Abstract

The use of natural polysaccharides in stretchable hydrogels has attracted more and more attention. However, pure polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) hydrogel has poor mechanical properties and low sensitivity in strain sensors. Composite hydrogels with high tensile properties (the storage modulus of 6,397.8 Pa and the loss modulus of 3,283.9 Pa) and high electrical conductivity (1.57 S·m−1) were prepared using a simple method. The Fe-vermiculite and lignocellulosic nanofibril-based hydrogels were applied as reliable and stable strain sensors that are responsive to environmental stimuli. The prepared hydrogels exhibited excellent ionic conductivity, which satisfied the needs of wrist flexion activity monitoring. The results showed that the PVA/LF0.4 hydrogel has a natural formulation, high mechanical strength, and electrical conductivity, which has great potential for application in artificial electronics.

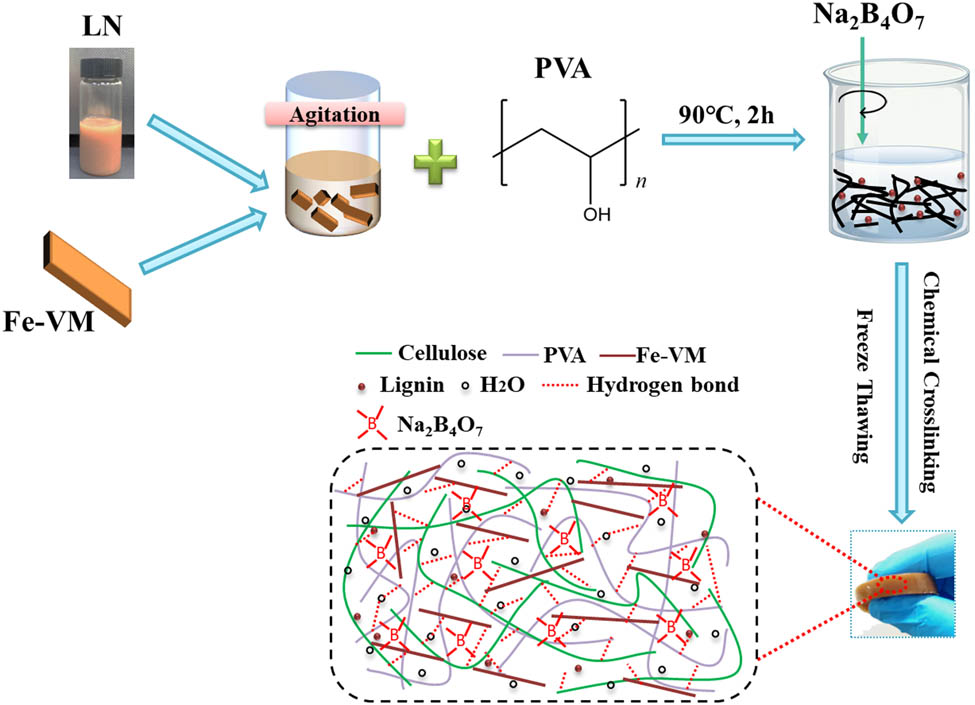

Graphical abstract

Schematic illustration of the fabrication of the PVA/LF0.4 hydrogel, which is then used as conductive hydrogel in electron skin sensors due to excellently tensile (596.7%) and highly conductive (1.57 S‧m−1) properties.

1 Introduction

Electronic hydrogels have attracted more and more attention because of their advantages in bioengineering, energy transfer, and other fields (1). In particular, electronic hydrogels need to possess electrical conductivity and mechanical capacity to be suitable for long-term biocompatibility of human skin in the biological field (2). For specific applications, many factors need to be explored; for instance, the electrical conductivity of the material at different temperatures and its biocompatibility greatly limit the application scope of such material (3). In recent years, the preparation of the hydrogel materials with liquid-like transport and excellent mechanical performances has generated more interest in the applicability of wearable electronic devices. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) can be used safely for the body without any side effect and low production costs, which is widely applied in the preparation of electronic hydrogels. However, pure PVA hydrogels have certain limitations due to poor mechanical properties and electrical conductivity. PVA hydrogels with polysaccharides as well as conductive materials can effectively increase the application area of PVA (4,5).

The addition of cellulose nanocrystal (CNC) and cellulose nanofibril (CNF) can improve the mechanical properties of hydrogels due to their large surface area and high aspect ratios. The enhanced influences of nanocellulose (CNC and CNF) on the mechanical strength of PVA hydrogels have been explored in some studies (6,7). Compared to pure PVA hydrogels, the hybrid hydrogels showed higher mechanical strength, storage modulus (G′), and loss modulus (G″). Incorporating cross-linking agents such as borax is an effective method to form network structures, which improve hydrogels with self-healing ability and mechanical properties (8). However, nanocellulose is produced from bleached pulp, but the preparation of bleached pulp consumes a large amount of chemical reagents, which has a powerful impact on our environment. We discover that lignocellulosic nanofibrils (LNs) greatly improve the mechanical strength of PVA hydrogels compared to pure nanocellulose. Moreover, LN can be prepared directly from the unbleached pulp through low-cost and eco-friendly pretreatments. Therefore, LN can be used as an ideal filling material (9).

Incorporation of clay (bentonite, hydroxide, and rectorite) forming composite hydrogel polymer electrolytes is a promising method for conductive systems with structural or functional superiority over conventional materials (10,11,12). Vermiculite (VM) is an aluminosilicate clay with a layered structure and has structural property comparable to bentonite. Due to the existence of exchangeable materials in the interlayer region, VM can undergo ion-exchange reactions with cations such as metals to obtain layered silicates with electrical conductivity. Moreover, the increase in the amorphous zone and the stripped state of the clay both improve the conduction of solid electrolyte ions. In addition, electronegative silicates with high dielectric constants facilitate the dissolution of more electrolyte salts, which represents the release of more free ions, improving electrical conductivity (13,14).

Based on the previous discussion, we hope to construct a robust bonding network inside the PVA hydrogels, which improves the electrical conductivity without reducing the mechanical strength. This work investigates whether the incorporation of VM and LN can improve the mechanical strength and conductivity of PVA hydrogels. The hybrid hydrogels are characterized by the related instruments to study the influence of fillers on the mechanical strength and conductivity of the system. Due to numerous advantages of PVA/LN/VM hydrogels, such as simplicity and non-toxic of the preparation process, they are a candidate for conductive devices.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Material

PVA (M W = 125,000 g‧mol−1, 99% hydrolyzed) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. Mg-(VM), borax (Na2B4O7·10H2O), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), and ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O) were purchased from Macklin, China. LNs were prepared from unbleached dry lap eucalyptus kraft pulp.

2.2 Preparation of LN and Fe-VM

About 10 g of unbleached pulp (oven dry) was hydrolyzed in oxalic acid solution (60 wt%) at 100°C for 150 min. When the reaction was completed, the solid fraction was washed with deionized water to remove small molecular impurities. The LN was prepared from the solid fraction using a high-pressure homogenizer (UH-20, China) at 500 bar dispersed three times.

FeCl3·6H2O (1 mol·L−1) was added to VM at a solid–liquid ratio of 1:50, and the reaction was performed in a water bath at 50°C for 5 days. The resulting solid was isolated, washed with deionized water until neutral, and named as Fe-VM (15).

2.3 Preparation of composite hydrogels

The composite hydrogels with LN or Fe-VM were fabricated by a one-pot method. LN or Fe-VM suspension liquid was added into a 50 mL beaker with stirring at 25℃ for 1 h. PVA was slowly added to the LN or VM suspension. The final loading of PVA in the LN (0.5 wt%) or VM (0.5 wt%) suspension was 4 wt%, and the mixed suspension was continuously stirred at 90°C for 2 h until complete dissolution. Then, borax (0.4 wt%) was added into the aforementioned mixed suspension and stirred at 0℃ until dissolved. The obtained solutions were poured into molds and stored overnight in a freezer at −20°C to obtain frozen samples. Only one freeze–thaw cycle was performed. Pure PVA hydrogel containing LN (0.5 wt%) was named as PVA/LN. The PVA/LN hydrogel with Fe-VM (0.5 wt%) was labeled as PVA/LF. The hydrogels were denoted as PVA/LF0.4 corresponding to LN (0.5 wt%), VM (0.5 wt%), and borax (0.4 wt%).

2.4 Characterization of composite hydrogels

Atomic force microscopy (AFM; Dimension Edge, Bruker, Germany) was used to visualize the morphological characteristics of LN. The internal structure of composite hydrogels was studied by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Quanta 200, FEI, USA) with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) to explore the distribution of elements (Al, Fe, and Mg) over the prepared samples. The hydrogel samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and then freeze-dried in a freeze-drying machine. The infrared spectrometer spectra of the freeze-dried samples were obtained using a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR, PerkinElmer, UK) in the wave number range of 4,000–400 cm−1. The N2 adsorption behaviors were performed using an automated specific surface area and porosity analyzer (Autosorb-iQ-2MP, USA). The structural property of freeze-dried samples was determined by measuring the amount of N2 adsorbed and desorbed. The obtained adsorption isotherms were used to calculate the specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution of the samples (16). The hydrogel samples were taken out from the molds and weighed after removing excess water with papers. The water content of samples (W) was determined by the following equation:

where m 0 and m 1 are the initial weight of the sample and the weight of the sample after drying at 105℃ for 24 h, respectively.

The samples were subjected to a strain sweep and a frequency sweep test on the RS6000 (HAAKE, German) rheometer equipped with a Platte P20 TiL and cone plate P20 TiL at 25℃. Compression measurements were taken using a universal tester (AG-X, Japan). A preload force of 0.2 N was used to stabilize the cylindrical hydrogels owing to the slightly homogeneous top surface of the hydrogel. Each specimen was compressed vertically at 0.1 mm·s−1 in air at 25°C. Compressive stress and strain absorption rates were calculated by measuring force and sample displacement. Before the tensile test (AG-X, Japan), the sample size was 20 mm × 5 mm × 5 mm. The hydrogel from both ends was stretched to break, and the initial length and final length of the hydrogel were recorded. Each sample was stretched three times, and the mean value was reported. A circuit consisting of a hydrogel, a 3 V battery, and LED bulbs was used to determine the conductivity of hydrogel samples. Moreover, the impedance of hydrogel samples was detected using an electrochemical workstation, which is described in the following equation (17):

where σ and d are the conductivity and the thickness of the sample, respectively, and A and R are the cross-sectional area and the impedance of the sample, respectively.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Morphological characteristics of LN

The length-to-diameter ratio of LN played a crucial role in enhancing the strength of hydrogels, and here, we further understand the structure of LN by AFM detection. Figure 1 displays the AFM images and the relative height distribution. Various fiber sizes and small lignin particles could be clearly seen in the LN sample from Figure 1a. The deposition of lignin on cellulose fibers after pretreatment with solid acid has been reported (18). It is possible that oxalic acid pretreatment broke the carbohydrate–lignin bond, which forced the hydrophobic lignin in the solvent to condense into lignin particles that deposited on the cellulose surface (19). Figure 1b shows that the average height distribution of cellulose fibers was approximately 23 nm. Compared with mechanical treatment, negative carboxyl groups with oxalic acid could produce repulsive forces on the cellulose surface, which accelerated cellulose dispersion (20). However, the presence of lignin also hindered cellulose dispersion, which was unable to obtain finer and more uniform nanofibrils, demonstrating that delignification accelerated nanofibrillation (21). However, during the production of LN, lignin reduced the depolymerization of cellulose, resulting in LN with a high length-to-diameter ratio, which promoted the entanglement of the PVA hydrogel network and facilitated the formation of hydrogels with high mechanical strength (4).

(a) AFM image of the LN (scale bar = 1 μm); (b) height distribution measured from AFM image.

3.2 Structural characterization of the hydrogels

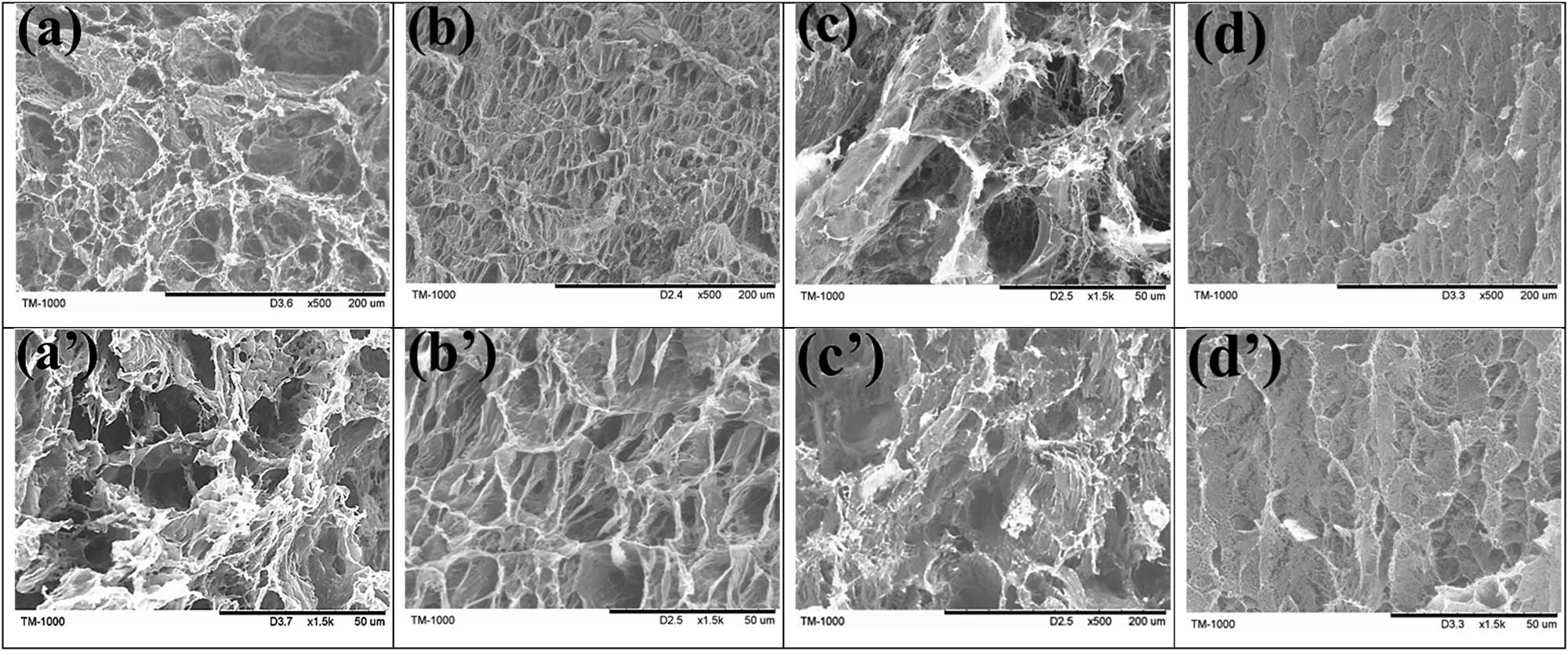

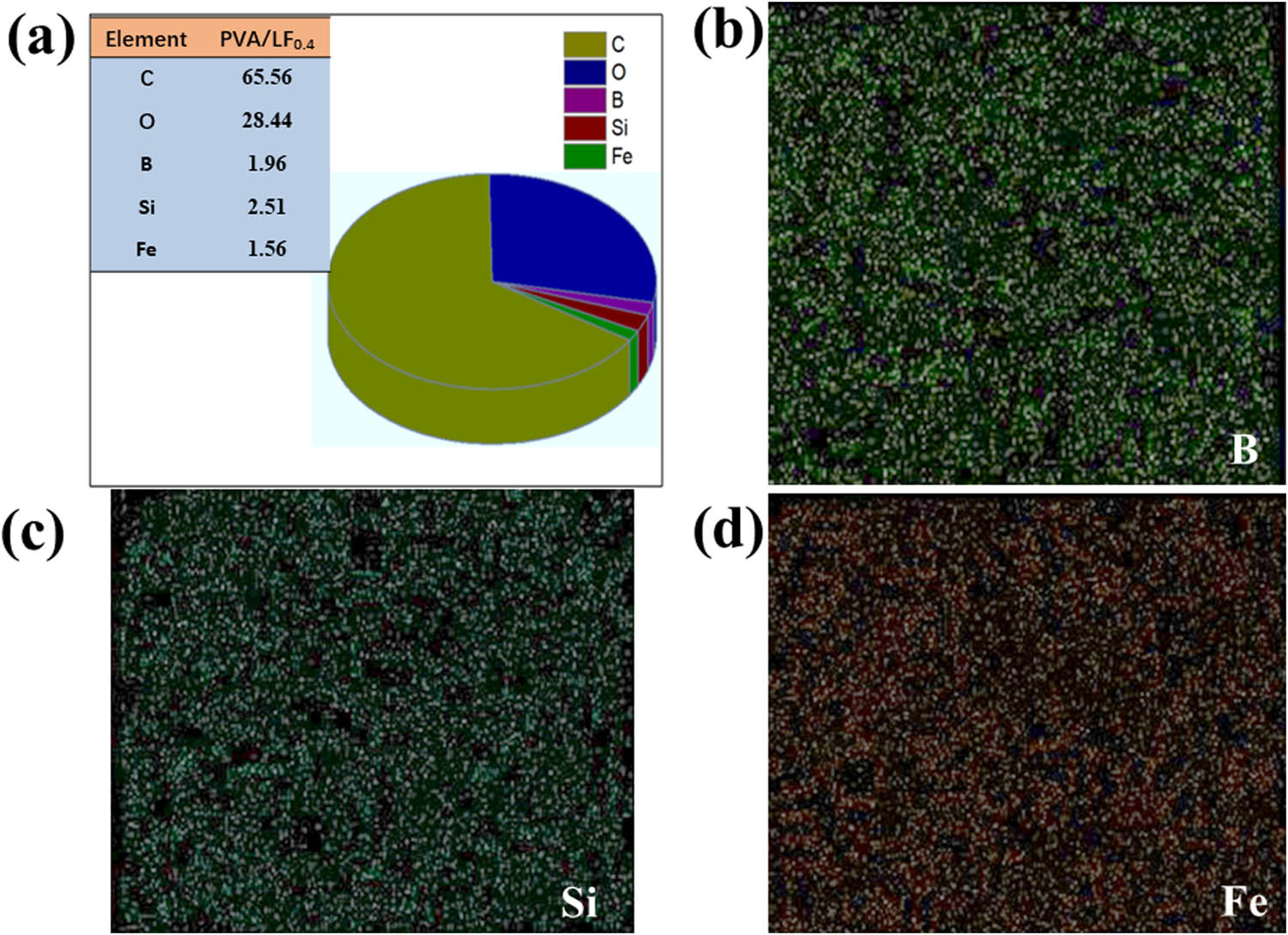

To better understand the structural properties of different hydrogels, SEM images of pure PVA, PVA/LN, PVA/LF, and PVA/LF0.4 are displayed in Figure 2. It was observed that by incorporating LNs into the pure PVA hydrogel, the porous network structures were more uniform. LNs with high aspect ratio had a positive influence on hydrogel structure (22). However, when Fe-VM was added to the PVA/LN hydrogels, it was obvious that the PVA/LF hydrogel structure collapsed and the porous structures were not uniform, suggesting that the Fe-VM particles were less compatible with PVA/LN. When borax was added to the PVA/LF hydrogels, dense reticular structure appearance was observed and collapse was not visible, which would be beneficial to increase the mechanical strength (23). Moreover, EDS determined the distribution of each element in Figure 3. The uniform distribution of elements carbon (C), oxygen (O), boron (B), iron (Fe), and silicon (Si) in the PVA/LF0.4 hydrogels was found, suggesting that VM intercalation compounds with iron instead of magnesium between the layers were synthesized by an ion-exchange process (15). In addition, it could be clearly seen in Figure 3c that boric acid was also uniformly distributed in the hydrogel, indicating a more adequate cross-linking.

SEM images of the interior structure of pure PVA hydrogel (a,a′), PVA/LN hydrogel (b,b′), PVA/LF hydrogel (c,c′), and PVA/LF0.4 hydrogel (d,d′), respectively. Scale bar = 200 μm (a–d) and 50 μm (a′–d′).

The elemental composition of PVA/LF0.4 hydrogel was analyzed by EDS (a); The mass contents of B (b), Si (c), and Fe (d) in percentages.

To further understand the internal porous structure of all hydrogels, the pore diameter, and specific surface area were determined by the amount of N2 adsorbed and desorbed. It could be found that compared with PVA/LN, PVA/LF, and PVA/LF0.4, pure PVA had a higher surface area (136.3 m2·g−1) and pore volume (0.14 cm3·g−1). Due to the disordered dispersion of LN, Fe-VM and borax in PVA, the pore structure of PVA was reduced. However, the low pore volume and surface area increased the electron conduction capacity (24). Details of the pore structure data are shown in Table 1.

Surface area, pore diameter, and pore volume of all samples

| Sample | Surface area (m2·g−1) | Pore diameter (nm) | Pore volume (cm3·g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PVA | 136.29 | 2.45 | 0.14 |

| PVA/LN | 95.95 | 2.04 | 0.10 |

| PVA/LF | 67.25 | 3.23 | 0.08 |

| PVA/LF0.4 | 35.14 | 2.17 | 0.04 |

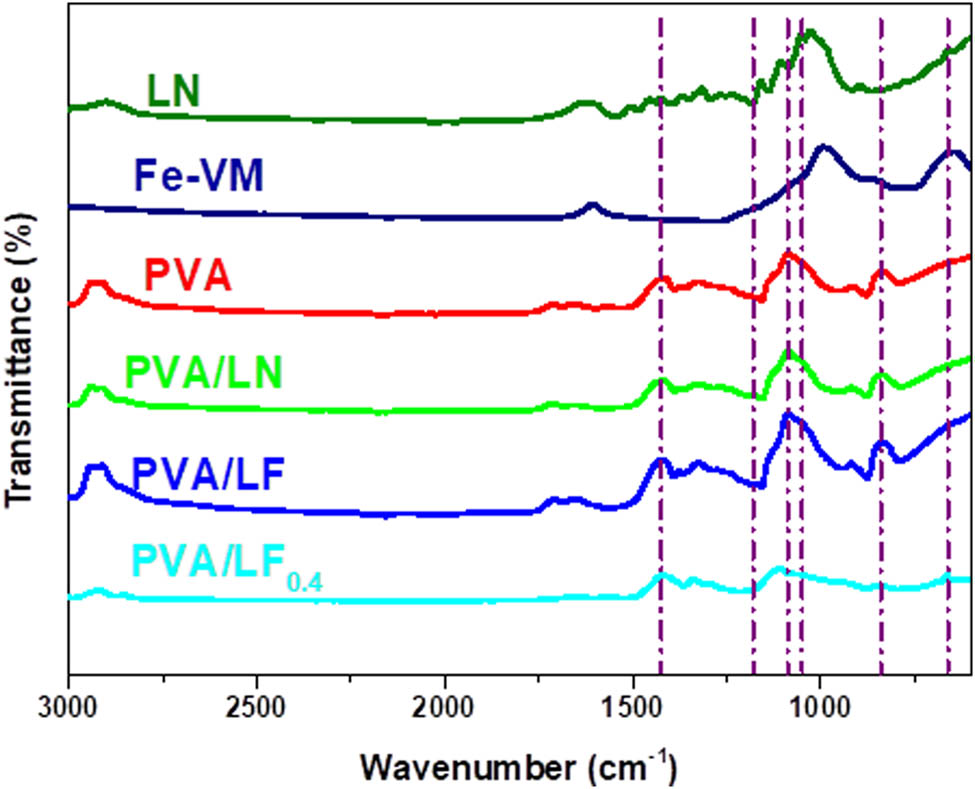

The absorption peaks of PVA at 840 and 1,080 cm−1 corresponded to the stretching of C−O and rocking of −CH, respectively, which was a typical PVA characteristic peak and was reflected in the PVA/LN, PVA/LF, and PVA/LF0.4 hydrogels (25). Figure 4 shows that the characteristic peaks at 1,052 and 1,584 cm−1 associated with the vibration of C–OH in cellulose and stretching of aromatic skeleton in lignin were found in PVA/LN, PVA/LF, and PVA/LF0.4 (or LN) hydrogels. The peak at 667 cm−1 corresponded to the bending vibrational peak of the silicon hydroxyl group in Fe-VM, PVA/LF, and PVA/LF0.4 hydrogels. In addition, the peak intensity of the composite PVA hydrogels decreased at 1,088 and 667 cm−1, indicating that the addition of borax changed the crystallization process of PVA. This result proved the interaction of the hydroxyl group of the PVA matrix with borax (26).

FTIR spectra of all samples.

3.3 Mechanical behavior of hydrogels

The water retention rate was very important in the performance of hydrogel. As shown in Table 2, incorporating LN, Fe-VM, and borax decreased the moisture content of the hydrogels. Nevertheless, the hydrogels maintained approximately 93.5% of the water content because of the interaction between the hydrogen bonds as well as the ester bonds. Moreover, PVA/LN, PVA/LF, and PVA/LF0.4 were opaque due to the presence of LN and Fe-VM.

Moisture content and rheological properties of the composite hydrogels

| Samples | Moisture content (wt%) | Maximum G′ at 1 Hz (Pa) | Maximum G″ at 1 Hz (Pa) | Maximum G′ at 1 Pa (Pa) | Maximum G″ at 1 Pa (Pa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVA | 96.2 | 560.0 | 213.1 | 629.2 | 59.9 |

| PVA/LN | 95.6 | 1,506.3 | 664.3 | 944.6 | 128.1 |

| PVA/LF | 94.4 | 687.1 | 259.8 | 885.0 | 101.3 |

| PVA/LF0.4 | 93.6 | 6,397.8 | 3,283.9 | 12,116.6 | 4,145.4 |

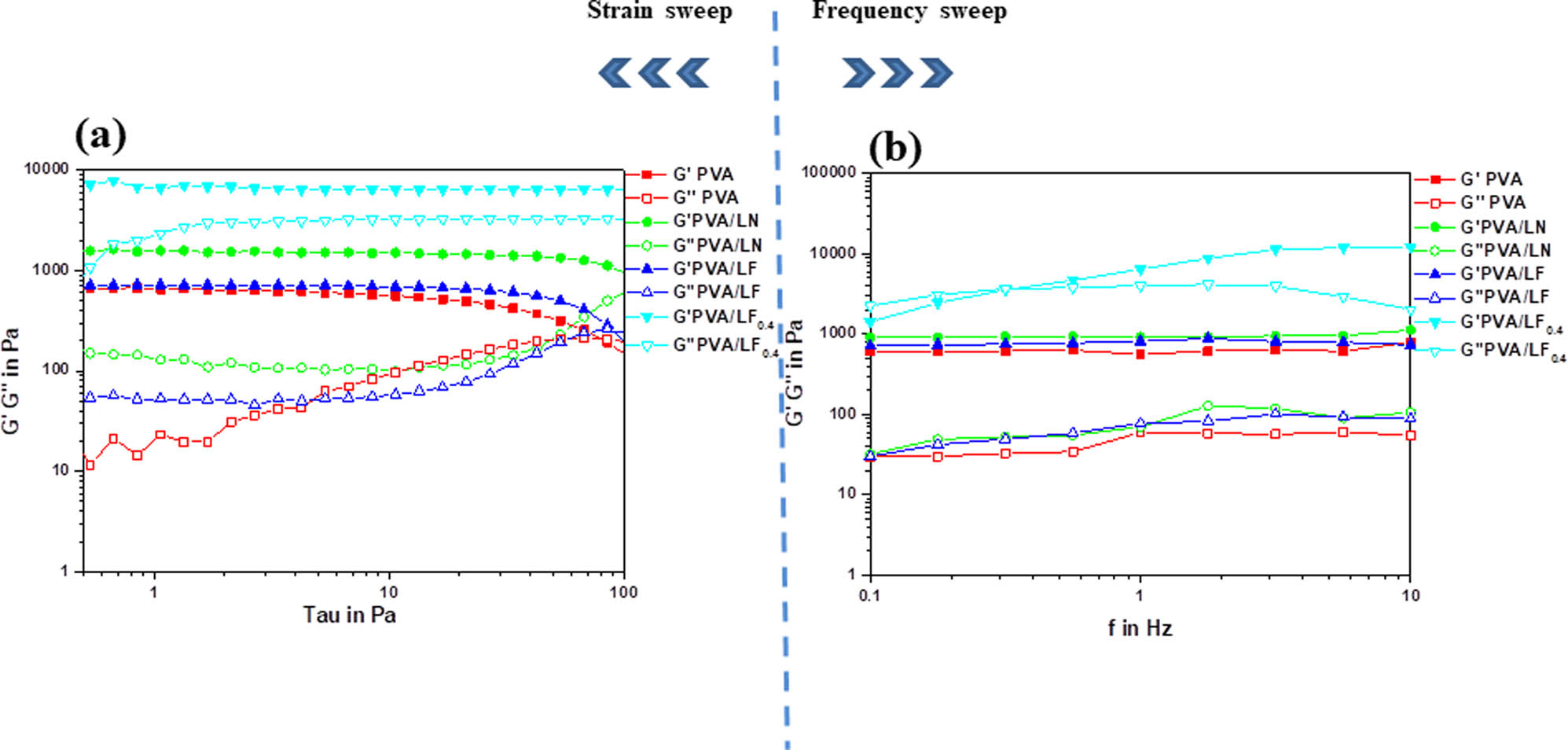

To explore the effect of LN, VM, and borax on the viscoelastic behaviors of the hydrogels, the stress sweep and frequency sweep of the samples are shown in Figure 5. The storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) correspond to the stiffness and viscosity, respectively. The G′ of samples was higher than the G″ of samples, reflecting that all hydrogels exhibited typical hydrogel characteristics. The location and length of the linear viscoelastic region demonstrated that the hydrogels were resistant to flow. The G′ of pure PVA, PVA/LN, PVA/LF, and PVA/LF0.4 hydrogels reached 560.0, 1,506.3, 687.1, and 6,397.8 Pa, respectively, as shown in Figure 5a. The G′ of PVA/LN hydrogels was approximately 2.5 times greater than that of pure PVA hydrogels, indicating that the cross-linking point between PVA and LN increased with the incorporation of lignocellulose, which formed stronger mechanical properties (27). However, when Fe-VM was added to PVA/LN hydrogels, the mechanical properties of PVA/LF hydrogels were well lower than those of PVA/LN hydrogels. The phenomenon indicated that inorganic Fe-VM particles destroyed the hydrogen bonding force between PVA and LN, which resulted in the degradation of mechanical properties. Although the electrical conductivity of the PVA/LF hydrogels was increased, the mechanical strength of the PVA/LF hydrogels was significantly reduced. Incorporating borax into PVA/LF hydrogels could improve rheological and mechanical properties. Compared with hydrogels reinforced by LN, the G′ of PVA/LF0.4 hydrogels increased by about four times, because borax and PVA/LF suspension could form chemical cross-linking upon mixing. Meanwhile, Figure 5 shows that the G″ of the PVA/LF0.4 hydrogel was higher than that of other hydrogels, indicating that it had better flexibility, which could greatly increase its potential applications in soft electrochemical devices (28,29).

Stress sweep (a) and frequency sweep (b) of all hydrogels.

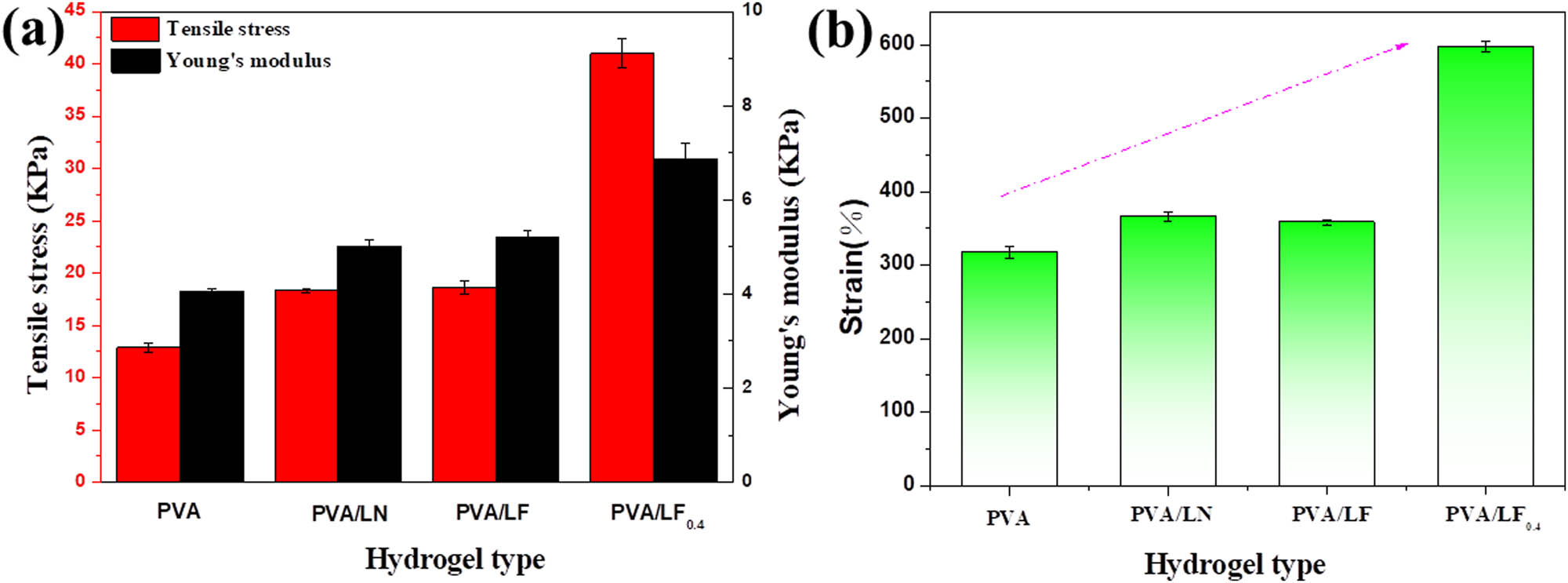

Hydrogels usually suffer from poor tensile properties, limiting their practical application in many aspects. The incorporation of LN, Fe-VM, and borax could significantly enhance the mechanical properties of PVA/LF0.4 hydrogels (Figure 6). The mechanical properties of the PVA hydrogel were unsatisfied with tensile stress of <13 kPa. However, the PVA/LF0.4 hydrogel displayed a tensile stress of 41.0 kPa and a fracture strain of 596.7%, which may be related to the fact that borax generated more coordination bonds during the formation of the dual network. To be specific, when the LN, Fe-VM, and borax were gradually added to PVA, the Young’s modulus increased from 4.1 to 6.9 kPa, which was still quite large for PVA hydrogel. Therefore, the loading of LN, Fe-VM, and borax influenced the elasticity and toughness of hydrogels.

(a) Young’s modulus and tensile stress of all samples; (b) tensile properties of different hydrogel samples.

3.4 Compression stress–strain performance of the hydrogels

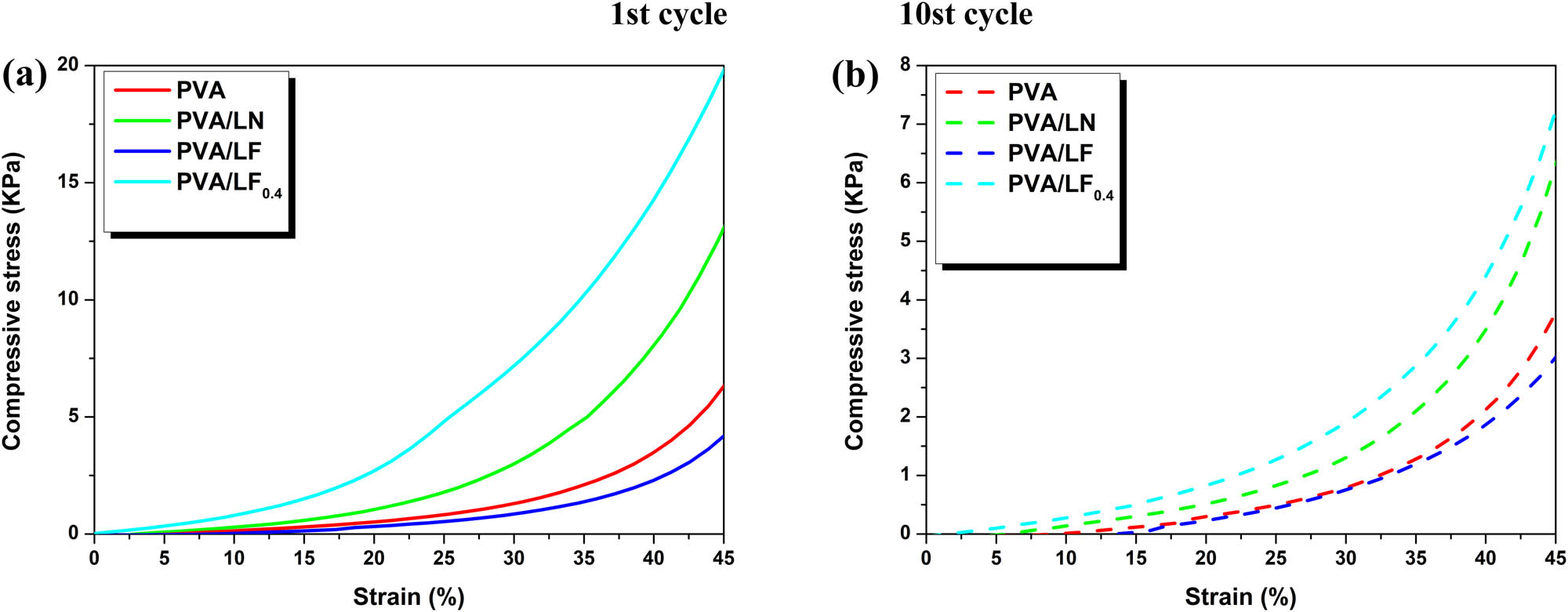

The cyclic compressive behavior of the samples was extremely characteristic in many material fields. It can be obviously seen that the compressive stress and strain of all samples were exponentially related without significant plateau (Figure 7). It was found in Figure 7a that the addition of LN led to a significant increase in the compressive stress in the first cycle. Similar performance in compression strength was also reported by Bian et al. using nanocellulose and lignin-containing CNF (4). However, compared with the PVA/LN and PVA, we found that the introduction of Fe-VM would result in a further decrease in maximum compression stress (4.3 kPa) for PVA/LF. As Fe-VM was added to the hydrogel in the way of physical filling, the content of hydroxyl groups in the hydrogel was reduced, resulting in the decrease in hydrogel strength. Although the introduction of Fe-VM increased the conductivity of hydrogels, it also reduced the strength of hydrogels. In order to solve this problem, the adding of cross-linking agent led to a significant improvement in maximum compression stress from 4.3 to 19.6 kPa. Furthermore, its excellent conductivity was well retained in the PVA/LF0.4.

Cyclic compression stress−strain curves ((a) 1st cycle and (b) 10 st cycle) of the hydrogel samples with a maximum strain of 45%.

The maximum stress in the hydrogels decreased from the second to tenth cycles in Figure 7b, most likely due to the disruption of hydrogen bonds in the PVA. These interesting findings further confirmed the hydrogen bonding interactions between PVA and LN to ensure excellent mechanical properties. However, the addition of boric acid and Fe-VM did not change the continuous decrease after cycling, which may be due to the fact that the formation of hydrogels depends mainly on hydrogen bonding interactions.

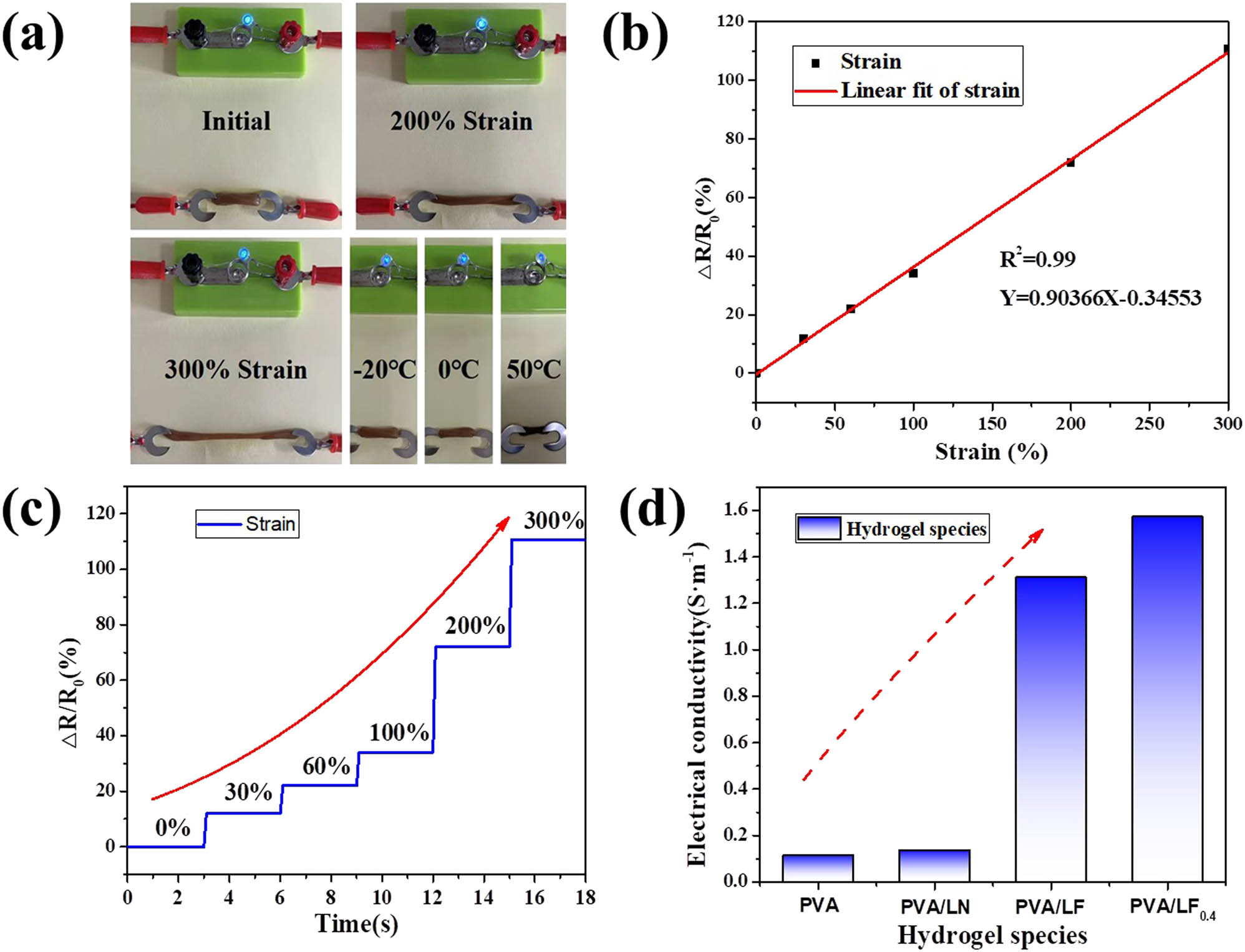

3.5 Electrical sensing analysis

The PVA/LF0.4 could be integrated into an external circuit of a 3 V power supply and an LED, and the change in strain could be directly observed through the change in LED brightness, which could reveal the relative resistance change of the flexible sensor. Figure 8 shows the conductivity of the prepared hydrogels and the influence of different temperature and shape variables on the conductivity of the PVA/LF0.4 hydrogel. As shown in Figure 8a, the brightness of the LED lamp also dimmed with the stretching of the hydrogel. Under the external environment at −20℃, 0℃, and 50℃, the LED lamp could still emit light and maintain good electrical conductivity. It could be further seen from Figure 8b that the stretching of the hydrogel led to the increase of resistance. In the process of stretching, when the strain was from 0% to 300%, the relative resistance changed linearly (R 2 = 0.99), meaning that PVA/LF0.4 hydrogel had excellent linearity and sensitivity. Figure 8c shows that the resistance had no significant drift and hysteresis with the strain increased, suggesting that the prepared hydrogel had good conductivity stability. Figure 8d displays that the addition of Fe-VM in hydrogels showed a significant improvement in electrical conductivity, which basically met the needs of wearable electronics. Notably, the addition of borax did not significantly improve the conductivity of the hydrogel, but the cross-linking effect of borax could further improve the high adhesion of the PVA/LF0.4 hydrogel (30).

(a) Luminance variation of LED with different sample elongations and different temperatures; (b and c) the resistance variation for a stepwise tensile deformation from 0% to 300% strains; and (d) conductivity of all hydrogels.

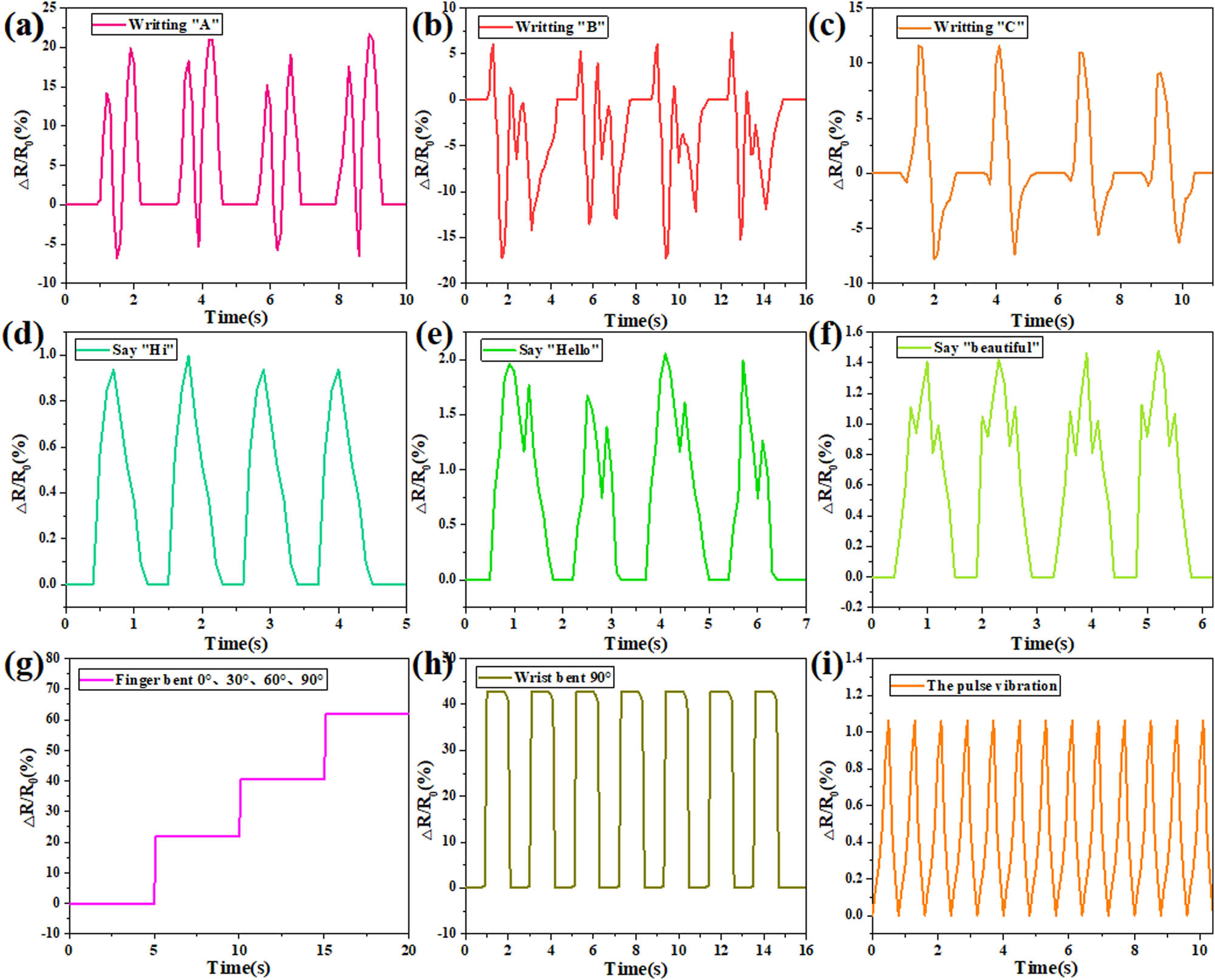

To demonstrate the application of the PVA/LF0.4 hydrogel strain sensor as a wearable device, it was used to detect different bending movements of the joints to get real-time resistance changes. Figure 9a–c shows that the PVA/LF0.4 was attached to the knuckle of the hand and the relative resistance change curve was detected by writing “A, B, and C.” It could be seen that the change in relative resistance showed a certain regularity and repeatability with the change in the degree of finger flexion. The PVA/LF0.4 hydrogel was attached to Adam’s apple, and the words “Hi, hello, beautiful” were pronounced, respectively. It could be seen from Figure 9d–f that the monosyllabic word “Hi” corresponded to one peak, the disyllabic word “Hello” corresponded to two peaks, and the trisyllabic word “Beautiful” had three peaks, indicating the sensitivity of conductance sensing, and the weak Adam’s apple vibration could be converted into electrical signal transmission. The PVA/LF0.4 hydrogel was attached to the index finger, and the index finger was bent at 0°, 30°, 60°, and 90°, respectively, as shown in Figure 9g. The resistance tended to increase with the bending angle of the fingers. When the index finger was bent at different angles, the resistance of the hydrogel sample maintained relatively stable. Figure 9h shows that the resistance of hydrogel sample increased as the wrist was bent. The resistance immediately returned to its original state as the wrist was straightened. When the wrist was maintained at 0° or 90°, the sensing curve hardly changed, indicating the stability of the conductance sensing. The PVA/LF0.4 hydrogel was attached to the pulse to monitor the frequency of the pulse heartbeat, as shown in Figure 9i. It could be seen that 13 peaks appeared in the sensing curve within 10 s, indicating the pulse beat 13 times within 10 s, which was in line with the frequency of the human pulse heartbeat. This also indicated the accuracy of conductance sensing. PVA/LF0.4 hydrogel strain sensor outputs through the relative resistance variation of the hydrogel during compression or stretching. For example, the slipping of the PVA/LF0.4 led to the longer pathway for electron transport, and the reduced pore size of the hydrogel network caused the decreased ion migration under stretching. The aforementioned results showed that the response behavior of the strain sensor was stable, fast, sensitive, and accurate, and this sensor could be applied as a wearable sensor for behavior detection monitoring (31,32).

Electrical sensing analysis of the PVA/LF0.4 hydrogel: (a–c) gesture “A, B, C” sensor image, (d–f) Adam’s apple pronunciation “Hi, Hello, Beautiful” sensor image, (g) finger bending sensor image, (h) wrist bending sensor image, and (i) pulse sensor image.

4 Conclusions

In this study, high-strength PVA-based hydrogels were prepared by a simple method. By incorporating LN, Fe-VM, and cross-linking agent into the PVA hydrogel, compared with pure PVA hydrogel, the composite hydrogel had higher mechanical properties and electrical conductivity. The existence of modified VM fillers provided alternative pathways for electron conduction, promoting higher electron conduction. However, the addition of Fe-VM reduced the strength of the hydrogel. Hence, the introduction of a cross-linking agent (borax) could significantly improve mechanical strength. This study was of great significance to enhance the use of inorganic VM and LNs in the field of artificial electronics.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31800495), Natural Science Basic Research Project of Changzhou (CJ20220053), and Jiangsu Province Graduate Practice Innovation Program Project (XSJCX22_72).

-

Author contributions: Yaxin Hu: conceptualization, methodology, validation, data curation, visualization, writing – review and editing, writing – original draft; Jing Luo, Shipeng Luo, Tong Fei, and Mingyao Song: validation, data curation, visualization, writing – review and editing, supervision; Hengfei Qin: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, validation, writing – review and editing, funding acquisition, project administration. All authors read and approve the final manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

(1) Zhou Y, Wan C, Yang Y, Yang H, Wang S, Dai Z, et al. Highly stretchable, elastic, and ionic conductive hydrogel for artificial soft electronics. Adv Funct Mater. 2019;29:1–8. 10.1002/adfm.201806220.Search in Google Scholar

(2) Wang Q, Pan X, Guo J, Huang L, Ni Y. Lignin and cellulose derivatives-induced hydrogel with asymmetrical adhesion, strength, and electriferous properties for wearable bioelectrodes and self-powered sensors. Chem Eng J. 2021;414:128903. 10.1016/j.cej.2021.128903.Search in Google Scholar

(3) Zhang J, Zeng L, Qiao Z, Wang J, Yang HH. Functionalizing double-network hydrogels for applications in remote actuation and in low-temperature strain sensing. ACS Appl Mater & Interfaces. 2020;12:30247–58. 10.1021/acsami.0c10430.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(4) Bian H, Wei L, Lin C, Ma Q, Dai H, Zhu JY. Lignin-Containing Cellulose Nanofibril-Reinforced Polyvinyl Alcohol Hydrogels. ACS Sustain Chem & Eng. 2018;6:4821–8. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b04172.Search in Google Scholar

(5) Hu J, Wu Y, Yang Q, Zhou Q, Hui L, Liu Z, et al. One-pot freezing-thawing preparation of cellulose nanofibrils reinforced polyvinyl alcohol based ionic hydrogel strain sensor for human motion monitoring. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;275:118697. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118697.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(6) Pramanik R, Ganivada B, Ram F, Shanmuganathan K, Arockiarajan A. Influence of nanocellulose on mechanics and morphology of polyvinyl alcohol xerogels. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2018;90:275–83. 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2018.10.024.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(7) Noshirvani N, Hong W, Ghanbarzadeh B, Fasihi H, Montazami R. Study of cellulose nanocrystal doped starch-polyvinyl alcohol bionanocomposite films. Int J Biol Macromolecules. 2018;107:2065–74. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.10.083.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(8) Lu B, Lin F, Jiang X, Cheng J, Lu Q, Song J. One-pot assembly of microfibrillated cellulose reinforced PVA-borax hydrogels with self-healing and pH responsive properties. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2016;5:948–56. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b02279.Search in Google Scholar

(9) Bian H, Dong M, Chen L, Zhou X, Dai H. Comparison of mixed enzymatic pretreatment and post-treatment for enhancing the cellulose nanofibrillation efficiency. Bioresour Technol. 2019;293:122171. 10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122171.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(10) Wang S, Yu L, Wang S, Zhang L, Chen L, Xu X, et al. Strong, tough, ionic conductive, and freezing-tolerant all-natural hydrogel enabled by cellulose-bentonite coordination interactions. Nat Commun. 2022;13:1–11. 10.1038/s41467-022-30224-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(11) Borgohain MM, Joykumar T, Bhat SV. Studies on a nanocomposite solid polymer electrolyte with hydrotalcite as a filler. Solid State Ion. 2010;181:964–70. 10.1016/j.ssi.2010.05.040.Search in Google Scholar

(12) Fang C, Ma X, Qu X, Yan H. Structure and properties of an organic rectorite/poly(methyl methacrylate) nanocomposite gel polymer electrolyte by in situ synthesis. J Appl Polym Sci. 2010;114(5):2632–8. 10.1002/app.30872.Search in Google Scholar

(13) Wang M, Zhao F, Guo Z, Dong S. Poly(vinylidene fluoride-hexafluoropropylene)/organo-montmorillonite clays nanocomposite lithium polymer electrolytes. Electrochim Acta. 2004;49:3595–602. 10.1016/j.electacta.2004.03.028.Search in Google Scholar

(14) Liu T, Zhang C, Yuan J, Zhen Y, Li Y. Two-dimensional vermiculite nanosheets-modified porous membrane for non-aqueous redox flow batteries. J Power Sources. 2021;500:229987. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2021.229987.Search in Google Scholar

(15) Argüelles A, Khainakov SA, Rodríguez-Fernández J, Leoni M, Blanco JA, Marcos C. Chemical and physical characterization of iron-intercalated vermiculite compounds. Phys Chem Miner. 2011;38:569–80. 10.1007/s00269-011-0429-0.Search in Google Scholar

(16) Jing G, Catchmark JM. Surface area and porosity of acid hydrolyzed cellulose nanowhiskers and cellulose produced by gluconacetobacter xylinus. Carbohydr Polym. 2012;87(2):1026–37. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.07.060.Search in Google Scholar

(17) Wang G, Zhang Q, Wang Q, Zhou L, Gao G. Bio-Based Hydrogel Transducer for Measuring Human Motion with Stable Adhesion and Ultrahigh Toughness. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021a;13:24173–82. 10.1021/acsami.1c05098.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(18) Bian H, Luo J, Wang R, Zhou X, Dai H. Recyclable and reusable maleic acid for efficient production of cellulose nanofibrils with stable performance. ACS Sustain Chem & Eng. 2019;7(24):20022–31. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b05766.Search in Google Scholar

(19) Donohoe BS, Decker SR, Tucker MP, Himmel ME, Vinzant TB. Visualizing lignin coalescence and migration through maize cell walls following thermochemical pretreatment. Biotechnol & Bioeng. 2010;101(5):913–25. 10.1002/bit.21959.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(20) Luo J, Huang K, Xu Y, Fan Y. A comparative study of lignocellulosic nanofibrils isolated from celery using oxalic acid hydrolysis followed by sonication and mechanical fibrillation. Cellulose. 2019;26:5237–46. 10.1007/s10570-019-02454-5.Search in Google Scholar

(21) Bian H, Chen L, Gleisner R, Dai H, Zhu JY. Producing wood-based nanomaterials by rapid fractionation of wood at 80℃ using a recyclable acid hydrotrope. Green Chem. 2017;19(14):3370–9. 10.1039/C7GC00669A.Search in Google Scholar

(22) Liu L, Wang R, Yu J, Jiang J, Zheng Z, Hu L, et al. Robust self-standing chitin nanofiber/nanowhisker hydrogels with designed surface charges and ultralow mass content via gas phase coagulation. Biomacromolecules. 2016;17(11):3773–81. 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b01278.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(23) Shang K, Ye DD, Kang AH, Wang YT, Wang YZ. Robust and fire retardant borate-crosslinked poly (vinyl alcohol)/montmorillonite aerogel via melt-crosslink. Polymer. 2017;131:111–9. 10.1016/j.polymer.2017.07.022.Search in Google Scholar

(24) Macías-García A, Díaz-Díez M, Alfaro-Domínguez M, Carrasco-Amador J. Influence of chemical composition, porosity and fractal dimension on the electrical conductivity of carbon blacks. Heliyon. 2020;6:4024. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04024.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(25) Liu D, Sun X, Tian H, Maiti S, Ma Z. Effects of cellulose nanofibrils on the structure and properties on PVA nanocomposites. Cellulose. 2013;20(6):2981–9. 10.1007/s10570-013-0073-6.Search in Google Scholar

(26) Wang S, Chen F, Song X. Preparation and characterization of lignin-based membrane material. BioResources. 2015;10:5586–95. 10.15376/biores.10.3.5596-5606.Search in Google Scholar

(27) Chang C, Lue A, Zhang L. Effects of crosslinking methods on structure and properties of cellulose/PVA hydrogels. Macromol Chem Phys. 2008;12:1266–73. 10.1002/macp.200800161.Search in Google Scholar

(28) Demirel S. Temperature dependent polarization effect and capacitive performance enhancement of PVA-borax gel electrolyte. Int J Electrochem Sci. 2020;15:2439–48. 10.20964/2020.03.75.Search in Google Scholar

(29) Li J, Zhang Z, Cao X, Liu Y, Quan C. The role of electrostatic repulsion in the gelation of poly(vinyl alcohol)/borax aqueous solutions. Soft Matter. 2018;14:6767–73. 10.1039/C8SM01019F.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(30) Tavakoli J, Tang Y. Honey/PVA hybrid wound dressings with controlled release of antibiotics: Structural, physico-mechanical and in-vitro biomedical studies. Mater Sci & Eng C. 2017;77:318–25. 10.1016/j.msec.2017.03.272.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(31) Jie MA, Cz A, Yla B, Dong XA, Zw A. Highly stretchable, self-healing, and strain-sensitive based on double-crosslinked nanocomposite hydrogel. Compos Commun. 2020;17:22–7. 10.1016/j.coco.2019.10.007.Search in Google Scholar

(32) Cui H, Jiang W, Wang C, Ji X, Liu Y, Yang G, et al. Lignin nanofiller-reinforced composites hydrogels with long-lasting adhesiveness, toughness, excellent self-healing, conducting, ultraviolet-blocking and antibacterial properties. Composites, Part B Eng. 2021;225:109316. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2021.109316.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Chitosan nanocomposite film incorporating Nigella sativa oil, Azadirachta indica leaves’ extract, and silver nanoparticles

- Effect of Zr-doped CaCu3Ti3.95Zr0.05O12 ceramic on the microstructure, dielectric properties, and electric field distribution of the LDPE composites

- Effects of dry heating, acetylation, and acid pre-treatments on modification of potato starch with octenyl succinic anhydride (OSA)

- Loading conditions impact on the compression fatigue behavior of filled styrene butadiene rubber

- Characterization and compatibility of bio-based PA56/PET

- Study on the aging of three typical rubber materials under high- and low-temperature cyclic environment

- Numerical simulation and experimental research of electrospun polyacrylonitrile Taylor cone based on multiphysics coupling

- Experimental investigation of properties and aging behavior of pineapple and sisal leaf hybrid fiber-reinforced polymer composites

- Influence of temperature distribution on the foaming quality of foamed polypropylene composites

- Enzyme-catalyzed synthesis of 4-methylcatechol oligomer and preliminary evaluations as stabilizing agent in polypropylene

- Molecular dynamics simulation of the effect of the thermal and mechanical properties of addition liquid silicone rubber modified by carbon nanotubes with different radii

- Incorporation of poly(3-acrylamidopropyl trimethylammonium chloride-co-acrylic acid) branches for good sizing properties and easy desizing from sized cotton warps

- Effect of matrix composition on properties of polyamide 66/polyamide 6I-6T composites with high content of continuous glass fiber for optimizing surface performance

- Preparation and properties of epoxy-modified thermosetting phenolic fiber

- Thermal decomposition reaction kinetics and storage life prediction of polyacrylate pressure-sensitive adhesive

- Effect of different proportions of CNTs/Fe3O4 hybrid filler on the morphological, electrical and electromagnetic interference shielding properties of poly(lactic acid) nanocomposites

- Doping silver nanoparticles into reverse osmosis membranes for antibacterial properties

- Melt-blended PLA/curcumin-cross-linked polyurethane film for enhanced UV-shielding ability

- The affinity of bentonite and WO3 nanoparticles toward epoxy resin polymer for radiation shielding

- Prolonged action fertilizer encapsulated by CMC/humic acid

- Preparation and experimental estimation of radiation shielding properties of novel epoxy reinforced with Sb2O3 and PbO

- Fabrication of polylactic acid nanofibrous yarns for piezoelectric fabrics

- Copper phenyl phosphonate for epoxy resin and cyanate ester copolymer with improved flame retardancy and thermal properties

- Synergistic effect of thermal oxygen and UV aging on natural rubber

- Effect of zinc oxide suspension on the overall filler content of the PLA/ZnO composites and cPLA/ZnO composites

- The role of natural hybrid nanobentonite/nanocellulose in enhancing the water resistance properties of the biodegradable thermoplastic starch

- Performance optimization of geopolymer mortar blending in nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber based on set pair analysis

- Preparation of (La + Nb)-co-doped TiO2 and its polyvinylidene difluoride composites with high dielectric constants

- Effect of matrix composition on the performance of calcium carbonate filled poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composites

- Low-temperature self-healing polyurethane adhesives via dual synergetic crosslinking strategy

- Leucaena leucocephala oil-based poly malate-amide nanocomposite coating material for anticorrosive applications

- Preparation and properties of modified ammonium polyphosphate synergistic with tris(2-hydroxyethyl) isocynurate for flame-retardant LDPE

- Thermal response of double network hydrogels with varied composition

- The effect of coated calcium carbonate using stearic acid on the recovered carbon black masterbatch in low-density polyethylene composites

- Investigation of MXene-modified agar/polyurethane hydrogel elastomeric repair materials with tunable water absorption

- Damping performance analysis of carbon black/lead magnesium niobite/epoxy resin composites

- Molecular dynamics simulations of dihydroxylammonium 5,5′-bistetrazole-1,1′-diolate (TKX-50) and TKX-50-based PBXs with four energetic binders

- Preparation and characterization of sisal fibre reinforced sodium alginate gum composites for non-structural engineering applications

- Study on by-products synthesis of powder coating polyester resin catalyzed by organotin

- Ab initio molecular dynamics of insulating paper: Mechanism of insulating paper cellobiose cracking at transient high temperature

- Effect of different tin neodecanoate and calcium–zinc heat stabilizers on the thermal stability of PVC

- High-strength polyvinyl alcohol-based hydrogel by vermiculite and lignocellulosic nanofibrils for electronic sensing

- Impacts of micro-size PbO on the gamma-ray shielding performance of polyepoxide resin

- Influence of the molecular structure of phenylamine antioxidants on anti-migration and anti-aging behavior of high-performance nitrile rubber composites

- Fiber-reinforced polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel via in situ fiber formation

- Preparation and performance of homogenous braids-reinforced poly (p-phenylene terephthamide) hollow fiber membranes

- Synthesis of cadmium(ii) ion-imprinted composite membrane with a pyridine functional monomer and characterization of its adsorption performance

- Impact of WO3 and BaO nanoparticles on the radiation shielding characteristics of polydimethylsiloxane composites

- Comprehensive study of the radiation shielding feature of polyester polymers impregnated with iron filings

- Preparation and characterization of polymeric cross-linked hydrogel patch for topical delivery of gentamicin

- Mechanical properties of rCB-pigment masterbatch in rLDPE: The effect of processing aids and water absorption test

- Pineapple fruit residue-based nanofibre composites: Preparation and characterizations

- Effect of natural Indocalamus leaf addition on the mechanical properties of epoxy and epoxy-carbon fiber composites

- Utilization of biosilica for energy-saving tire compounds: Enhancing performance and efficiency

- Effect of capillary arrays on the profile of multi-layer micro-capillary films

- A numerical study on thermal bonding with preheating technique for polypropylene microfluidic device

- Development of modified h-BN/UPE resin for insulation varnish applications

- High strength, anti-static, thermal conductive glass fiber/epoxy composites for medical devices: A strategy of modifying fibers with functionalized carbon nanotubes

- Effects of mechanical recycling on the properties of glass fiber–reinforced polyamide 66 composites in automotive components

- Bentonite/hydroxyethylcellulose as eco-dielectrics with potential utilization in energy storage

- Study on wall-slipping mechanism of nano-injection polymer under the constant temperature fields

- Synthesis of low-VOC unsaturated polyester coatings for electrical insulation

- Enhanced apoptotic activity of Pluronic F127 polymer-encapsulated chlorogenic acid nanoparticles through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in liver cancer cells and in vivo toxicity studies in zebrafish

- Preparation and performance of silicone-modified 3D printing photosensitive materials

- A novel fabrication method of slippery lubricant-infused porous surface by thiol-ene click chemistry reaction for anti-fouling and anti-corrosion applications

- Development of polymeric IPN hydrogels by free radical polymerization technique for extended release of letrozole: Characterization and toxicity evaluation

- Tribological characterization of sponge gourd outer skin fiber-reinforced epoxy composite with Tamarindus indica seed filler addition using the Box–Behnken method

- Stereocomplex PLLA–PBAT copolymer and its composites with multi-walled carbon nanotubes for electrostatic dissipative application

- Enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of Krestin–chitosan nanocomplex for cancer medication via activation of the mitochondrial intrinsic pathway

- Variation in tungsten(vi) oxide particle size for enhancing the radiation shielding ability of silicone rubber composites

- Damage accumulation and failure mechanism of glass/epoxy composite laminates subjected to repeated low velocity impacts

- Gamma-ray shielding analysis using the experimental measurements for copper(ii) sulfate-doped polyepoxide resins

- Numerical simulation into influence of airflow channel quantities on melt-blowing airflow field in processing of polymer fiber

- Cellulose acetate oleate-reinforced poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composite materials

- Radiation shielding capability and exposure buildup factor of cerium(iv) oxide-reinforced polyester resins

- Recyclable polytriazole resins with high performance based on Diels-Alder dynamic covalent crosslinking

- Adsorption and recovery of Cr(vi) from wastewater by Chitosan–Urushiol composite nanofiber membrane

- Comprehensive performance evaluation based on electromagnetic shielding properties of the weft-knitted fabrics made by stainless steel/cotton blended yarn

- Review Articles

- Preparation and application of natural protein polymer-based Pickering emulsions

- Wood-derived high-performance cellulose structural materials

- Flammability properties of polymers and polymer composites combined with ionic liquids

- Polymer-based nanocarriers for biomedical and environmental applications

- A review on semi-crystalline polymer bead foams from stirring autoclave: Processing and properties

- Rapid Communication

- Preparation and characterization of magnetic microgels with linear thermosensitivity over a wide temperature range

- Special Issue: Biodegradable and bio-based polymers: Green approaches (Guest Editors: Kumaran Subramanian, A. Wilson Santhosh Kumar, and Venkatajothi Ramarao)

- Synthesis and characterization of proton-conducting membranes based on bacterial cellulose and human nail keratin

- Fatigue behaviour of Kevlar/carbon/basalt fibre-reinforced SiC nanofiller particulate hybrid epoxy composite

- Effect of citric acid on thermal, phase morphological, and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactide)-b-poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(l-lactide)/thermoplastic starch blends

- Dose-dependent cytotoxicity against lung cancer cells via green synthesized ZnFe2O4/cellulose nanocomposites

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Chitosan nanocomposite film incorporating Nigella sativa oil, Azadirachta indica leaves’ extract, and silver nanoparticles

- Effect of Zr-doped CaCu3Ti3.95Zr0.05O12 ceramic on the microstructure, dielectric properties, and electric field distribution of the LDPE composites

- Effects of dry heating, acetylation, and acid pre-treatments on modification of potato starch with octenyl succinic anhydride (OSA)

- Loading conditions impact on the compression fatigue behavior of filled styrene butadiene rubber

- Characterization and compatibility of bio-based PA56/PET

- Study on the aging of three typical rubber materials under high- and low-temperature cyclic environment

- Numerical simulation and experimental research of electrospun polyacrylonitrile Taylor cone based on multiphysics coupling

- Experimental investigation of properties and aging behavior of pineapple and sisal leaf hybrid fiber-reinforced polymer composites

- Influence of temperature distribution on the foaming quality of foamed polypropylene composites

- Enzyme-catalyzed synthesis of 4-methylcatechol oligomer and preliminary evaluations as stabilizing agent in polypropylene

- Molecular dynamics simulation of the effect of the thermal and mechanical properties of addition liquid silicone rubber modified by carbon nanotubes with different radii

- Incorporation of poly(3-acrylamidopropyl trimethylammonium chloride-co-acrylic acid) branches for good sizing properties and easy desizing from sized cotton warps

- Effect of matrix composition on properties of polyamide 66/polyamide 6I-6T composites with high content of continuous glass fiber for optimizing surface performance

- Preparation and properties of epoxy-modified thermosetting phenolic fiber

- Thermal decomposition reaction kinetics and storage life prediction of polyacrylate pressure-sensitive adhesive

- Effect of different proportions of CNTs/Fe3O4 hybrid filler on the morphological, electrical and electromagnetic interference shielding properties of poly(lactic acid) nanocomposites

- Doping silver nanoparticles into reverse osmosis membranes for antibacterial properties

- Melt-blended PLA/curcumin-cross-linked polyurethane film for enhanced UV-shielding ability

- The affinity of bentonite and WO3 nanoparticles toward epoxy resin polymer for radiation shielding

- Prolonged action fertilizer encapsulated by CMC/humic acid

- Preparation and experimental estimation of radiation shielding properties of novel epoxy reinforced with Sb2O3 and PbO

- Fabrication of polylactic acid nanofibrous yarns for piezoelectric fabrics

- Copper phenyl phosphonate for epoxy resin and cyanate ester copolymer with improved flame retardancy and thermal properties

- Synergistic effect of thermal oxygen and UV aging on natural rubber

- Effect of zinc oxide suspension on the overall filler content of the PLA/ZnO composites and cPLA/ZnO composites

- The role of natural hybrid nanobentonite/nanocellulose in enhancing the water resistance properties of the biodegradable thermoplastic starch

- Performance optimization of geopolymer mortar blending in nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber based on set pair analysis

- Preparation of (La + Nb)-co-doped TiO2 and its polyvinylidene difluoride composites with high dielectric constants

- Effect of matrix composition on the performance of calcium carbonate filled poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composites

- Low-temperature self-healing polyurethane adhesives via dual synergetic crosslinking strategy

- Leucaena leucocephala oil-based poly malate-amide nanocomposite coating material for anticorrosive applications

- Preparation and properties of modified ammonium polyphosphate synergistic with tris(2-hydroxyethyl) isocynurate for flame-retardant LDPE

- Thermal response of double network hydrogels with varied composition

- The effect of coated calcium carbonate using stearic acid on the recovered carbon black masterbatch in low-density polyethylene composites

- Investigation of MXene-modified agar/polyurethane hydrogel elastomeric repair materials with tunable water absorption

- Damping performance analysis of carbon black/lead magnesium niobite/epoxy resin composites

- Molecular dynamics simulations of dihydroxylammonium 5,5′-bistetrazole-1,1′-diolate (TKX-50) and TKX-50-based PBXs with four energetic binders

- Preparation and characterization of sisal fibre reinforced sodium alginate gum composites for non-structural engineering applications

- Study on by-products synthesis of powder coating polyester resin catalyzed by organotin

- Ab initio molecular dynamics of insulating paper: Mechanism of insulating paper cellobiose cracking at transient high temperature

- Effect of different tin neodecanoate and calcium–zinc heat stabilizers on the thermal stability of PVC

- High-strength polyvinyl alcohol-based hydrogel by vermiculite and lignocellulosic nanofibrils for electronic sensing

- Impacts of micro-size PbO on the gamma-ray shielding performance of polyepoxide resin

- Influence of the molecular structure of phenylamine antioxidants on anti-migration and anti-aging behavior of high-performance nitrile rubber composites

- Fiber-reinforced polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel via in situ fiber formation

- Preparation and performance of homogenous braids-reinforced poly (p-phenylene terephthamide) hollow fiber membranes

- Synthesis of cadmium(ii) ion-imprinted composite membrane with a pyridine functional monomer and characterization of its adsorption performance

- Impact of WO3 and BaO nanoparticles on the radiation shielding characteristics of polydimethylsiloxane composites

- Comprehensive study of the radiation shielding feature of polyester polymers impregnated with iron filings

- Preparation and characterization of polymeric cross-linked hydrogel patch for topical delivery of gentamicin

- Mechanical properties of rCB-pigment masterbatch in rLDPE: The effect of processing aids and water absorption test

- Pineapple fruit residue-based nanofibre composites: Preparation and characterizations

- Effect of natural Indocalamus leaf addition on the mechanical properties of epoxy and epoxy-carbon fiber composites

- Utilization of biosilica for energy-saving tire compounds: Enhancing performance and efficiency

- Effect of capillary arrays on the profile of multi-layer micro-capillary films

- A numerical study on thermal bonding with preheating technique for polypropylene microfluidic device

- Development of modified h-BN/UPE resin for insulation varnish applications

- High strength, anti-static, thermal conductive glass fiber/epoxy composites for medical devices: A strategy of modifying fibers with functionalized carbon nanotubes

- Effects of mechanical recycling on the properties of glass fiber–reinforced polyamide 66 composites in automotive components

- Bentonite/hydroxyethylcellulose as eco-dielectrics with potential utilization in energy storage

- Study on wall-slipping mechanism of nano-injection polymer under the constant temperature fields

- Synthesis of low-VOC unsaturated polyester coatings for electrical insulation

- Enhanced apoptotic activity of Pluronic F127 polymer-encapsulated chlorogenic acid nanoparticles through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in liver cancer cells and in vivo toxicity studies in zebrafish

- Preparation and performance of silicone-modified 3D printing photosensitive materials

- A novel fabrication method of slippery lubricant-infused porous surface by thiol-ene click chemistry reaction for anti-fouling and anti-corrosion applications

- Development of polymeric IPN hydrogels by free radical polymerization technique for extended release of letrozole: Characterization and toxicity evaluation

- Tribological characterization of sponge gourd outer skin fiber-reinforced epoxy composite with Tamarindus indica seed filler addition using the Box–Behnken method

- Stereocomplex PLLA–PBAT copolymer and its composites with multi-walled carbon nanotubes for electrostatic dissipative application

- Enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of Krestin–chitosan nanocomplex for cancer medication via activation of the mitochondrial intrinsic pathway

- Variation in tungsten(vi) oxide particle size for enhancing the radiation shielding ability of silicone rubber composites

- Damage accumulation and failure mechanism of glass/epoxy composite laminates subjected to repeated low velocity impacts

- Gamma-ray shielding analysis using the experimental measurements for copper(ii) sulfate-doped polyepoxide resins

- Numerical simulation into influence of airflow channel quantities on melt-blowing airflow field in processing of polymer fiber

- Cellulose acetate oleate-reinforced poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composite materials

- Radiation shielding capability and exposure buildup factor of cerium(iv) oxide-reinforced polyester resins

- Recyclable polytriazole resins with high performance based on Diels-Alder dynamic covalent crosslinking

- Adsorption and recovery of Cr(vi) from wastewater by Chitosan–Urushiol composite nanofiber membrane

- Comprehensive performance evaluation based on electromagnetic shielding properties of the weft-knitted fabrics made by stainless steel/cotton blended yarn

- Review Articles

- Preparation and application of natural protein polymer-based Pickering emulsions

- Wood-derived high-performance cellulose structural materials

- Flammability properties of polymers and polymer composites combined with ionic liquids

- Polymer-based nanocarriers for biomedical and environmental applications

- A review on semi-crystalline polymer bead foams from stirring autoclave: Processing and properties

- Rapid Communication

- Preparation and characterization of magnetic microgels with linear thermosensitivity over a wide temperature range

- Special Issue: Biodegradable and bio-based polymers: Green approaches (Guest Editors: Kumaran Subramanian, A. Wilson Santhosh Kumar, and Venkatajothi Ramarao)

- Synthesis and characterization of proton-conducting membranes based on bacterial cellulose and human nail keratin

- Fatigue behaviour of Kevlar/carbon/basalt fibre-reinforced SiC nanofiller particulate hybrid epoxy composite

- Effect of citric acid on thermal, phase morphological, and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactide)-b-poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(l-lactide)/thermoplastic starch blends

- Dose-dependent cytotoxicity against lung cancer cells via green synthesized ZnFe2O4/cellulose nanocomposites