Association between preventable risk factors and metabolic syndrome

-

Hamoud A. Al Shehri

, Haseeb A. Khan

Abstract

The risk factors associated with metabolic syndrome (Met-S) including hypertension, hyperglycemia, central obesity, and dyslipidemia are preventable, particularly at their early stage. There are limited data available on the association between Met-S and preventable risk factors in young adults. We randomly selected 2,010 Saudis aged 18–30 years, who applied to be recruited in military colleges. All the procedures followed the guidelines of International Diabetes Federation. The results showed that out of 2,010 subjects, 4088 were affected with Met-S. The commonest risk factors were high blood sugar (63.6%), high systolic and diastolic blood pressures (63.3 and 37.3%), and high body mass index (57.5%). The prevalence of prediabetes and diabetes were 55.2 and 8.4%, respectively. Obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and hypertriglyceridemia were significantly associated with Met-S. The frequency of smoking was significantly linked with the development of Met-S. The prevalence of Met-S was found to be significantly higher in individuals with sedentary lifestyle. In conclusion, the results of this study clearly indicate that military recruits, who represent healthy young adults, are also prone to Met-S. The findings of this study will help in designing preventive measures as well as public awareness programs for controlling the high prevalence of Met-S in young adults.

1 Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (Met-S) is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) [1] and type-2 diabetes [2]. This syndrome is defined as a cluster of risk factors that typically include central obesity, elevated blood pressure (BP), impaired glucose metabolism, and dyslipidemia. In recent decades, marked socioeconomic developments in health, education, environment, and lifestyle in many developed countries have led to a decrease in communicable diseases, but an increase in chronic diseases of lifestyle, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and other risk factors of CVD [3]. There are multiple risk factors associated with CVD such as behavioral factors (smoking, diet, physical activity [PA], alcohol consumption), physiological factors (blood cholesterol, hypertension, blood glucose, body mass index [BMI]), and metabolic disorders [4]. However, inadequate nutrient intake and low socioeconomic status are also linked with an elevated CVD risk [5,6].

Although the primary manifestations of CVD are common in older adults, they have also been detected in young adulthood [7,8]. Therefore, it is important to identify CVD risk factors in young persons with metabolic abnormalities with high risk of progression, as almost 50% of middle-aged men have abnormal glucose tolerance [9]. The obesity risk factors, such as unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, and sedentary behavior have been observed among adolescents; however, the association of these factors with obesity is not yet completely characterized [10,11]. Adolescents performing vigorous PA tend to consume a healthier diet and fewer unhealthy food items [11,12]. Healthy diet, active lifestyle as well as better cardiorespiratory fitness in adolescence have been associated with a reduced risk of CVD [13,14]. Lifestyle interventions including dietary modifications and increased PA play a significant role in the treatment of the obesity and related disorders such as impaired glucose intolerance, type 2-diabetes, and hyperlipidemia [9,11]. Increased PA in the intervention studies has resulted in beneficial changes in body composition, by reducing the amount of total and visceral fats, without a significant weight loss [9,11]. Many adolescents do not meet the health-related recommendations for sufficient PA, and the decline in PA has been observed from adolescence to young adulthood [15].

In fact, by identifying persons at risk of developing CVD and supplying early health counseling and lifestyle interventions, it could be possible to prevent later detrimental cardio-metabolic diseases. The unhealthy change in dietary habits, a sedentary lifestyle, and consanguineous marriages make the young Saudi population vulnerable to Met-S. The influence of diet, PA, and BMI on the body composition of adolescents and young adults has been studied previously [8,9,11]. However, there are limited data about the role of preventable risk factors for the development of Met-S in young adults, particularly in military personnel. Therefore, we investigated the status of Met-S in young Saudis enrolled for military recruitment. We specifically studied the association between Met-S and preventable risk factors including the body weight, PA, smoking, and dietary habits.

2 Materials and methods

This study was conducted on a total of 2,010 young Saudi men, aged 18–30 years, who applied for recruitment to Saudi armed forces. The study was carried out at the health facility of the selection centers and all the selected participants individually completed a consent form. Standardized medical observations included physical examination as well as measurements related to Met-S including BP, height, body weight, and blood biochemistry (blood glucose and lipid profile). The complete information of each participant was filled in a specially designed questionnaire based on the guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO) [3]. The study protocol was approved (REC/523, dated 21/03/2017) by Institutional Ethical Committee.

According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) definition, subjects were considered to have Met-S if they had central obesity (defined as waist circumference >94 cm), plus two of the following four factors. Raised fasting plasma glucose >100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L), or previously diagnosed type-2 diabetes; systolic BP >130 mm Hg or diastolic BP >85 mm Hg, or treatment of previously diagnosed hypertension; high density lipoproteins (HDL) <40 mg/dL (1.0 mmol/L) or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality; and triglycerides (TGs) level >150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L) or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality.

Prehypertension was defined as systolic BP 120–139 mm Hg or diastolic BP 80–89 mm Hg. Hypertension was defined as systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg [16]. BMI was classified according to the WHO adult BMI classification as normal (18.50–24.99 kg/m2), overweight (≥25–29.99 kg/m2), and obese (≥30 kg/m2) (Global Database on Body Mass Index: BMI classification [3]).

Blood samples from each recruitment center were transported to Prince Sultan Military Medical City for biochemical analysis. Blood samples were centrifuged at 1,500×g for 15 min, at 4°C, and sera were stored for analysis. Fasting blood sugar (FBS), total cholesterol, HDL, and TGs were analyzed using a Hitachi 902 autoanalyzer (Roche, Mannheim, Germany).

The data were analyzed by using the statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) statistical package version 14 (SPSS Chicago, IL). Mean and standard deviation were calculated for parametric data, whereas categorical data were represented by number and percentage. The chi-square test and student t-test were used for comparison between the Met-S and without Met-S groups. Analysis of covariance with age-adjusted means was used to evaluate the association between Met-S component factors and different parameters. A two-tailed P value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Association between demography and Met-S

The impact of demographic characteristics including age, education, marital status, and monthly income on the development of Met-S is shown in Table 1. There was a direct association between age and Met-S. Younger subjects had significantly less frequency of Met-S as compared to older subjects (P < 0.001). The prevalence of Met-S was higher in subjects with primary education than those with secondary education (P < 0.001). Married subjects showed high frequency of Met-S as compared to unmarried participants (P < 0.01). Subjects coming from large families (>15 members) had significantly higher prevalence of Met-S (P < 0.05). Monthly income did not show any association with Met-S (Table 1).

Association between Met-S and demographic characteristics

| Demographic characteristics | Met-S | Total, N | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤21 | 283 | 1,165 | 1,448 | 0.000 |

| 22–26 | 182 | 331 | 513 | |

| >26 | 23 | 26 | 49 | |

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | |

| Education (years of study) | ||||

| ≤14 | 287 | 1,183 | 1,470 | 0.000 |

| 15–19 | 199 | 334 | 533 | |

| >19 | 2 | 5 | 7 | |

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 31 | 46 | 77 | 0.003 |

| Single | 457 | 1,475 | 1,932 | |

| Divorced | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | |

| Members in family <18 years | ||||

| ≤5 | 287 | 972 | 1,259 | 0.039 |

| 6–10 | 153 | 435 | 588 | |

| 11–15 | 38 | 103 | 141 | |

| >15 | 10 | 12 | 22 | |

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | |

| Monthly income (Riyals) | ||||

| 10,000 | 246 | 731 | 977 | 0.761 |

| 11,000–20,000 | 195 | 648 | 843 | |

| >20,000 | 33 | 104 | 137 | |

| Refused to answer | 14 | 39 | 53 | |

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | |

3.2 Association between component factors and Met-S

We also analyzed the association between Met-S and the individual components that are used in the triplets of diagnosing Met-S. There was a direct relationship between bodyweight and Met-S. Individuals with the BMI <25 kg/m2 were free from Met-S, whereas overweight (40.26%) and obese (42.87%) subjects showed significantly high incidences of Met-S (Table 2). Subjects with hypertension also had significantly high (P < 0.001) frequency of Met-S as compared to subjects with normal BP. There was a direct association between FBS and Met-S. The prevalence of Met-S was highest in diabetic subjects (42.6%) followed by prediabetics (32.34%) as compared to subjects with normal FBS (7.79%; Figure 2). There was a direct correlation between TGs and Met-S, whereas an inverse correlation was observed between HDL and Met-S. Both these associations were statistically significant (P < 0.001) and of the same magnitude (Table 2).

Association between Met-S and its individual component factors in subjects using the common cut-off values

| Component factors | Met-S | Total, N | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| ≤18.4 (Underweight) | 0 | 574 | 574 | 0.000 |

| 18.5–24.9 (Normal weight) | 0 | 281 | 281 | |

| 25.0–29.9 (Overweight) | 91 | 135 | 226 | |

| ≥30.0 (Obese) | 397 | 532 | 929 | |

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | |

| Systolic BP | ||||

| ≤129 (Normal) | 40 | 674 | 714 | 0.000 |

| ≥130 (High) | 448 | 848 | 1,296 | |

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | |

| Diastolic BP | ||||

| ≤84 (Normal) | 152 | 1,228 | 1,380 | 0.000 |

| >84 (High) | 336 | 294 | 630 | |

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | |

| FBS (mg/dL) | ||||

| <100 (Normal) | 57 | 674 | 731 | 0.000 |

| 100.0–125.9 (Prediabetic) | 359 | 751 | 1,110 | |

| ≥126 (Diabetic) | 72 | 97 | 169 | |

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | |

| TGs (mg/dL) | ||||

| ≤149.0 (Normal) | 282 | 1,340 | 1,622 | 0.000 |

| >149.0 (High) | 206 | 182 | 388 | |

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | |

| HDL (mg/dL) | ||||

| ≤40.0 (Low) | 127 | 108 | 235 | 0.000 |

| >40.0 (Normal) | 361 | 1,414 | 1,775 | |

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | |

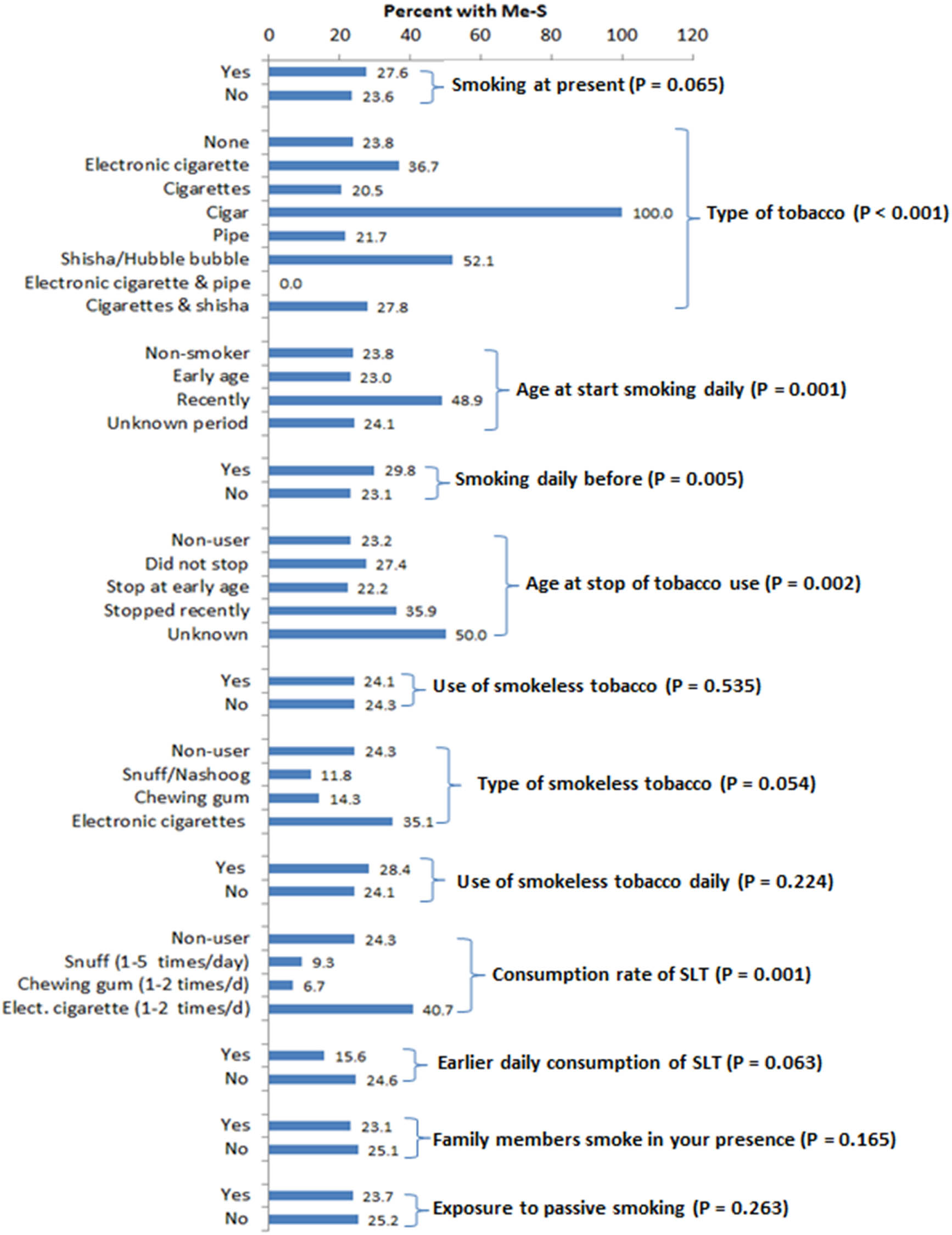

3.3 Association between smoking habits and Met-S

Out of total 2,010 participants, only 94 (4.67%) were smokers. We observed a significant association between type of tobacco and Met-S (Figure 1). Age at start of smoking also played an important role in the progression of Met-S, as the current smokers showed significantly high frequency of Met-S. Previous history of smoking resulted in significantly high frequency of Met-S (P = 0.005), whereas an early cessation of smoking significantly reduced the incidence of Met-S (P = 0.002). Although the use of smoke-less tobacco (SLT) was not associated with Met-S, the rate of consuming SLT showed a significant direct association with Met-S (P = 0.001). Passive smoking was reported by 14% subjects; however, there was no significant association between passive smoking and Met-S (Figure 1).

Association between Met-S and smoking habits or use of tobacco. Values are percentage frequency of Me-S in the same category.

3.4 Association between dietary habits and Met-S

Fruit and vegetable consumptions per se were not associated (P = 0.411 for fruits and P = 0.435 for vegetables) with the prevalence of Met-S in subjects (Table 3). Type of cooking oil and eating fast foods were also not associated with Met-S in young adults (Table 3).

Association of Met-S with feeding habits and nutrition

| Feeding and nutrition | Met-S | Total, N | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | P value | |||

| Do you eat fruits | |||||

| Yes | 410 | 1,287 | 1,697 | 0.411 | |

| No | 78 | 235 | 313 | ||

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | ||

| Fruits consumption (FC)/week | |||||

| No fruit consumption/week | 71 | 205 | 276 | 0.025 | |

| 1.0–3.0 (Times/week) | 277 | 974 | 1,251 | ||

| 4.0–6.0 (Times/week) | 69 | 164 | 233 | ||

| >6.0 (Times/week) | 71 | 179 | 250 | ||

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | ||

| FC/day | |||||

| No fruit consumption/day | 71 | 205 | 276 | 0.166 | |

| 1.0–3.0 (Times/day) | 414 | 1,306 | 1,720 | ||

| 4.0–6.0 (Times/day) | 0 | 8 | 8 | ||

| >6.0 (Times/day) | 3 | 3 | 6 | ||

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | ||

| Do you consume vegetables? | |||||

| Yes | 446 | 1,385 | 1,831 | 0.435 | |

| No | 42 | 137 | 179 | ||

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | ||

| Veg/week | |||||

| No vegetable consumption | 34 | 108 | 142 | 0.288 | |

| 1.0–3.0 (Times/week) | 161 | 541 | 702 | ||

| 4.0–6.0 (Times/week) | 92 | 232 | 324 | ||

| >6.0 (Times/week) | 201 | 641 | 842 | ||

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | ||

| Veg/day | |||||

| No veg. consumption/day | 42 | 137 | 179 | 0.992 | |

| 1.0 (Once per day) | 382 | 1,187 | 1,569 | ||

| 2.0 (Twice per day) | 51 | 156 | 207 | ||

| >2.0 (More times/day) | 13 | 42 | 55 | ||

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | ||

| Type of cooking oil | |||||

| Non-user | 9 | 38 | 47 | 0.108 | |

| Veg. oil | 395 | 1,228 | 1,623 | ||

| Veg. fat | 0 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Butter | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Animal fat | 5 | 6 | 11 | ||

| Veg. oil and veg. fat | 15 | 49 | 64 | ||

| Veg. oil and butter | 7 | 18 | 25 | ||

| Veg. oil and animal fat | 34 | 98 | 132 | ||

| Veg. oil, veg. fat, and butter | 0 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Veg. oil, veg. fat, and anim. fat | 2 | 9 | 11 | ||

| Veg. oil, butter, and anim. fat | 19 | 55 | 74 | ||

| Veg. oil, veg. fat, butter, and anim. fat | 0 | 8 | 8 | ||

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | ||

| Eating fast food | |||||

| Yes | 420 | 1,313 | 1,733 | 0.481 | |

| No | 68 | 209 | 277 | ||

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | ||

| If yes eating-time? | |||||

| Not eating fast food | 68 | 209 | 277 | 0.562 | |

| Breakfast | 19 | 43 | 62 | ||

| Lunch | 32 | 71 | 103 | ||

| Dinner | 203 | 655 | 858 | ||

| Breakfast and lunch | 2 | 3 | 5 | ||

| Breakfast and dinner | 81 | 252 | 333 | ||

| Lunch and dinner | 59 | 213 | 272 | ||

| Breakfast, lunch, and dinner | 24 | 76 | 100 | ||

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | ||

| Days/week | |||||

| Not eating fast food | 68 | 209 | 277 | 0.130 | |

| 1–3 (Days/week) | 270 | 792 | 1,062 | ||

| 4–6 (Days/week) | 99 | 298 | 397 | ||

| 7 (Days/week) | 51 | 223 | 274 | ||

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | ||

3.5 Association between PA and Met-S

A simple query about PA (Yes or No) did not reveal any association between PA and Met-S (P = 0.263; Table 4). However, a categorical breakup of data about the preferences of subjects for footing or driving for various activities including work, prayer, shopping, or combination of these activities showed significant association between mode of PA and Met-S (Table 4).

Association between Met-S and PA

| PA | Met-S | Total, N | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| PA | ||||

| Yes | 433 | 1,377 | 1,810 | 0.263 |

| No | 55 | 145 | 200 | |

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | |

| By foot | ||||

| No footing | 55 | 140 | 195 | 0.000 |

| Work (footing) | 5 | 16 | 21 | |

| Prayer (footing) | 286 | 758 | 1,044 | |

| Shopping (footing) | 6 | 19 | 25 | |

| Work and prayer (footing) | 16 | 38 | 54 | |

| Work and shopping (footing) | 0 | 5 | 5 | |

| Prayer and shopping (footing) | 88 | 462 | 550 | |

| Work, prayer, shopping (footing) | 32 | 84 | 116 | |

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | |

| By car | ||||

| Work (Driving) | 84 | 351 | 435 | 0.026 |

| Prayer (Driving) | 9 | 16 | 25 | |

| Shopping (Driving) | 120 | 298 | 418 | |

| Work and prayer (Driving) | 2 | 3 | 5 | |

| Work and shopping (Driving) | 173 | 574 | 747 | |

| Prayer and shopping (Driving) | 50 | 146 | 196 | |

| Work, prayer, shopping (Driving) | 50 | 134 | 184 | |

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | |

| By foot/week | ||||

| None | 55 | 140 | 195 | 0.187 |

| 1–3 Days | 5 | 20 | 25 | |

| 4–6 Days | 4 | 30 | 34 | |

| 7 Days | 424 | 1,332 | 1,756 | |

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | |

| By car/week | ||||

| Up to 3 days | 19 | 63 | 82 | 0.523 |

| 4–6 Days | 78 | 276 | 354 | |

| 7 Days | 391 | 1,183 | 1,574 | |

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | |

| Time spent driving car/day in minutes | ||||

| Up to 100 min | 227 | 731 | 958 | 0.160 |

| 101–200 min | 134 | 467 | 601 | |

| 201–300 min | 89 | 228 | 317 | |

| >300 min | 38 | 96 | 134 | |

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | |

| Time spent on foot/day in minutes | ||||

| No footing period | 55 | 140 | 195 | 0.293 |

| <30 min | 282 | 883 | 1,165 | |

| 31–60 min | 93 | 277 | 370 | |

| >60 min | 58 | 222 | 280 | |

| Total | 488 | 1,522 | 2,010 | |

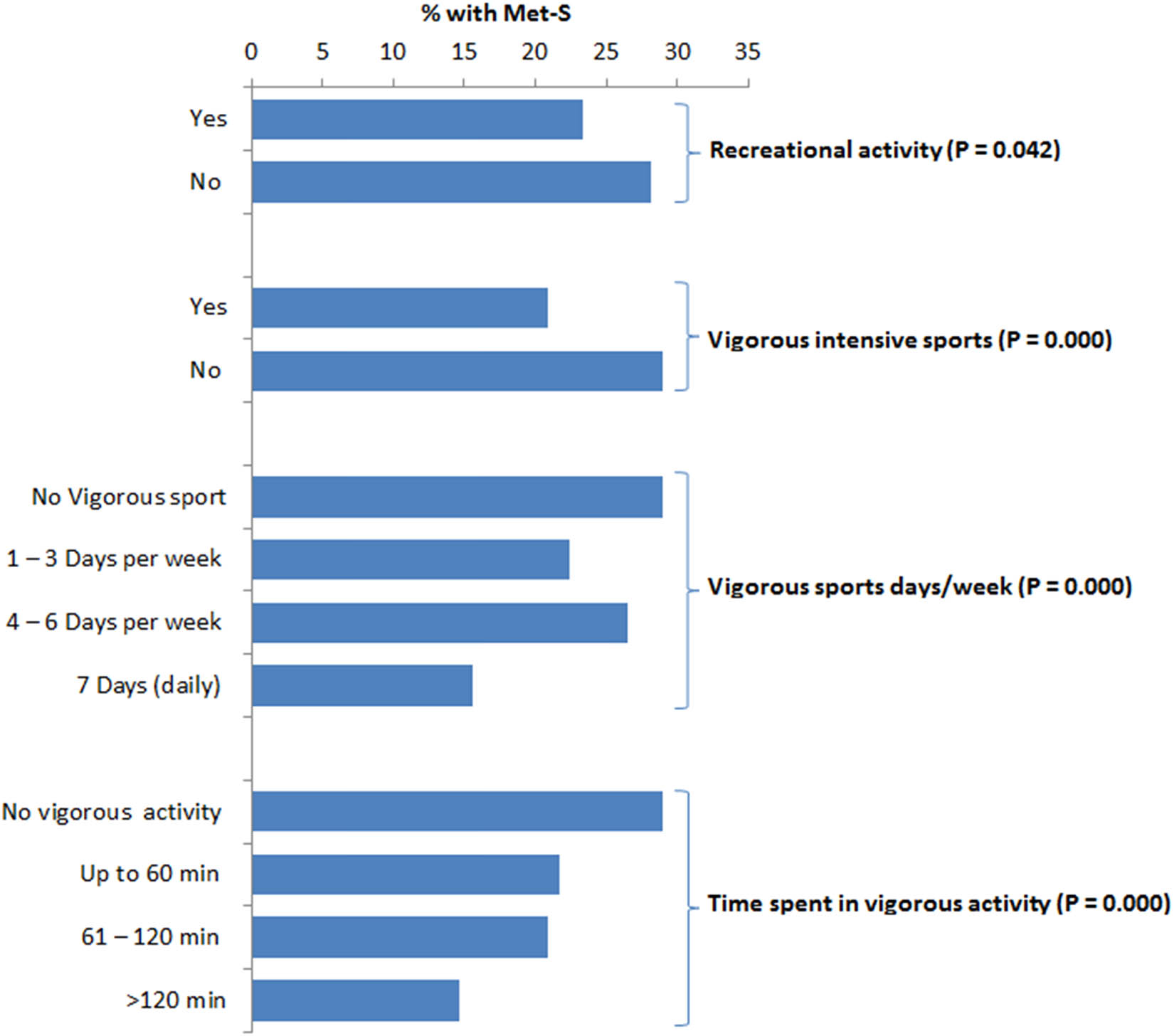

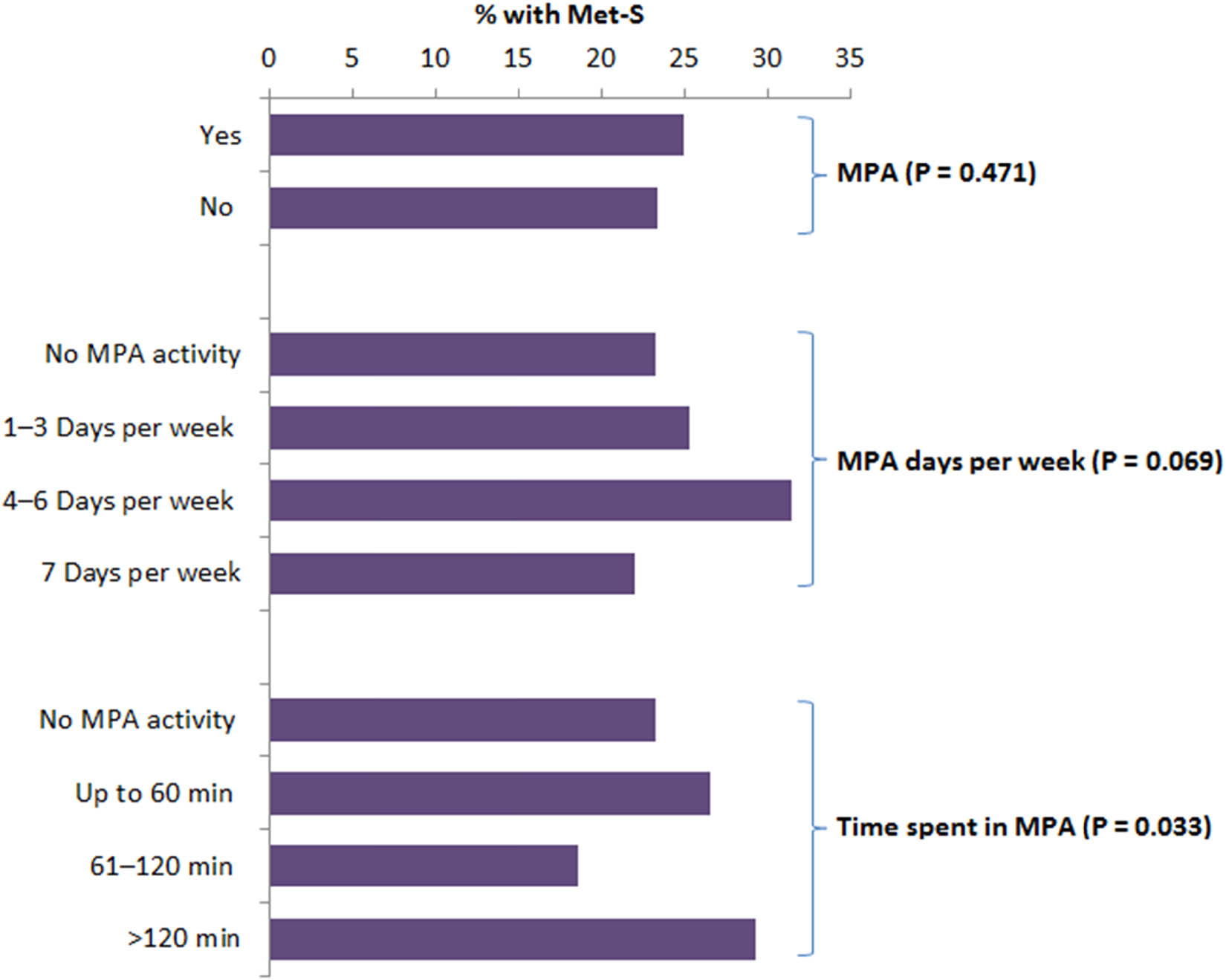

3.6 Association between recreational activity and Met-S

The participants who used to be involved in recreational activity had significantly less frequency of Met-S (P = 0.042; Figure 2). Those who were involved in rigorous intensive sports showed significantly decreased occurrence of Met-S (P < 0.001). Moreover, the time spent is rigorous sporting activity also showed a significant association with Met-S (Figure 2). There was no significant difference in the prevalence of Met-S among those subjects who were involved in moderate physical activity (MPA) compared to those who were not involved in MPA (Figure 3). Even the regularity in MPA was not significantly associated with the incidence of Met-S (Figure 3).

Association between vigorous intensive sports and Met-S. Values are percentage frequency of Met-S in the same category.

Association between MPA and Met-S. Values are percentage frequency of Met-S in the same category.

4 Discussion

Our results showed that demographic factors including age, education level, marital status, and family size are significantly associated with Met-S; however, monthly income did not show any association with Met-S (Table 1). All the component factors including BMI, BP, blood sugar, TGs, and HDL showed highly significant (P < 0.001) association with Met-S (Table 2). A direct correlation of age with Met-S has also been reported by previous investigators [17,18]. Alexander et al. [19] reported that blood glucose, diabetes and BP had a direct relationship with age and BMI, and that prevalence of diabetes and hypertension (components of Met-S) increased with age, which also increased the incidence of Met-S. It has been shown that alarming rates of some risk factors increase with age in cases of diabetes, hypertension, and obesity, and they could be attributed to uncontrolled hyperglycemia and reduced PA in older individuals [8,20].

In our study on young adults, the prevalence of diabetes was found to be 8.40% (Table 2). According to 2014 data, more than 20% of the Saudi Arabian adult population has diabetes while the total number of undiagnosed cases of diabetes among adults is estimated to be more than 1.5 million [21,22]. The projected trajectory for diabetes in Saudi Arabia is alarming, particularly among the 40–49 age group [21]. The increase in the incidence of diabetes in Saudi Arabia has been attributed to changes in cultural and socioeconomic factors, such as increase in affluence, physical inactivity, and changes in dietary habits with the substitution of animal products and refined foods [23,24].

We also observed high prevalence of overweight (11.24%) and obesity (46.21%) in our study population (Table 2). The high rate of overweight and obesity among adolescents is a major public health problem in Saudi Arabia, and is growing at an alarming rate [25], which is more prevalent in Saudi women than in men [26]. Even high frequencies of overweight (15.5%) and obese (6%) have been reported in Saudi schoolchildren [27]. A survey conducted in 2015 among schoolchildren in Riyadh city showed the overall prevalence of overweight and obesity as 13.4 and 18.2%, respectively [28]. In a survey conducted in 2013, the prevalence of obesity was higher among Saudi women (33.5 versus 24.1%), and obesity was strongly associated with diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, marital status, and PA [29]. In a later study, the overall prevalence of overweight and obesity among adults visiting primary care settings in the Southwestern Region of Saudi Arabia was found to be 38.3 and 27.6%, respectively [30]. Mosli et al. [31] observed that individuals in the highest income bracket with lower levels of education have greater odds of obesity. The prevalence of obesity among adults in Saudi Arabia increased from 22% in 1990–1993 to 36% in 2005, and future projections of the prevalence of adult obesity in 2022 was estimated to be 41% in men and 78% in women [32]. Thus, the prevalence of obesity found in our study is comparable to earlier predictions. Military recruits are now less physically fit and more massive, with elevated body fat, highlighting the necessity for regular surveys, monitoring, and effective primary prevention strategies [33]. Obesity is a progressively significant public health problem and is considered a major risk factor for diet-related chronic diseases including Met-S, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, and certain forms of cancer [34].

Although we did not observe a significant association between intake of fruit and vegetables (F&V) and Met-S (Table 3), it has shown beneficial effects on related ailments. A study on 65,226 subjects found that daily eating ≥7 portions of F&V reduced the risk of death due to heart disease by 31% [35]. The Physicians’ Health Study, during a follow-up of 12 years, reported 25% lower incidence of coronary artery disease (CAD) in men who consumed >2.5 or more serving of vegetables daily, compared with those who consumed less than one serving daily [36]. It has been shown that diets high in fiber are significantly associated with lower risks of CVD (stroke and CAD) [37]. Another large prospective cohort study of 84,251 women in the Nurse’ Health Study and 42,148 men in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study reported 30% lower risk of CVD in people with high F&V intake (more than five serving daily) compared to those with low intake. For each increase of one serving per day in F&V, a 4% lower risk of coronary heart disease and 6% lower risk of ischemic stroke were observed [38].

In this study, the mode of tobacco use was significantly associated with Met-S (Figure 1). The global adult tobacco survey showed that in nine Arab countries (Bahrain, Egypt, Libya, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Palestine, Tunisia, and Syria), the prevalence of daily tobacco use exceeds 30% in men [39]. Water pipe smoking is increasing in young Arabs with prevalence estimates between 6 and 34% in age group of 13–15 years [40]. Azadbakht et al. [41] reported that avoiding smoking and limiting alcohol could be beneficial in reducing most of the metabolic risk factors in both sexes. Cigarette smoking increases inflammation and thrombosis leading to oxidative stress manifestation, prothrombotic activity, platelet aggregation, leukocyte activation, lipids peroxidation, and smooth muscle proliferation [42]. Nicotine affects the cardiovascular system by increasing systolic and diastolic BP, heart rate, and cardiac output [43].

We observed a significant role of PA in the development of Met-S. A high prevalence (70%) of physical inactivity has been reported in individuals from gulf countries [39]. Potential influences on individual’s lifestyle were affected by the economic transition in Saudi Arabia through the contribution expedited by recent patterns in occupations that offered inadequate physical activities [8,44]. Physical inactivity is a predictor of CVD events and associated mortality. Sedentary lifestyle for a longer period leads to Met-S and its components, such as increased adipose tissue (predominantly central), reduced HDL cholesterol and a trend towards increased TGs and glucose in genetically susceptible persons. Individuals who spend more than 4 h/day watching television or videos or use their computers have a two-fold increased risk of Met-S compared to those who spend less than 1 h [45].

It is important to note that many risk factors become more damaging when they occur in combination with one another. Most of these risk factors are avoidable and can easily be managed by lifestyle changes. Modifiable risk factors, including hypertension, smoking, diabetes, obesity, dyslipedemia, stress, unhealthy diet, and physical inactivity, are the major contributors to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. These risk factors rarely occur alone, and instead tend to cluster in individuals [46]. The prevalence of uncontrolled hyperglycemia was reported to be high among Saudi diabetic patients while the associated risk factors included older age, male gender, hypertension, smoking, and obesity [47]. Moreover, uncontrolled hyperglycemia has also been directly associated with dyslipidemia [48,49]. It has been demonstrated that five modifiable risk factors such as cigarette smoking, overweight or obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia can be eliminated by management [11]. The occurrence of multiple risk factors is more common, which increases the individual’s risk of CVD from 4-fold with one risk factor to 60-fold in the cluster of five risk factors [50]. The prevalence of multimorbidity (two or more chronic conditions) is increasing, due to growing incidence of chronic conditions and increasing life expectancy [51]. The global burden disease for risk profiles in Middle East and North Africa stranded out these risk factors by order of priority: high BP ranked as the first, followed by obesity, diabetes, smoking, and dyslipidemia [52]. Met-S is progressive, and early indications of disease are evident in adolescents and young adults [53,54]. Some reports suggest that a large number of adolescents already carry one or more risk factors for Met-S [55,56]. Exposure to Met-S risk factors in childhood and adolescence is associated with disease development in adulthood [57,58]. Health risk behaviors tend to establish quite early in life; identifying strategies that deter the adoption and continuation of these health risk factors in younger adults is essential for a long-term prevention of Met-S.

In conclusion, Met-S is prevalent in young military recruits, which is a matter of great concern. Several demographic factors such as age, education, marital status, and family size were significantly associated with Met-S. The component factors of Met-S including BMI, BP, blood sugar, TGs, and HDL showed highly significant association with Met-S. Most of these factors are preventable and can be controlled by modifications in dietary habits and PA. Although MPA was not very effective in reducing Met-S, rigorous physical work and sport activities significantly reduced the incidence of Met-S. These findings will help in designing preventive measures as well as public awareness programs for controlling the high prevalence of Met-S in young adults.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the medical and paramedical staff associated with this project for their excellent services. This project was financially supported (Grant No. 14-MED59-63) by the Advanced and Strategic Technologies program of King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST), Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization: H.A.A. and A.K.A; data curation: H.A.A., G.B.H., A.A., A.A.A., S.G.K., S.A., and F.S.M.; formal analysis: A.K.A., H.A.K., G.B.H., A.A., R.A., and N.M.O.; funding acquisition: H.A.A.; investigation: H.A.A., A.K.A., G.B.H., A.A., A.A.A., S.G.K., S.A., and F.S.M.; methodology: H.A.K., G.B.H., A.A., A.A.A., S.G.K., S.A., F.S.M., R.A., and N.M.O.; project administration: H.A.A. and A.K.A.; resources: H.A.A., A.K.A., G.B.H., A.A., and A.A.A.; software: R.A. and N.M.O.; and writing – review and editing: H.A.A., A.K.A., H.A.K., and N.M.O.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in this work.

-

Data availability statement: Data requests should be addressed to corresponding author.

References

[1] Isomaa B, Almgren P, Tuomi T, Forsen B, Lahti K, Nissen M, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diab Care. 2001;24:683–9.10.2337/diacare.24.4.683Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Lorenzo C, Okoloise M, Williams K, Stern MP, Haffner SM. The metabolic syndrome as predictor of type 2 diabetes: the San Antonio heart study. Diab Care. 2003;26:3153–9.10.2337/diacare.26.11.3153Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] WHO, 2013. A Global Brief on Hypertension Silent Killer: Global Public Health Crisis. World Health Organization; 2013. Available from: http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/publications/global_brief_hypertension/en.Search in Google Scholar

[4] WHO, 2019. Prevention of cardiovascular disease. Guidelines for assessment and management of cardiovascular risk. Geneva: The Organization; 2004 [cited 2019 Sep 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/guidelines/Full%20text.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Hilgenberg FE, Santos AS, Silveira EA, Cominetti C. Cardiovascular risk factors and food consumption of cadets from the Brazilian air force academy. Ciência Saúde Coletiva. 2016;21:1165–74.10.1590/1413-81232015214.15432015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Pasiakos SM, Karl JP, Lutz LJ, Murphy NE, Margolis LM, Rood JC, et al. Cardiometabolic risk in US army recruits and the effects of basic combat training. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31222.10.1371/journal.pone.0031222Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Alzaabi A, AlKaabi J, Al Maskari F, Farhood AF, Ahmed LA. Prevalence of diabetes and cardio-metabolic risk factors in young men in the united Arab emirates: a cross sectional national survey. Endocrinol Diab Metab. 2019;2:e00081.10.1002/edm2.81Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Gutierrez J, Alloubani A, Mari M, Alzaatreh M. Cardiovascular disease risk factors: hypertension, diabetes mellitus and obesity among Tabuk citizens in Saudi Arabia. Open Cardiovas Med J. 2018;12:41–9.10.2174/1874192401812010041Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Al-Qawasmeh RH, Tayyem RF. Dietary and lifestyle risk factors and metabolic syndrome: literature review. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci Jour. 2018;6:594–608.10.12944/CRNFSJ.6.3.03Search in Google Scholar

[10] Al-Hazzaa HM, Abahussain NA, Al-Sobayel HI, Qahwaji DM, Musaiger AO. Physical activity, sedentary behaviors and dietary habits among Saudi adolescents relative to age, gender and region. Int J Behav Nurt Phys Act. 2011;8:140.10.1186/1479-5868-8-140Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Shahwan AJ, Abed Y, Desormais I, Magne J, Preux PM, Aboyans V, et al. Epidemiology of coronary artery disease and stroke and associated risk factors in Gaza community-Palestine. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0211131.10.1371/journal.pone.0211131Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Borraccino A, Lemma P, Berchialla P, Cappello N, Inchley J, Dalmasso P, et al. Italian HBSC 2010 Group. Unhealthy food consumption in adolescence: role of sedentary behaviours and modifiers in 11-, 13- and 15-year-old Italians. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26:650–6.10.1093/eurpub/ckw056Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Cuenca-Garcia M, Ortega FB, Huybrechts J, Ruiz R, González-Gross M, Ottevaere C, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and dietary intake in European adolescents: the healthy lifestyle in Europe by nutrition in adolescence study. Br J Nutr. 2012;107:1850–9.10.1017/S0007114511005149Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Alqarni SS. A review of prevalence of obesity in Saudi Arabia. J Obes Eat Disord. 2016;2:2.10.21767/2471-8203.100025Search in Google Scholar

[15] Shennar-Golan V, Walter O. Physical activity intensity among adolescents and association with parent–adolescent relationship and well-being. Am J Men Health. 2018;12:1530–40.10.1177/1557988318768600Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Chobanian A, Bakris G, Black H, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo Jr JL, et al. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;290:97.10.1001/jama.290.2.197Search in Google Scholar

[17] Redon J, Cifkova R, Laurent S, Nilsson P, Narkiewicz K, Erdine S, et al. The metabolic syndrome in hypertension: European society of hypertension position statement. Sci Counc Eur Soc Hypertens. 2008;26:1891–900.10.1097/HJH.0b013e328302ca38Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Sarah DF. Metabolic syndrome and associated factors among out patients in kumasi metropolis. This dissertation is submitted to the University of Ghana, Legon in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the award of master of public health degree; 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Alexander MR, Madhur MS, Harrison DG, Dreisbach WA, Riaz K. Hypertension: practice essentials, background and pathophysiology. Medscape. 2017;8:29–35.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Singh GM, Danaei G, Farzadfar F, Stevens GA, Woodward M, Wormser D, et al. The age-specific quantitative effects of metabolic risk factors on cardiovascular diseases and diabetes: a pooled analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65174.10.1371/journal.pone.0065174Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] International Diabetes Federation (IDF); 2015. Available from: www.idf.org.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Sherwani SI, Khan HA, Ekhzaimy A, Masood A, Sakharkar MK. Significance of HbA1c test in diagnosis and prognosis of diabetic patients. Biomarker Insight. 2016;11:95–104.10.4137/BMI.S38440Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Amin TT, Al-Sultan AI, Ali A. Overweight and obesity and their relation to dietary habits and socio-demographic characteristics among male primary schoolchildren in Al-Hassa, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Eur J Nutr. 2008;47:310–8.10.1007/s00394-008-0727-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Al-Rubeaan K, Al-Manaa HA, Khoja TA, Ahmad NA, Al-Sharqawi AH, Siddiqui K, et al. Epidemiology of abnormal glucose metabolism in a country facing its epidemic: SAUDI-DM study. J Diabetes. 2015;7:622–32.10.1111/1753-0407.12224Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Habbab RM, Bhutta ZA. Prevalence and social determinants of overweight and obesity in adolescents in Saudi Arabia: a systematic review. Clin Obes. 2020;10:e12400.10.1111/cob.12400Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] DeNicola E, Aburizaiza OS, Siddique A, Khwaja H, Carpenter DO. Obesity and public health in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Rev Env Health. 2015;30:191–205.10.1515/reveh-2015-0008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Alyousef SM, Alhamidi SA. Exploring the contributory factors toward childhood obesity and being overweight in Saudi Arabia and the gulf states. J Transcult Nurs. 2020;31:360–8.10.1177/1043659619868286Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Al-Hussaini A, Bashir MS, Khormi M, AlTuraiki M, Alkhamis W, Alrajhi M, et al. Overweight and obesity among Saudi children and adolescents: where do we stand today? Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:229–35.10.4103/sjg.SJG_617_18Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Memish ZA, El Bcheraoui C, Tuffaha M, Robinson M, Daoud F, Jaber S, et al. Obesity and associated factors–Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E174.10.5888/pcd11.140236Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Al-Qahtani AM. Prevalence and predictors of obesity and overweight among adults visiting primary care settings in the Southwestern region, Saudi Arabia. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:8073057.10.1155/2019/8073057Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Mosli HH, Kutbi HA, Alhasan AH, Mosli RH. Understanding the interrelationship between education, income, and obesity among adults in Saudi Arabia. Obes Facts. 2020;13:77–85.10.1159/000505246Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Al-Quwaidhi AJ, Pearce MS, Critchley JA, Sobngwi E, O’Flaherty M. Trends and future projections of the prevalence of adult obesity in Saudi Arabia, 1992–2022. East Mediterr Health J. 2014;20:589–95.10.26719/2014.20.10.589Search in Google Scholar

[33] Knapik JJ, Sharp MA, Darakjy S, Jones SB, Hauret KG, Jones BH, et al. Temporal changes in the physical fitness of US Army recruits. Sport Med. 2006;36:613–34.10.2165/00007256-200636070-00005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Grundy SM, Brewer HB Jr, Cleeman JI, Smith Jr SC, Lenfant C, American Heart Association, et al. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109:433–8.10.1161/01.CIR.0000111245.75752.C6Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Oyebode O, Gordon-Dseagu V, Walker A, Mindell JS. Fruit and vegetable consumption and all-cause, cancer and CVD mortality: analysis of Health Survey for England data. J Epid Comm Health. 2014;68:856–62.10.1136/jech-2013-203500Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Liu S, Lee IM, Ajani U, Cole SR, Buring JE, Manson JE, et al. Intake of vegetables rich in carotenoids and risk of coronary heart disease in men: the physicians’ health study. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:130–5.10.1093/ije/30.1.130Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Berciano S, Ordovás JM. Nutrition and cardiovascular health. Rev Español Cardiol. 2014;67:738–47.10.1016/j.rec.2014.05.003Search in Google Scholar

[38] Joshipura KJ, Ascherio A, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Rimm EB, Speizer FE, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake in relation to risk of ischemic stroke. JAMA. 1999;282:1233–9.10.1001/jama.282.13.1233Search in Google Scholar

[39] Rahim HFA, Sibai A, Khader Y, Hwalla N, Fadhil I, Alsiyabi H, et al. Non-communicable diseases in the Arab world. Lancet. 2014;383:356–67.10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62383-1Search in Google Scholar

[40] Kheirallah KA, Alsulaiman JW, Mohammad HAS, Alzyoud S, Veeranki SP, Ward KD. Waterpipe tobacco smoking among Arab youth; a cross-country study. Ethn Dis. 2016;26:107–12.10.18865/ed.26.1.107Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Azadbakht L, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Dietary diversity score is favorably associated with the metabolic syndrome in Tehranian adults. Int J Obes. 2005;29:1361–7.10.1038/sj.ijo.0803029Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Ambrose JA, Barua RS. The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: an update. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1731–7.10.1016/j.jacc.2003.12.047Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Filion KB, Luepker RV. Cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: Lessons from Framingham. Glob Heart. 2013;8:35–41.10.1016/j.gheart.2012.12.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] El Bcheraoui C, Basulaiman M, Tuffaha M, Daoud F, Robinson M, Jaber S, et al. Status of the diabetes epidemic in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2013. Int J Public Health. 2014;59:1011–21.10.1007/s00038-014-0612-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Alarabi F, Alswat KA. Lifestyle pattern assessment among Taif university medical students. Brock J Educ. 2017;5:54–9.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Meigs JB, D’Agostino RB, Wilson PW, Cupples LA, Nathan DM, Singer DE. Risk variable clustering in the insulin resistance syndrome. The Framingham offspring study. Diabetes. 1997;46:1594–600.10.2337/diacare.46.10.1594Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Riaz F, Al Shaikh A, Anjum Q, Mudawi Alqahtani Y, Shahid S. Factors related to the uncontrolled fasting blood sugar among type 2 diabetic patients attending primary health care center, Abha city, Saudi Arabia. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e14168.10.1111/ijcp.14168Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Khan HA. Clinical significance of HbA1c as a marker of circulating lipids in male and female type 2 diabetic patients. Acta Diabetol. 2007;44:193–200.10.1007/s00592-007-0003-xSearch in Google Scholar

[49] Khan HA, Sobki SH, Khan SA. Association between glycemic control and serum lipids profile in type 2 diabetic patients: HbA1c predicts dyslipidemia. Clin Exp Med. 2007;7:24–9.10.1007/s10238-007-0121-3Search in Google Scholar

[50] Wilson PW, Kannel WB, Silbershatz H, D’Agostino RB. Clustering of metabolic factors and coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1104–9.10.1001/archinte.159.10.1104Search in Google Scholar

[51] Uijen AA, van de Lisdonk EH. Multimorbidity in primary care: prevalence and trend over the last 20 years. Eur J Gen Pract. 2008;14:28–32.10.1080/13814780802436093Search in Google Scholar

[52] Forouzanfar MH, Afshin A, Alexander LT, Anderson HR, Bhutta ZA, Biryukov S, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1659–724.10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8Search in Google Scholar

[53] Bintoro BS, Fan YC, Chou CC, Chien KL, Bai CH. Metabolic unhealthiness increases the likelihood of having metabolic syndrome components in norm weight young adults. Int J Env Res Pub Health. 2019;16:3258.10.3390/ijerph16183258Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] Tobisch B, Blatniczky L, Barkai L. Cardiometabolic risk factors and insulin resistance in obese children and adolescents: relation to puberty. Pediatr Obes. 2013;10:37–44.10.1111/j.2047-6310.2013.00202.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Wang J, Perona JS, Schmidt-RioValle J, Chen Y, Jing J, González-Jiménez E. Metabolic syndrome and its associated early-life factors among Chinese and Spanish adolescents: a pilot study. Nutrients. 2019;11:1568.10.3390/nu11071568Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[56] Vaquero Alvarez M, Aparicio-Martinez P, Fonseca Pozo FJ, Valle Alonso J, Blancas Sánchez IM, Romero-Saldaña MA. Sustainable approach to the metabolic syndrome in children and its economic burden. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2020;17:1891.10.3390/ijerph17061891Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[57] Taha D, Ahmed O, Sadiq BB. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk factors in a group of obese Saudi children and adolescents: a hospital-based study. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29:357–60.10.4103/0256-4947.55164Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[58] Hosseinpanah F, Asghari G, Barzin M, Ghareh S, Azizi F. Adolescence metabolic syndrome or adiposity and early adult metabolic syndrome. J Pediatr. 2013;163:1663–9.10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.07.032Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2022 Hamoud A. Al Shehri et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- AMBRA1 attenuates the proliferation of uveal melanoma cells

- A ceRNA network mediated by LINC00475 in papillary thyroid carcinoma

- Differences in complications between hepatitis B-related cirrhosis and alcohol-related cirrhosis

- Effect of gestational diabetes mellitus on lipid profile: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Long noncoding RNA NR2F1-AS1 stimulates the tumorigenic behavior of non-small cell lung cancer cells by sponging miR-363-3p to increase SOX4

- Promising novel biomarkers and candidate small-molecule drugs for lung adenocarcinoma: Evidence from bioinformatics analysis of high-throughput data

- Plasmapheresis: Is it a potential alternative treatment for chronic urticaria?

- The biomarkers of key miRNAs and gene targets associated with extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma

- Gene signature to predict prognostic survival of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Effects of miRNA-199a-5p on cell proliferation and apoptosis of uterine leiomyoma by targeting MED12

- Does diabetes affect paraneoplastic thrombocytosis in colorectal cancer?

- Is there any effect on imprinted genes H19, PEG3, and SNRPN during AOA?

- Leptin and PCSK9 concentrations are associated with vascular endothelial cytokines in patients with stable coronary heart disease

- Pericentric inversion of chromosome 6 and male fertility problems

- Staple line reinforcement with nebulized cyanoacrylate glue in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: A propensity score-matched study

- Retrospective analysis of crescent score in clinical prognosis of IgA nephropathy

- Expression of DNM3 is associated with good outcome in colorectal cancer

- Activation of SphK2 contributes to adipocyte-induced EOC cell proliferation

- CRRT influences PICCO measurements in febrile critically ill patients

- SLCO4A1-AS1 mediates pancreatic cancer development via miR-4673/KIF21B axis

- lncRNA ACTA2-AS1 inhibits malignant phenotypes of gastric cancer cells

- circ_AKT3 knockdown suppresses cisplatin resistance in gastric cancer

- Prognostic value of nicotinamide N-methyltransferase in human cancers: Evidence from a meta-analysis and database validation

- GPC2 deficiency inhibits cell growth and metastasis in colon adenocarcinoma

- A pan-cancer analysis of the oncogenic role of Holliday junction recognition protein in human tumors

- Radiation increases COL1A1, COL3A1, and COL1A2 expression in breast cancer

- Association between preventable risk factors and metabolic syndrome

- miR-29c-5p knockdown reduces inflammation and blood–brain barrier disruption by upregulating LRP6

- Cardiac contractility modulation ameliorates myocardial metabolic remodeling in a rabbit model of chronic heart failure through activation of AMPK and PPAR-α pathway

- Quercitrin protects human bronchial epithelial cells from oxidative damage

- Smurf2 suppresses the metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma via ubiquitin degradation of Smad2

- circRNA_0001679/miR-338-3p/DUSP16 axis aggravates acute lung injury

- Sonoclot’s usefulness in prediction of cardiopulmonary arrest prognosis: A proof of concept study

- Four drug metabolism-related subgroups of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in prognosis, immune infiltration, and gene mutation

- Decreased expression of miR-195 mediated by hypermethylation promotes osteosarcoma

- LMO3 promotes proliferation and metastasis of papillary thyroid carcinoma cells by regulating LIMK1-mediated cofilin and the β-catenin pathway

- Cx43 upregulation in HUVECs under stretch via TGF-β1 and cytoskeletal network

- Evaluation of menstrual irregularities after COVID-19 vaccination: Results of the MECOVAC survey

- Histopathologic findings on removed stomach after sleeve gastrectomy. Do they influence the outcome?

- Analysis of the expression and prognostic value of MT1-MMP, β1-integrin and YAP1 in glioma

- Optimal diagnosis of the skin cancer using a hybrid deep neural network and grasshopper optimization algorithm

- miR-223-3p alleviates TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and extracellular matrix deposition by targeting SP3 in endometrial epithelial cells

- Clinical value of SIRT1 as a prognostic biomarker in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, a systematic meta-analysis

- circ_0020123 promotes cell proliferation and migration in lung adenocarcinoma via PDZD8

- miR-22-5p regulates the self-renewal of spermatogonial stem cells by targeting EZH2

- hsa-miR-340-5p inhibits epithelial–mesenchymal transition in endometriosis by targeting MAP3K2 and inactivating MAPK/ERK signaling

- circ_0085296 inhibits the biological functions of trophoblast cells to promote the progression of preeclampsia via the miR-942-5p/THBS2 network

- TCD hemodynamics findings in the subacute phase of anterior circulation stroke patients treated with mechanical thrombectomy

- Development of a risk-stratification scoring system for predicting risk of breast cancer based on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, non-alcoholic fatty pancreas disease, and uric acid

- Tollip promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression via PI3K/AKT pathway

- circ_0062491 alleviates periodontitis via the miR-142-5p/IGF1 axis

- Human amniotic fluid as a source of stem cells

- lncRNA NONRATT013819.2 promotes transforming growth factor-β1-induced myofibroblastic transition of hepatic stellate cells by miR24-3p/lox

- NORAD modulates miR-30c-5p-LDHA to protect lung endothelial cells damage

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis telemedicine management during COVID-19 outbreak

- Risk factors for adverse drug reactions associated with clopidogrel therapy

- Serum zinc associated with immunity and inflammatory markers in Covid-19

- The relationship between night shift work and breast cancer incidence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies

- LncRNA expression in idiopathic achalasia: New insight and preliminary exploration into pathogenesis

- Notoginsenoside R1 alleviates spinal cord injury through the miR-301a/KLF7 axis to activate Wnt/β-catenin pathway

- Moscatilin suppresses the inflammation from macrophages and T cells

- Zoledronate promotes ECM degradation and apoptosis via Wnt/β-catenin

- Epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related genes in coronary artery disease

- The effect evaluation of traditional vaginal surgery and transvaginal mesh surgery for severe pelvic organ prolapse: 5 years follow-up

- Repeated partial splenic artery embolization for hypersplenism improves platelet count

- Low expression of miR-27b in serum exosomes of non-small cell lung cancer facilitates its progression by affecting EGFR

- Exosomal hsa_circ_0000519 modulates the NSCLC cell growth and metastasis via miR-1258/RHOV axis

- miR-455-5p enhances 5-fluorouracil sensitivity in colorectal cancer cells by targeting PIK3R1 and DEPDC1

- The effect of tranexamic acid on the reduction of intraoperative and postoperative blood loss and thromboembolic risk in patients with hip fracture

- Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 mutation in cholangiocarcinoma impairs tumor progression by sensitizing cells to ferroptosis

- Artemisinin protects against cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury via inhibiting the NF-κB pathway

- A 16-gene signature associated with homologous recombination deficiency for prognosis prediction in patients with triple-negative breast cancer

- Lidocaine ameliorates chronic constriction injury-induced neuropathic pain through regulating M1/M2 microglia polarization

- MicroRNA 322-5p reduced neuronal inflammation via the TLR4/TRAF6/NF-κB axis in a rat epilepsy model

- miR-1273h-5p suppresses CXCL12 expression and inhibits gastric cancer cell invasion and metastasis

- Clinical characteristics of pneumonia patients of long course of illness infected with SARS-CoV-2

- circRNF20 aggravates the malignancy of retinoblastoma depending on the regulation of miR-132-3p/PAX6 axis

- Linezolid for resistant Gram-positive bacterial infections in children under 12 years: A meta-analysis

- Rack1 regulates pro-inflammatory cytokines by NF-κB in diabetic nephropathy

- Comprehensive analysis of molecular mechanism and a novel prognostic signature based on small nuclear RNA biomarkers in gastric cancer patients

- Smog and risk of maternal and fetal birth outcomes: A retrospective study in Baoding, China

- Let-7i-3p inhibits the cell cycle, proliferation, invasion, and migration of colorectal cancer cells via downregulating CCND1

- β2-Adrenergic receptor expression in subchondral bone of patients with varus knee osteoarthritis

- Possible impact of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on suicide behavior among patients in Southeast Serbia

- In vitro antimicrobial activity of ozonated oil in liposome eyedrop against multidrug-resistant bacteria

- Potential biomarkers for inflammatory response in acute lung injury

- A low serum uric acid concentration predicts a poor prognosis in adult patients with candidemia

- Antitumor activity of recombinant oncolytic vaccinia virus with human IL2

- ALKBH5 inhibits TNF-α-induced apoptosis of HUVECs through Bcl-2 pathway

- Risk prediction of cardiovascular disease using machine learning classifiers

- Value of ultrasonography parameters in diagnosing polycystic ovary syndrome

- Bioinformatics analysis reveals three key genes and four survival genes associated with youth-onset NSCLC

- Identification of autophagy-related biomarkers in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension based on bioinformatics analysis

- Protective effects of glaucocalyxin A on the airway of asthmatic mice

- Overexpression of miR-100-5p inhibits papillary thyroid cancer progression via targeting FZD8

- Bioinformatics-based analysis of SUMOylation-related genes in hepatocellular carcinoma reveals a role of upregulated SAE1 in promoting cell proliferation

- Effectiveness and clinical benefits of new anti-diabetic drugs: A real life experience

- Identification of osteoporosis based on gene biomarkers using support vector machine

- Tanshinone IIA reverses oxaliplatin resistance in colorectal cancer through microRNA-30b-5p/AVEN axis

- miR-212-5p inhibits nasopharyngeal carcinoma progression by targeting METTL3

- Association of ST-T changes with all-cause mortality among patients with peripheral T-cell lymphomas

- LINC00665/miRNAs axis-mediated collagen type XI alpha 1 correlates with immune infiltration and malignant phenotypes in lung adenocarcinoma

- The perinatal factors that influence the excretion of fecal calprotectin in premature-born children

- Effect of femoral head necrosis cystic area on femoral head collapse and stress distribution in femoral head: A clinical and finite element study

- Does the use of 3D-printed cones give a chance to postpone the use of megaprostheses in patients with large bone defects in the knee joint?

- lncRNA HAGLR modulates myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury in mice through regulating miR-133a-3p/MAPK1 axis

- Protective effect of ghrelin on intestinal I/R injury in rats

- In vivo knee kinematics of an innovative prosthesis design

- Relationship between the height of fibular head and the incidence and severity of knee osteoarthritis

- lncRNA WT1-AS attenuates hypoxia/ischemia-induced neuronal injury during cerebral ischemic stroke via miR-186-5p/XIAP axis

- Correlation of cardiac troponin T and APACHE III score with all-cause in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients with acute pulmonary embolism

- LncRNA LINC01857 reduces metastasis and angiogenesis in breast cancer cells via regulating miR-2052/CENPQ axis

- Endothelial cell-specific molecule 1 (ESM1) promoted by transcription factor SPI1 acts as an oncogene to modulate the malignant phenotype of endometrial cancer

- SELENBP1 inhibits progression of colorectal cancer by suppressing epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- Visfatin is negatively associated with coronary artery lesions in subjects with impaired fasting glucose

- Treatment and outcomes of mechanical complications of acute myocardial infarction during the Covid-19 era: A comparison with the pre-Covid-19 period. A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Neonatal stroke surveillance study protocol in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland

- Oncogenic role of TWF2 in human tumors: A pan-cancer analysis

- Mean corpuscular hemoglobin predicts the length of hospital stay independent of severity classification in patients with acute pancreatitis

- Association of gallstone and polymorphisms of UGT1A1*27 and UGT1A1*28 in patients with hepatitis B virus-related liver failure

- TGF-β1 upregulates Sar1a expression and induces procollagen-I secretion in hypertrophic scarring fibroblasts

- Antisense lncRNA PCNA-AS1 promotes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma progression through the miR-2467-3p/PCNA axis

- NK-cell dysfunction of acute myeloid leukemia in relation to the renin–angiotensin system and neurotransmitter genes

- The effect of dilution with glucose and prolonged injection time on dexamethasone-induced perineal irritation – A randomized controlled trial

- miR-146-5p restrains calcification of vascular smooth muscle cells by suppressing TRAF6

- Role of lncRNA MIAT/miR-361-3p/CCAR2 in prostate cancer cells

- lncRNA NORAD promotes lung cancer progression by competitively binding to miR-28-3p with E2F2

- Noninvasive diagnosis of AIH/PBC overlap syndrome based on prediction models

- lncRNA FAM230B is highly expressed in colorectal cancer and suppresses the maturation of miR-1182 to increase cell proliferation

- circ-LIMK1 regulates cisplatin resistance in lung adenocarcinoma by targeting miR-512-5p/HMGA1 axis

- LncRNA SNHG3 promoted cell proliferation, migration, and metastasis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma via regulating miR-151a-3p/PFN2 axis

- Risk perception and affective state on work exhaustion in obstetrics during the COVID-19 pandemic

- lncRNA-AC130710/miR-129-5p/mGluR1 axis promote migration and invasion by activating PKCα-MAPK signal pathway in melanoma

- SNRPB promotes cell cycle progression in thyroid carcinoma via inhibiting p53

- Xylooligosaccharides and aerobic training regulate metabolism and behavior in rats with streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetes

- Serpin family A member 1 is an oncogene in glioma and its translation is enhanced by NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 through RNA-binding activity

- Silencing of CPSF7 inhibits the proliferation, migration, and invasion of lung adenocarcinoma cells by blocking the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

- Ultrasound-guided lumbar plexus block versus transversus abdominis plane block for analgesia in children with hip dislocation: A double-blind, randomized trial

- Relationship of plasma MBP and 8-oxo-dG with brain damage in preterm

- Identification of a novel necroptosis-associated miRNA signature for predicting the prognosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- Delayed femoral vein ligation reduces operative time and blood loss during hip disarticulation in patients with extremity tumors

- The expression of ASAP3 and NOTCH3 and the clinicopathological characteristics of adult glioma patients

- Longitudinal analysis of factors related to Helicobacter pylori infection in Chinese adults

- HOXA10 enhances cell proliferation and suppresses apoptosis in esophageal cancer via activating p38/ERK signaling pathway

- Meta-analysis of early-life antibiotic use and allergic rhinitis

- Marital status and its correlation with age, race, and gender in prognosis of tonsil squamous cell carcinomas

- HPV16 E6E7 up-regulates KIF2A expression by activating JNK/c-Jun signal, is beneficial to migration and invasion of cervical cancer cells

- Amino acid profiles in the tissue and serum of patients with liver cancer

- Pain in critically ill COVID-19 patients: An Italian retrospective study

- Immunohistochemical distribution of Bcl-2 and p53 apoptotic markers in acetamiprid-induced nephrotoxicity

- Estradiol pretreatment in GnRH antagonist protocol for IVF/ICSI treatment

- Long non-coding RNAs LINC00689 inhibits the apoptosis of human nucleus pulposus cells via miR-3127-5p/ATG7 axis-mediated autophagy

- The relationship between oxygen therapy, drug therapy, and COVID-19 mortality

- Monitoring hypertensive disorders in pregnancy to prevent preeclampsia in pregnant women of advanced maternal age: Trial mimicking with retrospective data

- SETD1A promotes the proliferation and glycolysis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells by activating the PI3K/Akt pathway

- The role of Shunaoxin pills in the treatment of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion and its main pharmacodynamic components

- TET3 governs malignant behaviors and unfavorable prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by activating the PI3K/AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin pathway

- Associations between morphokinetic parameters of temporary-arrest embryos and the clinical prognosis in FET cycles

- Long noncoding RNA WT1-AS regulates trophoblast proliferation, migration, and invasion via the microRNA-186-5p/CADM2 axis

- The incidence of bronchiectasis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Integrated bioinformatics analysis shows integrin alpha 3 is a prognostic biomarker for pancreatic cancer

- Inhibition of miR-21 improves pulmonary vascular responses in bronchopulmonary dysplasia by targeting the DDAH1/ADMA/NO pathway

- Comparison of hospitalized patients with severe pneumonia caused by COVID-19 and influenza A (H7N9 and H1N1): A retrospective study from a designated hospital

- lncRNA ZFAS1 promotes intervertebral disc degeneration by upregulating AAK1

- Pathological characteristics of liver injury induced by N,N-dimethylformamide: From humans to animal models

- lncRNA ELFN1-AS1 enhances the progression of colon cancer by targeting miR-4270 to upregulate AURKB

- DARS-AS1 modulates cell proliferation and migration of gastric cancer cells by regulating miR-330-3p/NAT10 axis

- Dezocine inhibits cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by targeting CRABP2 in ovarian cancer

- MGST1 alleviates the oxidative stress of trophoblast cells induced by hypoxia/reoxygenation and promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by activating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway

- Bifidobacterium lactis Probio-M8 ameliorated the symptoms of type 2 diabetes mellitus mice by changing ileum FXR-CYP7A1

- circRNA DENND1B inhibits tumorigenicity of clear cell renal cell carcinoma via miR-122-5p/TIMP2 axis

- EphA3 targeted by miR-3666 contributes to melanoma malignancy via activating ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK pathways

- Pacemakers and methylprednisolone pulse therapy in immune-related myocarditis concomitant with complete heart block

- miRNA-130a-3p targets sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 to activate the microglial and astrocytes and to promote neural injury under the high glucose condition

- Review Articles

- Current management of cancer pain in Italy: Expert opinion paper

- Hearing loss and brain disorders: A review of multiple pathologies

- The rationale for using low-molecular weight heparin in the therapy of symptomatic COVID-19 patients

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and delayed onset muscle soreness in light of the impaired blink and stretch reflexes – watch out for Piezo2

- Interleukin-35 in autoimmune dermatoses: Current concepts

- Recent discoveries in microbiota dysbiosis, cholangiocytic factors, and models for studying the pathogenesis of primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Advantages of ketamine in pediatric anesthesia

- Congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Role of dentist in early diagnosis

- Migraine management: Non-pharmacological points for patients and health care professionals

- Atherogenic index of plasma and coronary artery disease: A systematic review

- Physiological and modulatory role of thioredoxins in the cellular function

- Case Reports

- Intrauterine Bakri balloon tamponade plus cervical cerclage for the prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage in late pregnancy complicated with acute aortic dissection: Case series

- A case of successful pembrolizumab monotherapy in a patient with advanced lung adenocarcinoma: Use of multiple biomarkers in combination for clinical practice

- Unusual neurological manifestations of bilateral medial medullary infarction: A case report

- Atypical symptoms of malignant hyperthermia: A rare causative mutation in the RYR1 gene

- A case report of dermatomyositis with the missed diagnosis of non-small cell lung cancer and concurrence of pulmonary tuberculosis

- A rare case of endometrial polyp complicated with uterine inversion: A case report and clinical management

- Spontaneous rupturing of splenic artery aneurysm: Another reason for fatal syncope and shock (Case report and literature review)

- Fungal infection mimicking COVID-19 infection – A case report

- Concurrent aspergillosis and cystic pulmonary metastases in a patient with tongue squamous cell carcinoma

- Paraganglioma-induced inverted takotsubo-like cardiomyopathy leading to cardiogenic shock successfully treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- Lineage switch from lymphoma to myeloid neoplasms: First case series from a single institution

- Trismus during tracheal extubation as a complication of general anaesthesia – A case report

- Simultaneous treatment of a pubovesical fistula and lymph node metastasis secondary to multimodal treatment for prostate cancer: Case report and review of the literature

- Two case reports of skin vasculitis following the COVID-19 immunization

- Ureteroiliac fistula after oncological surgery: Case report and review of the literature

- Synchronous triple primary malignant tumours in the bladder, prostate, and lung harbouring TP53 and MEK1 mutations accompanied with severe cardiovascular diseases: A case report

- Huge mucinous cystic neoplasms with adhesion to the left colon: A case report and literature review

- Commentary

- Commentary on “Clinicopathological features of programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma”

- Rapid Communication

- COVID-19 fear, post-traumatic stress, growth, and the role of resilience

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Tollip promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression via PI3K/AKT pathway”

- Erratum to “Effect of femoral head necrosis cystic area on femoral head collapse and stress distribution in femoral head: A clinical and finite element study”

- Erratum to “lncRNA NORAD promotes lung cancer progression by competitively binding to miR-28-3p with E2F2”

- Retraction

- Expression and role of ABIN1 in sepsis: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Retraction to “miR-519d downregulates LEP expression to inhibit preeclampsia development”

- Special Issue Computational Intelligence Methodologies Meets Recurrent Cancers - Part II

- Usefulness of close surveillance for rectal cancer patients after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- AMBRA1 attenuates the proliferation of uveal melanoma cells

- A ceRNA network mediated by LINC00475 in papillary thyroid carcinoma

- Differences in complications between hepatitis B-related cirrhosis and alcohol-related cirrhosis

- Effect of gestational diabetes mellitus on lipid profile: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Long noncoding RNA NR2F1-AS1 stimulates the tumorigenic behavior of non-small cell lung cancer cells by sponging miR-363-3p to increase SOX4

- Promising novel biomarkers and candidate small-molecule drugs for lung adenocarcinoma: Evidence from bioinformatics analysis of high-throughput data

- Plasmapheresis: Is it a potential alternative treatment for chronic urticaria?

- The biomarkers of key miRNAs and gene targets associated with extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma

- Gene signature to predict prognostic survival of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Effects of miRNA-199a-5p on cell proliferation and apoptosis of uterine leiomyoma by targeting MED12

- Does diabetes affect paraneoplastic thrombocytosis in colorectal cancer?

- Is there any effect on imprinted genes H19, PEG3, and SNRPN during AOA?

- Leptin and PCSK9 concentrations are associated with vascular endothelial cytokines in patients with stable coronary heart disease

- Pericentric inversion of chromosome 6 and male fertility problems

- Staple line reinforcement with nebulized cyanoacrylate glue in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: A propensity score-matched study

- Retrospective analysis of crescent score in clinical prognosis of IgA nephropathy

- Expression of DNM3 is associated with good outcome in colorectal cancer

- Activation of SphK2 contributes to adipocyte-induced EOC cell proliferation

- CRRT influences PICCO measurements in febrile critically ill patients

- SLCO4A1-AS1 mediates pancreatic cancer development via miR-4673/KIF21B axis

- lncRNA ACTA2-AS1 inhibits malignant phenotypes of gastric cancer cells

- circ_AKT3 knockdown suppresses cisplatin resistance in gastric cancer

- Prognostic value of nicotinamide N-methyltransferase in human cancers: Evidence from a meta-analysis and database validation

- GPC2 deficiency inhibits cell growth and metastasis in colon adenocarcinoma

- A pan-cancer analysis of the oncogenic role of Holliday junction recognition protein in human tumors

- Radiation increases COL1A1, COL3A1, and COL1A2 expression in breast cancer

- Association between preventable risk factors and metabolic syndrome

- miR-29c-5p knockdown reduces inflammation and blood–brain barrier disruption by upregulating LRP6

- Cardiac contractility modulation ameliorates myocardial metabolic remodeling in a rabbit model of chronic heart failure through activation of AMPK and PPAR-α pathway

- Quercitrin protects human bronchial epithelial cells from oxidative damage

- Smurf2 suppresses the metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma via ubiquitin degradation of Smad2

- circRNA_0001679/miR-338-3p/DUSP16 axis aggravates acute lung injury

- Sonoclot’s usefulness in prediction of cardiopulmonary arrest prognosis: A proof of concept study

- Four drug metabolism-related subgroups of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in prognosis, immune infiltration, and gene mutation

- Decreased expression of miR-195 mediated by hypermethylation promotes osteosarcoma

- LMO3 promotes proliferation and metastasis of papillary thyroid carcinoma cells by regulating LIMK1-mediated cofilin and the β-catenin pathway

- Cx43 upregulation in HUVECs under stretch via TGF-β1 and cytoskeletal network

- Evaluation of menstrual irregularities after COVID-19 vaccination: Results of the MECOVAC survey

- Histopathologic findings on removed stomach after sleeve gastrectomy. Do they influence the outcome?

- Analysis of the expression and prognostic value of MT1-MMP, β1-integrin and YAP1 in glioma

- Optimal diagnosis of the skin cancer using a hybrid deep neural network and grasshopper optimization algorithm

- miR-223-3p alleviates TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and extracellular matrix deposition by targeting SP3 in endometrial epithelial cells

- Clinical value of SIRT1 as a prognostic biomarker in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, a systematic meta-analysis

- circ_0020123 promotes cell proliferation and migration in lung adenocarcinoma via PDZD8

- miR-22-5p regulates the self-renewal of spermatogonial stem cells by targeting EZH2

- hsa-miR-340-5p inhibits epithelial–mesenchymal transition in endometriosis by targeting MAP3K2 and inactivating MAPK/ERK signaling

- circ_0085296 inhibits the biological functions of trophoblast cells to promote the progression of preeclampsia via the miR-942-5p/THBS2 network

- TCD hemodynamics findings in the subacute phase of anterior circulation stroke patients treated with mechanical thrombectomy

- Development of a risk-stratification scoring system for predicting risk of breast cancer based on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, non-alcoholic fatty pancreas disease, and uric acid

- Tollip promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression via PI3K/AKT pathway

- circ_0062491 alleviates periodontitis via the miR-142-5p/IGF1 axis

- Human amniotic fluid as a source of stem cells

- lncRNA NONRATT013819.2 promotes transforming growth factor-β1-induced myofibroblastic transition of hepatic stellate cells by miR24-3p/lox

- NORAD modulates miR-30c-5p-LDHA to protect lung endothelial cells damage

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis telemedicine management during COVID-19 outbreak

- Risk factors for adverse drug reactions associated with clopidogrel therapy

- Serum zinc associated with immunity and inflammatory markers in Covid-19

- The relationship between night shift work and breast cancer incidence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies

- LncRNA expression in idiopathic achalasia: New insight and preliminary exploration into pathogenesis

- Notoginsenoside R1 alleviates spinal cord injury through the miR-301a/KLF7 axis to activate Wnt/β-catenin pathway

- Moscatilin suppresses the inflammation from macrophages and T cells

- Zoledronate promotes ECM degradation and apoptosis via Wnt/β-catenin

- Epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related genes in coronary artery disease

- The effect evaluation of traditional vaginal surgery and transvaginal mesh surgery for severe pelvic organ prolapse: 5 years follow-up

- Repeated partial splenic artery embolization for hypersplenism improves platelet count

- Low expression of miR-27b in serum exosomes of non-small cell lung cancer facilitates its progression by affecting EGFR

- Exosomal hsa_circ_0000519 modulates the NSCLC cell growth and metastasis via miR-1258/RHOV axis

- miR-455-5p enhances 5-fluorouracil sensitivity in colorectal cancer cells by targeting PIK3R1 and DEPDC1

- The effect of tranexamic acid on the reduction of intraoperative and postoperative blood loss and thromboembolic risk in patients with hip fracture

- Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 mutation in cholangiocarcinoma impairs tumor progression by sensitizing cells to ferroptosis

- Artemisinin protects against cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury via inhibiting the NF-κB pathway

- A 16-gene signature associated with homologous recombination deficiency for prognosis prediction in patients with triple-negative breast cancer

- Lidocaine ameliorates chronic constriction injury-induced neuropathic pain through regulating M1/M2 microglia polarization

- MicroRNA 322-5p reduced neuronal inflammation via the TLR4/TRAF6/NF-κB axis in a rat epilepsy model

- miR-1273h-5p suppresses CXCL12 expression and inhibits gastric cancer cell invasion and metastasis

- Clinical characteristics of pneumonia patients of long course of illness infected with SARS-CoV-2

- circRNF20 aggravates the malignancy of retinoblastoma depending on the regulation of miR-132-3p/PAX6 axis

- Linezolid for resistant Gram-positive bacterial infections in children under 12 years: A meta-analysis

- Rack1 regulates pro-inflammatory cytokines by NF-κB in diabetic nephropathy

- Comprehensive analysis of molecular mechanism and a novel prognostic signature based on small nuclear RNA biomarkers in gastric cancer patients

- Smog and risk of maternal and fetal birth outcomes: A retrospective study in Baoding, China

- Let-7i-3p inhibits the cell cycle, proliferation, invasion, and migration of colorectal cancer cells via downregulating CCND1

- β2-Adrenergic receptor expression in subchondral bone of patients with varus knee osteoarthritis

- Possible impact of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on suicide behavior among patients in Southeast Serbia

- In vitro antimicrobial activity of ozonated oil in liposome eyedrop against multidrug-resistant bacteria

- Potential biomarkers for inflammatory response in acute lung injury

- A low serum uric acid concentration predicts a poor prognosis in adult patients with candidemia

- Antitumor activity of recombinant oncolytic vaccinia virus with human IL2

- ALKBH5 inhibits TNF-α-induced apoptosis of HUVECs through Bcl-2 pathway

- Risk prediction of cardiovascular disease using machine learning classifiers

- Value of ultrasonography parameters in diagnosing polycystic ovary syndrome

- Bioinformatics analysis reveals three key genes and four survival genes associated with youth-onset NSCLC

- Identification of autophagy-related biomarkers in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension based on bioinformatics analysis

- Protective effects of glaucocalyxin A on the airway of asthmatic mice

- Overexpression of miR-100-5p inhibits papillary thyroid cancer progression via targeting FZD8

- Bioinformatics-based analysis of SUMOylation-related genes in hepatocellular carcinoma reveals a role of upregulated SAE1 in promoting cell proliferation

- Effectiveness and clinical benefits of new anti-diabetic drugs: A real life experience

- Identification of osteoporosis based on gene biomarkers using support vector machine

- Tanshinone IIA reverses oxaliplatin resistance in colorectal cancer through microRNA-30b-5p/AVEN axis

- miR-212-5p inhibits nasopharyngeal carcinoma progression by targeting METTL3

- Association of ST-T changes with all-cause mortality among patients with peripheral T-cell lymphomas