Abstract

Apparel has the potential to influence the external expression of wearer’s emotional state and can even empower them, making patients’ hospital wearing a crucial factor in their emotional experience and medical treatment. This study aims to investigate the emotional factors that drive patients’ behavioral responses to hospital gowns using the pleasure–arousal–dominance (PAD) model. With the survey conduction and data analysis, the results identified that the color and silhouette of hospital gowns lead to the emotional experience of arousal, while the structure leads to the emotional experience of dominance, which in turn brings patients a high sense of pleasure and further affect their acceptance and willingness to continue wearing hospital gowns. Based on the results of the research, new hospital gowns were designed and validated, which further confirmed the relationship between the attributes of hospital gowns and emotions of patients. Thus, by extending the PAD model to the context of patients’ use of hospital gowns, this study provides designers with a basis for creating emotionally driven atmosphere factors in the development of hospital gowns for the Chinese market that improve acceptance and continuation of hospital gowns, making a valuable contribution to knowledge in this field.

1 Introduction

The hospital gown refers to the apparel worn by patients during medical procedures and treatments in medical institution to provide protection, convenience, and easy cleaning for patients, as well as to identify patients as being under medical care [1]. Due to the influence of various social cultures, there are differences between the hospital gowns used by patients in domestic and foreign medical institutions. Chinese hospital gowns resembling loose pajamas with long sleeves made of soft, breathable cotton with patterns like stripes, dots, or plaid [2]. Colors used in Chinese hospital gowns are generally light, such as light blue, white, and light gray, and are proven to help stabilize patients’ emotions and moods during hospitalization [3]. It is noted that hospital gowns can vary in terms of color and pattern even within different departments and hospitals in the same country. In other countries, such as Canada and the United States, hospital gowns come in styles such as open-back robes, open-front bathrobes, and jumpsuits with button snaps, which are considered more convenient for medical procedures than those in China. The colors used in these countries are also typically light, such as light blue, light green, and pink.

Besides the various styles of hospital gowns, the existing studies also focused on their function and comfort, with attention given to the drawbacks of current designs and suggestions for improvement. For instance, hospital gowns with a pyjama style may not provide adequate ventilation when patients spend most of their time in bed, and continued moisture in certain areas can cause allergies [4]. Moreover, patients wearing hospital gowns with an open-back robe may have difficulty tying the robe at the back themselves, particularly if they have arm injuries. To address these issues, scholars have proposed alternative hospital gown designs. For example, Lam et al developed a chitosan blend knitted jersey for hospital gowns to improve ventilation, resulting in a more comfortable and dry experience for patients even after extended periods in bed [5]. Arunachalam and D’Souza proposed a one-piece gown design with overlapping panels that snap together, allowing patients to easily access the gown without assistance [6].

In addition to the function and comfort, hospital gowns are also linked to patients’ emotions. A study by Lorts has shown that wearing open-back robes with uncovered hips can make patients feel uncomfortable and awkward [7]. Topo and Iltanen-Tähkävuori found that hospital gowns can become a symbol of weakness, sickness, and poor health, triggering emotions such as annoyance, disappointment, or even depression [8]. To improve these issues, some researchers have developed comfortable and personalized hospital gowns to enhance the positive feelings of patients. For example, Kwon and Yim studied patients’ preferences for color, pattern, and texture in hospital gowns in Korea and proposed two designs to promote feelings of security and calm during medical treatments [9]. Frankel et al. focused on the privacy of patients’ bodies and developed a series of hospital gowns in different apparel structures for different diseases, resulting in patients feeling protected and secure [10]. Hwang et al. focused on the material and structure of apparel and developed a two-piece knitted maternity hospital gown that can ensure patient privacy and improve the physical and psychological comfort of patients at different stages of parturition [11]. Jha worked on the structure of apparel and has developed a hospital gown with open back and Velcro closure elements, which can be easily worn and taken off while sitting and protects privacy by reducing patients’ sense of shame and powerlessness [12]. It can be found that the existing studies more focus on discovering the impact of partial attributes of hospital gown on patients’ emotions and then propose its corresponding designs. However, these studies have not considered the most common design attributes of hospital gowns as a whole and barely pay attention to the relationship between the attributes of hospital gowns and emotional responses from patients, which makes the deficiency for theoretical foundation for emotional hospital gown design.

Even though there is no relationship between hospital gowns and emotional responses from patients, quite a few studies have covered the emotional responses modeling, which can be the fundamental for the aforementioned relationship development. Generally, there are two types of emotional modeling method. The first one is by using discrete emotion labels to establish models such as happiness, sadness, and anger. The second method involves more comprehensive multidimensional representation models such as the valence–arousal–dominance model, the evaluation–potency–activity model, and the pleasure–arousal–dominance (PAD) model [13]. Multidimensional emotional representation is more comprehensive than discrete emotion labels as it captures more fine-grained information, and discrete emotion labels can always be mapped to certain points in a multidimensional emotional space [14]. Among multidimensional representation models, PAD is quite popular. It was developed by Mehrabian and Russell, and it illustrates the emotional dimensions created by surrounding stimuli, which affect individuals’ behaviors [15,16,17]. The PAD model is mainly composed of three states: pleasure–displeasure, which refers to positive versus negative emotional states; arousal–nonarousal, which is defined in terms of the level of energized versus soporific feels; and dominance–submissiveness, which indicates the emotion of control and influence over one’s surroundings and others versus being controlled or influenced by situations and others [16]. The PAD model has been employed in many domains where human emotions need to be considered. For example, Jaeger et al. developed 24 emojis using the PAD model to measure the perceived appropriateness of foods and beverages [18]. Moreover, Hsieh et al. investigated the emotional drivers of branded app atmospherics in brand relationships by applying the PAD model [19]. Although few studies have applied the PAD model to human emotional responses to apparel, it has the potential to identify such relationships. This study aims to employ the PAD model to detect various emotional responses from patients based on their hospital wearing during their treatments.

This study applies the PAD model to examine how the attributes of hospital gowns impact patients’ emotional responses, their acceptance, and willingness to continue using them. First, we analyze the relationship between hospital gown attributes and patients’ emotional responses, and then construct hypothetical relationships between the PAD model and hospital gown attributes. Second, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM) are used to analyze the relationships. In the end, a validation scheme is designed to test these relationships. It can be noted that the developed relationship between hospital gowns and patients’ emotions can be referred to hospital gown design to improve the satisfaction of patients.

2 Research model and hypotheses

2.1 Research model

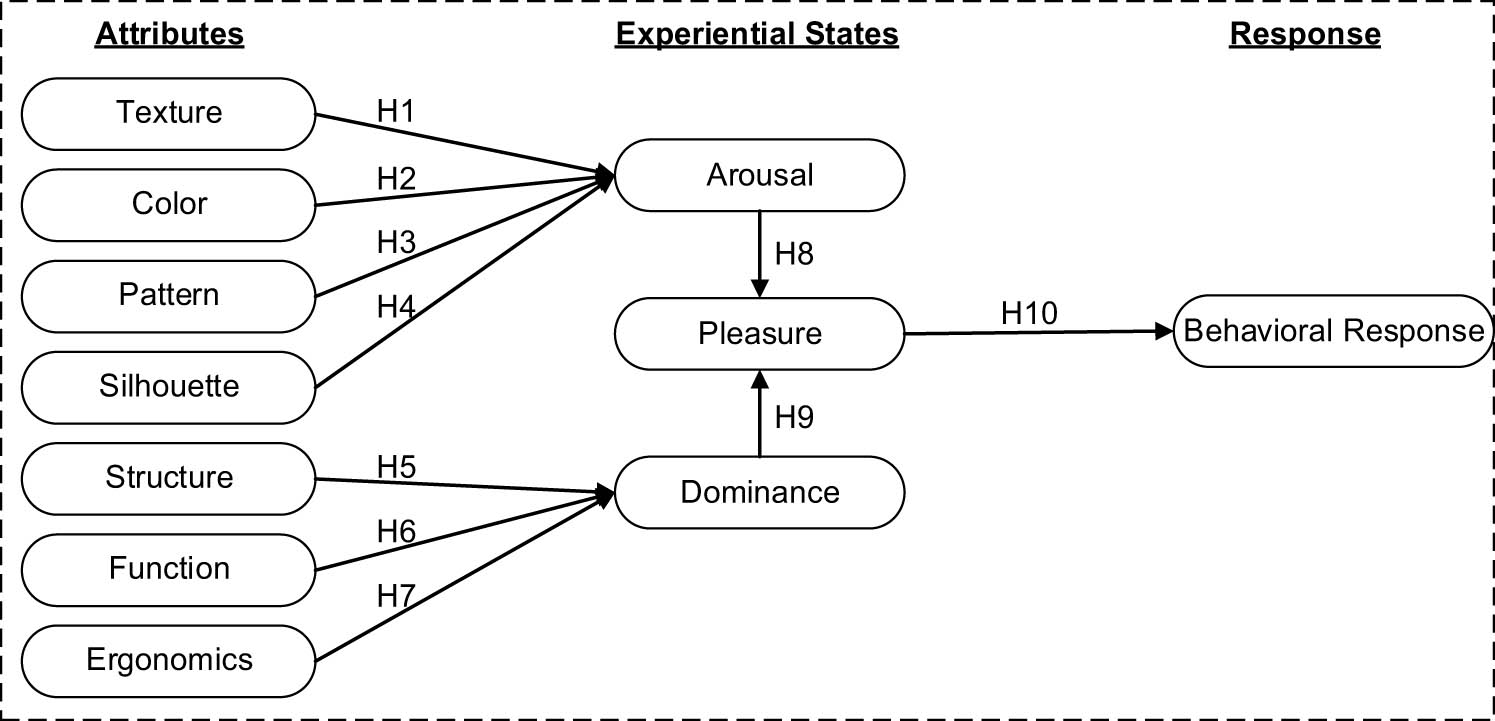

The study has conceptualized a research model by drawing from the PAD theory and design theory in the context of the hospital gown. Emotional dimensions of arousal, dominance, and pleasure created by stimuli of hospital gown attributes affect behavioral responses of patients. The very common attributes of hospital gowns are defined to include texture, color, pattern, silhouette, structure, function, and ergonomics [9,10,20,21]. Figure 1 shows the framework of the research model.

Research model.

2.2 Hypotheses

The texture of apparel refers to the surface attributes of apparel fabrics [22]. Texture of apparel conveys the visual information of apparel surface, providing a sense of touch in the mind that influences the wearer’s prediction of how comfortable the apparel will be [22]. Previous studies have shown an increasing interest in using intrinsic cues of texture to evaluate apparel quality [23,24]. By creating high-quality textured apparel, patient selection behavior can be positively influenced [24]. Patients generally prefer good texture appearing senior and gentle, and these good textures can promote patient acceptance and satisfaction toward apparel [6,20]. It is noted that apparel with quality visual texture can enhance the sense of stability and shape, have a positive visual impact on patients, and stimulate their mental vitality [25]. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1: The texture of the hospital gown is positively correlated with the arousal (A) of patient’s dress intention.

Color is one of the surface attributes s of fabrics, and it is a more obvious element of a hospital gown that can be captured by patients at the first glance [26]. The use of color cannot be separated from the emotional factors assigned to it, and the association between color and emotion is the result of people’s long-term experience and accumulation, as well as a dual reflection of historical culture and real life [27]. Kodžoman proposes that color is the primary criterion to define the visual impression of any apparel [28]. Previous studies have shown that the color of apparel can evoke emotions in patients in a hospital setting. For example, the blue and white color scheme of hospital gowns can convey a sense of comfort and healing, which can help patients to develop a calm and stable emotional state [3]. The application of color in a patient hospital gown often refers to the theory of color psychology, with the expectation of helping to alleviate psychological discomfort and even physical pain [11]. Different colors can produce different physiological and emotional effects, but they will all arouse patients’ preexisting impressions and feelings about color through the information conveyed at first glance. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: The color of the hospital gown is positively correlated with the arousal (A) of patient’s dress intention.

Pattern is another surface attribute of fabrics that can range from simple geometric shapes to complex designs. It can add interest and visual appeal to a hospital gown and also convey cultural or personal significance [9]. Hrga and Frumen have discovered that a pattern can trigger a wearer’s visual attention and recognition and can generate new feelings by combining with background information [29]. People’s perception of different patterns through vision is derived from their perception of things or psychological effects from life experiences [30]. It is noted that patients are in prolonged contact with their hospital gowns, and the pattern of the hospital gowns is an important factor that can affect their physical and mental well-being and mood [31]. After observing a pattern, it can awaken a patient’s existing experiences and subconsciously search for objects similar to that pattern to assign emotions. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: The pattern of the hospital gown is positively correlated with the arousal (A) of the patient’s dress intention.

The silhouette of apparel is a representation of its shape, encompassing the overall cut, fit, and perceived appearance of apparel [28]. A well-crafted silhouette can elicit favorable behavioral responses, such as increased favorability and willingness to wear apparel [28]. Jankovska and Park have pointed out that since patients are increasingly concerned with body shape during their hospitalization, a good design for the silhouette of a hospital gown can be an effective means of achieving this goal [32]. A carefully designed silhouette can improve the aesthetics of a hospital gown and contribute to improving a patient’s overall appearance, leading to a positive wearing experience and evoking positive emotions. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: The silhouette of the hospital gown is positively correlated with the arousal (A) of the patient’s dress intention.

The structure of apparel refers to how apparel is constructed, and it is related to the silhouette, craftsmanship, and the cutting of each individual part of apparel [33]. The design of the structure involves the modification of local structural components, adjustments to internal structural lines, and improvements to the overall shape of the apparel [34]. The structure of the apparel affects not only its appearance but also its comfort during wear [11]. The size of the structure, the positioning of the components, and the construction techniques used to assemble them all determine the balance between convenience and appearance of the apparel, which is a crucial factor in wearer’s emotional response [35]. For instance, the study by Drossman and Ruddy indicates that the back-opening structure of hospital gowns may elicit feelings of shame during medical treatment [36]. Conversely, when a hospital gown is designed to allow for free movement of the patient’s limbs during medical treatment, the dominant experience may be one of control, which can evoke positive emotions. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5: The structure of the hospital gown is positively correlated with the dominance (D) of the patient’s dress intention.

The function of apparel primarily includes its ability to protect the body in various environments, assist in daily life activities, and facilitate social interaction in group settings [37]. Hospital gowns as specific apparel must fulfill functional requirements such as effective protection and clear identification for patients in medical environments [25]. The function of hospital gowns also impacts patients’ emotions and can trigger unique cognitive responses to usage [31]. When patients perceive that hospital gowns fulfill their functional needs, their acceptance and satisfaction increase [32], and they are more likely to feel a sense of control. For instance, Chae found that by adding more pockets to hospital gowns, patients’ needs for carrying personal belongings can be met, which not only enhances satisfaction with hospital gowns but also strengthens patients’ sense of control over them [38]. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6: The function of the hospital gown is positively correlated with the dominance (D) of the patient’s dress intention.

Ergonomics in apparel design involves incorporating human-oriented details to enhance both the functional and structural effectiveness, resulting in an improved wearing experience [39]. Hospital gowns serve as a crucial medium of communication between patients and the external environment, directly impacting their sensory, psychological experiences, and emotional state [25]. When hospital gowns are well-fitted, comfortable, and easy to use, they provide patients a relaxed and easy wearing experience, leading to higher satisfaction and a sense of control [6]. For instance, the inclusion of hook and loop fasteners on hospital gowns for disabled patients allows them to put on and remove the gown independently, increasing their perceived control over the external environment [40]. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H7: The ergonomics of the hospital gown is positively correlated with the dominance (D) of the patient’s dress intention.

In the PAD model, there are three emotional states including arousal, pleasure, and dominance. Studies conducted by Kumar et al. have revealed that there is a correlation between arousal and pleasure, with arousal having a causal relationship with pleasure [41]. The level of arousal experienced by patients in a medical setting can impact their sense of pleasure, which in turn can influence their satisfaction and acceptance of the hospital gowns. Other studies have also shown that happiness has a positive effect on emotional arousal, with this effect being even more pronounced in favorable environments [42]. This positive relationship encourages patients to have positive emotional responses and enhances their level of arousal [43]. Thus, when patients experience a high level of emotional arousal, they are more likely to feel pleasant emotions and be more willing to accept hospital gowns, which can lead to their continued use.

Studies on the emotional state of dominance have indicated that perceived control can influence a person’s behavior, such as their continued use [44]. In the medical environment, patients require a greater sense of perceived control over their hospital gowns to reduce uncertainty in use and increase satisfaction [36]. This viewpoint is mainly derived from the fact that hospital gowns serve as a communication medium between patients and the external environment and need to be controllable for patients. Moreover, various studies have demonstrated that the sense of autonomy and freedom that users experience in service can largely enhance their perceived advantage, thereby allowing them to gain a sense of control and maintain a positive behavioral state [45,46]. Thus, when patients feel that they have control over the use of their hospital gowns, they are more likely to develop a liking for them and be encouraged to continue using them.

Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H8: Patients’ emotional arousal (A) is positively correlated with pleasure (P) in patients’ dress intention.

H9: Patients’ emotional dominance (D) is positively correlated with pleasure (P) in patients’ dress intention.

Pleasure can motivate patients to form an emotional connection with their hospital gowns, which can develop into acceptance and a willingness to continue using them. Emotional feedback generated by the design attributes of hospital gowns can enhance patients’ pleasure, which can then be translated into positive evaluations of the quality and satisfaction of the hospital gowns. Previous studies have shown that the greater the level of positive stimulation a service experience provides for users, the higher their satisfaction with the product [47]. Hospital gowns stimulate patients’ senses and trigger emotions, allowing them to generate positive evaluations of the hospital gowns through their pleasant emotional expressions. This, in turn, can result in positive acceptance and a willingness to continue using them. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H10: Patients’ emotional pleasure (P) is positively correlated with the behavioral responses (i.e., acceptance and willingness) in patients’ dress intention.

3 Method

3.1 Questionnaire design

The questionnaire used in this study had a specific focus on assessing emotional responses toward hospital gowns. It includes three main components: profile inquiries, a scale designed to identify attributes related to hospital gowns, and an emotional response scale. Each of these components consisted of multiple questions. The profile questions were designed to adhere to several standards for participant selection. These standards aimed to ensure participants’ hospitalization experience, duration of hospital stay, reasons for hospitalization, and the duration of hospital gown usage during their stay. These criteria were crucial in exploring existing issues and understanding the needs and preferences regarding hospital gown usage. The scale employed to identify attributes of hospital gowns consisted of seven aspects, including texture, color, pattern, silhouette, structure, function, and ergonomics. To assess the texture dimension of hospital gowns, this study used five questions adapted from the study by Cho and Kamalha et al., and to evaluate the color and structure dimensions, four questions from Edvardsson’s work were incorporated [20,48,49]. Moreover, three questions from the study by Kam and Yoo were used to measure the pattern and silhouette dimensions, and 2 and 10 questions, respectively, drawn from the studies by Hwang et al. and Arunachalam and D’Souza were employed to evaluate the ergonomic and functional dimensions [6,11,25]. Regarding the emotional response scale, it was adapted from questions applied in the study by Mehrabian et al., and emotional responses can be evaluated by using measures of pleasure, arousal, and dominance [15]. For these scales in the questionnaire, seven-point Likert scale was applied with “1” indicating strong dissatisfaction, “4” indicating neutrality, and “7” indicating strong satisfaction.

3.2 Participants

The study employed 146 healthcare workers, 124 hospitalized patients, 145 former hospitalized patients, and 5 escorts who had come into contact with or worn hospital gowns to answer the questionnaire. They are from various cities in China and included both men and women, with a wide age distribution covering all age groups. Participants aged 21–30 and 31–40 years accounted for the majority, with a total of 47.6% (199) and 24.0% (101), respectively.

3.3 Data collection

The study collected data from China involving online surveys and offline visits to healthcare institutions. Before the questionnaire survey, a preliminary experiment was designed to obtain data and feedback from 151 hospitalized patients through offline visits. According to the data obtained and participants’ suggestions, the questionnaire settings were modified, and the selection of participant was adjusted to conduct the final appropriate questionnaire survey. In the formal survey, online questionnaires (https://www.wjx.cn/vm/OpuAPNE.aspx#) were the main data collection method, with the questionnaires uploaded to communication communities of many hospitals in China and forums of relevant medical institutions. Offline visits were made to many public hospitals in southwest China. Informed consent was formally obtained from each participant before the data collection. A total of 508 questionnaires were collected. In the process of data organization and cleaning, a part of questionnaires has incomplete and invalid answers, which are excluded to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the final data. A total of 420 records were ultimately retained for data analysis.

3.4 Statistical analyses

In this study, the measurement model was assessed by examining internal consistency reliability, underlying relationships between measured variables, convergent validity, and discriminant validity using Rstudio. The internal consistency reliability for constructs was evaluated using the Cronbach’s Alpha index [50].

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to identify the underlying relationships between measured variables, where the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value, cumulative variance interpretation rate after rotation, and the p-value of Bartlett’s test were obtained [51,52]. Convergent validity and discriminant validity were evaluated using CFA, and various model fitting indices, including goodness of fit index (GFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), restricted maximum likelihood residual (RMR), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), and factor loading were obtained [53,54,55,56]. It is noted that items of variables with weak correlations were removed using the factor loading index [54,56].

Moreover, SEM was adopted for further data analysis, as it is an efficient method for multidimensional modeling and measuring inner relationships among variables, and it also aligns with the predictive and verification modeling goals of the study meets [57]. The SEM was evaluated using model fitting indices (χ 2, df, χ 2/df, GFI, CFI, TLI, RMSEA, RMR, and SRMR), modification indices (MIs), factor loading β (standardized regression coefficient), and t-value [39,54,58,59,60,61]. It is noted that modifications were made to the SEM by addressing high levels of MI [54,56].

4 Results

4.1 Measurement model

The study conducted an internal reliability analysis for the survey data, indicating good reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.925 for the overall scale and values ranging from 0.637 to 0.907 for each dimension of hospital gowns and measures of PAD, respectively [50]. EFA indicated good correlation between variables and factors, with a KMO value of 0.893 and a cumulative variance interpretation rate of 65.826% after rotation, surpassing the recommended thresholds of 0.6 and 50%, respectively [51,52]. However, the indices of CFA did not initially meet the required criteria, with values falling below GFI > 0.9, RMR < 0.05, TLI > 0.9, AVE value > 0.5, CR value > 0.7, and factor loading > 0.6 [53,54,55,56]. It is noted that a factor loading between 0.4 and 0.6 can still be acceptable in a construct despite the correlation not being particularly strong [62]. Items with a factor loading less than 0.4 indicate a weak correlation between the factors, and then two items of color, two items of structure, one item of texture, and one item of silhouette were considered to be removed, and the CFA was re-run with modifications to improve fit indices (Table 1). The improved results showed good fit (χ 2/df = 2.750, GFI = 0.901, RMSEA = 0.065, RMR = 0.039, CFI = 0.922, TLI = 0.931, and SRMR = 0.058). The subsequent study was based on these improved variables.

Measurement model evaluation

| Item | Loading |

|---|---|

| Function ( α = 0.907, CR = 0.908, AVE = 0.499) | |

| Hospital gowns can effectively conceal privacy and protect the body from external harm (Protection) | 0.803*** |

| Hospital gowns are easy to put on and take off, to treat and to move around (Convenience) | 0.645*** |

| Hospital gowns are easy to keep clean and hygienic (antifouling) | 0.699*** |

| Hospital gowns are well ventilated and easy to absorb moisture and perspiration (hygroscopicity) | 0.678*** |

| Hospital gowns are not easy to be contaminated with dust, antimite, and not easy to cause allergy (anti-allergic) | 0.706*** |

| The fabric of the hospital gowns can inhibit the growth of bacteria (bacteriostatic) | 0.656*** |

| Hospital gowns are not easy to wrinkle and can be quickly restored and leveled. (Wrinkle resistance) | 0.729*** |

| Hospital gowns are not easy to static electricity, which will not affect the use of specific instruments (antistatic) | 0.705*** |

| Repeated rubbing and washing of hospital gowns without ball (abrasion resistance) | 0.723*** |

| Hospital gowns are easy to identify patients (identification) | 0.707*** |

| Ergonomics (α = 0.653, CR = 0.658, AVE = 0.491) | |

| The size of the hospital gowns are suitable and comfortable to wear (Size) | 0.743*** |

| Fine workmanship of hospital gowns, not shell-off, not pricking (Technology) | 0.655*** |

| Structure (α = 0.642, CR = 0.660, AVE = 0.330) | |

| The structure of the hospital gowns is one piece. | 0.637*** |

| The structural lines of the hospital gowns are fine and neat, including split lines, stamped lines, wrapping lines, etc. | 0.784*** |

| Texture (α = 0.844, CR = 0.846, AVE = 0.528) | |

| The hospital gowns are flexible and has a strong sense of flowing lines | 0.863*** |

| The thickness of the hospital gowns are moderate and the fabric is opaque | 0.764*** |

| The hospital gowns have a good sense of crispness and stable modeling effect | 0.665*** |

| The luster of the hospital gowns are moderate and the visual feeling is soft | 0.729*** |

| Silhouette (α = 0.662, CR = 0.666, AVE = 0.400) | |

| The silhouette of the hospital gowns are in the shape of a straight, neat line (H-shaped) | 0.601*** |

| The silhouette of the hospital gowns are a generous and strong inverted trapezoid (T-shaped) | 0.613*** |

| Pattern (α = 0.637, CR = 0.650, AVE = 0.383) | |

| Natural themes: plants, flowers, cartoons, etc. | 0.616*** |

| Geometric themes: wave points, squares, stripes, etc. | 0.610*** |

| Arrangement: space blank, wide spacing. | 0.636*** |

| Color (α = 0.646, CR = 0.696, AVE = 0.404) | |

| The overall color of the hospital gowns are warm with dark | 0.820*** |

| The overall color of the hospital gowns are cool with dark | 0.779*** |

| Item | Loading |

| Pleasure (α = 0.879, CR = 0.882, AVE = 0.653) | |

| Unhappy - Happy | 0.879*** |

| Melancholic - Contented | 0.709*** |

| Despairing - Hopeful | 0.814*** |

| Annoyed - Pleased | 0.822*** |

| Arousal (α = 0.778, CR = 0.779, AVE = 0.469) | |

| Sleepy - Wide-awake | 0.622*** |

| Calm - Excited | 0.694*** |

| Relaxed - Stimulated | 0.680*** |

| Dull - Jittery | 0.737*** |

| Dominance (α = 0.798, CR = 0.800, AVE = 0.500) | |

| Controlled - Controlling | 0.726*** |

| Submissive - Dominant | 0.642*** |

| Awed - Important | 0.705*** |

| Influenced - Influential | 0.752*** |

| Behavioral responses (α = 0.642, CR = 0.644, AVE = 0.475) | |

| How would you like to wear a hospital gown while in the hospital? (Acceptance intention) | 0.701*** |

| How acceptable is it for you to wear a hospital gown continuously while in hospital? (Continuous usage intention) | 0.678*** |

Notes: CR, composite reliability.

***p < 0.001; standardized factor loadings are reported.

4.2 Structural equation modeling

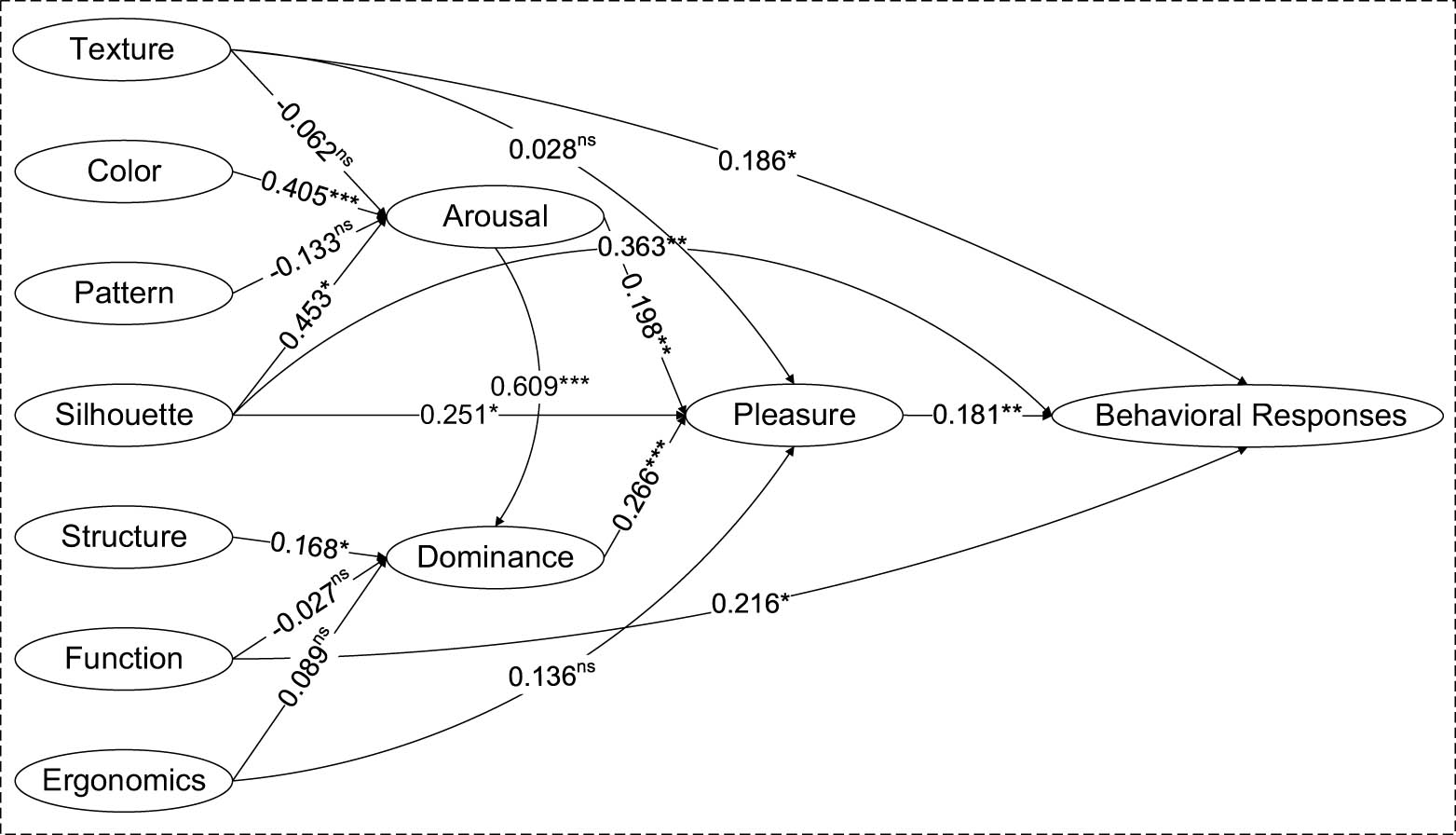

SEM was used to test the hypotheses, with criteria for fit indices including χ 2/df < 3, GFI > 0.9, CFI > 0.9, TLI > 0.9, RMSEA < 0.1, RMR < 0.05, and SRMR < 0.10 [39,54,58,59,60,61]. The preliminary SEM results (χ 2 = 2109.669, df = 671, χ 2/df = 3.144, GFI = 0.776, CFI = 0.813, TLI = 0.793, RMSEA = 0.072, RMR = 0.215, SRMR = 0.1) did not meet the criteria, which may contain correlations that have been ignored. Thus, the model was modified by using MI to identify high levels, variables and items with MI greater than 20, and a free parameter using covariance [53,54,56]. The improved SEM model, as shown in Figure 2, had good fit indices (χ 2 = 1211.414, df = 634, χ 2/df = 1.911, GFI = 0.910, CFI = 0.925, TLI = 0.912, RMSEA = 0.047, RMR = 0.047, SRMR = 0.056). The SEM results validated the hypotheses (Table 2): H1 (β = −0.062, p > 0.05), H2 (β = 0.405, p < 0.001), H3 (β = −0.133, p > 0.05), H4 (β = 0.453, p < 0.001), H5 (β = 0.168, p < 0.05), H6 (β = −0.027, p > 0.05), H7 (β = 0.089, p > 0.05), H8 (β = 0.198, p < 0.05), H9 (β = 0.266, p < 0.001), and H10 (β = 0.181, p < 0.05). As shown in Table 2, the absolute values of β (standardized regression coefficients) among the hypotheses are all greater than 0.02, indicating relatively favorable explanatory ability [59,63]. The plus or minus sign of the β can reflect the positive and negative relationship between variables [63]. For instance, p < 0.05 and t-value ≥ 1.96 indicate that the relationship supported by the model is valid [63]. However, other insignificant correlations are not supported by the model.

Hypotheses test results. *p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; ns = not significant.

Result of structural model

| Hypotheses | Path | β | t-value | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Texture | → | Arousal | −0.062ns | −0.602 | Not supported |

| H2 | Color | → | Arousal | 0.405*** | 5.234 | Supported |

| H3 | Pattern | → | Arousal | −0.133ns | −1.628 | Not supported |

| H4 | Silhouette | → | Arousal | 0.453* | 3.687 | Supported |

| H5 | Structure | → | Dominance | 0.168* | 2.444 | Supported |

| H6 | Function | → | Dominance | −0.027ns | −0.467 | Not supported |

| H7 | Ergonomics | → | Dominance | 0.089 ns | 1.418 | Not supported |

| H8 | Arousal | → | Pleasure | 0.198** | 2.738 | Supported |

| H9 | Dominance | → | Pleasure | 0.266*** | 3.780 | Supported |

| H10 | Pleasure | → | Behavioral response | 0.181** | 2.804 | Supported |

| — | Texture | → | Pleasure | 0.028ns | 0.357 | — |

| — | Texture | → | Behavioral response | 0.186* | 2.007 | — |

| — | Silhouette | → | Pleasure | 0.251* | 2.502 | — |

| — | Silhouette | → | Behavioral response | 0.363** | 2.727 | — |

| — | Function | → | Behavioral response | 0.216* | 2.461 | — |

| — | Ergonomics | → | Pleasure | 0.136ns | 1.683 | — |

| — | Arousal | → | Dominance | 0.609*** | 8.850 | — |

Notes. β, standardized regression coefficient.

*p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; ns = not significant.

Therefore, based on the structural model assessment, only six hypotheses (H2, H4, H5, H8, H9, and H10) were statistically proved to be significant, as they followed the t-value of greater than 1.96 and p < 0.05. Meantime, β are all plus sign, indicating a positive correlation. Specifically, the results indicated that patients’ arousal is associated with the color (H2) and silhouette (H4) of their hospital wear, while the association with texture (H1) and pattern (H3) could not be supported. Patients’ hospital wear structure (H5) is associated with dominance, but the correlation with function (H6) and ergonomics (H7) could not be supported. Arousal (H8) and dominance (H9) are associated with pleasure, which is also associated with Response (H10).

Furthermore, based on Table 2, several extended correlations are funded as well. In Table 2, the absolute values of all β are all greater than 0.02, the t-values are all greater than 1.96, and p < 0.05, indicating the significant correlations. These correlations with plus β include that patients’ hospital gown texture is positively linked with behavioral response, patients’ hospital gown silhouette is positively associated with pleasure and behavioral response, patients’ hospital gown function is positively linked with behavioral response, and patients’ arousal is positively associated with dominance.

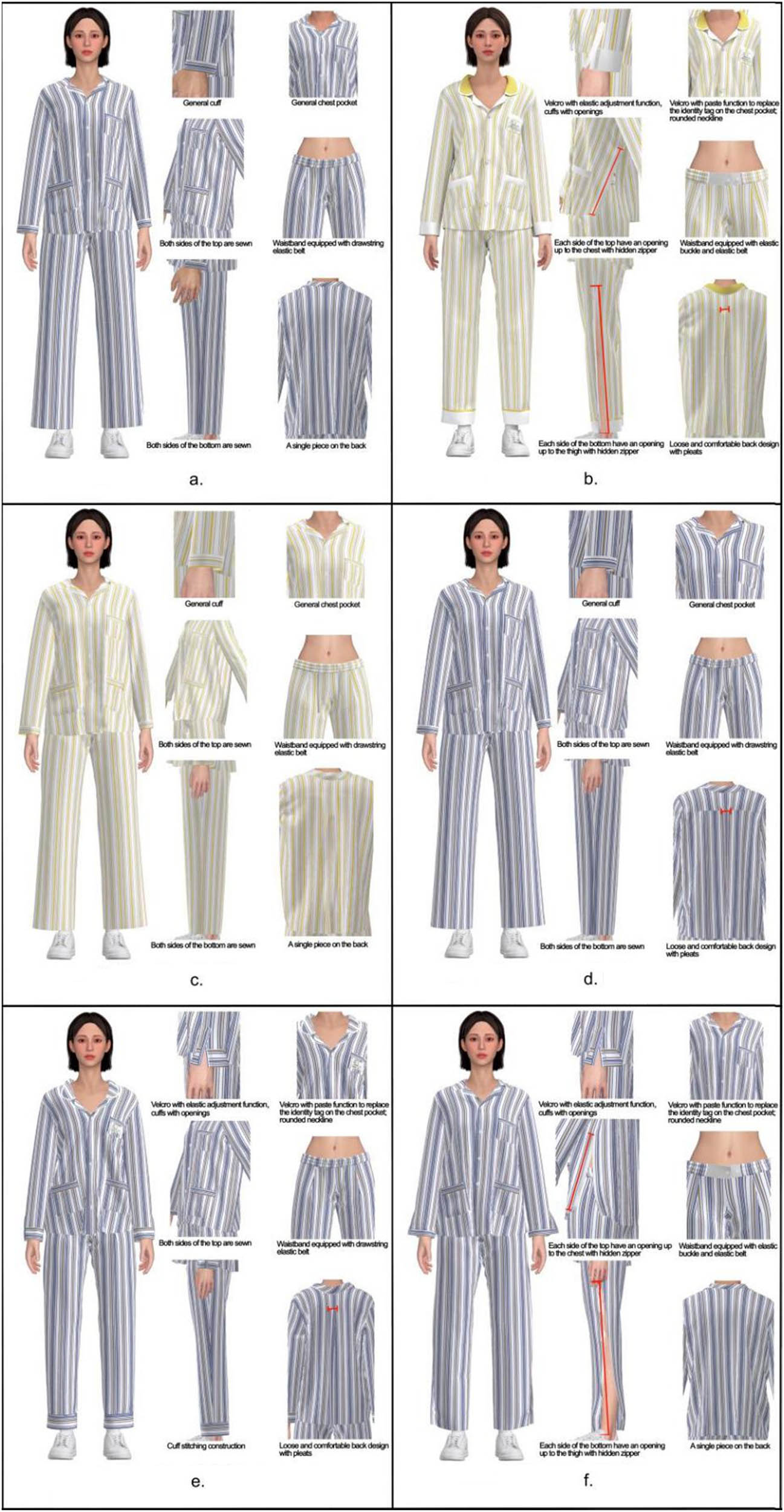

5 Validation

In this section, an experiment was described to validate the hypotheses supported by the model (SEM). The general method for validation is to develop a test bed in which participants will comment on a general hospital gown that commonly worn in Chinese hospitals and new hospital gowns designed based on the aforementioned supported hypotheses of attributes (color, silhouette, and structure) and extended correlation of attributes (function) through CAD (Figure 3). It is noted that for all the participants, texture promoted positive emotions, while function remained controversial; thus, this study excluded texture in the validation. The participants will first rate their positive emotions toward the attributes of the general hospital gown, then the new hospital gowns will be created according to the supported hypotheses and the participants will rate the attributes of new hospital gowns. Finally, the scores of general hospital gown and new hospital gowns rating by participants will be applied in the PAD model and compared to see whether the hospital gowns designed based on each supported hypothesis can promote the positive emotions.

3D model of the hospital gown in the questionnaire. (a) General hospital gown, (b) new hospital gown (improve all design attribute), (c) new hospital gown (only improve the color attribute), (d) new hospital gown (only improve the silhoueete attribute), (e) new hospital gown (only improve the structure attribute), and (f) new hospital gown (only improve the function attribute).

In particular, in this tested, 14 healthcare workers, 47 hospitalized patients, and 27 former hospitalized patients were invited to participate in the experiment. The reasons for recruiting the participants are as follows: (1) The participants are mostly from the previous questionnaire who well understand this research; and (2) the participants cover all age groups as well as both genders, which mainly range from 21 to 40 years old accounted for the majority. Each of them was asked to fill out a questionnaire regarding the general hospital gown and new hospital gowns. The questionnaire contained a scale to identify attributes of hospital gowns and an emotional response scale resemble to the previous questionnaire in Section 3.1 with seven-point Likert scale and figures of general hospital gown and new hospital gowns. The participants were asked to rate their positive emotions toward the general hospital gown and new hospital gowns (Figure 3). In total, there were six sets of data for rating concerning six types of hospital gowns (one general hospital gown and five new hospital gowns).

The next step was to use each set of rating data as the input for the PAD model to obtain the positive emotions of patients toward different attributes of general hospital gown and new ones concerning the hypotheses, respectively. At this point, by comparing the results of PAD model, the effectiveness of the new hospital gowns supported by the hypotheses can be determined.

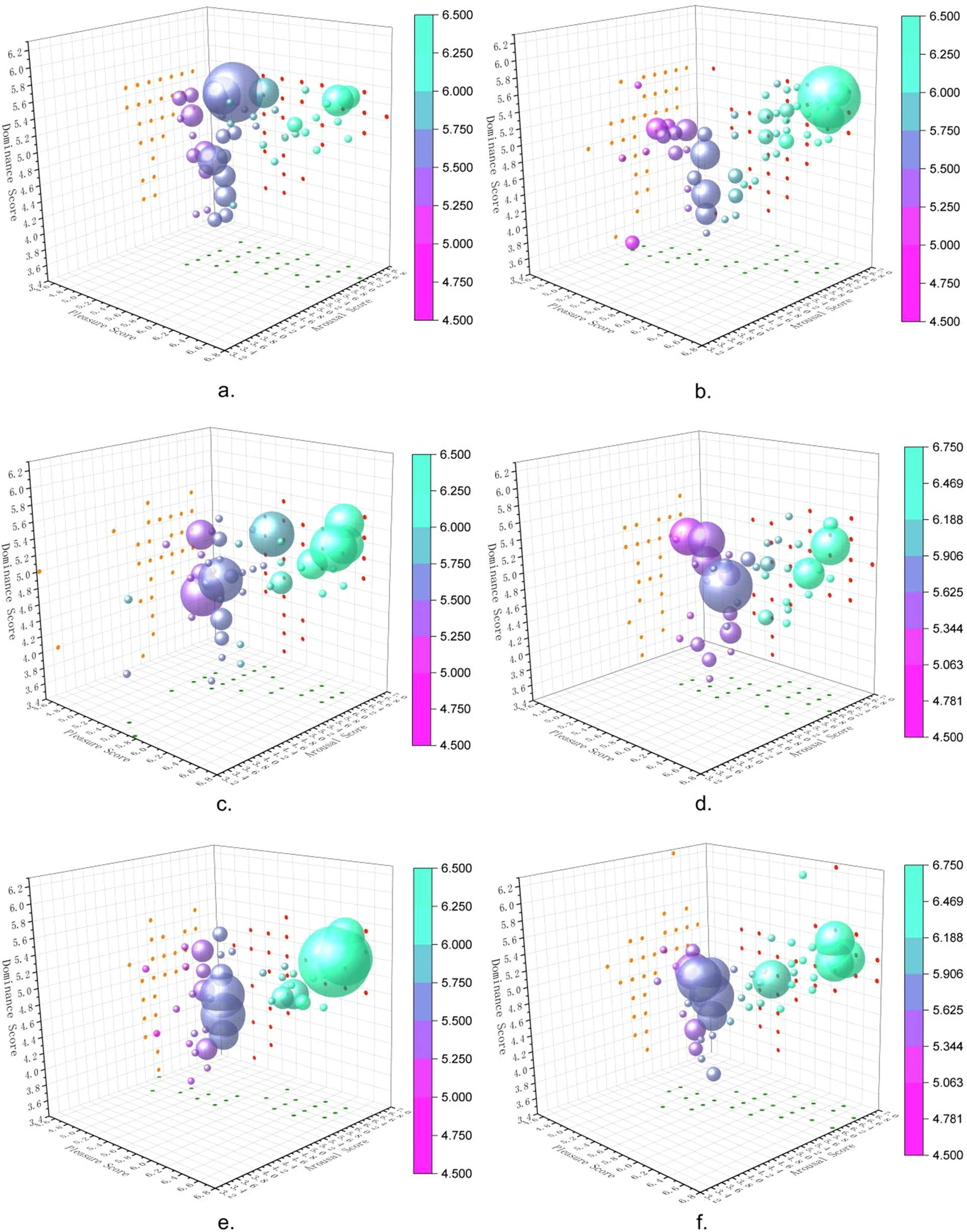

Figure 4 displays the scatter plot representing participants’ PAD dimensions, where larger bubble sizes indicate a greater number of individuals sharing exactly the same PAD data, aggregated to form larger bubbles. By comparing Figure 4a and b, it shows the positive emotions of participants toward the general hospital gown and new hospital gown (improve all design attributes) designed based on supported hypothesis of color, silhouette, structure, and function attributes. It is noted that the scatters in Figure 4b mostly gather in the positions with high scores for pleasure, arousal, and dominance, indicating that the new hospital gown designed based on color, silhouette, structure, and function leads to positive emotions among most participants, and validating that these attributes are positively correlated with emotions. By comparing Figure 4a and c, it shows the positive emotions of participants toward the general hospital gown and new hospital gown (only improve the color attribute) designed based on supported hypothesis of color attribute. It is noted that the scatters in Figure 4c mostly gather in the positions with high scores for arousal, indicating that the new hospital gown designed based on color leads to positive arousal emotions among most participants, and validating that color is positively correlated with arousal, that is, H2 hold true. By comparing Figure 4a and e, it shows the positive emotions of participants toward the general hospital gown and new hospital gown (only improve the silhouette attribute) designed based on supported hypothesis of silhouette attribute. It is noted that the scatter in Figure 4d mostly gather in the positions with high scores for arousal, indicating that the new hospital gown designed based on structure improves most participants’ emotion of arousal, validating that structure is positively correlated with arousal, that is, H4 holds true. By comparing Figure 4a and d, it shows the positive emotions of participants toward the general hospital gown and new hospital gown (only improve the structure attribute) designed based on supported hypothesis of structure attribute. It is noted that the scatters in Figure 4e mostly gather in the positions with higher scores for dominance, indicating that the new hospital gown designed based on structure enhances most participants’ sense of control and dominance, and validating that structure is positively correlated with dominance, that is, hypothesis H5 holds true. By comparing Figure 4a–f, it shows the positive emotions of participants toward the general hospital gown and new hospital gown (only improve the function attribute) designed based on supported hypothesis of function attribute. It is noted that the scatters in Figure 4f mostly gather in the positions with high scores for pleasure and arousal, and a small group of them gather in the position with high scores in dominance, indicating that the new hospital gown designed based on function attributes improves most participants’ perception of pleasure and arousal, while having a lower perception of dominance, validating that the function of hospital gowns is positively correlated with the pleasure, arousal and dominance, thus behavioral response of patients.

3-D scatter plots of participants’ PAD dimensions. (a) General hospital gown, (b) new hospital gown (improve all design attribute), (c) new hospital gown (only improve the color attribute), (d) new hospital gown (only improve the silhoueete attribute), (e) new hospital gown (only improve the structure attribute), and (f) new hospital gown (only improve the function attribute).

Therefore, all the new hospital gowns designed based on each attribute (color, silhouette, structure, and function) improved the positive emotions of most participants in all dimensions (pleasure, arousal, dominance and behavioral response), and H2, H4 as well as H5 supported by the model were validated, so as the additional relationships between hospital gowns and function.

6 Conclusion and discussion

The aim of this study is to develop the causal relationship linking the attributes of hospital gowns to patient behavioral responses, from the perspective of the patient’s emotional response. Previous studies on patients’ hospital gown have mainly focused on functional or aesthetic aspects to explore patient acceptance and continued usage intentions. However, despite the significance of emotional factors for patients, the analysis of emotional responses to hospital gown attributes has been limited. Drawing on apparel composition theory and the PAD theory, this study reveals and validates the causal relationship by which apparel attributes (i.e., function, ergonomics, structure, silhouette, pattern, color, and texture) trigger patients’ emotional responses (i.e., pleasure, arousal, and dominance) and determine their behavioral responses. This research contributes to theoretical and practical guidance by extending the application of PAD theory to hospital gown design, providing insights for designers to create hospital gowns that increase patients’ emotional satisfaction. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed in the following sections.

6.1 Theoretical implications

This study offers several theoretical contributions. First, the present study expands on how patients’ emotional experience of dominance in hospital gowns is influenced by attributes of hospital gowns including structure, function, and ergonomics. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of proper apparel structure in promoting patient self-esteem and control of dressing hospital gowns [10,11]. In addition to that, our study offers a more confirmed view by showing that hospital gown structure can encourage patients to experience dominant emotions, while function plays a key role in driving patient behavioral responses. By designing apparel with a reasonable structure that accurately conforms to the body’s contours and meets patients’ aesthetic and comfort needs, healthcare providers can promote patients’ experience of dominant emotions, as well as their acceptance and continued use of the apparel. This finding is consistent with the results of the study by Arunachalam and D’Souza [6]. Moreover, our study highlights the importance of function as a driver of patient behavioral responses. The functional attributes of hospital gowns are critical in meeting patients’ psychological needs for decent apparel and reliable use, which in turn affect their acceptance and continued use of the apparel. This finding is consistent with the previous study on the decisive factors of apparel selection [32]. In conclusion, this study contributes to the understanding of the attributes of hospital gowns that drive dominant emotions by demonstrating that the structure of hospital apparel can enhance patients’ emotional experience of control, leading to greater acceptance and continued usage of hospital attire. Moreover, this study verifies that the function of hospital gown can directly influence patients’ behavioral responses.

Second, this study has demonstrated that color and silhouette play a critical role in triggering patients’ emotional experience of arousal and behavioral responses. This finding is in line with the previous studies, indicating that the comfort level of color matching and the type of silhouette can stimulate and influence people’s emotions [27]. Moreover, Agarwal pointed out that color and silhouette directly impact the selection of apparel, and apparel designs with proper color and silhouette are more preferred [64]. On the basis of this finding, the present study reveals that color and silhouette can lead to the emotional experience of arousal, which in turn results in a higher sense of pleasure for patients, influencing their acceptance and willingness to continue wearing hospital gowns. Previous studies have suggested that the color may comfort patients from a psychological perspective, while the silhouette can affect the sense of patient’s body shape and practicality of hospital gown. Thus, they two were able to improve patients’ willingness of use and satisfaction toward hospital gown [3]. The current study provides a more comprehensive view to reveal that color and silhouette are the driving forces behind patient behavioral responses, and that emotional arousal is also a crucial attribute of the hospital gown experience, which in turn promotes the feeling of pleasure.

Third, this study demonstrates that both texture and function play key roles in shaping patient behavioral responses. Prior research has indicated that hospital gowns that meet patients’ needs and provide a high-quality visual sense of fabric can increase patient satisfaction and willingness to continue wearing those [11]. Our findings align with those of Hwang et al., who identified function and texture as the primary factors influencing patient use and visual perception. However, this study expands upon previous research by revealing the specific components that drive hedonic experiences and enhance the emotional experience of pleasure, namely, texture and function. A well-designed, functional, and humanized hospital gown can contribute to patient acceptance and continued use, thereby fulfilling their psychological need for a decent and reliable dress code.

Finally, this study proposes a comprehensive framework for identifying the key factors that drive emotional responses in patients with PAD and provides evidence supporting it. The results demonstrate that dominance and arousal are critical factors that lead to pleasure and drive patient behavioral responses to the hospital gown. These findings validate previous studies on PAD models [30,45]. Moreover, the study found that patients who have control over the wearing and taking off of hospital gowns and have gowns that are ergonomically designed for them hold positive behavioral feedback about hospital gown acceptance and continued use. In addition, the study found that arousal is positively associated with dominance and pleasure, which is in line with the findings of Şahin and Güzel [65]. As emotional arousal increases, patients feel a sense of control over their emotions.

6.2 Practical implications

This study reveals the importance of the emotions induced by the design attributes of patients’ hospital gown in driving positive outcomes and validates its usability. For hospital gown designers and hospital managers, these findings provide valuable insights into how to enhance patient acceptance and continued use of hospital gowns by improving their designs.

First, it is essential for designers to enhance patients’ sense of control and dominance when wearing hospital gowns, which can be achieved by improving the structure of the gown designs. Hospital gowns can be designed to provide patients with a convenient structure that makes it easy to put on and take off. Even when mobility is limited, patients can still put on and take off the gown themselves or with assistance from others. For example, the hospital gown for orthopedic patients can have a Velcro opening at the injured site that can be partially opened and closed to reduce the difficulty of putting on and taking off [31]. Moreover, hospital gowns can be designed with pockets for medical instruments and openings for medical examinations. For instance, patients may have indwelling needles in their wrists, necks, or waists, and small pockets in the gown can hold the exposed tube heads when not in use. The humanized structure is developed to facilitate medical rescue while protecting personal privacy.

Second, it is important for designers to create emotionally arousing experiences that can stimulate positive feelings in the patient. This can be achieved by improving the color and silhouette of the hospital gown. Designers can add visual appeal by using warm colors and designing silhouettes that trim the waist-to-hip ratio. Warm colors have been shown to provide comfort, warmth, and understanding, while a well-contoured body shape can help conceal figure flaws. These infectious colors and contoured shapes can suggest a positive mental state for the patient. For example, cancer patients may put more effort into grooming themselves with bright colors or wearing “normal” clothes to cover blemishes [66]. Furthermore, hospital administrators can standardize the colors and fine-tune the outline of apparel for different departments to meet the shape requirements of patients with different conditions, thus enhancing the positive experience of wearing the apparel. For instance, obstetric hospital gown may extend the waist silhouette and include straps on either side of the waist to adjust to the changing body shape during pregnancy.

Third, designers need to aim for positive behavioral responses from patients, which can be achieved through improving the texture and function of the hospital gown. High-quality texture can enhance the seniority and gentleness of the hospital gown, and full function can meet a variety of needs of patients. Gordon and Guttmann suggest that users can choose delicate and soft textures and gowns with privacy and hygiene protection function to enhance the haptic and visual senses of a hospital gown [67]. To effectively develop hospital gowns, designers should experience and investigate patients’ wearing issues in a hospital setting. Through interviewing patients about their feelings while wearing hospital gowns, Syed et al. identified five factors that hospital gown development should focus on utility, economy, comfort, dignity, and aesthetics [68]. Therefore, it is important to understand the detailed needs of patients in the application of patient gowns and conduct a good design to elicit positive behavioral responses from patients.

6.3 Limitations and future research

This study has three main limitations that present opportunities for further research. First, the data used in this study were collected from specific regions of China, and future studies could expand and refine the sample size collected in each region to improve the breadth and precision of the geographical distribution of the data. Meanwhile, due to the limitation of the total number of patients’ participants being younger than 21 years, and the willingness of participants older than 40 years, a majority of individuals aged 21–40 years participated in this study for model development. This demographic skew might not fully represent the perspectives of various age groups, and the future work will overcome these issues and try to cover more various groups of individuals. Second, the data were collected through an online survey method, which has its limitations. Third, the study used cross-sectional data to understand patients’ perceptions and behavior, limiting the understanding of internal changes. As patients’ emotional responses to wear hospital gowns are constantly changing with the evolving social developments and the spatial and temporal contexts, such as the color and function of the gown, future studies should adopt a longitudinal design to test this research model and improve the representativeness of data and the conclusiveness of the findings. Finally, the study did not consider the effect of personality factors on the emotional response to hospital gowns. Since patient preferences and acquired experiences with hospital gowns are influenced by unique personality traits, patient personality factors can affect emotional responses. Therefore, future studies could consider adding patient personality factors to the study of the emotionality of hospital gowns.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the hospitals and staff who took part in the research. The study was supported by the Humanities and Social Science Funds of the Ministry of Education (grant no. 21YJCZH239), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant no. SWU2109241), and the Innovation Research 2035 Pilot Plan of Southwest University (grant no. SWUPilotPlan027).

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Jenkinson, H., Wright, D., Jones, M., Dias, E., Pronyszyn, A., Hughes, K., et al. (2006). Prevention and control of infection in non-acute healthcare settings. Nursing Standard, 20(40), 56–63.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Liu, L., Zhao, H., Lu, G., Ling, Y., Jiang, L., Cai, H., et al. (2016). Attitudes of hospitalized patients toward wearing patient clothing in Tianjin, China: A cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 3(4), 390–393.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Feng, Y., Qu, M. (2022). Interference effects of spatial color design in community healthcare environments during epidemic. Forest Chemicals Review, 4(18), 2434–2442.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Boyce, J. M., Pittet, D. (2002). Guideline for hand hygiene in health-care settings: Recommendations of the healthcare infection control practices advisory committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA hand hygiene task force. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 23(S12), S3–S40.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Lam, N. Y. K., Zhang, M., Yang, C., Ho, C. P., Li, L. (2018). A pilot intervention with chitosan/cotton knitted jersey fabric to provide comfort for epidermolysis bullosa patients. Textile Research Journal, 88(6), 704–716.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Arunachalam, P., D’Souza, B. (2022). Patient-centered hospital gowns: A novel redesign of inpatient attire to improve both the patient and provider experience. Frontiers in Biomedical Devices. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, New York.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Lorts, A. (2022). Hospital gowns in the health care system: A study exploring whether the hospital gown preserves a patient’s dignity, modesty, and comfort. Doctoral dissertation, University of Missouri-Columbia.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Topo, P., Iltanen-Tähkävuori, S. (2010). Scripting patienthood with patient clothing. Social Science & Medicine, 70(11), 1682–1689.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Kwon, J., Yim, E. (2019). Analyzing the pattern design of patient gowns of domestic general hospitals. Fashion & Textile Research Journal, 21, 390–400. The Korean Society for Clothing Industry.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Frankel, R., Peyser, A., Farner, K., Rabin, J. M. (2021). Healing by leaps and gowns: A novel patient gowning system to the rescue. Journal of Patient Experience, 8, 23743735211033152.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Hwang, C., McCoy, L., Shaw, M. R. (2022). Redesigning maternity hospital gowns. Fashion Practice, 14, 1–20.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Jha, S. (2009). Exploring design requirements for a functional patient garment: Hospital caregivers’ perspective. Master’s thesis, North Carolina State University.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Li, M., Lu, Q., Long, Y., Gui, L. (2017). Inferring affective meanings of words from word embedding. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, 8(4), 443–456.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Sam Abraham, S., VL, L., Gangan, M. P. (2022). Readers’ affect: Predicting and understanding readers’ emotions with deep learning. Journal of Big Data, 9(1), 1–31.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Mehrabian, A., Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology. The MIT Press, Cambridge.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Mehrabian, A. (1996). Pleasure-arousal-dominance: A general framework for describing and measuring individual differences in temperament. Current Psychology, 14(4), 261–292.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Mehrabian, A. (1995). Framework for a comprehensive description and measurement of emotional states. Genetic, Social and General Psychology Monographs, 121(3), 339–361.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Jaeger, S. R., Jin, D., Ryan, G. S., Schouteten, J. J. (2021). Emoji for food and beverage research: Pleasure, arousal and dominance meanings and appropriateness for use. Foods, 10(11), 2880.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Hsieh, S. H., Lee, C. T., Tseng, T. H. (2021). Branded app atmospherics: Examining the effect of pleasure–arousal–dominance in brand relationship building. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 60, 102482.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Cho, K. (2006). Redesigning hospital gowns to enhance end users’ satisfaction. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 34(4), 332–349.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Park, J. (2014). Development of an integrative process model for universal design and an empirical evaluation with hospital patient apparel. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 7(3), 179–188.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Stanes, E. (2019). Clothes-in-process: Touch, texture, time. Textile, 17(3), 224–245.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Rahman, O., Koszewska, M. (2020). A study of consumer choice between sustainable and non-sustainable apparel cues in Poland. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 24(2), 213–234.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Jung, H. J., Choi, Y. J., Oh, K. W. (2020). Influencing factors of chinese consumers’ purchase intention to sustainable apparel products: Exploring consumer “attitude–behavioral intention” gap. Sustainability, 12(5), 1770.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Kam, S., Yoo, Y. (2021). Patient clothing as a healing environment: A qualitative interview study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), 5357.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Yang, S., Pan, Z., Amert, T., Wang, K., Yu, L., Berg, T., et al. (2018). Physics-inspired garment recovery from a single-view image. ACM Transactions on Graphics, 37(5), 1–14.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Elliot, A. J. (2019). A historically based review of empirical work on color and psychological functioning: Content, methods, and recommendations for future research. Review of General Psychology, 23(2), 177–200.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Kodžoman, D. (2019). The psychology of clothing: Meaning of colors, body image and gender expression in fashion. Textile & Leather Review, 2(2), 90–103.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Hrga, I., Frumen, T. (2021). Costume as a shared sensorial experience. Studies in Costume & Performance, 6 (2), 217.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Kumar, K. S., Bai, M. R. (2020). Deploying multi layer extraction and complex pattern in fabric pattern identification. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 79(15–16), 10427–10443.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Morton, L., Cogan, N., Kornfält, S., Porter, Z., Georgiadis, E. (2020). Baring all: The impact of the hospital gown on patient well-being. British Journal of Health Psychology, 25(3), 452–473.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Jankovska, D., Park, J. (2019). A mixed-methods approach to evaluate fit and comfort of the hospital patient gown. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 12(2), 189–198.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Rybicki, M. (2004). A concept for identifying and describing apparel structure. Fibres & Textiles in Eastern Europe, 12(1), 53–57.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Fontana, M., Rizzi, C., Cugini, U. (2005). 3D virtual apparel design for industrial applications. Computer-Aided Design, 37(6), 609–622.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Huang, X., Kettley, S., Lycouris, S., Yao, Y. (2023). Autobiographical design for emotional durability through digital transformable fashion and textiles. Sustainability, 15(5), 4451.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Drossman, D. A., Ruddy, J. (2020). Improving patient-provider relationships to improve health care. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 18(7), 1417–1426.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Karim, N., Afroj, S., Lloyd, K., Oaten, L.C., Andreeva, D. V., Carr, C., et al. (2020). Sustainable personal protective clothing for healthcare applications: A review. ACS Nano, 14(10), 12313–12340.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Chae, M. (2020). A needs analysis approach: An investigation of clothing for women with chronic neurological disorders. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 13(2), 213–220.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Cheng, C., Wu, H. (2017). Confidence intervals of fit indexes by inverting a bootstrap test. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 24(6), 870–880.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Rao, V. (2022). Review on application of” functional, expressive, and aesthetic consumer needs model” in designing patient gowns. Journal of Textile & Apparel Technology & Management, 12(3), 1–15.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Kumar, S., Jain, A., Hsieh, J. K. (2021). Impact of apps aesthetics on revisit intentions of food delivery apps: The mediating role of pleasure and arousal. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 63, 102686.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Ryu, K., Kim, H. J., Lee, H., Kwon, B. (2021). Relative effects of physical environment and employee performance on customers’ emotions, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions in upscale restaurants. Sustainability, 13(17), 9549.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Soma, C. S., Baucom, B. R., Xiao, B., Butner, J. E., Hilpert, P., Narayanan, S., et al. (2020). Coregulation of therapist and client emotion during psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 30(5), 591–603.Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Ge, Y., Qi, H., Qu, W. (2023). The factors impacting the use of navigation systems: A study based on the technology acceptance model. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 93, 106–117.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Weathers, D., Sharma, S., Wood, S. L. (2007). Effects of online communication practices on consumer perceptions of performance uncertainty for search and experience goods. Journal of Retailing, 83(4), 393–401.Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Song, J., Zahedi, F. M. (2005). A theoretical approach to web design in e-commerce: A belief reinforcement model. Management Science, 51(8), 1219–1235.Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Keaveney, S. M., Parthasarathy, M. (2001). Customer switching behavior in online services: An exploratory study of the role of selected attitudinal, behavioral, and demographic factors. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 29(4), 374–390.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] Kamalha, E., Zeng, Y., Mwasiagi, J. I., Kyatuheire, S. (2013). The comfort dimension; a review of perception in clothing. Journal of Sensory Studies, 28(6), 423–444.Suche in Google Scholar

[49] Edvardsson, D. (2009). Balancing between being a person and being a patient–a qualitative study of wearing patient clothing. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(1), 4–11.Suche in Google Scholar

[50] Landis, J. R., Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174.Suche in Google Scholar

[51] Iantovics, L. B., Rotar, C., Morar, F. (2018). Survey on establishing the optimal number of factors in exploratory factor analysis applied to data mining. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 9(2), e1294.Suche in Google Scholar

[52] Harper, C. A., Hogue, T. E. (2014). The emotional representation of sexual crime in the national british press. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 34(1), 3–24.Suche in Google Scholar

[53] Hair, J., Hollingsworth, C. L., Randolph, A. B., Chong, A. Y. L. (2017). An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(3), 442–458.Suche in Google Scholar

[54] Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural equation modeling with mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge, New York.Suche in Google Scholar

[55] Shah, R., Goldstein, S. M. (2006). Use of structural equation modeling in operations management research: Looking back and forward. Journal of Operations Management, 24(2), 148–169.Suche in Google Scholar

[56] Gerbing, D. W., Anderson, J. C. (1988). An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. Journal of Marketing Research, 25(2), 186–192.Suche in Google Scholar

[57] Kaplan, D. (2002). Structural equation modeling. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (Pergamon).Suche in Google Scholar

[58] Lai, K., Green, S. B. (2016). The problem with having two watches: Assessment of fit when RMSEA and CFI disagree. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 51(2–3), 220–239.Suche in Google Scholar

[59] Ainur, A. K., Sayang, M. D., Jannoo, Z., Yap, B. W. (2017). Sample size and non-normality effects on goodness of fit measures in structural equation models. Pertanika Journal of Science & Technology, 25 (2), 575–586.Suche in Google Scholar

[60] Taasoobshirazi, G., Wang, S. (2016). The performance of the SRMR, RMSEA, CFI, and TLI: An examination of sample size, path size, and degrees of freedom. Journal of Applied Quantitative Methods, 11(3), 31–39.Suche in Google Scholar

[61] Oliveri, M.E., Davier, M.V. (2011). Investigation of model fit and score scale comparability in international assessments. Psychological Test and Assessment Modeling, 53(3), 315–333.Suche in Google Scholar

[62] Steenkamp, J. B. E., Maydeu-Olivares, A. (2022). Unrestricted factor analysis: A powerful alternative to confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 51, 86–113.Suche in Google Scholar

[63] Rigdon, E. E., Hoyle, R. H. (1997). Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Journal of Marketing Research, 34(3), 412.Suche in Google Scholar

[64] Agarwal, S. (2022). Integration of emotional design in clothing: An exploratory study in fashion design education. The International Journal of Design Education, 17(1), 79–92.Suche in Google Scholar

[65] Şahin, İ., Güzel, F. Ö. (2020). Do experiential destination attributes create emotional arousal and memory?: A comparative research approach. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 29(8), 956–986.Suche in Google Scholar

[66] Suwankhong, D., Liamputtong, P. (2016). Breast cancer treatment: Experiences of changes and social stigma among Thai women in southern Thailand. Cancer Nursing, 39(3), 213–220.Suche in Google Scholar

[67] Gordon, L., Guttmann, S. (2013). A user-centered approach to the redesign of the patient hospital gown. Fashion Practice, 5(1), 137–151.Suche in Google Scholar

[68] Syed, S., Stilwell, P., Chevrier, J., Adair, C., Markle, G., Rockwood, K. (2022). Comprehensive design considerations for a new hospital gown: A patient-oriented qualitative study. Canadian Medical Association Open Access Journal, 10(4), E1079–E1087.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 by the authors, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Characterization of viscoelastic properties of yarn materials: Dynamic mechanical analysis in the transversal direction

- Analysis of omni-channel implementations that are preferred by consumers in clothing sector

- Structural modeling and analysis of three-dimensional cross-linked braided preforms

- An experimental study of mechanical properties and comfortability of knitted imitation woven shirt fabrics

- Technology integration to promote circular economy transformation of the garment industry: a systematic literature review

- Research on T-shirt-style design based on Kansei image using back-propagation neural networks

- Research on She nationality clothing recognition based on color feature fusion with PSO-SVM

- Accuracy prediction of wearable flexible smart gloves

- Preparation and performance of stainless steel fiber/Lyocell fiber-blended weft-knitted fabric

- Development of an emotional response model for hospital gown design using structural equation modeling

- Preparation and properties of stainless steel filament/pure cotton woven fabric

- Facemask comfort enhancement with graphene oxide from recovered carbon waste tyres

- Use of enzymatic processes in the tanning of leather materials

- Optical-related properties and characterization of some textile fibers using near-infrared spectroscopy

- Network modeling of aesthetic effect for Chinese Yue Opera costume simulation images

- Predicting consumers’ garment fit satisfactions by using machine learning

- Non-destructive identification of wool and cashmere fibers based on improved LDA using NIR spectroscopy

- Study on the relationship between structure and moisturizing performance of seamless knitted fabrics of protein fibers for autumn and winter

- Antibacterial and yellowing performances of sports underwear fabric with polyamide/silver ion polyurethane filaments

- Numerical and experimental analysis of ballistic performance in hybrid soft armours composed of para-aramid triaxial and biaxial woven fabrics

- Phonetic smart clothing design based on gender awareness education for preschoolers

- Determination of anthropometric measurements and their application in the development of clothing sizing systems for women in the regions of the Republic of Croatia

- Research on optimal design of pleated cheongsam based on Kano–HOQ–Pugh model

- Numerical investigation of weaving machine heald shaft new design using composite material to improve its performance

- Corrigendum to “Use of enzymatic processes in the tanning of leather materials”

- Shaping of thermal protective properties of basalt fabric-based composites by direct surface modification using magnetron sputtering technique

- Numerical modeling of the heat flow component of the composite developed on the basis of basalt fabric

- Weft insertion guideway design based on high-temperature superconducting levitation

- Ultrasonic-assisted alkali hydrolysis of polyethylene terephthalate fabric and its effect on the microstructure and dyeing properties of fibers

- Comparative study on physical properties of bio-based PA56 fibers and wearability of their fabrics

- Investigation of the bias tape roll change time efficiency in garment factories

- Analysis of foot 3D scans of boys from Polish population

- Optimization of garment sewing operation standard minute value prediction using an IPSO-BP neural network

- Influence of repeated switching of current through contacts made of electroconductive fabrics on their resistance

- Numerical calculation of air permeability of warp-knitted jacquard spacer shoe-upper materials based on CFD

- Compact Spinning with Different Fibre Types: An Experimental Investigation on Yarn Properties in the Condensing Zone with 3D-Printed Guiding Device

- Modeling of virtual clothing and its contact with the human body

- Advances in personalized modelling and virtual display of ethnic clothing for intelligent customization

- Investigation of weave influence on flame retardancy of jute fabrics

- Balloonless spinning spindle head shape optimisation

- Research on 3D simulation design and dynamic virtual display of clothing flexible body

- Turkish textile and clothing SMEs: Importance of organizational learning, digitalization, and internationalization

- Corrigendum To: “Washing characterization of compression socks”

- Study on the promotion multiple of blood flow velocity on human epidermal microcirculation of volcanic rock polymer fiber seamless knitted fabric

- Bending properties and numerical analysis of nonorthogonal woven composites

- Bringing the queen mother of the west to life: Digital reconstruction and analysis of Taoist Celestial Beings Worshiping mural’s apparel

- Modeling process for full forming sports underwear

- Retraction of: Ionic crosslinking of cotton

- An observational study of female body shape characteristics in multiracial Malaysia

- Study on theoretical model and actual deformation of weft-knitted transfer loop based on particle constraint

- Design and 3D simulation of weft-knitted jacquard plush fabrics

- An overview of technological challenges in implementing the digital product passport in the textile and clothing industry

- Understanding and addressing the water footprint in the textile sector: A review

- Determinants of location changes in the clothing industry in Poland

- Influence of cam profile errors in a modulator on the dynamic response of the heald frame

- Quantitative analysis of wool and cashmere fiber mixtures using NIR spectroscopy

- 3D simulation of double-needle bar warp-knitted clustered pile fabrics on DFS

- Finite element analysis of heat transfer behavior in glass fiber/metal composite materials under constant heat load

- Price estimation and visual evaluation of actual white fabrics used for dress shirts and their photographic images

- Effect of gluing garment materials with adhesive inserts on their multidirectional drape and bending rigidity

- Optimization analysis of carrier-track collision in braiding process

- Numerical and experimental analysis of the ballistic performance of soft bulletproof vests for women

- The antimicrobial potential of plant-based natural dyes for textile dyeing: A systematic review using prisma

- Influence of sewing parameters on the skin–fabric friction

- Validation by experimental study the relationship between fabric tensile strength and weave structures

- Optimization of fabric’s tensile strength and bagging deformation using surface response and finite element in stenter machine

- Analysis of lean manufacturing waste in the process flow of ready-to-wear garment production in Nigeria

- An optimization study on the sol–gel process to obtain multifunctional denim fabrics

- Drape test of fully formed knitted flared skirts based on 3D-printed human body posture

- Supplier selection models using fuzzy hybrid methods in the clothing textile industry

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Characterization of viscoelastic properties of yarn materials: Dynamic mechanical analysis in the transversal direction

- Analysis of omni-channel implementations that are preferred by consumers in clothing sector

- Structural modeling and analysis of three-dimensional cross-linked braided preforms

- An experimental study of mechanical properties and comfortability of knitted imitation woven shirt fabrics

- Technology integration to promote circular economy transformation of the garment industry: a systematic literature review

- Research on T-shirt-style design based on Kansei image using back-propagation neural networks

- Research on She nationality clothing recognition based on color feature fusion with PSO-SVM

- Accuracy prediction of wearable flexible smart gloves

- Preparation and performance of stainless steel fiber/Lyocell fiber-blended weft-knitted fabric

- Development of an emotional response model for hospital gown design using structural equation modeling

- Preparation and properties of stainless steel filament/pure cotton woven fabric

- Facemask comfort enhancement with graphene oxide from recovered carbon waste tyres

- Use of enzymatic processes in the tanning of leather materials

- Optical-related properties and characterization of some textile fibers using near-infrared spectroscopy

- Network modeling of aesthetic effect for Chinese Yue Opera costume simulation images

- Predicting consumers’ garment fit satisfactions by using machine learning

- Non-destructive identification of wool and cashmere fibers based on improved LDA using NIR spectroscopy

- Study on the relationship between structure and moisturizing performance of seamless knitted fabrics of protein fibers for autumn and winter

- Antibacterial and yellowing performances of sports underwear fabric with polyamide/silver ion polyurethane filaments

- Numerical and experimental analysis of ballistic performance in hybrid soft armours composed of para-aramid triaxial and biaxial woven fabrics

- Phonetic smart clothing design based on gender awareness education for preschoolers

- Determination of anthropometric measurements and their application in the development of clothing sizing systems for women in the regions of the Republic of Croatia

- Research on optimal design of pleated cheongsam based on Kano–HOQ–Pugh model

- Numerical investigation of weaving machine heald shaft new design using composite material to improve its performance

- Corrigendum to “Use of enzymatic processes in the tanning of leather materials”

- Shaping of thermal protective properties of basalt fabric-based composites by direct surface modification using magnetron sputtering technique

- Numerical modeling of the heat flow component of the composite developed on the basis of basalt fabric