Abstract

The molecular and crystal structure of commercially-available ortho-(trifluoromethyl)phenol were determined by means of single-crystal X-ray diffractometry (XRD) and represent the first structural characterization of an ortho-substituted (trihalomethyl) phenol. The unexpected presence of a defined hydrate in the solid state was observed.Intermolecular contacts and hydrogen bonding were analyzed. The compound was further characterized by means of multi-nuclear nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (1H, 13C{1H}, 19F) and Fourier-Transform infrared (FT-IR) vibrational spectroscopy. To assess the bonding situation as well as potential reaction sites for reactions with nucleophiles and electrophiles in the compound by means of natural bonding orbital (NBO) analyses, and density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed for the title compound as well as its homologous chlorine, bromine and iodine compounds. As far as possible, experimental data were correlated to DFT data.

Graphical Abstract

1 Introduction

Phenol is among the simplest aromatic alcohols. The Brønstedt acidity of its hydroxyl group (pKa = 9.89) [1] is significantly higher than that of common aliphatic alcohols such as methanol (pKa = 15.5) or ethanol (pKa = 15.9) [2] due to possible resonance stabilization of the corresponding alcoholate anion. As is observed for aliphatic alcohols whose acidity constants can be influenced by means of introducing electron-withdrawing and -donating functional groups on the hydrocarbon scaffold – cf. the pKa values for 2-chloroethanol, 2,2-dichloroethanol and 2,2,2-trichloroethanol of 14.31, 12.89 and 12.24, respectively [2] – the Brønstedt acidity of phenol derivatives can also be fine-tuned by the presence of suitable substituents on the aromatic core [3].In combination with the sterical pretense of the individual substituents or the plain substitution pattern on the aromatic core itself, this changed acidity can increase or decrease the bonding abilities of the respective aromatic alcohol’s hydroxyl group in covalent and dative bonds. Upon variation of the substituents, derivatives of phenol, therefore, may be able to bind to a vast range of non- and (semi-)metals of the main group elements as well as transition metals in molecular and coordination compounds and give rise to interesting bonding patterns. For phenol and phenolate itself, ample structural information about its bonding behaviour – secured and elucidated on grounds of diffraction studies – is apparent in the literature and has shown phenolate to be a remarkably versatile bonding partner. It has been found to act as a strictly monodentate ligand towards main group and transition block elements such as, among others, beryllium [4], aluminium [5], gallium [6,7,8], tin [9], iron [10,11], osmium [12], uranium [13,14,15], neptunium [16], thorium [17], cobalt [18], zirconium [19], samarium [20], molybdenum [21] and tungsten [22,23] as well as a μ2-bridging ligand towards, among others, lithium [24], aluminium [25], gallium [26], thallium [27], tantalum [28], tin [29], iron [30], titanium [31], copper [32] and mercury [33]. In addition, phenolate has further been confirmed to act as a μ3-bridging ligand towards elements such as lithium [34] and zinc [35,36] and even as a μ4-bridging ligand towards sodium [37]. Mixed mono- and bidentate bonding patterns supported by phenolate within one compound have also been reported for compounds based on sodium [38], barium [39], boron [40] and uranium [41]. Furthermore, phenolate has been found capable of acting simultaneously mono-, bi- and tri-dentate within one defined compound [42]. Intriguingly, phenol is also capable to act as a neutral as well as an anionic bonding partner simultaneously within one defined compound towards strontium [43] or titanium [44]. Motivated by this highly diverse chemical behaviour shown by plain phenol and phenolate, a research project aimed at elucidating the rules guiding the occurrence of specific bonding patterns in connection with the acidity as well as the steric pretense of substituents on the aromatic nucleus of phenol was initiated. As a starting point, ortho-(trifluoromethyl) phenol was chosen as it is a commercially-available compound that combines the presence of a strongly electron-withdrawing CF3 group with its bulkiness in close proximity to the hydroxyl group that will act as the main reaction center. It was found that – as of today – structural information for ortho-methyl phenol or other ortho-CX3-substituted (with X = F, Cl, Br and I) phenol derivatives is entirely absent from the literature thus precluding comparative studies with regards to the bonding patterns realized by the title compound and its inherent molecular metrical parameters. The only compounds featuring the meta-(trifluoromethyl)phenol moiety bonded to a heteroatom (i.e. no classical organic ethers) whose molecular and crystal structure have been elucidated on grounds of diffraction studies are found for a dinuclear titanium coordination compound [45] as well as two derivatives of phosphorus(V) [46]. Structural information about para-(trifluoromethyl)phenol-derived compounds with the latter moiety bonded to a heteroatom (i.e. no classical organic esters, ethers or oximes) is also scant and only available for two esters of phosphoric acid [47,48] as well as the symmetric ester of boronic acid [49]. A – purely theoretical – minor study about the hydrogen bonding situation and the conformational behaviour of the title compound has been reported earlier [50]. It is pertinent to note that no structural information at all is available in the literature for any derivatives of trichloromethyl-, tribromomethyl- or triiodomethyl-substituted phenols, regardless of the positioning of the halomethyl group on the aromatic core with respect to the hydroxyl group. A single-crystal X-ray analysis of the title compound was further deemed necessary to assess its chemical composition as a series of condensation and substitution reactions with hydrolytically-unstable substrates – where the title compound was used as one of the starting materials – yielded various hydrolysis products despite rigorously anhydrous working conditions. Preliminary infrared spectra recorded on macroscopic crystals of the title compound hinted on the presence of two different types of hydrogen bonds. Furthermore, due to the scant amount of information present in the literature for ortho-CX3-substituted (with X = F, Cl, Br and I) phenol derivatives in general, DFT calculations were performed to assess the bonding situation in the title compound and its heavier homologues to allow for predictions about potential reaction sites for nucleophiles and electrophiles.

2 Experimental

2.1 Reagents, Instrumentation and Convention

ortho-(Trifluoromethyl)phenol was obtained from Fluorochem Ltd. Crystals suitable for the diffraction studies were obtained upon repeated sublimation of the compound at room temperature.

1H and 13C{1H} NMR spectra were recorded in deuterochloroform on a Bruker Ultrashield 400 Plus spectrometer at 25°C at 400 MHz and 101 MHz, respectively, and are referenced to internal TMS or the solvent residual peak of the deuterated solvent [51].19F NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Ultrashield 400 Plus spectrometer at 25°C at 377 MHz and are referenced to external CFCl3. IR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Tensor 27 spectrometer equipped with a Bruker Platinum ATR unit.

While the calculations have been carried out on pure ortho-(trifluoromethyl)-phenol, all spectroscopic measurements in this study – i.e. each reference to the “title compound” – make use of the actual material that was found to represent a defined hydrate.

2.2 Spectral Data

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, d / ppm): 7.56–7.51 (m, 1H, Har), 7.43–7.39 (m, 1H, Har), 7.03–6.94 (m, 2H, Har), 4.98 (broad, 1H, OH). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, d / ppm): 153.7 (d, J 2.0, Car), 133.6 (s, Car), 127.0 (q, J 5.1, Car), 124.3 (q, J 273, CF3), 120.7 (s, Car), 117.7 (s, Car), 116.7 (q, J 29.9, Car). 19F NMR (377 MHz, CDCl3, d / ppm): –61.1.

FT-IR (neat, n/cm-1): 3342, 3333, 3176, 1616, 1603, 1513, 1461, 1355, 1320, 1254, 1223, 1209, 1170, 1107, 1055, 1034, 949, 861, 836, 789, 754, 647, 597, 549, 530, 470, 355.

2.3 DFT Calculations and NBO Analyses

The structure of the title compound as well as its homologues were optimized with Gaussian 09 [52] on the B3LYP/6-311++ G(2d, p) level of theory with an ultrafine integration grid and very tight convergence criteria as singlet molecules under exclusion of symmetry in point group C1 applying a solvent model for chloroform. The starting geometry was obtained by means of GaussView [53]. Frequency analyses were performed on the optimized structures to ensure that these represent minima on the global electronic potential hypersurface. Calculations of NMR shifts were conducted on the PBE1PBE/6-311++G(2d, p) level of theory using the gauge including atomic orbitals (GIAO) method [54] based on the optimized structures. A solvent model for chloroform was used in this step as well. The analysis and visualization of the molecular orbitals was conducted by the Avogadro [55] as well as the Chemcraft program suite [56]. For iodine, a pseudo-potential implemented in the LanL2DZ basis-set was applied throughout all calculations.

2.4 Crystallography

The diffraction studies on single crystals were performed at 200(2) K on a Bruker Kappa APEX-II CCD diffractometer (MoKα, λ = 0.71073 Å). Structure solutions and refinement procedures were conducted by means of the SHELX program suite [57]. Crystallographic details of the structures are summarized in Table 1. Carbon-bound hydrogen atoms were calculated using the riding-model approximation and were included in the refinement with their UH values set to 1.2Ueq(C). The hydrogen atom of the hydroxyl group was allowed to rotate with a fixed angle around the C–O bond to best fit the experimental electron density (HFIX 147 in the SHELX program suite), with U(H) set to 1.5 Ueq (C). The hydrogen atom of the water molecule was located on a difference Fourier map and was refined freely. Further details are provided in Table 1. Metrical parameters discussed for the crystal structure were obtained using PLATON [58], graphical presentations were prepared using Mercury [59] and ORTEP-III [60]. Crystallographic data of the title compound have been deposited with the Cambridge Structural Database (CCDC: 935348). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge on application to the Director, CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK (Fax: int.code+(1223)336-033; e-mail for inquiry: file-server@ccdc.cam.ac.uk.

Crystallographic data for the structure determination of the title compound.

| Parameter Chemical formula | Value 4 (C7H5F3O) × H2O |

|---|---|

| Mr (g mol-1) | 666.46 |

| Crystal system | Tetragonal |

| Spacegroup | P42/n |

| a (Å) | 19.4264(6) |

| b (Å) | 19.4264(6) |

| c (Å) | 7.6508(2) |

| V (Å3) | 2887.30(19) |

| Z | 4 |

| ρ (g cm-3) | 1.533 |

| μ (mm-1) | 0.155 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.526 × 0.502 × 0.318 |

| θ-Range (°) | 3.32–28.27 |

| Reflections for metrics | 9055 |

| Absorption correction | Numerical |

| Transmission factors | 0.8592–1.0000 |

| Measured reflections | 12980 |

| Independent reflections | 3521 |

| Rint | 0.0156 |

| Mean σ(I)/I | 0.0161 |

| Reflections with I ≥2 σ (I) | 2928 |

| x, y (weighting scheme) | 0.0413, 1.0109 |

| Parameter | 210 |

| Restraints | 0 |

| R(Fobs) | 0.0407 |

| Rw(F2) | 0.1054 |

| S | 1.049 |

| Shift/errormax | 0.001 |

| Max. residual density (e Å-3) | 0.222 |

| Min. residual density (e Å-3) | -0.205 |

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animals use.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Crystal and Molecular Structure Analysis

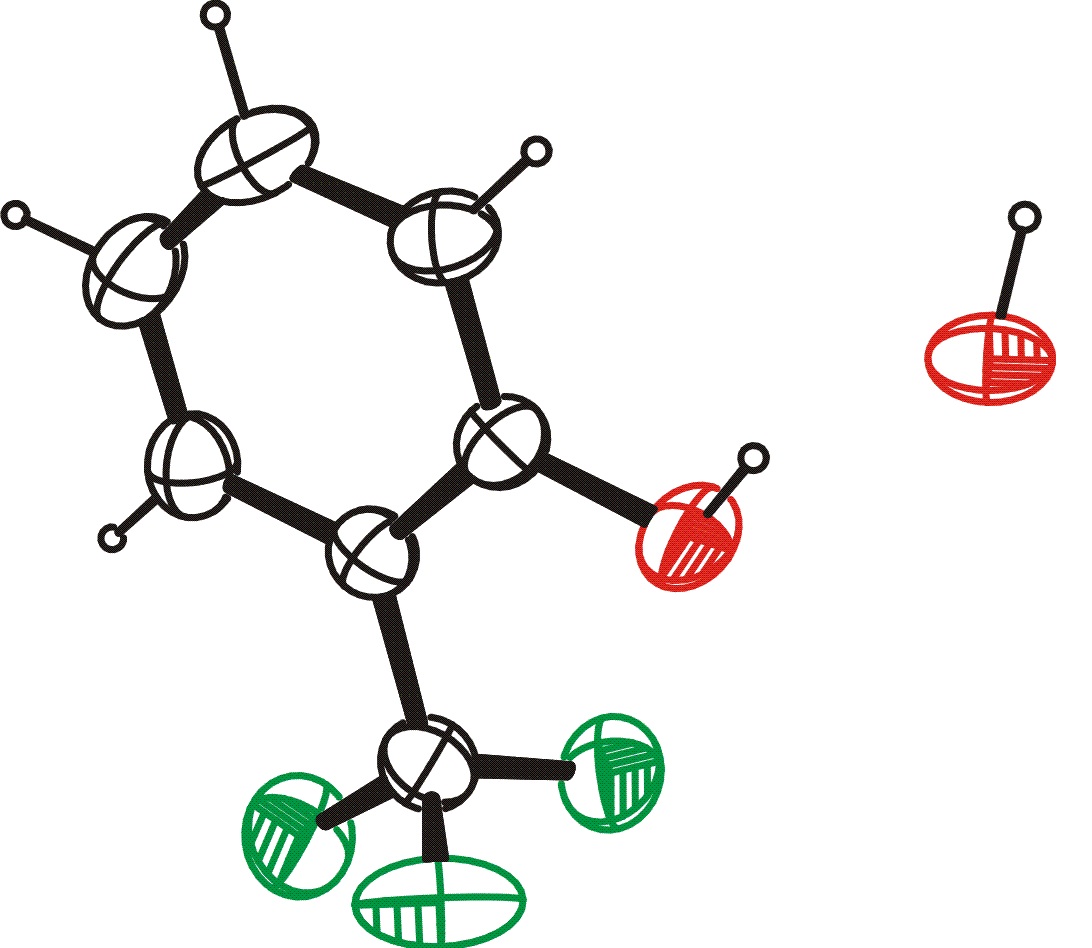

The structure of the title compound is shown in Figure 1.

Molecular structure of the title compound, showing 50% probability displacement ellipsoids and atom labelling. Selected bond lengths (in Å): C11–C12 1.3971(17); C12–C17 1.489(2); C11–O1 1.3720(18); C21–C22 1.3924(17); C22–C27 1.4890(18); C21–O21.3605(15).

The asymmetric unit comprises two molecules of the aromatic compound as well as half a molecule of water on a special crystallographic position. Intramolecular C–C–C angles for both molecules cover a range of 119.06(13)– 120.51(15)° and 119.51(13)– 121.03(13)°, respectively, with the largest angle invariably found on the carbon atom in para position to the trifluoromethyl-substituted carbon atom. In each molecule, the trifluoromethyl group adopts a staggered conformation with respect to the hydroxyl group. The least-squares planes defined by the respective carbon atoms of the two phenyl rings enclose an angle of 46.69(7)°. Selected bond lengths are given in the caption of Figure 1.

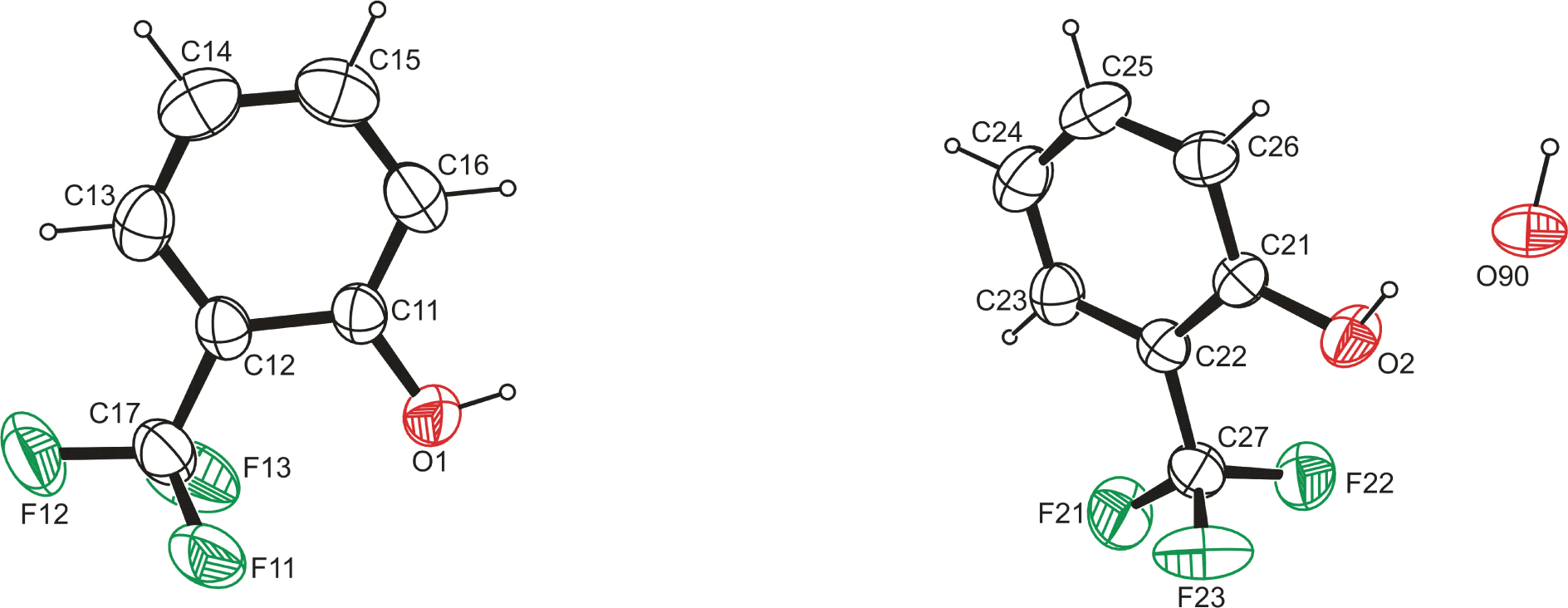

The two aromatic molecules in the asymmetric unit give rise to two different hydrogen bonding patterns completely independent from each other. While the first molecule forms isolated tetrameric units (Figure 2), the second molecule establishes – in connection with the water molecule present in the crystal structure – infinite chains along the crystallographic c axis (Figure 3).

![Figure 2 Cyclic tetrameric units in the crystal structure of the title compound, showing 50% probability displacement ellipsoids, viewed along [0 0 -1]. Symmetry operators: i -y+1/2, x, -z+1/2; iiy, -x+1/2, -z+1/2.](/document/doi/10.1515/chem-2018-0066/asset/graphic/j_chem-2018-0066_fig_002.jpg)

Cyclic tetrameric units in the crystal structure of the title compound, showing 50% probability displacement ellipsoids, viewed along [0 0 -1]. Symmetry operators: i -y+1/2, x, -z+1/2; iiy, -x+1/2, -z+1/2.

![Figure 3 Infinite chains formed by hydrogen bonds in the crystal structure of the title compound, showing 50% probability displacement ellipsoids, viewed along [0 1 0]. For clarity, fluorine atoms as well as all carbon-bound hydrogen atoms were omitted.](/document/doi/10.1515/chem-2018-0066/asset/graphic/j_chem-2018-0066_fig_003.jpg)

Infinite chains formed by hydrogen bonds in the crystal structure of the title compound, showing 50% probability displacement ellipsoids, viewed along [0 1 0]. For clarity, fluorine atoms as well as all carbon-bound hydrogen atoms were omitted.

In both patterns, cooperative hydrogen bonding is observed. Details about the hydrogen bonds are summarized in Table 2.

Hydrogen bonds in the crystal structure of 1 (distances in Å, angles in °).

| D | H | A | D–H | H…A | D…A | < D–H…A | Symmetry |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O1 | H1 | O1 | 0.84 | 1.97 | 2.7957(15) | 166.3 | -y+1/2, x, -z+1/2 |

| O2 | H2 | O90 | 0.84 | 1.89 | 2.6923(12) | 158.5 | |

| O90 | H90 | O2 | 0.874(18) | 1.904(19) | 2.7635(12) | 167.7(18) | -y+1, x-1/2, z-1/2 |

In terms of graph-set analysis [61,62], the descriptor for the hydrogen bonding pattern giving rise to the tetrameric units is R44(8) on the unary level while the infinite chains necessitate a DD descriptor on the same level. The shortest intercentroid distance between two aromatic systems was measured at 4.8077(9) Å in between the two different molecules present in the asymmetric unit and, therefore, rules out π-stacking to be a prominent stabilizing feature in the crystal.

The crystal structure of the hydrate of non-substituted phenol has been described earlier and was found to feature chains – alternating between water molecules and phenol – along the crystallographic c axis [63]. However, no 3D coordinates have been deposited with the Cambridge Structural Database [64] to allow for a re-assessment of the situation at hand or comparative studies with regards to the title compound. A comparison of the hydrogen bonding situation encountered in the crystalline states of the title compound and water-free non-substituted phenol reveals an interesting picture. While a pseudohelical chain-type connection along the crystallographic a axis of the three molecules present in the asymmetric unit of phenol was reported at ambient pressure [65], a slightly different situation is encountered in a high-pressure polymorph. In the latter case, two different chains – one exclusively made up of one of the three molecules present in the asymmetric unit, the other one alternately connecting the other two molecules present in the asymmetric unit – along the crystallographic b axis were reported [66]. The latter pattern as encountered in the high-pressure polymorph is, therefore, reminiscent of the chains supported by one of the two molecules of the title compound present in the asymmetric unit as well as the water molecule.

The lack of structural information available for comparable compounds in the literature precludes an in-depth comparable study about observable metrical trends with regards to the electronegativity of the halogen as well as the place of substitution.

3.2 Physical and Spectroscopic Properties

A proton NMR spectrum of the compound dissolved in dry deuterochloroform shows – apart from the expected set of aromatic protons – a broad signal around 4.9 ppm. The latter may be attributed to the phenolic hyxdroxyl group as well as the water molecule present in the title compound. 13C NMR spectra show marked C-F coupling for the CF3 group. The ipso-carbon atom as well as the two carbon atoms in ortho position to the trifluoromethyl group appear as quartets as well, however, C-F coupling is only weakly developed for the carbon atom bearing the hydroxyl group.

The presence of the different hydrogen bonding patterns in the title compound as established on grounds of the diffraction study based on single crystals is further corroborated by the results of vibrational spectroscopy as two neighbouring bands at 3441 and 3346 cm-1 are observed in the range that is typical for hydroxyl-groups. A splitting in this region of an IR spectrum has recently proven the presence of two distinguishable hydrogen bonds in case of the crystalline form of the cyanohydrine of cyclohexanone [67]. While the merging of the two bands in case of the latter compound was observed upon melting it close to room temperature, the same experiment could not be conducted for the title compound as the compound does not melt but rather sublimes at ambient conditions (see next paragraph).

Despite the extensive hydrogen bonding network, the compound is highly volatile. Even big crystals (~ 5 mm per edge) sublime completely within the course of a few hours if placed on a Petri-dish at ambient conditions.

3.3 Quantumchemical Calculations

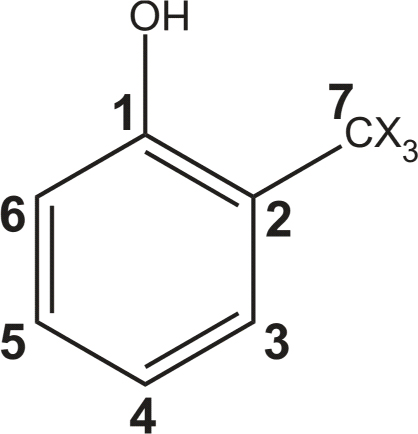

Due to the lack of experimental data available in the literature, it seemed of fundamental importance to assess the bonding situation and NMR characteristics as well as the metrical parameters of the title compound as well as its heavier homologues. Therefore, the structures of ortho-(trichloromethyl)phenol, ortho-(tribromomethyl) phenol and ortho-(triiodomethyl)phenol were modelled by DFT methods. As a benchmark, the title compound was subjected to the same DFT approach and the derived theoretical values were, as far as possible, correlated to experimental data. For all discussions, a labelling scheme as indicated in Figure 4 is used.

Labelling scheme applied for discussion of DFT results.

3.4 Metrical Parameters

In a first step, the metrical parameters were compared. The individual values for all calculated compounds are listed in Table 3.

Comparison of selected (averaged) bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) for ortho-CX3-substituted phenols (X = F, Cl, Br and I) calculated at the B3LYP/6-311++G(2d, p) level of theory (LanL2DZ in case of iodine) applying a solvent model for chloroform (DFT) with (averaged) experimental values for the fluorine derivative (XRD).

| Bond lengths / Angles | FXRD | FDFT | ClDFT | BrDFT | IDFT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d(O–1) | 1.37 | 1.36 | 1.36 | 1.36 | 1.36 |

| d(X–7) | 1.33 | 1.36 | 1.82 | 2.00 | 2.24 |

| d(1–2) | 1.39 | 1.40 | 1.41 | 1.42 | 1.42 |

| d(2–3) | 1.39 | 1.40 | 1.40 | 1.40 | 1.41 |

| d(3–4) | 1.38 | 1.39 | 1.39 | 1.38 | 1.38 |

| d(4–5) | 1.38 | 1.39 | 1.39 | 1.39 | 1.39 |

| d(5–6) | 1.38 | 1.39 | 1.38 | 1.38 | 1.38 |

| d(6–1) | 1.38 | 1.39 | 1.39 | 1.39 | 1.39 |

| d(2–7) | 1.49 | 1.50 | 1.51 | 1.50 | 1.50 |

| <(1–2–3) | 119.4 | 119.6 | 118.1 | 117.6 | 116.6 |

| <(2–3–4) | 120.4 | 120.8 | 121.7 | 122.0 | 122.6 |

| <(3–4–5) | 119.8 | 119.3 | 119.5 | 119.6 | 119.7 |

| <(4–5–6) | 120.8 | 120.6 | 120.0 | 119.8 | 119.5 |

| <(5–6–1) | 119.8 | 120.4 | 120.9 | 121.0 | 121.1 |

| <(6–1–2) | 120.0 | 119.3 | 119.8 | 120.0 | 120.5 |

As can readily be seen, the calculated values of the title compound show good agreement with the experimentally found ones thus proving the suitability of the chosen method and basis-set for the calculation. The slight differences in between these two kinds of values can be rationalized by taking into account packing effects in the crystal that are not accounted for by the DFT calculations applying a solvent model as well as the influence of the water molecule and its pertaining hydrogen bonding system present in the crystal structure might have. The C–O as well as the C–CX3 bond lengths remain vastly unaffected by the nature of the halogen substituent present. While the intracyclic angles on the carbon atom bearing the CX3 group as well as the carbon atom in para position to the latter gradually decrease with the increasing size of the halogen atoms present on the trihalomethyl moiety, all other intracyclic C–C–C angles invariably grow bigger at the same time. This trend can be explained by the increasing steric bulk of the respective CX3 group with respect to the neighbouring hydroxyl group that will result in an increasing “pull” on the aromatic scaffold. As expected, the respective C–X bonds are getting longer with increasing size of the halogen. It is pertinent to note that the predicted (and, in case of fluorine, found) values are in good agreement with the most common values observed for the respective CX3 groups in compounds whose metrical parameters have been deposited with the Cambridge Structural Database [64] (cf. Figure 5).

![Figure 5 Distribution of C–X bond lengths for compounds featuring CX3 moieties whose metrical parameters have been deposited with the Cambridge Structural Database [64] for CF3 (left), CCl3 (center) and CBr3 (right) (CSD version 5.35, updates May 2014).](/document/doi/10.1515/chem-2018-0066/asset/graphic/j_chem-2018-0066_fig_005.jpg)

Distribution of C–X bond lengths for compounds featuring CX3 moieties whose metrical parameters have been deposited with the Cambridge Structural Database [64] for CF3 (left), CCl3 (center) and CBr3 (right) (CSD version 5.35, updates May 2014).

While ample structural information is available for compounds with CF3 and CCl3 groups, considerable less studies have been conducted for compounds containing CBr3 substituents. For the heaviest moiety – CI3 – only iodoform [68] or compounds classifying as co-crystallizates thereof have been reported, the only exceptions being tetraiodomethane [69] and an alkoxidoaluminate salt of the CI3+ cation [70].

3.5 NMR Parameters

In addition to the metrical parameters, carbon NMR shifts were calculated for the title compound as well as for its heavier homologues. An overview of the calculated (DFT) and experimentally-determined (EXP) shifts relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS) as a reference is given in Table 4. The labelling scheme given in Figure 4 is used to identify the individual carbon atoms.

Comparison of 13C NMR shifts for ortho-CX3-substituted phenols (X = F, Cl, Br and I) calculated at the PBE1PBE/6-311++G(2d, p) level of theory (LanL2DZ in case of iodine) applying a solvent model for chloroform (DFT) with experimental values for the fluorine derivative (EXP). All values are given relative to TMS as the reference.

| Atom | FEXP | FDFT | ClDFT | BrDFT | IDFT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 153.7 | 161.4 | 161.0 | 161.2 | 160.8 |

| C2 | 116.8 | 119.3 | 132.9 | 137.2 | 143.2 |

| C3 | 127.0 | 132.2 | 132.4 | 133.4 | 133.7 |

| C4 | 120.7 | 124.3 | 123.5 | 123.2 | 122.6 |

| C5 | 133.6 | 140.2 | 139.9 | 140.3 | 139.9 |

| C6 | 117.6 | 122.6 | 123.6 | 123.8 | 123.7 |

| C7 | 124.3 | 135.8 | 131.3 | 134.1 | 114.1 |

The experimental 13C NMR shifts for the CF3-substituted phenol invariably are found at slightly higher fields than predicted. The deviation from the found values is most pronounced for the carbon atom of the CF3 group as well as the carbon atom bearing the hydroxyl group. For all other carbon atoms the discrepancy between experimental and respective theoretical values is small and in the range of few parts per million. The theoretical data obtained will allow for an assignment of carbon resonances once the chlorine, bromine and iodine homologues of the title compound are accessible experimentally.

3.6 Natural Charges

To allow for the identification of preferred centers of reactivity of the title compound with regards to reactions with nucleophiles as well as electrophiles, the natural charges of the non-hydrogen atoms of the title compound as well as its heavier homologues were calculated. An overview of the numerical values for all four compounds is given in Table 5. The labelling scheme as outlined in Figure 4 is retained.

Natural charges of the non-hydrogen atoms of ortho-CX3-substituted phenols (X = F, Cl, Br and I) calculated at the B3LYP/6-311++G(2d, p) level of theory (LanL2DZ in case of iodine) applying a solvent model for chloroform (DFT). The labelling scheme as outlined in Figure 4 is used for the carbon atoms, ‘X’ refers to the respective halogen atoms whose charge has been averaged over all three atoms present in the CX3 moiety.

| Atom | F | Cl | Br | I |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | +0.35 | +0.35 | +0.35 | +0.35 |

| C2 | -0.23 | -0.20 | -0.22 | -0.24 |

| C3 | -0.16 | -0.16 | -0.16 | -0.16 |

| C4 | -0.24 | -0.23 | -0.23 | -0.23 |

| C5 | -0.16 | -0.16 | -0.16 | -0.16 |

| C6 | -0.24 | -0.24 | -0.24 | -0.24 |

| C7 | +1.08 | -0.13 | -0.34 | -0.67 |

| O | -0.69 | -0.69 | -0.69 | -0.69 |

| X | -0.37 | -0.03 | +0.10 | +0.23 |

It can be seen that – apart from the carbon atom bearing the respective CX3 group – the natural charges calculated for the carbon atoms of the aromatic system of the four different ortho-(trihalomethyl) phenols remain vastly unaffected by the nature of the halogen. The slight changes in the natural charge of the carbon atom bearing the CX3 moiety can be explained as a superposition of the electronic situation encountered in the respective CX3 unit as well as the change in the bonding distance between C2 and C7 (according to the labelling outlined in Figure 4). The biggest changes in the natural charge are observed within the various CX3 groups. In accordance with the differences in electronegativity for carbon and the halogens according to Allen – C: 2.544, F: 4.193, Cl: 2.869, Br: 2.685, I: 2.359 [71] – the natural charge of the carbon atom of the CX3 group changes from a markedly positive value in the case of fluorine to a negative value in the case of iodine while the reversed trend is apparent for the respective halogen atoms themselves upon descending from the lightest to the heaviest member of the group. The early onset of a negative charge for the carbon atom already in the CCl3 group despite the still high difference in terms of electronegativity between carbon and chlorine could be attributed to the overall negative inductive effect of the halogen atoms that increases the “electron retaining” ability of the central carbon atom. It is pertinent to note that – as was observed for the carbon atoms of the aromatic scaffold – the natural charge of the oxygen atom also remains unaffected by the nature of the halogen atom present in the ortho-(trihalomethyl) group.

3.7 Bonding Situation

To assess the bonding situation in the homologous series of ortho-(trihalomethyl)phenols – especially with regard to the functional groups as well as the carbon atoms bearing the latter – NBO analyses were conducted. For all compounds it was invariably found that the contribution of the carbon atom to the C–O bond is above 33% although this figure slightly decreases with an increasing mass of the halogen atom present in the CX3 group. A different picture is obtained examining the respective C–X bonds where the contribution of the carbon atom rises significantly with a decrease of the electronegativity of the halogen atom and spans a range of just 27% in the CF3 group up to about 60% in the CI3 group. Simultaneously, the p orbital contribution of the carbon atom increases as becomes apparent by its formal hybridization of sp3.76 in the CF3 group that grows to sp4.01 in the CI3 group. The natural electronic configuration of the carbon atom in the various ortho-(trihalomethyl)phenols is in agreement with the natural charges as discussed in the previous section as it increases from s0.79p2.08 for the fluorine derivative to s1.26p3.35 for the iodine derivative. If Rydberg orbitals as well as core-centered electrons are neglected, second order perturbation theory calculations invariably show the interaction of one of the lone pairs on the oxygen atom and the anti-bonding orbital of the C1–C2 bond (labelling according to Figure 4) to be the most stabilizing factor whose energy monotonously decreases from 125 kJ mol-1 for ortho-(trifluoromethyl)phenol to 120 kJ mol-1 for ortho-(triiodomethyl)phenol. If interactions between exclusively anti-bonding orbitals are included into the discussion, a much stronger pronounced trend is observed for the anti-bonding orbitals of the C1–C2 and the C5–C6 bond where a steady decrease in stabilization energy from 729 kJ mol-1 for the CF3 derivative to 588 kJ mol-1 for the CI3 derivative is calculated.

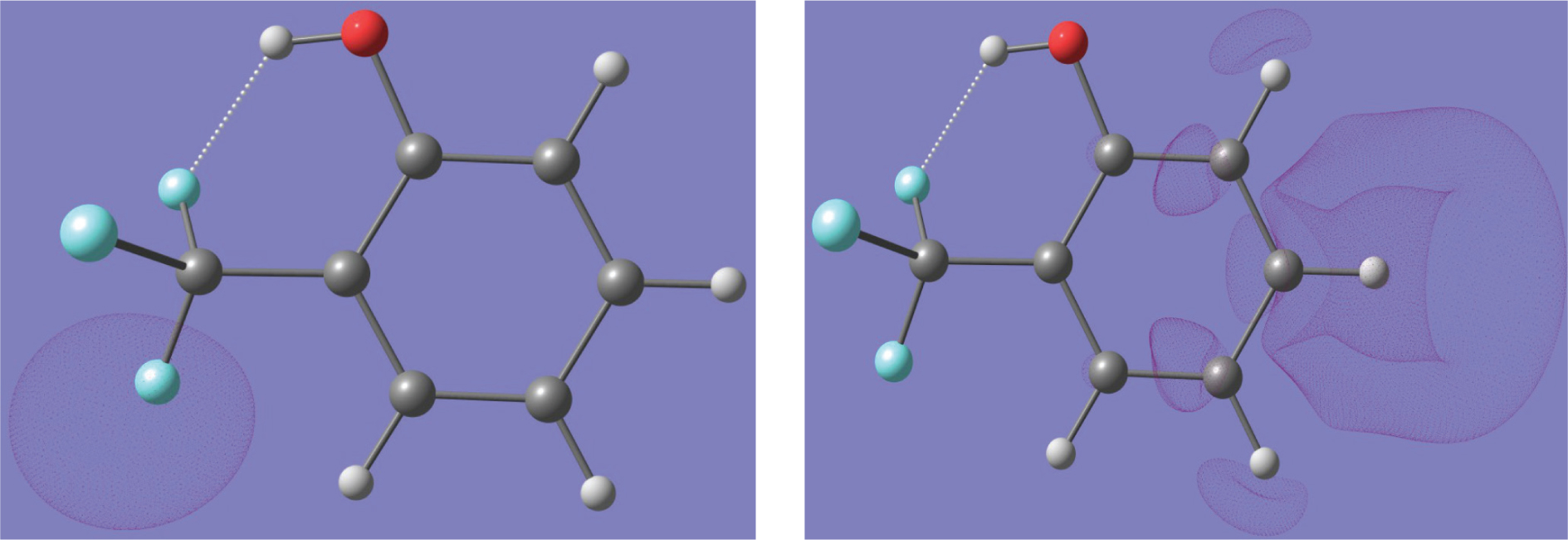

An inspection of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) shows the former to be centered on the trihalomethyl group for all four ortho-(trihalomethyl) phenols while the latter is located on the carbon and hydrogen atoms in meta- and para-position to the respective trihalomethyl entities of the aromatic system. As an example, isocontour plots of the CF3 derivative are shown in Figure 6.

Isosurface plots of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of ortho-(trifluoromethyl)phenol. Very similar pictures are obtained for the other ortho-(trihalomethyl)phenols.

The energetic gap between these two types of orbitals decreases with increasing mass of the halogen present in the CX3 group – while a gap of 543 kJ mol-1 is found for ortho-(trifluoromethyl)phenol, this value drops in steps of approximately 70 kJ mol-1 for each heavier homologue of fluorine to, eventually, 334 kJ mol-1 in ortho-(triiodomethyl) phenol.

4 Conclusions

The crystal and molecular structure of commercially-available ortho-(trifluoromethyl)phenol were determined as the first example of an ortho-CX3-substituted phenol derivative and found to be a defined hydrate in the crystalline state. An analysis of the hydrogen bonding system present in the title compound revealed parallels to the crystal structure of the hydrate of non-substituted phenol as well as the crystal structure of a high-pressure polymorph of anhydrous phenol. DFT calculations on the title compound as well as its higher homologues featuring the heavier halogens allowed for an assessment of the bonding situation as well as charge distribution on specific atoms of the individual compounds allowing for the identification of potential reaction sites for attacks of nucleophiles and electrophiles for further derivatization reactions. With this knowledge at hand, concise experimental studies about derivatives of the title compound as well as other ortho-(trihalomethyl) phenols can be conducted, not only with regard to their coordination behaviour to main group elements or transition metals but also with regards to further derivatization reactions starting from these materials. The unexpected and surprising presence of a molecule of water in the title compound (turning it into the half-hemi-hydrate) that was confirmed – although neither the compound’s description nor the analytical certificate did specify it – explains the hydrolysis products observed upon reacting it with substrates prone to hydrolysis. This finding further reinforces the notion that one has to remain suspicious about the nature and identity of starting materials regardless of provider or date of purchase.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges financial support by Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. The Center for High Performance Computing in Cape Town is thanked for generous allocation of calculation time.

Conflict of interest: Author states no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Weast R.C., CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 56th ed., CRC Press, Cleveland, 1975.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Ballinger P., Long F.A., Acid Ionization Constants of Alcohols. II. Acidities of Some Substituted Methanols and Related Compounds, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1960, 82, 795–798.10.1021/ja01489a008Search in Google Scholar

[3] Becker H.G.O., Beckert R., Domschke G., Fanghänel E., Habicher W.D., Metz P., Pavel D., Schwetlick K., Organikum, 21st ed., Wiley-VCH, Weinheim 2001.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Arrowsmith M., Hill M.S., Kociok-Kohn G., MacDougall D.J., Mahon M.F., Mallov I., Three-Coordinate Beryllium β-Diketiminates: Synthesis and Reduction Chemistry, Inorg. Chem., 2012, 51, 13408–13418.10.1021/ic3022968Search in Google Scholar

[5] Cole M.L., Hibbs D.E., Jones C., Junk P.C., Smithies N.A., Imidazolium formation from the reaction of N-heterocyclic carbene stabilised group 13 trihydride complexes with organic acids, Inorg. Chim. Acta, 2005, 358, 102–108.10.1016/j.ica.2004.07.036Search in Google Scholar

[6] van Poppel L.H., Bott S.G., Barron A.R., Molecular structures of Ga(tBu)2(OPh)(pyz)·PhOH and [(tBu)2Ga(H2O)(μ-OH) Ga(tBu)2]2(μ-OC6H4O)·4(2-Mepy): intra- and inter-molecular hydrogen bonding to gallium aryloxides, Polyhedron, 2002, 21, 1877–1882.10.1016/S0277-5387(02)01066-5Search in Google Scholar

[7] Linti G., Frey R., Polborn K., Zur Chemie des Galliums, IV. Darstellung und Strukturen monomerer (2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidino)gallane, Chem. Ber., 1994, 127, 1387–1393.10.1002/cber.19941270810Search in Google Scholar

[8] van Poppel L.H., Bott S.G., Barron A.R., 1,4-Dioxobenzene Compounds of Gallium: Reversible Binding of Pyridines to [{(tBu)2Ga}2(μ-OC6H4O)]n in the Solid State, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2003, 125, 11006–11017.10.1021/ja0208714Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Chernov O.V., Smirnov A.Y., Portnyagin I.A., Khrustalev V.N., Nechaev M.S., Heteroleptic tin (II) dialkoxides stabilized by intramolecular coordination Sn(OCH2CH2NMe2)(OR) (R=Me, Et, iPr, tBu, Ph). Synthesis, structure and catalytic activity in polyurethane synthesis, J. Organomet. Chem., 2009, 694, 3184–3189.10.1016/j.jorganchem.2009.05.014Search in Google Scholar

[10] Rocks S.S., Brennessel W.W., Machonkin T.E., Holland P.L., Solution and Structural Characterization of Iron(II) Complexes with Ortho-Halogenated Phenolates: Insights Into Potential Substrate Binding Modes in Hydroquinone Dioxygenases, Inorg. Chem., 2010, 49, 10914–10929.10.1021/ic101377uSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Tsai M.-C., Tsai F.-T., Lu T.-T., Tsai M.-L., Wie Y.-C., Hsu I.-J., Lee J.-F., Liaw W.-F., Relative Binding Affinity of Thiolate, Imidazolate, Phenoxide, and Nitrite Toward the {Fe(NO)2} Motif of Dinitrosyl Iron Complexes (DNICs): The Characteristic Pre-Edge Energy of {Fe(NO)2}9 DNICs, Inorg. Chem., 2009, 48, 9579–9591.10.1021/ic901675pSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Esteruelas M.A., Garcia-Raboso J., Olivan M., Preparation of Half-Sandwich Osmium Complexes by Deprotonation of Aromatic and Pro-aromatic Acids with a Hexahydride Brønsted Base, Organometallics, 2011, 30, 3844–3852.10.1021/om200371rSearch in Google Scholar

[13] Edwards P.G., Andersen R.A., Zalkin A., Tertiary phosphine derivatives of the f-block metals. Preparation of X4M(Me2PCH2CH2PMe2)2, where X is halide, methyl or phenoxy and M is thorium or uranium. Crystal structure of tetraphenoxybis [bis(1,2-dimethylphosphino)ethane] uranium(IV), J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 7792–7794.10.1021/ja00416a019Search in Google Scholar

[14] Evans W.J., Miller K.A., DiPasquale A.G., Rheingold A.L., Stewart T.J., Bau R., A Crystallizable f-Element Tuck-In Complex: The Tuck-in Tuck-over Uranium Metallocene [(C5Me5)U{μ-η5:η1:η1-C5Me3(CH2)2}(μ-H)2U(C5Me5)2], Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2008, 47, 5075–5078.10.1002/anie.200801062Search in Google Scholar

[15] Spirlet M.R., Rebizant J., Apostolidis C., van den Bossche G., Kanellakopulos B., Structure of tris(η5-cyclopentadienyl) phenolatouranium(IV), Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Cryst. Struct. Commun., 1990, 46, 2318–2320.10.1107/S0108270190005054Search in Google Scholar

[16] De Ridder D.J.A., Apostolidis C., Rebizant J., Kanellakopulos B., Maier R., Tris(η5-cyclopentadienyl)phenolatoneptunium(IV), Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Cryst. Struct. Commun., 1996, 52, 1436–1438.10.1107/S0108270195014582Search in Google Scholar

[17] Domingos A., Marcalo J., Pires de Matos A., Bis [hydrotris(pyrazolyl)borate] thorium(IV) complexes: Synthesis and characterization of alkyl, thiolate, alkoxide and aryloxide derivatives and the x-ray crystal structure of Th(HBPz3)2(OPh)2, Polyhedron, 1992, 11, 909–915.10.1016/S0277-5387(00)83340-9Search in Google Scholar

[18] Zadrozny J.M., Telser J., Long J.R., Slow magnetic relaxation in the tetrahedral cobalt(II) complexes [Co(EPh)4]2- (EO, S, Se), Polyhedron, 2013, 64, 209–217.10.1016/j.poly.2013.04.008Search in Google Scholar

[19] Howard W.A., Trnka T.M., Parkin G., Syntheses of the Phenylchalcogenolate Complexes (h5-C5Me5)2Zr(EPh)2 (E = O, S, Se, Te) and (h5-C5H5)2Zr(OPh)2: Structural Comparisons within a Series of Complexes Containing Zirconium-Chalcogen Single Bonds, Inorg. Chem., 1995, 34, 5900–5909.10.1021/ic00127a031Search in Google Scholar

[20] Evans W.J., Miller K.A., Ziller J.W., Synthesis of (O2CEPh)1- Ligands (E = S, Se) by CO2 Insertion into Lanthanide Chalcogen Bonds and Their Utility in Forming Crystallographically Characterizable Organoaluminum Complexes [Me2Al(μ-O2CEPh)]2, Inorg. Chem., 2006, 45, 424–429.10.1021/ic0515610Search in Google Scholar

[21] Hascall T., Murphy V.J., Parkin G., Reversible C–H Bond Activation in Coordinatively Unsaturated Molybdenum Aryloxy Complexes, Mo(PMe3)4(OAr)H: Comparison with Their Tungsten Analogs, Organometallics, 1996, 15, 3910–3912.10.1021/om960553bSearch in Google Scholar

[22] Davies J.I., Gibson J.F., Skapski A.C., Wilkinson G., Wong W.-K., Synthesis of the hexaphenoxotungstate(V) ion; The x-ray crystal structures of the tetraethylammonium and lithium salts, Polyhedron, 1982, 1, 641–646.10.1016/S0277-5387(00)80861-XSearch in Google Scholar

[23] Lehtonen A., Sillanpaa R., Reactions of tris (1,2-ethanediolato) tungsten (VI) with phenyl acetates. X-ray structures of three products, Polyhedron, 1999, 18, 175–179.10.1016/S0277-5387(98)00281-2Search in Google Scholar

[24] Boyle T.J., Pedrotty D.M., Alam T.M., Vick S.C., Rodriguez M.A., Structural Diversity in Solvated Lithium Aryloxides. Syntheses, Characterization, and Structures of [Li(OAr)(THF)x]n and [Li(OAr)(py)x]2 Complexes Where OAr = OC6H5, OC6H4(2-Me), OC6H3(2,6-(Me))2, OC6H4(2-Pri), OC6H3(2,6-(Pri))2, OC6H4(2-But), OC6H3(2,6-(But))2, Inorg. Chem., 2000, 39, 5133–5146.10.1021/ic000432aSearch in Google Scholar

[25] Moravec Z., Sluka R., Necas M., Jancik V., Pinkas J., A Structurally Diverse Series of Aluminum Chloride Alkoxides [ClxAl(μ-OR)y]n (R = nBu, cHex, Ph, 2,4-tBu2C6H3), Inorg. Chem., 2009, 48, 8106–8114.10.1021/ic802251gSearch in Google Scholar

[26] Cleaver W.M., Barron A.R., McGufey A.R., Bott S.G., Alcoholysis of tri-tert-butylgallium: synthesis and structural characterization of [(But)2(μ-OR)]2, Polyhedron, 1994, 13, 2831–2846.10.1016/S0277-5387(00)86614-0Search in Google Scholar

[27] Briand G.G., Decken A., McKelvey J.I., Zhou Y., Structural Effects of Varied Steric Bulk in 2,(4),6-Substituted Dimethylthallium(III) Phenoxides, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem., 2011, 2298–2305.10.1002/ejic.201100043Search in Google Scholar

[28] Bortoluzzi M., Guazzelli N., Marchetti F., Pampaloni G., Zacchini S., Convenient synthesis of fluoride-alkoxides of Nb(V) and Ta(V): a spectroscopic, crystallographic and computational study, Dalton Trans., 2012, 41, 12898–12906.10.1039/c2dt31453cSearch in Google Scholar

[29] Yasuda H., Choi J.-C., Lee S.-C., Sakakura T., Structure of dialkyltin diaryloxides and their reactivity toward carbon dioxide and isocyanate, J. Organomet. Chem., 2002, 659, 133–141.10.1016/S0022-328X(02)01719-9Search in Google Scholar

[30] Yeh S.-W., Lin C.-W., Li Y.-W., Hsu I.-J., Chen C.-H., Jang L.-Y., Lee J.-F., Liaw W.-F., Insight into the Dinuclear {Fe(NO)2}10{Fe(NO)2}10 and Mononuclear {Fe(NO)2}10 Dinitrosyliron Complexes, Inorg. Chem., 2012, 51, 4076–4087.10.1021/ic202332dSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Watenpaugh K., Caughlan C.N., The Crystal and Molecular Structure of Dichlorodiphenoxytitanium(IV), Inorg. Chem., 1966, 5, 1782–1786.10.1021/ic50044a031Search in Google Scholar

[32] Pasquali M., Fiaschi B., Floriani C., Manfredotti A.G., Bridging phenoxo-ligands in dicopper(I) complexes: synthesis and structure of tetrakis(isocyanide)-bis(μ-phenoxo)-dicopper(I) complexes, J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun., 1983, 197–199.10.1039/C39830000197Search in Google Scholar

[33] Canty A.J., Devereux J.W., Skelton B.W., White A.H., Organo(organooxo)mercury(N) chemistry Synthesis and structure of methyl(phenoxo)mercury(II), Can. J. Chem., 2006, 84, 77–80.10.1139/v05-219Search in Google Scholar

[34] MacDougall D.J., Morris J.J., Noll B.C., Henderson K.W., Use of tetrameric cubane aggregates of lithium aryloxides as secondary building units in controlling network assembly, Chem. Commun., 2005, 456–458.10.1039/b413434fSearch in Google Scholar

[35] Boersma J., Spek A.L., Noltes J.G., Coordination complexes of bis(2,2-dimethyl-3,5-hexanedionato) zinc with organozinc-oxygen and -nitrogen compounds. Crystal structure of the complex formed with phenylzinc phenoxide, J. Organomet. Chem., 1974, 81, 7–15.10.1016/S0022-328X(00)87880-8Search in Google Scholar

[36] Enthaler S., Eckhardt B., Inoue S., Irran E., Driess M., Facile and Efficient Reduction of Ketones in the Presence of Zinc Catalysts Modified by Phenol Ligands, Chem. Asian J., 2010, 5, 2027–2035.10.1002/asia.201000317Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Kunert M., Dinjus E., Nauck M., Sieler J., Structure and Reactivity of Sodium Phenoxide - Following the Course of the Kolbe-Schmitt Reaction, Chem. Ber., 1997, 130, 1461–1465.10.1002/cber.19971301017Search in Google Scholar

[38] Watson K.A., Fortier S., Murchie M.P., Bovenkamp J.W., Crown ether complexes exhibiting unusual 1:2 macrocycle salt ratios: X-ray crystal structures of cyclohexano-15-crown-5•2LiOPh, cyclohexano-15-crown-5•2NaOPh, and 15-crown-5•2NaOPh, Can. J. Chem., 1991, 69, 687–695.10.1139/v91-103Search in Google Scholar

[39] Caulton K.G., Chisholm M.H., Drake S.R., Folting K., Synthesis and structural characterization of the first examples of molecular aggregates of barium supported by aryloxide and alkoxide ligands: [HBa5(O)(OPh)9(thf)8] and [H3Ba6(O) (OBut)11(OCEt2CH2O)(thf)3](thf = tetrahydrofuran), J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun., 1990, 1349–1351.10.1039/c39900001349Search in Google Scholar

[40] Malkowsky I.M., Frohlich R., Griesbach U., Putter H., Waldvogel S.R., Facile and Reliable Synthesis of Tetraphenoxyborates and Their Properties, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem., 2006, 1690–1697.10.1002/ejic.200600074Search in Google Scholar

[41] Zozulin A.J., Moody D.C., Ryan R.R., Synthesis and structure of a mixed-valent uranium complex: tetra-m-phenoxy-di-m3-oxo-bis(triphenoxy(tetrahydrofuran)uranium(V)) bis((tetrahydrofuran)dioxouranium(VI))], Inorg. Chem., 1982, 21, 3083–3086.10.1021/ic00138a031Search in Google Scholar

[42] Day V.W., Eberspacher T.A., Klemperor W.G., Liang S., Synthesis and Characterization of BaTi(OC6H5)6•2DMF, a Single-Source Sol-Gel Precursor to BaTiO3 Gels, Powders, and Thin Films, Chem. Mater., 1995, 7, 1607–1608.10.1021/cm00057a004Search in Google Scholar

[43] Drake S.R., Streib W.E., Chisholm M.H., Caulton K.G., Facile synthesis and structural principles of the strontium phenoxide Sr4(OPh)8(PhOH)2(THF)6, Inorg. Chem., 1990, 29, 2707–2708.10.1021/ic00340a002Search in Google Scholar

[44] Svetich G.W., Voge A.A., The crystal and molecular structure of sym-trans-di-μ-phenoxyhexaphenoxydiphenolatodititanium (IV), Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem., 1972, 28, 1760–1767.10.1107/S0567740872004984Search in Google Scholar

[45] Gowda R.R., Chakraborty D., Ramkumar V., New Aryloxy and Benzyloxy Derivatives of Titanium as Catalysts for Bulk Ring-Opening Polymerization of ε-Caprolactone and δ-Valerolactone, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem., 2009, 2009, 2981–2993.10.1002/ejic.200900280Search in Google Scholar

[46] Chandrasekaran A., Sood P., Day R.O., Holmes R.R., Chloro- and Fluoro-Substituted Phosphites, Phosphates, and Phosphoranes Exhibiting Sulfur and Oxygen Coordination, Inorg. Chem., 1999, 38, 3369–3376.10.1021/ic9901214Search in Google Scholar

[47] Hopfl H., Hernandez J., Salas-Reyes M., Cruz-Sanchez S., Crystal structure of eq-2-p-trifluoromethylphenoxy-2-boranecis-4,6-dimethyl-1,3,2λ3-dioxaphosphorinane, C12H17BF3O3P, Z. Kristallogr. New Cryst. Struct., 2009, 224, 249–250.10.1524/ncrs.2009.0111Search in Google Scholar

[48] Theil I., Jiao H., Spannenberg A., Hapke M., Fine-Tuning the Reactivity and Stability by Systematic Ligand Variations in CpCoI Complexes as Catalysts for [2+2+2] Cycloaddition Reactions, Chem. Eur. J., 2013, 19, 2548–2554.10.1002/chem.201202946Search in Google Scholar

[49] Neu R.C., Ouyang E.Y., Geier S.J., Zhao X., Ramos A., Stephan D. W., Probing substituent effects on the activation of H2 by phosphorus and boron frustrated Lewis pairs, Dalton Trans., 2010, 39, 4285–4294.10.1039/c001133aSearch in Google Scholar

[50] Kovacs A., Kolossvary I., Csonka G.I., Hargittai I., Theoretical study of intramolecular hydrogen bonding and molecular geometry of 2-trifluoromethylphenol, J. Comput. Chem., 1996, 17, 1804–1819.10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199612)17:16<1804::AID-JCC2>3.0.CO;2-RSearch in Google Scholar

[51] Gottlieb H.E., Kotlyar V., Nudelman A., NMR Chemical Shifts of Common Laboratory Solvents as Trace Impurities, J. Org. Chem., 1997, 62, 7512–7515.10.1021/jo971176vSearch in Google Scholar

[52] Frisch, M. J.; Trucks, G. W.; Schlegel, H. B.; Scuseria, G. E.; Robb, M. A.; Cheeseman, J. R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G. A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Caricato, M.; Li, X.; Hratchian, H. P.; Izmaylov, A. F.; Bloino, J.; Zheng, G.; Sonnenberg, J. L.; Hada, M.; Ehara, M.; Toyota, K.; Fukuda, R.; Hasegawa, J.; Ishida, M.; Nakajima, T.; Honda, Y.; Kitao, O. ; Nakai, H.; Vreven, T.; Montgomery, J. A., Jr.; Peralta, J. E.; Ogliaro, F.; Bearpark, M.; Heyd, J. J.; Brothers, E.; Kudin, K. N.; Staroverov, V. N.; Kobayashi, R.; Normand, J.; Raghavachari, K.; Rendell, A.; Burant, J. C.; Iyengar, S. S.; Tomasi, J.; Cossi, M.; Rega, N.; Millam, J. M.; Klene, M.; Knox, J. E.; Cross, J. B.; Bakken, V.; Adamo, C.; Jaramillo, J.; Gomperts, R.; Stratmann, R. E.; Yazyev, O.; Austin, A. J.; Cammi, R.; Pomelli, C.; Ochterski, J. W.; Martin, R. L.; Morokuma, K.; Zakrzewski, V. G.; Voth, G. A.; Salvador, P.; Dannenberg, J. J.; Dapprich, S.; Daniels, A. D.; Farkas, Ö.; Foresman, J. B.; Ortiz, J. V.; Cioslowski, J.; Fox, D. J., Gaussian 09, Revision 01, Gaussian Inc., Wallingford CT, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Dennington, R.; Keith, T.; Millam, GaussView, J. Semichem Inc., Shawnee Mission KS, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Wolinski K., Hinton J.F., Pulay P., Efficient implementation of the gauge-independent atomic orbital method for NMR chemical shift calculations, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1990, 112, 8251–8260.10.1021/ja00179a005Search in Google Scholar

[55] Hanwell M.D., Curtis D.E., Lonie D.C., Vandermeersch T., Zurek E., Hutchison G.R., Avogadro: an advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform, J. Cheminf. 2012, 4:17.10.1186/1758-2946-4-17Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[56] Zhurko, G. A.; Chemcraft (Version 1.7, build 132). http://www.chemcraftprog.com.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Sheldrick G.M., A short history of SHELX, Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr., 2008, 64, 112–122.10.1107/S0108767307043930Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[58] Spek A.L., Structure validation in chemical crystallography, Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr., 2009, 65, 148–155.10.1107/S090744490804362XSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[59] Macrae C.F., Bruno I.J., Chisholm J.A., Edgington P.R., McCabe P., Pidcock E., Rodriguez-Monge L., Taylor R., van de Streek J., Wood P.A., Mercury CSD 2.0 – new features for the visualization and investigation of crystal structures, J. Appl. Crystallogr., 2008, 41, 466–470.10.1107/S0021889807067908Search in Google Scholar

[60] Farrugia L.J., WinGX and ORTEP for Windows: an update, J. Appl. Crystallogr., 2012, 45, 8 49–854.10.1107/S0021889812029111Search in Google Scholar

[61] Bernstein J., Davis R.E., Shimoni L., Chang N.-L., Patterns in Hydrogen Bonding: Functionality and Graph Set Analysis in Crystals, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl., 1995, 34, 1555–1573.10.1002/anie.199515551Search in Google Scholar

[62] Etter M.C., MacDonald J.C., Bernstein J., Graph-set analysis of hydrogen-bond patterns in organic crystals, Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci. 1990, 46, 256–262.10.1107/S0108768189012929Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[63] Meuthen B., von Stackelberg M., Röntgenographische Untersuchungen an Dimethylphenolen, Z. Elektrochem., 1960, 64, 386–387.10.1002/bbpc.19600640309Search in Google Scholar

[64] Allen F.H., The Cambridge Structural Database: a quarter of a million crystal structures and rising, Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B: Struct. Sci., 2002, 58, 380–388.10.1107/S0108768102003890Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] Zavodnik V.E., Bel’skii V.K., Zorki P.M., <title unknown>, Zh. Strukt. Khim., 1987, 28, 175-5.Search in Google Scholar

[66] Allan D.R., Clark S.J., Dawson A., McGregor P.A., Parsons S., Pressure-induced polymorphism in phenol, Acta. Crystallogr. Sect B: Struct. Sci., 2002, 58, 1018–1024.10.1107/S0108768102018797Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[67] Hosten E.C., Betz R., Synthesis, spectral, and structural characteristics of cyanohydrines derived from aliphatic cyclic ketones, Russ. J. Gen. Chem., 2014, 84, 2222–2227.10.1134/S1070363214110309Search in Google Scholar

[68] Bertolotti F., Gervasio G., Crystal structure of iodoform at 106K and of the adduct CHI3·3(C9H7N). Iodoform as a building block of co-crystals, J. Mol. Struct., 2013, 1036, 305–310.10.1016/j.molstruc.2012.11.016Search in Google Scholar

[69] Pohl S., Die Kristallstruktur von CI4, Z. Kristallogr., Kristallgeom., Kristallphys., Kristallchem., 1982, 159, 211–216.10.1524/zkri.1982.159.14.211Search in Google Scholar

[70] Krossing I., Bihlmeier A., Raabe I., Trapp N., Structure and Characterization of CI3+[Al{OC(CF3)3}4]-; Lewis Acidities of CX3+ and BX3, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2003, 42, 1531–1534.10.1002/anie.200250172Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[71] Allen L.C., Electronegativity is the average one-electron energy of the valence-shell electrons in ground-state free atoms, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1989, 111, 9003–9014.10.1021/ja00207a003Search in Google Scholar

© 2018 Richard Betz, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The effect of CuO modification for a TiO2 nanotube confined CeO2 catalyst on the catalytic combustion of butane

- The preparation and antibacterial activity of cellulose/ZnO composite: a review

- Linde Type A and nano magnetite/NaA zeolites: cytotoxicity and doxorubicin loading efficiency

- Performance and thermal decomposition analysis of foaming agent NPL-10 for use in heavy oil recovery by steam injection

- Spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, UV, 1H and 13C NMR) insights, electronic profiling and DFT computations on ({(E)-[3-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-1-phenylpropylidene] amino}oxy)(4-nitrophenyl)methanone, an imidazole-bearing anti-Candida agent

- A Simplistic Preliminary Assessment of Ginstling-Brounstein Model for Solid Spherical Particles in the Context of a Diffusion-Controlled Synthesis

- M-Polynomials And Topological Indices Of Zigzag And Rhombic Benzenoid Systems

- Photochemical Transformation of some 3-benzyloxy-2-(benzo[b]thiophen-2-yl)-4Hchromen-4-ones: A Remote Substituent Effect

- Dynamic Changes of Secondary Metabolites and Antioxidant Activity of Ligustrum lucidum During Fruit Growth

- Studies on the flammability of polypropylene/ammonium polyphosphate and montmorillonite by using the cone calorimeter test

- DSC, FT-IR, NIR, NIR-PCA and NIR-ANOVA for determination of chemical stability of diuretic drugs: impact of excipients

- Antioxidant and Hepatoprotective Effects of Methanolic Extracts of Zilla spinosa and Hammada elegans Against Carbon Tetrachlorideinduced Hepatotoxicity in Rats

- Prunus cerasifera Ehrh. fabricated ZnO nano falcates and its photocatalytic and dose dependent in vitro bio-activity

- Organic biocides hosted in layered double hydroxides: enhancing antimicrobial activity

- Experimental study on the regulation of the cholinergic pathway in renal macrophages by microRNA-132 to alleviate inflammatory response

- Synthesis, characterization, in-vitro antimicrobial properties, molecular docking and DFT studies of 3-{(E)-[(4,6-dimethylpyrimidin-2-yl)imino]methyl} naphthalen-2-ol and Heteroleptic Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Zn(II) complexes

- M-Polynomials and Topological Indices of Dominating David Derived Networks

- Human Health Risk Assessment of Trace Metals in Surface Water Due to Leachate from the Municipal Dumpsite by Pollution Index: A Case Study from Ndawuse River, Abuja, Nigeria

- Analysis of Bowel Diseases from Blood Serum by Autofluorescence and Atomic Force Microscopy Techniques

- Hydrographic parameters and distribution of dissolved Cu, Ni, Zn and nutrients near Jeddah desalination plant

- Relationships between diatoms and environmental variables in industrial water biotopes of Trzuskawica S.A. (Poland)

- Optimum Conversion of Major Ginsenoside Rb1 to Minor Ginsenoside Rg3(S) by Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Acid Hydrolysis Treatment

- Antioxidant, Anti-microbial Properties and Chemical Composition of Cumin Essential Oils Extracted by Three Methods

- Regulatory mechanism of ulinastatin on autophagy of macrophages and renal tubular epithelial cells

- Investigation of the sustained-release mechanism of hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose skeleton type Acipimox tablets

- Bio-accumulation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Grey Mangrove (Avicennia marina) along Arabian Gulf, Saudi Coast

- Dynamic Change of Secondary Metabolites and spectrum-effect relationship of Malus halliana Koehne flowers during blooming

- Lipids constituents from Gardenia aqualla Stapf & Hutch

- Effect of using microwaves for catalysts preparation on the catalytic acetalization of glycerol with furfural to obtain fuel additives

- Effect of Humic Acid on the Degradation of Methylene Blue by Peroxymonosulfate

- Serum containing drugs of Gua Lou Xie Bai decoction (GLXB-D) can inhibit TGF-β1-Induced Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in A549 Cells

- Antiulcer Activity of Different Extracts of Anvillea garcinii and Isolation of Two New Secondary Metabolites

- Analysis of Metabolites in Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz Dry Red Wines from Shanxi by 1H NMR Spectroscopy Combined with Pattern Recognition Analysis

- Can water temperature impact litter decomposition under pollution of copper and zinc mixture

- Released from ZrO2/SiO2 coating resveratrol inhibits senescence and oxidative stress of human adipose-derived stem cells (ASC)

- Validated thin-layer chromatographic method for alternative and simultaneous determination of two anti-gout agents in their fixed dose combinations

- Fast removal of pollutants from vehicle emissions during cold-start stage

- Review Article

- Catalytic activities of heterogeneous catalysts obtained by copolymerization of metal-containing 2-(acetoacetoxy)ethyl methacrylate

- Antibiotic Residue in the Aquatic Environment: Status in Africa

- Regular Articles

- Mercury fractionation in gypsum using temperature desorption and mass spectrometric detection

- Phytosynthetic Ag doped ZnO nanoparticles: Semiconducting green remediators

- Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Induced by SMAD4 Activation in Invasive Growth Hormone-Secreting Adenomas

- Physicochemical properties of stabilized sewage sludge admixtures by modified steel slag

- In Vitro Cytotoxic and Antiproliferative Activity of Cydonia oblonga flower petals, leaf and fruit pellet ethanolic extracts. Docking simulation of the active flavonoids on anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2

- Synthesis and Characterization of Pd exchanged MMT Clay for Mizoroki-Heck Reaction

- A new selective, and sensitive method for the determination of lixivaptan, a vasopressin 2 (V2)-receptor antagonist, in mouse plasma and its application in a pharmacokinetic study

- Anti-EGFL7 antibodies inhibit rat prolactinoma MMQ cells proliferation and PRL secretion

- Density functional theory calculations, vibration spectral analysis and molecular docking of the antimicrobial agent 6-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-ylmethyl)-5-ethyl-2-{[2-(morpholin-4-yl)ethyl] sulfanyl}pyrimidin-4(3H)-one

- Effect of Nano Zeolite on the Transformation of Cadmium Speciation and Its Uptake by Tobacco in Cadmium-contaminated Soil

- Effects and Mechanisms of Jinniu Capsule on Methamphetamine-Induced Conditioned Place Preference in Rats

- Calculating the Degree-based Topological Indices of Dendrimers

- Efficient optimization and mineralization of UV absorbers: A comparative investigation with Fenton and UV/H2O2

- Metabolites of Tryptophane and Phenylalanine as Markers of Small Bowel Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

- Adsorption and determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water through the aggregation of graphene oxide

- The role of NR2C2 in the prolactinomas

- Chromium removal from industrial wastewater using Phyllostachys pubescens biomass loaded Cu-S nanospheres

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Preparation of Calcium Fluoride using Phosphogypsum by Orthogonal Experiment

- The mechanism of antibacterial activity of corylifolinin against three clinical bacteria from Psoralen corylifolia L

- 2-formyl-3,6-bis(hydroxymethyl)phenyl benzoate in Electrochemical Dry Cell

- Electro-photocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin using calcium titanate

- Effect of Malus halliana Koehne Polysaccharides on Functional Constipation

- Structural Properties and Nonlinear Optical Responses of Halogenated Compounds: A DFT Investigation on Molecular Modelling

- DMFDMA catalyzed synthesis of 2-((Dimethylamino)methylene)-3,4-dihydro-9-arylacridin-1(2H)-ones and their derivatives: in-vitro antifungal, antibacterial and antioxidant evaluations

- Production of Methanol as a Fuel Energy from CO2 Present in Polluted Seawater - A Photocatalytic Outlook

- Study of different extraction methods on finger print and fatty acid of raw beef fat using fourier transform infrared and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- Determination of trace fluoroquinolones in water solutions and in medicinal preparations by conventional and synchronous fluorescence spectrometry

- Extraction and determination of flavonoids in Carthamus tinctorius

- Therapeutic Application of Zinc and Vanadium Complexes against Diabetes Mellitus a Coronary Disease: A review

- Study of calcined eggshell as potential catalyst for biodiesel formation using used cooking oil

- Manganese oxalates - structure-based Insights

- Topological Indices of H-Naphtalenic Nanosheet

- Long-Term Dissolution of Glass Fibers in Water Described by Dissolving Cylinder Zero-Order Kinetic Model: Mass Loss and Radius Reduction

- Topological study of the para-line graphs of certain pentacene via topological indices

- A brief insight into the prediction of water vapor transmissibility in highly impermeable hybrid nanocomposites based on bromobutyl/epichlorohydrin rubber blends

- Comparative sulfite assay by voltammetry using Pt electrodes, photometry and titrimetry: Application to cider, vinegar and sugar analysis

- MicroRNA delivery mediated by PEGylated polyethylenimine for prostate cancer therapy

- Reversible Fluorescent Turn-on Sensors for Fe3+ based on a Receptor Composed of Tri-oxygen Atoms of Amide Groups in Water

- Sonocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in aqueous solution using Fe-doped TiO2 nanoparticles under mechanical agitation

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Production and Analysis of Recycled Ammonium Perrhenate from CMSX-4 superalloys

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- New phosphorus biofertilizers from renewable raw materials in the aspect of cadmium and lead contents in soil and plants

- Survey of content of cadmium, calcium, chromium, copper, iron, lead, magnesium, manganese, mercury, sodium and zinc in chamomile and green tea leaves by electrothermal or flame atomizer atomic absorption spectrometry

- Biogas digestate – benefits and risks for soil fertility and crop quality – an evaluation of grain maize response

- A numerical analysis of heat transfer in a cross-current heat exchanger with controlled and newly designed air flows

- Freshwater green macroalgae as a biosorbent of Cr(III) ions

- The main influencing factors of soil mechanical characteristics of the gravity erosion environment in the dry-hot valley of Jinsha river

- Free amino acids in Viola tricolor in relation to different habitat conditions

- The influence of filler amount on selected properties of new experimental resin dental composite

- Effect of poultry wastewater irrigation on nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon contents in farmland soil

- Response of spring wheat to NPK and S fertilization. The content and uptake of macronutrients and the value of ionic ratios

- The Effect of Macroalgal Extracts and Near Infrared Radiation on Germination of Soybean Seedlings: Preliminary Research Results

- Content of Zn, Cd and Pb in purple moor-grass in soils heavily contaminated with heavy metals around a zinc and lead ore tailing landfill

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Synthesis of (±)-3,4-dimethoxybenzyl-4-methyloctanoate as a novel internal standard for capsinoid determination by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS(QTOF)

- Repellent activity of monoterpenoid esters with neurotransmitter amino acids against yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti

- Effect of Flammulina velutipes (golden needle mushroom, eno-kitake) polysaccharides on constipation

- Bioassay-directed fractionation of a blood coagulation factor Xa inhibitor, betulinic acid from Lycopus lucidus

- Antifungal and repellent activities of the essential oils from three aromatic herbs from western Himalaya

- Chemical composition and microbiological evaluation of essential oil from Hyssopus officinalis L. with white and pink flowers

- Bioassay-guided isolation and identification of Aedes aegypti larvicidal and biting deterrent compounds from Veratrum lobelianum

- α-Terpineol, a natural monoterpene: A review of its biological properties

- Utility of essential oils for development of host-based lures for Xyleborus glabratus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae), vector of laurel wilt

- Phenolic composition and antioxidant potential of different organs of Kazakh Crataegus almaatensis Pojark: A comparison with the European Crataegus oxyacantha L. flowers

- Isolation of eudesmane type sesquiterpene ketone from Prangos heyniae H.Duman & M.F.Watson essential oil and mosquitocidal activity of the essential oils

- Comparative analysis of the polyphenols profiles and the antioxidant and cytotoxicity properties of various blue honeysuckle varieties

- Special Issue on ICCESEN 2017

- Modelling world energy security data from multinomial distribution by generalized linear model under different cumulative link functions

- Pine Cone and Boron Compounds Effect as Reinforcement on Mechanical and Flammability Properties of Polyester Composites

- Artificial Neural Network Modelling for Prediction of SNR Effected by Probe Properties on Ultrasonic Inspection of Austenitic Stainless Steel Weldments

- Calculation and 3D analyses of ERR in the band crack front contained in a rectangular plate made of multilayered material

- Improvement of fuel properties of biodiesel with bioadditive ethyl levulinate

- Properties of AlSi9Cu3 metal matrix micro and nano composites produced via stir casting

- Investigation of Antibacterial Properties of Ag Doped TiO2 Nanofibers Prepared by Electrospinning Process

- Modeling of Total Phenolic contents in Various Tea samples by Experimental Design Methods

- Nickel doping effect on the structural and optical properties of indium sulfide thin films by SILAR

- The effect mechanism of Ginnalin A as a homeopathic agent on various cancer cell lines

- Excitation functions of proton induced reactions of some radioisotopes used in medicine

- Oxide ionic conductivity and microstructures of Pr and Sm co-doped CeO2-based systems

- Rapid Synthesis of Metallic Reinforced in Situ Intermetallic Composites in Ti-Al-Nb System via Resistive Sintering

- Oxidation Behavior of NiCr/YSZ Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs)

- Clustering Analysis of Normal Strength Concretes Produced with Different Aggregate Types

- Magnetic Nano-Sized Solid Acid Catalyst Bearing Sulfonic Acid Groups for Biodiesel Synthesis

- The biological activities of Arabis alpina L. subsp. brevifolia (DC.) Cullen against food pathogens

- Humidity properties of Schiff base polymers

- Free Vibration Analysis of Fiber Metal Laminated Straight Beam

- Comparative study of in vitro antioxidant, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase activity of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) collected during different growth stages

- Isothermal Oxidation Behavior of Gadolinium Zirconate (Gd2Zr2O7) Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs) produced by Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition (EB-PVD) technique

- Optimization of Adsorption Parameters for Ultra-Fine Calcite Using a Box-Behnken Experimental Design

- The Microstructural Investigation of Vermiculite-Infiltrated Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition Thermal Barrier Coatings

- Modelling Porosity Permeability of Ceramic Tiles using Fuzzy Taguchi Method

- Experimental and theoretical study of a novel naphthoquinone Schiff base

- Physicochemical properties of heat treated sille stone for ceramic industry

- Sand Dune Characterization for Preparing Metallurgical Grade Silicon

- Catalytic Applications of Large Pore Sulfonic Acid-Functionalized SBA-15 Mesoporous Silica for Esterification

- One-photon Absorption Characterizations, Dipole Polarizabilities and Second Hyperpolarizabilities of Chlorophyll a and Crocin

- The Optical and Crystallite Characterization of Bilayer TiO2 Films Coated on Different ITO layers

- Topical Issue on Bond Activation

- Metal-mediated reactions towards the synthesis of a novel deaminolysed bisurea, dicarbamolyamine

- The structure of ortho-(trifluoromethyl)phenol in comparison to its homologues – A combined experimental and theoretical study

- Heterogeneous catalysis with encapsulated haem and other synthetic porphyrins: Harnessing the power of porphyrins for oxidation reactions

- Recent Advances on Mechanistic Studies on C–H Activation Catalyzed by Base Metals

- Reactions of the organoplatinum complex [Pt(cod) (neoSi)Cl] (neoSi = trimethylsilylmethyl) with the non-coordinating anions SbF6– and BPh4–

- Erratum

- Investigation on Two Compounds of O, O’-dithiophosphate Derivatives as Corrosion Inhibitors for Q235 Steel in Hydrochloric Acid Solution

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The effect of CuO modification for a TiO2 nanotube confined CeO2 catalyst on the catalytic combustion of butane

- The preparation and antibacterial activity of cellulose/ZnO composite: a review

- Linde Type A and nano magnetite/NaA zeolites: cytotoxicity and doxorubicin loading efficiency

- Performance and thermal decomposition analysis of foaming agent NPL-10 for use in heavy oil recovery by steam injection

- Spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, UV, 1H and 13C NMR) insights, electronic profiling and DFT computations on ({(E)-[3-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-1-phenylpropylidene] amino}oxy)(4-nitrophenyl)methanone, an imidazole-bearing anti-Candida agent

- A Simplistic Preliminary Assessment of Ginstling-Brounstein Model for Solid Spherical Particles in the Context of a Diffusion-Controlled Synthesis

- M-Polynomials And Topological Indices Of Zigzag And Rhombic Benzenoid Systems

- Photochemical Transformation of some 3-benzyloxy-2-(benzo[b]thiophen-2-yl)-4Hchromen-4-ones: A Remote Substituent Effect

- Dynamic Changes of Secondary Metabolites and Antioxidant Activity of Ligustrum lucidum During Fruit Growth

- Studies on the flammability of polypropylene/ammonium polyphosphate and montmorillonite by using the cone calorimeter test

- DSC, FT-IR, NIR, NIR-PCA and NIR-ANOVA for determination of chemical stability of diuretic drugs: impact of excipients

- Antioxidant and Hepatoprotective Effects of Methanolic Extracts of Zilla spinosa and Hammada elegans Against Carbon Tetrachlorideinduced Hepatotoxicity in Rats

- Prunus cerasifera Ehrh. fabricated ZnO nano falcates and its photocatalytic and dose dependent in vitro bio-activity

- Organic biocides hosted in layered double hydroxides: enhancing antimicrobial activity

- Experimental study on the regulation of the cholinergic pathway in renal macrophages by microRNA-132 to alleviate inflammatory response

- Synthesis, characterization, in-vitro antimicrobial properties, molecular docking and DFT studies of 3-{(E)-[(4,6-dimethylpyrimidin-2-yl)imino]methyl} naphthalen-2-ol and Heteroleptic Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Zn(II) complexes

- M-Polynomials and Topological Indices of Dominating David Derived Networks

- Human Health Risk Assessment of Trace Metals in Surface Water Due to Leachate from the Municipal Dumpsite by Pollution Index: A Case Study from Ndawuse River, Abuja, Nigeria

- Analysis of Bowel Diseases from Blood Serum by Autofluorescence and Atomic Force Microscopy Techniques

- Hydrographic parameters and distribution of dissolved Cu, Ni, Zn and nutrients near Jeddah desalination plant

- Relationships between diatoms and environmental variables in industrial water biotopes of Trzuskawica S.A. (Poland)

- Optimum Conversion of Major Ginsenoside Rb1 to Minor Ginsenoside Rg3(S) by Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Acid Hydrolysis Treatment

- Antioxidant, Anti-microbial Properties and Chemical Composition of Cumin Essential Oils Extracted by Three Methods

- Regulatory mechanism of ulinastatin on autophagy of macrophages and renal tubular epithelial cells

- Investigation of the sustained-release mechanism of hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose skeleton type Acipimox tablets

- Bio-accumulation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Grey Mangrove (Avicennia marina) along Arabian Gulf, Saudi Coast

- Dynamic Change of Secondary Metabolites and spectrum-effect relationship of Malus halliana Koehne flowers during blooming

- Lipids constituents from Gardenia aqualla Stapf & Hutch

- Effect of using microwaves for catalysts preparation on the catalytic acetalization of glycerol with furfural to obtain fuel additives

- Effect of Humic Acid on the Degradation of Methylene Blue by Peroxymonosulfate

- Serum containing drugs of Gua Lou Xie Bai decoction (GLXB-D) can inhibit TGF-β1-Induced Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in A549 Cells

- Antiulcer Activity of Different Extracts of Anvillea garcinii and Isolation of Two New Secondary Metabolites

- Analysis of Metabolites in Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz Dry Red Wines from Shanxi by 1H NMR Spectroscopy Combined with Pattern Recognition Analysis

- Can water temperature impact litter decomposition under pollution of copper and zinc mixture

- Released from ZrO2/SiO2 coating resveratrol inhibits senescence and oxidative stress of human adipose-derived stem cells (ASC)

- Validated thin-layer chromatographic method for alternative and simultaneous determination of two anti-gout agents in their fixed dose combinations

- Fast removal of pollutants from vehicle emissions during cold-start stage

- Review Article

- Catalytic activities of heterogeneous catalysts obtained by copolymerization of metal-containing 2-(acetoacetoxy)ethyl methacrylate

- Antibiotic Residue in the Aquatic Environment: Status in Africa

- Regular Articles

- Mercury fractionation in gypsum using temperature desorption and mass spectrometric detection

- Phytosynthetic Ag doped ZnO nanoparticles: Semiconducting green remediators

- Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Induced by SMAD4 Activation in Invasive Growth Hormone-Secreting Adenomas

- Physicochemical properties of stabilized sewage sludge admixtures by modified steel slag

- In Vitro Cytotoxic and Antiproliferative Activity of Cydonia oblonga flower petals, leaf and fruit pellet ethanolic extracts. Docking simulation of the active flavonoids on anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2

- Synthesis and Characterization of Pd exchanged MMT Clay for Mizoroki-Heck Reaction

- A new selective, and sensitive method for the determination of lixivaptan, a vasopressin 2 (V2)-receptor antagonist, in mouse plasma and its application in a pharmacokinetic study

- Anti-EGFL7 antibodies inhibit rat prolactinoma MMQ cells proliferation and PRL secretion

- Density functional theory calculations, vibration spectral analysis and molecular docking of the antimicrobial agent 6-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-ylmethyl)-5-ethyl-2-{[2-(morpholin-4-yl)ethyl] sulfanyl}pyrimidin-4(3H)-one

- Effect of Nano Zeolite on the Transformation of Cadmium Speciation and Its Uptake by Tobacco in Cadmium-contaminated Soil

- Effects and Mechanisms of Jinniu Capsule on Methamphetamine-Induced Conditioned Place Preference in Rats

- Calculating the Degree-based Topological Indices of Dendrimers

- Efficient optimization and mineralization of UV absorbers: A comparative investigation with Fenton and UV/H2O2

- Metabolites of Tryptophane and Phenylalanine as Markers of Small Bowel Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

- Adsorption and determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water through the aggregation of graphene oxide

- The role of NR2C2 in the prolactinomas

- Chromium removal from industrial wastewater using Phyllostachys pubescens biomass loaded Cu-S nanospheres

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Preparation of Calcium Fluoride using Phosphogypsum by Orthogonal Experiment

- The mechanism of antibacterial activity of corylifolinin against three clinical bacteria from Psoralen corylifolia L

- 2-formyl-3,6-bis(hydroxymethyl)phenyl benzoate in Electrochemical Dry Cell

- Electro-photocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin using calcium titanate

- Effect of Malus halliana Koehne Polysaccharides on Functional Constipation

- Structural Properties and Nonlinear Optical Responses of Halogenated Compounds: A DFT Investigation on Molecular Modelling

- DMFDMA catalyzed synthesis of 2-((Dimethylamino)methylene)-3,4-dihydro-9-arylacridin-1(2H)-ones and their derivatives: in-vitro antifungal, antibacterial and antioxidant evaluations

- Production of Methanol as a Fuel Energy from CO2 Present in Polluted Seawater - A Photocatalytic Outlook

- Study of different extraction methods on finger print and fatty acid of raw beef fat using fourier transform infrared and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- Determination of trace fluoroquinolones in water solutions and in medicinal preparations by conventional and synchronous fluorescence spectrometry

- Extraction and determination of flavonoids in Carthamus tinctorius

- Therapeutic Application of Zinc and Vanadium Complexes against Diabetes Mellitus a Coronary Disease: A review

- Study of calcined eggshell as potential catalyst for biodiesel formation using used cooking oil

- Manganese oxalates - structure-based Insights

- Topological Indices of H-Naphtalenic Nanosheet

- Long-Term Dissolution of Glass Fibers in Water Described by Dissolving Cylinder Zero-Order Kinetic Model: Mass Loss and Radius Reduction

- Topological study of the para-line graphs of certain pentacene via topological indices

- A brief insight into the prediction of water vapor transmissibility in highly impermeable hybrid nanocomposites based on bromobutyl/epichlorohydrin rubber blends

- Comparative sulfite assay by voltammetry using Pt electrodes, photometry and titrimetry: Application to cider, vinegar and sugar analysis

- MicroRNA delivery mediated by PEGylated polyethylenimine for prostate cancer therapy

- Reversible Fluorescent Turn-on Sensors for Fe3+ based on a Receptor Composed of Tri-oxygen Atoms of Amide Groups in Water

- Sonocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in aqueous solution using Fe-doped TiO2 nanoparticles under mechanical agitation

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction