Abstract

In this work, the attenuation properties of silicon rubber (SR) composites reinforced by both micro- and nano-sized Tungsten trioxide (WO3) particles are studied. Different SR composites with different combinations of micro-WO3 and nano-WO3 have been prepared. The main composite, SR-(WO3)60m (40% SR containing 60% micro-WO3), and other compositions were prepared by replacing percentages of microparticles with nanoparticles of WO3. The linear attenuation coefficient for these composites was measured in the range of 0.06–1.333 MeV. The existence of micro and nanoparticles together may result in enhanced interactions with incoming photons, leading to greater shielding. In other words, micro-WO3 and nano-WO3 have various sizes and surface areas. At 0.06 MeV, we notice a distinguished decrease in the half value layer (HVL) from SR-W60m to SR-W60n. The sequence of reducing HVL values (SR-(WO3)60m > SR-(WO3)60n > SR-(WO3)40m20n > SR-(WO3)20m40n > SR-(WO3)30m30n) suggest that the inclusion of both micro- and nano-WO3 contributes to more efficient radiation shielding compared to the reference material. The radiation shielding efficiency (RSE) for SR-(WO3)30m30n at 0.662 MeV is 38.40%. This means that if a beam of photons with energy of 0.662 MeV interacts with SR-W40m20n sample, only 38.12% of the photons are successfully absorbed or stopped, whereas the remaining 61.88% can pass through this sample. At 1.333 MeV, the lowest RSE is observed, which means that the prepared composites have weak attenuation ability at higher energy levels.

1 Introduction

Radiation protection materials are an essential part of the bigger plan to protect people and the environment from the harmful effects of ionizing radiation. There is a greater need than ever for radiation shielding that works and can be counted on due to the spread of technologies like nuclear power, medical imaging, and industrial processes that use radioactive materials (1,2,3). Gamma rays, X-rays, and high-energy particles are all examples of these. People having medical procedures, and people in the general public are exposed to less radiation (4,5,6). The use of micro and nanoparticles of tungsten trioxide (WO3) mixed with polymers is an interesting new development in this area. WO3 is added to the rubber at the micro and nanoscales to improve its ability to block radiation (7,8).

Lead and concrete have been used as shielding materials to block ionizing radiation for a long time because they have high atomic number and density. For instance, lead is hazardous when produced, used, or thrown away and pollutes the environment. Lead and concrete are less practical and more challenging to use in some circumstances due to their weight (9,10). Polymers can be formed into various shapes, making it possible to create designs that meet particular requirements. Particularly useful in settings like hospitals where conditions are not always ideal. Polymers can be less expensive than concrete and lead, which could reduce the project’s overall cost. Polymers present an exciting and successful method to enhance radiation shielding because of their unique qualities and capacity for shaping (11,12,13,14,15,16).

Silicon rubber (SR) is a beneficial substance that can be applied in various ways due to its unique characteristics and adaptability. SR is the best material for sealing and insulating electronic components due to its excellent electrical insulation properties and ability to shield electronic components from moisture and dust (17). It is used in the medical industry to create long-lasting, allergy-free implants and devices. It is used in the automotive industry to make hoses, gaskets, and seals because SR can withstand various temperature changes and chemical contact. It creates seals for windows, doors, and appliances because it is solid and flexible. Neither air nor water can escape from these seals. It can be utilized in ionizing radiation-related industrial and medical applications by combining it with materials like micro- and nano-WO3 (18).

Heavy metal oxides like WO3 must be used in radiation shielding, especially when combined with polymers. Polymers can only block some radiation in the environment because they are not very dense. It is possible to increase the overall density of polymers by incorporating dense substances like WO3, improving their ability to block radiation. WO3 effectively reflects ionizing radiation like gamma rays and X-rays because of its high atomic number and density (19). The capacity of polymers to absorb and scatter radiation increases when WO3 particles are added. Shielding solutions can be created that are lightweight, portable, efficient, and adaptable enough to handle the demands of numerous applications by combining these two factors. WO3 functions as a radiation shield because it offers sufficient protection and is simple to use. It fixes the polymer density issue and provides an environmentally friendly substitute for heavy metals (20).

Nanotechnology is a big part of modern scientific and technological progress (21), especially when using WO3 nanoparticles. These structures are between 1 and 100 nm in size. They have features that make them different from their bulk counterparts and give them several advantages in various fields. SR can block radiation with the help of WO3 nanoparticles. This is done by carefully controlling the size and location of the particles inside the material. Nanoparticles have more surface area per unit volume, which makes them more reactive and effective. Nanotechnology has made it possible to change the way things work so they can be used for many different things (22). The structure stays together better, and the particles are spread more evenly when a changed nanoparticle works well with polymers. Flexible, lightweight protective material solutions are easy to make and have many medical and industrial uses (23).

In previous related works (24,25), the authors discussed the effect of adding microparticles or WO3 nanoparticles to liquid silicone rubber, while in this work, the effect of the two sizes combined within the composite in different proportions is studied. In this work, different new SR composition has been prepared and the radiation shielding characteristics have been determined experimentally using high-pure germanium (HPGe) detector and different radioactive point sources (Cs-137, Co-60, and Am-241). The idea of the work is to study the attenuation coefficients of some SR composites containing micro and nanoparticles together in the same mixture with different ratios and the effect of these percentages on the shielding efficiency.

2 Materials and method

The materials used in this work are liquid silicon rubber (LSR) with its hardener and different sizes (micro and nano) of WO3. The LSR is a two-component system, where long polysiloxane chains are reinforced with specially treated silica. Component A contains a platinum catalyst and Component B contains methylhydrogensiloxane as a cross-linker and an alcohol inhibitor. The hardener for silicone rubber materials comprising a silane compound comprises a 2-hydroxy-propionic acid alkyl ester radical. Mix 100 parts by weight of SR with corresponding 5 parts by weight of hardener. The LSR was purchased from Al-Nasser Company in Alexandria, Egypt, with a density of 1.25 g·cm−3 and a melting point of 250°C. The WO3 microparticles were purchased from the Egyptian Chemical Company, and their purity rate was 99.3%, and their average particle size was 50

SEM and TEM images of micro- and nano-WO3, respectively.

Composites’ compositions, codes, and densities

| Codes | Composition percentage wt% | Density (g·cm−3) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SR | WO3 | |||

| Micro-WO3 | Nano-WO3 | |||

| SR-(WO3)60m | 40 | 60 | ̶ | 2.365 ± 0.007 |

| SR-(WO3)40m20n | 40 | 40 | 20 | 2.374 ± 0.009 |

| SR-(WO3)30m30n | 40 | 30 | 30 | 2.380 ± 0.011 |

| SR-(WO3)20m40n | 40 | 20 | 40 | 2.375 ± 0.009 |

| SR-(WO3)60n | 40 | ̶ | 60 | 2.371 ± 0.006 |

The ingredients were mixed according to Table 1 to obtain a homogeneous composite and pour it into cylindrical molds with a thickness of 2 cm. The compositions have been measured experimentally to calculate the attenuation parameters using narrow beam technique consisting of HPGe detector, radioactive point sources, and lead collimator (28,29,30,31,32,33). The sources emit four lines, which are used in the measurements, from 0.060 MeV (emitted from Am-241) to 1.333 MeV (emitted from Co-60). The geometry of experimental technique is shown in Figure 2, where the linear attenuation coefficient (LAC) has been calculated according to Beer–Lambert attenuation law, where the mechanism of the measurements and equations of LAC and other attenuation factors such as half value layer (HVL) and tenth value layer (TVL) are mentioned in previous studies (34,35,36,37,38).

where RSE is the radiation shielding efficiency, C and C 0 are the count rate in the presence and absence of SR composition according to the emitted photons which are detected by the HPGe detector and t represents the thickness of the composite.

The experimental setup for attenuation coefficient measurements.

3 Results and discussion

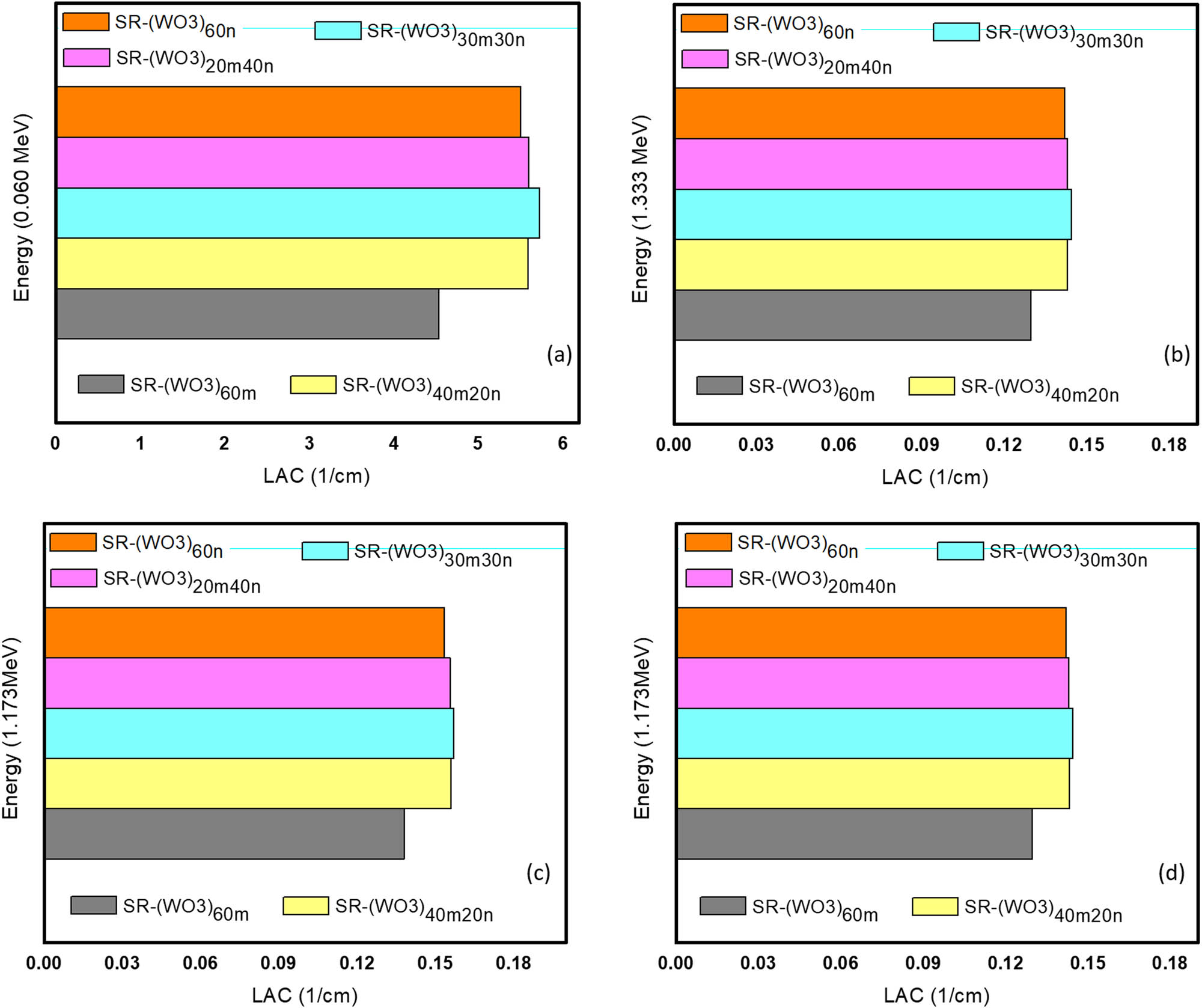

The experimental part in this work involved preparing different SR composites with different combinations of micro-WO3 and nano-WO3. The LAC for these composites was measured in the range of 0.06–1.333 MeV. Analyzing the radiation attenuation factors in the examined energy range for these composites gives insights into their gamma ray shielding performance. The LAC denotes how well a composite attenuates photons, with higher values indicating superior shielding ability. In Figure 3, we plotted the LAC for the prepared composites with WO3. Among the micro-WO3-containing composites (SR-(WO3)60m, SR-(WO3)40m20n, SR-(WO3)30m30n, SR-(WO3)20m40n, and SR-(WO3)60n), SR-(WO3)30m30n shows the highest LAC, followed by SR-(WO3)20m40n and SR-(WO3)40m20n. The high LAC value found for SR-(WO3)30m30n composite can be ascribed to the synergistic impact of combining both micro-WO3 and WO3 nanoparticles. This combination improves the overall gamma ray shielding features of the prepared SR samples. The existence of micro and nanoparticles may result in enhanced interactions with incoming photons, leading to greater shielding. In other words, micro-WO3 and nano-WO3 have various sizes and surface areas. The existence of nano-WO3 provides a larger surface area compared to micro-WO3, allowing more interactions with incoming photons, while if we add micro and nanoparticles together, this increases the surface area better, which increases the possibility of better interactions. On the other hand, SR-(WO3)30m30n, which contains micro- and nano-WO3, exhibits a comparatively high LAC, suggesting that micro- and nano-WO3 together have a favorable impact on radiation attenuation.

The variation in LAC values of prepared composites at different experimental energies: (a) at 0.060 MeV, (b) at 0.662 MeV, (c) 1.173 MeV, and (d) 1.333 MeV.

The smallest LAC value reported for SR-W60m may be ascribed to its composition consisting of micro-WO3. At 0.06 MeV, the interactions between the photons and micro-WO3 might lead to a comparatively lower attenuation ability compared to SR composites with nano-WO3 or a combination of micro- and nano-WO3.

In Figure 4, we calculated the ratios of LAC values for SR-(WO3)40m20n, SR-(WO3)30m30n, SR-(WO3)20m40n, and SR-(WO3)60n to the LAC value of SR-(WO3)60m. The evaluations of the ratios of LAC give useful information on the comparative radiation shielding performances of several SR composites. By normalizing the LAC values to the reference composite (i.e., SR-(WO3)60m), the ratios give a direct comparison of how the remaining composites perform with regard to radiation protection efficacy. This parameter helps distinguish which compositions display weaker or stronger radiation shielding in comparison with a standard material, helping in the estimation and optimization of SR composition for improved radiation protection utilizations. In the selected energy range, there appears to be a harmonious tendency in the ratios of LAC values for SR-(WO3)40m20n, SR-(WO3)30m30n, SR-(WO3)20m40n, and SR-(WO3)60n compared to the reference composite (i.e. SR-(WO3)60m). The ratios consistently varied between 1.095 to 1.263, suggesting that these composites in general exhibit moderately larger LAC values in comparison with SR-(WO3)60m. From Figure 4, the ratios higher than one imply that all the prepared composites have higher LAC than the reference composite (SR-(WO3)60m). This means that the four composites with nano-WO3 or combination of micro- and nano-WO3 are more efficient in shieling the photons compared to the reference sample. Also, Figure 4 shows that the composites with both micro- and nano-WO3 (SR-(WO3)40m20n, SR-(WO3)30m30n, and SR-(WO3)20m40n) have slightly higher ratios in comparison with the composite with only nano-WO3 (SR-(WO3)60n). This affirms that the addition of both particle sizes can participate to enhance radiation shielding.

The ratio factor between SR-(WO3)60m and other prepared SR composites.

We determined the HVL for the prepared composites and illustrated the findings in Figure 5. Analyzing the HVL data gives perspectives into the radiation shielding abilities of the prepared composites at varying energy ranges. Higher HVL values imply weaker radiation attenuation effectiveness, as a bigger thickness is required to shield the intensity of the photons by half. Comparing the HVL values for different compositions allows us to estimate which composite provides stronger or weaker shielding. At 0.06 MeV, we notice a distinguished decrease in the HVL from SR-(WO3)60m to SR-(WO3)60n. The sequence of reducing HVL values (SR-(WO3)60m > SR-(WO3)60n > SR-(WO3)40m20n > SR-(WO3)20m40n > SR-(WO3)60n) suggest that the inclusion of both micro- and nano-WO3 contributes to more efficient radiation shielding compared to the reference material, which is similar to the result obtained in the previous figure. At 0.06 MeV, a high numerical difference is found between the values of HVL for SR-(WO3)60m and SR-(WO3)60n. This numerical comparison confirms that SR-(WO3)60n, which consists of nano-WO3, has better radiation attenuation compared to SR-W60m. The lesser HVL value for SR-(WO3)60n implies that a smaller thickness is required to attain the same level of radiation shielding as SR-(WO3)60m, displaying the benefit of utilizing nano-WO3. At higher energies, the difference in HVL between SR-(WO3)60m and SR-(WO3)60n is more pronounced, which again show the better attenuation performance of the composite with nano-WO3 compared to the sample with solely micro-WO3.

The HVL of SR composite as a function of photon energy.

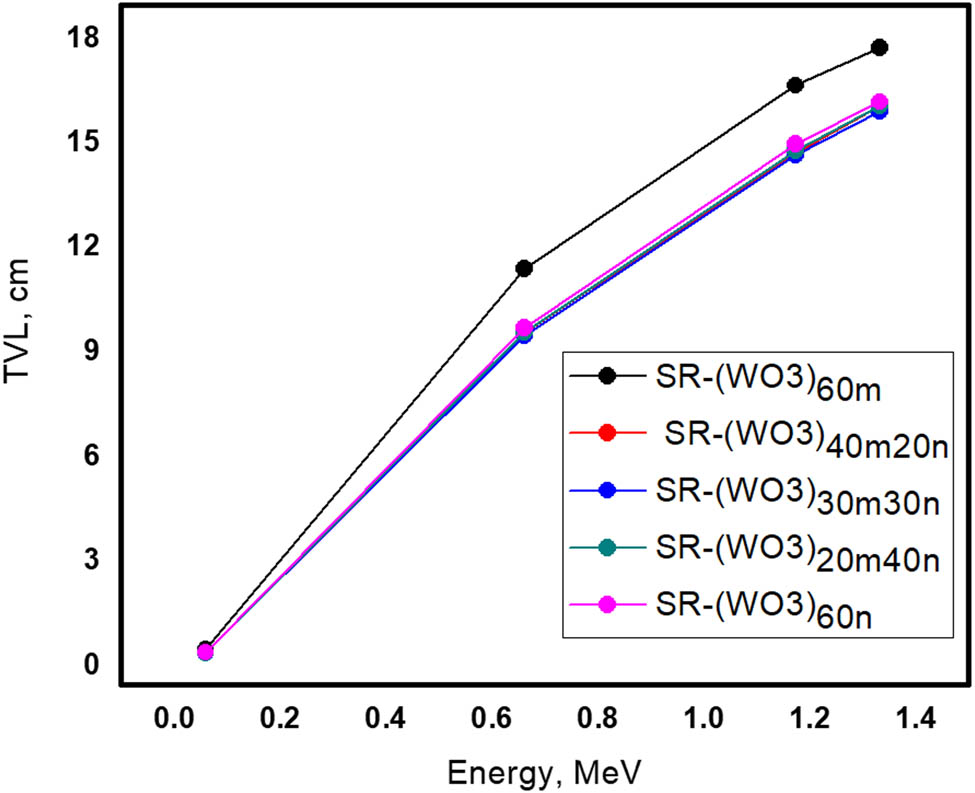

We calculated the TVL for the composites and compared the HVL and TVL for SR-(WO3)60n and SR-(WO3)40m20n at 0.06 MeV (Figure 6). We note that the HVL is smaller than the TVL and this is correct for both composites given in Figure 6. For example, the HVL for SR-W60m is 0.15 cm, while its TVL is 0.51 cm. The HVL is lesser than the TVL since the HVL represents a quicker lessening in the intensity of the photons. When a beam of photons moves via a composite with a thickness equivalent to the HVL, its intensity decreases to 50%. But for the TVL, the intensity of the photons is decreased to only one-tenth of its initial level after moving through a thicker layer.

The TVL of SR composite as a function of photon energy.

This link reflects the exponential nature of photons attenuation via a medium. This means that the intensity drops quickly when the thickness of the medium increases. Hence, the HVL is naturally leaser than the TVL.

In Figure 7, we plotted the mean free path (MFP) for the prepared composites. Clearly, at 0.06 MeV, the SR-(WO3)30m30n sample has the least MFP, followed by SR-(WO3)20m40n. This order suggests that, at this energy level, the inclusion of nano-WO3 in these two composites leads to a bit shorter distance photons can move compared to the other materials. SR-(WO3)60n, with a higher proportion of nano-WO3, also possesses a slightly reduced MFP in comparison with SR-(WO3)60m. With the increase in the energy of the photons, a similar pattern persists. The results at 0.662 MeV demonstrated that the addition of nano-WO3 leads to a reduction in the MFP, since the four composites with noano-WO3 have lower MFP than SR-(WO3)60m. The energy has a notable impact on the MFP of these composites, since the MFP for the current composites is in the order of 0.18–0.22 cm at 0.060 MeV, 4.22–4.95 cm at 0.662 MeV, and 7.04–7.71 cm at 1.333 MeV. If we compare the MFP for SR-(WO3)60m at 0.060 and 1.333 MeV, we found a very big difference between the MFP of this glass at these two energies. Specifically, the MFP at 0.060 MeV measures 0.22 cm, while at 1.333 MeV, it reaches 7.71 cm. This comparison between the MFP for SR-(WO3)60m at 0.060 and 1.333 MeV shows a substantial raise in MFP as the energy of the radiation increases. This high difference showcases the varying interaction processes between the incoming photons and the composites at different energy ranges. At 0.060 MeV, the comparatively small MFP value implies that the photons with energy of 0.06 MeV can move an average distance of about 0.22 cm within the SR-(WO3)60m sample before being attenuated. This suggests a quicker interaction between photons and the SR-W60m sample, leading to a faster reduction in intensity. Contrastly, at 1.333 MeV, the high MFP value of 7.71 cm indicates that photons with high energy can penetrate deeper into the SR-(WO3)60m, interacting over a longer distance before being shielded. The high MFP signifies a higher chance for the photons to move through the medium, leading to a slower decrease in the intensity over a greater distance.

The MFP of SR composite as a function of photon energy.

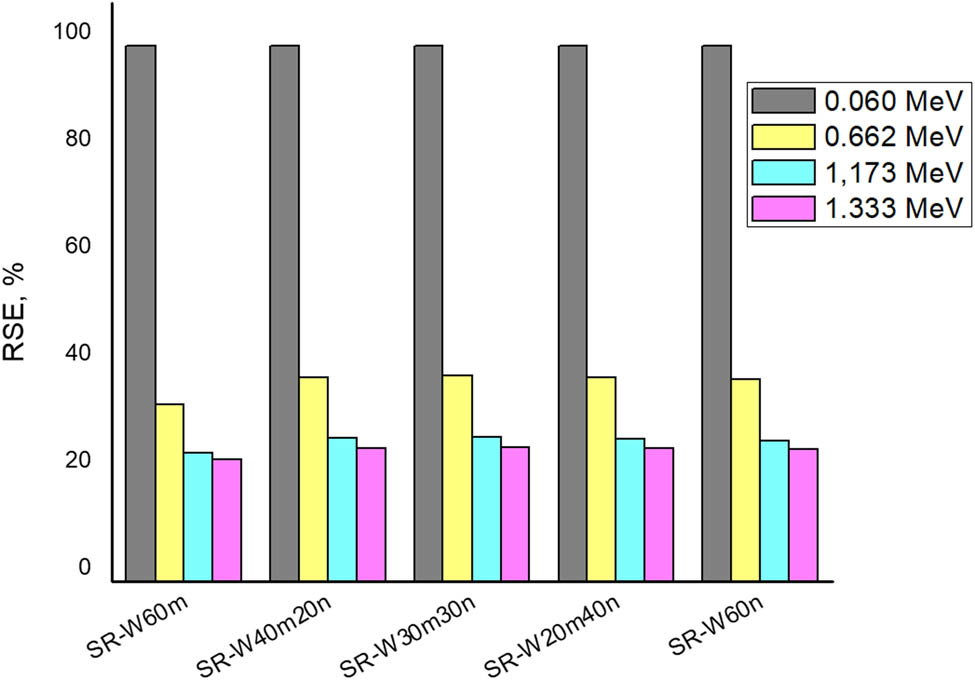

We evaluated the RSE for the prepared composites with a thickness of 2 cm and the findings are shown in Figure 8. Apparently, the higher RSE (corresponds to smaller transmission of photons) occurs at 0.06 MeV. It is about 100% for all composites, indicating that these prepared SR with WO3 can stop all the incoming radiation with low energy (particularly with energy of 0.06 MeV). As the energy reached 0.662 MeV, we found a significant decrease in the RSE. This reduction in RSE implies a substantial influx of radiation with energy of 0.662 MeV that can penetrate the prepared SR with different WO3 contents. For instance, the RSE for SR-(WO3)40m20n at 0.662 MeV is 38.12%. This means that if a beam of photons with energy of 0.662 MEV interacts with SR-(WO3)40m20n sample, only 38.12% of the photons are successfully absorbed or stopped, whereas the remaining 61.88% can pass through this sample. At 1.333 MeV, the lowest RSE is observed, which means that the prepared composites have weak attenuation ability at higher energy levels.

The RSE of SR composite as a function of photon energy.

In Table 2, we compared the MFP of SR-(WO3)40m20n, SR-(WO3)30m30n, and SR-(WO3)20m40n with five other samples (SR-BT40 and SR-BT50 (41) as well as S-2, S-3, and S-4 (42), which are different SR TeO2 composites as follows: SR-BT40 is composite with 50% per weight SR, 10% B2O3 and 40%; SR-BT50 is composite with 40% SR, 10% B2O3 and 50%; S-2 refers to 60% SR and 40% WO3-NPs; S-3 represents a mixing of 60% SR and 40% BaO-NPs; and S-4 represents a mixing of 60% SR, 20% BaO-NPs, and 20% WO3-NPs. At 0.06 MeV, among the given composites, SR-BT50 has the highest LAC (6.49 cm−1), implying its efficiency in shielding the photons. This is followed by S-3 (5.83 cm−1) and SR-W30m30n (5.72 cm−1), which illustrate good shielding performance. Moreover, S-2 (2.52 cm−1) has the smallest LAC value, implying relatively weaker radiation shielding. S-4 (4.24 cm−1) and SR-(WO3)40m20n (5.59 cm−1) lie within the mid-range in terms of protection efficiency. SR-(WO3)40m20n (5.59 cm−1) lies between the lower and higher LAC values of the given composites, positioning it as a moderately efficient shield. At 0.662 MeV, we found that SR-W30m30n has the highest LAC (0.242 cm−1), denoting its good performance in terms of radiation shielding at 0.662 MeV. This confirms that SR-(WO3)40m20n is especially well-suited for applications necessitating robust radiation protection. SR-(WO3)40m20n has a close LAC with SR-(WO3)30m30n, demonstrating its good ability to shield the radiation. Also, SR-W20m40n shows an LAC value of 0.239 cm−1, indicating its good attenuation features. The comparison at other energies is clear in Table 2.

Comparison of present work with other published works

| Codes | LAC | HVL | MFP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.060 MeV | 0.662 MeV | 1.333 MeV | 0.060 MeV | 0.662 MeV | 1.333 MeV | 0.060 MeV | 0.662 MeV | 1.333 MeV | |

| SR-BT40 | 5.0424 | 0.1637 | 0.1141 | 0.1375 | 4.2348 | 6.0733 | 0.1983 | 6.1095 | 8.7619 |

| SR-BT50 | 6.4890 | 0.1703 | 0.1220 | 0.1068 | 4.0713 | 5.6825 | 0.1541 | 5.8737 | 8.1981 |

| S-2 | 2.5163 | 0.1589 | 0.1034 | 0.2755 | 4.3631 | 6.7039 | 0.3974 | 6.2947 | 9.6717 |

| S-3 | 5.8280 | 0.1425 | 0.0970 | 0.1189 | 4.8641 | 7.1467 | 0.1716 | 7.0174 | 10.3105 |

| S-4 | 4.2366 | 0.1504 | 0.1001 | 0.1636 | 4.6081 | 6.9279 | 0.2360 | 6.6481 | 9.9948 |

| SR-(WO3)40m20n | 5.5877 | 0.2400 | 0.1431 | 0.1240 | 2.8881 | 4.8437 | 0.1790 | 4.1667 | 6.9880 |

| SR-(WO3)30m30n | 5.7245 | 0.2423 | 0.1443 | 0.1211 | 2.8610 | 4.8020 | 0.1747 | 4.1275 | 6.9278 |

| SR-(WO3)20m40n | 5.5935 | 0.2399 | 0.1430 | 0.1239 | 2.8893 | 4.8481 | 0.1788 | 4.1684 | 6.9944 |

4 Conclusion

In this research, the variation in the size of WO3 particles inside SR and its effect on the efficiency of the material as a shield for ionizing radiation was studied. The LAC for these composites was measured in the range of 0.06–1.333 MeV. The existence of micro and nanoparticles together may result in enhanced interactions with incoming photons, leading to greater shielding. In other words, micro-WO3 and nano-WO3 have various sizes and surface areas. At 0.060 MeV, we notice a distinguished decrease in the HVL from SR-(WO3)60m to SR-(WO3)60n. The sequence of reducing HVL values ((SR-(WO3)60m > SR-(WO3)60n > SR-(WO3)40m20n > SR-(WO3)20m40n > SR-(WO3)30m30n)) suggest that the inclusion of both micro and nano-WO3 contributes to more efficient radiation shielding compared to the reference material. The RSE for SR-(WO3)30m30n at 0.662 MeV is 38.40%. This means that if a beam of photons with energy of 0.662 MEV interacts with SR-(WO3)30m30n sample, only 38.40% of the photons are successfully absorbed or stopped, whereas the remaining 61.18% can pass through this sample. At 1.333 MeV, the lowest RSE is observed, which means that the prepared composites have weak attenuation ability at higher energy levels. The current composites were compared with other flexible composites and good and effective results were obtained.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University researchers supporting Project number (PNURSP2023R57), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Funding information: The authors express their gratitude to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University researchers supporting Project number (PNURSP2023R57), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Conflict of interest: There is no conflict of interest.

-

Ethics approval: Not applicable.

-

Consent to participate: Not applicable.

-

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

(1) Saleh A, Elshazly R, Abd Elghany H. The impact of CdO on the radiation shielding properties of zinc-sodium-phosphate glass containing barium. Arab J Nucl Sci Appl. 2022;55(1):116–26.10.21608/ajnsa.2021.80370.1478Search in Google Scholar

(2) Saleh A, Shalaby RM, Abdelhakim NA. Comprehensive study on structure, mechanical and nuclear shielding properties of lead free Sn–Zn–Bi alloys as a powerful radiation and neutron shielding material. Radiat Phys Chem. 2022;195:110065.10.1016/j.radphyschem.2022.110065Search in Google Scholar

(3) Saleh A, El-Feky MG, Hafiz MS, Kawady NA. Experimental and theoretical investigation on physical, structure and protection features of TeO2-B2O3 glass doped with PbO in terms of gamma, neutron, proton and alpha particles. Radiat Phys Chem. 2022;202:110586.10.1016/j.radphyschem.2022.110586Search in Google Scholar

(4) Bagheri R, Moghaddam AK, Yousefnia H. Gamma ray shielding study of barium-bismuth-borosilicate glasses as transparent shielding materials using MCNP-4C Code, XCOM program, and available experimental data. Nucl Eng Technol. 2017;49:216–23.10.1016/j.net.2016.08.013Search in Google Scholar

(5) Zubair M, Ahmed E, Hartanto D. Comparison of different glass materials to protect the operators from gamma-rays in the PET using MCNP code. Radiat Phys Chem. 2022;190:109818.10.1016/j.radphyschem.2021.109818Search in Google Scholar

(6) Naseer KA, Marimuthu K, Mahmoud KA, Sayyed MI. Impact of Bi2O3 modifier concentration on barium–zincborate glasses: physical, structural, elastic, and radiation-shielding properties. Eur Phys J Plus. 2021;136:116.10.1140/epjp/s13360-020-01056-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(7) Karabul Y, İçelli O. The assessment of usage of epoxy based micro and nano-structured composites enriched with Bi2O3 and WO3 particles for radiation shielding. Res Phys. 2021;26:104423.10.1016/j.rinp.2021.104423Search in Google Scholar

(8) Alorain DA, Almuqrin AH, Sayyed MI, Elsafi M. Impact of WO3 and BaO nanoparticles on the radiation shielding characteristics of polydimethylsiloxane composites. e-Polymers. 2023;23(1):20230037. 10.1515/epoly-2023-0037.Search in Google Scholar

(9) Aygün B. High alloyed new stainless steel shielding material for gamma and fast neutron radiation. Nucl Eng Technol. 2020;52:647–53.10.1016/j.net.2019.08.017Search in Google Scholar

(10) Aygün B. Neutron and gamma radiation shielding Ni based new type super alloys development and production by Monte Carlo simulation technique. Radiat Phys Chem. 2021;188:109630.10.1016/j.radphyschem.2021.109630Search in Google Scholar

(11) Şahin N, Bozkurt M, Karabul Y, Kılıç M, Özdemir ZG. Low cost radiation shielding material for low energy radiation applications: Epoxy/Yahyali Stone composites. Prog Nucl Energy. 2021;135:103703.10.1016/j.pnucene.2021.103703Search in Google Scholar

(12) Korkut T, Umaç ZI, Aygün B, Karabulut A, Yapıcı S, Şahin R. Neutron equivalent dose rate measurements of gypsum-waste tire rubber layered structures. Int J Polym Anal Charact. 2013;18(6):423–9.10.1080/1023666X.2013.814025Search in Google Scholar

(13) Yasmin S, Almousa N, Abualsayed MI, Elsafi M. Grafting of heavy metal oxides onto pure polyester for the interest of enhancing radiation shielding performance. Radiochimica Acta. 2023;111(6):495–502. 10.1515/ract-2023-0001.Search in Google Scholar

(14) Almuqrin AH, Yasmin S, Abualsayed MI, Elsafi M. An experimental investigation into the radiation-shielding performance of newly developed polyester containing recycled waste marble and bismuth oxide. Appl Rheol. 2023;33(1):20220153. 10.1515/arh-2022-0153.Search in Google Scholar

(15) Özdemir T, Güngör A, Akbay IK, Uzun H, Babucçuoglu Y. Nano lead oxide and epdm composite for development of polymer based radiation shielding material: Gamma irradiation and attenuation tests. Radiat Phys Chem. 2018;144:248–55.10.1016/j.radphyschem.2017.08.021Search in Google Scholar

(16) Kim S, Ahn Y, Song SH, Lee D. Tungsten nanoparticle anchoring on boron nitride nanosheet-based polymer nanocomposites for complex radiation shielding. Compos Sci Technol. 2022;221:109353.10.1016/j.compscitech.2022.109353Search in Google Scholar

(17) Sayyed MI, Al-Ghamdi H, Almuqrin AH, Yasmin S, Elsafi M. A study on the gamma radiation protection effectiveness of nano/micro-MgO-reinforced novel silicon rubber for medical applications. Polymers. 2022;14:2867.10.3390/polym14142867Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(18) Zali VS, Jahanbakhsh O, Ahadzadeh I. Preparation and evaluation of gamma shielding properties of silicon-based composites doped with WO3 micro- and nanoparticles. Radiat Phys Chem. 2022;197:110150.10.1016/j.radphyschem.2022.110150Search in Google Scholar

(19) Eyssa HM, Sadek RF, Mohamed WS, Ramadan W. Structure-property behavior of polyethylene nanocomposites containing Bi2O3 and WO3 as an eco-friendly additive for radiation shielding. Ceram Int. 2023;49:18442–54.10.1016/j.ceramint.2023.02.216Search in Google Scholar

(20) Elsafi M, Almousa N, Al-Harbi N, Almutiri MN, Yasmin S, Sayyed MI. Ecofriendly and radiation shielding properties of newly developed epoxy with waste marble and WO3 nanoparticles. J Mater Res Technol. 2023;22:269–77.Search in Google Scholar

(21) Al-Saleh WM, Dahi MR, Sayyed MI, Almutairi HM, Saleh IH, Elsafi M. Comprehensive study of the radiation shielding feature of polyester polymers impregnated with iron filings. e-Polymers. 2023;23(1): 20230096. 10.1515/epoly-2023-0096.Search in Google Scholar

(22) Alhindawy IG, Sayyed MI, Almuqrin AH, Mahmoud KA. Optimizing gamma radiation shielding with cobalt-titania hybrid nanomaterials. Sci Rep. 2023;13:8936.10.1038/s41598-023-33864-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(23) Elsafi M, Almuqrin AH, Almutairi HM, Al-Saleh WM, Sayyed MI. Grafting red clay with Bi2O3 nanoparticles into epoxy resin for gamma-ray shielding applications. Sci Rep. 2023;13:5472.10.1038/s41598-023-32522-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(24) Elsafi M, Almuqrin AH, Yasmin S, Sayyed MI. The affinity of bentonite and WO3 nanoparticles toward epoxy resin polymer for radiation shielding. e-Polymers. 2023;23(1):20230011. 10.1515/epoly-2023-0011.Search in Google Scholar

(25) Al-Ghamdi H, Hemily HM, Saleh IH, Ghataas ZF, Abdel-Halim AA, Sayyed MI, et al. Impact of WO3-nanoparticles on silicone rubber for radiation protection efficiency. Materials. 2022;15:5706. 10.3390/ma15165706.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(26) Al-Ghamdi H, Elsafi M, Almuqrin AH, Yasmin S, Sayyed MI. Investigation of the gamma-ray shielding performance of CuO-CdO-Bi2O3 bentonite ceramics. Materials. 2022;15(15):5310.10.3390/ma15155310Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(27) Al-Ghamdi H, El-Nahal MA, Saleh IH, Sayyed MI, Almuqrin AH. Determination of 238U and 40K radionuclide concentrations in some granite rocks by gamma spectroscopy and energy dispersive x-ray analysis. Materials. 2022;15(15):5130.10.3390/ma15155130Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(28) Sayyed MI, Yasmin S, Almousa N, Elsafi M. The Radiation Shielding Performance of Polyester with TeO2 and B2O3. Processes. 2022;10(9):1725.10.3390/pr10091725Search in Google Scholar

(29) Sayyed MI, Hashim S, Hannachi E, Slimani Y, Elsafi M. Effect of WO3 nanoparticles on the radiative attenuation properties of SrTiO3 perovskite ceramic. Crystals. 2022;12(11):1602.10.3390/cryst12111602Search in Google Scholar

(30) Sayyed MI, Almurayshid M, Almasoud FI, Yasmin S, Elsafi M. Developed a new radiation shielding absorber composed of waste marble, polyester, PbCO3, and CdO to reduce waste marble considering environmental safety. Materials. 2022;15(23):8371.10.3390/ma15238371Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(31) Aloraini DA, Elsafi M, Almuqrin AH, Sayyed MI. Coincidence summing factor calculation for volumetric γ-ray sources using Geant4 simulation. Sci Technol Nucl Install. 2022;2022:5718920.10.1155/2022/5718920Search in Google Scholar

(32) D’Souza AN, Padasale B, Murari MS, Almuqrin AH, Kamath SD. TeO2 for enhancing structural, mechanical, optical, gamma and neutron radiation shielding performance of bismuth borosilicate glasses. Mater Chem Phys. 2023;293:126657.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2022.126657Search in Google Scholar

(33) Hannachi E, Sayyed MI, Slimani Y, Elsafi M. Structural, optical and radiation shielding peculiarities of strontium titanate ceramics mixed with tungsten nanowires: An experimental study. Opt Mater. 2023;135:113317.10.1016/j.optmat.2022.113317Search in Google Scholar

(34) Elsafi M, Almousa N, Al-Harbi N, Yasmin S, Sayyed MI. Ecofriendly and radiation shielding properties of newly developed epoxy with waste marble and WO3 nanoparticles. J Mater Res Technol. 2023;22:269–77.10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.11.128Search in Google Scholar

(35) Hannachi E, Sayyed MI, Slimani Y, Baykal A, Elsafi M. Structure and radiation-shielding characteristics of BTO/MnZnFeO ceramic composites. J Phys Chem Solids. 2023;174:111132.10.1016/j.jpcs.2022.111132Search in Google Scholar

(36) Elsafi M, Al-Ghamdi H, Sayyed MI, Shalaby TI, El-Khatib AM. Optimizing the gamma-ray shielding behaviors for polypropylene using lead oxide: A detailed examination. J Mater Res Technol. 2022;19:1862–72.10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.05.128Search in Google Scholar

(37) Sayyed MI, Almousa N, Elsafi M. Green conversion of the hazardous cathode ray tube and red mud into radiation shielding concrete. Materials. 2022;15(15):5316.10.3390/ma15155316Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(38) Almuqrin AH, Elsafi M, Yasmin S, Sayyed MI. Morphological and gamma-ray attenuation properties of high-density polyethylene containing bismuth oxide. Materials. 2022;15(18):6410.10.3390/ma15186410Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Chitosan nanocomposite film incorporating Nigella sativa oil, Azadirachta indica leaves’ extract, and silver nanoparticles

- Effect of Zr-doped CaCu3Ti3.95Zr0.05O12 ceramic on the microstructure, dielectric properties, and electric field distribution of the LDPE composites

- Effects of dry heating, acetylation, and acid pre-treatments on modification of potato starch with octenyl succinic anhydride (OSA)

- Loading conditions impact on the compression fatigue behavior of filled styrene butadiene rubber

- Characterization and compatibility of bio-based PA56/PET

- Study on the aging of three typical rubber materials under high- and low-temperature cyclic environment

- Numerical simulation and experimental research of electrospun polyacrylonitrile Taylor cone based on multiphysics coupling

- Experimental investigation of properties and aging behavior of pineapple and sisal leaf hybrid fiber-reinforced polymer composites

- Influence of temperature distribution on the foaming quality of foamed polypropylene composites

- Enzyme-catalyzed synthesis of 4-methylcatechol oligomer and preliminary evaluations as stabilizing agent in polypropylene

- Molecular dynamics simulation of the effect of the thermal and mechanical properties of addition liquid silicone rubber modified by carbon nanotubes with different radii

- Incorporation of poly(3-acrylamidopropyl trimethylammonium chloride-co-acrylic acid) branches for good sizing properties and easy desizing from sized cotton warps

- Effect of matrix composition on properties of polyamide 66/polyamide 6I-6T composites with high content of continuous glass fiber for optimizing surface performance

- Preparation and properties of epoxy-modified thermosetting phenolic fiber

- Thermal decomposition reaction kinetics and storage life prediction of polyacrylate pressure-sensitive adhesive

- Effect of different proportions of CNTs/Fe3O4 hybrid filler on the morphological, electrical and electromagnetic interference shielding properties of poly(lactic acid) nanocomposites

- Doping silver nanoparticles into reverse osmosis membranes for antibacterial properties

- Melt-blended PLA/curcumin-cross-linked polyurethane film for enhanced UV-shielding ability

- The affinity of bentonite and WO3 nanoparticles toward epoxy resin polymer for radiation shielding

- Prolonged action fertilizer encapsulated by CMC/humic acid

- Preparation and experimental estimation of radiation shielding properties of novel epoxy reinforced with Sb2O3 and PbO

- Fabrication of polylactic acid nanofibrous yarns for piezoelectric fabrics

- Copper phenyl phosphonate for epoxy resin and cyanate ester copolymer with improved flame retardancy and thermal properties

- Synergistic effect of thermal oxygen and UV aging on natural rubber

- Effect of zinc oxide suspension on the overall filler content of the PLA/ZnO composites and cPLA/ZnO composites

- The role of natural hybrid nanobentonite/nanocellulose in enhancing the water resistance properties of the biodegradable thermoplastic starch

- Performance optimization of geopolymer mortar blending in nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber based on set pair analysis

- Preparation of (La + Nb)-co-doped TiO2 and its polyvinylidene difluoride composites with high dielectric constants

- Effect of matrix composition on the performance of calcium carbonate filled poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composites

- Low-temperature self-healing polyurethane adhesives via dual synergetic crosslinking strategy

- Leucaena leucocephala oil-based poly malate-amide nanocomposite coating material for anticorrosive applications

- Preparation and properties of modified ammonium polyphosphate synergistic with tris(2-hydroxyethyl) isocynurate for flame-retardant LDPE

- Thermal response of double network hydrogels with varied composition

- The effect of coated calcium carbonate using stearic acid on the recovered carbon black masterbatch in low-density polyethylene composites

- Investigation of MXene-modified agar/polyurethane hydrogel elastomeric repair materials with tunable water absorption

- Damping performance analysis of carbon black/lead magnesium niobite/epoxy resin composites

- Molecular dynamics simulations of dihydroxylammonium 5,5′-bistetrazole-1,1′-diolate (TKX-50) and TKX-50-based PBXs with four energetic binders

- Preparation and characterization of sisal fibre reinforced sodium alginate gum composites for non-structural engineering applications

- Study on by-products synthesis of powder coating polyester resin catalyzed by organotin

- Ab initio molecular dynamics of insulating paper: Mechanism of insulating paper cellobiose cracking at transient high temperature

- Effect of different tin neodecanoate and calcium–zinc heat stabilizers on the thermal stability of PVC

- High-strength polyvinyl alcohol-based hydrogel by vermiculite and lignocellulosic nanofibrils for electronic sensing

- Impacts of micro-size PbO on the gamma-ray shielding performance of polyepoxide resin

- Influence of the molecular structure of phenylamine antioxidants on anti-migration and anti-aging behavior of high-performance nitrile rubber composites

- Fiber-reinforced polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel via in situ fiber formation

- Preparation and performance of homogenous braids-reinforced poly (p-phenylene terephthamide) hollow fiber membranes

- Synthesis of cadmium(ii) ion-imprinted composite membrane with a pyridine functional monomer and characterization of its adsorption performance

- Impact of WO3 and BaO nanoparticles on the radiation shielding characteristics of polydimethylsiloxane composites

- Comprehensive study of the radiation shielding feature of polyester polymers impregnated with iron filings

- Preparation and characterization of polymeric cross-linked hydrogel patch for topical delivery of gentamicin

- Mechanical properties of rCB-pigment masterbatch in rLDPE: The effect of processing aids and water absorption test

- Pineapple fruit residue-based nanofibre composites: Preparation and characterizations

- Effect of natural Indocalamus leaf addition on the mechanical properties of epoxy and epoxy-carbon fiber composites

- Utilization of biosilica for energy-saving tire compounds: Enhancing performance and efficiency

- Effect of capillary arrays on the profile of multi-layer micro-capillary films

- A numerical study on thermal bonding with preheating technique for polypropylene microfluidic device

- Development of modified h-BN/UPE resin for insulation varnish applications

- High strength, anti-static, thermal conductive glass fiber/epoxy composites for medical devices: A strategy of modifying fibers with functionalized carbon nanotubes

- Effects of mechanical recycling on the properties of glass fiber–reinforced polyamide 66 composites in automotive components

- Bentonite/hydroxyethylcellulose as eco-dielectrics with potential utilization in energy storage

- Study on wall-slipping mechanism of nano-injection polymer under the constant temperature fields

- Synthesis of low-VOC unsaturated polyester coatings for electrical insulation

- Enhanced apoptotic activity of Pluronic F127 polymer-encapsulated chlorogenic acid nanoparticles through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in liver cancer cells and in vivo toxicity studies in zebrafish

- Preparation and performance of silicone-modified 3D printing photosensitive materials

- A novel fabrication method of slippery lubricant-infused porous surface by thiol-ene click chemistry reaction for anti-fouling and anti-corrosion applications

- Development of polymeric IPN hydrogels by free radical polymerization technique for extended release of letrozole: Characterization and toxicity evaluation

- Tribological characterization of sponge gourd outer skin fiber-reinforced epoxy composite with Tamarindus indica seed filler addition using the Box–Behnken method

- Stereocomplex PLLA–PBAT copolymer and its composites with multi-walled carbon nanotubes for electrostatic dissipative application

- Enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of Krestin–chitosan nanocomplex for cancer medication via activation of the mitochondrial intrinsic pathway

- Variation in tungsten(vi) oxide particle size for enhancing the radiation shielding ability of silicone rubber composites

- Damage accumulation and failure mechanism of glass/epoxy composite laminates subjected to repeated low velocity impacts

- Gamma-ray shielding analysis using the experimental measurements for copper(ii) sulfate-doped polyepoxide resins

- Numerical simulation into influence of airflow channel quantities on melt-blowing airflow field in processing of polymer fiber

- Cellulose acetate oleate-reinforced poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composite materials

- Radiation shielding capability and exposure buildup factor of cerium(iv) oxide-reinforced polyester resins

- Recyclable polytriazole resins with high performance based on Diels-Alder dynamic covalent crosslinking

- Adsorption and recovery of Cr(vi) from wastewater by Chitosan–Urushiol composite nanofiber membrane

- Comprehensive performance evaluation based on electromagnetic shielding properties of the weft-knitted fabrics made by stainless steel/cotton blended yarn

- Review Articles

- Preparation and application of natural protein polymer-based Pickering emulsions

- Wood-derived high-performance cellulose structural materials

- Flammability properties of polymers and polymer composites combined with ionic liquids

- Polymer-based nanocarriers for biomedical and environmental applications

- A review on semi-crystalline polymer bead foams from stirring autoclave: Processing and properties

- Rapid Communication

- Preparation and characterization of magnetic microgels with linear thermosensitivity over a wide temperature range

- Special Issue: Biodegradable and bio-based polymers: Green approaches (Guest Editors: Kumaran Subramanian, A. Wilson Santhosh Kumar, and Venkatajothi Ramarao)

- Synthesis and characterization of proton-conducting membranes based on bacterial cellulose and human nail keratin

- Fatigue behaviour of Kevlar/carbon/basalt fibre-reinforced SiC nanofiller particulate hybrid epoxy composite

- Effect of citric acid on thermal, phase morphological, and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactide)-b-poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(l-lactide)/thermoplastic starch blends

- Dose-dependent cytotoxicity against lung cancer cells via green synthesized ZnFe2O4/cellulose nanocomposites

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Chitosan nanocomposite film incorporating Nigella sativa oil, Azadirachta indica leaves’ extract, and silver nanoparticles

- Effect of Zr-doped CaCu3Ti3.95Zr0.05O12 ceramic on the microstructure, dielectric properties, and electric field distribution of the LDPE composites

- Effects of dry heating, acetylation, and acid pre-treatments on modification of potato starch with octenyl succinic anhydride (OSA)

- Loading conditions impact on the compression fatigue behavior of filled styrene butadiene rubber

- Characterization and compatibility of bio-based PA56/PET

- Study on the aging of three typical rubber materials under high- and low-temperature cyclic environment

- Numerical simulation and experimental research of electrospun polyacrylonitrile Taylor cone based on multiphysics coupling

- Experimental investigation of properties and aging behavior of pineapple and sisal leaf hybrid fiber-reinforced polymer composites

- Influence of temperature distribution on the foaming quality of foamed polypropylene composites

- Enzyme-catalyzed synthesis of 4-methylcatechol oligomer and preliminary evaluations as stabilizing agent in polypropylene

- Molecular dynamics simulation of the effect of the thermal and mechanical properties of addition liquid silicone rubber modified by carbon nanotubes with different radii

- Incorporation of poly(3-acrylamidopropyl trimethylammonium chloride-co-acrylic acid) branches for good sizing properties and easy desizing from sized cotton warps

- Effect of matrix composition on properties of polyamide 66/polyamide 6I-6T composites with high content of continuous glass fiber for optimizing surface performance

- Preparation and properties of epoxy-modified thermosetting phenolic fiber

- Thermal decomposition reaction kinetics and storage life prediction of polyacrylate pressure-sensitive adhesive

- Effect of different proportions of CNTs/Fe3O4 hybrid filler on the morphological, electrical and electromagnetic interference shielding properties of poly(lactic acid) nanocomposites

- Doping silver nanoparticles into reverse osmosis membranes for antibacterial properties

- Melt-blended PLA/curcumin-cross-linked polyurethane film for enhanced UV-shielding ability

- The affinity of bentonite and WO3 nanoparticles toward epoxy resin polymer for radiation shielding

- Prolonged action fertilizer encapsulated by CMC/humic acid

- Preparation and experimental estimation of radiation shielding properties of novel epoxy reinforced with Sb2O3 and PbO

- Fabrication of polylactic acid nanofibrous yarns for piezoelectric fabrics

- Copper phenyl phosphonate for epoxy resin and cyanate ester copolymer with improved flame retardancy and thermal properties

- Synergistic effect of thermal oxygen and UV aging on natural rubber

- Effect of zinc oxide suspension on the overall filler content of the PLA/ZnO composites and cPLA/ZnO composites

- The role of natural hybrid nanobentonite/nanocellulose in enhancing the water resistance properties of the biodegradable thermoplastic starch

- Performance optimization of geopolymer mortar blending in nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber based on set pair analysis

- Preparation of (La + Nb)-co-doped TiO2 and its polyvinylidene difluoride composites with high dielectric constants

- Effect of matrix composition on the performance of calcium carbonate filled poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composites

- Low-temperature self-healing polyurethane adhesives via dual synergetic crosslinking strategy

- Leucaena leucocephala oil-based poly malate-amide nanocomposite coating material for anticorrosive applications

- Preparation and properties of modified ammonium polyphosphate synergistic with tris(2-hydroxyethyl) isocynurate for flame-retardant LDPE

- Thermal response of double network hydrogels with varied composition

- The effect of coated calcium carbonate using stearic acid on the recovered carbon black masterbatch in low-density polyethylene composites

- Investigation of MXene-modified agar/polyurethane hydrogel elastomeric repair materials with tunable water absorption

- Damping performance analysis of carbon black/lead magnesium niobite/epoxy resin composites

- Molecular dynamics simulations of dihydroxylammonium 5,5′-bistetrazole-1,1′-diolate (TKX-50) and TKX-50-based PBXs with four energetic binders

- Preparation and characterization of sisal fibre reinforced sodium alginate gum composites for non-structural engineering applications

- Study on by-products synthesis of powder coating polyester resin catalyzed by organotin

- Ab initio molecular dynamics of insulating paper: Mechanism of insulating paper cellobiose cracking at transient high temperature

- Effect of different tin neodecanoate and calcium–zinc heat stabilizers on the thermal stability of PVC

- High-strength polyvinyl alcohol-based hydrogel by vermiculite and lignocellulosic nanofibrils for electronic sensing

- Impacts of micro-size PbO on the gamma-ray shielding performance of polyepoxide resin

- Influence of the molecular structure of phenylamine antioxidants on anti-migration and anti-aging behavior of high-performance nitrile rubber composites

- Fiber-reinforced polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel via in situ fiber formation

- Preparation and performance of homogenous braids-reinforced poly (p-phenylene terephthamide) hollow fiber membranes

- Synthesis of cadmium(ii) ion-imprinted composite membrane with a pyridine functional monomer and characterization of its adsorption performance

- Impact of WO3 and BaO nanoparticles on the radiation shielding characteristics of polydimethylsiloxane composites

- Comprehensive study of the radiation shielding feature of polyester polymers impregnated with iron filings

- Preparation and characterization of polymeric cross-linked hydrogel patch for topical delivery of gentamicin

- Mechanical properties of rCB-pigment masterbatch in rLDPE: The effect of processing aids and water absorption test

- Pineapple fruit residue-based nanofibre composites: Preparation and characterizations

- Effect of natural Indocalamus leaf addition on the mechanical properties of epoxy and epoxy-carbon fiber composites

- Utilization of biosilica for energy-saving tire compounds: Enhancing performance and efficiency

- Effect of capillary arrays on the profile of multi-layer micro-capillary films

- A numerical study on thermal bonding with preheating technique for polypropylene microfluidic device

- Development of modified h-BN/UPE resin for insulation varnish applications

- High strength, anti-static, thermal conductive glass fiber/epoxy composites for medical devices: A strategy of modifying fibers with functionalized carbon nanotubes

- Effects of mechanical recycling on the properties of glass fiber–reinforced polyamide 66 composites in automotive components

- Bentonite/hydroxyethylcellulose as eco-dielectrics with potential utilization in energy storage

- Study on wall-slipping mechanism of nano-injection polymer under the constant temperature fields

- Synthesis of low-VOC unsaturated polyester coatings for electrical insulation

- Enhanced apoptotic activity of Pluronic F127 polymer-encapsulated chlorogenic acid nanoparticles through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in liver cancer cells and in vivo toxicity studies in zebrafish

- Preparation and performance of silicone-modified 3D printing photosensitive materials

- A novel fabrication method of slippery lubricant-infused porous surface by thiol-ene click chemistry reaction for anti-fouling and anti-corrosion applications

- Development of polymeric IPN hydrogels by free radical polymerization technique for extended release of letrozole: Characterization and toxicity evaluation

- Tribological characterization of sponge gourd outer skin fiber-reinforced epoxy composite with Tamarindus indica seed filler addition using the Box–Behnken method

- Stereocomplex PLLA–PBAT copolymer and its composites with multi-walled carbon nanotubes for electrostatic dissipative application

- Enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of Krestin–chitosan nanocomplex for cancer medication via activation of the mitochondrial intrinsic pathway

- Variation in tungsten(vi) oxide particle size for enhancing the radiation shielding ability of silicone rubber composites

- Damage accumulation and failure mechanism of glass/epoxy composite laminates subjected to repeated low velocity impacts

- Gamma-ray shielding analysis using the experimental measurements for copper(ii) sulfate-doped polyepoxide resins

- Numerical simulation into influence of airflow channel quantities on melt-blowing airflow field in processing of polymer fiber

- Cellulose acetate oleate-reinforced poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composite materials

- Radiation shielding capability and exposure buildup factor of cerium(iv) oxide-reinforced polyester resins

- Recyclable polytriazole resins with high performance based on Diels-Alder dynamic covalent crosslinking

- Adsorption and recovery of Cr(vi) from wastewater by Chitosan–Urushiol composite nanofiber membrane

- Comprehensive performance evaluation based on electromagnetic shielding properties of the weft-knitted fabrics made by stainless steel/cotton blended yarn

- Review Articles

- Preparation and application of natural protein polymer-based Pickering emulsions

- Wood-derived high-performance cellulose structural materials

- Flammability properties of polymers and polymer composites combined with ionic liquids

- Polymer-based nanocarriers for biomedical and environmental applications

- A review on semi-crystalline polymer bead foams from stirring autoclave: Processing and properties

- Rapid Communication

- Preparation and characterization of magnetic microgels with linear thermosensitivity over a wide temperature range

- Special Issue: Biodegradable and bio-based polymers: Green approaches (Guest Editors: Kumaran Subramanian, A. Wilson Santhosh Kumar, and Venkatajothi Ramarao)

- Synthesis and characterization of proton-conducting membranes based on bacterial cellulose and human nail keratin

- Fatigue behaviour of Kevlar/carbon/basalt fibre-reinforced SiC nanofiller particulate hybrid epoxy composite

- Effect of citric acid on thermal, phase morphological, and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactide)-b-poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(l-lactide)/thermoplastic starch blends

- Dose-dependent cytotoxicity against lung cancer cells via green synthesized ZnFe2O4/cellulose nanocomposites