Abstract

We successfully synthesized Pd@MMT clay using a cation exchange process. We characterized all the synthesized Pd@MMT clays using sophisticated analytical techniques before testing them as a heterogeneous catalyst for the Mizoroki - Heck reaction (mono and double). The highest yield of the Mizoroki-Heck reaction product was recovered using thermally stable and highly reactive Pd@ MMT-1 clay catalyst in the functionalized ionic liquid reaction medium. We successfully isolated 2-aryl-vinyl phosphonates (mono-Mizoroki-Heck reaction product) and 2,2-diaryl-vinylphosphonates (double-Mizoroki-Heck reaction product) using aryl halides and dialkyl vinyl phosphonates in higher yields. The low catalyst loading, easy recovery of reaction product and 8 times catalyst recycling are the major highlights of this proposed protocol.

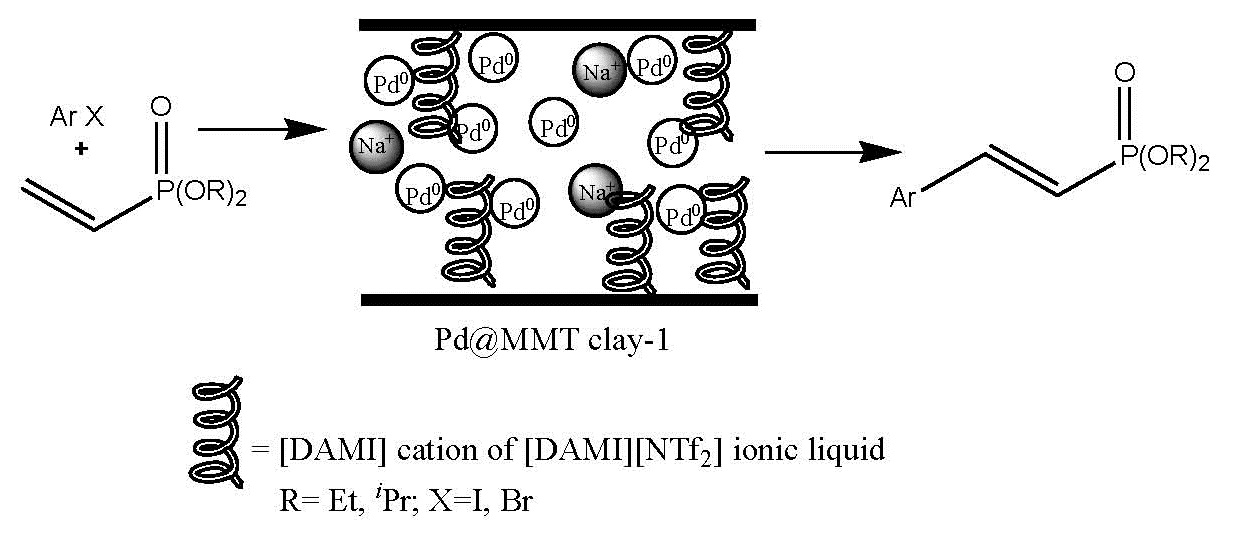

Graphical Abstract

1 Introduction

Palladium metal is considered one of the most well-investigated materials among the series of transition metals for C-C coupling reactions [1,2,3]. Several forms of palladium metal, such as Pd metal complex with carbenesand phosphines as well as palladium salts have been utilized as a catalyst [3,4,5]. Palladium metal was also supported on different organic and inorganic supports to make the Pd metal catalyst more active and stable in terms of air and moisture issues, substrate scope, catalyst leaching and catalyst loading. Recently, different synthetic protocols have been introduced to synthesize Pd nanoparticles (NPs) which utilize the advanced Physiochemical properties of nanoparticles such as high degree of dispersion in reaction mass and the large surface area [4,5, 6,7,8] when applying Pd NPs as nanocatalysts for different organic transformations. In some of the reports, the extraordinary nature of these Pd NPs has been recorded for different types of C-C coupling reactions like Suzuki, Mizoroki-Heck and Sonogashira reaction [6,7,8]. Although, Pd NPs appeared as an important form of Pd catalyst, unfortunately, they also suffer with some unique problems of nanoparticles like stability, agglomeration and uneven size distribution of Pd NPs during the chemical reaction. In some of the scientific reports, Pd NPs were supported on different organic/inorganic supports like polymer, ionic liquid, activated carbon, silica, MCM-41, clays. Al2O3 and Zeolite get agglomeration free and stable Pd NPs, but the curse of a costly starting material, tedious synthetic protocol and, most important, reproducibility of synthetic protocol collectively hurts the supported synthesis of Pd NPs [8,9,10,11,12].

Na-Montmorillonite clay (MMT) is one of the important materials which is used as a support for various transition metals, mainly because of its exceptional physiochemical properties such as high cation exchange capacity and good swelling properties [13]. Additionally, MMT supported catalytic systems also offer, a high degree of thermal stability, provides protection to metal against air/moisture, easy catalyst isolation and recycling. The interlayer spacing of aluminosilicates in MMT is filled with several Na+, K+ and Ca2+ ions, these ions are considered as exchangeable cations in MMT, which are mainly responsible for the metal ion exchange reaction [13,14,15]. MMT supported metal has been tested as a catalyst for several reactions like oxidation, reduction, transesterification and coupling reactions, but to achieve maximum metal exchange as well as high catalyst loading are still a challenge [13,14,15,16,17,18].

Ionic liquids (ILs) are organic salts that are liquid below 100°C and have received considerable attention as substitutes for volatile organic solvents. Since they are nonflammable, non-volatile and recyclable, they are classified as green solvents. Due to their amazing properties, such as outstanding solvating potential, thermal stability and their tunable properties by suitable choices of cations and anions, they are considered as a favorable reaction medium over conventional solvent systems for chemical synthesis [4]. ILs are mainly made up of cationic and anionic components that can be arranged to achieve a specific set of properties. In this context, the term “designer solvents” has been used to illustrate the potential of this environment-benign ILs in chemical transformations. Being designer solvents, they can be modified as per the specific requirement of the reaction conditions, therefore they also name as “task specific ILs (TSILs).” Since these liquids, can dissolve a series of transition metal complexes, they have been utilized as an alternative for conventional solvent systems in many transition metal complex catalyzed organic transformations to get enhanced reaction rates, selectivity and catalyst recycling with easy isolation of the reaction product [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. The present study is aimed to explore the application of ionic liquid as TSIL to avoid the use of a toxic base in the Mizoroki - Heck reaction.

In this paper, we are presenting the controlled synthesis of Pd NPs within the interlayer spacing of MMT followed by cation exchange method, where Pd metal (using tetraamminepalladium(II) chloride monohydrate as substrate) ions were exchanged by interlayer cations (Na+, K+ or Ca2+) of MMT. We utilized Pd@MMT clay as a catalyst for the Mizoroki - Heck reaction in TSILs (1,3- di(N, N-dimethylaminoethyl)-2-methylimidazolium bis (trifluoromethylsulfonyl) imide ([DAMI][NTf2])) to synthesize 2-aryl and 2,2-diary vinylphohonates. It is well documented that ionic liquid interacts very effectively with transition metal catalysts. In addition, we will also investigate the Pd@ MMT/ionic liquid recycling test. High reaction rate, base free reaction process, stable nano-catalytic system, low catalyst loading, easy product isolation and catalyst recycling are the most interesting features of this proposed protocol.

2 Experimental

All the reagent grade chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich and SD Fine chemicals. All the 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded with 400 MHz Bruker spectrometer with the CDCl3 solvent system. The internal standard for 1H and 13C NMR spectra were kept at 7.26 and 7.36 ppm respectively (supporting information). 31P NMR spectra of all the unknown compounds were recorded Varian 400 NMR spectrometer (85% H3PO4 as an external standard) (supporting information). The Na MMT was supplied from Southern Clay Product, Texas-USA with the registered product name Cloisiite Na and it was used for tetraamminepalladium(II) chloride monohydrate intercalation without going to any further purification of pretreatment process. The cation exchange capacity (CEC) of Na-montmorillonite was 92.6 mequiv/100 g [13,14,15]. Philips X’Pert MPD instruments were used to record all small and wide-angle X-Ray Powder Diffraction (XRD) data using an X-ray tube voltage of 30.0 kV and current of 15.0 mA, scan rate of 5/min and step size of 0.05. The fine powder of Pd@MMT clay was mixed with vacuum grease and fixed on the glass substrate. A flat surface was obtained by pressing the mixed powder between two flat glass sheets. The diffraction pattern was obtained after subtraction of the powder spectrum from the background of a glass substrate plus the vacuum grease.

The Pd@MMT clay material was characterized by TEM (Hitachi S-3700N). The TEM sample was prepared by mixing the Pd@MMT sample with epoxy resin distributed between two silicon wafer pieces at 50oC for 30 minutes. Cross section of TEM samples were pre-thinned mechanically followed by ion milling. Particle size distribution was determined once the original negative had been digitalized and expanded to 500 pixels per cm for more accurate resolution and measurement.

EDX spectra were measured with a Si(Li) EDS detector (Thermo Scientific) or an XFlash® SDD detector (Bruker), both having an active area of 10 mm2. A large-area SDD EDS detector (Bruker) capable of high-sensitivity detection has been used for some specific samples.

The specific surface area (BET) of the catalyst was determined on a Micrometrics Flowsorb III 2310 instrument. The samples were dried with nitrogen purging or in a vacuum applying elevated temperatures. We used P/P0 of 0,1, 0,2 and 0,3 as standard measurement points. The volume of gas adsorbed to the surface of the particles is measured at the boiling point of nitrogen (-196°C). The amount of adsorbed gas is correlated to the total surface area of the particles including pores in the surface. The calculation is based on the BET theory. Traditionally nitrogen is used as adsorbate gas. Gas adsorption also enables the determination of size and volume distribution of micropores (0.35 – 2.0 nm).

Fourier transform infrared spectrophotometer (FTIR) analysis of all the samples were studied with Bruker Tensor-27. Elemental analysis was conducted in a Perkin Elmer Optima 3300 XL. All the solid samples were prepared by using KBr pellets while liquid samples were prepared by using nujol as an internal reference.

ICP-OES (inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy) was applied to determine the metal Pd and phosphorus content. A sample for ICP-OES analysis was prepared by accurately weighing 2.00 g of Pd@MMT and placing in a pre-cleaned 100 mL volumetric flask. An optimized amount of extractant solution (10 mL Aqua Regia) was then added and the resulting mixture irradiated at the optimum sonication time of 120 min to guarantee maximum sample irradiation, and the volumetric flasks were kept stationary at selected positions in the bath with only four samples used for simultaneous sonication. The resulting supernatant liquid was separated from the solid phase by centrifugation at 2500 rpm for 15 min, after which diluted up to 40.0 g with Milli-Q water before going to ICP-OES analysis. 1,3-di (N, N-dimethylaminoethyl) -2-methylimidazolium bis (trifluoromethylsulfonyl) imide ([DAMI] [NTf2]) and 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium bis (trifluoromethylsulfonyl) imide ([Bmim] [NTf2]) were synthesized as per reported procedure [4 and 17].

2.1 Synthesis of Pd@MMT Clay

A perfectly cleaned and dried 250 mL round bottom flask was charged with the suspension of Na MMT clay (5 g) with 100 mL water. The aqueous solution of 50 mL of tetraamminepalladium (II) chloride monohydrate (6 mM) solution was added in dropwise manner into the homogeneous slurry of Na MMT clay within 2 hours by maintaining the pH of the solution at 5.5 (using 0.1N HCl). The combined reaction was stirred at 25-30°C for the next 24 hours to obtain a uniform dispersion. Later, [Pd (NH3)4] -MMT exchanged clay was stirred with NaBH4 (5 g) for the next 5 hours at room temperature. The color change from brown to black confirmed the complete reduction of Pd2+ to Pd0. Further, Pd exchanged clay was washed with double distilled water using centrifugation. Washing was stopped as soon as we got chloride free supernatant (monitored with silver nitrate solution). Finally, chloride free Pd exchanged clay was dried under lyophilizer for 12 hours. At last, we obtained free-flowing black colored powder as Pd@MMT-1 clay (4.8 g, 3w/w % Pd). In the same pattern, we also prepared Pd@MMT-2 clay (4.3 g, 1.01 w/w % Pd) using tetraamminepalladium(II) chloride monohydrate solution (3 mM) with 5 g Na MMT clay. pH of the above-mentioned reaction mass was also controlled by the addition 0.1 N HCl.

2.2 Experimental Procedure of Mono or Double Mizoroki-Heck Reaction

50 mL glass-made reaction vessel was charged with aryl halides and vinylphosphonate with Pd@MMT clay -1 or 2 catalysts in a solvent system with or without a base (as per Table 2, 3 and 4). The combined reaction mass was heated at the 80°C for one hour. After the completion of the reaction, the reaction product was, then, recovered with diethyl ether (5 x 2 mL) and further purified by column chromatography. Isolated ionic liquid immobilized Pd@ MMT-1 clay was further dried in high vacuum at 50oC for 0.5 hours to evaporate all the volatile impurities. After the vacuum treatment, all the reactants were added as per the above-mentioned protocol with ionic liquid immobilized Pd@MMT-1 clay to recycle the catalytic system.

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animals use.

3 Results and Discussion

Task-specific [DAMI][NTf2] ionic liquid was synthesized as per our previously reported procedure. We synthesized two different types of Pd@MMT clay 1 & 2, followed by mixing the neat Na-MMT clay with aqueous solution tetraamminepalladium(II) chloride monohydrate in acidic medium for 24 hours at room temperature to ensure complete exchange of palladium metal ion with the exchangeable cation of MMT clay. After the exchange, the Pd@MMT clay was washed several times deionized water and dried under lyophilizer. We obtained Pd@MMT clay-1 while mixing MMT clay with 6 mM aqueous solution of tetraamminepalladium(II) chloride monohydrate. Pd loading on MMT clay was determined by calculating the change between the concentrations of palladium metal ion in initial tetraamminepalladium(II) chloride monohydrate solution with respect to the mother liquor recovered after the filtration of Pd@MMT clay followed by inductively coupled plasma emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES). We obtained good palladium metal ion loading over Pd@MMT-1 clay (0.95% w/w Pd metal) in comparison with Pd@MMT-2 clay (0.51 % w/w Pd metal, obtained by mixing 3mM aqueous solution of tetraamminepalladium(II) chloride monohydrate with MMT clay).

The change in the basal spacing of Pd @MMT clay with respect to neat MMT clay was studied using small to medium angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) analysis (Figure 1, supporting information). In SAXS study, an increase in the basal spacing of neat MMT clay was (d001=12.95 Å) recorded after the intercalation of palladium metal ion within the interlayer spacing of MMT clay. After the intercalation, the basal spacing of Pd@MMT-1 clay was increased up to d001=15.86 Å. Such significant increase in d001 spacing of MMT clay confirms the presence of palladium metal ion between the interlayer spaces of MMT clay. Sharp 001 XRD peaks gave a clear indication of parallel arrangements of clay sheets and the uniform addition of Pd NPs (Figure 2 supporting information) [13,14,15]. Therefore, we can conclude the presence of an ordered lamellar structure of Pd metal loaded MMT with the face-to-face arrangement of MMT clay sheets. We obtained a small characteristic signal as a peak in XRD data of Pd@MMT clay which confirms the presence of Pd NPs in MMT clay. The XRD signals of Pd NPs appeared as sharp peaks near to 40, 46 and 68 degrees respectively, representing the (111), (200) and (220) Bragg reflection. The XRD pattern of Pd metal was found in good agreement of JCPDS standard (#05-0681) and confirmed the synthesis of Pd NPs within the interlayer spacing of MMT clay. Face-centered cubic (fcc) crystal structure was used to calculate the size of Pd NPs using peak broadening profile of (111) signal at 40° using the Scherrer equation. The calculated crystallite size of the Pd NPs was found in 6.5 nm size for Pd@MMT-1 clay and 8.75 nm size for Pd@MMT-2 clay. We also studied the effect of the ionic liquid on the basal spacing of MMT clay. The sign of an increase in basal spacing of Pd@MMT -2 clay was also noticed and it was found near to d001=14.15 Å.

The morphology of MMT clay with and without Pd metal exchange and the particle size of Pd NPs as well as the presence of Pd NPs within the interlayer spacing was further confirmed by performing the high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) (Figure 3 supporting information). We obtained the agglomeration free uniform distribution of Pd NPs within the interlayer spacing of MMT clay. In Pd@MMT-1 clay, the particle size of Pd was recorded near to 7.5 nm with a standard deviation of ± 0.15 nm while some increase in the particle size of Pd metal was observed near to 12.5 nm with a standard deviation of ± 0.21 nm with Pd@MMT-2 clay.

During the reaction, Pd@MMT clay was used as a catalyst with functionalized ionic liquid used as a reaction medium as well as an effective substitute of amine. Presence of functionalized ionic liquid with Pd@MMT clay creates a chance of cation exchange between the cationic part of ionic liquid with remaining unexchanged Na+ ions in the Pd@MMT clay (Figure 4 supporting information) [14, 15]. This type of exchange was confirmed by further SAXS analysis and FT IR analysis. The presence of characteristic bands near to 1650, 1543, 843 cm−1 both in [DAMI] [NTf2] ionic liquid and [DAMI]+ ion exchanged Pd@MMT clay confirmed the exchange of remaining Na+ ions with cations of [DAMI][NTf2] ionic liquid (Figure 5 supporting information). This exchange was also supported by SAXS analysis and d001 spacing was reaching up to 16.76 Å from 15.86 Å in Pd@MMT-1 clay. The same change in Pd@ MMT-2 clay was also recorded where the basal spacing has increased from 14.15 Å to 15.01 Å.

The textural properties of Na-MMT clay and Pd@ MMT clays represented them as mesoporous solid (Table 1, Figure 6).

Surface properties of Na-MMT clay and Pd@MMT clays.

| Samples | BET surface area (m2/g) | Average Pore size (nm) | Pore volume (cm3/g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Na-MMT | 385 | 3.48 | 0.362 |

| Pd@MMT clay-1 | 371 | 3.32 | 0.211 |

| Pd@MMT clay-2 | 379 | 3.39 | 0.209 |

The nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherm of neat MMT, Pd@MMT clay 1 and Pd@MMT clay 2 gave typical type IV with hysteresis loop at P/P0 ~ 0.4 to 0.9 (Figure 6 supporting information). This data reveals no change in the porous structure of Na-MMT clay even after the insertion of Pd NPs. A drop in the BET surface area and total pore volume after the intercalation Pd NPs was recorded mainly due to the capping of some pores with metal NPs. The data shows the development of adsorbent multipliers’ and weak adsorbate-adsorbent connections. The different shapes of the adsorption-desorption isotherms were due to the configuration and size distribution of Pd NPS. Absenteeism of any unexpected changes in the surface area and pore volume supported the no sign of agglomeration.

Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) was applied to understand the chemical composition of Pd@ MMT clay to better know the structure and homogeneity of prepared materials (Figure 7 supporting information). The presence of characteristic signals of Pd metal in EDS spectra confirmed the presence of Pd NPs. The XPS analysis of Pd metal in Pd@MMT clays gave two characteristic peaks for Pd 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 at 335.3 eV and 340.5 eV respectively (Figure 7 supporting information). This data confirmed the presence of well reduced Pd (0) NPs within the interlayer spacing of MMT clay. Heterogeneous nature of catalysts was examined by catalyst poising experiment (supporting information).

After the completion of the careful physiochemical analysis of Pd-MMT clay, we further used them as a catalyst for two very important reactions usingthe Mizoroki-Heck reaction.

3.1 Mizoroki-Heck Reaction with Pd@MMT Clay as Catalyst

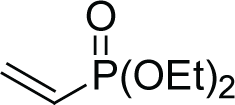

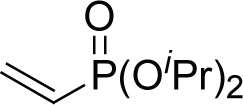

Alkenylphosphonates are considered an important chemical in medical science, material science and as polymer additives [18]. Various protocols such as the Suzuki - Miyaura coupling of boronic acids with vinylphosphonate, a Mizoroki-Heck reaction using vinylphosphonate with different aryl derivatives, aldehyde insertion into zirconacycle phosphonates and Olefin cross-metathesis have been reported using numerous transition metal catalytic systems under a toxic conventional solvent system [18,19,20,21,22]. The reaction is primarily suffering from catalyst recycling and the requirement of the toxic base for the successful completion of the reaction. In this report, we are using our well characterized Pd@MMT clay catalysts to improve the reaction kinetics of vinyl phosphonates synthesis followed by Mizoroki -Heck reaction. Also, we are exploring the synthesis of a unique double-Mizoroki-Heck reaction using our developed MMT supported Pd catalytic system.

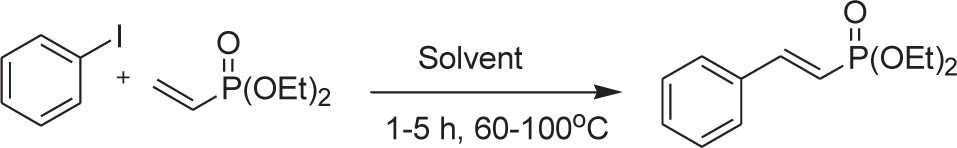

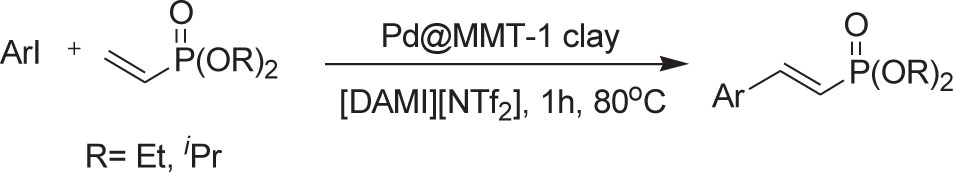

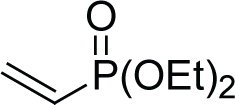

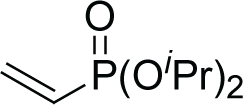

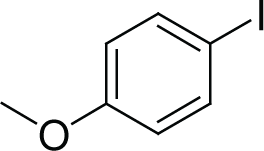

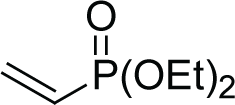

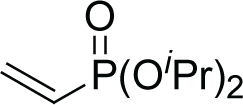

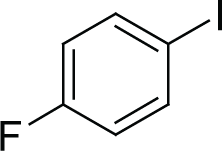

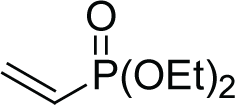

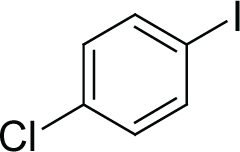

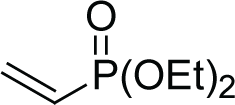

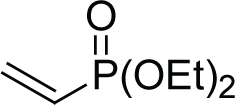

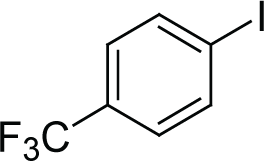

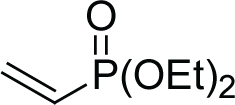

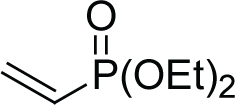

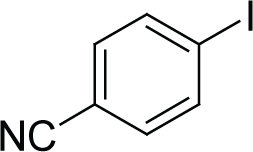

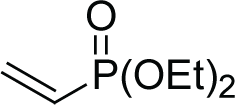

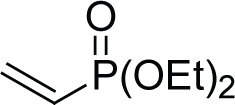

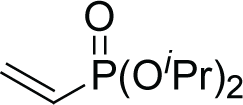

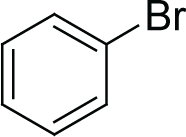

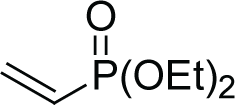

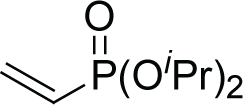

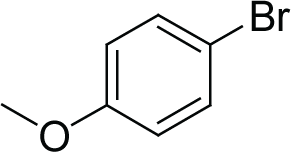

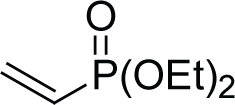

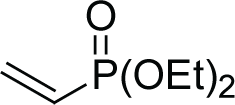

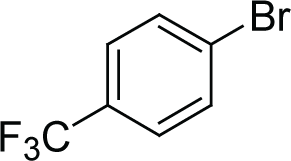

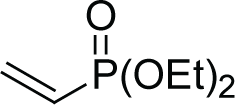

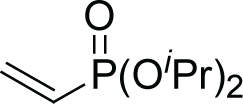

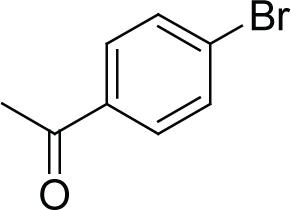

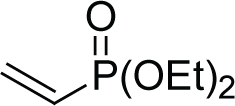

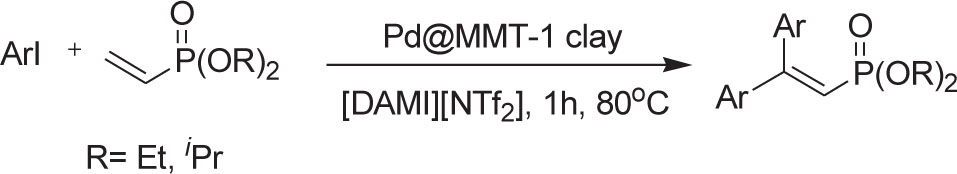

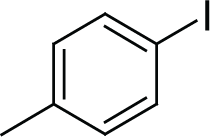

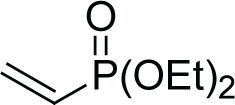

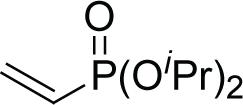

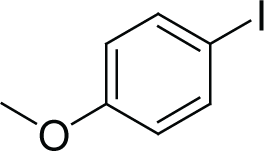

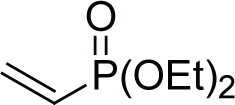

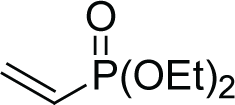

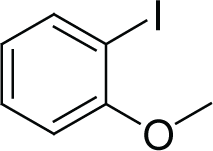

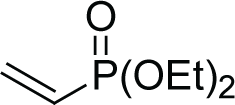

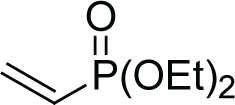

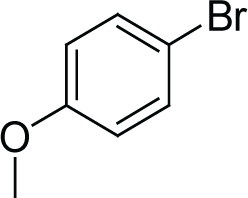

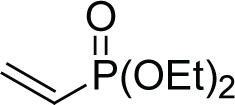

Initially, we allowed Pd @MMT clay 1 to catalyze a model Mizoroki-Heck reaction between iodobenzene and diethyl vinyl phosphonate under functionalized ionic liquid medium (instead of using the toxic conventional solvent system and toxic base) at 80oC for 1 hour (Scheme 1, Table 2). We successfully obtained the corresponding reaction product with good yield. The same reaction condition was also tested with Pd@MMT clay-2 catalyst unfortunately, lower yield was recorded due to low Pd metal loading (Table 2, entry 2).

Model Mizoroki-Heck reaction.

Reaction optimization of Mizoroki Heck reaction.

| Entry | Catalyst (0.01g) | SolvInent (0.150 g) | Base (1 mmol) | Time (h) | Temperature (°C) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Pd@MMT clay-1 | [DAMI][NTf2] | - | 1 | 80 | 92 |

| 2. | Pd@MMT clay-2 | [DAMI][NTf2] | - | 1 | 80 | 55 |

| 3. | Pd@MMT clay-1 (0.02g) | [DAMI][NTf2] | - | 1 | 80 | 92 |

| 4. | Pd@MMT clay-1 (0.005g) | [DAMI][NTf2] | - | 1 | 80 | 52 |

| 5. | Pd@MMT clay-1 | [DAMI][NTf2] (0.200 g) | - | 1 | 80 | 91 |

| 6. | Pd@MMT clay-1 | [DAMI][NTf2] (0.100 g) | - | 1 | 80 | 72 |

| 7. | Pd@MMT clay-1 | [DAMI][NTf2] | KOH | 1 | 80 | 90 |

| 8. | Pd@MMT clay-1 | [DAMI][NTf2] | K2CO3 | 1 | 80 | 87 |

| 9. | Pd@MMT clay-1 | [DAMI][NTf2] | iPr2NH | 1 | 80 | 91 |

| 10. | Pd@MMT clay-1 | [DAMI][NTf2] | Et3N | 1 | 80 | 90 |

| 11. | Pd@MMT clay-1 | [bmim][NTf2] | 1 | 80 | 35 | |

| 12. | Pd@MMT clay-1 | [bmim][NTf2] | iPr2NH | 1 | 80 | 73 |

| 13. | Pd@MMT clay-1 | [DAMI][NTf2] | - | 1 | 50 | 34 |

| 14. | Pd@MMT clay-1 | [DAMI][NTf2] | - | 1 | 100 | 91 |

| 15. | Pd@MMT clay-1 | [DAMI][NTf2] | - | 2 | 100 | 91 |

| 16. | Pd@MMT clay-1 | [DAMI][NTf2] | - | 30 | 100 | 42 |

| 17. | Pd@MMT clay-1 | DMF | iPr2NH | 1 | 80 | 66 |

| 18. | Pd@MMT clay-1 | THF | iPr2NH | 1 | 80 | 59 |

| 19. | Pd@MMT clay-1 | CH3CN | iPr2NH | 1 | 80 | 45 |

| 20. | Pd(NH3)4Cl2·H2O | [DAMI][NTf2] | - | 1 | 80 | 65 |

| 21. | Pd(OAc)2 | [DAMI][NTf2] | - | 1 | 80 | 61 |

| 22. | [DAMI][NTf2] | - | 1 | 80 | - |

No sign of drastic change in the yield of Mizoroki-Heck reaction was observed when elevating the reaction temperature or time and quantity of ionic liquid or catalyst. But, as expected, while lowering the reaction condition, a clear drop in reaction yield was recorded. Replacement of functionalized ionic liquid with a series of base and non-functionalized [bmim][NTf2] ionic liquid showed the importance of [DAMI][NTf2] ionic liquid which works as active bases (due to the presence of two -NH functional group) and effective reaction medium. We also received lower catalytic activity of conventional Pd catalysts over our developed Pd@MMT clay catalytic system in ionic liquid medium (Table 2, entry 20 and 21). No sign of reaction product was recorded in absence of Pd@MMT clay 1 catalyst. After reaction completion, the product was effortlessly isolated via diethyl ether extraction and further purified using column chromatography. We successfully recycled our ionic liquid immobilized Pd@MMT-1 clay up 8 cycles without showing any significant loss in catalytic activity in terms of reaction yield. Surprisingly, no signature of catalyst leaching was recorded while performing a filtration test during recycling experiments. All the solid material was isolated with 0.45 mm polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) filter and recovered liquid was mixed with the reactants of the model Mizoroki heck reaction. No product formation was recorded during this reaction which confirmed the zero leaching of Pd metal from MMT clay. These filtration experiments were also supported by ICP-OES analysis of above-mentioned filtrate, where no signal from Pd metal was received. A sign of agglomeration and low reaction yield was recorded in TEM image analysis after 8 times recycling of Pd@MMT clay-1 catalyst (Figure 3 and 8 supporting information). Due to agglomeration, particle size increase in Pd NPs was observed from 7.5 nm to 19.5 nm (with a standard deviation of ± 0.75 nm). In some of the reports, the formation of palladium black was reported due to high reaction temperature [1,2,3]. In our case, no such observation was found mainly due to the extended thermal stability of Pd NPs because of thermally stable MMT clay.

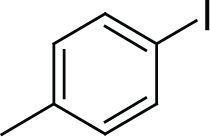

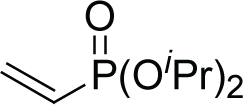

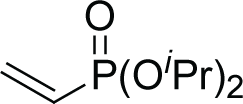

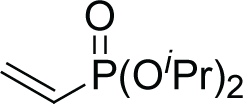

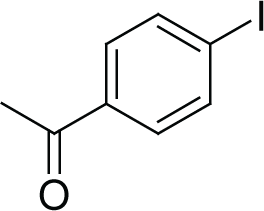

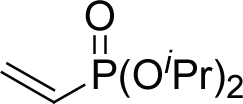

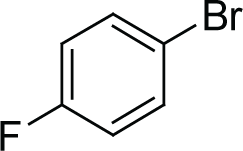

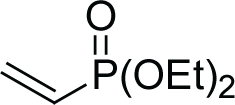

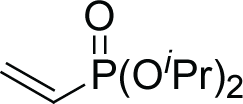

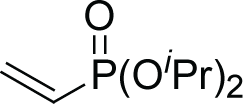

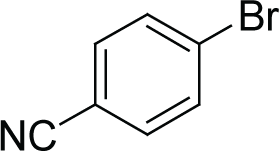

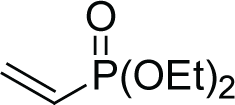

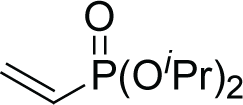

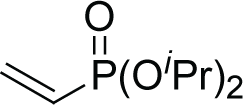

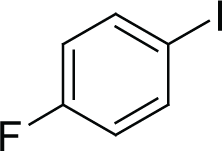

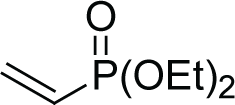

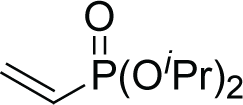

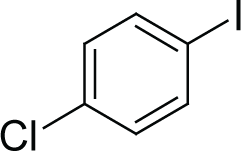

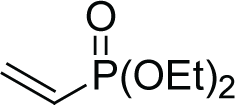

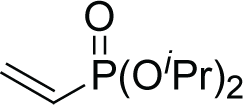

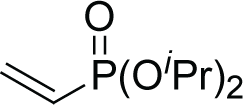

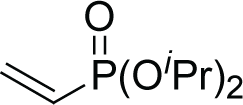

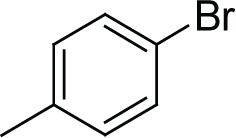

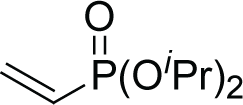

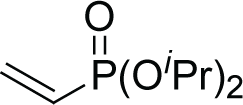

We applied the optimized reaction conditions for the variance of aryl halides and with different types of dialkylvinylphophonates. All the results were summarized Table 3, Scheme 2.

Mono Mizoroki-Heck reaction.

Pd@MMT-1 clay catalyzed mono Mizoroki-Heck reaction.

| Entry | Aryl halide (1mmol) | Phosphonate (2mmol) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. |  |  | 89 |

| 2. |  | 83 | |

| 3. |  |  | 86 |

| 4. |  | 81 | |

| 5. |  |  | 92 |

| 6. |  | 91 | |

| 7. |  |  | 91 |

| 8. |  | 93 | |

| 9. |  |  | 84 |

| 10. |  | 86 | |

| 11. |  |  | 87 |

| 12. |  | 91 | |

| 13. |  |  | 92 |

| 14. |  | 91 | |

| 15. |  |  | 86 |

| 16. |  | 88 | |

| 17. |  |  | 85 |

| 18. |  | 83 | |

| 19. |  |  | 66 |

| 20. |  | 67 | |

| 21. |  |  | 59 |

| 22. |  | 55 | |

| 23. |  |  | 70 |

| 24. |  | 69 | |

| 25. |  |  | 70 |

| 26. |  | 76 | |

| 27. |  |  | 76 |

| 28, |  | 77 | |

| 29., |  |  | 73 |

| 30. |  | 80 | |

| 31. |  |  | 74 |

| 32. |  | 75 | |

| 33. |  |  | 62 |

| 34. |  | 63 |

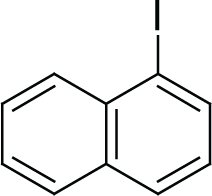

We tested a variety of aryl iodide (electron rich and electron poor) with two different types of vinyl phosphonate derivatives. We obtained good to excellent yield in all cases. Surprisingly, lowering of reaction yield was not reported with sterically hindered aryl halides (Table 3, entry 15-18). We easily performed typical oxidative addition of aryl bromide derivatives with MMT supported Pd metal without increasing the reaction temperature, reaction time and catalyst loading (Table 3, entry 19-30). This outcome represented the high catalytic performance of Pd@MMT -1 clay catalyst in the ionic liquid medium. We obtain the slow reaction rate with electron-rich aryl bromide derivatives than electron deficient composition. The presence of steric effect on aryl bromide derivatives as low reaction yield was recorded in their corresponding reaction products (Table 3, entry 31-34.).

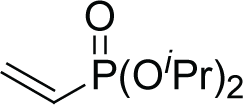

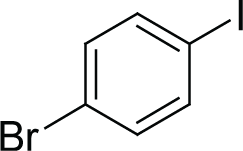

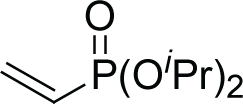

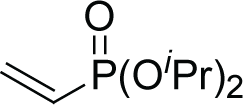

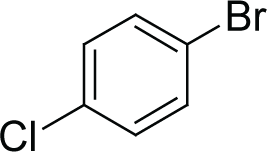

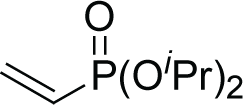

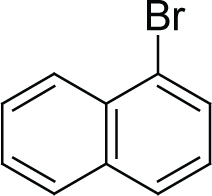

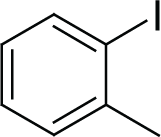

3.2 Double Mizoroki-Heck Reaction

In our study, we also extended the application of Pd@ MMT-1 clay catalysts for double-Mizoroki-Heck reaction while changing the limiting reagent from aryl halides to vinyl phosphonates (Scheme 3, Table 4, Entry 1-14). We obtained the corresponding double-Mizoroki-Heck reaction products with average to good yield. A series of electron rich and electron poor aryl halides were easily converted to their reaction products (Table 4, Entry 1-10).

Double Mizoroki-Heck reaction.

Pd@MMT-1 clay catalyzed double Mizoroki-Heck reaction.

| Entry | Aryl halide (2 mmol) | Phosphonate (1 mmol) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. |  |  | 72 |

| 2. |  | 66 | |

| 3. |  |  | 69 |

| 4. |  | 64 | |

| 5. |  |  | 75 |

| 6. |  | 74 | |

| 7. |  |  | 74 |

| 8. |  | 76 | |

| 9. |  |  | 70 |

| 10. |  | 74 | |

| 11. |  |  | 75 |

| 12. |  | 74 | |

| 13. |  |  | 75 |

| 14. |  | 74 | |

| 15. |  |  | 75 |

| 16. |  | 74 |

Sterically hindered aryl iodides were easily converted to 2, 2,-diary vinyl phosphonates with good yields (Table 4, entry 11-12). This result confirmed no effect of steric hindrance on double Mizoroki-Heck reaction. In addition, brominated aryl halides were allowed to react with vinyl phosphonates without changing any reaction condition via double Mizoroki-Heck reaction and their matching reaction products were nicely isolated in good yield.

4 Conclusions

The cation exchanged method was used to prepare two different types of Pd@MMT clays with different Pd loading. All the catalysts were properly analyzed through advanced analytical techniques including FTIR, ICP-OES, SAXS, XRD, FTIR, N2 physisorption, EDS and TEM. High Pd NP loading, agglomeration free, narrow size distributed Pd NPs were reported in Pd@MMT-1 clay over Pd@MMT-2 clay. A high degree of mesoporous nature was also calculated in Pd@MMT-1 clay. Here, we also prepared two types of functional and nonfunctional ionic liquids to use them as an active solvent system in our reaction. In our report, we also investigated the benefits ionic liquids, other than reaction medium, and concluded that the exchange of ionic liquid cations with the remaining Na+ cations of Pd@MMT clay has expanded the interlayer spacing to accommodate better reaction between Pd NPs and reactants. Such feature of ionic liquid found responsible for the highly selective Mizoroki-Heck reaction. Pd@MMT clay under catalyst recycling experiments was found highly active under thermal heating and successfully recycled the Pd@MMT-1 clay catalyst up to 8 runs. Surprisingly, no catalysts leaching was recorded during catalysts recycling experiments. Along with mono Mizoroki-Heck reaction, we also obtained double Mizoroki-Heck reaction with a good reaction yield without increasing reaction time/temperature and catalyst loading. In addition, we developed an operationally simple catalytic recycling system for Mizoroski-Heck reaction without using any toxic ligands and harmful conventional solvent systems. Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Pagliaro M., Pandarus V., Ciriminna R., Béland F., Demma Carà P., Heterogeneous versus homogeneous palladium catalysts for cross-coupling reactions, ChemCatChem, 2012, 4(4), 432-445.10.1002/cctc.201100422Search in Google Scholar

[2] Karimi B., Mansouri F., Mirzaei H.M., Recent applications of magnetically recoverable nanocatalysts in C-C and C-X coupling reactions, ChemCatChem, 2015, 7(12), 1736-1789.10.1002/cctc.201403057Search in Google Scholar

[3] Dong Z., Ye Z., Reusable, highly active heterogeneous palladium catalyst by convenient self-encapsulation crosslinking polymerization for multiple carbon-carbon crosscoupling reactions at ppm to ppb palladium loadings, Adv. Synth. Catal., 2014, 356(16), 3401-3414.10.1002/adsc.201400520Search in Google Scholar

[4] Upadhyay P.R., Srivastava V., Recyclable graphene-supported palladium nanocomposites for Suzuki coupling reaction, Green Process, Synth., 2016, 5, 123-129.10.1515/gps-2015-0112Search in Google Scholar

[5] Balanta A., Godard C., Claver C., Pd nanoparticles for C-C coupling reactions, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2011, 40(10), 4973-4985.10.1039/c1cs15195aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Kumar B.S., Anbarasan R., Amali A.J., Pitchumani K., Isolable C@Fe3O4 nanospheres supported cubical Pd nanoparticles as reusable catalysts for stille and mizoroki-Heck coupling reactions, Tetrahedron Lett., 2017, 58(33), 3276-3282.10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.07.025Search in Google Scholar

[7] Taladriz-Blanco P., Hérves P., Pérez-Juste J., Supported Pd nanoparticles for carbon–carbon coupling reactions, Top. Catal., 2013, 56(13), 1154-1170.10.1007/s11244-013-0082-6Search in Google Scholar

[8] Phan N.T.S., Van Der Sluys M., Jones C.W., On the nature of the active species in palladium catalyzed mizoroki–Heck and suzuki–miyaura couplings – homogeneous or heterogeneous catalysis, A critical review, Adv. Synth. Catal., 2006, 348(6), 609-679.10.1002/adsc.200505473Search in Google Scholar

[9] Chen S.-Y., Attanatho L., Mochizuki T., Zheng Q., Toba M., Yoshimura Y., Somwongsa P., Lao-Ubol S., Influences of the support property and Pd loading on activity of mesoporous silica-supported Pd catalysts in partial hydrogenation of palm biodiesel fuel, Adv. Porous Mater., 2016, 4(3), 230-237.10.1166/apm.2016.1116Search in Google Scholar

[10] Wang J., Li Y., Li P., Song G., Polymerized functional ionic liquid supported Pd nanoparticle catalyst for reductive homocoupling of aryl halides, Monatshefte für Chemie - Chemical Monthly, 2013, 144(8), 1159-1163.10.1007/s00706-013-0925-7Search in Google Scholar

[11] Yamada Y.M.A., Takeda K., Takahashi H., Ikegami S., An assembled complex of palladium and non-cross-linked amphiphilic polymer: A highly active and recyclable catalyst for the suzuki-miyaura reaction, Org. Lett., 2002, 4(20), 3371-3374.10.1021/ol0264612Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Li X., Zhou F., Wang A., Wang L., Wang Y., Hydrodesulfurization of dibenzothiophene over MCM-41-supported Pd and Pt catalysts, Energy Fuels, 2012, 26(8), 4671-4679.10.1021/ef300690sSearch in Google Scholar

[13] Upadhyay P.R., Srivastava V., Clays: An encouraging catalytic support, Curr. Catal., 2016, 5(3), 162-181.10.2174/2211544705666160624082343Search in Google Scholar

[14] Srivastava V., Ru-exchanged MMT clay with functionalized ionic liquid for selective hydrogenation of CO2 to formic acid, Catal. Lett., 2014, 144(12), 2221-2226.10.1007/s10562-014-1392-4Search in Google Scholar

[15] Upadhyay P., Srivastava V., Ruthenium nanoparticle-intercalated montmorillonite clay for solvent-free alkene hydrogenation reaction, RSC Adv., 2015, 5(1), 740-745.10.1039/C4RA12324GSearch in Google Scholar

[16] Patil M.R., Kapdi A.R., A V.K., A recyclable supramolecular-ruthenium catalyst for the selective aerobic oxidation of alcohols on water: Application to total synthesis of Brittonin A, ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng., 2018.10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b03448Search in Google Scholar

[17] Upadhyay P.R., Srivastava V., Selective hydrogenation of CO2 gas to formic acid over nanostructured Ru-TiO2 catalysts, RSC Adv., 2016, 6(48), 42297-42306.10.1039/C6RA03660KSearch in Google Scholar

[18] Nagaoka Y., Carbon-carbon bond formation based on alkenylphosphonates, Yakugaku Zasshi, 2001, 121(11), 771-779.10.1248/yakushi.121.771Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Baird L.J., Colomban C., Turner C., Teesdale-Spittle P.H., Harvey J.E., Alkenylphosphonates: Unexpected products from reactions of methyl 2-[(diethoxyphosphoryl)methyl]benzoate under Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons conditions, Org. Biomol. Chem., 2011, 9(12), 4432-4435.10.1039/c1ob05506bSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Lee S.Y., Lee B.S., Lee C.-W., Oh D.Y., Synthesis of 4-oxo-2-alkenylphosphonates via nitrile oxide cycloaddition: γ-Acylation of allylic phosphonates, J. Org. Chem., 2000, 65(1), 256-257.10.1021/jo991261ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Kabalka G.W., Guchhait S.K., Synthesis of (E)- and (Z)-alkenylphosphonates using vinylboronates, Org. Lett., 2003, 5(5), 729-731.10.1021/ol027515aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Vinokurov N., Michrowska A. Szmigielska A., Drzazga Z., Wójciuk G., Demchuk O.M., Grela K., Pietrusiewicz K.M., Butenschön H., Homo- and cross-olefin metathesis coupling of vinylphosphane oxides and electron-poor alkenes: Access to P-stereogenic dienophiles, Adv. Synth. Catal., 2006, 348(7-8), 931-938.10.1002/adsc.200505463Search in Google Scholar

© 2018 Vivek Srivastava et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The effect of CuO modification for a TiO2 nanotube confined CeO2 catalyst on the catalytic combustion of butane

- The preparation and antibacterial activity of cellulose/ZnO composite: a review

- Linde Type A and nano magnetite/NaA zeolites: cytotoxicity and doxorubicin loading efficiency

- Performance and thermal decomposition analysis of foaming agent NPL-10 for use in heavy oil recovery by steam injection

- Spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, UV, 1H and 13C NMR) insights, electronic profiling and DFT computations on ({(E)-[3-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-1-phenylpropylidene] amino}oxy)(4-nitrophenyl)methanone, an imidazole-bearing anti-Candida agent

- A Simplistic Preliminary Assessment of Ginstling-Brounstein Model for Solid Spherical Particles in the Context of a Diffusion-Controlled Synthesis

- M-Polynomials And Topological Indices Of Zigzag And Rhombic Benzenoid Systems

- Photochemical Transformation of some 3-benzyloxy-2-(benzo[b]thiophen-2-yl)-4Hchromen-4-ones: A Remote Substituent Effect

- Dynamic Changes of Secondary Metabolites and Antioxidant Activity of Ligustrum lucidum During Fruit Growth

- Studies on the flammability of polypropylene/ammonium polyphosphate and montmorillonite by using the cone calorimeter test

- DSC, FT-IR, NIR, NIR-PCA and NIR-ANOVA for determination of chemical stability of diuretic drugs: impact of excipients

- Antioxidant and Hepatoprotective Effects of Methanolic Extracts of Zilla spinosa and Hammada elegans Against Carbon Tetrachlorideinduced Hepatotoxicity in Rats

- Prunus cerasifera Ehrh. fabricated ZnO nano falcates and its photocatalytic and dose dependent in vitro bio-activity

- Organic biocides hosted in layered double hydroxides: enhancing antimicrobial activity

- Experimental study on the regulation of the cholinergic pathway in renal macrophages by microRNA-132 to alleviate inflammatory response

- Synthesis, characterization, in-vitro antimicrobial properties, molecular docking and DFT studies of 3-{(E)-[(4,6-dimethylpyrimidin-2-yl)imino]methyl} naphthalen-2-ol and Heteroleptic Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Zn(II) complexes

- M-Polynomials and Topological Indices of Dominating David Derived Networks

- Human Health Risk Assessment of Trace Metals in Surface Water Due to Leachate from the Municipal Dumpsite by Pollution Index: A Case Study from Ndawuse River, Abuja, Nigeria

- Analysis of Bowel Diseases from Blood Serum by Autofluorescence and Atomic Force Microscopy Techniques

- Hydrographic parameters and distribution of dissolved Cu, Ni, Zn and nutrients near Jeddah desalination plant

- Relationships between diatoms and environmental variables in industrial water biotopes of Trzuskawica S.A. (Poland)

- Optimum Conversion of Major Ginsenoside Rb1 to Minor Ginsenoside Rg3(S) by Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Acid Hydrolysis Treatment

- Antioxidant, Anti-microbial Properties and Chemical Composition of Cumin Essential Oils Extracted by Three Methods

- Regulatory mechanism of ulinastatin on autophagy of macrophages and renal tubular epithelial cells

- Investigation of the sustained-release mechanism of hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose skeleton type Acipimox tablets

- Bio-accumulation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Grey Mangrove (Avicennia marina) along Arabian Gulf, Saudi Coast

- Dynamic Change of Secondary Metabolites and spectrum-effect relationship of Malus halliana Koehne flowers during blooming

- Lipids constituents from Gardenia aqualla Stapf & Hutch

- Effect of using microwaves for catalysts preparation on the catalytic acetalization of glycerol with furfural to obtain fuel additives

- Effect of Humic Acid on the Degradation of Methylene Blue by Peroxymonosulfate

- Serum containing drugs of Gua Lou Xie Bai decoction (GLXB-D) can inhibit TGF-β1-Induced Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in A549 Cells

- Antiulcer Activity of Different Extracts of Anvillea garcinii and Isolation of Two New Secondary Metabolites

- Analysis of Metabolites in Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz Dry Red Wines from Shanxi by 1H NMR Spectroscopy Combined with Pattern Recognition Analysis

- Can water temperature impact litter decomposition under pollution of copper and zinc mixture

- Released from ZrO2/SiO2 coating resveratrol inhibits senescence and oxidative stress of human adipose-derived stem cells (ASC)

- Validated thin-layer chromatographic method for alternative and simultaneous determination of two anti-gout agents in their fixed dose combinations

- Fast removal of pollutants from vehicle emissions during cold-start stage

- Review Article

- Catalytic activities of heterogeneous catalysts obtained by copolymerization of metal-containing 2-(acetoacetoxy)ethyl methacrylate

- Antibiotic Residue in the Aquatic Environment: Status in Africa

- Regular Articles

- Mercury fractionation in gypsum using temperature desorption and mass spectrometric detection

- Phytosynthetic Ag doped ZnO nanoparticles: Semiconducting green remediators

- Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Induced by SMAD4 Activation in Invasive Growth Hormone-Secreting Adenomas

- Physicochemical properties of stabilized sewage sludge admixtures by modified steel slag

- In Vitro Cytotoxic and Antiproliferative Activity of Cydonia oblonga flower petals, leaf and fruit pellet ethanolic extracts. Docking simulation of the active flavonoids on anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2

- Synthesis and Characterization of Pd exchanged MMT Clay for Mizoroki-Heck Reaction

- A new selective, and sensitive method for the determination of lixivaptan, a vasopressin 2 (V2)-receptor antagonist, in mouse plasma and its application in a pharmacokinetic study

- Anti-EGFL7 antibodies inhibit rat prolactinoma MMQ cells proliferation and PRL secretion

- Density functional theory calculations, vibration spectral analysis and molecular docking of the antimicrobial agent 6-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-ylmethyl)-5-ethyl-2-{[2-(morpholin-4-yl)ethyl] sulfanyl}pyrimidin-4(3H)-one

- Effect of Nano Zeolite on the Transformation of Cadmium Speciation and Its Uptake by Tobacco in Cadmium-contaminated Soil

- Effects and Mechanisms of Jinniu Capsule on Methamphetamine-Induced Conditioned Place Preference in Rats

- Calculating the Degree-based Topological Indices of Dendrimers

- Efficient optimization and mineralization of UV absorbers: A comparative investigation with Fenton and UV/H2O2

- Metabolites of Tryptophane and Phenylalanine as Markers of Small Bowel Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

- Adsorption and determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water through the aggregation of graphene oxide

- The role of NR2C2 in the prolactinomas

- Chromium removal from industrial wastewater using Phyllostachys pubescens biomass loaded Cu-S nanospheres

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Preparation of Calcium Fluoride using Phosphogypsum by Orthogonal Experiment

- The mechanism of antibacterial activity of corylifolinin against three clinical bacteria from Psoralen corylifolia L

- 2-formyl-3,6-bis(hydroxymethyl)phenyl benzoate in Electrochemical Dry Cell

- Electro-photocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin using calcium titanate

- Effect of Malus halliana Koehne Polysaccharides on Functional Constipation

- Structural Properties and Nonlinear Optical Responses of Halogenated Compounds: A DFT Investigation on Molecular Modelling

- DMFDMA catalyzed synthesis of 2-((Dimethylamino)methylene)-3,4-dihydro-9-arylacridin-1(2H)-ones and their derivatives: in-vitro antifungal, antibacterial and antioxidant evaluations

- Production of Methanol as a Fuel Energy from CO2 Present in Polluted Seawater - A Photocatalytic Outlook

- Study of different extraction methods on finger print and fatty acid of raw beef fat using fourier transform infrared and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- Determination of trace fluoroquinolones in water solutions and in medicinal preparations by conventional and synchronous fluorescence spectrometry

- Extraction and determination of flavonoids in Carthamus tinctorius

- Therapeutic Application of Zinc and Vanadium Complexes against Diabetes Mellitus a Coronary Disease: A review

- Study of calcined eggshell as potential catalyst for biodiesel formation using used cooking oil

- Manganese oxalates - structure-based Insights

- Topological Indices of H-Naphtalenic Nanosheet

- Long-Term Dissolution of Glass Fibers in Water Described by Dissolving Cylinder Zero-Order Kinetic Model: Mass Loss and Radius Reduction

- Topological study of the para-line graphs of certain pentacene via topological indices

- A brief insight into the prediction of water vapor transmissibility in highly impermeable hybrid nanocomposites based on bromobutyl/epichlorohydrin rubber blends

- Comparative sulfite assay by voltammetry using Pt electrodes, photometry and titrimetry: Application to cider, vinegar and sugar analysis

- MicroRNA delivery mediated by PEGylated polyethylenimine for prostate cancer therapy

- Reversible Fluorescent Turn-on Sensors for Fe3+ based on a Receptor Composed of Tri-oxygen Atoms of Amide Groups in Water

- Sonocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in aqueous solution using Fe-doped TiO2 nanoparticles under mechanical agitation

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Production and Analysis of Recycled Ammonium Perrhenate from CMSX-4 superalloys

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- New phosphorus biofertilizers from renewable raw materials in the aspect of cadmium and lead contents in soil and plants

- Survey of content of cadmium, calcium, chromium, copper, iron, lead, magnesium, manganese, mercury, sodium and zinc in chamomile and green tea leaves by electrothermal or flame atomizer atomic absorption spectrometry

- Biogas digestate – benefits and risks for soil fertility and crop quality – an evaluation of grain maize response

- A numerical analysis of heat transfer in a cross-current heat exchanger with controlled and newly designed air flows

- Freshwater green macroalgae as a biosorbent of Cr(III) ions

- The main influencing factors of soil mechanical characteristics of the gravity erosion environment in the dry-hot valley of Jinsha river

- Free amino acids in Viola tricolor in relation to different habitat conditions

- The influence of filler amount on selected properties of new experimental resin dental composite

- Effect of poultry wastewater irrigation on nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon contents in farmland soil

- Response of spring wheat to NPK and S fertilization. The content and uptake of macronutrients and the value of ionic ratios

- The Effect of Macroalgal Extracts and Near Infrared Radiation on Germination of Soybean Seedlings: Preliminary Research Results

- Content of Zn, Cd and Pb in purple moor-grass in soils heavily contaminated with heavy metals around a zinc and lead ore tailing landfill

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Synthesis of (±)-3,4-dimethoxybenzyl-4-methyloctanoate as a novel internal standard for capsinoid determination by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS(QTOF)

- Repellent activity of monoterpenoid esters with neurotransmitter amino acids against yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti

- Effect of Flammulina velutipes (golden needle mushroom, eno-kitake) polysaccharides on constipation

- Bioassay-directed fractionation of a blood coagulation factor Xa inhibitor, betulinic acid from Lycopus lucidus

- Antifungal and repellent activities of the essential oils from three aromatic herbs from western Himalaya

- Chemical composition and microbiological evaluation of essential oil from Hyssopus officinalis L. with white and pink flowers

- Bioassay-guided isolation and identification of Aedes aegypti larvicidal and biting deterrent compounds from Veratrum lobelianum

- α-Terpineol, a natural monoterpene: A review of its biological properties

- Utility of essential oils for development of host-based lures for Xyleborus glabratus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae), vector of laurel wilt

- Phenolic composition and antioxidant potential of different organs of Kazakh Crataegus almaatensis Pojark: A comparison with the European Crataegus oxyacantha L. flowers

- Isolation of eudesmane type sesquiterpene ketone from Prangos heyniae H.Duman & M.F.Watson essential oil and mosquitocidal activity of the essential oils

- Comparative analysis of the polyphenols profiles and the antioxidant and cytotoxicity properties of various blue honeysuckle varieties

- Special Issue on ICCESEN 2017

- Modelling world energy security data from multinomial distribution by generalized linear model under different cumulative link functions

- Pine Cone and Boron Compounds Effect as Reinforcement on Mechanical and Flammability Properties of Polyester Composites

- Artificial Neural Network Modelling for Prediction of SNR Effected by Probe Properties on Ultrasonic Inspection of Austenitic Stainless Steel Weldments

- Calculation and 3D analyses of ERR in the band crack front contained in a rectangular plate made of multilayered material

- Improvement of fuel properties of biodiesel with bioadditive ethyl levulinate

- Properties of AlSi9Cu3 metal matrix micro and nano composites produced via stir casting

- Investigation of Antibacterial Properties of Ag Doped TiO2 Nanofibers Prepared by Electrospinning Process

- Modeling of Total Phenolic contents in Various Tea samples by Experimental Design Methods

- Nickel doping effect on the structural and optical properties of indium sulfide thin films by SILAR

- The effect mechanism of Ginnalin A as a homeopathic agent on various cancer cell lines

- Excitation functions of proton induced reactions of some radioisotopes used in medicine

- Oxide ionic conductivity and microstructures of Pr and Sm co-doped CeO2-based systems

- Rapid Synthesis of Metallic Reinforced in Situ Intermetallic Composites in Ti-Al-Nb System via Resistive Sintering

- Oxidation Behavior of NiCr/YSZ Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs)

- Clustering Analysis of Normal Strength Concretes Produced with Different Aggregate Types

- Magnetic Nano-Sized Solid Acid Catalyst Bearing Sulfonic Acid Groups for Biodiesel Synthesis

- The biological activities of Arabis alpina L. subsp. brevifolia (DC.) Cullen against food pathogens

- Humidity properties of Schiff base polymers

- Free Vibration Analysis of Fiber Metal Laminated Straight Beam

- Comparative study of in vitro antioxidant, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase activity of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) collected during different growth stages

- Isothermal Oxidation Behavior of Gadolinium Zirconate (Gd2Zr2O7) Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs) produced by Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition (EB-PVD) technique

- Optimization of Adsorption Parameters for Ultra-Fine Calcite Using a Box-Behnken Experimental Design

- The Microstructural Investigation of Vermiculite-Infiltrated Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition Thermal Barrier Coatings

- Modelling Porosity Permeability of Ceramic Tiles using Fuzzy Taguchi Method

- Experimental and theoretical study of a novel naphthoquinone Schiff base

- Physicochemical properties of heat treated sille stone for ceramic industry

- Sand Dune Characterization for Preparing Metallurgical Grade Silicon

- Catalytic Applications of Large Pore Sulfonic Acid-Functionalized SBA-15 Mesoporous Silica for Esterification

- One-photon Absorption Characterizations, Dipole Polarizabilities and Second Hyperpolarizabilities of Chlorophyll a and Crocin

- The Optical and Crystallite Characterization of Bilayer TiO2 Films Coated on Different ITO layers

- Topical Issue on Bond Activation

- Metal-mediated reactions towards the synthesis of a novel deaminolysed bisurea, dicarbamolyamine

- The structure of ortho-(trifluoromethyl)phenol in comparison to its homologues – A combined experimental and theoretical study

- Heterogeneous catalysis with encapsulated haem and other synthetic porphyrins: Harnessing the power of porphyrins for oxidation reactions

- Recent Advances on Mechanistic Studies on C–H Activation Catalyzed by Base Metals

- Reactions of the organoplatinum complex [Pt(cod) (neoSi)Cl] (neoSi = trimethylsilylmethyl) with the non-coordinating anions SbF6– and BPh4–

- Erratum

- Investigation on Two Compounds of O, O’-dithiophosphate Derivatives as Corrosion Inhibitors for Q235 Steel in Hydrochloric Acid Solution

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The effect of CuO modification for a TiO2 nanotube confined CeO2 catalyst on the catalytic combustion of butane

- The preparation and antibacterial activity of cellulose/ZnO composite: a review

- Linde Type A and nano magnetite/NaA zeolites: cytotoxicity and doxorubicin loading efficiency

- Performance and thermal decomposition analysis of foaming agent NPL-10 for use in heavy oil recovery by steam injection

- Spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, UV, 1H and 13C NMR) insights, electronic profiling and DFT computations on ({(E)-[3-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-1-phenylpropylidene] amino}oxy)(4-nitrophenyl)methanone, an imidazole-bearing anti-Candida agent

- A Simplistic Preliminary Assessment of Ginstling-Brounstein Model for Solid Spherical Particles in the Context of a Diffusion-Controlled Synthesis

- M-Polynomials And Topological Indices Of Zigzag And Rhombic Benzenoid Systems

- Photochemical Transformation of some 3-benzyloxy-2-(benzo[b]thiophen-2-yl)-4Hchromen-4-ones: A Remote Substituent Effect

- Dynamic Changes of Secondary Metabolites and Antioxidant Activity of Ligustrum lucidum During Fruit Growth

- Studies on the flammability of polypropylene/ammonium polyphosphate and montmorillonite by using the cone calorimeter test

- DSC, FT-IR, NIR, NIR-PCA and NIR-ANOVA for determination of chemical stability of diuretic drugs: impact of excipients

- Antioxidant and Hepatoprotective Effects of Methanolic Extracts of Zilla spinosa and Hammada elegans Against Carbon Tetrachlorideinduced Hepatotoxicity in Rats

- Prunus cerasifera Ehrh. fabricated ZnO nano falcates and its photocatalytic and dose dependent in vitro bio-activity

- Organic biocides hosted in layered double hydroxides: enhancing antimicrobial activity

- Experimental study on the regulation of the cholinergic pathway in renal macrophages by microRNA-132 to alleviate inflammatory response

- Synthesis, characterization, in-vitro antimicrobial properties, molecular docking and DFT studies of 3-{(E)-[(4,6-dimethylpyrimidin-2-yl)imino]methyl} naphthalen-2-ol and Heteroleptic Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Zn(II) complexes

- M-Polynomials and Topological Indices of Dominating David Derived Networks

- Human Health Risk Assessment of Trace Metals in Surface Water Due to Leachate from the Municipal Dumpsite by Pollution Index: A Case Study from Ndawuse River, Abuja, Nigeria

- Analysis of Bowel Diseases from Blood Serum by Autofluorescence and Atomic Force Microscopy Techniques

- Hydrographic parameters and distribution of dissolved Cu, Ni, Zn and nutrients near Jeddah desalination plant

- Relationships between diatoms and environmental variables in industrial water biotopes of Trzuskawica S.A. (Poland)

- Optimum Conversion of Major Ginsenoside Rb1 to Minor Ginsenoside Rg3(S) by Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Acid Hydrolysis Treatment

- Antioxidant, Anti-microbial Properties and Chemical Composition of Cumin Essential Oils Extracted by Three Methods

- Regulatory mechanism of ulinastatin on autophagy of macrophages and renal tubular epithelial cells

- Investigation of the sustained-release mechanism of hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose skeleton type Acipimox tablets

- Bio-accumulation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Grey Mangrove (Avicennia marina) along Arabian Gulf, Saudi Coast

- Dynamic Change of Secondary Metabolites and spectrum-effect relationship of Malus halliana Koehne flowers during blooming

- Lipids constituents from Gardenia aqualla Stapf & Hutch

- Effect of using microwaves for catalysts preparation on the catalytic acetalization of glycerol with furfural to obtain fuel additives

- Effect of Humic Acid on the Degradation of Methylene Blue by Peroxymonosulfate

- Serum containing drugs of Gua Lou Xie Bai decoction (GLXB-D) can inhibit TGF-β1-Induced Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in A549 Cells

- Antiulcer Activity of Different Extracts of Anvillea garcinii and Isolation of Two New Secondary Metabolites

- Analysis of Metabolites in Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz Dry Red Wines from Shanxi by 1H NMR Spectroscopy Combined with Pattern Recognition Analysis

- Can water temperature impact litter decomposition under pollution of copper and zinc mixture

- Released from ZrO2/SiO2 coating resveratrol inhibits senescence and oxidative stress of human adipose-derived stem cells (ASC)

- Validated thin-layer chromatographic method for alternative and simultaneous determination of two anti-gout agents in their fixed dose combinations

- Fast removal of pollutants from vehicle emissions during cold-start stage

- Review Article

- Catalytic activities of heterogeneous catalysts obtained by copolymerization of metal-containing 2-(acetoacetoxy)ethyl methacrylate

- Antibiotic Residue in the Aquatic Environment: Status in Africa

- Regular Articles

- Mercury fractionation in gypsum using temperature desorption and mass spectrometric detection

- Phytosynthetic Ag doped ZnO nanoparticles: Semiconducting green remediators

- Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Induced by SMAD4 Activation in Invasive Growth Hormone-Secreting Adenomas

- Physicochemical properties of stabilized sewage sludge admixtures by modified steel slag

- In Vitro Cytotoxic and Antiproliferative Activity of Cydonia oblonga flower petals, leaf and fruit pellet ethanolic extracts. Docking simulation of the active flavonoids on anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2

- Synthesis and Characterization of Pd exchanged MMT Clay for Mizoroki-Heck Reaction

- A new selective, and sensitive method for the determination of lixivaptan, a vasopressin 2 (V2)-receptor antagonist, in mouse plasma and its application in a pharmacokinetic study

- Anti-EGFL7 antibodies inhibit rat prolactinoma MMQ cells proliferation and PRL secretion

- Density functional theory calculations, vibration spectral analysis and molecular docking of the antimicrobial agent 6-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-ylmethyl)-5-ethyl-2-{[2-(morpholin-4-yl)ethyl] sulfanyl}pyrimidin-4(3H)-one

- Effect of Nano Zeolite on the Transformation of Cadmium Speciation and Its Uptake by Tobacco in Cadmium-contaminated Soil

- Effects and Mechanisms of Jinniu Capsule on Methamphetamine-Induced Conditioned Place Preference in Rats

- Calculating the Degree-based Topological Indices of Dendrimers

- Efficient optimization and mineralization of UV absorbers: A comparative investigation with Fenton and UV/H2O2

- Metabolites of Tryptophane and Phenylalanine as Markers of Small Bowel Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

- Adsorption and determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water through the aggregation of graphene oxide

- The role of NR2C2 in the prolactinomas

- Chromium removal from industrial wastewater using Phyllostachys pubescens biomass loaded Cu-S nanospheres

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Preparation of Calcium Fluoride using Phosphogypsum by Orthogonal Experiment

- The mechanism of antibacterial activity of corylifolinin against three clinical bacteria from Psoralen corylifolia L

- 2-formyl-3,6-bis(hydroxymethyl)phenyl benzoate in Electrochemical Dry Cell

- Electro-photocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin using calcium titanate

- Effect of Malus halliana Koehne Polysaccharides on Functional Constipation

- Structural Properties and Nonlinear Optical Responses of Halogenated Compounds: A DFT Investigation on Molecular Modelling

- DMFDMA catalyzed synthesis of 2-((Dimethylamino)methylene)-3,4-dihydro-9-arylacridin-1(2H)-ones and their derivatives: in-vitro antifungal, antibacterial and antioxidant evaluations

- Production of Methanol as a Fuel Energy from CO2 Present in Polluted Seawater - A Photocatalytic Outlook

- Study of different extraction methods on finger print and fatty acid of raw beef fat using fourier transform infrared and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- Determination of trace fluoroquinolones in water solutions and in medicinal preparations by conventional and synchronous fluorescence spectrometry

- Extraction and determination of flavonoids in Carthamus tinctorius

- Therapeutic Application of Zinc and Vanadium Complexes against Diabetes Mellitus a Coronary Disease: A review

- Study of calcined eggshell as potential catalyst for biodiesel formation using used cooking oil

- Manganese oxalates - structure-based Insights

- Topological Indices of H-Naphtalenic Nanosheet

- Long-Term Dissolution of Glass Fibers in Water Described by Dissolving Cylinder Zero-Order Kinetic Model: Mass Loss and Radius Reduction

- Topological study of the para-line graphs of certain pentacene via topological indices

- A brief insight into the prediction of water vapor transmissibility in highly impermeable hybrid nanocomposites based on bromobutyl/epichlorohydrin rubber blends

- Comparative sulfite assay by voltammetry using Pt electrodes, photometry and titrimetry: Application to cider, vinegar and sugar analysis

- MicroRNA delivery mediated by PEGylated polyethylenimine for prostate cancer therapy

- Reversible Fluorescent Turn-on Sensors for Fe3+ based on a Receptor Composed of Tri-oxygen Atoms of Amide Groups in Water

- Sonocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in aqueous solution using Fe-doped TiO2 nanoparticles under mechanical agitation

- Hydrotalcite Anchored Ruthenium Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction

- Production and Analysis of Recycled Ammonium Perrhenate from CMSX-4 superalloys

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- New phosphorus biofertilizers from renewable raw materials in the aspect of cadmium and lead contents in soil and plants

- Survey of content of cadmium, calcium, chromium, copper, iron, lead, magnesium, manganese, mercury, sodium and zinc in chamomile and green tea leaves by electrothermal or flame atomizer atomic absorption spectrometry

- Biogas digestate – benefits and risks for soil fertility and crop quality – an evaluation of grain maize response

- A numerical analysis of heat transfer in a cross-current heat exchanger with controlled and newly designed air flows

- Freshwater green macroalgae as a biosorbent of Cr(III) ions

- The main influencing factors of soil mechanical characteristics of the gravity erosion environment in the dry-hot valley of Jinsha river

- Free amino acids in Viola tricolor in relation to different habitat conditions

- The influence of filler amount on selected properties of new experimental resin dental composite

- Effect of poultry wastewater irrigation on nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon contents in farmland soil

- Response of spring wheat to NPK and S fertilization. The content and uptake of macronutrients and the value of ionic ratios

- The Effect of Macroalgal Extracts and Near Infrared Radiation on Germination of Soybean Seedlings: Preliminary Research Results

- Content of Zn, Cd and Pb in purple moor-grass in soils heavily contaminated with heavy metals around a zinc and lead ore tailing landfill

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Synthesis of (±)-3,4-dimethoxybenzyl-4-methyloctanoate as a novel internal standard for capsinoid determination by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS(QTOF)

- Repellent activity of monoterpenoid esters with neurotransmitter amino acids against yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti

- Effect of Flammulina velutipes (golden needle mushroom, eno-kitake) polysaccharides on constipation

- Bioassay-directed fractionation of a blood coagulation factor Xa inhibitor, betulinic acid from Lycopus lucidus

- Antifungal and repellent activities of the essential oils from three aromatic herbs from western Himalaya

- Chemical composition and microbiological evaluation of essential oil from Hyssopus officinalis L. with white and pink flowers

- Bioassay-guided isolation and identification of Aedes aegypti larvicidal and biting deterrent compounds from Veratrum lobelianum

- α-Terpineol, a natural monoterpene: A review of its biological properties

- Utility of essential oils for development of host-based lures for Xyleborus glabratus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae), vector of laurel wilt

- Phenolic composition and antioxidant potential of different organs of Kazakh Crataegus almaatensis Pojark: A comparison with the European Crataegus oxyacantha L. flowers

- Isolation of eudesmane type sesquiterpene ketone from Prangos heyniae H.Duman & M.F.Watson essential oil and mosquitocidal activity of the essential oils

- Comparative analysis of the polyphenols profiles and the antioxidant and cytotoxicity properties of various blue honeysuckle varieties

- Special Issue on ICCESEN 2017

- Modelling world energy security data from multinomial distribution by generalized linear model under different cumulative link functions

- Pine Cone and Boron Compounds Effect as Reinforcement on Mechanical and Flammability Properties of Polyester Composites

- Artificial Neural Network Modelling for Prediction of SNR Effected by Probe Properties on Ultrasonic Inspection of Austenitic Stainless Steel Weldments

- Calculation and 3D analyses of ERR in the band crack front contained in a rectangular plate made of multilayered material

- Improvement of fuel properties of biodiesel with bioadditive ethyl levulinate

- Properties of AlSi9Cu3 metal matrix micro and nano composites produced via stir casting

- Investigation of Antibacterial Properties of Ag Doped TiO2 Nanofibers Prepared by Electrospinning Process

- Modeling of Total Phenolic contents in Various Tea samples by Experimental Design Methods

- Nickel doping effect on the structural and optical properties of indium sulfide thin films by SILAR

- The effect mechanism of Ginnalin A as a homeopathic agent on various cancer cell lines

- Excitation functions of proton induced reactions of some radioisotopes used in medicine

- Oxide ionic conductivity and microstructures of Pr and Sm co-doped CeO2-based systems

- Rapid Synthesis of Metallic Reinforced in Situ Intermetallic Composites in Ti-Al-Nb System via Resistive Sintering

- Oxidation Behavior of NiCr/YSZ Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs)

- Clustering Analysis of Normal Strength Concretes Produced with Different Aggregate Types

- Magnetic Nano-Sized Solid Acid Catalyst Bearing Sulfonic Acid Groups for Biodiesel Synthesis

- The biological activities of Arabis alpina L. subsp. brevifolia (DC.) Cullen against food pathogens

- Humidity properties of Schiff base polymers

- Free Vibration Analysis of Fiber Metal Laminated Straight Beam

- Comparative study of in vitro antioxidant, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase activity of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) collected during different growth stages

- Isothermal Oxidation Behavior of Gadolinium Zirconate (Gd2Zr2O7) Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs) produced by Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition (EB-PVD) technique

- Optimization of Adsorption Parameters for Ultra-Fine Calcite Using a Box-Behnken Experimental Design

- The Microstructural Investigation of Vermiculite-Infiltrated Electron Beam Physical Vapor Deposition Thermal Barrier Coatings

- Modelling Porosity Permeability of Ceramic Tiles using Fuzzy Taguchi Method

- Experimental and theoretical study of a novel naphthoquinone Schiff base

- Physicochemical properties of heat treated sille stone for ceramic industry

- Sand Dune Characterization for Preparing Metallurgical Grade Silicon

- Catalytic Applications of Large Pore Sulfonic Acid-Functionalized SBA-15 Mesoporous Silica for Esterification

- One-photon Absorption Characterizations, Dipole Polarizabilities and Second Hyperpolarizabilities of Chlorophyll a and Crocin

- The Optical and Crystallite Characterization of Bilayer TiO2 Films Coated on Different ITO layers

- Topical Issue on Bond Activation

- Metal-mediated reactions towards the synthesis of a novel deaminolysed bisurea, dicarbamolyamine

- The structure of ortho-(trifluoromethyl)phenol in comparison to its homologues – A combined experimental and theoretical study

- Heterogeneous catalysis with encapsulated haem and other synthetic porphyrins: Harnessing the power of porphyrins for oxidation reactions

- Recent Advances on Mechanistic Studies on C–H Activation Catalyzed by Base Metals

- Reactions of the organoplatinum complex [Pt(cod) (neoSi)Cl] (neoSi = trimethylsilylmethyl) with the non-coordinating anions SbF6– and BPh4–

- Erratum

- Investigation on Two Compounds of O, O’-dithiophosphate Derivatives as Corrosion Inhibitors for Q235 Steel in Hydrochloric Acid Solution