Abstract

Electromagnetic shielding (EMS) fabric is an effective way to prevent electromagnetic (EM) radiation. However, the research about mechanism analysis of the fabrics’ structure, EM wave (EMW) incident direction, and EMW frequency on the EMS properties of knitted fabrics is discordant at present. Meanwhile, researchers are focused on improving the EMS efficiency of the fabric but rarely discussed the thermal-wet comfort of the fabric. Therefore, in this study a series of weft-knitted fabrics within stainless steel/cotton (30/70) blended yarns were knitted, and the effects of EMW incident direction, stitches, loop lengths, and frequency on EMS effectiveness (EMSE) were analyzed. Meanwhile, the EMS property, warmth retention property, air permeability, moisture permeability, and bursting strength were selected as the evaluation index to evaluate the comprehensive properties of the fabrics by fuzzy mathematics. The results showed that all factors had different degrees of influence on EMSE, and the weft inlay stitch had both the functionality and thermal-wet comfort, which was excellent EMSE in knitted fabric. These results are expected to provide a reference to the design of EMS weft-knitted fabrics.

1 Introduction

With the development of the electronic information industry and the wide application of electronic equipment in people’s life, electromagnetic (EM) radiation has become the fourth largest pollution source after water, air, and noise pollution (1). Relevant research works showed that EM waves (EMWs) endanger health (2,3,4,5). Therefore, the researchers focused on improving fabrics’ EM shielding effectiveness (EMSE) to protect the human body effectively.

EM shielding (EMS) fabrics commonly included plated EMS fabrics, coated EMS fabrics, and conductive fiber EMS fabrics (6). Plated EMS fabrics are plated with Cu, Ag, Al, Ni, and other metals on the fabric’s surface to form a metal conductive layer, which can reflect the EMW. Plated EMS fabrics have specific production and application scope limitations according to different plated metals (7,8,9). Coated EMS fabrics are the fabric in which a certain amount of EM loss material metal (such as carbon) was added to the finishing agent and then coated on the surface of the fabric. Due to the limitation of coating technology, coated EMS fabrics have poor hand feel and breathability, and the EMSE decreases with the increase in washing times (10,11,12). Conductive fiber EMS fabric is woven or knitted by a conductive filament or fiber blended yarn. Conductive fibers mainly include stainless steel (SS), copper, carbon fiber, and nickel fiber. The SS fiber has good conductivity and heat transfer ability, high-temperature resistance, reflection wave, and good spinning-ability and processing properties (13,14,15,16), so it is widely used.

Many scholars (17,18,19) investigated SS content and found that the higher the SS concentration in the yarn, the better the EMSE of the fabric obtained. However, when the content of SS fiber in the yarn increases to a certain extent, the bending stiffness and bending modulus of the yarn increase, the gap between the fibers in the yarn increases, and the change in EMSE tend to be gentle or even decline. Therefore, considering its properties, the content of SS metal fiber is generally 20–30% (20).

Many studies (21,22,23,24,25,26) discovered that fabric structure has a significant impact on EMS properties. However, the analyses of mechanism were inconsistent. Abdulla et al. (24) knitted copper/cotton core-spun yarns into full Milano and 1 × 1 rib stitches and examined EMSE at a frequency range of 0.03–1.5 GHz. The results showed that the full Milano stitch had larger EMSE values than the 1 × 1 rib stitch. Wang et al. (25) knitted SS/cotton fiber blended yarn into 1 × 1 rib stitch, 2 × 2 rib stitch, Cardigan stitch, Milano rib, and half Milano rib stitch and examined the EMSE of the five stitches. The results showed that the EMSE of Cardigan fabric was the best, which may be due to the compact structure. Su et al. (26) pointed out that float was an essential factor affecting the EMSE conductivity of cloth. This conclusion may help us to explain the mechanism of the fabric structure. But they are not further explained in this work.

Some researchers (27,28,29,30) investigated the influence of EMW incidence direction and discovered that it had a significant impact on fabric EMSE. However, opinions on flouncing rules and interpretation were inconsistent. Zhang et al. (28) simulated the process of EMW incidence direction on the woven fabric from 0° to 90° by adjusting the angle between the fabric’s SS filament and the electric field’s polarization plane. The result showed that when the angle is 90°, the EMSE of the fabric is the best. When the angle is 0°, there is almost no EMSE. They believed that the result related to the directional selectivity of the metal gate to the EMW. Ortlek et al. (30) tested the EMSE of the plain knitted fabric in each polarization direction, and found that there was no EMS in the vertical polarization direction but found more than 30 dB in the horizontal polarization direction. They suspected it had something to do with the fiber orientation in the yarn.

As for the influence of the loop length on EMS properties, Ortlek et al. (30) emphasized that EMSE increased with the decrease in loop length, mainly because the content of SS wire per unit area of sample increased with the decline in loop length.

Many scholars (31,32,33) investigated the effect of EMW frequency on EMS characteristics and discovered that the EMSE value decreases as EMW frequency increases, but the theories for the shielding mechanism differed. Zhang et al. (28) and Ortlek et al. (33) concurred that with the increase in EM frequency, the wavelength of EMW decreases and the penetration rate of EMW increases, so the EMSE decreases. However, Liu et al. (29,31) believed that the increase in EM frequency changes the conductivity and permeability of the fabric, which ultimately leads to the decline in the EMSE of the fabric.

When the influencing rules and mechanisms of various factors on EMSE were being researched, some scholars (34,35,36) noted the thermal-wet comfort of EMS fabrics. Therefore, some researchers (37,38,39) suggested taking thermal-wet comfort as one of the main indexes of the comprehensive evaluation. Song et al. (40) analyzed the comprehensive property, including the EMS property and wearing comfort of radiation protection fabrics by gray clustering analysis. But it is so hard to directly evaluate which fabrics’ comprehensive is good. It is because that the comprehensive evaluation of fabrics is a fuzzy process of psychological and physiological interaction, and some unclear and unquantifiable factors are involved in the evaluation (41). Fortunately, fuzzy mathematics provides a good way to deal with uncertainty and imprecision problems (42). In the process, the index is quantified and given weights according to the design requirements, which makes the result accurate and intuitive. Therefore, in the textile industry, fuzzy mathematics is widely used for the selection and mixing of raw materials, quality judgment of raw strips, and warp tension control in weaving (43,44), but less used for the comprehensive performance evaluation of fabrics.

In this work, 15 kinds of weft-knitted fabrics were knitted with SS/cotton (30/70) blended yarn in a flat knitting machine. The influences of structure, incidence EMW direction, loop length, and EM frequency on the EMSE of weft-knitted fabric were analyzed and summarized. Considering the functionality and thermal-wet comfort of the materials, the EMS properties, warmth retention property, air permeability, moisture permeability, and bursting strength were selected as the evaluation index to evaluate the comprehensive properties of fabric by fuzzy mathematics. The results provide a reference for the establishment of knitted EMS fabric design and enterprise production.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

The cotton/SS blended yarn was supplied by Xinxiang North Fiber Co. Ltd (China). The blending ratio of the yarn was SS fiber at 30% and cotton fiber at 70%. The yarn density was 2 × 21 s. At the same time, a cotton fabric with the yarn density of 2 × 21 s was selected as a control experiment, and the EMSE value of the cotton fabric was near 0 [25]), so the amount of cotton in the blended yarn had no effect on EMSE.

The fabrics were knitted by computerized flat knitting machine E7.2 (ADF530-16W. STOLL, Germany). The pattern programming system was M1plus. The work knitted five structures, each containing three densities. The sketches and notations of structures are shown in Figure 1, and the specifications of the fabrics are shown in Table 1. In the table, the weft inlay stitch is a one-bed structure placed floating along the whole fabric width. The frequency of the inlay is one by one. The inserted weft yarn is also SS/cotton blended yarn.

The sketches and notations of five structures. (a) Plain (single jersey), (b) Cardigan stitch, (c) half Cardigan stitch, (d) Milano rib, and (e) Weft inlay stitch.

Fabric specifications

| Fabric stitch | Fabric code | Loop length (mm) | Course density (loop/5 cm) | Wale density (loop/5 cm) | Thickness (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plain (single jersey) | 1# | 9.5 | 39.2 ± 0.9 | 96.3 ± 0.5 | 1.54 ± 0.03 |

| 2# | 9.8 | 42.3 ± 0.5 | 84.2 ± 0.5 | 1.66 ± 0.02 | |

| 3# | 10.0 | 42.2 ± 0.9 | 75.4 ± 0.5 | 1.54 ± 0.03 | |

| Cardigan stitch | 4# | 8.3 | 18.2 ± 0.9 | 52.0 ± 0.3 | 2.60 ± 0.02 |

| 5# | 8.5 | 18.3 ± 0.8 | 52.3 ± 0.5 | 2.59 ± 0.02 | |

| 6# | 8.9 | 19.0 ± 0.5 | 54.0 ± 0.3 | 2.58 ± 0.04 | |

| Half Cardigan | 7# | 9.2 | 21.0 ± 0.9 | 37.4 ± 0.8 | 2.47 ± 0.03 |

| 8# | 9.5 | 21.0 ± 0.8 | 39.4 ± 0.8 | 2.53 ± 0.02 | |

| 9# | 9.8 | 22.5 ± 0.5 | 41.3 ± 0.8 | 2.68 ± 0.03 | |

| Milano rib | 10# | 9.5 | 19.0 ± 1.0 | 51.4 ± 0.6 | 3.28 ± 0.02 |

| 11# | 9.8 | 20.0 ± 0.8 | 55.3 ± 0.5 | 3.77 ± 0.04 | |

| 12# | 10.0 | 21.0 ± 0.5 | 56.4 ± 0.6 | 3.89 ± 0.05 | |

| Weft inlay stitch | 13# | 11.0 | 22.0 ± 0.5 | 41.5 ± 0.9 | 1.87 ± 0.02 |

| 14# | 11.2 | 22.5 ± 0.5 | 42.5 ± 0.9 | 1.83 ± 0.02 | |

| 15# | 11.3 | 23.0 ± 0.9 | 43.5 ± 0.9 | 1.92 ± 0.02 |

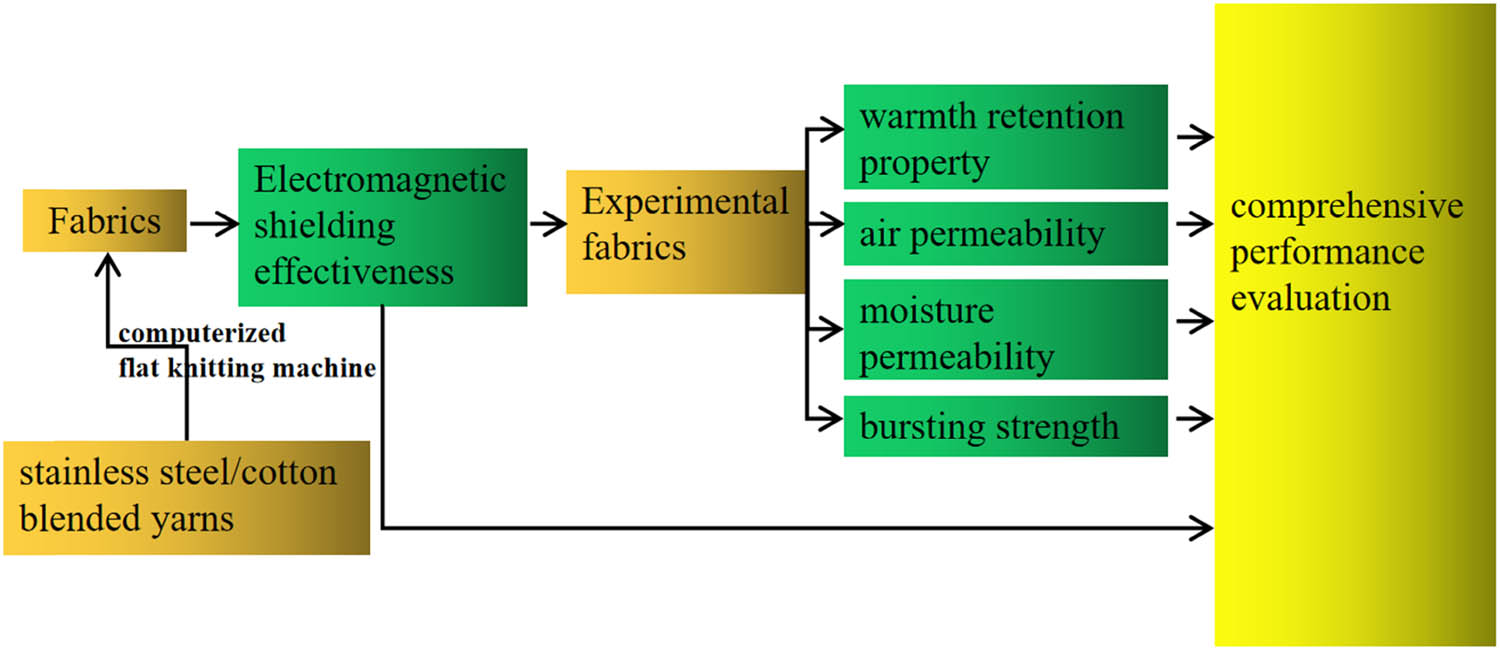

The process of the study is shown in Figure 2.

The process of the study.

2.2 Measurement of EMSE

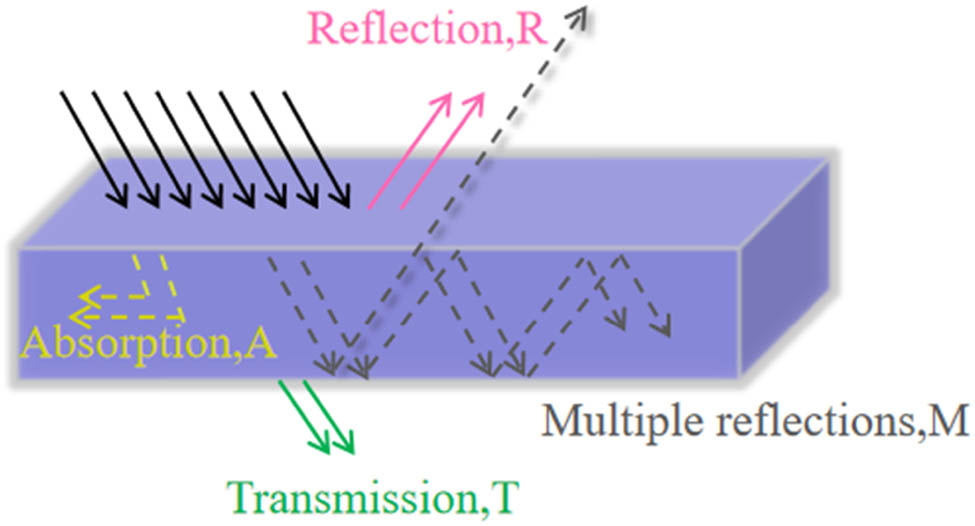

EMS technology uses shielding materials to reflect or attenuate EM waves so they cannot enter the shielded area. The loss modes of shielding materials are usually divided into absorption loss (A), reflection loss (R), and multiple reflection loss (M). The principle of EMS is shown in Figure 3.

The principle of EMS.

The EMS performance of the shielding material on a certain point in space is expressed by the EMSE. The EMSE refers to the magnetic field intensity, electric field intensity, or power ratio before and after the shielding material is placed, and is expressed as follows:

where SE is the shielding effectiveness (dB);

The EMSE was tested by PN∼L Network Analyses (N5232A, Agilent Technologies, US). The experimental frequency range is 6.57–9.99 GHz, and the sample was a rectangle of 4.0 cm × 3.5 cm, each piece was tested five times, and the average value was taken as the result. Figure 4a and b shows the experimental principle and equipment.

Test principle and test instrument (a) Test principle: a: network analyzer. A: output port, B: reflection input port, and C: transmission input port; b: waveguide tube with a signal transmitter; c: signal attenuator; d: waveguide tube with detecting reflection sensor; e: waveguide tube for placing sample; and f: sensors and waveguides for detecting transmitted signals. (b) Test instrument. (c) The directions of the electric and magnetic fields in the rectangular waveguide. (d) The direction of the fabric's position in the rectangular waveguide.

In the rectangular waveguide, the EMW were polarized into two mutually perpendicular planes of electric and magnetic fields. The vibration plane of the electric field is in the horizontal direction, and the vibration plane of the magnetic field is in the vertical direction (38), as shown in Figure 3c. In the circular waveguide, the electric and magnetic fields are located in the circumference and the meridian direction, respectively. The measurement difference between the circular and rectangular waveguides cannot be significant for isotropic materials. But for the SS fiber knitting fabrics, the loop continues only in the transverse or longitudinal direction. It is not strictly isotropic material. Therefore, the direction of the fabric’s placement in a rectangular waveguide will affect the test results (39). To study the effects of directions of the fabric on EMSE, the direction parallel to the long side of the fabric was named course direction, the vertical direction was named wale direction, and the included angle was 45°. The position of the fabrics in the rectangular waveguide is shown in Figure 3d.

The grading of textiles with EMSE ability for general use (class II) according to FTTS-FA-003:2005 is presented in Table 2.

Grading of EMS fabrics for general use

| Grade | 5 Excellent | 4 Very good | 3 Good | 2 Moderate | 1 Fair |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE (dB) | >30 | 20–30 | 10–20 | 7–10 | 5–7 |

2.3 Measurement of warmth retention property

Warmth retention property refers to the performance of the fabric that can prevent the heat generated by the body from being transferred to the outside with a lower temperature, or prevent the effect of high temperature on the body, also known as heat retention or heat insulation property. Warmth retention properties of fabrics are characterized by Thermal retention ratio, thermal conductivity, and thermal resistance.

Thermal retention ratio: It refers to the ratio of the difference between the heat dissipation without samples and the heat dissipation with samples to the heat dissipation without sample.

Thermal conductivity: It refers to the heat flow through the unit area when the temperature difference of the textile surface is 1K, the unit is W·(m2·K)−1.

Thermal resistance: It is defined as the heat flux through the sample after reaching steady-state conditions, the unit is m2·K·W−1 (45).

The test method is flat plate test method. The test instrument is flat-plate insulation instrument (YG606D, Wenzhou, China). A flat-plate fabric thermometer was used to test the warmth retention property (YG606D, Wenzhou, China). The sample is a square of 30 cm × 30 cm. Each sample was tested five times, and the results were averaged.

2.4 Measurement of air permeability

Air permeability refers to vertical airflow through the sample within a unit of time (1 s) under a specified test area and pressure. Air permeability (mm·s−1) is an important index to characterize the air permeability of the fabric.

The air permeability of fabric can be obtained by measuring the difference pressure between the two sides of flow aperture. The air permeability was tested by digital permeability tester (TYG461, Wuhan, China). The test area of the sample was 20 cm2, and every sample was tested ten times in different parts. The work set the differential pressure of the sample to 100 Pa. The air permeability of the fabric selects the air injection flow aperture. The fabric has better air permeability with a larger aperture, while the fabric with poor air permeability has a smaller gap.

2.5 Measurement of moisture permeability

Water-vapor transmission (WVT) can be used to assess a fabric's moisture permeability. It refers to the amount of water that moves from one side of the specimen to the other side in a given amount of time and area under particular temperature and humidity conditions. WVT can be measured in g·(m2‧h)−1 or g·(m2‧24 h)−1. The calculation of WVT is shown in formula 2.

where

The moisture permeability test was carried out using a fabric moisture permeability meter (YG (B) 216X, Wenzhou, China) under standard GB/T 12704.1-2009 (China). The experimental temperature was 38°C, relative humidity was 90%, and airflow speed was 0.3–0.5 m·s−1. The sample was circle with a diameter of 70 mm. Each sample was tested five times, and the results were averaged.

2.6 Measurement of bursting strength

Knitted fabrics are constantly pressured by the elbow, knee, and other body parts, so the fastness of knitted fabrics commonly uses bursting strength as an evaluation index.

The sample was clamped in a circular clamp with a fixed base, and the spherical bar was pushed vertically against the sample with a constant speed to deform the sample until it broke. The maximum force in the process of destruction was called bursting strength.

The experimental apparatus adopted a constant rate of extension testing machine (CRE-YG0268) and electronic fabric strength machine, and the experimental procedure was operated according to GB19976-2005GB/T (China). In the testing process, the gripper holding the sample was fixed, and the spherical bar moved at a constant speed of 100 mm·s−1 vertically against the sample and deformed it until it broke. The samples were prepared as 6 cm diameter circles, avoiding folds and unrepresentative fabric edges. Five samples were prepared for each stitch, and the results were averaged.

2.7 Fuzzy comprehensive evaluation

A comprehensive evaluation is the process of the general evaluation of things or phenomena affected by multiple factors. The fuzzy comprehensive evaluation mainly refers to using the relevant properties of fuzzy transformation between fuzzy mathematics and fuzzy identification for comprehensive evaluation (46). The mathematical model of fuzzy comprehensive evaluation includes four main parts (47), and the specific steps are as follows.

2.7.1 Determining the factor set U and evaluation set V

Let U = {U 1, U 2, …, U m } be the set of factors where U i (i = 1, 2, …, i) represents the ith factor affecting the evaluation result. Let V = {V 1, V 2, …, V P } be the set of evaluations, p is the number of specimens, and V j (j = 1, 2, …, p) represents the jth level of evaluation.

2.7.2 Establishing the multifactor fuzzy evaluation matrix R

Establish the single factor fuzzy evaluation R i = (r i1, r i2, …, r ip ), ith factor is a fuzzy subset on the evaluation set V, and r ip denotes the degree of membership of the evaluation of the ith factor to the jth level. So, the multifactor fuzzy evaluation matrix R is

2.7.3 Determining the weight set A

Let the assignment set A of weights to each evaluation index be A fuzzy set on the evaluation index set U, then A = (a 1, a 2, …, a m ), where a i represents the corresponding weight of the ith element, then 0 ≤ a i ≤ 1, and ∑a i = 1.

2.7.4 Calculation of the comprehensive evaluation matrix B and analyses of the result

The comprehensive evaluation matrix is B = A * R (,* is the fuzzy operator, and R is the fuzzy relationship from the factor set U to the evaluation set V. Now, we transform the problem of thorough fabric performance review into seeking the comprehensive evaluation with known weight set A and multifactor fuzzy evaluation matrix R.

Here we need to choose the appropriate synthetic arithmetic to calculate the comprehensive evaluation matrix B, and analyze the results.

3 Results and discussion

The EMSs were all tested in the frequency range of 6.57–9.99 GHz. Due to the performance analysis was based on EM needs, the factors affecting EMSE were mainly analyzed. The factors affecting the warmth retention property, air permeability, moisture permeability, and bursting strength are briefly summarized.

3.1 EMSE

3.1.1 Effect of testing directions on EMS performance

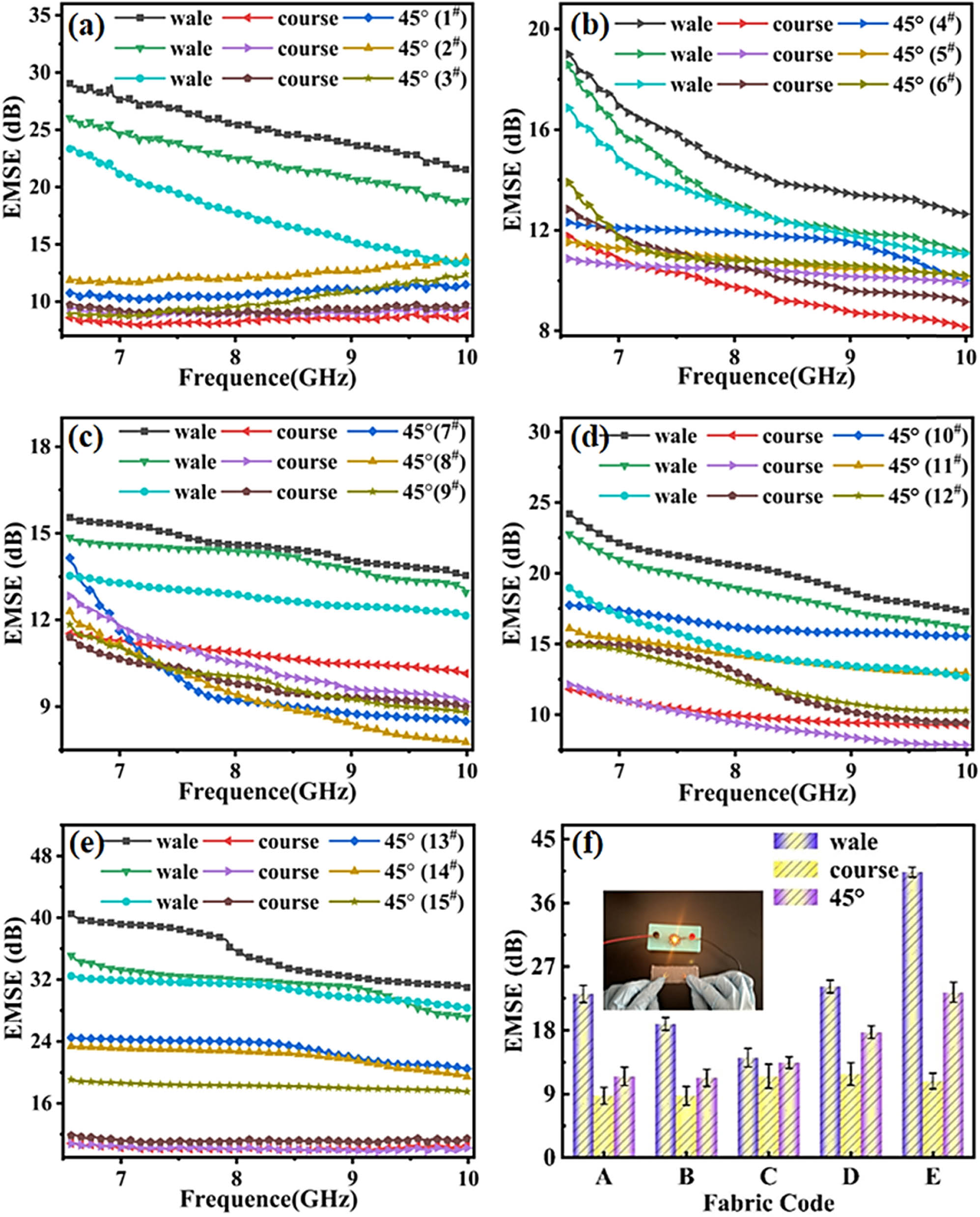

The EMSE value of the 1–15# fabrics tested in the frequency range of 6.57–9.99 GHz are shown in Figure 5.

EMSE of five structures tested in the wale, course, and 45° directions: (a) plain, (b) Cardigan stitch, (c) half Cardigan stitch, (d) Milano rib, (e) weft inlay stitch, and (f) EMSE of fabrics: A (2#), B (4#), C (7#), D (11#), and E (13#).

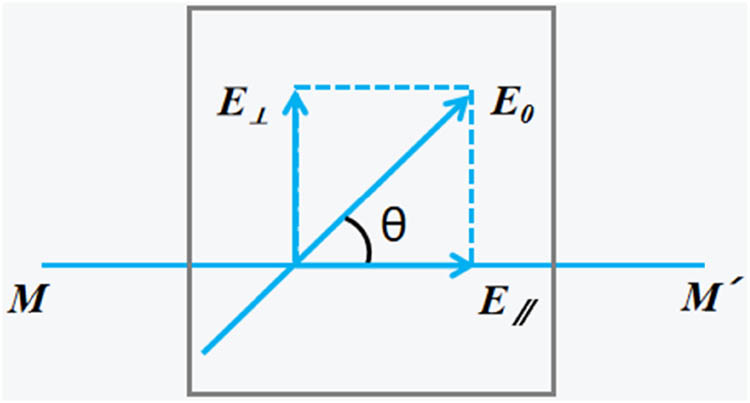

The EMSE value of 1–15# fabrics show that in wale direction, the value is the largest; in 45° direction, the value is in the middle; and in course direction, the value is the smallest. Take the weft inlay stitch for example, when the loop length is 11.0 (13#), the EMSE in wale direction is about 40 dB, it is about 22 dB in 45° direction, and about 12 dB in course direction. Malus’ law can explain the influence of fabric placement in waveguide on EMS performance: The metal grid formed by the metallic yarn has selective for the EMW. When the polarized EMW E 0 is incident on the horizontal metallic yarn, the parallel component E ∥ can be through, and the perpendicular component E ⟂ is reflected as shown in Figure 6 [48].

Selectivity of metal grid to the EMW.

In Figure 6, E

0 is the polarization direction of the electric field, E

∥

is the parallel component, E

⟂

is the perpendicular component, M–M′ is the metal grid. It can be seen from Figure 6 that the incident EMW forms an angle

where

3.1.2 Effect of stitches on EMS performance

The EMSE of weft inlay stitch was most prominent in the five stitches, followed by plain, Milano rib, Cardigan stitch, and half Cardigan stitch. Figure 5a shows that the EMSE of the plain was 12.5–29 dB in the wale direction, 8–10 dB in the course direction, and 9–12.5 dB in the 45° direction; Figure 5b shows that the EMSE of the Cardigan stitch was 10–19 dB in the wale direction, 10–15 dB in the course direction, and 10–15 dB in 45° direction. Due to the anisotropy of the fabric, it was not reasonable to use the value of a specific direction to indicate the EMS performance of the material. This study analyzed the EMSE of five stitches in the wale direction first and averaged the EMSE in two polarization directions as the total values. The EMSE of the five stitches is shown in Figure 7.

(a) The EMSE in wale direction of five stitches and (b) average value of EMSE in wale and course directions of the five stitches.

The EMSE value in the wale direction and the average EMSE value of the five stitches tend to be the same. The curve of EMSE value of weft inlay stitch is the largest, followed by plain, Milano rib, Cardigan stitch, and half Cardigan stitch. The analysis is mainly due to the differences arising from the different structures. As shown in Figure 1, the SS metal yarns in plain, Milano rib, Cardigan stitch, and half Cardigan stitch form transverse-conduction in course direction and play the role of EMS. But in the SS metal yarn in the weft inlay stitch, in addition to forming conduction in the course direction, the inserted yarn creates another conduction, significantly improving the fabric’s EMS performance.

3.1.3 Effect of loop lengths on EMS performance

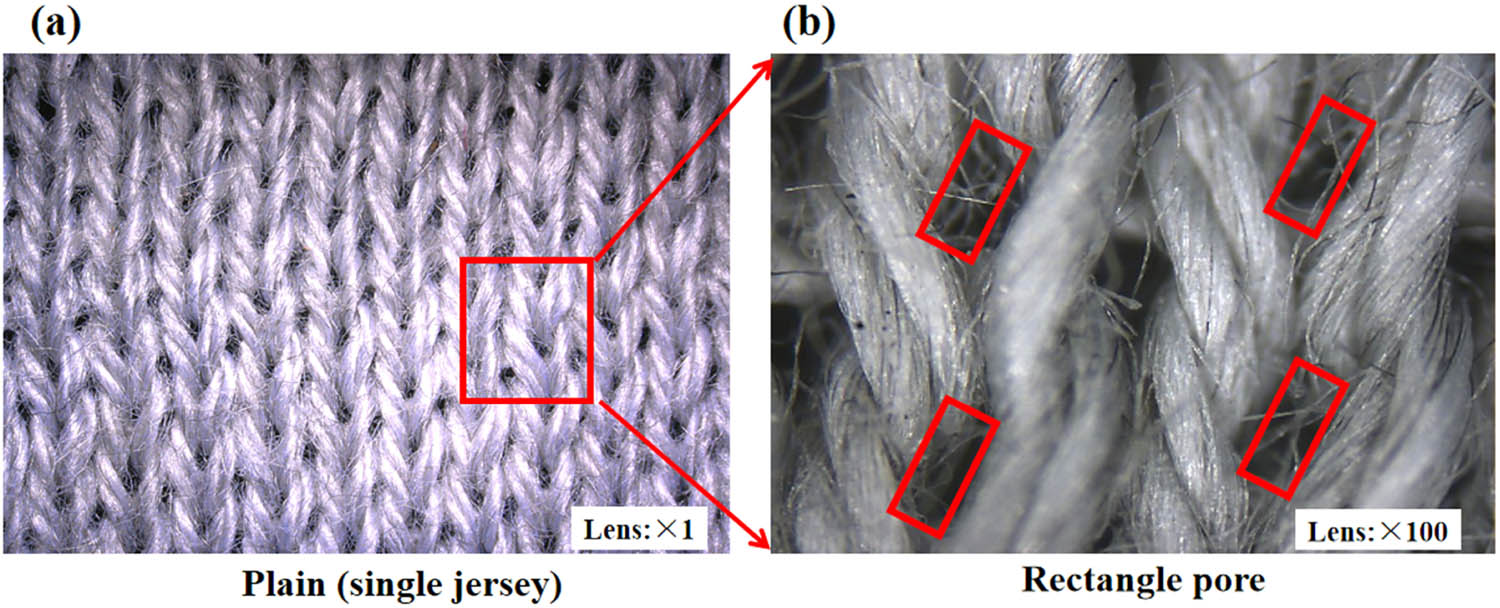

In Figure 8a, the EMSE of plain with 9.5 mm loop lengths was 8–10 dB higher than 9.8 mm loop lengths. The reason is mainly related to the structures of the knitted fabric, and the surface structure of plain is shown in Figure 8.

(a) The surface structure of the plain (single jersey) and (b) the rectangle pore.

The surface of the knitted fabric forms regularly distributed pores. When the knitted fabric was compact due to elasticity, these pores were approximated by a rectangle; the loop pillar forms the long side of the rectangle, and the top arc mainly creates the thickness of the fabric, that is, the depth of the pores (single-layer fabric). For the plain knitted fabrics, the thickness is about 2r (r is the yarn radius), and the length of the top arc is approximately equal to

where

The long side of the rectangle W can be represented as follows:

Schulz et al. (50) and Perumalraj et al. (51) suggested that the practical calculation formula that can be used to calculate the SE of perforated metal plate is as follows:

where A a is the absorption loss of the hole (dB), R a is the flection loss of the hole (dB), B a is the multiple flection correction factor (dB), K 1 is the correction term of the number of holes per unit area (dB), K 2 is the correction coefficient of low-frequency penetration (dB) (ignored at high frequencies), and K 3 is the correction of coupling between adjacent meshes (dB).

The following formulas calculate A a and R a of fabric (52,53):

where

It can be seen from formulas 9 and 10 that in the case of a specific yarn linear density, the increase in the loop length of the plain reduced the absorption loss and reflection loss and eventually led to a decrease in the EMSE value.

3.1.4 Effect of frequency on EMS performance

While analyzing the test data, we found that five stitches in the frequency range 6.57–9.99 GHz showed the same trend, i.e., the EMSE value decreased as the test frequency increased, as shown in Figure 6. This result can be explained by the calculation process of EMS for the ideal shielding material, as shown in formula 11.

where SE is the value of EMSE, A is the absorption loss, R is the reflection, and M is the multiple attenuation. The calculation procedures for R and A are shown in formulas 12 and 13, respectively; when A > 10 dB, the

where f is the incident wave frequency (MHz),

It can be concluded from formulas 13 and 14 that, with certain conditions, the reflection loss of fabric is mainly affected by EM frequency. With the increase in EM frequency, the reflection of fabric decreases and the absorption increases. However, the reduction in reflection is more significant than the increase in absorption, so the EMSE decreases overall.

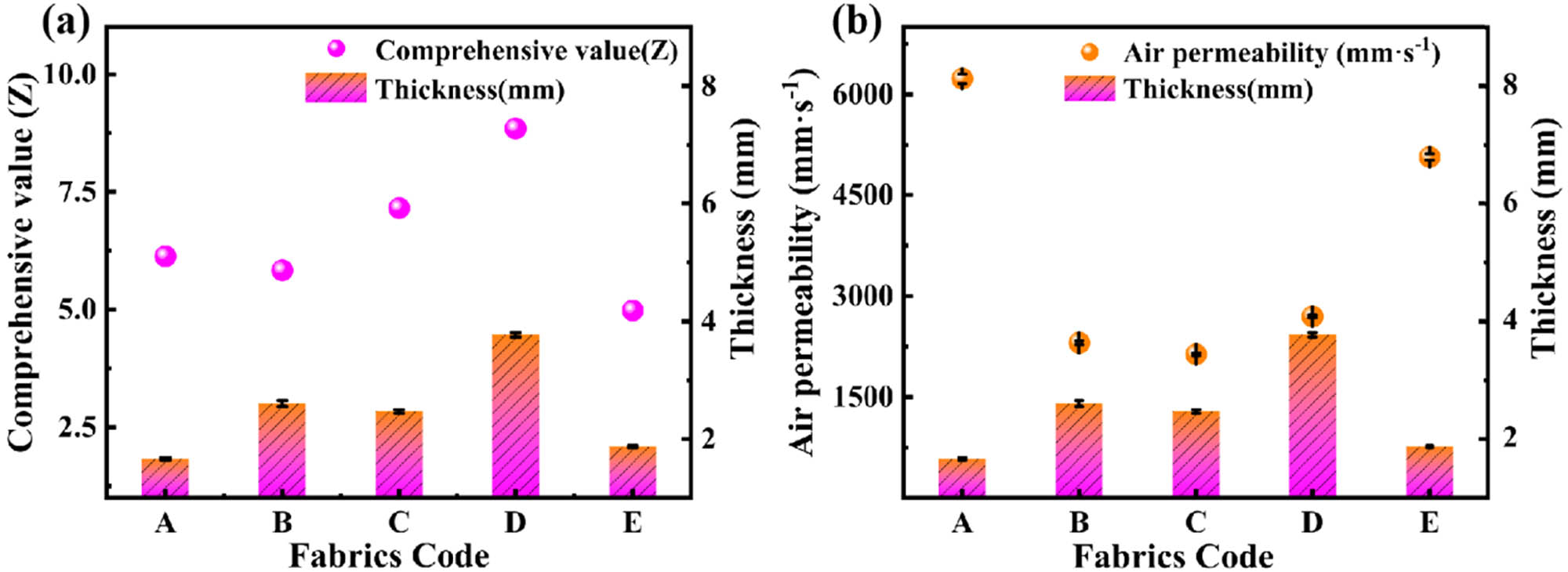

After testing the EMSE, the following five stitches are selected as alternative materials. A: plain with a loop length of 9.8 (2#). B: Cardigan stitch with a loop length of 8.3 (4#). C: half Cardigan stitch with a loop length of 9.2 (7#). D: Milano rib with a loop length of 9.8 (11#). E: weft inlay stitch with a loop length of 11.0 (13#).

3.2 Warmth retention property result and discussion

The test and calculation results of fabric warmth retention property is shown in Table 3.

Test and calculation results of fabric warmth retention property

| Indicators/fabric code | A | B | C | D | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal insulation ratio (%) | 21.9 ± 0.9 | 20.1 ± 0.9 | 23.3 ± 0.3 | 25.4 ± 0.9 | 18.8 ± 0.3 |

| Thermal conductivity W·(m2·K)−1 | 29.5 ± 1.0 | 29.8 ± 0.7 | 27.0 ± 0.6 | 24.1 ± 0.7 | 32.3 ± 0.9 |

| Thermal resistance m2·K·W−1 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.20 |

According to the experimental results, the Milano rib has the best warmth retention property among the five stitches. The warmth retention property is affected not only by the properties of fiber but also by the thickness of fabric and knitting technology, especially the thickness. The effect of fabrics thickness on warmth retention of fabric is shown in Figure 9.

(a) The effect of thickness on warmth retention of fabric and (b) the effect of thickness on air permeability.

It can be seen that the thickness of the fabric has a good consistency with the warmth retention property. The thicker the material is, the more still air content inside the fabric. The smaller the heat transfer coefficient of the fabric, the more significant the thermal resistance and insulation rate, and the better the thermal insulation performance of the material.

3.3 Air permeability result and discussion

The air permeability test results of the fabric are shown in Table 4.

Air permeability test results of the fabric

| Fabric code | A | B | C | D | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air permeability (mm·s−1) | 6,233.5 ± 50.2 | 2,307.0 ± 20.1 | 2,136.2 ± 23.2 | 2,696.2 ± 19.7 | 5,070.6 ± 47.3 |

In Table 4, the air permeability of the plain is the best, followed by weft inlay stitch, Milano rib, Cardigan stitch, and half Cardigan stitch.

The air permeability of fabric is mainly affected by raw materials, fabric structure, porosity, and other factors. In the design process of EMS-knitted fabrics, different fabric structures especially lead to different fabric thicknesses, and the influence of fabric thickness on air permeability is shown in Figure 9b. The fabric’s air permeability is negatively correlated with the thickness of the material.

3.4 Moisture permeability result and discussion

The moisture permeability test results of the fabric are shown in Table 5.

Moisture permeability testing results

| Fabric code | A | B | C | D | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δm (g) | 0.64 ± 0.03 | 0.57 ± 0.07 | 0.60 ± 0.1 | 0.61 ± 0.05 | 0.62 ± 0.03 |

| Moisture permeability (g·m−2·h−1) | 166.23 | 148.05 | 155.84 | 155.84 | 161.04 |

The more significant the fabric moisture permeability value, the easier it is to export the sweat produced by the surface layer of human skin so that the body remains dry and comfortable. The moisture permeability of SS EMS knitted fabric is between 140 and 177 g·m−2·h−1, which is medium level in the moisture permeability of knitted-fabric, among which the plain is the best, and the half Cardigan stitch is poor.

3.5 Bursting strength result

The bursting strength test results of the fabric are shown in Table 6.

Bursting strength test results

| Fabric Code | A | B | C | D | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bursting strength (N) | 545.4 ± 15.2 | 656.7 ± 10.3 | 567.2 ± 10.7 | 732.3 ± 16.1 | 556.5 ± 12.7 |

It was found that the bursting strength of the five stitches was higher than the bursting strength (473.4 N) of cotton fabric with the exact specifications. Milano rib has the most considerable bursting strength, followed by Cardigan stitch, half Cardigan stitch, weft inlay stitch, and plain. It is because blending the metal fiber in the yarn significantly improved the bursting strength of the fabric.

3.6 Fuzzy comprehensive performance evaluation

Fuzzy mathematics was used to evaluate the comprehensive performance of knitted fabrics. According to EMS-knitted fabric characteristics, EMS performance, warmth retention property, air permeability, moisture permeability, and bursting strength were selected as the fuzzy evaluation factors.

3.6.1 Determination of factor set U and evaluation set V

The EMS performance, warmth retention property, permeability, moisture permeability, and bursting strength of the fabric are set as the factor set U, U = {U1, U2, …, U5}, U = {EMS performance, warmth retention property, permeability, moisture permeability, bursting strength}; The evaluation set is sated as V, V = {V1, V2, …, V5}. V1–V5 represents the number of samples.

3.6.2 Calculation and establishment of the multifactor fuzzy evaluation matrix R

If the factors are exact values in the comprehensive evaluation process, factor fuzzification using fuzzy mathematics is required (53,54). The test results show that the higher the value, the better the performance, so we chose the function as shown in Eq. 14.

where

Substituting the test results in Eq. 14 yielded the multifactor fuzzy evaluation matrix R as follows:

3.6.3 Determination of the weight set A

The assignment and valuation of weight set A is a complex process. The value of the weight reflects the importance of the impact on the garment’s performance; the more significant the value, the greater the effect on the fabric’s performance, and when the value is less significant, the impact is smaller.

In the study, the primary demand for fabric is EMS, so the EMS performance weight value was 0.5. The addition of metal fibers in the yarns affected the fabric’s air permeability and moisture permeability, which are the characteristics of thermal-wet comfort, so the weight values were 0.15 (55,56), respectively. The demand for the warmth retention property of fabrics mainly depends on the use of materials. For knitted fabrics for daily wear, our requirements for warmth retention property are not high, so the weight of warmth retention property value is 0.1 (57,58). The fastness of fabric is one of the necessary conditions for material, and the value is 0.1 (58). The allocation of each weight is as follows:

3.6.4 Calculation of the comprehensive evaluation matrix B

The comprehensive evaluation matrix B is calculated using formula (15).

where

Substituting R and A in Eq. 16 yields:

Normalization of the results yield

3.6.5 Analysis of evaluation results

According to the principle of maximum affiliation, the larger the normalized value is, the closer the fabric’s performance is to the experimental expectation. The data analysis shows that the version of the weft inlay stitch is best, the plain is better, and the half Cardigan stitch is poor.

4 Conclusion

In the study, we knitted 15 kinds of weft-knitted fabrics, and analyzed the influences of structure, incidence EMW direction, loop length, and EM frequency on the EMSE of weft-knitted fabric. The results show that Plain, Milano rid, Cardigan stitch, and half Cardigan stitch consist of a system of SS metal yarns knitted from the course, conducting in a course direction. In weft inlay stitch, in addition to the course direction, the SS metal fibers in the insert weft yarn also form another course conduction, which significantly improves the fabric’s EMS performance. Therefore, we should focus on forming the conduction path to improve the fabric’s EMS performance in the fabric design.

The direction of the knitted fabric posited in the rectangular waveguide affects the EMSE, which in wale direction is the largest, in 45° direction is in the middle, and in course direction is the smallest. And the transmitted EM power is approximately equal to the incident EM power times

The loop forms rectangular pores on the surface of the knitted fabric. When the linear density of the yarn is constant, the absorption loss and reflection loss of the plain can be expressed by loop length and frequency. With the increased loop length, the fabric’s absorption and reflection loss become smaller, and the EMSE decreases.

In the frequency range of 6.57–9.99 GHz, the reflection loss decreases, and the absorption loss increases with the increase in the incident frequency. However, the reduction in reflection is more significant than the increase in absorption, so the EMS efficiency decreases overall.

In the end, we evaluated the comprehensive properties of the fabric by fuzzy mathematics. The results show that the weft inlay stitch had both the functionality and thermal-wet comfort, making it an excellent EMS knitted fabric. Meanwhile, fuzzy mathematics makes the comprehensive performance evaluation of fabrics more objective to match the requirements of SS EMS-knitted fabric’s design.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Ning LI: writing-original draft, methodology, and formal analysis; Tianjiao LIU: formal analysis and methodology; Mengqi TIAN: editing and validation; Junrui DUAN: writing – review and editing, project administration, and resources; Mu YAO: writing – review and editing and supervision; Runjun SUN: writing – review and editing, and supervision.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

(1) Jiang SX, Guo RH. Electromagnetic shielding and corrosion resistance of electroless Ni–P/Cu–Ni multilayer plated polyester fabric. Surf Coat Technol. 2011;205:4274–9.10.1016/j.surfcoat.2011.03.033Suche in Google Scholar

(2) Liu Z, He S, Wang H, Wang X. Improvement of the electromagnetic properties of blended electromagnetic shielding fabric of cotton/stainless steel/polyester based on multi-layer M Xenes. Text Res J. 2022;92:1495–505.10.1177/00405175211062352Suche in Google Scholar

(3) Wang Y, Gordon S, Yu W, Wang Z. A highly stretchable, easily processed and robust metal wire-containing woven fabric with strain-enhanced electromagnetic shielding effectiveness. Text Res J. 2021;91:2063–73.10.1177/0040517521994891Suche in Google Scholar

(4) Zhang H, Chen J, Ji H, Wang N, Xiao H. Study on frequency selective/absorption/reflection multilayer composite flexible electromagnetic interference shielding fabric. Text Res J. 2022;92:851–9.10.1177/00405175211041718Suche in Google Scholar

(5) Liang S, Qin Y, Gao W, Wang M. A lightweight polyurethane-carbon microsphere composite foam for electromagnetic shielding. e-Polymers. 2022;22:223–33.10.1515/epoly-2022-0023Suche in Google Scholar

(6) Gao D, Guo S, Zhou Y, Lv B, Ma J. Research progress of flexible base electromagnetic shielding materials. Fine Chem. 2021;38:2161–70.Suche in Google Scholar

(7) Guo Y, Vokhidova N, Kim I, Kim H. Lightweight and thermal insulation fabric-based composite foam for high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding. Mater Chem Phys. 2023;303:1–9.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2023.127787Suche in Google Scholar

(8) Akram S, Ashraf M, Javid A, Abid HA, Ahmad S, Nawab Y, et al. Recent advances in electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding textiles: A comprehensive review. Synth Met. 2023;294:1–20.10.1016/j.synthmet.2023.117305Suche in Google Scholar

(9) Hu S, Wang D, Křemenáková D, Militký J. Washable and breathable ultrathin copper-coated nonwoven polyethylene terephthalate (PET) fabric with chlorinated poly-para-xylylene (parylene-C) encapsulation for electromagnetic interference shielding application. Text Res J. 2023;123:469–76.10.1177/00405175231168418Suche in Google Scholar

(10) Petrik IS, Eremenko AM, Naumenko AP, Rudenko AV. Effect of silver and copper nanoparticles on adsorption and fluorescence of tryptophan on the surface of bactericidal textile. Appl Nanosci. 2020;10:2557–62.10.1007/s13204-020-01315-zSuche in Google Scholar

(11) Guo RH, Jiang SX, Yuen CWM, Ng MCF, Lan JW. Optimization of electroless nickel plating on polyester fabric. Fiber Polym. 2013;14:459–64.10.1007/s12221-013-0459-ySuche in Google Scholar

(12) Ali A, Baheti V, Vik M, Militky J. Copper electroless plating of cotton fabrics after surface activation with deposition of silver and copper nanoparticles. J Phys Chem Solids. 2020;137:109–81.10.1016/j.jpcs.2019.109181Suche in Google Scholar

(13) Palanisamy S, Tunakova V, Militky J. Fiber-based structures for electromagnetic shielding comparison of different materials and textile structures. Text Res J. 2018;88:1992–2012.Suche in Google Scholar

(14) Safarova V, Tunak M, Militky J. Prediction of hybrid woven fabric electromagnetic shielding effectiveness. Text Res J. 2015;85:673–86.10.1177/0040517514555802Suche in Google Scholar

(15) Xiao H, Tang Z, Wang Q, Shi M. Research on conductive grid structure and general influence factors to shielding effectiveness of electromagnetic shielding fabrics. J Text Res. 2015;36:35–42.Suche in Google Scholar

(16) Celen R, Ulcay Y. Investigating electromagnetic shielding effectiveness of knitted fabrics made by barium titanate/polyester bicomponent yarn. J Eng Fibers Fabr. 2019;14:1–9.10.1177/1558925019837806Suche in Google Scholar

(17) Zhou L. Research on properties of wool/stainless steel blended yarns and anti- electromagnetic radiation of fabrics weaved by wool/stainless steel yarns. Wool Text J. 2006;44:18–21.Suche in Google Scholar

(18) Perumalraj R, Dasaradan BS. Electromagnetic shielding effectiveness of copper core yarn knitted fabrics. Indian J Fibre Text Res. 2009;34:149–54.Suche in Google Scholar

(19) Shyr TW, Shie JW. Electromagnetic shielding mechanisms using soft magnetic stainless-steel fiber enabled polyester textiles. J Magn Magn Mater. 2012;324:4127–32.10.1016/j.jmmm.2012.07.037Suche in Google Scholar

(20) Perumalraj R, Dasaradhan BS, Nalankilli G. Copper, stainless steel, glass core yarn, and ply yarn woven fabric composite materials properties. J Reinf Plast Compos. 2010;29:3074–82.10.1177/0731684410365007Suche in Google Scholar

(21) Özdemir H, Seçkin Uğurlu Ş, Özkurt A. The electromagnetic shielding of textured steel yarn based woven fabrics used for clothing. J Ind Text. 2014;45:416–36.10.1177/1528083715569369Suche in Google Scholar

(22) Özdemir H, Özkurt A. The effects of fabric structural parameters on the electromagnetic shielding effectiveness. Tekstil. 2013;62:133–44.Suche in Google Scholar

(23) Özdemir H, Özkurt A. The effects of weave and conductive yarn density on the electromagnetic shielding effectiveness of cellular woven fabrics. Tekst ve Konfeksiyon. 2013;23:124–35.Suche in Google Scholar

(24) Abdulla R, Delihasanlar E, Gamze F, Hayrettin Yuezer A. Investigating the electromagnetic shielding effectiveness simulations of metal composite fabrics. I C E N S. 2016;24:1724–8.Suche in Google Scholar

(25) Wang JF, Zhang Y. Design and performance anslysis of ribbed conductive knitted fabrics for electromagnetic shielding. J Zhejiang Sci Technol Univ. 2019;41:551–9.Suche in Google Scholar

(26) Su L, Liu Y, Li L. The impact of different proportions of knitting elements on the resistive properties of conductive fabrics. Text Res J. 2018;89:1–10.10.1177/0040517518758003Suche in Google Scholar

(27) Lai MF, Lou CW, Lin TA, Wang CH, Lin JH. High-strength conductive yarns and fabrics: mechanical properties, electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness, and manufacturing techniques. J Text Inst. 2019;11:891–900.Suche in Google Scholar

(28) Zhang Z, Yu J, Zhang M, Shi Q. Investigation about shielding efficiency of fabric embedded stainless steel filament using waveguide tube. J Xi’an Polytech Univ. 2013;27:573–7.Suche in Google Scholar

(29) Liu Z, Wang X. Relation between shielding effectiveness and tightness of electromagnetic shielding fabric. Text Res J. 2013;43:302–16.10.1177/1528083713477440Suche in Google Scholar

(30) Ortlek H, Alpyildiz T, Kilic G. Determination of electromagnetic shielding performance of hybrid yarn knitted fabrics with anechoic chamber method. Text Res J. 2013;83:90–9.10.1177/0040517512456758Suche in Google Scholar

(31) Liu Z, Rong X, Yang Y, Wang X. Influence of metal fiber content and arrangement on shielding effectiveness for blended electromagnetic shielding fabric. Mater Sci. 2015;21:265–70.10.5755/j01.ms.21.2.6529Suche in Google Scholar

(32) Soyaslan D, Çömlekçi S, Göktepe Ö. Determination of electromagnetic shielding performance of plain knitting and 1 × 1 rib structures with coaxial test fixture relating to ASTM D4935. J Text Inst. 2010;101:890–7.10.1080/00405000902945360Suche in Google Scholar

(33) Ortlek HG, Saracoglu OG, Saritas O, Bilgin S. Electromagnetic shielding characteristics of woven fabrics made of hybrid yarns containing metal wire. Fiber Polym. 2012;13:63–7.10.1007/s12221-012-0063-6Suche in Google Scholar

(34) Wu Y, Li Y, Ma W. Research progress of metal fiber blended electromagnetic shielding fabric. Prog Text Sci Technol. 2020;6:1688–92.Suche in Google Scholar

(35) Amini M, Nasouri K, Askari G, Shanbeh M, Khoddami A. Lightweight and highly flexible metal deposited composite fabrics for high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding at gigahertz frequency. Fiber Polym. 2022;23:800–6.10.1007/s12221-022-3183-7Suche in Google Scholar

(36) Wang D, Hu S, Kremenakova D, Militky J. Evaluation of the wearing comfort properties for winter used electromagnetic interference shielding sandwich materials. J Ind Text. 2023;53:1–25.10.1177/15280837231159869Suche in Google Scholar

(37) Tunakova V, Tunak M, Tesinova P, Seidlova M, Prochazka J. Fashion clothing with electromagnetic radiation protection: aesthetic properties and performance. Text Res J. 2020;90:2504–21.10.1177/0040517520923047Suche in Google Scholar

(38) Sundaramoorthy P, Veronika T, Jiri M. Fiber-based structures for electromagnetic shielding-comparison of different materials and textile structures. Text Res J. 2018;88:1992–2012.10.1177/0040517517715085Suche in Google Scholar

(39) Lai K, Sun RJ, Chen MY, Hui Wu C, Zha AX. Electromagnetic shielding effectiveness of fabrics with metallized polyester filaments. Text Res J. 2007;4:242–6.10.1177/0040517507074033Suche in Google Scholar

(40) Song X, Wei L, Ge M. Electromagnetic shielding effectiveness and wearing comfort of radiation protection fabrics based on gray clustering analysis. J Text Inst. 2015;10:106–12.10.1080/00405000.2014.969497Suche in Google Scholar

(41) Zhang X, Ning C. Applications of fuzzy mathematics to mechanical fault diagnosis. J Hebei Univ Sci Technol. 2002;23:55–8.Suche in Google Scholar

(42) Valko EI. The principles of textile finishing. Text Res J. 1952;22:213–22.10.1177/004051755202200306Suche in Google Scholar

(43) Yaghin RG, Sarlak P. Textile supply chain management considering carbon emissions and apparel demand fuzziness: a fuzzy mathematical programming approach. Int J Cloth Sci Technol. 2022;34:137–55.10.1108/IJCST-08-2020-0124Suche in Google Scholar

(44) Zhang X, Zhong Y. Development of woven textile electrodes with enhanced moisture-wicking properties. J Text Inst. 2021;112:983–95.10.1080/00405000.2020.1794665Suche in Google Scholar

(45) Helmi M, Tashkandi S, Wang L. Design of sports-abaya and its thermal comfort evaluation. Text Res J. 2022;92:59–69.10.1177/00405175211028802Suche in Google Scholar

(46) Majumdar A. Selection of raw materials in textile spinning industry using fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making approach. Korean Fiber Soc. 2009;3:121–7.10.1007/s12221-010-0121-xSuche in Google Scholar

(47) Wang D, Yao S. Fuzzy Information and Engineering 2010. Vol. 4, Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; 2009. p. 463–70.Suche in Google Scholar

(48) Ren W, Guan J. Investigation on principle of polarization-difference imaging in turbid conditions. Opt Commun. 2018;413:30–8.10.1016/j.optcom.2017.12.025Suche in Google Scholar

(49) Peirce FT. Geometrical Principles Applicable to the Design of Functional Fabrics. Text Res J. 1947;17:123–47.10.1177/004051754701700301Suche in Google Scholar

(50) Schulz RB, Plantz VC, Brush DR. Shielding theory and practice. IEEE Trans Electromagn Compat. 1988;30:187–20.10.1109/15.3297Suche in Google Scholar

(51) Perumalraj R, Dasaradan BS, Anbarasu R, Arokiaraj P, Harish SL. Electromagnetic shielding effectiveness of copper core-woven fabrics. J Text Inst. 2009;100:512–24.10.1080/00405000801997587Suche in Google Scholar

(52) Wu Z. Electromagnetic interference compatibility structure design. China: Atomic Energy Press; 1998. p. 97–8.Suche in Google Scholar

(53) Sun Y, Shao Y, Zheng D, Liu G, Pan X, Du Z. Measuring and multilevel fuzzy comprehensive predicting comfort parameters of soft materials by a new handle evaluation system. Text Res J. 2020;90:2727–44.10.1177/0040517520928792Suche in Google Scholar

(54) Siyao M, Liu S, Peihua Z, Hairu L. Functional investigation on automotive interior materials based on variable knitted structural parameters. Polymers. 2020;12:2455–74.10.3390/polym12112455Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(55) Wang S, Zhang T, Cheng L, Li J, Tang H, Gao M. Comprehensive performance of compound fabrics in terms of electromagnetic shielding and wearability based on the Euclid approach degree of fuzzy matter elements. J Text Inst Proc Abstr. 2016;108(3):341–6.10.1080/00405000.2016.1166820Suche in Google Scholar

(56) Ertugrul S, Ucar N. Predicting Bursting Strength of Cotton Plain Knitted Fabrics Using Intelligent Techniques. Text Res J. 2000;70:845–51.10.1177/004051750007001001Suche in Google Scholar

(57) Baghdadi R, Alibi H, Fayala F, Zeng X. Investigation on Stiffness of Finished Stretch Plain Knitted Fabrics Using Fuzzy Decision Trees and Artificial Neural Networks. Fiber Polym. 2021;22:550–8.10.1007/s12221-021-9314-8Suche in Google Scholar

(58) Zheng D, Liu Z, Zou H, Xiong Q, Liu J, Wang M, et al. Fuzzy clustering analysis of comprehensive hand of polyester fabric based on the CHES-FY system. Text Res J. 2021;91:743–51.10.1177/0040517520957409Suche in Google Scholar

(59) Jiang R, Wang Y, Jian L. Prediction of clothing comfort sensation with different activities based on fuzzy comprehensive evaluation of variable weight. Text Res J. 2022;92:3956–72.10.1177/00405175221086885Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Chitosan nanocomposite film incorporating Nigella sativa oil, Azadirachta indica leaves’ extract, and silver nanoparticles

- Effect of Zr-doped CaCu3Ti3.95Zr0.05O12 ceramic on the microstructure, dielectric properties, and electric field distribution of the LDPE composites

- Effects of dry heating, acetylation, and acid pre-treatments on modification of potato starch with octenyl succinic anhydride (OSA)

- Loading conditions impact on the compression fatigue behavior of filled styrene butadiene rubber

- Characterization and compatibility of bio-based PA56/PET

- Study on the aging of three typical rubber materials under high- and low-temperature cyclic environment

- Numerical simulation and experimental research of electrospun polyacrylonitrile Taylor cone based on multiphysics coupling

- Experimental investigation of properties and aging behavior of pineapple and sisal leaf hybrid fiber-reinforced polymer composites

- Influence of temperature distribution on the foaming quality of foamed polypropylene composites

- Enzyme-catalyzed synthesis of 4-methylcatechol oligomer and preliminary evaluations as stabilizing agent in polypropylene

- Molecular dynamics simulation of the effect of the thermal and mechanical properties of addition liquid silicone rubber modified by carbon nanotubes with different radii

- Incorporation of poly(3-acrylamidopropyl trimethylammonium chloride-co-acrylic acid) branches for good sizing properties and easy desizing from sized cotton warps

- Effect of matrix composition on properties of polyamide 66/polyamide 6I-6T composites with high content of continuous glass fiber for optimizing surface performance

- Preparation and properties of epoxy-modified thermosetting phenolic fiber

- Thermal decomposition reaction kinetics and storage life prediction of polyacrylate pressure-sensitive adhesive

- Effect of different proportions of CNTs/Fe3O4 hybrid filler on the morphological, electrical and electromagnetic interference shielding properties of poly(lactic acid) nanocomposites

- Doping silver nanoparticles into reverse osmosis membranes for antibacterial properties

- Melt-blended PLA/curcumin-cross-linked polyurethane film for enhanced UV-shielding ability

- The affinity of bentonite and WO3 nanoparticles toward epoxy resin polymer for radiation shielding

- Prolonged action fertilizer encapsulated by CMC/humic acid

- Preparation and experimental estimation of radiation shielding properties of novel epoxy reinforced with Sb2O3 and PbO

- Fabrication of polylactic acid nanofibrous yarns for piezoelectric fabrics

- Copper phenyl phosphonate for epoxy resin and cyanate ester copolymer with improved flame retardancy and thermal properties

- Synergistic effect of thermal oxygen and UV aging on natural rubber

- Effect of zinc oxide suspension on the overall filler content of the PLA/ZnO composites and cPLA/ZnO composites

- The role of natural hybrid nanobentonite/nanocellulose in enhancing the water resistance properties of the biodegradable thermoplastic starch

- Performance optimization of geopolymer mortar blending in nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber based on set pair analysis

- Preparation of (La + Nb)-co-doped TiO2 and its polyvinylidene difluoride composites with high dielectric constants

- Effect of matrix composition on the performance of calcium carbonate filled poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composites

- Low-temperature self-healing polyurethane adhesives via dual synergetic crosslinking strategy

- Leucaena leucocephala oil-based poly malate-amide nanocomposite coating material for anticorrosive applications

- Preparation and properties of modified ammonium polyphosphate synergistic with tris(2-hydroxyethyl) isocynurate for flame-retardant LDPE

- Thermal response of double network hydrogels with varied composition

- The effect of coated calcium carbonate using stearic acid on the recovered carbon black masterbatch in low-density polyethylene composites

- Investigation of MXene-modified agar/polyurethane hydrogel elastomeric repair materials with tunable water absorption

- Damping performance analysis of carbon black/lead magnesium niobite/epoxy resin composites

- Molecular dynamics simulations of dihydroxylammonium 5,5′-bistetrazole-1,1′-diolate (TKX-50) and TKX-50-based PBXs with four energetic binders

- Preparation and characterization of sisal fibre reinforced sodium alginate gum composites for non-structural engineering applications

- Study on by-products synthesis of powder coating polyester resin catalyzed by organotin

- Ab initio molecular dynamics of insulating paper: Mechanism of insulating paper cellobiose cracking at transient high temperature

- Effect of different tin neodecanoate and calcium–zinc heat stabilizers on the thermal stability of PVC

- High-strength polyvinyl alcohol-based hydrogel by vermiculite and lignocellulosic nanofibrils for electronic sensing

- Impacts of micro-size PbO on the gamma-ray shielding performance of polyepoxide resin

- Influence of the molecular structure of phenylamine antioxidants on anti-migration and anti-aging behavior of high-performance nitrile rubber composites

- Fiber-reinforced polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel via in situ fiber formation

- Preparation and performance of homogenous braids-reinforced poly (p-phenylene terephthamide) hollow fiber membranes

- Synthesis of cadmium(ii) ion-imprinted composite membrane with a pyridine functional monomer and characterization of its adsorption performance

- Impact of WO3 and BaO nanoparticles on the radiation shielding characteristics of polydimethylsiloxane composites

- Comprehensive study of the radiation shielding feature of polyester polymers impregnated with iron filings

- Preparation and characterization of polymeric cross-linked hydrogel patch for topical delivery of gentamicin

- Mechanical properties of rCB-pigment masterbatch in rLDPE: The effect of processing aids and water absorption test

- Pineapple fruit residue-based nanofibre composites: Preparation and characterizations

- Effect of natural Indocalamus leaf addition on the mechanical properties of epoxy and epoxy-carbon fiber composites

- Utilization of biosilica for energy-saving tire compounds: Enhancing performance and efficiency

- Effect of capillary arrays on the profile of multi-layer micro-capillary films

- A numerical study on thermal bonding with preheating technique for polypropylene microfluidic device

- Development of modified h-BN/UPE resin for insulation varnish applications

- High strength, anti-static, thermal conductive glass fiber/epoxy composites for medical devices: A strategy of modifying fibers with functionalized carbon nanotubes

- Effects of mechanical recycling on the properties of glass fiber–reinforced polyamide 66 composites in automotive components

- Bentonite/hydroxyethylcellulose as eco-dielectrics with potential utilization in energy storage

- Study on wall-slipping mechanism of nano-injection polymer under the constant temperature fields

- Synthesis of low-VOC unsaturated polyester coatings for electrical insulation

- Enhanced apoptotic activity of Pluronic F127 polymer-encapsulated chlorogenic acid nanoparticles through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in liver cancer cells and in vivo toxicity studies in zebrafish

- Preparation and performance of silicone-modified 3D printing photosensitive materials

- A novel fabrication method of slippery lubricant-infused porous surface by thiol-ene click chemistry reaction for anti-fouling and anti-corrosion applications

- Development of polymeric IPN hydrogels by free radical polymerization technique for extended release of letrozole: Characterization and toxicity evaluation

- Tribological characterization of sponge gourd outer skin fiber-reinforced epoxy composite with Tamarindus indica seed filler addition using the Box–Behnken method

- Stereocomplex PLLA–PBAT copolymer and its composites with multi-walled carbon nanotubes for electrostatic dissipative application

- Enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of Krestin–chitosan nanocomplex for cancer medication via activation of the mitochondrial intrinsic pathway

- Variation in tungsten(vi) oxide particle size for enhancing the radiation shielding ability of silicone rubber composites

- Damage accumulation and failure mechanism of glass/epoxy composite laminates subjected to repeated low velocity impacts

- Gamma-ray shielding analysis using the experimental measurements for copper(ii) sulfate-doped polyepoxide resins

- Numerical simulation into influence of airflow channel quantities on melt-blowing airflow field in processing of polymer fiber

- Cellulose acetate oleate-reinforced poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composite materials

- Radiation shielding capability and exposure buildup factor of cerium(iv) oxide-reinforced polyester resins

- Recyclable polytriazole resins with high performance based on Diels-Alder dynamic covalent crosslinking

- Adsorption and recovery of Cr(vi) from wastewater by Chitosan–Urushiol composite nanofiber membrane

- Comprehensive performance evaluation based on electromagnetic shielding properties of the weft-knitted fabrics made by stainless steel/cotton blended yarn

- Review Articles

- Preparation and application of natural protein polymer-based Pickering emulsions

- Wood-derived high-performance cellulose structural materials

- Flammability properties of polymers and polymer composites combined with ionic liquids

- Polymer-based nanocarriers for biomedical and environmental applications

- A review on semi-crystalline polymer bead foams from stirring autoclave: Processing and properties

- Rapid Communication

- Preparation and characterization of magnetic microgels with linear thermosensitivity over a wide temperature range

- Special Issue: Biodegradable and bio-based polymers: Green approaches (Guest Editors: Kumaran Subramanian, A. Wilson Santhosh Kumar, and Venkatajothi Ramarao)

- Synthesis and characterization of proton-conducting membranes based on bacterial cellulose and human nail keratin

- Fatigue behaviour of Kevlar/carbon/basalt fibre-reinforced SiC nanofiller particulate hybrid epoxy composite

- Effect of citric acid on thermal, phase morphological, and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactide)-b-poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(l-lactide)/thermoplastic starch blends

- Dose-dependent cytotoxicity against lung cancer cells via green synthesized ZnFe2O4/cellulose nanocomposites

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Chitosan nanocomposite film incorporating Nigella sativa oil, Azadirachta indica leaves’ extract, and silver nanoparticles

- Effect of Zr-doped CaCu3Ti3.95Zr0.05O12 ceramic on the microstructure, dielectric properties, and electric field distribution of the LDPE composites

- Effects of dry heating, acetylation, and acid pre-treatments on modification of potato starch with octenyl succinic anhydride (OSA)

- Loading conditions impact on the compression fatigue behavior of filled styrene butadiene rubber

- Characterization and compatibility of bio-based PA56/PET

- Study on the aging of three typical rubber materials under high- and low-temperature cyclic environment

- Numerical simulation and experimental research of electrospun polyacrylonitrile Taylor cone based on multiphysics coupling

- Experimental investigation of properties and aging behavior of pineapple and sisal leaf hybrid fiber-reinforced polymer composites

- Influence of temperature distribution on the foaming quality of foamed polypropylene composites

- Enzyme-catalyzed synthesis of 4-methylcatechol oligomer and preliminary evaluations as stabilizing agent in polypropylene

- Molecular dynamics simulation of the effect of the thermal and mechanical properties of addition liquid silicone rubber modified by carbon nanotubes with different radii

- Incorporation of poly(3-acrylamidopropyl trimethylammonium chloride-co-acrylic acid) branches for good sizing properties and easy desizing from sized cotton warps

- Effect of matrix composition on properties of polyamide 66/polyamide 6I-6T composites with high content of continuous glass fiber for optimizing surface performance

- Preparation and properties of epoxy-modified thermosetting phenolic fiber

- Thermal decomposition reaction kinetics and storage life prediction of polyacrylate pressure-sensitive adhesive

- Effect of different proportions of CNTs/Fe3O4 hybrid filler on the morphological, electrical and electromagnetic interference shielding properties of poly(lactic acid) nanocomposites

- Doping silver nanoparticles into reverse osmosis membranes for antibacterial properties

- Melt-blended PLA/curcumin-cross-linked polyurethane film for enhanced UV-shielding ability

- The affinity of bentonite and WO3 nanoparticles toward epoxy resin polymer for radiation shielding

- Prolonged action fertilizer encapsulated by CMC/humic acid

- Preparation and experimental estimation of radiation shielding properties of novel epoxy reinforced with Sb2O3 and PbO

- Fabrication of polylactic acid nanofibrous yarns for piezoelectric fabrics

- Copper phenyl phosphonate for epoxy resin and cyanate ester copolymer with improved flame retardancy and thermal properties

- Synergistic effect of thermal oxygen and UV aging on natural rubber

- Effect of zinc oxide suspension on the overall filler content of the PLA/ZnO composites and cPLA/ZnO composites

- The role of natural hybrid nanobentonite/nanocellulose in enhancing the water resistance properties of the biodegradable thermoplastic starch

- Performance optimization of geopolymer mortar blending in nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber based on set pair analysis

- Preparation of (La + Nb)-co-doped TiO2 and its polyvinylidene difluoride composites with high dielectric constants

- Effect of matrix composition on the performance of calcium carbonate filled poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composites

- Low-temperature self-healing polyurethane adhesives via dual synergetic crosslinking strategy

- Leucaena leucocephala oil-based poly malate-amide nanocomposite coating material for anticorrosive applications

- Preparation and properties of modified ammonium polyphosphate synergistic with tris(2-hydroxyethyl) isocynurate for flame-retardant LDPE

- Thermal response of double network hydrogels with varied composition

- The effect of coated calcium carbonate using stearic acid on the recovered carbon black masterbatch in low-density polyethylene composites

- Investigation of MXene-modified agar/polyurethane hydrogel elastomeric repair materials with tunable water absorption

- Damping performance analysis of carbon black/lead magnesium niobite/epoxy resin composites

- Molecular dynamics simulations of dihydroxylammonium 5,5′-bistetrazole-1,1′-diolate (TKX-50) and TKX-50-based PBXs with four energetic binders

- Preparation and characterization of sisal fibre reinforced sodium alginate gum composites for non-structural engineering applications

- Study on by-products synthesis of powder coating polyester resin catalyzed by organotin

- Ab initio molecular dynamics of insulating paper: Mechanism of insulating paper cellobiose cracking at transient high temperature

- Effect of different tin neodecanoate and calcium–zinc heat stabilizers on the thermal stability of PVC

- High-strength polyvinyl alcohol-based hydrogel by vermiculite and lignocellulosic nanofibrils for electronic sensing

- Impacts of micro-size PbO on the gamma-ray shielding performance of polyepoxide resin

- Influence of the molecular structure of phenylamine antioxidants on anti-migration and anti-aging behavior of high-performance nitrile rubber composites

- Fiber-reinforced polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel via in situ fiber formation

- Preparation and performance of homogenous braids-reinforced poly (p-phenylene terephthamide) hollow fiber membranes

- Synthesis of cadmium(ii) ion-imprinted composite membrane with a pyridine functional monomer and characterization of its adsorption performance

- Impact of WO3 and BaO nanoparticles on the radiation shielding characteristics of polydimethylsiloxane composites

- Comprehensive study of the radiation shielding feature of polyester polymers impregnated with iron filings

- Preparation and characterization of polymeric cross-linked hydrogel patch for topical delivery of gentamicin

- Mechanical properties of rCB-pigment masterbatch in rLDPE: The effect of processing aids and water absorption test

- Pineapple fruit residue-based nanofibre composites: Preparation and characterizations

- Effect of natural Indocalamus leaf addition on the mechanical properties of epoxy and epoxy-carbon fiber composites

- Utilization of biosilica for energy-saving tire compounds: Enhancing performance and efficiency

- Effect of capillary arrays on the profile of multi-layer micro-capillary films

- A numerical study on thermal bonding with preheating technique for polypropylene microfluidic device

- Development of modified h-BN/UPE resin for insulation varnish applications

- High strength, anti-static, thermal conductive glass fiber/epoxy composites for medical devices: A strategy of modifying fibers with functionalized carbon nanotubes

- Effects of mechanical recycling on the properties of glass fiber–reinforced polyamide 66 composites in automotive components

- Bentonite/hydroxyethylcellulose as eco-dielectrics with potential utilization in energy storage

- Study on wall-slipping mechanism of nano-injection polymer under the constant temperature fields

- Synthesis of low-VOC unsaturated polyester coatings for electrical insulation

- Enhanced apoptotic activity of Pluronic F127 polymer-encapsulated chlorogenic acid nanoparticles through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in liver cancer cells and in vivo toxicity studies in zebrafish

- Preparation and performance of silicone-modified 3D printing photosensitive materials

- A novel fabrication method of slippery lubricant-infused porous surface by thiol-ene click chemistry reaction for anti-fouling and anti-corrosion applications

- Development of polymeric IPN hydrogels by free radical polymerization technique for extended release of letrozole: Characterization and toxicity evaluation

- Tribological characterization of sponge gourd outer skin fiber-reinforced epoxy composite with Tamarindus indica seed filler addition using the Box–Behnken method

- Stereocomplex PLLA–PBAT copolymer and its composites with multi-walled carbon nanotubes for electrostatic dissipative application

- Enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of Krestin–chitosan nanocomplex for cancer medication via activation of the mitochondrial intrinsic pathway

- Variation in tungsten(vi) oxide particle size for enhancing the radiation shielding ability of silicone rubber composites

- Damage accumulation and failure mechanism of glass/epoxy composite laminates subjected to repeated low velocity impacts

- Gamma-ray shielding analysis using the experimental measurements for copper(ii) sulfate-doped polyepoxide resins

- Numerical simulation into influence of airflow channel quantities on melt-blowing airflow field in processing of polymer fiber

- Cellulose acetate oleate-reinforced poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composite materials

- Radiation shielding capability and exposure buildup factor of cerium(iv) oxide-reinforced polyester resins

- Recyclable polytriazole resins with high performance based on Diels-Alder dynamic covalent crosslinking

- Adsorption and recovery of Cr(vi) from wastewater by Chitosan–Urushiol composite nanofiber membrane

- Comprehensive performance evaluation based on electromagnetic shielding properties of the weft-knitted fabrics made by stainless steel/cotton blended yarn

- Review Articles

- Preparation and application of natural protein polymer-based Pickering emulsions

- Wood-derived high-performance cellulose structural materials

- Flammability properties of polymers and polymer composites combined with ionic liquids

- Polymer-based nanocarriers for biomedical and environmental applications

- A review on semi-crystalline polymer bead foams from stirring autoclave: Processing and properties

- Rapid Communication

- Preparation and characterization of magnetic microgels with linear thermosensitivity over a wide temperature range

- Special Issue: Biodegradable and bio-based polymers: Green approaches (Guest Editors: Kumaran Subramanian, A. Wilson Santhosh Kumar, and Venkatajothi Ramarao)

- Synthesis and characterization of proton-conducting membranes based on bacterial cellulose and human nail keratin

- Fatigue behaviour of Kevlar/carbon/basalt fibre-reinforced SiC nanofiller particulate hybrid epoxy composite

- Effect of citric acid on thermal, phase morphological, and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactide)-b-poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(l-lactide)/thermoplastic starch blends

- Dose-dependent cytotoxicity against lung cancer cells via green synthesized ZnFe2O4/cellulose nanocomposites