esterification

- One-photon Absorption Characterizations, Dipole Polarizabilities and Second Hyperpolarizabilities of Chlorophyll a and Crocin

- The Optical and Crystallite Characterization of Bilayer TiO2 Films Coated on Different ITO layers

- Topical Issue on Bond Activation

- Metal-mediated reactions towards the synthesis of a novel deaminolysed bisurea, dicarbamolyamine

- The structure of ortho-(trifluoromethyl)phenol in comparison to its homologues – A combined experimental and theoretical study

- Heterogeneous catalysis with encapsulated haem and other synthetic porphyrins: Harnessing the power of porphyrins for oxidation reactions

- Recent Advances on Mechanistic Studies on C–H Activation Catalyzed by Base Metals

- Reactions of the organoplatinum complex [Pt(cod) (neoSi)Cl] (neoSi = trimethylsilylmethyl) with the non-coordinating anions SbF6– and BPh4–

- Erratum

- Investigation on Two Compounds of O, O’-dithiophosphate Derivatives as Corrosion Inhibitors for Q235 Steel in Hydrochloric Acid Solution