Preparation and characterization of polymeric cross-linked hydrogel patch for topical delivery of gentamicin

-

Javaria Arshad

, Muhammad Umer Ashraf

Abstract

This research aimed to prepare and characterize a new type of polymeric cross-linked topical hydrogel patches for the treatment of wound infections. The free radical polymerization method was used to prepare the topical hydrogel patches by utilizing natural polymers, i.e., agarose and gelatin. These natural polymers were chemically cross-linked with monomer (acrylic acid) using ammonium persulfate as an initiator via the cross-linker N,N methylene bisacrylamide. An antibiotic, i.e., gentamicin sulfate was loaded into a designed polymeric system. The polymeric cross-linked topical hydrogel patches were made in a spherical shape, which was revealed to be stable and elastic. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy, differential scanning calorimetry, thermogravimetric analysis, and X-ray powder diffraction investigation were used to characterize the topical hydrogel patches. Polymeric cross-linked hydrogel patches were evaluated for their sol–gel analysis, swelling studies, in vitro drug release studies against pH 5.5, 6.5, and 7.4, ex vivo drug permeation, and the deposition study on the rabbit’s skin by using a Franz diffusion cell. In addition, the skin irritation study and wound healing performance of drug-loaded topical patches were also assessed and compared to commercially available formulations. The topical hydrogel patches were found to be non-irritating to the skin for up to 72 h as determined by a Draize patch test and when compared to marketed formulations, these topical patches resulted in faster wound healing. The prepared formulation showed promising potential for the treatment of skin wound infection.

1 Introduction

Topical drug delivery systems are focused drug delivery systems that administer therapeutic substances directly to the skin to treat cutaneous problems (1), which are mainly used for local infections of the skin (2). Topical management is the favored direction for the local delivery of therapeutic agents because of its comfort and affordability. Smart biomaterials have recently been developed as a result of increased interest in precision medicine and personalized medication (3). The precise design of this system is to obtain an optimal medication concentration at the targeted site for a perfect duration, and gels, creams, patches, and ointments are the most often used preparations for topical medication delivery (4,5,6).

Immune responses and inflammatory cascades are frequently triggered by foreign bodies, such as implantable medical devices (7). Transdermal drug delivery systems have various benefits, including fewer side effects, better patient compliance, removal of the first-pass effect, continuous drug administration, and the ability to interrupt or discontinue therapy as needed (8). A polymeric membrane that is worn on the skin for an extended time and loaded with a reasonably high concentration of the drug allows the drug to diffuse straight through the skin and into the bloodstream (9). Hydrogel is a three-dimensional network structure able to absorb massive portions of water, formulated from natural and synthetic polymers (10,11). The formation of the system occurs because of cross-linking of polymeric chains. Cross-linking may also arise through physical interactions, covalent bonding, and hydrogen bonding or by using van der Waal interactions (10). Their three-dimensional systems can hold a lot of water attributable to their hydrophilic structure (12). Due to their high water content, hydrogels are flexible in a way that is similar to natural tissues, which reduces the risk of skin and tissue irritation (13). Many hydrogels have inherent antibacterial or antifouling properties (14). They penetrate deeply into the wound and adapt effectively to wounds of any shape (15). Drug-loaded hydrogels deliver a long-lasting local therapeutic impact on the surrounding targeted tissue while avoiding the lengthy travel of therapeutic drugs through the circulatory system, which lowers the frequency of dosing and side effects (16). A continual procedure of inflammation and repair is used in the reparative process of wound healing in order to return to normal tissue function. During this stage, a variety of cell types, including fibroblasts, endothelial cells, inflammatory cells, platelets, and epithelial cells, collaborate to restore normal functions (17). Wound healing is a complex and ongoing process influenced by a variety of elements that require a proper environment to promote the wound healing process, which involves three distinct phases: inflammation, proliferation, and maturation. Numerous solutions have been developed to heal distinct skin lesions as a result of the various types of wounds and advancements in scientific technology (18).

To prepare various dosage forms, natural polymers including chitosan, gelatin, cellulose, and agarose, are employed. They are biocompatible, biodegradable, and susceptible to enzymatic destruction, and they have the ability to repair damaged tissue without causing any adverse effects. The fabrication of hydrogel, which has hydrolyzable groups, also uses synthetic polymers (19).

Gelatin is a polymer that is found naturally. It is manufactured by the hydrolysis of collagen, which is obtained from the animal’s connective tissues and bones. Gelatin is soluble in a warm mixture of glycerol and water, and insoluble in alcohol, chloroform, and oils. It is used for gene and protein delivery and in different biomedical applications. The structure consists of residues of three amino acids: glycine, proline, and 4-hydroxyproline. The presence of higher pyrrolidone stages in gelatin results in the development of more powerful gels. Gelatin has an essential function in wound restoration because of its biodegradability and biocompatibility, and additionally, it possesses a film-forming property. Gelatin-based hydrogel, when applied, can cover and protect the wound from bacterial infections (20).

Agarose is a natural polymer derived from red seaweed (Rhodophyta). However, it is insoluble in cold water and dissolves in hot (boiling) water. It is non-toxic, clear, and odorless (21). It is biocompatible and biodegradable. Agarose has unique gel properties and forms strong gels at low concentrations (22). Agarose has wound-healing properties and is also used in other biomedical applications. Acrylic acid (AA) was used as a monomer, ammonium persulfate (APS) as a reaction initiator, and methylene bisacrylamide (MBA) as a cross-linking agent, which helped in the formation of a stable formulation (23,24).

Gentamicin is a BCS class III drug, having water solubility and weak cellular penetration. Its molecular weight is 477.596 g·mol−1 (25) and its plasma half-life is 2.3 h. It is available in injections, creams, eye drops, and ointments. The intravenous and intramuscular dosage of gentamicin is 3–5 mg·kg−1 for 12 h. The topical dose of gentamicin ointment is 1% every 8–12 h. This medication treats skin infections such as eczema, psoriasis, minor burns, cuts, and damage. It is not absorbed from the gut when administered orally, whereas its intramuscular or intravenous administration causes nephrotoxicity. Topical gentamicin is also often used to treat infected bedsores, burns, nasal staphylococcal carrier states, and other infections (26).

This study aimed to formulate polymeric cross-linked topical hydrogel patches containing gentamicin using the free radical polymerization technique. Polymeric cross-linked topical hydrogel patches containing different combinations of polymers, initiators, and cross-linkers were able to release the drug in a controlled manner at the skin’s pH. The prepared topical hydrogel patches were characterized by general characteristics such as swelling studies, sol–gel analysis, drug loading (%), in vitro drug release, ex vivo permeation, and deposition studies. Structural analyses were conducted by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), X-ray powder diffraction (PXRD), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). A wound-healing process was performed on the rabbit skin to check the efficacy of the formulated topical hydrogel patch. The designed project was able to formulate non-toxic hydrogel patches by using natural polymers. These topical hydrogel matrix patches would be the new pharmaceutical application of the cross-linked system in drug delivery technologies.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Agarose, gelatin, APS, and MBA were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, United Kingdom. AA, sodium hydroxide, monobasic potassium phosphate, and ethanol were purchased from Merck, Germany. Gentamicin was gifted by Saffron Pharmaceuticals, Pakistan, and distilled water was freely available in the postgraduate research lab of The University of Lahore.

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Preparation of polymeric cross-linked hydrogel patch

The free radical polymerization technique with various concentrations of the natural polymers (agarose and gelatin), monomer, initiator, and cross-linker, as given in Table 1, was optimized to synthesize topical hydrogel patches of gentamicin. Agarose, gelatin, AA, and MBA were used in the formulation of the patch. Agarose is a natural polymer and is derived from red seaweed. Gelatin is also a natural polymer and is obtained from the hydrolysis of collagen. AA is commonly used in the formulation of hydrogels because of its significant swelling property. It supports swelling by ionization of carboxylic groups upon electrostatic repulsion. MBA is a crosslinker and is mostly used to maintain the compact structure of the formulations. It gives rigidity to the formulations. The initiator APS assists in the formation of free radicals, which is essential for free radical polymerization. All of the ingredients used in the experiment were of analytical grade with the highest purity.

Composition of formulations with different feed ratios

| S. no. | Formulation code | Gelatin (g) | Agarose (g) | AA (g) | APS (g) | MBA (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AG-1 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 4 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 2 | AG-2 | 0.15 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 3 | AG-3 | 0.2 | 0.01 | 4 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 4 | AG-4 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 4 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 5 | AG-5 | 0.1 | 0.02 | 4 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 6 | AG-6 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 4 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 7 | AG-7 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 4 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 8 | AG-8 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 5 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 9 | AG-9 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 6 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 10 | AG-10 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 4 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 11 | AG-11 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 4 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| 12 | AG-12 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 4 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

At a specified temperature, specific quantities of natural polymers were weighed and dissolved in 5 mL of distilled water. A hot-plate magnetic stirrer was used to stir the mixture continuously until a clear solution was achieved. A specific amount of the monomer AA and initiator APS solution was prepared separately. A combination of the monomer and initiator solution was added to the polymeric solution dropwise with continuous stirring. At last, the cross-linker MBA solution was added to polymeric solutions dropwise with consistent mixing and this solution was stirred for 1 min. The mixture was then poured into a small Petri dish covered with aluminum foil, which was then put onto a water bath at 50°C for 1 h, 55°C for 2 h, and at 60°C for 20 h. Polymeric hydrogel patches were formed after 24 h. After removing the Petri dishes from the water bath, the patches were cleaned with an ethanol solution to remove the contaminants and the unreactive mixture. For 2 days, the washed hydrogel patches were dried in an oven at 40°C.

2.2.2 Weight variation and thickness

Three random patches of each formula were selected and weighed one by one, and the mean was determined. Using vernier calipers, the patch thickness was measured and recorded as the mean of five estimates covering the patch’s four corners and center (24).

2.2.3 Folding endurance

The topical patches were assessed manually by folding one patch at the same location multiple times until it either breaks or develops visible cracks, which was judged adequate to indicate good patch qualities. This is necessary to determine the sample’s ability to endure folding, which also reveals brittleness. The value of folding endurance was determined by the number of times the films can be folded at the same location without breaking (27).

2.2.4 FTIR spectroscopy

FTIR spectroscopy is used for the identification of functional groups and for the determination of the structural relation of pure components (28). The FTIR spectra of natural polymers, monomer, initiator, cross-linker, drug, and cross-linked loaded and unloaded hydrogel patches were executed at a resolution of 4 cm−1 to determine the functional groups and structural relationship. Before obtaining the spectrum range, the prepared hydrogel patches were crushed into a fine powder in a pestle and mortar. The absorption spectrum of FTIR was achieved in the field range of 4,000–400 cm−1 (19,29).

2.2.5 TGA

TGA is a thermal analysis performed on pure components to detect thermal stabilities and physiochemical changes. Natural polymers and loaded and unloaded hydrogel patch formulation were appropriately processed through TGA thermal analysis, and samples were milled and passed through sieve no. 40. Small quantities of pieces ranging from 0.5 to 5 mg were stored in platinum containers and were heated from 25°C to 400°C at 20°C‧min−1 under a nitrogen purge. The experiment was carried out in triplicate to obtain an average result (30).

2.2.6 DSC

DSC is a thermo-analytical technique carried out to determine the glass transition temperature of topical hydrogel patches. The instrument was calibrated at 156.6°C with 99% indium. Small samples ranging from 0.5 to 3 mg were ground and stored in an aluminum container. The heating rate was maintained at 20°C·min−1 in the range of 0–400°C under a stream of nitrogen. A triplicate analysis was carried out to obtain the average result (31).

2.2.7 PXRD studies

PXRD studies are a rapid analytical technique used to identify crystalline and amorphous materials and can provide information on unit cell dimensions (32). The crystallinity of the cross-linked hydrogel patch was assessed by this technique. The analyzed sample was completely ground to fine and homogenized particle size and put into the plastic sample holder of the instrument; then, the diffraction pattern was recorded and determined (20).

2.2.8 SEM

SEM is used to determine the structural behavior of the polymeric cross-linked topical hydrogel patches. The surface morphologies were determined using a JEOL analytical electron microscope. The dried hydrogel topical patches were ground to a powder form over an aluminum stub of the appropriate size using a two-fold sticky tape. A gold filter was used for the gold covering of 300A on the stub. The fundamental structure of topical patches was examined, and photomicrograph diagrams were captured and investigated (33).

2.2.9 Swelling studies

This study was used to analyze the pH sensitivity of the polymeric cross-linked topical hydrogel patches. Swelling dynamics were investigated using the phosphate buffer at pH of 5.5, 6.5, and 7.4. First, the topical patches in a dried form were weighed and submerged in three phosphate buffer solutions for 72 h at room temperature. The volume of the solution was kept at 250 mL. After different intervals of time, hydrogel patches were removed from the three buffer solutions. The patches were cleaned with blotting paper to remove the excess surface water and were weighed repeatedly at different intervals of time on an analytical balance to estimate the swelling of patches. Swelling studies were carried out until a constant weight of topical patches was attained (34). The swelling ratio (S) was calculated using the following equation:

where W s is the weight of the swollen hydrogel and W d is the weight of the dry hydrogel.

2.2.10 Sol–gel analysis

Sol–gel analysis is an effective procedure that is used to measure the uncross-linked reactants in the topical hydrogel patches. For this determination, the topical hydrogel patches were dried in an oven at 40°C; then, the dried patches were weighed (m c), and submerged in 100 mL of distilled water for 1 week with irregular stirring to eliminate the dissolvable water part. The patches were taken out after a week, set on marked Petri dishes and placed in the oven again for drying at 40°C until a steady weight (m d) was acquired (35). The percentage of the sol–gel analysis was determined using the following equations:

2.2.11 Drug loading (%)

Gentamicin was loaded on a fabricated polymeric topical hydrogel patch. About 0.3 g of the drug was dissolved in 100 mL of buffer solution at pH 7.4 and mixed thoroughly until a clear solution was obtained. The dried hydrogel topical patches were weighed before loading the drug, and the patches were submerged in the solution at room temperature for 12 h. After a particular period, the drug-loaded patches were taken out from the solution and placed on Petri dishes, and washed with distilled water to remove the excess content from the patch. Then, they were placed in an oven for drying at 40°C and weighed again after drying for determining the drug loading percentage (36).

2.2.12 In vitro drug release studies

Dissolution investigations were carried out in the dissolution apparatus to assess the percentage of drug release at pH 5.5 for normal skin and pH 7.4 for diseased skin. The hydrogel patches were weighed, and 500 mL of a phosphate buffer solution with pH values of 5.5, 6.5, and 7.4 were placed in the basket. Then, the drug-loaded hydrogel topical patches were submerged separately into it maintaining the temperature at 32 ± 0°C, and the speed of the paddle was set at 50 revolutions per min (rpm). After a specific interval of time, the sample was taken from the basket with the help of a graduated pipette and then replaced with a fresher buffer solution. Samples were filtered and diluted with the new buffer solution, and then the sample was analyzed at 207 nm wavelength using a UV–visible (UV–Vis) spectrophotometer to determine the percentage of drug release. Different mathematical models (zero order, first order, Higuchi model, Korsmeyer–Peppas model) were applied for the determination of the release pattern of formulations. The model that best fits the dissolution data reveals the drug release process (37).

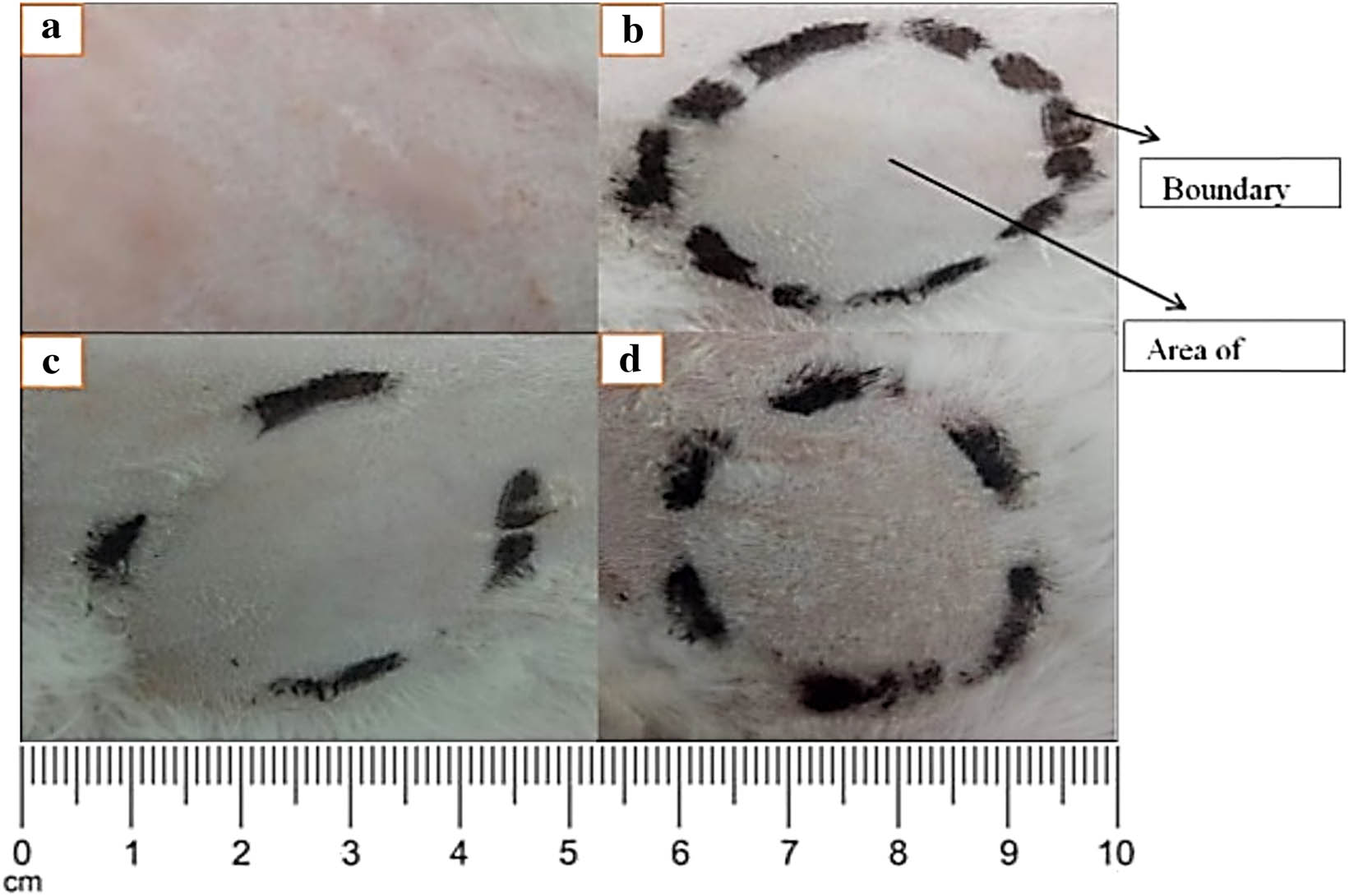

2.2.13 Skin irritation test

Topical hydrogels are utilized for dermal application, which is why the skin irritancy test is significant. The Draize patch test was used to determine the skin irritation capability of the polymeric cross-linked topical hydrogel patch. The protocol of this study was assessed and endorsed by the Pharmacy Research Ethics Committee (PREC) with reference number IREC-2022-15. This test was performed by placing the topical hydrogel patch on the back of the white albino rabbit, where the skin was made free from hair (38). Appropriate steps were taken to avoid harming the skin during shaving. The polymeric cross-linked hydrogel patch was applied within a 4 cm2 area and the area was secured with dressing or wrap. White albino rabbits with an average weight of 2 kg were chosen and separated into three groups. Group 1 served as a control bunch with no treatment, group 2 received a marketed formulation with a brand name of Genticyn®, and group 3 received an unloaded topical hydrogel patch formulation (without drug) individually. For the indication of erythema and edema, the skin was inspected at 24, 36, 48, and 72 h after application. The Draize scale was utilized to analyze the skin responses. Scores were evaluated between 0 and 4 to check the seriousness of the reactions (36).

2.2.14 Wound healing study

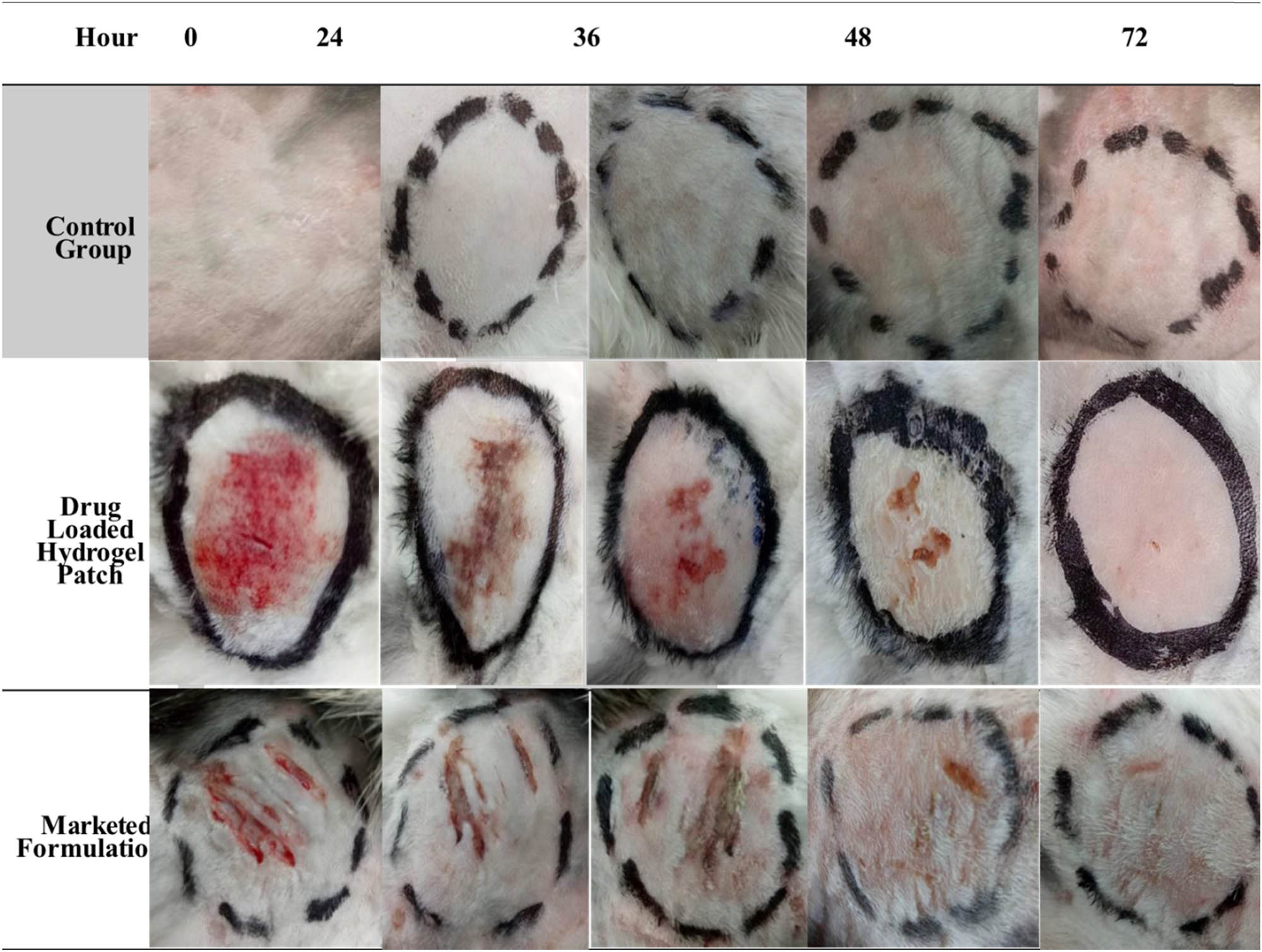

This study was performed on the rabbit’s skin to check the efficacy of hydrogel patches compared to the marketed formulation and control group with no treatment. White albino healthy rabbits of an average weight of 2 kg were chosen. Rabbits were divided into three groups. Rabbits of group 1 served as a control bunch with no treatment, group 2 received the marketed formulation, and group 3 received a topical hydrogel patch formulation containing the drug. Hair was removed from the midsection region for the formation of a wound. After 24 h, the superficial cut was created under local anesthesia. The control group was left undressed, group 2 was treated with a marketed formulation, and group 3 was treated with the drug-loaded polymeric cross-linked hydrogel patch. Then, these animals were kept in isolated cages under perception, and outcomes were studied until healing was observed (39).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Weight variation

The mean thickness was calculated after three random patches of each formulation were chosen and weighed one by one. In patches with an average weight ranging from 3.00 to 3.20 g and using vernier calipers, the patch thickness was measured and recorded as an average of five estimates covering the four corners and the center of each patch. The average thickness of the patches ranges from 2.00 to 2.50 mm, as shown in Table 2 (40).

Weight variation, thickness, and folding endurance of prepared patches

| S. no. | Formulation code | Weight variation (g) | Mean thickness (mm) | Folding endurance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AG-1 | 3.11 ± 1.09 | 2.19 ± 2.79 | 67 ± 0.79 |

| 2 | AG-2 | 3.01 ± 1.23 | 2.02 ± 2.83 | 78 ± 0.65 |

| 3 | AG-3 | 3.04 ± 1.56 | 2.04 ± 2.92 | 83 ± 0.77 |

| 4 | AG-4 | 3.13 ± 0.89 | 2.28 ± 2.88 | 66 ± 0.73 |

| 5 | AG-5 | 3.09 ± 1.22 | 2.04 ± 2.91 | 74 ± 0.91 |

| 6 | AG-6 | 3.14 ± 1.31 | 2.36 ± 2.95 | 69 ± 0.78 |

| 7 | AG-7 | 3.18 ± 1.57 | 2.04 ± 2.81 | 70 ± 0.77 |

| 8 | AG-8 | 3.09 ± 1.02 | 2.21 ± 3.05 | 80 ± 0.83 |

| 9 | AG-9 | 3.00 ± 0.92 | 2.31 ± 2.80 | 65 ± 0.89 |

| 10 | AG-10 | 3.10 ± 1.53 | 2.23 ± 2.94 | 71 ± 0.79 |

| 11 | AG-11 | 3.15 ± 1.33 | 2.04 ± 3.07 | 72 ± 0.86 |

| 12 | AG-12 | 3.20 ± 1.61 | 2.47 ± 3.02 | 69 ± 0.91 |

3.2 Folding endurance

The folding endurance of the design hydrogel patches was shown to be satisfactory, indicating that the patches created with different concentrations of natural polymers were not brittle and flexible. Folding endurance was measured manually; patches were folded 70 times maximum in formulation AG-3, and the termination point was determined if the patch showed any breaks. In the AG-3 formulation, the folding endurance was improved (Table 2).

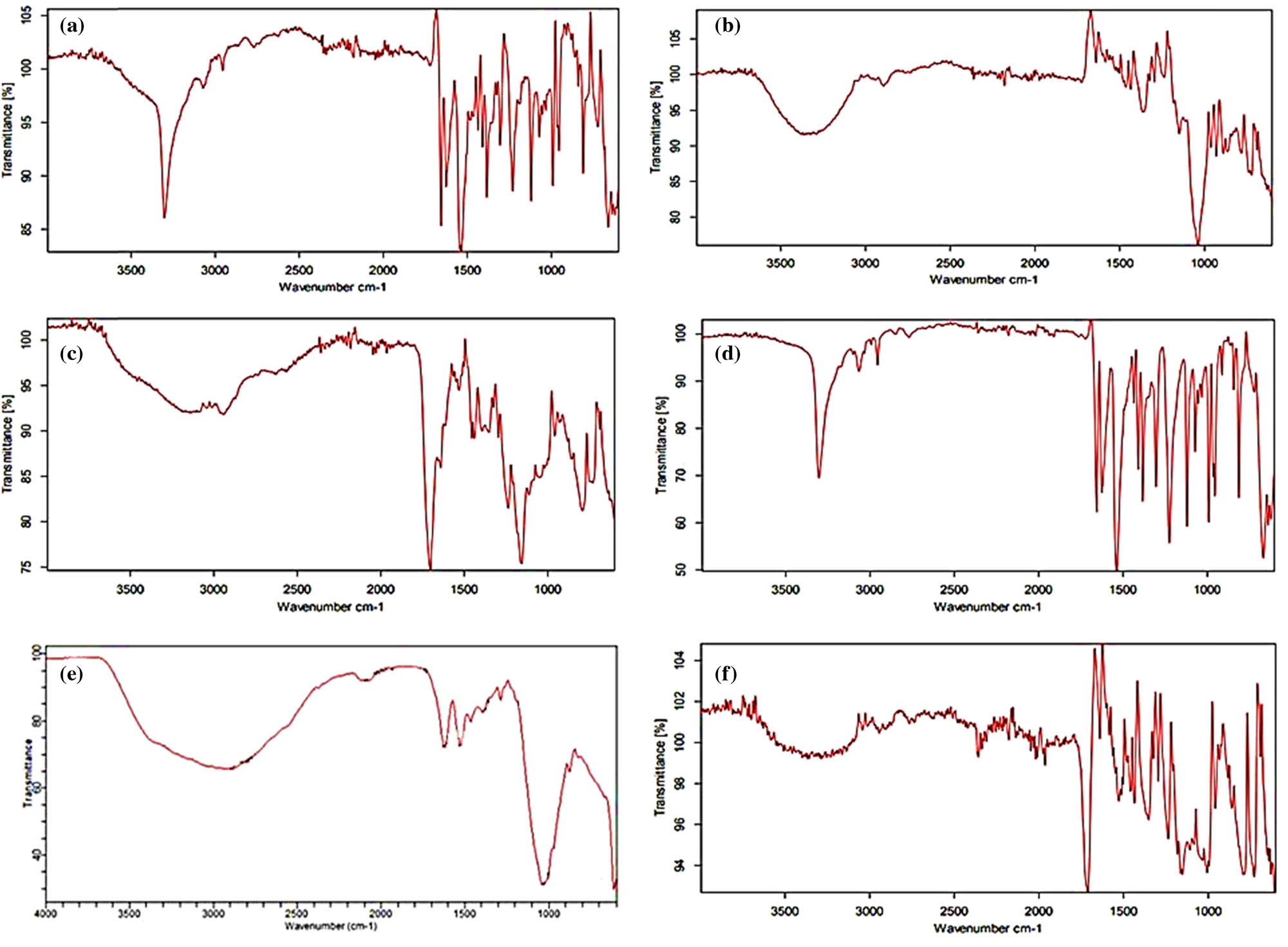

3.3 FTIR spectroscopy

The FTIR spectroscopy analysis of agarose, gelatin, gentamicin, MBA, unloaded, and drug-loaded formulations was conducted in the range of 400–6,000 cm−1. The FTIR spectra of gelatin revealed a sharp peak at 3,450 cm–1 due to secondary amide, which shows the N–H stretching and C═O stretching at 1,680 and 1,640 cm–1. The N–H bending occurred between 1,550 and 1,500 cm–1, and the N–H stretching may be overlapping with the O–H bond in the range of 3,200–3,500 cm−1. The C–H stretching occurs at 2,922 and 2,850 cm−1 (Figure 1a). Pal et al. reported similar findings in their study (20). As shown in Figure 1b, the agarose spectrum displayed a peak associated with the O–H bond stretching vibration at 3,300 cm−1. Elevations in the agarose spectra at 1,630 and 1,275 cm−1 have also shown vibrational stretchings C═C and C–O. A previous study by Felfel et al. reported similar results (41). The FTIR spectrum of gentamicin sulfate in Figure 1c showed the absorption band at 2,892 cm−1, which corresponds to the C–H stretching. The amide (N–H) bending vibrations of primary aromatic amines show a peak at 1,625 cm−1. Furthermore, the peaks at 1,528 and 1,030 cm−1 in the gentamicin spectrum corresponded to the N–H and S–O groups, respectively. In the S–O bending vibration and S–O stretch, the peaks at 605 and 1,030 cm–1 are attributed to sulfur. An additional peak in the FTIR spectra of gentamicin at 1,354 cm−1 corresponds to C–N stretching (42). The stretching band of the N–H group occurred at 3,346 cm−1 in the FTIR analysis of MBA (Figure 1d) with a prominent peak at 1,650 cm−1 because of the stretching of the distinctive carboxylic group. Symmetrical and asymmetrical stretching of the CH2 group in its structure is shown by bands occurring at 3,102 cm−1. Rani et al. observed these bands with minimal variation in their studies (43).

FTIR spectra: (a) gelatin, (b) agarose, (c) gentamicin, (d) MBA, (e) AG-9 unloaded formulation, and (f) AG-9 drug-loaded formulation.

The FTIR spectra of the unloaded formulation (Figure 1e) showed significant peaks at 3,000–2,900 cm−1, indicating CH2 (methylene) asymmetrical stretching of gelatin. The very sharp peaks appearing at 1,450 cm−1 illustrate C═O stretching. Distinct bands were discovered within the range of 970–1,215 cm−1 owing to agarose polysaccharides. Minor shifts in individual component peaks were seen, indicating crosslinking of the polymeric chains; therefore, the cross-linked polymeric patches have been validated by these FTIR observations (44). As shown in Figure 1f, gentamicin-loaded hydrogel patches displayed a distinctive band at 3,200 cm−1, representing the stretching of the N–H group, and another noticeable peak at 1,700 cm−1, representing the stretching of the carbonyl group (C═O) (45), which demonstrates drug integration in the formulation. Elevations in the FTIR spectra that appeared between 1,190 and 1,200 cm−1 showed C–O–C stretching (46).

3.4 TGA

TGA is a continuous procedure that involves measuring the weight as the temperature increases in the form of planned heating. TGA helps to study the thermal decomposition of gelatin, agarose, and the formulation. The gelatin TGA thermogram revealed two significant phases of weight loss (Figure 2a). The first 40% weight loss occurred at 253.5°C due to the water loss, and the second weight loss began at 330°C and continued until 440°C, during which 60% of the weight was lost owing to gelatin degradation. The second weight loss occurred between 300°C and 440°C, caused by the gelatin network’s thermal breakdown (47). As shown in Figure 2b, the TGA thermogram of agarose usually reflects changes in the structure or content. The desorption of water bound by hydrogen bonds is due to early slight weight loss of agarose between 30°C and 115°C. At temperatures of 270–330°C, a substantial weight loss of agarose occurs, and then 100% weight loss occurred between 330°C and 500°C. These findings are almost identical to Zhang et al.’s study that showed the early weight loss of agarose occurred between 30°C and 100°C (48).

TGA thermogram: (a) gelatin, (b) agarose, and (c) AG-9 formulations.

As shown in Figure 2c, the TGA of the AG-9 hydrogel formulation demonstrated that weight loss occurred in three steps when exposed to extreme temperatures. At 200°C, a 30% weight loss occurred; in the temperature range of 240.52–371.69°C, the second weight loss appeared; and at 420–500°C, there was an extensive loss, indicating that the formulation had completely degraded. These results showed that the formed AG hydrogel blend has better thermal stability than the individual reactants.

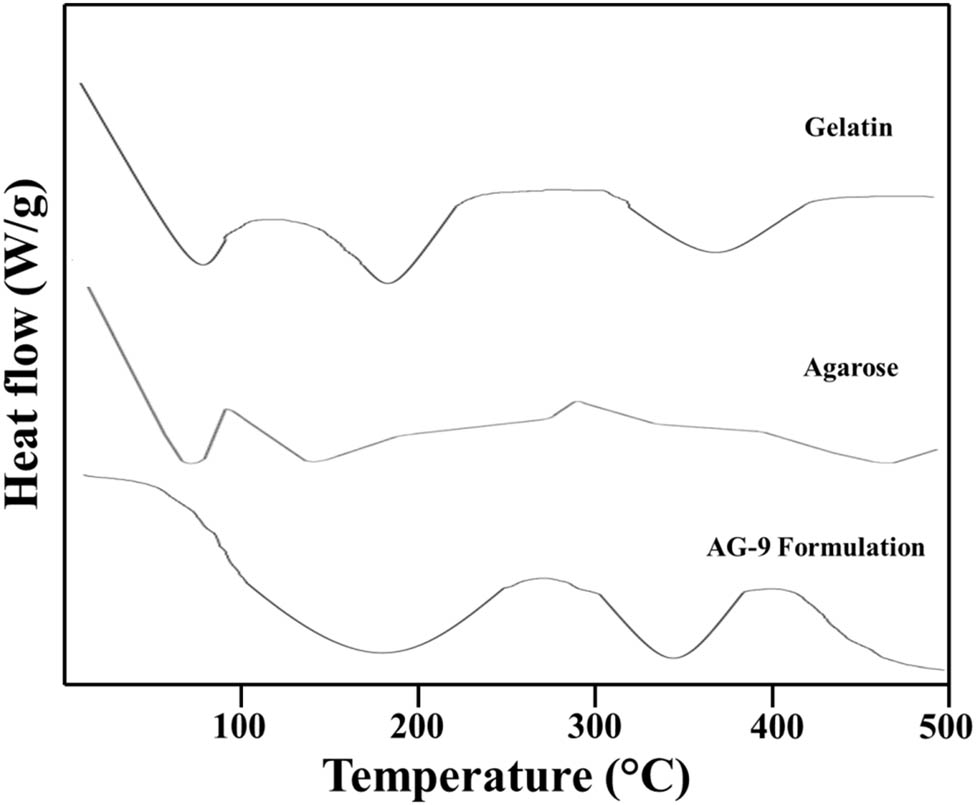

3.5 DSC analysis

The DSC thermogram of gelatin showed a prominent endothermic peak near 100°C, corresponding to the loss of moisture. In pure gelatin, endothermic phase changes were detected at 155.18°C, 260.47°C, and 330.36°C (49). Agarose exhibited sharp endothermic peaks at about 75°C causing a transition from gel to sol, i.e., the melting of the gel. Near 100°C, a sharp exothermic peak corresponds to moisture loss. A sharp exothermic peak was found near 300°C and was attributed to the breakage of connectivity between polymeric networks (50). The DSC thermogram of the formulation displayed a broad peak in the temperature range of 415–440.22°C, corresponding to the bond breakdown within the polymeric system. In comparison to the DSC thermograms of gelatin and agarose, the AG-9 formulation has superior thermal stability, as shown in Figure 3.

DSC thermogram of gelatin, agarose, and AG-9 formulation.

3.6 XRD studies

The amorphous nature and crystallinity of the materials were demonstrated by analyzing the XRD of gelatin, agarose, and the prepared formulation of the hydrogel patches, as shown in Figure 4. The XRD graph of gelatin showed no major peak, indicating that it is amorphous in nature. A sharp peak was found at 2θ = 18.65° in XRD patterns of agarose, indicating that the agarose sample is crystalline in nature. The XRD pattern of the formulation displayed a sharp peak at 20.1°, indicating that the formulation is crystalline in nature. The entire diffraction graph, on the other hand, showed a sharp and broad peak from 18° to 20°. This was mostly due to the rearrangement of polysaccharide chains during the gel formation process, which resulted in a change in the crystalline structure and shows that the AG-9 formulation has both crystalline and amorphous polymeric structures. Su et al. reported a similar study of an agarose-loaded formulation, which showed the crystalline and amorphous nature of the formulation (51).

XRD spectra of gelatin, agarose, and AG-9 formulation.

3.7 SEM

SEM analysis was used to identify the morphological aspects of the polymeric hydrogel patches. The micrographs of the topical hydrogel patches at two magnifications, 500×, and 1,000×, are shown in Figure 5. The topical hydrogel patches have a rough, porous surface, as demonstrated by the SEM scan. There were fissures all around the uneven textures, which might be due to the collapse of the polymeric structure during the drying process. These characteristics lead to greater water penetration in the polymeric network and the possibility of water absorption in the hydrogels, which can cause the formulation to swell. In a recent study, Bao et al. discovered the same surface characteristics (52).

Surface morphology of AG-9 formulations at different magnifications: (a) 2,500×, (b) 1,000×, (c) 2,500×, and (d) 500×.

3.8 Swelling study

The effect of varying pH on the swelling behavior of topical hydrogel patches was investigated (Figure 6). Due to the standard diseased skin conditions, pH values of 5.5, 6.5, and 7.4 were chosen. Hydrogel patches were synthesized using varying amounts of the polymers, such as agarose and gelatin (AG-1 to AG-3), agarose from AG-4 to AG-6, and monomers such as AA (AG-7 to AG-9), and cross-linker MBA (AG-10 to AG-12). The swelling performance was investigated using whole gelatin and agarose formulations ranging from 1 to 12. The swelling was observed till the weight was equalized. The hydrogel patches significantly expanded and reached equilibrium in about 72 h. Figure 7 depicts the swelling of hydrogel patches at pH values of 5.5, 6.5, and 7.4. According to the findings, swelling is reduced as gelatin quantity is increased. Swelling decreased as the agarose concentration increased. As a result, the cross-linked swelling ratio of agarose was inversely related to the gelation degree. AG-9 showed maximum swelling due to a higher concentration of AA. As the concentration of AA increases, the number of carboxylic groups also increases, responsible for the swelling of the cross-linked hydrogel patches (53).

A swelling study of the AG-9 hydrogel patch at different pH values: (a) 5.5, (b) 6.5, and (c) 7.4.

Swelling dynamics graph of formulations (AG-1-12) at different pH values: (a) 5.5, (b) 6.5, and (c) pH 7.4.

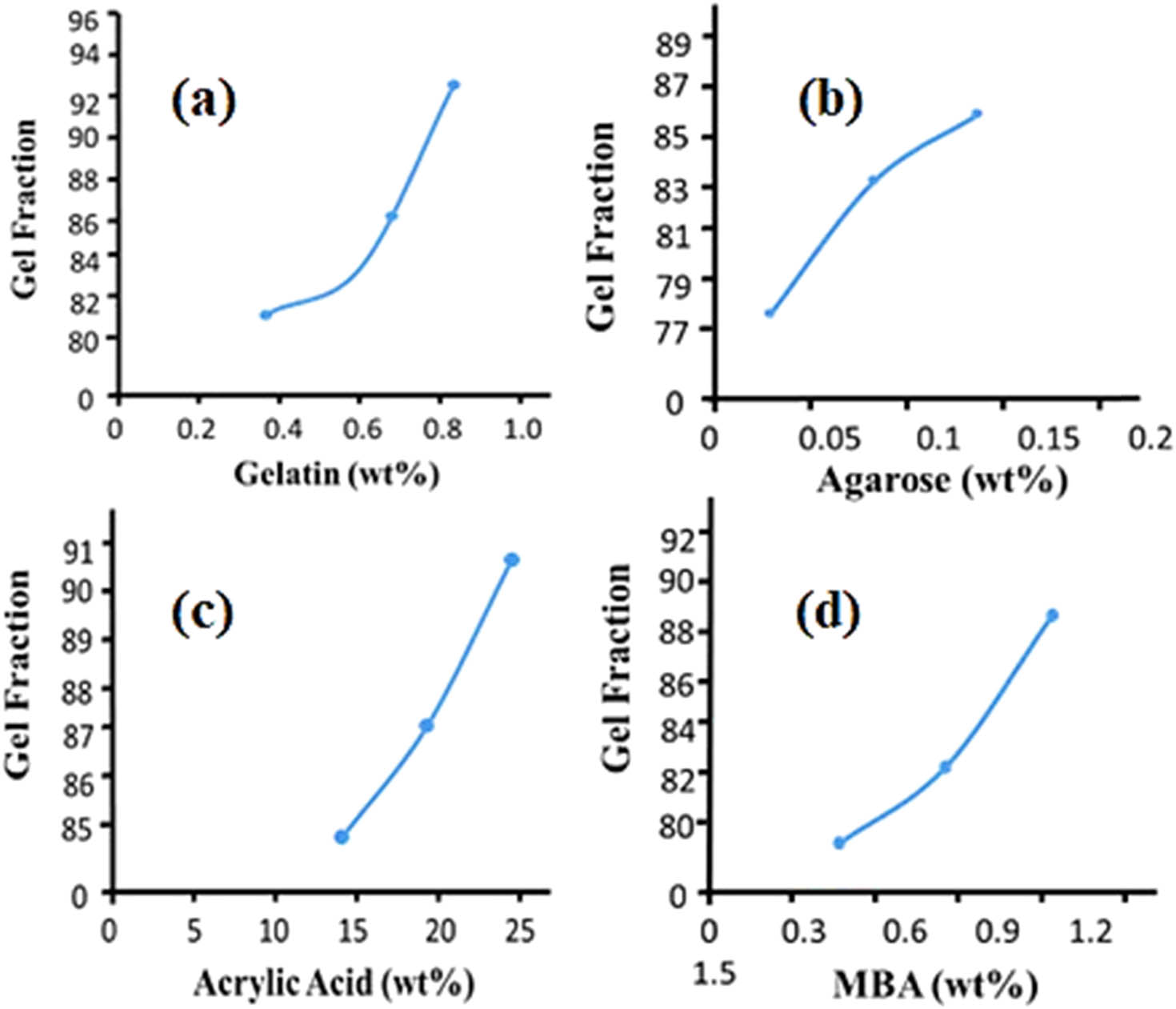

3.9 Sol–gel analysis

The gel fraction improved in the quality of gelatin as the series progressed from AG-1 to AG-3 with a gel fraction of 93.5%; AG-3 has the most significant gel fraction. By increasing the amount of agarose in the formulation series from AG-4 to AG-6, the gel fraction also improved from 83% to 85%. While maintaining the polymer, when the concentration of AA was increased from AG 7 to AG 9, there was a progressive improvement in the gel fraction from 83.4% to 84.3% when the monomer concentration was increased. This is because when the concentration of both polymer and monomer increases, the number of available active sites and functional groups for free radical polymerization increases, resulting in a higher gel fraction and a more stable hydrogel.

Furthermore, with increasing MBA content, the gel fraction increased from 79.3% to 85.5% in formulation series AG-10 to AG-12 (Figure 8). Using the sol fraction method, the number of unreacted reactants (polymer, monomer, cross-linker) used in the production of polymeric hydrogel topical patches was also determined. The findings showed a sizable sol percentage, demonstrating the successful formation of a cross-linked polymeric hydrogel network in transdermal patches. In their studies, other scientists have reported comparable results (54).

Gel fraction of (a) gelatin, (b) agarose, (c) acrylic acid, and (d) MBA.

3.9.1 Influence of reacting components on the gel percentage, yield percentage, and gelling time

The effect of different components, such as cross-linker (MBA), monomer (AA), and polymer (gelatin, agarose), on multiple properties of the AG hydrogel patches is shown in Figure 9. The gel and yield percentage increased with increased quantities of polymers and the cross-linker. However, gelling time was reduced because a high MBA concentration causes an increase in the reaction polymerization rate, resulting in rapid polymeric gel synthesis. The increase in gel and yield percentages may be because as the concentrations of the polymers and cross-linker were increased, a dense formulation developed with compact mass. Moreover, with an increase in the concentrations of the polymers, a large number of active sites were made available for the monomer AA for early polymerization. Because of these factors, the gel and the yield percentages were increased with increasing the concentrations of the polymers and cross-linker.

Gel%, yield%, and gel time of (a) gelatin, (b) acrylic acid, (c) agarose, and (d) MBA.

3.10 Drug loading

Drug loading in the formulation was evaluated, and results obtained show that the AG-9 formulation has the maximum drug loading, i.e., 98%.

3.11 In vitro drug release studies

Among all formulations, AG-9 showed maximum drug release, i.e., 97% due to the increased amount of monomer (AA), as shown in Figure 10. This could be due to an increase in the hydrophilic group (COOH), where AG-9 has shown maximum drug release at pH 7.4. The deprotonation of carboxyl groups, which are found in polymeric networks, and the transformation into carboxylate anions (COO−) at pH 7.4, may be associated with an increase in drug release. The presence of carboxylate anions (COO−) causes an electrostatic attraction between the ions, which expands and significantly swells the chains. As a result, a large amount of dissolution medium enters into the system and an optimum degree of interaction between the dissolution medium and the loaded drug was identified. As a result, a maximum amount of drug was released. The concentration of the cross-linker was increased in formulations from AG-10 to AG-12, resulting in a decrease in drug release from 93% to 86%. As the concentration of MBA increases, the hydrogen bonding between OH groups strengthens, resulting in a reduction in the electrostatic repulsive forces, causing the polymeric network stronger and denser (55). All 12 formulations followed a zero-order kinetic model with a regression coefficient (R 2) in the range of 0.9433–0.9962. Our findings showed that gentamicin release from the hydrogel matrix of the topical patch is independent of drug concentration and follows a diffusion process involving the formation of pores in the polymeric matrix (Table 3). As a result, our formulation had the right pore structure for water absorption and drug diffusion from the matrix (24).

Drug release (%) of formulations (AG-1–12) at different pH values.

Kinetic modeling on gentamicin-loaded topical patches

| Formulation | Zero order | First order | Higuchi model | Korsmeyer–Peppas | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R 2 | R 2 | R 2 | R 2 | n | |

| AG-1 | 0.9921 | 0.9665 | 0.9231 | 0.9112 | 0.541 |

| AG-2 | 0.9841 | 0.9589 | 0.9209 | 0.9102 | 0.553 |

| AG-3 | 0.9713 | 0.9541 | 0.9123 | 0.9021 | 0.521 |

| AG-4 | 0.9654 | 0.9477 | 0.9230 | 0.9121 | 0.529 |

| AG-5 | 0.9542 | 0.9406 | 0.9201 | 0.8487 | 0.535 |

| AG-6 | 0.9478 | 0.9321 | 0.9121 | 0.9012 | 0.557 |

| AG-7 | 0.9833 | 0.9651 | 0.9221 | 0.9116 | 0.531 |

| AG-8 | 0.9851 | 0.9633 | 0.9321 | 0.9031 | 0.629 |

| AG-9 | 0.9962 | 0.9754 | 0.9441 | 0.9240 | 0.689 |

| AG-10 | 0.9765 | 0.9664 | 0.9120 | 0.9010 | 0.533 |

| AG-11 | 0.9591 | 0.9321 | 0.9026 | 0.8476 | 0.556 |

| AG-12 | 0.9433 | 0.9201 | 0.9016 | 0.8465 | 0.478 |

3.12 Primary skin irritation study of topical patches

To assess the irritation potential of the formulation, the topical patch was applied and evaluated according to the guidelines established by the University of Lahore’s PREC. The application site was monitored for 24, 36, 48, and 72 h. After 72 h, the rabbit’s skin showed no signs of erythema or irritation (Figure 11). As a result, the topical patch’s components are safer for topical distribution. The skin’s acceptance of the topical hydrogel patch was found to be favorable (36).

Skin irritation test of the topical hydrogel patch.

3.13 Wound healing study of topical patches

The goal of this study was to contrast the developed topical hydrogel patch of gentamicin with the commercial version in terms of its efficacy to treat wounds. After 72 h, it was discovered that the hydrogel topical patch formulation’s wound healing capability was greater than that of the commercial formulation and containing gentamicin (Figure 12).

Wound healing performance of the optimized drug-loaded hydrogel patch formulation with the control group and marketed formulation.

4 Conclusion

Using the free radical polymerization technique, polymeric cross-linked gentamicin-loaded topical hydrogel patches were successfully formulated, which could serve as a topical delivery system at the wound site, curing the infection and increasing healing efficiency through contact. Morphological, structural, thermal, and sol–gel analyses validated the stability of the formed topical hydrogel polymeric system. Topical hydrogel patches were also evaluated via the ex vivo drug deposition study across the skin of rabbits. Several characteristics of the polymeric hydrogel patches, such as swelling study and in vitro release of the drug, revealed pH sensitivity and have shown the best swelling and excellent drug loading at pH 7.4, which shows its effectiveness for the wounded skin as the pH of the skin increases in the infectious wound. AG-9 formulation containing the lowest polymers and cross-linker concentration and highest monomer concentration has shown the highest swelling and percentage drug release. Topical patches have shown no sign of irritation or erythema on the skin after application for up to 72 h. When compared to traditional marketed formulations, these hydrogel patches showed faster wound healing and increased retention in the skin, indicating a superior potential for topical medication delivery with lower dosing frequency and improved patient compliance. Because of its improved efficacy, this system will play a greater role in the management and treatment of wound infection.

-

Funding information: The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for funding this work through the project number (RSP2023R457).

-

Author contributions: Javaria Arshad, Kashif Barkat, Muhammad Umer Ashraf, Syed Faisal Badshah: conceptualization, writing – original draft, formal analysis, investigations; Zulcaif Ahmad, Irfan Anjum, Maryam Shabbir, Yasir Mehmood, Ikrima Khalid, Nadia Shamshad Malik: funding acquisition, resources, project administration, writing – review and editing, data validation, data curation, supervision; Yousef A. Bin Jardan, Hiba-Allah Nafidi, Mohammed Bourhia: writing – review and editing, data validation, data curation.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

(1) Verma A, Singh S, Kaur R, Jain UK. Topical gels as drug delivery systems: A review. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2013;23(2):374–82.Search in Google Scholar

(2) Bhowmik D. Recent advances in novel topical drug delivery system. Pharma Innov. 2012;1:9.Search in Google Scholar

(3) Bordbar-Khiabani A, Gasik M. Smart hydrogels for advanced drug delivery systems. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(7):3665.10.3390/ijms23073665Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(4) Ahmad Z, Khan MI, Siddique MI, Sarwar HS, Shahnaz G, Hussain SZ, et al. Fabrication and characterization of thiolated chitosan microneedle patch for transdermal delivery of tacrolimus. Aaps Pharmscitech. 2020;21:1–12.10.1208/s12249-019-1611-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(5) Singh Malik D, Mital N, Kaur G. Topical drug delivery systems: a patent review. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2016;26(2):213–28.10.1517/13543776.2016.1131267Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(6) Khalid A, Sarwar HS, Sarfraz M, Sohail MF, Jalil A, Jardan YA, et al. Formulation and characterization of thiolated chitosan/polyvinyl acetate based microneedle patch for transdermal delivery of dydrogesterone. Saudi Pharm J. 2023;31(5):669–7710.1016/j.jsps.2023.03.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(7) Alshimaysawee S, Fadhel Obaid R, Al-Gazally ME, Alexis Ramírez-Coronel A, Bathaei MS. Recent advancements in metallic drug-eluting implants. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(1):223.10.3390/pharmaceutics15010223Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(8) Kulkarni RV, Wagh YJ. Crosslinked alginate films as rate controlling membranes for transdermal drug delivery application. J Macromol Sci Part A. 2010;47(7):732–7.10.1080/10601325.2010.483620Search in Google Scholar

(9) Kulkarni RV, Sreedhar V, Mutalik S, Setty CM, Sa B. Interpenetrating network hydrogel membranes of sodium alginate and poly(vinyl alcohol) for controlled release of prazosin hydrochloride through skin. Int J Biol Macromol. 2010;47(4):520–7.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2010.07.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(10) Zaman M, Siddique W, Waheed S, Sarfraz R, Mahmood A, Qureshi J, et al. Hydrogels, their applications and polymers used for hydrogels: A review. Int J Biol Pharm Allied Sci. 2015;4:6581–603.Search in Google Scholar

(11) Ahsan A, Tian W-X, Farooq MA, Khan DH. An overview of hydrogels and their role in transdermal drug delivery. Int J Polym Mater Polym Biomater. 2021;70(8):574–84.10.1080/00914037.2020.1740989Search in Google Scholar

(12) Carrillo-Castillo TD, Luna-Velasco A, Zaragoza-Contreras EA, Castro-Carmona JS. Thermosensitive hydrogel for in situ-controlled methotrexate delivery. e-Polymers. 2021;21(1):910–20.10.1515/epoly-2021-0085Search in Google Scholar

(13) Kulkarni RV, Wagh YJ, Setty CM, Sa B. Development and characterization of sodium alginate-hydroxypropyl methylcellulose-polyester multilayered hydrogel membranes for drug delivery through skin. Polym Technol Eng. 2011;50(5):490–7.10.1080/03602559.2010.543244Search in Google Scholar

(14) Xiao S, Zhao Y, Jin S, He Z, Duan G, Gu H, et al. Regenerable bacterial killing–releasing ultrathin smart hydrogel surfaces modified with zwitterionic polymer brushes. e-Polymers. 2022;22(1):719–32.10.1515/epoly-2022-0055Search in Google Scholar

(15) Qin X, Mukerabigwi JF, Ma M, Huang R, Ma M, Huang X, et al. In situ photo-crosslinking hydrogel with rapid healing, antibacterial, and hemostatic activities. e-Polymers. 2021;21(1):606–15.10.1515/epoly-2021-0062Search in Google Scholar

(16) Choe R, Yun SI. Fmoc-diphenylalanine-based hydrogels as a potential carrier for drug delivery. e-Polymers. 2020;20(1):458–68.10.1515/epoly-2020-0050Search in Google Scholar

(17) Elblbesy MA, Hanafy TA, Shawki MM. Polyvinyl alcohol/gum Arabic hydrogel preparation and cytotoxicity for wound healing improvement. e-Polymers. 2022;22(1):566–76.10.1515/epoly-2022-0052Search in Google Scholar

(18) Rezvani Ghomi E, Khalili S, Nouri Khorasani S, Esmaeely Neisiany R, Ramakrishna S. Wound dressings: Current advances and future directions. J Appl Polym Sci. 2019;136(27):47738.10.1002/app.47738Search in Google Scholar

(19) Zulcaif, Zafar N, Mahmood A, Sarfraz RM, Elaissari A. Simvastatin loaded dissolvable microneedle patches with improved pharmacokinetic performance. Micromachines. 2022;13(8):1304.10.3390/mi13081304Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(20) Pal K, Banthia AK, Majumdar DK. Preparation and characterization of polyvinyl alcohol-gelatin hydrogel membranes for biomedical applications. Aaps Pharmscitech. 2007;8:E142–6.10.1208/pt080121Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(21) Imani R, Emami SH, Moshtagh PR, Baheiraei N, Sharifi AM. Preparation and characterization of agarose-gelatin blend hydrogels as a cell encapsulation matrix: An in-vitro study. J Macromol Sci Part B. 2012;51(8):1606–16.10.1080/00222348.2012.657110Search in Google Scholar

(22) Barrangou LM, Daubert CR, Foegeding EA. Textural properties of agarose gels. I. Rheological and fracture properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2006;20(2–3):184–95.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2005.02.019Search in Google Scholar

(23) Chen P, Lou C, Zhang L, Chu B, Bao L, Tang S, et al. Notice of retraction: The sprayable agarose/gelatin as wound skin dressing. In: 2011 5th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering. IEEE; 2011.10.1109/icbbe.2011.5780276Search in Google Scholar

(24) El-Gendy N, Abdelbary G, El-Komy M, Saafan A. Design and evaluation of a bioadhesive patch for topical delivery of gentamicin sulphate. Curr Drug Delivery. 2009;6(1):50–7.10.2174/156720109787048276Search in Google Scholar

(25) Dorati R, DeTrizio A, Spalla M, Migliavacca R, Pagani L, Pisani S, et al. Gentamicin Sulfate PEG-PLGA/PLGA-H nanoparticles: Screening design and antimicrobial effect evaluation toward clinic bacterial isolates. Nanomaterials. 2018;8(1):37.10.3390/nano8010037Search in Google Scholar

(26) Oesterreicher Z, Lackner E, Jäger W, Höferl M, Zeitlinger M. Lack of dermal penetration of topically applied gentamicin as pharmacokinetic evidence indicating insufficient efficacy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(10):2823–9.10.1093/jac/dky274Search in Google Scholar

(27) Takeuchi Y, Ikeda N, Tahara K, Takeuchi H. Mechanical characteristics of orally disintegrating films: Comparison of folding endurance and tensile properties. Int J Pharm. 2020;589:119876.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119876Search in Google Scholar

(28) Badshah SF, Minhas MU, Khan KU, Barkat K, Abdullah O, Munir A, et al. Structural and in-vitro characterization of highly swellable β-cyclodextrin polymeric nanogels fabricated by free radical polymerization for solubility enhancement of rosuvastatin. Particulate Sci Technol. 2023;1–15.10.1080/02726351.2023.2183161Search in Google Scholar

(29) Sami AJ, Khalid M, Jamil T, Aftab S, Mangat SA, Shakoori A, et al. Formulation of novel chitosan guargum based hydrogels for sustained drug release of paracetamol. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;108:324–32.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.12.008Search in Google Scholar

(30) Ray M, Pal K, Anis A, Banthia A. Development and characterization of chitosan-based polymeric hydrogel membranes. Designed Monomers Polym. 2010;13(3):193–206.10.1163/138577210X12634696333479Search in Google Scholar

(31) Yoshida H, Hatakeyama T, Hatakeyama H. Characterization of water in polysaccharide hydrogels by DSC. J Therm Anal Calorim. 1993;40(2):483–9.10.1007/BF02546617Search in Google Scholar

(32) Badshah SF, Akhtar N, Minhas MU, Khan KU, Khan S, Abdullah O, et al. Porous and highly responsive cross-linked β-cyclodextrin based nanomatrices for improvement in drug dissolution and absorption. Life Sci. 2021;267:118931.10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118931Search in Google Scholar

(33) Kim SH, Chu CC. Synthesis and characterization of dextran–methacrylate hydrogels and structural study by SEM. J Biomed Mater Res An Off J Soc Biomater Jap Soc Biomater. 2000;49(4):517–27.10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(20000315)49:4<517::AID-JBM10>3.0.CO;2-8Search in Google Scholar

(34) Karadaǧ E, Saraydin D, Çetinkaya S, Güven O. In vitro swelling studies and preliminary biocompatibility evaluation of acrylamide-based hydrogels. Biomaterials. 1996;17(1):67–70.10.1016/0142-9612(96)80757-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(35) Collinson MM. Sol-gel strategies for the preparation of selective materials for chemical analysis. Crit Rev Anal Chem. 1999;29(4):289–311.10.1080/10408349891199310Search in Google Scholar

(36) Ahmad S, Usman Minhas M, Ahmad M, Sohail M, Abdullah O, Khan KU, et al. Topical hydrogel patches of vinyl monomers containing mupirocin for skin injuries: Synthesis and evaluation. Adv Polym Technol. 2018;37(8):3401–11.10.1002/adv.22124Search in Google Scholar

(37) Dreiss CA. Hydrogel design strategies for drug delivery. Curr Opcolloid Interf Sci. 2020;48:1–17.10.1016/j.cocis.2020.02.001Search in Google Scholar

(38) Zulcaif Z, Zafar N, Mahmood A, Sarfraz RM. Toxicological evaluation of natural and synthetic polymer based dissolvable microneedle patches having variable release profiles. Cellulose Chem Technol. 2022;56(7–8):777–86.10.35812/CelluloseChemTechnol.2022.56.69Search in Google Scholar

(39) Galer BS, Rowbotham M, Perander J, Devers A, Friedman E. Topical diclofenac patch relieves minor sports injury pain: results of a multicenter controlled clinical trial. J Pain Symp Manag. 2000;19(4):287–94.10.1016/S0885-3924(00)00125-1Search in Google Scholar

(40) Darwhekar G, Jain DK, Patidar VK. Formulation and evaluation of transdermal drug delivery system of clopidogrel bisulfate. Asian J Pharm Life Sci ISSN. 2011;2231:4423.Search in Google Scholar

(41) Felfel RM, Gideon-Adeniyi MJ, Hossain KMZ, Roberts GA, Grant DM. Structural, mechanical and swelling characteristics of 3D scaffolds from chitosan-agarose blends. Carbohydr Polym. 2019;204:59–67.10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.10.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(42) Batul R, Bhave M, Mahon PJ, Yu A. Polydopamine nanosphere with in-situ loaded gentamicin and its antimicrobial activity. Molecules. 2020;25(9):2090.10.3390/molecules25092090Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(43) Rani U, Karabacak M, Tanrıverdi O, Kurt M, Sundaraganesan N. The spectroscopic (FTIR, FT-Raman, NMR and UV), first-order hyperpolarizability and HOMO–LUMO analysis of methylboronic acid. Spectrochim Acta Part A: Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2012;92:67–77.10.1016/j.saa.2012.02.036Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(44) Zamora-Mora V, Velasco D, Hernández R, Mijangos C, Kumacheva E. Chitosan/agarose hydrogels: Cooperative properties and microfluidic preparation. Carbohydr Polym. 2014;111:348–55.10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.04.087Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(45) Kondaveeti S, de Assis Bueno PV, Carmona-Ribeiro AM, Esposito F, Lincopan N, Sierakowski MR, et al. Microbicidal gentamicin-alginate hydrogels. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;186:159–67.10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.01.044Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(46) Zhang J, Tan W, Li Q, Liu X, Guo Z. Preparation of cross-linked chitosan quaternary ammonium salt hydrogel films loading drug of gentamicin sulfate for antibacterial wound dressing. Mar Drugs. 2021;19(9):479.10.3390/md19090479Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(47) Sadeghi M, Heidari B. Crosslinked graft copolymer of methacrylic acid and gelatin as a novel hydrogel with pH-responsiveness properties. Materials. 2011;4(3):543–52.10.3390/ma4030543Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(48) Zhang L-M, Wu C-X, Huang J-Y, Peng X-H, Chen P, Tang S-Q, et al. Synthesis and characterization of a degradable composite agarose/HA hydrogel. Carbohydr Polym. 2012;88(4):1445–52.10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.02.050Search in Google Scholar

(49) Cao J, Wu P, Cheng Q, He C, Chen Y, Zhou J, et al. Ultrafast fabrication of self-healing and injectable carboxymethyl chitosan hydrogel dressing for wound healing. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13(20):24095–105.10.1021/acsami.1c02089Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(50) Onuki Y, Nishikawa M, Morishita M, Takayama K. Development of photocrosslinked polyacrylic acid hydrogel as an adhesive for dermatological patches: Involvement of formulation factors in physical properties and pharmacological effects. Int J Pharm. 2008;349(1–2):47–52.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.07.021Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(51) Su T, Zhang M, Zeng Q, Pan W, Huang Y, Qian Y, et al. Mussel-inspired agarose hydrogel scaffolds for skin tissue engineering. Bioact Mater. 2021;6(3):579–88.10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.09.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(52) Bao Y, Ma J, Li N. Synthesis and swelling behaviors of sodium carboxymethyl cellulose-g-poly (AA-co-AM-co-AMPS)/MMT superabsorbent hydrogel. Carbohydr Polym. 2011;84(1):76–82.10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.10.061Search in Google Scholar

(53) Li X, Wu W, Wang J, Duan Y. The swelling behavior and network parameters of guar gum/poly (acrylic acid) semi-interpenetrating polymer network hydrogels. Carbohydr Polym. 2006;66(4):473–9.10.1016/j.carbpol.2006.04.003Search in Google Scholar

(54) Burugapalli K, Bhatia D, Koul V, Choudhary V. Interpenetrating polymer networks based on poly (acrylic acid) and gelatin. I: Swelling and thermal behavior. J Appl Polym Sci. 2001;82(1):217–27.10.1002/app.1841Search in Google Scholar

(55) Van der Harst M, Bull S, Laffont C, Klein W. Gentamicin nephrotoxicity–a comparison of in vitro findings with in vivo experiments in equines. Vet Res Commun. 2005;29:247–61.10.1023/B:VERC.0000047492.05882.bbSearch in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Chitosan nanocomposite film incorporating Nigella sativa oil, Azadirachta indica leaves’ extract, and silver nanoparticles

- Effect of Zr-doped CaCu3Ti3.95Zr0.05O12 ceramic on the microstructure, dielectric properties, and electric field distribution of the LDPE composites

- Effects of dry heating, acetylation, and acid pre-treatments on modification of potato starch with octenyl succinic anhydride (OSA)

- Loading conditions impact on the compression fatigue behavior of filled styrene butadiene rubber

- Characterization and compatibility of bio-based PA56/PET

- Study on the aging of three typical rubber materials under high- and low-temperature cyclic environment

- Numerical simulation and experimental research of electrospun polyacrylonitrile Taylor cone based on multiphysics coupling

- Experimental investigation of properties and aging behavior of pineapple and sisal leaf hybrid fiber-reinforced polymer composites

- Influence of temperature distribution on the foaming quality of foamed polypropylene composites

- Enzyme-catalyzed synthesis of 4-methylcatechol oligomer and preliminary evaluations as stabilizing agent in polypropylene

- Molecular dynamics simulation of the effect of the thermal and mechanical properties of addition liquid silicone rubber modified by carbon nanotubes with different radii

- Incorporation of poly(3-acrylamidopropyl trimethylammonium chloride-co-acrylic acid) branches for good sizing properties and easy desizing from sized cotton warps

- Effect of matrix composition on properties of polyamide 66/polyamide 6I-6T composites with high content of continuous glass fiber for optimizing surface performance

- Preparation and properties of epoxy-modified thermosetting phenolic fiber

- Thermal decomposition reaction kinetics and storage life prediction of polyacrylate pressure-sensitive adhesive

- Effect of different proportions of CNTs/Fe3O4 hybrid filler on the morphological, electrical and electromagnetic interference shielding properties of poly(lactic acid) nanocomposites

- Doping silver nanoparticles into reverse osmosis membranes for antibacterial properties

- Melt-blended PLA/curcumin-cross-linked polyurethane film for enhanced UV-shielding ability

- The affinity of bentonite and WO3 nanoparticles toward epoxy resin polymer for radiation shielding

- Prolonged action fertilizer encapsulated by CMC/humic acid

- Preparation and experimental estimation of radiation shielding properties of novel epoxy reinforced with Sb2O3 and PbO

- Fabrication of polylactic acid nanofibrous yarns for piezoelectric fabrics

- Copper phenyl phosphonate for epoxy resin and cyanate ester copolymer with improved flame retardancy and thermal properties

- Synergistic effect of thermal oxygen and UV aging on natural rubber

- Effect of zinc oxide suspension on the overall filler content of the PLA/ZnO composites and cPLA/ZnO composites

- The role of natural hybrid nanobentonite/nanocellulose in enhancing the water resistance properties of the biodegradable thermoplastic starch

- Performance optimization of geopolymer mortar blending in nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber based on set pair analysis

- Preparation of (La + Nb)-co-doped TiO2 and its polyvinylidene difluoride composites with high dielectric constants

- Effect of matrix composition on the performance of calcium carbonate filled poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composites

- Low-temperature self-healing polyurethane adhesives via dual synergetic crosslinking strategy

- Leucaena leucocephala oil-based poly malate-amide nanocomposite coating material for anticorrosive applications

- Preparation and properties of modified ammonium polyphosphate synergistic with tris(2-hydroxyethyl) isocynurate for flame-retardant LDPE

- Thermal response of double network hydrogels with varied composition

- The effect of coated calcium carbonate using stearic acid on the recovered carbon black masterbatch in low-density polyethylene composites

- Investigation of MXene-modified agar/polyurethane hydrogel elastomeric repair materials with tunable water absorption

- Damping performance analysis of carbon black/lead magnesium niobite/epoxy resin composites

- Molecular dynamics simulations of dihydroxylammonium 5,5′-bistetrazole-1,1′-diolate (TKX-50) and TKX-50-based PBXs with four energetic binders

- Preparation and characterization of sisal fibre reinforced sodium alginate gum composites for non-structural engineering applications

- Study on by-products synthesis of powder coating polyester resin catalyzed by organotin

- Ab initio molecular dynamics of insulating paper: Mechanism of insulating paper cellobiose cracking at transient high temperature

- Effect of different tin neodecanoate and calcium–zinc heat stabilizers on the thermal stability of PVC

- High-strength polyvinyl alcohol-based hydrogel by vermiculite and lignocellulosic nanofibrils for electronic sensing

- Impacts of micro-size PbO on the gamma-ray shielding performance of polyepoxide resin

- Influence of the molecular structure of phenylamine antioxidants on anti-migration and anti-aging behavior of high-performance nitrile rubber composites

- Fiber-reinforced polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel via in situ fiber formation

- Preparation and performance of homogenous braids-reinforced poly (p-phenylene terephthamide) hollow fiber membranes

- Synthesis of cadmium(ii) ion-imprinted composite membrane with a pyridine functional monomer and characterization of its adsorption performance

- Impact of WO3 and BaO nanoparticles on the radiation shielding characteristics of polydimethylsiloxane composites

- Comprehensive study of the radiation shielding feature of polyester polymers impregnated with iron filings

- Preparation and characterization of polymeric cross-linked hydrogel patch for topical delivery of gentamicin

- Mechanical properties of rCB-pigment masterbatch in rLDPE: The effect of processing aids and water absorption test

- Pineapple fruit residue-based nanofibre composites: Preparation and characterizations

- Effect of natural Indocalamus leaf addition on the mechanical properties of epoxy and epoxy-carbon fiber composites

- Utilization of biosilica for energy-saving tire compounds: Enhancing performance and efficiency

- Effect of capillary arrays on the profile of multi-layer micro-capillary films

- A numerical study on thermal bonding with preheating technique for polypropylene microfluidic device

- Development of modified h-BN/UPE resin for insulation varnish applications

- High strength, anti-static, thermal conductive glass fiber/epoxy composites for medical devices: A strategy of modifying fibers with functionalized carbon nanotubes

- Effects of mechanical recycling on the properties of glass fiber–reinforced polyamide 66 composites in automotive components

- Bentonite/hydroxyethylcellulose as eco-dielectrics with potential utilization in energy storage

- Study on wall-slipping mechanism of nano-injection polymer under the constant temperature fields

- Synthesis of low-VOC unsaturated polyester coatings for electrical insulation

- Enhanced apoptotic activity of Pluronic F127 polymer-encapsulated chlorogenic acid nanoparticles through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in liver cancer cells and in vivo toxicity studies in zebrafish

- Preparation and performance of silicone-modified 3D printing photosensitive materials

- A novel fabrication method of slippery lubricant-infused porous surface by thiol-ene click chemistry reaction for anti-fouling and anti-corrosion applications

- Development of polymeric IPN hydrogels by free radical polymerization technique for extended release of letrozole: Characterization and toxicity evaluation

- Tribological characterization of sponge gourd outer skin fiber-reinforced epoxy composite with Tamarindus indica seed filler addition using the Box–Behnken method

- Stereocomplex PLLA–PBAT copolymer and its composites with multi-walled carbon nanotubes for electrostatic dissipative application

- Enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of Krestin–chitosan nanocomplex for cancer medication via activation of the mitochondrial intrinsic pathway

- Variation in tungsten(vi) oxide particle size for enhancing the radiation shielding ability of silicone rubber composites

- Damage accumulation and failure mechanism of glass/epoxy composite laminates subjected to repeated low velocity impacts

- Gamma-ray shielding analysis using the experimental measurements for copper(ii) sulfate-doped polyepoxide resins

- Numerical simulation into influence of airflow channel quantities on melt-blowing airflow field in processing of polymer fiber

- Cellulose acetate oleate-reinforced poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composite materials

- Radiation shielding capability and exposure buildup factor of cerium(iv) oxide-reinforced polyester resins

- Recyclable polytriazole resins with high performance based on Diels-Alder dynamic covalent crosslinking

- Adsorption and recovery of Cr(vi) from wastewater by Chitosan–Urushiol composite nanofiber membrane

- Comprehensive performance evaluation based on electromagnetic shielding properties of the weft-knitted fabrics made by stainless steel/cotton blended yarn

- Review Articles

- Preparation and application of natural protein polymer-based Pickering emulsions

- Wood-derived high-performance cellulose structural materials

- Flammability properties of polymers and polymer composites combined with ionic liquids

- Polymer-based nanocarriers for biomedical and environmental applications

- A review on semi-crystalline polymer bead foams from stirring autoclave: Processing and properties

- Rapid Communication

- Preparation and characterization of magnetic microgels with linear thermosensitivity over a wide temperature range

- Special Issue: Biodegradable and bio-based polymers: Green approaches (Guest Editors: Kumaran Subramanian, A. Wilson Santhosh Kumar, and Venkatajothi Ramarao)

- Synthesis and characterization of proton-conducting membranes based on bacterial cellulose and human nail keratin

- Fatigue behaviour of Kevlar/carbon/basalt fibre-reinforced SiC nanofiller particulate hybrid epoxy composite

- Effect of citric acid on thermal, phase morphological, and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactide)-b-poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(l-lactide)/thermoplastic starch blends

- Dose-dependent cytotoxicity against lung cancer cells via green synthesized ZnFe2O4/cellulose nanocomposites

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Chitosan nanocomposite film incorporating Nigella sativa oil, Azadirachta indica leaves’ extract, and silver nanoparticles

- Effect of Zr-doped CaCu3Ti3.95Zr0.05O12 ceramic on the microstructure, dielectric properties, and electric field distribution of the LDPE composites

- Effects of dry heating, acetylation, and acid pre-treatments on modification of potato starch with octenyl succinic anhydride (OSA)

- Loading conditions impact on the compression fatigue behavior of filled styrene butadiene rubber

- Characterization and compatibility of bio-based PA56/PET

- Study on the aging of three typical rubber materials under high- and low-temperature cyclic environment

- Numerical simulation and experimental research of electrospun polyacrylonitrile Taylor cone based on multiphysics coupling

- Experimental investigation of properties and aging behavior of pineapple and sisal leaf hybrid fiber-reinforced polymer composites

- Influence of temperature distribution on the foaming quality of foamed polypropylene composites

- Enzyme-catalyzed synthesis of 4-methylcatechol oligomer and preliminary evaluations as stabilizing agent in polypropylene

- Molecular dynamics simulation of the effect of the thermal and mechanical properties of addition liquid silicone rubber modified by carbon nanotubes with different radii

- Incorporation of poly(3-acrylamidopropyl trimethylammonium chloride-co-acrylic acid) branches for good sizing properties and easy desizing from sized cotton warps

- Effect of matrix composition on properties of polyamide 66/polyamide 6I-6T composites with high content of continuous glass fiber for optimizing surface performance

- Preparation and properties of epoxy-modified thermosetting phenolic fiber

- Thermal decomposition reaction kinetics and storage life prediction of polyacrylate pressure-sensitive adhesive

- Effect of different proportions of CNTs/Fe3O4 hybrid filler on the morphological, electrical and electromagnetic interference shielding properties of poly(lactic acid) nanocomposites

- Doping silver nanoparticles into reverse osmosis membranes for antibacterial properties

- Melt-blended PLA/curcumin-cross-linked polyurethane film for enhanced UV-shielding ability

- The affinity of bentonite and WO3 nanoparticles toward epoxy resin polymer for radiation shielding

- Prolonged action fertilizer encapsulated by CMC/humic acid

- Preparation and experimental estimation of radiation shielding properties of novel epoxy reinforced with Sb2O3 and PbO

- Fabrication of polylactic acid nanofibrous yarns for piezoelectric fabrics

- Copper phenyl phosphonate for epoxy resin and cyanate ester copolymer with improved flame retardancy and thermal properties

- Synergistic effect of thermal oxygen and UV aging on natural rubber

- Effect of zinc oxide suspension on the overall filler content of the PLA/ZnO composites and cPLA/ZnO composites

- The role of natural hybrid nanobentonite/nanocellulose in enhancing the water resistance properties of the biodegradable thermoplastic starch

- Performance optimization of geopolymer mortar blending in nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber based on set pair analysis

- Preparation of (La + Nb)-co-doped TiO2 and its polyvinylidene difluoride composites with high dielectric constants

- Effect of matrix composition on the performance of calcium carbonate filled poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composites

- Low-temperature self-healing polyurethane adhesives via dual synergetic crosslinking strategy

- Leucaena leucocephala oil-based poly malate-amide nanocomposite coating material for anticorrosive applications

- Preparation and properties of modified ammonium polyphosphate synergistic with tris(2-hydroxyethyl) isocynurate for flame-retardant LDPE

- Thermal response of double network hydrogels with varied composition

- The effect of coated calcium carbonate using stearic acid on the recovered carbon black masterbatch in low-density polyethylene composites

- Investigation of MXene-modified agar/polyurethane hydrogel elastomeric repair materials with tunable water absorption

- Damping performance analysis of carbon black/lead magnesium niobite/epoxy resin composites

- Molecular dynamics simulations of dihydroxylammonium 5,5′-bistetrazole-1,1′-diolate (TKX-50) and TKX-50-based PBXs with four energetic binders

- Preparation and characterization of sisal fibre reinforced sodium alginate gum composites for non-structural engineering applications

- Study on by-products synthesis of powder coating polyester resin catalyzed by organotin

- Ab initio molecular dynamics of insulating paper: Mechanism of insulating paper cellobiose cracking at transient high temperature

- Effect of different tin neodecanoate and calcium–zinc heat stabilizers on the thermal stability of PVC

- High-strength polyvinyl alcohol-based hydrogel by vermiculite and lignocellulosic nanofibrils for electronic sensing

- Impacts of micro-size PbO on the gamma-ray shielding performance of polyepoxide resin

- Influence of the molecular structure of phenylamine antioxidants on anti-migration and anti-aging behavior of high-performance nitrile rubber composites

- Fiber-reinforced polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel via in situ fiber formation

- Preparation and performance of homogenous braids-reinforced poly (p-phenylene terephthamide) hollow fiber membranes

- Synthesis of cadmium(ii) ion-imprinted composite membrane with a pyridine functional monomer and characterization of its adsorption performance

- Impact of WO3 and BaO nanoparticles on the radiation shielding characteristics of polydimethylsiloxane composites

- Comprehensive study of the radiation shielding feature of polyester polymers impregnated with iron filings

- Preparation and characterization of polymeric cross-linked hydrogel patch for topical delivery of gentamicin

- Mechanical properties of rCB-pigment masterbatch in rLDPE: The effect of processing aids and water absorption test

- Pineapple fruit residue-based nanofibre composites: Preparation and characterizations

- Effect of natural Indocalamus leaf addition on the mechanical properties of epoxy and epoxy-carbon fiber composites

- Utilization of biosilica for energy-saving tire compounds: Enhancing performance and efficiency

- Effect of capillary arrays on the profile of multi-layer micro-capillary films

- A numerical study on thermal bonding with preheating technique for polypropylene microfluidic device

- Development of modified h-BN/UPE resin for insulation varnish applications

- High strength, anti-static, thermal conductive glass fiber/epoxy composites for medical devices: A strategy of modifying fibers with functionalized carbon nanotubes

- Effects of mechanical recycling on the properties of glass fiber–reinforced polyamide 66 composites in automotive components

- Bentonite/hydroxyethylcellulose as eco-dielectrics with potential utilization in energy storage

- Study on wall-slipping mechanism of nano-injection polymer under the constant temperature fields

- Synthesis of low-VOC unsaturated polyester coatings for electrical insulation

- Enhanced apoptotic activity of Pluronic F127 polymer-encapsulated chlorogenic acid nanoparticles through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in liver cancer cells and in vivo toxicity studies in zebrafish

- Preparation and performance of silicone-modified 3D printing photosensitive materials

- A novel fabrication method of slippery lubricant-infused porous surface by thiol-ene click chemistry reaction for anti-fouling and anti-corrosion applications

- Development of polymeric IPN hydrogels by free radical polymerization technique for extended release of letrozole: Characterization and toxicity evaluation

- Tribological characterization of sponge gourd outer skin fiber-reinforced epoxy composite with Tamarindus indica seed filler addition using the Box–Behnken method

- Stereocomplex PLLA–PBAT copolymer and its composites with multi-walled carbon nanotubes for electrostatic dissipative application

- Enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of Krestin–chitosan nanocomplex for cancer medication via activation of the mitochondrial intrinsic pathway

- Variation in tungsten(vi) oxide particle size for enhancing the radiation shielding ability of silicone rubber composites

- Damage accumulation and failure mechanism of glass/epoxy composite laminates subjected to repeated low velocity impacts

- Gamma-ray shielding analysis using the experimental measurements for copper(ii) sulfate-doped polyepoxide resins

- Numerical simulation into influence of airflow channel quantities on melt-blowing airflow field in processing of polymer fiber

- Cellulose acetate oleate-reinforced poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composite materials

- Radiation shielding capability and exposure buildup factor of cerium(iv) oxide-reinforced polyester resins

- Recyclable polytriazole resins with high performance based on Diels-Alder dynamic covalent crosslinking

- Adsorption and recovery of Cr(vi) from wastewater by Chitosan–Urushiol composite nanofiber membrane

- Comprehensive performance evaluation based on electromagnetic shielding properties of the weft-knitted fabrics made by stainless steel/cotton blended yarn

- Review Articles

- Preparation and application of natural protein polymer-based Pickering emulsions

- Wood-derived high-performance cellulose structural materials

- Flammability properties of polymers and polymer composites combined with ionic liquids

- Polymer-based nanocarriers for biomedical and environmental applications

- A review on semi-crystalline polymer bead foams from stirring autoclave: Processing and properties

- Rapid Communication

- Preparation and characterization of magnetic microgels with linear thermosensitivity over a wide temperature range

- Special Issue: Biodegradable and bio-based polymers: Green approaches (Guest Editors: Kumaran Subramanian, A. Wilson Santhosh Kumar, and Venkatajothi Ramarao)

- Synthesis and characterization of proton-conducting membranes based on bacterial cellulose and human nail keratin

- Fatigue behaviour of Kevlar/carbon/basalt fibre-reinforced SiC nanofiller particulate hybrid epoxy composite

- Effect of citric acid on thermal, phase morphological, and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactide)-b-poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(l-lactide)/thermoplastic starch blends

- Dose-dependent cytotoxicity against lung cancer cells via green synthesized ZnFe2O4/cellulose nanocomposites